Abstract

Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) starts immediate-early transcription at nuclear domains 10 (ND10), forming a highly dynamic immediate transcript environment at this nuclear site. The reason for this spatial correlation remains enigmatic, and the mechanism for induction of transcription at ND10 is unknown. We investigated whether tegument-based transactivators are involved in the specific intranuclear location of HCMV. Here, we demonstrate that the HCMV transactivator tegument protein pp71 accumulates at ND10 before the production of immediate-early proteins. Intracellular trafficking of pp71 is facilitated through binding to a coiled-coil region of Daxx. The C-terminal domain of Daxx then interacts with SUMO-modified PML, resulting in the deposition of pp71 at ND10. In Daxx-deficient cells, pp71 does not accumulate at ND10, proving in vivo the necessity of Daxx for pp71 deposition. Also, HCMV forms immediate transcript environments at sites other than ND10 in Daxx-deficient cells, and so does the HCMV pp71 knockout mutant UL82−/− in normal cells. This result strongly suggests that pp71 and Daxx are essential for HCMV transcription at ND10. Lack of Daxx had the effect of reducing the infection rate. We conclude that the tegument transactivator pp71 facilitates viral genome deposition and transcription at ND10, possibly priming HCMV for more efficient productive infection.

Nuclear domains 10 (ND10), also called PML nuclear bodies or PML oncogenic domains (PODs), represent intranuclear accumulations of several proteins, including the transcription repressors PML, Sp100, HP1, and Daxx. Within the highly specialized intranuclear architecture, ND10 presumably act as nuclear depots to maintain the homeostatic balance through controlled recruitment and release of proteins (reviewed in references 24 and 27). PML is the key component for ND10 maintenance and is responsible for the recruitment of other proteins to ND10. Daxx is recruited to ND10 from condensed chromatin through interaction with PML modified by a small ubiquitin-like modifier (SUMO-1) (15). Human Daxx was originally discovered as a DNA-binding protein (17) and has been reported to be involved in several cellular processes, including apoptosis, transcription regulation, and embryo development (reviewed in reference 26). The growing list of Daxx-interacting partners suggests that Daxx acts as a protein modulator in numerous cellular activities, while its accumulation at ND10 appears to regulate the availability of soluble Daxx for these processes.

At least three ND10 proteins, PML, Sp100, and Daxx, are upregulated by interferon (7, 9, 10, 33), suggesting the potential involvement of ND10 in the antiviral cellular response. Indeed, studies have demonstrated that several DNA viruses start their synthetic processes in the immediate vicinity of ND10 (reviewed in reference 23). Input viral DNA accumulates at ND10, followed by transcription and replication juxtaposed to ND10. The structure of ND10 becomes modified in a virus-specific manner through the action of immediate-early (IE) proteins. Thus, human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) forms a highly dynamic immediate transcript environment (ITE) during the IE stage of infection as it begins transcription juxtaposed to ND10 (16). The HCMV IE1 protein accumulates at ND10 and eventually disperses the structure (1, 18, 34), possibly through direct interaction with PML (1), while the IE2 protein accumulates juxtaposed to a subpopulation of ND10 where HCMV starts transcription, thus providing an ITE marker (16). This high spatial-temporal correlation suggests that ND10 functionally influence viral infection, although the reasons for this relationship and the consequences for virus and cell remain unclear. To further understand the early association between ND10 and viruses, we examined the processes that occur before the initiation of viral transcription, focusing on the association of HCMV tegument transactivators with ND10.

During infection, the viral envelope fuses with the cell membrane, delivering tegument proteins located between the membrane envelope and capsid into the cell. While the assembly and overall function of viral tegument are not well understood, several studies have characterized transactivation functions of proteins within this structure. The HCMV tegument protein pp71, the product of the UL82 gene, activates a major IE promoter and other early promoters of this virus (5, 6, 22). Moreover, pp71 can activate a number of heterologous promoters, both in the context of transient transfection and upon infection by a herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) mutant expressing pp71 (13). The latter finding led to the suggestion that pp71 may be the functional counterpart of HSV-1 tegument protein VP16, which transactivates the IE genes of this virus through interaction with a number of cellular proteins, including Oct-1 (reviewed in reference 30). Transient transfection experiments also demonstrated that pp71 accumulates in the nucleoplasm (11) and dramatically enhances the infectivity of HCMV DNA, indicating that this tegument protein activates IE viral transcription before production of HCMV IE transactivators in the context of infection (2). Growth of an HCMV mutant that does not express pp71 is severely restricted at a low multiplicity of infection (MOI), further pointing to the transactivation function of this tegument protein during the IE stage of infection (5).

In the present study, we show that pp71 accumulates at ND10 upon HCMV infection and before production of IE proteins. Interaction with Daxx and subsequent binding of Daxx to SUMO-modified PML brings pp71 to ND10. In Daxx−/− cells, pp71 cannot accumulate at ND10 and ITE is not associated with ND10. Moreover, an HCMV pp71 knockout mutant UL82 cannot form ITE at ND10. Our findings suggest that intracellular accumulation of the transactivator pp71 can prime cells for more efficient infection and may in part explain initiation of HCMV IE transcription at ND10.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells, growth conditions, inhibitors, and virus infection.

WI38 human fibroblasts, COS-7 cells, MPEF mouse T antigen-immortalized fibroblasts, and PML−/− mouse T antigen-immortalized fibroblasts have been described (15). Daxx−/− mouse T antigen-immortalized fibroblasts were produced as described below. All cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum and 1% antibiotics and grown at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere. For immunohistochemical staining, cells were grown on round cover slips in 24-well plates (Corning Glass, Inc.) until approximately 80% confluent before fixation. Two days after plating, cells were infected with HCMV (Towne strain) or HCMV UL82−/− (5) at a multiplicity of 1 per 10 cells, resulting in 10% infected cells, as determined by staining with IE2 antibodies at 3 h after infection. For UV inactivation, HCMV stock was irradiated as described before (32).

Immunolocalization and antibodies.

At different time points after plating, cells were fixed at room temperature for 15 min with freshly prepared 1% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline and immunostained with different antibodies as described before (14). Cells were analyzed with a Leica TCS SP2 spectral confocal microscope with three fluorescence detectors. LCS Leica confocal software was used in balancing signal strength, and eightfold scanning was used to separate signal from noise. Because of the variability among cells in any given culture, the most prevalent cells are presented.

Rabbit antisera against PML were obtained from J. Frey (18) and used at a 1:200 dilution. Monoclonal antibody 5.14 produced against human Daxx reacts with an epitope between amino acids 495 and 515 (Sotnikov et al., unpublished data) (1:2 dilution); polyclonal rabbit antibodies against mouse and human Daxx were from Santa Cruz (1:50 dilution); and polyclonal rabbit antibodies against SUMO-1 were from P. Freemont (3) (1:50 dilution). Human autoimmune serum 1745 recognizes Sp100 and PML (25) and was used in triple-labeling experiments to mark ND10. Isotype-matched monoclonal antibodies of unrelated specificity were used as controls. Monoclonal antibody CMV355 (28) recognizes pp71. Monoclonal antibody specific for hemagglutinin (HA) (Roche) and Flag M2 (Sigma) were used at 1:300 and 1:200 dilutions, respectively. Polyclonal rabbit antiserum against HCMV IE2 and anti-IE2 monoclonal antibody were kindly provided by B. Plachter.

Construction of Daxx−/− cell line.

The mouse Daxx gene was cloned from a 129SV lambda phage genomic library. One clone was obtained that contained 15 kb of mouse DNA, including the Daxx gene. The 5′-flanking segment used for the targeting construct was a 1.0-kb PCR product containing exon 2, intron 2, and part of exon 3. The product was amplified with primers MSA1 (5′-GGCGAAGCTTAGGAAGTGCTACAAGTTG-3′), located in exon 2, and MSA2 (5′-GCCGTTCGAAACGAGGAGTCTGGGTCATC-3′), located in exon 3, and cloned into the HindIII site of pSP72 (Promega). The 3′-flanking segment, a 6.7-kb fragment from the EcoRI site in intron 7 to the end of the genomic clone (NotI site), was cloned in the same vector.

The targeting construct (10 μg) was linearized by NotI and transfected by electroporation into 129SV embryonic stem (ES) cells. This strategy replaces part of exon 3 and all of exons 4, 5, 6, and 7 with an intact neo gene. After selection with G418, surviving colonies were analyzed by PCR to identify those that had undergone homologous recombination at the Daxx locus. The following primers were used for PCR: MSA3 (located in the middle of exon 2), 5′-CTGGTCCTGGCCTGTCTCAACAG-3′, and NeoI (located in the 5′ promoter region of the neo gene cassette), 5′-TGCGAGGCCAGAGGCCACTTGTGTAGC-3′.

ES cells from a correctly targeted clone were cocultivated with FVB × FVB blastocysts and transferred into pseudopregnant FVB foster mothers. Two resulting high-grade chimeras (70 and 90% of agouti color) were mated to FVB/N females. Germ line transmission of the targeted Daxx allele was predicted by black eye color and agouti coat color in F1 and confirmed by PCR analysis with the primers GenDaxx227UP (5′-GCGGCTGCAGGAGAAGGAG-3′), corresponding to bp 627 to 645 of mDaxx cDNA, mDaxxGen4Down (5′-TTGTTAATGAGCCGTTCAATG-3′), corresponding to bp 848 to 827 of mDaxx cDNA for the mDaxx wild-type allele, and GenDaxx227Up/NeoI for the knockout allele.

Genotyping of F2 mice and embryonic day 8 (E8) to E15 embryos was performed with DNA purified from a toe or yolk sacs. PCR analysis was performed with primers GenDaxx227Up and mDaxxGen4Down or GenDaxx227Up and NeoI. Among 99 mice tested, 38 were +/+ and 61 were +/−, suggesting that Daxx−/− is lethal. Results of embryo analysis indicated lethality at E9. Fibroblasts were collected from Daxx−/− embryos and immortalized by simian virus 40 T antigen. Absence of Daxx in this cell line was confirmed by PCR analysis, immunostaining, and Western blot with Daxx antibody.

Expression plasmids and transfection.

pET (expressing green fluorescent protein [GFP]-nuclear localization signal [NLS]) and the pETDaxx wild-type and deletion series have been described (15); pcDNApp71FLAG expresses pp71 fused at the N terminus with the Flag epitope (kindly provided by B. Plachter); pHP1FLAG, which encodes HP1α fused with the Flag epitope (31), was obtained from F. Rauscher (The Wistar Institute). Transfection was carried out with SuperFect transfection reagent (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's recommendations.

Coimmunoprecipitation assays.

For immunoprecipitation analysis, COS-7 nuclear extracts were prepared from 106 cells (per 100-mm plate) cotransfected 20 h before with pET or one of the pETDaxx plasmids and either pcDNApp71FLAG or pHP1FLAG. Cells were washed twice, collected in phosphate-buffered saline, and incubated for 20 min in NLB-400 mM NaCl supplemented with protease inhibitors (1 mM EDTA plus 100 μg of phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride [PMSF], 10 μg of aprotinin, and 10 μg of leupeptin per ml). Nuclear extracts were obtained, brought to 150 mM NaCl with NLB-50 mM NaCl, and incubated for 1 h at 4°C with anti-Flag-M2 antibody-conjugated beads (ProBond resin; Invitrogen). Beads were washed three times with NLB-150 mM NaCl buffer and boiled in 2× protein sample buffer. The eluted proteins were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) in 4 to 12% polyacrylamide gradient gels, transferred to a nylon membrane, and detected with rabbit anti-GFP antibodies (Clontech) diluted 1:300. Anti-Flag M2 monoclonal antibody (Sigma) was used to detect Flag-tagged pp71 and HP1α in input and immunoprecipitated samples.

RESULTS

HCMV tegument protein pp71 accumulates at ND10 upon infection.

Several DNA viruses, including adenovirus type 5, HSV-1, simian virus 40, and HCMV, begin their transcription and replication in the vicinity of ND10 (reviewed in reference 23). HCMV induces a highly dynamic ITE in the infected nuclei that includes the initial positioning of the viral genome at ND10, where it begins to transcribe. Later, two IE HCMV proteins, IE1 and IE2, accumulate at ND10, and IE1 finally disperses ND10 (16). We analyzed the infectious process before initiation of viral transcription, asking specifically whether the viral tegument proteins locate to ND10.

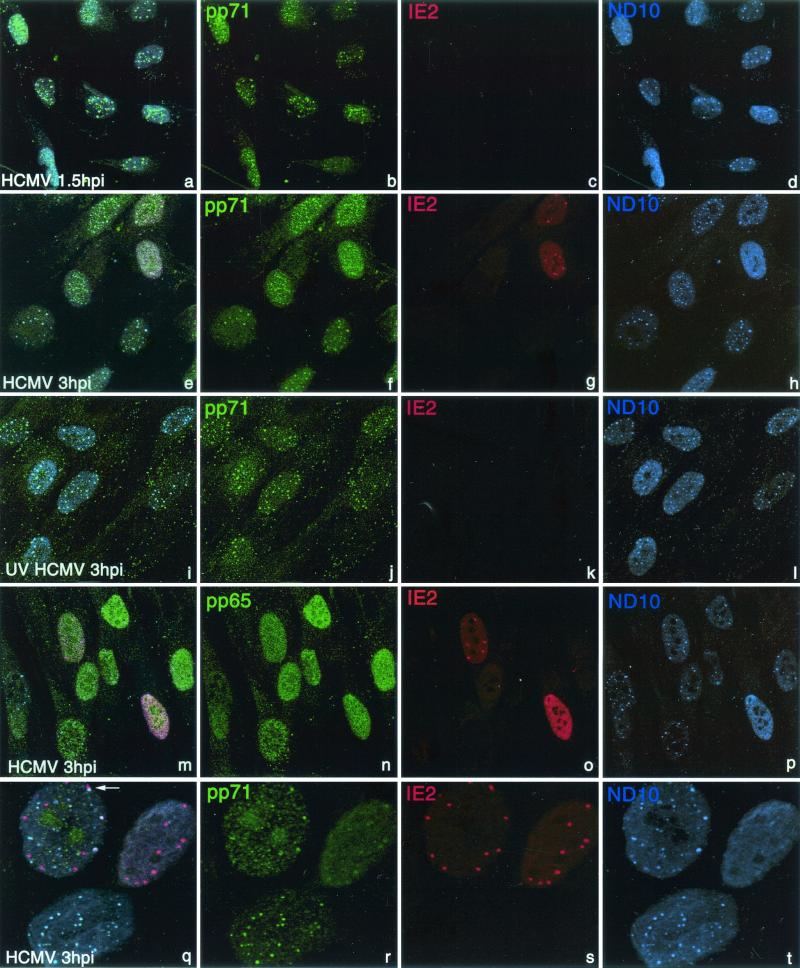

Immunolocalization of HCMV tegument protein pp71 revealed accumulation of this polypeptide in the nucleoplasm already at 1.5 h postinfection, before production of IE2 proteins (Fig. 1a to d). In addition to the cytoplasmic and dispersed nucleoplasmic localization, pp71 also accumulated in ND10-like domains (Fig. 1b). Staining for ND10 revealed colocalization, indicating that pp71 is positioned at ND10 very early during infection (Fig. 1a, b, and d). At 3 h postinfection, pp71 remained localized at ND10, and IE2 protein also began to accumulate there (Fig. 1e to h). pp71 was located at ND10 in a majority of cells of the monolayer (Fig. 1f), while IE2 was visible in substantially fewer cells (Fig. 1g) at this low MOI, potentially reflecting the large number of viral particles that still can load cells with pp71. Both the early timing of pp71 visualization (pp71 is expressed at the early and late but not at the immediate-early phase of infection [11]) and the high percentage of pp71-positive cells indicate the tegument origin of the protein.

FIG. 1.

Localization of pp71 during HCMV infection. Human primary WI38 fibroblasts were infected at 0.1 MOI with HCMV (a to h and m to t) or with UV-inactivated HCMV (i to l) for 1.5 h (a to d) or 3 h (e to t) and triple stained for pp71 with monoclonal antibody CMV355 (b, f, j, and r), for IE2 with polyclonal rabbit antibody (c, g, k, o, and s), and for ND10 with human antibody 1745 reacting with the ND10-associated proteins Sp100 and PML (d, h, l, p, and t). Merged images demonstrate colocalization of pp71 and ND10 at 1.5 h postinfection, before IE proteins are visible (a), at 3 h postinfection, when only some cells start producing IE proteins (e), and upon infection by UV-inactivated virus (i). Another HCMV tegument protein, pp65, does not accumulate at ND10 (m to p). Details of pp71 accumulation are presented at the enlarged sections (q to t). IE2 accumulated juxtaposed to pp71/ND10 accumulations (q, arrow).

In cells infected with UV-inactivated HCMV, pp71 still accumulated at ND10, but IE2 was not detected (Fig. 1i to l), confirming that the pp71 accumulated in infected cells is the tegument protein. Another HCMV tegument protein, pp65, was homogeneously distributed in the nucleoplasm at 3 h postinfection, but did not accumulate at ND10, demonstrating the specificity of pp71 accumulation at ND10 (Fig. 1m to p). The dynamics of pp71 and IE2 accumulation relative to ND10 is presented at higher magnification in Fig. 1q to t; pp71 colocalizes with ND10 in the lower cell; in the upper left cell, IE2 is accumulated juxtaposed to pp71/ND10 accumulations (arrow), and several ND10 are destroyed; in the upper right cell, all ND10 are destroyed and pp71 is almost homogeneously distributed in the nucleoplasm, with some low accumulations with IE2.

Daxx mediates intracellular trafficking of pp71.

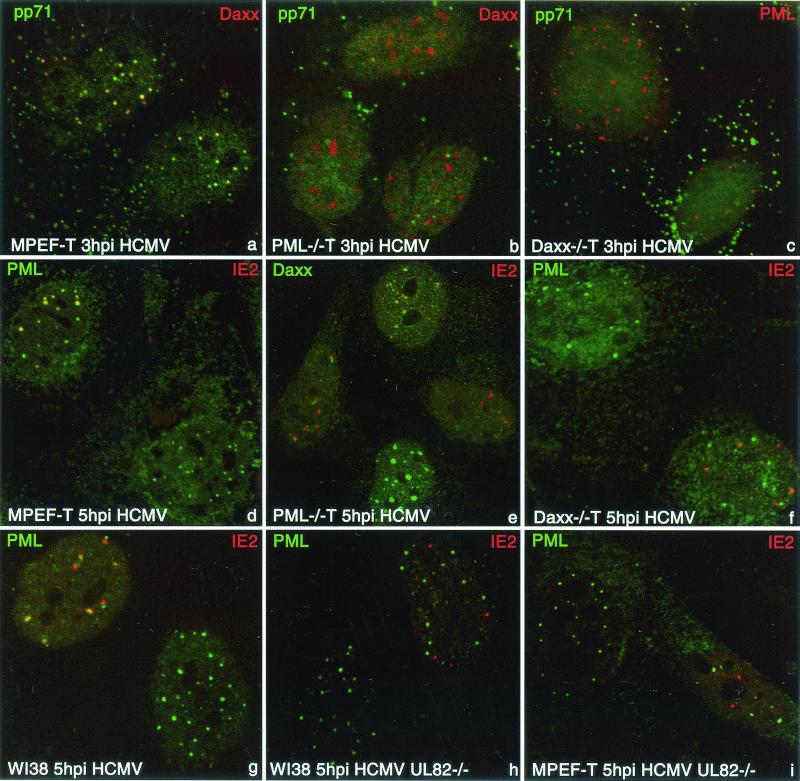

We examined the potential role of two ND10-associated proteins, PML and Daxx, in mediating pp71 accumulation at ND10 with the respective knockout mouse cells. Although mouse cells are not permissive for productive HCMV infection, they support IE events of infection. Unlike in human cells, HCMV cannot destroy ND10 in mouse cells (Ishov et al., unpublished data); they therefore remain as markers. When control MPEF were infected with HCMV, pp71 accumulated at ND10 (Fig. 2a, yellow domains in nucleoplasm resulting from colocalization of Daxx red and pp71 green signals), as in human cells. pp71 also remained visible in the cytoplasm and/or at the cell membrane as a component of the virion.

FIG. 2.

pp71 accumulation at ND10 is Daxx dependent and required for the formation of ITE juxtaposed to ND10. MPEF-T (a, d, and i), PML−/− T (b and e), or Daxx−/− T (c and f) mouse cells or WI38 human fibroblasts (g and h) were infected with HCMV (0.1 MOI) for 3 h (a to c) or 5 h (d to g) or with HCMV UL82−/− (0.1 MOI) for 5 h (h and i), fixed, and immunostained with the indicated antibody. While pp71 in MPEF-T infected cells accumulated at ND10 (a), pp71 does not colocalize with this structure in Daxx−/− cells (c) or with Daxx at condensed chromatin in PML−/− T cells (b). Upon infection of MPEF-T cells, the IE2 protein marker of ITE localizes juxtaposed to ND10 (d), but no such correlation between ND10 and IE2 is observed in Daxx−/− T cells (f). In PML−/− T cells (e), Daxx is transiently relocated upon infection from condensed chromatin (lower cell) to accumulations juxtaposed to IE2 (left and upper cell), and finally is distributed homogeneously in the nucleoplasm (right cell). IE2 accumulates juxtaposed to ND10 upon HCMV infection of WI38 (g) but not upon HCMV UL82−/− infection of WI38 (h) or MPEF-T (i) cells.

PML is important for ND10 assembly (15), suggesting the necessity of this ND10 protein for pp71 intranuclear accumulation. To test this possibility, we used PML−/− cells, in which ND10 are not formed and all ND10-associated proteins are located in alternative nucleoplasmic compartments. Daxx, for example, is accumulated at condensed chromatin in this cell line (15) (Fig. 2b, red for Daxx). When PML−/− cells were infected with HCMV, pp71 was detected homogeneously distributed in the nucleoplasm (Fig. 2b). These findings indicate that in the absence of the PML-based structure, pp71 did not accumulate at specific sites.

To test the potential effect of Daxx on pp71 accumulation at ND10, we derived a Daxx−/− cell line (see Materials and Methods) from a Daxx knockout mouse (unpublished data), infected the cells with HCMV, and probed for pp71 and PML. The absence of Daxx did not influence the ND10 structure itself, as observed by PML localization (Fig. 2c, PML in red); however, pp71 was not detected at ND10 but still accumulated in the nucleoplasm (Fig. 2c, pp71 in green). The punctate pattern of pp71 outside nuclei (Fig. 2a to c) likely represents pp71 inside adsorbed viral particles. The absence of pp71 accumulation at ND10 in Daxx−/− cells points to the role of Daxx in pp71 intracellular trafficking and accumulation at ND10.

pp71 interacts with Daxx.

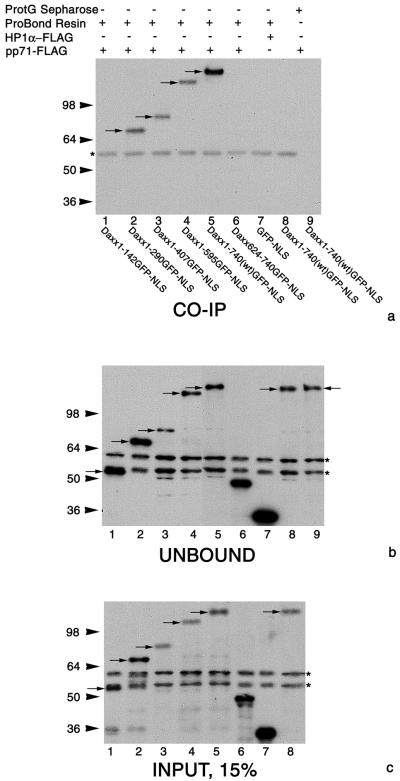

pp71 has recently been shown to interact with Daxx in a yeast two-hybrid system (H. Hofmann, H. Sindre, and T. Stamminger, Abstr. 25th Int. Herpesvirus Workshop, abstr. 10.03, 2000). To verify those data in mammalian cells, we performed immunoprecipitation experiments with COS-7 cells cotransfected with plasmid pcDNApp71FLAG, expressing pp71-Flag, and plasmids expressing Daxx or several truncated forms of this protein fused with GFP-NLS (see reference 15 for plasmid details). Full-length Daxx interacted with pp71 (Fig. 3a, lane 5), as did all but the shortest N-terminal Daxx mutant (amino acids 1 to 142; Fig. 3a, lane 1), although to a lesser extent than the wild-type protein. These data map the interaction between Daxx and pp71 to amino acids 142 to 290.

FIG. 3.

Daxx interacts with pp71 in immunoprecipitation experiments. COS-7 cells were cotransfected with pcDNApp71FLAG or pHP1FLAG and pETDaxx plasmids encoding Daxx deletion mutants or wild-type Daxx fused with GFP-NLS or pET encoding GFP-NLS. Cell extracts were incubated with ProBond resin or protein G (ProtG)-Sepharose as indicated and probed for Daxx and deletion mutants of this protein with anti-GFP polyclonal antibody (a). An unbound fraction is presented at panel b, and 15% of input used for immunoprecipitation is presented in panel c. The same cell extracts were used in lanes 5 and 9 (a and b). Arrows indicate wild-type Daxx or mutants fused to GFP-NLS or GFP-NLS; asterisks mark nonspecific bands. Wild-type Daxx and mutants in which amino acids 1 to 290, 1 to 407, and 1 to 595 were deleted are precipitated under these conditions (lanes 5 and 2 to 4 of panel a), but mutants in which amino acids 1 to 142 and 624 to 740 were deleted are not. Note that wild-type Daxx is not precipitated in the absence of ProBond resin or pp71-Flag (lanes 8 and 9, panel a). GFP-NLS is also not precipitated (lane 7, panel a), confirming the specificity of the Daxx-pp71 interaction. Sizes are shown at the left in kilodaltons.

The carboxyl-terminal region (amino acids 624 to 740), previously shown to interact with several proteins, including SUMO-modified PML (reviewed in reference 26), did not interact with pp71 (Fig. 3a, lane 6). These findings suggest that Daxx has an additional protein interaction domain located in its middle region, potentially a predicted coiled-coil domain that is located between amino acids 181 and 218. Negative controls demonstrated the specificity of the pp71-Daxx interaction (Fig. 3a, lanes 8 and 9) and the inability of GFP-NLS alone to interact with pp71 (Fig. 3a, lane 7).

Formation of HCMV immediate transcript environment at ND10 is promoted by pp71.

Next we decided to test whether ND10 accumulation of pp71 is essential for the initiation of HCMV transcription and the formation of the HCMV immediate transcript environment at ND10. We demonstrated previously that IE2 accumulates exclusively beside the subpopulation of ND10 where HCMV transcribes (16) and thus can be used as a spatial marker for the ITE. Upon HCMV infection of mouse fibroblast cell lines, ND10 are not modified, and most IE2 domains are located juxtaposed or partially overlapping ND10 (Fig. 2d), indicating that HCMV forms an ITE at ND10 as in human cells. However, analysis of HCMV-infected Daxx−/− cells (Fig. 2f) revealed almost no spatial correlation between ND10 and IE2, indicating that HCMV does not transcribe at ND10 in Daxx−/− cells.

In HCMV-infected PML−/− cells, IE2 domains were often located juxtaposed to cloud-like accumulations of Daxx (Fig. 2e, upper and left cells) that did not correspond to condensed chromatin accumulations of Daxx specific for the PML−/− cells. Such Daxx accumulations near active transcription sites may indicate an unknown function of Daxx during virus infection. To further test whether HCMV transcription at ND10 is the consequence of pp71 accumulation at this domain, we used pp71-deficient HCMV mutant UL82−/− (5). While almost all IE2 domains are located adjacent to ND10 in HCMV-infected human fibroblasts (Fig. 2g), there was no correlation between IE2 and ND10 in HCMV UL82−/−-infected human (Fig. 2h) or mouse (Fig. 2i) fibroblasts. These data further point to the requirement for pp71 in the formation of the viral ITE at ND10.

Assessment of the consequences resulting from positioning the HCMV ITE at sites different from ND10 was hampered by the nonpermissivness of mouse fibroblasts for productive HCMV infection. We therefore could not compare virus yield after infection in Daxx−/− and MPEF cells. However, we could quantify the number of IE2-positive cells upon HCMV infection in both cell types. Counting 500 cells 5 h after infection at 0.1 or 0.05 MOI, the number of IE2-positive cells in the Daxx−/− cell line is reduced twofold compared with MPEF for both MOIs tested. Combined with the necessity for Daxx for ITE formation at ND10, this suggests that the positional correlation between ND10 and sites of HCMV transcription has functional relevance.

DISCUSSION

Several groups have recently reported a spatial-temporal correlation between the nucleoplasmic structure ND10 and sites of viral synthesis during infection (reviewed in reference 23). However, the reasons for this phenomenon are unclear, and the question remains whether this correlation is advantageous for the virus or the host. Whereas the correlation of viral transcript and replication domains with ND10 suggests a helper function of this structure, at least three ND10-associated proteins, PML, Sp100, and Daxx (7, 9, 10, 33), are upregulated by interferon, and PML, Daxx, HP1, and Sp100 are considered transcriptional repressors. Thus, ND10 may function as one of the last points of a cell's defense against viruses by repressing viral input at these locations. Moreover, most DNA viruses induce ND10 disassembly during infection.

Before transcription can begin, the IE promoters must be transactivated by viral tegument proteins which are released into the cell. In the present study, we found that the HCMV tegument transactivator protein pp71 accumulates at ND10, the site of HCMV IE transcription, immediately after infection. This observation led us to investigate in detail the intracellular trafficking properties of this viral tegument polypeptide and the consequences of pp71 accumulation at ND10 for IE events of HCMV infection.

Mechanism of pp71 intracellular trafficking.

Accumulation of pp71 at ND10 suggests a critical role for some of the ND10 proteins, potentially SUMO-modified PML or Daxx, in intracellular deposition of pp71. Our previous study of ND10 dynamics (15) indicated that PML is at the center of ND10 assembly, since ND10 are not formed in PML−/− cells and all ND10 proteins have an alternative nucleoplasmic localization, e.g., Daxx in PML−/− cells is concentrated at condensed chromatin. Concomitantly, pp71 in infected PML−/− cells is dispersed in the nucleoplasm, indicating again that PML is required for the assembly of the site of pp71 accumulation, ND10. The absence of pp71 accumulation at ND10 upon infection in Daxx−/− cells indicates that Daxx is essential for pp71 deposition at this structure, even in the presence of intact ND10. Direct interaction between pp71 and Daxx as determined by coimmunoprecipitation experiments confirmed this idea.

Surprisingly, the region of pp71 interaction was mapped to amino acids 142 to 290 of the Daxx molecule, while all other reported Daxx-binding proteins, including CENP-C, Pax3, and Fas, interact with the carboxyl end of the Daxx molecule (12, 29, 36). Thus, Daxx has at least two regions of protein interaction. We showed previously that Daxx itself is positioned at ND10 through interaction of the carboxyl end of the molecule and SUMO-modified PML (15), as confirmed by others (19, 20, 37). From these observations follows the idea that both Daxx and PML are involved in intracellular trafficking of pp71 to ND10, which is facilitated through binding of pp71 with the coiled-coil-containing region of Daxx and subsequently mediated through interaction between the carboxyl end of Daxx and SUMO-modified PML. Hence, we present the first evidence of viral protein accumulation at ND10 through a cascade of interactions whereby pp71 is accumulated at this structure through interaction with Daxx, which is itself recruited to ND10 through direct interaction with SUMO-modified PML.

pp71 and HCMV infection.

pp71 accumulated at ND10 even at low HCMV input, before initiation of IE events, and even in the absence of viral transcription after UV treatment of HCMV input, confirming the tegument origin of pp71 at this stage of infection. pp71 can activate a number of HCMV promoters, including the major immediate-early promoter (22, 35), and several heterogeneous promoters, including those of HSV-1 and adenovirus (13). Moreover, pp71 is required for HCMV infection following viral DNA transfection and after infection with UL82−/−, the pp71 deletion mutant of HCMV (2, 4, 5). Previously, we reported that only those HCMV input genomes positioned at ND10 started transcription and formed ITE at these nuclear domains. Here we observed that ND10 is also the site of accumulation of pp71, the transactivator of HCMV IE promoters that penetrates cells at the time of infection as the tegument protein. Together, the data suggest that the tegument-derived pp71 can transactivate viruses positioned at ND10 before production of HCMV IE transactivators, as IE1 and IE2.

High concentrations of pp71 at ND10 may explain the initiation of viral transcription at these domains. In Daxx−/− cells, pp71 is not accumulated at ND10, nor are ITEs of HCMV (as determined by IE2 staining) formed there. Moreover, the HCMV UL82 deletion mutant virus, which is deficient in pp71 expression, forms ITEs mostly unassociated with ND10. Based on the collective data, we conclude that pp71 accumulation at ND10 provides transactivation advantages for HCMV input genomes at these nuclear domains. The observed twofold reduction in the number of IE2-positive Daxx−/− cells compared to the wild-type cells might be due, at least in part, to the inability of pp71 to accumulate at high concentrations at ND10 in the absence of Daxx.

Numerous studies have variously described Daxx functions in apoptosis and transcription regulation. Daxx has been identified as a repressor of basal and activated transcription (12, 20, 21), and repression of several genes through direct interaction between Daxx and activators such as Ets-1 and Pax3 has been reported (12, 21). The mechanism of Daxx-mediated repression has been suggested to involve recruitment of histone deacetylases to chromatin through interaction between Daxx and these enzymes (20), although other investigators reported no release from Daxx repression activity in the presence of the histone deacetylase inhibitor trichostatin A (12). The transcription repressor function of Daxx has been implicated in interferon-induced apoptosis of lymphoid progenitors concomitant with increased accumulation of Daxx at ND10 (9). Our model of pp71 intranuclear accumulation raises the possibility that the repression activity of Daxx is facilitated, at least partly, through the targeting of other Daxx-binding proteins from their site of action to ND10.

pp71 induces mild cell growth inhibition, as indicated by a 20% reduction in colony formation (32), and transactivates not only HCMV promoters but also several heterogeneous promoters (13). Thus, pp71 may prime cells towards more efficient infection as a transactivator of some cellular promoters. Presumably, pp71 can block cell cycle progression, as demonstrated for HCMV IE proteins (reviewed in reference 8). pp71 recruitment to ND10 through interaction with Daxx may downregulate the transactivation of cellular genes by this viral protein. Thus, Daxx may repress transactivation of pp71 as this protein does for other transcription regulators, potentially through a similar mechanism. On the other hand, accumulation of pp71 at ND10 may provide transcription advantages for viral input genomes at these nuclear domains. Further studies are needed to reconcile these discrepant possibilities.

Acknowledgments

We thank Thomas Shenk for pCGNpp71 and HCMV UL82−/−, Bodo Plachter for pcDNApp71FLAG, and Frank Rauscher for pHP1FLAG.

This study was supported by NIH grant AI41136, NIH core grant CA10815, and the G. Harold and Leila Y. Mathers Charitable Foundation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahn, J. H., E. J. Brignole III, and G. S. Hayward. 1998. Disruption of PML subnuclear domains by the acidic IE1 protein of human cytomegalovirus is mediated through interaction with PML and may modulate a RING finger-dependent cryptic transactivator function of PML. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18:4899-4913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baldick, C. J., A. Marchini, C. E. Patterson, and T. Shenk. 1997. Human cytomegalovirus tegument protein pp71 (ppUL82) enhances the infectivity of viral DNA and accelerates the infectious cycle. J. Virol. 71:4400-4408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boddy, M. N., K. Howe, L. D. Etkin, E. Solomon, and P. S. Freemont. 1996. PIC 1, a novel ubiquitin-like protein which interacts with the PML component of a multiprotein complex that is disrupted in acute promyelocytic leukaemia. Oncogene 13:971-982. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bresnahan, W. A., G. E. Hultman, and T. Shenk. 2000. Replication of wild-type and mutant human cytomegalovirus in life-extended human diploid fibroblasts. J. Virol. 74:10816-10818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bresnahan, W. A., and T. E. Shenk. 2000. UL82 virion protein activates expression of immediate early viral genes in human cytomegalovirus-infected cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:14506-14511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chau, N. H., C. D. Vanson, and J. A. Kerry. 1999. Transcriptional regulation of the human cytomegalovirus US11 early gene. J. Virol. 73:863-870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chelbi-Alix, M. K., L. Pelicano, F. Quignon, M. H. Koken, L. Venturini, M. Stadler, J. Pavlovic, L. Degos, and H. de The. 1995. Induction of the PML protein by interferons in normal and APL cells. Leukemia 9:2027-2033. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fortunato, E. A., A. K. McElroy, I. Sanchez, and D. H. Spector. 2000. Exploitation of cellular signaling and regulatory pathways by human cytomegalovirus. Trends Microbiol. 8:111-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gongora, R., R. P. Stephan, Z. Zhang, and M. D. Cooper. 2001. An essential role for daxx in the inhibition of B lymphopoiesis by type I interferons. Immunity 14:727-737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grotzinger, T., T. Sternsdorf, K. Jensen, and H. Will. 1996. Interferon-modulated expression of genes encoding the nuclear-dot-associated proteins Sp100 and promyelocytic leukemia protein (PML). Eur. J. Biochem. 238:554-560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hensel, G. M., H. H. Meyer, I. Buchmann, D. Pommerehne, S. Schmolke, B. Plachter, K. Radsak, and H. F. Kern. 1996. Intracellular localization and expression of the human cytomegalovirus matrix phosphoprotein pp71 (ppUL82): evidence for its translocation into the nucleus. J. Gen. Virol. 77:3087-3097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hollenbach, A. D., J. E. Sublett, C. J. McPherson, and G. Grosveld. 1999. The Pax3-FKHR oncoprotein is unresponsive to the Pax3-associated repressor hDaxx. EMBO J. 18:3702-3711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Homer, E. G., A. Rinaldi, M. J. Nicholl, and C. M. Preston. 1999. Activation of herpesvirus gene expression by the human cytomegalovirus protein pp71. J. Virol. 73:8512-8518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ishov, A. M., and G. G. Maul. 1996. The periphery of nuclear domain 10 (ND10) as site of DNA virus deposition. J. Cell Biol. 134:815-826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ishov, A. M., A. G. Sotnikov, D. Negorev, O. V. Vladimirova, N. Neff, T. Kamitani, E. T. Yeh, J. F. Strauss III, and G. G. Maul. 1999. PML is critical for ND10 formation and recruits the PML-interacting protein Daxx to this nuclear structure when modified by SUMO-1. J. Cell Biol. 147:221-234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ishov, A. M., R. M. Stenberg, and G. G. Maul. 1997. Human cytomegalovirus immediate early interaction with host nuclear structures: definition of an immediate transcript environment. J. Cell Biol. 138:5-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kiriakidou, M., D. A. Driscoll, J. M. Lopez-Guisa, and J. F. Strauss III. 1997. Cloning and expression of primate Daxx cDNAs and mapping of the human gene to chromosome 6p21.3 in the MHC region. DNA Cell Biol. 16:1289-1298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Korioth, F., G. G. Maul, B. Plachter, T. Stamminger, and J. Frey. 1996. The nuclear domain 10 (ND10) is disrupted by the human cytomegalovirus gene product IE1. Exp. Cell Res. 229:155-158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lehembre, F., S. Muller, P. P. Pandolfi, and A. Dejean. 2001. Regulation of Pax3 transcriptional activity by SUMO-1-modified PML. Oncogene 20:1-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li, H., C. Leo, J. Zhu, X. Wu, J. O'Neil, E. J. Park, and J. D. Chen. 2000. Sequestration and inhibition of Daxx-mediated transcriptional repression by PML. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:1784-1796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li, R., H. Pei, D. K. Watson, and T. S. Papas. 2000. EAP1/Daxx interacts with ETS1 and represses transcriptional activation of ETS1 target genes. Oncogene 19:745-753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu, B., and M. F. Stinski. 1992. Human cytomegalovirus contains a tegument protein that enhances transcription from promoters with upstream ATF and AP-1 cis-acting elements. J. Virol. 66:4434-4444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maul, G. G. 1998. Nuclear domain 10, the site of DNA virus transcription and replication. Bioessays 20:660-667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maul, G. G., D. Negorev, P. Bell, and A. M. Ishov. 2000. Review: properties and assembly mechanisms of ND10, PML bodies, or PODs. J. Struct. Biol. 129:278-287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maul, G. G., E. Yu, A. M. Ishov, and A. L. Epstein. 1995. Nuclear domain 10 (ND10) associated proteins are also present in nuclear bodies and redistribute to hundreds of nuclear sites after stress. J. Cell Biochem. 59:498-513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Michaelson, J. S. 2000. The Daxx enigma. Apoptosis 5:217-220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Negorev, D., and G. G. Maul. 2001. Cellular proteins localized at and interacting within ND10/PML nuclear bodies/PODs suggest functions of a nuclear depot. Oncogene 20:7234-7242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nowak, B., C. Sullivan, P. Sarnow, R. Thomas, F. Bricout, J. C. Nicolas, B. Fleckenstein, and A. J. Levine. 1984. Characterization of monoclonal antibodies and polyclonal immune sera directed against human cytomegalovirus virion proteins. Virology 132:325-338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pluta, A. F., W. C. Earnshaw, and I. G. Goldberg. 1998. Interphase-specific association of intrinsic centromere protein CENP-C with HDaxx, a death domain-binding protein implicated in Fas-mediated cell death. J. Cell Sci. 111:2029-2041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roizman, B., and S. Sears. 1996. Herpes simplex viruses and their replication, p. 2231-2259. In B. N. Fields et al. (ed.), Fields virology, 3rd ed., vol. 2. Lippincott-Raven Publishers, Philadelphia, Pa.

- 31.Ryan, R. F., D. C. Schultz, K. Ayyanathan, P. B. Singh, J. R. Friedman, W. J. Fredericks, and F. J. Rauscher 3rd. 1999. KAP-1 corepressor protein interacts and colocalizes with heterochromatic and euchromatic HP1 proteins: a potential role for Kruppel-associated box-zinc finger proteins in heterochromatin-mediated gene silencing. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19:4366-4378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sindre, H., H. Rollag, M. Degre, and K. Hestdal. 2000. Human cytomegalovirus induced inhibition of hematopoietic cell line growth is initiated by events taking place before translation of viral gene products. Arch. Virol. 145:99-111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stadler, M., M. K. Chelbi-Alix, M. H. Koken, L. Venturini, C. Lee, A. Saib, F. Quignon, L. Pelicano, M. C. Guillemin, C. Schindler, et al. 1995. Transcriptional induction of the PML growth suppressor gene by interferons is mediated through an ISRE and a GAS element. Oncogene 11:2565-2573. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wilkinson, G. W., C. Kelly, J. H. Sinclair, and C. Rickards. 1998. Disruption of PML-associated nuclear bodies mediated by the human cytomegalovirus major immediate early gene product. J. Gen. Virol. 79:1233-1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Winkler, M., S. A. Rice, and T. Stamminger. 1994. UL69 of human cytomegalovirus, an open reading frame with homology to ICP27 of herpes simplex virus, encodes a transactivator of gene expression. J. Virol. 68:3943-3954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yang, X., R. Khosravi-Far, H. Y. Chang, and D. Baltimore. 1997. Daxx, a novel Fas-binding protein that activates JNK and apoptosis. Cell 89:1067-1076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhong, S., S. Muller, S. Ronchetti, P. S. Freemont, A. Dejean, and P. P. Pandolfi. 2000. Role of SUMO-1-modified PML in nuclear body formation. Blood 95:2748-2752. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]