Abstract

Alpha/beta interferons (IFN-α/βs) are known to antagonize herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) infection by directly blocking viral replication and promoting additional innate and adaptive, antiviral immune responses. To further define the relationship between the adaptive immune response and IFN-α/β, the protective effect induced following the topical application of plasmid DNA containing the murine IFN-α1 transgene onto the corneas of wild-type and T-cell-deficient mice was evaluated. Mice homozygous for both the T-cell receptor (TCR) β- and δ-targeted mutations expressing no αβ or γδ TCR (αβ/γδ TCR double knockout [dKO]) treated with the IFN-α1 transgene succumbed to ocular HSV-1 infection at a rate similar to that of αβ/γδ TCR dKO mice treated with the plasmid vector DNA. Conversely, mice with targeted disruption of the TCR δ chain and expressing no γδ TCR+ cells treated with the IFN-α1 transgene survived the infection to a greater extent than the plasmid vector-treated counterpart and at a level similar to that of wild-type controls treated with the IFN-α1 transgene. By comparison, mice with targeted disruption of the TCR β chain and expressing no αβ TCR+ cells (αβ TCR knockout [KO]) showed no difference upon treatment with the IFN-α1 transgene or the plasmid vector control, with 0% survival following HSV-1 infection. Adoptively transferring CD4+ but not CD8+ T cells from wild-type but not IFN-γ-deficient mice reestablished the antiviral efficacy of the IFN-α1 transgene in αβ TCR KO mice. Collectively, the results indicate that the protective effect mediated by topical application of a plasmid construct containing the murine IFN-α1 transgene requires the presence of CD4+ T cells capable of IFN-γ synthesis.

The successful coexistence of viral pathogens with the mammalian host resides, in part, with the capacity of the virus to elude immune detection and subvert the immune response (76). A case in point is herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1), a virus prevalent within the human population, with 40 to 80% of the adult population worldwide infected (56). In the murine model, ocular HSV-1 infection results in an intense immune response, with natural killer (NK) cells (10), macrophages (15), and neutrophils (79) prevalent early during infection and followed by CD4+ T cells (57). Although these cells control viral replication either directly or through the production of antiviral and proinflammatory cytokines (6, 9, 17, 27, 33), the ensuing immune response can lead to the development of herpetic stromal keratitis (5, 34, 35, 72, 74, 80). In fact, pathological manifestations within the cornea have recently been associated with bystander activation of CD4+ T cells (23, 75).

Following infection in the eye, HSV-1 is transported back into the sensory ganglion (trigeminal ganglion [TG]), resulting in the up-regulation of major histocompatibility complex class I molecules on neurons and supporting cells (62, 63), inducing a robust immune response (12, 47, 66, 67). Although the immune response to the acute infection is quite dynamic, the virus utilizes a number of mechanisms to avoid detection or antagonize humoral and cell-mediated effector pathways. In evading immune surveillance, the virus has been found to down-regulate major histocompatibility complex class I expression by preventing translocation by the transporter associated with antigen-processing peptide into the endoplasmic reticulum (1, 37, 40, 69), thus preventing recognition by CD8+ T cells (28). In addition, components of the virus have been found to block the formation of the membrane attack complex (22) and inhibit antibody-dependent cell cytotoxicity (55). Independent of the immune response, HSV-1 is still capable of establishing a latent infection in the TG, by which it may reactivate under appropriate conditions (20).

Alpha/beta interferons (IFN-α/βs) are potent antiviral cytokines that control HSV-1 replication by hindering immediate-early and early gene expression (18, 51) and by blocking virus-induced death in the ocular mouse model (30, 36, 71). At the molecular level, IFN-α/β ligation to its receptor results in the activation of distinct yet related signaling pathways referred to as the Jak/STAT pathway (70). This results in the formation of a heterotrimeric complex known as ISGF3, which subsequently binds to the promoter region of IFN-inducible genes known collectively as the IFN-stimulated response element (29). Two prominent IFN-inducible gene products, 2′,5′-oligoadenylate synthetase and double-stranded RNA-activated protein kinase R, are involved in controlling ocular HSV-1 infection (44, 83). In vitro studies describe the late gene products γ134.5 and unique short region 11 inhibiting protein kinase R activity (13, 32), while the immediate-early gene product ICP0 antagonizes IFN action by unknown means (31, 54). More recently, HSV-1 has been found to prevent phosphorylation of STAT-1 and JAK-1, thereby disabling the signaling cascade for IFN-inducible genes (82). Based on this information, it would appear that HSV-1 has devoted a number of gene products to counter the host immune response, especially the action or signaling cascade of IFN-α/βs.

The present study was undertaken to further characterize the components mobilized during acute ocular HSV-1 infection in the presence of a plasmid construct expressing the murine IFN-α1 gene. A previous study found that the topical application of the murine IFN-α1 transgene onto the mouse cornea 24 h prior to infection suppressed HSV-1 replication in the eye and spread into the TG, reducing virus-mediated mortality and the establishment of a latent infection (58). An additional study implicated T cells in the protective effect (59). To more formally prove the involvement of T cells and distinguish between subsets that are critical in establishing an antiviral state following IFN-α1 transgene application, T-cell-deficient mice were used as recipients in adoptive transfer experiments. The results of these experiments clearly indicate that the presence of CD4+ T cells that are capable of generating IFN-γ are required to complement the viral antagonism induced by the IFN-α1 plasmid construct, maximizing the antiviral state.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Virus and cell line.

Vero cells originally obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, Va.) were cultured in RPMI 1640 (Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, Md.) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Life Technologies), an antibiotic and antimycotic solution (Life Technologies), and gentamicin (Life Technologies) (a final concentration of 20 μg of culture medium/ml). The cell cultures were incubated at 37°C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2 and 95% humidity. HSV-1 (McKrae strain) was used to infect Vero cells (multiplicity of infection = 0.01). Following an incubation of 24 to 48 h postinfection (p.i.) (>90% cytopathic effect), the supernatant was collected, clarified (500 × g, 15 min), and passed through a 2.0-μm-pore size filter. The virus was then pelleted (20,000 × g, 120 min) and washed twice in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS [pH 7.4]). Finally, the virus was diluted in PBS, generating a stock solution (1 × 108 to 10 × 108 PFU/ml) which was then titered, aliquoted, and stored at −80°C.

Infection of mice.

Homozygous male mice with targeted disruption of the T-cell receptor (TCR) β and δ chains (no αβ or γδ TCR+ T cells), TCR β chain (no αβ TCR+ T cells), TCR δ chain (no γδ TCR+ T cells), and IFN-γ gene and wild-type C57BL/6J controls were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, Maine). Mice were anesthetized with ketamine (100 mg/kg of body weight) and xylazine (10 mg/kg) in PBS administered intraperitoneally. Following scarification of the cornea, 100 μg of plasmid DNA alone or plasmid DNA containing the murine IFN-α1 transgene was topically applied to the eye in a volume of 3 μl of PBS. Twenty-four hours post-DNA application, the mice were again anesthetized, the cornea was scarified, and 1,000 PFU of HSV-1 was applied to each eye in a volume of 3 μl of PBS. In mouse recipients of syngeneic splenic leukocytes, 10 to 20 million splenic leukocytes or 1 to 6 million CD4+ or CD8+ T cells were intraperitoneally administered to recipients in a volume of 100 to 200 μl of RPMI 1640 6 days prior to in situ transfection with plasmid DNA and then infected with HSV-1. Mice were monitored for cumulative survival or euthanized at the indicated time point for tissue sampling. Animals were handled in accordance with the National Institutes of Health guidelines on the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (publication no. 85-23, revised 1996). All procedures were approved by the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Enrichment of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells.

Single-cell suspensions generated from the mechanical dispersion of spleens were washed twice in RPMI 1640 (Life Technologies). Following osmotic lysis of red blood cells with 0.84% NH4Cl, the remaining cells were counted and placed in 500 μl of degassed PBS containing 2 mM EDTA and 0.5% bovine serum albumin (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.). The cells were then positively selected for CD4+ or CD8+ cells by using LS+ separating columns and CD4 or CD8 magnetic microbeads according to the manufacturer's instructions (Miltenyi Biotech, Auburn, Calif.). To validate the enrichment process, isolated cells were analyzed for the percentage of CD3+ CD4+ and CD3+ CD8+ cells by using fluorescein isothiocyanate- and phycoerythrin-labeled antibodies to CD3, CD4, and CD8 markers and a FACSCalibur instrument (Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, Calif.). Enrichment ranged from 94 to 97%, with less than 1% contamination by the opposing T-cell subset.

Viral plaque assay.

At 3 or 7 days p.i., the eyes, TG, and brain stems (BS) of mice were removed, weighed, and homogenized in 0.5 ml of RPMI 1640 (Life Technologies). Supernatants were clarified by centrifugation (10,000 × g, 1 min), serially diluted, and titered for infectious virus on Vero cell monolayers in a 30-h plaque assay. Viral shedding in the tear film of wild-type and T-cell-deficient, HSV-1-infected mice was determined by swabbing mouse eyes and placing the cotton applicator in a 500-μl volume of RPMI 1640 containing 5% fetal bovine serum and a antimycotic and antibiotic solution for 1 h at 37°C. The sample was serially diluted, and titers were determined on Vero cell monolayers in a 30-h plaque assay.

Immunohistochemical staining for mononuclear cell infiltration.

The procedure for tissue preparation, processing, and staining of the eyes and TG for HSV-1 antigen and mononuclear cell infiltration has previously been described (59).

Statistics.

One-way analysis of variance and Tukey's test were used to determine significant (P < 0.05) differences between the viral titers recovered from the eyes, TG, and BS of plasmid vector- and IFN-α1 transgene-treated mice. The Mann-Whitney U test was used to determine the significant (P < 0.05) difference in the cumulative survival studies. All statistical analysis was performed using the GBSTAT program (Dynamic Microsystems, Silver Spring, Md.).

RESULTS

Viral clearance rate in the tear film of T-cell-deficient mice treated with plasmid vector or the IFN-α1 transgene.

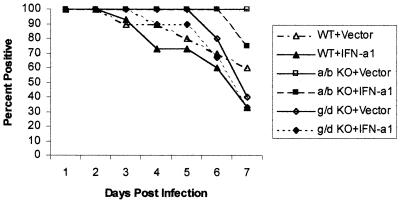

A previous study suggested that the clearance rate of HSV-1 from the tear film of immunized B-cell-deficient mice did not involve antibody but rather innate immunity and cytokines released from CD4+ T cells (16). To further this observation and establish the potential dependency of IFN-α/β for T-cell help in suppressing HSV-1 replication and shedding in the cornea, T-cell-deficient mice were topically treated with plasmid vector DNA or the IFN-α1 transgene and evaluated for the presence of infectious virus in the tear film during acute infection (1 to 7 days p.i.). In mice deficient of αβ+ and γδ+ T cells (αβ/γδ TCR double knockout [dKO]), HSV-1 was recovered in the tear film of 100% of the mice surveyed (days 1 to 7 p.i.) regardless of pretreatment with plasmid vector control or the IFN-α1 transgene (n = 10 mice/group). By comparison, plasmid vector- and IFN-α1 transgene-treated mice absent of γδ TCR+ T cells (γδ TCR knockout [KO]) showed a 40 or 67% clearance rate of HSV-1 from the tear film by day 7 p.i., respectively (Fig. 1). However, in the absence of αβ TCR+ T cells (αβ TCR KO), the clearance rate of HSV-1 from the tear film was 0 or 30% in plasmid vector- or IFN-α1 transgene-treated groups, respectively (Fig. 1). Wild-type mice treated with the plasmid vector or IFN-α1 transgene showed a viral clearance rate of 40 or 70%, respectively, by day 7 p.i. (Fig. 1). There was no significant difference in the viral titers recovered from the tear film of any of the groups of infected mice during the acute infection. Taken together, these results suggest that in the absence of αβ TCR+ T cells, there is a marked decrease in the clearance rate of infectious virus from the tear film of ocularly infected mice treated with the IFN-α1 transgene, which is evident primarily at the latter time points p.i. (i.e., days 6 to 7 p.i.).

FIG. 1.

αβ TCR+ cells facilitate HSV-1 clearance in the tear film following topical treatment with the IFN-α1 transgene. Wild-type (WT) mice or mice deficient in αβ (a/b KO) or γδ (g/d KO) TCR+ cells (n = 10 to 15/group) were treated with either the plasmid vector control or plasmid containing the IFN-α1 transgene (100 μg/eye) 24 h prior to infection with HSV-1 (1,000 PFU/eye). Mouse corneas were swabbed with a sterile cotton applicator stick at 24-h intervals during acute infection (days 1 to 7 p.i.). The virus was recovered from the stick and assayed for infectious virus by plaque assay. Recoverable infectious virus ranged from 10 to 30,000 PFU/eye.

CD4+ αβ TCR+ T cells are required for IFN-α1 transgene antagonism of HSV-1 replication and virus-mediated mortality.

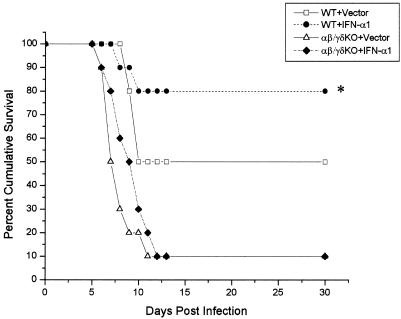

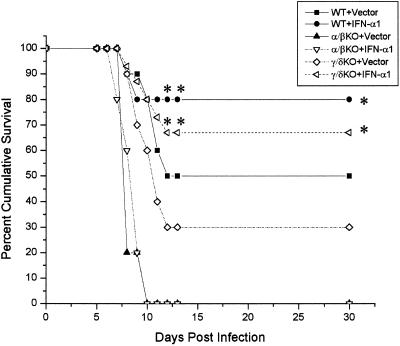

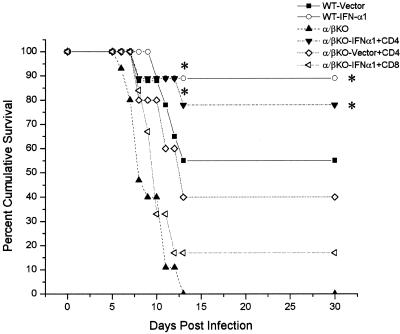

The previous results suggested that T cells (primarily αβ TCR+ cells) are required in order for the IFN-α1 transgene to antagonize local viral shedding in the tear film. To determine if T cells are required to block the progression of the virus, ultimately preventing the death of the host, an experiment was performed in which wild-type or αβ/γδ TCR dKO mice received plasmid vector or plasmid containing the IFN-α1 in the cornea 24 h prior to infection. The mice were then monitored for survival following ocular infection with HSV-1. The results show that in the absence of T cells, 90% of the αβ/γδ dKO mice succumbed to the infection regardless of treatment with the plasmid vector control or the IFN-α1 transgene (Fig. 2). By comparison and similar to previous results, there was a significant increase in the survival of mice treated with the IFN-α1 transgene in comparison to animals treated with the plasmid vector control providing the T-cell population was intact (Fig. 2). Since γδ T lymphocytes have previously been found to recognize HSV-1 (41), γδ TCR KO mice were compared to αβ TCR KO mice in the presence or absence of the IFN-α1 transgene containing plasmid. In the absence of αβ TCR T cells, the IFN-α1 transgene had no effect on the survival of mice infected with HSV-1 (Fig. 3). In contrast, similar to intact, wild-type mice, γδ TCR KO mice treated with the transgene were found to survive to a greater extent than the plasmid vector-treated γδ TCR KO controls (Fig. 3). In addition, although the survival of the γδ TCR KO control mice was reduced compared to that of the wild-type animals infected with HSV-1, there was no significant difference.

FIG. 2.

T cells are required to enhance survival of the IFN-α1 transgene against ocular HSV-1 infection. Wild-type (WT) mice and mice deficient in αβ and γδ TCR+ cells (αβ/γδ KO; n = 10/group) were treated with the plasmid vector control or plasmid containing the IFN-α1 transgene 24 h prior to infection with HSV-1 (1,000 PFU/eye). Mice were then monitored for cumulative survival. This figure is a summary of two experiments (n = 5 mice/group/experiment). ∗, P < 0.05 comparing the WT mice treated with the vector (WT+Vector) to the WT mice treated with the IFN-α1 transgene (WT+IFN-α1) as determined by the Mann-Whitney U test. Both WT groups were significantly different (P < 0.05) compared to the αβ/γδ KO mice.

FIG. 3.

αβ TCR+ T lymphocytes are required for antiviral efficacy induced following topical treatment of the eye with the IFN-α1 transgene. Wild-type (WT) mice or mice deficient in αβ (α/βKO) or γδ (γ/δKO) TCR+ cells (n = 10 to 15/group) were treated with the plasmid vector control or plasmid containing the IFN-α1 transgene 24 h prior to infection with HSV-1 (1,000 PFU/eye). Mice were then monitored for cumulative survival. This figure is a summary of two to three experiments with n = 5 mice/group/experiment. ∗, P < 0.05 comparing the WT or γδ KO mice treated with the vector (WT+Vector or γ/δKO+Vector) to the corresponding counterparts treated with the IFN-α1 transgene (WT+IFN-α1) as determined by the Mann-Whitney U test.

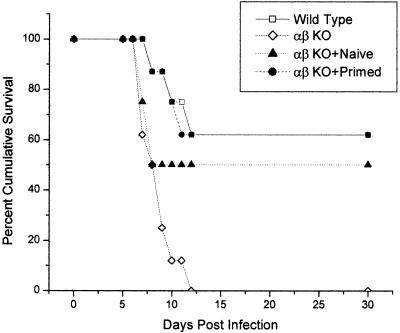

To distinguish between subpopulations of T cells that might be involved in the antiviral efficacy mediated by the IFN-α1 transgene, adoptive transfer experiments were undertaken. Since T cells transferred into T-cell-deficient mice rapidly expand (49), we tested the adoptive transfer strategy, comparing the number of cells transferred versus the number in the source (i.e., naive versus primed) of the donor cells. The results showed that 1 × 107 to 2 × 107 cells transferred from naive donors provide protection against ocular HSV-1 infection, nearly equivalent to that provided by 1 × 107 to 2 × 107 cells from primed donors, given a 6-day window of expansion prior to viral infection (Fig. 4). Based on these results, we calculated that between 1 × 106 and 2 × 106 CD8+ T cells (approximately 10% of splenic lymphocytes are CD3+ CD8+) or between 3 × 106 and 6 × 106 CD4+ T cells (approximately 30% of splenic lymphocytes are CD3+ CD4+) would be sufficient to distinguish the population which contributes to the transgene effect. Therefore, highly enriched CD3+ CD4+ or CD3+ CD8+ T cells obtained from the spleens of naive syngeneic donors were transferred to αβ TCR KO recipients. Six days posttransfer, the animals were treated with plasmid vector or the IFN-α1 transgene. Twenty-four hours posttransfection, the mice were infected with HSV-1 (1,000 PFU/eye) and monitored for cumulative survival. The results show that CD4+ T cells restored resistance to HSV-1 infection in αβ TCR KO mice (Fig. 5). More importantly, CD4+ but not CD8+ T cells were required to facilitate the enhanced effect in the survival of mice treated with the IFN-α1 transgene (Fig. 5). Even when equivalent numbers (2 × 106 cells) of donor CD4+ or CD8+ T cells were used, only recipients of the CD4+ T cells exhibited efficacy in the presence of the IFN-α1 transgene (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

Adoptive transfer of wild-type spleen cells restores resistance to ocular HSV-1 in αβ TCR-deficient mice. Mice (n = 8/group) deficient in αβ TCR+ T cells (αβ KO) received 1 × 107 to 2 × 107 spleen cells from syngeneic naive (αβ KO+Naive) or primed (αβ KO+Primed) donors 6 days prior to infection with HSV-1 (1,000 PFU/eye). Wild-type and αβ TCR-deficient mice (n = 8/group) served as controls. Mice were monitored for cumulative survival. This experiment is a summary of two experiments, with four mice per group per experiment.

FIG. 5.

CD4+ T lymphocytes are required for restoration of resistance to ocular HSV-1 infection and enhancement in survival following IFN-α1 transgene application. Mice (n = 6 to 11/group) deficient in αβ TCR+ T cells (α/βKO) received 1 × 106 to 3 × 106 CD8+ T cells or 3 × 106 to 6 × 106 CD4+ T cells from syngeneic naive donors 6 days prior to topical application with plasmid vector or plasmid containing the IFN-α1 transgene onto the cornea. Twenty-four hours post-in situ transfection, the mice were infected with HSV-1 (1,000 PFU/eye) and monitored for cumulative survival. Wild-type (WT) and αβ KO mice (n = 10 to 11/group) served as controls. ∗, P < 0.05 comparing the WT or αβ KO+CD4 mice treated with the counterparts treated with IFN-α1 transgene to the plasmid vector (WT-Vector or α/βKO-Vector+CD4) as determined by the Mann-Whitney U test.

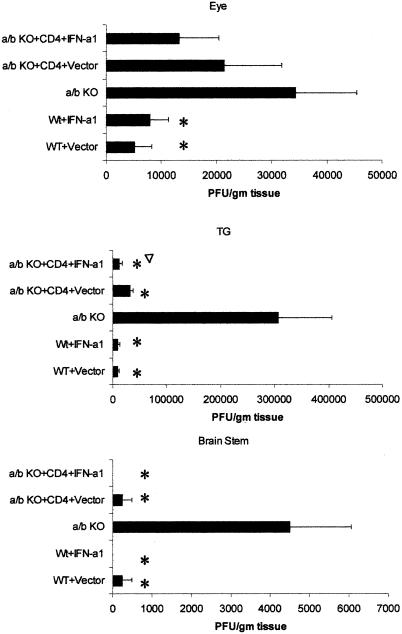

The presence of CD4+ T lymphocytes impedes HSV-1 replication.

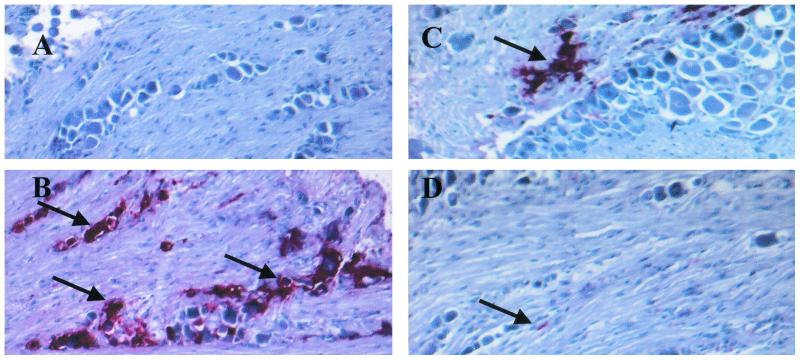

To further analyze the impact of CD4+ T cells in the presence of the IFN-α1 transgene on ocular HSV-1 infection, viral titers were measured in the eyes, TG, and BS of HSV-1-infected mice. Wild-type mice treated with the plasmid vector or IFN-α1 transgene showed a significant reduction in infectious virus recovered from the eyes day 6 p.i. in comparison to that for the αβ TCR KO controls (Fig. 6). Although viral titers were reduced in the eyes of αβ TCR KO recipients of CD4+ T cells treated with the plasmid vector or the IFN-α1 transgene in comparison to those for the αβ TCR KO controls, the levels did not reach significance. Furthermore, even though viral titers were modestly reduced in the eyes of the wild-type mice compared to those of the αβ TCR KO controls, similar levels of infiltrating mononuclear cells were present in the cornea during the acute infection (Table 1). By comparison, the impact of the presence of CD4+ T cells on viral titers was observed in the TG. Specifically, αβ TCR KO recipients of CD4+ T cells showed a significant reduction in viral loads in the TG in comparison to αβ TCR KO control mice on day 6 p.i. (Fig. 6). In addition, the viral load of the TG from αβ TCR KO recipients of CD4+ T cells treated with the IFN-α1 transgene was significantly reduced threefold compared to that for the αβ TCR KO recipients of CD4+ T cells treated with the plasmid vector (Fig. 6). HSV-1 antigen expression in the TG of αβ TCR KO recipients of CD4+ T cells treated with the IFN-α1 was also reduced in comparison to that in the TG from αβ TCR KO control mice or αβ TCR KO recipients of CD4+ T cells treated with the plasmid vector (Fig. 7). Consistent with a reduction in the viral load in the ganglions of mice treated with the IFN-α1 transgene, the presence of the transgene also affected the viral titer recovered from the BS. Specifically, HSV-1 was not recovered from 0 of 6 wild-type or αβ TCR KO recipients of CD4+ T cells treated with the IFN-α1 transgene in comparison to 2 of 6 wild-type or αβ TCR KO recipients of CD4+ T cells treated with the plasmid vector and 6 of 6 αβ TCR KO control mice (Fig. 6).

FIG. 6.

HSV-1 replication is hampered by CD4+ T cells in the TG and the IFN-α1 transgene in the BS. Mice deficient in αβ TCR KO (n = 6/group) received 3 × 106 CD4+ T cells from syngeneic naive donors 6 days prior to topical application with plasmid vector or plasmid containing the IFN-α1 transgene onto the cornea. Wild-type (WT) mice (n = 6/group) treated with the plasmid vector or IFN-α1 transgene (100 μg of DNA/eye) served as controls. Twenty-four hours post-in situ transfection, the mice were infected with HSV-1 (1,000 PFU/eye). The eyes, TG, and BS were collected from the infected mice 6 days p.i. and assessed for viral titers by plaque assay. This figure is a summary of two experiments (three mice per group per experiment). ∗, P < 0.05 comparing the WT or αβ TCR recipients of CD4+ T cells to the αβ TCR KO mice. ▿, P < 0.05 comparing the transgene-treated mice to the plasmid vector-treated counterparts.

TABLE 1.

Cellular infiltration in the eyes of HSV-1-infected wild-type and αβ TCR KO mice day 6 p.i.a

| Group | No. of infiltrating cellsb |

|---|---|

| Wild type + plasmid vector | 481 ± 59 |

| Wild type + IFN-α1 transgene | 584 ± 56 |

| αβ TCR KO | 501 ± 50 |

| αβ TCR KO recipients of CD4+ T cells + plasmid vector | 452 ± 61 |

| αβ TCR KO recipients of CD4+ T cells + IFN-α1 transmid | 474 ± 36 |

Wild-type mice, αβ TCR KO mice, and αβ TCR KO recipients of CD4+ T cells were treated with the indicated plasmid DNA (100 μg/eye) and subsequently infected with HSV-1 (1,000 PFU/eye) 24 h later. The eyes and TG were collected from the infected mice 6 days p.i. and assessed for mononuclear cell infiltration (eyes) by indirect immunohistochemical staining. Uninfected eyes served as negative controls. Results are representative of two independent experiments (three mice per group per experiment).

Numbers represent the mean ± standard error of the mean obtained from the eyes of six mice, with each animal represented by six tissue sections.

FIG. 7.

HSV-1 antigen expression in the TG is reduced in αβ TCR knockout recipients of CD4+ T cells treated with the IFN-α1 transgene. Mice deficient in αβ TCR KO (n = 4/group) received 3 × 106 CD4+ T cells from syngeneic naive donors 6 days prior to topical application with plasmid vector or plasmid containing the IFN-α1 transgene onto the cornea. Twenty-four hours posttransfection, the mice were infected with HSV-1 (1,000 PFU/eye). Wild-type mice (n = 4/group) treated with the IFN-α1 transgene (100 μg of DNA/eye) served as the positive control. Six days p.i., the mice were euthanized and the TG was removed and assessed for HSV-1 antigen expression by indirect immunohistochemical staining. (A) wild-type mice plus the IFN-α1 transgene; (B) αβ TCR knockout mice; (C) αβ TCR knockout mice plus the plasmid vector; (D) αβ TCR knockout mice plus the IFN-α1 transgene. Arrows indicate the presence of viral antigen. Magnification, ×400.

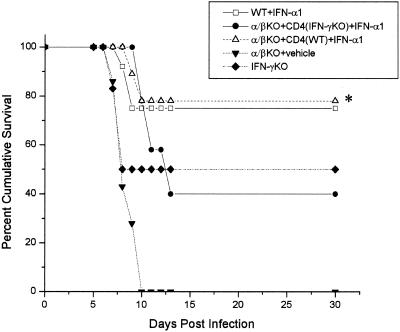

IFN-γ is required for the protective effect elicited by the IFN-α1 transgene.

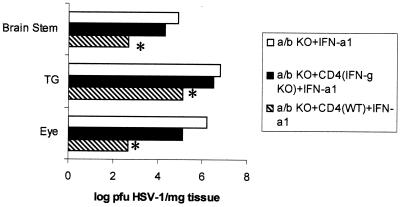

IFN-γ is a dominant proinflammatory cytokine that influences cell-mediated immunity in response to viral infections in the central nervous system (61) and eye (9, 25). Since IFN-γ expression colocalizes with T-cell infiltration during acute HSV-1 infection (11) and CD4+ T cells are required for the antiviral efficacy of the IFN-α1 transgene, it was hypothesized that IFN-γ provided a basis of support in the IFN-α1 action against HSV-1. To address this notion, αβ TCR KO mice receiving highly enriched CD4+ T cells from wild-type mice or mice deficient in IFN-γ and treated with the IFN-α1 transgene were assessed for sensitivity to HSV-1 infection. The results show that the protective effect elicited by the IFN-α1 transgene against HSV-1-mediated mortality was only active in αβ TCR KO recipients of CD4+ T cells from wild-type but not IFN-γ-deficient animals (Fig. 8). In a similar fashion, significantly reduced viral titers were recovered from the eyes, TG, and BS of αβ TCR KO recipients of CD4+ T cells from wild-type mice compared to αβ TCR KO recipients of CD4+ T cells from IFN-γ animals in which both groups were treated with the IFN-α1 transgene (Fig. 9).

FIG. 8.

IFN-γ is required for IFN-α1 transgene efficacy against HSV-1. Mice deficient in αβ TCR KO (n = 11/group) received 3 × 106 CD4+ T cells from syngeneic wild- type or IFN-γ deficient donors 6 days prior to the topical application with the plasmid containing the IFN-α1 transgene (100 μg og DNA) onto the cornea. Wild-type (WT) mice treated with the IFN-α1 transgene (100 μg of DNA/eye), αβ TCR KO mice, and IFN-γ deficient mice served as controls. Twenty-four hours post-in situ transfection, the mice were infected with HSV-1 (1,000 PFU/eye) and monitored for cumulative survival. This figure is a summary of three experiments (three to five mice per group per experiment). ∗, P < 0.05 comparing the αβ TCR KO recipients of CD4+ T cells from wild-type, syngeneic donors with the αβ TCR KO recipients of CD4+ T cells from IFN-γ deficient, syngeneic donors; both groups were treated with the transgene.

FIG. 9.

Viral titers are reduced in the eyes and TG of αβ TCR KO recipients of CD4+ T cells from wild-type versus IFN-γ-deficient donors. Mice deficient in αβ TCR KO (n = 4/group) received 3 × 107 CD4+ T cells from syngeneic wild-type or IFN-γ-deficient donors 6 days prior to the topical application with the plasmid containing the IFN-α1 transgene (100 μg of DNA) onto the cornea. Twenty-four hours post-in situ transfection, the mice were infected with HSV-1 (1,000 PFU/eye). The eyes, TG, and BS were collected from the infected mice 7 days p.i. and measured for infectious virus by plaque assay. ∗, P < 0.01 comparing the viral titers of the αβ TCR KO recipients of CD4+ T cells from wild-type versus those of the IFN-γ-deficient donors; both groups were treated with the IFN-α1 transgene.

DISCUSSION

IFN-γ is a proinflammatory cytokine predominantly secreted by activated T cells and NK cells in response to stimuli, including viral antigens (8). Moreover, IFN-γ is observed in both the eye (33) and TG (67), coinciding with CD4+-T-lymphocyte infiltration in ocular HSV-1 infection (12, 57, 66). Not only does IFN-γ contribute to the host defense against acute HSV-1 infection (25, 81) but evidence suggests that IFN-γ may contribute to inhibiting reactivation of latent virus (46). The present findings unequivocally show that CD4+ T cells deficient in IFN-γ production negate the antiviral efficacy of the IFN-α1 transgene, indicating a role for IFN-γ in the protective effect induced by the IFN-α1 transgene against ocular HSV-1. At least two scenarios in which IFN-γ is required for the antiviral action of the IFN-α1 transgene product are envisioned. Previous studies have found the absence of IFN-γ does not modify the viral titers recovered from the peripheral or central nervous system (11, 45). Therefore, one possible means of protection elicited by IFN-γ is at the level of the neurons. Specifically, the data suggest that IFN-γ blocks neuronal apoptosis through the induction of Bcl-2 expression (24, 26). However, the data presented herein clearly show that αβ TCR KO recipients of CD4+ T lymphocytes from wild-type mice possess significantly less virus in the eyes and nervous system compared to recipients of CD4+ T cells from IFN-γ-deficient mice. We interpret these results to suggest that a reduction in virus-mediated death is a direct result of the suppression of viral replication in the infected tissue. Therefore, a second theory of IFN-γ action in unison with IFN-α1 against HSV-1 infection is probable. To this end, it is tempting to speculate that the presence of IFN-γ synergizes with the antiviral action of the IFN-α1 transgene product in preventing HSV-1 transcription. Along these lines, in vitro studies have found that the addition of IFN-α along with IFN-γ blocks HSV-1 growth in corneal fibroblasts, exceeding the additive effect of either IFN alone (3). By means of explanation, an earlier work found functional complementation between two trans-activating factors induced by IFN-α and IFN-γ, resulting in the strong induction of ISGF3 (4). Therefore, the expression of both IFN-α1 and IFN-γ within the eyes or TG of HSV-1 infected mice may directly prevent HSV-1 replication or, alternatively, may facilitate the activity of additional cytokines produced by CD4+ T lymphocytes in suppressing HSV-1 pathogenesis. It is apparent from the results that alone, the IFN-α1 transgene does not prevent viral replication, viral spread, or mortality of the host. In addition, the lack of the antiviral state induced by the IFN-α1 transgene in the absence of an intact immune system against HSV-1 underscores the successful anti-IFN mechanism developed by HSV-1 in countering the innate IFN response to infection (13, 31, 32, 54, 82).

The present findings indicate that CD4+ but not CD8+ T lymphocytes are tantamount to the protective effect induced following the topical application of the IFN-α1 transgene onto the corneas of mice subsequently infected with HSV-1. CD8+ T lymphocytes are thought to clear virus from the TG (68) through an IFN-γ-independent mechanism during acute infection (39, 78). CD4+ T lymphocytes have previously been associated with protective immunization against ocular HSV-1 infection (52) but may also contribute to the pathogenesis associated with herpetic keratitis (14, 43). In contrast to the present findings, we reported that either CD4- or CD8-cell depletion blocked the antiviral efficacy of the IFN-α1 transgene against ocular HSV-1 (59). In that study, antibody to the CD8α chain was employed to deplete CD8-expressing cells from the murine host prior to infection. Unfortunately, such an approach would likely deplete CD8α-expressing dendritic cells, which are thought to drive the development of Th1 T lymphocytes through interleukin-12 expression (48). Freshly isolated murine dendritic cell subpopulations or cell lines have recently been shown to produce IFN-α/βs in response to various stimuli (2, 38), including HSV-1 (21). Moreover, we have recently shown that the topical application of a plasmid DNA LacZ reporter construct onto the cornea results in the expression of the reporter gene by CD11c+ cells in the spleen (60). Since the majority of CD8α-expressing dendritic cells are CD11c+ (53), the depletion of such cells would predictably reduce or eliminate the expression of the transgene distal to the application site and significantly impact cells thought to produce vast quantities of IFN-α/β following HSV-1 infection. A significant reduction in IFN-α/β production would inevitably reduce costimulatory expression on antigen-presenting cells including dendritic cells (7), impairing CD8+- and, to a lesser extent, CD4+-T-cell responses to HSV (19). Likewise, the absence of CD4 help in the αβ TCR KO recipients of CD8+ T cells might also have negated appropriate arming of CD8+ effector cells, thereby reducing the efficiency of activation of these cells.

γδ T cells are an important component of the innate immune response to viral infection (65). Relative to HSV-1 infection, depletion of γδ T cells exacerbates the neurovirulence of the infection (64), reducing early production of IFN-γ found in the TG days 3 to 5 p.i. (42). The present study found a modest but insignificant reduction in the survival of γδ TCR KO mice compared to that of the wild-type controls in which both groups were treated with the plasmid vector DNA. However, γδ TCR KO mice treated with the IFN-α1 transgene clearly showed an efficacious effect similar to that expressed in the wild-type mice, demonstrating that the absence of such cells does not modify the protective effect of the IFN-α/β. In the absence of αβ TCR-expressing cells, mice succumbed to infection regardless of the presence of the IFN-α1 transgene. Taken together, these results suggest that even in the presence of γδ TCR+ cells, HSV-1 ocular infection ultimately results in the death of the αβ TCR KO host. The contrast in our results to that previously reported showing that mice deficient in αβ TCR+ cells did not succumb to infection without depleting γδ TCR+ cells (64) is likely explained by the use of different virus (RE versus the McKrae strain reported herein) and mouse (BALB/c versus the C57BL/6 reported herein) strains.

The absence of αβ TCR+ T cells was also found to modify the control of viral replication proximal to the site of initial acute infection, the cornea. These results suggest that T cells (predominantly CD4+ T lymphocytes) and their secreted products are important components in clearing replicating virus from the cornea and supporting tissue during acute infection (16). Since cytokines secreted by CD4+ T lymphocytes including interleukin-2 and IFN-γ have been implicated in facilitating polymorphonuclear infiltration into the cornea (73) and tear film viral titer levels (27), these effector molecules are likely candidates in promoting the clearance of HSV-1 from the eye in the presence of the IFN-α1 transgene. Although similar numbers of mononuclear cells were found infiltrating the corneal stroma of the αβ TCR knockout recipients of CD4+ T cells in comparison to that of the αβ TCR knockout mice, potential differences in the phenotype of the infiltrating cells have not been determined. However, these data suggest that the absence of αβ TCR+ T lymphocytes increases the longevity of virus recovered from the tear film, ultimately promoting additional time for viral replication in the eye and spread into the nervous system of the host.

In summary, the present findings exemplify the marriage between the innate and adaptive immune systems in response to an infection with a highly evolved microbial pathogen. Not only does IFN-α/β block viral replication through the induction of endogenous antiviral pathways (29) but it provides a stimulus to promote T-cell proliferation (77), prolonging the lifespan of activated T lymphocytes (50). In promoting T-cell survival, IFN-α/βs may increase the pool of memory T cells specific for the antigenic stimulus. To this end, a preliminary study has found that the percentage of splenic CD4+ T cells secreting IFN-γ in response to recall HSV-1 antigen is fourfold higher if the cells are obtained from mice treated with the IFN-α1 transgene in comparison to mice treated with the plasmid vector control (D. J. J. Carr, unpublished observation). Whether this observation holds true for T cells within the sensory ganglion of latently infected mice has not been determined. Future studies are required to more fully dissect the level, location (eyes versus TG), and mechanism(s) by which IFN-α/βs interact with CD4+ T cells and IFN-γ in preventing HSV-1 replication, morbidity, and mortality.

Acknowledgments

We thank Benitta Philip-Johns for her technical assistance. The original plasmid construct containing the IFN-α1 was graciously provided by Iain Campbell (Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, Calif.).

This work was supported by USPHS grant EY12409, NEI core grant EY12190, an unrestricted grant from the Research to Prevent Blindness (RPB) Inc., and an RPB Stein Research Professorship award (D.J.J.C).

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahn, K., T. H. Meyer, S. Uebel, P. Sempe, H. Djaballah, Y. Yang, P. A. Peterson, K. Fruh, and R. Tampe. 1996. Molecular mechanism and species specificity of TAP inhibition by herpes simplex virus protein ICP47. EMBO J. 15:3247-3255. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Asselin-Paturel, C., A. Boonstra, M. Dalod, I. Durand, N. Yessaad, C. Dezutter-Dambuyant, A. Vicari, A. O'Garra, C. Biron, F. Briere, and G. Trinchieri. 2001. Mouse type I IFN-producing cells are immature APCs with plasmacytoid morphology. Nat. Immunol. 2:1144-1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Balish, M. J., M. E. Abrams, A. M. Pumfery, and C. R. Brandt. 1992. Enhanced inhibition of herpes simplex virus type 1 growth in human corneal fibroblasts by combinations of interferon-α and -γ. J. Infect. Dis. 166:1401-1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bandyopadhyay, S. K., D. V. R. Kalvakolanu, and G. C. Sen. 1990. Gene induction by interferons: functional complementation between trans-acting factors induced by alpha interferon and gamma interferon. Mol. Cell. Biol. 10:5055-5063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bauer, D., S. Mrzyk, N. Van Rooijen, K.-P. Steuhl, and A. Heiligenhaus. 2001. Incidence and severity of herpetic stromal keratitis: impaired by the depletion of lymph node macrophages. Exp. Eye Res. 72:261-269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Benencia, F., M. C. Courreges, G. Gamba, H. Cavalieri, and E. J. Massouh. 2001. Effect of aminoguanidine, a nitric oxide synthase inhibitor, on ocular infection with herpes simplex virus in Balb/c mice. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 42:1277-1284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Biron, C. A. 2001. Interferons α and β as immune regulators—a new look. Immunity 14:661-664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boehm, U., T. Klamp, M. Groot, and J. C. Howard. 1997. Cellular responses to interferon-γ. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 15:749-795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bouley, D. M., S. Kanangat, W. Wire, and B. T. Rouse. 1995. Characterization of herpes simplex virus type-1 infection and herpetic stromal keratitis development in IFN-γ knockout mice. J. Immunol. 155:3964-3971. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brandt, C. R., and C. A. Salkowski. 1992. Activation of NK cells in mice following corneal infection with herpes simplex virus type-1. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 33:113-120 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cantin, E., B. Tanamachi, H. Openshaw, J. Mann, and K. Clarke. 1999. Gamma interferon (IFN-γ) receptor null-mutant mice are more susceptible to herpes simplex virus type 1 infection than IFN-γ ligand null-mutant mice. J. Virol. 73:5196-5200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cantin, E. M., D. R. Hinton, J. Chen, and H. Openshaw. 1995. Gamma interferon expression during acute and latent nervous system infection by herpes simplex virus type 1. J. Virol. 69:4898-4905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cassady, K. A., M. Gross, and B. Roizman. 1998. The herpes simplex virus US11 protein effectively compensates for the γ134.5 gene if present before activation of protein kinase R by precluding its phosphorylation and that of the α subunit of eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2. J. Virol. 72:8620-8626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen, H., and R. L. Hendricks. 1998. B7 costimulatory requirements of T cells at an inflammatory site. J. Immunol. 160:5045-5052. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cheng, H., T. M. Tumpey, H. F. Staats, N. van Rooijen, J. E. Oakes, and R. N. Lausch. 2000. Role of macrophages in restricting herpes simplex virus type 1 growth after ocular infection. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 41:1402-1409. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Daheshia, M., S. Deshpande, S. Chun, N. A. Kuklin, and B. T. Rouse. 1999. Resistance to herpetic stromal keratitis in immunized B-cell-deficient mice. Virology 257:168-176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Daheshia, M., S. Kanangat, and B. T. Rouse. 1998. Production of key molecules by ocular neutrophils early after herpetic infection of the cornea. Exp. Eye Res. 67:619-624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.De Stasio, P. R., and M. W. Taylor. 1990. Specific effect of interferon on the herpes simplex virus type 1 transactivation event. J. Virol. 64:2588-2593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Edelmann, K. H., and C. B. Wilson. 2001. Role of CD28/CD80-86 and CD40/CD154 costimulatory interactions in host defense to primary herpes simplex virus infection. J. Virol. 75:612-621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ellison, A. R., L. Yang, C. Voytek, and T. P. Margolis. 2000. Establishment of latent herpes simplex virus type 1 infection in resistant, sensitive, and immunodeficient mouse strains. Virology 268:17-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eloranta, M. L., K. Sandberg, P. Ricciardi-Castagnoli, M. Lindahl, and G. V. Alm. 1997. Production of interferon-alpha/beta by murine dendritic cell lines stimulated by virus and bacteria. Scand. J. Immunol. 46:235-241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Friedman, H. M., G. H. Cohen, R. J. Eisenberg, C. A. Seidel, and D. B. Cines. 1984. Glycoprotein C of herpes simplex virus 1 acts as a receptor for the C3b complement component in infected cells. Nature 309:633-635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gangappa, S., J. S. Babu, J. Thomas, M. Daheshia, and B. T. Rouse. 1998. Virus-induced immunoinflammatory lesions in the absence of viral antigen recognition. J. Immunol. 161:4289-4300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Geiger, K. D., D. Gurushantayah, E. L. Howes, G. A. Lewandowski, F. E. Bloom, J. C. Reed, and N. E. Sarvetnick. 1995. Cytokine mediated survival from lethal HSV-infection: role of programmed cell death. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:3411-3415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Geiger, K. D., E. L. Howes, and N. Sarvetnick. 1994. Ectopic expression of gamma interferon in the eye protects transgenic mice from intraocular herpes simplex virus type 1 infections. J. Virol. 68:5556-5567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Geiger, K. D., T. C. Nash, S. Sawyer, T. Krahl, G. Patstone, J. C. Reed, S. Krajewski, D. Dalton, M. J. Buchmeier, and N. Sarvetnick. 1997. Interferon-γ protects against herpes simplex virus type 1-mediated neuronal death. Virology 238:189-197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ghiasi, H., S. Cai, S. M. Slanina, G.-C. Perng, A. B. Nesburn, and S. L. Wechsler. 1999. The role of interleukin (IL)-2 and IL-4 in herpes simplex virus type 1 ocular replication and eye disease. J. Infect. Dis. 179:1086-1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goldsmith, K., W. Chen, D. C. Johnson, and R. L. Hendricks. 1998. Infected cell protein (ICP) 47 enhances herpes simplex virus neurovirulence by blocking the CD8+ T cell response. J. Exp. Med. 187:341-348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goodbourn, S., L. Didcock, and R. E. Randall. 2000. Interferons: cell signalling, immune modulation, antiviral responses and virus countermeasures. J. Gen. Virol. 81:2341-2364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Halford, W. P., L. A. Veress, B. M. Gebhardt, and D. J. J. Carr. 1997. Innate and acquired immunity to herpes simplex virus type 1. Virology 236:328-337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Härle, P., B. Sainz, Jr., D. J. J. Carr, and W. P. Halford. 2002. The immediate-early protein, ICP0, is essential for the resistance of herpes simplex virus to interferon-α/β. Virology 293:295-304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.He, B., M. Gross, and B. Roizman. 1997. The γ134.5 protein of herpes simplex virus 1 complexes with protein phosphatase 1 α to dephosphorylate the α subunit of the eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2 and preclude the shutoff of protein synthesis by double-stranded RNA-activated protein kinase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:843-848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.He, J., H. Ichimura, T. Iida, M. Minami, K. Kobayashi, M. Kita, C. Sotozono, Y.-I. Tagawa, Y. Iwakura, and J. Imanishi. 1999. Kinetics of cytokine production in the cornea and trigeminal ganglion of C57BL/6 mice after corneal HSV-1 infection. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 19:609-615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hendricks, R. L., M. Janowicz, and T. M. Tumpey. 1992. Critical role of corneal Langerhans cells in the CD4- but not CD8-mediated immunopathology in herpes simplex virus-1-infected mouse corneas. Exp. Eye Res. 148:2522-2529. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hendricks, R. L., T. M. Tumpey, and A. Finnegan. 1992. IFN-γ and IL-2 are protective in the skin but pathologic in the corneas of HSV-1-infected mice. J. Immunol. 149:3023-3028. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hendricks, R. L., P. C. Weber, J. L. Taylor, A. Koumbis, T. M. Tumpey, and J. C. Glorioso. 1991. Endogenously produced interferon α protects mice from herpes simplex virus type 1 corneal disease. J. Gen. Virol. 72:1601-1610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hill, A., P. Jugovic, I. York, G. Russ, J. Bennink, J. Yewdell, H. Ploegh, and D. Johnson. 1995. Herpes simplex virus turns off the TAP to evade host immunity. Nature 375:411-415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hochrein, H., K. Shortman, D. Vremec, B. Scott, P. Hertzog, and M. O'Keefe. 2001. Differential production of IL-12, IFN-α, and IFN-γ by mouse dendritic cell subsets. J. Immunol. 166:5448-5455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Holterman, A.-X., K. Rogers, K. Edelmann, D. M. Koelle, L. Corey, and C. B. Wilson. 1999. An important role for major histocompatibility complex class I-restricted T cells, and a limited role for gamma interferon, in protection of mice against lethal herpes simplex virus infection. J. Virol. 73:2058-2063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jennings, S. R., P. L. Rice, E. D. Kloszewski, R. W. Anderson, D. L. Thompson, and S. S. Tevethia. 1985. Effect of herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2 on surface expression of class I major histocompatibility complex antigens on infected cells. J. Virol. 56:757-766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Johnson, R. M., D. W. Lancki, A. I. Sperling, R. F. Dick, P. G. Spear, F. W. Fitch, and J. A. Bluestone. 1992. A murine CD4-, CD8- T cell receptor-γδ T lymphocyte clone specific for herpes simplex virus glycoprotein I. J. Immunol. 148:983-988. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kodukula, P., T. Liu, N. Van Rooijen, M. J. Jager, and R. L. Hendricks. 1999. Macrophage control of herpes simplex virus type 1 replication in the peripheral nervous system. J. Immunol. 162:2895-2905. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Koelle, D. M., S. N. Reymond, H. Chen, W. W. Kwok, C. McClurkan, T. Gyaltsong, E. W. Petersdorf, W. Rotkis, A. R. Talley, and D. A. Harrison. 2000. Tegument-specific, virus-reactive CD4 T cells localize to the cornea in herpes simplex virus interstitial keratitis in humans. J. Virol. 74:10930-10938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Leib, D. A., M. A. Machalek, B. R. G. Williams, R. H. Silverman, and H. W. Virgin. 2000. Specific phenotypic restoration of an attenuated virus by knockout of a host resistance gene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:6097-6101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lekstrom-Himes, J. A., R. A. LeBlanc, L. Pesnicak, M. Godleski, and S. E. Straus. 2000. Gamma interferon impedes the establishment of herpes simplex virus type 1 latent infection but has no impact on its maintenance or reactivation in mice. J. Virol. 74:6680-6683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liu, T., K. M. Khanna, B. N. Carriere, and R. L. Hendricks. 2001. Gamma interferon can prevent herpes simplex virus type 1 reactivation from latency in sensory neurons. J. Virol. 75:11178-11184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liu, T., Q. Tang, and R. L. Hendricks. 1996. Inflammatory infiltration of the trigeminal ganglion after herpes simplex virus type 1 corneal infection. J. Virol. 70:264-271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Maldonado-Lopez, R., T. De Smedt, P. Michel, J. Godfroid, B. Pajak, C. Heirman, K. Thielemans, O. Leo, J. Urbain, and M. Moser. 1999. CD8α+ and CD8α− subclasses of dendritic cells direct the development of distinct T helper cells in vivo. J. Exp. Med. 189:587-592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Marrack, P., J. Bender, D. Hildeman, M. Jordan, T. Mitchell, M. Murakami, A. Sakamoto, B. C. Schaefer, B. Swanson, and J. Kappler. 2000. Homeostasis of αβ TCR+ T cells. Nat. Immunol. 1:107-111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Marrack, P., J. Kappler, and T. Mitchell. 1999. Type I interferons keep activated T cells alive. J. Exp. Med. 189:521-529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mittnacht, S., P. Straub, H. Kirchner, and H. Jacobsen. 1988. Interferon treatment inhibits onset of herpes simplex virus immediate-early transcription. Virology 164:201-210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Morrison, L. A., and D. M. Knipe. 1997. Contributions of antibody and T cell subsets to protection elicited by immunization with a replication-defective mutant of herpes simplex virus type 1. Virology 239:315-326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Moser, M., and K. M. Murphy. 2000. Dendritic cell regulation of TH1-TH2 development. Nat. Immunol. 1:199-205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mossman, K. L., H. A. Saffran, and J. R. Smiley. 2000. Herpes simplex virus ICP0 mutants are hypesensitive to interferon. J. Virol. 74:2052-2056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nagashunmugam, T., J. Lubinski, L. Wang, L. T. Goldstein, B. S. Weeks, P. Sundaresan, E. H. Kang, G. Dubin, and H. M. Friedman. 1998. In vivo immune evasion mediated by the herpes simplex virus type 1 immunoglobulin G Fc receptor. J. Virol. 72:5351-5359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nahmias, A. J., F. K. Lee, and S. Bechman-Nahmias. 1990. Sero-epidemiological and sociological patterns of herpes simplex virus infection in the world. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 69:19-36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Niemialtowski, M. G., and B. T. Rouse. 1992. Phenotypic and functional studies on ocular T cells during herpetic infections of the eye. J. Immunol. 148:1864-1870. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Noisakran, S., I. L. Campbell, and D. J. J. Carr. 1999. Ectopic expression of DNA encoding IFN-α1 in the cornea protects mice from herpes simplex virus type 1-induced encephalitis. J. Immunol. 162:4184-4190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Noisakran, S., and D. J. J. Carr. 2000. Plasmid DNA encoding IFN-α1 antagonizes herpes simplex virus type 1 ocular infection through CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes. J. Immunol. 164:6435-6443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Noisakran, S., and D. J. J. Carr. 2001. Topical application of the cornea post infection with plasmid DNA encoding interferon-α1 but not recombinant interferon-αA reduces herpes simplex virus type 1-induced mortality in mice. J. Neuroimmunol. 121:49-58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Parra, B., D. R. Hinton, N. W. Marten, C. C. Bergmann, M. T. Lin, C. S. Yang, and S. A. Stohlman. 1999. IFN-γ is required for viral clearance from central nervous system oligodendroglia. J. Immunol. 162:1641-1647. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pereira, R. A., and A. Simmons. 1999. Cell surface expression of H2 antigens on primary sensory neurons in response to acute but not latent herpes simplex virus infection in vivo. J. Virol. 73:6484-6489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pereira, R. A., D. C. Tscharke, and A. Simmons. 1994. Upregulation of class I major histocompatibility complex gene expression in primary sensory neurons, satellite cells, and Schwann cells of mice in response to acute but not latent herpes simplex virus infection in vivo. J. Exp. Med. 180:841-850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sciammas, R., P. Kodukula, Q. Tang, R. L. Hendricks, and J. A. Bluestone. 1997. T cell receptor-γδ cells protects mice from herpes simplex virus type 1-induced lethal encephalitis. J. Exp. Med. 185:1969-1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Selin, L. K., P. A. Santolucito, A. K. Pinto, E. Szomalanyi-Tsuda, and R. M. Welsh. 2001. Innate immunity to viruses: control of vaccinia virus infection by γδ T cells. J. Immunol. 166:6784-6794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Shimeld, C., J. L. Whiteland, S. M. Nicholls, E. Grinfeld, D. L. Easty, H. Gao, and T. J. Hill. 1995. Immune cell infiltration and persistence in the mouse trigeminal ganglion after infection of the cornea with herpes simplex virus type 1. J. Neuroimmunol. 61:7-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Shimeld, C., J. L. Whiteland, N. A. Williams, D. L. Easty, and T. J. Hill. 1997. Cytokine production in the nervous system of mice during acute and latent infection with herpes simplex virus type 1. J. Gen. Virol. 78:3317-3325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Simmons, A., and D. C. Tscharke. 1992. Anti-CD8 impairs clearance of herpes simplex virus from the nervous system: implications for the fate of virally infected neurons. J. Exp. Med. 175:1337-1344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Song, G.-Y., G. DeJong, and W. Jia. 1999. Cell surface expression of MHC molecules in glioma cells infected with herpes simplex virus type-1. J. Neuroimmunol. 93:1-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Stark, G. R., I. M. Kerr, B. R. G. Williams, R. H. Silverman, and R. D. Schreiber. 1998. How cells respond to interferons. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 67:227-264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Su, Y.-H., J. E. Oakes, and R. N. Lausch. 1990. Ocular avirulence of a herpes simplex virus type 1 strain is associated with heightened sensitivity to alpha/beta interferon. J. Virol. 64:2187-2192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Tamesis, R. R., E. M. Messmer, B. A. Rice, J. E. Dutt, and C. S. Foster. 1994. The role of natural killer cells in the development of herpes simplex virus type 1 induced stromal keratitis in mice. Eye 8:298-306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tang, Q., and R. L. Hendricks. 1996. Interferon γ regulates platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule 1 expression and neutrophil infiltration into herpes simplex virus-infected mouse corneas. J. Exp. Med. 184:1435-1447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Thomas, J., S. Gangappa, S. Kanangat, and B. T. Rouse. 1997. On the essential involvement of neutrophils in the immunopathologic disease: herpetic stromal keratitis. J. Immunol. 158:1383-1391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Thomas, J., and B. T. Rouse. 1998. Immunopathology of herpetic stromal keratitis: discordance in CD4+ T cell function between euthymic host and reconstituted SCID recipients. J. Immunol. 160:3965-3970. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Tortorella, D., B. E. Gewurz, M. H. Furman, D. J. Schust, and H. L. Ploegh. 2000. Viral subversion of the immune system. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 18:861-926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Tough, D. F., P. Borrow, and J. Sprent. 1996. Induction of bystander T cell proliferation by viruses and type I interferon in vivo. Science 272:1947-1950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Tscharke, D. C., and A. Simmons. 1999. Anti-CD8 treatment alters interleukin-4 but not interferon-γ mRNA levels in murine sensory ganglia during herpes simplex virus infection. Arch. Virol. 144:2229-2238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Tumpey, T. M., S.-H. Chen, J. E. Oakes, and R. N. Lausch. 1996. Neutrophil-mediated suppression of virus replication after herpes simplex virus type 1 infection in the murine cornea. J. Virol. 70:898-904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Tumpey, T. M., H. Cheng, D. N. Cook, O. Smithies, J. E. Oakes, and R. N. Lausch. 1998. Absence of macrophage inflammatory protein-1α prevents the development of blinding herpes stromal keratitis. J. Virol. 72:3705-3710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Vollstedt, S., M. Franchini, G. Alber, M. Ackermann, and M. Suter. 2001. Interleukin-12- and gamma interferon-dependent innate immunity are essential and sufficient for long-term survival of passively immunized mice infected with herpes simplex virus type 1. J. Virol. 75:9596-9600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Yokota, S.-I., N. Yokosawa, T. Kubota, T. Suzutani, I. Yoshida, S. Miura, K. Jimbow, and N. Fujii. 2001. Herpes simplex virus type 1 suppresses the interferon signaling pathway by inhibiting phosphorylation of STATs and janus kinases during an early infection stage. Virology 286:119-124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Zheng, X., R. H. Silverman, A. Zhou, T. Goto, B. S. Kwon, H. E. Kaufman, and J. M. Hill. 2001. Increased severity of HSV-1 keratitis and mortality in mice lacking the 2-5A-dependent RNase L gene. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 42:120-126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]