Abstract

Feline CXCR4 and CCR5 were expressed in feline cells as fusion proteins with enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP). Expression of the EGFP fusion proteins was localized to the cell membrane, and surface expression of CXCR4 was confirmed by using a cross-species-reactive anti-CXCR4 monoclonal antibody. Ectopic expression of feline CCR5 enhanced expression of either endogenous feline CXCR4 or exogenous feline or human CXCR4 expressed from a retrovirus vector, indicating that experiments investigating the effect of CCR5 expression on feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV) infection must be interpreted with caution. Susceptibility to infection with cell culture-adapted strains of FIV or to syncytium formation following transfection with a eukaryotic vector expressing an env gene from a cell culture-adapted strain of virus correlated with expression of either human or feline CXCR4, whereas feline CCR5 had no effect. In contrast, neither CXCR4 nor CCR5 rendered cells permissive to either productive infection with primary strains of FIV or syncytium formation following transfection with primary env gene expression vectors. Screening a panel of Ghost cell lines expressing diverse human chemokine receptors confirmed that CXCR4 alone supported fusion mediated by the FIV Env from cell culture-adapted viruses. CXCR4 expression was upregulated in Ghost cells coexpressing CXCR4 and CCR5 or CXCR4, CCR5, and CCR3, and susceptibility to FIV infection could be correlated with the level of CXCR4 expression. The data suggest that β-chemokine receptors may influence FIV infection by modulating the expression of CXCR4.

Infection of the domestic cat with feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV) induces an illness similar to AIDS in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected human beings (39, 48). Although infection with FIV is accompanied by a gradual decline in the number of CD4+ lymphocytes (2), the feline homologue of CD4 does not appear to act as a primary binding receptor for infection with the virus, and ectopic expression of feline CD4 on feline cells does not confer susceptibility to infection with FIV (36). Furthermore, the expression of CD4 in the domestic cat is restricted to helper T cells and their thymic precursors, and unlike human CD4, feline CD4 is not expressed on cells of the monocyte/macrophage lineage (1).

Previous studies have demonstrated that feline monocyte/macrophage lineage cells and a range of other CD4-negative cells (CD8+ lymphocytes, B lymphocytes, astrocytes, and Schwann cells) are susceptible to infection with FIV (6, 14). If the primate lentiviruses evolved the use of CD4 as a high-affinity binding receptor in order to target the viruses more efficiently to T helper lymphocytes and monocyte/macrophages, it is possible that FIV represents a more primitive ancestor of HIV, encoding fewer regulatory genes (the FIV genome lacks the nef, vpu, and vpr open reading frames) and lacking the specific targeting of CD4+ cells. As such, by studying FIV, it may be possible to identify the viral determinants that render the feline and primate lentiviruses capable of causing immunodeficiency rather than inducing chronic inflammatory conditions, as typified by caprine arthritis encephalitis virus and Maedi-Visna virus.

With the discovery of the role of seven transmembrane domain superfamily (7TM) molecules in infection with the primate lentiviruses, a possible link between the feline and primate lentiviruses was uncovered. Subsequently, it was revealed that FIV uses the chemokine receptor CXCR4 as a receptor for infection (53); ectopic expression of CXCR4 confers susceptibility to infection with FIV (50, 55), and the FIV envelope glycoprotein binds CXCR4 with high affinity (19). Furthermore, FIV infection is inhibited by the natural ligands for CXCR4 (SDF-1/CXCL12) (19) and CXCR4 antagonists such as met-SDF, AMD3100, and ALX-404C (16, 43, 51). Given the importance of the virus-receptor interaction in determining the cell tropism of a virus, the shared usage of CXCR4 as a cellular receptor by HIV and FIV represents a potential means by which the viruses may induce similar pathologies.

The principal chemokine receptors utilized by HIV as coreceptors for infection are CXCR4 and CCR5 (a receptor for the β-chemokines RANTES, MIP-1α, and MIP-1β) (3, 12, 15, 18). While a diverse range of other 7TM molecules have been shown to act as coreceptors for the primate lentiviruses (reviewed in reference 8), the role of these additional molecules in the pathogenesis of AIDS remains unclear. While CCR5 appears to be the coreceptor utilized by the majority of HIV strains early in infection, usage of CXCR4 as a coreceptor is more frequent with disease progression (45). The shift in coreceptor usage from CCR5 to CXCR4 (formerly identified as non-syncytium-inducing and syncytium-inducing, respectively) with disease progression raises the question of whether usage of CXCR4 as a viral receptor arises a result of disease progression or whether it hastens disease progression.

Previous studies have demonstrated that during the early phase of infection with FIV, the major reservoir of infected cells in peripheral blood is CD4+ lymphocytes. In contrast, in chronic infection, both CD8+ lymphocytes and B lymphocytes are infected, suggesting a shift in viral tropism with prolonged infection (10, 11, 17). These data provide compelling evidence for the existence of viruses with distinct cell tropisms in infected cats, analogous to CCR5- and CXCR4-dependent viruses in HIV-infected individuals. Conflicting data have been presented regarding the usage of CCR5 as a coreceptor by FIV. Early studies demonstrated that ectopic expression of CCR5 did not confer susceptibility to infection with cell culture-adapted strains of FIV (50), while studies on the inhibition of FIV infection with β-chemokines have provided little data to support a role for CCR5 in FIV infection, since RANTES, MIP-1α, and MIP-1β failed to inhibit FIVGL8 infection of Mya-1 cells (19) and displayed only a 20 to 40% reduction in FIVPPR infection of T cells (24).

In contrast, a separate study showed that anti-human CCR3 and CCR5 could inhibit infection of human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) with FIV, suggesting that FIV could utilize not only CCR5 but also human CCR3 and CCR5 as coreceptors for infection (22). Moreover, recent studies have suggested that the V1-CSF isolate of FIV requires coexpression of human CCR5 and CCR3 for infection of cells expressing human CXCR4 and have proposed that human CCR3 and CCR5 act as coreceptors for FIV infection (23).

The aim of this study was to define further the role of CXCR4 and CCR5 in FIV infection. We demonstrate that ectopic expression of CCR5 enhances cell surface expression of CXCR4 and, in doing so, may enhance the susceptibility of CCR5-expressing cells to infection with CXCR4-dependent strains of FIV.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmids and cDNA cloning.

Feline CXCR4 (U63558) has been described previously. Feline CCR5 cDNA (U92796) was obtained from J. Elder (Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, Calif.). pCI-VSV-G was obtained from G. Nolan, Stanford University. pHIT60 was obtained from A. Kingsman, Oxford Biomedica, Oxford, United Kingdom. cDNAs were subcloned into the EGFPN1 vector (Clontech Laboratories Inc., Palo Alto, Calif.) as EcoRI/BamHI fragments, creating an N-terminal fusion with enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP). Subcloning of the cDNAs was performed with the Hi-Fidelity PCR system (Roche Diagnostics Ltd., Lewes, United Kingdom) and a GeneAmp PCR system 9700 thermal cycler (PE Applied Biosystems, Warrington, United Kingdom), with oligonucleotide primers carrying the appropriate restriction sites.

Amplification of CXCR4 used primers 5′-GCGAATTCACCATGGACGGGTTTCGTATATAC-3′ and 5′-CGGTGGATCCGAGGAGTGAAAACTTGAAGA-3′, while CCR5 was amplified with primers 5′-GCGAATTCACCATGGATTATCAAGCCACGAG-3′ and 5′-CGGTGGATCCAAGCCGACAGAGATTTCCTG-3′. The CXCR4 and CCR5/EGFP fusion products were then subcloned as SalI/HpaI fragments into the pDONAI retrovirus vector (Takara Shuzo Co. Ltd., Shiga, Japan) by reamplification with the primers 5′-GCGTCGACGCTAGCGCTACCGGACTCAGATCT-3′ and 5′-TTGTTAACGCGGCCGCTTTACTTGTACAGCTC-3′.

FIV env genes were amplified from the GL8414 (21), PPR (40), PETF14 (37), and GL8EK (21) molecular clones by PCR as above with oligonucleotide primers 5′-GGGTCGACACCATGGCAGAAGGGTTTGCAGCA-3′ and 5′-GGGCGGCCGCCATCATTCCTCCTCTTTTTCAGAC-3′, incorporating SalI and NotI restriction sites, and cloned into the eukaryotic expression vector VR1012 (Vical Incorporated, San Diego, Calif.). The nucleic acid sequences of all cDNAs subcloned by Hi-Fidelity PCR were determined with the Big Dye terminator cycle sequencing kit, version 2 (ABI Prism; Applied Biosystems) and an Applied Biosystems 3700 capillary sequencer.

Viruses and cell lines.

All cell culture media and supplements were obtained from Invitrogen Life Technologies Ltd. (Paisley, United Kingdom). Adherent cell lines were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 2 mM glutamine, 0.11 mg of sodium pyruvate per ml, 100 IU of penicillin per ml, and 100 μg of streptomycin per ml.

Ghost(3) cell lines (34) were obtained from the Medical Research Council AIDS-directed program. AH927 and Ghost cells expressing feline CXCR4 and CCR5 or human CXCR4 were generated by transduction with the retrovirus vector pDONAI (Takara Shuzo Co. Ltd.) or pBabePuro (33) bearing the appropriate cDNA. Murine leukemia virus pseudotypes carrying the pDONAI or pBabePuro retrovirus vector were prepared by transfection of HEK 293T cells with the retrovirus vector in conjunction with pHIT60 (47) (encoding the murine leukemia virus gag-pol) and pCI-VSV-G (encoding the vesicular stomatitis virus G protein) at a 1:1:1 ratio with Superfect transfection reagent (Qiagen Ltd., Crawley, United Kingdom).

Supernatants were collect 48 h posttransfection, filtered at 0.45 μm, and used to transduce the target cell lines at an approximate multiplicity of infection of 1.0 (assessed by transducing a parallel culture with pseudotypes bearing a retrovirus vector encoding a lacZ reporter gene). At two days posttransduction, the target cells were subcultured and reseeded in culture medium supplemented with 800 μg of G418 (geneticin; Life Technologies) or 2.5 μg of puromycin (Sigma) per ml. Cells were maintained in the selective antibiotic until stably transduced populations outgrew the cultures. Ghost-FX4 and -FR5 were generated by transduction of Ghost cells with feline CXCR4 or CCR5, respectively, in the retrovirus vector pBabePuro (33).

The interleukin-2 (IL-2)-dependent feline T-cell lines Mya-1 (32) and Q201 (52) and PBMC were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 2 mM glutamine, 100 IU of penicillin per ml,100 μg of streptomycin per ml, 5 × 10−5 M 2-mercaptoethanol, and 100 IU of recombinant human IL-2 per ml (RPMI). Virus stocks were prepared from molecular clones of FIV: GL8414 (21), PPR (40), PETF14 (37), TM2 (31), and GL8EK (21). FIV-B-2542 was obtained from S. Vandewoude, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, Colo. Molecular clones were transfected into the human epithelioid cell line HEK 293T with Superfect transfection reagent (Qiagen Ltd.). At 48 h posttransfection, supernatants were harvested, filtered (0.45-μm filters), and used to infect the IL-2-dependent feline T-cell line Mya-1 (32). The infected cultures were monitored visually for cytopathicity and for the production of FIV p24 by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA; PetCheck FIV antigen ELISA; Idexx Corp., Portland, Maine). Supernatants were collected at peak cytopathicity or p24 production, filtered (0.45-μm filters), dispensed as 1-ml aliquots, and stored at −70°C.

The growth of FIV strains in vitro was assessed by infection of the target cell line with virus stocks prepared in IL-2-dependent T cells (Mya-1 cells). Cells were incubated with a matched tissue culture infective dose of virus for 1 h at 37°C, washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline, fed with fresh culture medium, and maintained in culture for 7 to 10 days. Supernatants were collected every 3 days and assayed for the production of p24 (PetCheck FIV antigen ELISA; Idexx Corp.) or reverse transcriptase with the Lenti-RT nonisotopic reverse transcriptase assay kit (Cavidi Tech, Uppsala, Sweden).

Antibodies and flow cytometry.

Antibodies were used either unconjugated or conjugated to either phycoerythrin (PE) or fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC). Anti-CXCR4 (human-specific) antibody 12G5 was obtained from James Hoxie, University of Pennsylvania. Anti-CXCR4 (human/feline cross-reactive) 44717 and 44708 (human CXCR4-specific) and anti-human CCR5 45519 were obtained from Monica Tsang (R&D systems, Minneapolis, Minn.). Unconjugated primary antibodies (immunoglobulin G [IgG] isotype) were detected with FITC- or PE-coupled F(ab′)2 fragment of sheep anti-mouse IgG whole molecule (Sigma, Poole, United Kingdom). Samples were analyzed on Beckman Coulter Epics Elite and Epics XL flow cytometers, and 10,000 events were collected for each sample. Data were analyzed with Expo32 ADC software (Applied Cytometry Systems, Sheffield, United Kingdom). In the analysis of Ghost cells expressing CXCR4 or CCR5, percentages were calculated relative to the Ghost cell parent cell lines by overlaying histograms and applying Overton analysis (38) with the Expo32 ADC software package.

In vitro expression of env genes.

The expression of functional Env proteins from the VR1012 expression constructs was confirmed by immunofluorescence with anti-FIV Env monoclonal antibody (vpg71.2). Immunofluorescence was performed on transfected HEK 293T cells at 72 h posttransfection following fixation with ice-cold methanol. Fixed cells were rehydrated with phosphate-buffered saline containing 1.0% bovine serum albumin and 0.1% azide (PBA). The cells were then incubated with 1 μg of either vpg71.2 or an isotype-matched control for 30 min on ice, washed twice with PBA by centrifugation, and then incubated with FITC-coupled F(ab′)2 fragment of sheep anti-mouse IgG whole molecule (Sigma Ltd.) on ice for a further 30 min. Finally, the cells were washed twice with PBA and then examined on a Leica UV microscope or by flow cytometry on an Epics Elite flow cytometers (10,000 events collected in list mode).

To assess the fusogenicity of the FIV Env proteins, AH927 or Ghost cells were transfected with the VR1012-Env constructs with Superfect (Qiagen) and incubated for 48 h at 37°C. The cells were then fixed and stained with 1% methylene blue-0.2% basic fuchsin in methanol. Syncytia were enumerated by light microscopy with a 12.5× Leitz periplan eyepiece with a 6.5 by 9 graticule, three separate fields being counted per well, each well in duplicate. Cells with five or more nuclei were scored as syncytia.

Detection of virus entry with PCR.

Ghost or AH927 cells were seeded in six-well culture plates at 1.5 × 105 cells per well and incubated overnight at 37°C. Cells were infected with PETF14 or GL8414 for 1 h at 37°C, rinsed twice with phosphate-buffered saline and then fed with fresh culture medium. Following overnight incubation at 37°C, the cells were removed from the culture plates with trypsin-EDTA and pelleted, and DNA was prepared with a QIAamp DNA blood kit (Qiagen). Then 0.5 mg of DNA was used in semiquantitative PCRs in which either an 871-bp FIV gag gene product was amplified with the primers 5′-GGG ATT AGA CAC TAG GCC ATC TA-3′ and 5′-GAC CAG GTT TTC CAC ATT TAT TA-3′ or a control cellular DNA for β-actin was amplified with the primers 5′-ATC TGG CAC CAC ACC TTC TAC AAT GAG CTG CG-3′ and 5′-CGT CAT ACT CCT GCT TGC TGA TCC ACA TCT GC-3′. Reaction mixes were denatured at 94°C for 3 min, followed by 30 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 30 s, annealing at 50°C for 1 min, and extension at 72°C for 1 min, with a final extension of 10 min at 72°C. All reactions were performed with Hi-Fidelity PCR mix (Roche) per the manufacturer's instructions on a GeneAmp PCR system 9700 (Perkin Elmer).

RESULTS

Ectopic expression of feline CXCR4 and CCR5.

In order to examine further the role of CXCR4 and CCR5 in FIV infection, we developed cell lines that would stably express either molecule as a C-terminal fusion protein with EGFP, enabling the expression of CXCR4 and CCR5 to be evaluated by flow cytometry and UV microscopy. The feline CXCR4-EGFP and CCR5-EGFP genes were subcloned into the pDONAI retrovirus vector, packaged into murine leukemia virus particles bearing the vesicular stomatitis virus G protein, and used to transduce the feline cell lines AH927, CrFK, and 3201 and the murine cell line 3T3. EGFP alone was included as the control.

Figure 1 illustrates the results of flow cytometric analyses on the transduced AH927 cells. EGFP expression was detected on each of the transduced cell lines, the highest mean fluorescence intensity being observed in the cells transduced with the retrovirus vector bearing EGFP alone (mean fluorescence = 101.7, 99.2% positive). In contrast, while the majority of the cells transduced with CXCR4-EGFP or CCR5-EGFP expressed EGFP (97.3 or 91.1%, respectively), the mean fluorescence intensity was significantly lower (CXCR4-EGFP mean fluorescence = 6.1, and CCR5-EGFP mean fluorescence = 3.7). UV microscopy revealed that while the fluorescence in the EGFP control was diffuse and cytoplasmic (Fig. 1D), fluorescence in the cells transduced with CXCR4-EGFP or CCR5-EGFP was largely perinuclear and membrane associated (Fig. 1E and 1F), consistent with the predicted localization of the EGFP-tagged chemokine receptors. Similar results were obtained with the 3T3, CrFK, and 3201 cell lines (not shown).

FIG. 1.

Expression of feline CXCR4 and CCR5 as EGFP fusion proteins. AH927 cells were transduced with retrovirus vectors carrying feline CXCR4-EGFP (B and E), CCR5-EGFP (C and F), or EGFP (A and D) alone and selected in G418 (800 μg/ml). EGFP expression was quantified by flow cytometry and subcellular localization was analyzed by UV microscopy. Histograms represent plots of fluorescence intensity (x axis) versus relative cell number (y axis).

We next examined the expression of CXCR4 at the cell surface of the transduced AH927 cells with anti-CXCR4 monoclonal antibody. Previously we identified anti-human CXCR4 monoclonal antibodies that cross-reacted with feline CXCR4 (4, 19). Using two-color flow cytometry, we observed that a minority of the AH927 cells (4.6%) expressed CXCR4. A similar level of CXCR4 expression was detected on the cells transduced with EGFP alone (E, 4.8%; Fig. 2B). In contrast, 51.6% of the CXCR4-EGFP cells (FX4E) were CXCR4 positive (Fig. 2D), confirming that the CXCR4-EGFP fusion protein was expressed at the cell surface. Of the CXCR4-EGFP cells, 30.4% were EGFP positive but surface CXCR4 negative, suggesting that this represented intracellular CXCR4-EGFP. Finally, we examined surface CXCR4 expression on the CCR5-EGFP-transduced cells (FR5E). Surprisingly, transduction with the CCR5-EGFP-expressing vector increased surface expression of CXCR4 to 10.4%. Given that only 4.8% of the cells transduced with EGFP expressed surface CXCR4, these data suggested that ectopic expression of CCR5 may upregulate endogenous CXCR4 expression on AH927 cells.

FIG. 2.

Estimation of surface CXCR4 expression in transduced cells by flow cytometry. AH927 cells were transduced with vectors carrying feline CXCR4-EGFP, feline CCR5-EGFP, or EGFP alone. Two-color dot plots of EGFP expression (x axis) versus CXCR4 expression (y axis) compared with isotype-matched controls (A, C, and E) are shown. Each dot plot represents 10,000 events.

The CCR5-EGFP cells were used to screen a range of anti-human CCR5 monoclonal antibodies (2D7 [Leukosite Inc.] and 45511, 45517, 45519, 45523, 45529, 45531, and 45533 [R&D Systems]), but no cross-reactivity was detected (data not shown).

Upregulation of CXCR4 following ectopic expression of CCR5.

In order to investigate further the possible upregulation of CXCR4 following CCR5 expression, we examined the effects of transducing the AH927-derived cell lines expressing either EGFP (E-P) or the feline CXCR4- and feline CCR5-EGFP fusion proteins with a second series of retrovirus vectors expressing feline CXCR4 (FX4P), feline CCR5 (FR5P), or human CXCR4 (HX4P) from retrovirus vectors carrying a selectable marker for puromycin resistance. Parallel cultures were transduced with the vector carrying puromycin resistance alone (P) as a control. CXCR4 expression was measured by flow cytometry with either an antibody recognizing an epitope common to feline and human CXCR4 (44718) or a human CXCR4-specific antibody (12G5). Transduction with the puro vector and selection in puromycin alone did not alter expression of CXCR4; 4.7% of cells in the control group E-P were CXCR4 positive, representing basal endogenous CXCR4 expression (Fig. 3A). Transduction of the EGFP control cells with FX4P (Fig. 3B) and HX4P (Fig. 3D) elevated CXCR4 expression to 26.1% and 80.1%, respectively. Transduction with FR5P elevated CXCR4 (Fig. 3C) expression to 11.3%, confirming the previous observation with FR5E that ectopic CCR5 expression enhances endogenous CXCR4 expression.

FIG. 3.

Estimation of total surface CXCR4 expression in transduced AH927 cells by flow cytometry. AH927 cells stably transduced with pDONAI-based retrovirus vectors bearing EGFP (E), feline CXCR4-EGFP (FX4E), or feline CCR5-EGFP (FR5E) were transduced again with a second series of pBabePuro vectors bearing feline CXCR4 (FX4P), feline CCR5 (FR5P), human CXCR4 (HX4P), or vector only (P) and selected in puromycin. Two-color dot plots of EGFP expression (x axis) versus surface CXCR4 expression (y axis) are shown. Each dot plot represents 10,000 events.

We next examined CXCR4 expression on FR5E cells transduced with P (Fig. 3E), FX4P (Fig. 3F), FR5P (Fig. 3G), or HX4P (Fig. 3H). FR5E cells transduced with the puro vector alone continued to express enhanced levels of CXCR4 (28.7% of FR5E-P were CXCR4 positive, compared with 4.7% of E-P). That 28.7% of the FR5E-P cells were CXCR4 positive (Fig. 3E) compared with 10.4% of FR5E (Fig. 2F) may reflect the higher passage number of the FR5E-P cells following selection in puromycin-containing medium and underlines the importance of the E-P control (4.7% positive) transduced and maintained in parallel. Following transduction with FX4P, 70.5% of FR5E-FX4P cells were CXCR4 positive. Compared with E-FX4P (26.1%), the elevated expression of CXCR4 on FR5E-FX4P indicated that stable expression of feline CCR5 enhanced the expression of both endogenous and ectopically expressed CXCR4.

Transduction of FR5E with FR5P did not enhance CXCR4 expression further (FR5E-FR5P, 27.8% CXCR4 positive, compared with FR5E-P, 28.7%). Similarly, transduction with HX4P did not enhance CXCR4 expression further (FR5E-HX4P, 75.7%, compared with E-HX4P, 80.1%). These findings indicate that transduction with a feline CCR5-expressing vector will (i) increase surface expression of endogenous CXCR4 and (ii) enhance expression of ectopically expressed CXCR4 following subsequent transduction with a CXCR4-expressing vector. FX4E transduced with P (Fig. 3I), FX4P (Fig. 3J), FR5P (Fig. 3K), or HX4P (Fig. 3L) expressed similar levels of CXCR4 (86.4%, 87.2%, 88.3%, or 86.7%, respectively), suggesting that a maximal level of CXCR4 expression had been achieved and could not be increased further.

With the anti-human CXCR4-specific monoclonal antibody 12G5, we examined the expression of human and feline CXCR4 on HX4P-transduced AH927-E, FR5E, and FX4E cells (Fig. 4). While 49.5% of control AH927-E cells transduced with HX4P were revealed as CXCR4 positive following staining with the 12G5 antibody (Fig. 4b), 75.7% of FR5E (Fig. 4d) and 83.9% of FX4E (Fig. 4f) were positive for human CXCR4 following transduction. These findings confirm our previous findings showing enhanced human CXCR4 expression in cells expressing CCR5. Furthermore, as prior transduction with feline CXCR4 also enhanced expression of human CXCR4, the data demonstrate that the effect is not CCR5 specific and that ectopic expression of feline CXCR4 will augment human CXCR4 expression.

FIG. 4.

Enhanced expression of human CXCR4 in cells transduced previously with feline CXCR4-EGFP (FX4E) or CCR5-EGFP (FR5E), or EGFP alone (E). E, FX4E, or FR5E cells were transduced with feline CXCR4 (FX4P) or human CXCR4 (HX4P) in the vector pBabePuro. Human CXCR4-specific monoclonal antibody 12G5 was used to differentiate human and feline CXCR4. Two-color dot plots of EGFP expression (x axis) versus surface CXCR4 expression (y axis) are shown. Each dot plot represents 10,000 events.

Effects of CXCR4 and CCR5 expression on FIV infection.

CXCR4 has been widely implicated in infection with FIV (13, 16, 41, 43, 50, 53, 55). In contrast, a single study suggested a role for human CCR5 and CCR3 in infection with FIV (22). Having generated cell lines that stably express feline CXCR4 and CCR5, we next asked whether these cells would be rendered permissive for either Env-mediated syncytium formation or cell-free virus infection with the GL8414 and PETF14 clones (representing primary and CrFK-adapted strains of virus, respectively).

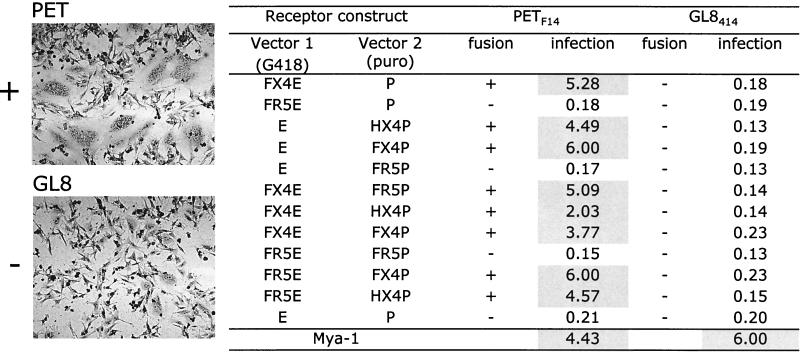

Each of the AH927 cell lines expressing feline CXCR4, feline CCR5, or human CXCR4 were either transfected with the eukaryotic expression vector VR1012 expressing the GL8414 or PETF14 env gene or infected with cell-free virus supernatant containing either the GL8414 or PETF14 virus (Fig. 5). Previous studies have demonstrated that infection of AH927 cells by FIV is blocked at the level of virus entry and that productive infection will occur following successful virus entry (21). Syncytium formation was monitored by light microscopy and scored as positive or negative, while productive infection was monitored by a nonisotopic reverse transcriptase assay (expressed as A405).

FIG. 5.

Susceptibility of AH927 cells transduced with CXCR4 or CCR5 to cell-free virus infection with cell culture-adapted (PETF14) and primary (GL8414) strains of FIV and to syncytium formation following transfection with expression vectors carrying the PETF14 or GL8414 env gene. Productive infection was measured by the nonisotopic reverse transcriptase assay (values represent absorbance measured at 405 nm; shading denotes a value above threshold). Syncytium formation was scored as positive or negative. Feline T-cell line Mya-1 was included as a control for infection with GL8414.

There was a good correlation between syncytium formation in PETF14 Env-transfected cells, PETF14 infection, and ectopic expression of either feline or human CXCR4. In contrast, CXCR4 expression alone did not render AH927 cells permissive for either GL8414 Env-mediated fusion or infection with GL8414 virus (similar findings were obtained with the primary PPR strain of FIV; data not shown). Feline CCR5 expression alone was insufficient to render cells permissive to infection with PETF14 or GL8414. Moreover, coexpression of feline CCR5 with either feline CXCR4 or human CXCR4 did not render the cells permissive for infection with GL8414. Ectopic expression of CXCR4 or CCR5 did not render the AH927 cells permissive for infection with the primary strain clade B viruses TM2 and B2542 (data not shown). Thus, feline CCR5 expression, either alone or coexpressed with feline CXCR4 or human CXCR4, was insufficient to render cells permissive for fusion or productive infection with four primary strains of FIV.

Feline and human CCR5s do not support fusion mediated by envelope glycoproteins from primary or cell culture-adapted strains of FIV.

Given that a previous study had suggested a role for human CCR5 or CCR3 in FIV infection (22), we examined the effect of transfecting chemokine receptor-expressing cells with expression vectors bearing envelope glycoproteins from primary or cell culture-adapted strains of FIV. Following expression of the PETF14 or GL8EK (a version of GL8 bearing an E407K mutation in the V3 loop [21]) envelopes in Ghost cells expressing either feline CXCR4 or CCR5 or human CXCR4, CCR1, CCR2, CCR3, CCR4, CCR5, CCR8, Bonzo, BOB, EB-1, or V28, syncytia were observed in the cells expressing feline or human CXCR4 but in no other cell line (Fig. 6). Similarly, the primary envelopes GL8414 and PPR did not induce syncytium formation in any of the cell lines tested.

FIG. 6.

Syncytium formation in Ghost cells expressing feline or human chemokine receptors. Expression vectors carrying primary (GL8414 or PPR) or cell culture-adapted (PETF14 or GL8EK) env genes were transfected into Ghost cells expressing a range of feline or human chemokine receptors. Syncytium formation was assessed by light microscopy at 48 h posttransfection. Typical results for PETF14 are shown, scored as positive or negative (left panel). A summary of the results for all four env genes is shown on the right.

The cells coexpressing human CXCR4 and CCR5 (X4R5) or human CXCR4, CCR5, and CCR3 (X4R5R3) appeared to display enhanced syncytium formation following transfection with the PETF14 or GL8EK Env (Fig. 6), but they did not support syncytium formation following transfection with the GL8414 or PPR Env. Furthermore, the panel of Ghost cell lines remained refractory to infection with HIV pseudotypes bearing the GL8414 or PPR envelope and carrying a luciferase reporter gene (9) (data not shown). Given that ectopic expression of feline CCR5 enhances cell surface expression of CXCR4, we postulated that the enhanced syncytium formation mediated by the PETF14 and GL8EK Envs in the X4R5 and X4R5R3 cell lines may reflect enhanced CXCR4 expression in these cell lines. We therefore analyzed CXCR4 and CCR5 expression on the Ghost cell lines by flow cytometry (Fig. 7).

FIG. 7.

Flow cytometric analysis of CCR5 and CXCR4 expression on Ghost cell lines. Ghost cell lines X4, R5, X4R5, and X4R5R3 were stained with either anti-human CCR5 (R&D systems 45519) (A) or anti-human CXCR4 (R&D systems 44708) (B and C). Bound antibody was detected with PE-conjugated anti-mouse IgG. A total of 10,000 events were collected for each sample. Histograms represent plots of fluorescence intensity (x axis) versus relative cell number (y axis).

Ghost R5 (Fig. 7A) cells expressed low levels of CCR5 (6.97%). CCR5 expression was increased in Ghost X4R5 (28.27%) and more markedly in X4R5R3 (66.53%). Thus, coexpression of CXCR4 or CXCR4 and CCR3 in Ghost R5 cells significantly enhanced CCR5 expression. Similar findings were observed for the expression of CXCR4 (Fig. 7B), with X4R5R3 cells expressing more CXCR4 (86.02%) than cells coexpressing CXCR4 and CCR5 (77.54%) or CXCR4 alone (73.26%). Finally, we compared the expression of CXCR4 on Ghost cells transduced with a puromycin resistance vector alone (control) or CCR5 (R5) or selected for high levels of CCR5 expression (Hi5). As shown in Fig. 7C, the Hi5 cells expressed more CXCR4 (33.9%) than the R5 cells (21.3%) or the control cells (19.1%), confirming that by selecting for human CCR5 expression, CXCR4 expression is also increased.

The data suggest an alternative explanation for the enhanced syncytium formation in the cells coexpressing more than one chemokine receptor, this being upregulation of surface CXCR4 expression. We next asked whether the enhanced syncytium formation in the X4R5 and X4R5R3 cells correlated with enhanced susceptibility to infection with PETF14 or GL8414 (Fig. 8). Given that there is a postentry block to the replication of FIV in Ghost cells, virus entry into the Ghost cell lines was assessed by PCR for FIV gag DNA at 24 h postinfection. Infection of Ghost cells was enhanced significantly by coexpression of CXCR4 with CCR5 (X4R5) or CCR5 and CCR3 (X4R5R3) (Fig. 8A). Furthermore, expression of CCR5 alone enhanced infection with PETF14 relative to the control cells (transduced with puro vector alone). Similar findings were observed with GL8414 although, as expected, infection was extremely inefficient compared to that with PETF14. Expression of X4, X4R5, X4R53, or R5 alone increased virus entry relative to the controls.

FIG. 8.

Detection of virus entry into chemokine receptor-expressing cell lines. Ghost X4, R5, X4R5, or X4R5R3 or vector-only control cells (A) and AH927 FX4E, FR5E, or E cells (B) were infected with PETF14 or GL8414 for 24 h, and PCR was then used to detect viral (gag) and cellular (β-actin) DNAs. Products were visualized by agarose gel electrophoresis and ethidium bromide staining.

We compared (in parallel) the susceptibility of the AH927-derived cell lines FX4E, FR5E, and E described above to infection with PETF14 and GL8414. While a strong product was amplified from FX4E infected with PETF14, extremely faint products were present in FR5E and E cells infected with PETF14 or FX4E, FR5E, or E cells infected with GL8414. The finding that GL8414 enters the human cell line Ghost more efficiently than the feline cell line AH927 is consistent with the previous findings of Willett, et al., which demonstrated that human CXCR4 supports fusion mediated by the FIV Env protein more efficiently than feline CXCR4 (50). Accordingly, AH927 cells expressing human CXCR4 support FIV infection more efficiently than cells expressing feline CXCR4 (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we examined the effects of feline CXCR4 and CCR5 expression on FIV infection. In order to ensure that expression of the chemokine receptors could be monitored, they were expressed as C-terminal fusion proteins with the N terminus of EGFP. The CXCR4- and CCR5-EGFP fusion proteins were found to target the EGFP to the cell membrane and to be expressed at the cell surface (CXCR4). With cells stably transduced with CXCR4-EGFP (FX4E) or CCR5-EGFP (FR5E), we demonstrated that CXCR4 expression was essential for infection of AH927 cells with the cell culture-adapted strain of PETF14 but did not confer susceptibility to infection with the primary strain GL8414. In contrast, CCR5 expression had no effect on susceptibility to infection with any of the four strains of FIV tested. In subsequent experiments, we have found that ectopic expression of feline CCR5-EGFP on the feline lymphosarcoma cell line 3201 did not render the cells permissive for infection with primary strains of FIV (data not shown).

Previous studies have suggested that human CCR5 and CCR3 are involved in infection of human PBMC with FIV (22). These studies were based on the ability of monoclonal antibodies against human CCR5 and CCR3 to inhibit infection of human PBMC with FIV. In our studies, we found no evidence for a role for feline CCR5 in FIV infection; ectopic expression of CCR5 does not confer susceptibility to infection with primary strains of FIV, and infection with primary strains of FIV is not inhibited by β-chemokines (19) or viral chemokine homologues (v-MIP; data not shown). A number of studies have failed to show significant inhibition of FIV infection by β-chemokines (13, 19). RANTES may either enhance the binding of FIV SU to feline cells (13) or have partial inhibitory activity on FIV infection (24).

Given that feline CCR5 and human CCR5 have only 82.6% amino acid similarity (76.6% identity), this difference being borne out by the failure of numerous anti-human CCR5 antibodies to recognize feline CCR5, the data would not predict a direct role for human CCR5 in FIV infection. Indeed, infection with the majority of FIV isolates studied to date can be blocked by the CXCR4 antagonist AMD3100 (16, 43; unpublished observations). In this study, we have demonstrated that ectopic expression of feline or human CCR5 leads to upregulation of cell surface CXCR4 expression. Thus, it is possible that modulating CCR3 or CCR5 expression may affect the expression of a known receptor for FIV, namely, CXCR4.

The upregulation of CXCR4 expression following ectopic expression of CCR5 has implications for experiments in which chemokine receptor usage by lentiviruses is evaluated in vitro. For example, a virus that is capable of using CXCR4 efficiently may infect cells transfected or transduced with a CCR5-expressing construct if CXCR4 is upregulated to a sufficient degree. Accordingly, we found that Ghost cells expressing β-chemokine receptors expressed enhanced levels of CXCR4 and were more susceptible to fusion mediated by PETF14 or GL8EK Env and supported virus entry more efficiently following challenge with either the PETF14 or GL8414 strain of FIV. Our findings indicate that the ectopic expression of CCR3 and CCR5 may modulate CXCR4 expression, analogous to the modulation of feline CXCR4 expression by phorbol myristate acetate or stromal-derived factor 1 (SDF-1) (19). Overnight incubation with SDF-1 or phorbol myristate acetate resulted in upregulation of CXCR4 expression, enhancing susceptibility to FIV infection (19).

Previous studies have indicated that chemokine receptors may form homodimers and heterodimers and that dimerization of chemokine receptors is a critical step in the signaling process (27, 30, 44). Indeed, the formation of heterodimers between CXCR4 or CCR5 and CCR2V64I (a mutant of CCR2 associated with a delay in progression to AIDS [46]) has been proposed as a mechanism by which CCR2V64I prevents HIV-1 infection (28). Moreover, HIV-1 infection is blocked by dimerization of CCR5 (49), and the formation of heterodimers between CCR2 and CCR5 triggers distinct signaling pathways from either CCR2 or CCR5 expressed as homodimers (29, 44). Recently, CCR5 was found to exist in several active states, and oligomerization of CCR5 resulted in internalization of the receptor via a pathway distinct from that induced by the receptor's agonist (5), suggesting that the regulation of chemokine receptor expression is complex and dependent on many variables. Thus, the upregulation of endogenous feline CXCR4 or exogenous human CXCR4 following ectopic expression of feline CCR5 may affect the sensitivity of the target cells to infection with FIV or to the antagonistic effects of chemokines on FIV infection.

Previously, it was observed that human CCR3- or CCR5-expressing cells supported infection with the V1-CSF strain of FIV, and yet there was an absolute requirement for CXCR4 expression for infection to occur, and anti-CXCR4 antibody completely abolished infection (23). Furthermore, although ectopic expression of human CCR3 and CCR5 on feline cells (CrFK) enhanced infection with FIV strain V1-CSF, the parent cell line (CrFK) also supported infection at a lower level in the absence of human CCR3 or CCR5 (23). Either CrFK cells express a chemokine receptor in addition to CXCR4 that substitutes for human CCR3/CCR5, or V1-CSF cells are capable of using CXCR4 alone as a receptor inefficiently. That the V1-CSF strain infects Ghost cells expressing CCR3 and CCR5 but not CXCR4 alone and yet infection is blocked completely by anti-CXCR4 antibody is intriguing and may suggest the use of a CXCR4-containing receptor complex for infection, as has been suggested (23).

We have found that ectopic expression of human β-chemokine receptors in human and feline cells may increase the expression of endogenous CXCR4, increasing the susceptibility of the cells to infection with X4-dependent viruses. Infection of Ghost cells with FIVPET or FIVGL8 correlates with the expression of human CXCR4 within these cells and is consistent with the preference for human CXCR4 over feline CXCR4 as a cofactor for Env-mediated fusion by cell culture-adapted strains of FIV (50). The contribution of CXCR4 upregulation to infection with the V1-CSF strain will require further investigation; however, it is possible that the V1-CSF isolate reflects a novel strain of FIV with a broad preference for chemokine receptor usage, analogous to dual-tropic strains of HIV. Determination of the prevalence of such strains of virus in the cat population clearly merits further investigation and comparison with established, highly characterized strains of FIV.

The mechanism by which coexpression of one chemokine receptor upregulates the surface expression of another chemokine receptor remains to be established. Previous studies have demonstrated that 7TM molecules are capable of forming both homodimers and heterodimers on the cell surface. Furthermore, engagement of chemokine receptors by either natural or synthetic ligands can induce receptor downregulation. Chemokine receptors such as CCR5 distribute asymmetrically in polarized cells, associating with membrane microdomains (26), structures of importance in membrane trafficking and signal transduction. HIV infection is thought to proceed following an interaction with chemokine receptors clustered within these regions (25), and the colocalization of CD4 with CXCR4 and CCR5 within these regions is required for productive infection of PM1 T cells (42).

If CXCR4 and CCR5 or CCR3 exist as heterodimers or are localized to microdomains on the cell surface, it is conceivable that anti-CCR3 and -CCR5 antibodies may interfere with viral access to CXCR4 or disrupt the membrane microdomains essential for virus entry. Indeed, monoclonal antibodies recognizing molecules associated with lipid rafts inhibit syncytium formation mediated by human T-cell lymphotropic virus type 1 (35). Moreover, since CD9 (a TM4 superfamily molecule) is also associated with lipid rafts (7), the disruption of membrane microdomains by anti-CD9 antibodies may account for previous conflicting results in which anti-CD9 antibodies blocked infection with FIV and ectopic expression of feline CD9 enhanced susceptibility to FIV infection and yet ectopic expression of CD9 was insufficient to render nonsusceptible cells permissive for FIV infection (20, 54).

The results of this study demonstrate that while FIV infection of the domestic cat provides a unique opportunity to study an immunodeficiency-causing lentivirus in its natural host, resolution of the role of β-chemokine receptors in FIV infection will be of importance to our understanding of the evolution of virulence in lentiviruses. In this way the cat model will be valuable for the study of β-chemokine receptor antagonists as potential therapeutics for the treatment of AIDS.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the Wellcome Trust and NIH grant AI049765.

We are grateful to J. Elder for provision of the feline CCR5 cDNA clone and for helpful discussions. We also thank G. Graham, J. A. Hoxie, D. R. Littman, R. Sutton, and M. Tsang for provision of reagents and advice.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ackley, C. D., E. A. Hoover, and M. D. Cooper. 1990. Identification of CD4 homologue in the cat. Tissue Antigens 35:92-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ackley, C. D., J. K. Yamamoto, N. Levy, N. C. Pedersen, and M. D. Cooper. 1990. Immunologic abnormalities in pathogen-free cats experimentally infected with feline immunodeficiency virus. J. Virol. 64:5652-5655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alkhatib, G., C. Combadiere, C. C. Broder, Y. Feng, P. E. Kennedy, P. M. Murphy, and E. A. Berger. 1996. CC CKR5: a RANTES, MIP-1α, MIP-1β receptor as a fusion cofactor for macrophage-tropic HIV-1. Science 272:1955-1958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baribaud, F., T. G. Edwards, M. Sharron, A. Brelot, N. Heveker, K. Price, F. Mortari, M. Alizon, M. Tsang, and R. W. Doms. 2001. Antigenically distinct conformations of CXCR4. J. Virol. 75:8957-8967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blanpain, C., J. M. Vanderwinden, J. Cihak, V. Wittamer, E. Le Poul, H. Issafras, M. Stangassinger, G. Vassart, S. Marullo, D. Schlndorff, M. Parmentier, and M. Mack. 2002. Multiple active states and oligomerization of CCR5 revealed by functional properties of monoclonal antibodies. Mol. Biol. Cell 13:723-737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brunner, D., and N. C. Pedersen. 1989. Infection of peritoneal macrophages in vitro and in vivo with feline immunodeficiency virus. J. Virol. 63:5483-5488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Claas, C., C. S. Stipp, and M. E. Hemler. 2001. Evaluation of prototype transmembrane 4 superfamily protein complexes and their relation to lipid rafts. J. Biol. Chem. 276:7974-7984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clapham, P. R., and R. A. Weiss. 1997. Immunodeficiency viruses—spoilt for choice of coreceptors. Nature 388:230-231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Connor, R. I., B. K. Chen, S. Choe, and N. R. Landau. 1995. Vpr is required for efficient replication of human immunodeficiency virus type-1 in mononuclear phagocytes. Virology 206:935-944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dean, G. A., S. Himathongkham, and E. E. Sparger. 1999. Differential cell tropism of feline immunodeficiency virus molecular clones in vivo. J. Virol. 73:2596-2603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dean, G. A., G. H. Reubel, P. F. Moore, and N. C. Pedersen. 1996. Proviral burden and infection kinetics of feline immunodeficiency virus in lymphocyte subsets of blood and lymph node. J. Virol. 70:5165-5169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deng, H., R. Liu, W. Ellmeir, S. Choe, D. Unutmaz, M. Burkhart, P. Di Marzio, S. Marmon, R. E. Sutton, C. M. Hill, C. B. Davis, S. C. Peiper, T. J. Schall, D. R. Littman, and N. R. Landau. 1996. Identification of a major co-receptor for primary isolates of HIV-1. Nature 381:661-666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Parseval, A., and J. H. Elder. 2001. Binding of recombinant feline immunodeficiency virus surface glycoprotein to feline cells: role of CXCR4, cell surface heparans, and an unidentified non-CXCR4 receptor. J. Virol. 75:4528-4539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dow, S. W., M. L. Poss, and E. A. Hoover. 1990. Feline immunodeficiency virus: a neurotropic lentivirus. J. Acquired Immune Defic. Syndr. 3:658-668. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dragic, T., T. Litwin, G. P. Allaway, S. R. Martin, Y. Huang, K. A. Nagashima, C. Cayanan, P. J. Maddon, R. A. Koup, J. P. Moore, and W. A. Paxton. 1996. HIV-1 entry into CD4+ cells is mediated by the chemokine receptor CC-CKR5. Nature 381:667-673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Egberink, H. F., E. De Clerq, A. L. Van Vliet, J. Balzarini, G. J. Bridger, G. Henson, M. C. Horzinek, and D. Schols. 1999. Bicyclams, selective antagonists of the human chemokine receptor CXCR4, potently inhibit feline immunodeficiency virus replication. J. Virol. 73:6346-6352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.English, R. V., C. M. Johnson, D. H. Gebhard, and M. B. Tompkins. 1993. In vivo lymphocyte tropism of feline immunodeficiency virus. J. Virol. 67:5175-5186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Feng, Y., C. C. Broder, P. E. Kennedy, and E. A. Berger. 1996. HIV-1 entry co-factor: functional cDNA cloning of a seven-transmembrane, G protein-coupled receptor. Science 272:872-877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hosie, M. J., N. Broere, J. Hesselgesser, J. D. Turner, J. A. Hoxie, J. C. Neil, and B. J. Willett. 1998. Modulation of feline immunodeficiency virus infection by stromal cell-derived factor (SDF-1). J. Virol. 72:2097-2104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hosie, M. J., B. J. Willett, T. H. Dunsford, O. Jarrett, and J. C. Neil. 1993. A monoclonal antibody which blocks infection with feline immunodeficiency virus identifies a possible non-CD4 receptor. J. Virol. 67:1667-1671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hosie, M. J., B. J. Willett, D. Klein, T. H. Dunsford, C. Cannon, M. Shimojima, J. C. Neil, and O. Jarrett. 2002. Evolution of replication efficiency following infection with a molecularly cloned feline immunodeficiency virus of low virulence. J. Virol. 76:6062-6072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johnston, J., and C. Power. 1999. Productive infection of human peripheral blood mononuclear cells by feline immunodeficiency virus: implications for vector development. J. Virol. 73:2491-2498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnston, J. B., and C. Power. 2002. Feline immunodeficiency virus xenoinfection: the role of chemokine receptors and envelope diversity. J. Virol. 76:3626-3636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lerner, D. L., and J. H. Elder. 2000. Expanded host cell tropism and cytopathic properties of feline immunodeficiency virus strain PPR subsequent to passage through interleukin-2-independent T cells. J. Virol. 74:1854-1863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Manes, S., G. del Real, R. A. Lacalle, P. Lucas, C. Gomez-Mouton, S. Sanchez-Palomino, R. Delgado, J. Alcami, E. Mira, and A. Martinez. 2000. Membrane raft microdomains mediate lateral assemblies required for HIV-1 infection. EMBO Rep. 1:190-196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Manes, S., E. Mira, C. Gomez-Mouton, R. A. Lacalle, P. Keller, J. P. Labrador, and A. Martinez. 1999. Membrane raft microdomains mediate front-rear polarity in migrating cells. EMBO J. 18:6211-6220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mellado, M., J. M. Rodriguez-Frade, S. Manes, and A. Martinez. 2001. Chemokine signaling and functional responses: the role of receptor dimerization and TK pathway activation. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 19:397-421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mellado, M., J. M. Rodriguez-Frade, A. J. Vila-Coro, A. M. de Ana, and A. Martinez. 1999. Chemokine control of HIV-1 infection. Nature 400:723-724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mellado, M., J. M. Rodriguez-Frade, A. J. Vila-Coro, S. Fernandez, A. Martin de Ana, D. R. Jones, J. L. Toran, and A. Martinez. 2001. Chemokine receptor homo- or heterodimerization activates distinct signaling pathways. EMBO J. 20:2497-2507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mellado, M., A. J. Vila-Coro, C. Martinez, and J. M. Rodriguez-Frade. 2001. Receptor dimerization: a key step in chemokine signaling. Cell Mol. Biol. (Noisy-le-Grand) 47:575-582. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miyazawa, T., M. Fukasawa, A. Hasegawa, N. Maki, K. Ikuta, E. Takahashi, M. Hayami, and T. Mikima. 1991. Molecular cloning of a novel isolate of feline immunodeficiency virus biologically and genetically different from the original U.S. isolate. J. Virol. 65:1572-1577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miyazawa, T. M., T. Furuya, S. Itagaki, Y. Tohya, E. Takahashi, and T. Mikami. 1989. Establishment of a feline T-lymphoblastoid cell line highly sensitive for replication of feline immunodeficiency virus. Arch. Virol. 108:131-135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Morgenstern, J. P., and H. Land. 1990. Advanced mammalian gene transfer: high titre retrovirus vectors with multiple drug selection markers and a complementary helper-free packaging cell line. Nucleic Acids Res. 18:3587-3596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morner, A., A. Bjorndal, J. Albert, V. N. KewalRamani, D. R. Littman, R. Inoue, R. Thorstensson, E. M. Fenyo, and E. Bjorling. 1999. Primary human immunodeficiency virus type 2 (HIV-2) isolates, like HIV-1 isolates, frequently use CCR5 but show promiscuity in coreceptor usage. J. Virol. 73:2343-2349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Niyogi, K., and J. E. Hildreth. 2001. Characterization of new syncytium-inhibiting monoclonal antibodies implicates lipid rafts in human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 syncytium formation. J. Virol. 75:7351-7361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Norimine, J., T. Miyazawa, Y. Kawaguchi, K. Tomonaga, Y.-S. Shin, T. Toyosaki, M. Kohmoto, M. Niikura, Y. Tohya, and T. Mikami. 1993. Feline CD4 molecules expressed on feline nonlymphoid cell lines are not enough for productive infection of highly lymphotropic feline immunodeficiency virus isolates. Arch. Virol. 130:171-178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Olmsted, R. A., A. K. Barnes, J. K. Yamamoto, V. M. Hirsch, R. H. Purcell, and P. R. Johnson. 1989. Molecular cloning of feline immunodeficiency virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 86:2448-2452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Overton, W. R. 1988. Modified histogram subtraction technique for analysis of flow cytometry data. Cytometry 9:619-626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pedersen, N. C., E. W. Ho, M. L. Brown, and J. K. Yamamoto. 1987. Isolation of a T-lymphotropic virus from domestic cats with an immunodeficiency syndrome. Science 235:790-793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Phillips, T. R., R. L. Talbott, C. Lamont, S. Muir, K. Lovelace, and J. H. Elder. 1990. Comparison of two host cell range variants of feline immunodeficiency virus. J. Virol. 64:4605-4613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Poeschla, E. M., and D. J. Looney. 1998. CXCR4 requirement for a nonprimate lentivirus: heterologous expression of feline immunodeficiency virus in human, rodent, and feline cells. J. Virol. 72:6858-6866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Popik, W., T. M. Alce, and W. C. Au. 2002. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 uses lipid raft-colocalized CD4 and chemokine receptors for productive entry into CD4+ T cells. J. Virol. 76:4709-4722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Richardson, J., G. Pancino, T. Leste-Lasserre, J. Schneider-Mergener, M. Alizon, P. Sonigo, and N. Heveker. 1999. Shared usage of the chemokine receptor CXCR4 by primary and laboratory-adapted strains of feline immunodeficiency virus. J. Virol. 73:3661-3671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rodriguez-Frade, J. M., M. Mellado, and A. Martinez. 2001. Chemokine receptor dimerization: two are better than one. Trends Immunol. 22:612-617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Scarlatti, G., E. Tresoldi, A. Bjorndal, R. Fredriksson, C. Colognesi, H. K. Deng, M. S. Malnati, A. Plebani, A. G. Siccardi, D. R. Littman, E. M. Fenyo, and P. Lusso. 1997. In vivo evolution of HIV-1 co-receptor usage and sensitivity to chemokine-mediated suppression. Nat. Med. 3:1259-1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Smith, M. W., M. Dean, M. Carrington, C. Winkler, G. A. Huttley, D. A. Lomb, J. J. Goedert, T. R. O’Brien, L. P. Jacobson, R. Kaslow, S. Buchbinder, E. Vittinghoff, D. Vlahov, K. Hoots, M. W. Hilgartner, and S. J. O’Brien. 1997. Contrasting genetic influence of CCR2 and CCR5 variants on HIV-1 infection and disease progression. Science 277:959-965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Soneoka, Y., P. M. Cannon, E. E. Ramsdale, J. C. Griffiths, G. Romano, S. M. Kingsman, and A. J. Kingsman. 1995. A transient three-plasmid expression system for the production of high titer retrovirus vectors. Nucleic Acids Res. 23:628-633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Torten, M., M. Franchini, J. E. Barlough, J. W. George, E. Mozes, H. Lutz, and N. C. Pedersen. 1991. Progressive immune dysfunction in cats experimentally infected with feline immunodeficiency virus. J. Virol. 65:2225-2230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vila-Coro, A. J., M. Mellado, A. Martin de Ana, P. Lucas, G. del Real, A. Martinez, and J. M. Rodriguez-Frade. 2000. HIV-1 infection through the CCR5 receptor is blocked by receptor dimerization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:3388-3393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Willett, B. J., K. Adema, N. Heveker, A. Brelot, L. Picard, M. Alizon, J. D. Turner, J. A. Hoxie, S. Peiper, J. C. Neil, and M. J. Hosie. 1998. The second extracellular loop of CXCR4 determines its function as a receptor for feline immunodeficiency virus. J. Virol. 72:6475-6481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Willett, B. J., and M. J. Hosie. 1999. The role of the chemokine receptor CXCR4 in infection with feline immunodeficiency virus. Mol. Membr. Biol. 16:67-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Willett, B. J., M. J. Hosie, T. H. Dunsford, J. C. Neil, and O. Jarrett. 1991. Productive infection of T-helper lymphocytes with feline immunodeficiency virus is accompanied by reduced expression of CD4. AIDS 5:1469-1475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Willett, B. J., M. J. Hosie, J. C. Neil, J. D. Turner, and J. A. Hoxie. 1997. Common mechanism of infection by lentiviruses. Nature 385:587.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Willett, B. J., M. J. Hosie, A. R. E. Shaw, and J. C. Neil. 1997. Inhibition of feline immunodeficiency virus infection by CD9 antibody operates after virus entry and is independent of virus tropism. J. Gen. Virol. 78:611-618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Willett, B. J., L. Picard, M. J. Hosie, J. D. Turner, K. Adema, and P. R. Clapham. 1997. Shared usage of the chemokine receptor CXCR4 by the feline and human immunodeficiency viruses. J. Virol. 71:6407-6415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]