Abstract

Metal ions play crucial roles in thermal stability and folding kinetics of nucleic acids. For ions (especially multivalent ions) in the close vicinity of nucleic acid surface, interion correlations and ion-binding mode fluctuations may be important. Poisson-Boltzmann theory ignores these effects whereas the recently developed tightly bound ion (TBI) theory explicitly accounts for these effects. Extensive experimental data demonstrate that the TBI theory gives improved predictions for multivalent ions (e.g., Mg2+) than the Poisson-Boltzmann theory. In this study, we use the TBI theory to investigate how the metal ions affect the folding stability of B-DNA helices. We quantitatively evaluate the effects of ion concentration, ion size and valence, and helix length on the helix stability. Moreover, we derive practically useful analytical formulas for the thermodynamic parameters as functions of finite helix length, ion type, and ion concentration. We find that the helix stability is additive for high ion concentration and long helix and nonadditive for low ion concentration and short helix. All these results are tested against and supported by extensive experimental data.

INTRODUCTION

Nucleic acid molecules are highly charged polyanion. In the folding of nucleic acids, the cations, such as sodium and magnesium ions, are required to neutralize the negative charges on the backbones to reduce the repulsive Coulombic interactions between the phosphates, so that the nucleic acid molecules can fold into the compact native structures. Ionic properties, such as ion concentration, charge, and size, play important roles in determining the stability and folding kinetics of nucleic acids (1–16).

Helices, which are formed by a train of consecutive basepairs, constitute the most important components in nucleic acid structures. Much effort has been devoted to the study of the helix stability. Most experimental measurements for the helix thermal stability are for the 1 M Na+ salt condition (16–23). Our understanding of the helix stability under other ion conditions, especially in multivalent ion conditions, is quite limited (24–32). For example, previous studies examined the Na+ or K+-dependence of the helix melting temperature (22,33–35), and the folding free energy for DNA helix formation was extrapolated from the standard 1 M Na+ condition to other Na+ concentration (≥0.1 M) (22). These empirically fitted extrapolations were mainly focused on the NaCl solution, not for the Mg2+ or other multivalent ion solutions (36–39). On the other hand, extensive experiments have demonstrated the essential role of Mg2+ in nucleic acids (3–5,10–14). For example, Mg2+ ions are found to be much more effective than Na+ ions in stabilizing the DNA and RNA helices (36–39). Motivated by the desire to understand quantitatively the role of Mg2+ and other ions in the stabilization of DNA and RNA helices (40), we investigate the folding stability of DNA helix of finite length in the Mg2+ solution.

There have been two successful polyelectrolyte theories: the counterion condensation (CC) theory (41–43) and the Poisson-Boltzmann (PB) theory (44–51). The CC theory assumes a two-state ion distribution, and assumes a mean uniform distribution of condensed ions along the polyelectrolyte. In addition, the original CC theory is a double-limit law, i.e., it is for dilute salt solution and for nucleic acids of infinite length (41,52–54). The PB theory is a mean-field theory and ignores the interion correlation, which can be important for multivalent ions (e.g., Mg2+). Recently, to treat the correlations and fluctuations for bound ions, we developed a tightly bound ion (TBI) model (55). The basic idea of the model is to separate the tightly bound ions from the diffusive ions in solution. The model explicitly accounts for the discrete modes of ion binding and the correlation between the tightly bound ions, and treat the bulk solvent ions using the PB. The model has been validated through extensive comparisons with Monte Carlo simulations. The TBI model agrees with PB and CC for Na+ ions, of which the correlational effect is weak, and predicts improved results for Mg2+ (55), which can involve strong correlations.

In this study, the TBI theory is used to compute the helix-coil transition. The calculated results are validated through extensive tests against experiments. Based on the TBI model, we systematically investigate the thermodynamic stability of oligomeric DNA helices. We examine the dependence on the helix length and ion concentration for both NaCl and MgCl2 solutions. In addition, we obtain an analytical expression for the folding stability parameters as a function of the ion concentration and the helix length for the NaCl and the MgCl2 solutions.

THEORY

Thermodynamics

We model the helix as a double-stranded (ds) B-DNA helical structure and the coil as a single-stranded (ss) helical structure (see the “Structural models for dsDNA and ssDNA” section in Appendix A). The folding free energy (helix stability) ΔGT° for the helix-coil transition is calculated as the difference between the helix and the coil:

|

(1) |

Here T is the temperature, GT°(helix) and GT°(coil) are the free energies for the helix and the coil, respectively. ΔGT° is dependent on the temperature, the structures of the ds helix and the ss helix, and the solvent conditions, such as the salt concentration and the cation properties. As an approximation, we decompose ΔGT° into two parts: a nonelectrostatic contribution  and an electrostatic contribution

and an electrostatic contribution  (32,33,56–60):

(32,33,56–60):

|

(2) |

which can be called the nonelectrostatic or “chemical” part of folding free energy, comes from the strong Watson-Crick basepairing and stacking interactions. We assume that

which can be called the nonelectrostatic or “chemical” part of folding free energy, comes from the strong Watson-Crick basepairing and stacking interactions. We assume that  is salt-independent (32,33,56–60) and evaluate

is salt-independent (32,33,56–60) and evaluate  using the nearest neighbor model with the measured thermodynamic parameters for the base stacks (17–23,61). Considering 1 M NaCl as the standard salt solution for the measurement of the nearest neighbor interaction parameters, we can calculate

using the nearest neighbor model with the measured thermodynamic parameters for the base stacks (17–23,61). Considering 1 M NaCl as the standard salt solution for the measurement of the nearest neighbor interaction parameters, we can calculate  by subtracting

by subtracting  from the total folding free energy

from the total folding free energy

|

(3) |

Here the electrostatic free energy  (1 M Na+) can be calculated from the polyelectrolyte theory. The total free energy ΔGT° (1 M Na+) can be obtained from the nearest neighbor model using the experimentally measured thermodynamic parameters (17–23,61):

(1 M Na+) can be calculated from the polyelectrolyte theory. The total free energy ΔGT° (1 M Na+) can be obtained from the nearest neighbor model using the experimentally measured thermodynamic parameters (17–23,61):

|

(4) |

where ΔH° (1 M Na+) and ΔS° (1 M Na+) are the enthalpy and entropy parameters for the base stacks in the helix at 1 M NaCl, respectively. As an approximation, we neglect ΔCp, the heat capacity difference between helix and coil (62–68), so we can treat ΔH° (1 M Na+) and ΔS° (1 M Na+) as temperature-independent constants. Such approximation is valid if the temperature is not too far away from 37°C (22,64–68).

With  calculated from the polyelectrolyte theory and

calculated from the polyelectrolyte theory and  determined from Eq. 3, we can compute the folding free energy for any given NaCl or MgCl2 concentration and temperature T:

determined from Eq. 3, we can compute the folding free energy for any given NaCl or MgCl2 concentration and temperature T:

|

(5) |

Here Na+|Mg2+ denotes a pure NaCl or MgCl2 solution.

For a given strand concentration CS, the melting temperature Tm for helix-coil transition can also be obtained from the folding free energy ΔGT° (22,68):

|

(6) |

where R is the gas constant (=1.987 cal/K/mol) and CS is replaced by CS/4 for non-self-complementary sequence.

Central to the calculation of the folding stability (free energy) is the computation of the electrostatic free energy  In this study, to account for the correlation and fluctuation effect for the bound ions, we use the recently developed TBI theory to compute

In this study, to account for the correlation and fluctuation effect for the bound ions, we use the recently developed TBI theory to compute  In the next section, we briefly summarize the TBI theory. Detailed discussion about the TBI theory can be found in Tan and Chen (55).

In the next section, we briefly summarize the TBI theory. Detailed discussion about the TBI theory can be found in Tan and Chen (55).

Summary of the tightly bound ion model

In the tightly bound ion (TBI) model, ions around a polyelectrolyte are classified into two types: the (strongly correlated) tightly bound ions and the (weakly correlated) diffusively bound ions, and the space around the nucleic acid can be correspondingly divided into the tightly bound region and the diffusively bound region, respectively. The rationale to distinguish the two types of ions (and the two types of spatial regions) is to treat them differently. For the diffusive ions, we can use PB. But for the tightly bound ions, we need a separate treatment to account for the correlations.

The strong correlation between the ions are characterized by the following two conditions:

a), Strong electrostatic correlation is characterized by a large Coulomb correlation parameter Γ(r) at position r:

|

(7) |

where Γ(r) is the local correlation parameter, zq is the charge of the counterion (z is the valency of counterions and q is the proton charge), ε is the dielectric constant of the solvent, and aws(r) is the Wigner-Seitz radius given by the cation concentration c(r) in excess of the bulk concentration c0 (69):

|

(8) |

We choose Γc to be 2.6, the critical value for the gas-liquid transition to occur in an ionic system. Physically, for Γ ≥ Γc, the Coulomb correlation is so strong that the charged system starts to exhibit liquid-like local order, whereas for Γ < Γc, the system is weakly correlated and is gaseous (70–72).

b), Strong excluded volume correlation is characterized by a small interion distance d

|

(9) |

where rc is the ion radius, Δr is the mean displacement of ions fluctuated from their equilibrium positions, and 2(aws − Δr) is the closest distance between two ions before they overlap. According to Lindemann's melting theory, we choose  as the melting point for the correlated structure (73–75).

as the melting point for the correlated structure (73–75).

In the above analysis, we have implicitly assumed two types of distinguishable correlational effects: the ion-ion correlations that exist in bulk solvent (without the polyanionic nucleic acid) and the nucleic acid-induced correlations between the (bound) ions. The TBI model treats the second type correlational effects. Therefore, in the above equations, we use the excess ion concentration c(r) − c0 rather than the local concentration c(r) in an attempt to account for the “excess” correlational effect induced by the nucleic acid for the bound ions. It is important to note that the use of the excess ion concentration is a rather crude approximation because, rigorously speaking, the above two types correlational effects are inseparable.

Ions that satisfy either of the above two correlation criteria (Eqs. 7 and 9) are classified as the tightly bound ions. The key to determine the tightly bound region is to obtain the ion concentration c(r). As a crude approximation, we calculate c(r) through the nonlinear PB equation

|

(10) |

|

(11) |

Here, α denotes the ion species, zαq is the charge of the ion, cα0 is the bulk ion concentration. ρf is the charge density of the fixed charges, ε0 is the permittivity of free space, and ψ(r) is the electrostatic potential at r. We have developed a three-dimensional finite-difference algorithm to numerically solve nonlinear PB for ψ(r) and c(r) (55). From c(r), the tightly bound region is quantitatively and unambiguously defined. In Fig. 1, we show examples of the tightly bound regions around a ssDNA and a dsDNA helix in a Mg2+ solution.

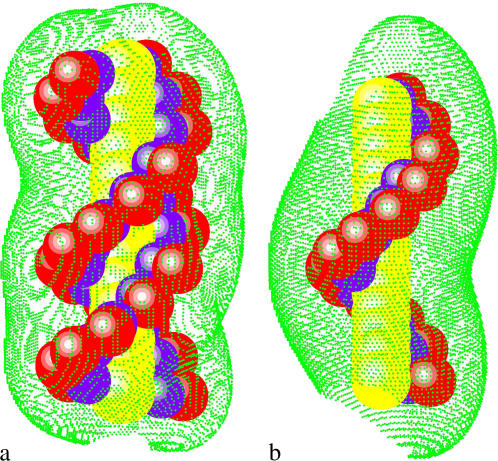

FIGURE 1.

The tightly bound regions around (a) a 13-bp dsDNA and (b) a 13-nt ssDNA in Mg2+ solutions at bulk concentration [MgCl2] = 0.1 M. The red spheres represent the phosphate groups and the green dots represent the points on the boundaries of the tightly bound regions. The dsDNA and ssDNA are produced from the grooved primitive model (see Appendix A) (55,95).

For a N-bp double-stranded nucleic acid molecule, there are 2N phosphates. We divide the whole tightly bound region into 2N cells, each around a phosphate. In a cell, say, the i-th cell, there can exist mi = 0, 1, 2… tightly bound ions. Each possible set of the 2N numbers {m1, m2, …, m2N} defines a binding mode. There exist a large number of such binding modes. For example, if we allow at most two ions in each cell, there would be 32N modes for the tightly bound ions. The total partition function Z is given by the sum over all the possible binding modes M:

|

(12) |

where ZM is the partition function for a given binding mode M.

How to compute ZM for a given binding mode M? For a mode of Nb tightly bound ions and Nd diffusively bound ions, we use Ri (i = 1, 2, …, Nb) and rj(j = 1, 2, …, Nd) to denote the coordinates of the i-th tightly bound ion and the j-th diffusive ion. The total interaction energy U(R, r) of the system for a given ion configuration  can be decomposed as three parts:

can be decomposed as three parts:

|

|

|

|

Then, ZM can be given by the following configurational integral (55)

|

(13) |

where N+ and N− are the total numbers of the cations and of the anions, respectively. In the above integral, for a given mode, Ri can distribute within the volume of the respective tightly bound cell whereas rj can distribute in the volume of the bulk solution. VR denotes the tightly bound region. The integration for Ri of the i-th tightly bound ion is over the respective tightly bound cell. Vr denotes the region for the diffusive ions. The integration for rj of the j-th diffusive ion is over the entire volume of the bulk solvent. Averaging over the possible ion distributions gives the free energies ΔGb and ΔGd for the tightly bound and for the diffusive ions, respectively (55):

|

(14) |

|

(15) |

Strictly speaking, for a given mode M, the free energy ΔGd of diffusive ions is dependent on the spatial distribution R of the tightly bound ions in the tightly bound cells. However, assuming the dependence of ΔGd on the tightly bound ions is mainly through the net tightly bound charge, which is fixed for a given mode, we can ignore the R-dependence of ΔGd. In practice, we approximate ΔGd by  where

where  is the mean value of R.

is the mean value of R.

The decoupling of R and ΔGd causes the separation of the R and the r variables in the configurational integral for ZM, resulting in the following expression for ZM (55):

|

(16) |

Here, Z(id) is the partition function for the uniform solution without inserting the polyelectrolyte. The volume integral  provides a measure for the free accessible space for the Nb tightly bound ions. To obtain ZM from Eq. 16, we need to calculate the free energies ΔGb and ΔGd.

provides a measure for the free accessible space for the Nb tightly bound ions. To obtain ZM from Eq. 16, we need to calculate the free energies ΔGb and ΔGd.

To calculate ΔGb, we note that the electrostatic interaction potential energy inside the tightly bound region Ub can be written as the sum of all the possible charge-charge interactions:

|

Here uii is the Coulomb interactions between the charges in cell i and uij is the Coulomb interactions between the charges in cell i and in cell j. We compute the potential of mean force Φ1(i) for uii and Φ2(i, j) for uij:

|

(17) |

Here, the averaging is over the possible positions (Ri, Rj) of the tightly bound ion(s) in the respective tightly bound cell(s). From Φ1(i) and Φ2(i, j), we have

|

(18) |

For ΔGd, from the mean-field theory for the diffusive ions (76,77), we have (55):

|

(19) |

where the two integrals correspond to the enthalpic and entropic parts of the free energy, respectively. ψ′(r) is the electrostatic potential for the system without the diffusive salt ions. ψ′(r) is introduced because ψ(r) − ψ′(r) gives the contribution of the diffusive ions. ψ(r) and ψ′(r) are obtained from the nonlinear PB (Eq. 10) and the Poisson equation (without ions), respectively.

From the above equations, the electrostatic free energy can be computed as

|

(20) |

From Eq. 3 for the nonelectrostatic part ( ) and Eq. 20 for the electrostatic part (

) and Eq. 20 for the electrostatic part ( ), we can compute the free energy of a nucleic acid in the ds helix and the ss helix (coil) state, respectively. The free energy difference gives the stability of the ds helix structure, or, the folding free energy for the helix-coil transition.

), we can compute the free energy of a nucleic acid in the ds helix and the ss helix (coil) state, respectively. The free energy difference gives the stability of the ds helix structure, or, the folding free energy for the helix-coil transition.

In summary, the computation of the helix stability with the TBI theory involves the following steps (55):

First, for a polyanion molecule in salt solution, we solve the nonlinear PB (NLPB) to obtain the ion distribution c(r) around the molecule, from which we determine the tightly bound region from Eqs. 7–9. In the nonlinear PB, we use dielectric constants ε = 2 and 78 for the regions inside and outside the helix. We assign Debye-Huckel parameter κD = 0 for the ion-inaccessible region for the ions (helix plus a charge-free layer with the thickness equal to the cation radius) and a nonzero κD determined by the ion concentration for the ion-accessible region (55).

Second, using Eq. 17, we compute the pairwise potential of mean force Φ1(i) and Φ2(i, j) for different cells (i and j's). Φ1 and Φ2 are calculated by averaging over all the possible positions of the tightly bound ions inside the respective tightly bound cells. The excluded volume effect is accounted for in the averaging (integration) process.

Third, we enumerate the possible binding modes. For each binding mode M: a), we solve the NLPB to obtain the distribution of the diffusive ions; b), from Eq. 19, we calculate the free energy for the diffusive ions and the interaction between the diffusive ions and the tightly bound ions ΔGd; c), with the precalculated Φ1 and Φ2, we calculate the free energy of the tightly bound ions from Eq. 18; d), from Eq. 16, we compute the partition function ZM for the mode.

Summing over the different binding modes gives the total partition function Z, from which we can calculate the free energy of the structure (ds or ss helix).

RESULTS

We investigate the ion-dependence of the folding thermodynamics for the helix-coil transition for a series of oligomeric DNAs of different lengths and sequences. In Table 1, we list the sequences, the thermodynamic parameters (ΔH°, ΔS°, ΔG°) in 1 M NaCl calculated from the nearest neighbor model, and the nonelectric part of the folding free energy  at T = 37°C. To calculate

at T = 37°C. To calculate  we calculate

we calculate  using the PB theory and the TBI model, respectively. From

using the PB theory and the TBI model, respectively. From  we obtain

we obtain  from Eq. 3. In the following section, we will discuss the ion-dependence of the thermal stability of oligomeric DNA helices. Throughout the discussion, we focus on the comparisons with the available experimental data as well as with the results from the PB theory.

from Eq. 3. In the following section, we will discuss the ion-dependence of the thermal stability of oligomeric DNA helices. Throughout the discussion, we focus on the comparisons with the available experimental data as well as with the results from the PB theory.

TABLE 1.

The DNA sequences used in the calculations

| Sequence | N (bp) | Experiment reference | −ΔH° (kcal/mol)* | −ΔS° (cal/mol.K)* | −ΔG°37 (kcal/mol)* |

† †

|

‡ ‡

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GCAGC | 5 | – | 35.7 | 98.1 | 5.3 | 3.9 | 4.0 |

| GCATGC | 6 | (36) | 43.6 | 121.6 | 5.9 | 4.3 | 4.5 |

| CCAAACA | 7 | (78) | 46.8 | 130.8 | 6.2 | 4.2 | 4.5 |

| GGAATTCC | 8 | (79–81) | 55.2 | 156.0 | 6.8 | 4.5 | 4.8 |

| GCCAGTTAA | 9 | (37) | 63.1 | 174.8 | 8.9 | 6.3 | 6.7 |

| ATCGTCTGGA | 10 | (35,82) | 70.5 | 192.0 | 11.0 | 8.0 | 8.5 |

| CCATTGCTACC | 11 | (35) | 81.1 | 222.5 | 12.1 | 8.8 | 9.4 |

| CAAAGATTCCTC | 12 | (83) | 87.4 | 243.8 | 11.8 | 8.2 | 9.0 |

| AGAAAGAGAAGA | 12 | (84,85) | 83.1 | 231.2 | 11.4 | 7.8 | 8.6 |

| CCAAAGATTCCTC | 13 | – | 95.4 | 263.7 | 13.6 | 9.6 | 10.4 |

The thermodynamic data are calculated at standard state (1 M NaCl) through the nearest-neighbor model with the thermodynamic parameters of SantaLucia (22).

is computed from Eq. 3 with

is computed from Eq. 3 with  calculated from the Poisson-Boltzmann theory.

calculated from the Poisson-Boltzmann theory.

is calculated from Eq. 3 with

is calculated from Eq. 3 with  calculated through the tightly bound ion model. For each of the listed sequences, we have performed the thermodynamic calculations for both the NaCl and the MgCl2 solutions of different ion concentrations.

calculated through the tightly bound ion model. For each of the listed sequences, we have performed the thermodynamic calculations for both the NaCl and the MgCl2 solutions of different ion concentrations.

Salt concentration-dependence of the helix stability at 37°C

Electrostatic free energies G37el and ΔG37el

The electrostatic contribution to helix stability is quantified by the electrostatic folding free energy

|

(21) |

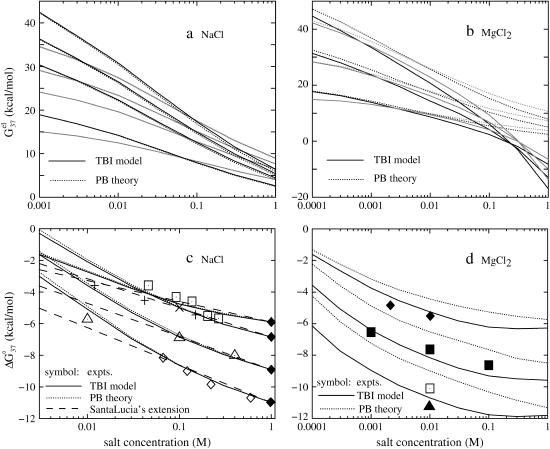

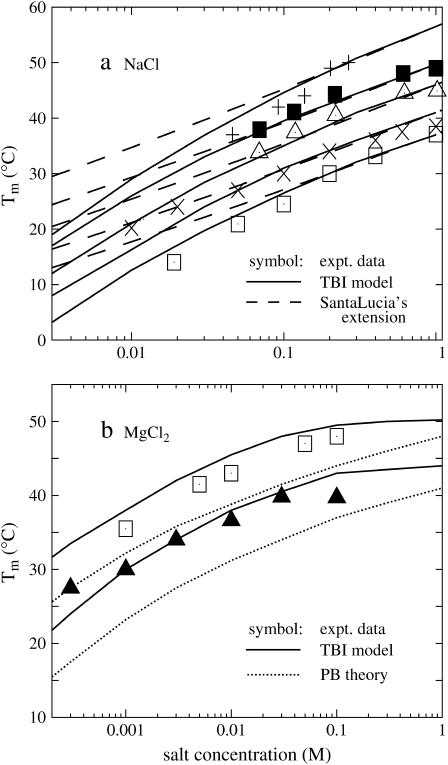

First, we calculate the electrostatic part of free energy  for the helix (dsDNA) and for the coil (ssDNA), respectively, as a function of the NaCl or MgCl2 concentration. We show the results in Fig. 2, a and b, from which we make the following observations.

for the helix (dsDNA) and for the coil (ssDNA), respectively, as a function of the NaCl or MgCl2 concentration. We show the results in Fig. 2, a and b, from which we make the following observations.

FIGURE 2.

(a,b) The electrostatic free energy  for dsDNA (black lines) and the respective ssDNA (gray lines) as functions of (a) NaCl and (b) MgCl2 concentrations. (Dotted lines) Poisson-Boltzmann theory; (solid lines) the TBI theory. (a) DNA length N are 10, 9, 8, and 6 bp (from the top to bottom), respectively; (b) DNA length N are 12, 9, and 6 bp (from the top to bottom), respectively. (c,d) The folding free energies ΔG°37 due to dsDNA helix formation for different sequences of various lengths in (c) NaCl and (d) MgCl2 solutions. (Dotted lines) Poisson-Boltzmann theory; (solid lines) the TBI theory; (dashed lines) SantaLucia's salt extrapolation formula for NaCl (22,40). (c) The sequences used for NaCl solution are: GCATGC, GGAATTCC, GCCAGTTAA, and ATCGTCTGGA (from the top to bottom). The symbols are the experimental data. + GCATGC (36); □ GGAATTCC (79); × GGAATTCC (80); ▵ GCCAGTTAA (37); ⋄ ATCGTCTGGA (82); ♦ are calculated from the nearest neighbor model with the thermodynamic parameters of SantaLucia at 1 M NaCl (22). (d) The sequences used for MgCl2 are: GCATGC, GCCAGTTAA, and AGAAAGAGAAGA (from the top to bottom). The symbols are the experimental data: ▪ GCCAGTTAA in MgCl2 (37); □ AGAAAGAGAAGA in MgCl2 (84); ▴ AGAAAGAGAAGA in MgCl2 (85); ♦ GCATGC in NaCl/MgCl2 mixed solution with 0.012 M NaCl (36). The experimental data in NaCl/MgCl2 mixed solutions for GCATGC are used for semiquantitative comparison because NaCl is at very low concentration (36). For the MgCl2 solutions, the values of

for dsDNA (black lines) and the respective ssDNA (gray lines) as functions of (a) NaCl and (b) MgCl2 concentrations. (Dotted lines) Poisson-Boltzmann theory; (solid lines) the TBI theory. (a) DNA length N are 10, 9, 8, and 6 bp (from the top to bottom), respectively; (b) DNA length N are 12, 9, and 6 bp (from the top to bottom), respectively. (c,d) The folding free energies ΔG°37 due to dsDNA helix formation for different sequences of various lengths in (c) NaCl and (d) MgCl2 solutions. (Dotted lines) Poisson-Boltzmann theory; (solid lines) the TBI theory; (dashed lines) SantaLucia's salt extrapolation formula for NaCl (22,40). (c) The sequences used for NaCl solution are: GCATGC, GGAATTCC, GCCAGTTAA, and ATCGTCTGGA (from the top to bottom). The symbols are the experimental data. + GCATGC (36); □ GGAATTCC (79); × GGAATTCC (80); ▵ GCCAGTTAA (37); ⋄ ATCGTCTGGA (82); ♦ are calculated from the nearest neighbor model with the thermodynamic parameters of SantaLucia at 1 M NaCl (22). (d) The sequences used for MgCl2 are: GCATGC, GCCAGTTAA, and AGAAAGAGAAGA (from the top to bottom). The symbols are the experimental data: ▪ GCCAGTTAA in MgCl2 (37); □ AGAAAGAGAAGA in MgCl2 (84); ▴ AGAAAGAGAAGA in MgCl2 (85); ♦ GCATGC in NaCl/MgCl2 mixed solution with 0.012 M NaCl (36). The experimental data in NaCl/MgCl2 mixed solutions for GCATGC are used for semiquantitative comparison because NaCl is at very low concentration (36). For the MgCl2 solutions, the values of  from the TBI theory are used in the calculations of ΔG37°.

from the TBI theory are used in the calculations of ΔG37°.

Higher ion concentration leads to lower electrostatic free energy  This is because higher concentration corresponds to less entropy loss upon binding of the ion and thus enhances ion-binding. Moreover, the stabilization by higher ion concentration is more pronounced for ds helix than for ss helix (coil). As shown in Fig. 2, a and b,

This is because higher concentration corresponds to less entropy loss upon binding of the ion and thus enhances ion-binding. Moreover, the stabilization by higher ion concentration is more pronounced for ds helix than for ss helix (coil). As shown in Fig. 2, a and b,  of dsDNA decreases more rapidly than

of dsDNA decreases more rapidly than  of ssDNA (the curves of black lines are steeper than the ones of gray lines in the figure). This is because dsDNA is more negatively charged than ssDNA (see Appendix A for the structures of the dsDNA and the ssDNA) and the stronger electrostatic effect leads to more pronounced increase of bound ions for higher salt concentration. As a result, higher salt concentration leads to a lower

of ssDNA (the curves of black lines are steeper than the ones of gray lines in the figure). This is because dsDNA is more negatively charged than ssDNA (see Appendix A for the structures of the dsDNA and the ssDNA) and the stronger electrostatic effect leads to more pronounced increase of bound ions for higher salt concentration. As a result, higher salt concentration leads to a lower  (see Eq. 1), i.e., higher salt concentration tends to stabilize the helix.

(see Eq. 1), i.e., higher salt concentration tends to stabilize the helix.

From Fig. 2 a, we find that PB and TBI give nearly the same results for the NaCl solution. This is because the interion correlations are negligible for the NaCl solution considered here (55). However, for MgCl2 solution, as shown in Fig. 2 b, we find that the TBI model gives lower free energy than the PB. This is because the low-energy correlated states of the bound Mg2+ ions, which are explicitly considered in TBI, are neglected in the PB. The average mean-field states considered in PB have higher energies than the low-energy correlated states, causing the PB to underestimate the helix stability in the MgCl2 solution.

Folding free energy ΔG37°

Combining the electrostatic free energy  and the chemical free energy

and the chemical free energy  we obtain the total free energy ΔG37° (= the ds helix stability). We investigate the dependence of the helix stability as a function of the NaCl and the MgCl2 concentrations for different DNA sequences and different helix lengths. Fig. 2, c and d, show our computed results as well as the experimental results.

we obtain the total free energy ΔG37° (= the ds helix stability). We investigate the dependence of the helix stability as a function of the NaCl and the MgCl2 concentrations for different DNA sequences and different helix lengths. Fig. 2, c and d, show our computed results as well as the experimental results.

As we expected, both Fig. 2, c and d, show that higher ion concentration supports higher helix stability (lower ΔG37°). This is because, as we discussed above, higher ion concentration gives lower electrostatic folding free energy

In both the NaCl (Fig. 2 c) and the MgCl2 (Fig. 2 d) solutions, longer helices have lower  and thus are more stable than shorter ones. This is because longer helix means stronger attractive electric field for bound ions, and this effect is stronger for ds helix, which is more negatively charged, than for coil.

and thus are more stable than shorter ones. This is because longer helix means stronger attractive electric field for bound ions, and this effect is stronger for ds helix, which is more negatively charged, than for coil.

Besides the PB and TBI computational results, also plotted in Fig. 2 c for the NaCl solution are the experimental data and the results from SantaLucia's empirical extrapolated [Na+]-dependence of ΔG37° (22,40). As we discussed above, PB and TBI give the same results for NaCl solution. From Fig. 2 c, we find that, as tested against experiments, both theories give good results. Moreover, we find that SantaLucia's salt-dependence gives good results for [Na+] between 0.1 and 1 M NaCl, and overestimates the helix stability for [Na+] < 0.1 M.

Shown in Fig. 2 d is the MgCl2 concentration-dependence of the electrostatic free energy ΔG37°. We find that both PB and TBI predict the same qualitative dependence of ΔG37° in MgCl2 concentration. However, compared with the experimental data for the three tested sequences GCATGC (36), GCCAGTTAA (37), and AGAAAGAGAAGA (84,85), TBI gives improved predictions than PB. As we discussed above, PB underestimates the helix stability owing to the neglected correlations between the bound Mg2+ ions. Fig. 2 d shows that the helix stability saturates at high MgCl2 concentration (>0.03 M).

Temperature-dependence of helix stability

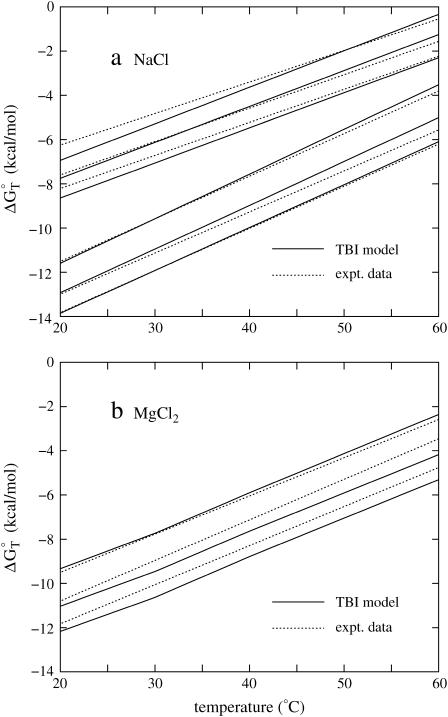

Temperature-dependence of the total stability ΔGT°

We calculate the folding free energy ΔGT° from Eq. 5 for NaCl and MgCl2 solutions for different temperatures. We use the temperature-dependent dielectric constant of water in Eq. 33 (86). For both the Na+ and Mg2+ salt solutions, as shown in Fig. 3, a and b, helix is more stable (i.e., is more negative ΔGT° = ΔH° − TΔS°) for lower temperatures. Also, we find that for all the tested sequences and ion concentrations, the TBI theory gives good predictions for the helix stability as tested against experiments. To understand the electrostatic contribution to the helix stability, we further investigate the temperature-dependence of the electrostatic part of the folding free energy  (see Eq. 21).

(see Eq. 21).

FIGURE 3.

The temperature-dependence of the folding free energy ΔG°T for (a) NaCl and (b) MgCl2 solutions. (Solid lines) The TBI theory; (dotted lines) experimental data with the use of the equation ΔGT° = ΔH° − TΔS°, where ΔH° and ΔS° are taken from experiments. (a) The upper three lines are for sequence GGAATTCC at 0.046, 0.1, and 0.267 M NaCl (from the top to bottom) (79,80), and the bottom three lines are for sequence ATCGTCTGGA at 0.069, 0.22, and 0.62 M NaCl (from the top to bottom) (82). (b) The three lines are for sequence GCCAGTTAA at 1, 10, and 100 mM MgCl2 (from the top to bottom) (37).

Temperature-dependence of the electrostatic folding free energy ΔGTel

As shown in Fig. 4, in both the NaCl and the MgCl2 solutions, the temperature-dependence of the electrostatic folding free energy  is much weaker than that of the total free energy (net stability) ΔGT°. So the strong temperature-dependence of helix stability predominantly comes from the temperature-dependence of the nonelectrostatic part

is much weaker than that of the total free energy (net stability) ΔGT°. So the strong temperature-dependence of helix stability predominantly comes from the temperature-dependence of the nonelectrostatic part

FIGURE 4.

The temperature-dependence of the electrostatic part of the free energy. (a,b) The electrostatic free energy  of dsDNA (solid lines) and ssDNA (dashed lines) as functions of temperature: (a) for a 10-bp dsDNA and the respective ssDNA at 3 mM, 10 mM, 30 mM, 69 mM, 220 mM, and 1 M NaCl (from the top to bottom); (b) for a 9-bp dsDNA and the respective ssDNA at 0.1, 0.3, 1, 10, and 100 mM MgCl2 (from the top to bottom). (c,d) The temperature-dependence of electrostatic contribution

of dsDNA (solid lines) and ssDNA (dashed lines) as functions of temperature: (a) for a 10-bp dsDNA and the respective ssDNA at 3 mM, 10 mM, 30 mM, 69 mM, 220 mM, and 1 M NaCl (from the top to bottom); (b) for a 9-bp dsDNA and the respective ssDNA at 0.1, 0.3, 1, 10, and 100 mM MgCl2 (from the top to bottom). (c,d) The temperature-dependence of electrostatic contribution  to folding free energy for dsDNA helix formation in (c) NaCl and (d) MgCl2 solutions. (Dotted lines) Poisson-Boltzmann theory; (solid lines) the TBI theory. (c) Sequence ATCGTCTGGA at 3 mM, 10 mM, 30 mM, 69 mM, 220 mM, and 1 M NaCl (from the top to bottom); (d) sequence GCCAGTTAA at 0.1, 0.3, 1, 10, and 100 mM MgCl2 (from the top to bottom).

to folding free energy for dsDNA helix formation in (c) NaCl and (d) MgCl2 solutions. (Dotted lines) Poisson-Boltzmann theory; (solid lines) the TBI theory. (c) Sequence ATCGTCTGGA at 3 mM, 10 mM, 30 mM, 69 mM, 220 mM, and 1 M NaCl (from the top to bottom); (d) sequence GCCAGTTAA at 0.1, 0.3, 1, 10, and 100 mM MgCl2 (from the top to bottom).

In the Na+ salt solution

Plotted in Fig. 4 c is the temperature-dependence of  for different NaCl concentrations for a 10-bp dsDNA. We find that

for different NaCl concentrations for a 10-bp dsDNA. We find that  is weakly dependent on temperature. As temperature is increased,

is weakly dependent on temperature. As temperature is increased,  decreases at high NaCl concentration and increases at low NaCl concentration. Such temperature-dependence is predicted by both PB and TBI. The temperature-dependence of electrostatic free energy can be understood from the temperature-dependence of the dielectric constant ε of the solvent (see Eq. 33): At higher temperature, ε is smaller, resulting in stronger Coulomb interactions. As explained below, the Coulomb interactions can be strengthened differently in dsDNA and ssDNA, resulting in the temperature-dependence of

decreases at high NaCl concentration and increases at low NaCl concentration. Such temperature-dependence is predicted by both PB and TBI. The temperature-dependence of electrostatic free energy can be understood from the temperature-dependence of the dielectric constant ε of the solvent (see Eq. 33): At higher temperature, ε is smaller, resulting in stronger Coulomb interactions. As explained below, the Coulomb interactions can be strengthened differently in dsDNA and ssDNA, resulting in the temperature-dependence of

For low [Na+], ion binding is accompanied by a large entropic decrease and thus there are only few bound ions and weak charge neutralization. In such a case, the repulsive interactions between the phosphates dominate. dsDNA has higher phosphate charge density and thus the increase of the repulsive Coulomb interactions (due to the smaller ε at higher temperature) is stronger than ssDNA, causing an increase of  as the temperature is increased.

as the temperature is increased.

For high NaCl concentration, more ions are bound, causing strong charge neutralization. Because the ds helix has much greater charge neutralization than ss helix (coil), as temperature is increased, the increase in the electrostatic interaction in ssDNA is more significant than in dsDNA (see Fig. 4 a), causing a decrease in

In the Mg2+ salt solution

As shown in Fig. 4 d for a 9-bp dsDNA immersed in a MgCl2 solution,  decreases slightly with increasing temperature over a wide range of MgCl2 concentration (

decreases slightly with increasing temperature over a wide range of MgCl2 concentration (  0.1 mM MgCl2). dsDNA has more bound ions and stronger charge neutralization than ssDNA, e.g., for 0.1 mM [MgCl2], our TBI theory predicts that at 37°C, the tightly bound Mg2+ ions can neutralize 35% of the phosphate charge for a 9-bp dsDNA as compared to only 5% for the corresponding 9-nt ssDNA. So the Coulomb interaction in ssDNA is strengthened more significantly with the increase of temperature than that in dsDNA, resulting in a decrease in

0.1 mM MgCl2). dsDNA has more bound ions and stronger charge neutralization than ssDNA, e.g., for 0.1 mM [MgCl2], our TBI theory predicts that at 37°C, the tightly bound Mg2+ ions can neutralize 35% of the phosphate charge for a 9-bp dsDNA as compared to only 5% for the corresponding 9-nt ssDNA. So the Coulomb interaction in ssDNA is strengthened more significantly with the increase of temperature than that in dsDNA, resulting in a decrease in  with the increase of temperature. The PB theory can predict the same trend but as we discussed above, PB underestimates the stability of ions because of the neglected correlation and fluctuation effects for the Mg2+ ions.

with the increase of temperature. The PB theory can predict the same trend but as we discussed above, PB underestimates the stability of ions because of the neglected correlation and fluctuation effects for the Mg2+ ions.

Salt-dependence of the melting temperature Tm

In the above section, we found that the predicted temperature-dependence of ΔGT° from TBI agrees with the experiments for both the NaCl and the MgCl2 solutions. Here, we calculate the melting temperature Tm (through Eq. 6) and compare the calculated results with the experimental data.

In the NaCl solution

Shown in Fig. 5 a is the calculated melting temperatures Tm of dsDNA as functions of the NaCl concentration for different sequences and lengths. Also shown in the figure is the experimental data for the sequences GGAATTCC (79,80), GCCAGTTAA (37), ATCGTCTGGA (35), and CCATTGCTACC (35). From the figure we find that the predicted Tm's are in agreement with the experimental results. The increase of the NaCl concentration leads to a higher Tm (higher stability of dsDNA helix). As a comparison, we also show SantaLucia's empirical salt extension (fitted from experimental data) for the NaCl solution (22,40):

|

(22) |

FIGURE 5.

The melting temperature Tm for dsDNA of different sequences in (a) NaCl and (b) MgCl2 solutions. (Solid lines) The TBI theory; (dotted lines) Poisson-Boltzmann theory; (dashed lines) SantaLucia's salt extension for NaCl (22,40); (symbols) the experimental data. (a) The sequences and total strand concentrations CS are (from the top to bottom): + GGAATTCC at CS = 3 mM (79); ▪ CCATTGCTACC at CS = 2 μM (35); ▵ ATCGTCTGGA at CS = 2 μM (35); × GCCAGTTAA at CS = 8 μM (37); and □ GGAATTCC at CS = 18.8 μM (81). (b) The sequences and CS are (from the top to bottom): □ AGAAAGAGAAGA at CS = 6 μM (84); and ▪ GCCAGTTAA at CS = 8 μM (37). Here, the data for AGAAAGAGAAGA are taken from the duplex melting in the study of the triplex melting in MgCl2 and CS = 6 μM is the total strand concentration for triplex formation. Tm is calculated from ΔG°T − RTlnCS/6 = 0 (84).

where T°m and ΔH° are the melting temperature and the enthalpy change in 1 M NaCl solution. The above SantaLucia's empirical extension provides a good approximation for NaCl concentration between 0.1 and 1 M (22,40). We also calculate the Tm's for the experimental sequences GCATGC (36), CCAAACA (78), CAAAGATTCCTC (83). Again our calculated results agree with the experimental data.

In the MgCl2 solution

Fig. 5 b shows the melting temperatures Tm of dsDNA helix in the MgCl2 solution as a function of the ion concentration for two sequences. In contrast to the folding free energy ΔG37° in Fig. 2 d, which has very limited experimental data, more experimental data for Tm in pure MgCl2 solutions are available. We find that the Tm's predicted from the TBI model agree with the available experimental data over a wide MgCl2 concentration range from 0.3 mM to 0.3 M. Again we find that PB theory can predict the trend in the [Mg2+]-dependence of Tm but it underestimates the helix stability and the Tm due to the neglected correlation and fluctuation effects, as discussed in the previous sections.

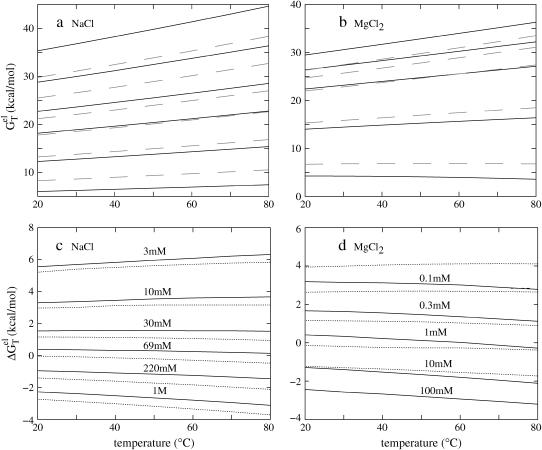

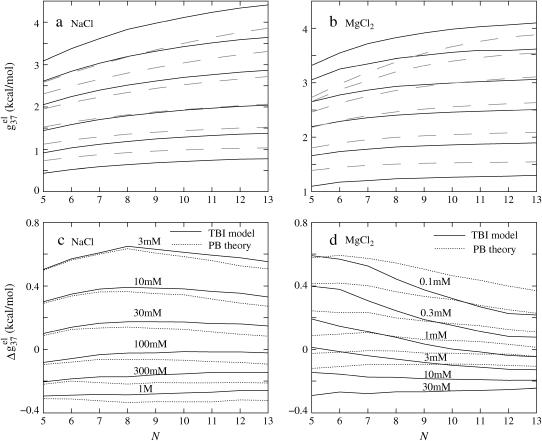

Helix length-dependence of the electrostatic folding free energy ΔG37el

In this section, we investigate the dependence of  the electrostatic component of the helix stability, on the helix length. We use the number of basepairs N to define the helix length. We will also examine how the electrostatics affects the validity of the additive nearest neighbor model for the nucleic acid helix stability (17–23). To focus on the length-dependence and the additivity effect, we study the electrostatic free energy “per base stack”

the electrostatic component of the helix stability, on the helix length. We use the number of basepairs N to define the helix length. We will also examine how the electrostatics affects the validity of the additive nearest neighbor model for the nucleic acid helix stability (17–23). To focus on the length-dependence and the additivity effect, we study the electrostatic free energy “per base stack”  and

and

Fig. 6, a and b, show the length-dependence of  for the dsDNA and the ssDNA. We find that for both ssDNA and dsDNA,

for the dsDNA and the ssDNA. We find that for both ssDNA and dsDNA,  increases rapidly with N at low salt (NaCl or MgCl2) concentrations and is only weakly dependent on N at high salt concentrations. The change in the length-dependence with the salt concentrations comes from the ion concentration-dependence of the charge neutralization (screening) effect. At low salt concentration, the neutralization is weak (the amount of bound ions is small), and the increase of helix length enhances the repulsive interactions between the charges (phosphate plus bound ion) in the backbone, causing an increased

increases rapidly with N at low salt (NaCl or MgCl2) concentrations and is only weakly dependent on N at high salt concentrations. The change in the length-dependence with the salt concentrations comes from the ion concentration-dependence of the charge neutralization (screening) effect. At low salt concentration, the neutralization is weak (the amount of bound ions is small), and the increase of helix length enhances the repulsive interactions between the charges (phosphate plus bound ion) in the backbone, causing an increased  with increased helix length (for both the ds- and the ss-helices). For high salt concentration, charge neutralization and ionic screening are strong (Debye length is short), so the increase in

with increased helix length (for both the ds- and the ss-helices). For high salt concentration, charge neutralization and ionic screening are strong (Debye length is short), so the increase in  is retarded. As explained in the following, the difference between

is retarded. As explained in the following, the difference between  of ssDNA and that of dsDNA determines electrostatic contribution to the helix stability per base stack

of ssDNA and that of dsDNA determines electrostatic contribution to the helix stability per base stack

FIGURE 6.

The length-dependence of the electrostatic part of the free energy.  and

and  are the electrostatic free energies per base stack. N − 1 is the number of base stacks for a N-bp helix. (a,b) The electrostatic free energy

are the electrostatic free energies per base stack. N − 1 is the number of base stacks for a N-bp helix. (a,b) The electrostatic free energy  (per base stack) for dsDNA (solid lines) and the respective ssDNA (dashed lines) as functions of sequence length N in NaCl (a) and MgCl2 (b) solutions. (a) [NaCl] = 3 mM, 10 mM, 30 mM, 100 mM, 300 mM, and 1 M (from the top to bottom); (b) [MgCl2] = 0.1, 0.3, 1, 3, 10, and 30 mM (from the top to bottom). (c,d) The length N-dependence of electrostatic contribution

(per base stack) for dsDNA (solid lines) and the respective ssDNA (dashed lines) as functions of sequence length N in NaCl (a) and MgCl2 (b) solutions. (a) [NaCl] = 3 mM, 10 mM, 30 mM, 100 mM, 300 mM, and 1 M (from the top to bottom); (b) [MgCl2] = 0.1, 0.3, 1, 3, 10, and 30 mM (from the top to bottom). (c,d) The length N-dependence of electrostatic contribution  (per base stack) to folding free energy for dsDNA helix formation in NaCl (c) and MgCl2 (d) solutions. (Dotted lines) Poisson-Boltzmann theory; (solid lines) the TBI theory. [NaCl] = 3 mM, 10 mM, 30 mM, 100 mM, 300 mM, and 1 M (from the top to bottom); [MgCl2] = 0.1, 0.3, 1, 3, 10, and 30 mM (from the top to bottom).

(per base stack) to folding free energy for dsDNA helix formation in NaCl (c) and MgCl2 (d) solutions. (Dotted lines) Poisson-Boltzmann theory; (solid lines) the TBI theory. [NaCl] = 3 mM, 10 mM, 30 mM, 100 mM, 300 mM, and 1 M (from the top to bottom); [MgCl2] = 0.1, 0.3, 1, 3, 10, and 30 mM (from the top to bottom).

In the NaCl solution

Shown in Fig. 6 c is the  calculated from both the PB theory and the TBI theory for different helix length N (-bp). As expected from the behavior of

calculated from both the PB theory and the TBI theory for different helix length N (-bp). As expected from the behavior of  in Fig. 6 a,

in Fig. 6 a,  is weakly dependent on N for high NaCl concentration (>0.1 M).

is weakly dependent on N for high NaCl concentration (>0.1 M).

For low NaCl concentration, the relationship between  and N becomes more complex:

and N becomes more complex:  increases with N when N is small, and decreases when N is large. Such nonmonotonic behavior can be explained as follows. At low NaCl concentration and for short DNA (small N), Na+ ion binding is weak and the repulsive phosphate-phosphate repulsion dominates

increases with N when N is small, and decreases when N is large. Such nonmonotonic behavior can be explained as follows. At low NaCl concentration and for short DNA (small N), Na+ ion binding is weak and the repulsive phosphate-phosphate repulsion dominates  Due to the long-range nature of the repulsive Coulomb interactions,

Due to the long-range nature of the repulsive Coulomb interactions,  would increase nonlinearly with length N. Furthermore, such destabilizing effect is stronger for ds helix than for ss helix (coil). As a result, the ds helix is less stable than the ss helix. With the increase of N, the ds helix becomes increasingly less stable (i.e., an increasing

would increase nonlinearly with length N. Furthermore, such destabilizing effect is stronger for ds helix than for ss helix (coil). As a result, the ds helix is less stable than the ss helix. With the increase of N, the ds helix becomes increasingly less stable (i.e., an increasing  ); see Fig. 6, a and c. If N continues to increase, the electric field near the negatively charged DNA surface will become stronger and will attract more bound Na+ ions to neutralize the phosphate charges. This would retard the increase of the electrostatic free energy

); see Fig. 6, a and c. If N continues to increase, the electric field near the negatively charged DNA surface will become stronger and will attract more bound Na+ ions to neutralize the phosphate charges. This would retard the increase of the electrostatic free energy  especially for the ds helix, which involves stronger electrostatic interactions. As a result,

especially for the ds helix, which involves stronger electrostatic interactions. As a result,  decreases.

decreases.

For high [NaCl], as shown in Fig. 6 c,  is approximately independent of N. So

is approximately independent of N. So  is additive for high NaCl concentrations (17–23). But for low NaCl,

is additive for high NaCl concentrations (17–23). But for low NaCl,  is N-dependent. As a result, the additivity may fail.

is N-dependent. As a result, the additivity may fail.

Also shown in the figure is that PB and the TBI theory give nearly identical results for short DNA at low NaCl concentration. With the increase of DNA length and increase of NaCl concentration, there exist very small differences between the two theories owing to the increased number of the (strongly correlated) ions in the tightly bound region. For example, for a 13-bp DNA at 1 M NaCl, the difference between the two theories is ∼0.07 kcal/mol per base stack.

In the MgCl2 solution

For the MgCl2 solutions, the helix length N-dependence of  is shown in Fig. 6 d. For high MgCl2 concentration, the dependence is rather weak due to the large charge neutralization. For low MgCl2 concentration, ds helix is electrostatically unstable (

is shown in Fig. 6 d. For high MgCl2 concentration, the dependence is rather weak due to the large charge neutralization. For low MgCl2 concentration, ds helix is electrostatically unstable ( ), and

), and  decreases rapidly with the increase of N when N is small, and become saturated when N is large. This is because as N is increased, the strong negative electric field near DNA surface causes an increased tendency of ion binding and charge neutralization, and such effect is stronger for ds helix than for ss helix, causing a decrease in

decreases rapidly with the increase of N when N is small, and become saturated when N is large. This is because as N is increased, the strong negative electric field near DNA surface causes an increased tendency of ion binding and charge neutralization, and such effect is stronger for ds helix than for ss helix, causing a decrease in  When N becomes sufficiently large, both ds and ss helix can have strong charge neutralization, so the decrease of

When N becomes sufficiently large, both ds and ss helix can have strong charge neutralization, so the decrease of  with longer length would slow down (saturate). In addition, it can be seen that PB and TBI give similar results for short N and low MgCl2 concentration because of the smaller number of bound ions and hence the weaker correlational effect. For large N and high [MgCl2], more Mg2+ ions are bound near the DNA and these ions become strongly correlated. In such cases, the TBI model gives improved predictions (55).

with longer length would slow down (saturate). In addition, it can be seen that PB and TBI give similar results for short N and low MgCl2 concentration because of the smaller number of bound ions and hence the weaker correlational effect. For large N and high [MgCl2], more Mg2+ ions are bound near the DNA and these ions become strongly correlated. In such cases, the TBI model gives improved predictions (55).

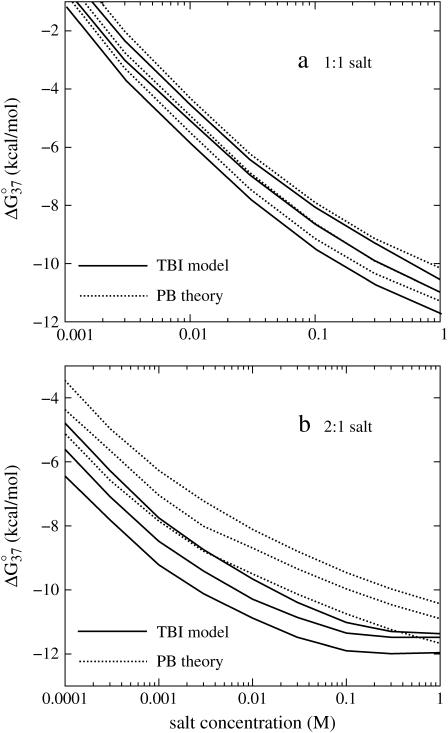

Effect of the cation size on DNA stability

To investigate the effect of the cation size on the helix stability, we choose different radii for the (hydrated) monovalent and divalent cations. Specifically, we use 3, 3.5, and 4 Å for monovalent ions and 4, 4.5, and 5 Å for the divalent ions. Fig. 7 shows the folding free energy ΔG37° as a function of ion concentration and ion size for sequence ATCGTCTGGA. We find that smaller cations support higher stability of dsDNA. We also find that different cation sizes give almost the same trend of the salt concentration-dependence of ΔG37°. Through experimental comparisons, we find that ion radius of 3.5 Å for Na+ and 4.5 Å for Mg2+ can give the best fit for the experimental results for the helix stability and the melting temperature.

FIGURE 7.

The folding free energies ΔG°37 for dsDNA helix formation as functions of (a) 1:1 and (b) 2:1 salt concentrations for sequence ATCGTCTGGA. (Solid lines) The TBI theory; (dotted lines) Poisson-Boltzmann theory. (a) The radii of monovalent cations are: 3, 3.5, and 4 Å (from the bottom to top). (b) The radii of divalent cations are: 4, 4.5, and 5 Å (from the bottom to top), respectively.

Small cations are more effective in stabilizing dsDNA because they can approach the phosphates and the grooves at a closer distance and can thus interact with DNA more strongly. Because dsDNA is more negatively charged than the corresponding ssDNA, the ion size-induced enhancement of the ion binding is stronger for dsDNA than for ssDNA. Thus, dsDNA becomes more stable in smaller cation solutions.

The predictions are in accordance with the experiments on dsDNA helix melting in various salt solutions (37). Recent experiments on RNA folding have also shown that smaller cations can stabilize RNA tertiary structure more effectively than larger ions (13). For more complex nucleic acid structure, the ion size can affect the ion-binding affinity through the compatibility with the geometry of binding site.

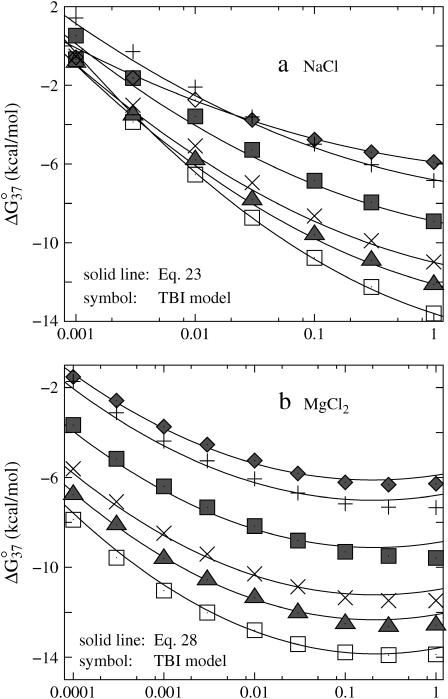

Thermodynamic parameters as functions of the ion concentration and the helix length

The availability of the (empirical) thermodynamic parameters for nucleic acids is limited by the availability of the experimental data. For example, for nucleic acids in NaCl solution, most experimental studies have been focused on high NaCl concentrations (e.g., 1 M), and thus the empirical salt-dependence fitted from the experiments are valid only for relatively high [Na+] (  0.1 M NaCl) (22,40). Moreover, there are very limited experimental data on the Mg2+-dependence for different helix lengths. Therefore, it is desirable to have analytical formulas for the thermodynamic parameters as a function of [Na+], [Mg2+], and the helix length N (-bp). Such formulas would be practically valuable for thermodynamic studies of nucleic acid stability. In this section, based on the TBI model and the comparisons with the available experimental data for DNA helix melting (22,32–35,40,87), we derive such empirical formulas.

0.1 M NaCl) (22,40). Moreover, there are very limited experimental data on the Mg2+-dependence for different helix lengths. Therefore, it is desirable to have analytical formulas for the thermodynamic parameters as a function of [Na+], [Mg2+], and the helix length N (-bp). Such formulas would be practically valuable for thermodynamic studies of nucleic acid stability. In this section, based on the TBI model and the comparisons with the available experimental data for DNA helix melting (22,32–35,40,87), we derive such empirical formulas.

NaCl solutions

By computing ΔG°37 for a wide range of DNA helix length and Na+ concentrations using the TBI theory, we obtain the following (fitted) analytical expression for ΔG°37 as a function of [Na+] and N (number of basepairs in the helix):

|

(23) |

Here (N − 1) is the number of base stacks in the helix and Δg1 is a function associated with the electrostatic folding free energy per base stack:

|

(24) |

|

(25) |

The above empirical expression for the folding free energy gives good fit with the TBI results for NaCl concentration from 1 mM to 1 M (shown in Fig. 8 a). Assuming that the salt-dependence of ΔGT° is mainly entropic, i.e., enthalpy change ΔH° is mainly independent of NaCl concentration (22,25,30,40,41), we obtain the following expression for the entropy change ΔS° (in cal/mol/K) for the helix → coil transition.

|

(26) |

FIGURE 8.

The free energy change ΔG°37 for dsDNA helix formation as functions of (a) NaCl and (b) MgCl2 concentrations for the sequences: GCATGC, GGAATTCC, GCCAGTTAA, ATCGTCTGGA, CCATTGCTACC, and CCAAAGATTCCTC (from the top to bottom). (a) (Solid lines) The empirical relation Eq. 23; (symbols) calculated from the TBI theory. (b) (Solid lines) The empirical relation Eq. 28; (symbols) calculated from the TBI theory.

From Eqs. 23 and 26, neglecting the temperature-dependence of the enthalpy and entropy parameters, we obtain the following expression for the folding free energy ΔG°T for any given temperature T and Na+ concentration: ΔG°T([Na+]) = ΔH°(1 M) − TΔS°[Na+], where ΔH°(1 M) and ΔS°(1 M) can both be calculated from the nearest neighbor model with the use of the measured thermodynamic parameters (17–22,40,61).

Furthermore, from Eqs. 23 and 26, we obtain the following empirical expression for the melting temperature Tm:

|

(27) |

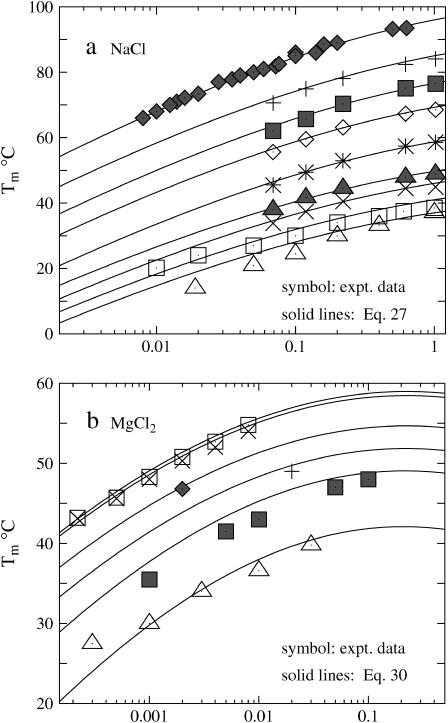

As shown in Fig. 9 a, the above expression for Tm agrees with the experimental results, even for very long DNA (Escherichia coli) (33).

FIGURE 9.

Comparisons between the empirical formulas (solid lines) for Tm (Eqs. 27 and 30) and experimental data (symbols) for (a) NaCl and (b) MgCl2 solutions. (a) The DNA sequences for NaCl solutions are (5′-3′): GGAATTCC (81), GCCAGTTAA (37), ATCGTCTGGA (82), CCATTGCTACC (35), ATCGTCTCGGTATAA (35), CCATCATTGTGTCTACCTCA (35), AATATCTCTCATGCGCCAAGCTACA (35), GTTATTCCGCAGT-CCGATGGCAGCAGGCTC (35), and E. coli (33) (from the bottom to top). (b) The sequences for MgCl2 solutions are (5′-3′): GCCAGTTAA (37), AGAAAGAGAAGA (84), TTTTTTTGTTTTTTT (38), TAATTTAAAATTTTTAAAAAA (88), TTTTTTTTTTATTAAAATTTATAAA (89), and AAAAAAAAAATAATTTTAAATATTT (89) (from the bottom to top). Tm(1 M Na+) is calculated from the nearest neighbor model with the thermodynamic parameters of SantaLucia (20) except for E. coli. For E. coli, Tm(1 M Na+) is taken as 96.5°C.

In the MgCl2 solution

Similarly, from Eqs. 3 and 5, we obtain the following expression for the thermodynamic parameters in MgCl2 solution:

|

(28) |

|

(29) |

|

(30) |

where Δg2 is a function associated to the electrostatic folding free energy per base stack, Δg2 is a function of helix length N and the Mg2+ ion concentration:

|

(31) |

|

(32) |

The above analytical expressions are valid for N  (see Fig. 8 b for the comparison with the TBI calculations). Fig. 9 b shows the comparison between the above formulas and the experimental data for Tm for a wide range of Mg2+ concentration and DNA length. We find good agreements between Eq. 30 and the available experimental data.

(see Fig. 8 b for the comparison with the TBI calculations). Fig. 9 b shows the comparison between the above formulas and the experimental data for Tm for a wide range of Mg2+ concentration and DNA length. We find good agreements between Eq. 30 and the available experimental data.

Nonadditivity for the helix stability

The analytical formulas for the thermodynamic parameters account for the chain length-dependence of the folding stability. The 1/N expansion clearly shows the saturation effect as 1/N → 0 for large helix length N (52).

The stability is additive if it can be computed as the sum of the stability of each base stack. Mathematically, the additivity corresponds to a linear-dependence of the folding free energy on the helix length (= N − 1 stacks), i.e., Δgz in Eqs. 23 and 28 (z = valence of the ion = 1 for Na+ and 2 for Mg2+) is N-independent or weakly dependent on N, which, according to Eqs. 24 and 31, occurs if the following condition is satisfied:

|

where az and bz are given by Eqs. 25 and 32 for z = 1 (Na+) and 2 (Mg2+), respectively.

The above additivity condition depends on the ion concentration. For example, bz/az is not very sensitive to the ion concentration at high salt region ( for NaCl and

for NaCl and  for MgCl2). But for lower ion concentration, the additivity condition becomes more sensitive to the ion concentration. bz/az and hence the required chain length N would increase rapidly in order for the additivity condition to be satisfied.

for MgCl2). But for lower ion concentration, the additivity condition becomes more sensitive to the ion concentration. bz/az and hence the required chain length N would increase rapidly in order for the additivity condition to be satisfied.

Na+ versus Mg2+

Previous experiments for a specific sequence have shown that the 1 M NaCl solution has effectively the equivalent ionic effect on the helix stability as the 10 mM MgCl2/150 mM NaCl mixed solution (36). Similar relation has also been experimentally found for RNA folding: 1 M NaCl has the similar effect as 10 mM MgCl2/50 mM NaCl mixed solution for stabilizing a ribosomal RNA secondary structure (90), and 1 M NaCl is similar to 10 mM MgCl2/100 mM NaCl mixed salt for a hammerhead ribozyme folding (91). With the TBI theory, which can treat the Mg2+ ions, we can now evaluate and compare the role of Na+ and Mg2+ ion in the stabilization of nucleic acid helix. Because the current form of the TBI theory does not treat the Na+/Mg2+ mixture solution, we examine the ds helix stability in 1 M NaCl and in 10 mM MgCl2 solution. We compare the melting temperatures Tm in these two different solutions (see Eqs. 27 and 30).

We choose thermodynamic parameters of each base stack in 1 M NaCl (ΔH°, ΔS°) = (−8.36 kcal/mol, −22.37 cal/mol/K), as determined from the average parameters over different sequences (22). So for a N-bp helix,  . Eqs. 27 and 30 predict that

. Eqs. 27 and 30 predict that  for N = 9. So the helix is only slightly less stable in 10 mM MgCl2 than in 1 M NaCl.

for N = 9. So the helix is only slightly less stable in 10 mM MgCl2 than in 1 M NaCl.

In addition, we find that the melting temperature difference ΔTm decreases as the helix length is increased and eventually becomes saturated for very long helix. Such length-dependence can be understood from the enthalpy-entropy competition in the ion-binding process. The ion-binding entropic penalty for [Mg2+] = 10 mM is much larger than that for [Na+] = 1 M. Therefore, entropically, Mg2+ binding is less favorable than Na+ binding. However, enthalpically, the binding of Mg2+, which carries higher charge and can cause more efficient charge neutralization, is more favorable than that of Na+. Therefore, the enthalpic effect becomes more important for a longer helix, which has stronger electric field near DNA surface. As a result, as the helix length is increased, Mg2+ would stabilize the helix more effectively than Na+, causing ΔTm to decrease.

CONCLUSIONS AND DISCUSSION

The tightly bound ion theory can explicitly account for the correlation and fluctuation of the bound ions (55). Based on the TBI theory, we investigate the thermal stability of DNA helix in Na+ and Mg2+ solutions for different helix lengths (5–13 bps) and different salt concentrations (1 mM to 1 M for NaCl and 0.1 mM to 1 M for MgCl2). The predicted folding free energy and melting temperature for the helix-coil transition agree with the available experimental data. The following is a brief summary for our major findings in this study.

For NaCl solution, both PB and the TBI theory can successfully predict the thermodynamics of helix-coil transition up to 1 M NaCl, as compared with experimental data.

For MgCl2, the TBI theory can predict the experimental data, whereas PB underestimates the helix stability and melting temperature due to the neglected correlation and fluctuation effects.

Helix is stabilized by ions. However, for high ion concentrations, the helix stability becomes saturated and further enhancement of the stability is small.

The electrostatic part of the helix-coil folding free energy appears only weakly temperature-dependent for both NaCl and MgCl2 solutions. Thus, the strong temperature-dependence of the total folding free energy mainly comes from the nonelectrostatic contribution.

The nearest neighbor model works well for high NaCl concentration (and long helix), in which case the electrostatic part of the folding free energy for each base stack is only weakly dependent on the helix length N.

Based on our calculated results, we obtain analytical formulas for the folding free energy and the melting temperature as functions of helix length and salt concentration. These empirical formulas account for the nonadditivity of the helix stability and are tested against extensive experimental results. These analytical expressions can be useful for practical use in predicting nucleic acid helix stability.

This work for the helix stability involves several simplified assumptions, as explained in the following. The stability calculation is based on the assumption about the separable electric and the nonelectric contributions. Moreover, the helix-coil transition is assumed to be two-state between the mean structures of dsDNA and ssDNA. However, ssDNA is a denatured structure that, depending on the sequence and ionic condition, can adopt an ensemble of different conformations. The uncertainty of the ssDNA structure may contribute to some of the theory-experiment differences.

In this form of the TBI theory, we do not treat: a), the mixed ion solutions, e.g., Na+/Mg2+ mixture, and b), the possible existence of the anions in the tightly bound region. The generalization of the current TBI framework to treat the mixed solution and the tightly bound anions is straightforward but technically challenging. Specifically, the multiple species (Na+/Mg2+ or cation/anion) of the tightly bound ions can result in: 1), the significantly larger number of the binding modes, and 2), the much more complicated interactions and the associated potential of mean force functions.

In the TBI theory, we neglect the possible dehydration effect (92) for the bound ions. We also neglect the binding of ions (including anions) to specific functional groups of nucleotides (93) in the tightly bound region. The site-specific binding of dehydrated cations can contribute significantly to the nucleic acid tertiary structure folding stability. For the simple helical structure studied here, however, the binding to specific sites and the associated dehydration may not play a dominant role in the folding stability. Nevertheless, this TBI theory may provide a framework for further inclusion of the dehydration effects and ion binding to specific sites. A possible approach would be to place ion(s) to the predetermined specific binding site(s), and to determine the tightly bound region with the existence of the prefixed site-bound ion(s). To account for the desolvation effect for the tightly bound ions, we need to include the desolvation free energy ΔGsol in the electrostatic free energy ΔGb for the tightly bound ions.

To compute the stability for more complex nucleotide folds, we must consider the conformational ensemble of the molecule, including the possible stable intermediate states. For the high resolution full-atomic structure, the TBI calculation, in particular, the potential of mean force calculation for the tightly bound ions, would be more time-consuming because of the atomic details involved. Moreover, for a compact three-dimensional structure, different parts of the chain (and the associated tightly bound region) are brought together through the long-range tertiary contacts. As a result, a), the pairwise potential of mean force used in the helix-coil calculation should be replaced by the multiion potential of mean force to account for the correlation between the spatially nearby tightly bound ions, and b), in this case, the division of the tightly bound region into the tightly bound cells centered around the phosphates can become ambiguous.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dirk Stigter and Gerald Manning for the stimulating communications on the development of the TBI theory.

This research was supported by National Institutes of Health/National Institute of General Medical Sciences through grant No. GM063732 (to S-J.C.) and by the Molecular Biology Program at the University of Missouri-Columbia.

APPENDIX A: STRUCTURAL MODELS FOR DSDNA AND SSDNA

We adopt B-DNA structure for dsDNA because B-form DNA is the most common and stable form over a wide range of salt conditions and sequences (16,94). The grooved primitive model is used instead of the all-atom DNA model (55,95); see Fig. 1 a. The model has been shown to be able to give detailed ion distribution that agrees well with the all-atomic simulations (95). In the grooved model, we represent a N-bp B-form DNA structure as two helical strands, each with N nucleotide units, around a central cylindrical rod of radius rcore = 3.9 Å. Two hard spheres are used to represent a nucleotide unit. A charged sphere with a point charge −e at the center is used to represent the phosphate group and an electrically neutral sphere to represent the rest of the atoms. The phosphate sphere is placed at the center of the phosphate group of the nucleotide and the neutral sphere lies between the phosphate sphere and the cylindrical rod. Both spheres have radius of r0 = 2.1 Å (95). For a canonical B-DNA, the phosphate charge positions (= the center of the charged sphere) ( ) are given by the following equations (96):

) are given by the following equations (96):  where s = 1, 2 denotes the two strands and i = 1, 2, …N denotes the nucleotides on each strand. The parameters (

where s = 1, 2 denotes the two strands and i = 1, 2, …N denotes the nucleotides on each strand. The parameters ( ) for the initial position are (0°, 0 Å) for the first strand and (154.4°, 0.78 Å) for the second strand, respectively.

) for the initial position are (0°, 0 Å) for the first strand and (154.4°, 0.78 Å) for the second strand, respectively.

The ssDNA structure is not as well-characterized as the dsDNA. The structure of ssDNA, which is an “unfolded” state of the dsDNA, can be dependent on the helix and the ionic condition (94,97–103). Previous experiments indicated that ssDNA (RNA) structure is neither a maximally stretched “rod” nor a completely random conformation. Instead, the ssDNA structure exhibits some single helical order due to self-stacking (94,97–103). This suggests that the single-strand structure can be modeled as an ordered helix (58,60). In this work, instead of considering the ensemble of all ssDNA conformations (104), we model ssDNA using a mean structure averaged over the previously measured ssDNA structures (32,58,60,100–102). We use the grooved primitive (55,95) model to describe the ssDNA structure; see Fig. 1 b. There are three structure parameters to be determined: radial coordinate of phosphates rp, twist angle per residue Δθ, and rise per basepair Δz. The experiments show that, compared with dsDNA, the single-stranded helices shrink (i.e., rp and Δz decrease) because of the absence of the interstrand electrostatic repulsion (94,97–99). Previous theoretical modeling on ssDNA structure suggests that the radial radius of phosphate charges (rp) is between 5 and 7 Å (32,58,60,100–102). Here, we use rp = 7 Å We also use Δz = 2.2Å and keep Δθ = 36°, which is the same as that of dsDNA. Thus, for ssDNA, the phosphate charge position (ρi, θi, zi) can be given by the following equations: ρi = 7 (Å); θi = i 36°; zi = i 2.2 (Å). As a control, we also perform calculations with the other two different sets of structure parameters for ssDNA: (Δθ, rp, Δz) = (36°, 7.5 Å, 1.8 Å) and (Δθ, rp, Δz) = (36°, 6.4 Å, 2.6 Å) and found negligible changes in the predicted results for both NaCl and MgCl2 solutions.

APPENDIX B: PARAMETER SETS AND NUMERICAL DETAILS

In this study, the ions are assumed to be hydrated (55). The radii of hydrated Na+ and Mg2+ ions are taken as 3.5 and 4.5 Å (105), respectively. In addition, the cation sizes can be changed (3, 3.5, and 4 Å for monovalent and 4, 4.5, and 5 Å for divalent ions) to investigate the cation size effects on the DNA stability.

In the computation with PB, the dielectric constant ε of DNA interior is set to be 2, and ε of solvent is set as the value of bulk water. At 25°C, the dielectric constant of water is ∼78. The dielectric constant of water decreases with the increase of temperature. We use the following empirical formula for the temperature-dependence of ε (86)

|

(33) |

where t is the temperature in Celsius.

Both the TBI model and the PB calculation require numerical solution of the nonlinear PB. We have developed a three-dimensional finite-difference algorithm to numerically solve nonlinear PB equation (55), by following the existed algorithms (44–51). A thin layer of thickness equal to one cation radius is added to the molecular surface to account for the excluded volume layer of cations (8,9,55). We use the three-step focusing process to obtain the detailed ion distribution near the molecules (45,55). The grid size of the first run depends on the salt concentration used. Generally, we keep it larger than six times of Debye length of salt solution to include all salt effects in solution. The resolution of the first run varies with the grid size to make the iterative process viable within a reasonable computational time (55). The grid sizes for the second run and the third run are kept at 102 and 51 Å, respectively, and the corresponding resolutions are 0.85 Å per grid and 0.425 Å per grid, respectively. Then the number of the grid points is 1213 for the second and third run. We use high resolution grid system near the DNA surface because the ions near the DNA surface make the most important electrostatic contribution to DNA stability. We have examined our results against different grid sizes, and the results are quite stable.

References

- 1.Tinoco, I., and C. Bustamante. 1999. How RNA folds. J. Mol. Biol. 293:271–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rook, M. S., D. K. Treiber, and J. R. Williamson. 1999. An optimal Mg2+ concentration for kinetic folding of the Tetrahymena ribozyme. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 96:12471–12476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Woodson, S. A. 2005. Metal ions and RNA folding: a highly charged topic with a dynamic future. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 9:104–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Draper, D. E., D. Grilley, and A. M. Soto. 2005. Ions and RNA folding. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 34:221–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sosnick, T. R., and T. Pan. 2003. RNA folding: models and perspectives. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 13:309–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Auffinger, P., L. Bielecki, and E. Westhof. 2004. Symmetric K+ and Mg2+ ion-binding sites in the 5S rRNA loop E inferred from molecular dynamics simulations. J. Mol. Biol. 335:555–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Auffinger, P., and E. Westhof. 2001. Water and ion binding around r(UpA)12 and d(TpA)12 oligomers: comparison with RNA and DNA (CpG)12 duplexes. J. Mol. Biol. 305:1057–1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Misra, V. K., and D. E. Draper. 2000. Mg2+ binding to tRNA revisited: the nonlinear Poisson-Boltzmann model. J. Mol. Biol. 299:813–825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Misra, V. K., and D. E. Draper. 2001. A thermodynamic framework for Mg2+ binding to RNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 98:12456–12461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heilman-Miller, S. L., D. Thirumalai, and S. A. Woodson. 2001. Role of counterion condensation in folding of the Tetrahymena ribozyme. I. Equilibrium stabilization by cations. J. Mol. Biol. 306:1157–1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heilman-Miller, S. L., J. Pan, D. Thirumalai, and S. A. Woodson. 2001. Role of counterion condensation in folding of the Tetrahymena ribozyme. II. Counterion-dependence of folding kinetics. J. Mol. Biol. 309:57–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Das, R., L. W. Kwok, I. S. Millett, Y. Bai, T. T. Mills, J. Jacob, G. S. Maskel, S. Seifert, S. G. J. Mochrie, P. Thiyagarajan, S. Doniach, L. Pollack, et al. 2003. The fastest global events in RNA folding: electrostatic relaxation and tertiary collapse of the Tetrahymena ribozyme. J. Mol. Biol. 332:311–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koculi, E., N. K. Lee, D. Thirumalai, and S. A. Woodson. 2004. Folding of the Tetrahymena ribozyme by polyamines: importance of counterion valence and size. J. Mol. Biol. 341:27–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fang, X., T. Pan, and T. R. Sosnick. 1999. A thermodynamic framework and cooperativity in the tertiary folding of a Mg2+-dependent ribozyme. Biochemistry. 38:16840–16846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bloomfield, V. A. 1997. DNA condensation by multivalent cations. Biopolymers. 44:269–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bloomfield, V. A., D. M. Crothers, and I. Tinoco Jr. 2000. Nucleic Acids: Structure, Properties and Functions. University Science Books, Sausalito, CA.

- 17.Freier, S. M., R. Kierzek, J. A. Jaeger, N. Sugimoto, M. H. Caruthers, T. Neilson, and D. H. Turner. 1986. Improved free-energy parameters for predictions of RNA duplex stability. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 83:9373–9377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Breslauer, K. J., R. Frank, H. Blocker, and L. A. Marky. 1986. Predicting DNA duplex stability from the base sequence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 83:3746–3750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Turner, D. H., and N. Sugimoto. 1988. RNA structure prediction. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biophys. Chem. 17:167–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.SantaLucia, J., H. T. Allawi, and P. A. Seneviratne. 1996. Improved nearest-neighbor parameters for predicting DNA duplex stability. Biochemistry. 35:3555–3562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sugimoto, N., S. I. Nakano, M. Yoneyama, and K. I. Honda. 1996. Improved thermodynamic parameters and helix initiation factor to predict stability of DNA duplexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 24:4501–4505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.SantaLucia, J., Jr. 1998. A unified view of polymer, dumbbell, and oligonucleotide DNA nearest-neighbor thermodynamics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 95:1460–1465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Owczarzy, R., P. M. Callone, F. J. Gallo, T. M. Paner, M. J. Lane, and A. S. Benight. 1997. Predicting sequence-dependent melting stability of short duplex DNA oligomers. Biopolymers. 44:217–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]