Abstract

DNA binding of Klenow polymerase has been characterized with respect to temperature to delineate the thermodynamic driving forces involved in the interaction of this polymerase with primed-template DNA. The temperature dependence of the binding affinity exhibits distinct curvature, with tightest binding at 25–30°C. Nonlinear temperature dependence indicates Klenow binds different primed-template constructs with large heat capacity (ΔCp) values (−870 to −1220 cal/mole K) and thus exhibits large temperature dependent changes in enthalpy and entropy. Binding is entropy driven at lower temperatures and enthalpy driven at physiological temperatures. Large negative ΔCp values have been proposed to be a ‘signature’ of site-specific DNA binding, but type I DNA polymerases do not exhibit significant DNA sequence specificity. We suggest that the binding of Klenow to a specific DNA structure, the primed-template junction, results in a correlated thermodynamic profile that mirrors what is commonly seen for DNA sequence-specific binding proteins. Klenow joins a small number of other DNA-sequence independent DNA binding proteins which exhibit unexpectedly large negative ΔCp values. Spectroscopic measurements show small conformational rearrangements of both the DNA and Klenow upon binding, and small angle x-ray scattering shows a global induced fit conformational compaction of the protein upon binding. Calculations from both crystal structure and solution structural data indicate that Klenow DNA binding is an exception to the often observed correlation between ΔCp and changes in accessible surface area. In the case of Klenow, surface area burial can account for only about half of the ΔCp of binding.

INTRODUCTION

Escherichia coli DNA polymerase I (Pol I) was the first DNA polymerase discovered and isolated (1,2) and remains the central model system for studies aimed at understanding DNA replication in general. Full length Pol I is a single polypeptide chain with three separate structural/functional domains: a polymerization domain, a 3′ exonuclease (or proofreading) domain, and a 5′ nuclease domain. Removal of the 5′ nuclease domain from the protein by limited protease digestion (3) or by cloning (4) yields the Klenow or “large fragment” of the protein, which is a fully functional polymerase on its own. The tertiary architecture of Klenow and other DNA polymerases is often visually conceptualized as a partly open right hand, with a palm, fingers, and a thumb. The palm contains the polymerase fold, which is conserved across the polymerase family and contains the catalytic residues (5,6). No crystal structure of Klenow with DNA bound in the polymerization mode has yet been determined, so some commonly accepted structural features of DNA-bound Klenow are actually extrapolations from other polymerase structures. Biochemical, functional, and mutational studies have shown that the fingers of Klenow bind the single-stranded portion of primed-template DNA, whereas the thumb binds the duplex part of primed-template DNA (7–12). Such functional mapping of the structural topology of Klenow is largely consistent with the structural data on other Pol I type DNA polymerases for which polymerization-mode, DNA-bound cocrystals do exist (6,13–17). The detailed mechanistic differences among different Pol I type DNA polymerases are only just beginning to be elucidated.

In this study we have characterized the temperature dependence of primed-template DNA binding by Klenow polymerase to understand the thermodynamic driving forces responsible for DNA binding by this polymerase. We find that when compared to other DNA binding proteins, Klenow thermodynamically behaves more like a DNA sequence-specific binding protein than a nonsequence-specific binding protein. Klenow DNA binding is associated with a significant negative ΔCp (heat capacity change), which is manifested as a nonlinear temperature dependence of the free energy of binding and as strong enthalpy-entropy compensation over the temperature range of 5–37°C. Large negative ΔCp has been called a signature of DNA site-specific binding (18). In addition, ΔCp has most often been correlated at the molecular level with the change in the accessible surface area of the protein and DNA upon complex formation (19,20). These two separate correlations are often considered to be two sides of the same coin, but some investigators have demonstrated their independent nature (18). Our study finds that for Klenow-DNA interactions, these two correlations are not coincident. Understanding the usefulness of ΔCp as an index for either intermolecular complementarity, interfacial molecular properties, or both continues to be an active area of inquiry.

DNA polymerases are generally considered essentially nonsequence-specific DNA binding proteins, although they do exhibit a limited amount of DNA sequence dependent variation in binding affinity (21–23). However, the span between the tightest and weakest binding sequences for a polymerase or other “nonspecific” DNA binding protein (e.g., E. coli SSB (24)) is generally on the order of ± one order of magnitude: a range that is 103–106-fold smaller than the span between sequence-specific and nonspecific binding for a transcriptional regulator or a restriction endonuclease (18).

In contrast, Klenow binding is significantly affected by DNA structure. Recent studies have shown that the binding affinity of Klenow fragment to a primed-template DNA is significantly reduced by decreasing the number of bases in the single-stranded template overhang (10). Similar results have been obtained for DNA binding by T4 DNA polymerase (25). Specific interactions between the polymerase and the single-stranded portion of the substrate DNA thus clearly contribute significantly to the overall stability of the complex. Additionally, in this study we assayed for sequence-specific effects in this region of the DNA, with the results showing that the binding affinities for the different DNA sequences tested are nearly identical. This further supports the view that the binding of Klenow to DNA is dominated more by the structure of the DNA (a primed-template junction) than by the sequence.

In this study, we show that like sequence-specific DNA binding proteins, high affinity primed-template structure-specific DNA binding of Klenow is characterized by a nonlinear temperature dependence, and thus a large negative ΔCp of binding. A similar temperature dependence study of DNA binding by the large fragment domain and the full length Pol I from Thermus aquaticus (Taq polymerase) yielded a similar thermodynamic profile (26). Thus this study also demonstrates that such a thermodynamic profile is not unique to Taq polymerase but may be a universal characteristic of the binding of Pol I-type polymerases to primed-template DNA, implying that the underlying thermodynamics of binding of pt-DNA to thermophilic and mesophilic polymerases do not fundamentally differ. We also extend the former studies of Taq/Klentaq by augmenting this study of Klenow with additional DNA constructs and with small angle x-ray scattering (SAXS) measurements. SAXS allows us to account for additional binding induced surface area changes not observed in the crystal structure, and thus to demonstrate that unlike the case for many DNA sequence-specific binding proteins, the moderately large negative ΔCp of DNA binding by Klenow is not directly correlated with the burial of accessible surface area.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

All binding studies were performed with the D424A mutant of Klenow polymerase known as Klenow exo minus (KF exo−) (27). This is the predominant variant of Klenow used in the majority of functional studies of Klenow over the past decade. The KF exo− expression clone and host were a gift from Catherine Joyce (Yale University), and the protein was expressed and purified as described previously (28,29). Scheme 1 shows the different DNA primer-template constructs used in the binding studies. The majority of experiments, including the temperature dependence of binding and the solution structural studies, were carried out with the mixed sequence 13/20-mer. The 13/20-mer primer template set used is the same as one used for kinetic studies of Klenow DNA binding by Benkovic and associates (21). The longer primer-template pair (63/70-mer) was designed for use at higher temperatures (26). The 63/70-mer contains the 13/20-mer sequence at its primer-template junction, with added random sequence selected from the same region of the M13 bacteriophage sequence. DNA oligonucleotides were purchased from IDT (Integrated DNA Technologies, Coralville, IA). The UV/Vis measured Tm values of the DNA constructs under DNA binding conditions are 68°C for the 13/20-mer and >85°C for the 63/70-mer. Fluorescently labeled DNA was labeled at the 5′ end of the primer strand with rhodamine-X (ROX) and was purchased directly from IDT.

SCHEME 1.

Primer template DNA constructs utilized

| 13/20-mer: | 5′TCGCAGCCGTCCA3′ | |

| 3′AGCGTCGGCAGGTTCCCAAA5′ | ||

| 13/20polyA: | 5′TCGCAGCCGTCCA3′ | |

| 3′AGCGTCGGCAGGTAAAAAAA5′ | ||

| 13/20polyT: | 5′TCGCAGCCGTCCA3′ | |

| 3′AGCGTCGGCAGGTTTTTTTT5′ | ||

| 13/20polyC: | 5′TCGCAGCCGTCCA3′ | |

| 3′AGCGTCGGCAGGTCCCCCCC5′ | ||

| 63/70-mer: | ||

| 5′TACGCAGCGTACATGCTCGTGACTGGGATAACCGTGCCGTTTGCCGACTTTCGCAGCCGTCCA3′ | ||

| 3′ATGCGTCGCATGTACGAGCACTGACCCTATTGGCACGGCAAACGGCTGAAAGCGTCGGCAGGTTCCCAAA5′ | ||

Equilibrium DNA binding using fluorescence anisotropy

Direct equilibrium titrations were performed over a temperature range of 5–37°C using a fluorescence anisotropy binding assay, as described previously (26,28). The primer-template DNA used (Scheme 1) was labeled at the 5′ end of the primer strand with ROX. For each titration, increasing amounts of Klenow polymerase were titrated into 1 nM labeled DNA until saturation. For titrations at temperatures lower than room temperature, nitrogen was flowed through the fluorometer sample chamber to prevent condensation on the cuvette. It was shown previously that the polymerase binds this DNA with 1:1 stoichiometry (28). The binding isotherms are analyzed with a single site binding equation as described previously (26,28) to obtain the Kd (dissociation constant) for binding. Unless noted otherwise, titrations were performed in a buffer containing 10 mM Tris, 300 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, at pH 7.9. Since the pKa of Tris shows a strong temperature dependence, the pH of the buffers were adjusted at the respective temperatures for each experiment. pH is adjusted by mixing appropriate volumes of Tris-HCl and Tris base containing identical salt concentrations.

The temperature dependence of the free energy of DNA binding was analyzed using an integrated Gibbs-Helmholtz equation with a temperature independent ΔCp as described previously (26):

|

(1) |

where ΔG(T) is the free energy at each temperature, T is the temperature in Kelvin, ΔCp is the heat capacity, and ΔHrefT and ΔSrefT are the fitted van 't Hoff enthalpy and entropy values at any chosen reference temperature TrefT.

The dependence of equilibrium binding on the DNA sequence within the single stranded region of the primer-template was examined using the fluorescence anisotropy assay, with the 13/20polyA, 13/20polyT, and 13/20polyC primer-template constructs shown in Scheme 1. For each of these titrations, the 5′ end of the primer strand was labeled with ROX. All DNA sequence dependence titrations were performed at 25°C in 10 mM Tris, 300 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, pH 7.9.

Isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC)

Calorimetric titrations were performed over a temperature range of 10–37°C with unlabeled 13/20-mer and 63/70-mer DNA in a MicroCal (Northhampton, MA) VP-ITC calorimeter. The buffer was identical to the one used for fluorescence anisotropy binding titrations. DNA concentrations for the titrations ranged from 1.0 to 2.5 μM. The protein concentrations used for the titrations were between 30 and 75 μM, such that the protein concentration in the titrating syringe was 30 times greater than the DNA concentration in the sample cell for all titrations. Each titration consisted of an initial 2 μl injection (not used for data analysis) followed by 31 subsequent 7 μl injections. The heat of dilution of the protein was obtained by titrating protein into the buffer. The actual heat of the reaction was determined after subtracting the heat of dilution of the protein. ITC binding curves were analyzed using the single site binding equation in the MicroCal Origin software package.

Calorimetric titrations were also performed with 63/70-mer DNA at 30°C in buffers with proton ionization enthalpies (ΔHion) different from Tris (ΔHion = 11.34 kcal/mole). The DNA concentrations ranged from 2.1 to 2.5 μM. The additional buffers used were 10 mM phosphate, 10 mM borate, 10 mM HEPES, 10 mM MOPS, and 10 mM imidazole at identical salt concentrations and pH values as the Tris based buffer. The enthalpies of binding in these buffers were analyzed as a function of ΔHion of the buffer using the following linear relation to determine the effect of buffer ionization on the binding enthalpy:

|

(2) |

where ΔHcal is the measured calorimetric binding enthalpy, n is the number of protons taken up or released by the buffer upon binding, ΔHion is the proton ionization enthalpy of the buffer, and ΔHbinding is the binding enthalpy in the absence of any heat from buffer proton ionization (30–32).

Circular dichroism measurements

Circular dichroism (CD) spectra were measured at room temperature (22°C) in an Aviv (Lakewood, NJ) Model 202 CD spectrophotometer. A dual compartment mixing cuvette was used to record the spectra of protein + DNA before and after mixing. One compartment was filled with 3 μM DNA, the other with 3 μM Klenow DNA polymerase. Thermal denaturation in the DNA binding buffer, monitored by CD, was conducted as described previously (33).

Small angle x-ray scattering

SAXS experiments were conducted on synchrotron beam line 1–4 at the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Research Laboratory. Data were collected at a wavelength of 1.488 Å and a sample to detector distance of 0.38 m (which is optimal for this beamline). The beam flux was 2 × 1010 photons/s. The sample cell was aluminum and consisted of a 200 μl coin-shaped sample chamber. The path length through the sample was 1.4 mm, and the sample chamber was bounded on both sides by circular Kapton windows. SAXS measurements were conducted in the same buffer as used for the binding measurements. Scattering was monitored in 15 min exposure times for each measurement. Repeated measurements of the same sample yielded the same results, indicating that no significant radiation damage occurred during the experiments. The polymerase concentration was 5 mg/ml, and an equimolar concentration of 13/20-mer DNA was added to form the complex. The scattering data were collected and normalized for dark counts and scattering intensity, and the buffer background scattering was subtracted using the resident analysis programs at the beamline.

SAXS data were analyzed in two ways: 1), using Guinier plots (34,35), where Rg values were determined from the linear portions of the plots; and 2), using the program GNOM, where an indirect Fourier transform of the experimental scattering curve is implemented to derive the P(r) distance distribution function. The Rg is then calculated from the P(r) function (36). Program default values are used for all input parameters except for Dmax, which is altered to obtain the best fit (36). Previous studies have shown that the determined Rg values do not show any protein concentration dependence within error (37).

RESULTS

Temperature dependence of equilibrium DNA binding by Klenow polymerase

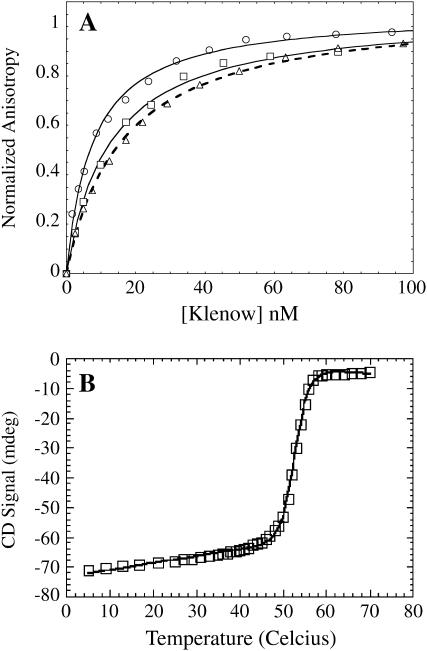

Equilibrium binding of Klenow to 13/20-mer and 63/70-mer primed-template DNA constructs was measured over the temperature range 5–37°C using both fluorescence anisotropy and ITC. Fig. 1 A shows representative fluorescence anisotropy titration curves at three temperatures for the 13/20-mer. With increasing temperature the binding affinity (1/Kd) increases up until ∼25°C, above which binding gets weaker. The highest temperature used in this study was 37°C, to insure that results were not complicated by the onset of protein thermal denaturation. Klenow denatures at ∼45°C at pH 7.9 in the absence of KCl (33). Added salt increases Klenow's denaturation temperature. A thermal denaturation curve for Klenow polymerase in the DNA binding buffer used in this study is shown in Fig. 1 B where it can be seen that 37°C is on the native state baseline before the unfolding transition.

FIGURE 1.

(A) Direct equilibrium titrations of the binding of Klenow DNA polymerase to fluorescently labeled 13/20-mer DNA performed at 5°C (□), 25°C (○), and 37°C (▵). The binding affinity first increases with increasing temperature up until ∼25°C and then decreases with further increase in temperature. (B) Thermal denaturation of Klenow polymerase in DNA binding buffer, monitored by CD. Shown is the CD signal at 221 nm with respect to temperature. The Tm for Klenow in this buffer is 52.7°C ± 0.1°C.

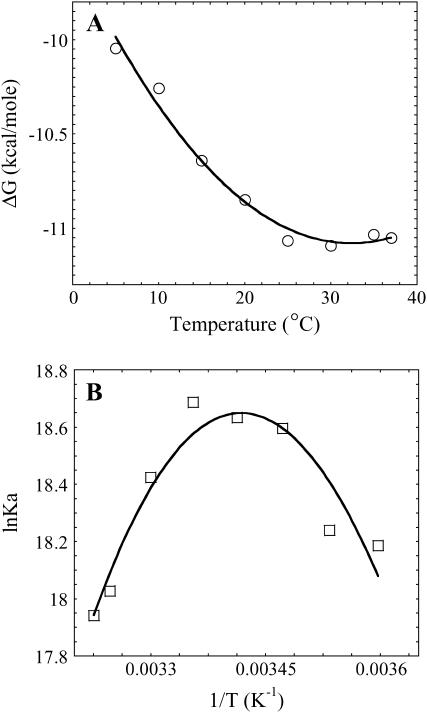

The temperature dependence of the free energy of binding (Fig. 2 A) shows a nonlinear behavior with the most favorable free energy of binding at ∼30°C. This nonlinearity of the temperature dependence of binding is even more obvious as a van 't Hoff plot (Fig. 2 B). These data indicate that the binding enthalpy (ΔH) is temperature dependent and that there is an associated ΔCp upon binding of Klenow to DNA. In the absence of a heat capacity change (i.e., ΔCp = 0), the temperature dependence of binding as depicted on both the Gibbs-Helmholtz and van 't Hoff plots would be linear. To obtain quantitative values for the energetic parameters involved in DNA binding, the free energy data were analyzed with an integrated Gibbs-Helmholtz (or van 't Hoff) equation, as depicted by the fitted lines in Fig. 2. The values of ΔHvH, TΔSvH, and ΔCpvH are summarized in Table 1 and ΔHvH and TΔSvH are illustrated in Fig. 3. The parallel large magnitude changes in ΔH and TΔS with temperature, commonly denoted “enthalpy-entropy compensation”, results in/from the comparatively minimal change of ΔG with temperature (ΔG only changes by up to ± a few kcal/mole with respect to temperature for most protein-DNA interactions (18,19)). Binding measurements performed with the longer piece of DNA (63/70-mer) produced corroborative conclusions, although the experimental and fitted error envelopes were larger with the longer DNA (Table 1). The thermodynamic profile for Klenow binding shown in Fig. 3 is a profile generally considered characteristic of site-specific protein-DNA binding (18,19).

FIGURE 2.

(A) Temperature dependence of the free energy (ΔG) of binding of Klenow polymerase to 13/20-mer DNA. The line is a fit to the Gibbs-Helmholtz equation (Eq. 1), which yields the enthalpy (ΔHvH) and entropy (ΔSvH) at different temperatures for the binding reaction, and the heat capacity change (ΔCp). Measured and fit values for the different thermodynamic parameters are given in Table 1. Error bars on the measured values are smaller than the symbols. (B) The temperature dependence of the Kd for binding of Klenow polymerase to 13/20-mer DNA graphed as a van 't Hoff plot and fit to the integrated form of the van 't Hoff equation. The data are the same as those in panel A.

TABLE 1.

Thermodynamic parameters for DNA binding of Klenow DNA polymerase to primed-template DNA

| Temp (°C) | Kd (nM) | ΔG† (kcal/mol) | ΔH (kcal/mol) | TΔS (kcal/mol) | ΔCp (cal/mol K) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 13/20-mer DNA* | |||||

| 5 | 12.6 ± 0.5 | −10.05 | +12.6 ± 2.2 | +22.6 ± 2.2 | |

| 10 | 14.1 ± 0.7 | −10.17 | +8.3 ± 1.6 | +18.7 ± 1.6 | |

| 15 | 8.4 ± 0.3 | −10.64 | +4.0 ± 1.0 | +14.6 ± 1.0 | −870 ± 130 |

| 20 | 8.1 ± 0.3 | −10.85 | −0.4 ± 0.6 | +10.5 ± 0.6 | |

| 25 | 7.7 ± 0.3 | −11.06 | −4.7 ± 0.8 | +6.3 ± 0.8 | |

| 30 | 10.0 ± 0.3 | −11.09 | −9.0 ± 1.3 | +2.1 ± 1.3 | |

| 35 | 14.8 ± 0.4 | −11.03 | −13.3 ± 1.9 | −2.3 ± 1.9 | |

| 37 | 16.2 ± 0.4 | −11.05 | −15.1 ± 2.2 | −4.0 ± 2.2 | |

| 63/70-mer DNA* | |||||

| Temp (°C) | Kd (nM) | ΔG† (kcal/mol) | ΔH (kcal/mol) | TΔS (kcal/mol) | ΔCp (cal/mol K) |

| 5 | 38.4 ± 1.3 | −9.43 | +16.6 ± 2.9 | +26.0 ± 2.9 | |

| 10 | 21.4 ± 3.1 | −9.93 | +11.7 ± 1.6 | +21.6 ± 1.6 | |

| 15 | 18.2 ± 0.5 | −10.20 | +6.9 ± 0.8 | +17.1 ± 0.8 | −967 ± 284 |

| 20 | 16.0 ± 0.5 | −10.45 | +2.1 ± 1.7 | +12.5 ± 1.7 | |

| 25 | 15.1 ± 0.4 | −10.66 | −2.7 ± 2.9 | +7.9 ± 3.0 | |

Kd and ΔG values are the experimental values determined from titrations at each temperature.

Propagated errors on ΔG are all ±0.02kcal/mole, except at 10°C, where the error is ±0.03kcal/mole for 13/20-mer DNA and ±0.08kcal/mole for 63/70-mer DNA. The other parameters (ΔH, ΔS, and ΔCp) are calculated from the fit to the Gibbs-Helmholtz equation. Errors from the fit are shown.

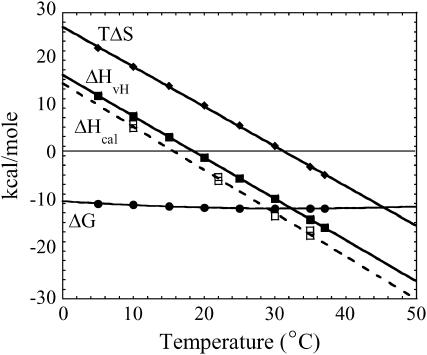

FIGURE 3.

Plots showing the changes in the thermodynamic parameters (ΔG, ΔHvH, ΔHcal, and TΔSvH) for binding of Klenow polymerase to 13/20-mer DNA as a function of temperature. Circles show ΔG values (same data as in Fig. 2, plotted here on a different scale), diamonds show TΔSvH values, and solid squares show ΔHvH values. The open squares (dashed line) show calorimetric ΔH values determined independently. ΔHcal values and error envelopes are reported in Table 2.

Temperature dependence of Klenow binding monitored by isothermal titration calorimetry

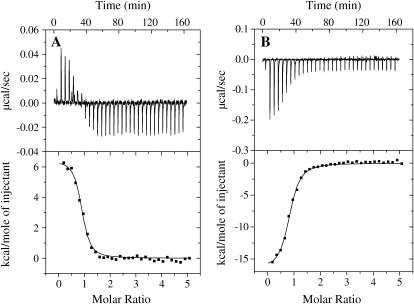

The enthalpies of DNA binding of Klenow to 13/20-mer and 63/70-mer DNA were also measured directly using ITC. Titrations were performed from 10–37°C under stoichiometric binding conditions, and Klenow was titrated into DNA. Fig. 4 shows representative titrations at low and high temperatures along with the fits to a single-site binding isotherm. The enthalpies of binding (ΔHcal) obtained from such fits are plotted as a function of temperature to directly obtain the calorimetric heat capacity change for the binding process (∂ΔHcal/∂T = ΔCpcal). The calorimetric data are shown in Fig. 3 for the 13/20-mer DNA and in Fig. 5 B for the 63/70-mer DNA. Fig. 3 shows that the ΔCpvH and ΔCpcal for binding of Klenow to 13/20-mer DNA are almost identical, which is an important cross-check of the Gibbs-Helmholtz analysis of the equilibrium binding data (38,39).

FIGURE 4.

ITC data for binding of Klenow to unlabeled 13/20-mer DNA at 10°C (A) and 35°C (B). The top portion of each panel shows the raw titration data, and the bottom portions show the integrated heats fit to single site binding isotherms. Binding is endothermic at 10°C and exothermic at 35°C.

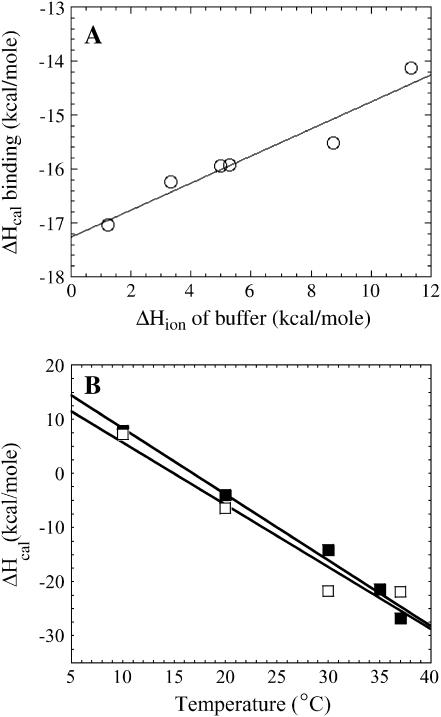

FIGURE 5.

(A) Calorimetric ΔH values for Klenow-DNA binding at 30οC in buffers with different ionization enthalpies. Measurements were made in phosphate (ΔHion = 1.22 kcal/mole), borate (ΔHion = 3.31 kcal/mole), HEPES (ΔHion = 5.0 kcal/mole), MOPS (ΔHion = 5.3 kcal/mole), imidazole (ΔHion = 8.75 kcal/mole), and Tris (ΔHion = 11.4 kcal/mole) under identical salt concentrations and pH. (B) Temperature dependences of the calorimetric ΔH of Klenow binding to 63/70-mer DNA in the presence and absence of MgCl2. The ΔCp values, obtained from the slopes, are nearly identical (ΔCp with Mg+2 = −1.22 kcal/mole K; ΔCp without Mg+2 = −1.15 kcal/mole K), indicating the ΔCp of binding is not magnesium dependent. In both plots, error bars on the measured values are ≤0.6 kcal/mole and are smaller than the plot symbols.

A more negative ΔCpcal is observed for binding to 63/70-mer DNA (Table 2), leading to more favorable ΔH values for the longer DNA in the physiological temperature range. The increases in magnitude of both ΔCp and ΔH with the longer DNA suggest that Klenow interacts with some portion of the additional DNA in the longer construct, although the exact nature of that interaction is presently unknown. The 63/70-mer DNA is completely duplex at the highest DNA binding temperature (37°C, data not shown), and thus there are no contributions to the overall ΔCp of DNA binding due to duplex reformation at higher temperatures. A sloped, but linear duplex baseline for the 13/20-mer, prior to a clear transition region, makes it difficult to exactly estimate its degree of dissociation at 37°C (data not shown). The sloped baseline may not be indicative of any duplex dissociation. Conversely, assuming all of the baseline drift reflects duplex dissociation yields an upper limit of 10% dissociation for the shorter DNA at the 37°C. However, since DNA duplex formation would contribute by increasing the magnitude of the negative heat capacity change, the measured ΔCp differences between the long and short DNA constructs cannot be accounted for in this way.

TABLE 2.

Calorimetric ΔH and ΔCp values for Klenow DNA binding

| 13/20-mer temperature* (°C) | ΔHcal (kcal/mole) | ΔCpcal (cal/mol K) | 63/70-mer temperature (°C) | ΔHcal (kcal/mole) | ΔCpcal (cal/mol K) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | +5.8 ± 0.2 | 10 | +7.9 ± 0.6 | ||

| 10 | +6.6 ± 0.2 | −910 ± 20 | 20 | −4.0 ± 0.1 | −1220 ± 80 |

| 22 | −4.4 ± 0.1 | 30 | −14.1 ± 0.4 | ||

| 22 | −5.3 ± 0.2 | 35 | −21.4 ± 1.1 | ||

| 30 | −12.7 ± 0.2 | 37 | −26.7 ± 1.0 | ||

| 35 | −15.7 ± 0.5 | ||||

| 35 | −16.7 ± 0.3 |

Each ΔHcal value represents a single experiment at the temperature indicated. Errors are from the fit of a single site equation to the calorimetric data. Errors on ΔCp are from linear fits of ΔHcal versus temperature.

The calorimetric parameters (ΔHcal and ΔCpcal) for both the 13/20-mer and 63/70-mer DNA are summarized in Table 2. The temperatures TH (where ΔH is 0) and TS (where ΔS is 0) are ∼20°C and 32°C, respectively, for 13/20-mer DNA binding by Klenow. The TH represents the temperature where the Kd is at its minimum, and TS represents the temperature where the ΔG is the most favorable.

Protonation/deprotonation coupled to DNA binding by Klenow

The detection and measurement of DNA binding linked protonation/deprotonation effects can be accomplished by performing parallel calorimetric titrations in buffers with different ionization enthalpies (30). DNA binding titrations were thus performed in phosphate (ΔHion = +1.22 kcal/mole), borate (ΔHion = +3.31 kcal/mole), HEPES (ΔHion = +5.0 kcal/mole), MOPS (ΔHion = +5.3 kcal/mole), imidazole (ΔHion = +8.75 kcal/mole), and Tris (ΔHion= +11.4 kcal/mole) (31,32). Titrations were performed at 30°C with 63/70-mer DNA at the same salt concentration and pH for all buffers. If protons are taken up or released upon formation of the Klenow-DNA complex, calorimetric measurements should reflect an additional heat effect due to the linked protonation or deprotonation of the buffer. Fig. 5 A shows the dependence of ΔHcal as a function of ΔHion of the buffer. The slope of this plot yields the number of protons taken up or released upon complex formation, and the y-intercept gives the enthalpy of binding in absence of contributions from the buffer ionization (30). Thus, whereas the directly measured ΔHcal in Tris buffer at this temperature is −14.1 kcal/mole, the extrapolation of ΔHcal to zero ΔHion reports a ΔHbinding of −17.3 kcal/mole, indicating that +3.2 kcal/mole of the measured enthalpy at 30°C in Tris is due to a linked buffer ionization effect. Because the thermodynamics of 13/20-mer and 63/70-mer binding are a little different, the linked protonation/deprotonation effect for binding to the 13/20 may be different. Linked buffer protonation/deprotonation heats are one source of the commonly observed discrepancies between calorimetric and van 't Hoff enthalpies (29,30), such as those observed in these data (Tables 1 and 2). However, it is notable here that whereas the ΔHcal and ΔHvH values differ somewhat for the binding of Klenow to DNA, the ΔCp values determined for binding to the 13/20-mer and 63/70-mer DNAs by calorimetric and van 't Hoff analysis are quite similar (Tables 1 and 2).

The slope of plot 5A is +0.25, indicating that there is a small net proton uptake by the complex when Klenow polymerase binds 63/70-mer DNA (30–32). The magnitude of this measured linked proton uptake will be pH dependent (30), so this linkage indicates that at least one ionizable group becomes more protonated upon complex formation. This value of 0.25 is a thermodynamic average net change in protonation and could reflect either titration of one specific group or the net difference for a number of simultaneous linked protonation/deprotonation events.

We also assayed for the possible presence of a linked magnesium ion effect on the measured binding enthalpy for the interaction of Klenow and primed template DNA. Fig. 5 B shows temperature dependent measurements of the ΔHcal for binding of Klenow to 63/70-mer DNA in the presence and absence of MgCl2. Klenow is known to require Mg+2 for catalytic activity but not for DNA binding activity (28). The data in Fig. 5 B indicate that added magnesium does not significantly alter the ΔCp of binding for Klenow.

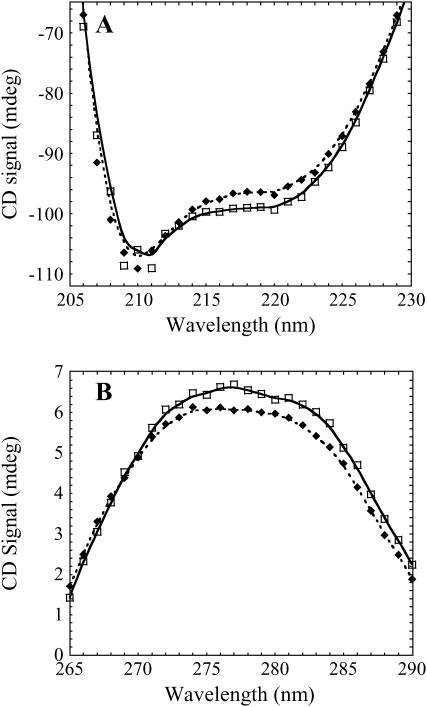

CD and SAXS measurements of conformational changes in the DNA and protein in solution

To examine the conformational changes of the protein and the DNA upon association in solution, we measured both the CD spectra and the SAXS properties of the free protein and DNA, and of the protein-DNA complex. The portions of the CD spectrum corresponding predominantly to signal from the protein (200–220 nm) and from the DNA (∼260–290 nm) are shown in Fig. 6 and indicate that there are structural rearrangements upon complex formation that are detectable by CD. Spectra obtained at room temperature (22°C) and at higher temperatures (37°C) were very similar (data not shown). The use of a dual compartment mixing cuvette helps ensure that the minor spectral changes observed are real.

FIGURE 6.

CD spectra for the Klenow-DNA complex versus free Klenow + free 63/70-mer DNA at 22°C. The spectral region from 206 to 228 nm corresponds to signal primarily from the protein (A), and the region from 265 to 290 nm corresponds to signal from the DNA (B). Protein + DNA were placed in separate sides of a two compartment mixing cuvette, and spectra were obtained before and after mixing. Both the protein and the DNA show slight conformational rearrangements upon complex formation. In both plots, the spectrum of the protein-DNA complex is shown using solid diamonds, and the spectrum of the unmixed free protein + free DNA is shown using open squares.

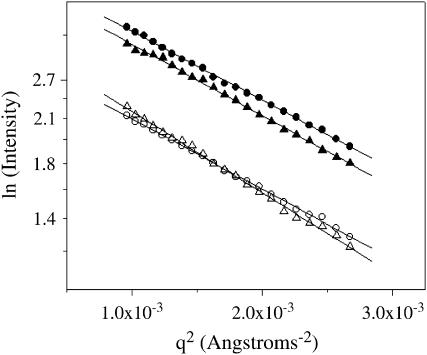

SAXS experiments were also performed at both 22°C and 37°C to obtain a more quantitative measure of the conformational changes of the protein upon DNA binding. A significant global conformational change of Klenow upon DNA binding should be manifested by a change in the radius of gyration (Rg) of the protein. Because the scattering intensity in SAXS is extremely dependent on the size of the scattering particle (intensity is proportional to  (34,35)), the 13/20-mer DNA on its own is effectively invisible relative to the protein in these experiments. The Rg values for apo and DNA -bound Klenow were determined using both linear (34,35) and nonlinear (36) analyses of the SAXS data. Guinier plots at 23°C and 37°C are shown in Fig. 7, and Rg values are given in Table 3. The increased intensity (upward shift of the Guinier lines) upon complex formation at both temperatures is likely due to the increased electron density of the protein-DNA complex relative to the free protein. Rg values are calculated from the slopes of these plots, as described in Materials and Methods. The data at both temperatures indicate that Klenow compacts slightly upon DNA binding, consistent with an induced fit model for DNA binding. The relative compaction appears larger at 37°C than at 23°C, but the relative error of the measurements is also greater at 37°C. The measured Rg differences appear quite small, but SAXS methods are sufficiently precise to support their reliability. Direct comparison of any individual pair of apo versus complex scattering curves strongly demonstrates that DNA binding results in compaction. The data do not, however, clarify whether such compaction is temperature variable.

(34,35)), the 13/20-mer DNA on its own is effectively invisible relative to the protein in these experiments. The Rg values for apo and DNA -bound Klenow were determined using both linear (34,35) and nonlinear (36) analyses of the SAXS data. Guinier plots at 23°C and 37°C are shown in Fig. 7, and Rg values are given in Table 3. The increased intensity (upward shift of the Guinier lines) upon complex formation at both temperatures is likely due to the increased electron density of the protein-DNA complex relative to the free protein. Rg values are calculated from the slopes of these plots, as described in Materials and Methods. The data at both temperatures indicate that Klenow compacts slightly upon DNA binding, consistent with an induced fit model for DNA binding. The relative compaction appears larger at 37°C than at 23°C, but the relative error of the measurements is also greater at 37°C. The measured Rg differences appear quite small, but SAXS methods are sufficiently precise to support their reliability. Direct comparison of any individual pair of apo versus complex scattering curves strongly demonstrates that DNA binding results in compaction. The data do not, however, clarify whether such compaction is temperature variable.

FIGURE 7.

Guinier plots of SAXS intensities for free Klenow polymerase (open symbols) and DNA-bound Klenow polymerase (solid symbols) at 23°C (circles) and 37°C (triangles) under the same buffer conditions in which the binding experiments were performed. Radius of gyration values for the apo protein and the complex are obtained from the slopes of these lines (slope = (Rg)2/3). Rg values are reported in Table 3.

TABLE 3.

Radius of gyration changes upon 13/20-mer DNA binding to Klenow polymerase measured by SAXS

| Sample | RgGuinier (Å) | ΔRgGuinier‡ (Å) | RgGnom (Å) | ΔRgGnom‡ (Å) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| KF apo @ 23°C | 28.85 ± 0.13* | −0.3 ± 0.18§ | 29.05 ± 0.11* | −0.79 ± 0.12§ |

| Complex @ 23°C | 28.55 ± 0.13* | 28.26 ± 0.04* | ||

| KF apo @ 37°C | 31.07 ± 0.29† | −1.02 ± 0.93§

|

31.38 ± 0.63† | −1.77 ± 1.03§

|

| Complex @ 37°C | 30.05 ± 0.88† | 29.61 ± 0.81† |

Rg calculated from a single scattering curve ± error of fit.

Mean Rg calculated from six scattering curves ± standard deviation.

ΔRg is the RgComplex minus RgKF apo at each temperature.

Value is ΔRg ± absolute uncertainty.

Structural changes in Klenow are often inferred by extrapolation from structural changes observed in the crystal structures of other type I DNA polymerases, especially Taq polymerase (15,17). Conformational rearrangements upon DNA binding are clearly observable in the comparison of the apo and binary complex crystal structures of Taq polymerase (13–15,17), and so similar conformational changes are generally assumed to occur in other type I polymerases. The apo structure for Klenow polymerase, however, does not contain side-chain data, and as yet there is no crystal structure for a binary complex of Klenow in the polymerization mode. Surface area calculations performed on the Taq polymerase apo and DNA-bound crystal structures indicate a slight compaction upon DNA binding in that system (data not shown). Our SAXS measurements thus provide, to our knowledge, the first experimental evidence that the generally assumed analogous compaction occurs upon DNA binding by Klenow; however the details of this conformational change, and how similar it is to that for Taq, remain unresolved.

Sequence changes in the single-stranded portion of the DNA have little or no effect on Klenow binding affinity

Joyce and associates recently demonstrated that the binding affinity of Klenow for primed-template DNA is significantly reduced as the number of bases in the single-stranded template overhang is decreased (10). Similar results were also recently published for DNA binding by T4 DNA polymerase (25). At the salt concentrations used in our studies (300 mM KCl), Klenow binds ds-DNA very weakly (Wowor and LiCata, data not shown). Thus, specific interactions between the polymerase and the single-stranded portion of the substrate DNA clearly contribute significantly to the overall ΔGo of stability of the complex. We assayed for sequence-specific binding effects in this region of the DNA by changing the bases in the single-stranded template overhang. Scheme 1 shows the DNA constructs used, and in each case the overhang consisted of a homogeneous seven-nucleotide sequence. A poly-G construct was omitted because of the recent finding that such a construct would form an alternate higher order structure (40). Fluorescence anisotropy-based binding assays were performed at 25°C with each of the altered sequence constructs. The binding affinities for “mixed sequence” 13/20-mer, 13/20polyT, and 13/20polyC are all identical within error (ΔG = −11.1 ± 0.2 kcal/mole, −11.2 ± 0.2 kcal/mole, and −11.1 ± 0.2 kcal/mole, respectively), whereas the binding of Klenow to 13/20polyA is slightly weaker (ΔG = −10.6 ± 0.2 kcal/mole). Thus, there is little or no binding affinity dependence on the sequence of the single-stranded portion of this primed-template construct. Other slightly larger, but still quite subtle, sequence dependent effects have been observed previously for Klenow-DNA binding when the binding to different DNA constructs has been compared (21–23). None of these modest variations have indicated that Klenow displays any true sequence specificity, especially when compared to typical restriction endonucleases or transcriptional regulators. A systematic examination of binding affinity changes due to sequence dependent changes in the double-stranded portion of the primed-template DNA has yet to be conducted.

DISCUSSION

Measuring subtle and not-so-subtle changes in binding energetics

In this study we have characterized the temperature dependence of DNA binding by Klenow DNA polymerase to characterize the thermodynamic driving forces involved in the formation of the protein-DNA complex. Our results show that over the temperature range of 5–37°C, the DNA binding affinity of Klenow varies nonlinearly and thus has a significant negative ΔCp associated with binding. ΔCp is the temperature dependence of the enthalpy, so as shown in Figs. 3 and 5 and Tables 1 and 2, the ΔH of binding of Klenow to DNA changes dramatically with temperature.

A seemingly small ΔCp value for a process (e.g., 1 kcal/mole K) can result in a relatively large excursion of ΔH (e.g., −30 to +30 kcal/mole) across even a restricted “physiological” temperature range. In comparison, the ΔG of binding for most protein-DNA interactions generally exhibits only modest changes across the physiological temperature range (18–20). This results in a change in the value of TΔS with respect to temperature that parallels the change in ΔH with respect to temperature. This general thermodynamic effect is denoted “enthalpy-entropy compensation” and is a very common characteristic of site-specific protein-DNA interactions. This thermodynamic profile is well represented in Fig. 3.

The actual range of Kd values for binding of Klenow polymerase to DNA at different temperatures is quite narrow and corresponds to only about a 1 kcal/mole range from the weakest to the tightest binding. With most DNA binding assays (e.g., filter binding or gel shift assays) such small changes would be difficult if not impossible to detect; however, as seen from the titration curves in Fig. 1, such shifts are reliably quantitated using the fluorescence anisotropy assay. Nonetheless, the temperature dependent changes in Klenow's binding affinity are the most subtle (i.e., exhibit the narrowest range of change) that we have thus far characterized during the course of our solvent and temperature dependent characterizations of different Type I DNA polymerases (26,28). As noted above, however, in contrast to the small variation in Kd or ΔG, chemical processes with an associated ΔCp will exhibit large temperature dependent changes in ΔH and TΔS. For this reason, direct calorimetric measurements of the ΔH of binding provide important corroborating data for the thermodynamic parameters obtained from the Gibbs-Helmholtz analysis of the equilibrium binding data, experimentally confirming the conclusions from the quite subtle changes in the measured temperature dependence of ΔG.

Entropy-driven versus enthalpy-driven binding

The binding of Klenow to primer-template DNA is entropy driven (and enthalpically unfavorable) at lower temperatures and switches to enthalpy driven (and entropically unfavorable) near its physiological temperature of ∼37°C. A similar trend was observed for the DNA binding of Taq DNA polymerase, where the binding is entropy driven at lower temperatures and enthalpy driven at its physiological temperature of ∼75°C (26). Discrepancy between van 't Hoff and calorimetric enthalpies has been observed in a number of different systems and is often ascribed to linked processes such as protonation/deprotonation. The discrepancies in ΔHvH versus ΔHcal values for Klenow in Tables 1 and 2 is consistently near the 3–4 kcal/mole ΔH predicted by the linked buffer protonation measurements in Fig. 5 A.

Although both polymerases can bind DNA with high affinity across a wide temperature range, they cannot necessarily catalyze polymerization over the same temperature ranges. Taq polymerase, for example, only catalyzes polymerization in the temperature range where binding is enthalpically driven (26). This correlation raises the question of whether enzymatic catalysis for the polymerases is somehow energetically or mechanistically linked to an initial enthalpically driven mode of binding.

DNA binding by DNA polymerases is associated with significant heat capacities

Herein we report a significant negative ΔCp of binding for Klenow DNA polymerase. A negative ΔCp was also found in our recent temperature dependent DNA binding studies of Taq DNA polymerase (26). Nonzero values of ΔCp (and thus thermodynamic profiles similar to Fig. 3) are generally characteristic of site-specific DNA binding by sequence-specific binding proteins (18–20,24,41–48); however Type I DNA polymerases show little DNA sequence specificity. Since the data for Taq were the first binding heat capacity data for any DNA polymerase, it was not possible to determine if a significant ΔCp of binding was a unique property of Taq polymerase or if it was a general property of DNA binding by DNA polymerases. The data of this work suggest the latter and thus that DNA polymerases in general might behave thermodynamically more like sequence-specific DNA binding proteins than nonsequence-specific DNA binding proteins.

Although DNA polymerases are not true sequence-specific binders, neither are they directly comparable to the nonspecific binding mode of sequence-specific binding proteins. For the polymerases, we believe it may be recognition of a specific DNA structure, the primer-template junction, that correlates with the observed large negative ΔCp of binding. Although a dozen or more examples exist of sequence-specific binding proteins which bind nonspecific DNA with zero ΔCp (18–20), Klenow represents one of a small number of characterized examples of predominantly nonsequence-specific binding proteins that have a significant ΔCp of DNA binding. In addition to Klenow and Taq (26) DNA polymerases, negative ΔCp values have also been found for the single-stranded DNA binding protein SSB from E. coli (24) and the double-stranded DNA binding protein Sso7d from Sulfolobus solfataricus (49). The ΔCp values for DNA binding in these four systems, although definitively nonzero, are in the mid to low range of ΔCp values seen for sequence-specific binding proteins, which can generally range up to ∼−2.0 kcal/mole K (18–20,24,41–48).

The heat capacity of Klenow-DNA binding cannot be accounted for by changes in accessible surface area

Characterization of the ΔCp of DNA binding is also of interest because in many systems it has been shown to be correlated with structural information: specifically the change in accessible surface area upon binding (ΔASA) (19,20). Here we find a mean ΔCp of −890 cal/mole K for the binding of Klenow to 13/20-mer DNA (mean of the calorimetric and Gibbs-Helmholtz values). The contact area in the binding interface calculated from the crystal structure of the editing complex of Klenow bound to DNA (PDB file 1KLN, Beese et al. (50)) is 2740 Å2 (51) (there is no crystal structure of Klenow with DNA bound in the polymerization mode). The DNA in the crystal structure of the Klenow editing complex is a 10/13-mer, so it is similar to the shorter DNA construct used in our binding studies. Almost all the nucleotides present in the crystal structure are in contact with the polymerase (51), indicating that a highly stereochemically complementary interface is formed. The protein portion of the binding interface in the crystal structure consists of 712 Å2 of nonpolar surface area and 516 Å2 of polar surface area. If both the protein and the DNA portions of the interface are considered, the interface buries ∼1440 Å2 of nonpolar surface area and ∼1300 Å2 of polar surface area (J. Janin, Laboratoire d' Enzymologie et Biochimie Structurales, Universite Paris-Sud, Gif-sur-Yvette, France, personal communication, 2003).

At least four different quantitative relationships between ΔCp and the sum of buried nonpolar + polar surface areas have been proposed (52–55). All four relationships have the form ΔCp = −(x × ΔASAnonpolar – y × ΔASApolar), where ΔASAnonpolar and ΔASApolar are the amounts of nonpolar and polar surface area buried in the interface and x and y are empirically determined constants. Although there are numerous exceptions to these proposed correlations (41–43,45,46), many systems do follow them, and so it is instructive to determine whether or not a system does, or does not, follow a ΔCp-ΔASA correlation, since these correlations can be powerfully predictive for detailed studies of the systems where they hold. A ΔCp-ΔASA correlation does not hold for the binding of Klenow to DNA. Using the ΔASAnonpolar and ΔASApolar values calculated from the crystal structures, the mean ΔCp predicted from the four published correlations is only 38% of the experimentally measured ΔCp of −890 cal/mole K. Even using the single ΔCp-ΔASA relationship that predicts the largest ΔCp still only accounts for 54% of the measured value. A similar finding was reported for Taq polymerase binding to primed-template DNA (26). In the case of Taq polymerase, the apo and polymerization-mode DNA-bound structures were available for more directly relevant calculations, yet buried surface area still proved inadequate to completely account for the measured ΔCp of complex formation.

In their examination of four different DNA polymerase structures, Janin and co-workers noted a correlation between the length of the DNA in the complexes and the amount of buried surface area (51). Although their sample size was too small to make conclusions beyond noting the existence of the correlation, it is an interesting parallel that our data show that increasing the length of the DNA increases the ΔCp of binding. So although these observations certainly support the concept that buried surface area contributes to the measured ΔCp of Klenow DNA binding, the data of this study also show, in a number of ways, that it is not the only contribution to the ΔCp.

Induced fit compaction of the polymerase upon DNA binding

Conformational changes in the protein were further examined using SAXS. Unbound 13/20-mer DNA used in the SAXS experiments is virtually invisible in these measurements due to its relative size, so SAXS data directly monitor the apo-polymerase and the polymerase-DNA complex. The SAXS experiments show a small decrease in Rg upon DNA binding (Table 3), indicating an induced fit compaction of the protein structure upon complex formation. Such induced fit processes, along with coupled folding processes, have also been implicated as partially accounting for “missing” ΔCp of binding in some systems, since the induced fit compaction or coupled folding will bury surface area in addition to that buried in the protein-DNA interface (20). Experimentally assaying for this possibility is one of the primary reasons we directly measured the size changes upon DNA binding for Klenow in solution. However, even adding this contribution to ΔASA for Klenow still cannot account for the measured ΔCp, using any of the ΔASA-ΔCp relationships. The mean decrease in Rg upon DNA binding measured for Klenow is ∼1 Å. A 1 Å change in the radius of a sphere with the Rg of apo-Klenow would alter its surface area by 750 Å2. Klenow is clearly not a sphere, and comparison of the spherical estimate of total surface area with surface area calculated directly from the crystal structure shows an ∼1:2 ratio (data not shown). Using this ratio, we estimate a 1500 Å2 change in surface area from the 1 Å decrease in Rg. Then using a standard assumption that 55% of this surface area is polar (20), and calculating the predicted additional ΔCp (52–55) from the burial of this additional surface area only accounts for an additional 120 cal/mole K (∼14% of the total measured ΔCp). This still leaves 48% of the ΔCp unaccounted for by surface area changes. There would have to be more than a 4.5 Å Rg difference between the apo protein and the DNA-bound complex to account for the additional ΔCp, and this is clearly not the case.

Other sources of the ΔCp of Klenow-DNA binding

Several other molecular sources for heat capacity changes have been proposed (18,41,45,56), and thus we assayed for the presence or absence of such potential molecular events in Klenow-DNA association. The CD spectra of the free and Klenow-DNA complex (Fig. 6) show small but observable changes in the conformations of both the DNA and the protein upon complex formation, which is notable because DNA distortion upon binding has been proposed as a source of ΔCp in some systems (45). Similar CD monitoring of the binding of Klentaq (the large fragment domain of Taq polymerase) also showed minor spectral changes upon complex formation (26), but those for Klenow binding are comparatively smaller in magnitude.

It has also been suggested that restriction of vibrational modes upon complex formation can contribute to an observed negative ΔCp (18,41,56). For example, for EcoR1 and BamH1 it has been proposed that in addition to the hydrophobic effect, the immobilization of water, protein side chains, DNA bases, and backbone elements also contribute to the negative ΔCp of DNA binding (18). The cocrystal structure of Klenow with DNA shows a more ordered conformation of the protein in certain regions as compared to the apo-structure (50,57). Global vibrational restriction of Klenow upon DNA binding is also suggested by stabilization of the protein upon DNA binding. There is an ∼7°C increase in the Tm (melting temperature) of the complex compared to the free protein (data not shown) and the free energy of stabilization of the protein should increase from −4.7 kcal/mole (58) to ∼−16 kcal/mole (sum of the folding and binding free energies) as a result of DNA binding.

The linked proton uptake upon Klenow-DNA binding is another potential source of the measured ΔCp. Whereas net cation release from the DNA has long been known to be a major driving force in protein-DNA complex formation (e.g., see Jen-Jacobson et al. (18), Ha et al. (19), and Spolar and Record (20)), the role of protonation/deprotonation effects in DNA-protein interactions has only been characterized in a small number of systems. Lohman and associates (32) and Hard and associates (31) have reported proton uptake upon complex formation in the binding of SSB to ssDNA and binding of the glucocorticoid receptor to DNA, respectively. Lohman and associates show that in the case of SSB, the linked uptake of protons upon DNA binding can account for a substantial portion of the measured ΔCp of DNA binding (32). The linked proton uptake in the SSB system is significantly larger than the modest uptake measured for Klenow DNA binding, but such linkages are strongly pH dependent.

Thus, when we look for the presence or absence of other molecular level sources that have been proposed to partially account for ΔCp values in other protein-DNA interactions, positive evidence is found for each of them in Klenow. The relative quantitative contributions of each of these, and/or other potential molecular processes, to the ∼48% of Klenow's ΔCp that cannot be accounted for by burial of accessible surface area are not resolved by this study and constitute a subject for future investigation. A precise quantitative accounting of the molecular sources of nonhydrophobic-effect (surface area) related contributions to ΔCp is an extensively involved task and has only been fully achieved for one protein-DNA system (24,32,59). Much of the current discussion surrounding ΔCp effects in protein-DNA interactions, however, continues to focus on the issues of 1), when a particular DNA-protein interaction will or will not exhibit a significant ΔCp, and 2), when ΔCp can or cannot be exclusively accounted for by the hydrophobic effect. These are the two ΔCp issues we have resolved for Klenow polymerase in this study.

Nonsequence-specific binding of DNA polymerases and heat capacity effects

In a recent review, Murphy and Churchill discuss four types or modes of DNA recognition: 1), sequence specific, 2), nonspecific, 3), minimal sequence specific, and 4), structure specific (60). This is, of course, only one possible classification scheme. In their review, Murphy and Churchill note that, in general, the sequence-specific binding (mode 1) is associated with a large negative ΔCp, nonspecific binding (mode 2) is associated with near zero ΔCp, minimal-sequence-specific binding (mode 3) is associated with a “slightly negative” ΔCp, and structure-specific binding (mode 4) had not yet been thermodynamically characterized.

Klenow, Taq, and Klentaq polymerases are effectively DNA structure-specific binding proteins. They bind preferably to a primed-template structure, independent of the sequence of that structure. These polymerases have ΔCp values for DNA binding that are distinctly nonzero but are smaller than the ΔCp values associated with DNA-sequence-specific binding. The question arises whether E. coli SSB (24) and S. solfataricus Sso7d (49) provided the first glimpses of the types of heat capacity changes associated with a structure-specific DNA binding mode. Is a strong preference for ss-DNA over ds-DNA enough to constitute structure-specific DNA binding? For S. solfataricus Sso7d, classification within the Murphy and Churchill taxonomy is more difficult: it preferentially binds ds-DNA over other DNA structures, but even restriction enzymes nonspecifically bind ds-DNA with higher affinity than other structures. In their study originally characterizing the thermodynamics of binding of Sso7d, Lundback and associates suggested that its status as a “true nonsequence-specific DNA binder” might correlate with its unexpectedly large negative ΔCp values (see Lundback et al. (49) and Discussion therein). If there is a ΔCp signature associated with DNA structure-specific binding or true nonsequence-specific binding, its elucidation must await the thermodynamic characterization of other similar primarily nonsequence dependent DNA binding proteins.

Far more sequence-specific DNA binding proteins have been thermodynamically characterized than nonspecific DNA binding proteins. In a recent review of the existing database, Jen-Jacobsen and colleagues pointed out that some correlation does exist between higher binding affinity and higher heat capacity (18). It may be possible that any DNA binding protein, specific or nonspecific, that binds with high enough affinity will exhibit a significant heat capacity change upon binding. Many more systems must be characterized before definitive existence of such a correlation may be discerned. This proposition, however, along with the increasing number of exceptions to the ΔCp-ΔASA correlation and the slowly increasing empirical evidence for alternate molecular sources of ΔCp in protein-DNA interactions, suggests possible directional correlations between thermodynamic and molecular/structural information. For example, it is possible that buried hydrophobic surface area will always exhibit a significant negative ΔCp; but the opposite might not hold, i.e., a significant negative ΔCp may not always be quantitatively accountable by buried hydrophobic surface area, and a lack of a ΔCp may not always be indicative that no hydrophobic surface area is buried. Similarly, DNA sequence-specific binding may always exhibit a significant negative ΔCp; but a significant negative ΔCp may not always be indicative of DNA sequence-specific binding. The growing body of evidence indicates that some binary correlations, such as ΔCp-ΔASA correlations and large ΔCp-sequence-specific binding correlations, will hold strongly for some systems and may even generally dominate the empirical protein-DNA interaction database but that a significant subset of protein-DNA interactions will have a more complicated structure to ΔCp relationship. Only continued examination of new and different protein-DNA interactions will elucidate these issues.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Science Foundation grant MCB 0416568. A.J.R. was supported by National Science Foundation IGERT training grant No. 9987603.

Kausiki Datta's present address is Institute of Molecular Biology, University of Oregon, Eugene, OR 97403.

References

- 1.Kornberg, A., I. R. Lehman, M. J. Bessman, and E. S. Simms. 1956. Enzymic synthesis of deoxyribonucleic acid. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 21:197–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lehman, I. R., M. J. Bessman, E. S. Simms, and A. Kornberg. 1958. Enzymatic synthesis of deoxyribonucleic acid. I. Preparation of substrates and partial purification of an enzyme from Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 233:163–170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Klenow, H., and I. Henningsen. 1970. Selective elimination of the exonuclease activity of the deoxyribonucleic acid polymerase from Escherichia coli B by limited proteolysis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 65:168–175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Joyce, C. M., and N. D. Grindley. 1983. Construction of a plasmid that overproduces the large proteolytic fragment (Klenow fragment) of DNA polymerase I of Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 80:1830–1834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Joyce, C. M., and T. A. Steitz. 1994. Function and structure relationships in DNA polymerases. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 63:777–822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Steitz, T. A. 1999. DNA polymerases: structural diversity and common mechanisms. J. Biol. Chem. 274:17395–17398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Catalano, C. E., D. J. Allen, and S. J. Benkovic. 1990. Interaction of Escherichia coli DNA polymerase I with azidoDNA and fluorescent DNA probes: identification of protein-DNA contacts. Biochemistry. 29:3612–3621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pandey, V. N., N. Kaushik, and M. J. Modak. 1994. Photoaffinity labeling of DNA template-primer binding site in Escherichia coli DNA polymerase I. Identification of involved amino acids. J. Biol. Chem. 269:21828–21834. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Minnick, D. T., M. Astatke, C. M. Joyce, and T. A. Kunkel. 1996. A thumb subdomain mutant of the large fragment of Escherichia coli DNA polymerase I with reduced DNA binding affinity, processivity, and frameshift fidelity. J. Biol. Chem. 271:24954–24961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Turner, R. M., N. D. F. Grindley, and C. M. Joyce. 2003. Interaction of DNA polymerase I (Klenow fragment) with the single-stranded template beyond the site of synthesis. Biochemistry. 42:2373–2385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Singh, K., and M. J. Modak. 2003. Presence of 18-Å long hydrogen bond track in the active site of Escherichia coli DNA polymerase I (Klenow fragment). Its requirement in the stabilization of enzyme-template-primer complex. J. Biol. Chem. 278:11289–11302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Srivastava, A., K. Singh, and M. J. Modak. 2003. Phe 771 of Escherichia coli DNA polymerase I (Klenow fragment) is the major site for the interaction with the template overhang and the stabilization of the pre-polymerase ternary complex. Biochemistry. 42:3645–3654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Korolev, S., M. Nayal, W. M. Barnes, E. DiCera, and G. Waksman. 1995. Crystal structure of the large fragment of Thermus aquaticus DNA polymerase I at 2.5-A resolution: structural basis for thermostability. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 92:9264–9268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim, Y., S. H. Eom, J. Wang, D. S. Lee, S. W. Suh, and T. A. Steitz. 1995. Crystal structure of Thermus aquaticus DNA polymerase. Nature. 376:612–616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eom, S. H., J. Wang, and T. A. Steitz. 1996. Structure of Taq polymerase with DNA at the polymerase active site. Nature. 382:278–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang, J., K. M. A. Sattar, C. C. Wang, J. D. Karam, W. H. Konigsberg, and T. A. Steitz. 1997. Crystal structure of a pol alpha family replication DNA polymerase from bacteriophage RB69. Cell. 89:1087–1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li, Y., S. Korolev, and G. Waksman. 1998. Crystal structures of open and closed forms of binary and ternary complexes of the large fragment of Thermus aquaticus DNA polymerase I: structural basis for nucleotide incorporation. EMBO J. 17:7514–7525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jen-Jacobson, L., L. E. Engler, J. T. Ames, M. R. Kurpiewski, and A. Grigorescu. 2000. Thermodynamic parameters of specific and nonspecific protein-DNA binding. Supramol. Chem. 12:143–160. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ha, J.-H., R. S. Spolar, and M. T. Record. 1989. Role of the hydrophobic effect in stability of site-specific protein-DNA complexes. J. Mol. Biol. 209:801–816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Spolar, R. S., and M. T. Record Jr. 1994. Coupling of local folding to site-specific binding of proteins to DNA. Science. 263:777–784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kuchta, R. D., V. Mizrahi, P. A. Benkovic, K. A. Johnson, and S. J. Benkovic. 1987. Kinetic mechanism of DNA polymerase I (Klenow). Biochemistry. 26:8410–8417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carver, T. E. Jr., and D. P. Millar. 1998. Recognition of sequence-directed DNA structure by the Klenow fragment of DNA polymerase I. Biochemistry. 37:1898–1904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thompson, E. H. Z., M. F. Bailey, E. J. C. van der Schans, C. M. Joyce, and D. P. Millar. 2002. Determinants of DNA mismatch recognition within the polymerase domain of the Klenow fragment. Biochemistry. 41:713–722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ferrari, M. E., and T. M. Lohman. 1994. Apparent heat capacity change accompanying a nonspecific protein-DNA interaction. Escherichia coli SSB tetramer binding to oligodeoxyadenylates. Biochemistry. 33:12896–12910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Delagoutte, E., and P. H. von Hippel. 2003. Function and assembly of the bacteriophage T4 DNA replication complex: interactions of the T4 polymerase with various model DNA constructs. J. Biol. Chem. 278:25435–25447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Datta, K., and V. J. LiCata. 2003. Thermodynamics of the binding of Taq DNA polymerase to primed-template DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 31:5590–5597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Derbyshire, V., P. S. Freemont, M. R. Sanderson, L. Beese, J. M. Friedman, C. M. Joyce, and T. A. Steitz. 1988. Genetic and cystallographic studies of the 3′,5′-exonucliolytic site of DNA polymerase I. Science. 240:199–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Datta, K., and V. J. LiCata. 2003. Salt dependence of DNA binding by Thermus aquaticus and Escherichia coli DNA polymerases. J. Biol. Chem. 278:5694–5701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Joyce, C. M., and V. Derbyshire. 1995. Purification of Escherichia coli DNA polymerase I and Klenow fragment. Methods Enzymol. 262:3–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baker, B. M., and K. P. Murphy. 1996. Evaluation of linked protonation effects in protein binding reactions using isothermal titration calorimetry. Biophys. J. 71:2049–2055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lundback, T., S. van Den Berg, and T. Hard. 2000. Sequence-specific DNA binding by the glucocorticoid receptor DNA binding domain is linked to a salt-dependent histidine protonation. Biochemistry. 39:8909–8916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kozlov, A. G., and T. M. Lohman. 2000. Large contributions of coupled protonation equilibria to the observed enthalpy and heat capacity changes for ssDNA binding to Escherichia coli SSB protein. Proteins. 4(Suppl):8–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Karantzeni, I., C. R. Ruiz, C.-C. Liu, and V. J. LiCata. 2003. Comparative thermal denaturation of Thermus aquaticus and Escherichia coli type I DNA polymerases. Biochem. J. 374:785–792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Guinier, A., and G. Fournet. 1955. Small angle scattering of x-rays. Wiley, NY.

- 35.Guinier, A. 1939. La diffraction des rayons X aux tres petits angles; application a l'etude de phenomenes ultramicroscopiques. Ann. Phys. 12:166–237. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Semenyuk, A. V., and D. I. Svergun. 1991. GNOM—a program package for small-angle scattering data-processing. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 24:537–540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Joubert, A. M., A. S. Byrd, and V. J. LiCata. 2003. Global conformations, hydrodynamics, and x-ray scattering properties of Taq and Escherichia coli DNA polymerases in solution. J. Biol. Chem. 278:25341–25347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu, Y. F., and J. M. Sturtevant. 1997. Significant discrepancies between van 't Hoff and calorimetric enthalpies.III. Biophys. Chem. 64:121–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Horn, J. R., J. F. Brandts, and K. P. Murphy. 2002. van 't Hoff and calorimetric enthalpies II: effects of linked equilibria. Biochemistry. 41:7501–7507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Poon, K., and R. B. Macgregor Jr. 1998. Unusual behavior exhibited by multistranded guanine-rich DNA complexes. Biopolymers. 45:427–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ladbury, J. E., J. G. Wright, J. M. Sturtevant, and P. B. Sigler. 1994. A thermodynamic study of the trp repressor-operator interaction. J. Mol. Biol. 238:669–681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Merabet, E., and G. K. Ackers. 1995. Calorimetric analysis of lambda cI repressor binding to DNA operator sites. Biochemistry. 34:8554–8563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jin, L., J. Yang, and J. Carey. 1993. Thermodynamics of ligand binding to trp repressor. Biochemistry. 32:7302–7309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lundback, T., C. Cairns, J. A. Gustafsson, J. Carlstedt-Duke, and T. Hard. 1993. Thermodynamics of the glucocorticoid receptor-DNA interaction: binding of wild-type GR DBD to different response elements. Biochemistry. 32:5074–5082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Petri, V., M. Hsieh, and M. Brenowitz. 1995. Thermodynamic and kinetic characterization of the binding of the TATA binding protein to the adenovirus E4 promoter. Biochemistry. 34:9977–9984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Morton, C. J., and J. E. Ladbury. 1996. Water-mediated protein-DNA interactions: the relationship of thermodynamics to structural detail. Protein Sci. 5:2115–2118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Berger, C., I. Jelesarov, and H. R. Bosshard. 1996. Coupled folding and site-specific binding of the GCN4-bZIP transcription factor to the AP-1 and ATF/CREB DNA sites studied by microcalorimetry. Biochemistry. 35:14984–14991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lipps, G., M. Stegert, and G. Krauss. 2001. Thermostable and site-specific DNA binding of the gene product ORF56 from the Sulfolobus islandicus plasmid pRN1, a putative archael plasmid copy control protein. Nucleic Acids Res. 29:904–913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lundback, T., H. Hansson, S. Knapp, R. Ladenstein, and T. Hard. 1998. Thermodynamic characterization of non-sequence-specific DNA binding by the Sso7d protein from Sulfolobus solfataricus. J. Mol. Biol. 276:775–786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Beese, L. S., V. Derbyshire, and T. A. Steitz. 1993. Structure of DNA polymerase I Klenow fragment bound to duplex DNA. Science. 260:352–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nadassy, K., S. J. Wodak, and J. Janin. 1999. Structural features of protein-nucleic acid recognition sites. Biochemistry. 38:1999–2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Spolar, R. S., J. R. Livingstone, and M. T. Record. 1992. Use of liquid hydrocarbon and amide transfer data to estimate contributions to thermodynamic functions of protein folding from the removal of nonpolar and polar surface from water. Biochemistry. 31:3947–3955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Murphy, K. P., and E. Freire. 1992. Thermodynamics of structural stability and cooperative folding behavior in proteins. Adv. Protein Chem. 43:313–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Makhatadze, G. I., and P. L. Privalov. 1995. Energetics of protein structure. Adv. Protein Chem. 47:307–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Myers, J. K., C. N. Pace, and J. M. Scholtz. 1995. Denaturant m values and heat capacity changes: relation to changes in accessible surface areas of protein unfolding. Protein Sci. 4:2138–2148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sturtevant, J. M. 1977. Heat capacity and entropy changes in processes involving proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 74:2236–2240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ollis, D. L., P. Brick, R. Hamlin, N. G. Xuong, and T. A. Steitz. 1985. Structure of large fragment of Escherichia coli DNA polymerase I complexed with dTMP. Nature. 313:762–766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schoeffler, A. J., A. M. Joubert, F. Peng, F. Khan, C. C. Liu, and V. J. LiCata. 2004. Extreme free energy of stabilization of Taq DNA polymerase. Proteins. 54:616–621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kozlov, A. G., and T. M. Lohman. 1999. Adenine base unstacking dominates the observed enthalpy and heat capacity changes for the Escherichia coli SSB tetramer binding to single-stranded oligoadenylates. Biochemistry. 38:7388–7397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Murphy, F. V., and M. E. Churchill. 2000. Nonsequence-specific DNA recognition: a structural perspective. Structure. 8:R83–R89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]