Abstract

CD8+ T lymphocytes can suppress human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) replication by secreting a soluble factor(s) known as CD8+ T-lymphocyte antiviral factor (CAF). One site of CAF action is inhibition of HIV-1 RNA transcription, particularly at the step of long terminal repeat (LTR)-driven gene expression. However, the mechanism by which CAF inhibits LTR activation is not understood. Here, we show that conditioned media from several herpesvirus saimari-transformed CD8+ T lymphocytes inhibit, in a time- and dose-dependent manner, the replication of HIV-1 pseudotype viruses that express the envelope glycoproteins of vesicular stomatitis virus (HIV-1VSV). The same conditioned media also inhibit phorbol myristate acetate-induced activation of the HIV-1 LTR and activate the signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 (STAT1) protein. We have obtained direct evidence that STAT1 is necessary for CAF-mediated inhibition of LTR activation and HIV-1 replication. Thus, the inhibitory effect of CAF on HIV-1VSV replication was abolished in STAT1-deficient cells. Moreover, CAF inhibition of LTR activation was diminished both in STAT1-deficient cells and in cells expressing a STAT1 dominant negative mutant but was restored when STAT1 was reintroduced into the STAT1-deficient cells. We also observed that CAF induced the expression of interferon regulatory factor 1 (IRF-1), and that IRF-1 gene induction was STAT-1 dependent. Taken together, our results suggest that CAF activates STAT1, leading to IRF-1 induction and inhibition of gene expression regulated by the HIV-1 LTR. This study therefore helps clarify one molecular mechanism of host defense against HIV-1.

The importance of cell-mediated immunity for the partial control of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) replication in infected individuals is now widely recognized (31, 37, 42, 49, 59, 60, 64, 74, 97). The direct killing of virus-infected cells by antigen-specific, cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTL) is considered to be the dominant mechanism of virus suppression, yet it has been known for over 15 years that a noncytotoxic, soluble factor(s) is also capable of inhibiting HIV-1 replication in vitro (24, 50, 95, 100). The soluble factor(s) is secreted from CD8+ T lymphocytes of HIV-1-infected people and is usually designated CD8+-T-lymphocyte antiviral factor, or CAF (92, 99, 100). Both CTL-dependent and CAF-associated antiviral activities have been reported to correlate with delayed disease progression in HIV-1-infected people (10, 55, 96). Whereas the CTL response is major histocompatibility complex class I restricted, this restriction does not apply to inhibition of HIV-1 replication by CAF (98, 100).

Antiviral activity has also been found in conditioned media derived from Epstein-Barr virus-specific CTL (45), influenza A virus-stimulated peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) (70), and CD8+ T cells from HIV-1-infected chimpanzees (11). Furthermore, allogeneic stimulation of human lymphocytes causes the release of a soluble factor(s) that inhibits HIV-1 replication (30). Whether these various activities are attributable to the same factor(s) is not known, but it seems likely that CAF is neither HIV-1 antigen specific nor produced only by CD8+ T lymphocytes. It may well be an innate, rather than an acquired, immune response. Attempts from many laboratories to identify just what component(s) of CAF is responsible for its antiviral effect(s) have not been successful (reviewed in reference 50). One contribution to the antiviral activity of conditioned media from CD8+-T-cell cultures is made by the CC-chemokines macrophage inflammatory protein 1α (MIP-1α), MIP-1β, and RANTES, which inhibit HIV-1 entry via CCR5 (17). However, several studies have shown that these CC-chemokines cannot entirely account for CAF-mediated antiviral effects, particularly since CAF can inhibit the replication of HIV-1 strains that use CXCR4 and not CCR5 for entry (2, 43, 47, 61, 62, 75, 89). It seems probable that the antiviral action of CAF is achieved by more than one cytokine or chemokine secreted by CD8+ cells, perhaps acting in concert.

The molecular mechanism by which CAF inhibits HIV-1 replication has been studied extensively, although such studies are necessarily complicated by the lack of a pure, homogenous, concentrated preparation of the active component(s) of CAF. However, provided that the effects of MIP-1α, MIP-1β, and RANTES are eliminated from consideration (e.g., by the use of a test isolate reliant on a receptor other than CCR5 for entry), it can be shown that CAF does not antagonize viral entry (48, 88, 89). It has also been found that CAF does not inhibit HIV-1 reverse transcription and provirus integration (45, 56, 89), although supernatants from lymphocytes stimulated with allogeneic cells have been reported to block HIV-1 replication prior to, or at, the integration stage (30). Conversely, there are several, independent reports that CAF can inhibit HIV-1 RNA transcription, particularly at the step of long terminal repeat (LTR)-driven gene expression (16, 19, 47, 54). To do this, the active component(s) of CAF must be interacting with a signal transduction system(s), to modulate the transcriptional machinery. How this is achieved is not known, although by deleting the cis-elements for specific transcriptional factors from the HIV-1 LTR, it has been shown that CAF inhibition of LTR-driven gene expression might be mediated by cytokine-stimulated activation of nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) (19, 20) and nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT) (20). However, deletion of the same cis-elements also affects LTR activities in the absence of HIV-1 Tat, which complicates how these results are interpreted (20).

We have focused on the signaling pathways mediated by the STAT proteins (signal transducers and activators of transcription) to gain additional insights into the mechanism of CAF activity, using conditioned media derived from CD8+-T-cell lines as a source of CAF. STAT proteins were first identified as transcriptional factors in interferon (IFN) signaling pathways (27). They are activated by a broad spectrum of extracellular stimuli, including cytokines, hormones, and growth factors (reviewed in reference 78), and play a central role in a wide variety of biological responses, including differentiation and cell growth control (9, 21, 22, 83). In response to stimulation, STAT proteins are activated by tyrosine phosphorylation, dimerize via an SH2 domain, and enter the nucleus to regulate gene expression (reviewed in references 21 and 35). STAT proteins can activate LTR-driven expression of genes from mouse mammary tumor virus (72) and caprine arthritis-encephalitis virus (79). Although there is no evidence that a binding site for STAT proteins is located in the HIV-1 LTR, a downstream binding factor (DBF) site for proteins of IFN regulatory factors 1 and 2 (IRF-1 and IRF-2) is present (93). The IRF family proteins are known to be regulated by STAT proteins and are induced by many stimuli including IFNs, tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), interleukin 1 (IL-1), IL-6, leukemia inhibitory factor, and by viral infection (reviewed in references 84 and 85). In addition, cells expressing a dominant negative form of one of the IRF family proteins are nonpermissive for HIV-1 infection (86).

We have investigated whether STAT and IRF proteins might play a role in the antiviral activity of CAF. Our rationale was that CAF probably contains several active components, that many cytokines which activate STAT proteins have been associated with viral suppression and a lack of disease progression (1, 7, 38, 66, 70, 71), and that IRF protein family members are immediate genes inducible by many cytokines, regulated by STAT proteins, and able to bind the HIV-1 LTR. We found that CAF induced STAT1 activation and IRF-1 gene expression, events which may play a role in the suppression of HIV-1 LTR-driven transcription.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents.

Recombinant human IFN-α was purchased from Biosource International (Camarillo, Calif.), and recombinant human IFN-γ and anti-human IFN-γ were from R&D Systems, Inc. (Minneapolis, Minn.). Antibodies against STAT1 (N terminus, catalogue no. G16930) and IRF-2 were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, Calif.). Antibodies against IRF-1, IFN-α, and IFN-β have been described previously (68, 69).

Cell culture.

HeLa and 1G5 cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, Va.) and the National Institutes of Health AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program, respectively. The 2fTGH and U3A cell lines, derived from HT1080 fibrosarcoma cells, were a gift from G. Stark of the Cleveland Clinic Foundation. The HeLa, 2fTGH, and U3A cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s minimal essential medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Life Technologies, Inc). The 1G5 cells were grown in RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% FBS.

Generation of herpesvirus saimiri (HVS)-transformed CD8+-T-cell lines and conditioned media.

PBMC derived from normal, healthy blood donors or from HIV-1-infected patients were separated from whole blood by Ficoll-Hypaque centrifugation, stimulated for 2 to 3 days with phytohemagglutinin, and then infected in bulk with HVS strain C-488 (provided by R. Desrosiers, New England Regional Primate Center). After 6 to 8 weeks in culture in RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% FBS and IL-2 (20 to 50 U/ml depending on the line; Life Technologies, Inc), viable cells were recovered by Ficoll-Hypaque separation and purified by limiting dilution. Cell lines were analyzed by flow cytometry using a panel of antibodies, including Leu2a, Leu3a, anti-CD25, and anti-HLA-DR (Becton Dickinson, Bedford, Mass.). CD8+-T-cell lines were characterized for secretion of HIV-1 suppressive activity. The K#1 50K, N2, KP1#3 and K#2 (sc-) lines were derived from healthy donors, the CAF10 line from an HIV-1-infected child with rapid disease progression. Conditioned media from lines K#1 50K and CAF10 have previously been reported to strongly suppress the replication of multiple HIV-1 isolates including both X4 and R5 viruses (62, 63).

Inhibition of HIV-1 replication by CAF.

To obtain conditioned media, CD8+ T cells were cultured at 106 per well in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with FBS and IL-2 as described above. After 3 to 4 days, the medium was harvested, residual cells were removed by centrifugation, and the medium was passed through a 0.45-μm-pore-size filter. Macrophages were purified from Ficoll-Hypaque-separated PBMC by adherence to the solid phase during a 14-day culture in RPMI 1640 with 20% FBS. To minimize the effects of CAF on viral entry, the purified macrophages were first incubated with the R5 isolate HIV-1 BaL for 2 h at a multiplicity of infection of 0.5, and then they were washed and subsequently cultured in the presence of CD8+-cell-conditioned medium (10% [vol/vol]). The medium (RPMI 1640 supplemented with IL-2 at 20 to 50 U/ml) was changed every 3 to 4 days, and fresh conditioned medium was added. HIV-1 replication was monitored by measuring p24 antigen by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (Du Pont, Wilmington, Del.).

IFN assays.

CD8+ T cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 containing 10% FBS and IL-2 (50 U/ml) at an initial concentration of 0.5 × 106 per ml. After 72 h, conditioned medium was collected. The following IFNs were quantitated by ELISA with commercially available assays (Biosource International) (with the respective sensitivity limits in parentheses): IFN-α (10 pg/ml), IFN-β (3 pg/ml), IFN-γ (4 pg/ml).

HIV-1 env-pseudotype infection assay.

Vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) Env-pseudotyped, luciferase-expressing reporter viruses (HIV-1VSV) were produced as described previously (15, 18, 23). Briefly, HEK293T cells were cotransfected with a plasmid encoding the envelope-deficient HIV-1 NL4-3 virus, the pNL-Luc plasmid carrying the luciferase reporter gene, and the pSV plasmid expressing the VSV-G glycoprotein. The supernatant medium was collected 48 h after transfection and filtered. Virus stocks were analyzed for HIV-1 p24 antigen concentration by ELISA, as described previously (91).

The effect of CD8+-T-cell-conditioned media on HIV-1 replication was determined by a single-cycle infection assay (15, 18, 23, 90). Target cells were seeded at 5 × 104 per well in a 48-well tissue culture plate, one day before infection, and then they were treated with conditioned media (see below and figure legends for details). The conditioned medium was removed by washing the cells twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), before addition of HIV-1VSV for 2 h at 37°C. Unbound virus was removed by washing, and then the infected cells were incubated for 48 h with fresh medium without CAF (unless otherwise specified). The cells were then washed with PBS and lysed with Luciferase Substrate Buffer (Promega, Inc.). Luciferase activity (measured in relative light units [r.l.u.]) was measured on a Dynex MLX microplate luminometer.

Transfection procedures.

HeLa, 2fTGH, or U3A cells were seeded at 105 per well in a 24-well plate for 16 h. The cells were then cotransfected with a plasmid encoding STAT1 or STAT1 Y701F (0.5 μg of either), the pLTR-Luc plasmid (0.5 μg) containing the luciferase gene driven by the HIV-1 LTR (HIV-LTR-Luc), and the pCH101 reporter plasmid (0.1 μg), which expresses the β-galactosidase gene under the control of the simian virus 40 promoter. Transfections were performed using the LipofectAMINE PLUS reagent (Life Technologies, Inc). The transfected cells were incubated at 37°C for 16 h and then treated with conditioned media from CD8+ T cells for an additional 16 h before addition of phorbol myristate acetate (PMA) (20 ng/ml) for 8 h. To analyze PMA-independent HIV-1 LTR activation, the cells were cotransfected with the pSVtat plasmid expressing Tat proteins that activate the HIV-1 LTR-luciferase gene. Luciferase activity was measured as described above, and β-galactosidase activity was analyzed by the Promega assay system.

EMSA.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) was performed as described previously (12). Whole-cell extracts were prepared by lysis of cells in 20 mM HEPES buffer (pH 7.9) containing 0.2% Nonidet P-40 (NP-40), 10% glycerol, 400 mM NaCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 1 mM sodium orthovanadate, 0.5 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (Roche Diagnostics, GmbH). Binding reactions were carried out at room temperature for 30 min in 15 μl of a buffer containing 13 mM HEPES (pH 7.9), 185 mM NaCl, 0.15 mM EDTA, 8% glycerol, 1 μg of poly(dI-dC), 1 μg of single-stranded DNA, whole-cell extracts (15 μg of protein, in each case), and 5′-end 32P-labeled double-stranded oligonucleotides (0.1 ng; approximately 104 cpm). Samples were then fractionated by electrophoresis in a 5% polyacrylamide gel. For supershift experiments, antibodies (0.1 μg) were added to the reaction mixture after 20 min and the reaction was continued for a further 20 min at room temperature before analysis by gel electrophoresis. The nucleotide sequences of the probes used are as follows: m67 GAS, 5′-GTGCATTTCCCGTAATCTTGTCTACAATTC-3′ (76); DBFHIV, 5′-AGGGACTTGAAAGCGAAAGTAAAGCCAGAG-3′, which spans HIV-1 NL4-3 nucleotides 648 to 678 (93); and ISG15, CTCGGGAAAGGGAAACCGAAACTGAAGCC (69). The GAS (IFN-γ activation site) sequence bound by STAT proteins and the IFN-α-stimulated response element sequence bound by IRF proteins are underlined.

RESULTS

CAF inhibits HIV-1 infection in a time- and dose-dependent manner.

As our source of CAF, we used conditioned medium derived from HVS-transformed CD8+ T cells. This material is described below as CAF; the terms CAF and conditioned medium are used interchangeably, although we fully appreciate that conditioned medium is likely to contain many biologically active molecules.

Conditioned media from CD8+-T-cell lines derived from normal healthy blood donors were screened for their ability to block HIV-1 BaL replication in primary macrophages. In a representative experiment, conditioned media from the N#2 cell line inhibited HIV-1 replication by >90% when added at 10% (vol/vol), whereas medium from the KP1#3 line was only weakly inhibitory at this concentration (Fig. 1A). The level of inhibition for N#2 was similar to that found in previous studies, in which efficient inhibition of HIV-1 replication by supernatants from other lines, including K#1 50K and Caf 10, was observed (62, 63). Unless otherwise indicated, all subsequent experiments were performed with conditioned medium from the K#1 50K line, which was similar in potency to medium from the N#2 line. Conditioned media from the K#1 50K line inhibited the replication of both X4 and R5 strains of HIV-1 (62, 63).

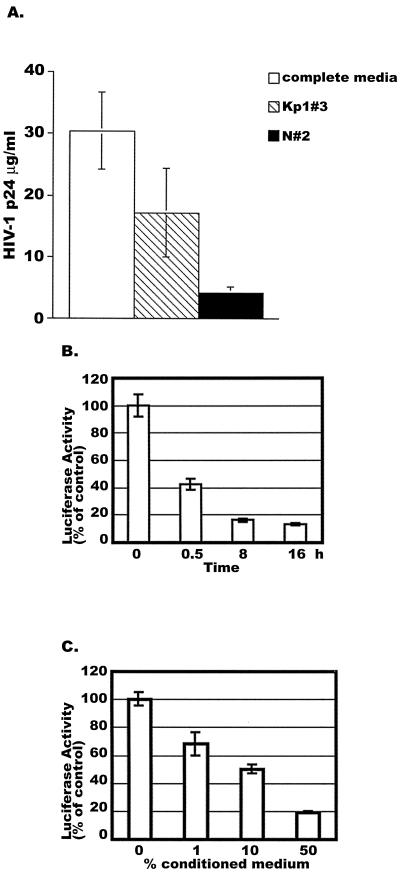

FIG. 1.

Time- and dose-dependent inhibition of HIV-1 infection by CAF. (A) Primary macrophages were infected with HIV-1 BaL and then treated with a 10% concentration of CAF from the indicated CD8+-T-cell lines or with no CAF (complete medium). The extracellular HIV-1 p24 antigen concentration was measured on day 10 postinfection. (B) HeLa cells were treated with a 50% concentration of CAF from the K#1 50K line for the indicated periods before infection with luciferase-expressing HIV-1VSV. (C) HeLa cells were treated with different dilutions of the K#1 50K conditioned medium for 16 h before HIV-1VSV infection. In both experiments, luciferase activities were measured at 48 h postinfection. In panels B and C, the results (mean ± standard error) from triplicate determinations in a single experiment are presented as histograms. Similar results were obtained in another independent experiment. The values represent luciferase activity compared to that derived from cells not treated with CAF, which was defined as 100%. This corresponded to absolute r.l.u. values of 810 ± 80. In panel B, the difference between cells treated with CAF for 16 h and nontreated cells is significant (P = 0.025). In panel C, the difference between cells treated with 50% CAF and nontreated cells is significant (P = 0.023).

To study the kinetics of CAF inhibition of HIV-1 replication during a single viral life cycle, HeLa cells were treated with 50% (vol/vol) K#1 50K conditioned medium for 0, 0.5, 8, and 16 h. The cells were then washed twice with PBS and placed in fresh culture medium (without CAF) for infection with an HIV-1VSV Env-pseudotyped virus that carries a luciferase reporter gene. The use of this virus pseudotype eliminates any influence that any component of the conditioned medium may have on the coreceptors that normally mediate HIV-1 entry. When luciferase activity was determined 2 days after infection was initiated, HIV-1VSV infection was more than 50% lower in the cells that had been pretreated with CAF for 0.5 h prior to virus addition (Fig. 1B). Greater inhibition (87% ± 1% [mean ± standard error] reduction) was observed in cells exposed to CAF for 8 or 16 h before infection with HIV-1VSV (Fig. 1B). Note that CAF was not added back to the cells after they were infected, indicating that the effect of CAF (or of CAF-mediated cell signaling) on the cells was sustained for a prolonged period.

No cytotoxicity was observed in HeLa cells (or 1G5 cells) treated with 50% K#1 50K conditioned medium for 3 days, as determined by a standard intracellular dye reduction assay (data not shown). The same conditioned medium (50% concentration) also had no toxic effects on 2fTGH and 293T cells after 16 h, although some cytotoxicity was observed with these two cell types after 3 days of exposure to the medium at this concentration (data not shown). Most subsequent experiments involved exposure of the target cells to CAF for no longer than 16 h, to minimize any nonspecific effects. Overall, we could find no evidence that the inhibitory effects of CAF on HIV-1 or HIV-1vsv replication that we have analyzed in this paper are due to cytotoxicity. Similar conclusions were reached in previous studies (62, 63).

To determine the concentration of CAF that inhibited HIV-1 infection, HeLa cells were treated with K#1 50K conditioned medium at 1, 10, and 50% (vol/vol) for 16 h and then washed twice with PBS prior to HIV-1VSV infection. When luciferase activity was determined 48 h later, the inhibitory effect of CAF on viral replication was dose dependent (Fig. 1C). Thus, viral replication was inhibited by 32% ± 8% when the cells were exposed to 1% CAF for 16 h before infection, and the inhibition reached 81% ± 1% at a CAF concentration of 50% (Fig. 1C).

Taken together, these experiments show that CAF inhibits HIV-1VSV replication in a time- and dose-dependent manner, independent of any effect that components of the conditioned medium may have on entry mediated by HIV-1 glycoproteins.

CAF inhibits HIV-1 LTR-driven gene expression in 1G5 and HeLa cells.

To further investigate the effect of the K#1 50K conditioned medium on the HIV-1 life cycle, we determined its effect on LTR-mediated gene expression. We first used 1G5 cells, which are derived from the Jurkat cell line and contain a stably transfected luciferase gene under the transcriptional control of the LTR (HIV-LTR-Luc). The 1G5 cells were incubated without or with CAF for 16 h, and then luciferase expression from the LTR was induced by treatment of the cells with PMA (50 ng/ml) for 8 h. In unstimulated cells, luciferase expression was very low (0.5% of control), but its expression was strongly activated by PMA (Fig. 2A). The level of PMA-activated luciferase expression was reduced by 48% ± 8% in the 1G5 cells treated with conditioned medium from the K#1 50K line, compared to cells incubated with unconditioned medium (Fig. 2A, left panel). In contrast, CAF had no effect on gene expression from the pCH101 plasmid driven by the simian virus 40 promoter (data not shown), which is consistent with previously reported findings (19).

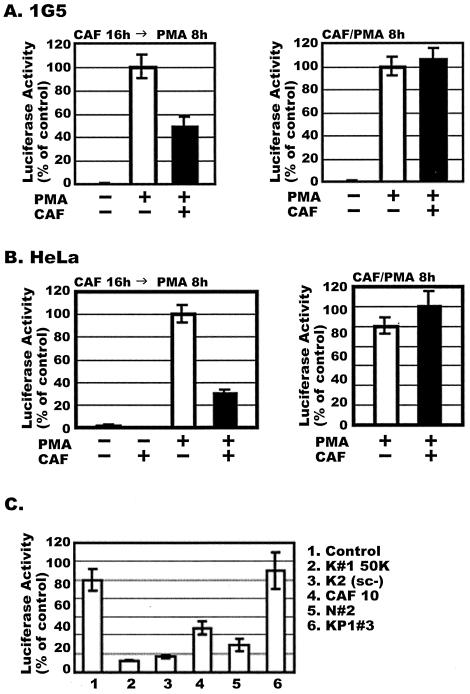

FIG. 2.

Effects of conditioned medium from HVS-transformed CD8+ T cells on HIV-1 LTR activation. (A) (Left panel) 1G5 cells, which stably express the HIV-LTR-Luc construct, were treated for 16 h with or without a 50% concentration of CAF (K#1 50K line), before addition of PMA for 8 h. The P value for the difference between the values obtained from cells treated with 50% CAF and the control cells is 0.012. (Right panel) Cells were treated for 8 h with or without CAF, added simultaneously with PMA. (B) The experiment was as described for panel A, except that HeLa cells were transiently transfected with the HIV-LTR-Luc plasmid for 16 h before treatment with CAF and/or PMA. In both panels A and B, the results (mean ± standard error) from triplicate determinations in a single experiment are presented as histograms. Similar results were obtained in two other independent experiments. The values represent luciferase activity compared to that derived from cells not treated with CAF, which was defined as 100%. This corresponded to absolute r.l.u. values of 243 ± 12 for 1G5 cells and 2,319 ± 41 for HeLa cells. The background values for 1G5 and HeLa cells are 1.5 ± 0.4. Luciferase activities were normalized for cellular protein content (1G5 cells) or β-galactosidase activity (HeLa cells). (C) HeLa cells were transiently transfected with HIV-LTR-Luc and then treated with conditioned media from different HVS-transformed CD8+-T-cell clones for a further 16 h. Luciferase activity was measured after PMA stimulation for 8 h.

No inhibition of PMA-induced luciferase activity by CAF was observed when the 1G5 cells were treated for 8 h with both PMA and CAF, added simultaneously (Fig. 2A, right panel). Thus, to be effective, CAF must be added to the cells before they are PMA activated. This suggests, but certainly does not prove, that the inhibitory effect of CAF on the HIV-1 LTR may not be directly mediated by proteins already present in the cells. Instead, the synthesis of new proteins might be required for CAF to inhibit LTR-mediated gene expression.

To determine whether any residual IL-2 present in the K#1 50K conditioned medium could be influencing the outcome of the experiment, we tested the effect of purified IL-2. When 1G5 cells were incubated with or without medium containing IL-2 (50 U/ml) for 16 h before PMA stimulation for 8 h, luciferase expression was unaffected by the prior IL-2 treatment (data not shown). Hence any IL-2 present in the conditioned medium is unlikely to have had a significant effect on HIV-1 LTR activation and luciferase expression.

The inhibitory effect of the same conditioned medium on HIV-1 LTR activation was also analyzed in HeLa cells transiently transfected with the HIV-LTR-Luc plasmid (Fig. 2B). The transfected cells were treated with or without 50% CAF for 16 h prior to PMA stimulation for 8 h and measurement of luciferase activity. The conditioned medium reduced HIV-1 LTR-mediated transcription in HeLa cells by more than 70% in comparison to cells treated with control medium. As observed with the 1G5 cells, there was no inhibition of HIV-1 LTR activity when the HeLa cells were treated for 8 h with 50% CAF and PMA simultaneously (Fig. 2B).

The HeLa cell transient transfection system was used to examine whether conditioned media from several different HVS-transformed CD8+-T-cell lines had CAF activity, when added at a 50% concentration for 16 h prior to PMA treatment. The conditioned media from lines K#1 50K, K#2 (sc-), CAF10, and N#2 all contained CAF activity (Fig. 2C). However, the medium from the KP1#3 line was not inhibitory, indicating that the secretion of CAF activity is not a universal feature of HSV-transformed cells and is perhaps not a direct consequence of the HSV transformation procedure. Note that the conditioned medium from the KP1#3 line also inhibited HIV-1 replication poorly (Fig. 1A).

CAF from different CD8+-T-cell lines induces STAT1 activation.

To examine whether STAT proteins might be involved in the inhibitory effects of CAF on HIV-1 transcription and replication, the binding of STAT proteins to DNA was measured using an EMSA. We treated 1G5 cells for 15 min with a 50% concentration of several different conditioned media from CD8+-T-cell lines (Fig. 2C). Whole-cell extracts were then prepared and incubated with the 32P-labeled m67-SIE oligonucleotide, which contains a high-affinity DNA binding site for STAT1 and STAT3 (76).

The conditioned media from four CD8+-T-cell lines clearly induced STAT1 but not STAT3 activity (Fig. 3A). The DNA binding protein was confirmed to be STAT1 by performing a supershift assay using antibodies specific to STAT1 proteins (Fig. 3A, lane 6). Activation of STAT1 was also detectable by Western blot analysis using antibodies against phosphorylated tyrosine residues present on activated STAT1 (data not shown). STAT1 activation was dependent on the CAF concentration used; the activity was detectable at a conditioned medium concentration of 1 to 10% but was 10- to 20-fold greater when the concentration was increased to 50% (data not shown). CAF-induced STAT1 DNA binding activity was also detectable in PBMC and in U1, HeLa, and 2fTGH cells, under conditions in which CAF inhibited HIV-1 replication in the same cells (data not shown).

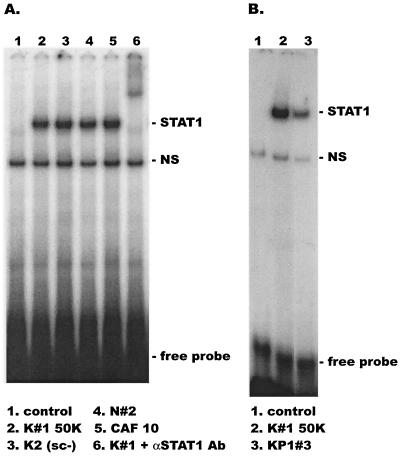

FIG. 3.

STAT1 activation is induced by CAF from different HVS-transformed CD8+-T-cell lines. 1G5 cells were treated for 15 min with a 50% concentration of conditioned medium from the indicated lines. Whole-cell extracts were prepared for EMSA using a 32P-labeled m67 GAS probe. The presence of STAT1 in the complexes was confirmed by adding anti-STAT1 antibody in a supershift experiment (panel A, lane 6).

Of note is that STAT1 activation was considerably weaker when 1G5 cells were treated with conditioned medium from the KP1#3 line than when medium from the K#1 50K line was used (Fig. 3B). The KP1#3 medium only weakly inhibited the replication of HIV-1 BaL in macrophages and had no inhibitory activity in the transient transfection assay. In contrast, medium from the K#1 50K line was an effective inhibitor in both assays (Fig. 1A and 2C).

The activation of other STAT proteins was studied by EMSA or by Western blot analysis using antibodies specific to tyrosine phosphorylated STAT3 or STAT5. STAT3 activation as a response to CAF was not detected in PBMC, U1, HeLa, or 2fTGH cells; STAT5 activation was detectable in PBMC, but not in the other cells (data not shown).

Overall, these experiments suggest that activation of STAT1 correlates with CAF-mediated inhibition of HIV-1 LTR activation and of HIV-1 replication.

Interferons do not mediate CAF inhibition of HIV-1 LTR activation.

The STAT1 protein is known to be activated by IFNs; indeed, STAT1 was first identified in IFN-stimulated cells (77). Neither IFN-α nor IFN-β was detected in any of the CD8+-T-cell-conditioned media using ELISAs with assay sensitivity limits of 10 and 3 pg/ml, respectively (data not shown) (62). Although IFN-γ was detectable, there was no correlation between its concentration and inhibition of HIV-1 replication by the same conditioned media. Thus, the inhibitory medium from the K#1 50K line and the noninhibitory medium from the KP1#3 line contained the highest IFN-γ concentrations, 73.7 and 112 ng/ml, respectively, while the other inhibitory media, N#2 and CAF10, contained significantly lower IFN-γ levels of 13.3 and 16.6 ng/ml, respectively.

The above results suggest that preexisting IFNs were not contributing to the anti-HIV-1 activity of the conditioned media. However, it seemed possible that a component(s) of the conditioned media might stimulate the cells to secrete IFNs, which could then inhibit HIV-1 LTR activation and replication in an autocrine or paracrine manner. To test this hypothesis, neutralizing antibodies against IFN-α, IFN-β, or IFN-γ were added to see whether this could reverse the inhibitory effect of the conditioned medium on HIV-1 LTR activation in HeLa cells.

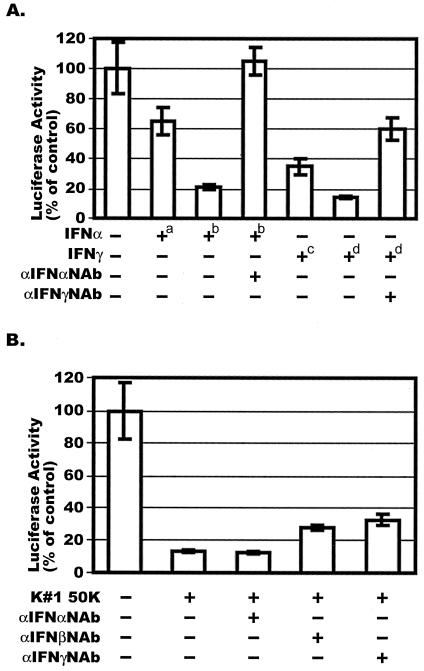

We first determined the effects of IFNs on HIV-1 LTR activation. Both IFN-α and IFN-γ were able to inhibit the activation of the HIV-1 LTR by PMA; IFN-α reduced activation by 35 and 75% at concentrations of 100 and 1,000 U/ml, respectively (Fig. 4, panel A, columns 2 and 3). The addition of antibodies against IFN-α (1,000 U/ml) completely reversed this inhibition (Fig. 4, panel A, column 4). IFN-γ inhibited PMA-induced HIV-1 LTR activation by 65 and 85% at concentrations of 20 and 200 ng/ml, respectively (Fig. 4, panel A, columns 5 and 6). Antibodies against IFN-γ partially reversed the inhibitory effect of 200-ng/ml IFN-γ (Fig. 4, panel A, column 7). IFN-β and anti-IFN-β were not tested in this experiment. Antibodies to IFN-β and IFN-γ, but not the antibody to IFN-α, modestly reversed the CAF-mediated inhibition of PMA-induced HIV-1 LTR activation, with the anti-IFN-γ antibody having the greater, but still weak, effect (Fig. 4B).

FIG. 4.

Effect of CAF on PMA-induced HIV-1 LTR activation in the presence of neutralizing antibodies against IFN-α, IFN-β, or IFN-γ. (A) HeLa cells were transiently transfected with the HIV-LTR-Luc plasmid and then treated with 100 U (+a) or 1,000 U (+b) of IFN-α per ml or 20 ng (+c) or 200 ng (+d) of IFN-γ per ml for 16 h. Neutralizing antibodies, when present (dilution of stocks,1:250), were incubated with the IFN stocks for 30 min at 37°C before addition of the mixture to the cells. Luciferase activities were measured after stimulation of the cells with PMA for 8 h. (B) The experiment was performed as described for panel A except that CAF (50% conditioned medium from line K#1 50K) replaced the IFNs. The results (mean ± standard error) are presented as histograms. They represent luciferase activity compared to the value derived from cells not treated with CAF or IFN, which was defined as 100%. This corresponded to absolute r.l.u. values of 2,140 ± 374.

Taken together, these results suggest that IFN-α, IFN-β, and IFN-γ, acting independently, are unlikely to play a significant role, directly or otherwise, in the inhibition of HIV-1 LTR activation by CAF.

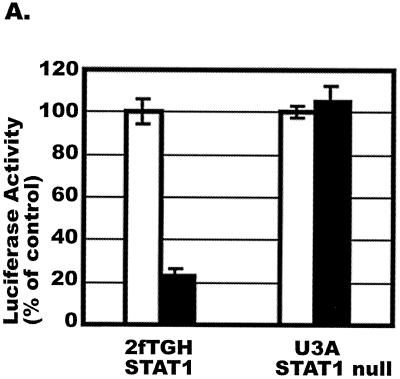

The inhibitory effect of CAF on HIV-1VSV infection is abolished in STAT1-deficient cells.

To obtain direct evidence for an involvement of STAT1 in CAF-mediated HIV-1 LTR activation, we used the STAT1-deficient cell line U3A and its parental, STAT1-expressing cell line 2fTGH (58). The U3A and 2fTGH cells were incubated with and without a 50% concentration of conditioned medium from the K#1 50K line for 16 h prior to infection of the cells with luciferase-expressing HIV-1VSV. CAF inhibited HIV-1VSV infection of the 2fTGH cells but had no effect on infection of the STAT1-deficient U3A cells (Fig. 5A).

FIG. 5.

Effects of CAF on HIV-1VSV replication and STAT1 activation in U3A and 2fTGH cells. (A) 2fTGH (STAT1-expressing) and U3A (STAT1-null) cells were incubated with (solid bar) or without (open bar) a 50% concentration of CAF (K#1 50K clone) for 16 h before infection with HIV-1VSV. The results (mean ± standard error) from triplicate determinations in a single experiment are presented as histograms. Similar results were obtained in two other independent experiments. The values represent luciferase activity compared to that derived from cells not treated with CAF, which was defined as 100%. This corresponded to absolute r.l.u. values of 11,391 ± 393 for 2fTGH and 18,600 ± 500 for U3A. The average background r.l.u. value was 1.5. (B) U3A and 2fTGH cells were treated with 50% CAF (K#1 50K clone) for 15 min before whole-cell extracts were prepared for EMSA using a 32P-labeled m67 GAS probe.

To assess whether CAF could activate STAT1 DNA binding activities in U3A and 2fTGH cells, whole-cell extracts were prepared after treatment of the cells for 15 min with conditioned medium (50%) from the K#1 50K line and then analyzed by EMSA. CAF-mediated STAT1 DNA binding activity was observed in the parental 2fTGH cells, but not in the U3A cells (Fig. 5B). Together, these experiments suggest an important role for STAT1 in the inhibitory effect of CAF on HIV-1 LTR activation.

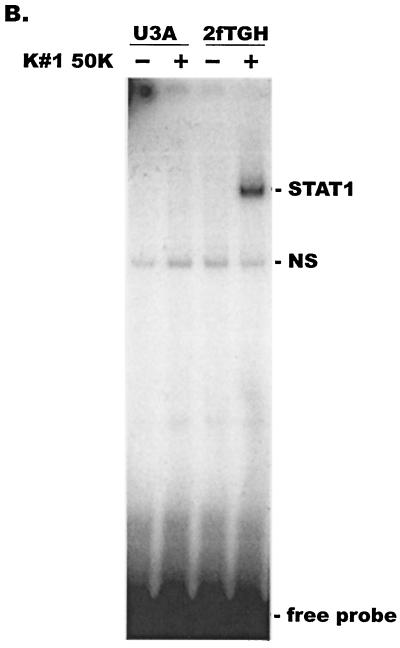

Expression of a dominant negative STAT1 protein inhibits the effect of CAF on the HIV-1 LTR, and expression of wild-type STAT1 restores CAF-sensitivity to STAT1-deficient cells.

To further analyze the role of STAT1 in the CAF-mediated inhibition of HIV-1 replication, we used a STAT1 dominant negative mutant (26). Phosphorylation of tyrosine residue 701 is essential for STAT1 activation; STAT1 proteins with a phenylalanine substitution at this position (Y701F) can be neither phosphorylated nor activated (82). Moreover, the overexpression of the STAT1 Y701F mutant has a dominant negative effect on the activation of the wild-type STAT1 protein.

HeLa cells were cotransfected with a plasmid containing the HIV-LTR-Luc construct together with one expressing either no STAT1 (empty vector), the wild-type STAT1 protein, or the STAT1 Y701F mutant. The cells were treated with a 50% concentration of CAF (K#1 50K line) for 16 h and then stimulated with PMA for 8 h before measurement of luciferase expression. HIV-1 LTR activity was, unexpectedly, enhanced 5.7- and 8-fold in the cells that overexpressed the STAT1 and STAT1 Y701F proteins, respectively, in the absence of CAF (Fig. 6, lanes 2 and 3). As expected, CAF inhibited LTR activation both in cells expressing the transfected wild-type STAT1 protein and in cells transfected with the control vector, which still express endogenous STAT1 (Fig. 6A, lanes 4 and 5). However, LTR activation was restored only in the CAF-treated cells that expressed the dominant negative STAT1 Y701F protein (Fig. 6A, lane 6). Luciferase expression from the HIV-1 LTR was enhanced by the STAT1 Y701F protein, albeit to a lesser extent than in the absence of CAF (compare lanes 3 and 6). The inhibitory effect of CAF on LTR activation was not completely reversed in cells expressing STAT1 Y701F (lane 6), probably because the plasmid transfection efficiency in HeLa cells is limited. Indeed, a low level of tyrosine phosphorylated STAT1 was still detectable in HeLa cells transiently transfected with STAT1 Y701F (data not shown). Taken together, these results suggest that STAT1 must become phosphorylated to be involved in the inhibition of HIV-1 LTR activation by CAF. Whether STAT1-independent mechanisms are also involved remains to be determined, but this is clearly possible.

FIG. 6.

Effects of CAF on HIV-1 LTR activation in HeLa and U3A cells expressing a dominant negative STAT1 protein. (A) HeLa cells were transiently transfected with a plasmid expressing HIV-LTR-Luc and one expressing either no STAT1 (vector control), wild-type STAT1, or the STAT1 Y701F dominant negative mutant (STAT1 DN), as indicated. The transfected cells were then treated with CAF (50% concentration; K#1 50K line) for 16 h before PMA stimulation for 8 h and measurement of luciferase activity. (B) A similar experiment was performed using U3A (STAT1-null) cells. The results (mean ± standard error) from triplicate determinations in a single experiment are presented as histograms. Similar results were obtained in another independent experiment. The values represent luciferase activity compared to that derived from cells not treated with CAF, which was defined as 100%. This corresponded to absolute r.l.u. values of 1,850 ± 50 for HeLa cells and 4,650 ± 13 for U3A cells.

We extended the previous results by transfecting the STAT1-deficient U3A cells with a plasmid encoding either no STAT1, STAT1, or the STAT1 Y701F mutant in addition to the HIV-LTR-Luc plasmid. The effect of CAF was then assayed as described above. The reintroduction of STAT1 into the U3A cells restored the ability of CAF to inhibit PMA-induced HIV-1 LTR activation, whereas the STAT1 Y701F mutant had no such effect (Fig. 6B). This confirms that the inhibitory effect of CAF on HIV-1 LTR activation is mediated by tyrosine phosphorylation of STAT1. The overexpression of the STAT1 Y701F protein modestly enhanced HIV-1 LTR activation in U3A cells, whether or not CAF was present (Fig. 6B, lanes 3 and 6), just as it did in HeLa cells (Fig. 6A). However, enhancement of HIV-1 LTR activity was not observed in U3A cells transfected with STAT1 alone (Fig. 6B, lanes 1 and 2).

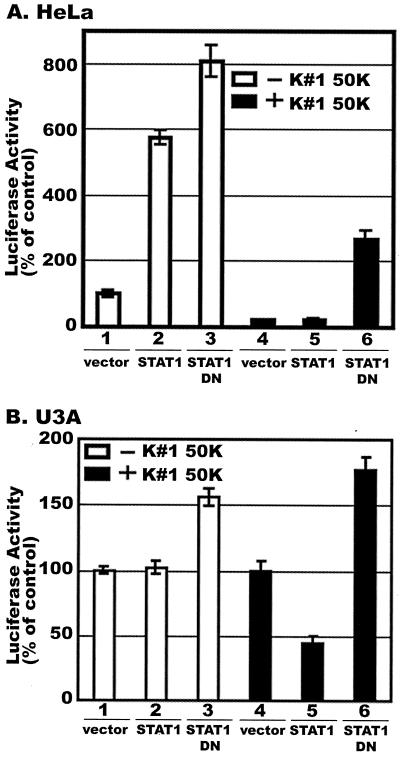

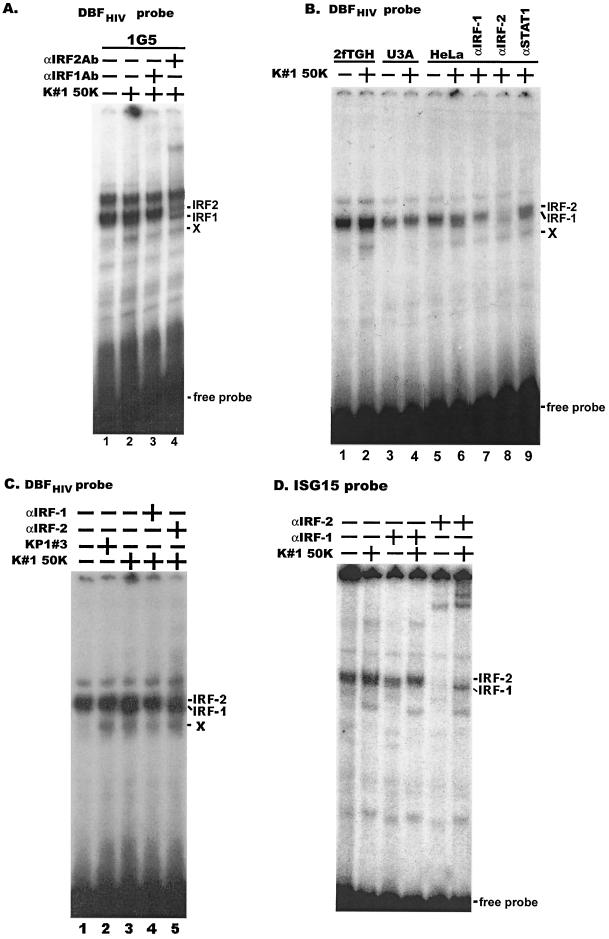

CAF-mediated IRF-1 protein induction is STAT1 dependent.

The expression of IRF-1 can be induced by interferons acting through STAT1 (22, 51), as well as by many other stimuli (reviewed in references 25, 84, and 85). The HIV-1 LTR promoter contains a DBF site for IRF proteins, and both IRF-1 and IRF-2 (but not STAT1) can bind to DBF sites (93). We therefore examined whether CAF could affect the abilities of IRF-1 and IRF-2 to bind to the HIV-1 DBF site.

Whole-cell extracts were prepared from several different cell lines treated with CAF for 16 h. The IRF-1 and IRF-2 DNA binding activities were analyzed by EMSA using a 32P-labeled oligonucleotide containing the HIV-1 DBF site. Since complexes containing IRF-1 migrate just slightly faster than those containing IRF-2, broadening of the unresolved doublet at its bottom edge or top edge, respectively, indicates induction of one or the other protein. The DNA binding activity of IRF-1 was induced by CAF in 1G5, 2fTGH, and HeLa cells (Fig. 7). In each of these cell lines, CAF inhibits HIV-1 LTR activation (Fig. 2 and 5A). However, no IRF-1 binding to the DBF site was observed when CAF was added to the STAT1-deficient U3A cells (Fig. 7B, lanes 3 and 4). In these cells, CAF neither inhibits transcription from the HIV-1 LTR (Fig. 5A) nor induces STAT1 (Fig. 5B). In contrast to what was observed with IRF-1, IRF-2 constitutively bound to the HIV-1 LTR DBF site, both in the presence and absence of CAF (Fig. 7).

FIG. 7.

IRF-1 was induced and bound to DBF sites within the HIV-1 LTR as a response to CAF. Different cell lines (A, 1G5; B, 2fTGH, U3A, and HeLa) were treated with CAF (50% concentration; K#1 50K line) for 16 h. Whole-cell extracts were prepared for EMSA using a 32P-labeled HIV-1 DBF probe. The composition of protein complexes was further assessed by adding anti-IRF-1, anti-IRF-2 or anti-STAT1 antibodies in a supershift experiment, as indicated. (C) HeLa cells were treated with conditioned media (50% concentration) from lines KP1#3 and K#1 50K, as indicated. Anti-IRF-1 or anti-IRF-2 antibodies were added in a supershift experiment, as indicated. X denotes a complex of unknown composition that is induced by all conditioned media, irrespective of the presence of CAF activity (see text). (D) Whole-cell extracts from 1G5 cells treated with CAF (50% concentration; K1 50K line) were analyzed by EMSA using a 32P-labeled ISG15 probe. Anti-IRF-1 or anti-IRF-2 antibodies were added in a supershift experiment, as indicated.

The identities of IRF-1 and IRF-2 were confirmed by performing a supershift assay using specific antibodies (Fig. 7A, lanes 3 and 4, and B, lanes 7 and 8). Further confirmation of the identity of IRF-1 was obtained by performing an EMSA with the well-characterized IRF-1 probe, ISG15, and specific antibodies in a supershift analysis (Fig. 7D). An additional, unknown protein complex (designated X in Fig. 7) was also induced by CAF; a supershift assay using antibodies to STAT1 failed to detect STAT1 in this complex. STAT1 was also absent from the IRF1 and IRF2 complexes identified using the HIV-1 DBF probe (Fig. 7B, lane 9; also data not shown).

Finally, IRF-1 DNA binding activity levels in HeLa cells treated with conditioned medium from the KP1#3 line, which contains little or no transcriptional inhibitory activity, and those in HeLa cells treated with conditioned medium from the K#1 50K line, which contains significant transcriptional inhibitory activity, were compared (Fig. 1A and 2C). IRF-1 binding to the DBF site was induced by the medium from the K#1 50K line, but not by the medium from the KP1#3 line (Fig. 7C). Thus, there is a correlation between the induction of IRF-1 DNA binding activity and CAF activity. Each of the conditioned media induced the binding of complex X to the DBF probe (Fig. 7). The identity of complex X remains to be determined, although it is not STAT1, IRF-1, or IRF-2, based on supershift analyses (Fig. 7 and data not shown). In contrast to the DNA binding of IRF-1 that was induced only in response to CAF, the DBF binding of complex X was induced by conditioned media from both the K#1 50K and KP1#3 lines. Since conditioned media from the latter line lacks significant CAF activity, there is no correlation between complex X binding and CAF activity (Fig. 7C). Taken together, our experiments suggest that IRF-1 is induced by CAF and that this IRF-1 induction is STAT1 dependent.

DISCUSSION

The importance of the cell-mediated immune response for the partial control of HIV-1 infection is now well appreciated. One component of this response is the secretion of an antiviral factor(s) from CD8+ T cells (50, 87). This may not be a specific response to HIV-1 but is perhaps a more general reflection of how the immune system responds to viral pathogens. The identity of this factor(s), commonly known as CAF, is still not clear well over a decade after its presence was first inferred (95, 100). Although CC-chemokines contribute to the overall HIV-1-suppressive activity released from CD8+ T cells, these entry-blocking inhibitors cannot account for all the known properties of CAF, which includes the ability to prevent HIV-1 replication postentry (16, 19, 47, 54, 62, 63, 89). Here again, there may be multiple points in the viral life cycle at which one or more components of CAF can act, including prior to integration and at the transcriptional stage (16, 19, 47, 54, 89). Our approach to the problems of what CAF is and how it acts has been to try to identify what signaling pathways are activated by CAF, in the hope that this may yield information on the nature of the active component(s). To this end, we have used experimental systems that are not susceptible to a blockade by CAF at the level of viral entry (HIV-1VSV pseudotypes and PMA-induced HIV-1 LTR activation). As a source of CAF, we have used conditioned media from several HSV-transformed CD8+-T-cell lines.

In these studies, we have found that CAF induces STAT1 activation and that this is correlated with the inhibition of HIV-1 LTR-directed transcription. The activation of STAT1 by CAF was observed for several cell lines in response to several sources of CAF, but it did not occur in a STAT1-defective cell line, and it did not occur in response to conditioned medium from a CD8+-T-cell line that did not inhibit LTR-mediated transcription and only weakly inhibited HIV-1 replication. We suggest that STAT1 activation is a common pathway for the suppression of HIV-1 transcription and replication in the response to at least one component of CAF.

Tyrosine phosphorylated, activated STAT1 may not block HIV-1 LTR transcription directly; there is no evidence that STAT1 can bind to the LTR. It also remains to be determined whether the introduction of constitutive, activated STAT1 can bypass the need for CAF treatment and whether this is sufficient to block HIV-1 LTR transcription. Despite these uncertainties, we favor a model in which activated STAT1 induces downstream gene products that are required to down-regulate transcription. Our support for this model is based on indirect evidence: we observed no inhibitory effect of CAF on HIV-1 LTR transcription when the target cells were treated with CAF and PMA simultaneously for 8 h, but inhibition was observed when the cells were treated with CAF for 16 h prior to PMA addition (Fig. 2). In addition, treatment of HeLa cells with CAF for 8 h, initiated 40 h after transfection, did not inhibit Tat-mediated HIV-1 LTR transcription (data not shown). This implies that CAF action may require a significant period of time for the up-regulation of inhibitory factors that must act prior to PMA- or Tat-mediated induction of LTR transcription. However, because pretreatment of cells with CAF before infection with HIV-1VSV in the absence of CAF was sufficient for inhibition of viral replication to be seen several hours later, whatever effect CAF has on the cells to create this resistant state must be quite durable.

We showed that the binding of IRF-1, a STAT1-regulated immediate-response gene, to the HIV-1 LTR was up-regulated in several different cell lines exposed to CAF for 16 h (Fig. 7). Induction of IRF-1 binding to the LTR was not detectable within 30 min (data not shown), suggesting that this was not an immediate response to CAF. However, IRF-1 induction was not observed in STAT1-defective U3A cells, and it did not occur in response to conditioned medium from the KP1#3 line that lacked transcriptional inhibitory activity. Thus, both temporally and in terms of specificity, there is an association between STAT1-mediated IRF-1 induction and the transcriptional inhibitory activity of CAF. IRF-1 may not, however, be the only factor involved in inhibition of HIV-1 LTR activity; STAT1 is known to activate many other genes involved in gene regulation (14, 73).

We have shown that STAT1 activation is directly involved in the inhibition of HIV-1 transcription by CAF. However, whether a STAT1-independent pathway is also involved remains to be determined. Other transcription factors such as NF-κB and NFAT have been reported to be associated with CAF activities (19, 20). Our preliminary analysis has indicated that NF-κB could be activated by conditioned medium from some CD8+-T-cell lines but that there was no obligatory correlation between NF-κB activation and CAF activity (data not shown). In other preliminary studies, we have observed neither NFAT activation by CAF in 1G5 cells nor the involvement of p38 MAPK and SAPK/JNK signaling pathways in CAF signaling. STAT5 may, however, play a role in CAF-mediated inhibition of HIV-1 LTR activity, because in preliminary experiments, we observed STAT5 activation in CAF-treated PBMC (data not shown). Of note is that both STAT1 and STAT5 are constitutively activated in HIV-1-infected patients, and IL-2 and azidothymidine both enhance STAT5 expression and activation (5, 6). Further studies are required to more fully investigate the involvement of STAT5 in CAF activity.

STAT proteins are known to associate with other transcriptional factors such as SP1 (52) and with coactivator proteins such as the CREB-binding proteins (CBP)/p300 (57, 65, 67, 101, 102). Furthermore, STAT5 inhibits NF-κB-mediated signaling by squelching the limiting coactivators CBP/p300 (53). The activation of STAT2 by IFN-α inhibits NF-κB-mediated HIV-1 LTR transcription in the TNF-α signaling pathway, by competing directly for p300 binding (34). Investigating the functions of these transcriptional factors and studying the competitive binding of transcriptional factors to p300 may therefore help to further reveal how CAF inhibits HIV-1 replication. Moreover, both p300 and the p300/CBP associating factor can form an intracellular complex with the HIV-1 Tat protein (3), which may be relevant to any role these factors play in CAF activity. Thus, it is possible that CAF-mediated STAT1 activation could inhibit HIV-1 transcription by competing with viral transcriptional factors such as Tat for a limited supply of coactivators. Although CAF-mediated STAT1 activation inhibits HIV-1 LTR activation in both the absence and the presence of Tat in HeLa cells (Fig. 2 and data not shown), we cannot exclude the possibility of a role for Tat after STAT1 activation in primary T cells or macrophages.

Unexpectedly, we observed that the expression of either unphosphorylated STAT1 or a STAT1 dominant negative mutant significantly enhanced HIV-1 LTR activation in response to PMA (Fig. 6). Further studies are required in order to understand how this occurs. Recently, a novel function of STAT1 has been identified, which is that unphosphorylated STAT1 forms a complex with IRF-1 to support LMP2 expression (14). LMP2 is a subunit of the 20S proteosome which processes viral and tumor antigens for presentation to CD8+ T cells in the context of major histocompatibility complex class I (46). In addition, the adenovirus E1A protein can interfere with the formation of the proteosome complex by occupying domains of STAT1 that bind to IRF-1; this leads to down-regulation of LMP2 transcription and interference with the presentation of viral antigens (13). Whether such pathways are relevant to our observations remains to be determined.

We have considered the possibility that one or more interferons might contribute to the CAF activity that we have been studying. The inhibitory effects of IFN-α and IFN-β on HIV-1 replication in PBMC, T-cell lines, and monocytoid cell lines have been demonstrated (8, 28, 32, 33, 40, 70, 80, 81), and IFN-γ has pleiotropic effects on HIV-1 replication in macrophage and T-cell lines (32, 39–41). Furthermore, the inhibitory effects of IFN-α and IFN-γ on retrovirus replication have been observed in both hu-PBL SCID mice (44) and rhesus macaques (29). Conditioned medium from PBMC stimulated with influenza A virus can inhibit HIV-1 replication prior to reverse transcription, and this antiviral activity is at least partially attributable to IFN-α (70). In our experiments, we observed modest inhibitory effects of exogenous IFN-α and IFN-γ on HIV-1 LTR activation (Fig. 4). The use of neutralizing antibodies showed that IFN-β and IFN-γ, but not IFN-α, may contribute moderately to CAF-mediated inhibition of HIV-1 LTR activation. However, the inhibitory actions of IFNs must be consequent to their paracrine induction in the target cells by another component(s) of CAF, because IFN-α was not detectable in the media added to target cell and the levels of IFN-γ in the media added to the target cells showed no correlation with inhibition. It is also possible that combinations of different IFNs, or of IFNs with other cytokines, may synergize in their inhibition of HIV-1 LTR activation and that such a combination effect could contribute to CAF activity.

A model of how CAF inhibits HIV-1 gene expression driven by the LTR might be that one or more components of CAF bind to its cognate receptor(s) and activate intracellular signaling pathways, including STAT1 phosphorylation. The activated STAT1 protein in turn induces the expression of IRF-1, which may then suppress HIV-1 transcription via an effect on the LTR, although this is speculative. IRF-2 may bind constitutively to the HIV-1 LTR DBP/IRF site in the absence or presence of CAF. It remains to be determined whether IRF-2 acts as a positive regulator and whether the increased binding of IRF-1 proteins to the shared DBP/IRF site leads to the inhibition of HIV-1 transcription. While IRF-1 is generally considered to be a positive regulator of transcription and IRF-2 a repressor, there are several examples of positive regulation by IRF-2 (reviewed in references 4, 36, 85, and 94). Thus, it is possible that IRF-1 might in some contexts be a repressor, either directly or by competition with IRF-2 in a scenario in which the latter is an activator. The paracrine secretion of other soluble factors in response to CAF, perhaps including IFNs that induce STAT1 activation and IRF-1 gene expression, may also be involved in the repression of HIV-1 transcription. Further studies to determine whether activated STAT1 competes with NF-κB for the binding of common coactivators and how unphosphorylated STAT1 enhances HIV-1 LTR activity may help to improve our knowledge of the molecular basis of the transcriptional inhibitory component of CAF.

Acknowledgments

We thank X.-Y. Fu, G. Stark, and R. Desrosiers for providing reagents; B. Xie, C. Spenlehauer, C. Gordon, and S. Kuhmann for helpful discussions; F. Lee and M. Paluch for technical assistance; and C. Nathan for critical review of the manuscript.

This work was funded by NIH grants R37 AI36082 and AI43698-03. J.P.M. is an Elizabeth Glaser Scientist of the Pediatric AIDS Foundation and a Stavros S. Niarchos Scholar. The Department of Microbiology and Immunology at the Weill Medical College gratefully acknowledges the support of the William Randolph Hearst Foundation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bailer, R. T., A. Holloway, J. Sun, J. B. Margolick, M. Martin, J. Kostman, and L. J. Montaner. 1999. IL-13 and IFN-gamma secretion by activated T cells in HIV-1 infection associated with viral suppression and a lack of disease progression. J. Immunol. 162:7534–7542. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barker, E., K. N. Bossart, and J. A. Levy. 1998. Primary CD8+ cells from HIV-infected individuals can suppress productive infection of macrophages independent of beta-chemokines. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:1725–1729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benkirane, M., R. F. Chun, H. Xiao, V. V. Ogryzko, B. H. Howard, Y. Nakatani, and K. T. Jeang. 1998. Activation of integrated provirus requires histone acetyltransferase: p300 and P/CAF are coactivators for HIV-1 Tat. J. Biol. Chem. 273:24898–24905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blanco, J. C., C. Contursi, C. A. Salkowski, D. L. DeWitt, K. Ozato, and S. N. Vogel. 2000. Interferon regulatory factor (IRF)-1 and IRF-2 regulate interferon gamma-dependent cyclooxygenase 2 expression. J. Exp. Med. 191:2131–2144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bovolenta, C., L. Camorali, A. L. Lorini, S. Ghezzi, E. Vicenzi, A. Lazzarin, and G. Poli. 1999. Constitutive activation of STATs upon in vivo human immunodeficiency virus infection. Blood 94:4202–4209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bovolenta, C., L. Camorali, M. Mauri, S. Ghezzi, S. Nozza, G. Tambussi, A. Lazzarin, and G. Poli. 2001. Expression and activation of a C-terminal truncated isoform of STAT5 (STAT5δ) following interleukin 2 administration or AZT monotherapy in HIV-infected individuals. Clin. Immunol. 99:75–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bovolenta, C., A. L. Lorini, B. Mantelli, L. Camorali, F. Novelli, P. Biswas, and G. Poli. 1999. A selective defect of IFN-gamma- but not of IFN-alpha-induced JAK/STAT pathway in a subset of U937 clones prevents the antiretroviral effect of IFN-gamma against HIV-1. J. Immunol. 162:323–330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brinchmann, J. E., G. Gaudernack, and F. Vartdal. 1991. In vitro replication of HIV-1 in naturally infected CD4+ T cells is inhibited by rIFN alpha 2 and by a soluble factor secreted by activated CD8+ T cells, but not by rIFN beta, rIFN gamma, or recombinant tumor necrosis factor-alpha. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 4:480–488. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bromberg, J., and J. E. Darnell. 2000. The role of STATs in transcriptional control and their impact on cellular function. Oncogene 19:2468–2473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carmichael, A., X. Jin, P. Sissons, and L. Borysiewicz. 1993. Quantitative analysis of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1)-specific cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) response at different stages of HIV-1 infection: differential CTL responses to HIV-1 and Epstein-Barr virus in late disease. J. Exp. Med. 177:249–256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Castro, B. A., C. M. Walker, J. W. Eichberg, and J. A. Levy. 1991. Suppression of human immunodeficiency virus replication by CD8+ cells from infected and uninfected chimpanzees. Cell Immunol. 132:246–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chang, T. L., X. Peng, and X. Y. Fu. 2000. Interleukin-4 mediates cell growth inhibition through activation of Stat1. J. Biol. Chem. 275:10212–10217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chatterjee-Kishore, M., F. van Den Akker, and G. R. Stark. 2000. Adenovirus E1A down-regulates LMP2 transcription by interfering with the binding of stat1 to IRF1. J. Biol. Chem. 275:20406–20411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chatterjee-Kishore, M., K. L. Wright, J. P. Ting, and G. R. Stark. 2000. How Stat1 mediates constitutive gene expression: a complex of unphosphorylated Stat1 and IRF1 supports transcription of the LMP2 gene. EMBO J. 19:4111–4122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen, B. K., K. Saksela, R. Andino, and D. Baltimore. 1994. Distinct modes of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 proviral latency revealed by superinfection of nonproductively infected cell lines with recombinant luciferase-encoding viruses. J. Virol. 68:654–660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen, C. H., K. J. Weinhold, J. A. Bartlett, D. P. Bolognesi, and M. L. Greenberg. 1993. CD8+ T lymphocyte-mediated inhibition of HIV-1 long terminal repeat transcription: a novel antiviral mechanism. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 9:1079–1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cocchi, F., A. L. DeVico, A. Garzino-Demo, S. K. Arya, R. C. Gallo, and P. Lusso. 1995. Identification of RANTES, MIP-1 alpha, and MIP-1 beta as the major HIV-suppressive factors produced by CD8+ T cells. Science 270:1811–1815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Connor, R. I., K. E. Sheridan, D. Ceradini, S. Choe, and N. R. Landau. 1997. Change in coreceptor use correlates with disease progression in HIV-1-infected individuals. J. Exp. Med. 185:621–628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Copeland, K. F., P. J. McKay, and K. L. Rosenthal. 1995. Suppression of activation of the human immunodeficiency virus long terminal repeat by CD8+ T cells is not lentivirus specific. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 11:1321–1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Copeland, K. F., P. J. McKay, and K. L. Rosenthal. 1996. Suppression of the human immunodeficiency virus long terminal repeat by CD8+ T cells is dependent on the NFAT-1 element. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 12:143–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Darnell, J. E. 1997. STATs and gene regulation. Science 277:1630–1635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Darnell, J. E., I. M. Kerr, and G. R. Stark. 1994. Jak-STAT pathways and transcriptional activation in response to IFNs and other extracellular signaling proteins. Science 264:1415–1421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dragic, T., V. Litwin, G. P. Allaway, S. R. Martin, Y. Huang, K. A. Nagashima, C. Cayanan, P. J. Maddon, R. A. Koup, J. P. Moore, and W. A. Paxton. 1996. HIV-1 entry into CD4+ cells is mediated by the chemokine receptor CC-CKR-5. Nature 381:667–673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ferbas, J. 1998. Perspectives on the role of CD8+ cell suppressor factors and cytotoxic T lymphocytes during HIV infection. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 14:S153–S160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fu, X. Y. 1995. A direct signaling pathway through tyrosine kinase activation of SH2 domain-containing transcription factors. J. Leukoc. Biol. 57:529–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fu, X. Y. 1992. A transcription factor with SH2 and SH3 domains is directly activated by an interferon alpha-induced cytoplasmic protein tyrosine kinase(s). Cell 70:323–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fu, X. Y., C. Schindler, T. Improta, R. Aebersold, and J. E. Darnell. 1992. The proteins of ISGF-3, the interferon alpha-induced transcriptional activator, define a gene family involved in signal transduction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89:7840–7843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gendelman, H. E., L. M. Baca, J. Turpin, D. C. Kalter, B. Hansen, J. M. Orenstein, C. W. Dieffenbach, R. M. Friedman, and M. S. Meltzer. 1990. Regulation of HIV replication in infected monocytes by IFN-alpha. Mechanisms for viral restriction. J. Immunol. 145:2669–2676. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Giavedoni, L., S. Ahmad, L. Jones, and T. Yilma. 1997. Expression of gamma interferon by simian immunodeficiency virus increases attenuation and reduces postchallenge virus load in vaccinated rhesus macaques. J. Virol. 71:866–872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grene, E., L. A. Pinto, S. S. Cohen, C. Mac Trubey, M. T. Trivett, T. B. Simonis, D. J. Liewehr, S. M. Steinberg, and G. M. Shearer. 2001. Generation of alloantigen-stimulated anti-human immunodeficiency virus activity is associated with HLA-A*02 expression. J. Infect. Dis. 183:409–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Harrer, T., E. Harrer, S. A. Kalams, T. Elbeik, S. I. Staprans, M. B. Feinberg, Y. Cao, D. D. Ho, T. Yilma, A. M. Caliendo, R. P. Johnson, S. P. Buchbinder, and B. D. Walker. 1996. Strong cytotoxic T cell and weak neutralizing antibody responses in a subset of persons with stable nonprogressing HIV type 1 infection. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 12:585–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hartshorn, K. L., D. Neumeyer, M. W. Vogt, R. T. Schooley, and M. S. Hirsch. 1987. Activity of interferons alpha, beta, and gamma against human immunodeficiency virus replication in vitro. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 3:125–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Honda, Y., L. Rogers, K. Nakata, B. Y. Zhao, R. Pine, Y. Nakai, K. Kurosu, W. N. Rom, and M. Weiden. 1998. Type I interferon induces inhibitory 16-kD CCAAT/enhancer binding protein (C/EBP) beta, repressing the HIV-1 long terminal repeat in macrophages: pulmonary tuberculosis alters C/EBP expression, enhancing HIV-1 replication. J. Exp. Med. 188:1255–1265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hottiger, M. O., L. K. Felzien, and G. J. Nabel. 1998. Modulation of cytokine-induced HIV gene expression by competitive binding of transcription factors to the coactivator p300. EMBO J. 17:3124–3134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Imada, K., and W. J. Leonard. 2000. The Jak-STAT pathway. Mol. Immunol. 37:1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jesse, T. L., R. LaChance, M. F. Iademarco, and D. C. Dean. 1998. Interferon regulatory factor-2 is a transcriptional activator in muscle where it regulates expression of vascular cell adhesion molecule-1. J. Cell Biol. 140:1265–1276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kaul, R., F. A. Plummer, J. Kimani, T. Dong, P. Kiama, T. Rostron, E. Njagi, K. S. MacDonald, J. J. Bwayo, A. J. McMichael, and S. L. Rowland-Jones. 2000. HIV-1-specific mucosal CD8+ lymphocyte responses in the cervix of HIV-1-resistant prostitutes in Nairobi. J. Immunol. 164:1602–1611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kitai, R., M. L. Zhao, N. Zhang, L. L. Hua, and S. C. Lee. 2000. Role of MIP-1β and RANTES in HIV-1 infection of microglia: inhibition of infection and induction by IFNβ. J. Neuroimmunol. 110:230–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kornbluth, R. S., P. S. Oh, J. R. Munis, P. H. Cleveland, and D. D. Richman. 1989. Interferons and bacterial lipopolysaccharide protect macrophages from productive infection by human immunodeficiency virus in vitro. J. Exp. Med. 169:1137–1151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kornbluth, R. S., P. S. Oh, J. R. Munis, P. H. Cleveland, and D. D. Richman. 1990. The role of interferons in the control of HIV replication in macrophages. Clin. Immunol. Immunopathol. 54:200–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Koyanagi, Y., W. A. O’Brien, J. Q. Zhao, D. W. Golde, J. C. Gasson, and I. S. Chen. 1988. Cytokines alter production of HIV-1 from primary mononuclear phagocytes. Science 241:1673–1675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kuroda, M. J., J. E. Schmitz, W. A. Charini, C. E. Nickerson, M. A. Lifton, C. I. Lord, M. A. Forman, and N. L. Letvin. 1999. Emergence of CTL coincides with clearance of virus during primary simian immunodeficiency virus infection in rhesus monkeys. J. Immunol. 162:5127–5133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lacey, S. F., K. J. Weinhold, C. H. Chen, C. McDanal, C. Oei, and M. L. Greenberg. 1998. Herpesvirus saimiri transformation of HIV type 1 suppressive CD8+ lymphocytes from an HIV type 1-infected asymptomatic individual. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 14:521–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lapenta, C., S. M. Santini, E. Proietti, P. Rizza, M. Logozzi, M. Spada, S. Parlato, S. Fais, P. M. Pitha, and F. Belardelli. 1999. Type I interferon is a powerful inhibitor of in vivo HIV-1 infection and preserves human CD4+ T cells from virus-induced depletion in SCID mice transplanted with human cells. Virology 263:78–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Le Borgne, S., M. Fevrier, C. Callebaut, S. P. Lee, and Y. Riviere. 2000. CD8+-cell antiviral factor activity is not restricted to human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-specific T cells and can block HIV replication after initiation of reverse transcription. J. Virol. 74:4456–4464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lehner, P. J., and J. Trowsdale. 1998. Antigen presentation: coming out gracefully. Curr. Biol. 8:R605–R608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Leith, J. G., K. F. Copeland, P. J. McKay, D. Bienzle, C. D. Richards, and K. L. Rosenthal. 1999. T cell-derived suppressive activity: evidence of autocrine noncytolytic control of HIV type 1 transcription and replication. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 15:1553–1561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Leith, J. G., K. F. Copeland, P. J. McKay, C. D. Richards, and K. L. Rosenthal. 1997. CD8+ T-cell-mediated suppression of HIV-1 long terminal repeat-driven gene expression is not modulated by the CC chemokines RANTES, macrophage inflammatory protein (MIP)-1 alpha and MIP-1 beta. AIDS 11:575–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Letvin, N. L. 1998. What immunity can protect against HIV infection. J. Clin. Investig. 102:1643–1644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Levy, J. A., C. E. Mackewicz, and E. Barker. 1996. Controlling HIV pathogenesis: the role of the noncytotoxic anti-HIV response of CD8+ T cells. Immunol. Today 17:217–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Li, X., S. Leung, S. Qureshi, J. E. Darnell, and G. R. Stark. 1996. Formation of STAT1-STAT2 heterodimers and their role in the activation of IRF-1 gene transcription by interferon-alpha. J. Biol. Chem. 271:5790–5794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Look, D. C., M. R. Pelletier, R. M. Tidwell, W. T. Roswit, and M. J. Holtzman. 1995. Stat1 depends on transcriptional synergy with Sp1. J. Biol. Chem. 270:30264–30267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Luo, G., and L. Yu-Lee. 2000. Stat5b inhibits NFκB-mediated signaling. Mol. Endocrinol. 14:114–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mackewicz, C. E., D. J. Blackbourn, and J. A. Levy. 1995. CD8+ T cells suppress human immunodeficiency virus replication by inhibiting viral transcription. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:2308–2312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mackewicz, C. E., H. W. Ortega, and J. A. Levy. 1991. CD8+ cell anti-HIV activity correlates with the clinical state of the infected individual. J. Clin. Investig. 87:1462–1466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mackewicz, C. E., B. K. Patterson, S. A. Lee, and J. A. Levy. 2000. CD8+ cell noncytotoxic anti-human immunodeficiency virus response inhibits expression of viral RNA but not reverse transcription or provirus integration. J. Gen. Virol. 5:1261–1264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.McDonald, C., and N. C. Reich. 1999. Cooperation of the transcriptional coactivators CBP and p300 with Stat6. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 19:711–722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.McKendry, R., J. John, D. Flavell, M. Muller, I. M. Kerr, and G. R. Stark. 1991. High-frequency mutagenesis of human cells and characterization of a mutant unresponsive to both alpha and gamma interferons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 88:11455–11459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.McMichael, A. 1998. T cell responses and viral escape. Cell 93:673–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.McMichael, A. J., G. Ogg, J. Wilson, M. Callan, S. Hambleton, V. Appay, T. Kelleher, and S Rowland-Jones. 2000. Memory CD8+ T cells in HIV infection. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 355:363–367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Moriuchi, H., M. Moriuchi, C. Combadiere, P. M. Murphy, and A. S. Fauci. 1996. CD8+ T-cell-derived soluble factor(s), but not beta-chemokines RANTES, MIP-1 alpha, and MIP-1 beta, suppress HIV-1 replication in monocyte/macrophages. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:15341–15345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mosoian, A., A. Teixeira, E. Caron, J. Piwoz, and M. E. Klotman. 2000. CD8+ cell lines isolated from HIV-1-infected children have potent soluble HIV-1 inhibitory activity that differs from beta-chemokines. Viral Immunol. 13:481–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mosoian, A. T., A. Klotman, and M. E. Klotman. 1997. Soluble HIV suppressive effects of herpesvirus saimiri-transformed CD8+ cells are distinct from RANTES, MIP-1α and MIP-1β, p.151–158. In Proceedings of Colloque des Cent Gardes, Retroviruses of Human AIDS and Related Animal Diseases. Elsevier, Paris, France.

- 64.Ogg, G. S., S. Kostense, M. R. Klein, S. Jurriaans, D. Hamann, A. J. McMichael, and F. Miedema. 1999. Longitudinal phenotypic analysis of human immunodeficiency virus type 1-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes: correlation with disease progression. J. Virol. 73:9153–9160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Paulson, M., S. Pisharody, L. Pan, S. Guadagno, A. L. Mui, and D. E. Levy. 1999. Stat protein transactivation domains recruit p300/CBP through widely divergent sequences. J. Biol. Chem. 274:25343–25349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Peruzzi, M., C. Azzari, M. E. Rossi, M. De Martino, and A. Vierucci. 2000. Inhibition of natural killer cell cytotoxicity and interferon gamma production by the envelope protein of HIV and prevention by vasoactive intestinal peptide. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 16:1067–1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pfitzner, E., R. Jahne, M. Wissler, E. Stoecklin, and B. Groner. 1998. p300/CREB-binding protein enhances the prolactin-mediated transcriptional induction through direct interaction with the transactivation domain of Stat5, but does not participate in the Stat5-mediated suppression of the glucocorticoid response. Mol. Endocrinol. 12:1582–1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pine, R. 1992. Constitutive expression of an ISGF2/IRF1 transgene leads to interferon-independent activation of interferon-inducible genes and resistance to virus infection. J. Virol. 66:4470–4478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Pine, R., T. Decker, D. S. Kessler, D. E. Levy, and J. E. Darnell. 1990. Purification and cloning of interferon-stimulated gene factor 2 (ISGF2): ISGF2 (IRF-1) can bind to the promoters of both beta interferon- and interferon-stimulated genes but is not a primary transcriptional activator of either. Mol. Cell. Biol. 10:2448–2457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Pinto, L. A., V. Blazevic, B. K. Patterson, C. Mac Trubey, M. J. Dolan, and G. M. Shearer. 2000. Inhibition of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication prior to reverse transcription by influenza virus stimulation. J. Virol. 74:4505–4511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Pitha, P. M. 1994. Multiple effects of interferon on the replication of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Antivir. Res. 24:205–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Qin, W., T. V. Golovkina, T. Peng, I. Nepomnaschy, V. Buggiano, I. Piazzon, and S. R. Ross. 1999. Mammary gland expression of mouse mammary tumor virus is regulated by a novel element in the long terminal repeat. J. Virol. 73:368–376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ramana, C. V., M. Chatterjee-Kishore, H. Nguyen, and G. R. Stark. 2000. Complex roles of Stat1 in regulating gene expression. Oncogene 19:2619–2627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Rosenberg, E. S., M. Altfeld, S. H. Poon, M. N. Phillips, B. M. Wilkes, R. L. Eldridge, G. K. Robbins, R. T. D’Aquila, P. J. Goulder, and B. D. Walker. 2000. Immune control of HIV-1 after early treatment of acute infection. Nature 407:523–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Rubbert, A., D. Weissman, C. Combadiere, K. A. Pettrone, J. A. Daucher, P. M. Murphy, and A. S. Fauci. 1997. Multifactorial nature of noncytolytic CD8+ T cell-mediated suppression of HIV replication: beta-chemokine-dependent and -independent effects. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 13:63–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sadowski, H. B., K. Shuai, J. E. Darnell, and M. Z. Gilman. 1993. A common nuclear signal transduction pathway activated by growth factor and cytokine receptors. Science 261:1739–1744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Schindler, C., X. Y. Fu, T. Improta, R. Aebersold, and J. E. Darnell. 1992. Proteins of transcription factor ISGF-3: one gene encodes the 91-and 84-kDa ISGF-3 proteins that are activated by interferon alpha. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89:7836–7839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Seidel, H. M., P. Lamb, and J. Rosen. 2000. Pharmaceutical intervention in the JAK/STAT signaling pathway. Oncogene 19:2645–2656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sepp, T., and S. E. Tong-Starksen. 1997. STAT1 pathway is involved in activation of caprine arthritis-encephalitis virus long terminal repeat in monocytes. J. Virol. 71:771–777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Shirazi, Y., and P. M. Pitha. 1992. Alpha interferon inhibits early stages of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication cycle. J. Virol. 66:1321–1328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Shirazi, Y., and P. M. Pitha. 1993. Interferon alpha-mediated inhibition of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 provirus synthesis in T-cells. Virology 193:303–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Shuai, K., G. R. Stark, I. M. Kerr, and J. E. Darnell. 1993. A single phosphotyrosine residue of Stat91 required for gene activation by interferon-gamma. Science 261:1744–1746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Takeda, K., and S. Akira. 2000. STAT family of transcription factors in cytokine-mediated biological responses. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 11:199–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Taniguchi, T. 1997. Transcription factors IRF-1 and IRF-2: linking the immune responses and tumor suppression. J. Cell. Physiol. 173:128–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Taniguchi, T., K. Ogasawara, A. Takaoka, and N. Tanaka. 2001. Irf family of transcription factors as regulators of host defense. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 19:623–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Thornton, A. M., R. M. Buller, A. L. DeVico, I. M. Wang, and K. Ozato. 1996. Inhibition of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 and vaccinia virus infection by a dominant negative factor of the interferon regulatory factor family expressed in monocytic cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:383–387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Tomaras, G. D., and M. L. Greenberg. 2001. CD8+ T cell mediated noncytolytic inhibition of human immunodeficiency virus type I. Front. Biosci. 1:D575–D598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Tomaras, G. D., and M. L. Greenberg. 2001. Mechanisms for HIV-1 entry: current strategies to interfere with this step. Curr. Infect. Dis. Rep. 3:93–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Tomaras, G. D., S. F. Lacey, C. B. McDanal, G. Ferrari, K. J. Weinhold, and M. L. Greenberg. 2000. CD8+ T cell-mediated suppressive activity inhibits HIV-1 after virus entry with kinetics indicating effects on virus gene expression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:3503–3508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Trkola, A., C. Gordon, J. Matthews, E. Maxwell, T. Ketas, L. Czaplewski, A. E. Proudfoot, and J. P. Moore. 1999. The CC-chemokine RANTES increases the attachment of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 to target cells via glycosaminoglycans and also activates a signal transduction pathway that enhances viral infectivity. J. Virol. 73:6370–6379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Trkola, A., A. B. Pomales, H. Yuan, B. Korber, P. J. Maddon, G. P. Allaway, H. Katinger, C. F. Barbas, D. R. Burton, D. D. Ho, et al. 1995. Cross-clade neutralization of primary isolates of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 by human monoclonal antibodies and tetrameric CD4-IgG. J. Virol. 69:6609–6617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Tsubota, H., C. I. Lord, D. I. Watkins, C. Morimoto, and N. L. Letvin. 1989. A cytotoxic T lymphocyte inhibits acquired immunodeficiency syndrome virus replication in peripheral blood lymphocytes. J. Exp. Med. 169:1421–1434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Van Lint, C., C. A. Amella, S. Emiliani, M. John, T. Jie, and E. Verdin. 1997. Transcription factor binding sites downstream of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 transcription start site are important for virus infectivity. J. Virol. 71:6113–6127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]