Abstract

Arginine-based endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-localization signals are sorting motifs that are involved in the biosynthetic transport of multimeric membrane proteins. After their discovery in the invariant chain of the major histocompatibility complex class II, several hallmarks of these signals have emerged. They occur in polytopic membrane proteins that are subunits of membrane protein complexes; the presence of the signal maintains improperly assembled subunits in the ER by retention or retrieval until it is masked as a result of heteromultimeric assembly. A distinct consensus sequence and their position independence with respect to the distal termini of the protein distinguish them from other ER-sorting motifs. Recognition by the coatomer (COPI) vesicle coat explains ER retrieval. Often, di-leucine endocytic signals occur close to arginine-based signals. Recruitment of 14-3-3 family or PDZ-domain proteins can counteract ER-localization activity, as can phosphorylation. This, and the occurrence of arginine-based signals in alternatively spliced regions, implicates them in the regulated surface expression of multimeric membrane proteins in addition to their function in quality control.

Keywords: peptide sorting motifs, transport signals, ion channels, quality control, COPI coat

Introduction

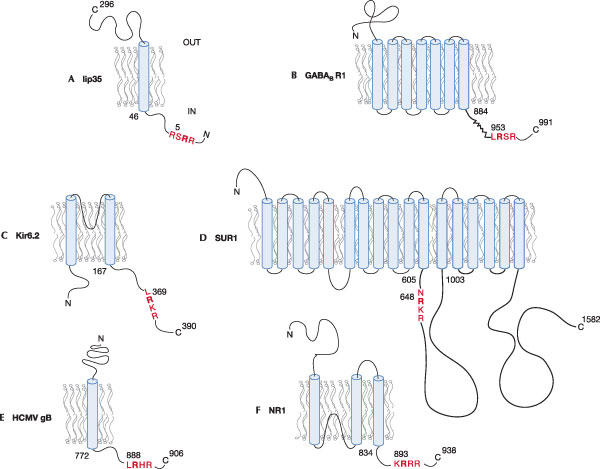

Subcellular compartments and the regulation of traffic between them allow the cell to separate important events. For example, in the secretory pathway, quality control of newly synthesized proteins occurs before downstream processing reactions take place. At the same time, transport machinery proteins, such as p24 proteins and SNAREs, and modifying enzymes need to be maintained in their compartments, as do resident proteins of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). This is partly aided by the linear signals –KDEL and –K(X)KXX, which represent well-characterized ER-localization signals for lumenal and membrane proteins, respectively (Teasdale & Jackson, 1996). Here, we review a class of less well-characterized ERsorting motifs: arginine (Arg)-based ER-localization signals. These signals were discovered in the context of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II transport (Bakke & Dobberstein, 1990; Lotteau et al, 1990), and after this discovery, a seminal study investigated the determinants that localize one form of the invariant chain Ii (Fig 1A) to the ER (Schutze et al, 1994). This paper is entitled 'An N-terminal double-arginine motif maintains type II membrane proteins in the ER', which led to the general assumption that these motifs were specific for type II membrane proteins. In addition, one particular generalization of the data in this study initially biased our concept of these sorting signals: the authors stressed the spacing requirement of the arginine residues with respect to the proximal amino-terminus. Although this is consistent with the data presented, the spacing issue may have been overemphasized owing to the influence of the previously characterized carboxy-terminal –K(X)KXX signal that depends crucially on exact spacing (Nilsson et al, 1989). Accordingly, it took the field some time to realize that these sorting motifs are much more widespread than previously believed and can, in fact, be active at various positions of diverse polytopic membrane proteins (Fig 1, supplementary Table I online).

Figure 1.

Arginine-based signals in proteins of different topology. Numbers indicate the size of cytosolic domains and the first Arg residue of the Arg-based signal. Arg-based signals are indicated in red. (A) Invariant chain Ii p35 of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II (p35 is one of two variants owing to the use of alternative initiator methionines). (B) γ-aminobutyric acid (GABAB) receptor subunit 1. The zigzag line indicates a coiled-coil forming domain. (C) Kir6.2 is the pore-forming subunit of the KATP channel. (D) SUR1 is the regulatory subunit of the KATP channel. (E) Glycoprotein B from human cytomegalovirus (HCMV). (F) N-methyl D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor subunit NR1-1.

Coupling the assembly state to forward transport

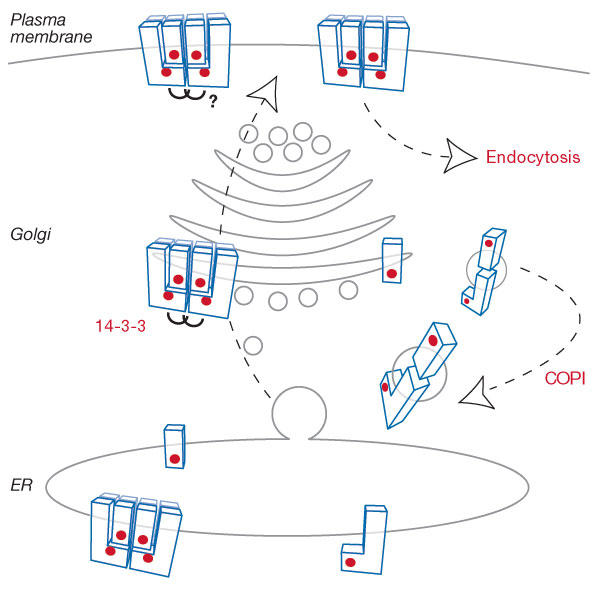

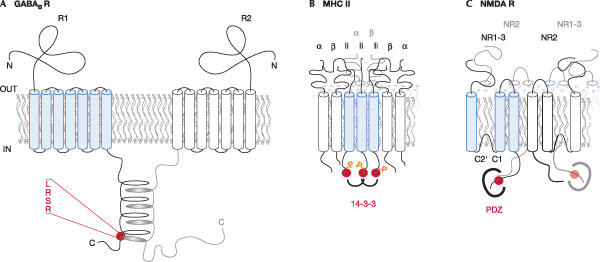

Arg-based signals can localize a broad range of reporter proteins to the ER but their function has been documented mainly in membrane protein complexes that are destined to leave the ER, for example, in ATP-sensitive potassium (KATP) channels (Fig 1C,D). These channels link the metabolic state of cells to their electrical excitability. The proper hetero-octameric assembly of four inward rectifier potassium (Kir) channel subunits and four sulphonylurea receptor (SUR) proteins is a prerequisite for KATP channels to exert their regulatory function in neurons or pancreatic β-cells. Each subunit contains one Arg-based signal that localizes unassembled subunits or incompletely assembled complexes to the ER. During heteromultimeric assembly, this signal is masked, which allows transport of the complex to the cell surface (Fig 2; Zerangue et al, 1999). Similarly, heterodimeric assembly of the G-protein-coupled γ-aminobutyric acid (GABAB) neurotransmitter receptor (Figs 1B,3A) is coupled to cellsurface transport of the complex by the presence of an Arg-based signal in one subunit (Margeta-Mitrovic et al, 2000). On the basis of these and additional examples (see below), it has become clear that an exposed Arg-based signal results in ER localization of the respective subunit or partial complex. In several cases, a di-leucine endocytic or lysosomal targeting motif also operates in the vicinity of the Arg-based signal (Hu et al, 2003; Khalil et al, 2003; Margeta-Mitrovic et al, 2000; Ren et al, 2003a). This indicates a possible second mechanism for controlling the composition and number of membrane protein complexes at the cell surface.

Figure 2.

Model of KATP channel transport. Larger and smaller rectangular shapes represent the SUR1 and Kir6.2 subunits, respectively. Arginine (Arg)-based signals are shown as red dots. 14-3-3 proteins are depicted as joined brackets. These proteins have been implicated in the forward transport of KATP channels (Yuan et al, 2003), but their exact role is unclear (Nufer & Hauri, 2003). A di-leucine endocytosis signal in the vicinity of the Arg-based signal has been shown to mediate dynamin-dependent endocytosis (Hu et al, 2003). COPI, coat protein complex I; ER, endoplasmic reticulum.

Figure 3.

Mechanisms for the masking of arginine-based signals. Red dots symbolize the Arg-based signals. (A) Steric masking: coiled-coil forming domains in the two γ-aminobutyric acid (GABAB) receptor subunits hide the signal present in GABAB R1-subunit (Margeta-Mitrovic et al, 2000). (B) Phosphorylation of a residue in the vicinity of the Arg-based signal in the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) invariant chain recruits 14-3-3 proteins (joined brackets), which leads to signal shielding (Kuwana et al, 1998). Heteromultimeric assembly with MHC class II βsubunit also leads to steric masking (Khalil et al, 2003). How the two mechanisms relate to each other is unclear. (C) Masking by a PDZ-domain protein (large bracket) binding to the distal C-terminus of N-methyl D-aspartate receptor subunit NR1-3 (Standley et al, 2000).

The rediscovery of Arg-based signals in polytopic membrane proteins has spurred numerous investigations of putative signals in other membrane protein complexes. Most ion channels and neurotransmitter receptors can form alternative heteromultimers; the resulting combinatorial variety is the basis for the different electrical properties of neurons and for changes in synaptic strength. Interestingly, a functional Arg-based signal has been identified in the alternatively spliced C-terminal C1 cassette of the ionotropic N-methyl D-aspartate (NMDA) glutamate receptor subunits NR1-1 and NR1-3 (Fig 1F; Scott et al, 2001; Standley et al, 2000; Xia et al, 2001), and subsequently in other ionotropic and metabotropic glutamate receptors (Chan et al, 2001; Ren et al, 2003a, 2003b). These recent findings suggest a role for Arg-based signals in the regulation of receptor complex assembly and movement beyond constitutive quality control as observed for the biosynthetic transport of KATP channels.

Consensus, position and distance from the membrane

Our information on an Arg-based motif consensus sequence is based on naturally occurring signals (supplementary Table I online) and variants created by site-directed mutagenesis. In addition, a combinatorial screening approach was used to select active or inactive variants from a random library containing Kir6.2-derived –TLASXXRXRXXSLS C-terminal tails (Zerangue et al, 2001). The integration of this information led to the conclusion that Arg-based signals conform to the consensus Φ/Ψ/R-R-X-R, in which Φ/Ψ denotes an aromatic or bulky hydrophobic residue and X represents any amino acid. Generally, lysine residues cannot substitute for arginine residues. More than two arginine residues gives rise to particularly strong sorting motifs, whereas the residue that precedes RXR and the identity of X itself can modulate the signal to an intermediate efficacy that results in significant steadystate Golgi localization. Indeed, quantitative trans-Golgi network processing and surface expression assays revealed that the variants identified from the random library cover a whole spectrum of differentially efficacious sorting signals (Zerangue et al, 2001). Negatively charged residues or small, non-polar side chains in these two positions usually render the signal inactive.

In contrast to the C-terminal –K(X)KXX ER-localization signal, Arg-based signals do not need to be exposed at the distal terminus of a membrane protein in order to be functional. Consistently, naturally occurring signals are present in different cytosolic domains of polytopic membrane proteins (Fig 1; supplementary Table I online). Transplantation of the signal to various positions in a range of reporter proteins has convincingly shown that the motif behaves as a peptide transport signal with no other requirements but sufficient exposure. Accordingly, Arg-based signals present in different members of a protein family (for example, Kir6.1/2 or SUR1/2 KATP channel subunits) can reside in particularly poorly conserved regions of the proteins. Accessibility of the signal depends not only on its position in the membrane protein but also on its proximity to a transmembrane segment. Careful comparison of the efficacy of an Arg-based and a –KKXX ER-localization signal (Shikano & Li, 2003) revealed that Arg-based signals are functional in a zone approximately 16–46 Å away from the lipid bilayer, whereas the –KKXX signal was more active when positioned closer to the cytoplasmic side of the membrane leaflet (Shikano & Li, 2003). The different spacing requirements of the two ER-localization signals with respect to their position in the protein and to the preceding transmembrane segment strongly suggest that they are recognized by different receptor proteins.

How and where are Arg-based signals recognized?

The cellular machinery required to decode Arg-based signals is poorly characterized (Nufer & Hauri, 2003). The coat protein complex I (COPI) complex mediates the retrieval of –K(X)KXX-bearing membrane proteins (McMahon & Mills, 2004), and so its role in the recognition of Arg-based signals has been tested (O'Kelly et al, 2002; Yuan et al, 2003; Zerangue et al, 2001). The results support a role for COPI in the retrieval of membrane proteins that expose an Arg-based signal; however, the details of recognition, such as which subunit of the coat complex acts as the direct receptor for the sorting signal, are obscure. Recent experiments have shown that variants of the –K(X)KXX signal are recognized by WD40 domains of either the α or the β′ COPI subunit (Eugster et al, 2004). The characteristic differences between –K(X)KXX and the Arg-based ER-localization signals discussed earlier strongly suggest that these peptide motifs are recognized by different binding pockets of the COPI complex.

Furthermore, the mechanistic issue of whether Arg-based signals result in ER retention versus ER retrieval is intimately linked to the cellular machinery involved in the process. Recognition by COPI is consistent with the finding that Arg-based signals can mediate the retrieval of proteins to the ER as assessed by glycan analysis (Hardt et al, 2003). However, in many cases, only a minority of membrane proteins exposing an Arg-based signal receives any modification that would indicate ER exit. Therefore, true retention mechanisms might exist in addition to COPI-mediated retrieval (Nufer & Hauri, 2003).

Masking of Arg-based signals

The ability of the Arg-based sorting motif to act as a transient ER-localization signal is one of its most striking and consistent features. This raises the question of how the signal is inactivated on proper heteromultimeric assembly (Fig 3). Steric masking by a partner subunit is the simplest conceivable mechanism and has previously been proposed for the masking of a –KKXX signal in a heteromultimeric complex (Letourneur et al, 1995). GABAB receptors illustrate this mechanism particularly well (Fig 3A) as the coiled-coil forming domains present in the C-termini of both GABAB subunits have been shown to mediate masking, not only in the context of the full-length receptor, but also when transplanted to a reporter protein (Margeta-Mitrovic et al, 2000). KATP channels (Fig 2) are another example of steric masking of the Arg-based signal after proper assembly. However, for these channels, the situation is more complex as 14-3-3 family proteins have been shown to recognize the C-terminal tail of one subunit, Kir6.2, provided it contains an Arg-based signal (Yuan et al, 2003). The hypothesis that 14-3-3 proteins can proofread the assembly state of multimeric proteins and promote the forward transport of properly assembled complexes by shielding the Arg-based signals needs to be tested in the context of the entire KATP channel complex (Nufer & Hauri, 2003). Interestingly, this situation is reminiscent of the invariant chain Ii (Fig 3B): the MHC class II β-chain cytoplasmic tail was shown to overcome the Arg-based signal during heteromultimeric assembly of the Ii–MHC complex (Khalil et al, 2003). In addition, invariant chain phosphorylation and subsequent 14-3-3 recruitment were required for the forward transport of Ii (Kuwana et al, 1998). The example of the NMDA receptor splice variants NR1-1 or NR1-3 (containing the C-terminal C1 as well as the C2′ cassette with a C-terminal PDZ-domain-interacting motif) provides a fascinating new perspective on the inactivation of the Arg-based signal: the phosphorylation of nearby residues has been proposed to inactivate the signal in the NMDA receptor subunit NR1-1 (Scott et al, 2001). Although the mechanism has been plausibly delineated, the ample use of negatively charged side-chains to introduce phospho-mimicking mutations close to the Arg-based signal is a source of concern: these changes might affect signal efficacy but do not show that such modulation happens as a consequence of an in vivo phosphorylation event (Scott et al, 2001, 2003; Standley et al, 2000; Xia et al, 2001). Finally, the Arg-based signal present in the NR1-3 subunit (Fig 3C) was shown to be masked by the recruitment of a PDZ-domain protein to the distal C-terminus of the protein (Scott et al, 2001; Standley et al, 2000; Xia et al, 2001). The issue of how Arg-based signals are masked is intimately connected to the question of where in the secretory pathway the crucial events occur (Nufer & Hauri, 2003) and to what extent early interactions impinge on later transport steps.

Other functions?

Strong Arg-based signals have been found in the C-termini of type I viral membrane proteins (Fig 1E), the glycoprotein B homologues of Epstein–Barr virus, herpes simplex virus type I and human cytomegalovirus (Lee, 1999; Meyer et al, 2002; Meyer & Radsak, 2000). These viruses undergo a characteristic nuclear phase of maturation. Accordingly, studies have focused on the surprising finding that Arg-based signals are able to mediate access of viral membrane proteins to the inner nuclear membrane (Meyer et al, 2002; Meyer & Radsak, 2000). This is in contrast to membrane proteins that are destined for the secretory pathway or ER-resident proteins that are normally excluded from this domain.

Arg-based signals can result in the steady-state localization of various reporter proteins to the ER. However, there is virtually no evidence that these signals do actually localize ER-resident proteins to this compartment. The N-terminus of the ER resident glucosidase I contains a functional Arg-based signal that is, however, not required to localize the full-length protein (Hardt et al, 2003).

Another plausible function of Arg-based signals might be the coupling of folding status to the forward transport of a membrane protein. This scenario, in which the signal is exposed due to improper folding, has been investigated for the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) protein (Chang et al, 1999). The effect of replacing the arginine residues in four different putative Arg-based signals was impressive: the manipulation resulted in the plasma membrane targeting of the ΔF508 mutant form of the protein, which is normally degraded due to ER quality control and which is the cause of disease in most cystic fibrosis patients. However, one of the Arg-based signals that were manipulated is not present in mouse CFTR and another one occurs in a region previously shown to be sensitive to secondsite suppressor mutations. Furthermore, the crucial defect in the ΔF508 mutant protein has been shown recently to lie in the loss of a functional ER-exit signal rather than the exposure of normally masked ER-localization signals (Wang et al, 2004). Whether or not the transient exposure of Arg-based signals during folding mediates ER localization beyond the action of ER chaperones remains an important and technically challenging question. Evidence in favour of this concept has been provided by the exposure of active Arg-based signals as a consequence of truncating proteins (Hermosilla & Schulein, 2001; Kupershmidt et al, 2002). Of particular interest is the interplay between such normally hidden signals and disease-causing mutations. This relationship has been investigated for SUR1 mutations that correlate with hyperinsulinism (Cartier et al, 2001) and vasopressin receptor 2 mutations that correlate with diabetes insipidus (Hermosilla et al, 2004). These experiments suggest that the degree of misfolding of a mutant protein determines whether or not Arg-based signals present in the protein impinge on its transport; for example, whether or not inactivation of an Arg-based signal allows forward transport of the mutant membrane protein.

Conclusions and perspectives

Arg-based signals are distinct from other known ER-localization signals with respect to their consensus sequence, positioning and function. In the future, we hope to understand the details of how the COPI coat recognizes the signal and results in the retrieval of membrane proteins. Additional cellular machinery may participate in mediating the ER localization of membrane proteins that contain an Arg-based signal. Steric masking is one main mechanism that leads to the inactivation of these signals in the course of heteromultimeric assembly, but it will be exciting to pursue further the role of phosphorylation, as well as the recruitment of additional proteins such as 14-3-3 in the masking of Arg-based signals. Eventually, the goal is to understand the physiological significance of Arg-based signal exposure and masking.

Supplementary information is available at EMBO reports online (http://www.emboreports.org).

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Fig 1

Kai Michelsen, Blanche Schwappach and Hebao Yuan. B.S. is the recipient of an EMBO Young Investigator award.

Acknowledgments

We thank many colleagues from the Zentrum für Molekulare Biologie der Universität Heidelberg (ZMBH) and the Biochemistry Centre (BZH), as well as members of the Schwappach laboratory for critical reading of the manuscript. Our work is funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (SFB638), the Landesstiftung Baden-Württemberg and the EMBO Young Investigator Programme.

References

- Bakke O, Dobberstein B (1990) MHC class II-associated invariant chain contains a sorting signal for endosomal compartments. Cell 63: 707–716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cartier EA, Conti LR, Vandenberg CA, Shyng SL (2001) Defective trafficking and function of KATP channels caused by a sulfonylurea receptor 1 mutation associated with persistent hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia of infancy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 2882–2887 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan WY, Soloviev MM, Ciruela F, McIlhinney RA (2001) Molecular determinants of metabotropic glutamate receptor 1B trafficking. Mol Cell Neurosci 17: 577–588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang XB, Cui L, Hou YX, Jensen TJ, Aleksandrov AA, Mengos A, Riordan JR (1999) Removal of multiple arginine-framed trafficking signals overcomes misprocessing of ΔF508 CFTR present in most patients with cystic fibrosis. Mol Cell 4: 137–142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eugster A, Frigerio G, Dale M, Duden R (2004) The α- and β′-COP WD40 domains mediate cargoselective interactions with distinct di-lysine motifs. Mol Biol Cell 15: 1011–1023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardt B, Kalz-Fuller B, Aparicio R, Volker C, Bause E (2003) (Arg)3 within the N-terminal domain of glucosidase I contains ER targeting information but is not required absolutely for ER localization. Glycobiology 13: 159–168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermosilla R, Schulein R (2001) Sorting functions of the individual cytoplasmic domains of the G protein-coupled vasopressin V(2) receptor in Madin Darby canine kidney epithelial cells. Mol Pharmacol 60: 1031–1039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermosilla R, Oueslati M, Donalies U, Schonenberger E, Krause E, Oksche A, Rosenthal W, Schulein R (2004) Disease-causing V(2) vasopressin receptors are retained in different compartments of the early secretory pathway. Traffic 5: 993–1005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu K, Huang CS, Jan YN, Jan LY (2003) ATPsensitive potassium channel traffic regulation by adenosine and protein kinase C. Neuron 38: 417–432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khalil H, Brunet A, Saba I, Terra R, Sekaly RP, Thibodeau J (2003) The MHC class II β chain cytoplasmic tail overcomes the invariant chain p35-encoded endoplasmic reticulum retention signal. Int Immunol 15: 1249–1263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kupershmidt S, Yang T, Chanthaphaychith S, Wang Z, Towbin JA, Roden DM (2002) Defective human Ether-a-go-go-related gene trafficking linked to an endoplasmic reticulum retention signal in the C terminus. J Biol Chem 277: 27442–27448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuwana T, Peterson PA, Karlsson L (1998) Exit of major histocompatibility complex class II–invariant chain p35 complexes from the endoplasmic reticulum is modulated by phosphorylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95: 1056–1061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SK (1999) Four consecutive arginine residues at positions 836–839 of EBV gp110 determine intracellular localization of gp110. Virology 264: 350–358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letourneur F, Hennecke S, Demolliere C, Cosson P (1995) Steric masking of a dilysine endoplasmic reticulum retention motif during assembly of the human high affinity receptor for immunoglobulin E. J Cell Biol 129: 971–978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lotteau V, Teyton L, Peleraux A, Nilsson T, Karlsson L, Schmid SL, Quaranta V, Peterson PA (1990) Intracellular transport of class II MHC molecules directed by invariant chain. Nature 348: 600–605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margeta-Mitrovic M, Jan YN, Jan LY (2000) A trafficking checkpoint controls GABA(B) receptor heterodimerization. Neuron 27: 97–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMahon HT, Mills IG (2004) COP and clathrin-coated vesicle budding: different pathways, common approaches. Curr Opin Cell Biol 16: 379–391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer GA, Radsak KD (2000) Identification of a novel signal sequence that targets transmembrane proteins to the nuclear envelope inner membrane. J Biol Chem 275: 3857–3866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer G, Gicklhorn D, Strive T, Radsak K, Eickmann M (2002) A three-residue signal confers localization of a reporter protein in the inner nuclear membrane. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 291: 966–971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson T, Jackson M, Peterson PA (1989) Short cytoplasmic sequences serve as retention signals for transmembrane proteins in the endoplasmic reticulum. Cell 58: 707–718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nufer O, Hauri HP (2003) ER export: call 14-3-3. Curr Biol 13: R391–R393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Kelly I, Butler MH, Zilberberg N, Goldstein SA (2002) Forward transport. 14-3-3 binding overcomes retention in endoplasmic reticulum by dibasic signals. Cell 111: 577–588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren Z, Riley NJ, Garcia EP, Sanders JM, Swanson GT, Marshall J (2003) Multiple trafficking signals regulate kainate receptor KA2 subunit surface expression. J Neurosci 23: 6608–6616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren Z, Riley NJ, Needleman LA, Sanders JM, Swanson GT, Marshall J (2003) Cell surface expression of GluR5 kainate receptors is regulated by an endoplasmic reticulum retention signal. J Biol Chem 278: 52700–52709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schutze MP, Peterson PA, Jackson MR (1994) An N-terminal double-arginine motif maintains type II membrane proteins in the endoplasmic reticulum. EMBO J 13: 1696–1705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott DB, Blanpied TA, Swanson GT, Zhang C, Ehlers MD (2001) An NMDA receptor ER retention signal regulated by phosphorylation and alternative splicing. J Neurosci 21: 3063–3072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott DB, Blanpied TA, Ehlers MD (2003) Coordinated PKA and PKC phosphorylation suppresses RXR-mediated ER retention and regulates the surface delivery of NMDA receptors. Neuropharmacology 45: 755–767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shikano S, Li M (2003) Membrane receptor trafficking: evidence of proximal and distal zones conferred by two independent endoplasmic reticulum localization signals. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100: 5783–5788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Standley S, Roche KW, McCallum J, Sans N, Wenthold RJ (2000) PDZ domain suppression of an ER retention signal in NMDA receptor NR1 splice variants. Neuron 28: 887–898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teasdale RD, Jackson MR (1996) Signal-mediated sorting of membrane proteins between the endoplasmic reticulum and the Golgi apparatus. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 12: 27–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Matteson J, An Y, Moyer B, Yoo JS, Bannykh S, Wilson IA, Riordan JR, Balch WE (2004) COPII-dependent export of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator from the ER uses a di-acidic exit code. J Cell Biol 167: 65–74 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia H, Hornby ZD, Malenka RC (2001) An ER retention signal explains differences in surface expression of NMDA and AMPA receptor subunits. Neuropharmacology 41: 714–723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan H, Michelsen K, Schwappach B (2003) 14-3-3 dimers probe the assembly status of multimeric membrane proteins. Curr Biol 13: 638–646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zerangue N, Schwappach B, Jan YN, Jan LY (1999) A new ER trafficking signal regulates the subunit stoichiometry of plasma membrane K(ATP) channels. Neuron 22: 537–548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zerangue N, Malan MJ, Fried SR, Dazin PF, Jan YN, Jan LY, Schwappach B (2001) Analysis of endoplasmic reticulum trafficking signals by combinatorial screening in mammalian cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 2431–2436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Fig 1