Abstract

The regulated splicing of fibroblast growth factor receptor-2 (FGFR2) transcripts leads to tissue-specific expression of distinct receptor isoforms. These isoforms contain two different versions of the ligand binding Ig-like domain III, which are encoded by exon IIIb or exon IIIc. The mutually exclusive use of exon IIIb and exon IIIc can be recapitulated in tissue culture using DT3 and AT3 rat prostate carcinoma cells. We used this well-characterized system to evaluate the precision and accuracy of the RNA invasive cleavage assay to specifically measure FGFR2 alternative splicing outcomes. Experiments presented here demonstrated that the RNA invasive cleavage assay could specifically detect isoforms with discrimination levels that ranged from 1 in 5 × 103 to 1 in 105. Moreover the assay could detect close to 0.01 amole of FGFR2 RNAs. The assay detected the expected levels of transcripts containing either exon IIIb or IIIc, but, surprisingly, it detected high levels of IIIb-IIIc double inclusion transcripts. This finding, which has important implications for the role of exon silencing and of mRNA surveillance mechanisms, had been missed by RT-PCR. Additionally, we used the RNA invasive cleavage assay to demonstrate a novel function for the regulatory element IAS2 in repressing exon IIIc inclusion. We also show here that purification of RNA is not necessary for the invasive cleavage assay, because crude cell lysates could be used to accurately measure alternative transcripts. The data presented here indicate that the RNA invasive cleavage assay is an important addition to the repertoire of techniques available for the study of alternative splicing.

Keywords: Alternative splicing, FGFR2, gene expression, Invader RNA assay, invasive cleavage, RNA quantification

INTRODUCTION

The sequencing and preliminary annotation of the human genome provides evidence of a preponderance of large and complex protein-coding genes. The majority of these genes encode primary transcripts that undergo alternative splicing (Modrek and Lee 2002), a process that generates different mRNAs from one gene (Black 2000). Properly regulated alternative splicing is critical for normal development, and a breakdown in the regulation of alternative splicing leads to cellular abnormalities and to human disease (Savkur et al. 2001; Cartegni and Krainer 2002; Cartegni et al. 2002). These functional implications of alternative splicing underscore the importance of assays that can quantitatively and specifically measure alternative transcripts. Functionally significant alternative splicing is seen among fibroblast growth factor receptor-2 (FGFR2) transcripts. The differential inclusion of FGFR2 exon 8 (IIIb) or exon 9 (IIIc) leads to the expression of FGFR2 isoforms with different ligand specificity. Exon IIIb is predominantly included in epithelial cells, whereas exon IIIc is exclusively used in mesenchymal cells (Fig. 1 ▶). As a consequence of expressing FGFR2(IIIb), epithelial cells respond to FGF10 and FGF7, whereas in mesenchymal cells the FGFR2(IIIc) responds to FGF2. Inappropriate expression of FGFR2(IIIb) in fibroblasts induces transformation in culture (Miki et al. 1991) and loss of FGFR2(IIIb) expression leads to absent or malformed epithelial compartments in many organs in mice (De Moerlooze et al. 2000). A switch from the IIIb to the IIIc isoform accompanies the progression of androgen-sensitive, well-differentiated prostate carcinomas to androgen-insensitive, poorly differentiated tumors in both rats and humans (Yan et al. 1993; Carstens et al. 1997). The governance of cell-type-specific FGFR2 isoform expression is therefore important in normal development and tumor progression.

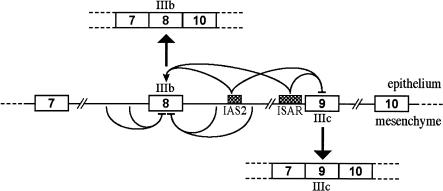

FIGURE 1.

Multiple layers of combinatorial interactions result in tissue-specific alternative splicing of FGFR2 transcripts. A schematic of exons 7–10 and introns 7–9 of FGFR2 is shown indicating that silencing of exon IIIb dominates in mesenchymal cells. In epithelial cells, however, a layer of regulation combines activation of exon 8 (IIIb) with repression of exon 9 (IIIc). These activities are mediated by two cis-elements: IAS2 and ISAR.

Functional FGFR2 mRNAs constitutively include exon 7 and exon 10, and different regulatory pathways select exon IIIb or IIIc to produce 7-IIIb-10 and 7-IIIc-10 transcripts in a tissue-specific manner (Fig. 1 ▶). Two other variant RNAs have been described: One is the result of splicing between exons 7 and 10 (7–10) and is called the skipped product, and the other includes both IIIb and IIIc (7-IIIb-IIIc-10) and is known as the double inclusion product. Both of these mRNAs, which encode truncated, nonfunctional receptors, are destabilized by nonsense-mediated decay (Jones et al. 2001). Thus, the choice of including either IIIb or IIIc and the decision to skip or double include must be controlled. The regulation of FGFR2 alternative splicing represents a complex interplay between positive- and negative-acting factors. There is documentation for at least 10 cis-acting elements, which are the targets for splicing activators and repressors (Wagner and Garcia-Blanco 2001). We have studied the cell-type-specific expression of 7-IIIb-10 in DT3 cells, which are derived from a well-differentiated rat prostate carcinoma, and the expression of 7-IIIc-10 in AT3 cells, a related but poorly differentiated rat prostate tumor line (Yan et al. 1993). This exon choice is regulated by the interplay of cis-acting elements, two of which appear to be cell-type specific, and the trans-acting factors that recognize them. In DT3 cells, two elements, the intronic activation sequence 2 (IAS2) and the intronic splicing activator and repressor (ISAR; also called IAS3), activate exon IIIb (Del Gatto et al. 1997; Carstens et al. 1998), whereas in AT3 cells these elements have no discernable function (Fig. 1 ▶). The ISAR element, as its name suggests, also represses exon IIIc in DT3 cells (Carstens et al. 1998). To date, the tissue-specific trans-acting factors that regulate exon choice have not been identified.

To further investigate the complex alternative splicing of FGFR2, we required higher resolution analysis than had been previously provided by RT-PCR. To this end, we investigated the quantitative capability of the RNA invasive cleavage assay (Eis et al. 2001; de Arruda et al. 2002), herein termed the Invader (Invader is a registered trademark of Third Wave Technologies, Inc.) RNA assay. The Invader RNA assay utilizes an engineered 5′ nuclease [Cleavase (Cleavase is a registered trademark of Third Wave Technologies, Inc.) enzyme] to cleave a DNA oligonucleotide probe in the presence of a target RNA in a sequence- and structure-specific manner (Lyamichev et al. 1999; Ma et al. 2000). In this report, we demonstrate that the Invader RNA assay can quantitatively discriminate between four alternatively spliced FGFR2 transcripts using purified total cellular RNA or crude cell lysates. Furthermore, the Invader RNA assay revealed two novel observations previously obscured by the RT-PCR analysis. First, surprisingly high levels of double inclusion (IIIb-IIIc) product were found, and second, the levels of skipped product were much lower than previously measured. These findings have important implications, which will be discussed below. Our studies also led us to the unexpected observation that the IAS2 element, which had previously been described as an activator of splicing, was observed to be a repressor of exon IIIc.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

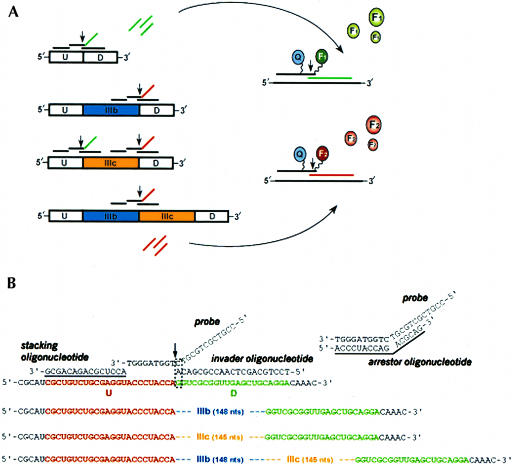

To facilitate the study of FGFR2 splicing regulation we have constructed minigene constructs that recapitulate the cell-type-specific regulation of endogenous FGFR2 transcripts (Carstens et al. 1998; Carstens et al. 2000; Wagner and Garcia-Blanco 2002). In these double-exon minigenes, the 7 and 10 FGFR2 exons have been replaced with heterologous upstream (U) and downstream (D) exons derived from the Adenovirus2 major late promoter transcription unit (Carstens et al. 1998). The transcription products of these minigenes, which are synthesized in vitro using a T7 RNA polymerase promoter or in vivo from the human cytomegalovirus immediate early promoter, can be alternatively spliced to produce four RNA variants: U-D, U-IIIb-D, U-IIIc-D, and U-IIIb-IIIc-D (Fig. 2A ▶).

FIGURE 2.

Schematics of the Invader RNA assay probe sets and the FGFR2 RNA variants derived from the alternative splicing of exons IIIb and IIIc. (A) Splice variants generated from the minigene constructs used in this report contain U and D exons, which are derived from Adenovirus2 L1 and L2 exons. Variants, depicted in the 5′–3′ orientation, can also contain IIIb and/or IIIc exons, which are derived from the rat FGFR2 gene (see Materials and Methods). Five Invader probe sets (see Table 1 ▶ for oligonucleotide sequences) were used to uniquely detect the splicing products. It should be noted that the IIIc-D probe set could also recognize this junction in the U-IIIb-IIIc-D RNA (not shown in the figure). Each probe set consists of, from left to right, a stacking oligonucleotide, the probe (with noncomplementary 5′ flap), and an Invader oligonucleotide (see B for more details). Two probe sets were run per Invader reaction using the biplex detection format (see Materials and Methods for the probe set combinations). Invader probe sets are shown in the 3′–5′ orientation as black lines above the splice variants except for the probe 5′ flaps, which are color-coded green or red to signify the fluorophore (F1 or F2) used for detection (right side of figure). Vertical arrows indicate Cleavase enzyme cleavage sites, which results in the release of multiple 5′ flaps (left side) or unquenched fluorophores (right side). Curved arrows indicate use of the cleaved 5′ flaps produced in the first reaction (left side) in the second reaction (right side). See text for further description of the Invader assay. (B) Detailed view of the U-D Invader probe set. The stacking oligonucleotide, probe, and Invader oligonucleotide are shown aligned on the U-D transcript from left to right. A dashed line box indicates the overlap structure and the vertical arrow indicates the probe cleavage site for the Cleavase enzyme. Transcript sequences for the IIIb, IIIc, and IIIb-IIIC splice variants are also shown to illustrate the inability of the probe and Invader oligonucleotide to form the overlap structure required for cleavage of the 5′ flap. A separate duplex structure between the probe and arrestor oligonucleotide, which is added in the secondary reaction to enhance signal generation, is depicted. Underlined sequences for the arrestor and stacking oligonucleotides indicate use of 2`-O-methylated nucleotides (see text). For further details see Eis et al. (2001) and de Arruda et al. (2002).

Five Invader RNA assay probe sets (Table 1 ▶) were designed to recognize unique splice junctions in each of the four RNA variants (Fig. 2A ▶). A detailed view of the U-D probe set is shown in Figure 2B ▶ to further illustrate the mechanics of the assay. Each Invader probe set consists of a stacking oligonucleotide, a probe, and an Invader oligonucleotide (Eis et al. 2001). The probe and Invader oligonucleotide in each set form an invasive cleavage structure in the presence of the appropriate RNA. The invasive cleavage structure comprises at least a 1-bp overlap between the 3′ end of the Invader oligonucleotide with the 5′ target specific region (TSR) of the probe (Fig. 2B ▶). The probe's noncomplementary 5′ flap, which is the portion of the probe that is quantitatively detected, can then be cleaved on the 3′ side of the invaded base pair as indicated (Fig. 2B ▶, vertical arrow). Probe cleavage is performed using the 5′ nuclease activity of an engineered Thermus thermophilus DNA polymerase, referred to herein as a Cleavase enzyme (Kaiser et al. 1999; Ma et al. 2000; Eis et al. 2001). Although the probe and Invader oligonucleotide span the RNA sequence with a typical footprint size of 35–40 nt, cleavage of the probe's 5′ flap is critically dependent on the precise formation of the one-base overlap structure. Thus, positioning this overlap at or near the splice junction enables specific detection of RNAs containing this particular splice site. For example, the U-D Invader probe set in Figure 2B ▶ detects RNAs containing the U-D splice site but not the other RNAs depicted, as the sequences from exons IIIb and/or IIIc would preclude formation of the overlap.

TABLE 1.

Oligonucleotides used in the Invader RNA assay

| Probe set | Oligonucleotide | Sequencea (5′ to 3′) |

| U-D | Probe | 5′-ccgtcgctgcgtCTGGTAGGGT-NH2-3′ |

| Invader oligo | 5′-TCCTGCAGCTCAACCGCGACA-3′ | |

| Stacking oligo | 5′-ACCUCGCAGACAGCG-3′ | |

| Arrestor oligo | 5′-ACCCUACCAGACGCAG-3′ | |

| FRET oligo | FAM-5′-CAC(DQ)TGCTTCGTGG-3′ | |

| Secondary reaction template | 5′-CCAGGAAGCAAGTGACGCAGCGACGGU-3′ | |

| Synthetic target oligo (coding) | 5′-GGTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGACGCATCGCTGTCTGCGAGGTACCCTACCAGGTCGCGGTTGAGCTGCAGGACAAAC-3′ | |

| Synthetic target oligo (noncoding) | 5′-GTTTGTCCTGCAGCTCAACCGCGACCTGGTAGGGTACCTCGCAGACAGCGATGCGTCCCTATAGTGAGTCGTATTACC-3′ | |

| III-D | Probe | 5′-ccgtcacgcctcCTTGCTGTTTG-NH2-3′ |

| Invader oligo | 5′-TCCTGCAGCTCAACCGCGACA-3′ | |

| Stacking oligo | 5′-GGCAGGACAGUGAGCC-3′ | |

| Arrestor oligo | 5′-CAAACAGCAAGGAGGCG-3′ | |

| FRET oligo | Red-5′-CTC(DQ)TTCTCAGTGCG-3′ | |

| Secondary reaction template | 5′-CGCAGTGAGAATGAGGAGGCGTGACGGU-3′ | |

| Synthetic target oligo (coding) | 5′-GGTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGATGCCTGGCTCACTGTCCTGCCCAAACAGCAAGGTCGCGGTTGAGCTGCAGGACAAAC-3′ | |

| Synthetic target oligo (noncoding) | 5′-GTTTGTCCTGCAGCTCAACCGCGACCTTGCTGTTTGGGCAGGACAGTGAGCCAGGCATCCCTATAGTGAGTCGTATTACC-3′ | |

| U-IIIc | Probe | 5′-ccgtcgctgcgtCTGGTAGGGT-NH2-3′ |

| Invader oligo | 5′-CGTGGTGTTAACACCGGCGGCA-3′ | |

| Stacking oligo | 5′-ACCUCGCAGACAGCG-3′ | |

| Arrestor oligo | 5′-ACCCUACCAGACGCAG-3′ | |

| FRET oligo | FAM-5′-CAC(DQ)TGCTTCGTGG-3′ | |

| Secondary reaction template | 5′-CCAGGAAGCAAGTGACGCAGCGACGGU-3′ | |

| Synthetic target oligo (coding) | 5′-GGTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGACGCATCGCTGTCTGCGAGGTACCCTACCAGGCCGCCGGTGTTAACACCACGGACAA-3′ | |

| Synthetic target oligo (noncoding) | 5′-TTGTCCGTGGTGTTAACACCGGCGGCCTGGTAGGGTACCTCGCAGACAGCGATGCGTCCCTATAGTGAGTCGTATTACC-3′ | |

| IIIb-IIIc | Probe | 5′-ccgtcacgcctcCTTGCTGTTTG-NH2-3′ |

| Invader oligo | 5′-CGTGGTGTTAACACCGGCGGCA-3′ | |

| Stacking oligo | 5′-GGCAGGACAGUGAGCC-3′ | |

| Arrestor oligo | 5′-CAAACAGCAAGGAGGCG-3′ | |

| FRET oligo | Red-5′-CTC(DQ)TTCTCAGTGCG-3′ | |

| Secondary reaction template | 5′-CGCAGTGAGAATGAGGAGGCGTGACGGU-3′ | |

| Synthetic target oligo (coding) | 5′-AGGTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGATGCCTGGCTCACTGTCCTGCCCAAACAGCAAGGCCGCCGGTGTTAACACCACGGACAAT-3′ | |

| Synthetic target oligo (noncoding) | 5′-ATTGTCCGTGGTGTTAACACCGGCGGCCTTGCTGTTTGGGCAGGACAGTGAGCCAGGCATCCCTATAGTGAGTCGTATTACCT-3′ | |

| IIIc-D | Probe | 5′-ccgtcacgcctcCTGGCAGAAC-NH2-3′ |

| Invader oligo | 5′-TCCTGCAGCTCAACCGCGACA-3′ | |

| Stacking oligo | 5′-UGUCAACCAUGCAGAGU-3′ | |

| Arrestor oligo | 5′-GUUCUGCCAGGAGGCG-3′ | |

| FRET oligo | Red-5′-CTC(DQ)TTCTCAGTGCG-3′ | |

| Secondary reaction template | 5′-CGCAGTGAGAATGAGGAGGCGTGACGGU-3′ | |

| Synthetic target oligo (coding) | 5′-GGTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGACCTTTCACTCTGCATGGTTGACAGTTCTGCCAGGTCGCGGTTGAGCTGCAGGACAAAC-3′ | |

| Synthetic target oligo (noncoding) | 5′-GTTTGTCCTGCAGCTCAACCGCACCTGGCAGAACTGTCAACCATGCAGAGTGAAAGGTCCCTATAGTGAGTCGTATTACC-3′ |

aLowercase bases indicate 5′ flap sequences. Cleavage base indicated bold. A 3′NH2 can be included to enhance assay performance. Underlined bases indicate 2` O-methylated nucleotides.

Redmond Red (Red) and Eclipse Dark Quencher (DQ) were obtained from Epoch Biosciences (Bothell, WA).

To achieve sensitive detection of RNA (<0.05 amole) without target amplification, the Invader RNA assay uses two levels of signal amplification—probe turnover and linkage of two Invader reactions—to yield an overall amplification factor of ~106-fold (Hall et al. 2000; Lyamichev et al. 2000). Probe turnover (probe association, cleavage, and dissociation of cleaved fragments) is accomplished by running the assay isothermally near the melting temperature of the probe TSR, thus resulting in the specific, linear accumulation of cleaved 5′ flaps in a target- and time-dependent manner. Linkage of two Invader reactions is achieved by using the cleaved 5′ flaps from the first (primary) reaction (Fig. 2A ▶, left side) as Invader oligonucleotides in the second (secondary) reaction (Fig. 2A ▶, right side). This enables formation of a second invasive cleavage structure along with a secondary reaction template (SRT) and a fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) oligonucleotide (Fig. 2A ▶, right side). Fluorescence signal is generated in a cleaved 5′ flap-dependent manner when the Cleavase enzyme cleaves the FRET oligonucleotide between its fluorophore and quencher. Cleavage of the FRET oligonucleotide results in enhanced fluorescence due to spatial separation of the fluorophore and quencher (see Ghosh et al. 1994, and references therein). For simplicity, the two Invader reactions, primary and secondary, are optimized to run isothermally at the same temperature. See also the Materials and Methods section.

There are additional design features that have been routinely implemented to simplify or further enhance the performance of the Invader assay, and these have been described in detail in Eis et al. (2001) and de Arruda et al. (2002). These include use of stacking oligonucleotides, arrestor oligonucleotides, a 3′ mismatch on the end of the Invader oligonucleotide, generic sequence noncomplementary 5′ flap sequences, and a biplex FRET detection format (Fig. 2 ▶). The biplex FRET-based detection format uses two spectrally distinct fluorophores and a nonfluorescent quencher (Fig. 2A ▶). Use of two different generic sequence 5′ flaps enables detection of two unique RNA molecules or splice sites in the same sample.

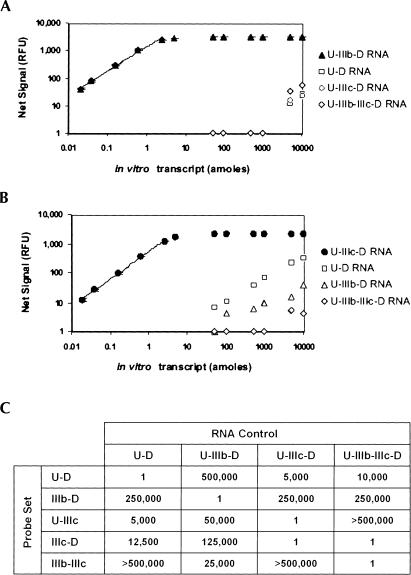

The specificity and quantitative capability of the five Invader probe sets were tested using four variant RNA in vitro transcripts. All five Invader probe sets readily discriminated between the four RNA variants (Fig. 3 ▶). For example, the IIIb-D probe set, which was designed to detect a junction found only in the U-IIIb-D RNA, preferentially recognized this RNA over the other three variants with a 1 in 500,000 discrimination level (Fig. 3A,C ▶). Likewise, the U-IIIc probe set specifically detected the U-IIIc-D RNA (Fig. 3B,C ▶). The least robust discrimination level by the U-IIIc probe set was 1 in 5,000 for the U-D RNA (Fig. 3C ▶), which is still well outside the quantitative range for the U-IIIc probe set and thus not regarded as problematic. These data indicated that the Invader RNA assay could specifically quantify the levels of all four alternatively spliced RNA variants (summarized in Fig. 3C ▶) with a sensitivity ranging from 0.01 to 0.04 amole.

FIGURE 3.

The Invader RNA assay discriminates between alternatively spliced FGFR2 transcripts. (A, B) The Invader RNA assay, using the IIIb-D (A) or the U-IIIc probe set (B), was carried out with increasing levels (0.01–10,000 amole) of the four variant RNAs (Fig. 2 ▶). Linear regression (R2) values for the fitted regions of the data are 0.992 and 0.998 for IIIb-D and U-IIIc, respectively. Error bars represent one standard deviation. (C) Table of the discrimination capability of the five probe sets on the four RNA variants. The discrimination capability for each probe set was calculated by dividing the highest target level in which no significant signal was detected for another RNA variant by the limit of detection for the probe set being tested. Values listed represent the inverse of the discrimination capability (e.g., the IIIb-D probe set has a limit of detection of 0.02 amole and it detects background signal from the U-D transcript at 5,000 amole: 5,000/0.02 = 250,000 discrimination level).

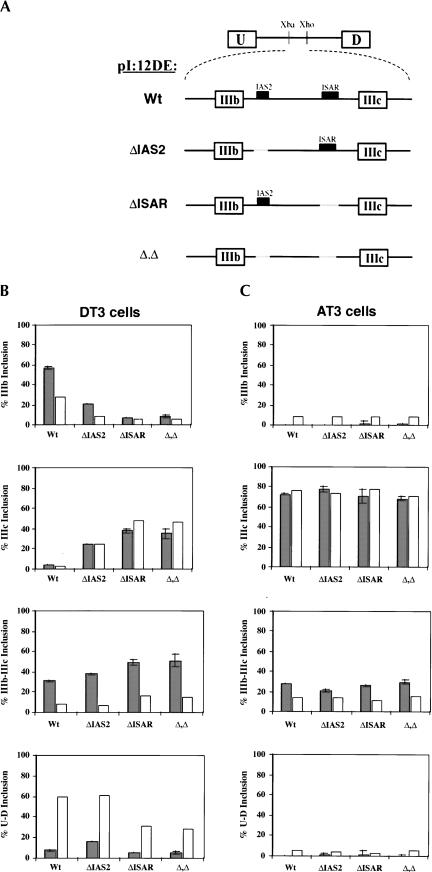

We have previously shown that the double-exon minigene constructs described above recapitulate the cell-type specific choice of IIIb versus IIIc when transfected into DT3 and AT3 cells (Carstens et al. 1998). These double-exon minigenes provided us with an excellent system to test the utility of the Invader RNA assay in quantifying alternative splice site RNA variants. Thus, we transfected DT3 and AT3 cells with the pI12DE:Wt minigene construct (Fig. 4A ▶) and quantified the levels of the four variant RNAs (U-D, U-IIIb-D, U-IIIc-D, and U-IIIb-IIIc-D) using the probe sets described in Figure 2 ▶. When transfected with this minigene, DT3 cells preferentially include exon IIIb, and AT3 cells almost exclusively use exon IIIc (Fig. 4B ▶). The data derived from the Invader RNA assay supported our prior conclusions regarding the cell-type-specific expression of U-IIIb-D in DT3 cells and U-IIIc-D in AT3 cells (Carstens et al. 1998). Although the same general trend was observed with the Invader RNA assay (gray bars) and with RT-PCR (white bars), we noted significant overrepresentation of the U-D product in DT3 cells by RT-PCR (Fig. 4B ▶, bottom panel). This anomaly is likely due to the propensity of PCR to favor the smaller U-D product. Perhaps most importantly, the Invader RNA assay revealed a surprisingly high level of double inclusion (U-IIIb-IIIc-D) RNA in both DT3 and AT3 cells (Fig. 4B,C ▶, bottom panels). It is important to note that because this minigene does not encode an open reading frame, the U-D and U-IIIb-IIIc-D transcripts are not destabilized by nonsense-mediated decay.

FIGURE 4.

Quantification of alternatively spliced FGFR2 transcripts. (A) Schematic of double-exon minigene constructs used to study the cell-type-specific inclusion of exons IIIb and/or IIIc. The presence or absence of IAS2 and ISAR is indicated. These minigenes can direct the expression of four RNAs produced by alternative splicing: skipping of IIIb and IIIc yields U-D RNA, inclusion of either IIIb or IIIc yields U-IIIb-D or U-IIIc-D, respectively, and double inclusion yields U-IIIb-IIIc-D. (B) DT3 cells and (C) AT3 cells were transfected with the minigene constructs in A. Total RNA was extracted and analyzed with either the Invader RNA assay (gray bars) or semiquantitative RT-PCR (white bars) for the presence of the four RNA variants. Error bars for the Invader RNA assay data represent one standard deviation. In B and C the percent inclusion of a product (e.g., U-IIIb-D) among transcripts was calculated as follows: percent product (e.g., U-IIIb-D) inclusion = {[product (e.g., U-IIIb-D)]/([U-D] + [U-IIIb-D)] + [U-IIIc-D] + [U-IIIb-IIIc-D])} × 100.

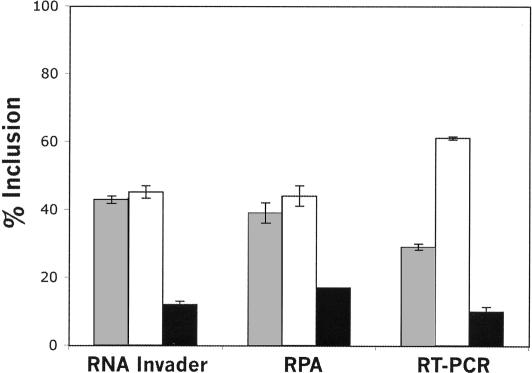

The discrepancy in quantification of the U-IIIb-IIIc-D RNA by the Invader RNA assay and RT-PCR was investigated using an RNase protection assay (RPA). RNA isolated from DT3 cells transfected with the pI:12DE:Wt minigene was analyzed using the Invader RNA Assay, RPA, and RT-PCR. RPA and the Invader RNA assay yielded similar data, whereas RT-PCR again underrepresented the level of U-IIIb-IIIc-D RNA relative to that of U-IIIb-D RNA (Fig. 5 ▶). Similar agreement between the Invader RNA assay and RPA was seen in AT3 cells (not shown). These data, first obtained with the Invader RNA assay and confirmed with RPA, suggest that the regulation of exon choice in FGFR2 transcripts is not as stringent as previously assumed (see discussion below).

FIGURE 5.

Comparison of the Invader RNA assay, RNase protection assay, and RT-PCR assay in the quantification of FGFR2 transcripts. pI12DE:Wt, which is described in Figure 4A ▶, was transfected into DT3 cells. Total RNA was extracted and analyzed with the Invader RNA assay, RNase protection assay, or RT-PCR to quantify U-IIIb-IIIc-D RNA (gray bars), U-IIIb-D RNA (white bars), or U-IIIc-D RNA (black bars). Error bars represent one standard deviation. The percent inclusion of a product (e.g., U-IIIb-D) among transcripts was calculated as follows: percent product (e.g., U-IIIb-D) inclusion = {[product (e.g., U-IIIb-D)]/([U-IIIb-D)] + [U-IIIc-D] + [U-IIIb-IIIc-D])} × 100. This RPA cannot accurately quantify the skipped product (U-D) because the probe products protected by this splice variant were also generated from the protection of other spliced products (i.e., U-IIIb-D and U-IIIc-D).

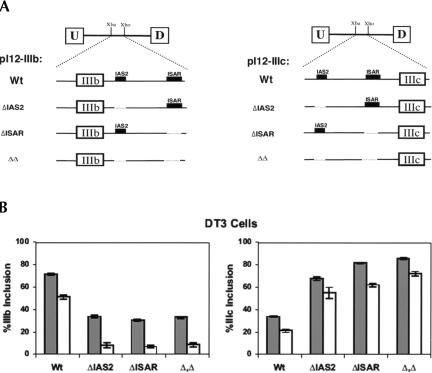

The cell-type-specific regulation of FGFR2 alternative splicing was previously shown to be controlled by several cis-elements. Among these, ISAR activates exon IIIb and silences exon IIIc in DT3 cells (Fig. 1 ▶; Carstens et al. 1998). Data of others had suggested that IAS2 works in concert with ISAR to activate IIIb in cells of epithelial origin (Fig. 1 ▶; Del Gatto et al. 1997). The requirements for IAS2 and ISAR were tested using the Invader RNA assay and RT-PCR. Once again, the observed trends for the Invader RNA assay generally corresponded with previous and current RT-PCR results (Fig. 4 ▶). In AT3 cells, deletion of either IAS2 (ΔIAS2), ISAR (ΔISAR), or both (Δ,Δ) had no perceptible effect on the percent inclusion of IIIb or IIIc (Fig. 4C ▶, first and second panels), which was expected. In DT3 cells, however, ΔIAS2, ΔISAR, or Δ,Δ led to a significant decrease in the expression of U-IIIb-D and increased expression of U-IIIc-D (Fig. 4B ▶; first and second panels). Interestingly, deletion of IAS2 led not only to increased levels of U-IIIc-D, but also of U-IIIb-IIIc-D. This is the first evidence implicating IAS2 in the repression of exon IIIc.

To distinguish between the role of IAS2 in IIIb activation and IIIc repression, we transfected DT3 cells with single exon minigene constructs (see schematics of pI12-IIIb and pI12-IIIc minigene constructs in Fig. 6A ▶). We had previously employed similar single-exon minigenes (constructs that contain either IIIb or IIIc) to show that ISAR was independently required for the activation of IIIb and the repression of IIIc (Fig. 6A ▶; Carstens et al. 1998). Deletion of IAS2 in the context of the single-exon minigene constructs had no effect in AT3 cells (data not shown), but in DT3 cells, this deletion decreased IIIb inclusion and independently increased IIIc inclusion. These trends were observed using both the Invader RNA assay (gray bars) and RT-PCR (white bars) and established that IAS2 can mediate repression of exon IIIc in epithelial cells.

FIGURE 6.

IAS2 represses the IIIc exon in epithelial cells. (A) Schematic of single-exon minigene constructs used to study the inclusion of exon IIIb and the repression of exon IIIc in DT3 cells. The presence or absence of IAS2 and ISAR is indicated. The IIIb minigenes can direct the expression of two RNAs produced by alternative splicing: skipping of IIIb leads to the U-D RNA and the inclusion of IIIb leads to the U-IIIb-D RNA. The IIIc minigenes can direct the expression of two RNAs produced by alternative splicing: skipping of IIIc leads to the U-D RNA and the inclusion of IIIc leads to the U-IIIc-D. (B) DT3 cells were transfected with the minigene constructs in A, and total RNA was extracted and analyzed with either the Invader RNA assay (gray bars) or semiquantitative RT-PCR (white bars) for the presence of the RNA variants. Error bars represent one standard deviation. In B the percent inclusion of a product (e.g., U-IIIb-D) among transcripts was calculated as follows: percent product (e.g., U-IIIb-D) inclusion = {[product (e.g., U-IIIb-D)]/([U-D] + [U-IIIb-D])} × 100.

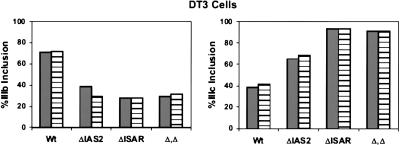

Given the ability of the Invader RNA assay to specifically quantify alternatively spliced RNA variants and prior reports that the assay could be carried out using crude cell lysates (Eis et al. 2001), we wanted to test whether alternative FGFR2 transcripts could be measured without the need to purify cellular RNA. Crude cell lysates and purified RNA samples were prepared from DT3 cells transfected with the single-exon minigene constructs, which have either IIIb or IIIc as a single internal exon (Fig. 6A ▶), and the splicing products were quantified with the Invader RNA assay. This experiment demonstrated nearly identical results from purified RNA and crude cell lysates (Fig. 7 ▶). The use of cell lysates saves several hours of sample preparation and provides accurate monitoring of gene expression and alternative splicing in a simple, high-throughput format.

FIGURE 7.

The Invader RNA assay accurately reports levels of FGFR2 alternatively spliced RNAs in crude cell extracts. DT3 cells were transfected with the single-exon minigene constructs described in Figure 6 ▶, and either purified total RNA (gray bars) or crude cell lysates (striped bars) were analyzed for the presence of U-D, U-IIIb-D (left panel), or U-IIIc-D RNAs (right panel). The percent inclusion of a product among transcripts was calculated as in Figure 6 ▶.

The functional implications of the high frequency of alternative splicing among human transcripts are far-reaching. Thus, there is a need for RNA assays that are not only quantitative, but that are also specific, because alternatively spliced variants can differ by very few nucleotides. Such high-resolution analysis of gene expression profiles for differentially spliced mRNA variants will provide insight into this complex phenomenon. In this article, we investigated the potential of the Invader RNA assay to report on alternative splicing. The Invader RNA assay confirmed our suspicion that RT-PCR consistently overrepresented the skipped product and skewed the results accordingly. This propensity of PCR to favor smaller products is a problem in all PCR reactions, including QRT-PCR, where different products are in competition. The accurate quantification of FGFR2 alternative splicing by the Invader RNA assay permitted the detection of significant levels of IIIb-IIIc double-exon inclusion. This finding suggests that the repression of exon IIIc in epithelium (Carstens et al. 1998) and of exon IIIb in mesenchyme (Wagner and Garcia-Blanco 2002) may not be as tightly controlled as previously thought. If true for endogenous FGFR2, this indicates that RNA surveillance mechanisms must dispose of significant levels of FGFR2 transcripts that include both IIIb and IIIc (Jones et al. 2001). These studies clearly establish the significant value of the Invader RNA assay in the study of alternative splicing.

Although selection of specific Invader assay probe sets can be more complex than the selection of RT-PCR primers, the assay offers some significant advantages. The Invader RNA assay not only exhibits remarkable isoform discrimination, but it is also highly quantitative and sensitive, routinely detecting 0.005–0.05 amole of transcript (Fig. 3 ▶; data not shown). Accurate quantification is achieved through its linear signal amplification mechanism, which can reproducibly detect a 1.2-fold change in RNA (Eis et al. 2001). In the present study, the Invader RNA assay was performed in a biplex detection format, thus enabling the quantification of an included exon relative to an internal control (e.g., U-D) in the same sample. This type of measurement affords additional accuracy in the analysis of the splice variant profiles. An added advantage over most other methods is the capacity to carry out the assay in crude cell lysates, which saves time and reduces errors associated with increased manipulations. The data presented in this report demonstrate that the Invader RNA assay is a valuable tool for the investigation of alternative splicing.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Minigene constructs and in vitro transcript generation

Short transcripts (containing only the regions essentially complementary to the oligonucleotides) were used for all standard curves except those generated for the discrimination experiments, which used full-length transcript standards. The short and full-length transcripts performed equivalently in the Invader RNA assay (data not shown). For generation of the short transcript standards, two synthetic oligonucleotides containing the T7 promoter and the regions of complementarity to the oligonucleotides for each assay were annealed. To generate the full-length transcripts, which span the exon–exon junctions shown in Figure 2 ▶, double-exon minigene constructs (Fig. 4A ▶) or single-exon minigene constructs (Fig. 6A ▶) were obtained by cloning PCR products of genomic segments of the rat FGFR2 gene into the pI-12 vector as described in Carstens et al. (1998). The sequences of all oligonucleotides used for cloning will be available upon request. The minigene constructs, which contain a T7 or T3 promoter, were linearized with either HindIII or ApaI, and served as templates for in vitro transcription. Transcription reactions were performed using the T7 Ribomax Large Scale RNA Production System (Promega Corporation) or the T3 MEGAshortscript in vitro transcription kit (Ambion). The sequences of the full-length RNAs will be made available upon request. The transcripts were purified using Trizol Reagent (Invitrogen Corporation) or gel purified on denaturing polyacrylamide gels and quantified by A260 measurement. All transcripts were diluted with 20 ng/μL transfer RNA (tRNA; Sigma) or 1× Cell Lysis Buffer (20 mM Tris at pH 8.0, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.5% NP-40, 20 ng/μL tRNA; Third Wave Technologies, Inc.).

Transfections, cell lysates, and isolation of cellular RNA

The growth and transfection of DT3 and AT3 cells and the isolation of total cellular RNA were performed as previously described by Wagner and Garcia-Blanco (2002). Cell lysates samples were prepared as previously described by Eis et al (2001). Assays were performed using either total RNA (50–200 ng) or cell lysates samples prepared from approximately 900 cells. A twofold dilution series of the lysates was always carried out to insure that the assay was in the linear range.

Invader RNA assay and semiquantitative RT-PCR

The Invader RNA assay was carried out as described in Eis et al. (2001) except 1 μM probe was used for all probe sets and 0.25 μM of Invader oligonucleotide was used for the IIIb-IIIc and U-IIIc probe sets. Invader RNA Assay Generic Reagents (Third Wave Technologies, Inc.), which includes buffers and the Cleavase enzyme, were used for all assays. Buffer conditions for the primary and secondary reactions are described by Eis et al. (2001) and the Cleavase enzyme (Third Wave Technologies, Inc.) concentration in the primary reaction is 2 ng/μL.

The four RNA variants were quantified with the biplex format of the Invader RNA assay (Eis et al. 2001), using the following probe set combinations: U-D/IIIb-D and IIIb-IIIc/U-IIIc (for double inclusion IIIb-IIIc minigene constructs), U-D/IIIb-D (for single inclusion IIIb minigene construct), or U-D/IIIc-D (for single inclusion IIIc minigene construct). Briefly, the Invader assays were performed by combining 5 μL of no target control, in vitro transcript control, or RNA sample (total RNA or cell lysates), with 5 μL of primary reaction mix (containing probes, stacking oligonucleotides, Invader oligonucleotides, primary reaction buffer, and Cleavase enzyme) in a 96-well, 0.2-mL polypropylene microplate (MJ Research). Reactions were incubated in a PTC-100 thermal cycler (MJ Research) for 90 min at 60°C. Following the primary reaction incubation, 5 μL of secondary reaction mix (containing FRET oligonucleotides, arrestor oligonucleotides, and buffer) were added to the wells and the reactions were incubated for an additional 60 min. Fluorescence was measured directly at the end of the incubation period using a CytoFluor 4000 fluorescence plate reader Applied Biosystems). The settings used were: 485/20 nm excitation/bandwidth and 530/25 nm emission/bandwidth for FAM dye detection, and 560/20 nm excitation/bandwidth and 620/40 nm emission/bandwidth for Red dye detection. Semiquantitative RT-PCR was carried out as previously described (Carstens et al. 1998; Wagner and Garcia-Blanco 2002). All oligonucleotides used in the Invader RNA assays are listed in Table 1 ▶.

RNase protection assay

RNase protection assay probes were generated from plasmid pB68.8. This plasmid was derived by cloning a U-IIIb-IIIc-D cDNA (spanning from the EcoRI site in the U exon to the Acc65I site in the D exon) into pDP19 (Ambion). pB68.8 was linearized with BamHI, and α[32P]UTP labeled probes were generated with T7 RNA polymerase. Approximately 5,000–10,000 cpm of probe and 10 μg of each sample RNA were coprecipitated and resuspended in 20 μL of 40 mM PIPES (pH 6.4), 500 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, and 80% formamide. Samples were heated to 95°C for 5 min and incubated at 65°C overnight. Annealed samples were digested in reactions containing 300 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 10 mM EDTA, 10 μg/mL salmon sperm DNA, and RNase Cocktail (Ambion) for 1 h at 37°C. RNases were inactivated and RNA was precipitated with 800 μL inactivation/precipitation solution (1.75 M guanidine isothiocyanate, 0.22% n-lauroyl sarcosine, 11 mM sodium citrate, 44 mM β-mercaptoethanol and 56% isopropanol; Harju and Peterson 2001). Protected fragments were resolved on 8% denaturing acrylamide gels. The RPA was unable to accurately quantify the skipped product (U-D) because the probe products protected by this splice variant were also generated from the protection by U-IIIb-D and U-IIIc-D RNAs.

Acknowledgments

We thank David Mauger for critical reading of the manuscript and members of the Garcia-Blanco laboratory, especially Erika Lasda, for important suggestions. We thank James Dahlberg, Marilyn Olson, Tsetska Takova, Victor Lyamichev, and Laura Heisler for insightful discussions and revisions of the manuscript. We thank Annette Kennett for her help in the preparation of the manuscript. The work in the Garcia-Blanco laboratory was funded by a grant from the NIH (GM63090). M.A.G.-B. was a scholar of the Raymond and Beverly Sackler Foundation. E.J.W. acknowledges the support of a Department of Defense predoctoral fellowship.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked ``advertisement'' in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Article and publication are at http://www.rnajournal.org/cgi/doi/10.1261/rna.5840803.

REFERENCES

- Black, D.L. 2000. Protein diversity from alternative splicing: A challenge for bioinformatics and post-genome biology. Cell. 103: 367–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carstens, R.P., Eaton, J.V., Krigman, H.R., Walther, P.J., and Garcia-Blanco, M.A. 1997. Alternative splicing of fibroblast growth factor receptor 2 (FGF-R2) in human prostate cancer. Oncogene 15: 3059–3065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carstens, R.P., McKeehan, W.L., and Garcia-Blanco, M.A. 1998. An intronic sequence element mediates both activation and repression of rat fibroblast growth factor receptor 2 pre-mRNA splicing. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18: 2205–2217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carstens, R.P., Wagner, E.J., and Garcia-Blanco, M.A. 2000. An intronic splicing silencer causes skipping of the IIIb exon of fibroblast growth factor receptor 2 through involvement of polypyrimidine tract binding protein. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20: 7388–7400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cartegni, L. and Krainer, A.R. 2002. Disruption of an SF2/ASF-dependent exonic splicing enhancer in SMN2 causes spinal muscular atrophy in the absence of SMN1. Nat. Genet. 30: 377–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cartegni, L., Chew, S.L., and Krainer, A.R. 2002. Listening to silence and understanding nonsense: Exonic mutations that affect splicing. Nat. Rev. Genet. 3: 285–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Arruda, M., Lyamichev, V.I., Eis, P.S., Iszczyszyn, W., Kwiatkowski, R.W., Law, S.M., Olson, M.C., and Rasmussen, E.B. 2002. Invader technology for DNA and RNA analysis: Principles and applications. Expert Rev. Mol. Diagn. 2: 487–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Moerlooze, L., Spencer-Dene, B., Revest, J., Hajihosseini, M., Rosewell, I., and Dickson, C. 2000. An important role for the IIIb isoform of fibroblast growth factor receptor 2 (FGFR2) in mesenchymal–epithelial signalling during mouse organogenesis. Development 127: 483–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Gatto, F., Plet, A., Gesnel, M.C., Fort, C., and Breathnach, R. 1997. Multiple interdependent sequence elements control splicing of a fibroblast growth factor receptor 2 alternative exon. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17: 5106–5116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eis, P.S., Olson, M.C., Takova, T., Curtis, M.L., Olson, S.M., Vener, T.I., Ip, H.S., Vedvik, K.L., Bartholomay, C.T., Allawi, H.T., et al. 2001. An invasive cleavage assay for direct quantitation of specific RNAs. Nat. Biotechnol. 19: 673–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh, S.S., Eis, P.S., Blumeyer, K., Fearon, K., and Millar, D.P. 1994. Real time kinetics of restriction endonuclease cleavage monitored by fluorescence resonance energy transfer. Nucleic Acids Res. 22: 3155–3159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall, J.G., Eis, P.S., Law, S.M., Reynaldo, L.P., Prudent, J.R., Marshall, D.J., Allawi, H.T., Mast, A.L., Dahlberg, J.E., Kwiatkowski, R.W., et al. 2000. Sensitive detection of DNA polymorphisms by the serial invasive signal amplification reaction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 97: 8272–8277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harju, S. and Peterson, K.R. 2001. Sensitive ribonuclease protection assay employing glycogen as a carrier and a single inactivation/precipitation step. Biotechniques 30: 1199–1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones, R.B., Wang, F., Luo, Y., Yu, C., Jin, C., Suzuki, T., Kan, M., and McKeehan, W.L. 2001. The nonsense-mediated decay pathway and mutually exclusive expression of alternatively spliced FGFR2IIIb and -IIIc mRNAs. J. Biol. Chem. 276: 4158–4167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser, M.W., Lyamicheva, N., Ma, W., Miller, C., Neri, B., Fors, L., and Lyamichev, V.I. 1999. A comparison of eubacterial and archaeal structure-specific 5′-exonucleases. J. Biol. Chem. 274: 21387–21394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyamichev, V., Mast, A.L., Hall, J.G., Prudent, J.R., Kaiser, M.W., Takova, T., Kwiatkowski, R.W., Sander, T.J., de Arruda, M., Arco, D.A., et al. 1999. Polymorphism identification and quantitative detection of genomic DNA by invasive cleavage of oligonucleotide probes. Nat. Biotechnol. 17: 292–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyamichev, V.I., Kaiser, M.W., Lyamicheva, N.E., Vologodskii, A.V., Hall, J.G., Ma, W.P., Allawi, H.T., and Neri, B.P. 2000. Experimental and theoretical analysis of the invasive signal amplification reaction. Biochemistry 39: 9523–9532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma, W.P., Kaiser, M.W., Lyamicheva, N., Schaefer, J.J., Allawi, H.T., Takova, T., Neri, B.P., and Lyamichev, V.I. 2000. RNA template-dependent 5′ nuclease activity of Thermus aquaticus and Thermus thermophilus DNA polymerases. J. Biol. Chem. 275: 24693–24700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miki, T., Fleming, T.P., Bottaro, D.P., Rubin, J.S., Ron, D., and Aaronson, S.A. 1991. Expression cDNA cloning of the KGF receptor by creation of a transforming autocrine loop. Science 251: 72–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modrek, B. and Lee, C. 2002. A genomic view of alternative splicing. Nat. Genet. 30: 13–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savkur, R.S., Philips, A.V., and Cooper, T.A. 2001. Aberrant regulation of insulin receptor alternative splicing is associated with insulin resistance in myotonic dystrophy. Nat. Genet. 29: 40–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, E.J. and Garcia-Blanco, M.A. 2001. Polypyrimidine tract binding protein antagonizes exon definition. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21: 3281–3288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ———. 2002. RNAi-mediated PTB depletion leads to enhanced exon definition. Mol. Cell. 10: 943–949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan, G., Fukabori, Y., McBride, G., Nikolaropolous, S., and McKeehan, W.L. 1993. Exon switching and activation of stromal and embryonic fibroblast growth factor (FGF)-FGF receptor genes in prostate epithelial cells accompany stromal independence and malignancy. Mol. Cell. Biol. 13: 4513–4522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]