Abstract

microRNAs (miRNAs) are 21–22-nucleotide noncoding RNAs that are widely believed to regulate complementary mRNA targets. However, due to the modest amount of pairing involved, only a few out of the hundreds of known animal miRNAs have thus far been connected to mRNA targets. Here, we considered the possibility that miRNAs might regulate non-mRNA targets, namely other miRNAs. To do so, we conducted a systematic assessment of the nearly complete catalogs of animal miRNAs for potential miRNA:miRNA complements. Our analysis uncovered several compelling examples that strongly suggest a function for miRNA duplexes, thus adding a potential layer of regulatory sophistication to the small RNA world. Interestingly, the most striking examples involve miRNAs complementary to members of the K-box family and Brd-box family, two classes of miRNAs previously implicated in regulation of Notch target genes. We emphasize that patterns of nucleotide constraint indicate that miRNA complementarity is not a simple consequence of miRNA:miRNA* complementarity; however, our findings do suggest that the potential regulatory consequences of the latter also deserve investigation.

Keywords: microRNA, miRNA, miRNA*, RNA duplex

INTRODUCTION

microRNAs (miRNAs) are an abundant class of 21–22-nucleotide (nt) noncoding RNAs found in higher eukaryotes. Both experimental and computational strategies have recently been harnessed to identify several hundred miRNAs from diverse species of plants and animals (for review, see Lai 2003). One of their defining features is that they derive from precursor transcripts (pre-miRNAs) with an extended hairpin structure. Pre-miRNAs are processed by the RNAse III enzyme Dicer, which also cleaves long, perfectly double-stranded RNA into 21–22-nucleotide (nt) siRNA duplexes (for review, see Hannon 2002). In contrast to siRNAs, only a single strand of the processed pre-miRNA is predominantly stable. However, the rare non-miRNA cleavage products, termed miRNA* species, are occasionally cloned. Alignment of corresponding miRNA:miRNA* sequences within their parental pre-miRNAs suggests that they are excised as a duplex RNA with 2-nt 3′ overhangs, similar to siRNA duplexes (Elbashir et al. 2001; Lau et al. 2001; Lim et al. 2003).

Mature miRNAs reside in the microRNP complex, likely the same as the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC), which regulates endogenous mRNA targets containing miRNA-complementary sequences (Hutvagner and Zamore 2002; Mourelatos et al. 2002). In plants, miRNA:mRNA pairing is often quite extensive and leads to target cleavage and subsequent mRNA degradation (Llave et al. 2002; Rhoades et al. 2002; Kasschau et al. 2003; Tang et al. 2003). In contrast, animal miRNAs display only limited complementarity with their known mRNA targets, and instead mediate translational inhibition (Lee et al. 1993; Wightman et al. 1993; Reinhart et al. 2000; Brennecke et al. 2003). The modest amount of pairing involved has hindered the informatic matching of animal miRNAs to their mRNA targets, and discovery of most known examples was guided by genetic evidence.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The possibility that miRNAs might regulate non-mRNA targets has not yet been addressed. We considered whether some miRNAs might regulate other miRNAs, a situation that might be detected by unusual patterns of miRNA complementarity. To do so, we employed a Smith-Waterman algorithm with a scoring matrix modified to permit G:U basepairing, and subjected the largely complete sets of nematode, fly, and vertebrate miRNAs (curated by the miRNA Registry, http://www.sanger.ac.uk/Software/Rfam/mirna/) to systematic pairwise antisense comparison. We performed a Monte Carlo analysis to assess the probability of observed miRNA complements by analyzing 300 million pairs of simulated 21-nt miRNAs that were randomly generated using the nucleotide frequencies from the cloned miRNAs. The results of this analysis are available at ftp://ftp.fruitfly.org/pub/people/cwiel/miRNA.

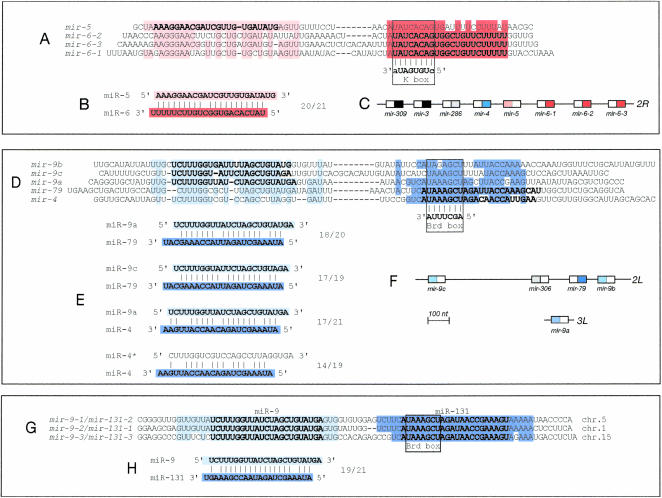

Unexpectedly, the two most statistically significant groups of complementary miRNAs involve two families of Drosophila miRNAs previously implicated in regulation of Notch target genes (Lai 2002). These are the K-box family miRNAs miR-6-1, 6-2, and 6-3, which are complementary to miR-5 (Fig. 1A,B ▶), and the Brd-box family miRNAs miR-4 and miR-79, which display complementarity to miR-9a, -9b, and -9c (Fig. 1D,E ▶). K-box miRNAs are defined by a UAUCACAG motif at their 5′ termini (proposed to recognize the extended K-box motif CUGUGAUA found in the 3′ untranslated regions [UTRs] of target transcripts), whereas Brd-box miRNAs are defined by a UAAAGCU motif near their 5′ termini (proposed to recognize the 3′ UTR Brd-box motif AGCUUUA; Lai 2002). The degree of complementarity between members of these particular miRNA sets is impressive. For example, miR-5:miR-6 are complementary at 20/21 nt (Fig. 1B ▶), and miR-9a:miR-79 are complementary at 18/20 positions (Fig. 1E ▶). Remarkably, most of these particular miRNAs display as much or greater complementarity to each other than they do to any 3′ UTR in the Drosophila genome (Stark et al. 2003; E. Lai, C. Wiel, and G. Rubin, unpubl.). We also note that putative miRNA:miRNA duplexes usually have 3′ overhangs, similar to siRNA duplexes.

FIGURE 1.

Subsets of Drosophila miRNAs are highly complementary to each other. (A) Alignment of the K box-related pre-miRNA sequences for mir-5, mir-6-1, mir-6-2, and mir-6-3; the K box-complementary signature (UAUCACAG) is boxed. The nucleotides in bold indicate the mature miRNAs; thus, miR-5 derives from the left arm of its precursor and miR-6 from the right arms of the three mir-6 genes. Shaded regions highlight similarity between mature miRNAs and corresponding miRNA* regions, with the miR-5-similar region in light red and the miR-6-similar region in dark red. (B) Proposed miR-5:miR-6 duplex. As the three mir-6 genes produce identical miRNAs, only one alignment is shown. miR-5 also shows complementarity to other members of the K-box miRNA family, albeit to a lesser extent (data not shown). (C) The mir-5 and mir-6 genes reside in a gene cluster containing other non-K-box family miRNAs; these include the Brd-box family gene mir-4 and two others that form their own subfamily, miR-309 and miR-3 (shaded black). (D) Alignment of Brd box-related miRNAs. Mature miRNAs are in bold; the Brd box-complementary signature (UAAAGCU) is boxed. Blue shading highlights similarity between mature miRNAs and corresponding miRNA* regions, with miR-9-similar sequences in light blue and miR-4/miR-79-similar sequences in dark blue. (E) Examples of miRNA complements among the set of Brd box-related miRNAs. Comparison with the miR-4:miR-4* duplex shows that miR-4 is more complementary to miR-9a than to its own miRNA* species. (F) Complementary Brd box-related miRNAs reside in a gene complex with one unrelated miRNA (mir-306); mir-9a and mir-4 are located elsewhere in the genome. (G) Mammalian miR-9 and miR-131, members of the Brd box-related family, potentially derive from the same pre-miRNAs; chromosome positions are for the human loci. (H) Proposed miR-9:miR-131 duplex.

Members of these complementary miRNA groups are clearly related by ancestry: they display similarity across the entirety of their respective precursors, and complementary miRNAs derive from opposite arms of the pre-miRNA hairpin (i.e., the three miR-9 sequences derive from the left arm of their pre-miRNAs, whereas miR-4 and miR-79 come from the right arms of their precursors). Indeed, mir-5 even preserves the extended K-box signature at the 5′ end of its inferred miRNA* sequence (Fig. 1A ▶), whereas mir-9a and mir-9c both preserve Brd-box signatures at the 5′ ends of their presumed miRNA* sequences (Fig. 1D ▶). This suggests that mir-5 and the three mir-9 genes arose from duplicated K-box and Brd-box miRNAs that evolved to produce functional miRNAs from their original miRNA* products. This phylogeny is consistent with the residence of many members of these complementary sets in miRNA gene complexes (Fig. 1C,F ▶; Lagos-Quintana et al. 2001; Aravin et al. 2003; Lai et al. 2003).

It is important to note that no miRNA* species have been cloned for any of the miRNAs in this set, with the sole exception of miR-4*. This point is especially relevant to miR-5 and miR-6, which are the most complementary miRNAs encoded by the fly genome. miR-5 has been cloned 12 times and miR-6 38 times, exclusive of any miRNA* species, and the specific accumulation of these miRNAs has been confirmed by Northern analysis (Lagos-Quintana et al. 2001; Aravin et al. 2003). Thus, it is not the case that miR-5 is actually a homolog of miR-6 that has inappropriately been defined by a miRNA* species. The patterns of pre-miRNA nucleotide conservation of Brd box-related miRNAs also supports the identity of the cloned sequences as functional miRNAs (Lai et al. 2003).

The existence of these miRNA complements might in theory be trivially based upon the fact that miRNA* species exhibit significant complementarity to their cognate miRNAs. Three observations suggest that this explanation is insufficient. First, these miRNAs are only loosely related to the inferred miRNA* sequences of miRNAs with which they exhibit complementarity. For example, miR-5 is only moderately related to any of the three inferred miR-6* sequences (Fig. 1A ▶, light red shading), even though it is nearly perfectly complementary to miR-6. Second, most of these miRNAs show more pairing with a complementary miRNA than they do to their own miRNA* species. For instance, miR-9c is more complementary to miR-79 than it is to the inferred miR-9c* sequence, and miR-4 is far more complementary to miR-9 than it is to the cloned miR-4* (Fig. 1E ▶; data not shown). Third, complementarity of Brd box-related miRNAs has been conserved over Dipteran and Hymenopteran evolution (Lai et al. 2003), and has been maintained even after dispersal of the Brd box-related miRNA genes throughout the genome (Fig. 1C,F ▶).

Taken together, these observations strongly suggest that the phenomenon of miRNA complementarity described here also involves active evolution towards a complementary state, a process likely to be driven by some functional consequence of miRNA duplex formation. As at least subsets of these complementary miRNAs are probably cotranscribed and are thus very likely to be present in the same cells (i.e., miR-5/miR-6 [Fig. 1C ▶] and miR-9c/miR-79/miR-9b [Fig. 1F ▶]), the proposed miRNA duplexes have the opportunity to form in vivo. A plausible hypothesis is that miRNA duplexes, possibly complexed with the RISC, could sequester K- or Brd-box family miRNAs from their corresponding mRNA targets. In fact, the presence of centrally located nucleotide mismatches in most of the proposed miRNA duplexes could “poison” the complex by inhibiting RISC-mediated cleavage of such duplexes. Alternatively, because uncapped and unadenylated single-stranded RNAs are rapidly degraded, miRNA duplex formation might actually increase the stability of free miRNAs and potentially promote their re-incorporation into the RISC. Of course, we cannot at this point rule out the possibility that an ancestral miRNA produced functional miRNAs from both arms, but that its duplicated descendants lost this ability on opposite arms. In this scenario, miRNA complementary might then be a consequence of the constraint imposed by miRNA- and miRNA*-pairing with their respective mRNA targets. Therefore, demonstration of the biological relevance and/or function of miRNA:miRNA duplexes awaits experimental tests.

The proposition of miRNA:miRNA duplexes raises the issue of whether miRNA* species ever regulate their cognate miRNAs, with which they necessarily share considerable complementarity. In principle, a regulatory function for miRNA* species might be related to the fact that certain miRNA* species are reasonably abundant (Lim et al. 2003). In this regard, it may be relevant that the only Drosophila miRNA* species that have been cloned more than once thus far derive from the K-box family gene mir-2a-2 (cloned at a cumulative ratio of 18:4) and the Brd-box family gene mir-4 (cloned 20:2), even though these are not the most abundantly cloned miRNAs (Lagos-Quintana et al. 2001; Aravin et al. 2003). It is reasonable to imagine that evolution of increased miRNA* stability would have preceded the miRNA-arm switching that resulted in evolution of miR-5 from a K-box family miRNA and the miR-9 genes from a Brd-box family miRNA. Recent studies indicate that the instability of most miRNA* species is due to asymmetric incorporation of Dicer cleavage products into the RISC. This is heavily influenced by the relative stability of either end of the diced miRNA:miRNA* duplex, as the 5′ end that is more easily unwound is preferentially incorporated into RISC (Khvorova et al. 2003; Schwarz et al. 2003). Base changes at the ends of the miRNA:miRNA* duplex could therefore underlie miRNA strand switching.

A further indication that miRNA* species could have regulatory potential comes from examination of vertebrate Brd box-related miRNAs. miR-131 is a vertebrate Brd-box family miRNA (containing the 5′ motif UAAAGCU) and potential homolog of miR-79, whereas vertebrate miR-9 is orthologous to fly miR-9. Each has been cloned multiple times from mouse brain (Lagos-Quintana et al. 2002), and as in Drosophila, vertebrate miR-9 and miR-131 are highly complementary to each other (Fig. 1H ▶). However, inspection of their pre-miRNAs reveals that mature miR-9 and miR-131 sequences are actually present in the left and right arms of the same three pre-miRNAs, respectively (Fig. 1G ▶). The observations that vertebrate miR-9 was cloned more often than miR-131 (at a ratio of 11:3) and is identical to fly miR-9 have led to the recent re-assessment of miR-131 as a miR-9* species by the miRNA registry. Nevertheless, as miRNA* sequences tend to diverge rapidly (i.e., mir-6-1, -6-2, and -6-3 and mir-9a, -9b, and 9c), it is notable that the three pre-mir-9/mir-131 genes maintain perfect conservation of both precursor arms. Indeed, the findings that mature miR-131 is easily detected by Northern analysis (Lagos-Quintana et al. 2002), is homologous to miRNAs found in worms and flies, and is a member of a miRNA family that has been linked to an identified 3′ UTR regulatory element (Lai 2002), all strongly argue that it is a “genuine” miRNA. Overall, we suggest that a functional role for miRNA duplexes may underlie these unusual characteristics of miR-9/miR-131.

These examples are the only complementary miRNAs so clearly related by ancestry. The biological relevance of other examples of miRNAs that have converged upon reasonably complementary sequences is not so easily evaluated at present, especially as it is not currently possible to determine whether any of them are coexpressed on a cell-by-cell basis during normal development. However, it is worth noting that several other examples (data available at the ftp site) exhibit complementarity that is comparable to or greater than known miRNA:mRNA target pairs, and may thus warrant further examination. Moreover, we hope that these observations will encourage a broader survey of potential miRNA targets to include other RNA genes. Efforts thus far have focused exclusively on mRNAs (Rhoades et al. 2002; Stark et al. 2003), but it is clear that a significant portion of eukaryotic transcriptomes consist of noncoding RNA genes (for review, see Huttenhofer et al. 2002).

The identification of multiple classes of highly complementary miRNAs introduces a potential layer of regulatory complexity to the small RNA world. It also suggests that processed miRNAs have the ability to “see” each other, although it is not clear whether this would manifest itself as free miRNA duplexes or as part of the RISC. More generally, we believe that miRNA complementarity may represent only one of many duplex RNA-related phenomena that remain to be characterized. For example, we previously reported that the mRNAs for many genes involved in neurogenesis form mRNA:mRNA duplexes via complementary 3′ UTR motifs (the proneural box and the GY box; Lai and Posakony 1998; Lai et al. 2000), in a way that is likely to have consequences for the proposed interaction of the GY box motif with a miRNA (Lai 2002). These observations suggest a network of functional interactions at the RNA level. In addition, the levels of plant miRNAs increase when the RISC is inhibited (Kasschau et al. 2003). Although the basis of this finding is unclear, it could theoretically reflect negative regulation of pre-miRNAs by miRNAs. These different duplex RNA phenomena await further characterization, and we expect the RNA world to hold additional surprises for the future.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute and by the Damon Runyon Cancer Research Foundation, DRG 1632.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Article and publication are at http://www.rnajournal.org/cgi/doi/10.1261/rna.5191904.

REFERENCES

- Aravin, A., Lagos-Quintana, M., Yalcin, A., Zavolan, M., Marks, D., Snyder, B., Gaasterland, T., Meyer, J., and Tuschl, T. 2003. The small RNA profile during Drosophila melanogaster development. Dev. Cell 5: 337–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennecke, J., Hipfner, D.R., Stark, A., Russell, R.B., and Cohen, S.M. 2003. bantam Encodes a developmentally regulated microRNA that controls cell Propiferation and regulates the proapoptotic gene hid in Drosophila. Cell 113: 25–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elbashir, S.M., Lendeckel, W., and Tuschl, T. 2001. RNA interference is mediated by 21- and 22-nucleotide RNAs. Genes & Dev. 15: 188–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannon, G.J. 2002. RNA interference. Nature 418: 244–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huttenhofer, A., Brosius, J., and Bachellerie, J.P. 2002. RNomics: Identification and function of small, nonmessenger RNAs. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 6: 835–843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutvagner, G. and Zamore, P.D. 2002. A microRNA in a multiple-turnover RNAi enzyme complex. Science 297: 2056–2060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasschau, K.D., Xie, Z., Allen, E., Llave, C., Chapman, E.J., Krizan, K.A., and Carrington, J.C. 2003. P1/HC-Pro, a viral suppressor of RNA silencing, interferes with Arabidopsis development and miRNA function. Dev. Cell 4: 205–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khvorova, A., Reynolds, A., and Jayasena, S. 2003. Functional siRNAs and miRNAs exhibit strand bias. Cell 115: 209–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagos-Quintana, M., Rauhut, R., Lendeckel, W., and Tuschl, T. 2001. Identification of novel genes coding for small expressed RNAs. Science 294: 853–858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagos-Quintana, M., Rauhut, R., Yalcin, A., Meyer, J., Lendeckel, W., and Tuschl, T. 2002. Identification of tissue-specific microRNAs from mouse. Curr. Biol. 12: 735–739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai, E.C. 2002. Micro RNAs are complementary to 3′ UTR sequence motifs that mediate negative posttranscriptional regulation. Nat. Genet. 30: 363–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai, E.C. 2003. microRNAs: Runts of the genome assert themselves. Curr. Biol. 13: R925–R936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai, E.C. and Posakony, J.W. 1998. Regulation of Drosophila neurogenesis by RNA:RNA duplexes? Cell 93: 1103–1104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai, E.C., Bodner, R., Kavaler, J., Freschi, G., and Posakony, J.W. 2000. Antagonism of Notch signaling activity by members of a novel protein family encoded by the Bearded and Enhancer of split gene complexes. Development 127: 291–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai, E.C., Tomancak, P., Williams, R.W., and Rubin, G.M. 2003. Computational identification of Drosophila microRNA genes. Genome Biol. 4: R42.41–R42.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau, N., Lim, L., Weinstein, E., and Bartel, D.P. 2001. An abundant class of tiny RNAs with probable regulatory roles in Caenorhabditis elegans. Science 294: 858–862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, R.C., Feinbaum, R.L., and Ambros, V. 1993. The C. elegans heterochronic gene lin-4 encodes small RNAs with antisense complementarity to lin-14. Cell 75: 843–854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim, L.P., Lau, N.C., Weinstein, E.G., Abdelhakim, A., Yekta, S., Rhoades, M.W., Burge, C.B., and Bartel, D.P. 2003. The microRNAs of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genes & Dev. 17: 991–1008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llave, C., Xie, Z., Kasschau, K.D., and Carrington, J.C. 2002. Cleavage of Scarecrow-like mRNA targets directed by a class of Arabidopsis miRNA. Science 297: 2053–2056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mourelatos, Z., Dostie, J., Paushkin, S., Sharma, A., Charroux, B., Abel, L., Rappsilber, J., Mann, M., and Dreyfuss, G. 2002. miRNPs: A novel class of ribonucleoproteins containing numerous microRNAs. Genes & Dev. 16: 720–728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinhart, B.J., Slack, F., Basson, M., Pasquinelli, A., Bettinger, J., Rougvie, A., Horvitz, H.R., and Ruvkun, G. 2000. The 21-nucleotide let-7 RNA regulates developmental timing in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature 403: 901–906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhoades, M.W., Reinhart, B.J., Lim, L.P., Burge, C.B., Bartel, B., and Bartel, D.P. 2002. Prediction of plant microRNA targets. Cell 110: 513–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz, D.S., Hutvagner, G., Du, T., Xu, Z., Aronin, N., and Zamore, P.D. 2003. Asymmetry in the assembly of the RNAi enzyme complex. Cell 115: 199–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stark, A., Brennecke, J., Russell, R.B., and Cohen, S.M. 2003. Identification of Drosophila microRNA targets. PLOS Biol. 1: (in press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Tang, G., Reinhart, B.J., Bartel, D.P., and Zamore, P.D. 2003. A biochemical framework for RNA silencing in plants. Genes & Dev. 17: 49–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wightman, B., Ha, I., and Ruvkun, G. 1993. Posttranscriptional regulation of the heterochronic gene lin-14 by lin-4 mediates temporal pattern formation in C. elegans. Cell 75: 855–862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]