Abstract

The jakobid flagellates are bacteriovorus protists with mitochondrial genomes that are the most ancestral identified to date, in that they most resemble the genomes of the α-proteobacterial ancestors of the mitochondrion. Because of the bacterial character of jakobid mitochondrial genomes, it was expected that mechanisms for gene expression and RNA structures would be bacterial in nature. However, sequencing of the mitochondrial genome of the jakobid Seculamonas ecuadoriensis revealed several apparent mismatches in the acceptor stems of two predicted tRNAs. To investigate this observation, we determined the cDNA sequences of these tRNAs by RT-PCR. Our results show that the last three positions of the 3′ extremity, plus the discriminator position of seryl and glutamyl tRNAs, are altered posttranscriptionally, restoring orthodox base-pairing and replacing the discriminator with an adenosine residue, in an editing process that resembles that of the metazoan Lithobius forficatus. However, the most 5′ of the edited nucleotides is occasionally left unedited, indicating that the editing mechanism proceeds initially by exonucleolytic degradation, followed by repair of the degraded region. This 3′ tRNA editing mechanism is likely distinct from that of L. forficatus, despite the apparent similarities between the two systems.

Keywords: RNA editing, jakobids, tRNA processing, tRNA repair, evolution

INTRODUCTION

The jakobid flagellates are bacteriovorus, free-living protists, characterized by a ventral groove used for suspension feeding (O’Kelly 1993). Although the term “jakobids” is often used to refer to both the Malawimonadidae and the Jakobidae, the two groups are phylogenetically distinct, and this term will therefore be used exclusively to refer to the latter family. From an evolutionary perspective, one of the most interesting characteristics of the jakobids is the primitive nature of their mitochondrial genomes (mtDNAs). Reclinomonas americana, the best-studied member of the jakobids, has an mtDNA that resembles that of its α-proteobacterial ancestor to a greater extent than any other mtDNA published to date (Lang et al. 1997). The set of genes encoded by the mitochondrial genome of R. americana includes all mitochondrial genes identified in other organisms, as well as 19 additional protein-coding genes. Among these additional genes are several components involved in gene expression, such as the four subunits of a bacterial RNA polymerase (mitochondria in other species use a nucleus-encoded, phage-like RNA polymerase), and the elongation factor Tu. Indeed, many features of the mtDNA of R. americana, including a gene order that indicates the presence of bacterial operon-like gene clusters, an RNase P RNA subunit that meets the minimal bacterial consensus, the presence of Shine-Dalgarno motifs (Lang et al. 1997), and the presence of a derived tmRNA gene (Keiler et al. 2000; Jacob et al. 2004), indicate that its mitochondrial gene expression is bacterial in nature. Complete sequences have recently been determined for the mtDNAs of several other jakobids, including Seculamonas ecuadoriensis.

It was expected that the mtDNAs of these species would, similar to R. americana, closely follow bacterial mechanisms of gene expression, and that their mitochondrial rRNA and tRNA structures would be similar to those found in bacteria. However, sequencing results from S. ecuadoriensis indicate mismatches in the aminoacyl acceptor stems of two tRNA genes, encoding tRNASer and tRNAGlu, precluding orthodox tRNA folding. Because proper folding of tRNA molecules is essential for their function, it was suggested that the transcription products of these genes must be edited in order to restore proper base-pairing of the mature tRNAs.

RNA editing is defined as any modification of an RNA that results in a change in its primary nucleotide sequence relative to that encoded by the corresponding gene (Gray and Covello 1993). This set of processes has been identified in a wide variety of organisms (for a recent review, see Gott and Emeson 2000), predominantly in organelles. Cases of RNA editing that have been reported in other systems include the mammalian nuclear apolipoprotein B mRNA (Powell et al. 1987) and the human hepatitis delta virus (Zheng 1992). Editing of tRNAs was initially discovered in the mitochondrion of the amoeboid protist Acanthamoeba castellanii (Lonergan and Gray 1993), in which 12 tRNA genes were found to have mismatches in the first three bases of the acceptor stem. The repair of the mismatches by sequence alteration on the 5′ half of the acceptor stem has been demonstrated. A similar 5′ tRNA editing mechanism was found in chytridiomycete fungi (Laforest et al. 1997).

Some metazoan animals use a different approach to repair tRNA acceptor stem mismatches. In the mitochondria of these animals, a 3′ tRNA editing mechanism has been identified. This editing system clearly bears no mechanistic similarity to the systems identified in A. castellanii and in the chytrids. In Gallus gallus, in which mitochondrial tRNACys and tRNATyr overlap by a single G residue, tRNATyr is subject to an editing reaction that yields an A residue in the discriminator position in the place of this G (Yokobori and Pääbo 1997). In the squid Loligo bleekeri (Tomita et al. 1996) and the land snail Euhadra herklotsi (Yokobori and Pääbo 1995a), mismatched bases in the 3′ half of the acceptor stem, as well as the discriminator, are replaced with A residues to restore orthodox base-pairing. These results strongly suggest that 3′tRNA editing in these species involves the action of poly(A)polymerase. In the platypus Ornithorhyncus anatinus, a combination of C and A residues are used to replace mismatched bases (Yokobori and Pääbo 1995b), a result that implicates a modified form of tRNA nucleotidyl transferase (CCase), the enzyme responsible for the addition of CCA 3′ to the discriminator position. In Escherichia coli, in which the 3′-terminal CCA is genomically encoded, CCase can repair the CCA if it is degraded, although it is unable to repair the discriminator or upstream nucleotides (Preiss et al. 1961). The implication of CCase in metazoan mitochondrial 3′ tRNA editing is further supported by the results of Reichert and coworkers (Reichert et al. 1998; Reichert and Mörl 2000), who demonstrated that overlapping tRNA transcripts in human mitochondria are repaired by human mitochondrial S100 extract in vitro. This repair process also restores the overlapping discriminator A residue in vivo; however, in vitro, the extract had a greater affinity for C residues than for A when restoring the discriminator, much as CCase has a greater affinity for C than for A. These investigators also demonstrated that the human mitochondrial S100 extract not only is capable of repairing the discriminator position of overlapping tRNAs but also can repair 3′ degraded tRNAs. Although this repair mechanism is not technically a case of RNA editing, it is likely that the two processes are enzymatically related.

In the mitochondria of the centipede Lithobius forficatus, a more extensive form of 3′ tRNA editing has been identified. In this case, all four bases are used to repair acceptor stem mismatches. Equally interesting in L. forficatus is the observation that all 22 tRNAs encoded in the mtDNA would require editing to restore orthodox base-pairing (in eight of these tRNAs, editing has been demonstrated experimentally). The investigators suggest that 3′ tRNA editing in L. forficatus mitochondria is mechanistically distinct from the editing mechanisms described in mitochondria of other animals, in that it must use an RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp), instead of a template-independent CCase-like enzyme (Lavrov et al. 2000).

In this article, we describe a 3′ tRNA editing mechanism in the mitochondria of S. ecuadoriensis that superficially resembles that identified in L. forficatus, although the two systems have most likely evolved independently. Because RNA editing has generally been identified in the more derived organelles of eukaryotes, the discovery of such a mechanism in the mitochondria of a jakobid was completely unexpected.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Editing of mitochondrial seryl and glutamyl tRNAs in S. ecuadoriensis

We have identified 28 tRNA genes in the mtDNA of S. ecuadoriensis. Of these, the genes for tRNASer(GGA) and tRNAGlu(UUC) encode two and three mismatches, respectively, in the acceptor stem region. In addition, tRNACys(GCA) encodes a terminal G:U pair in the acceptor stem, and tRNAAla(UGC) contains two G:U pairs in the acceptor stem region, one of which (between G3 and U70) is a highly conserved structural determinant of this tRNA (Hou and Schimmel 1988). Interestingly, this position is edited in the 5′ portion of the acceptor stem to produce an A:U pair in the mitochondria of A. castellanii (Price and Gray 1999). Among the remaining tRNA genes, several acceptor stems contain G:U pairs, and some contain U:U pairs at positions near the base of the helix. These findings are summarized in Table 1 ▶.

TABLE 1.

Non–Watson-Crick base pairs in aminoacyl acceptor stems

| tRNA identity | Position |

| G:U pairs | |

| A(UGC) | 3:70, 5:68 |

| C(GCA) | 1:72 |

| F(GAA) | 7:66 |

| G(GCC) | 7:66 |

| K(UUA) | 2:71 |

| M(CAU)e | 2:71 |

| N(GUU) | 3:70 |

| V(UAC) | 2:71 |

| U:U pairs | |

| H(GUG) | 5:68 |

| L(GAG) | 6:67 |

| M(CAU)e | 6:67 |

| P(UGG) | 6:67 |

Shown here is a summary of unorthodox base pairs in the acceptor stems of inferred tRNAs in the mtDNA of S. ecuadoriensis. tRNAs are identified by one-letter amino acid codes, followed by the anticodon sequence. Positions of mispairings are given as 5′ base position: 3′ base position, and are numbered according to standard nomenclature. With the exception of those found in tRNASer and tRNAGlu, all unusual base pairs are G:U or U:U pairs. Acceptor stem mismatches in these two tRNAs are not indicated in this table, but are shown in Figure 2 ▶.

Whereas G:U pairs are common in functional mitochondrial tRNAs, the presence of mispairings suggested that they would have to be repaired by an editing mechanism to be functional. To determine whether the mismatches in seryl, glutamyl, cysteinyl, and alanyl tRNA acceptor stems are edited, cDNA sequences of these molecules were determined by using RT-PCR (Table 2 ▶). In addition, the sequence of tRNAHis was determined, showing that it is not edited and that its discriminator is incorporated in the 8-bp acceptor stem that is characteristic of tRNAHis structures. In contrast, in L. forficatus, following editing, tRNAHis has an additional noncanonical 3′ discriminator as well as the 8-bp acceptor stem (Lavrov et al. 2000). Our results show that the sequences of tRNASer and tRNAGlu differ from those of their corresponding genes. Inferred secondary structures of these tRNAs, indicating sites of editing, are shown in Figure 1 ▶. The mismatched nucleotides located in the 3′ portion of the acceptor stem of these tRNAs were found to be replaced with nucleotides that form orthodox Watson-Crick base pairs with the corresponding nucleotides in the 5′ portion of the acceptor stem. In both cases, the altered residues were restricted to the three final residues of the 3′ end of the acceptor stem. In addition, the discriminator position was replaced by an A in both cases. Because CCA was found to be added to both seryl and glutamyl tRNAs, they are presumably aminoacylated in vivo. These results demonstrate that a 3′ tRNA editing system is present in S. ecuadoriensis mitochondria.

TABLE 2.

Summary of sequencing results

| tRNA | Total | Completely edited | Partially edited | Unedited | % Partially edited | % Unedited |

| Alanine | 19 | 0 | 0 | 19 | 0 | 100% |

| Cysteine | 11 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 0 | 100% |

| Glutamate | 18 | 13 | 5 | 0 | 28% | 0% |

| Serine | 23 | 17 | 6 | 0 | 26% | 0% |

| Histidine | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 100% |

Shown here are total numbers of tRNA molecules sequenced. Also indicated are numbers of fully edited, partially edited, and unedited molecules for each tRNA species studied. Editing was only found in tRNASer and tRNAGlu, and in both cases, a number of partially edited molecules (i.e., unedited at the most upstream nucleotide) was found. tRNAAla, tRNAHis, and tRNACys were found to match the genomic sequence, although CCA was added to the molecule.

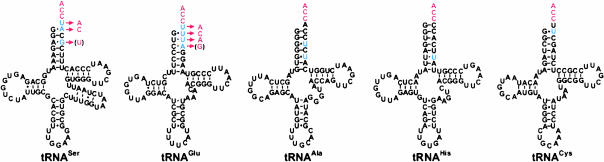

FIGURE 1.

Inferred tRNA secondary structures. tRNA secondary structures were inferred from primary mtDNA sequences. Shown here are secondary structures for tRNASer, tRNAGlu, tRNAAla, tRNAHis, and tRNACys. The genomic sequence is shown in black, with mismatches and unusual discriminators shown in blue. Nucleotide identities following editing are indicated in red; at partially edited positions, these nucleotides are enclosed by parentheses. Red arrows indicate editing.

Also shown in Figure 1 ▶ are inferred secondary structures of tRNAAla, tRNAHis, and tRNACys, for which the RNA-level sequences were found to be identical to the genomic sequence, despite the presence of G:U pairs among the three terminal bases in cysteinyl and alanyl tRNAs. Although the G3:U70 pair in the tRNAAla acceptor stem is a structural determinant, and it is therefore logical that it should retain its genomic identity, the presence of the terminal G:U pair in tRNACys is more surprising. Perhaps the destabilizing effect of this single mismatch is too mild to allow recognition of tRNACys by the editing complex. CCA was found to be added to the 3′ terminus of edited seryl and glutamyl tRNAs, as well as to tRNAHis, tRNACys, and tRNAAla.

Partial editing of tRNA molecules and mechanistic implications

In all sequenced clones, tRNASer and tRNAGlu were found to be edited. However, in some cases for both tRNASer and tRNAGlu, the furthest upstream of the mismatched nucleotides (G70 and A70, respectively, according to standard nomenclature) was found to have the mtDNA-encoded identity (G or A) rather than the edited identity (U or G); in other words, some tRNA molecules are only partially edited. The positions affected by partial editing are indicated in Figure 1 ▶.

Table 2 ▶ summarizes the totals for unmodified versus modified first position identity. The percentage of sequenced tRNASer molecules that was unmodified at this position was found to be 26%, whereas the percentage of partially edited tRNAGlu molecules was found to be 28%. These percentages were calculated based on the total of completely and partially edited tRNA molecules.

The observation that mismatched tRNA acceptor stems are frequently left unrepaired at position 70 suggests that mitochondrial 3′ tRNA editing in S. ecuadoriensis proceeds by 3′ exonucleolytic degradation, followed by resynthesis, possibly with the aid of the 5′ region as a template (Fig. 2A ▶). If this model is correct, the mismatch between positions 3 and 70 likely remains unedited due to a competition between the exonuclease and the repair enzyme. Such an editing system could have evolved as a repair mechanism for degraded 3′ termini that resulted in relaxed constraints on the 3′-terminal sequence.

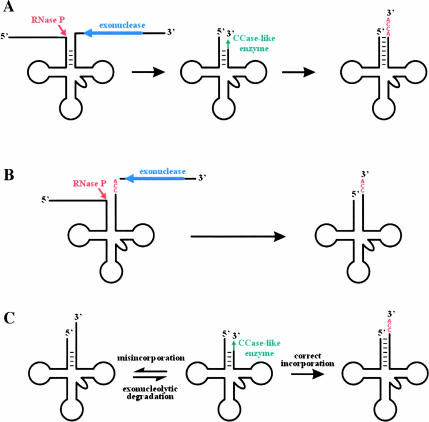

FIGURE 2.

Processing, editing, and repair of tRNAs. (A) Mitochondrial 3′ tRNA editing in S. ecuadoriensis. Exonucleolytic degradation (blue) of the 3′ trailer and any mismatched nucleotides in the 3′ region of the acceptor stem. During this exonucleolytic process, RNase P (red) processes the 5′ region of the molecule. The degraded 3′ region of the acceptor stem is repaired by a CCase-like enzyme (green). Finally, the tRNA is aminoacylated, protecting it from further degradation and allowing it to function in translation. (B) Processing of tRNAs in E. coli. Exonucleases (blue) begin trimming the 3′ trailer region. When the 3′ trailer is sufficiently short, RNase P (red) cleaves off the 5′ leader sequence. Exonucleolytic degradation of the 3′ trailer continues, yielding a 3′ region of the acceptor stem, complete with genome-encoded CCA (Li and Deutscher 1996; Schürer et al. 2001). (C) Editing and repair in metazoan mitochondria (dynamic model for tRNA repair). Mismatched acceptor stems are susceptible to 3′ exonucleolytic degradation, which is followed by random incorporation of nucleotides, likely catalyzed by a CCase-like enzyme. If the nucleotides incorporated are able to form orthodox base pairs with the 5′ portion of the acceptor stem, the structure is aminoacylated, and protected from further degradation. If the nucleotides incorporated cannot form Watson-Crick base pairs, no aminoacylation occurs, and the 3′ region is degraded again, then resynthesized. This dynamic process continues until orthodox base pairs form, and the structure is protected by aminoacylation (Reichert and Mörl 2000).

This model has implications for mitochondrial tRNA 3′ processing in jakobids. The presence of a 3′ exonuclease would be reminiscent of tRNA 3′ processing in bacteria (Fig. 2B ▶). Studies of 3′ tRNA processing have primarily been carried out in E. coli, in which processing begins with an endonucleolytic cleavage of the primary tRNA transcript downstream of the region of the tRNA. The transcript is then trimmed by exonucleases, most notably RNase PH and RNase T. During the course of this trimming process, the 5′ extremity is cleaved by RNase P. In the case of E. coli, the 3′-terminal CCA is encoded in all tRNA genes, and the enzyme CCase serves the purpose of repairing the CCA if the exonucleolytic trimming reaction proceeds into the tRNA region of the transcript. Thus, tRNA 3′ processing is a competition between exonucleases and CCase, a contest that ends when the tRNA is protected from degradation with the addition of an amino acid (Li and Deutscher 1996).

This model is in contrast to the tRNA processing pathways of most organelles, which are thought to resemble nuclear tRNA processing pathways to a greater extent than those of their bacterial ancestors. For example, in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, 3′ end maturation results from a single endonucleolytic cleavage (Chen and Martin 1988); in the nucleus, the 3′ trailer is also removed by an endonuclease in vivo (Yoo and Wolin 1997). Similarly, in plants, mature 3′ ends of nuclear, mitochondrial, and chloroplast tRNAs are generated by a single endonucleolytic cleavage catalyzed by RNase Z (Kunzmann et al. 1998; Mayer et al. 2000; Schiffer et al. 2002).

In metazoans, mitochondrial size constraints result in tRNA genes that are generally separated from downstream RNA or protein-coding genes by very few nucleotides; in some cases, tRNA genes even overlap. Consequently, most tRNAs seem to be processed by a single endonucleolytic cleavage that recognizes the upstream tRNA (Rossmanith et al. 1995; Reichert et al. 1998). It has been proposed that an exonuclease that can act on the 3′ end of tRNAs is present in animal mitochondria, as they have a repair activity that is able to regenerate the 3′ extremities of tRNAs. The dynamic model of tRNA repair (Fig. 2C ▶; Reichert and Mörl 2000), which explains the nature of this process, suggests that this repair process is template independent, beginning with random nucleotide insertion by a CCase-related enzyme. If the incorrect nucleotides are incorporated, the acceptor stem is unable to form orthodox base pairs, is not recognized by the aminoacyl tRNA synthetase, and is susceptible to exonucleolytic degradation. Once the correct nucleotides have been inserted, the acceptor stem base-pairing is permitted, and the tRNA is aminoacylated, protecting it from further degradation. Schürer et al. (2001) suggested that such a model might explain 3′ tRNA repair and editing in all metazoan mitochondria, including L. forficatus. However, we believe that the original hypothesis of Lavrov et al. (2000), by which the resynthesis of the 3′ region of the acceptor stem is template directed, is more likely. In this case, all four nucleotides are used to edit five positions (including the discriminator) in all 22 tRNAs, which would make random nucleotide incorporation extremely inefficient, if not impossible. Template-independent resynthesis of the degraded region of the acceptor stem would seem similarly inefficient in S. ecuadoriensis due to the 256 possible nucleotide replacements. However, it is impossible to rule out the possibility of a more nucleotide-specific incorporation mechanism that prefers C and A residues: in the two edited tRNAs in S. ecuadoriensis, all inserted nucleotides at the six completely edited positions are either C or A.

Another possibility is that 3′ tRNA editing in S. ecuadoriensis is truly template dependent, as Lavrov et al. (2000) suggested was the case for L. forficatus. Template-directed editing of the 3′ end of the acceptor stem would require a 5′-to-3′ RdRp. Such a protein is encoded by the genomes of many RNA viruses, as well as by the mitochondrial genome of Arabidopsis thaliana and by an RNA element found in the mitochondria of the fungus Ophiostoma novo-ulmi (Hong et al. 1998). An RdRp, possibly laterally transferred from a virus, could be responsible for editing in S. ecuadoriensis. In this case, the discriminator position might be added in a template-independent fashion by poly(A)polymerase. However, we believe that the suggestion that an adapted CCase carries out the resynthesis of the 3′ portion of the acceptor stem is more likely, given the strong bias toward the insertion of C and A residues during editing.

S. ecuadoriensis versus L. forficatus: An analogous mechanism for mitochondrial 3′ tRNA editing?

Editing mechanisms affecting the 3′ region of the acceptor stem of mitochondrial tRNAs have previously been identified in animals. Although the mitochondrial 3′ tRNA editing mechanisms of many metazoans use only A, or A and C residues to repair acceptor stem mismatches (Yokobori and Pääbo 1995a,b 1997; Tomita et al. 1996), the editing system of S. ecuadoriensis particularly resembles that of L. forficatus, in which all four nucleotides are used to replace mismatched bases of the 3′ end of the acceptor stem, including the discriminator position (Lavrov et al. 2000).

However, despite the apparent similarity between the 3′ tRNA editing systems of S. ecuadoriensis and L. forficatus, the phylogenetic relationship between these two species is so distant that this similarity is clearly an example of convergent evolution. If 3′ tRNA editing were present in the common ancestor of the metazoa and the jakobids, we would expect to find evidence in the form of apparent mismatches in mitochondrial tRNA acceptor stems in virtually all eukaryotic lineages. However, there is no evidence that 3′ tRNA editing was present even in the common ancestor of the jakobids; in R. americana, a close examination of predicted tRNAs reveals no significant mismatches.

In addition, given that only two tRNAs appear to be modified posttranscriptionally in S. ecuadoriensis, it is likely that this editing system evolved relatively recently, as the presence of such a system would virtually eliminate selection pressure on the edited region of the molecule, allowing the sequence to diverge freely. In contrast, the editing system in L. forficatus is likely a much older adaptation, because editing has been demonstrated experimentally or inferred based on sequence data for all 22 tRNAs encoded in the mtDNA (Lavrov et al. 2000).

Finally, it is significant that no partial editing was found in L. forficatus (Lavrov et al. 2000). This observation suggests that either editing is considerably more efficient in L. forficatus, or that the mismatched region is removed by an endonucleolytic cleavage. The latter possibility is consistent with the results of Rossmanith et al. (1995), who demonstrated that, in human mitochondria, maturation of the 3′ region of tRNAs is the result of an endonucleolytic cleavage. In addition, the strong bias for incorporation of C and A residues in S. ecuadoriensis was not observed in L. forficatus, in which only 62% of incorporated nucleotides were either C or A (including the discriminator position, which was always an A). Although these observations are by no means conclusive, they suggest that tRNA editing in L. forficatus and S. ecuadoriensis is mechanistically distinct.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture, cloning, sequencing, and annotation of mtDNA

DNA sequences of S. ecuadoriensis were determined under the auspices of the Organelle Genome Megasequencing Project. Details of growth conditions and mtDNA isolation and cloning will be presented elsewhere in conjunction with a more detailed description of the complete sequence (B.F. Lang, unpubl.). DNA sequencing, data entry, and sequence analysis were performed as described (Burger et al. 1995). tRNA genes were identified by using tRNAscan-SE (Lowe and Eddy 1997).

RNA purification

Cells were cultured in WCL medium, buffered with 20 mM HEPES, harvested and disrupted with glass beads, and enriched for mitochondria by differential centrifugation. Mitochondria were lysed with SDS and proteinase K and enriched for mitochondrial tRNAs by centrifugation through a glycerol cushion. The upper tRNA-containing fractions were pooled, and protein was eliminated by repeated phenol-chloroform extractions, followed by multiple ethanol precipitations.

Oligonucleotides

The following primer sequences were used for RT-PCR:

RT-PCR, cloning, and sequencing

tRNAs were circularized and cDNAs synthesized following the protocol of Yokobori and Pääbo (1995a), with the following adaptations: The tRNA concentration used for circularization was reduced to 40 μg/mL, and the circularized tRNA concentration used for reverse transcription was reduced to 25 μg/mL. The resulting cDNAs were amplified by PCR. PCR products were incubated with a mixture of T7 DNA polymerase and E. coli DNA polymerase I (Klenow fragment) to generate blunt ends, and the PCR fragment of the appropriate size was recovered after agarose gel electrophoresis. The purified PCR fragment was cloned into the EcoR5 cloning site of the phagemid pFBS (B.F. Lang, unpubl.) and sequenced.

Table t.

| tRNA amplified | Direction | Sequence |

| Alanine | Forward | CATATGCTCTGCCAAATGAGCT |

| Alanine | Reverse | TTTTGCACGCATAGGGTAACCA |

| Cysteine | Forward | CCCATACATTGCCATTATGTTA |

| Cysteine | Reverse | CTGCAAATCCTATAATGGCG |

| Glutamate | Forward | CGATGTCCTAACCACTAGAC GA |

| Glutamate | Reverse | TCATGGCGTAAACACGGGT TCA |

| Histidine | Forward | CACTCTAACCAACTGAGTTA |

| Histidine | Reverse | TTGTGATTCTGGAAGTCACG |

| Serine | Forward | GCGCAATAGACCACTCTGCCA |

| Serine | Reverse | TTTGGAATTCGTGTTAATCTAAT |

Acknowledgments

We thank Tom Nerad (ATCC), who isolated S. ecuadoriensis. We also thank Lise Forget (Université de Montréal) for library construction and DNA sequencing, Zhang Wang (Université de Montréal) and Lise Forget for DNA sequencing, and Dennis Lavrov (Université de Montréal) and Charles Bullerwell (Dalhousie University) for critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR, MSP-14226) and by Genome Quebec/Canada through the supply of laboratory equipment and informatics infrastructure. B.F.L. is Imasco Fellow in the Program of Evolutionary Biology of the Canadian Institute for Advanced Research (CIAR), whom we thank for salary and interaction support.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Article and publication are at http://www.rnajournal.org/cgi/doi/10.1261/rna.5195504.

REFERENCES

- Burger, G., Plante, I., Lonergan, K.M., and Gray, M.W. 1995. The mitochondrial DNA of the amoeboid protozoon, Acanthamoeba castellanii: Complete sequence, gene content and genome organization. J. Mol. Biol. 245: 522–537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.Y. and Martin, N.C. 1988. Biosynthesis of tRNA in yeast mitochondria: An endonuclease is responsible for the 3′-processing of tRNA precursors. J. Biol. Chem. 263: 13677–13682. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gott, J.M. and Emeson, R.B. 2000. Functions and mechanisms of RNA editing. Annu. Rev. Genet. 34: 499–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray, M.W. and Covello, P.S 1993. RNA editing in plant mitochondria and chloroplasts. FASEB J. 7: 64–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong, Y., Cole, T.E., Brasier, C.M., and Buck, K.W. 1998. Evolutionary relationships among putative RNA-dependent RNA polymerases encoded by a mitochondrial virus-like RNA in the Dutch elm disease fungus, Ophiostoma novo-ulmi, by other viruses and virus-like RNAs and by the Arabidopsis mitochondrial genome. Virology 246: 158–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou, Y.M. and Schimmel, P. 1988. A simple structural feature is a major determinant of the identity of a transfer RNA. Nature 333: 140–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob, Y., Seif, E., Paquet, P-O., and Lang, B.F. 2004. Loss of the mRNA-like region in the mitochondrial tmRNAs of jakobids. RNA (this issue). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Keiler, K.C., Shapiro, L., and Williams, K.P. 2000. tmRNAs that encode proteolysis-inducing tags are found in all known bacterial genomes: A two-piece tmRNA functions in Caulobacter. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 97: 7778–7783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunzmann, A., Brennicke, A., and Marchfelder, A. 1998. 5′ end maturation and RNA editing have to precede tRNA 3′ processing in plant mitochondria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 95: 108–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laforest, M.J., Roewer, I., and Lang, B.F. 1997. Mitochondrial tRNAs in the lower fungus Spizellomyces punctatus: tRNA editing and UAG “stop” codons recognized as leucine. Nucleic Acids Res. 25: 626–632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang, B.F., Burger, G., O’Kelly, C.J., Cedergren, R., Golding, G.B., Lemieux, C., Sankoff, D., Turmel, M., and Gray, M.W. 1997. An ancestral mitochondrial DNA resembling a eubacterial genome in miniature. Nature 387: 493–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavrov, D.V., Brown, W.M., and Boore, J.L. 2000. A novel type of RNA editing occurs in the mitochondrial tRNAs of the centipede Lithobius forficatus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 97: 13738–13742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z. and Deutscher, M.P. 1996. Maturation pathways for E. coli tRNA precursors: A random multienzyme process in vivo. Cell 86: 503–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lonergan, K.M. and Gray, M.W. 1993. Editing of transfer RNAs in Acanthamoeba castellanii mitochondria. Science 259: 812–816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe, T.M. and Eddy, S.R. 1997. tRNAscan-SE: A program for improved detection of transfer RNA genes in genomic sequence. Nucleic Acids Res. 25: 955–964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer, M., Schiffer, S., and Marchfelder, A. 2000. tRNA 3′ processing in plants: Nuclear and mitochondrial activities differ. Biochemistry 39: 2096–2105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Kelly, C.J. 1993. The jakobid flagellates: Structural features of Jakoba, Reclinomonas and Histiona and implications for the early diversification of eukaryotes. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 40: 627–636. [Google Scholar]

- Powell, L.M., Wallis, S.C., Pease, R.J., Edwards, Y.H., Knott, T.J., and Scott, J. 1987. A novel form of tissue-specific RNA processing produces apolipoprotein-B48 in intestine. Cell 50: 831–840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preiss, J., Dieckmann, M., and Berg, P. 1961. The enzymic synthesis of amino acyl derivatives of ribonucleic acid. IV: The formation of the 3′ hydroxyl terminal trinucleotide sequence of amino acid-acceptor ribonucleic acid. J. Biol. Chem. 236: 1748–1757. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price, D.H. and Gray, M.W. 1999. Confirmation of predicted edits and demonstration of unpredicted edits in Acanthamoeba castellanii mitochondrial tRNAs. Curr. Genet. 35: 23–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichert, A.S. and Mörl, M. 2000. Repair of tRNAs in metazoan mitochondria. Nucleic Acids Res. 28: 2043–2048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichert, A., Rothbauer, U., and Mörl, M. 1998. Processing and editing of overlapping tRNAs in human mitochondria. J. Biol. Chem. 273: 31977–31984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossmanith, W., Tullo, A., Potuschak, T., Karwan, R., and Sbisà, E. 1995. Human mitochondrial tRNA processing. J. Biol. Chem. 270: 12885–12891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiffer, S., Rösch, S., and Marchfelder, A. 2002. Assigning a function to a conserved group of proteins: The tRNA 3′-processing enzymes. EMBO J. 21: 2769–2777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schürer, H., Schiffer, S., Marchfelder, A., and Mörl, M. 2001. This is the end: Processing, editing and repair at the tRNA 3′-terminus. Biol. Chem. 382: 1147–1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomita, K., Ueda, T., and Watanabe, K. 1996. RNA editing in the acceptor stem of squid mitochondrial tRNA(Tyr). Nucleic Acids Res. 24: 4987–4991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokobori, S. and Pääbo, S. 1995a. Transfer RNA editing in land snail mitochondria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 92: 10432–10435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ———. 1995b. tRNA editing in metazoans. Nature 377: 490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ———. 1997. Polyadenylation creates the discriminator nucleotide of chicken mitochondrial tRNA(Tyr). J. Mol. Biol. 265: 95–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo, C.J. and Wolin, S.L. 1997. The yeast La protein is required for the 3′ endonucleolytic cleavage that matures tRNA precursors. Cell 89: 393–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, H., Fu, T.B., Lazinski, D., and Taylor, J. 1992. Editing on the genomic RNA of human hepatitis delta virus. J. Virol. 66: 4693–4697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]