Abstract

The initial aim of this study was to combine attributes of adeno-associated virus (AAV) and adenovirus (Ad) gene therapy vectors to generate an Ad-AAV hybrid vector allowing efficient site-specific integration with Ad vectors. In executing our experimental strategy, we found that, in addition to the known incompatibility of Rep expression and Ad growth, an equally large obstacle was presented by the inefficiency of the integration event when using traditional recombinant AAV (rAAV) vectors. This study has addressed both of these problems. We have shown that a first-generation Ad can be generated that expresses Rep proteins at levels consistent with those found in wild-type AAV (wtAAV) infections and that Rep-mediated AAV persistence can occur in the presence of first-generation Ad vectors. Our finding that traditional rAAV plasmid vectors lack integration potency compared to wtAAV plasmid constructs (10- to 100-fold differences) was unexpected but led to the discovery of a previously unidentified AAV integration enhancer sequence element which functions in cis to an AAV inverted terminal repeat-flanked target gene. rAAV constructs containing left-end AAV sequence, including the p5-rep promoter sequence, integrate efficiently in a site-specific manner. The identification of this novel AAV integration enhancer element is consistent with previous studies, which have indicated that a high frequency of wtAAV recombinant junction formation occurs in the vicinity of the p5 promoter, and recent studies have demonstrated a role for this region in AAV DNA replication. Understanding the contribution of this element to the mechanism of AAV integration will be critical to the use of AAV vectors for targeted gene transfer applications.

Adeno-associated virus (AAV) is a human parvovirus with a single-stranded DNA genome of 4.7 kb (4). It contains two open reading frames (ORFs), rep and cap, which are flanked by two inverted terminal repeats (ITRs) (14, 32). The ITRs are 160 nucleotides including the D element and are considered to be the only cis elements required for replication and site-specific integration of the AAV genome. In addition to the ITR elements, the rep gene is necessary in trans to target the integration event to the AAVS1 site (2, 5, 16, 25, 30, 34). The rep ORF encodes four nonstructural proteins, Rep 40, Rep 52, Rep 68, and Rep 78, which are involved in the replication of the AAV genome (33, 35). Rep 68 and Rep 78 are gene products of alternatively spliced mRNA transcribed from the AAV p5 promoter. These larger Rep proteins have DNA binding, site-specific, and strand-specific endonuclease activities as well as ATPase and DNA-DNA and DNA-RNA helicase functions (12, 13, 41, 45). Transcription from the p19 promoter generates Rep 52 and Rep 40; Rep 52 is known to have helicase and ATPase activities but no DNA binding or endonuclease activity (31). Rep 68 and Rep 78 down-regulate the p5 and p19 promoters (3), and this stringent control of Rep expression helps to minimize cell death caused by the cytotoxicity of the Rep proteins (4).

AAV is the only known virus that site specifically integrates into the human genome, and this targeted integration of the AAV genome occurs at the AAVS1 site on chromosome 19q13.3-qter (10, 15, 29). Although the precise molecular mechanisms of AAV site-specific integration are not well understood, it appears that Rep 68 or Rep 78 is critical. The Rep protein functions by binding to the Rep binding elements (RBEs) situated in both AAV ITRs and at the AAVS1 site (6, 10, 40). The endonuclease activity of the two larger Rep proteins allows them to nick at the terminal resolution site, which is positioned 8 or 11 bp away from the RBEs in AAV and AAVS1, respectively. There then follows an interaction between Rep molecules that are bound to the AAV genome and those that are bound to the AAVS1 site, and a nonhomologous recombination event occurs, resulting in integration of the AAV genome (19, 20, 38, 42). It has been shown previously that head-to-tail concatemers of the wild-type AAV (wtAAV) genome are able to site specifically integrate in this manner (11). Preferred AAV recombination junction sites have been localized to both left and right AAV ITR elements as well as the p5-rep promoter region of the AAV genome (11). The site-specific integration of AAV combined with its low immunogenicity and lack of any known pathology has made recombinant AAV (rAAV) a popular gene therapy model system.

One major disadvantage of using AAV as a gene therapy vector is its relatively low transduction efficiency. In addition, rAAV vectors can package only foreign DNA elements less than 5 kb in length. Our initial aim was, therefore, to combine the attributes of both the AAV and adenovirus (Ad) gene therapy vectors and develop an Ad-AAV hybrid virus system. In theory, an Ad-AAV hybrid vector could utilize Ad packaging elements for efficient transduction of host cells and would also be easier than AAV to grow to a high titer. In addition, it would contain a transgene flanked by AAV ITRs and also AAV-rep to mediate site-specific integration of the transgene.

The first step in developing the Ad-AAV chimeric vector system was to generate a replication-defective, E1− Ad that expresses AAV Rep 68 and Rep 78. The ability of the Ad-Rep viruses to mediate site-specific integration was tested by assessing the targeted integration efficiency of an rAAV plasmid, pTRUF2 (46), in the presence or absence of Ad-Rep virus. Despite the fact that Ad-Rep virus appeared to be essential for long-term maintenance of the transgene, in the absence of selection the efficiency of persistence was very low. These results are consistent with a previous study characterizing a different version of the Ad-AAV chimera (26). Since the efficiency of site-specific integration of rAAV has not often been directly compared to that of wtAAV, we have made a direct comparison of an rAAV plasmid vector (pTRUF2) with a wtAAV plasmid vector (pSub201) (27). Our studies indicate that inefficient integration of rAAV vectors is attributable to the requirement for a cis efficiency element, which can increase integration efficiency by greater than 20-fold.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

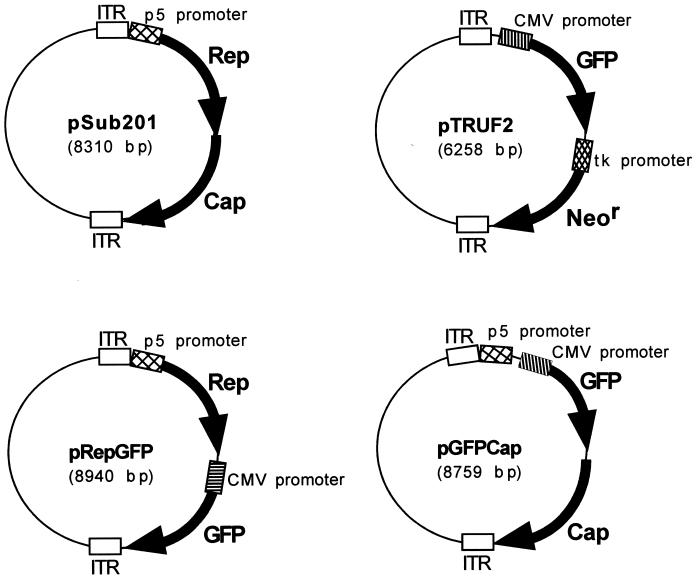

Plasmid constructs.

Plasmid constructs pTRUF2 (46), pSub201 (27), pAAV/Ad (28) and p2ITRLacZ (34) are well-established AAV constructs. Plasmids pRepGFP and pGFPCap were both constructed from pAV2 (17). For pRepGFP, pAV2 was digested with ScaI and XhoI. The following oligonucleotides were annealed and ligated into the pAV2 construct: TCGAGGACACTCTCTCTGAAGGAATAAGACTAGTTA and TAACTAGTCTTATTCCTTCAGAGAGAGTGTCC. The gfp gene was excised from pTRUF2 by an EcoRI digest which was blunt ended and cloned into the SnaBI site of the pAV2 construct, generating pRepGFP (see Fig. 6). For pGFPCap, rep sequence was removed from pAV2 via a SacII digest. The green fluorescent protein (GFP) sequence was then excised from pTRUF2 by EcoRI and XhoI digestion and cloned into the SacII site of the pAV2 construct in the same direction as cap, to produce pGFPCap (see Fig. 6).

FIG. 6.

Schematic representation of the AAV plasmid constructs. pSub201 (27) and pTRUF2 (46) are well-established AAV constructs. The partial rAAV plasmid vectors pRepGFP and pGFPCap were constructed from pAV2 (17) (see Materials and Methods for details). tk, thymidine kinase.

Ad-AAV virus constructs.

Specific details of the construction of Ad-Rep virus constructs used in this study, Ad-Rep210 and Ad-Rep78, can be obtained upon request. Briefly, an Ad left-end shuttle plasmid, pAd(BS), deleted in Ad sequence from nucleotides 351 to 2950, received a T7 promoter-driven wt Rep cassette from bacterial expression plasmid pET-Rep210 or a T7 mutant Rep cassette from pET-Rep78. The Rep 78 cassette contains a mutation at the p19 translation start site (ATG to CCC) and therefore expresses only Rep 68 and Rep 78 and not the smaller Rep proteins 40 and 52. Both cassettes were inserted such that transcription occurred away from the Ad viral packaging element. Immediately downstream of the Rep cassette, a cytomegalovirus (CMV)-GFP expression cassette was inserted with GFP transcribed so as to be in the same direction as the T7-Rep cassettes. Standard overlap recombination methods (9) were used to produce virus. Briefly, human embryonic kidney 293 cells were cotransfected with the large fragment of XbaI-digested dlAd5NCAT and pAd-Rep. Successful recombinants were initially identified by the presence of GFP, and twice-plaque-purified recombinants were further characterized by DNA restriction site and sequence analysis. Large-scale virus was generated as previously described by two rounds of CsCl purification (9). Virus particle concentration was determined by measurement of optical density at 260 nm, and standard plaque assays were used to determine particle/PFU ratios (routinely in the range of 50 to 100 particles/PFU).

Western blot analysis.

AAV Rep 78 protein expression from the Ad-Rep viruses was visualized by Western blot analysis. HeLa cells were infected with Ad-Rep virus, and 48-h-postinfection nuclear extracts were isolated by the rapid preparation method of Andrews and Faller (1), which is a modified version of the standard Dignam protocol (7). Extracts were immunoprecipitated overnight with anti-AAV-Rep monoclonal antibody, clone 226.7 (American Research Products), and agarose-conjugated mouse immunoglobulin G (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Immunoprecipitated proteins were then separated on sodium dodecyl sulfate-8% polyacrylamide gel gels and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane (Millipore). AAV Rep 78 protein was detected with a monoclonal mouse antibody supernatant, clone 303.9 (ARP), and an enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) Western blotting detection kit (Amersham Pharmacia), according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Southern blot analysis.

Whole-cell DNA was isolated from HeLa cell lines by a standard salting-out protocol (22). EcoRI was used to digest 7.5 μg of DNA from each clone, and digested DNA was separated on 1% agarose gels. After DNA fragments were transferred to nylon membranes, hybridization was carried out with 32P-labeled probes at a concentration of 3 million cpm/ml of Sigma prehybridization solution, according to the manufacturer's instructions. The following DNA fragments were generated for DNA probes: the 800-bp Rep PCR fragment was generated from oligonucleotides GATCGAAGCTTCCGCGTCTGACGTCGATGG and GGACCAGGCCTCATACATCTCCTTCAATGC, the AAVS1 1-kb PCR product was obtained with oligonucleotides GAACTCTGCCCTCTAACGCTGC and CACCAGATAAGGAATCTGCC (15, 36), SalI digest of pTRUF2 produced the 1-kb Neor probe, p2ITRLacZ was digested with ApoI and BclI to obtain an 850-bp β-galactosidase fragment, NotI digest of pTRUF2 generated a 700-bp GFP fragment, and ApaI digest of pSub201 produced an 800-bp Cap probe. DNA probes were 32P labeled with the Rediprime kit (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Bands were visualized by autoradiography.

Cell culture.

HeLa cell lines were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium containing 5% calf serum and 5% fetal calf serum. Cell lines grown in neomycin selection medium were supplemented with 0.5 mg of Geneticin (GibcoBRL)/ml.

Ad-Rep-mediated integration assay.

HeLa cells were infected with Ad-Rep virus or control Ad5-GFP virus and 24 h later transfected with the rAAV plasmid pTRUF2 or a control plasmid containing a gfp gene. One week postinfection colonies were picked and grown for 5 weeks in the absence of antibiotic or in Geneticin-supplemented medium. GFP persistence was assessed 5 weeks postinfection. Total cellular DNA was harvested and digested with EcoRI, and bands were separated on 1% agarose gels. DNA was transferred to nylon membranes (NEN) and hybridized to 32P-labeled AAVS1 or Neor probes (by the Southern blot protocol described above).

Plasmid-mediated integration assay.

HeLa cells were electroporated with wtAAV and/or rAAV plasmid, and GFP-positive cells were isolated by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) 48 h posttransfection (with a Beckman-Coulter Altra cell sorter). When necessary, cells were immediately infected with adenovirus (Ad5CAT or Ad5βgal) at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 10. Cells were plated at one cell per well into 96-well plates, and clonal cell lines were grown for 6 weeks. Whole-cell DNA was harvested, EcoRI digested, and separated on 1% agarose gels. The DNA was transferred to nylon membranes and hybridized to 32P-labeled AAVS1, Rep, Neor, β-galactosidase, GFP, or Cap probes (by the Southern blot protocol described above).

RESULTS

Generation of Ads expressing AAV Rep.

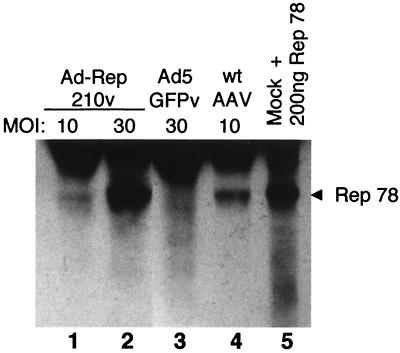

Two AAV components, the AAV rep gene in trans and the AAV ITR elements in cis, have been identified elsewhere as minimally required for site-specific integration of wtAAV (8, 18, 30, 42). Since AAV Rep proteins are cytotoxic (4) and inhibit Ad replication (39), a major challenge to incorporating AAV integration machinery into Ad vectors is to engineer a virus that generates low levels of Rep but allows normal growth of Ad (26). Low-level Rep expression was obtained by using a T7 phage promoter to mediate rep transcription. Two plasmids carrying such a transcription unit were constructed: pAd-Rep210 contains wt rep and therefore expresses all four Rep proteins (Rep 40, Rep 52, Rep 68, and Rep 78), and pAd-Rep78 is mutated at the p19 translation start site (ATG to CCC) and therefore expresses only the two larger Rep proteins, Rep 68 and Rep 78, which are sufficient to obtain AAV site-specific integration (16, 34). When tested for Rep expression in transient assays, each construct indicated low levels of Rep protein expression even in the absence of T7 RNA polymerase (data not shown). In spite of the low level of Rep expression, each construct was successfully converted into a first-generation Ad vector by overlap recombination; the recombinant viruses are Ad-Rep210 and Ad-Rep78 (generically referred to as Ad-Rep). When HeLa cells were infected with either 1,000 or 3,000 particles (MOI of 10 or 30) of Ad-Rep virus (Ad-Rep210 shown in Fig. 1) per cell and total nuclear proteins were analyzed by Western blot analysis for Rep expression, an appropriately sized rep gene product was identified with Rep-specific antisera. In comparison, HeLa cells infected with wtAAV at an MOI of 10 yielded slightly more Rep than the 1,000 particles of Ad-Rep per cell but less than 3,000 particles/cell (Fig. 1, compare lanes 1, 2, and 4). These assays are not interpreted as being quantitative with respect to total Rep protein but rather indicate the relative amount of an appropriately sized rep gene product expressed from the Ad-Rep viruses. Therefore, the Ad-Rep viruses were expressing what we considered a reasonable and potentially functional level of the rep gene products necessary to mediate site-specific integration.

FIG. 1.

Expression of Rep from Ad-Rep210 virus. Protein was extracted from HeLa cells infected with Ad-Rep210 virus at an MOI of 10 or 30 (lanes 1 and 2, respectively), with Ad5-GFP (lane 3), and with wtAAV at an MOI of 10 (lane 4); also shown is mock extract plus 200 ng of purified bacterially expressed Rep 78 (lane 5). Extracts were separated on a sodium dodecyl sulfate-8% polyacrylamide gel and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane as described in Materials and Methods. AAV Rep 78 protein was detected with a monoclonal mouse antibody, clone 303.9 (ARP), and ECL (Amersham Pharmacia).

Ad-Rep expression enhances rAAV persistence.

As a basic functional test for the ability of the Ad-Rep viruses to mediate site-specific integration, we performed an integration assay using an rAAV plasmid, pTRUF2 (46), which contains both the GFP gene and the neomycin resistance (Neor) gene flanked by AAV ITRs. HeLa cells were infected with Ad5-Rep virus or control Ad5-GFP virus and 24 h later electroporated with the GFP-containing rAAV plasmid pTRUF2 or control plasmid pAd5GFP. Under these conditions ∼10 to 20% of surviving cells are transfected by plasmid DNA, and after 1 week we have found that Ad5-GFP gene persistence is at background levels (data not shown). Previous work on AAV integration with hybrid vector systems has shown development of cell lines by using antibiotic selection (24, 26). Since the use of antibiotic selection would not be feasible in vivo, we wanted to study the effect that an antibiotic may have on the persistence of a transgene. We therefore divided the transfected and infected cells into two portions: the first group was not exposed to antibiotic selection, and the second was grown in the presence of neomycin.

At 1 week postinfection, GFP-positive colonies were picked and clonal cell lines were established, assuming that GFP expression was plasmid mediated. At 5 weeks postinfection, colonies maintaining persistent GFP expression were assessed (Table 1). GFP fluorescence of colonies was relatively low on a per-cell basis, and within each colony there was heterogeneity of fluorescence intensity; therefore, we did not attempt to make qualitative comparisons of GFP expression between colonies. In the presence of neomycin selection, Rep was not essential for the low-level persistence of pTRUF2; 0.07% of clones maintained GFP in the absence of Rep (Table 1). In cells infected by the Ad-Rep78 virus and exposed to neomycin, the addition of Rep expression resulted in an increase in the overall number of GFP-positive colonies to between 0.10 and 0.12%. In the absence of antibiotic selection, persistently GFP-expressing colonies were found only under the experimental conditions that included Ad-Rep viruses. Of more than 104 cells that were originally transduced by the pTRUF2 plasmid, between 0.03 and 0.06% of cell lines expressed GFP 5 weeks posttransfection. These results indicate that neomycin may encourage the persistence of pTRUF2 plasmid through selective pressure but also that, in the absence of drug selection, successful GFP persistence can be achieved in an Ad-Rep-dependent manner.

TABLE 1.

Persistence of rAAV-GFP in HeLa cellsa

| Virus | Plasmid | % of clones expressing GFP 5 wk postinfection or -transfection

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| No selection (1.2 × 104 cells) | Neomycin selection (8.4 × 104 cells) | ||

| Ad5-GFPv | pAd5GFP | 0 | 0 |

| Ad5-GFPv | pTRUF2 | 0 | 0.07 |

| Ad-Rep78v | pAd5GFP | 0 | 0 |

| Ad-Rep78v | pTRUF2 | 0.06 | 0.12 |

| Ad-Rep210v | pAd5GFP | 0 | 0 |

| Ad-Rep210v | pTRUF2 | 0.03 | 0.1 |

Cells were infected with Ad-Rep virus or control Ad5-GFP virus and 24 h later transfected with the GFP-containing rAAV plasmid pTRUF2 or control pAd5GFP. One week postinfection colonies were picked and grown for 5 weeks. GFP persistence was assessed at 5 weeks postinfection. Numbers show percentages of 104 cells that were both Ad infected and transfected with pTRUF2 or pAd5GFP.

In the presence of Ad-Rep, rAAV persists in an episomal form.

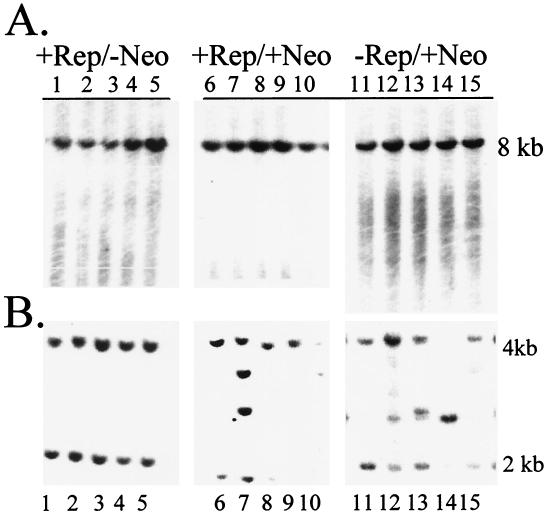

Having established that in the absence of drug selection the Ad-Rep virus was, at low efficiency, able to contribute to transgene persistence for up to 5 weeks posttransfection, we sought to discover how the pTRUF2 DNA was being maintained. Site-specific integration by AAV is characterized by the occurrence of a nonhomologous recombination event, which occurs at chromosome 19q13.3-qter of the human genome (referred to as the S1 site) (15). The S1 site is contained within an 8-kb EcoRI genomic fragment, and AAV site-specific integration causes genomic rearrangements within this site. When whole-cell DNA was harvested from clonal isolates, digested with EcoRI, and characterized by Southern blot analysis for disruptions of the S1 genomic fragment, none of the clonal isolates indicated that an S1 disruption had occurred (Fig. 2A). Under the conditions used for these studies, either in the presence or in the absence of antibiotic selection, there was no evidence for site-specific integration mediated by the Ad-Rep viruses.

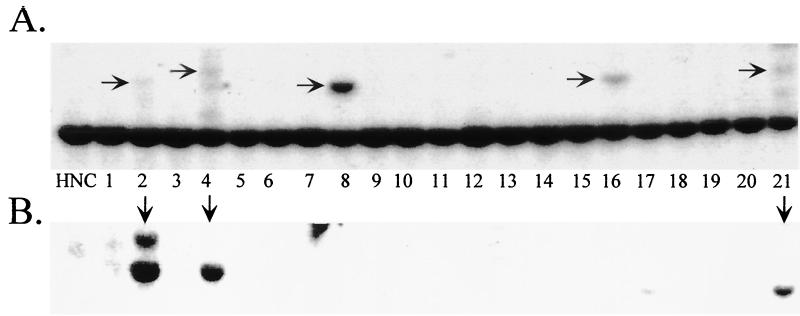

FIG. 2.

Southern blot characterization of rAAV(Neo) and AAVS1 DNA in clonal cell lines. HeLa cells were infected with Ad-Rep virus (lanes 1 to 10) or control Ad5-GFP virus (lanes 11 to 15) and 24 h later transfected with the rAAV plasmid pTRUF2. One week postinfection GFP+ colonies were picked and grown for 5 weeks, in the absence of antibiotic selection (lanes 1 to 5) or with neomycin selection (lanes 6 to 15). Total cellular DNA was harvested and digested with EcoRI, and bands were separated on 1% agarose gels. DNA was transferred to a nylon membrane and hybridized to 32P-labeled AAVS1 (A) or a Neor (B) probe.

Since all of these cell lines were selected based on GFP expression, we performed Southern blot analysis to detect either the GFP or the Neor gene sequences. In the absence of antibiotic selection, in all samples examined, the Neor probe bound to a 2- and a 4-kb band (representative sample digests are shown in Fig. 2B). These bands are equivalent in size to bands of EcoRI-digested pTRUF2. Based on the lack of discernible S1 disruption and the dominant fragment pattern illustrated when probing for pTRUF2 gene fragments, we concluded that the pTRUF2 DNA was maintained in an atypical extrachromosomal form up to 5 weeks posttransfection, in a Rep-facilitated manner. When the clonal cell lines that were generated under antibiotic selection were characterized by Neor Southern blot analysis, in addition to the 2- and 4-kb bands associated with pTRUF2, randomly sized clonal specific bands were identified, indicating that the transgenes were randomly integrated into the HeLa cell genome.

Efficient integration of ds wtAAV plasmid pSub201.

Results shown in Table 1 indicate that, in the absence of neomycin, the persistence of pTRUF2 in the presence of a Rep-expressing Ad was less than 0.1%. Accordingly, we wanted to discover why the transgene persistence was so low and why there appeared to be no site-specific integration in the absence of antibiotic selection. We considered three possibilities: (i) integration of AAV when it enters the cell in a double-stranded (ds) form in such a plasmid (or Ad) is inherently low, (ii) the presence of a first-generation Ad and/or specific Ad proteins inhibit integration of AAV, and (iii) rAAV integrates at a much lower efficiency than does wtAAV.

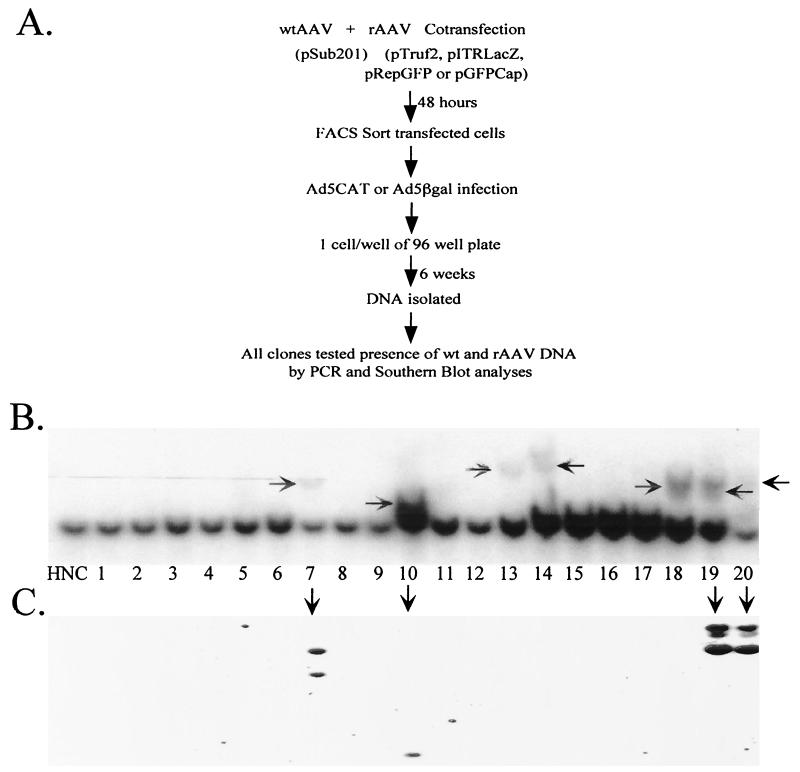

To address these questions, we set up a simple assay for integration efficiency mediated by various AAV plasmid constructs (Fig. 3A). HeLa cells were cotransfected with a ds wtAAV plasmid (pSub201 [27]) and a GFP-expressing plasmid. GFP-positive cells were FACS sorted 48 h posttransfection, and cells were plated onto 96-well plates with one cell per well. After the initial sorting of GFP-positive cells, no further sorting based on transgene expression or antibiotic selection was employed. Clonal cell lines were maintained for 6 weeks, and at the end of this time period, random clonal isolates were selected. Whole-cell DNA was harvested and screened for AAV DNA by PCR (data not shown) and Southern blot analyses; AAVS1 disruptions and site-specific integration events were assessed by Southern blot analyses only (Fig. 3).

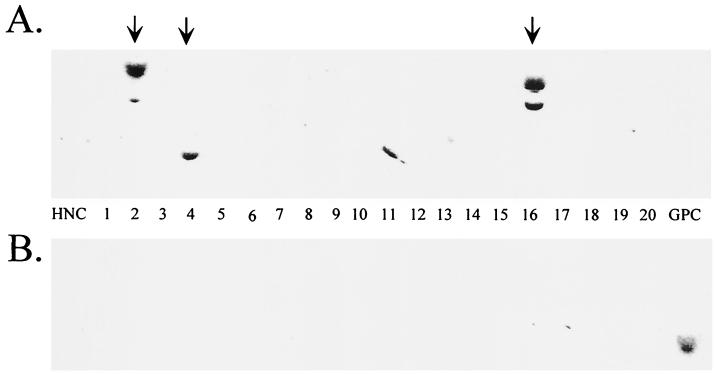

FIG. 3.

Southern blot analysis of pSub201-transfected HeLa cell lines. HeLa cells were transfected with pSub201 and GFP-expressing plasmid, and then 48 h posttransfection cells were FACS sorted and clonal cell lines were grown for 6 weeks (A). Whole-cell DNA was harvested, EcoRI digested, and characterized by Southern blot analysis by probing with 32P-labeled AAVS1 (B) or Rep (C) probes. HNC, negative control HeLa cell DNA. Horizontal arrows indicate disruptions of the chromosome 19 AAVS1 8-kb EcoRI genomic fragment (B), and vertical arrows indicate rep-containing clones (C).

The Southern blots in Fig. 3B and C show a sample of over 250 clonal cell lines that had originally been transfected with pSub201. By screening the cell lines for rep DNA, we found that ds wtAAV persisted in 12% of the clones, 6 weeks posttransfection (Table 2). By probing the blots with AAVS1 DNA, we found that 90% of clones containing AAV DNA also had disruptions at the AAVS1 site and that in each of these cell lines AAVS1 bands comigrated with AAV bands, suggesting that the wtAAV had been site specifically integrated. Interestingly, approximately twice as many cell lines had S1 disruptions as contained the rep sequence, indicating that Rep-mediated AAVS1 disruptions occur in the absence of persistent AAV DNA integration (2, 5, 34). In summary, ds wtAAV (pSub201) site specifically integrated into the AAVS1 site in 12% of more than 250 clonal cell lines tested, showing at least 100-fold-higher persistence than that with the Ad-Rep hybrid vector system.

TABLE 2.

Site-specific integration efficiency of wtAAV and rAAV plasmid vectorsa

| Plasmid | Total no. of clones screened | No. of clones with transgene | Integration efficiency (%) | % of transgene- containing clones with AAVS1 disruption |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| pSub201 | 269 | 33 | 12 | 90 |

| pSub201 + Ad | 114 | 10 | 9 | 90 |

| pTRUF2 | 95 | 0 | <1 | |

| p2ITRLacZ | 48 | 0 | <2 | |

| pRepGFP | 166 | 22 | 13 | <100 |

| pGFPCap | 194 | 10 | 5 | 100 |

HeLa cells were transfected with plasmid vectors, and clonal cell lines were grown for 6 weeks. Whole-cell DNA was harvested, digested with EcoRI, and separated on 1% agarose gels. DNA was transferred to nylon membranes and hybridized to 32P-labeled transgene probes.

Persistent maintenance of integrated wtAAV plasmid vector in the presence of Ad E1− virus.

Having determined that ds pSub201 could in fact integrate efficiently, we next addressed the question of integration interference by first-generation E1− Ad. HeLa cells were cotransfected with pSub201 and FACS sorted, as described above. The cells were then infected with Ad5CAT or Ad5βgal (MOI of 10), and clonal cell lines were grown for 6 weeks and then screened for rep DNA by PCR (data not shown) and Southern blot analysis. AAVS1 disruptions were also assessed by Southern blotting. Figure 4 presents Southern blot analyses of clones that had been transfected with pSub201 and infected with Ad5CAT, a first-generation E1− Ad. In the presence of Ad5CAT or Ad5βgal, the rep gene persisted in 9% of cell lines, similar to the frequency of wtAAV persistence in the absence of Ad (12%) (Table 2). The same cell lines contained disruptions in the S1 site, suggesting that rep had been site specifically integrated. Therefore, these results indicate that E1− Ad, when superinfecting cells 48 h posttransfection, does not inhibit integration or the persistence of ds wtAAV (pSub201). Complementing the lack of effect by recombinant Ad on AAV integration, plasmids expressing either the E2 or E4 Ad transcription unit were examined separately in a pSub201 cotransfection assay. Integration efficiencies for pSub201 under both conditions were 8% (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

Recombinant Ad-infected HeLa cells transfected with pSub201 efficiently integrate AAV. HeLa cells were transfected with pSub201 and GFP-expressing plasmid, and then 48 h posttransfection cells were FACS sorted and superinfected with Ad5CAT at an MOI of 10 (1,000 particles/cell). GFP+ clonal cell lines were grown for 6 weeks. Whole-cell DNA was harvested, EcoRI digested, and characterized by Southern blot analysis by probing with 32P-labeled AAVS1 (A) or Rep (B) probes. HNC, negative control HeLa cell DNA. Horizontal arrows indicate disruptions of the chromosome 19 AAVS1 8-kb EcoRI genomic fragment (A), and vertical arrows indicate rep-containing clones (B).

rAAV is a compromised substrate DNA for site-specific integration.

Having demonstrated that in our hands ds wtAAV vectors are able to efficiently undergo site-specific integration and that the presence of E1− Ad does not inhibit integration of wtAAV, we were left with the question of a defect in the ability of pTRUF2 to site specifically integrate. This defect in pTRUF2 would have contributed to its inefficient persistence and integration seen in previous experiments with the Ad-Rep viruses. HeLa cells were cotransfected with pTRUF2 and a wtAAV plasmid that does not contain AAV ITRs (pAAV/Ad [28]). pAAV/Ad provides all elements of pSub201 in trans but is unable to integrate due to the absence of ITRs. Cell lines were maintained up to 6 weeks as previously described. Total genomic DNA from 95 clonal isolates was analyzed by Southern blotting and PCR, and results indicate that none of the cell lines retained the pTRUF2 GFP or Neor sequence (Table 2). To alleviate the possibility of transgene toxicity, we also cotransfected HeLa cells with an rAAV plasmid containing a lacZ transgene flanked by AAV ITRs (p2ITRLacZ) and pAAV/Ad. None of the 48 cell lines tested retained the lacZ transgene (Table 2). Importantly, when genomic DNA was examined for S1 disruptions mediated by Rep from pAAV/Ad, they were present at a level similar to that seen with pSub201 (data not shown).

To determine if pTRUF2 was inhibitory to the integration process, we cotransfected HeLa cells with pSub201 and pTRUF2 and grew cell lines for 6 weeks, as described above. PCR and Southern blotting were used to assess the persistence of the transgenes (Fig. 5) and the level of AAVS1 disruption (data not shown). Consistent with previous data, we found that pSub201 DNA was maintained in 12% of cell lines whereas pTRUF2 was not found in any of the cell lines tested, giving a frequency of pTRUF2 persistence of less than 1% (Table 2).

FIG. 5.

Stable wtAAV but not rAAV integrants occur in a cotransfection of pSub201 and pTRUF2. HeLa cells were cotransfected with pSub201 and pTRUF2. Clonal cell lines were grown for 6 weeks and processed as previously described. Southern blots were probed with 32P-labeled Rep (A) or GFP (B) DNA. HNC, negative control HeLa cell DNA; GPC, GFP-positive cell DNA. Vertical arrows indicate rep-containing clones (A).

p5-rep sequence is essential for efficient site-specific integration of AAV.

Results so far have indicated that there is a difference in the abilities of ds wtAAV and rAAV to site specifically integrate and hence persist in cells after more than 30 cell divisions. One possible explanation for this difference is that the rAAV vectors lacked a specific element that was essential for site-specific integration. To determine if a cis-acting element, in addition to AAV ITRs, was functioning as an integration efficiency element, two partial rAAV plasmids were constructed (Fig. 6). The first contains the first half of the wtAAV genome including the AAV rep gene followed by a gfp transgene (pRepGFP). The second contains the AAV p5 promoter (mu 1-6.7) and the CMV-gfp transgene followed by the second half of the wtAAV genome including the AAV cap gene sequences (pGFPCap).

HeLa cells were cotransfected with these partial rAAV plasmids and pSub201 or pAAV/Ad to provide Rep in trans. In addition, we transfected pRepGFP alone since it contains AAV ITRs and encodes Rep, thereby supplying both factors thought necessary for site-specific integration. Again the cell lines were grown for 6 weeks and then screened for transgene sequence and AAVS1 disruptions.

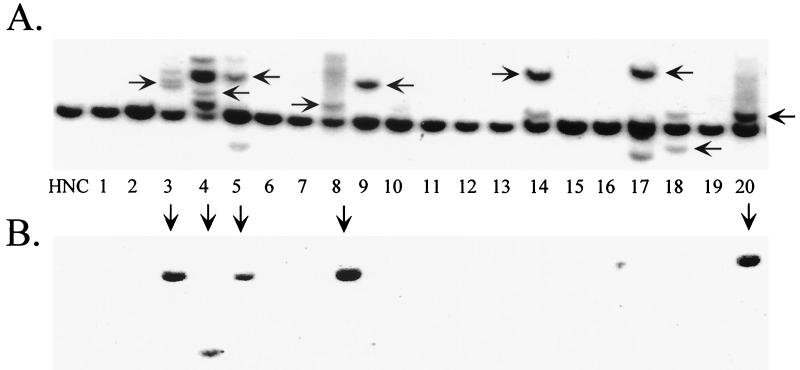

More than 150 clones were screened for pRepGFP DNA, and a sample of the Southern blotting data is shown in Fig. 7. pRepGFP integrated at a rate of approximately 13%, similar to the 12% integration efficiency observed with pSub201 (Table 2). This suggested that pRepGFP contains all components necessary for site-specific integration of AAV. Therefore, it appears that the p5-rep sequence that is present in pRepGFP and pSub201, but absent in pTRUF2 and p2ITRLacZ, is critical for efficient AAV integration.

FIG. 7.

rAAV plasmids containing p5-rep in cis efficiently mediate integration. pRepGFP-transfected HeLa cell lines were grown and processed as previously described. (A) Hybridization to AAVS1 probe. (B) Hybridization to Rep probe. HNC, negative control HeLa cell DNA. Horizontal arrows indicate disruptions of the chromosome 19 AAVS1 8-kb EcoRI genomic fragment (A), and vertical arrows indicate rep-containing clones (B).

When HeLa cells were cotransfected with pRepGFP and pSub201, some cell lines contained DNA from both plasmids, suggesting that the two plasmids were integrating together. However, more cell lines contained DNA from either pRepGFP or pSub201, indicating that both plasmids are able to site specifically integrate independently of each other (data not shown).

pGFPCap integrated in only 5% of 194 cell lines tested, indicating a slight deficiency in pGFPCap compared to pRepGFP and pSub201 (12 to 13%) (Table 2). However, it persisted in a higher percentage of cell lines than did the two fully recombinant AAV plasmids (pTRUF2 and p2ITRLacZ), which persisted in less than 1% of cell lines. We consider that the presence of the p5 promoter in pGFPCap caused an increase in the efficiency of rAAV site-specific integration. We are currently investigating the potential basis of the twofold difference in integration efficiency observed when comparing the two partial replacement constructs of rAAV. The pGFPCap results complement those of pRepGFP, suggesting that the AAV p5-rep sequence is required in cis to obtain efficient site-specific integration of a transgene. This p5-rep element is necessary in cis, possibly in combination with the ITR elements flanking the transgene and the rep gene in trans.

pAd-Rep78 mediates S1 disruptions and integration of pGFPCap.

The studies characterizing the integration efficiency of wtAAV and rAAV vectors were initiated through our interest in generating AAV-Ad chimeric constructs able to mediate Rep-dependent integration. Having identified the need for the p5-rep sequence as an efficiency element for integration, we wanted to confirm that the T7-Rep cassette could mediate efficient integration of the pGFPCap plasmid. pGFPCap-transfected HeLa cell lines were cotransfected with pAd-Rep78 or superinfected with Ad-Rep78, and clonal cell lines were grown and processed as previously described. Southern blot analyses suggested that both plasmid and viral T7-Rep cassettes were able to induce targeted integration of pGFPCap. The pAd-Rep plasmid mediated rAAV integration in 7% of cell lines analyzed, similar to that for mediated Rep expressed in trans from pSub201 or pAAV/Ad. These results demonstrate that pAd-Rep78 expresses T7-Rep at a level that is able to mediate site-specific integration of a transgene. The Ad-Rep78 virus induced pGFPCap integration in 2% of cell lines and also had a lower frequency of overall S1 disruptions. The lower efficiency of disruptions and integrations indicates that Rep expression from the Ad vector is not identical (most likely in amount) to that seen with the plasmid. Importantly, even with this modest result, the level of pGFPCap targeted integration is 30-fold higher than that observed with pTRUF2 in the presence of Ad-Rep78. Based on these promising results, further manipulation of the Ad-AAV hybrid virus should allow us to accomplish efficient site-specific integration of an rAAV cassette.

DISCUSSION

The goal of developing gene transfer vectors able to efficiently carry out site-specific integration of a target transgene is a long-term objective of the majority of gene therapy applications. For a variety of reasons, present vector systems fall short of this objective. In this study we investigated the hypothesis that an Ad vector could be adapted to utilize the integration mechanism of AAV and generate chimeric constructs that could bring us closer to a system able to fulfill our long-term gene transfer objectives. Our studies indicate that first-generation Ad vectors may be adaptable to this goal; however, the more important finding from this study was that traditional rAAV vectors are lacking an important integration efficiency element. In the presence of the p5-rep integration efficiency element, we have found that the vast majority of AAV integrants (over 90%) are occurring in a site-specific manner. Additionally, we present evidence that a significant number of cell lines undergo AAVS1 site rearrangement in the absence of stable AAV DNA integration.

Recchia and coworkers generated a helper-dependent Ad-Rep vector and tested its ability to mediate site-specific integration by coinfecting it with an Ad that contained ITR-flanked GFP and hygromycin resistance transgenes (26). In agreement with our studies, Recchia et al. found a relatively low efficiency of persistently hygromycin-resistant cell lines (estimated at 0.3%). In their studies, a third of the selected cell lines contained GFP localized to chromosome 19, as indicated by fluorescent in situ hybridization analysis. The Ad construction strategy of Recchia et al. was based on a second-generation gutless vector, and in contrast, our system is based on an E1− E3− vector. Accordingly, we wanted to test the hypothesis that expression from Ad transcription units (such as E2 and E4) may have a negative influence on integration by AAV. Based on our superinfection and cotransfection experiments, we found that wtAAV could integrate in a background of infection by first-generation viruses, albeit at slightly lower levels than in the absence of Ad elements. Despite several experimental differences including type of target cell, promoter setup, Ad-AAV chimeric vector design, and presence or absence of antibiotic selection, a common feature shared between the study by Recchia et al. and our study is that the efficiency of traditional rAAV-mediated transgene persistence is extremely low.

To establish a baseline of AAV site-specific integration efficiency in our system, we transfected HeLa cells with a wtAAV plasmid vector, pSub201. After screening DNA from more than 250 pSub201-transfected cell lines, we found that 12% contained the rep gene and approximately twice as many had disruptions at the AAVS1 site (Fig. 3 and Table 2). The efficiency of site-specific integration and the lack of integration into non-AAVS1 chromosomal locations strongly reinforce the utility of the AAV integration system for gene therapy applications. That AAVS1 chromosome disruptions routinely occurred in over 20% of cell lines, often in the absence of transgene integration, indicates a need to better understand the consequences of Rep-mediated chromosomal disruptions. This observation is consistent with previous studies that have also identified Rep-mediated AAVS1 disruptions occurring in the absence of integrated vector DNA (2, 34, 44).

Cotransfection of pTRUF2 with a variety of Rep-expressing constructs, including pSub201, failed to result in stable gfp-containing AAVS1 integrants (all in the absence of drug selection). Based on these observations, we hypothesized that pTRUF2 lacked a critical element that is required for efficient targeted AAV integration. It has been well documented elsewhere that the AAV ITR elements flanking a transgene and the presence of the Rep protein in trans represent the prominent elements required for site-specific integration (8, 18, 30, 42, 43). The majority of assays used to determine these requirements relied on drug selection as a mechanism to reduce background from nontransformed cell lines and had not focused on comparing the efficiency of integration of the minimal cassette to that for a wtAAV cassette. Since the emphasis of our analysis was integration efficiency in the absence of drug selection (a practical consideration for in vivo gene transfer applications), our studies clearly reveal a defect in the minimal rAAV vector strategy with respect to integration efficiency.

Two partial rAAV vectors were characterized in our long-term persistence assay, pRepGFP and pGFPCap. wt levels of targeted integration were obtained with pRepGFP. This construct expresses Rep from the wt p5 promoter and is deleted in the right-end AAV sequence, which contains the cap ORF (Fig. 6). The data indicate that cap sequence is not required for efficient site-specific integration of an ITR-flanked transgene and are in agreement with previous studies (30, 34). Using a vector containing p5-rep sequence (including the intact rep ORF) in cis but outside GFP-flanked ITRs, Balague and coworkers found that such a vector persisted in ninefold-more cell lines than did an equivalent plasmid without p5-rep sequence (2). In addition, the p5-rep sequence mediated site-specific integration at a level comparable to the 12% targeted integration efficiency that we observed. In another study, Pieroni et al. used similar plasmid vectors consisting of neomycin resistance and GFP transgenes between ITRs with and without p5-rep sequence (again expressing the full rep ORF) outside the ITR elements (25). Despite using antibiotic selection, they found that the p5-rep sequence was critical for site-specific integration of transgenes in HeLa cells. Both of these studies came to the conclusion that Rep is necessary in trans for targeted AAV integration. It is our view that Rep in trans is necessary but not sufficient for efficient site-specific integration to occur. In our studies we have shown that cotransfection of Rep-expressing plasmids with an ITR-flanked transgene does not result in efficient integration. It is our view that the Balague and Pieroni systems supplied two distinct elements, the Rep protein in trans and an AAV integration efficiency element in cis. Interestingly, based on the constructs used in their studies, the cis integration element can be located inside or outside the ITR-flanked transgene, indicating functional flexibility in position and orientation of the integration element.

Importantly, the results characterizing integration by the rAAV construct pGFPCap indicate that the entire rep ORF is not required in cis for efficient integration. This construct contains the dispensable cap sequence element but lacks the majority of the Rep coding region. The pGFPCap construct also includes 526 bp of DNA containing the entire p5 promoter, which flanks the left AAV ITR. Analysis of clonal cell lines isolated from transfections of pGFPCap with Rep supplied in trans via either pSub201 or pAAV/Ad showed that 5% were positive for GFP and AAVS1 disruptions. Although the level of integration was below that seen with wtAAV or pRepGFP, this is the first construct that separates the p5-rep promoter element from Rep expression and maintains a high level of site-specific integration. Several factors may be contributing to the reduction in integration efficiency seen with pGFPCap (5% versus 12 to 13% integration of pSub201 or pRepGFP), including the presence of additional sequence elements or the proximity of neighboring transcription units (CMV-gfp), and this is currently being investigated.

Involvement of the p5-rep promoter region in the wtAAV integration event has precedent. Studies by Giraud et al. (11) and Samulski et al. (29) demonstrated that junction fragments of wtAAV integrants into episomal AAVS1 plasmids or chromosomal regions occur predominantly within two AAV sequence elements, the ITRs and the p5 promoter region. More recently, Tsunoda and coworkers used HeLa cells subjected to lipofection to study junctions between the AAV plasmid and the AAVS1 site that formed during site-specific integration (36). Using a plasmid containing p5-rep and Neor genes flanked by AAV ITRs, they found that most junctions occurred within the p5 promoter region of the plasmid DNA. These studies suggest that the p5 promoter that contains an RBE (21) might be a hot spot for targeted AAV integration. In addition, Tullis and Shenk (37) showed that a p5-rep sequence functions in cis to increase the efficiency of AAV replication. Finally, using an in vitro replication system Nony and coworkers recently published a study which suggested that a p5-rep sequence between nucleotides 190 and 540 of the wtAAV-2 genome promoted efficient replication of rAAV plasmid vectors (23, 37). Since the p5-rep sequence identified by Nony et al. is present in the pGFPCap and pRepGFP constructs, we propose that this cis-acting replication element is also functioning as an enhancer of integration.

Further studies will be required to fully understand the relationship between the newly identified enhancer element and the RBE-terminal resolution site of the ITR with respect to the mechanism of integration. It is also likely that the delicate balance of regulated rep gene expression that occurs during the life cycle of AAV contributes significantly to the overall efficiency of integration. Vectors that regulate Rep expression in a manner that optimizes integration and yet minimizes unwanted chromosomal disruptions are a critical area that has not been developed. Incorporating these new insights into a variety of gene transfer strategies, including the Ad-AAV chimeric strategy that initiated these studies, should make a significant contribution toward achieving the long-term goal of site-specific integration of a therapeutic gene.

Acknowledgments

We thank Christopher Colon for the FACS sorting.

This work was supported by NIH grant P50 HL59312.

REFERENCES

- 1.Andrews, N. C., and D. V. Faller. 1991. A rapid micropreparation technique for extraction of DNA-binding proteins from limiting numbers of mammalian cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 19:2499.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Balague, C., M. Kalla, and W. W. Zhang. 1997. Adeno-associated virus Rep78 protein and terminal repeats enhance integration of DNA sequences into the cellular genome. J. Virol. 71:3299-3306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beaton, A., P. Palumbo, and K. I. Berns. 1989. Expression from the adeno-associated virus p5 and p19 promoters is negatively regulated in trans by the rep protein. J. Virol. 63:4450-4454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berns, K. I., and R. M. Linden. 1995. The cryptic life style of adeno-associated virus. Bioessays 17:237-245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bertran, J., Y. Yang, P. Hargrove, E. F. Vanin, and A. W. Nienhuis. 1998. Targeted integration of a recombinant globin gene adeno-associated viral vector into human chromosome 19. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 850:163-177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chiorini, J. A., C. M. Wendtner, E. Urcelay, B. Safer, M. Hallek, and R. M. Kotin. 1995. High-efficiency transfer of the T cell co-stimulatory molecule B7-2 to lymphoid cells using high-titer recombinant adeno-associated virus vectors. Hum. Gene Ther. 6:1531-1541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dignam, J. D., P. L. Martin, B. S. Shastry, and R. G. Roeder. 1983. Eukaryotic gene transcription with purified components. Methods Enzymol. 101:582-598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Flotte, T. R., and B. J. Carter. 1995. Adeno-associated virus vectors for gene therapy. Gene Ther. 2:357-362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gall, J. G. D., and E. Falck-Pedersen. 1998. Use and application of adenovirus expression vectors, p. 90.1-90.28. In D. L. Spector, R. Goldman, and L. Leinwand (ed.), Cells: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Plainview, N.Y.

- 10.Giraud, C., E. Winocour, and K. I. Berns. 1994. Site-specific integration by adeno-associated virus is directed by a cellular DNA sequence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:10039-10043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Giraud, C., E. Winocour, and K. I. Berns. 1995. Recombinant junctions formed by site-specific integration of adeno-associated virus into an episome. J. Virol. 69:6917-6924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Im, D. S., and N. Muzyczka. 1990. The AAV origin binding protein Rep68 is an ATP-dependent site-specific endonuclease with DNA helicase activity. Cell 61:447-457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Im, D. S., and N. Muzyczka. 1992. Partial purification of adeno-associated virus Rep78, Rep52, and Rep40 and their biochemical characterization. J. Virol. 66:1119-1128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kotin, R. M. 1994. Prospects for the use of adeno-associated virus as a vector for human gene therapy. Hum. Gene Ther. 5:793-801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kotin, R. M., M. Siniscalco, R. J. Samulski, X. D. Zhu, L. Hunter, C. A. Laughlin, S. McLaughlin, N. Muzyczka, M. Rocchi, and K. I. Berns. 1990. Site-specific integration by adeno-associated virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 87:2211-2215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lamartina, S., G. Roscilli, D. Rinaudo, P. Delmastro, and C. Toniatti. 1998. Lipofection of purified adeno-associated virus Rep68 protein: toward a chromosome-targeting nonviral particle. J. Virol. 72:7653-7658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Laughlin, C. A., J. D. Tratschin, H. Coon, and B. J. Carter. 1983. Cloning of infectious adeno-associated virus genomes in bacterial plasmids. Gene 23:65-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Linden, R. M., and K. I. Berns. 1997. Site-specific integration by adeno-associated virus: a basis for a potential gene therapy vector. Gene Ther. 4:4-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Linden, R. M., P. Ward, C. Giraud, E. Winocour, and K. I. Berns. 1996. Site-specific integration by adeno-associated virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:11288-11294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Linden, R. M., E. Winocour, and K. I. Berns. 1996. The recombination signals for adeno-associated virus site-specific integration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:7966-7972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McCarty, D. M., D. J. Pereira, I. Zolotukhin, X. Zhou, J. H. Ryan, and N. Muzyczka. 1994. Identification of linear DNA sequences that specifically bind the adeno-associated virus Rep protein. J. Virol. 68:4988-4997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miller, S. A., D. D. Dykes, and H. F. Polesky. 1988. A simple salting out procedure for extracting DNA from human nucleated cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 16:1215.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nony, P., J. Tessier, G. Chadeuf, P. Ward, A. Giraud, M. Dugast, R. M. Linden, P. Moullier, and A. Salvetti. 2001. Novel cis-acting replication element in the adeno-associated virus type 2 genome is involved in amplification of integrated rep-cap sequences. J. Virol. 75:9991-9994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Palombo, F., A. Monciotti, A. Recchia, R. Cortese, G. Ciliberto, and N. La Monica. 1998. Site-specific integration in mammalian cells mediated by a new hybrid baculovirus-adeno-associated virus vector. J. Virol. 72:5025-5034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pieroni, L., C. Fipaldini, A. Monciotti, D. Cimini, A. Sgura, E. Fattori, O. Epifano, R. Cortese, F. Palombo, and N. La Monica. 1998. Targeted integration of adeno-associated virus-derived plasmids in transfected human cells. Virology 249:249-259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Recchia, A., R. J. Parks, S. Lamartina, C. Toniatti, L. Pieroni, F. Palombo, G. Ciliberto, F. L. Graham, R. Cortese, N. La Monica, and S. Colloca. 1999. Site-specific integration mediated by a hybrid adenovirus/adeno-associated virus vector. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:2615-2620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Samulski, R. J., L. S. Chang, and T. Shenk. 1987. A recombinant plasmid from which an infectious adeno-associated virus genome can be excised in vitro and its use to study viral replication. J. Virol. 61:3096-3101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Samulski, R. J., L. S. Chang, and T. Shenk. 1989. Helper-free stocks of recombinant adeno-associated viruses: normal integration does not require viral gene expression. J. Virol. 63:3822-3828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Samulski, R. J., X. Zhu, X. Xiao, J. D. Brook, D. E. Housman, N. Epstein, and L. A. Hunter. 1991. Targeted integration of adeno-associated virus (AAV) into human chromosome 19. EMBO J. 10:3941-3950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shelling, A. N., and M. G. Smith. 1994. Targeted integration of transfected and infected adeno-associated virus vectors containing the neomycin resistance gene. Gene Ther. 1:165-169. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Smith, R. H., and R. M. Kotin. 1998. The Rep52 gene product of adeno-associated virus is a DNA helicase with 3′-to-5′ polarity. J. Virol. 72:4874-4881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Srivastava, A. 1987. Replication of the adeno-associated virus DNA termini in vitro. Intervirology 27:138-147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Srivastava, A., E. W. Lusby, and K. I. Berns. 1983. Nucleotide sequence and organization of the adeno-associated virus 2 genome. J. Virol. 45:555-564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Surosky, R. T., M. Urabe, S. G. Godwin, S. A. McQuiston, G. J. Kurtzman, K. Ozawa, and G. Natsoulis. 1997. Adeno-associated virus Rep proteins target DNA sequences to a unique locus in the human genome. J. Virol. 71:7951-7959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Trempe, J. P., E. Mendelson, and B. J. Carter. 1987. Characterization of adeno-associated virus rep proteins in human cells by antibodies raised against rep expressed in Escherichia coli. Virology 161:18-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tsunoda, H., T. Hayakawa, N. Sakuragawa, and H. Koyama. 2000. Site-specific integration of adeno-associated virus-based plasmid vectors in lipofected HeLa cells. Virology 268:391-401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tullis, G. E., and T. Shenk. 2000. Efficient replication of adeno-associated virus type 2 vectors: a cis-acting element outside of the terminal repeats and a minimal size. J. Virol. 74:11511-11521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Urcelay, E., P. Ward, S. M. Wiener, B. Safer, and R. M. Kotin. 1995. Asymmetric replication in vitro from a human sequence element is dependent on adeno-associated virus Rep protein. J. Virol. 69:2038-2046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Weitzman, M. D., K. J. Fisher, and J. M. Wilson. 1996. Recruitment of wild-type and recombinant adeno-associated virus into adenovirus replication centers. J. Virol. 70:1845-1854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Weitzman, M. D., S. R. Kyostio, R. M. Kotin, and R. A. Owens. 1994. Adeno-associated virus (AAV) Rep proteins mediate complex formation between AAV DNA and its integration site in human DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:5808-5812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wonderling, R. S., and R. A. Owens. 1996. The Rep68 protein of adeno-associated virus type 2 stimulates expression of the platelet-derived growth factor B c-sis proto-oncogene. J. Virol. 70:4783-4786. (Erratum, 70:9084.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yang, C. C., X. Xiao, X. Zhu, D. C. Ansardi, N. D. Epstein, M. R. Frey, A. G. Matera, and R. J. Samulski. 1997. Cellular recombination pathways and viral terminal repeat hairpin structures are sufficient for adeno-associated virus integration in vivo and in vitro. J. Virol. 71:9231-9247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Young, S. M., Jr., D. M. McCarty, N. Degtyareva, and R. J. Samulski. 2000. Roles of adeno-associated virus Rep protein and human chromosome 19 in site-specific recombination. J. Virol. 74:3953-3966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Young, S. M., Jr., and R. J. Samulski. 2001. Adeno-associated virus (AAV) site-specific recombination does not require a Rep-dependent origin of replication within the AAV terminal repeat. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:13525-13530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhou, X., I. Zolotukhin, D. S. Im, and N. Muzyczka. 1999. Biochemical characterization of adeno-associated virus Rep68 DNA helicase and ATPase activities. J. Virol. 73:1580-1590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zolotukhin, S., M. Potter, W. W. Hauswirth, J. Guy, and N. Muzyczka. 1996. A “humanized” green fluorescent protein cDNA adapted for high-level expression in mammalian cells. J. Virol. 70:4646-4654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]