Abstract

Reagents for proteome research must of necessity be generated by high throughput methods. Apta mers are potentially useful as reagents to identify and quantitate individual proteins, yet are currently produced for the most part by manual selection procedures. We have developed automated selection methods, but must still individually purify protein targets. Therefore, we have attempted to select aptamers against protein targets generated by in vitro transcription and translation of individual genes. In order to specifically immobilize the protein targets for selection, they are also biotinylated in vitro. As a proof of this method, we have selected aptamers against translated human U1A, a component of the nuclear spliceosome. Selected sequences demonstrated exquisite mimicry of natural binding sequences and structures. These results not only reveal a potential path to the high throughput generation of aptamers, but also yield insights into the incredible specificity of the U1A protein for its natural RNA ligands.

INTRODUCTION

The development of in vitro selection methods has potentiated the identification of nucleic acid-binding species (aptamers) and catalysts (aptazymes) that are proving increasingly useful in therapeutic and diagnostic applications (1–3). However, as information continues to accrue about the sequences of organismal genomes and the composition of organismal proteomes, it will be necessary to increase the throughput of aptamer selection methods in order to either quickly identify aptamers against novel targets or to generate aptamers against entire proteomes or metabolomes.

To this end, we have previously developed methods for the automated selection of aptamers (4–6). We initially established a rudimentary set of chemistries and robotic manipulations that facilitated the basic execution of nucleic acid selection and amplification (5). The original automated system was used for the selection of aptamers against isolated oligonucleotide or protein targets. For example, the non-nucleic acid-binding protein lysozyme was immobilized on streptavidin beads and anti-lysozyme aptamers that had reasonable affinities (Kd ≈ 31 nM) for the cognate protein and that inhibited enzymatic function were selected (6). The same procedures were applied in short order to a variety of other proteins, including CYT-18 (a tyrosyl-tRNA synthetase from the mitochondria of the fungus Neurospora crassa), MEK1 (a human MAP kinase kinase) and Rho (a transcriptional termination protein from the archaebacterium Thermotoga maritima). Each of the aptamers generated by automated selection procedures have demonstrated high specificity and affinity for their targets (Kd values in the pico- to mid-nanomolar range) (4). The current automated selection system can yield aptamers against virtually any compatible target within 3 days.

However, automated selection methods are still too low throughput to contemplate the acquisition of aptamers against all of the protein targets in a proteome. One of the primary limitations on the method is that target proteins must be individually acquired, most frequently by purification from an overproducer strain. To avoid this bottleneck, we have now attempted to generate aptamers against protein targets that have been directly transcribed and translated on the robotic workstation. Blackwell and Weintraub previously demonstrated that manual selections with double-stranded DNA libraries could be carried out against protein targets translated in vitro (7).

An initial selection was carried out against translated U1A protein, a component of the human spliceosome. The wild-type sequences that U1A binds to have been characterized in great detail (8–10) and the anti-U1A aptamers that were generated by automated selection methods mimic the wild-type sequences in every important detail. These results suggest that automated selection methods may soon prove capable of deciphering specific interactions between multiple different nucleic acid-binding proteins and cellular RNA sequences.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Oligonucleotides, genes and plasmids

The N-terminal RNA-binding domain of U1A was synthesized from 15 oligonucleotides using a PCR-based assembly method (11). The sequence of U1A was derived from GenBank accession no. M60784, modified to include the same mutations (Y31H and Q36R) that were present in the protein crystallized by Oubridge et al. (12). The assembled gene was sub-cloned into pET28a, yielding a gene encoding a fusion protein with an N-terminal 6× histidine tag. This was placed into an expression vector to create pJH-hisU1A. The sequence of the final construct was verified.

The assembled U1A gene fragment was used to generate a template for in vitro transcription and translation (TnT) reactions. Specifically, ‘splice-overlap extension’ (SOE) PCR (13) was used to attach sequences necessary to direct high level expression and quantitative biotinylation of U1A during in vitro coupled transcription–translation reactions (Fig. 1). The primers used during these experiments are described in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Scheme for in vitro transcription, translation and biotinylation. Splice-overlap extension was used to assemble 5′ and 3′ fragments onto genes of interest. The 5′ fragment contained a T7 promoter and biotin protein ligase (BPL) recognition sequence (‘biotag’). The 3′ fragment contained the gene for BPL (birA) and a T7 terminator. Transcription generated a dicistronic mRNA that when translated yielded a ‘biotagged’ gene of interest and functional BPL. Free biotin was covalently attached to the gene of interest by BPL and the tagged protein was purified from the reaction by capture with strepavidin.

Table 1. Primers listed in Materials and Methods.

Priming sequences are shown 5′→3′.

The 5′ region for SOE PCR is ∼150 bp in length. The T7 gene 10 promoter and translation initiation region (TIR) are included to enhance transcript stability and translation (14,15). Protein synthesis is then initiated with a 24 amino acid biotin acceptor peptide sequence (‘biotag’, MAGGLNDIFEAQKIEWHEDTGGSS) (16). A megaprimer containing both the TIR and the biotag was generated using primer AHX10, primer AHX47 and the Escherichia coli biotinylation and expression plasmid pDW363 (17). The 3′ region is ∼1050 bp in length. The birA gene is followed by the major transcription terminator signal for T7 RNA polymerase to enhance transcript stability (14). A megaprimer containing birA and the transcription terminator was generated using primer AHX33, primer AHX29 and pDW363. The assembled U1A gene was PCR amplified with primers (U1A.biotag and U1A.t0) that added overlap regions complementary to both megaprimers. The 3′ assembly junction creates an opal termination codon followed by a functional RBS for birA (17). SOE assembly was carried out with the two ‘rescue’ primers AHX31 and AHX30.

Initial in vitro transcription, translation and biotinylation experiments

The maltose-binding protein (MBP) gene with the N-terminal biotin acceptor peptide from pDW363 (17) was PCR amplified using primers AHX10 and AHX32. The final product contained a suitable ribosome-binding site for birA after the mbp termination codon. Standard PCR and SOE were performed using YieldAce DNA polymerase (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA), which outperformed other polymerases in terms of yield, especially with SOE. Primers were gel purified to ensure efficient SOE. In order to determine whether endogenous biotin protein ligase (BPL) was sufficient to biotinylate protein targets, the mbp gene was separately merged with two different birA variants (18). The first construct was generated using primers AHX29 and AHX55 and encoded a short, five amino acid fragment of the birA gene (MKDNT) followed by the T7 major terminator. The second construct was generated using primers AHX33 and AHX29 and encoded a full-length birA gene. The final SOE products were amplified using primers AHX30 and AHX31. DNA was purified using a QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA).

For the in vitro transcription and translation reaction, ∼1 µg of template was introduced into 50 µl T7 PROTEINscript-PRO reactions (Ambion, Austin, TX) supplemented with 10 µM d-biotin. Reactions were incubated at 37°C for 60 min. A control reaction without template was carried out simultaneously. Reactions were centrifuged (∼13 000 g, 15 min, 4°C). The supernatants were removed and designated ‘soluble fraction’ while the pellets were resuspended in 50 µl of water and designated ‘insoluble fraction’. Samples (10 µl) were combined with Laemmli sample buffer (10 µl), boiled and loaded onto 10% Laemmli gels (19). Rainbow molecular weight markers (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ) were employed as standards.

Following semi-dry transfer to Immobilon P PVDF (Millipore, Bedford, MA), the membranes were blocked overnight with ∼25 ml of PBS containing 2% BSA (w/v). One membrane was probed with a 1:10 000 dilution (v/v) of rabbit anti-MBP serum (New England Biolabs, Beverly, MA) followed by a 1:30 000 dilution of anti-rabbit IgG– horseradish peroxidase (HRP) (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) to detect MBP. The other membrane was probed with a 1:100 000 dilution of avidin-conjugated HRP (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO) to detect biotinylated products. Sera probes were incubated with blots for 30–60 min. Blots were washed in 100 ml of PBS + 0.1% Tween-20, four times for 10 min each time. Blots were further washed with 2 × 100 ml of PBS for 10 min each. Development was for a few seconds using a SuperSignal West Pico chemiluminescence kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL) and signals were captured on X-ray film.

Having established that co-translation of BPL was necessary to ensure efficient biotinylation of the MBP target, we then applied the methodology to three other genes: chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (cat), neomycin phosphotransferase II (neo) and β-lactamase (amp). The cat gene was amplified using primers AHX51 and AHX52 with plasmid pHELP1 (available from the authors, derived from pACYC184) as template (20). The neo gene was amplified using primers AHX49 and AHX50 with plasmid pIMS102 (available from the authors, derived from pNEO) as template. The amp gene was amplified using AHX53 and AHX54 with plasmid pUC19 as template. SOE PCR was used to fuse each of the genes to the T7 promoter, biotag, birA and terminator. The dicistronic templates were purified and employed in in vitro transcription, translation and biotinylation reactions as above.

Protein targets were assayed for biotinylation. The soluble portions of reactions were applied to P6 desalting chromatography columns (Bio-Rad) to remove free biotin and then combined with 50 µl of glycerol to ensure precipitation-free storage at –20°C. A high-binding ELISA plate (Corning, New York, NY) was coated overnight at 4°C with 1 µg/ml Neutravidin (100 µl; Pierce) in 50 mM sodium bicarbonate buffer, pH 9.6. The Neutravidin-coated plate and an uncoated control plate were blocked overnight in ∼350 µl of PBS with 2% BSA (block). The TnT reactions in glycerol (10 µl) were serially diluted by factors of two in block and distributed onto both Neutravidin and control plates (100 µl final volumes). After 1 h, plates were washed three times with ∼350 µl of PBS + 0.1% Tween-20 and then twice with plain PBS. Primary antisera specific for the gene products were applied in 100 µl of block for 1 h. Anti-cat, anti-neo and anti-amp antisera (Eppendorf–5 prime, Boulder, CO) were used at 1:1000 dilutions in 100 µl of PBS; anti-mbp antisera (New England Biolabs) was used at a 1:10 000 dilution in 100 µl of PBS. Following washing, anti-rabbit IgG–HRP (Bio-Rad Laboratories) was applied at a 1:3000 dilution in 100 µl for 1 h. Following washing, the plates were developed for 10 min with 100 µl of o-phenylenediamine (Sigma-Aldrich) at 0.4 mg/ml. o-Phenylenediamine was originally dissolved in 50 mM phosphate citrate buffer pH 5.0, with 4 µl of 30% H2O2 added per 10 ml. Color development was stopped with 50 µl of 2–3 M sulfuric acid and the OD was measured at 492 nm on an ELISA plate reader (Bio-Tek, Winooski, VT). The blank plate was subtracted from the experimental plate to correct for background binding.

In vitro transcription and translation of U1A

The U1A–birA construct was transcribed and translated in vitro using the RTS 100 E.coli HY kit (Roche Diagnostics, Basel, Switzerland). In order to generate sufficient protein for the entire course of an automated selection experiment a quadruple sized reaction (200 µl) was carried out starting with 2 µg of DNA template. Biotin (14 µM final concentration) was also added at the start of the combined TnT reaction. The reaction was incubated at 30°C for 6 h, followed by incubation at 4°C for ∼4 h. Unincorporated biotin was removed by passing the entire reaction though a Bio-Spin 6 chromatography column (Bio-Rad). The purified, biotinylated protein sample was incubated with 2.4 mg of strepavidin-coated magnetic Dynabeads (Dynal, Oslo, Norway) in the presence of 1× selection binding buffer (1× SBB = 20 mM Tris pH 7.5, 100 mM KOAc, 5 mM MgCl2) for 15 min. Beads were thoroughly washed five times in 500 µl of selection buffer to remove any non-biotinylated protein.

Protein expression and biotinylation were verified by electroblotting and western blot analysis using strepavidin-conjugated alkaline phosphatase as a reporter for biotinylated proteins (Fig. 2). Aliquots of the TnT reaction (5 µl) were placed in 1 µl of β-mercaptoethanol (β-ME), 10 µl of water and 4 µl of 5× SDS–PAGE loading dye (250 mM Tris–HCl pH 6.8, 50% glycerol, 2.5% SDS, 142 mM β-ME, 0.05% bromophenol blue) and heat-denatured by boiling for 5 min. Half of the denatured sample (10 µl) was loaded onto a 12% acrylamide (29:1 acrylamide:bisacrylamide) denaturing protein gel on a MiniPROTEAN 3 gel rig (Bio-Rad). The gel was run until the bromophenol blue dye reached the bottom (∼30 min at 200 V). The gel was electroblotted onto Trans-Blot nitrocellulose (Bio-Rad) in a Mini Trans-Blot Electrophoretic Transfer Cell (Bio-Rad) in electroblotting buffer (10 mM NaHCO3, 3 mM NaCO3, 30% methanol, pH 9.9) for 90 min at 350 mA. The blot was blocked with 1× Tris-buffered saline and Tween-20 (TBST) for 30 min at room temperature with gentle agitation. Next, the blot was incubated with 3 µl of alkaline phosphatase-conjugated strepavidin (Promega, Madison, WI) in fresh 1× TBST buffer (15 ml) for 30 min with mild agitation. Unbound alkaline phosphatase was removed with three washes with 1× TBST (15 ml, 5 min each). Finally, the blot was briefly rinsed with deionized water and placed in 15 ml of Western Blue Stabilized Substrate for alkaline phosphatase (Promega) for 1–5 min.

Figure 2.

Detection of translated, biotinylated U1A. Expression of biotinylated U1A was assayed by western blot analysis. Biotinylated protein size standards are in the first lane. The second lane shows a no template control, while the third and fourth lanes show controls with gene products that were not biotinylated. The fifth lane contains an aliquot from an in vitro transcription and translation reaction with the biotagged U1A gene. The arrow indicates the translated, biotinylated U1A gene product. The ∼20 kDa band seen in all control and experimental lanes is thought to be biotin carboxy-carrier protein (BCCP), the single biotinylated protein in E.coli.

In vitro selection

Automated in vitro selection was carried out as previously described (4,6). In short, a RNA pool that contained 30 randomized positions (N30) (4,6,21) was used as a starting point for selection. The RNA was incubated in 1× SBB with biotinylated protein immobilized on 200 µg of streptavidin beads (sufficient to bind 4–8 × 1012 biotinylated antibody molecules). RNA–protein complexes were filtered from free RNA and weakly bound species were removed by washing with 4 × 250 µl of 1× SBB. Bound RNA molecules were eluted in water at 97°C for 3 min. RNA for additional rounds of selection was generated by reverse transcription, PCR and in vitro transcription (using primers 41.30 and 24.30). All of the reactions were carried out sequentially on a Beckman-Coulter (Fullerton, CA) Biomek 2000 automated laboratory workstation that had been specially modified and programmed to interface with a PCR machine (MJ Research, Waltham, MA) and a filtration plate device (Millipore).

Eighteen rounds of selection were performed against biotinylated U1A. In the first 12 rounds of selection 20 cycles of PCR were carried out, while in the last six rounds this number was decreased to 16 cycles to prevent overamplification of the selected pool; these parameters had been empirically determined during previous automated selection experiments (6). In the first 12 rounds of selection the wash buffer was 1× SBB. In the last six rounds of selection the stringency of the selection was increased by progressively increasing the monovalent salt concentration, as detailed in Table 2.

Table 2. Conditions for the automated selection of anti-U1A aptamers.

See Materials and Methods for details. The binding ability of the pool was assayed at 0, 6, 12 and 18 rounds.

The progress of selection was monitored every six rounds (6, 12 and 18) by placing [α-32P]-radiolabeled ribo- and deoxyribonucleotides in the amplification reactions and resolving amplification products by gel electrophoresis. The automated protocol included a provision to archive aliquots of the reverse transcription (10 µl, 10% of the total reaction) and in vitro transcription (10 µl, 10% of the total reaction) reactions. After the automated protocol had run its course, the aliquots (in standard stop dye) were run on 8% acrylamide– 7 M urea (19:1 acrylamide:bisacrylamide) denaturing gels. Decade RNA Markers (Ambion) were used as size standards. The gels were visualized using a PhosphorImager SI (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). In addition, single point binding assays were carried out with equimolar concentrations of protein and RNA samples (50 nM), as described below (see also Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Progress of automated U1A selection. Binding assays are shown for rounds 0, 6, 12 and 18 of the selection. The first column (light blue) shows the fraction of RNA captured in a standard binding assay. The second column (dark blue) shows the fraction of RNA captured when a high salt wash was used to remove non-specifically bound RNA.

High throughput sequencing

Aliquots (1 µl of a 50 µl archive) of RT–PCR reactions from a given round of selection were further amplified and then ligated into a thymidine-overhang vector (TA Cloning Kit; Invitrogen). Templates for sequencing reactions were generated from individual colonies via 50 µl colony PCR reactions (22) with standard M13 sequencing primers flanking the insertion site of the thymidine-overhang vector (primers M13 forward and M13 reverse). The PCR products were purified away from primers, salt and enzyme using a MultiScreen96-PCR clean-up plate (Millipore). Aliquots of the colony PCR reactions (5 µl) were developed on a 4% agarose gel to verify the insertion of aptamers into vectors.

Cycle sequencing reactions were performed using a CEQ DTCS Quick Start Kit (Beckman-Coulter) and the vendor’s modified M13 sequencing primer (primer –47 seq). Reaction assembly and cycling conditions were performed largely as described in the vendor’s instructions. Approximately 100 fmol of purified colony PCR products were used as templates and reactions were performed with half of the master mix concentration recommended in the instructions in order to minimize reagent use (4 µl of master mix in a 20 µl sequencing reaction, rather than 8 µl). Unincorporated dye was removed by size exclusion chromatography, as described in Beckman-Coulter Technical Application Information Bulletin T-1874A (http://www.beckman.com/Literature/BioResearch/T-1874A.pdf). Briefly, 45 µl of dry Sephadex G50 (Amersham-Pharmacia Biotech) was placed into each well of a MultiScreen HV plate using a MultiScreen 45 µl Column Leader (Millipore). The Sephadex chromatography resin was allowed to hydrate in 300 µl of water for 3 h at room temperature. After incubation, the resin was packed by centrifugation for 5 min at 1100 g. The columns were rinsed once with 150 µl of water and packed again at the same speed for the same time. The 20 µl sequencing reactions were loaded onto the tops of the columns using a multichannel micropipettor and spun again for 5 min at 1100 g. Purified samples were recovered from a CEQ Sample microplate (Beckman-Coulter) that had been placed below the chromatography plates before centrifugation. Recovered samples were dried under vacuum at room temperature. Pellets were resuspended in 40 µl of deionized formamide and developed on a CEQ 2000XL eight channel capillary DNA sequencer (Beckman-Coulter). Aptamer secondary structures were predicted using RNAstructure 3.6 by Mathews et al. (23).

Cellular expression of U1A

The plasmid pJH-hisU1A was transformed into BL21 cells (Stratagene). A 1 ml starter culture grown from a single plasmid was used to inoculate 50 ml of fresh LB. The culture was grown to an OD600 of ∼0.6 at 37°C and protein expression was induced by the addition of IPTG to a final concentration of 840 µM. The induced culture was grown for an additional 3 h at 37°C. Cells were pelleted at 5000 g and lysed in B-PER (Pierce), 10 U DNase (Invitrogen) and 10 mM MgCl2 in a total volume of 5 ml. After incubation at room temperature for 15 min, cellular debris was pelleted at 13 000 g. The supernatant was further purified by nickel-chelation chromatography. IMAC resin (2 ml; Amersham-Pharmacia Biotech) was equilibrated with 4 ml of water, followed by 4 ml of charging buffer (50 mM NiCl2). The column was equilibrated with 10 ml of protein binding buffer (PBB; 1× PBB = 50 mM Tris pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM imidazole). Clarified supernatant (∼15 ml) was loaded and the column was washed with 4 ml of 1× PBB and 15 ml of wash buffer (50 mM Tris pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 50 mM imidazole). The U1A protein was eluted by the addition of 3 ml of elution buffer (50 mM Tris pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 500 mM imidazole); 500 µl fractions were collected for gel analysis. Fractions containing significant amounts of U1A were pooled and dialyzed in 50 mM Tris pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl with four buffer exchanges of 500 ml every 3 h at 4°C in order to remove imidazole from the preparation. Finally, the absorbance at 280 nm was used to determine protein concentration (extinction coefficient = 5442 M–1 cm–1).

Binding constants

Plasmids containing individual aptamers were used to generate transcription templates via PCR. Transcription reactions were carried out with an AmpliScribe T7 RNA transcription kit (Epicentre, Madison, WI) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, except that incubation was at 42°C rather than 37°C. Aptamers were purified on denaturing polyacrylamide gels (24), dephosphorylated and radiolabeled with [γ-32P]ATP (25). Radiolabeled RNA was extracted with phenol:chloroform (1:1) and unincorporated nucleotides were removed using size exclusion spin columns (Princeton Separations, Adelphia, NJ).

Nitrocellulose filter binding assays were employed to determine the dissociation constants of aptamer–protein complexes (25). A standard protocol was automated using the Biomek 2000 automated laboratory workstation and a modified Minifold I filtration manifold (Schleicher & Schuell, Keene, NH). RNA samples in 1× SSB were thermally equilibrated at 25°C for 30 min. The RNA concentration for binding reactions was kept constant at a final concentration of 200 pM while the concentration of U1A ranged from 1 µM down to 17 pM (11 different concentrations). Equal volumes (60 µl) of RNA and U1A were incubated together for 30 min at room temperature in 1× SBB. The binding reactions (100 µl) were filtered through a sandwich of Protran pure nitrocellulose (Schleicher & Schuell) and Hybond N+ nylon transfer membrane (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) that had been assembled in the modified Minifold I vacuum manifold. The filters were washed three times with 125 µl of 1× SBB. The amount of radiolabeled RNA captured from a reaction onto the nitrocellulose membrane was quanititated using a Phosphor Imager SI (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). The log of U1A concentration was plotted against the amount of RNA bound. Data were fitted to the equation y = (a·b)/(b + x) + C, where C is the fraction of RNA bound to the nitrocellulose at zero protein concentration, b is the maximum fraction bound, x is the fraction of RNA bound to U1A and a is the dissociation constant for the RNA–protein complex. Assays were performed in triplicate and standard deviations were calculated. The 21 nt synthetic RNA (AAUCCAUUGCACUCCGGAUUU) previously employed in structural studies of the U1A protein was used as a positive control (12).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

From gene to biotinylated protein

While we have previously automated the in vitro selection of aptamers that target proteins (4–6), our methods are currently limited to purified proteins. Ultimately, the need to purify protein targets individually would drastically reduce the speed with which aptamers could be generated against proteomes and would therefore reduce the utility of aptamers as reagents for proteome analysis. Therefore, we have sought to increase selection throughput by generating protein targets via in vitro transcription and translation. Moreover, in order to manipulate protein targets during automated selection, we have attempted to introduce a biotin tag during the in vitro synthesis procedure.

A number of kits were available for the in vitro transcription and translation of genes. Ultimately, we found that the Roche RTS 100 E.coli HY kit worked well with the automated selection procedures we had previously established. In order to biotinylate translated proteins, templates were modified (Fig. 1) so that translated proteins would contain an N-terminal peptide tag (MAGGLNDIFEAQKIEWHEDTGGSS) that was an efficient substrate for BPL, the product of the birA gene (26–28). The ε-amino group of the single lysine residue in the BPL recognition peptide becomes covalently linked to biotin (29). Biotin ligase can either be co-translated or added as a separate reagent.

Existing BPL present in E.coli S30 extracts proved insufficient to efficiently biotinylate target proteins. Therefore, the MBP gene (malE) was expressed in tandem with a downstream birA cistron. Following gel separation, an anti-MBP antibody was used to confirm that roughly equal amounts of MBP were synthesized. However, when avidin–HRP was used as a probe it was apparent that only the dicistronic mbp–birA template directed efficient biotinylation. The band at ∼20 kDa that stains intensely with avidin–HRP is E.coli biotin carboxyl-carrier protein (BCCP), which is present in the S30 extracts used for in vitro translation (Fig. 2). MBP and three other biotinylated protein targets were immobilized in Neutravidin-coated ELISA wells and detected with cognate sera (Fig. 3). These results indicated that in vitro translated and biotinylated proteins could fold into native structures that present epitopes similar to those found in vivo. The amounts of in vitro translation and biotinylation reactions necessary to saturate microwells for selection experiments proved to be relatively small (1% of reaction volume), indicating that this procedure should be useful for multiplex formats, such as the acquisition of aptamers against multiple proteins in an organismal proteome.

Figure 3.

Detection of in vitro expressed and biotinylated products. Four constructs were investigated for their ability to bind to neutravidin-coated microwells after in vitro expression and biotinylation: β-lactamase (amp), chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (cat), aminoglycoside phosphotransferase (neo) and maltose-binding protein (mbp). Purified, translated and biotinylated products were serially diluted and probed with their respective antisera and again with anti-rabbit IgG–HRP. Signal intensity is measured after incubation of the bound complexes with o-phenylenediamine at 492 nm.

We have previously carried out selections against chemically biotinylated target proteins (4,6). Unfortunately, chemical biotinylation generally generates a population of molecules with differing amounts of biotinylation at different conjugation sites, typically α-amino groups on a protein. Thus, multiple different epitopes are presented during selection. A biotinylation tag obviates this problem and a relatively homogeneous set of epitopes should be present during the selection. Additionally, chemical biotinylation may block an active or allosteric site of the protein, while specific biotinylation at the N-terminus is less likely to interfere with function.

In vitro selection of aptamers that bind to translated, biotinylated U1A

As in our previous automated selection experiments, biotinylated protein targets are loaded onto streptavidin beads and incubated with RNA libraries. Bound RNA molecules are sieved from unbound by filtration; the use of beads facilitates robotic manipulation. The beads are directly transferred to a thermal cycler and RNA is prepared for the next round of selection by a combination of reverse transcription, PCR and in vitro transcription. The entire selection procedure can be iteratively carried out using a Beckman-Coulter Biomek 2000 automated laboratory workstation that has been specially modified and programmed to interface with a thermal cycler. The selection robot can carry out six cycles of selection per day; a typical selection is done in 2–3 days. This represents an increase in speed of at least an order of magnitude relative to manual selection methods, and up to eight targets can be handled in parallel by the Biomek 2000. Overall, these methods allow us to go from a gene sequence to high affinity binding reagents for the protein product of that gene in under 1 week.

As an initial target, we attempted to select aptamers against a RNA-binding domain of the U1A protein. U1A is a member of the U1 snRNP, a component of the nuclear spliceosome that participates in processing of pre-mRNA splicing (30). The first 96–100 amino acids of U1A are responsible for binding hairpin II of U1 snRNA in the splicing complex (31). Its N-terminal portion, containing one of the two RNP domains of U1A, has been shown to maintain the binding characteristics and sequence specificity of the full-length protein (9,10). Most importantly, U1A has previously been targeted by in vitro selection experiments (8) and thus we could be assured that it would likely generate aptamers.

As the selection progressed, the DNA and RNA pools produced at each round were examined by denaturing gel electrophoresis (Fig. 4). The lengths of the DNA and RNA molecules were remarkably uniform, especially given that the number of cycles and incubation times used for DNA and RNA amplification were pre-set. The consistent sizes of amplification products are in part a result of our prior optimization of PCR for automated selection procedures (4–6). The stringency of the selection was increased by increasing the salt concentration from 100 mM during the first 12 rounds (2 days) of selection to 300 mM at round 13. It is interesting to note that the amount of RNA that is amplified following this round seems to drop, just as though the increase in stringency reduced the amount of pool that survives the selection. A further increase in stringency was introduced at round 15 by increasing the salt concentration to 600 mM.

Figure 4.

Nucleic acid products during automated U1A selection. Radioactive reaction products from RT–PCR and transcription reactions during automated selection were resolved on denaturing polyacrylamide gels. RNA (80 nt) and DNA (99 nt) products are indicated by green and blue arrows, respectively. The round numbers are listed above the lanes.

Filter binding assays were employed to detect significant changes in the affinities of selected pools for U1A (Fig. 5). The initial pool showed significant binding to U1A, likely due to electrostatic interactions with the highly charged target protein (25,32) (+7.2 at pH 7). Binding assays were therefore also carried out at higher salt concentrations (1 M) to reduce this non-specific background binding signal. Six rounds of automated selection yielded no significant increase in apparent affinity, but a further six yielded an appreciable increase in signal (1.7-fold increase in binding signal even in the presence of high salt). The final six rounds, carried out under increasingly stringent conditions, yielded additional improvements in pool binding (3.1-fold increase in binding signal even in the presence of high salt). All binding assays were performed using a his-tagged U1A isolated from E.coli, rather than the biotin-tagged U1A generated by in vitro translation and biotinylation. The fact that binding did not appear to be dependent upon the type of tag present suggested that binding was specific for the RNP. It is interesting that no aptamers were isolated against BCCP, given that this protein was also always present as a target. It is likely that RNP is a better target for selection than BCCP. When ‘mock’ selections were carried out without the gene for U1A, aptamers against BCCP were isolated (data not shown).

Anti-U1A aptamers resemble natural binding sequences

The natural RNA ligands of the U1A RNP have been well characterized. Hairpin II of U1 snRNA is a short stem topped by a G:C base pair and a loop with the sequence 5′-AUUGCACUCC (Fig. 6A). The bold heptamer sequence has been shown to be critical for binding to U1A; for instance, G9 makes hydrophobic contacts with Arg52 and hydrogen bonding interactions with Arg52, Leu49, Asn15 and Lys50 of U1A (33,34). The other six bases form similar hydrophobic, hydrogen bonding and stacking interactions with other peptide backbone and side chain positions in the U1A protein (12,34). The last three bases (UCC) do not physically interact with the protein and act primarily as a spacer to close the loop (8,12,35,36). In addition, the U1A protein interacts in a similar manner with the 3′-UTR of its own mRNA (37,38), autoregulating its own expression by inhibiting polyadenylation and cleavage (12,39,40) (Fig. 6B). However, in this instance the canonical heptamer sequence is presented as an internal loop (Box II), rather than a hairpin loop. Following binding of one U1A monomer to the Box II internal loop, a second U1A monomer is recruited to bind to an adjacent internal loop containing a variant of the canonical heptamer, AUUGUAC (Box I).

Figure 6.

U1A binding elements. (A) U1 snRNA hairpin II; (B) the 3′-UTR of U1 mRNA. The heptamer sequence critical for recognition by U1A is highlighted with a black bar. The 3′-UTR of U1 mRNA (B) contains a second heptamer sequence (Box I) that contains a base change (AUUGUAC) at the fifth nucleotide. The critical C:G base pair that closes stem II and that precedes Box II is in bold. The adenosine found in the internal loop region of the 3′-UTR is also in bold. (C) Aptamer Family 1, drawn in a manner similar to (A). (D) Aptamer Family 2, drawn in a manner similar to (B). Residues contributred by the primer-binding sites are shown as dark yellow.

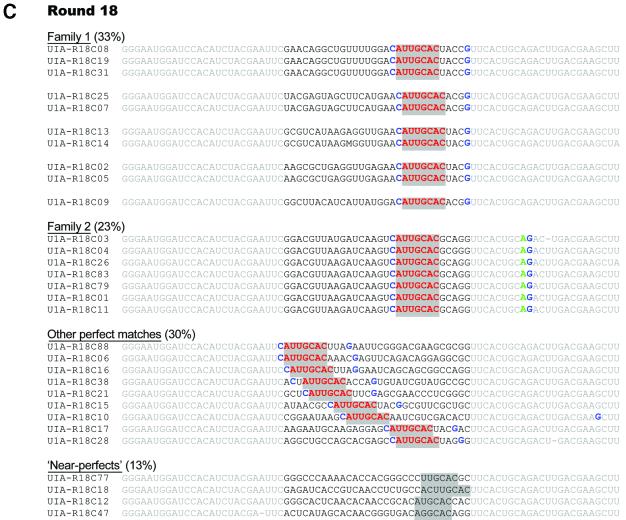

Aptamers from rounds 6, 12 and 18 were cloned and sequenced (Fig. 7). Aptamer sequences that contained the canonical heptamer were seen at the sixth round of selection: 8% (1 of 12 clones) contained a perfect match to the heptamer, while 42% (5 of 12 clones) had imperfect matches to this sequence (Fig. 7A). After another six rounds of selection the sequence diversity of the pool was further reduced and most individuals (79%, 11 of 14 clones) possessed the heptamer or near perfect matches (14%, 2 of 14 clones; Fig. 7B). Further selection with increasing stringency yielded a pool where 87% of sequences (26 of 30 clones) contained the heptamer and the remaining 13% (4 of 30 clones) had near perfect matches (Fig. 7C). No sequences lacked perfect or near perfect matches in the final pool.

Figure 7.

(Following page) Sequences of anti-U1A aptamers. Sequences of selected clones from (A) round 6, (B) round 12 and (C) round 18 are shown. The static (priming) regions are shaded light gray, while the randomized region is in black text. Perfect matches to the U1A snRNA heptamer are highlighted in gray and bold red; near perfect heptamer sequences are highlighted in gray. In (C), the C:G base pair that closes the U1 snRNA hairpin II loop (Family 1) and that precedes Box II of the 3′-UTR U1 mRNA (Family 2) is shown in blue. The adenosine found in the internal loop region of the 3′-UTR U1 mRNA (Family 2) is shown in green.

Based on similar sequences found outside of the conserved heptamer, anti-U1A aptamers could be clustered into two sequence families. Family 1 makes up 33% of the final pool, and can be further subdivided into five clonal sub-families, all with the consensus sequence UGRACAUUGCACUACG. Family 2 comprises 23% of the final population of the pool and is largely clonal.

Predictions of the secondary structures of individual aptamers are consistent with the hypothesis that Family 1 mimics the wild-type U1 snRNA hairpin II, while Family 2 is instead structurally similar to the 3′-UTR of U1A mRNA (Fig. 6C and D). It should be noted that aptamers that are not in Family 1 or Family 2 may still generally resemble the wild-type ligands. For example, many of the aptamers listed as ‘other perfect matches’ (Fig. 7C) can readily be folded to form hairpin II-like structures.

Interestingly, all residues that have previously been shown by structural or functional analyses to be important for hydrophobic, stacking or hydrogen bonding interactions were conserved in the selected aptamers. Conversely, residues that are known to not be important for interactions with U1A were not conserved. The degree to which features of natural ligands have been recapitulated by in vitro selection is remarkable. A C:G base pair closes the loop in the wild-type U1 snRNA hairpin and has been shown to be crucial for binding an arginine residue in U1A. Disruption of this base pair and this interaction eliminates U1 snRNA binding to U1A (9,41). All aptamers in Family 1 are predicted to form a typical stem–loop structure closed by the requisite C:G base pair. Conversely, the remaining base pairs in the stem interact non-specifically with positively charged residues in U1A (12,33,39). Because of this the identity of the base pairs in the stem have been found to be irrelevant to U1A binding and, in fact, no particular base pairs predominate in the predicted stem structures of the Family 1 aptamers. Similarly, the last three residues (UCC) of the 10 residue hairpin loop of the wild-type U1 snRNA do not physically interact with the protein (12). Family 1 aptamers all have three or four dissimilar (non-conserved) residues in these same positions. The variability in overall loop length was expected, given that it has previously been shown that the insertion of a single residue into the loop has little effect on protein binding (35). Conversely, no loops shorter than 10 residues were seen. In this regard, it has previously been shown that a nine residue loop lacking one of the three otherwise non-conserved residues has 1000-fold less affinity for U1A. The removal of another residue decreases binding an additional 10-fold, while the creation of a seven residue loop ultimately decreases the Kd by 100 000-fold (35).

In the wild-type 3′-UTR the canonical AUUGCAC and loop-closing C:G base pair again form hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic interactions with U1A (33,34) and, as stated before, Family 2 aptamers retain all critical sequence and structural features. In addition, in the 3′-UTR a single adenosine residue (A24) on the opposite side of the internal loop has been shown to form essential hydrogen bonding and stacking interactions with serine, valine and arginine residues in U1A (33,34). Aptamers in Family 2 can in fact be folded so as to present a single adenosine residue opposite the conserved heptamer.

The wild-type RNA ligands of the U1A protein are known to bind with high affinity (Kd values of 10–11–10–8 M, depending on pH and monovalent and divalent salt concentrations) (35). Under our assay conditions, the minimized, 21 nt wild-type U1 snRNA hairpin II structure forms a complex with U1A with a Kd of 11 nM. Most aptamers were found to have Kd values in the low nanomolar range (Table 3). Family 1 aptamers, those most akin to hairpin II, have Kd values as low as 4.5 nM. Interestingly, at least one member of Family 1, clone 09, has a much higher Kd value (69 nM). This aptamer is also predicted to form a hairpin-like structure, just as the other family members are. The fact that its Kd deviates significantly suggests that subtle changes in the presentation of the heptamer motif can be extremely important for binding. Family 2 aptamers bind U1A slightly worse than Family 1, with the majority aptamer forming a complex with a Kd of 17 nM. As expected, sequences with ‘near perfect’ motifs bound much less well than sequences that conformed to the natural ligands.

Table 3. Dissociation constants of complexes formed with selected sequences.

Numbers under families are clone numbers from round 18. Binding assays were performed in triplicate to determine standard deviations.

The selection of the natural binding sequences was not completely unexpected. A previous manual selection had been performed against the U1A protein by Tsai et al. (8). The authors carried out selection experiments starting from three randomized pools. The first two pools contained the wild-type U1 snRNA stem structure topped by a randomized loop region of 10 or 13 nt. The third pool contained 25 randomized nt flanked by primer sequences, similar to our N30 pool. Both the constrained and unconstrained pools generated aptamers containing the canonical heptamer sequence. How ever, the aptamers generated from the third pool by these manual selection procedures exhibited poor binding to U1A protein in gel shift experiments (100-fold less affinity than with wild-type ligand). In keeping with this observation, the manually selected aptamers did not mimic the wild-type sequences as well as those generated by automated selection; for example, they did not contain the C:G base pair closing the U1 snRNA loop. Similarly, none of the aptamers selected from the unconstrained pool was predicted to fold into either U1 snRNA-like or U1A 3′-UTR mRNA-like structures. While additional rounds of manual selection might of course have improved the selected populations, these would have been prohibitively tedious. The fact that multiple rounds of automated selection can be carried out within days allows the sequences, structures and affinities of aptamers to be finely tuned.

Prospects for automated selection with in vitro generated protein targets

Overall, the results presented here illustrate a strategy for the generation of multiple aptamers against a large number of protein targets and for the acquisition of sequence and structural data relating to RNA–protein interactions. Based on the throughputs available with automated selection, the generation of aptamers against the translation products of all genes within an average bacterial genome could be completed within a course of months. Many of the selected aptamers would of course be useful as reagents alone, for example for labeling or detecting (1–3) key proteins or even the expression profile of the entire proteome. Nonetheless, the generality of these methods for multiple different classes of proteins remains to be seen.

Our results also confirm that it may be possible to use in vitro selection to decipher specific interactions between multiple different nucleic acid-binding proteins and their corresponding cellular RNA sequences. In vitro selection has previously been used to identify or define a variety of natural nucleic acid-binding sequences (42). For example, an in vitro selection experiment that targeted the E.coli methionine repressor generated DNA aptamers that contained an octamer sequence found in natural DNA-binding sites (43). Likewise, in vitro RNA selection experiments have generated aptamers to T4 DNA polymerase that both recreate a natural binding element and generate a new element that possesses the same Kd as the wild-type (44). Similar findings have been observed during selections against phage MS2 coat protein, phage R17 coat protein and the E.coli special elongation factor SelB (45–47).

From this vantage, it is interesting to note that our selection produced two aptamer families that closely corresponded to the two natural RNA-binding elements of U1A. The fact that the natural sequences and structures were extracted from a completely random sequence library is remarkable and has additional important implications for the specificity of interactions between U1A and its natural targets. One measure of specificity is what set of sequences a given protein will preferentially recognize. In the case of U1A, the natural ligands are apparently globally optimal, at least within the context of a sequence space of roughly 30 residues. Indeed, the U1A protein can even finely distinguish between ligands that superficially resemble one another in terms of critical sequences and structures, since different Family 1 members can have Kd values that vary by an order of magnitude. These results imply both that the U1A protein has structured its RNA-binding domain in such a way that it can reject sequences and structures that are not exactly like the natural ligands, and that the natural ligands have been derived by a search of a sequence space that is much larger than the size of the genomes in which they are ensconced. This is one of the first examples of natural optimality in a sequence space of this size.

While other methods for ascertaining natural nucleic acid-binding sequences are also possible, including genomic SELEX (48–50), in which libraries are generated directly from natural sequences, the use of randomized libraries also allows the identification of unnatural sequences that may have improved affinities and greater utility as laboratory reagents. For example, in vitro selection against the Rev protein of HIV-1 yielded aptamers that were similar to the wild-type Rev-binding element (RBE), but bound to Rev 10 times better (51). In the current instance, despite the fact that the natural RNA sequences have been exquisitely optimized by natural selection, automated selection has apparently improved on wild-type affinities by a factor of approximately 2.4 (4.5 versus 11 nM).

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Dr David Waugh (NCI–Frederick) for the gift of pDW363. This work was funded by grants from the Beckman Foundation, Robert A. Welch Foundation (F-1393), Army Research Office, (MURI DAAD19-99-1-0207) and NIH-Rev (AI36083-09).

REFERENCES

- 1.Jayasena S.D. (1999) Aptamers: an emerging class of molecules that rival antibodies in diagnostics. Clin. Chem., 45, 1628–1650. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rajendran M. and Ellington,A.D. (2002) Selecting nucleic acids for biosensor applications. Comb. Chem. High Throughput Screen., 5, 263–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wilson D.S. and Szostak,J.W. (1999) In vitro selection of functional nucleic acids. Annu. Rev. Biochem., 68, 611–647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cox J.C., Rajendran,M., Riedel,T., Davidson,E.A., Sooter,L.J., Bayer,T.S., Schmitz-Brown,M. and Ellington,A.D. (2002) Automated acquisition of aptamer sequences. Comb. Chem. High Throughput Screen., 5, 289–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cox J.C., Rudolph,P. and Ellington,A.D. (1998) Automated RNA selection. Biotechnol. Prog., 14, 845–850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cox J.C. and Ellington,A.D. (2001) Automated selection of anti-protein aptamers. Bioorg. Med. Chem., 9, 2525–2531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blackwell T.K. and Weintraub,H. (1990) Differences and similarities in DNA-binding preferences of MyoD and E2A protein complexes revealed by binding site selection. Science, 250, 1104–1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tsai D.E., Harper,D.S. and Keene,J.D. (1991) U1-snRNP-A protein selects a ten nucleotide consensus sequence from a degenerate RNA pool presented in various structural contexts. Nucleic Acids Res., 19, 4931–4936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jessen T.H., Oubridge,C., Teo,C.H., Pritchard,C. and Nagai,K. (1991) Identification of molecular contacts between the U1 A small nuclear ribonucleoprotein and U1 RNA. EMBO J., 10, 3447–3456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hall K.B. (1994) Interaction of RNA hairpins with the human U1A N-terminal RNA binding domain. Biochemistry, 33, 10076–10088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stemmer W.P., Crameri,A., Ha,K.D., Brennan,T.M. and Heyneker,H.L. (1995) Single-step assembly of a gene and entire plasmid from large numbers of oligodeoxyribonucleotides. Gene, 164, 49–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oubridge C., Ito,N., Evans,P.R., Teo,C.H. and Nagai,K. (1994) Crystal structure at 1.92 Å resolution of the RNA-binding domain of the U1A spliceosomal protein complexed with an RNA hairpin. Nature, 372, 432–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Horton R.M., Hunt,H.D., Ho,S.N., Pullen,J.K. and Pease,L.R. (1989) Engineering hybrid genes without the use of restriction enzymes: gene splicing by overlap extension. Gene, 77, 61–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mertens N., Remaut,E. and Fiers,W. (1996) Increased stability of phage T7g10 mRNA is mediated by either a 5′- or a 3′-terminal stem-loop structure. Biol. Chem., 377, 811–817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Olins P.O., Devine,C.S., Rangwala,S.H. and Kavka,K.S. (1988) The T7 phage gene 10 leader RNA, a ribosome-binding site that dramatically enhances the expression of foreign genes in Escherichia coli. Gene, 73, 227–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schatz P.J. (1993) Use of peptide libraries to map the substrate specificity of a peptide-modifying enzyme: a 13 residue consensus peptide specifies biotinylation in Escherichia coli. Biotechnology, 11, 1138–1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tsao K.L., DeBarbieri,B., Michel,H. and Waugh,D.S. (1996) A versatile plasmid expression vector for the production of biotinylated proteins by site-specific, enzymatic modification in Escherichia coli. Gene, 169, 59–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sambrook J. and Russell,D.W. (2001) Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual, 3rd Edn. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 19.Laemmli U.K. (1970) Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature, 227, 680–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hayhurst A. and Harris,W.J. (1999) Escherichia coli skp chaperone coexpression improves solubility and phage display of single-chain antibody fragments. Protein Expr. Purif., 15, 336–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bell S.D., Denu,J.M., Dixon,J.E. and Ellington,A.D. (1998) RNA molecules that bind to and inhibit the active site of a tyrosine phosphatase. J. Biol. Chem., 273, 14309–14314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Clackson T.D., Güssow,D. and Jones,P.T. (1991) Characterizing recombinant clones directly by PCR screening. In Rickwood,D. and Hames,B.D. (eds), PCR 1. Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK, pp. 210–212.

- 23.Mathews D.H., Sabina,J., Zuker,M. and Turner,D.H. (1999) Expanded sequence dependence of thermodynamic parameters improves prediction of RNA secondary structure. J. Mol. Biol., 288, 911–940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ellington A.D. (1997) Preparation and analysis of DNA. In Ausubel,F., Brent,R., Kingston,R.E., Moore,D.D., Seidman,J.G., Smith,J.A. and Struhl,K. (eds), Short Protocols in Molecular Biology, 3rd Edn. John Wiley & Sons, New York, NY, pp. 2-43–2-44.

- 25.Jhaveri S.D. and Ellington,A.D. (2000) Combinatorial methods in nucleic acid chemistry. In Beaucage,S.L., Bergstrom,D.E., Glick,G.D. and Jones,R.A. (eds), Current Protocols in Nucleic Acid Chemistry. John Wiley & Sons, New York, NY, pp. 9.3.1–9.3.25.

- 26.Chapman-Smith A. and Cronan,J.E.,Jr (1999) The enzymatic biotinylation of proteins: a post-translational modification of exceptional specificity. Trends Biochem. Sci., 24, 359–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saviranta P., Haavisto,T., Rappu,P., Karp,M. and Lovgren,T. (1998) In vitro enzymatic biotinylation of recombinant fab fragments through a peptide acceptor tail. Bioconjug. Chem., 9, 725–735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cull M.G. and Schatz,P.J. (2000) Biotinylation of proteins in vivo and in vitro using small peptide tags. Methods Enzymol., 326, 430–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McAllister H.C. and Coon,M.J. (1966) Further studies on the properties of liver propionyl coenzyme A holocarboxylase synthetase and the specificity of holocarboxylase formation. J. Biol. Chem., 241, 2855–2861. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.De Guzman R.N., Turner,R.B. and Summers,M.F. (1998) Protein-RNA recognition. Biopolymers, 48, 181–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Scherly D., Boelens,W., van Venrooij,W.J., Dathan,N.A., Hamm,J. and Mattaj,I.W. (1989) Identification of the RNA binding segment of human U1 A protein and definition of its binding site on U1 snRNA. EMBO J., 8, 4163–4170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Binkley J., Allen,P., Brown,D.M., Green,L., Tuerk,C. and Gold,L. (1995) RNA ligands to human nerve growth factor. Nucleic Acids Res., 23, 3198–3205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Allain F.H., Howe,P.W., Neuhaus,D. and Varani,G. (1997) Structural basis of the RNA-binding specificity of human U1A protein. EMBO J., 16, 5764–5772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Allain F.H., Gubser,C.C., Howe,P.W., Nagai,K., Neuhaus,D. and Varani,G. (1996) Specificity of ribonucleoprotein interaction determined by RNA folding during complex formulation. Nature, 380, 646–650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Williams D.J. and Hall,K.B. (1996) RNA hairpins with non-nucleotide spacers bind efficiently to the human U1A protein. J. Mol. Biol., 257, 265–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Katsamba P.S., Myszka,D.G. and Laird-Offringa,I.A. (2001) Two functionally distinct steps mediate high affinity binding of U1A protein to U1 hairpin II RNA. J. Biol. Chem., 276, 21476–21481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Boelens W.C., Jansen,E.J., van Venrooij,W.J., Stripecke,R., Mattaj,I.W. and Gunderson,S.I. (1993) The human U1 snRNP-specific U1A protein inhibits polyadenylation of its own pre-mRNA. Cell, 72, 881–892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.van Gelder C.W., Gunderson,S.I., Jansen,E.J., Boelens,W.C., Polycarpou-Schwarz,M., Mattaj,I.W. and van Venrooij,W.J. (1993) A complex secondary structure in U1A pre-mRNA that binds two molecules of U1A protein is required for regulation of polyadenylation. EMBO J., 12, 5191–5200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nagai K., Oubridge,C., Ito,N., Avis,J. and Evans,P. (1995) The RNP domain: a sequence-specific RNA-binding domain involved in processing and transport of RNA. Trends Biochem. Sci., 20, 235–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jovine L., Oubridge,C., Avis,J.M. and Nagai,K. (1996) Two structurally different RNA molecules are bound by the spliceosomal protein U1A using the same recognition strategy. Structure, 4, 621–631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nagai K., Oubridge,C., Jessen,T.H., Li,J. and Evans,P.R. (1990) Crystal structure of the RNA-binding domain of the U1 small nuclear ribonucleoprotein A. Nature, 348, 515–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Conrad R.C., Symensma,T.L. and Ellington,A.D. (1997) Natural and unnatural answers to evolutionary questions. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 94, 7126–7128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.He Y.Y., Stockley,P.G. and Gold,L. (1996) In vitro evolution of the DNA binding sites of Escherichia coli methionine repressor, MetJ. J. Mol. Biol., 255, 55–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tuerk C. and Gold,L. (1990) Systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment: RNA ligands to bacteriophage T4 DNA polymerase. Science, 249, 505–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Xu W. and Ellington,A.D. (1996) Anti-peptide aptamers recognize amino acid sequence and bind a protein epitope. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 93, 7475–7480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schneider D., Tuerk,C. and Gold,L. (1992) Selection of high affinity RNA ligands to the bacteriophage R17 coat protein. J. Mol. Biol., 228, 862–869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hirao I., Spingola,M., Peabody,D. and Ellington,A.D. (1998) The limits of specificity: an experimental analysis with RNA aptamers to MS2 coat protein variants. Mol. Divers., 4, 75–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shtatland T., Gill,S.C., Javornik,B.E., Johansson,H.E., Singer,B.S., Uhlenbeck,O.C., Zichi,D.A. and Gold,L. (2000) Interactions of Escherichia coli RNA with bacteriophage MS2 coat protein: genomic SELEX. Nucleic Acids Res., 28, e93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Singer B.S., Shtatland,T., Brown,D. and Gold,L. (1997) Libraries for genomic SELEX. Nucleic Acids Res., 25, 781–786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gold L., Brown,D., He,Y., Shtatland,T., Singer,B.S. and Wu,Y. (1997) From oligonucleotide shapes to genomic SELEX: novel biological regulatory loops. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 94, 59–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Giver L., Bartel,D., Zapp,M., Pawul,A., Green,M. and Ellington,A.D. (1993) Selective optimization of the Rev-binding element of HIV-1. Nucleic Acids Res., 21, 5509–5516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]