Abstract

Progress in the study of the molecular mechanisms that regulate neuronal differentiation has been quite impressive in recent years, and promises to continue to an equally fast pace. This should not lead us into a sense of complacency, however, because there are still significant barriers that cannot be overcome by simply conducting the same type of experiments that we have been performing thus far. This article will describe some of these challenges, while highlighting the conceptual and methodological breakthroughs that will be necessary to overcome them.

Keywords: cell commitment, combinatorial gene effects, gain-of-function, loss-of-function, neuronal markers, extracellular signals

I. INTRODUCTION

It is very difficult to avoid superlatives when describing recent progress in the study of the molecular mechanisms regulating cell differentiation in the nervous system in general, and in the retina in particular (reviewed by Jean et al., 1998; Adler, 2000, Lupo et al., 2000; Galli-Resta, 2001; Livesey and Cepko, 2001, Vetter and Brown, 2001; Marquardt and Gruss, 2002; Zhang et al., 2002a; Boulton and Albon, 2004; Hatakeyama and Kageyama, 2004, Malicki, 2004; Mu and Klein 2004). There can be little doubt, moreover, that this field will continue to advance at an extremely fast pace. Its remarkable success and bright future should not distract us, however, from recognizing and addressing the important challenges that still lie ahead of us, and particularly those that are unlikely to be solved without the development of new methodologies. The goal of this article is not to provide a comprehensive review of the literature but, rather, to describe some of these challenges using examples from studies of retinal cell differentiation, with which the author's laboratory has direct experience. Studies in invertebrates, although relevant and important (rev, Frankfort and Mardon, 2002; Wernet and Desplan, 2004; Yang 2004; Mollereau and Domingos, 2005) will not be covered due to space limitations. Most of the issues that will be considered, however, are equally relevant to studies of neuronal differentiation in other regions of the vertebrate nervous system.

II. INVESTIGATING CELL COMMITTMENT

A) Operational definition of cell commitment

At early stages of embryonic development, the neural retina consists of a population of morphologically homogeneous and mitotically active neuroepithelial cells. Early neuroepithelial cells have been shown to be multipotential, i.e., to retain the capacity to give rise to two or more types of differentiated retinal cells (Holt et al., 1988; Wetts and Fraser, 1988; Cepko, 1993; Harris, 1997). Considerable (and increasing) heterogeneity arises within the retina as neuroepithelial cells become postmitotic and begin their migration towards their future position in one of the retinal layers. This process continues for a period of days to weeks, depending on the species, with extensive overlap in the generation of different cell types (Barnstable et al., 1988; Rapaport et al., 1996; Harris, 1997; Adler, 2000; Mey and Thanos, 2000; Malicki, 2004; Rapaport et al., 2004). The differentiation of the cells thus generated also starts, and advances to various degrees, during this period. Cells undergoing proliferation, terminal mitosis (“cell birth”), migration and differentiation overlap with each other in time and space. As discussed below, the heterogeneous and dynamic nature of the embryonic populations thus generated creates many challenges for the design of experiments aimed at investigating the molecular regulation of these developmental mechanisms.

It is generally accepted that, at some stage during its developmental history, each multipotential progenitor becomes “committed” to a specific differentiated fate. Cell commitment still is defined operationally, through experiments in which the microenvironment of the cells is altered by pharmacological treatments and/or by cell and tissue transplantation, recombination, or culture. Multipotential progenitors are defined as those that change their differentiated fate in response to changes in their microenvironment, whereas committed progenitors are those that always follow the same developmental pathway, regardless of their microenvironment. These issues have been investigated in different laboratories with a variety of approaches, which have been the subject of excellent recent reviews (Cepko et al., 1996; Reh and Levine, 1998; Fuhrmann et al., 2000; Levine et al., 2000; Perron and Harris, 2000b; Perron and Harris, 2000a; Cepko, 2001; Layer et al., 2001; Livesey and Cepko, 2001; Zhang et al., 2002b; Martinez-Morales et al., 2004). It would be beyond the scope of this article to provide an additional comprehensive overview of this literature; rather, our own experience using a cell culture approach will be used to illustrate the limits of phenomenological, operational definitions of cell commitment.

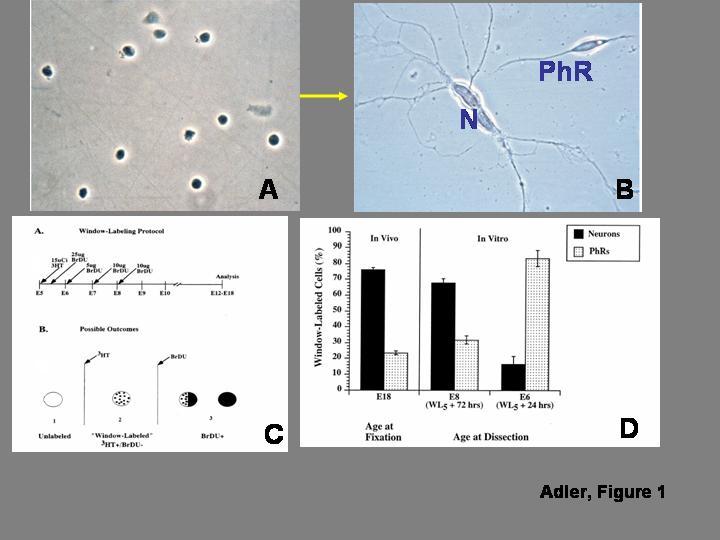

An example of a cell culture experiment testing cell commitment is illustrated in Figure 1. In this case, cells dissociated from the chick embryo retina before the onset of overt differentiation were grown in low density culture, in the absence of contact-mediated intercellular interactions. The goal of the experiment was to test whether, in this homogeneous but artificial microenvironment, the undifferentiated cells would: i) differentiate, ii) follow divergent developmental pathway(s), and iii) express phenotypic properties similar to those of cells that differentiate within the retina in vivo. Panel A illustrates the morphological homogeneity observed at culture onset. As shown in panel B, many of the cells did indeed differentiate after several days in vitro, and did follow divergent developmental pathways as photoreceptors or non-photoreceptor (predominantly amacrine) neurons (Adler et al., 1984). The cells that differentiated as photoreceptors were analyzed in more detail, and were found to express a very complex phenotype, which resembled in many respects the phenotypes of photoreceptors that develop in vivo, while differing significantly from the phenotype of amacrine neurons developing within the same culture microenvironment (rev: Adler, 2000). Taken together, the data suggested that some progenitor cells were committed to a photoreceptor fate, and others to a non-photoreceptor neuronal fate.

FIGURE 1.

. In vitro analysis of progenitor cell “commitment”. A) Morphologically homogeneous population of progenitor cells isolated from the chick embryo retina before the onset of overt differentiation. The cells are grown at low density, to minimize contact-mediated cell interactions. B) After several days in culture, some of the progenitor cells differentiate as photoreceptors (PhR), while others differentiate as non-photoreceptor, predominantly amacrine neurons (N). C) Diagrammatic summary of the window-labeling technique, which allows identifying cells that undergo terminal mitosis during narrowly defined periods of time. As shown in the top panel, the technique involves the sequential administration of tritiated thymidine (3HT) followed 5 hr later by an initial injection of bromodeoxyuridine (BrDU), which is repeated at daily intervals. As shown in the bottom panel, cells that are already postmitotic at the time of 3HT injection appear unlabeled, and cells that divide once or several times after BrDU administration are BrDU(+); the only cells that are 3HT(+)/BrDU(-) are those that are in S-phase during the 5 hr time interval between 3HT and BrDU administration, and became postmitotic immediately thereafter. D) Analysis of the fate of cells born during a 5 hr interval on embryonic day 5 (WL5). When the cells are allowed to develop in vivo until embryonic day 18, nearly 75% of the cells differentiate as non-photoreceptor neurons, and only 25% differentiate as photoreceptors. Similar results are seen when the cells are isolated for culture on embryonic day 8, after 72 hr of exposure to the retinal microenvironment. On the other hand, when the WL5 cells are exposed to the in vivo microenvironment for only 24 hr before isolation, they give rise predominantly to photoreceptors. As discussed in the text, the experiments indicate that the cells remain plastic after their terminal mitosis. Panels A and B from Madreperla and Adler (1989); panels B and C from Belecky-Adams et al. (1996), reprinted with permission from Elsevier, Inc.

This same experimental paradigm was used, with some modifications, to investigate whether progenitor cells become committed to a photoreceptor or non-photoreceptor fate before or after their terminal mitosis. Given that the highly heterogeneous embryonic retina contains mixtures of cells born at different times during a period of several days (see above), it was necessary to identify cells born during narrow time intervals. This was accomplished with a method known as the “window-labeling” technique, shown in Fig. 1C, which is based on the sequential administration of 3H-thymidine and BrDU (Repka and Adler, 1992; Belecky-Adams et al., 1996). The study was thus focused on a cohort of cells born during a 5-hour interval on ED 5 (“WL5” cells), and is summarized in Fig. 1D. In vivo, as assessed on ED 18, 75% of the WL5 cells became non-photoreceptor neurons, and only 25% gave rise to photoreceptors (Belecky-Adams et al., 1996). When WL5 cells were isolated for culture on ED 8 (i.e., after remaining within the retinal environment for approximately 3 days after their terminal mitosis), they mimicked their in vivo behavior, giving rise to similar neuron/photoreceptor ratios. The developmental fate of the WL5 cells, however, was quite different when they were isolated from the retina on ED 6, after a shorter exposure to the retinal microenvironment. In this case, 80% of the WL5 cells gave rise to photoreceptors, and only 20% became non-photoreceptor neurons (Belecky-Adams et al., 1996). Control experiments indicated that differences in cell proliferation or cell death could not explain these striking differences in cell fate, which therefore appeared to indicate a real change in the developmental potential of WL5 cells during the interval between ED 6 and ED 8. This change, in turn, implied that many precursor cells remained plastic (i.e., uncommitted to specific differentiated fates) for some time after their terminal mitosis.

B) From operational definitions to a molecular description of cell commitment.

Operational tests of cell commitment such as those summarized above have been very instructive, but share two very important limitations. First, they evaluate cell commitment retrospectively given that, by the time the developmental fate of progenitor cells has been experimentally assessed, they do not exist as progenitors any longer. Secondly, they provide information at the population, rather than at the single cell level; these experiments, in other words, can show that a population contains progenitors committed to different fates, but do so without identifying the cells committed to each fate. The interpretation of such experiments is further complicated by the heterogeneity of cell populations in the developing central nervous system (CNS), including the retina (Section II-A). For example, if a treatment increases the frequency of ganglion cells and decreases the frequency of photoreceptors that differentiate in a culture of retinal cells, the result could be due to the induction of uncommitted precursors to differentiate as ganglion cells rather than as photoreceptors, and/or to increased survival of ganglion cells, and/or to increased death of photoreceptors, and/or to increased proliferation of progenitors destined to become ganglion cells, and/or to decreased proliferation of progenitors destined to become photoreceptors. There are now a variety of methods for the quantitative assessment of cell death or cell proliferation in vivo or in vitro, but they do not always allow distinguishing between these different scenarios. A main reason for this limitation is the lack of accurate criteria for the identification of sub-populations of undifferentiated but otherwise “committed” progenitor cells (see below).

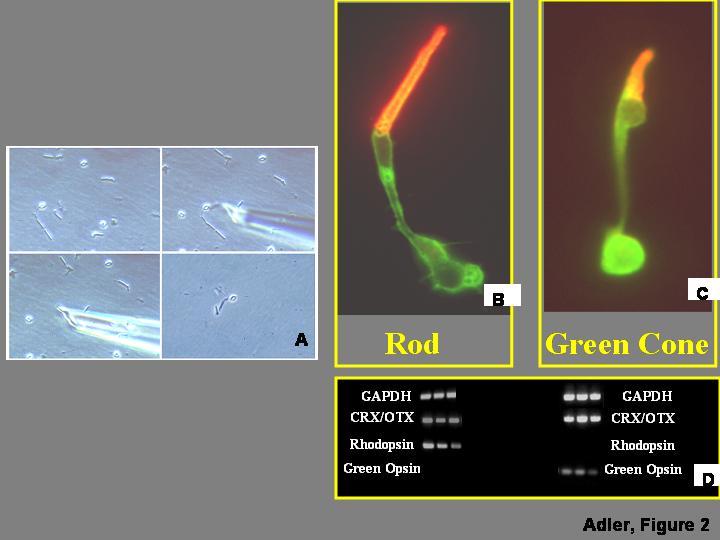

Further progress in the analysis of cell differentiation in the retina (as in other CNS regions) appears to require the development of methods that would allow evaluating the commitment of individual cells, prospectively, and at the molecular level. An important step in this direction has been the development of methods that allow the amplification of RNA from individual cells either linearly (Eberwine et al., 2001) or exponentially (Brady and Iscove, 1993; Dulac, 1998; Brady, 2000). These methods have found increasing applications for the analysis of differentiated cells (ibid), including retinal cells (Wahlin et al., 2004), but have not yet found similar applications in the case of undifferentiated progenitor cells. Differentiated chick embryo rod and cone photoreceptors, for example, can be identified by morphological criteria and captured individually after the retina is dissociated (Fig. 2A; their identity can be verified with immunocytochemical methods, as well as by PCR amplification of cell-specific gene products (Fig. 2B-D). Methods such as suppression subtractive hybridization make it possible to identify genes, including transcription factors, that are differentially expressed in individual rod or cone photoreceptors (Huang and Adler, 2005). Could techniques of this type be used to compare, at the molecular level, multipotential and “committed” progenitor cells? Unfortunately, such comparisons are currently not feasible, because subpopulations of progenitor cells cannot be distinguished morphologically (Fig. 1A), and suitable molecular “markers” are not yet available for their characterization. This limitation creates quite a conundrum: multipotential and committed progenitors would have to be identified in order to be isolated for molecular analysis, but they cannot be identified without information about their molecular composition, which does not currently exist.

Figure 2.

. Analysis of gene expression in isolated retinal cells. A) Retinas are dissociated and individual cells captured as described by Wahlin et al. (2004). B,C) Rod and cone photoreceptor cells isolated from chick embryo retinas can be identified by morphological criteria, verified by immunocytochemistry with antibodies against the visual pigments expressed in each cell type. Individual cells can be processed for cDNA synthesis and exponential amplification using protocols described by Brady and Iscove (1993), and Dulac (1998). D) The identity of the cells can be further investigated by PCR amplification of housekeeping genes (e.g., GAPDH), general photoreceptor markers (e.g., CRX/OTX), and visual pigments which are selectively expressed in individual photoreceptor types (e.g., rhodopsin in rods, green opsin in green cones).

Alternatives to capturing individual cells can be considered, which could theoretically allow the isolation of homogeneous populations of progenitor cells, (e.g., fluorescence-activated cell sorting, FACS; Maric and Barker, 2004), or their generation by clonal cultures derived from individual stem or progenitor cells (Tropepe et al., 2000; Seaberg and van der Kooy, 2002; Irvin et al., 2003). Such methods, however, are not devoid of limitations. FACS, for example, depends on the availability of molecular “markers” for the cells to be sorted which, as discussed above, have yet to be identified for multipotential and committed neural progenitors. Similarly, the assumption that clonal cultures are homogeneous has been challenged by recent studies showing that, despite their origin, a high degree of heterogeneity develops spontaneously in the cultures (e.g., Tropepe et al., 2000; Maric and Barker, 2004). It appears, therefore, that the development of suitable methods and reagents for the objective identification and molecular characterization of progenitor cells remains a major and critical challenge for developmental neurobiology.

III. DISSECTING THE COMPLEXITY OF INTRACELLULAR SIGNALING SYSTEMS THROUGH GAIN- AND LOSS-OF-FUNCTION APPROACHES

A) The power of gain- and loss-of-function methods

A major contributor to the explosive rate of progress in developmental neurobiology during the last several years has been the introduction of powerful techniques and reagents for gain- and loss-of-function experiments, such as gene transfection, viral vectors, electroporation, transgenic and inducible transgenic animals, dominant-negative and constitutively activated molecular constructs, knockouts and conditional knockouts, morpholinos, RNAi, and random and targeted mutagenesis. These gain- and loss-of-function approaches have generated (and undoubtedly will continue to generate) many valuable insights into molecular aspects of neural development. At the same time, however, their use has also shed light on some of their own limitations, which should foster efforts to develop complementary (but qualitatively different) approaches.

B) The challenge of investigating combinatorial gene effects

The origin of retinal cells has been experimentally traced as far back in development as to individual blastomeres (e.g., Huang and Moody, 1993). During this long developmental history, progenitor cells and their descendants undergo many sequential transitions before becoming mature, differentiated cells. Gain- and loss-of-function studies have led to two significant generalizations regarding these transitions: 1) most if not all of these developmental phenomena are regulated or otherwise influenced by several different extracellular signaling molecules and intracellular transcription factors, and 2) many signaling molecules and transcription factors participate in the regulation of two or more developmental transitions, exerting different (even opposite) effects in each case. The homeobox gene Pax6, for example, is necessary for the determination of the retinal anlage and for the initial establishment of a pigment epithelial domain and a neural retinal domain within the optic vesicle (Macdonald et al., 1995; Schedl et al., 1996; Oliver and Gruss, 1997; Mathers and Jamrich, 2000; Schwarz et al., 2000, Marquardt et al., 2001; Ziman et al., 2001; Toy et al., 2002). Cell differentiation within the neural retina is also influenced by Pax6 at somewhat later stages, but its effects are quite different in different cell types. Thus, Pax6 expression appears necessary for the differentiation of ganglion and amacrine neurons (Marquardt et al., 2001, Toy et al., 2002), but its overexpression into progenitor cells inhibits their differentiation as photoreceptors (Belecky-Adams et al., 1997; Toy et al., 2002). These and many similar observations in other tissues have shown that the functions of transcription factors depend on the molecular context in which they act (rev., Silver and Rebay, 2005). Although a single transcription factor can have by itself a profound effect on cell fate, as illustrated by the transformation of rods into blue cones in the NRL knockout mouse (Mears et al., 2001), even a “master gene” such as Pax6 can only induce the formation of an ectopic eye when it is expressed under the appropriate conditions (Chow et al., 1999; Gehring and Ikeo, 1999).

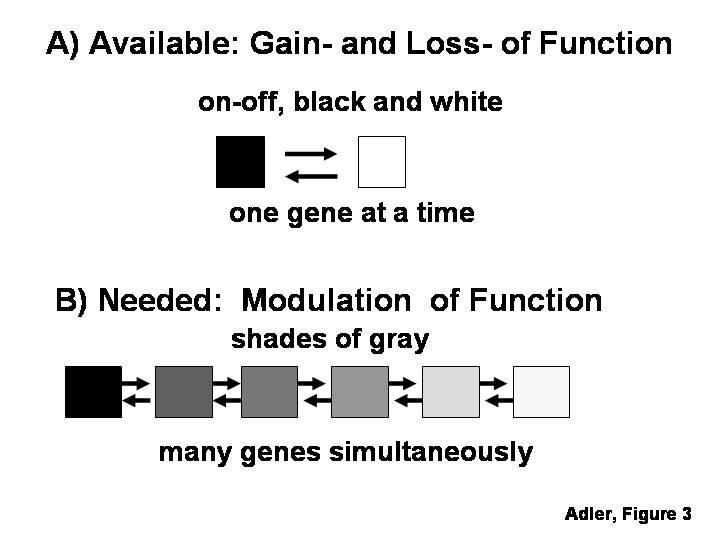

A major breakthrough in the investigation of combinatorial gene effects of this type was the introduction of microarray technology, which allows comparing the levels of expression of thousands of genes in two RNA samples. This powerful methodology has provided much useful information about the retina (Zareparsi et al., 2004), and can be applied not only to tissue extracts, but also to single cells (e.g., Brady, 2000; Goto et al., 2001; Chiang and Melton, 2003). The wealth of data that can be obtained using microarray technology could have been expected to allow the elucidation of combinatorial gene effects in the regulation of cell differentiation. As recently noted, however, microarray technology has so far had only a modest impact on our understanding of developmental mechanisms (Livesey, 2003; Smith and Greenfield, 2003). Rather than an intrinsic problem of microarray technology, this limited impact is likely to reflect, to a very large degree, a drawback shared by currently available methods for gain- and loss-of function experiments: these methods only allow targeting one or two genes at a time, and do so in an all-or-none (“black-or-white”) manner (Fig. 3). Therefore, while microarray data allow formulating hypotheses about regulatory networks involving the combinatorial effects of a series of genes expressed at particular levels, these hypotheses are likely to remain untested until methods allowing the modulation of the levels of expression of groups of genes become available (Fig. 3) .

Figure 3.

A) There are now many methods for gain- and loss-of function experiments, which allow targeting only one or two genes at a time, and do so in a “black-or-white”, all-or-none manner. B) These methods appear insufficient for the analysis of combinatorial mechanisms regulating cell differentiation, which would require methods for modulating the level of expression of groups of genes.

IV. THE ROLE OF EXTRACELLULAR SIGNALS IN THE REGULATION OF NEURONAL DIFFERENTIATION

Impressive progress has been made in recent years in the analysis of the role of extracellular signaling molecules in the regulation of neuronal differentiation. Emphasis has been placed predominantly on studies of individual signaling molecules, largely because secreted signaling molecules were initially considered highly cell type-specific. In turn, this concept was strongly influenced by the “neurotrophic hypothesis”, derived from studies of developmental neuronal death and the nerve growth factor, NGF (Davies, 1996; Yuen et al., 1996). Methodologically, the studies were also influenced by the increasing availability of purified signaling molecules, and of well characterized neuronal cultures that provided suitable bioassays for their analysis. Many factors active on particular types of neurons were identified in this fashion. In the case of embryonic photoreceptor cells, for example, the list includes CNTF (Kirsch et al., 1996; Ezzeddine et al., 1997; Fuhrmann et al., 1998; Kirsch et al., 1998; Ogilvie et al., 2000; Xie and Adler, 2000), FGF (Hicks and Courtois, 1992; Fontaine et al., 1998), SHH (Levine et al., 1997), LIF (Neophytou et al., 1997), retinoic acid (Stenkamp et al., 1993; Kelley et al., 1994; Kelley et al., 1995; Hyatt et al., 1996; Kelley et al., 1999; Wallace and Jensen, 1999; Soderpalm et al., 2000), thyroid hormone (Kelley et al., 1995; Yanagi et al., 2002), GDNF (Politi et al., 2001) PEDF (Jablonski et al., 2000), docosahexaenoic acid (Rotstein et al., 1998; Politi et al., 2001), taurine (Altshuler et al., 1993; Wallace and Jensen, 1999; Young and Cepko, 2004), and activin (Belecky-Adams et al., 1999).

There is now growing awareness that the microenvironmental regulation of neuronal differentiation is likely to be much more complex than once thought. It has become well established, for example, that mono-specific signaling molecules are likely to be an exception, rather than the rule (rev: Patterson, 1994; Snider, 1994; Davies, 1996; Levi-Montalcini et al., 1996; Merrill and Benveniste, 1996; Carter and Lewin, 1997; Murphy et al., 1997; Tolkovsky, 1997; Adler et al., 1999). Signaling molecules of this type generally appear to be quite pleiotropic, triggering different responses on different cells through a variety of receptors and transduction pathways (e.g., Goumans and Mummery, 2000; Rajan et al., 2003; Waite and Eng, 2003, Storkebaum et al, 2004; Velde and Cleveland, 2005). There is also a fairly extensive body of literature showing that signaling molecules are modulated by interactions with each other and with extracellular binding proteins, and that they can exert combinatorial, complementary and/or redundant effects on cells (e.g., Ip and Yancopoulos, 1996; Phillips, 2000; Butte, 2001; Balemans and Van Hul, 2002; Abe et al., 2004; Harrison, et al., 2004; Rosenstein and Krum, 2004; Sebald et al., 2004; Vergara and Ramirez, 2004). The interactive and pleiotropic nature of signaling molecules is particularly significant in view of the abundance and diversity of such molecules in the retina (e.g., Campochiaro, 1996; Hallbook et al., 1996; Schoen and Chader, 1997; Hicks, 1998, Belecky-Adams et al, 1999; Frade et al, 1999; Belecky-Adams and Adler, 2001; Carri, 2003; Yang, 2004). Retinal cell differentiation, moreover, can be influenced not only by secreted molecules but also by contact-mediated interactions (Linser and Moscona et al., 1984; Moscona et al., 1988; Hausman et al., 1993; Henrique et al., 1997; Layer et al., 1998; Prada et al., 1998; Becker and Mobbs, 1999). Not surprisingly, therefore, a picture of high complexity has emerged since the development of techniques and reagents for loss- and gain-of-function experiments made it possible to investigate the role of extracellular signals not only in cell culture, but also within the complexity of the intact embryo. For example, very similar changes in the development of the ventral retina and pigment epithelium can be induced by overexpressing sonic hedgehog (SHH; Nasrallah and Golden, 2001; Zhang and Yang, 2001) and by blocking BMP signaling with noggin or dominant-negative BMP receptors (Adler and Belecky-Adams, 2002). It appears likely that SHH acts upstream from BMP in those effects (Zhang and Yang, 2001). Some of the phenotypic abnormalities triggered by noggin overexpression, moreover, were likely mediated and/or modulated by other signaling molecules, including retinoic acid, netrin, R-cadherin, laminin and FGF-8 (Adler and Belecky-Adams, 2002). These and similar observations (e.g., Hunter et al., 2004; Martinez-Morales et al., 2005, Murali et al., 2005) suggest that the microenvironment in which retinal cells differentiate is a highly homeostatic system, in which complex changes are likely to result from experimental manipulation of an individual signaling molecule. Therefore, while analytical approaches based on perturbations of individual factors will undoubtedly continue to provide important and useful information, it may be necessary to develop new strategies and approaches in order to generate a more integrated description of the microenvironmental influences that regulate neuronal differentiation.

V. CHARACTERIZATION OF DIFFERENTIATED PHENOTYPES

A) Contributions of “cell markers” to the study of neuronal cell differentiation

Cell differentiation research owes much of its recent progress to methods such as in situ hybridization and immunocytochemistry, which allow comparing the expression of particular genes in different cell types within heterogeneous tissues. The power of these methods has led to widespread use of “cell markers”, that is to say, molecules whose expression in a cell is considered unambiguous proof of the cell's identity and differentiated state. There is now growing evidence, however, that cell markers are not devoid of potential pitfalls, some of which will be discussed below.

B) The specificity of neuronal markers is frequently not absolute

Some ”markers” are restricted to a single cell type early in development, but become more broadly distributed at later stages. An example is the transcription factor islet1, once considered ganglion cell-specific throughout chick retinal development (Austin et al., 1995). Based on this premise, increases in islet1-positive cells resulting from Notch down-regulation were interpreted to represent a specific increase in ganglion cell differentiation (ibid). This interpretation must be revisited, however, because islet1 has now been shown to be ganglion cell- specific only at early stages of chick embryo development and to be subsequently expressed by other differentiating neurons (Henrique et al., 1997). There are also examples of the opposite type of change in patterns of “cell marker” expression, since molecules restricted to specific cell types in the mature retina sometimes have broader distribution at earlier stages; this temporal pattern has been reported for several transcription factors (e.g., Freund et al., 1996; Belecky-Adams et al., 1997; Oliver and Gruss, 1997; Mathers and Jamrich, 2000). An additional layer of complexity is that undifferentiated cells not only can express differentiated cell markers, but can also express markers corresponding to more than one lineage; multilineage gene expression, for example, has been reported to occur before cell commitment in the hematopoietic system (Hu et al., 1997). It has also been proposed that transcription of individual genes during cell differentiation may well occur in the “wrong cells”, as a probabilistic event (Paldi, 2003). Against this background, it appears reasonable to reconsider whether a “marker” normally restricted to a particular cell type in the mature retina, when detected in a newly generated cell, should be considered an unambiguous indication of its commitment to that lineage. This has been suggested to be the case, for example, for chick embryo progenitors that, shortly after terminal mitosis, express a cytoskeletal protein recognized by the monoclonal antibody RA4, a ganglion cell “marker” (McLoon and Barnes, 1989; Waid and McLoon, 1995).

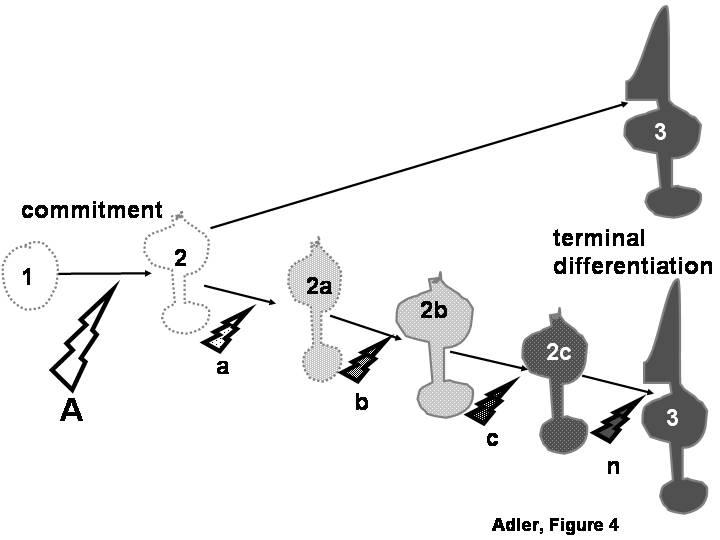

The use of molecules expressed during terminal differentiation as markers of progenitor cell commitment would only be justified in cases in which the entire process of cell differentiation is controlled cell-autonomously by intrinsic mechanisms set in motion at the time of progenitor cell commitment to a particular lineage (Fig. 4). On the other hand, the approach would not be warranted if sequential inductive events are necessary before a committed progenitor can reach terminal differentiation (Fig. 4). A distinction between these two scenarios has been difficult for many cell types, but photoreceptor cells have been amenable to their investigation because their differentiation can be analyzed with many structural, molecular and functional criteria. An initial indication of the existence of different regulatory mechanisms for different aspects of photoreceptor differentiation was the observation, made in several laboratories, that there is considerable asynchrony in the onset of expression of photoreceptor-specific genes (Bruhn and Cepko, 1996; Stenkamp et al., 1997; Johnson et al., 2001; Bradford et al, 2005). Some of those genes are already expressed at, or shortly after the time of photoreceptor birth, preceding by many days other important landmarks in photoreceptor differentiation, such as the formation of outer segments (Saha and Grainger, 1993; Bruhn and Cepko, 1996; Stenkamp et al., 1997; Johnson et al., 2001, Bradford et al., 2005). The spatial patterns of expression of these early genes suggest that they are controlled by intracellular determinants, rather than by diffusible signals (Johnson et al., 2001). Cell-autonomous mechanisms also appear to control other “early” aspects of photoreceptor differentiation in the chick embryo (Adler, 2000; see Section II) as well as in other species (Cook and Desplan, 2001).

Figure 4.

Molecules that are first expressed during the terminal differentiation of a cell type (cell # 3) are frequently used as “markers” to evaluate the inductive signals (A) through which an undifferentiated progenitor cell (cell # 1) becomes committed to a particular differentiated lineage (cell # 2). Such use would only be justified if the entire process of cell differentiation is controlled cell-autonomously by intrinsic mechanisms set in motion at the time of progenitor cell commitment (top pathway). On the other hand, the approach would not be warranted if additional inductive signals (bottom pathway, a, b, c, n) re necessary for a committed progenitor to reach terminal differentiation through a series of intermediate stages (2a, 2b, 2c).

Many other aspects of photoreceptor differentiation occur much later in development, and appear to be regulated by different mechanisms. There are many genes, for example, that only become detectable many days, or even several weeks after photoreceptors are born. The onset of expression of these late genes correlates approximately with the onset of outer segment formation (Bruhn and Cepko, 1996; Cepko, 1996; Bumsted et al., 1997; Johnson et al., 2001; Bradford et al., 2005). Although the mechanisms responsible for this prolonged lag between photoreceptor birth and terminal differentiation remain unknown, this temporal difference between early and late genes provides circumstantial evidence against the notion that photoreceptor-specific genes could be globally co-regulated. We recently tested this issue more directly, using in situ hybridization, RT-PCR and real time PCR to investigate the expression of eighteen photoreceptor-specific genes in retinal cells treated with agents previously reported to modulate the expression of specific visual pigments (Bradford et al., 2005). These agents are activin, which inhibits the expression of the red cone pigment, iodopsin (Belecky-Adams et al., 1999), CNTF, which upregulates the expression of the green cone pigment (Xie and Adler, 2000), and staurosporine, which induces rhodopsin expression and down-regulates expression of the red cone pigment (Xie and Adler, 2000). Rhodopsin, for example, is not detectable in control cultures, even by RT-PCR, but becomes readily detectable by in situ hybridization in 80% of the photoreceptors in staurosporine-treated cultures. Importantly, this strong inductive effect is not accompanied by detectable changes in other rod-specific genes. Similarly, a variety of cone genes remains unchanged when the red and green cone pigment genes are inhibited by staurosporine, and/or when the green cone pigment gene is upregulated by CNTF treatment (Bradford et al., 2005). These cell culture experiments, therefore, provide additional evidence for the independent regulation of different photoreceptor-specific genes.

A key issue in evaluating the expression of cell markers in the face of perturbation is how to determine whether altered marker expression reflects cell fate, rather than a change in regulation of the marker. For example, the apparent differences between regulatory mechanisms controlling early and late aspects of photoreceptor differentiation, together with the lack of coordinated regulation of many photoreceptor-specific genes, raise some concerns about the use of molecules expressed during terminal differentiation (a late event) as indicators of the commitment of retinal progenitor cells to the photoreceptor lineage (a much earlier event). Controversies regarding the specific role of signaling molecules in the control of photoreceptor development may perhaps be explained by such use. Increases in rhodopsin immunoreactive cells in rat retinal cultures treated with 9-cis retinoic acid, for example, were initially interpreted to represent increases in progenitor cell commitment to the photoreceptor fate (Kelley et al., 1994). However, subsequent studies found no evidence of a fate switch, and showed that retinoic acid acts by shortening the maximum time between terminal mitosis and detectable rhodopsin expression (Wallace and Jensen, 1999). Similarly, while there is consensus that CNTF causes a decrease in the number of rhodopsin(+) cells in rat retinal cultures, the effects have been interpreted as a re-specification of cells destined to become rods (Ezzeddine et al., 1997), arrested differentiation of cells already committed to the rod fate (Neophytou et al., 1997), or a transient and reversible down-regulation of rhodopsin expression (Schulz-Key et al., 2002). The ambiguity between cell fate determination and modulation of the expression of markers of terminal differentiation also remains unresolved for other factors that regulate photoreceptor development, such as taurine (Altshuler et al., 1993), ligands of steroid/thyroid receptors (Kelley et al., 1995), and sonic hedgehog (Levine et al., 1997). It appears, in summary, that molecules expressed during terminal differentiation are not suitable indicators of progenitor cell commitment to the photoreceptor fate; whether similar limitations apply to other neuronal types remains an open question, which deserves to be investigated.

VI) CONCLUDING REMARKS

The impressive body of information on mechanisms of neuronal differentiation that has been generated so far provides a solid foundation for future studies, many of which will continue to make use of currently available methods and approaches. Equally necessary for further progress, however, is our awareness of the gaps that still exist in our present knowledge, of the questions that remain to be answered, and of the limitations of the methods and approaches currently available for their investigation. Overcoming these limitations will not be easy, but the effort is likely to have a broad impact because, although they have been discussed in this article within the narrow confines of neuronal differentiation in the retina, they are similarly relevant to cell differentiation studies in other parts of the nervous system, and even in non-neural tissues.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The author is grateful to Valeria Canto Soler and Karl Wahlin for comments and suggestions on the article, and to Betty Bandell for secretarial assistance. Research in the author's laboratory was supported by grants from the National Eye Institute and the Foundation Fighting Blindness. RA is the Arnall Patz Distinguished Professor, and a Senior Investigator of Research to Prevent Blindness, Inc.

Footnotes

Supported by: National Eye Institute: EY14341, EY04859, and a core grant P30EY1765; Foundation Fighting Blindness; Research to Prevent Blindness: Senior Investigator Award, and an unrestricted departmental grant

REFERENCES

- Abe Y, Minegishi T, Leung PC. Activin receptor signaling. Growth Factors. 2004;22:105–110. doi: 10.1080/08977190410001704688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adler R. A model of retinal cell differentiation in the chick embryo. Prog Ret Eye Res. 2000;20:529–557. doi: 10.1016/s1350-9462(00)00008-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adler R, Belecky-Adams TL. The role of bone morphogenetic proteins in the differentiation of the ventral optic cup. Development. 2002;129:3161–3171. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.13.3161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adler R, Curcio C, Hicks D, Price D, Wong F. Cell death in age-related macular degeneration. Mol Vis. 1999;5:31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adler R, Lindsey JD, Elsner CL. Expression of cone-like properties by chick embryo neural retina cells in glial-free monolayer cultures. J Cell Biol. 1984;99:1173–1178. doi: 10.1083/jcb.99.3.1173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altshuler D, Lo Turco JJ, Rush J, Cepko C. Taurine promotes the differentiation of a vertebrate retinal cell type in vitro. Development. 1993;119:1317–1328. doi: 10.1242/dev.119.4.1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austin CP, Feldman DE, Ida JA, Jr., Cepko CL. Vertebrate retinal ganglion cells are selected from competent progenitors by the action of Notch. Development. 1995;121:3637–3650. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.11.3637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balemans W, Van Hul W. Extracellular regulation of BMP signaling in vertebrates: a cocktail of modulators. Dev Biol. 2002;250:231–250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnstable CJ, Blum AS, Devoto SH, Hicks D, Morabito MA, Sparrow JR, Treisman JE. Cell differentiation and pattern formation in the developing mammalian retina. Neurosci Res Suppl. 1988;8:S27–41. doi: 10.1016/0921-8696(88)90005-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker DL, Mobbs P. Connexin alpha1 and cell proliferation in the developing chick retina. Exp Neurol. 1999;156:326–332. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1999.7027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belecky-Adams T, Adler R. Developmental expression patterns of bone morphogenetic proteins, receptors, and binding proteins in the chick retina. J Comp Neurol. 2001;430:562–572. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belecky-Adams T, Cook B, Adler R. Correlations between terminal mitosis and differentiated fate of retinal precursor cells in vivo and in vitro: analysis with the “window-labeling” technique. Dev. Biol. 1996;178:304–315. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1996.0220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belecky-Adams T, Tomarev S, Li HS, Ploder L, McInnes RR, Sundin O, Adler R. Pax-6, Prox 1, and Chx10 homeobox gene expression correlates with phenotypic fate of retinal precursor cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1997;38:1293–1303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belecky-Adams TL, Scheurer D, Adler R. Activin family members in the developing chick retina: expression patterns, protein distribution, and in vitro effects. Dev Biol. 1999;210:107–123. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1999.9268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulton M, Albon J. Stem cells in the eye. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2004;36:643–657. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2003.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford RL, Wang C, Zack DJ, Adler R.Roles of cell-intrinsic and microenvironmental factors in photoreceptor cell differentiation 2005. Submitted [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady G. Expression profiling of single mammalian cells--small is beautiful. Yeast. 2000;17:211–217. doi: 10.1002/1097-0061(20000930)17:3<211::AID-YEA26>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady G, Iscove NN. Construction of cDNA libraries from single cells. Methods Enzymol. 1993;225:611–623. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(93)25039-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruhn SL, Cepko CL. Development of the pattern of photoreceptors in the chick retina. J Neurosci. 1996;16:1430–1439. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-04-01430.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bumsted K, Jasoni C, Szel A, Hendrickson A. Spatial and temporal expression of cone opsins during monkey retinal development. J Comp Neurol. 1997;378:117–134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butte MJ. Neurotrophic factor structures reveal clues to evolution, binding, specificity, and receptor activation. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2001;58:1003–1013. doi: 10.1007/PL00000915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campochiaro PA, Hackett SF, Vinores SA. Growth factors in the retina and retinal pigmented epithelium. Prog Ret Eye Res. 1996;15:547–567. [Google Scholar]

- Carri NG. Multiple neurotrophic signalling: certain TGF molecules are involved in retinal development and maturation, but do they complement one another's actions? Cell Biol Int. 2003;27:1033–1036. doi: 10.1016/j.cellbi.2003.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter BD, Lewin GR. Neurotrophins live or let die: does p75NTR decide? Neuron. 1997;18:187–190. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80259-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cepko C. Lineage versus environment in the embryonic retina. Trends Neurosci. 1993;16:96–97. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(93)90131-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cepko CL. The patterning and onset of opsin expression in vertebrate retinae. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1996;6:542–546. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(96)80062-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cepko CL. Genomics approaches to photoreceptor development and disease. Harvey Lect. 2001;97:85–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cepko CL, Austin CP, Yang X, Alexiades M, Ezzeddine D. Cell fate determination in the vertebrate retina. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:589–595. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.2.589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang MK, Melton DA. Single-cell transcript analysis of pancreas development. Dev Cell. 2003;4:383–393. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00035-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chow RL, Altmann CR, Lang RA, Hemmati-Brivanlou A. Pax6 induces ectopic eyes in a vertebrate. Development. 1999;126:4213–4222. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.19.4213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook T, Desplan C. Photoreceptor subtype specification: from flies to humans. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2001;12:509–518. doi: 10.1006/scdb.2001.0275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies AM. The neurotrophic hypothesis: where does it stand? Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1996;351:389–394. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1996.0033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dulac C. Cloning of genes from single neurons. Curr Top Dev Biol. 1998;36:245–258. doi: 10.1016/s0070-2153(08)60506-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eberwine J, Kacharmina JE, Andrews C, Miyashiro K, McIntosh T, Becker K, Barrett T, Hinkle D, Dent G, Marciano P. mRNA expression analysis of tissue sections and single cells. J Neurosci. 2001;21:8310–8314. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-21-08310.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezzeddine ZD, Yang X, DeChiara T, Yancopoulos G, Cepko CL. Postmitotic cells fated to become rod photoreceptors can be respecified by CNTF treatment of the retina. Development. 1997;124:1055–1067. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.5.1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontaine V, Kinkl N, Sahel J, Dreyfus H, Hicks D. Survival of purified rat photoreceptors in vitro is stimulated directly by fibroblast growth factor-2. J Neurosci. 1998;18:9662–9672. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-23-09662.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frade JM, Bovolenta P, Rodriguez-Tebar A. Neurotrophins and other growth factors in the generation of retinal neurons. Microsc Res Tech. 1999;45:243–251. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0029(19990515/01)45:4/5<243::AID-JEMT8>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frankfort BJ, Mardon G. R8 development in the Drosophila eye: a paradigm for neural selection and differentiation. Development. 2002;129:1295–1306. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.6.1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freund C, Horsford DJ, McInnes RR. Transcription factor genes and the developing eye: a genetic perspective. Hum Mol Genet. 1996;5:1471–1488. doi: 10.1093/hmg/5.supplement_1.1471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuhrmann S, Chow L, Reh TA. Molecular control of cell diversification in the vertebrate retina. Results Probl Cell Differ. 2000;31:69–91. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-46826-4_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuhrmann S, Heller S, Rohrer H, Hofmann HD. A transient role for ciliary neurotrophic factor in chick photoreceptor development. J Neurobiol. 1998;37:672–683. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4695(199812)37:4<672::aid-neu14>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galli-Resta L. Assembling the vertebrate retina: global patterning from short-range cellular interactions. Neuroreport. 2001;12:A103–106. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200112040-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gehring WJ, Ikeo K. Pax 6: mastering eye morphogenesis and eye evolution. Trends Genet. 1999;15:371–377. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(99)01776-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goto T, Holding C, Daniels R, Salpekar A, Monk M. Gene expression studies on human primordial germ cells and preimplantation embryos. Ital J Anat Embryol. 2001;106:119–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goumans MJ, Mummery C. Functional analysis of the TGFbeta receptor/Smad pathway through gene ablation in mice. Int J Dev Biol. 2000;44:253–265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallbook F, Backstrom A, Kullander K, Ebendal T, Carri NG. Expression of neurotrophins and trk receptors in the avian retina. J Comp Neurol. 1996;364:664–676. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19960122)364:4<664::AID-CNE5>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris WA. Cellular diversification in the vertebrate retina. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1997;7:651–658. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(97)80013-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison CA, Wiater E, Gray PC, Greenwald J, Choe S, Vale W. Modulation of activin and BMP signaling. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2004;225:19–24. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2004.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatakeyama J, Kageyama R. Retinal cell fate determination and bHLH factors. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2004;15:83–89. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2003.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hausman RE, Rao AS, Ren Y, Sagar GD, Shah BH. Retina cognin, cell signaling, and neuronal differentiation in the developing retina. Dev Dyn. 1993;196:263–266. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001960407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henrique D, Hirsinger E, Adam J, Le Roux I, Pourquie O, Ish-Horowicz D, Lewis J. Maintenance of neuroepithelial progenitor cells by Delta-Notch signalling in the embryonic chick retina. Curr Biol. 1997;7:661–770. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(06)00293-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hicks D. Putative functions of fibroblast growth factors in retinal development, maturation and survival. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 1998;9:263–269. doi: 10.1006/scdb.1998.0230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hicks D, Courtois Y. Fibroblast growth factor stimulates photoreceptor differentiation in vitro. J Neurosci. 1992;12:2022–2033. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-06-02022.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt CE, Bertsch TW, Ellis HM, Harris WA. Cellular determination in the Xenopus retina is independent of lineage and birth date. Neuron. 1988;1:15–26. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(88)90205-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu M, Krause D, Greaves M, Sharkis S, Dexter M, Heyworth C, Enver T. Multilineage gene expression precedes commitment in the hemopoietic system. Genes Dev. 1997;11:774–785. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.6.774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang H, Adler R.Cone- and rod-specific transcriptional regulators identified by single cell cDNA suppression subtractive hybridization 2005. ARVO Abstract [Google Scholar]

- Huang S, Moody SA. The retinal fate of Xenopus cleavage stage progenitors is dependent upon blastomere position and competence: studies of normal and regulated clones. J Neurosci. 1993;13:3193–3210. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-08-03193.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter DD, Zhang M, Ferguson JW, Koch M, Brunken WJ. The extracellular matrix component WIF-1 is expressed during, and can modulate, retinal development. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2004;27:477–488. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2004.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyatt GA, Schmitt EA, Fadool JM, Dowling JE. Retinoic acid alters photoreceptor development in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:13298–13303. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.23.13298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ip NY, Yancopoulos GD. The neurotrophins and CNTF: two families of collaborative neurotrophic factors. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1996;19:491–515. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.19.030196.002423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irvin DK, Dhaka A, Hicks C, Weinmaster G, Kornblum HI. Extrinsic and intrinsic factors governing cell fate in cortical progenitor cultures. Dev Neurosci. 2003;25:162–172. doi: 10.1159/000072265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jablonski MM, Tombran-Tink J, Mrazek DA, Iannaccone A. Pigment epithelium-derived factor supports normal development of photoreceptor neurons and opsin expression after retinal pigment epithelium removal. J Neurosci. 2000;20:7149–7157. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-19-07149.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jean D, Ewan K, Gruss P. Molecular regulators involved in vertebrate eye development. Mech Dev. 1998;76:3–18. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(98)00117-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson PT, Williams RR, Reese BE. Developmental patterns of protein expression in photoreceptors implicate distinct environmental versus cell-intrinsic mechanisms. Vis Neurosci. 2001;18:157–168. doi: 10.1017/s0952523801181150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley MW, Turner JK, Reh TA. Retinoic acid promotes differentiation of photoreceptors in vitro. Development. 1994;120:2091–2102. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.8.2091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley MW, Turner JK, Reh TA. Ligands of steroid/thyroid receptors induce cone photoreceptors in vertebrate retina. Development. 1995;121:3777–3785. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.11.3777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley MW, Williams RC, Turner JK, Creech-Kraft JM, Reh TA. Retinoic acid promotes rod photoreceptor differentiation in rat retina in vivo. Neuroreport. 1999;10:2389–2394. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199908020-00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirsch M, Fuhrmann S, Wiese A, Hofmann HD. CNTF exerts opposite effects on in vitro development of rat and chick photoreceptors. Neuroreport. 1996;7:697–700. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199602290-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirsch M, Schulz-Key S, Wiese A, Fuhrmann S, Hofmann H. Ciliary neurotrophic factor blocks rod photoreceptor differentiation from postmitotic precursor cells in vitro. Cell Tissue Res. 1998;291:207–216. doi: 10.1007/s004410050991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Layer PG, Rothermel A, Willbold E. Inductive effects of the retinal pigmented epithelium (RPE) on histogenesis of the avian retina as revealed by retinospheroid technology. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 1998;9:257–262. doi: 10.1006/scdb.1998.0234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Layer PG, Rothermel A, Willbold E. From stem cells towards neural layers: a lesson from re-aggregated embryonic retinal cells. Neuroreport. 2001;12:A39–46. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200105250-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levi-Montalcini R, Skaper SD, Dal Toso R, Petrelli L, Leon A. Nerve growth factor: from neurotrophin to neurokine. Trends Neurosci. 1996;19:514–520. doi: 10.1016/S0166-2236(96)10058-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine EM, Fuhrmann S, Reh TA. Soluble factors and the development of rod photoreceptors. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2000;57:224–234. doi: 10.1007/PL00000686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine EM, Roelink H, Turner J, Reh TA. Sonic hedgehog promotes rod photoreceptor differentiation in mammalian retinal cells in vitro. J Neurosci. 1997;17:6277–6288. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-16-06277.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linser PJ, Moscona AA. The influence of neuronal-glial interactions on glia-specific gene expression in embryonic retina. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1984;181:185–202. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4684-4868-9_15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livesey FJ. Strategies for microarray analysis of limiting amounts of RNA. Brief Funct Genomic Proteomic. 2003;2:31–36. doi: 10.1093/bfgp/2.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livesey FJ, Cepko CL. Vertebrate neural cell-fate determination: Lessons from the retina. Nature Rev Neurosci. 2001;2:109–118. doi: 10.1038/35053522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lupo G, Andreazzoli M, Gestri G, Liu Y, He RQ, Barsacchi G. Homeobox genes in the genetic control of eye development. Int J Dev Biol. 2000;44:627–636. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macdonald R, Barth KA, Xu Q, Holder N, Mikkola I, Wilson SW. Midline signalling is required for Pax gene regulation and patterning of the eyes. Development. 1995;121:3267–3278. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.10.3267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madreperla SA, Adler R. Opposing microtubule- and actin-dependent forces in the development and maintenance of structural polarity in retinal photoreceptors. Dev Biol. 1989;131:149–160. doi: 10.1016/s0012-1606(89)80046-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malicki J. Cell fate decisions and patterning in the vertebrate retina: the importance of timing, asymmetry, polarity and waves. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2004;14:15–21. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2004.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maric D, Barker JL. Neural stem cells redefined: a FACS perspective. Mol Neurobiol. 2004;30:49–76. doi: 10.1385/MN:30:1:049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marquardt T, Ashery-Padan R, Andrejewski N, Scardigli R, Guillemot F, Gruss P. Pax6 is required for the multipotent state of retinal progenitor cells. Cell. 2001;105:43–55. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00295-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marquardt T, Gruss P. Generating neuronal diversity in the retina: one for nearly all. Trends Neurosci. 2002;25:32–38. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(00)02028-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Morales JR, Del Bene F, Nica G, Hammerschmidt M, Bovolenta P, Wittbrodt J. Differentiation of the vertebrate retina Is coordinated by an FGF signaling center. Dev Cell. 2005;8:565–574. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Morales JR, Rodrigo I, Bovolenta P. Eye development: a view from the retina pigmented epithelium. Bioessays. 2004;26:766–777. doi: 10.1002/bies.20064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathers PH, Jamrich M. Regulation of eye formation by the Rx and Pax6 homeobox genes. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2000;57:186–194. doi: 10.1007/PL00000683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLoon SC, Barnes RB. Early differentiation of retinal ganglion cells: an axonal protein expressed by premigratory and migrating retinal ganglion cells. J Neurosci. 1989;9:1424–1432. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.09-04-01424.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mears AJ, Kondo M, Swain PK, Takada Y, Bush RA, Saunders TL, Sieving PA, Swaroop A. Nrl is required for rod photoreceptor development. Nat Genet. 2001;29:447–452. doi: 10.1038/ng774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrill JE, Benveniste EN. Cytokines in inflammatory brain lesions: helpful and harmful. Trends Neurosci. 1996;19:331–338. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(96)10047-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mey J, Thanos S. Development of the visual system of the chick. I. Cell differentiation and histogenesis. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2000;32:343–379. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(99)00022-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mollereau B, Domingos PM. Photoreceptor differentiation in Drosophila: from immature neurons to functional photoreceptors. Dev Dyn. 2005;232:585–592. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moscona AA, Moscona M, Degenstein L. Embryonic cell recognition: uncoupling tissue-specific affinities from cell-type specificities. Cell Differ Dev. 1988;25:185–196. doi: 10.1016/0922-3371(88)90115-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mu X, Klein WH. A gene regulatory hierarchy for retinal ganglion cell specification and differentiation. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2004;15:115–123. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2003.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murali D, Yoshikawa S, Corrigan RR, Plas DJ, Crair MC, Oliver G, Lyons KM, Mishina Y, Furuta Y. Distinct developmental programs require different levels of Bmp signaling during mouse retinal development. Development. 2005;132:913–923. doi: 10.1242/dev.01673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy M, Dutton R, Koblar S, Cheema S, Bartlett P. Cytokines which signal through the LIF receptor and their actions in the nervous system. Prog Neurobiol. 1997;52:355–378. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(97)00020-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasrallah I, Golden JA. Brain, eye, and face defects as a result of ectopic localization of Sonic hedgehog protein in the developing rostral neural tube. Teratology. 2001;64:107–113. doi: 10.1002/tera.1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neophytou C, Vernallis AB, Smith A, Raff MC. Muller-cell-derived leukaemia inhibitory factor arrests rod photoreceptor differentiation at a postmitotic pre-rod stage of development. Development. 1997;124:2345–2354. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.12.2345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogilvie JM, Speck JD, Lett JM. Growth factors in combination, but not individually, rescue rd mouse photoreceptors in organ culture. Exp Neurol. 2000;161:676–685. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1999.7291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver G, Gruss P. Current views on eye development. Trends Neurosci. 1997;20:415–421. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(97)01082-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paldi A. Stochastic gene expression during cell differentiation: order from disorder? Cell Mol Life Sci. 2003;60:1775–1778. doi: 10.1007/s00018-003-23147-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson PH.Leukemia inhibitory factor, a cytokine at the interface between neurobiology and immunology Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1994917833–7835.comment [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perron M, Harris WA. Determination of vertebrate retinal progenitor cell fate by the Notch pathway and basic helix-loop-helix transcription factors. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2000a;57:215–223. doi: 10.1007/PL00000685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perron M, Harris WA. Retinal stem cells in vertebrates. Bioessays. 2000b;22:685–688. doi: 10.1002/1521-1878(200008)22:8<685::AID-BIES1>3.0.CO;2-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips DJ. Regulation of activin's access to the cell: why is mother nature such a control freak? Bioessays. 2000;22:689–696. doi: 10.1002/1521-1878(200008)22:8<689::AID-BIES2>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Politi LE, Rotstein NP, Carri NG. Effect of GDNF on neuroblast proliferation and photoreceptor survival: additive protection with docosahexaenoic acid. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2001;42:3008–3015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prada FA, Quesada A, Dorado ME, Chmielewski C, Prada C. Glutamine synthetase (GS) activity and spatial and temporal patterns of GS expression in the developing chick retina: relationship with synaptogenesis in the outer plexiform layer. Glia. 1998;22:221–236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajan P, Panchision DM, Newell LF, McKay RD. BMPs signal alternately through a SMAD or FRAP-STAT pathway to regulate fate choice in CNS stem cells. J Cell Biol. 2003;161:911–921. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200211021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapaport DH, Rakic P, LaVail MM. Spatiotemporal gradients of cell genesis in the primate retina. Perspect Dev Neurobiol. 1996;3:147–159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapaport DH, Wong LL, Wood ED, Yasumura D, LaVail MM. Timing and topography of cell genesis in the rat retina. J Comp Neurol. 2004;474:304–324. doi: 10.1002/cne.20134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reh TA, Levine EM. Multipotential stem cells and progenitors in the vertebrate retina. J Neurobiol. 1998;36:206–220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Repka AM, Adler R. Accurate determination of the time of cell birth using a sequential labeling technique with [3H]-thymidine and bromodeoxyuridine (“window labeling”) J Histochem Cytochem. 1992;40:947–953. doi: 10.1177/40.7.1607643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenstein JM, Krum JM. New roles for VEGF in nervous tissue--beyond blood vessels. Exp Neurol. 2004;187:246–253. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2004.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotstein NP, Politi LE, Aveldano MI. Docosahexaenoic acid promotes differentiation of developing photoreceptors in culture. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1998;39:2750–2758. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saha MS, Grainger RM. Early opsin expression in Xenopus embryos precedes photoreceptor differentiation. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1993;17:307–318. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(93)90016-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schedl A, Ross A, Lee M, Engelkamp D, Rashbass P, van Heyningen V, Hastie ND. Influence of PAX6 gene dosage on development: overexpression causes severe eye abnormalities. Cell. 1996;86:71–82. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80078-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoen TJ, Chader J. Insulin-like growth factors and their blinding proteins in the developing eye. Prog Retin Eye Res. 1997;16:479–507. [Google Scholar]

- Schulz-Key S, Hofmann HD, Beisenherz-Huss C, Barbisch C, Kirsch M. Ciliary neurotrophic factor as a transient negative regulator of rod development in rat retina. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002;43:3099–3108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz M, Cecconi F, Bernier G, Andrejewski N, Kammandel B, Wagner M, Gruss P. Spatial specification of mammalian eye territories by reciprocal transcriptional repression of Pax2 and Pax6. Development. 2000;127:4325–4334. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.20.4325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seaberg RM, van der Kooy D. Adult rodent neurogenic regions: the ventricular subependyma contains neural stem cells, but the dentate gyrus contains restricted progenitors. J Neurosci. 2002;22:1784–1793. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-05-01784.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sebald W, Nickel J, Zhang JL, Mueller TD. Molecular recognition in bone morphogenetic protein (BMP)/receptor interaction. Biol Chem. 2004;385:697–710. doi: 10.1515/BC.2004.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silver SJ, Rebay I. Signaling circuitries in development: insights from the retinal determination gene network. Development. 2005;132:3–13. doi: 10.1242/dev.01539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith L, Greenfield A.DNA microarrays and development Hum Mol Genet 200312R1–8.Spec No 1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snider WD. Functions of the neurotrophins during nervous system development: what the knockouts are teaching us. Cell. 1994;77:627–638. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90048-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soderpalm AK, Fox DA, Karlsson JO, van Veen T. Retinoic acid produces rod photoreceptor selective apoptosis in developing mammalian retina. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000;41:937–947. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stenkamp DL, Barthel LK, Raymond PA. Spatiotemporal coordination of rod and cone photoreceptor differentiation in goldfish retina. J Comp Neurol. 1997;382:272–284. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19970602)382:2<272::aid-cne10>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stenkamp DL, Gregory JK, Adler R. Retinoid effects in purified cultures of chick embryo retina neurons and photoreceptors. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1993;34:2425–2436. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storkebaum E, Lambrechts D, Carmeliet P. VEGF: once regarded as a specific angiogenic factor, now implicated in neuroprotection. Bioessays. 2004;26:943–954. doi: 10.1002/bies.20092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolkovsky A. Neurotrophic factors in action--new dogs and new tricks. Trends Neurosci. 1997;20:1–3. doi: 10.1016/S0166-2236(96)30017-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toy J, Norton JS, Jibodh SR, Adler R. Effects of homeobox genes on the differentiation of photoreceptor and nonphotoreceptor neurons. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002;43:3522–3529. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tropepe V, Coles BL, Chiasson BJ, Horsford DJ, Elia AJ, McInnes RR, van der Kooy D. Retinal stem cells in the adult mammalian eye. Science. 2000;287:2032–2036. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5460.2032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velde CV, Cleveland DW. VEGF: multitasking in ALS. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:5–7. doi: 10.1038/nn0105-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vergara C, Ramirez B. CNTF, a pleiotropic cytokine: emphasis on its myotrophic role. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2004;47:161–173. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2004.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vetter ML, Brown NL. The role of basic helix-loop-helix genes in vertebrate retinogenesis. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2001;12:491–498. doi: 10.1006/scdb.2001.0273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahlin KJ, Lim L, Grice EA, Campochiaro PA, Zack DJ, Adler R. A method for analysis of gene expression in isolated mouse photoreceptor and Muller cells. Mol Vis. 2004;10:366–375. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waid DK, McLoon SC. Immediate differentiation of ganglion cells following mitosis in the developing retina. Neuron. 1995;14:117–124. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90245-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waite KA, Eng C. From developmental disorder to heritable cancer: it's all in the BMP/TGF-beta family. Nat Rev Genet. 2003;4:763–773. doi: 10.1038/nrg1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace VA, Jensen AM. IBMX, taurine and 9-cis retinoic acid all act to accelerate rhodopsin expression in postmitotic cells. Exp Eye Res. 1999;69:617–627. doi: 10.1006/exer.1999.0741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wernet MF, Desplan C. Building a retinal mosaic: cell-fate decision in the fly eye. Trends Cell Biol. 2004;14:576–584. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2004.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wetts R, Fraser SE. Multipotent precursors can give rise to all major cell types of the frog retina. Science. 1988;239:1142–1145. doi: 10.1126/science.2449732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie HQ, Adler R. Green cone opsin and rhodopsin regulation by CNTF and staurosporine in cultured chick photoreceptors. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000;41:4317–4323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanagi Y, Takezawa S, Kato S. Distinct functions of photoreceptor cell-specific nuclear receptor, thyroid hormone receptor beta2 and CRX in one photoreceptor development. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002;43:3489–3494. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang XJ. Roles of cell-extrinsic growth factors in vertebrate eye pattern formation and retinogenesis. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2004;15:91–103. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2003.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young TL, Cepko CL. A role for ligand-gated ion channels in rod photoreceptor development. Neuron. 2004;41:867–879. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(04)00141-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuen EC, Howe CL, Li Y, Holtzman DM, Mobley WC. Nerve growth factor and the neurotrophic factor hypothesis. Brain Dev. 1996;18:362–368. doi: 10.1016/0387-7604(96)00051-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zareparsi S, Hero A, Zack DJ, Williams RW, Swaroop A. Seeing the unseen: Microarray-based gene expression profiling in vision. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45:2457–2462. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-0183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang SS, Fu XY, Barnstable CJ. Molecular aspects of vertebrate retinal development. Mol Neurobiol. 2002a;26:137–152. doi: 10.1385/MN:26:2-3:137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang SS, Fu XY, Barnstable CJ. Tissue culture studies of retinal development. Methods. 2002b;28:439–447. doi: 10.1016/s1046-2023(02)00263-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang XM, Yang XJ. Temporal and spatial effects of Sonic hedgehog signaling in chick eye morphogenesis. Dev Biol. 2001;233:271–290. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.0195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziman MR, Rodger J, Chen P, Papadimitriou JM, Dunlop SA, Beazley LD. Pax genes in development and maturation of the vertebrate visual system: implications for optic nerve regeneration. Histol Histopathol. 2001;16:239–249. doi: 10.14670/HH-16.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]