Abstract

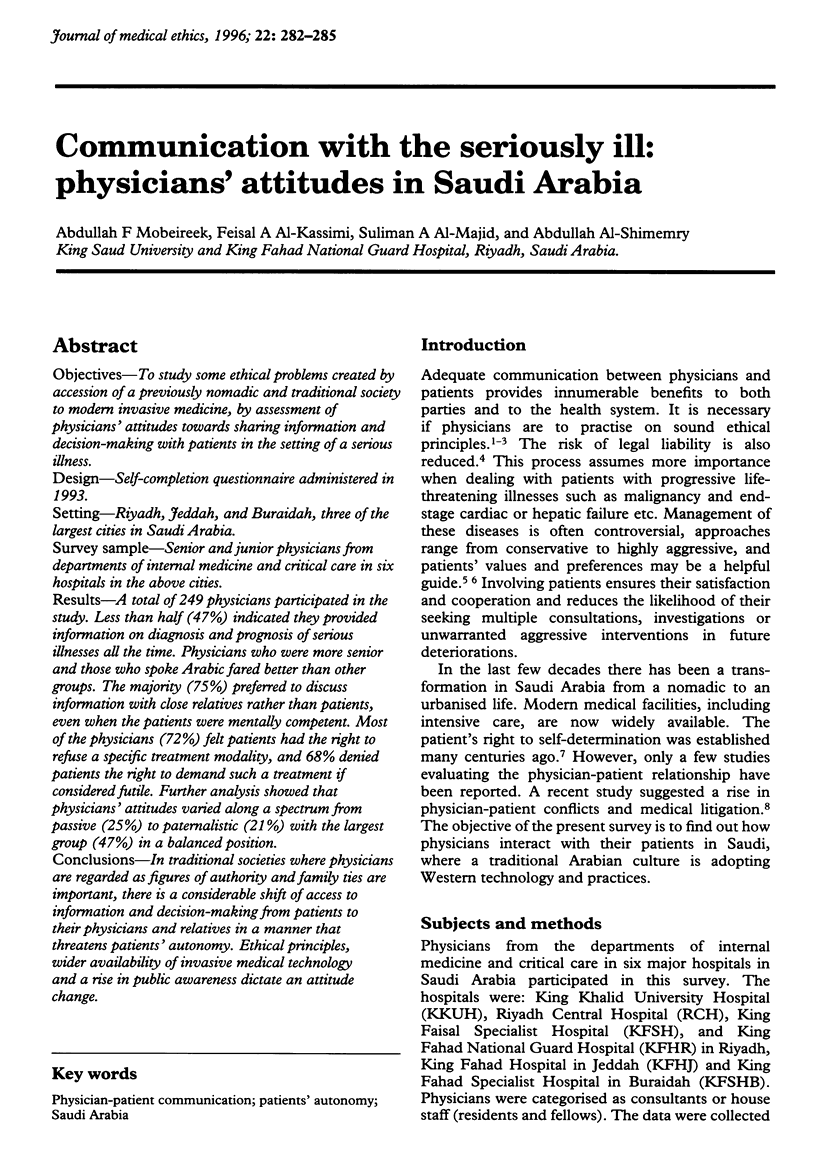

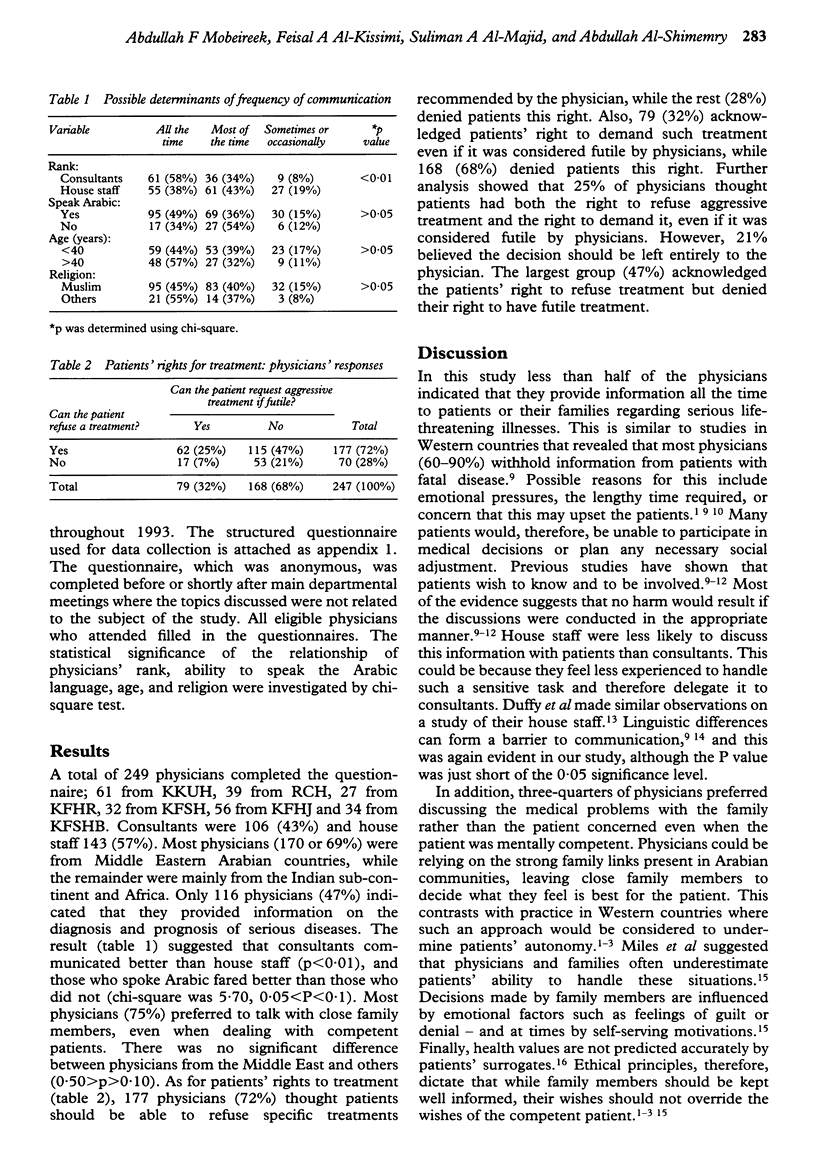

OBJECTIVES: To study some ethical problems created by accession of a previously nomadic and traditional society to modern invasive medicine, by assessment of physicians' attitudes towards sharing information and decision-making with patients in the setting of a serious illness. DESIGN: Self-completion questionnaire administered in 1993. SETTING: Riyadh, Jeddah, and Buraidah, three of the largest cities in Saudi Arabia. SURVEY SAMPLE: Senior and junior physicians from departments of internal medicine and critical care in six hospitals in the above cities. RESULTS: A total of 249 physicians participated in the study. Less than half (47%) indicated they provided information on diagnosis and prognosis of serious illnesses all the time. Physicians who were more senior and those who spoke Arabic fared better than other groups. The majority (75%) preferred to discuss information with close relatives rather than patients, even when the patients were mentally competent. Most of the physicians (72%) felt patients had the right to refuse a specific treatment modality, and 68% denied patients the right to demand such a treatment if considered futile. Further analysis showed that physicians' attitudes varied along a spectrum from passive (25%) to paternalistic (21%) with the largest group (47%) in a balanced position. CONCLUSIONS: In traditional societies where physicians are regarded as figures of authority and family ties are important, there is a considerable shift of access to information and decision-making from patients to their physicians and relatives in a manner that threatens patients' autonomy. Ethical principles, wider availability of invasive medical technology and a rise in public awareness dictate an attitude change.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Brett A. S., McCullough L. B. When patients request specific interventions: Defining the limits of the physician's obligation. N Engl J Med. 1986 Nov 20;315(21):1347–1351. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198611203152109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crisp A. H., Edwards W. J. Communication in medical practice across ethnic boundaries. Postgrad Med J. 1989 Mar;65(761):150–155. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.65.761.150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crisp A. H. Undergraduate training for communication in medical practice. J R Soc Med. 1986 Oct;79(10):568–574. doi: 10.1177/014107688607901004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy D. L., Hamerman D., Cohen M. A. Communication skills of house officers. A study in a medical clinic. Ann Intern Med. 1980 Aug;93(2):354–357. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-93-2-354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fine R. L. Personal choices: communication between physicians and patients when confronting critical illness. J Clin Ethics. 1991 Spring;2(1):57–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finucane T. E., Shumway J. M., Powers R. L., D'Alessandri R. M. Planning with elderly outpatients for contingencies of severe illness: a survey and clinical trial. J Gen Intern Med. 1988 Jul-Aug;3(4):322–325. doi: 10.1007/BF02595788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kai I., Ohi G., Yano E., Kobayashi Y., Miyama T., Niino N., Naka K. Communication between patients and physicians about terminal care: a survey in Japan. Soc Sci Med. 1993 May;36(9):1151–1159. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(93)90235-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine M. N., Gafni A., Markham B., MacFarlane D. A bedside decision instrument to elicit a patient's preference concerning adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer. Ann Intern Med. 1992 Jul 1;117(1):53–58. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-117-1-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles S. H., Cranford R., Schultz A. L. The do-not-resuscitate order in a teaching hospital: considerations and a suggested policy. Ann Intern Med. 1982 May;96(5):660–664. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-96-5-660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeifer M. P., Sidorov J. E., Smith A. C., Boero J. F., Evans A. T., Settle M. B. The discussion of end-of-life medical care by primary care patients and physicians: a multicenter study using structured qualitative interviews. The EOL Study Group. J Gen Intern Med. 1994 Feb;9(2):82–88. doi: 10.1007/BF02600206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts D. K. Prevention: patient communication. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1988 Mar;31(1):153–161. doi: 10.1097/00003081-198803000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsevat J., Cook E. F., Green M. L., Matchar D. B., Dawson N. V., Broste S. K., Wu A. W., Phillips R. S., Oye R. K., Goldman L. Health values of the seriously ill. SUPPORT investigators. Ann Intern Med. 1995 Apr 1;122(7):514–520. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-122-7-199504010-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waitzkin H. Doctor-patient communication. Clinical implications of social scientific research. JAMA. 1984 Nov 2;252(17):2441–2446. doi: 10.1001/jama.252.17.2441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]