Abstract

In the cyanobacterium Synechococcus elongatus (PCC 7942) the proteins KaiA, KaiB, and KaiC are required for circadian clock function. We deduced a circadian clock function for KaiA from a combination of biochemical and structural data. Both KaiA and its isolated carboxyl-terminal domain (KaiA180C) stimulated KaiC autophosphorylation and facilitated attenuation of KaiC autophosphorylation by KaiB. An amino-terminal domain (KaiA135N) had no function in the autophosphorylation assay. NMR structure determination showed that KaiA135N is a pseudo-receiver domain. We propose that this pseudo-receiver is a timing input-device that regulates KaiA stimulation of KaiC autophosphorylation, which in turn is essential for circadian timekeeping.

Circadian clocks among disparate groups of organisms share functional properties, but the proteins identified at their central cores lack sequence similarity beyond the PAS domains present in some, and there are no structural data available to reveal possible shared functions (1). In the cyanobacterium Synechococcus elongatus (PCC 7942), a model organism for prokaryotic circadian biology, the kai locus consists of three genes required for circadian clock function (2). None of the Kai proteins (KaiA, KaiB, or KaiC) shares sequence similarity with any eukaryotic clock protein (1, 3), even though the fundamental properties of cyanobacterial circadian rhythmicity (near 24-h free-running period, phase resetting by light, and a temperature compensation mechanism) are equivalent to those first established for numerous eukaryotic organisms including Neurospora crassa, Arabidopsis thaliana, and Drosophila melanogaster (3). We report here biochemical and structural data for KaiA, which together sanction a model in which the amino-terminal pseudo-receiver is a timing-input device that regulates carboxyl-terminal KaiA stimulation of KaiC autophosphorylation, which in turn is essential for circadian timekeeping.

The kai genes are ubiquitous among cyanobacteria, with probable kaiC sequence identified in forty phylogenetically diverse species (4). Accordingly, all six sequenced and annotated cyanobacterial genomes contain two contiguous ORFs with apparent homology to the S. elongatus kaiB and kaiC genes (annotated genome sequences for Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803 and Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120 are available at www.kazusa.or.jp/cyano/ and, for Prochlorococcus marinus MED4, Prochlorococcus marinus MIT9313, Synechococcus sp. strain WH8102, and Nostoc punctiforme at www.jgi.doe.gov/JGI_home.html). Across these species kaiA is the most sequence-diversified of the kai genes, as only four are identifiable via sequence comparisons. Curiously, the Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803 genome, which contains multiple kaiB and kaiC genes, has only one kaiA gene. Apparent homologues of kaiB and kaiC are found among noncyanobacterial eubacteria and the archaea. However, the kaiA gene appears confined within the cyanobacteria, which are the only prokaryotes with demonstrated circadian rhythms.

S. elongatus Kai proteins form oligomeric complexes in vitro in all possible combinations (5). In vivo data support formation of a higher-order complex that contains, at minimum, multiple protomers of each of the three Kai proteins, and likely includes the SasA protein kinase. In addition, both KaiB and KaiC protein levels, but not those of KaiA, display circadian cycles under free-running, constant-light conditions (5, 6). In functional terms, we know that point mutations in kaiC, which alter ATP binding and autokinase activities of KaiC, disrupt circadian rhythms of gene expression (7, 8). Cycles of KaiC phosphorylation also occur in a circadian time frame (9). These observations led us to ask how Kai protein interactions might affect the rate of KaiC autophosphorylation.

Materials and Methods

Cloning and Protein Purification.

The genes encoding KaiB, KaiA, KaiA135N, KaiA189N, and KaiA180C were cloned into the pET32a+ vector (Novagen) and subsequently overexpressed in Escherichia coli BL21(DE3) (Novagen). Genes encoding KaiC and KaiA were cloned into plasmid pQE32 (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) and subsequently overexpressed in E. coli M15 (Qiagen). This latter 6His-tagged KaiA was used only in the autophosphorylation assays. All other data were collected by using the pET32a+-derived KaiA protein. The QuikChange method from Stratagene was used to create site-specific mutations. DNA from relevant clones was then sequenced for verification (Gene Technologies Lab, Texas A&M University). For NMR sample preparation, bacteria were grown at 37°C in a minimal medium containing 15NH4Cl as the only nitrogen source, and either 13C6-glucose or unlabeled glucose as carbon source. Adding isopropyl β-d-thiogalactosepytanoside to 1 mM induced overproduction of the relevant protein. Cells were harvested after 5 h. Cell pellets containing KaiA, KaiA189N, and KaiA180C were resuspended in aqueous 20 mM Tris⋅HCl at pH 7.0 with 10 mM NaCl. For KaiA135N 50 mM NaCl was used. For KaiC, 6His-KaiA, and KaiB overproduction the cells were harvested 3.5 h after induction. Cell pellets were resuspended in aqueous 50 mM Tris⋅HCl at pH 7.5 with 300 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2, and 1 mM 2-mercaptoethanol. The solubility of KaiC was increased by also adding 1 mM ATP to the resuspension solution. Cell suspensions were passed twice through a French Press cell and the lysates clarified by centrifugation at 20,000 × g for 30 min. Tagged proteins were purified from the supernatant fraction on a Ni-charged chelating column and, if appropriate, dialyzed against the recommended enterokinase cleavage buffer (Novagen). After enterokinase cleavage (Novagen), the thioredoxin tag was separated from Kai protein by using a Ni-charged chelating column. All proteins were analyzed for purity by using SDS/PAGE and dialyzed to an appropriate final buffer, either for NMR spectroscopy or autophosphorylation assay.

Autophosphorylation Assays.

Autophosphorylation assays were run at 25°C. KaiC protein was at 1 μM in aqueous buffer containing 25 mM Tris⋅HCl, 200 mM KCl, 1 mM 2-mercaptoethanol and 5 mM MgCl2 at pH 7.5. To ensure initial velocity measurements, we did experiments over a range of constituent concentrations and established that 1 mM ATP, 3 μM KaiA, and 3 μM KaiB were saturating for KaiC autophosphorylation rate determinations (data not shown). The negative effect of KaiB on the KaiC-KaiA complex was also greatest with 1 mM ATP and 3 μM KaiB (data not shown). The addition of BSA (New England Biolabs), thioredoxin (Novagen plasmid pET32a+), SasA (10), or CikA (11) protein had no effect on KaiC autophosphorylation rates under any of our assay conditions (data not shown). The two independent KaiA domains were also added at 3 μM as determined by additional experiments as conducted for the full-length protein. Relevant proteins were mixed for at least 2 min before the assays were started by the addition of radiolabeled ATP. Time “zero” samples were taken immediately after this latter addition. Samples, taken at the indicated times, were thermally denatured and run on SDS/PAGE gels. Phosphorimages of dried gels were used to quantify the amount of 32PO incorporated into KaiC. Numerical values representing the percentage of the highest level of incorporation for a given experiment were determined. These values were averaged for each reaction condition (protein components) and plotted as a linear function of time. Relative rates are the slopes of the calculated regression lines.

incorporated into KaiC. Numerical values representing the percentage of the highest level of incorporation for a given experiment were determined. These values were averaged for each reaction condition (protein components) and plotted as a linear function of time. Relative rates are the slopes of the calculated regression lines.

Limited Proteolysis Assay.

We added 0.5 μg of trypsin (Promega) to 100 μl of 0.1 mM KaiA in aqueous buffer containing 50 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 7.6 at 25°C. Samples were taken at the indicated timepoints, thermally denatured and run on an SDS/PAGE gel. Apparent molecular weight and amino-terminal sequencing (Protein Chemistry Laboratory, Texas A&M University) were used to identify the three major species.

NMR Spectroscopy.

The solution conditions and chemical shift assignments of KaiA135N have been reported earlier (12). Additionally, chemical shift assignments for aromatic groups were identified by interpretation of the NOESY spectra. The oxidation states of the cysteine residues were determined as reduced by their 13Cβ chemical shifts. The isomerization state of all proline residues was determined (13) as trans except Pro-130, which was in the cis configuration. Stereospecific assignments of methylene Hγ protons as well as χ1 angle determinations (60°, −60°, 180°) were preformed by using HNHB (14) and HACAHB (15) experiments. Additional χ1 angles for valine, isoleucine, and threonine residues, as well as stereospecific assignments of valine Hγ methyl groups were obtained by determining long range 15N and 13C′ J-couplings to side chain methyl groups (16, 17). Because of limited chemical shift dispersion of leucine HΔ and isoleucine Hδ1 methyl groups we were able to determine only 1 χ2 angle out of 22 total using a 13C-13C J-coupling experiment (18). Stereospecific assignments of leucine Hδ methyl groups and proline methylene protons were found by interpreting the NOESY spectra. ϕ and ψ backbone angles were restrained by TALOS (19). 1H–1H NOE distance restraints were obtained by using 13C–15N edited and 13C–13C edited 4D NOESY spectra (20). Backbone 15N relaxation measurements (T1, T2, and NOE) were performed and analyzed as described earlier (21).

Structure Calculations.

1H–1H distances were grouped into four ranges depending on the NOESY cross-peak intensity. The lower distance bound was fixed to 1.8 Å. The upper distance bound was 2.7 Å for strong NOESY cross-peaks (2.9 Å for cross-peaks involving amide protons), 3.3 Å for medium NOESY cross-peaks (3.5 Å for cross-peaks involving amide protons), 5.0 Å for weak NOESY cross-peaks, and 6.0 for very weak NOESY cross-peaks. The upper distance bound was increased by 0.5 Å for the NOESY cross-peaks involving methyl groups. A distance geometry simulated annealing protocol was used under the program x-plor (22) to calculate structures of KaiA135N. During the refinement and minimization stages, a conformational database potential (23, 24) was applied in addition to the usual potentials.

Results

Relative KaiC Autophosphorylation Rates.

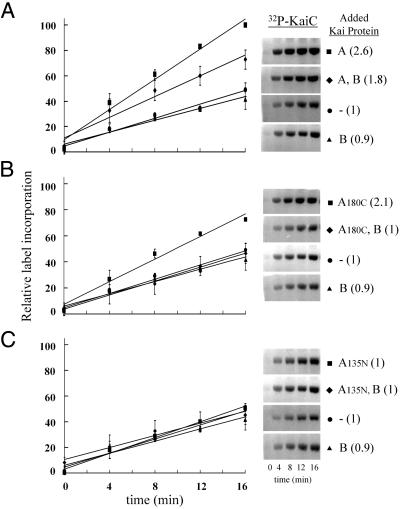

The in vitro rate of KaiC autophosphorylation provided an assay for examining Kai protein functional interactions. Purified KaiC was incubated with [γ-32P] adenosine 5′-triphosphate alone and also in combination with the KaiA and KaiB proteins. Initial rate conditions were established as described in Materials and Methods. Surprisingly, the rate of KaiC autophosphorylation was unaltered by the addition of KaiB even though these two proteins are known to interact (5) (Fig. 1A). Addition of KaiA to the assay increased the KaiC autophosphorylation rate ≈2.5-fold (Fig. 1A). In assays that included all three Kai proteins the rate of autophosphorylation was increased relative to KaiC alone, yet decreased relative to the KaiA–KaiC protein combination (Fig. 1A). Thus, KaiA has at least one clock-related activity: it stimulates KaiC autophosphorylation, which is functionally important for circadian timekeeping (7, 8). Data supporting this activity are also reported in an accompanying article (9). Furthermore, KaiB has a negative role in the assay only when KaiA is present (Fig. 1A).

Fig 1.

Influence of Kai proteins on the autophosphorylation rate of KaiC. (A) Assays were run under initial rate conditions as described (see Materials and Methods). The graph illustrates the time course of KaiC autophosphorylation with ATP in the presence of KaiA, KaiA and KaiB, no additional protein, and KaiB. All time points are the average of four independent experiments, including the one represented by the gel images. Error bars indicate standard deviation from the mean (n = 4). Relative rates calculated from the line slopes are indicated parenthetically. (B) As above but the KaiA180C domain was substituted for KaiA in each assay. (C) As above but the Kai135N domain was substituted for KaiA in each assay.

Two-Domain Structure of KaiA Protein.

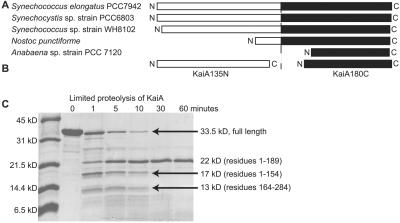

Sequence alignment suggested at least two types of KaiA proteins: long and short. The long versions (from the unicellular species S. elongatus, Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803, and Synechococcus sp. strain WH8102) consist of ≈300 aminoacyl residues. There is limited sequence conservation in the amino-terminal 200 residues of these proteins but a high degree of conservation in the carboxyl-terminal 100 residues. The short versions (from the filamentous species Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120 and Nostoc punctiforme) are essentially independent carboxyl-terminal domains (Fig. 2A). Thus, two distinct regions, possibly independent domains, seemed likely. Note that results from searches of the filamentous organisms' annotated genomes for sequences resembling the amino-terminal region of a long KaiA protein were negative.

Fig 2.

(A) Graphic representation of five apparent KaiA homologs from the listed cyanobacteria. The amino termini are regions of low sequence similarity and are represented by white boxes. The carboxyl termini are regions of high sequence similarity and are represented by black boxes. (B) Graphic representation of the two independent domains derived from S. elongatus KaiA in this study. (C) An SDS/PAGE gel containing samples from a limited trypsin digest assay (see Materials and Methods). As indicated, we observed three major species. Production of the KaiA135N and KaiA180C domains was, in part, based on the largest and smallest of the three species.

Limited proteolysis assays of the 284-residue KaiA protein from S. elongatus supported our presumption of two independently folded domains (Fig. 2C). Amino-terminal sequencing identified three major protein species, with apparent molecular weights of 22 kDa (residues 1–189), 17 kDa (residues 1–154), and 13 kDa (residues 164–284) from our proteolysis assays (Fig. 2C). CD spectra of the KaiA180C domain, corresponding to residues 180–284, revealed primarily α-helical structure (see supporting information, which is published on the PNAS web site, www.pnas.org). In addition, an 15N heteronuclear single quantum coherence (HSQC) spectrum showed chemical shift dispersion consistent with an α-helical protein (see supporting information). Thus, we consider the KaiA180C domain to be independently folded.

The 15N-HSQC spectrum of the KaiA189N domain, corresponding to residues 1–189, indicated that this portion of KaiA also folds independently (see supporting information). However, this domain contains a significant number of conformationally flexible residues. A series of carboxyl-terminal truncations showed that the smallest well folded amino-terminal domain consists of residues 1–135 (KaiA135N) (12). A CD spectrum of KaiA189N revealed higher helical content than the corresponding spectrum from our derived KaiA135N domain (see supporting information). The S. elongatus KaiA protein thus appears to contain two domains, the amino and carboxyl regions, connected by a helical linker of ≈50 residues (Fig. 2B).

In Vitro Function of Isolated KaiA Domains.

To address function we examined the rate of KaiC autophosphorylation in the presence of these two independent KaiA domains. Again, initial rate conditions were established for these assays. Addition of KaiA180C to the autophosphorylation assay described above gave results similar to full-length KaiA (Fig. 1B). Specifically, the rates of increase in KaiC autophosphorylation (≈2-fold), and net decrease on addition of KaiB were nearly identical in the presence of either KaiA protein or the KaiA180C domain (Fig. 1B). Addition of KaiA135N to the autophosphorylation assays produced no observable rate changes with or without KaiB protein (Fig. 1C). Thus, the domain of KaiA most highly conserved among the cyanobacteria, the carboxyl terminus, interacts with KaiC and stimulates autophosphorylation. The other KaiA domain, represented by KaiA135N and having much less sequence conservation, does not functionally interact with KaiC in this assay. However, we recognize that this domain is vitally important for generating circadian rhythmicity, based on phenotypic data from a large number of mutant kaiA alleles that encode point mutations manifest in the amino-terminal domain. Strains harboring these alleles have lengthened circadian periods in their gene expression rhythms (25).

Solution Structure of KaiA135N.

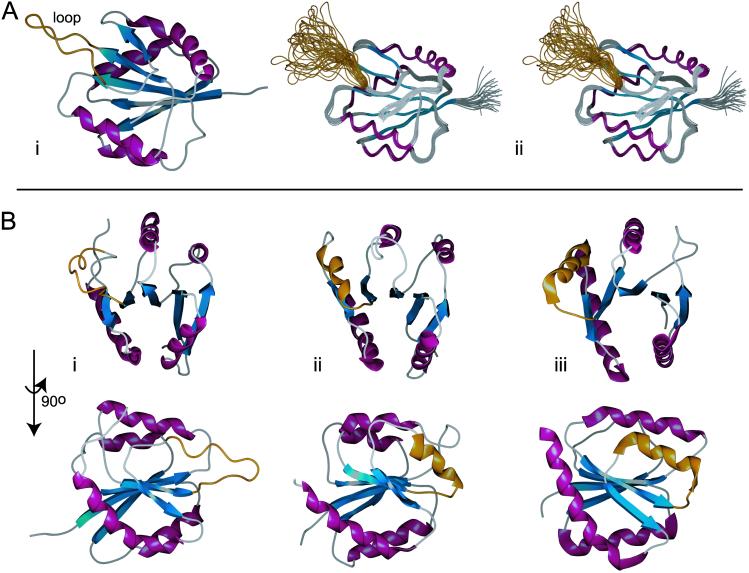

The solution structure of KaiA135N provided insight into its function and, subsequently, into modeling KaiA protein function (Fig. 3 and supporting information). We used the Dali similarity search to compare KaiA135N structure with known protein structures (26). The six most similar structures, using the average minimized KaiA135N domain structure (Fig. 3Ai) as query, were all two-component-type receiver domains, namely, those from the DrrD, CheY, NarL, FixJ, Etr1, and AmiR proteins (27). This result was not anticipated by either sequence alignment or fold recognition algorithms (28). The average Cα rms deviation for these six receiver domains was 2.5 Å for 86% of the main chain, and the average structure similarity score (Z score) was 12.6. By comparison, a similarity search based on CheY protein (PDB ID ; ref. 29), the prototypical bacterial receiver domain, returned an average Cα rms deviation of 2.2 Å for 92% of the main chain with an average Z score of 15.5 for the best six receiver domain matches (Z score threshold for structurally similar proteins is 2; see supporting information). Conspicuously, KaiA135N lacks the conserved aspartyl residues necessary for the Mg+2-dependent phosphoryl-transfer activity that defines canonical receiver domains (30). Direct comparison to CheY shows that Asp-57, Asp-12 and Asp-13 are transposed to Asn-60, Glu-12 and Ser-13 in the KaiA135N domain. Moreover, KaiA135N fails to bind Mg+2, as titration with MgCl2 did not show significant changes in the 15N-HSQC spectrum (data not shown).

Fig 3.

The solution structure of KaiA135N and comparisons to other receiver domain proteins. β-strands are in blue, α-helices are in purple, and the flexible loop of KaiA135N and the equivalent region of other receiver domains are in gold. The structure coordinates have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank under PDB ID codes and for the average minimized structure and the family of structures, respectively. (Ai) Schematic representation of the average minimized structure. The solution structure of KaiA135N is an α-β-α sandwich built around a five-parallel-strand β-sheet with b-a-c-d-e arrangement. The rotational correlation time (τc) was calculated to be ≈8.2 ns, which is consistent with a monomer in solution (21). (Aii) Stereoview of the overlaid backbone of a family of 25 low-energy structures calculated from 2,034 distance and geometry restraints. The backbone rms deviation from the average is 0.38 ± 0.04 Å for residues 4–83 and 98–135. The rms deviation for all heavy atoms is 0.78 ± 0.05 Å for the same residues. Few medium- or long-range NOE contacts were identified for residues 83–97, and 15N dynamics (see supporting information) showed that this region is highly dynamic. (B) Structural comparison of KaiA135N with other receiver domains. Shown here are KaiA135N (Bi), the NtrC (1DC7) receiver domain (Bii), and the AmiR (1QO0, residues 11–131) receiver domain (Biii) at two mutually orthogonal views. Figures were prepared with spock (38).

Effect of Residue Substitution on KaiA135N Structure.

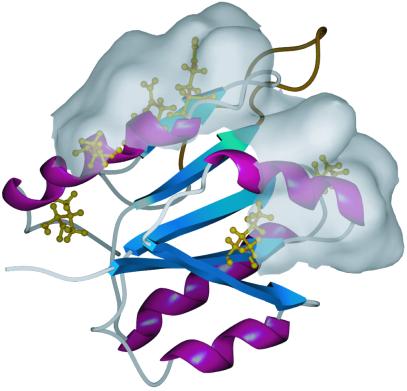

A number of kaiA alleles alter the periodicity of clock-regulated gene expression rhythms in S. elongatus (25, 31). Thirteen of these alleles encode amino acyl residue substitutions that lie within the KaiA135N domain. We produced each substituted domain and then examined the effects of residue substitution on KaiA135N structure by comparing their 15N-HSQC spectra to that of the wild type under the same conditions. Five substitutions (L31P: prolyl for leucyl residue at position 31, S36P, C53S, V76G, and E103K) resulted in unfolded domains as judged by a lack of chemical shift dispersion in their spectra (data not shown). These domains also had decreased solubility compared with the wild type, based on their tendency to aggregate on concentration. One substitution (V76A) also tended to aggregate on concentration but its spectra showed better chemical shift dispersion than the others. All six of these substitutions involve buried residues and most likely perturb stabilizing interactions. The remaining substitutions (I9T, I16F, Q113R, Q117L, D119E, D119G, V131A) gave stable KaiA135N domains whose 15N-HSQC spectra were similar to that of the wild type. Five of these latter substitutions were in α2 or α4 and chemical shift comparison of each substituted domain's spectrum to that of the wild type revealed structural changes localized to a small area of the protein (Fig. 4).

Fig 4.

Stable KaiA135N clock-period altering mutations and a putative protein-interacting surface. Shown here is the average minimized structure of KaiA135N. Residue substitutions that yield stable proteins in vitro are shown in gold. Most of these residues are mapped on α2 or α4 (I16F, Q113R, Q117L, D119E, D119G). Chemical shift analysis of the mutant proteins versus the wild-type protein showed changes extending over these two helices. Shown here is the water-accessible surface of the residues affected by these mutations. We postulate that this surface is important for signal transduction either between KaiA135N and an upstream signal component or between the two KaiA domains.

Discussion

Despite the explicit structural similarities, KaiA135N should not be competent to function as a canonical receiver domain. It lacks the conserved aspartyl residues necessary for a Mg+2-dependent phosphoryl-transfer activity. Instead, we propose that it is a pseudo-receiver domain and functions much like the corresponding domain in AmiR (Fig. 3Biii). Free AmiR protein activates aliphatic amidase operon expression in Pseudomonas aeruginosa via a transcription antitermination activity (32). However, in the absence of aliphatic amides, AmiC protein binds directly to the AmiR pseudo-receiver domain and effectively sequesters AmiR. This action allows transcription termination of the amidase operon message. Interestingly, the AmiR protein's binding interface is α4 (32). The corresponding α-helix in CheY is the interface between that protein and its cognate, signal transducing, protein kinase CheA (33). Furthermore, receiver domain α4 helices are flexible and this flexibility evidently allows switching between inactive and active states (34). These states then regulate other regions/activities of the respective proteins (34–36). In the KaiA135N domain however, this interface-helix is replaced by an unstructured, solvent-exposed loop composed of residues 83–97 (Fig. 3Ai) as shown both by the almost complete lack of medium or long-range 1H–1H NOEs and 15N backbone dynamics analysis (see supporting information). This loop may serve a similar interfacing role for the KaiA protein. However, consideration of a set of seven amino acyl residue substitutions in the KaiA135N domain, which alter the periodicity of clock-regulated gene expression rhythms (25, 31), yet result in folded, stable proteins, suggests another KaiA protein interface. The period-altering substitutions I16F, Q113R, Q117L, D119E, and D119G, map on α2 or α4 and cause only localized changes in the protein (Fig. 4); therefore, we also consider this part of the KaiA135N domain as a potential protein-interacting surface. It will be interesting to determine whether this surface and the unstructured, solvent-exposed loop are important for interactions with an upstream signal-input protein, or for KaiA interdomain communication.

A pseudo-receiver domain is also found in two other circadian clock proteins, TOC1 from A. thaliana and CikA from S. elongatus (10, 37). Thus, a second potential evolutionary connection between plant and cyanobacterial circadian timekeeping mechanisms has been identified. The cikA gene in S. elongatus encodes a bacteriophytochrome, and phytochromes are integral components of plant circadian rhythm generation (11). Conceivably, these two S. elongatus circadian clock components have a functional connection. If, as we have argued, KaiA receives environmental cues via its pseudo-receiver domain, then some of those cues likely originate from the environmentally responsive, phase-resetting CikA protein. We have also demonstrated a likely activity for those cues to ultimately influence: modulation by KaiA of the rate at which KaiC autophosphorylates.

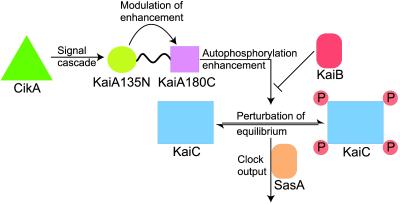

Consequently, we model timekeeping as changes in the phosphorylation rate of KaiC protein (Fig. 5). The KaiC phosphosphorylation state may determine the protein's degradation rate as is true for eukaryotic clock proteins FRQ and PER (3); may influence other possible activities such as chromosome condensation (7); may determine its aggregation state in homo- and heterotypic interactions (5, 8); may alter its interaction with regulatory proteins such as the SasA protein kinase (10); or may affect aspects of all these potential activities. Although there are not yet sufficient data to distinguish among these functional possibilities, we favor a model that includes phosphorylation as a potential degradation signal for two reasons. First, ectopic overproduction of KaiA, expected to increase the rate of KaiC turnover, causes elevated (and arrhythmic) kaiC gene expression patterns (2). Second, ectopic overproduction of KaiC, expected to decrease the rate of KaiC turnover, represses (and makes arrhythmic) kaiC gene expression patterns (2). These data fit into a feedback regulatory mechanism as required for the cyclic patterns of gene expression harmonized by the circadian clock. Comparisons among cyanobacterial genomes would further suggest that stimulation of KaiC autophosphorylation by the carboxyl-terminal domain of KaiA is a conserved function. However, input signaling, as we propose for the S. elongatus KaiA amino-terminal domain, can be achieved by various mechanisms. This finding is not surprising given that sequence similar to that of S. elongatus ' CikA protein is also not ubiquitous among cyanobacteria (11). Variations in input mechanisms likely reflect the diversity of cyanobacterial metabolism and habitat.

Fig 5.

Working model of KaiA protein function and its role in S. elongatus circadian timekeeping. CikA and other environmental sensors initiate signal transduction cascades that result in activation of the KaiA pseudo-receiver domain. This activation modulates the KaiA carboxyl-terminal domain's enhancement of the KaiC autophosphorylation rate. Thus, equilibria between KaiC phosphorylation states are perturbed. These states differentially control clock output, possibly through the SasA protein kinase. In this manner, a cycle of input, oscillation, and output can be established.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank T. Kondo, H. Iwasaki, T. Nishiwaki, Y. Kitayama, and M. Nakajima (Nagoya University, Nagoya, Japan) for sharing unpublished results. We also thank P. LiWang for assistance and helpful discussions, Michael Polymenis for insight, and K. Koshlap for NMR support. J. Ditty and S. Canales improved the manuscript. We thank Larry Dangott and the Protein Chemistry Lab for amino terminal sequencing. NMR instrumentation at Texas A&M University is supported by National Science Foundation Grant DBI-9970232 and by the Texas Agricultural Experiment Station. Financial support was provided by National Institutes of Health Grant 1R01GM064576-01 (to A.C.L.), National Science Foundation Grant MCB-9982852 and the Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board Advanced Research Project 010366-0076-1999 (to S.S.G.), and National Institutes of Health National Research Science Award F32GM19644 (to S.B.W.).

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

Data deposition: The crystal structures and coordinates reported in this paper have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, www.rcsb.org (PBD ID codes and ).

References

- 1.Golden S. S., Johnson, C. H. & Kondo, T. (1998) Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 1 669-673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ishiura M., Kutsuna, S., Aoki, S., Iwasaki, H., Andersson, C. R., Tanabe, A., Golden, S. S., Johnson, C. H. & Kondo, T. (1998) Science 281 1519-1523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Young M. W. & Kay, S. A. (2001) Nat. Rev. Genet. 2 702-715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lorne J., Scheffer, J., Lee, A., Painter, M. & Miao, V. P. (2000) FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 189 129-133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Iwasaki H., Taniguchi, Y., Ishiura, M. & Kondo, T. (1999) EMBO J. 18 1137-1145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xu Y., Mori, T. & Johnson, C. H. (2000) EMBO J. 19 3349-3357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mori T. & Johnson, C. H. (2001) Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 12 271-278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nishiwaki T., Iwasaki, H., Ishiura, M. & Kondo, T. (2000) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97 495-499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iwasaki H., Nishiwaki, T., Kitayama, Y., Nakajima, M. & Kondo, T. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99 15788-15793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Iwasaki H., Williams, S. B., Kitayama, Y., Ishiura, M., Golden, S. S. & Kondo, T. (2000) Cell 101 223-233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schmitz O., Katayama, M., Williams, S. B., Kondo, T. & Golden, S. S. (2000) Science 289 765-768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vakonakis I., Risinger, A. T., Latham, M. P., Williams, S. B., Golden, S. S. & LiWang, A. C. (2001) J. Biomol. NMR 21 179-180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wüthrich K., (1986) NMR of Proteins and Nucleic Acids (Wiley, New York).

- 14.Madsen J. C., Sorensen, O. W., Sorensen, P. & Poulsen, F. M. (1993) J. Biomol. NMR 3 239-244. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grzesiek S., Kuboniwa, H., Hinck, A. P. & Bax, A. (1995) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 117 5312-5315. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grzesiek S. & Bax, A. (1993) J. Biomol. NMR 3 185-204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vuister G. W., LiWang, A. C. & Bax, A. (1993) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 115 5334-5335. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bax A., Max, D. & Zax, D. (1992) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 114 6924-6925. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cornilescu G., Delaglio, F. & Bax, A. (1999) J. Biomol. NMR 13 289-302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clore G. M. & Gronenborn, A. M. (1991) Science 252 1390-1399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.LiWang A. C., Cao, J. J., Zheng, H., Lu, Z., Peiper, S. C. & LiWang, P. J. (1999) Biochemistry 38 442-453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bronger A. T., (1987) X-PLOR: A System for X-Ray Crystallography and NMR (Yale University Press, New Haven, CT), Version 3.1.

- 23.Kuszewski J., Gronenborn, A. M. & Clore, G. M. (1996) Protein Sci. 5 1067-1080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kuszewski J., Gronenborn, A. M. & Clore, G. M. (1997) J. Magn. Reson. 125 171-177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nishimura H., Nakahira, Y., Imai, A., Tsuruhara, A., Kondo, H., Hayashi, H., Hirai, M., Saito, H. & Kondo, T. (2002) Microbiology 148 2903-2909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Holm L. & Sander, C. (1998) Nucleic Acids Res. 26 316-319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Volz K. (1993) Biochemistry 32 11741-11753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kelley L. A., MacCallum, R. M. & Sternberg, M. J. (2000) J. Mol. Biol. 299 499-520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Simonovic M. & Volz, K. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276 28637-28640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bourret R. B., Hess, J. F. & Simon, M. I. (1990) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 87 41-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kondo T. & Ishiura, M. (1994) J. Bacteriol. 176 1881-1885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.O'Hara B. P., Norman, R. A., Wan, P. T., Roe, S. M., Barrett, T. E., Drew, R. E. & Pearl, L. H. (1999) EMBO J. 18 5175-5186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Welch M., Chinardet, N., Mourey, L., Birck, C. & Samama, J. P. (1998) Nat. Struct. Biol 5 25-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Volkman B. F., Lipson, D., Wemmer, D. E. & Kern, D. (2001) Science 291 2429-2433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hwang I., Thorgeirsson, T., Lee, J., Kustu, S. & Shin, Y. K. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96 4880-4885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kern D., Volkman, B. F., Luginbuhl, P., Nohaile, M. J., Kustu, S. & Wemmer, D. E. (1999) Nature 402 894-898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Strayer C., Oyama, T., Schultz, T. F., Raman, R., Somers, D. E., Más, P., Panda, S., Kreps, J. A. & Kay, S. A. (2000) Science 289 768-771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Christopher J., (1999) SPOCK: The Structural Properties Observation and Calculation Kit (Center for Macromolecular Design, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.