Abstract

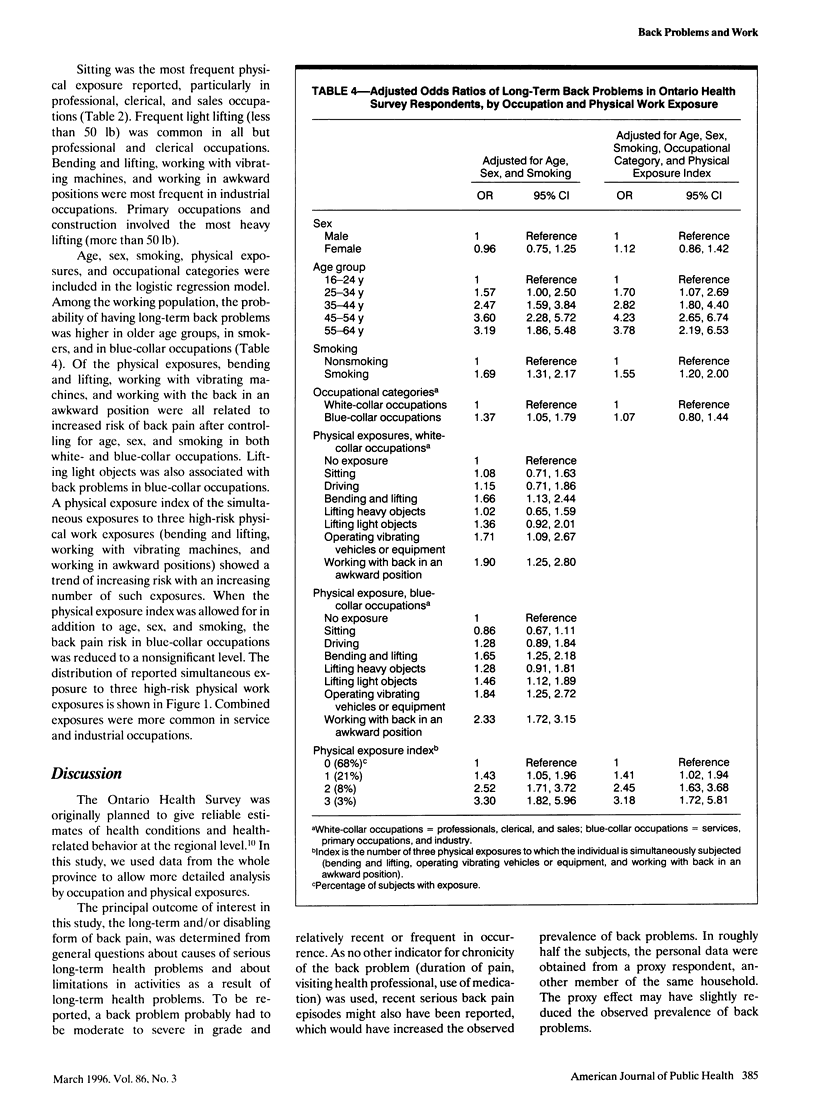

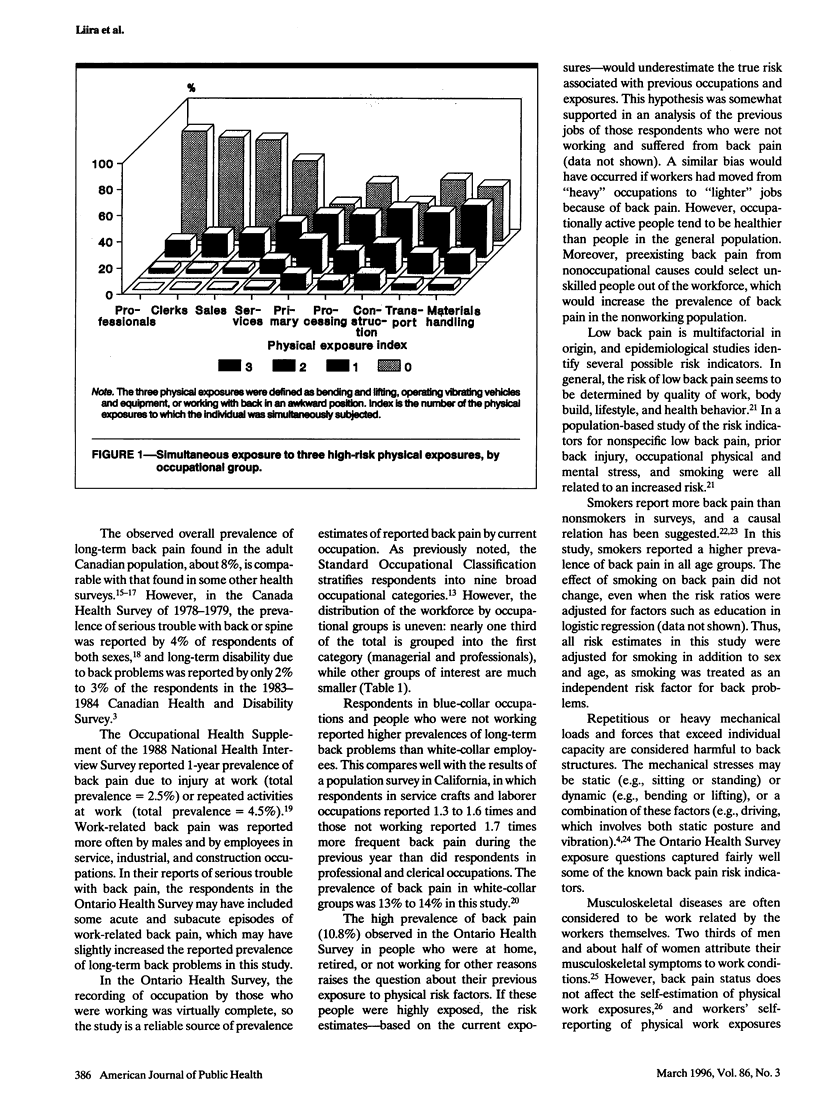

OBJECTIVES. This study sought to provide data on the relationship of work exposures to long-term back problems in a population survey. METHODS. The Ontario Health Survey in 1990 used a representative population sample of the province. It included data on long-term back problems, occupational activity, and physical work exposures. The current study examined relationships between these variables. RESULTS. The prevalence of long-term back problems was 7.8% in working-age adults. It generally increased with age. Long-term back problems were more prevalent in blue-collar occupations and among those not working, as well as among people with less formal education, smokers, and those overweight. Physical work exposures--awkward working position, working with vibrating vehicles or equipment, and bending and lifting--were all associated with a greater risk of back problems. The number of simultaneous physical exposures was monotonically related to increased risk. CONCLUSIONS. Within the limitations of the data and assuming the relationship to be causal, about one quarter of the excess back pain morbidity in the working population could be explained by physical work exposures.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Badley E. M., Rasooly I., Webster G. K. Relative importance of musculoskeletal disorders as a cause of chronic health problems, disability, and health care utilization: findings from the 1990 Ontario Health Survey. J Rheumatol. 1994 Mar;21(3):505–514. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badley E. The impact of musculoskeletal disorders on the Canadian population. J Rheumatol. 1992 Mar;19(3):337–340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behrens V., Seligman P., Cameron L., Mathias C. G., Fine L. The prevalence of back pain, hand discomfort, and dermatitis in the US working population. Am J Public Health. 1994 Nov;84(11):1780–1785. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.11.1780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burdorf A. Sources of variance in exposure to postural load on the back in occupational groups. Scand J Work Environ Health. 1992 Dec;18(6):361–367. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.1561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cats-Baril W. L., Frymoyer J. W. Identifying patients at risk of becoming disabled because of low-back pain. The Vermont Rehabilitation Engineering Center predictive model. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1991 Jun;16(6):605–607. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199106000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham L. S., Kelsey J. L. Epidemiology of musculoskeletal impairments and associated disability. Am J Public Health. 1984 Jun;74(6):574–579. doi: 10.2105/ajph.74.6.574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deyo R. A., Bass J. E. Lifestyle and low-back pain. The influence of smoking and obesity. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1989 May;14(5):501–506. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198905000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deyo R. A., Tsui-Wu Y. J. Descriptive epidemiology of low-back pain and its related medical care in the United States. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1987 Apr;12(3):264–268. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198704000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frymoyer J. W., Cats-Baril W. Predictors of low back pain disability. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1987 Aug;(221):89–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heliövaara M., Mäkelä M., Knekt P., Impivaara O., Aromaa A. Determinants of sciatica and low-back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1991 Jun;16(6):608–614. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199106000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heliövaara M., Sievers K., Impivaara O., Maatela J., Knekt P., Mäkelä M., Aromaa A. Descriptive epidemiology and public health aspects of low back pain. Ann Med. 1989 Oct;21(5):327–333. doi: 10.3109/07853898909149216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee P., Helewa A., Smythe H. A., Bombardier C., Goldsmith C. H. Epidemiology of musculoskeletal disorders (complaints) and related disability in Canada. J Rheumatol. 1985 Dec;12(6):1169–1173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leino P. Symptoms of stress predict musculoskeletal disorders. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1989 Sep;43(3):293–300. doi: 10.1136/jech.43.3.293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reisbord L. S., Greenland S. Factors associated with self-reported back-pain prevalence: a population-based study. J Chronic Dis. 1985;38(8):691–702. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(85)90023-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riihimäki H. Low-back pain, its origin and risk indicators. Scand J Work Environ Health. 1991 Apr;17(2):81–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sievers K., Klaukka T. Back pain and arthrosis in Finland. How many patients by the year 2000? Acta Orthop Scand Suppl. 1991;241:3–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svensson H. O., Vedin A., Wilhelmsson C., Andersson G. B. Low-back pain in relation to other diseases and cardiovascular risk factors. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1983 Apr;8(3):277–285. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198304000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]