Abstract

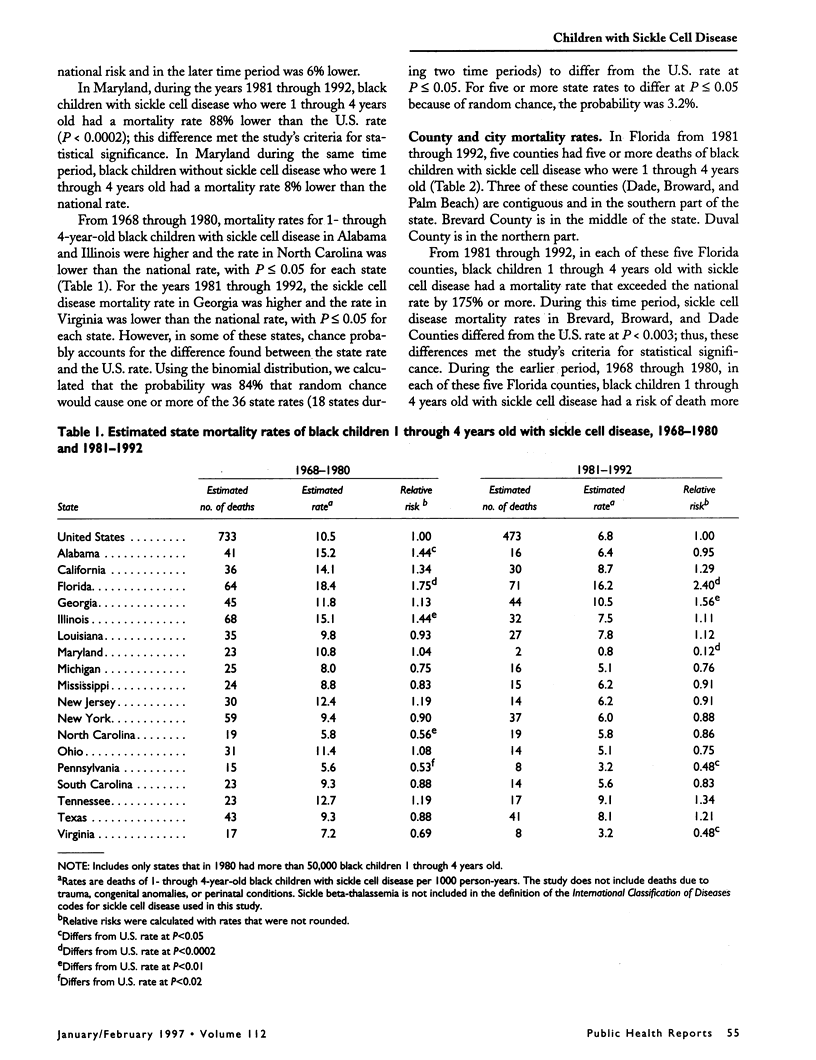

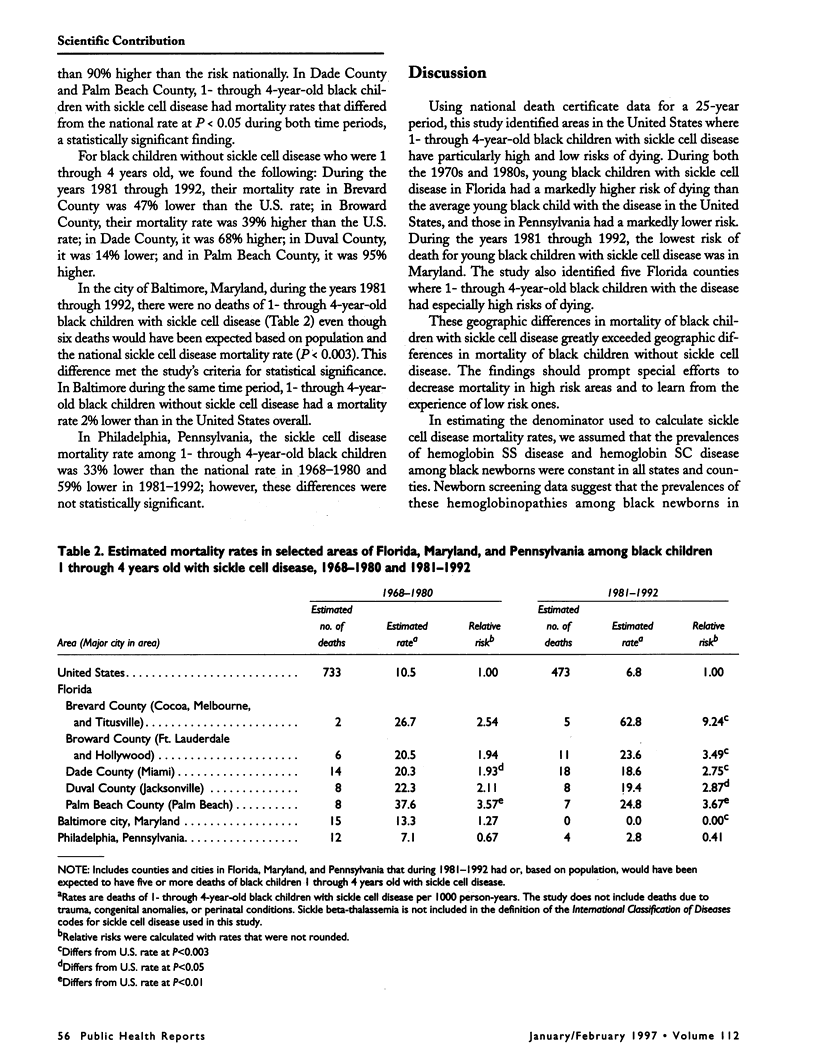

OBJECTIVES: Because geographic differences in health care have been found for many diseases, including those affecting children, there are probably geographic differences in the health care of young children with sickle cell disease. Consequently, survival of young children with sickle cell disease might differ among geographic areas. This study's objective was to identify areas in the United States where young children with sickle cell disease are at especially high and low risk of dying. METHODS: Using U.S. death certificate data from 1968 through 1992, the authors calculated the mortality rates of 1- through 4-year-old black children with sickle cell disease for states, counties, and cities. Deaths from trauma, congenital anomalies, and perinatal conditions were excluded. RESULTS: From 1968 through 1980 and from 1981 through 1992, 1- through 4-year-old black children with sickle cell disease in Florida had a markedly higher risk of dying, and those in Pennsylvania had a markedly lower risk of dying, than the average 1- through 4-year-old black child with the disease in the United States. From 1981 through 1992, 1- through 4-year-old black children with sickle cell disease in Maryland had the lowest mortality rate in the nation. During the same time period, 1- through 4-year-old black children with sickle cell disease in five counties in Florida were at especially high risk, while in Baltimore no young black children with the disease died. These geographic differences in mortality of black children with sickle cell disease greatly exceeded geographic differences in mortality of black children without the disease. CONCLUSIONS: Marked differences exist across the United States in mortality of young black children with sickle cell disease. To improve survival for children with the disease in high mortality areas, evaluations should be made of the accessibility and quality of medical care, and of parents' health care seeking behavior and compliance with antibiotic prophylaxis. In addition, efforts should be made to understand and duplicate the success of treatment programs in low mortality areas.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Bainbridge R., Higgs D. R., Maude G. H., Serjeant G. R. Clinical presentation of homozygous sickle cell disease. J Pediatr. 1985 Jun;106(6):881–885. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(85)80230-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaston M. H., Verter J. I., Woods G., Pegelow C., Kelleher J., Presbury G., Zarkowsky H., Vichinsky E., Iyer R., Lobel J. S. Prophylaxis with oral penicillin in children with sickle cell anemia. A randomized trial. N Engl J Med. 1986 Jun 19;314(25):1593–1599. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198606193142501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guess H. A., Lydick E. G., Small R. D., Miller L. P. Epidemiologic programs for computers and calculators. Exact binomial confidence intervals for the relative risk in follow-up studies with sparsely stratified incidence density data. Am J Epidemiol. 1987 Feb;125(2):340–347. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leikin S. L., Gallagher D., Kinney T. R., Sloane D., Klug P., Rida W. Mortality in children and adolescents with sickle cell disease. Cooperative Study of Sickle Cell Disease. Pediatrics. 1989 Sep;84(3):500–508. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobel J. S., Cameron B. F., Johnson E., Smith D., Kalinyak K. Value of screening umbilical cord blood for hemoglobinopathy. Pediatrics. 1989 May;83(5 Pt 2):823–826. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mack A. K. Florida's experience with newborn screening. Pediatrics. 1989 May;83(5 Pt 2):861–863. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motulsky A. G. Frequency of sickling disorders in U.S. blacks. N Engl J Med. 1973 Jan 4;288(1):31–33. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197301042880108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrin J. M., Homer C. J., Berwick D. M., Woolf A. D., Freeman J. L., Wennberg J. E. Variations in rates of hospitalization of children in three urban communities. N Engl J Med. 1989 May 4;320(18):1183–1187. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198905043201805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powars D., Chan L. S., Schroeder W. A. The variable expression of sickle cell disease is genetically determined. Semin Hematol. 1990 Oct;27(4):360–376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powars D. Diagnosis at birth improves survival of children with sickle cell anemia. Pediatrics. 1989 May;83(5 Pt 2):830–833. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powars D., Overturf G., Weiss J., Lee S., Chan L. Pneumococcal septicemia in children with sickle cell anemia. Changing trend of survival. JAMA. 1981 May 8;245(18):1839–1842. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vichinsky E., Hurst D., Earles A., Kleman K., Lubin B. Newborn screening for sickle cell disease: effect on mortality. Pediatrics. 1988 Jun;81(6):749–755. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wennberg J., Gittelsohn A. Variations in medical care among small areas. Sci Am. 1982 Apr;246(4):120–134. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican0482-120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarkowsky H. S., Gallagher D., Gill F. M., Wang W. C., Falletta J. M., Lande W. M., Levy P. S., Verter J. I., Wethers D. Bacteremia in sickle hemoglobinopathies. J Pediatr. 1986 Oct;109(4):579–585. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(86)80216-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]