Abstract

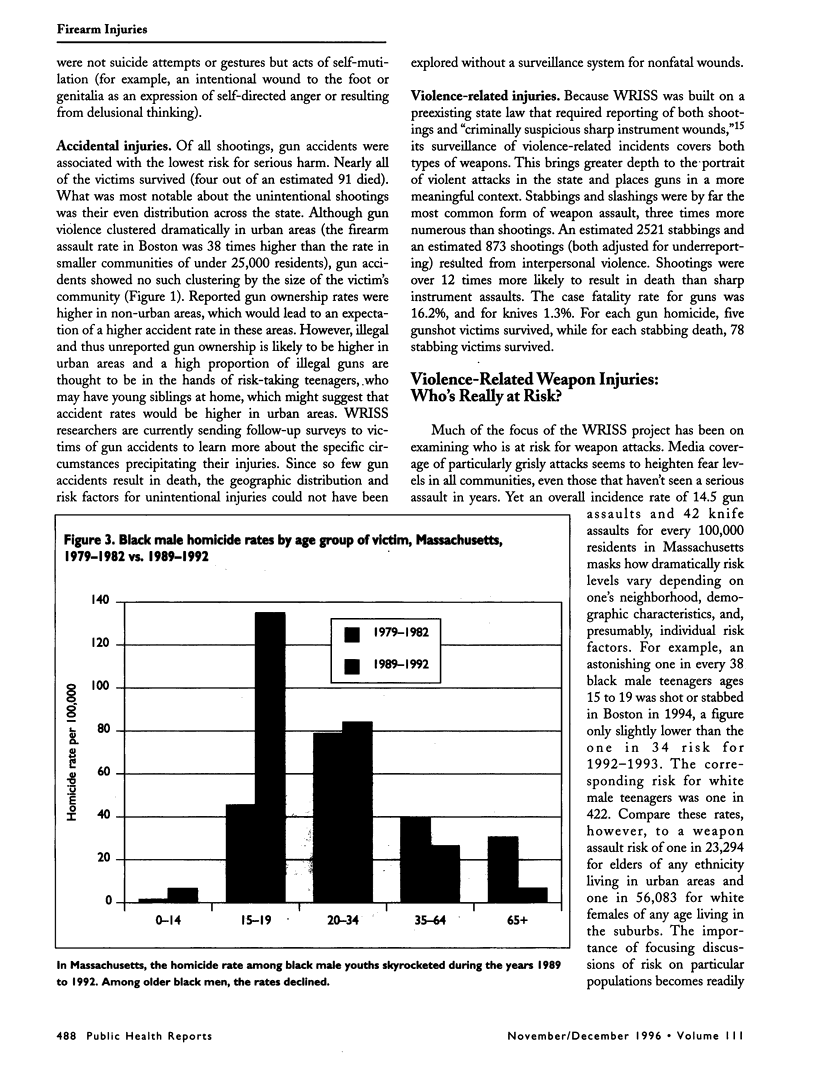

The Massachusetts Department of Public Health has created the first statewide surveillance system in the nation that tracks both fatal and nonfatal weapon injuries. The authors summarize findings for 1994 and discuss their public health implication. Suicides were the leading cause of firearm fatality, while self-inflicted injuries accounted for only 3% of nonfatal firearm injuries. Risk of violence-related injuries varied dramatically across the state. In Boston, one in 38 black male teenagers ages 15 to 19 was shot or stabbed in 1994, in contrast to one in 56,000 for white females of any age living in suburban communities. In Boston, non-Hispanic black male teenagers were at 41 times higher risk than white male teenagers for gun injuries. Shooting homicides increased sixfold during the late 1980s among black Boston males, while homicides by other means remained stable. In other Massachusetts cities, injury rates were higher among 20 to 24-year-olds than among teenagers, and, in some areas, incidence rates were as high or higher among Hispanic males than among non-Hispanic black males. Between 1985 and 1994, the proportion of firearm injuries caused by semiautomatic pistols increased from 23% to 52%, according to police ballistics data.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Annest J. L., Mercy J. A., Gibson D. R., Ryan G. W. National estimates of nonfatal firearm-related injuries. Beyond the tip of the iceberg. JAMA. 1995 Jun 14;273(22):1749–1754. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centerwall B. S. Race, socioeconomic status, and domestic homicide, Atlanta, 1971-72. Am J Public Health. 1984 Aug;74(8):813–815. doi: 10.2105/ajph.74.8.813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centerwall B. S. Race, socioeconomic status, and domestic homicide. JAMA. 1995 Jun 14;273(22):1755–1758. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fingerhut L. A., Ingram D. D., Feldman J. J. Firearm and nonfirearm homicide among persons 15 through 19 years of age. Differences by level of urbanization, United States, 1979 through 1989. JAMA. 1992 Jun 10;267(22):3048–3053. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fingerhut L. A., Ingram D. D., Feldman J. J. Firearm and nonfirearm homicide among persons 15 through 19 years of age. Differences by level of urbanization, United States, 1979 through 1989. JAMA. 1992 Jun 10;267(22):3048–3053. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins D. F. Inequality, culture, and interpersonal violence. Health Aff (Millwood) 1993 Winter;12(4):80–95. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.12.4.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jason J. Centers for Disease Control and the epidemiology of violence. Child Abuse Negl. 1984;8(3):279–283. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(84)90067-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellermann A. L., Lee R. K., Mercy J. A., Banton J. The epidemiologic basis for the prevention of firearm injuries. Annu Rev Public Health. 1991;12:17–40. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pu.12.050191.000313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee R. K., Waxweiler R. J., Dobbins J. G., Paschetag T. Incidence rates of firearm injuries in Galveston, Texas, 1979-1981. Am J Epidemiol. 1991 Sep 1;134(5):511–521. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeill A. M., Annest J. L. The ongoing hazard of BB and pellet gun-related injuries in the United States. Ann Emerg Med. 1995 Aug;26(2):187–194. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(95)70150-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]