Abstract

Cyclin-dependent kinase (Cdk)2/cyclin E is imported into nuclei assembled in Xenopus egg extracts by a pathway that requires importin-α and -β. Here, we identify a basic nuclear localization sequence (NLS) in the N-terminus of Xenopus cyclin E. Mutation of the NLS eliminated nuclear accumulation of both cyclin E and Cdk2, and such versions of cyclin E were unable to trigger DNA replication. Addition of a heterologous NLS from SV40 large T antigen restored both nuclear targeting of Cdk2/cyclin E and DNA replication. We present evidence indicating that Cdk2/cyclin E complexes must become highly concentrated within nuclei to support replication and find that cyclin A can trigger replication at much lower intranuclear concentrations. We confirmed that depletion of endogenous cyclin E increases the concentration of cyclin B necessary to promote entry into mitosis. In contrast to its inability to promote DNA replication, cyclin E lacking its NLS was able to cooperate with cyclin B in promoting mitotic entry.

INTRODUCTION

Cyclin-dependent kinases (Cdks) are vital for the initiation of both the major events of the eukaryotic cell cycle: the duplication of the genome in S phase and its segregation to two daughter cells during mitosis. In animal cells, several families of Cdks and cyclins have roles in cell cycle control. d-type cyclins complexed to Cdk4/Cdk6 regulate the decision to divide or differentiate, Cdk2/cyclin E and Cdk2/cyclin A collaborate to initiate the events of S phase, and Cdk/cyclin A and Cdk1/cyclin B combine forces to trigger the wholesale reorganization of cellular components at mitosis (Girard et al., 1991; Pagano et al., 1992; Ohtsubo et al., 1995; Furuno et al., 1999; Hu et al., 2001; Nigg, 2001).

Cdk/cyclin complexes are regulated by multiple mechanisms that ensure that they execute their functions at the correct time (Morgan, 1997); ubiquitylation and proteolysis of cyclins A and B are critical for M-phase exit (Wheatley et al., 1997; den Elzen and Pines, 2001; Geley et al., 2001), whereas defects in cyclin E proteolysis may be associated with certain cancers (Strohmaier et al., 2001). The subcellular localization of Cdk/cyclin complexes is also critical for faithful cell cycle control (Pines and Hunter, 1991; Hagting et al., 1998; Toyoshima et al., 1998; Pines, 1999; Alt et al., 2000; Draviam et al., 2001), and some progress has been made in identifying the mechanisms responsible, in particular those used by Cdk/cyclin complexes to shuttle between the cytoplasm and nucleus (Yang et al., 1998; Hagting et al., 1999; Moore et al., 1999; Takizawa et al., 1999). In this article, we focus attention on the mechanism and relevance of nuclear localization for the function of Cdk2/cyclin E in Xenopus egg extracts.

Xenopus egg extracts have proved useful for studying the functions of Cdk/cyclin complexes in cell cycle control. Extracts exhibit excellent synchrony and faithfully recapitulate both S-phase and M-phase processes in vitro. Moreover, it is possible to manipulate their contents by depletion or addition of proteins. Five reports using such methods have defined multiple roles of Cdk2/cyclin E in egg extracts. Cdk2/cyclin E is capable of providing all the Cdk activity necessary to support a single round of chromosomal DNA replication (Jackson et al., 1995; Strausfeld et al., 1996), plays a role in centrosome duplication (Hinchcliffe et al., 1999; Lacey et al., 1999), and is important for maintaining conditions permissive for cyclin B to activate Cdk1 and bring about mitosis (Guadagno and Newport, 1996). There are limits to the abilities of Cdk2/cyclin E, however, for it is unable to trigger entry into mitosis in the absence of other Cdk/cyclin complexes (Strausfeld et al., 1996), although a recent article claimed that it influenced the duration of M phase (D'Angiolella et al., 2001).

In egg extracts, as in other systems, Cdk2/cyclin E is strongly concentrated in nuclei (Hua et al., 1997). Cdk2/cyclin E is imported into nuclei via the conventional importin-α/β–dependent pathway (Moore et al., 1999). In this article, we define the sequences required for Cdk2/cyclin E to accumulate in egg extract nuclei and demonstrate that the concentration of this complex within nuclei is critical for its ability to support DNA replication. In contrast, the nuclear localization sequences (NLSs) of cyclin E are not necessary for Cdk2/cyclin E to lower the threshold concentration of Cdk1/cyclin B necessary to initiate entry into mitosis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Xenopus Egg Extracts and Replication Assays

Interphase egg extracts were prepared as previously described (Smythe and Newport, 1991); except where noted, cycloheximide (100 μg/ml) was added to prevent the synthesis of endogenous A-type and B-type cyclins. Cell cycle progression was monitored by removing 1-μl samples, mixing them 50:50 with 28% formaldehyde, 250 mM sucrose, and 10 mM HEPES-KOH, pH 8, containing 20 μg/ml Hoechst 33258, and examining the nuclear/chromatin morphology with a Zeiss Axioskop fluorescence microscope.

Egg extracts were depleted either by two incubations at 4°C with a 20% volume of Affiprep protein-A beads loaded with preimmune or anti-cyclin E antibodies (experiments in Figures 2 and 6) or by three incubations on ice with protein A-Dynabeads (Dynal, Oslo, Norway) loaded with preimmune or anti-cyclin E antibodies (the manufacturer's recommendations for bead/extract ratios were followed). Both depletion protocols removed almost all cyclin E, as judged by immunoblotting, but the Dynabead depletions caused less damage to the egg extract and enabled replication assays (see below) to be performed for shorter periods. For the experiment shown in Figure 5C, Cdk/cyclin complexes were depleted on Suc1p beads as previously described (Strausfeld et al., 1996).

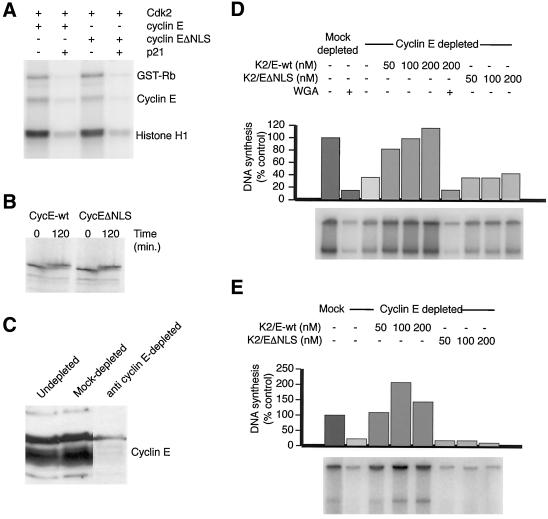

Figure 2.

Cdk2/cyclin EΔNLS complexes are active but unable to support DNA replication. (A) Cdk2/cyclin E and Cdk2/cyclin EΔNLS complexes have similar histone H1 and Rb kinase activities. Egg extracts were supplemented with 500 nM Cdk2-his and 500 nM of myc-cyclin E or myc-cyclin EΔNLS. After a 30-min incubation at room temperature, Cdk2/cyclin E complexes were recovered on 9E10-protein A beads and assayed for their ability to phosphorylate GST-Rb and Histone H1, in the absence and presence of the CDK inhibitor protein p21 (200 nM). Cyclin E autophosphorylation is also observed in this assay. (B) Both wild-type and NLS-deficient cyclin E are stable proteins in egg extracts. Interphase egg extracts were supplemented with sperm heads, an energy-regenerating system, and 1/20 volume of reticulocyte lysates programmed to produce [35S]methionine-labeled cyclin E or cyclin EΔNLS. After incubation for either 0 or 120 min at room temperature, samples were removed, boiled in loading buffer, and resolved by SDS-PAGE for autoradiography. The increase in the apparent molecular weight of cyclin E between the 0- and 120-min time points is a result of phosphorylation events that occur upon its binding to the endogenous Cdk2 in the egg extract. (C) Endogenous cyclin E can be removed from egg extracts by immunodepletion. Two rounds of depletion with anti-cyclin E-protein A beads removes almost all the egg extract's complement of cyclin E. Mock depletion with normal rabbit serum-protein A beads did not affect the concentration of cyclin E. (D and E) Cdk2/cyclin EΔNLS complexes are unable to support DNA replication. (D) Replication assays in which Cdk2/cyclin E was restored to depleted egg extracts after nuclear assembly. The indicated extracts were supplemented with 1000 sperm heads/μl, and α-[32P]dCTP and nuclear assembly was allowed to proceed for 40 min at room temperature. The indicated concentrations of Cdk2/cyclin E or Cdk2/cyclin EΔNLS proteins were then added. Some reactions were also supplemented with 1 mg/ml wheat germ agglutinin to block transport through nuclear pores. Reactions were stopped after 90 min at room temperature. (E) Replication assays in which Cdk2/cyclin E was restored to depleted egg extracts before nuclear assembly. The indicated concentrations of Cdk2/cyclin E or Cdk2/cyclin EΔNLS proteins were added back to depleted extracts, which were then incubated for 40 min at room temperature. Extracts were then supplemented with 1000 sperm heads/μl and α-[32P]dCTP. DNA replication was assayed after a further 2-h incubation at room temperature.

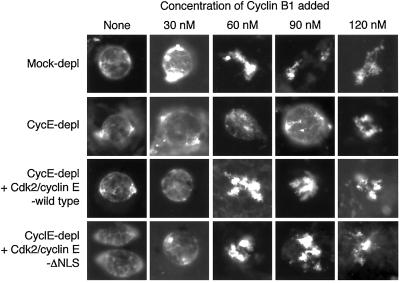

Figure 6.

Addition of Cdk2/cyclin EΔNLS complexes to cyclin E–depleted egg extracts restores the ability of cyclin B to trigger M-phase entry. Buffer or the indicated Cdk2/cyclin E complex were added to mock or anti-cyclin E–depleted extracts containing ∼500 nuclei assembled around sperm heads per microliter and 5 mM caffeine, then extracts were supplemented with the indicated concentration of cyclin B1. After 45 min, samples were withdrawn and fixed, and nuclear/chromatin morphology was examined by fluorescence microscopy.

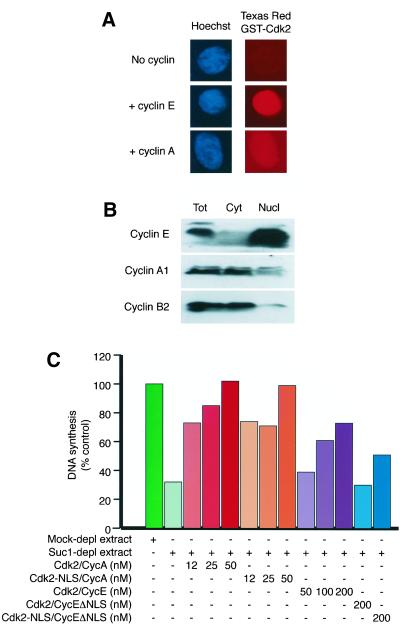

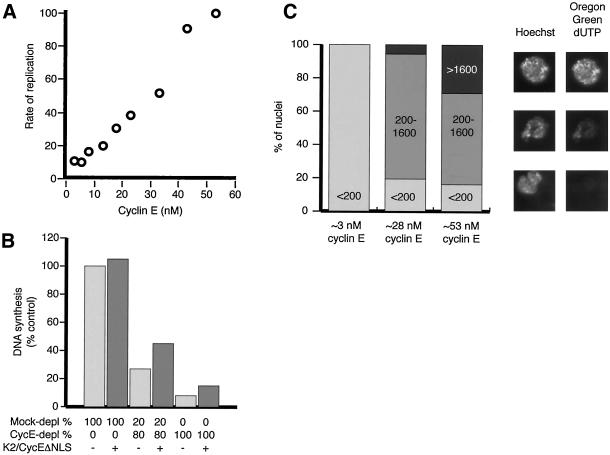

Figure 5.

Cyclin A does not accumulate to high concentrations in egg extract nuclei. (A) Comparison of the ability of cyclins E and A to promote the nuclear import of fluorescent Cdk2. Egg extracts containing ∼1000 nuclei assembled around sperm heads per microliter were supplemented with 200 nM Texas Red–labeled GST-Cdk2 ± 200 nM MBP-cyclin E or 200 nM his-cyclin A. After 45 min, samples were withdrawn, fixed, and examined by fluorescence microscopy for Hoechst-stained chromatin (blue) and GST-Cdk2 (red). (B) Cyclin E accumulates in egg extract nuclei, but cyclin A does not. Total (Tot), cytosolic (Cyt), and nuclear (Nucl) fractions of an egg extract containing 3500 nuclei/μl were separated by SDS-PAGE and blotted onto nitrocellulose. (Note that protein synthesis was permitted in this experiment by omitting cycloheximide during the preparation of the egg extract.) Blots were probed with antibodies against endogenous cyclin E, cyclin A1, or cyclin B2. The greater signal in the nuclear vs. the total fraction of cyclin E demonstrates its dramatic concentration in nuclei; similarly, the minimal signal in the nuclear fraction for cyclin B2 demonstrates its nuclear exclusion. No hints of mitosis were observed in this experiment. (C) Low nuclear concentrations of Cdk2/cyclin A support DNA replication in Xenopus egg extracts. Egg extracts were subjected to two rounds of depletion on either BSA-Sepharose beads (Mock-depl extract) or Suc1p-Sepharose beads (Suc1-depl extract). Extracts were supplemented with ∼1000 sperm heads/μl, α-[32P]dCTP, and a range of concentrations of GST-Cdk2 or GST-Cdk2-NLS complexed to MBP-cyclin E, MBP-cyclin EΔNLS, or cyclin AΔ170. Nuclear assembly and DNA replication were allowed to proceed for 60 min at room temperature before reactions were stopped and DNA synthesis was quantified.

Kinase assays were performed in a buffer containing 50 mM sodium β-glycerophosphate, 5 mM NaF, 15 mM MgCl2, 3 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 3 mM EDTA, 100 μM ATP, and 0.25 mg/ml Histone H1 (some assays also contained 0.1 mg/ml GST-Rb). Assays spiked with 0.01 vol of 10 μCi/μl γ-[32P]ATP were incubated for 5 min at room temperature and stopped by addition of SDS-PAGE loading dye. Proteins were separated by 15% SDS-PAGE, and incorporation of radioactivity into Histone or GST-Rb was quantified on a phosphorimager.

A method adapted from Jackson et al. (1995) was used for replication assays; extracts were supplemented with 1:200 vol of α-[32P]dCTP (10 μCi/μl), and samples were removed at the times indicated, diluted 10-fold with Replication Stop buffer (20 mM Tris-Cl, 20 mM EDTA, 0.5% SDS, pH 8), and flash-frozen in liquid N2. Subsequently, thawed samples were mixed with an equal volume of 2 mg/ml Protease K in Replication Stop buffer, incubated for 2–3 h at 37°C, then loaded onto 1% TAE-agarose gels. After electrophoresis to separate unincorporated nucleotides, gels were dried and new DNA synthesis was measured on a phosphorimager. Data are presented from time points that combine an easily detectable signal with maximum differentiation between mock and cyclin E depleted extracts. Typically, this occurred at time points when DNA synthesis in the mock-depleted extract had reached ∼50% of the final value.

To assay replication at the level of individual nuclei, extracts were also supplemented with 1:100 volumes of 1 mM Oregon Green dUTP (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). Nuclei were separated from extracts by diluting samples fivefold in extract buffer (10 mM HEPES-KOH, pH 7.7, 50 mM KCl, 250 mM sucrose, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT), underlaying the diluted samples with a cushion of extract buffer containing 0.5 M sucrose, and spinning at 3000 × g at 4°C for 5 min. The extract supernatant and cushion were removed by aspiration, and the nuclear pellet was resuspended in the Hoechst-supplemented fixative described above and pipetted onto slides for microscopy. Images in the green and blue channels were captured with Improvision's OpenLab software and quantified.

The partitioning of cyclins between nuclei and cytoplasm was assessed by a protocol adapted from that of Walter et al. (1998). Interphase extracts prepared in the absence of cycloheximide were supplemented with 10 μM nocadazole and respun at 10,000 × g at 4°C for 10 min, and the straw-colored extract layer was removed by side puncture. This extract was supplemented with an energy regeneration system, 3500 sperm heads/μl and 50 μg/ml aphidicolin, to prevent entry into mitosis (Dasso and Newport, 1990). Cyclin synthesis and import into the nuclei assembled around sperm heads were allowed to proceed for 80 min. An aliquot of the reaction was removed (total sample) before centrifugation at 10,000 × g at 4°C for 4 min was used to bring nuclei to the top of the tube. Nuclei-enriched and cytosolic aliquots were withdrawn and, along with the unfractionated aliquot, were boiled in 10 vol of SDS-PAGE loading dye.

The stability of cyclin E in extracts was determined by adding 1/20 volume of rabbit reticulocyte lysate programmed with pEspB-CycE-his or pEspB-CycEΔNLS-his (see below) to a cycloheximide-supplemented egg extract containing 1000 sperm heads/μl. Samples were withdrawn either immediately or after the indicated time and boiled in 10 vol of SDS-PAGE loading dye before separation on 12.5% gels and autoradiography.

Antibodies

Samples for immunoblotting were separated by 12.5% SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Anti-Xenopus cyclin B2 (X121) and anti-Xenopus cyclin A1 (DH1) monoclonal antibodies were generated by Julian Gannon and Dolores Harrison, respectively (Cancer Research UK–Clare Hall). Rabbit polyclonal antibodies raised against the N-terminal 144 amino acids of Xenopus cyclin E were described by Strausfeld et al. (1996). Cdk2 was detected by use of a monoclonal antibody directed against the PSTAIRE epitope. Rabbit polyclonal antibodies against importin-α and importin-β were a kind gift of Dirk Görlich (University of Heidelberg). Secondary antibodies (swine anti-rabbit and goat anti-mouse horseradish peroxidase) were obtained from Dako (Glostrup, Denmark), and signals were detected by enhanced chemiluminescence.

Plasmids

The original pGEX-cyclin E plasmid encoding the GST-Xenopus cyclin E fusion protein used in the initial experiments (Figure 1, A and B) has been described previously (Moore et al., 1999). Digestion of pGEX-cyclin E with NcoI, followed by Klenow treatment and self-ligation, yielded pGEX-cyclin E-NT, which encodes a GST-cyclin E (1–60) fusion protein. Digestion of pGEX-cyclin E with BamHI and NcoI, followed by Klenow treatment and self-ligation, produced pGEX-cyclin E (60–409), which encodes a GST-cyclin E (60–409) chimeric protein.

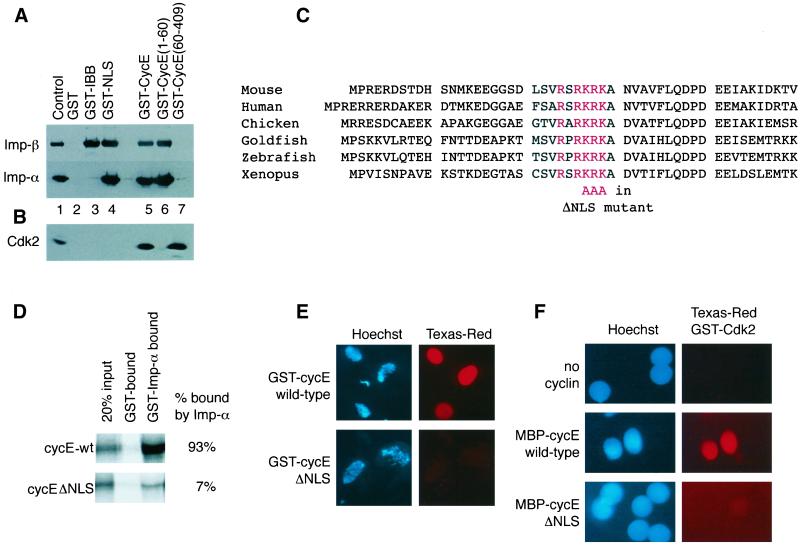

Figure 1.

The N-terminus of cyclin E contains a basic NLS. (A and B) The N-terminus of cyclin E is required for importin binding but dispensable for Cdk2 binding. Glutathione Sepharose beads loaded with the proteins indicated were incubated with a mixture of importin-α and importin-β (A) or with interphase egg extract (B) at 4°C for 40 min. Proteins retained on the beads after washing were separated by SDS-PAGE along with 10% input control in lane 1. Immunoblots were probed with anti-importin-α and -β antibodies or anti-Cdk2 antibodies. (C) Amino acid sequence alignment of the N-terminal regions of six vertebrate cyclin E1 proteins. The conserved NLS is shown in red. (D) Mutation of the basic NLS sequence of cyclin E impairs binding to importin-α. Rabbit reticulocyte lysates containing [35S]methionine-labeled cyclin E or cyclin EΔNLS were diluted fivefold (final protein concentration, 10 mg/ml), then incubated with either GST- or GST-importin-α–loaded beads. Beads were pelleted and washed in buffer, and the bound radiolabeled proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE for detection by autoradiography. One-fifth the amount of supplemented extract used in the binding assay was loaded onto the gel as a control. (E) Mutation of the putative NLS prevents cyclin E accumulating in egg extract nuclei. GST-cyclin E proteins labeled with 200 nM Texas Red were added to egg extracts containing ∼1000 nuclei assembled around sperm heads per microliter. To assess import, samples were withdrawn after 30 min, fixed, and examined by fluorescence microscopy for Hoechst-stained chromatin (blue) and GST-cyclin E (red). (F) Cyclin EΔNLS is unable to target Cdk2 to nuclei. Egg extracts containing ∼1000 nuclei/μl were supplemented with 300 nM Texas Red–labeled GST-Cdk2 ± 300 nM MBP-cyclin E or MBP-cyclin EΔNLS. Import was assessed after 10 min. Signal in the red channel indicates the localization of GST-Cdk2.

New GST-cyclin E encoding plasmids were constructed with the pGEX-PP-his backbone, a modified version of pGEX-6P-1 (Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden), with the addition of sequences encoding a second 3C protease cleavage site, followed by a 6-his tag for purification 3′ to the XhoI site in the multiple cloning site. pGEX-PP-his was made by digesting pGEX-6P-1 with EcoRI and NotI and ligating in a double-stranded linker comprising the annealed oligo pair 5′-AATTCCCGGGTCGACTCGAGGTACTATTCCAAGGACCTCATCACCATCATCATCATTAAGC-3 and 5′-GGCCGCTTAATGATGATGGTGATGAGGTCCTTGGAATAGTACCTCGAGTCGA-CCCGGG-3′. Proteins encoded by sequences cloned into pGEX-PP-his in the correct reading frame can be purified by sequential affinity chromatography on glutathione agarose and Ni2+-NTA-agarose. Sequences encoding an N-terminally myc-tagged cyclin E sequence were amplified from the template pEspB-CycE (Bartosch, 1999) by means of PCR using the oligo pair 5′-CCCGGGGGATCCGATCCTATGGAGCAAAAGCTCATTTCT-3′ and 5′-GATGCAGTCCTCGAGGTCTGCTCGATCAGATTTCTG-3′, digested with BamHI and XhoI, and ligated to BamHI/XhoI-cut pGEX-PP-his to yield pGEX-myc-Cyclin E. A variant, pGEX-myc-Cyclin EΔNLS, was made by the method of Horton and Pease (1991): the BamHI/NcoI fragment encoding the N-terminal 60 amino acids of cyclin E was replaced with PCR-derived sequences in which the oligo pair 5′-TGTAGTGTGCGCTCCAGAGCTGCTGCTGCAGATGTGACTATTTTC-3′ and 5′-GAAAATAGTCACATCTGCAGCAGCTCTGGAGCGC-ACACTACA-3′ had been used to mutate the nucleotides encoding RSRKRK (residues 24–29 of Xenopus cyclin E) to those encoding RSRAAA. All PCR-derived constructs were verified by sequencing both strands.

Plasmids to express myc-cyclin E-6-his and the ΔNLS derivative in coupled in vitro transcription/translation reactions were also constructed. pEspB-CycE-his was made by replacing the non 6-his-tagged cyclin E sequence in pEspB-CycE (released by successive treatment with HindIII, Klenow enzyme, and BglII) with the fragment encoding myc-cyclin E-6-his liberated from pGEX6P-myc-Cyclin E by treatment with NotI, Klenow enzyme, and BglII. pEspB-CycEΔNLS-his was made by replacing the BglII-XhoI fragment encoding wild-type cyclin E with the corresponding sequence from pGEX-myc-Cyclin EΔNLS.

Plasmids encoding MBP-tagged cyclin E and cyclin EΔNLS were made by ligating BamHI/Klenow-treated NotI fragments encoding the myc-Cyclin E-6-his sequences into BamHI/Klenow-treated HindIII-cut pMalC2. A plasmid encoding MBP-tagged cyclin E (60–409) was generated by digesting pMalC2-cyclin E with BamHI and NcoI followed by Klenow treatment and self-ligation. pET21d-Cyclin A3 encodes a truncated version of bovine cyclin A (here called cyclin AΔN170, equivalent to residues 171 to the C terminus of human cyclin A2) linked in frame to a 6-his tag at the C terminus (Brown et al., 1995). pET21d-Cdk2 was constructed by Mike Howell and encodes a C-terminally 6-his–tagged Xenopus Cdk2 protein. pGEX-Cdk2 was constructed by Katsumi Yamashita (backbone pGEX-KG) and encodes a GST-human Cdk2 fusion protein. pGEX-importin-α and pGEX-importin-β encode chimeric proteins linking GST to Xenopus importin-α and human importin-β, respectively, and have been described previously (Moore et al., 1999), as have pGEX-IBB and pGEX-NLS, which encode controls for the importin binding assays (Rexach and Blobel, 1995; Moore et al., 1999). pGEX-Rb encodes a chimeric protein comprising GST fused to the pocket domain of the human retinoblastoma protein (residues 372–928) and has been described previously (Kaelin et al., 1991).

Protein Production and Labeling with Fluorescent Tags, Nuclear Import, and Import Factor–Binding Assays

The cyclin B used in this work was purified by chromatography on Ni2+-NTA agarose as described previously (Kumagai and Dunphy, 1995) from Sf9 cells grown at 27°C for 48 h after infection with a baculovirus encoding a 6-his 4-myc–tagged version of human Cyclin B1 (Takizawa et al., 1999). The N-terminal myc tags make this protein effectively nondegradable in egg extracts (Jin et al., 1998). Full-length 6-his–tagged human cyclin A2, as used in the experiment reported in Figure 5A, was similarly expressed in Sf9 cells by use of a baculoviral construct provided by David Morgan (University of California, San Francisco) and purified on Ni2+-NTA agarose. More generally, protein production was performed in Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3) “Codon Plus” cells, inducing cultures grown at room temperature with IPTG overnight. Shorter inductions at 37°C were possible for unfused GST and the control proteins for the importin binding assays.

Proteins were purified by affinity chromatography, taking advantage of the GST, MBP, or 6-his fusion tags in accordance with standard procedures, and concentrated in Vivaspin ultrafiltration units. It was necessary to remove aggregates from MBP-cyclin E preparations by ultracentrifugation (250,000 × g, 30 min, at 2°C). Importin-α and importin-β were liberated from their GST fusion tag by treatment with thrombin, while the GST moiety was bound to glutathione-agarose beads. Similarly, the cyclin E proteins used in our early add-back experiments (Figure 2) were liberated from their GST fusion tags by treatment with 3C protease. Uncleaved MBP-cyclin E and GST-Cdk2 were used for subsequent experiments (Figures 3, 4, 5, and 7), except that uncleaved GST-cyclin E proteins were used for the work presented in Figure 6. All proteins were dialyzed against storage buffer (20 mM HEPES-KOH, pH 7.75, 100 mM KCl, 200 mM sucrose, 2 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT), divided into small aliquots, and flash-frozen in liquid N2.

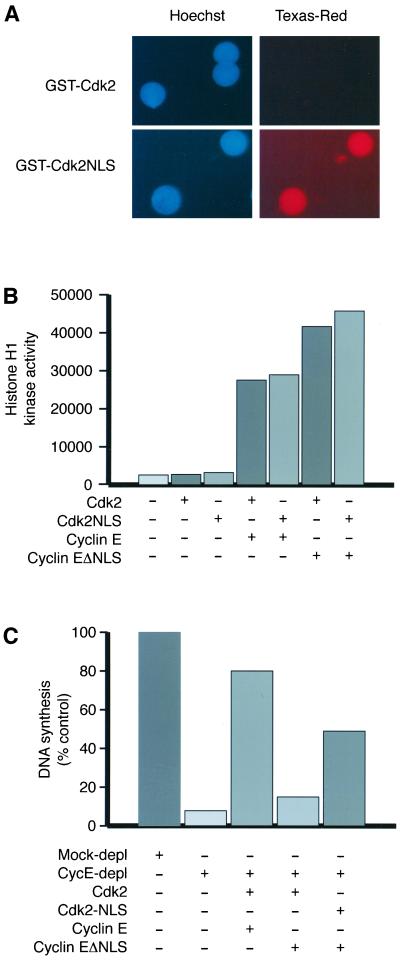

Figure 3.

The replication-promoting properties of Cdk2/cyclin EΔNLS can be restored by addition of an NLS in trans. (A) Fusion of a basic NLS to the C-terminus of Cdk2 allows its cyclin-independent nuclear import. Egg extracts containing ∼1000 nuclei/μl were supplemented with 300 nM Texas Red–labeled GST-Cdk2 or GST-Cdk2NLS. After 10 min, samples were fixed and examined by fluorescence microscopy for Hoechst-stained chromatin (blue) and GST-Cdk2 (red). (B) Cyclin E activates the histone H1 kinase activity of Cdk2 and Cdk2-NLS equally. Interphase egg extracts were depleted twice on Suc1p-Sepharose beads to remove endogenous Cdk/cyclin complexes (see Strausfeld et al., 1996), then supplemented with the proteins indicated (final concentrations, 200 nM). After 30 min at room temperature, aliquots were flash-frozen, then thawed and assayed for Histone H1 kinase activity. The unit on the plot is arbitrary. (C) Cdk2-NLS/cyclin EΔNLS complexes support DNA replication. The indicated GST-Cdk2 or MBP-cyclin E proteins (final concentration, 100 nM), along with 1000 sperm heads/μl and α-[32P]dCTP, were added to extracts that had depleted on either preimmune or anti-cyclin E–loaded protein A Dynabeads. Nuclear assembly and DNA synthesis were allowed to proceed for 45 min before reactions were stopped and DNA synthesis was quantified.

Figure 4.

High concentrations of Cdk2/cyclin E within nuclei are necessary to support DNA replication. (A) Dependence of replication rates on the initial concentration of cyclin E. Mixtures of mock and cyclin-E–depleted extracts were supplemented with α-[32P]dCTP and 1000 sperm heads/μl. DNA synthesis was determined after 60 min of incubation and plotted (in arbitrary units) against the estimated concentration of cyclin E (see text). (B) Excess Cdk2/cyclin EΔNLS does not restore the replication defect in extracts containing limiting concentrations of wild-type Cdk2/cyclin E. Buffer or 100 nM GST-Cdk2/MBP-cyclin EΔNLS was added as indicated to mock-depleted, cyclin E–depleted, or a 1:4 mixture of the extracts. Samples were withdrawn from the reactions 45 min after the addition of sperm heads, and α-[32P]dCTP and DNA synthesis was quantified. (C) Replication is at least partially triggered in the great majority of nuclei assembled in egg extracts containing reduced concentrations of cyclin E. Mock-depleted extract, cyclin E–depleted extract, and a 50:50 mixture of the two were supplemented with α-[32P]dCTP, 10 μM Oregon Green dUTP, and 1000 sperm heads/μl. After 60 min of incubation at room temperature, DNA synthesis was quantified as before, and nuclei were also isolated and examined by fluorescence microscopy. Estimates of the ratios of the amount of replication that occurred in the three extracts derived both from measuring incorporation of radiolabel and from the mean Oregon Green fluorescence observed in the 30–40 nuclei from each condition examined were similar and consistent with those observed in A. Nuclei were allocated to one of three categories: low fluorescence (1600 arbitrary units, half the value of the strongest signal detected in nuclei from the mock-depleted extract). The percentage of low, medium, and highly labeled nuclei observed for each condition are plotted on the graph on the left. Hoechst and Oregon Green signals from sample nuclei exhibiting each level of fluorescence are shown at right.

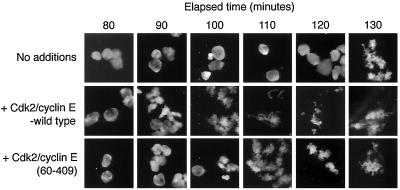

Figure 7.

Excess Cdk2/cyclin E activity accelerates entry into mitosis in cycling extracts. Protein-synthesis-competent interphase egg extracts (cycling extracts) were supplemented with an energy-regenerating system and 500 sperm heads/μl, then incubated at room temperature. After 50 min, either buffer, GST-Cdk2/MBP-cyclin E, or GST-Cdk2/MBP-cyclin EΔN60 were added to final concentrations of 0.6 or 1 μM, respectively. Samples were withdrawn at the indicated times and fixed, and nuclear/chromatin morphology was then examined by fluorescence microscopy.

For nuclear import experiments, portions of GST-cyclin E, GST-cyclin EΔNLS, and GST-Cdk2 were labeled with Texas Red maleimide C2 (Molecular Probes) by mixing between 1:1 and 1:5 ratios of protein and dye in PBS and incubating at room temperature in the dark for 2 h. Reactions were quenched by addition of 10 mM DTT, and the labeled proteins were dialyzed against storage buffer. Demembranated sperm chromatin (1000 nuclei/μl) was added to interphase Xenopus egg extract. After nuclei had been allowed to assemble for 40–60 min, ∼200 nM Texas Red–labeled protein was added and the extracts were incubated at room temperature for the time indicated. Aliquots were withdrawn, mixed with Hoechst 33258-containing fixative, placed on slides, and examined by fluorescence microscopy.

Binding assays using immobilized GST-NLS or GST-Cyclin E proteins and soluble importins α and β were performed as previously described (Moore et al., 1999); the concentration of each importin subunit was 100 μg/ml. For assays using Xenopus egg extract as a source of Cdk2, extract was diluted 10-fold before addition to beads. Beads were washed 4 times with PBS plus 10 mg/ml cas-amino acids plus 0.1% Tween-20 and 2 times in PBS before analysis by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting. Binding assays using immobilized GST-importin-α and in vitro–translated 35S-labeled cyclin E were performed as previously described (Moore et al., 1999).

RESULTS

Xenopus Cyclin E Contains an N-Terminal Basic NLS That Is Conserved in Many Vertebrate Cyclin E Sequences

We previously showed that Xenopus Cdk2/cyclin E complexes are imported into egg extract nuclei via the conventional importin-α/β–dependent pathway (Moore et al., 1999). The interaction between the importin heterodimer and the Cdk2/cyclin E complex occurs via a direct interaction between importin-α and cyclin E (Moore et al., 1999). These data suggested that cyclin E possesses a basic NLS. Xenopus cyclin E contains the sequence RSRKRK between residues 24 and 29, which is a possible candidate. Chimeric proteins comprising residues 1–60 or 60–409 of cyclin E or full-length cyclin E fused to GST were produced in E. coli and purified on glutathione-Sepharose beads. As controls, GST and two GST-NLS proteins (see MATERIALS AND METHODS) were also expressed in bacteria.

In solution binding assays, the control proteins exhibited the expected associations with importin-α and -β. Figure 1A shows that unfused GST did not bind importins (lane 2), whereas GST-IBB (containing the importin-β binding sequences from importin-α) associated only with importin-β (lane 3). GST-NLS (containing the basic NLS from the SV40 large T antigen) beads retained both the α and β subunits of the importin heterodimer (lane 4), as did full-length GST-cyclin E (lane 5). Figure 1B shows that GST-cyclin E bound Cdk2 from egg extracts. GST-Cyclin E (60–409) retained the ability to bind Cdk2 but was unable to associate with importin (lane 7). Conversely, the GST-cyclin E (1–60) protein was able to bind to importin as efficiently as the full-length protein (lane 6) but was not associated with Cdk2 (Figure 1A).

The sequence RSRKRK was reminiscent of a validated NLS (sequence KSRKRKL) in the v-jun protein (Chida and Vogt, 1992) and is conserved in all known examples of vertebrate cyclin E1 (see Figure 1C for an alignment of the N-termini of cyclin E1 from various vertebrate species). Mutation of the sequence encoding residues 27–29 from KRK to AAA dramatically reduced the amount of in vitro–translated cyclin E that was captured on immobilized GST-importin-α (Figure 1D). Wild-type and ΔNLS cyclin E (containing the KRK to AAA mutation) proteins were expressed as GST and MBP fusions in bacteria. The GST-cyclin E proteins were labeled with Texas red and tested for nuclear accumulation in frog egg extracts. Although Texas Red–labeled GST-cyclin E accumulated rapidly in egg extract nuclei, GST-cyclin EΔNLS did not. Even 30 min after addition of labeled protein, little if any of the fusion protein could be detected in the nuclei (Figure 1E). We also tested the ability of MBP-cyclin E and MBP-cyclin EΔNLS to drive the import of Texas Red-labeled GST-Cdk2 into nuclei (Figure 1F). Because of the lack of free cyclins in egg extracts, Texas Red GST-Cdk2 remains cytoplasmic if added alone, but the complex with MBP-cyclin E is rapidly imported into nuclei (significant accumulation is observed within 3 min). In contrast, MBP-cyclin EΔNLS was unable to support the nuclear accumulation of GST-Cdk2 (Figure 1F). These data indicate that residues 27–29 of Xenopus cyclin E form an essential part of the NLS used by the Cdk2/cyclin E complex in frog egg extracts.

Cdk2/Cyclin EΔNLS Complexes Are Unable to Support Chromosomal DNA Replication

Cyclin EΔNLS consistently activated the histone H1 and GST-Rb kinase activities of Cdk2 to ∼80% of the level achieved by the same concentration of wild-type cyclin E (Figure 2A). The ΔNLS mutant complex therefore had no major defect in phosphorylating canonical substrates in vitro. Like the wild-type protein, the NLS-mutant cyclin E was very stable in Xenopus egg extracts. No degradation of 35S-labeled cyclin E or cyclin EΔNLS protein was observed during a 2-h incubation in interphase extracts containing 1000 nuclei/μl (Figure 2B). To establish how the cyclin EΔNLS mutant performed in more physiological settings, in particular its ability to promote the onset of S phase, we removed endogenous Cdk2/cyclin E complexes from extracts of activated Xenopus eggs by immunodepletion on immobilized anti-cyclin E antibodies (Figure 2C). As reported previously (Jackson et al., 1995; Strausfeld et al., 1996), this treatment severely reduced the amount and rate of DNA synthesis observed (see below).

In our first experiments, we permitted nuclei to assemble before adding back Cdk2/cyclin E complexes, mimicking the situation that would occur at the G1/S transition in mammalian cells. Sperm heads and α-[32P]dCTP were added to cyclin E-depleted egg extracts, and nuclear assembly was allowed to proceed for 40 min. Extracts were then supplemented with 50, 100, or 200 nM recombinant Cdk2/cyclin E or Cdk2/cyclin EΔNLS complexes; the endogenous concentration of cyclin E is 50–60 nM (Rempel et al., 1995). Assays were stopped 90 min after Cdk/cyclin addition, and DNA synthesis was assessed by agarose gel electrophoresis and autoradiography (Figure 2D). The wild-type cyclin E complexes complemented the replication defect in a depleted egg extract in a dose-dependent manner, but Cdk2/cyclin EΔNLS failed to restore replication. Addition of the nuclear import inhibitor wheat germ agglutinin (at 1 mg/ml) along with wild-type Cdk2/cyclin E prevented restoration of replication. These data indicate that Cdk2/cyclin E must gain access to the nuclear compartment to promote initiation of replication.

In the cell cycles of Xenopus egg extracts, like those of the early embryo they recapitulate, Cdk2/cyclin E activity is present continuously, its activity oscillating only modestly from a high in early mitosis to a low in early interphase (Gabrielli et al., 1992; D'Angiolella et al., 2001). Chromatin is therefore exposed briefly to cytoplasmic Cdk2/cyclin E every time the nuclei start to assemble after the end of mitosis. We asked whether Cdk2/cyclin EΔNLS could promote replication if it was present during this window. A range of concentrations of Cdk2/cyclin E or Cdk2/cyclin EΔNLS were added back to cyclin E–depleted egg extracts that were incubated for 40 min before addition of demembranated sperm chromatin. Replication was assayed 2 h later. As before, wild-type Cdk2/cyclin E complexes efficiently complemented the replication defect of depleted extracts, whereas Cdk2/cyclin EΔNLS complexes did not (Figure 2E). Exposure of chromatin to Cdk2/cyclin E before nuclear assembly is therefore not sufficient to trigger DNA replication.

Fusing an NLS to Cdk2 Enables Replication to Be Driven by Cdk2/Cyclin EΔNLS Complexes

The data above do not exclude the possibility that the NLS-like sequence in cyclin E plays a direct role in substrate recognition as well as in nuclear targeting for the Cdk2/cyclin E complex. We therefore asked whether restoring NLS function to Cdk2/cyclin EΔNLS complexes in trans could restore replication competence. A mutant GST-Cdk2 protein in which the basic NLS from the SV40 large T antigen (sequence TPPKKKRKVEDPE) (Kalderon et al., 1984) had been fused to the C terminus of Cdk2 was expressed in E. coli and purified. Addition of the T-antigen NLS enabled Texas Red–labeled GST-Cdk2 to accumulate in egg extract nuclei without coaddition of cyclins (Figure 3A), and complexes containing Cdk2-NLS and cyclin E were able to phosphorylate histone H1 to the same extent as wild-type Cdk2/cyclin E (Figure 3B).

We tested the ability of Cdk2-NLS/cyclin EΔNLS in the replication assay. Figure 3C shows that although very little replication was restored by addition of 100 nM Cdk2/cyclin EΔNLS, a similar concentration of Cdk2-NLS/cyclin EΔNLS was able to support considerably more replication, although never to quite the same levels as the wild-type proteins (Figure 3C). These experiments strongly suggest that nuclear localization of Cdk2/cyclin E is important for promoting the onset of DNA replication and that the main role of the RSRKRK sequence is to promote the entry of cyclin E into the nucleus.

Estimating the Minimum Nuclear Concentration of Cdk2/Cyclin E Required to Support Initiation of Replication

In Xenopus egg extracts supplemented with chromatin, the 60 nM of Cdk2/cyclin E that is initially distributed throughout an extract becomes concentrated within the assembling nuclei, reaching local levels of perhaps 12 μM (Hua et al., 1997). The results presented above show that the complex must have access to chromatin after nuclear assembly for DNA replication to occur. To test what concentration of Cdk2/cyclin E within nuclei was necessary to trigger DNA replication, various ratios of cyclin E–depleted and mock-depleted egg extracts were mixed to vary the cyclin E concentration. In control experiments performed with extracts supplemented with 35S-labeled cyclin E, the mock-depletion protocol removed 13% and the anti-cyclin E antibodies 95% of cyclin E. Therefore, we could vary the concentration of cyclin E over a range between ∼3 and 55 nM. Demembranated sperm heads and α-[32P]dCTP were added to the extracts, and the DNA synthesis that occurred in the first 60 min after sperm addition was measured (Figure 4A). There was a roughly linear relationship between the concentration of cyclin E and the amount of replication. Thus, the full complement of cyclin E is required for replication to occur at normal rates.

Several models can account for this result. First, the reduced nuclear concentrations of Cdk2/cyclin E in depleted egg extracts may slow the rate at which replication origins are fired. Second, the defect might arise from a more general Cdk/cyclin deficit, enabling an opposing activity (e.g., a phosphatase or stoichiometric inhibitor) to block replication. Finally, the limited Cdk2/cyclin E available might be concentrated in a subset of nuclei (for example, in those that assembled most quickly), thereby restricting the maximum amount of replication that could occur.

We first asked whether the replication defect in partially depleted egg extracts could be restored by the addition of excess Cdk2/cyclin EΔNLS. Buffer or 100 nM Cdk2/cyclin EΔNLS was added to either a mock-depleted extract, a cyclin E–depleted extract, or a mixture (1:4) of the two, along with demembranated sperm heads and α-[32P]dCTP. Reactions were stopped 45 min after sperm addition, and DNA synthesis was assayed. Cdk2/cyclin EΔNLS did not stimulate the initial rate of replication in the mock-depleted extract and only slightly increased replication in the cyclin E–depleted extracts (Figure 4B). This suggests that it is the nuclear concentration of Cdk2/cyclin E that determines the rate of replication. In contrast, Cdk2/cyclin EΔNLS was able to overcome a replication block imposed by adding the physiological Cdk inhibitor Xic1 to egg extracts (data not shown). The decreased replication observed when the concentration of cyclin E is reduced is thus unlikely to arise, because a Cdk inhibitor present in the extracts binds and inactivates the remaining endogenous Cdk2/cyclin E.

If the limited Cdk2/cyclin E available in partially depleted egg extracts had become sequestered in a small fraction of nuclei, then we would anticipate that the nuclei containing cyclin E would replicate normally, whereas those lacking cyclin E would not replicate at all. To examine this possibility, we supplemented mock-depleted, cyclin E–depleted, and a 1:1 mixture of the two extracts, with 10 μM Oregon Green dUTP, α-[32P]dCTP, and demembranated sperm heads. DNA synthesis in both the extract as a whole and individual nuclei was quantified after a 60-min incubation (Figure 4C). The fraction of nuclei that showed strong Oregon Green fluorescence (defined as at least 50% of the maximum observed in any nucleus) was reduced from 28% in the mock-depleted to 7% in the semidepleted extract. However, >80% of the nuclei in both the mock-depleted and semidepleted extract showed greater incorporation of Oregon Green–labeled nucleotide into chromosomal DNA than any nucleus examined in the cyclin E–depleted egg extract.

It was not possible to establish the proportion of nuclei in partially depleted extracts that contained endogenous cyclin E because of the insensitivity of our anti-cyclin E antibodies. Instead, we examined the localization of added Texas Red–labeled GST-cyclin E (25 nM) by fluorescence microscopy in cyclin E–depleted extracts. Texas Red–labeled cyclin E could be detected in 85% of nuclei (55 of 64; data not shown). Thus, even when Cdk2/cyclin E was present at limiting concentrations, it accumulated and triggered replication in the majority of nuclei. These data suggest that the rate of origin firing in all nuclei is reduced when the levels of cyclin E are reduced.

Together, these data strongly suggest that high nuclear concentrations of Cdk2/cyclin E are required for the efficient initiation of DNA replication. Reducing nuclear Cdk2/cyclin E concentrations fivefold (e.g., from 10 to 2 μM) reduces the initial rate of replication by ∼80%. We estimate that 3–6 μM Cdk2/cyclin E within nuclei is needed for replication to proceed at ∼50% of the normal rate.

Cdk/Cyclin A Does Not Become Concentrated within Nuclei in Xenopus Egg Extracts

A-type cyclins are able to complement the replication defect in cyclin E–depleted extracts (Jackson et al., 1995; Strausfeld et al., 1996). Indeed, when Cdk2/cyclin E and Cdk2/cyclin A complexes purified from baculovirus-infected insect cells were compared in their abilities to restore replication, cyclin A–containing complexes were considerably more potent than those containing cyclin E (Strausfeld et al., 1996). Does cyclin A also have to accumulate in the nucleus to promote replication? Somewhat surprisingly, little information is available on how A-type, or indeed B-type, cyclins became distributed between the nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions of egg extracts.

To address this question, we compared the ability of MBP-tagged cyclin E and his-tagged human cyclin A protein to promote the accumulation of Texas Red–labeled GST-Cdk2 in egg extract nuclei. Cyclin A proved to be markedly less efficient at targeting GST-Cdk2 to the nucleus than was MBP-cyclin E, although Figure 5A shows a slight increase in the amount of GST-Cdk2 localizing to nuclei in the presence of cyclin A. This was not because of reduced binding of cyclin A to the Cdk2, because cyclin A strongly activated the histone H1 kinase activity of the Texas Red–labeled GST-Cdk2 preparation (data not shown). It is possible that the Texas Red labeling procedure had a greater inhibitory effect on the import of Cdk2/cyclin A than Cdk2/cyclin E, because the import pathways appear to be different for the two cyclins (Jackman et al., 2002). We therefore tested whether endogenous newly synthesized cyclin A was imported into nuclei. We used a protocol for the rapid separation of nuclei from cytosol that relies on the high buoyancy of nuclei in egg extracts prepared by low-speed centrifugation (Walter et al., 1998). Immunoblots of the cytosolic and nuclear fractions were probed with antibodies against cyclins E, A1, and B2. Figure 5B shows that, as expected, cyclin E became highly concentrated within nuclei after an 80-min incubation. By contrast, the endogenous Xenopus cyclin A1 did not become highly concentrated within nuclei; most of the protein remained cytoplasmic, although some was detected in the nuclear fraction (Figure 5B). As expected from previous studies in intact oocytes (Gautier and Maller, 1991), cyclin B2 was cytoplasmic in egg extracts and was almost entirely excluded from the nuclear fraction.

We next asked whether promoting the nuclear accumulation of cyclin A–dependent kinase would increase its ability to drive DNA replication. Endogenous Cdk/cyclin complexes were removed from egg extracts by depletion on Suc1-Sepharose beads and replaced with either wild-type or NLS-tagged Cdk2 complexed with cyclin E, cyclin EΔNLS, or cyclin A. Cdk2/cyclin A proved more potent than Cdk2/cyclin E at triggering DNA replication. In the experiment shown in Figure 5C, 12–25 nM Cdk2/cyclin A restored as much replication as 100–200 nM Cdk2/cyclin E. As before, Cdk2/cyclin EΔNLS was unable to restore significant amounts of replication, a defect largely overcome by fusing an NLS to the C-terminus of Cdk2. Cdk2-NLS/cyclin A complexes were no more effective than Cdk2/cyclin A at driving replication. Nuclear concentrations of 12–25 nM Cdk2/cyclin A therefore suffice to support DNA replication at >50% of the normal rate. Thus, if we compare the intranuclear concentrations required in this system, it seems that cyclin A is at least 100 times more efficient than cyclin E at promoting replication.

Cdk2/Cyclin EΔNLS Complexes Can Help to Promote Entry into Mitosis

When cyclin E levels are reduced by immunodepletion of egg extracts, the resulting preparations require higher levels of cyclin B than normal to promote nuclear envelope breakdown and chromosome condensation (Guadagno and Newport, 1996). We wondered whether the subcellular location of cyclin E was important for this effect. To test this, we supplemented mock-depleted or cyclin E–depleted interphase egg extracts with demembranated sperm heads (∼1000/μl) to provide a template for nuclear assembly and 5 mM caffeine to override the S-M checkpoint pathway (Dasso and Newport, 1990). Nuclei were allowed to assemble for 45 min, and then extracts were supplemented with buffer, 100 nM Cdk2/cyclin E, or 100 nM Cdk2/cyclin EΔNLS. After an additional 15 min at room temperature, samples were split between tubes containing a range of concentrations of recombinant cyclin B1. The state of the nuclei and of the chromatin in the extracts was examined by fluorescence microscopy 45 min later.

Figure 6 shows that in mock-depleted extracts, morphological changes in nuclei consistent with M-phase entry were produced by 60 nM of the cyclin B1 preparation, but extracts lacking cyclin E required 120 nM of added cyclin B1. Addition of either 100 nM Cdk2/cyclin E or Cdk2/cyclin EΔNLS to the cyclin E–depleted extracts enabled 60 nM cyclin B1 to provoke entry into mitosis. These data suggest that Cdk2/cyclin E complex does not have to enter nuclei to collaborate with cyclin B at the interphase to mitosis transition, at least under the conditions of this experiment.

If reducing the Cdk2/cyclin E activity delayed the interphase/mitosis transition, excess Cdk2/cyclin E might accelerate entry into mitosis. We prepared “cycling” egg extracts that synthesize A- and B-type cyclins and oscillate between S phase and M phase (Murray, 1991), added demembranated sperm, and then after 50 min, supplemented them with either buffer or 0.6 μM Cdk2/cyclin E. Figure 7 shows that nuclear envelope breakdown and chromosome condensation were observed at 130 min in the buffer-supplemented extract, and the onset of these events was advanced by ∼30 min in the extract to which Cdk2/cyclin E had been added. Addition of Cdk2/cyclin E complexes lacking nuclear localization signals was not as effective at advancing the timing of entry into mitosis in these cycling extracts. In the experiment shown in Figure 7, addition of a higher concentration (1 μM) of Cdk2/cyclin EΔN60 (a truncated form of cyclin E lacking the N-terminal 60 residues) accelerated the interphase/mitosis transition by ∼20 min (compared with the 30-min acceleration seen with wild-type cyclin E). In other tests, the acceleration was even less. As recently reported by others (D'Angiolella et al., 2001; Tunquist et al., 2002), we found that addition of high levels of Cdk2/cyclin E to cycling egg extracts frequently caused a mitotic arrest and impaired cyclin B degradation (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

The results in this article clearly establish that the N-terminus of Xenopus cyclin E contains a basic NLS that is essential for the nuclear accumulation of Cdk2/cyclin E in egg extracts. Removal of the N-terminus of cyclin E prevents it from interacting with the importin heterodimer, and mutation of the candidate basic NLS sequence, the RSRKRK motif, prevents the accumulation of cyclin E within egg extract nuclei. Although Cdk2/cyclin EΔNLS complexes have nearly wild-type kinase activity, as measured in solution with histone H1 as a substrate, their ability to support DNA replication is seriously compromised. This deficiency can be overcome by targeting the mutant complexes to the nucleus with a heterologous NLS. We also provide evidence that Cdk2/cyclin E must accumulate to high concentrations in the nucleus to trigger DNA replication. Nuclear accumulation, however, is not necessary for Cdk2/cyclin E to perform all its functions, as revealed by the similar threshold level of cyclin B required to trigger entry into mitosis when wild-type cyclin E is replaced by Cdk2/cyclin EΔNLS.

The Role of Cdk2/Cyclin E at the Interphase/Mitosis Transition

Guadagno and Newport (1996) showed that either addition of the p21 Cdk inhibitor or depletion of cyclin E impaired the ability of interphase Xenopus egg extracts to enter mitosis in response to added recombinant cyclin B. These results were interpreted to indicate that Cdk2/cyclin E, in addition to its roles during S phase, also operates at the interphase/mitosis transition in Xenopus eggs. We have confirmed these results. In the absence of cyclin E, the minimum concentration of cyclin B1 required to trigger mitosis was doubled from 60 to 120 nM. The magnitude of this difference is smaller than reported by Guadagno and Newport (1996), but they reported results from only a limited range of cyclin B concentrations. We find that both wild-type Cdk2/cyclin E and Cdk2/cyclin EΔNLS are able to restore the 60-nM threshold level of cyclin B to trigger Cdk1/cyclin B activation, but we also have evidence that nuclear Cdk2/cyclin E is somewhat more potent at assisting cyclin B to initiate mitosis (see below).

We found that artificially elevated Cdk2/cyclin E activity in Xenopus egg extracts tended to accelerate entry into mitosis in egg extracts allowed to synthesize their own cyclin B, although no amount of added cyclin E could evoke any M-phase events if added to cycloheximide-supplemented extracts (data not shown). The Cdk2/cyclin E concentration must be increased by ∼10-fold to see significant acceleration of nuclear envelope breakdown, but the protein does not need to be concentrated in the nucleus for this effect. As little as 1 μM of nonnuclear Cdk2/cyclin E can therefore deregulate entry into mitosis, which, as discussed below, is substantially less than the concentration of nuclear Cdk2/cyclin E required to efficiently perform its normal function in S phase. Although nonnuclear Cdk2/cyclin E can accelerate entry into mitosis, we found that wild-type cyclin E was more potent. In this regard, it is interesting that structures to which Cdk2/cyclin E has been reported to localize, namely, the nucleus (Hua et al., 1997) and centrosomes (Hinchcliffe et al., 1999), are required for the normal kinetics of activation of Cdk1/cyclin B in fertilized Xenopus eggs (Perez-Mongiovi et al., 2000). Currently, it is unclear what substrates Cdk2/cyclin E must phosphorylate to promote entry into mitosis transition, but as discussed by Guadagno and Newport (1996), Cdc25C would be an obvious candidate, for it is known that Cdk2/cyclin E can phosphorylate sites in the regulatory domain of Cdc25C leading to activation of its phosphatase activity (Izumi and Maller, 1995).

In mammalian somatic cells, Cdk2/cyclin A is thought to regulate the timing of activation of Cdk1/cyclin B (Pagano et al., 1992; Furuno et al., 1999), but unlike the situation in Xenopus extracts, there is no evidence that Cdk2/cyclin E can perform a similar function. Indeed, high concentrations of Cdk2/cyclin E (2–4 μM) failed to accelerate entry into mitosis when microinjected into HeLa cells in G2, whereas high levels of Cdk2/cyclin A did advance entry into mitosis (Furuno et al., 1999). Thus, there seems to be a difference in the response of the frog egg extracts and mammalian cells to elevated cyclin E.

To Trigger DNA Replication, Cdk2/Cyclin E Must Be Concentrated within Nuclei

It is hardly surprising that Cdk2/cyclin E requires access to chromatin after nuclear assembly to promote DNA replication. We were more surprised to find that Cdk2/cyclin E must be concentrated to high levels within nuclei to trigger the onset of DNA replication. Even modest reductions in the concentration of Cdk2/cyclin E in Xenopus egg extracts led to a substantial defect in DNA replication compared with normal controls. The inhibition was not corrected by adding back Cdk2/cyclin EΔNLS, which does not accumulate in nuclei. For replication to occur at maximum rates, therefore, it seems that Cdk2/cyclin E must be concentrated to surprisingly high levels within nuclei, perhaps 6–10 μM. This is somewhat surprising, given that 100 nM of NLS-deficient Cdk2/cyclin E suffices to play a supporting role at entry into mitosis and that 1 μM can substantially advance its normal onset. Why is this high concentration required?

In a widely accepted “two-step” model for replication initiation, the assembly of prereplicative complexes at origins of replication is separated in time from origin firing (Diffley, 1996). Activation of S phase promoting Cdk/cyclin complexes has the dual role of firing replication initiation from prereplicative complexes and preventing the formation of new complexes (Dahmann et al., 1995). Assembling functional prereplicative complexes therefore requires a period of low Cdk activity after mitosis. In most systems, this is achieved by inactivation of CDKs by degradation of cyclins during mitotic exit. In Xenopus egg extracts, however, cyclin E is a stable protein, and Cdk2/cyclin E activity is present throughout the cell cycle, oscillating only over a narrow range between interphase and mitosis (Gabrielli et al., 1992; Rempel et al., 1995).

In the absence of other regulatory mechanisms, the stability of cyclin E in early frog embryos would seem to pose a problem for the “two-step” model. Could it be that the concentration of cyclin E within the nucleus provides a way to vary the activity of cyclin E–associated kinase with respect to its chromatin-associated targets? According to this view, high concentrations of Cdk2/cyclin E activity are necessary to trigger replication, because the initiation machinery has evolved so that total concentration of active Cdk2/cyclin E present in the cells at the end of mitosis does not impair assembly of prereplicative complexes. In fact, the replication machinery is quite resistant to increased Cdk2/cyclin E activity during nuclear assembly. To inhibit replication by even 30–50% requires the addition of 1–1.5 μM of either wild-type or cytoplasmically targeted Cdk2/cyclin E (data not shown) (Hua et al., 1997).

Cdk/Cyclin A Does Not Need to Be Concentrated within Nuclei to Trigger DNA Replication

Unlike cyclin E, cyclin A levels oscillate in the early cell cycles of fertilized frog eggs (Minshull et al., 1990). Oscillations of Cdk/cyclin A activity with respect to chromatin will therefore occur during cell cycle progression, even without cyclin A becoming concentrated in the nuclei. Nevertheless, we were surprised to find that cyclin A did not become significantly concentrated within nuclei assembled in egg extracts. This differs from the situation in vertebrate somatic cells, in which the steady-state localization of cyclin A is nuclear but the time scales involved are different. The nuclear import of cyclin A, at least in Xenopus oocytes, is considerably slower than that of cyclin E (Moore et al., 1999). We should emphasize, however, that some cyclin A can be detected in the nuclear fraction of egg extracts. It appears that these low nuclear concentrations (12–25 nM) of Cdk2/cyclin A are able to support replication at near normal rates in extracts from which the endogenous Cdk-complement has been depleted. This implies that Cdk2/cyclin A is perhaps 200- to 400-fold more effective at supporting DNA replication than Cdk2/cyclin E.

Why is cyclin A so much better at promoting replication than cyclin E? Consistent with other reports, we find that the specific activity of Cdk2/cyclin A is approximately eightfold higher than Cdk2/cyclin E with histone H1 as a substrate (data not shown). Although this difference in activity is in the right direction, it cannot explain the massive differences in efficiency with which the two enzymes promote DNA replication. It is possible that the relevant substrate is far more effectively phosphorylated by Cdk2/cyclin A than by Cdk2/cyclin E. Alternatively, high local concentrations of Cdk2/cyclin A with respect to this substrate may be achieved by other means, such as a strong interaction between cyclin A and its (hypothetical) chromatin-bound receptor. It will be necessary to identify the critical substrates phosphorylated by Cdk/cyclin complexes to trigger DNA replication to reach definitive conclusions.

The situation in Xenopus egg extracts, in which replication can apparently be driven by either cyclin E– or cyclin A–dependent kinases, is unusual. In cultured mammalian cells, both appear to be required (Pagano et al., 1992; Ohtsubo et al., 1995). Studies in intact mammalian cells have always been complicated by the involvement of the S phase promoting Cdk2/cyclin complexes in the transcription of mRNAs for proteins required for replication. One recent report, however, used an in vitro system based on G1 nuclei and cytoplasm from mammalian cells, supplemented with relevant recombinant proteins, to probe the functions of the two cyclin-dependent kinases. It was proposed that at least during the transition into S phase from the G1 phase block imposed by serum withdrawal, cyclin E– and cyclin A–dependent kinases execute sequential and separate functions (Coverley et al., 2002). According to these authors, cyclin E “opens a window of opportunity” for replication complex assembly, which is then closed by the activation of cyclin A. Further increases of Cdk2/cyclin A activity are then proposed to fire replication origins. In this system, Cdk2/cyclin E seems to be unable to trigger replication itself (Coverley et al., 2002). In contrast, cyclin E is normally essential for DNA replication in Drosophila embryos, and cyclin A is not required. However, cyclin A can complement for an absence of cyclin E if constraints on Cdk/cyclin A activity are overcome (Knoblich et al., 1994; Sprenger et al., 1997). Explaining these differences between different organisms at different stages of development really requires, as we said above, identification of the salient substrates and a more detailed understanding of the pathways for assembly and firing of the origins of DNA replication.

Nucleocytoplasmic Transport of Cdk2/Cyclin E in Somatic Cells

The sequence responsible for the uptake of cyclin E into nuclei in egg extracts is conserved in other vertebrate cyclin E proteins. Surprisingly, several lines of evidence suggest that these motifs are not required for the nuclear localization of Cdk2/cyclin E in mammalian somatic cells. Thus, Kelly et al. (1998) found that mutation of the RSRKRK motif of human cyclin E to RSRAAA neither prevented the nuclear accumulation of the protein nor its ability to accelerate S-phase onset in transiently transfected murine cells. In fact, even deletion of the entire N-terminus did not stop the nuclear accumulation of human cyclin E (Porter et al., 2001). Redundant mechanisms for cyclin E nuclear uptake therefore seem to exist in somatic cells, and these mechanisms may be quite efficient: the N-terminally truncated cyclin E protein was reported to remain exclusively nuclear (Porter et al., 2001).

The localization of Cdk2/cyclin E in somatic cells may be subject to additional levels of control that are, as far as we know, absent in Xenopus egg extracts. For example, Keenan et al. (2001) report that PD98059, an inhibitor of the mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase kinase, MEK, prevents Cdk2/cyclin E nuclear localization in human cells. Because cyclin E and importin-α proteins purified from bacteria are able to associate without incubation in egg extracts, we can exclude the possibility that the phosphorylation of either protein by members of the MAP kinase family is required for their interaction. It is possible that Cdk2/cyclin E complexes shuttle in and out of somatic cell nuclei (Jackman et al., 2002), and perhaps MAP kinase activity is necessary to downregulate the export arm of this shuttling. It would be interesting to identify the pathway(s) of cyclin E localization in somatic cells and how they contribute to the biological function of the protein.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Drs. Birke Bartosch, Michael Rexach, Dirk Görlich, Akiko Kumagai, Bill Dunphy, and David Morgan for generous gifts of reagents. We thank John Diffley and members of the Hunt laboratory for helpful and interesting discussions during the course of this work. We thank Hiro Mahbubani and Jane Kirk for care of the frogs. J.D.M. was supported by fellowships from the Leukemia Research Foundation (Evanston, IL) and from the former Imperial Cancer Research Fund (now Cancer Research UK). S.K. is a scholar of the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society and was supported by National Institutes of Health grant R01 GM60500.

Footnotes

Article published online ahead of print. Mol. Biol. Cell 10.1091/mbc.E02–07–0449. Article and publication date are at www.molbiolcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1091/mbc.E02–07–0449.

REFERENCES

- Alt JR, Cleveland JL, Hannink M, Diehl JA. Phosphorylation-dependent regulation of cyclin D1 nuclear export and cyclin D1-dependent cellular transformation. Genes Dev. 2000;14:3102–3114. doi: 10.1101/gad.854900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartosch B. The Stability and Turnover of Cyclin E. Ph.D. Thesis. London: University of London; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Brown NR, Noble ME, Endicott JA, Garman EF, Wakatsuki S, Mitchell E, Rasmussen B, Hunt T, Johnson LN. The crystal structure of cyclin A. Structure. 1995;3:1235–1247. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(01)00259-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chida K, Vogt PK. Nuclear translocation of viral Jun but not of cellular Jun is cell cycle dependent. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:4290–4294. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.10.4290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coverley D, Laman H, Laskey RA. Distinct roles for cyclins E and A during DNA replication complex assembly and activation. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4:523–528. doi: 10.1038/ncb813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Angiolella V, Costanzo V, Gottesman ME, Avvedimento EV, Gautier J, Grieco D. Role for cyclin-dependent kinase 2 in mitosis exit. Curr Biol. 2001;11:1221–1226. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00352-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahmann C, Diffley JF, Nasmyth KA. S-phase-promoting cyclin-dependent kinases prevent re-replication by inhibiting the transition of replication origins to a pre-replicative state. Curr Biol. 1995;5:1257–1269. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(95)00252-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dasso M, Newport JW. Completion of DNA replication is monitored by a feedback system that controls the initiation of mitosis in vitro: studies in Xenopus. Cell. 1990;61:811–823. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90191-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- den Elzen N, Pines J. Cyclin A is destroyed in prometaphase and can delay chromosome alignment and anaphase. J Cell Biol. 2001;153:121–136. doi: 10.1083/jcb.153.1.121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diffley JF. Once and only once upon a time: specifying and regulating origins of DNA replication in eukaryotic cells. Genes Dev. 1996;10:2819–2830. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.22.2819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Draviam VM, Orrechia S, Lowe M, Pardi R, Pines J. The localization of human cyclins B1 and B2 determines CDK1 substrate specificity and neither enzyme requires MEK to disassemble the Golgi apparatus. J Cell Biol. 2001;152:945–958. doi: 10.1083/jcb.152.5.945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furuno N, den Elzen N, Pines J. Human cyclin A is required for mitosis until mid prophase. J Cell Biol. 1999;147:295–306. doi: 10.1083/jcb.147.2.295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabrielli BG, Roy LM, Gautier J, Philippe M, Maller JL. A cdc2-related kinase oscillates in the cell cycle independently of cyclins G2/M and cdc2. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:1969–1975. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gautier J, Maller JL. Cyclin B in Xenopus oocytes: implications for the mechanism of pre-MPF activation. EMBO J. 1991;10:177–182. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb07934.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geley S, Kramer E, Gieffers C, Gannon J, Peters JM, Hunt T. Anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome-dependent proteolysis of human cyclin A starts at the beginning of mitosis and is not subject to the spindle assembly checkpoint. J Cell Biol. 2001;153:137–148. doi: 10.1083/jcb.153.1.137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girard F, Strausfeld U, Fernandez A, Lamb NJ. Cyclin A is required for the onset of DNA replication in mammalian fibroblasts. Cell. 1991;67:1169–1179. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90293-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guadagno TM, Newport JW. Cdk2 kinase is required for entry into mitosis as a positive regulator of Cdc2-cyclin B kinase activity. Cell. 1996;84:73–82. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80994-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagting A, Jackman M, Simpson K, Pines J. Translocation of cyclin B1 to the nucleus at prophase requires a phosphorylation-dependent nuclear import signal. Curr Biol. 1999;9:680–689. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)80308-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagting A, Karlsson C, Clute P, Jackman M, Pines J. MPF localization is controlled by nuclear export. EMBO J. 1998;17:4127–4138. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.14.4127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinchcliffe EH, Li C, Thompson EA, Maller JL, Sluder G. Requirement of Cdk2-cyclin E activity for repeated centrosome reproduction in Xenopus egg extracts. Science. 1999;283:851–854. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5403.851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horton RM, Pease LR. Recombination and mutagenesis of DNA sequences using PCR. In: McPherson MJ, editor. Directed Mutagenesis. Oxford: IRL Press at OUP; 1991. pp. 217–247. [Google Scholar]

- Hu B, Mitra J, van den Heuvel S, Enders GH. S and G2 phase roles for Cdk2 revealed by inducible expression of a dominant-negative mutant in human cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:2755–2766. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.8.2755-2766.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hua XH, Yan H, Newport J. A role for Cdk2 kinase in negatively regulating DNA replication during S phase of the cell cycle. J Cell Biol. 1997;137:183–192. doi: 10.1083/jcb.137.1.183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izumi T, Maller JL. Phosphorylation and activation of the Xenopus Cdc25 phosphatase in the absence of Cdc2 and Cdk2 kinase activity. Mol Biol Cell. 1995;6:215–226. doi: 10.1091/mbc.6.2.215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackman M, Kubota Y, den Elzen N, Hagting A, Pines J. Cyclin A- and cyclin E-Cdk complexes shuttle between the nucleus and the cytoplasm. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13:1030–1045. doi: 10.1091/mbc.01-07-0361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson PK, Chevalier S, Philippe M, Kirschner MW. Early events in DNA replication require cyclin E and are blocked by p21CIP1. J Cell Biol. 1995;130:755–769. doi: 10.1083/jcb.130.4.755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin P, Hardy S, Morgan DO. Nuclear localization of cyclin B1 controls mitotic entry after DNA damage. J Cell Biol. 1998;141:875–885. doi: 10.1083/jcb.141.4.875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaelin WG, Jr, Pallas DC, DeCaprio JA, Kaye FJ, Livingston DM. Identification of cellular proteins that can interact specifically with the T/E1A-binding region of the retinoblastoma gene product. Cell. 1991;64:521–532. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90236-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalderon D, Roberts BL, Richardson WD, Smith AE. A short amino acid sequence able to specify nuclear location. Cell. 1984;39:499–509. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(84)90457-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keenan SM, Bellone C, Baldassare JJ. Cyclin-dependent kinase 2 nucleocytoplasmic translocation is regulated by extracellular regulated kinase. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:22404–22409. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100409200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly BL, Wolfe KG, Roberts JM. Identification of a substrate-targeting domain in cyclin E necessary for phosphorylation of the retinoblastoma protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:2535–2540. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.5.2535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knoblich JA, Sauer K, Jones L, Richardson H, Saint R, Lehner CF. Cyclin E controls S phase progression and its down-regulation during Drosophila embryogenesis is required for the arrest of cell proliferation. Cell. 1994;77:107–120. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90239-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumagai A, Dunphy WG. Control of the Cdc2/cyclin B complex in Xenopus egg extracts arrested at a G2/M checkpoint with DNA synthesis inhibitors. Mol Biol Cell. 1995;6:199–213. doi: 10.1091/mbc.6.2.199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacey KR, Jackson PK, Stearns T. Cyclin-dependent kinase control of centrosome duplication. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:2817–2822. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.6.2817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minshull J, Golsteyn R, Hill CS, Hunt T. The A- and B-type cyclin associated cdc2 kinases in Xenopus turn on and off at different times in the cell cycle. EMBO J. 1990;9:2865–2875. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb07476.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore JD, Yang J, Truant R, Kornbluth S. Nuclear import of Cdk/cyclin complexes: identification of distinct mechanisms for import of Cdk2/cyclin E and Cdc2/cyclin B1. J Cell Biol. 1999;144:213–224. doi: 10.1083/jcb.144.2.213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan DO. Cyclin-dependent kinases: engines, clocks, and microprocessors. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1997;13:261–291. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.13.1.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray AW. Cell cycle extracts. Methods Cell Biol. 1991;36:581–605. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nigg EA. Mitotic kinases as regulators of cell division and its checkpoints. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2:21–32. doi: 10.1038/35048096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohtsubo M, Theodoras AM, Schumacher J, Roberts JM, Pagano M. Human cyclin E, a nuclear protein essential for the G1-to-S phase transition. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:2612–2624. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.5.2612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagano M, Pepperkok R, Verde F, Ansorge W, Draetta G. Cyclin A is required at two points in the human cell cycle. EMBO J. 1992;11:961–971. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05135.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Mongiovi D, Beckhelling C, Chang P, Ford CC, Houliston E. Nuclei and microtubule asters stimulate maturation/M phase promoting factor (MPF) activation in Xenopus eggs and egg cytoplasmic extracts. J Cell Biol. 2000;150:963–974. doi: 10.1083/jcb.150.5.963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pines J. Four-dimensional control of the cell cycle. Nat Cell Biol. 1999;1:E73–E79. doi: 10.1038/11041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pines J, Hunter T. Human cyclins A and B1 are differentially located in the cell and undergo cell cycle-dependent nuclear transport. J Cell Biol. 1991;115:1–17. doi: 10.1083/jcb.115.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter DC, Zhang N, Danes C, McGahren MJ, Harwell RM, Faruki S, Keyomarsi K. Tumor-specific proteolytic processing of cyclin E generates hyperactive lower-molecular-weight forms. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:6254–6269. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.18.6254-6269.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rempel RE, Sleight SB, Maller JL. Maternal Xenopus Cdk2-cyclin E complexes function during meiotic and early embryonic cell cycles that lack a G1 phase. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:6843–6855. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.12.6843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rexach M, Blobel G. Protein import into nuclei: association and dissociation reactions involving transport substrate, transport factors, and nucleoporins. Cell. 1995;83:683–692. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90181-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smythe C, Newport JW. Systems for the study of nuclear assembly, DNA replication, and nuclear breakdown in Xenopus laevis egg extracts. Methods Cell Biol. 1991;35:449–468. doi: 10.1016/s0091-679x(08)60583-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprenger F, Yakubovich N, O'Farrell PH. S-phase function of Drosophila cyclin A and its downregulation in G1 phase. Curr Biol. 1997;7:488–499. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(06)00220-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strausfeld UP, Howell M, Descombes P, Chevalier S, Rempel RE, Adamczewski J, Maller JL, Hunt T, Blow JJ. Both cyclin A and cyclin E have S-phase promoting (SPF) activity in Xenopus egg extracts. J Cell Sci. 1996;109:1555–1563. doi: 10.1242/jcs.109.6.1555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strohmaier H, Spruck CH, Kaiser P, Won KA, Sangfelt O, Reed SI. Human F-box protein hCdc4 targets cyclin E for proteolysis and is mutated in a breast cancer cell line. Nature. 2001;413:316–322. doi: 10.1038/35095076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takizawa CG, Weis K, Morgan DO. Ran-independent nuclear import of cyclin B1-Cdc2 by importin beta. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:7938–7943. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.14.7938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toyoshima F, Moriguchi T, Wada A, Fukuda M, Nishida E. Nuclear export of cyclin B1 and its possible role in the DNA damage-induced G2 checkpoint. EMBO J. 1998;17:2728–2735. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.10.2728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tunquist BJ, Schwab MS, Chen LG, Maller JL. The spindle checkpoint kinase bub1 and cyclin e/cdk2 both contribute to the establishment of meiotic metaphase arrest by cytostatic factor. Curr Biol. 2002;12:1027–1033. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00894-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walter J, Sun L, Newport J. Regulated chromosomal DNA replication in the absence of a nucleus. Mol Cell. 1998;1:519–529. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80052-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheatley SP, Hinchcliffe EH, Glotzer M, Hyman AA, Sluder G, Wang Y. CDK1 inactivation regulates anaphase spindle dynamics and cytokinesis in vivo. J Cell Biol. 1997;138:385–393. doi: 10.1083/jcb.138.2.385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J, Bardes ES, Moore JD, Brennan J, Powers MA, Kornbluth S. Control of cyclin B1 localization through regulated binding of the nuclear export factor CRM1. Genes Dev. 1998;12:2131–2143. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.14.2131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]