Abstract

Candida albicans is able to respond to environmental changes by inducing a distinct morphological program, which is related to the ability to infect mammalian hosts. Although some of the signal transduction pathways involved in this response are known, it is not clear how the environmental signals are sensed and transmitted to these transduction cascades. In this work, we have studied the function of GPA2, a new gene from C. albicans, which encodes a G-protein α-subunit homologue. We demonstrate that Gpa2 plays an important role in the yeast-hypha dimorphic transition in the response of C. albicans to some environmental inducers. Deletion of both alleles of the GPA2 gene causes in vitro defects in morphological transitions in Spider medium and SLAD medium and in embedded conditions but not in medium containing serum. These defects cannot be reversed by exogenous addition of cyclic AMP. However, overexpression of HST7, which encodes a component of the filament-inducing mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) cascade, bypasses the Gpa2 requirement. We have obtained different gain-of-function and loss-of-function mutant alleles of the GPA2 gene, which we have introduced in several C. albicans genetic backgrounds. Our results indicate that, in response to environmental cues, Gpa2 is required for the regulation of a MAPK signaling pathway.

Candida albicans is the most common fungal pathogen in humans. It is frequently associated with systemic infections in immunocompromised patients (39). The molecular analysis of the regulation of virulence traits in this organism may reveal new targets for antifungal agents. C. albicans is a dimorphic fungus, in which the yeast-hypha transition is triggered by different environmental cues such as serum, neutral pH, high temperature, starvation, etc. Disease progression is promoted by yeast-hypha morphogenesis, which is linked to the expression of virulence factors (8, 10). Research efforts have been directed to the characterization of the transduction pathways involved in this signaling process. Most of the dimorphic transition signals converge into two parallel signal transduction pathways, defined by the transcription factors Efg1 and Cph1 (17). The Efg1 protein is thought to be the major regulator in hyphal development because mutants with null mutations in the EFG1 gene display severe hyphal defects (33, 48). Current models place EFG1 in the cyclic AMP (cAMP) signaling pathway. Epistatic analyses are consistent with efg1 being situated downstream of the C. albicans isoforms of protein kinase A (PKA) (4, 47), and Efg1 itself could be a target of PKA phosphorylation (3). The Cph1 protein is part of a mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase-based signaling pathway. Cph1 is a transcription factor thought to be activated by this MAP kinase cascade (13, 23, 28, 29, 32). Additional pathways are the pH-responsive and embedded pathways, which involve specific regulators but which are also dependent on the Efg1 and Cph1 pathways (9, 16, 21, 46).

Although it is known that C. albicans responds to environmental cues, little is known about the way these stimuli are sensed and transmitted to the different signaling pathways. In eukaryotic cells, the small GTP-binding protein Ras and heterotrimeric G proteins are involved in the transmission of external signals. In C. albicans a single Ras protein has been described (18, 30). Genetic analyses have shown that RAS1 is located upstream of the genes involved in both the Efg1 and Cph1 pathways (12, 30). G-protein α-subunit (Gα-subunit)-encoding genes in a growing number of fungal species have been identified (5). In these fungi, deletion of Gα subunits leads to morphological and mating defects that compromise the ability of the fungi to respond to the appropriate stimuli. In C. albicans, only one Gα subunit has been described so far, the one encoded by the CAG1 gene, but no noticeable morphological phenotypes are present in null mutants (43). A second Gα-homologue-encoding gene, called GPA2, has been identified during the course of the annotation of assembly 6 of the C. albicans genome available at the Stanford Genome Tech-nology Center (http://www-sequence.Stanford.edu/group/candida) and conducted by the European Consortium Galar Fungail (http://www.Pasteur.fr/recherché/unites/Galar_Fungail/). In this study, we sought to investigate the role of the C. albicans GPA2 gene in mediating morphological transitions in response to environmental inducers. Our results suggest that signal transduction through G proteins contributes to dimorphic differentiation in response to environmental cues.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and media.

C. albicans strains are listed in Table 1. Routine growth was on yeast extract-peptone-dextrose (YPD) plates and liquid medium at 30°C, and selections for URA3 prototrophy were performed on minimal SD plates (45). Counter-selections against URA3 were performed on uridine- and 5-fluoroorotic acid-containing SD plates (19). For specific experiments involving hyphal growth, different media were used. SLAD medium (20) and Spider medium were prepared as previously described. For serum-mediated filamentation YPD medium containing 10% fetal calf serum (Gibco BRL) was used. Lee's medium at pH 7 (31) was used to assess filamentation induced by pH conditions. Embedded conditions were used as previously described (9).

TABLE 1.

C. albicans strains

| Strain | Genotype | Parent strain | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|---|

| SC5314 | Wild type | 19 | |

| CAI4 | ura3::imm434/ura3::imm434 | CAF2 | 19 |

| JKC19 | ura3::imm434/ura3::imm434 cph1::hisG/cph1::hisG-URA3-hisG | CAI4 | 32 |

| Bca9-4 | ura3::imm434/ura3::imm434 efg1::hisG/efg1::hisG-URA3-hisG | CAI4 | 7 |

| ras1-2/ras1-4 | ura3::imm434/ura3::imm434, ras1::hisG/ras1::hph | CAI4 | 18 |

| CCM8 | ura3::imm434/ura3::imm434 GPA2/gpa2::hisG-URA3-hisG | CAI4 | This study |

| CCM12 | ura3::imm434/ura3::imm434 gpa2::hisG/gpa2::hisG-URA3-hisG | CCS13 | This study |

| CCS2 | ura3::imm434/ura3::imm434 MAL2/mal2::MAL2p-FLP-FRT-ACT1p-URA3-FRT | CAI4 | This study |

| CCS3 | ura3::imm434/ura3::imm434 MAL2/mal2::MAL2p-FLP-FRT-ACT1p-GPA2-URA3-FRT | CAI4 | This study |

| CCS4 | ura3::imm434/ura3::imm434 MAL2/mal2::MAL2p-FLP-FRT-ACT1p-GPA2G142V-URA3-FRT | CAI4 | This study |

| CCS5 | ura3::imm434/ura3::imm434 MAL2/mal2::MAL2p-FLP-FRT-ACT1p-GPA2G354V-URA3-FRT | CAI4 | This study |

| CCS6 | ura3::imm434/ura3::imm434 MAL2/mal2::MAL2p-FLP-FRT-ACT1p-GPA2(Q355L)-URA3-FRT | CAI4 | This study |

| CCS8 | ura3::imm434/ura3::imm434 cph1::hisG/cph1::hisG MAL2/mal2::MAL2p-FLP-FRT-ACT1p-GPA2-URA3-FRT | JKC19 | This study |

| CCS9 | ura3::imm434/ura3::imm434 cph1::hisG/cph1::hisG MAL2/mal2::MAL2p-FLP-FRT-ACT1p-GPA2Q355L-URA3-FRT | JKC19 | This study |

| CCS11 | ura3::imm434/ura3::imm434 efg1::hisG/efg1::hisG MAL2/mal2::MAL2p-FLP-FRT-ACT1p-GPA2-URA3-FRT | CCS10 | This study |

| CCS12 | ura3::imm434/ura3::imm434 efg1::hisG/efg1::hisG MAL2/mal2::MAL2p-FLP-FRT-ACT1p-GPA2Q355L-URA3-FRT | CCS10 | This study |

| CCS13 | ura3::imm434/ura3::imm434 gpa2::hisG/GPA2 | CAI4 | This study |

| CCS14 | ura3::imm434/ura3::imm434 gap2::hisG/gpa2::hisG | CCS13 | This study |

| CCS16 | ura3::imm434/ura3::imm434 gpa2::hisG/gpa2::hisG MAL2/mal2::MAL2p-FLP-FRT-ACT1p-URA3-FRT | CCS14 | This study |

| CCS17 | ura3::imm434/ura3::imm434 gpa2::hisG/gpa2::hisG MAL2/mal2::MAL2p-FLP-FRT-ACT1p-GPA2-URA3-FRT | CCS14 | This study |

| CCS18 | ura3::imm434/ura3::imm434 gpa2::hisG/gpa2::hisG MAL2/mal2::MAL2p-FLP-FRT-ACT1p-GPA2G142V-URA3-FRT | CCS14 | This study |

| CCS19 | ura3::imm434/ura3::imm434 gpa2::hisG/gpa2::hisG MAL2/mal2::MAL2p-FLP-FRT-ACT1p-GPA2G354V-URA3-FRT | CCS14 | This study |

| CCS20 | ura3::imm434/ura3::imm434 gpa2::hisG/gpa2::hisG MAL2/mal2::MAL2p-FLP-FRT-ACT1p-GPA2Q355L-URA3-FRT | CCS14 | This study |

| CPJ12 | ura3::imm434/ura3::imm434 [pYPB1-ADH1] | CAI4 | This study |

| CPJ13 | ura3::imm434/ura3::imm434 [pYPB1-ADH1-HST7] | CAI4 | This study |

| CPJ14 | ura3::imm434/ura3::imm434 gpa2::hisG/gpa2::hisG [pYPB1-ADH1] | CCS14 | This study |

| CPJ15 | ura3::imm434/ura3::imm434 gpa2::hisG/gpa2::hisG [pYPB1-ADH1-HST7] | CCS14 | This study |

| CPJ16 | ura3::imm434/ura3::imm434 [pCNB3-RAS1G13V] | CAI4 | This study |

| CPJ17 | ura3::imm434/ura3::imm434 gpa2::hisG/gpa2::hisG [pCNB3-RAS1G13V] | CCS14 | This study |

| CPJ18 | ura3::imm434/ura3::imm434 [pCNB3-GPA2Q355L] | CAI4 | This study |

| CPJ19 | ura3::imm434/ura3::imm434 ras1::hisG/ras1::hph [pCNB3-GPA2Q355L] | ras1-2/ras1-4 | This study |

Knockout of GPA2.

Disruption of the two allelic copies of GPA2 was obtained by the two-step replacement method described by Fonzi and Irwin (19). The GPA2 coding sequence was replaced by the selection marker hisG-URA3-hisG by using two different orientations as described previously (7, 40). In first place, we constructed a plasmid containing 5′ and 3′ GPA2 flanking sequences joined by a small polylinker formed by recognition sites for the BglII, PstI, and KpnI restriction enzymes. The 600-bp 5′ GPA2 region was obtained as a HindIII-PstI fragment by PCR amplification with oligonucleotides CGPA-A (5′GAAGCTTTTTTGGTTTTGGTTTTGTTCCC3′) and CGPA-B (5′CCCTGCAGAAAGATCTGTGTAATGGGGGATGATATAC3′). The 600-bp 3′ GPA2 region was obtained as a PstI-SacI frament by PCR amplification with the CGPA-C (5′CCCTGCAGAAGGTACCAGTTTTATGCAAATTGTCATA3′) and CGPA-D (5′CCGAGCTCATTCAATGGCTTTTTTAAATA3′) oligonucleotides. Both PCR fragments were cloned in pUC19 digested with SacI-HindIII. The resulting plasmid was digested with either BglII-PstI or PstI-KpnI and was ligated with the hisG-URA3-hisG cassette obtained from pMB7 as a BglII-PstI or PstI-KpnI fragment, respectively. The final plasmids, pGPA2KO-A and pGPA2KO-B, were digested with SacI and HindIII and used to transform CAI4 cells. Sequential disruption steps were analyzed by using oligonucleotides directed to hisG sequences and sequences flanking the integration region as previously described (40). Positive clones were confirmed by Southern analysis.

Plasmid constructions.

To construct plasmids carrying the different GPA2 alleles, the genomic GPA2 region was isolated by PCR as a 3.1-kbp HindIII fragment by using DNA from C. albicans SC5314 (19) and cloned in pGEM-T. The GPA2 mutated alleles were obtained by site-directed mutagenesis (27). The oligonucleotides used for the mutagenesis were GPA2-I (5′TTGTTATTGGGATCAGTTGAAAGTGGTAAATCT3′) to generate the GPA2G142V allele, GPA2-K (5′TTATTTGATGTTGGTGTTCAAAGGTCAGAAAGA3′) to generate the GPA2G354V allele, and GPA2-N (5′GATGTTGGTTTAAGGTCAGAAAGA3′) to generate the GPA2Q355L allele. The GPA2 alleles were isolated by PCR as NotI-SacII fragments from the pGEM-derived plasmids where mutagenesis was made and cloned into NotI- and SacII-digested pCNB2 or pCNB3 plasmids. The pCNB2 plasmid carries the ACT1 promoter region cloned in front of the multicloning site, a URA3 selection marker, and the FRT site to allow site-specific integration in the genomes of C. albicans strains carrying FLP cassettes (44). Generation of C. albicans strains able to support the FLP-dependent integration system and the integration of FRT-containing delivery vectors were performed as previously described (44). pCNB3 is a self-replicating URA3 plasmid which carries the ACT1 promoter region cloned in front of the multicloning site (unpublished data).

To construct the plasmid expressing the RAS1G13V allele, we isolated by PCR a genomic 1.5-kbp DNA fragment and cloned this fragment in pGEM-T. This plasmid was used as a template for site-directed mutagenesis with the oligonucleotide QF87 (5′TTGTTGTTGGAGGTGTTGGTGTTGGTAAAT3′) (18). The RAS1G13V allele was isolated by PCR as NotI-SacII fragments from the pGEM-derived plasmid and cloned into the NotI- and SacII-digested pCNB3 plasmid.

The pYPB1-ADHp-HST7 and pBI-HAHYD plasmids, overexpressing HST7 and EFG1 respectively, were gifts from A. J. P. Brown and J. Ernst, respectively, and they have been already described (28, 47).

DNA isolation and Southern blotting.

Genomic DNAs were isolated from C. albicans strains as described previously (22). Southern blotting, probe labeling, and detection were performed according to instructions from the manufacturer of the DIG High Prime DNA labeling and detection starter kit I (Roche).

RESULTS

C. albicans Gpa2 is required for hyphal formation.

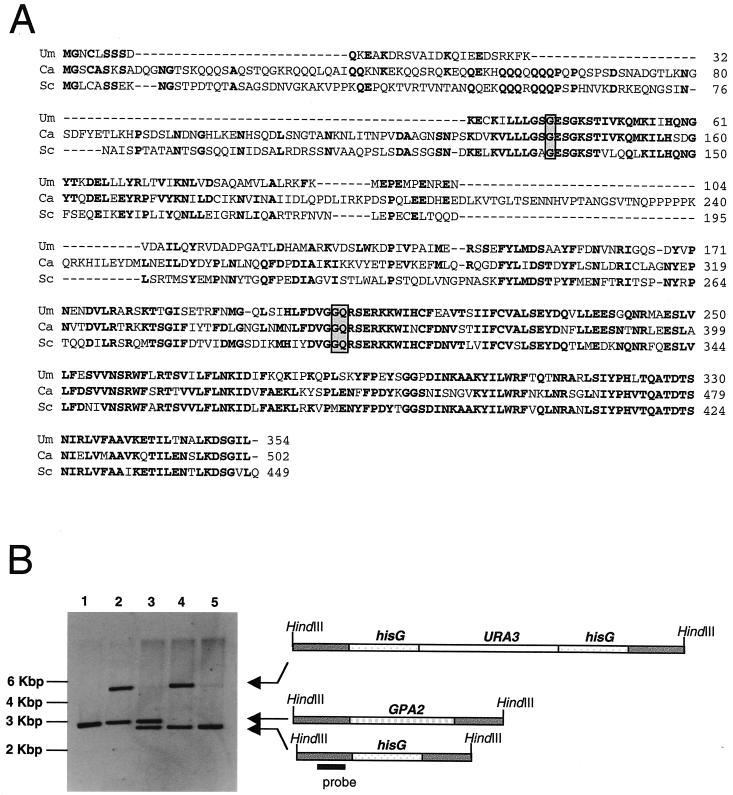

During the process of the annotation of assembly 6 of the C. albicans genome conducted by the European Consortium Galar Fungail, we found an open reading frame whose conceptual translation produces a protein with a high sequence similarity to Gα subunits from other fungi. We called the putative corresponding gene GPA2. The open reading frame of the GPA2 gene contains no intron and is predicted to encode a protein of 502 amino acids. Gpa2 has sequence identities of 46 and 53% with Saccharomyces cerevisiae Gpa2 (34) and Ustilago maydis Gpa3 (41), respectively (Fig. 1A).

FIG. 1.

The C. albicans Gpa2 protein. (A) Sequence alignment of U. maydis Gpa3 (Um), C. albicans Gpa2 (Ca), and S. cerevisiae Gpa2 (Sc) proteins. Identical residues are in boldface. Changed amino acids in the sequences encoded by the different GPA2 alleles are boxed. (B) Deletion of GPA2. Shown is a Southern blot analysis using the 0.6-kbp HindIII-PstI probe located 5′ upstream of GPA2 coding region. The genomic samples, digested with HindIII, were prepared from strains CAI4 (GPA2/GPA2; lane 1), CCM8 (gpa2Δ::hisG-URA3-hisG/GPA2; lane 2), CCS13 (gpa2Δ::hisG/GPA2; lane 3), CCM12 (gpa2Δ::hisG/gpa2Δ::hisG-URA3-hisG; lane 4), and CCS14 (gpa2Δ::hisG/gpa2Δ::hisG; lane 5). The wild type was 3.1 kbp, whereas the KO band with the URA3 blaster was 5.7 kbp. After the URA3 fragment was looped out, the band was reduced to 2.8 kbp.

Homologous recombination was used in a multistep procedure to delete both alleles of GPA2 in the SC5314-derived C. albicans strain CAI4. The deletions were confirmed by Southern blot analyses (Fig. 1B). Strains homozygous for the GPA2 deletion were viable, and mutant cells grew at rates similar to those for wild-type cells in liquid medium. In solid medium, a slight colony size reduction was apparent (not shown).

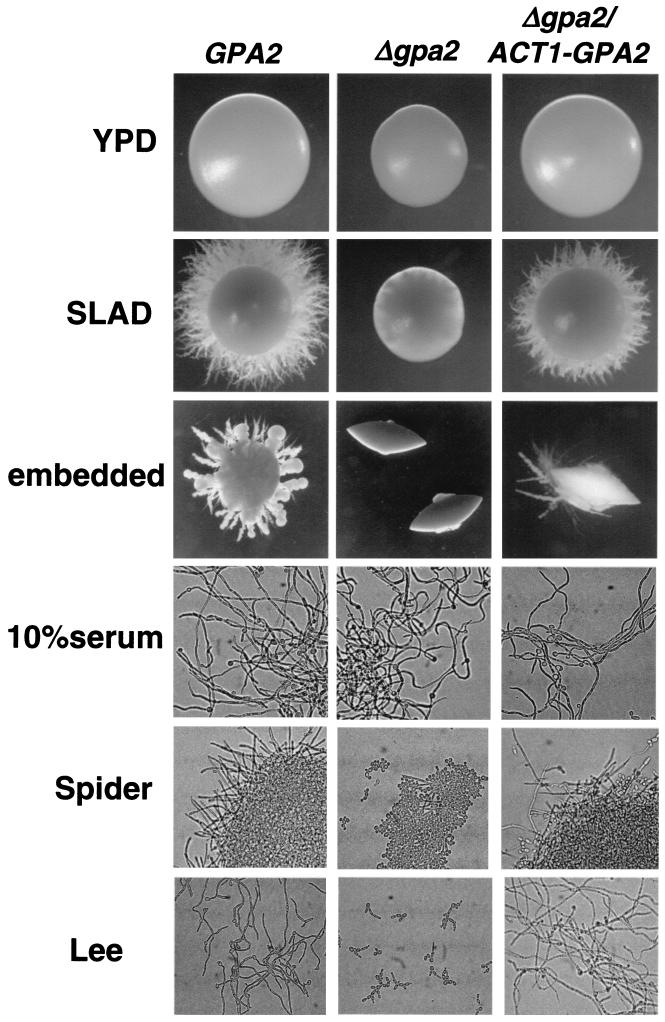

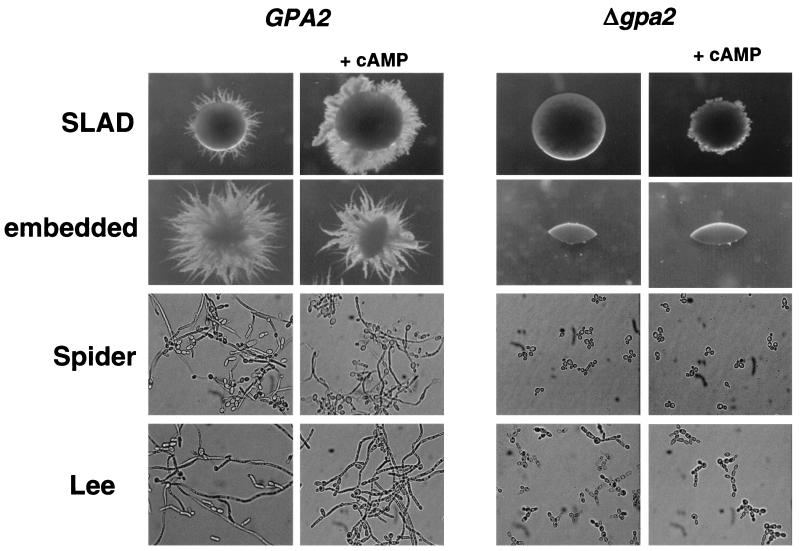

The ability of C. albicans cells to switch from a yeast-like to a hyphal mode of growth was not affected by deletion of only one allele of GPA2 (not shown). However, deletion of both alleles blocked the yeast-to-hypha transition in specific media (Fig. 2). When morphological switching was induced in Spider liquid medium or under neutral-pH conditions (Lee's medium, pH 7), we observed that cells were defective in the formation of germ tubes or filaments. In contrast, Gpa2-defective cells were able to respond to 10% serum in liquid cultures. On solid SLAD medium or as well as in embedded conditions, the normal formation of hyphae was completely suppressed. These defects were corrected by the ectopic integration of the GPA2 coding sequence under the control of the ACT1 promoter (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Defects in hyphal formation caused by deletion of GPA2. Wild-type strain CCS2 (GPA2), the isogenic disrupted strain CCS16 (Δgpa2), and the isogenic disrupted strain carrying the GPA2 coding sequence under the control of the ACT1 promoter, CCS17 (gpa2/ACT-GPA2), were plated in different solid medium. YPD plates were incubated at 37°C for 3 days. SLAD plates were incubated at 37°C for 7 days. Cultures in embedded conditions were incubated at 22°C for 7 days. Log-phase cells were incubated in liquid YPD with fetal calf serum (10% final concentration), Spider medium, and pH 7 Lee's medium at 37°C. Pictures were taken after 8 h of incubation in the test medium.

Different GPA2 mutations affect filamentation.

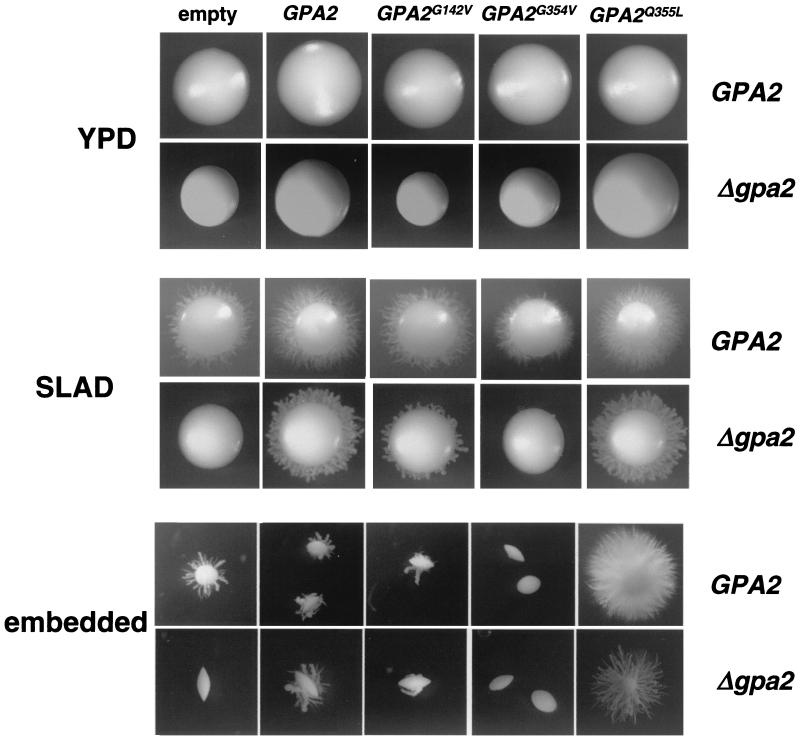

G proteins are highly conserved at both the structural and sequence levels in all organisms, from yeast to human cells, and several mutations in other Gα subunits that perturb the proper function of the G protein have been described. To further characterize the function of Gpa2, we introduced three independent mutations in the GPA2 coding sequence. The associated amino acid changes have shown both positive and negative effects in other Gα subunits, and they are located in specific domains involved in the change from the GTP form (active) to the GDP form (inactive). Two of them, Gly to Val at residue 354 and Gln to Leu at residue 355, are located in a loop that is hypothesized to participate in the GTP-triggered conformational switch of GTP-binding proteins. Mutations in this domain are predicted to have either a positive effect, mimicking the GTP-bound state (35), or a negative effect, impairing the GTP-induced conformational change (36). The third mutation, Gly 142 to Val, was introduced into a loop that contacts the phosphoryls of GDP. This mutation has different outcomes depending on the protein: in the mammalian Gsα, the associated coding sequence mutation produces a constitutive allele with low activity (35), but a similar amino acid change in S. cerevisiae Gpa2 produces a gain-of-function phenotype (34, 49).

The wild-type and mutant alleles were cloned under the control of the constitutive promoter of the actin gene from C. albicans (ACT1) (14), and they were introduced into a wild-type strain and a strain defective in Gpa2. The modified strains were analyzed for their abilities to support hyphal development in response to solid SLAD medium and embedded conditions (Fig. 3), as well as liquid Spider and Lee pH 7 media (not shown). The presence of an extra dose of GPA2 does not affect the ability of wild-type cells to respond to stimuli that induce hyphal growth.

FIG. 3.

Effect on the hyphal response to different stimuli in C. albicans strains expressing different GPA2 mutant alleles. Shown are colony phenotypes of strains, either wild type or defective for Gpa2, carrying different GPA2 alleles integrated in the genome: CCS2 and CCS16, empty vector; CCS3 and CCS17, GPA2; CCS4 and CCS18, GPA2G142V; CCS5 and CCS19, GPA2G354V; CCS6 and CCS20, GPA2Q355L. YPD plates were incubated at 37°C for 3 days. SLAD plates were incubated at 37°C for 7 days. Media associated with embedded conditions were incubated at 22°C for 7 days.

The GPA2G142V allele was able to partially suppress the defects associated with the gpa2 deletion. No effect was apparent after the expression of this mutant allele in a GPA2 wild-type background. These data suggest that the GPA2G142V allele is a partially active allele.

The GPA2G354V allele was unable to complement the gpa2 deletion at any condition tested. Furthermore, when expressed in a GPA2 wild-type background, it impaired the ability of the cells to respond to solid-medium conditions (Fig. 3) as well as to liquid media (not shown). This indicates that the GPA2G354V allele is a loss-of-function mutant able to act as a dominant-negative allele.

The GPA2Q355L allele improves considerably the response in solid SLAD medium and embedded conditions both in gpa2 mutant and wild-type cells (Fig. 3). However, there was no further improvement in liquid Spider and Lee's pH 7 media with respect to the expression of a GPA2 wild-type allele, although the mutant allele was able to fully complement the gpa2 deletion in these media (not shown). These results are compatible with a hyperactive allele, and they are in agreement with the gain-of-function phenotype produced by similar mutations in other fungal Gα subunits, such as the Gpa3 protein from U. maydis, which is also involved in morphogenesis (41).

In summary, we have obtained three different GPA2 alleles, which confer on the cells that carry them different abilities to respond to a dimorphic switch. Because these abilities can be strictly correlated with the degree of activity reported for mutants with similar mutations in other Gα proteins, these results reinforce a direct role for Gpa2 in the bud-hypha switch in C. albicans.

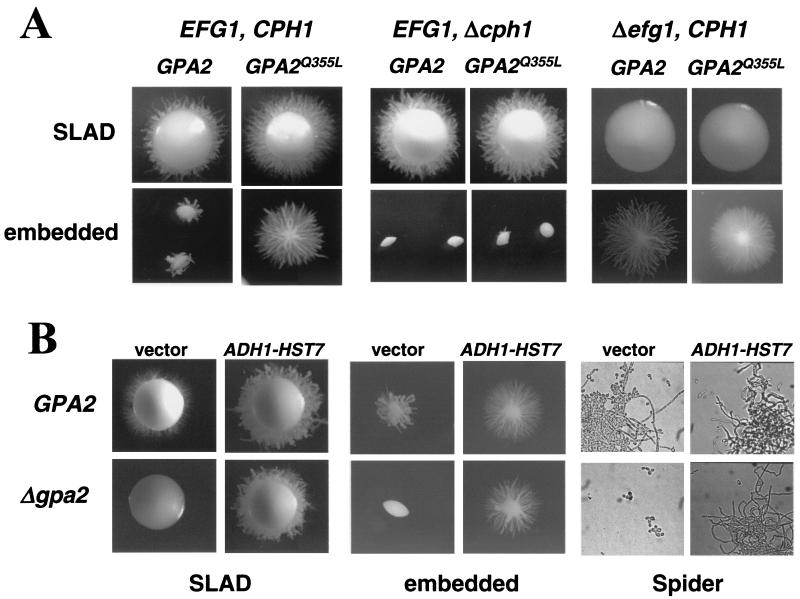

GPA2 promotes hyphal growth through the MAP kinase pathway.

As mentioned above, the bud-hypha transition in C. albicans is mainly dependent on two parallel signaling pathways, defined by the transcription factors Efg1 and Cph1 (17). To examine the relationships between Gpa2 and these pathways, we took advantage of the gain-of-function phenotype of the GPA2Q355L allele. We expressed this hyperactive allele in strains defective in either Efg1 or Cph1, and then we analyzed the abilities to produce hyphal switching in solid SLAD medium and in embedded conditions. In these media, the expression of the GPA2Q355L allele enhances the bud-hypha transition in wild-type cells, as shown above (Fig. 3).

In our hands, the cph1 mutant strain had no defect in filamentous growth on SLAD agar but was totally unable to form filamentous colonies in embedded conditions. Interestingly, the expression of the GPA2Q355L allele is unable to suppress the defects occurring in embedded conditions and does not enhance the ability to produce hyphal growth in SLAD medium, with respect to the expression of a wild-type GPA2 allele (Fig. 4A).

FIG. 4.

Relationship between Gpa2 and the MAP kinase and cAMP-dependent pathways (A) Cells of C. albicans with functional or mutated EFG1 and CPH1genes were transformed with integrative plasmids carrying either the GPA2 wild-type allele or the GPA2Q355L hyperactive allele under the control of the ACT1 promoter. The different strains, CCS3 (GPA2 EFG1 CPH1), CCS6 (GPA2Q355L EFG1 CPH1), CCS8 (GPA2 EFG1 Δcph1), CCS9 (GPA2Q355L EFG1 Δcph1), CCS11 (GPA2 Δefg1 CPH1), and CCS12 (GPA2Q355L Δefg1 CPH1) were assayed for their abilities to support hyphal development in SLAD medium and embedded conditions. (B) C. albicans cells with both alleles of GPA2 deleted and wild-type cells were transformed with an empty control vector (vector) and an HST7-containing vector (ADH1-HST7). The resulting strains, CPJ12 (GPA2 vector), CPJ13 (GPA2 ADH-HST7), CPJ14 (Δgpa2 vector), and CPJ15 (Δgpa2 ADH-HST7), were assayed for hyphal growth on SLAD plates, in embedded conditions, and in liquid Spider medium as described for Fig. 2.

The efg1 mutant is totally unable to produce hyphal growth in SLAD medium, and this defect is not suppressed by the expression of the GPA2Q355L allele. However, filamentation in an efg1 mutant under embedded conditions is actually improved (in agreement with previous reports [21, 46]), and, strikingly, it is further enhanced by the expression of the GPA2Q355L allele (Fig. 4A).

Since these experiments suggest that Gpa2 may mediate signals to the filament-inducing MAP kinase signaling pathway, we tried to reverse the observed defects in a gpa2 mutant strain by introducing an overexpression plasmid carrying HST7 under the control of the strong ADH1 promoter. We had observed previously that a strain defective in HST7, encoding a MAP kinase proposed to act upstream of Cph1 (28), was unable to produce hyphal growth in solid SLAD medium and liquid Spider medium and in embedded conditions and that these defects were not corrected by the expression of the GPA2Q355L allele (not shown). We found that overexpression of HST7 is able to suppress the filamentation defects of a gpa2 mutant, supporting a role for Gpa2 upstream of the filament-inducing MAP kinase signaling pathway (Fig. 4B). Of note, overexpression of HST7 enhanced the ability of wild-type cells to induce hyphal growth in embedded conditions, reinforcing the role of the MAP kinase signaling pathway in the response to these conditions.

Exogenous addition of cAMP does not rescue the gpa2 defects.

Studies of other fungi have demonstrated that there is a clear connection between Gα subunits and cAMP metabolism (6, 15). Although the results presented above locate Gpa2 upstream of the MAP kinase pathway, they do not rule out some role for Gpa2 in C. albicans in the regulation of intracellular cAMP levels. Biochemical studies of C. albicans implicate cAMP level increases in bud-hypha transitions (11, 37, 38). Previous reports have shown that exogenous addition to C. albicans cells of cAMP or dibutyryl cAMP (dbcAMP; a membrane-permeable derivative) increases the frequency of bud-hypha transitions and is able to suppress a defect in adenylate cyclase activity (2, 42).

In our hands, addition of dbcAMP to wild-type cells enhances the ability to respond to SLAD solid media and produces only a slight acceleration in hyphal formation in Lee's pH 7 and Spider liquid media. In contrast, in embedded conditions, the filamentation is impaired after the addition of dbcAMP (Fig. 5). When a similar approach was carried out with gpa2 mutant cells, there were no apparent differences in embedded conditions, liquid Spider medium, and liquid Lee's pH 7 medium between addition of dbcAMP and no addition. A slight filamentation can be seen only in SLAD medium amended with dbcAMP (Fig. 5). These results indicate that, in C. albicans, Gpa2 is not related to the cAMP pathway. This conclusion agrees with our inability to suppress gpa2 defects by the overexpression of EFG1 under the control of the regulatable PCK1 promoter (not shown).

FIG. 5.

Addition of exogenous cAMP to gpa2 mutants. Cells from the CAI4 (GPA2) and CCM12 (Δgpa2) strains were incubated in different media with (+cAMP) or without dbcAMP (10 mM final concentration). For solid media, SLAD plates were incubated at 37°C for 5 days, while for embedded conditions plates were incubated for 15 days at 22°C. For liquid assays log-phase cells were incubated in liquid Spider medium and pH 7 Lee's medium at 37°C. Pictures were taken after 8 h of incubation in the test medium.

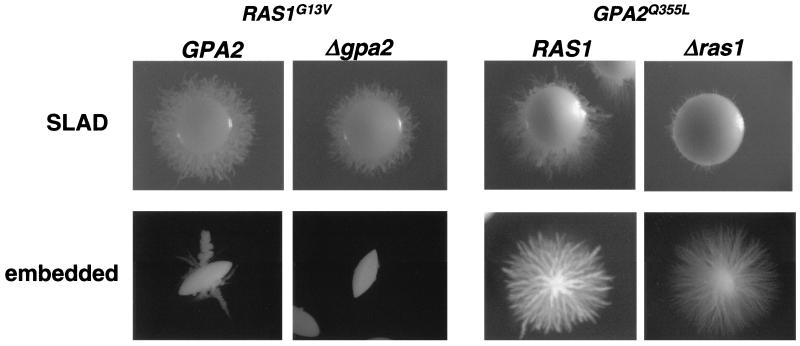

A hyperactive RAS1 allele can bypass some of the gpa2 defects.

A C. albicans homologue of Ras1 has been characterized recently (18, 30). This homologue has been shown to be required for the yeast-to-hypha switch through regulation of the MAP kinase and cAMP signaling pathways. To further examine the relationship between Ras1 and Gpa2, we made use of the dominant-active RAS1G13V allele, which carries a mutation that locks the G protein in the active state (18). The RAS1G13V and GPA2Q355L alleles were expressed in C. albicans gpa2 and ras1 mutants, respectively, and we studied their response to SLAD medium and embedded conditions. In our hands, the expression of the RAS1G13V allele in wild-type cells enhanced the formation of hyphae under filament-inducing conditions such as SLAD medium or even in noninducing conditions (not shown), as has been described elsewhere (12, 18, 42). Of note, the expression of the RAS1G13V hyperactive allele does not improve the ability of the cells to induce the hyphal switch in embedded conditions. We found that expression of the hyperactive RAS1G13V allele in gpa2 mutant cells suppressed the hyphal-formation defect in SLAD medium but not in embedded conditions (Fig. 6).

FIG. 6.

Epistasis analysis of RAS1 and GPA2. Wild-type and Δgpa2 cells were transformed with pCNB3-RAS1G13V, a plasmid expressing the hyperactive RAS1G13V allele under the control of the ACT1 promoter. Similarly, wild-type and Δras1 cells were transformed with pCNB3-GPA2Q355L, a plasmid expressing the hyperactive GPA2Q355L allele under the control of the ACT1 promoter. The resulting strains were grown in SLAD medium and embedded conditions as described for Fig. 2.

On the other hand, the expression of the GPA2Q355L allele in ras1 mutant cells does not suppress the ras1-associated inability to produce hyphal growth in SLAD medium. However, the expression of this gain-of-function allele enhances the ability of ras1 mutant cells to produce hyphal growth in embedded conditions (Fig. 6).

DISCUSSION

Studies of Gα subunits in several saprophytic and pathogenic fungi have revealed roles for these proteins in the regulation of virulence, morphogenesis, and sexual development (5, 24). A role for GPA2-like genes in morphogenesis in S. cerevisiae, where they are required for pseudohyphal differentiation (26, 34), and roles in the pathogenic fungi Cryptococcus neoformans (1) and U. maydis (41) have been well described. In this work, we have characterized the role of GPA2, a gene encoding a Gα subunit, in C. albicans morphogenesis. We found that cells lacking Gpa2 have a defect in hyphal development in response to specific environmental cues. Furthermore, constitutively active mutant allele GPA2Q355L, which is predicted to be locked in the active-conformation state, enhances hyphal growth in response to two of the stimuli tested, SLAD medium and embedded conditions. A second mutant, GPA2G354V, which is predicted to prevent the release from βγ and the interaction with signaling effectors, is a dominant-negative allele that impairs filamentation when expressed in a wild-type strain. Our data also indicate that Gpa2 plays a positive role in signaling. This conclusion agrees with the fact that in a phylogenetic tree produced by multiple alignment of the fungal Gα subunits, C. albicans Gpa2 is located in the same subgroup as S. cerevisiae Gpa2, U. maydis Gpa3, and C. neoformans Gpa1, among others, all of them having an activating role in signaling (data not shown).

We propose that Gpa2 acts upstream of the filamentous MAP kinase cascade. This model is consistent with the observation that the hyphal growth defect caused by homozygous deletion of the GPA2 gene is reversed by overexpression of HST7 (the MEK homologue of the MAP kinase cascade). We also found that the hyphal enhancement caused by the hyperactive GPA2Q355L allele in SLAD medium and in embedded conditions is prevented by homozygous deletion of CPH1 and HST7. Surprisingly, we found no evidence of Gpa2-mediated signaling through the cAMP-dependent cascade. Although the GPA2Q355L-dependent hyphal enhancement observed in SLAD medium is totally prevented by deletion of EFG1, a synergy in the promotion of hyphal development was observed when the GPA2Q355L allele was expressed in Efg1-defective cells in embedded conditions. In addition, in contrast to what has been observed with other Gα proteins (1, 25, 26, 34), we were unable to suppress the defect in hyphal promotion of gpa2 mutant cells by the addition of exogenous cAMP. Furthermore, we were unable to compensate the deletion of GPA2 by overexpression of EFG1 (not shown).

We have also analyzed the genetic interactions between the GTP-binding proteins Ras1 and Gpa2. In C. albicans, Ras1 has been proved to act through the cAMP and MAP kinase pathways for the promotion of filamentous growth (30). Our epistasis analysis using RAS1 and GPA2 hyperactive alleles further supports a role for Gpa2 upstream of the MAP kinase cascade. The expression in Gpa2-defective cells of the RAS1G13V allele suppresses the hyphal growth defect in SLAD medium, while the expression of the GPA2Q355L allele in Ras1-defective cells suppresses only slightly the defect in hyphal growth in the same growth conditions. It is well known that hyphal growth in SLAD medium is dependent on both cAMP-dependent and MAP kinase pathways (17).

Promotion of hyphal growth in embedded conditions deserves a separate comment. Previous data indicated that Cph1 was required for hyphal morphogenesis in response to matrix embedding (9). Our results agree with these observations. Furthermore, we found that the overexpression of HST7 enhances the response to embedded conditions, while the deletion of HST7 prevented hyphal formation in these conditions. All these data support a positive role for the MAP kinase in the promotion of hyphal growth in embedded conditions. Our data also suggest that a cAMP-dependent pathway has a negative role in hyphal growth in embedded conditions. We found that addition of cAMP impairs hyphal growth in embedded conditions and that cells defective in Efg1, which has been proposed to lie downstream of PKA, have an enhanced response to embedded conditions (in agreement with previous reports [21, 46]). The different effects of hyperactive Ras1 and Gpa2 gene alleles in embedded conditions could be also explained by assuming opposite roles for MAP kinase and cAMP-dependent pathways in embedded conditions. In a wild-type cell, Ras1- and Gpa2-mediated activation would result in a balanced activation of both MAP kinase and cAMP-dependent pathways that results in the development of hyphal growth in embedded conditions. Defective signaling through the cAMP-dependent pathway (as is produced by an efg1 deletion) would result in a release of the negative effects and then an enhancement of hyphal growth. Displacement of the signals through MAP kinase, either by specific overactivation of the MAP kinase pathway (due to, e.g., overexpression of HST7 or GPA2Q355L) or by inability to activate the cAMP pathway (which occurs in a ras1 mutant) would also result in an enhanced response.

In summary, we propose that in C. albicans Gpa2 is required for hyphal development in response to specific environmental cues and that this response involves the filament-inducing MAP kinase cascade. We also propose that a strict coordination with other effectors, such as Ras1, is required for a fine adjustment of the response to environmental changes.

Acknowledgments

We thank J. F. Ernst and A. J. P. Brown for sending us plasmids and strains, and Galar Fungail Consortium by helpful discussions.

This work was supported by EU contract QLK2CT 2000-00795 and CAM 08.2/0023/1998.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alspaugh, J. A., J. R. Perfect, and J. Heitman. 1997. Cryptococcus neoformans mating and virulence are regulated by the G-protein α subunit GPA1 and cAMP. Genes Dev. 11:3206-3217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Bahn, Y. S., and P. Sundstrom. 2001. CAP1, an adenylate cyclase-associated protein gene, regulates bud-hypha transitions, filamentous growth, and cyclic AMP levels and is required for virulence of Candida albicans. J. Bacteriol. 183:3211-3223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bockmühl, D. P., and J. F. Ernst. 2001. A potential phosphorylation site for an A-type kinase in the Efg1 regulator protein contributes to hyphal morphogenesis of Candida albicans. Genetics 157:1523-1530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bockmühl, D. P., S. Krishnamurthy, M. Gerads, A. Sonneborn, and J. F. Ernst. 2001. Distinct and redundant roles of the two protein kinase A isoforms Tpk1p and Tpk2p in morphogenesis and growth of Candida albicans. Mol. Microbiol 42:1243-1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bölker, M. 1998. Sex and crime: heterotrimeric G proteins in fungal mating and pathogenesis. Fungal Genet. Biol. 25:143-156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Borges-Walmsley, M. I., and A. R. Walmsley. 2000. cAMP signalling in pathogenic fungi: control of dimorphic switching and pathogenicity. Trends Microbiol. 8:133-141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Braun, B. R., and A. D. Johnson. 2000. Tup1, Cph1 and Efg1 make independent contributions to filamentation in Candida albicans. Genetics 155:57-67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brown, A. J., and N. A. Gow. 1999. Regulatory networks controlling Candida albicans morphogenesis. Trends Microbiol. 7:333-338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown, D. H., A. D. Giusani, X. Chen, and C. A. Kumamoto. 1999. Filamentous growth of Candida albicans in response to physical environmental cues and its regulation by the unique CZF1 gene. Mol. Microbiol. 34:651-662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Calderone, R. A., and W. A. Fonzi. 2001. Virulence factors of Candida albicans. Trends Microbiol. 9:327-335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chattaway, F., P. R. Wheeler, and J. O'Reilly. 1981. Involvement of adenosine 3′:5′-cyclic monophosphate in the germination of blastospores of Candida albicans. J. Gen. Microbiol. 123:233-240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen, J., S. Zhou, Q. Wang, X. Chen, T. Pan, and H. Liu. 2000. Crk1, a novel cdc2-related protein kinase, is required for hyphal development and virulence in Candida albicans. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:8696-8708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Csank, C., K. Schroppel, E. Leberer, D. Harcus, O. Mohamed, S. Meloche, D. Y. Thomay, and M. Whiteway. 1998. Roles of the Candida albicans mitogen-activated protein kinase homolog, Cek1p, in hyphal development and systematic candidiasis. Infect. Immun. 66:3317-3325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Delbrück, S., and J. F. Ernst. 1993. Morphogenesis-independent regulation of actin transcript levels in the pathogenic yeast Candida albicans. Mol. Microbiol. 10:859-866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.D'Souza, C. A., and J. Heitman. 2001. Conserved cAMP signalling cascades regulate fungal development and virulence. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 25:349-364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.El Barkani, A., O. Kurzai, W. A. Fonzi, A. Ramón, A. Porta, M. Frosch, and F. A. Mühlschlegel. 2000. Dominant active alleles of RIM101(PRR2) bypass the pH restriction on filamentation of Candida albicans. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:4635-4647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ernst, J. F. 2000. Transcription factors in Candida albicans environmental control of morphogenesis. Microbiology 146:1763-1774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Feng, Q., E. Summers, B. Guo, and G. Fink. 1999. Ras signaling is required for serum-induced hyphal differentiation in Candida albicans. J. Bacteriol. 181:6339-6346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fonzi, W. A., and M. Y. Irwin. 1993. Isogenic strain construction and gene mapping in Candida albicans. Genetics 134:717-728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gimeno, C. J., P. O. Ljungdahl, C. A. Styles, and G. R. Fink. 1992. Unipolar cell divisions in the yeast S. cerevisiae lead to filamentous growth: regulation by starvation and RAS. Cell 68:1077-1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Giusani, A. D., M. Vinces, and C. A. Kumamoto. 2002. Invasive filamentous growth of Candida albicans is promoted by Czf1p-dependent relief of Efg1p-mediated repression. Genetics 160:1749-1753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hoffman, C. S., and F. Wiston. 1987. A ten-minute DNA preparation from yeast efficiently releases autonomous plasmids for transformation of Escherichia coli. Gene 57:267-272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Köhler, J. R., and G. R. Fink. 1996. Candida albicans strains heterozygous and homozygous for mutations in mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling components have defects in hyphal development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:13223-13228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kronstad, J. W., A. De Maria, D. Funnell, R. D. Laidlaw, N. Lee, M. Moniz de Sá, and M. Ramesh. 1998. Signaling via cAMP in fungi: interconnections with mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways. Arch. Microbiol. 170:395-404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krüger, J., G. Loubradou, E. Regenfelder, A. Hartmann, and R. Kahmann. 1998. Crosstalk between cAMP and pheromone signalling pathways in Ustilago maydis. Mol. Gen. Genet. 260:193-198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kubler, E., H. U. Mosch, S. Rupp, and M. P. Lissanti. 1997. Gpa2p, a G-protein alpha-subunit, regulates growth and pseudohyphal development in Saccharomyces cerevisiae via a cAMP-dependent mechanism. J. Biol. Chem. 272:20321-20323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kunkel, T. A., J. D. Roberts, and R. A. Zakour. 1987. Rapid and efficient site-specific mutagenesis without phenotypic selection. Methods Enzymol. 154:367-383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leberer, E., D. Harcus, I. D. Broadbent, K. L. Clark, D. Dignard, K. Ziegelbauer, A. Schmidt, N. A. R. Gow, A. J. P. Brown, and D. Thomas. 1996. Signal transduction through homologs of the Ste20p and Ste7p protein kinases can trigger hyphal formation in the pathogenic fungus Candida albicans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:13217-13222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leberer, E., K. Ziegelbauer, A. Schmidt, D. Harcus, D. Dignard, J. Ash, L. Johnson, and D. Y. Thomas. 1997. Virulence and hyphal formation of Candida albicans require the Ste20p-like protein kinase CaCla4. Curr. Biol. 7:539-546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leberer, E., D. Harcus, D. Dignard, L. Johnson, S. Ushinsky, D. Y. Thomas, and K. Schroppel. 2001. Ras links cellular morphogenesis to virulence by regulation of the MAP kinase and cAMP signaling pathways in the pathogenic fungus Candida albicans. Mol. Microbiol. 42:673-687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee, K. L., H. R. Buckley, and C. C. Campbell. 1975. An amino acid liquid synthetic medium for the development of mycelial and yeast forms of Candida albicans. Sabouraudia 13:148-153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu, H., J. Köhler, and G. R. Fink. 1994. Suppression of hyphal formation in Candida albicans by mutation of a STE12 homolog. Science 266:1723-1726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lo, H. J., J. R. Köhler, B. DiDomenico, D. Loedenberg, A. Cacciapuoti, and G. R. Fink. 1997. Nonfilamentous C. albicans mutants are avirulent. Cell 90:939-949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lorenz, M. C., and J. Heitman. 1997. Yeast pseudohyphal growth is regulated by GPA2, a G protein α homolog. EMBO J. 16:7008-7018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Masters, S. B., R. T. Miller, M. H. Chi, F. H. Chang, B. Beiderman, N. G. López, and H. R. Bourne. 1989. Mutations in the GTP-binding site of Gsα alter stimulation of adenylate cyclase. J. Biol. Chem. 264:15467-15474. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miller, R. T., S. B. Masters, K. A. Sullivan, B. Beiderman, and H. R. Bourne. 1988. A mutation that prevents GTP-dependent activation of the α chain of Gs. Nature 334:712-715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Niimi, M. 1996. Dibutyril cyclic AMP-enhanced germ tube formation in exponentially growing Candida albicans cells. Fungal Genet. Biol. 20:79-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Niimi, M., K. Niimi, J. Tokunaga, and H. Nakayama. 1980. Changes in cyclic nucleotide levels and dimorphic transition in Candida albicans. J. Bacteriol. 142:1010-1014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Odds, F. C. 1988. Candida and candidiosis, 2nd ed. Bailliere Tindall, London, United Kingdom.

- 40.Pérez-Martín, J., J. A. Uria, and A. D. Johnson. 1999. Phenotypic switching in Candida albicans is controlled by a SIR2 gene. EMBO J. 18:2580-2592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Regenfelder, E., T. Spellig, A. Hartmann, S. Lauenstein, M. Bölker, and R. Kahmann. 1997. G proteins in Ustilago maydis: transmission of multiple signals? EMBO J. 16:1934-1942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rocha, C. R. C., K. Schroppel, D. Harcus, A. Marcil, D. Dignard, B. N. Taylor, D. Y. Thomas, M. Whiteway, and E. Leberer. 2001. Signaling through adenylyl cyclase is essential for hyphal growth and virulence in the pathogenic fungus Candida albicans. Mol. Biol. Cell 12:3631-3643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sadhu, C., D. Hoekstra, M. J. McEachern, S. I. Reed, and J. B. Hicks. 1992. A G-protein alpha subunit from asexual Candida albicans functions in the mating signal transduction pathway of Saccharomyces cerevisiae and is regulated by the a1-α2 repressor. Mol. Cell. Biol. 12:1977-1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sánchez-Martínez, C., and J. Pérez-Martín. Site-specific targeting of exogenous DNA into Candida albicans genome by use of the FLP recombinase. Mol. Genet. Genomics, in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 45.Sherman, F., G. R. Fink, and J. Hicks. 1986. Methods in yeast genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 46.Sonneborn, A., D. P. Bockmühl, and J. F. Ernst. 1999. Chlamydospore formation in Candida albicans requires the Efg1p morphogenetic regulator. Infect. Immun. 67:5514-5517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sonneborn, A., D. P. Bockmühl, M. Gerads, K. Kurpanek, D. Sanglard, and J. F. Ernst. 2000. Protein kinase A encoded by TPK2 regulates dimorphism of Candida albicans. Mol. Microbiol. 35:386-396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stoldt, V. R., A. Sonneborn, E. Leuker, and J. F. Ernst. 1997. Efg1p, an essential regulator of morphogenesis of the human pathogen Candida albicans, is a member of a conserved class of bHLH proteins regulating morphogenetic processes in fungi. EMBO J. 16:1982-1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Versele, M., J. H. de Winde, and J. M. Thevelein. 1999. A novel regulator of G protein signalling in yeast, Rgs2, downregulates glucose-activation of the cAMP pathway through direct inhibition of Gpa2. EMBO J 18:5577-5591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]