Abstract

Strict coordination of proliferation and programmed cell death (apoptosis) is essential for normal physiology. An imbalance in these two opposing processes results in various diseases including AIDS, neurodegenerative disorders, myelodysplastic syndromes, ischemia/reperfusion injury, cancer, autoimmune disease, among others. Objective and quantitative noninvasive imaging of apoptosis would be a significant advance for rapid and dynamic screening as well as validation of experimental therapeutic agents. Here, we report the development of a recombinant luciferase reporter molecule that when expressed in mammalian cells has attenuated levels of reporter activity. In cells undergoing apoptosis, a caspase-3-specific cleavage of the recombinant product occurs, resulting in the restoration of luciferase activity that can be detected in living animals with bioluminescence imaging. The ability to image apoptosis noninvasively and dynamically over time provides an opportunity for high-throughput screening of proapoptotic and antiapoptotic compounds and for target validation in vivo in both cell lines and transgenic animals.

A majority of clinical imaging is relegated to obtaining anatomical information based on differences in physical parameters to generate image contrast. Significant efforts recently have focused on developing approaches to use noninvasive imaging technologies to obtain information related to specific molecular events. These efforts have been focused on reporting of gene expression (1–5) or extracellular proteolytic activity by using synthetic fluorescent probes (6–8). However, real-time detection of a single specific intracellular enzyme or pathway in vivo has been largely elusive to date. Proteases play a major role in biological processes including tissue remodeling, vascular hemostasis, digestion, protein turnover and maturation as well as apoptosis. Apoptosis is a physiologic process in normal development and homeostasis of multicellular organisms. Evaluation of therapeutic agents against pathologies involving an imbalance in apoptosis (e.g., benign prostate hyperplasia) would greatly benefit from a method to noninvasively image the specific molecular mediators of apoptosis. Because cytosolic caspases play a central role in mediating the initiation and propagation of the apoptotic cascade, the ability to noninvasively image the activation of these zymogens would provide an opportunity to evaluate therapeutic interventions dynamically in living animals.

In an effort to develop a platform molecular reporter construct wherein the presence of a specific protease activity can be imaged, we have constructed a series of hybrid recombinant reporter molecules (Fig. 1a) wherein the activity of the reporter can be silenced by fusion with the estrogen receptor regulatory domain (ER) (Fig. 1b). Once adequate silencing of the reporter's enzymatic activity was achieved, the inclusion of a protease cleavage site for caspase-3 (DEVD) between these two domains allowed for protease-mediated activation of the reporter molecule after separation from the silencing domain (i.e., ER). Because most cells activate caspase-3 during apoptosis, this engineered chimeric polypeptide was investigated as a novel molecular-based reporter for noninvasive detection of apoptosis by using bioluminescence imaging (BLI). Stable human glioma cell lines were constructed expressing luciferase (Luc), Luc with single or double ER fusions as shown (Fig. 1a). In vitro studies using the above cell lines revealed that the double ER fusion molecule had the greatest attenuation of Luc activity that could be activated on caspase-3 induction. Furthermore, in vivo studies using this cell line in a mouse revealed that caspase-3 by activation on tumor necrosis factor α-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) treatment could be imaged noninvasively by using BLI. The ability to image caspase-3 activation noninvasively provides a unique tool for the evaluation of therapeutic efficacy of experimental therapeutic agents as well as for studies on the role of apoptosis in various disease processes.

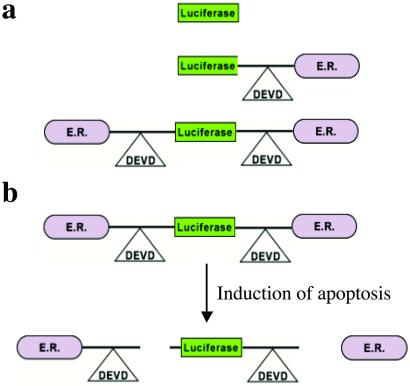

Fig 1.

The strategy for imaging of apoptosis. (a) Cellular expression of a recombinant cDNA encoding reporter molecules was investigated. Shown are the control Luc molecule, Luc fused to a carboxyl-terminal ER, and finally a Luc molecule with ERs at the amino and carboxyl termini. (b) Chimeric polypeptides consisting of a reporter molecule fused to the ER resulted in the most efficient silencing of the reporter activity. Inclusion of a protease cleavage site between these domains provided for protease-mediated activation of the reporter molecule after separation of the silencing domains (i.e., ER). For example, inclusion of the DEVD sequence (a caspase-3 cleavage site) between ER and Luc results in the release of Luc from the silencing domain from the amino and the carboxyl termini in a caspase-3-dependent manner. Because most cells activate caspase-3 during apoptosis, this reporter construct can be used for reporting (imaging) of apoptosis. The cleavage site of this molecular construct can be modified to “report” on the activation of a variety of proteases for detection of proteolytic activity in both cells and transgenic animals by using noninvasive imaging methodologies.

Methods

Construction of Hybrid Molecules.

Using PCR mutagenesis, three versions of the Luc molecule were constructed. The first consisted of the WT firefly Luc gene; a second version was a fusion between the coding sequence for Luc gene and the ER (residues 281–599 of the modified mouse estrogen receptor sequence; ref. 9), which also contained a DEVD sequence inserted between the ER and the Luc sequence (Luc-DEVD-ER). A third hybrid (ER-DEVD-Luc-DEVD-ER) was constructed wherein the ER was present at the amino and carboxyl termini with the DEVD sequence intervening the two domains on either side. The hybrid coding sequences were cloned into the expression vector pZ (kindly provided by the Genetics Institute, Cambridge, MA), which drives transcription of the inserted coding sequence by using the adenoviral major late promoter with the neomycin-resistance gene as a bicistronic message.

Stable Cell Lines.

The constructs described above were stably transfected into D54 (human glioma) cells by using Fugene (Roche Diagnostics), and the resulting stable clones were selected by using 200 μg/ml G418 (Invitrogen) and characterized on isolation. Specific clones were identified and selected for further study based on similarity in expression levels of the recombinant protein.

In Vitro Studies.

Studies involving induction of apoptosis using TRAIL were accomplished by using 200 ng/ml TRAIL or as specified (prepared as described in ref. 10) and incubated for ≈3 h. Experiments using ZVAD-fmk, a caspase inhibitor, were accomplished by preincubating cells with the inhibitor (20 μM, Calbiochem) for 2 h before TRAIL treatment.

Western Blot Analysis.

Cell extracts were prepared for Western blot analysis using reporter lysis buffer (Promega) and resolved on SDS/PAGE followed by blotting onto nitrocellulose membranes. The membranes were blocked in 5% nonfat powdered milk and probed with specific antibodies against Luc and caspase-3 by using standard techniques.

In Vivo Studies.

D54 human glioma cells constitutively expressing the ER-DEVD-Luc-DEVD-ER reporter molecule were grown as monolayers in RPMI supplemented with 10% FCS and 200 μg/ml G418 in a 95:5% air/CO2 atmosphere. Subcutaneous D54 tumors were induced in athymic nude mice by implantation of 105 cells suspended in 0.1 ml. Before imaging, animals bearing palpable (≥5 mm) tumors were anesthetized with a 2% isofluorane/air mixture and given a single i.p. dose of 150 mg/kg luciferin in normal saline. BLI was accomplished between 10 and 20 min postluciferin administration (11). During image acquisition, isofluorane anesthesia was maintained by using a nose cone delivery system, and animal body temperature was regulated by using a temperature-controlled bed. A gray-scale body image was collected followed by acquisition and overlay of a pseudocolor image representing the spatial distribution of the detected photons emitted from the active Luc within the tumor cells. A signal averaging time of 1 min was used for acquisition of the luminescent image. BLI was accomplished before and again at 60–75 min after a slow 50-μl intratumoral infusion of PBS (n = 5) or TRAIL (1 mg/ml, n = 5). Signal intensity was quantified as the sum of all detected photon counts within a region of interest prescribed over the tumor site. Several tumors from each of the two groups were harvested and homogenized in PBS after the final imaging time point for Western blot analysis.

Data Analysis.

A percentage change in photon counts from tumors before and after PBS or TRAIL treatment were calculated. Values of the mean percentage change were presented as mean ± SEM for each of the two groups of animals. Statistical comparisons between the sham- and TRAIL-treated animals were made by using the unpaired Student's t test. A probability value of P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results and Discussion

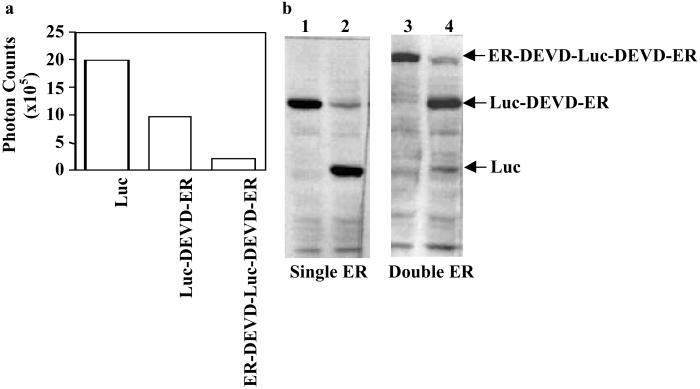

The ER has been used to regulate the function of various proteins including myc, dhfr, and fos (12–14). In contrast to the above examples, none of which involved regulation of a catalytic enzyme, the present study required that the ER silence the Luc enzyme. We hypothesized that this would occur through sequestration and stearic inhibition of the catalytic site mediated by binding of heat shock proteins to the fusion protein. To systematically evaluate this approach, we initially constructed a molecule consisting of a single ER (Luc-DEVD-ER) (Fig. 1) and compared the signal intensity (photon counts) from D54 glioma cells expressing this construct with cells expressing similar levels of “free” Luc. Attachment of a single ER to the carboxyl-terminal end of Luc was found to attenuate the signal intensity by 50% compared with free Luc (Fig. 2a). A subsequent analysis of cell lysates revealed that caspase-3 induction resulted in cleavage at the DEVD site, resulting in the separation of Luc from the ER silencing domain (Fig. 2b). In an effort to further improve on the silencing of Luc activity, an additional ER was added, this time to the amino-terminal end of the Luc. This dual-ER reporter molecule (ER-DEVD-Luc-DEVD-ER) (Fig. 1) resulted in a chimeric polypeptide with a much improved silencing of Luc (85–90%; Fig. 2a). Induction of apoptosis in cells expressing this polypeptide resulted in its cleavage to an expected 96-kDa fragment consisting of Luc (61 kDa) with a single ER (35 kDa), as well as free Luc (Fig. 2b). This reporter was selected for further study because of its enhanced ability to attenuate Luc activity.

Fig 2.

In vitro demonstration of the silencing and apoptotic-induced activation of the reporter molecule. (a) Photon counts obtained from cultured D54 glioma cells stably expressing containing Luc, Luc-DEVD-ER, and ER-DEVD-Luc-DEVD-ER reporter molecules were acquired by using the BLI system. The single and double ER fusion molecules were found to attenuate the signal from Luc by ≈50% and 90%, respectively, as compared with native Luc. (b) A Western blot obtained by using a Luc-specific antibody demonstrates that, in response to an apoptosis-inducing agent (TRAIL, lanes 2 and 4), both the Luc-DEVD-ER (lanes 1 and 2) and the ER-DEVD-Luc-DEVD-ER constructs (lanes 3 and 4) were cleaved to yield the Luc protein (61 kDa). Also present was an intermediate cleavage fragment of the two ER-containing molecules to the one ER-containing molecule (lane 4, 96 kDa).

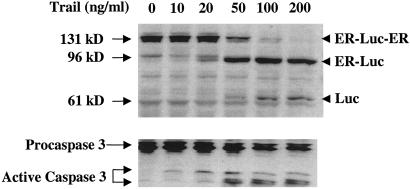

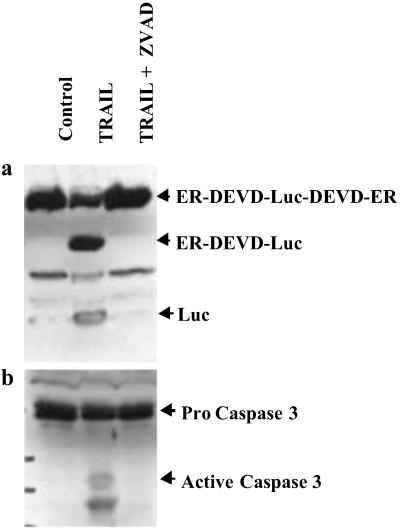

To evaluate the dynamics of the cleavage process, we induced apoptosis in D54 cells stably expressing the ER-DEVD-Luc-DEVD-ER construct (D54-LucER) with increasing concentrations of TRAIL. This study revealed that the number of cells undergoing apoptosis increased with increasing concentrations of TRAIL (data not shown). A concurrent increase in levels of active caspase-3 (Fig. 3) corresponded to the cleavage of the 131-kDa (ER-DEVD-Luc-DEVD-ER) polypeptide to a 96-kDa polypeptide (ER-DEVD-Luc and Luc-DEVD-ER) and finally to the 61-kDa polypeptide (Luc) in a dose-dependent manner. Evidence that the above polypeptides were caused by activation of caspase-3 during apoptosis was obtained from D54-LucER cells treated with TRAIL alone or in the presence of the caspase inhibitor ZVAD-fmk. Induction of apoptosis in response to TRAIL corresponded to activation of caspase-3 and cleavage of the 131-kDa polypeptide to the 96- and 61-kDa polypeptides (Fig. 4a). Inhibition of TRAIL-induced apoptosis by inhibiting the activation of caspases with ZVAD-fmk (Fig. 4b) also resulted in failure to cleave the 131-kDa polypeptide, indicating that the 96- and the 61-kDa polypeptides were derived from cleavage of the DEVD sequence. To further substantiate that cleavage at the DEVD site was mediated by caspase-3 and not a different caspase, we used caspase-3-deficient MCF-7 cells. The reporter construct when stably expressed in MCF-7 cells failed to get cleaved on induction of apoptosis by TRAIL despite the fact that the cells appeared apoptotic. In contrast when the caspase-3 cDNA was coexpressed in MCF-7 cells, induction of apoptosis by TRAIL resulted in a concurrent cleavage of the reporter to yield free Luc. These results confirm that introduction of the DEVD site within the reporter results in an inducible reporter that is specific for caspase-3.

Fig 3.

Dose-dependent induction of apoptosis in D45 cells expressing the ER-DEVD-Luc-DEVD-ER reporter construct revealed a correlation of caspase-3 activation with cleavage of Luc from the ER silencing domains. (Upper) Using a Luc-specific antibody, the ER-DEVD-Luc-DEVD-ER molecule (131 kDa) is cleaved to a 96-kDa molecule (ER-DEVD-Luc or Luc-DEVD-ER) and subsequently to Luc (61 kDa) when apoptosis is occurring. (Lower) The cleavage event correlated with the conversion of inactive zymogen caspase-3 (32 kDa) to active caspase-3 (17 and 13 kDa).

Fig 4.

In vitro demonstration of the specificity of the reporter molecule in intact cells. Cultured D54 cells expressing the ER-DEVD-Luc-DEVD-ER reporter molecule were treated with TRAIL and TRAIL + ZVAD, a specific inhibitor of caspase-3. (a) A Western blot was obtained on cell extracts by using a Luc-specific antibody, which demonstrated inhibition of cleavage could be accomplished by inhibition of caspase-3. (b) Cleavage of the reporter molecule during apoptosis was also found to correlate with the conversion of inactive zymogen caspase (32 kDa) to active caspase-3 (17 kDa and 13 kDa).

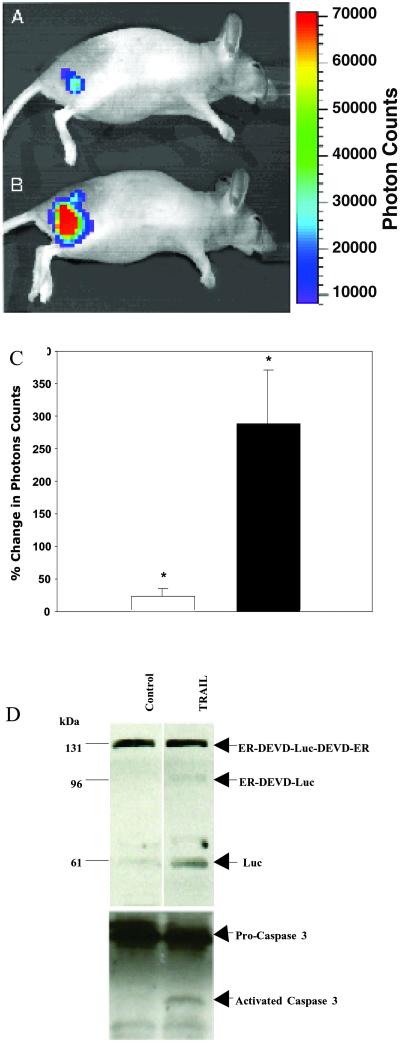

To investigate the utility of our strategy for in vivo imaging of apoptosis, D54-LucER-derived s.c. tumors were imaged before and after TRAIL (n = 5) or PBS (n = 5) treatment with BLI. Consistent with the in vitro studies (Fig. 2a), low levels of bioluminescence were detected in tumor-bearing animals (Fig. 5A). Induction of apoptosis using TRAIL resulted in a rapid increase in photon counts from in vivo tumors (Fig. 5B) as compared with matched controls that were PBS treated. This increase in bioluminescence during apoptosis was approximately 3-fold when data from five animals were averaged in contrast to PBS treatment of the tumors, which resulted in a minimal change over pretreatment levels (Fig. 5C). In vivo assessment of apoptosis in tissue samples is currently accomplished by using histological methods (e.g., terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase-mediated dUTP end labeling) and is considered the gold standard for the detection of apoptosis. Because of engulfment by neighboring cells and loss of apoptotic cells during manipulation, this method typically underestimates the percentage of cells undergoing apoptosis. The apoptotic process is a dynamic continuum of specific molecular events and the technology described here specifically enables measurement of the levels of active caspase-3 at a specific time. In addition, because Luc has a functional half-life of ≈3 min (at 37°C, our results; data not shown), the bioluminescence activity observed at a given moment is not expected to be cumulative but rather a snapshot of the levels of active caspase-3. Our approach allows the measurement of caspase-3 levels to be followed dynamically in real time in living tissue.

Fig 5.

In vivo imaging of caspase-3 activation. In vivo bioluminescence image of a mouse with a s.c. D54-LucER glioma obtained before (A) and 60–75 min after (B) TRAIL treatment. Note the significant increase in photons collected from the same animal after TRAIL treatment. (C) Average percentage change in photon output in PBS-treated (open bar, 21 ± 28%) and TRAIL-treated (filled bar, 287 ± 186% P < 0.04) D54-LucER glioma tumors (n = 5 animals per group) that revealed an ≈3-fold mean increase in bioluminescence on apoptosis induction. Error bars represent SD. (D) Western blot analysis of PBS- and TRAIL-treated excised tumors using antibodies specific for Luc or caspase-3 revealed activation of caspase-3 in TRAIL-treated tumors but not in control (PBS-treated) tumors. A concomitant cleavage (activation) of the 131-kDa reporter was observed in TRAIL-treated tumors.

To demonstrate that the increase in bioluminescence was caused by proteolytic activation of the reporter, tumor tissues from PBS- and TRAIL-treated animals were collected and analyzed. The ER-DEVD-Luc-DEVD-ER polypeptide was found to be cleaved to the 96-kDa (ER-DEVD-Luc and Luc-DEVD-ER) and 61-kDa polypeptides (Luc) in tumors treated with TRAIL but not those treated with PBS (Fig. 5D). The presence of active caspase-3 in TRAIL-treated in vivo tumors provided further support that TRAIL-induced apoptosis resulted in activation of caspase-3, resulting in proteolytic activation of the reporter construct, which could be noninvasively detected in real time in living animals.

Conclusion

The field of molecular imaging (15) involves the use of many different modalities including MR (5, 8, 10, 11, 16–18), radionuclide (1, 3, 29–35), x-ray computed tomography (36, 37), and optical methods (5, 7, 11, 38–50). The current state of the art does not allow detection of specific caspases in vivo. The hybrid reporter molecule described above represents a significant advance for investigating proapoptotic and antiapoptotic events in intact cells and animals. In addition, the ability to substitute the caspase-3 cleavage site with a site for other proteases including other caspases provides a unique opportunity to study the action of clinically important proteases and therapeutic modulation of their activities in intact animals. The availability of this reporter molecule also facilitates the development of transgenic animals wherein a specific proteolytic event can be noninvasively monitored in a tissue-specific manner. Moreover, the above strategy could also be adapted for use in other imaging modalities such as positron-emission tomography wherein the Luc coding sequence could be replaced by the herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase coding sequence (1). Taken together, the versatility of this approach will significantly impact the process of drug discovery (i.e., high-throughput screening to identify protease inhibitors) as well as evaluation of therapeutic efficacy in vivo (i.e., using xenograft or transgenic models).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Cancer Institute Grants R24CA83099, 5P20CA86442, 1P50CA93990, and 1R43CA91448-01 and the Michigan Life Sciences Corridor 1773.

Abbreviations

BLI, bioluminescence imaging

ER, estrogen receptor regulatory domain

Luc, luciferase

TRAIL, tumor necrosis factor α-related apoptosis-inducing ligand

References

- 1.Gambhir S. S., Herschman, H. R., Cherry, S. R., Barrio, J. R., Satyamurthy, N., Toyokuni, T., Phelps, M. E., Larson, S. M., Balatoni, J., Finn, R., et al. (2000) Neoplasia 2, 118-138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weissleder R., Moore, A., Mahmood, U., Bhorade, R., Benveniste, H., Chiocca, E. A. & Basilion, J. P. (2000) Nat. Med. 6, 351-355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ponomarev V., Doubrovin, M., Lyddane, C., Beresten, T., Balatoni, J., Bornman, W., Finn, R., Akhurst, T., Larson, S., Blasberg, R., et al. (2001) Neoplasia 3, 480-488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Doubrovin M., Ponomarev, V., Beresten, T., Balatoni, J., Bornmann, W., Finn, R., Humm, J., Larson, S., Sadelain, M., Blasberg, R. & Tjuvajev, J. G. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 9300-9305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rehemtulla A., Hall, D. E., Stegman, L. D., Chen, G., Bhojani, M. S., Chenevert, T. L. & Ross, B. D. (2002) Mol. Imaging 1, 43-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tung C. H., Mahmood, U., Bredow, S. & Weissleder, R. (2000) Cancer Res. 60, 4953-4958. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sameni M., Moin, K. & Sloane, B. F. (2000) Neoplasia 2, 496-504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bremer C., Tung, C. H. & Weissleder, R. (2001) Nat. Med. 7, 743-748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Littlewood T. D., Hancock, D. C., Danielian, P. S., Parker, M. G. & Evan, G. I. (1995) Nucleic Acids Res. 23, 1686-1690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chinnaiyan A. M., Prasad, U., Shankar, S., Hamstra, D. A., Shanaiah, M., Chenevert, T. L., Ross, B. D. & Rehemtulla, A. (2000) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97, 1754-1759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rehemtulla A., Stegman, L. D., Cardozo, S. J., Gupta, S., Hall, D. E., Contag, C. H. & Ross, B. D. (2000) Neoplasia 2, 491-495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eilers M., Picard, D., Yamamoto, K. R. & Bishop, J. M. (1989) Nature 340, 66-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Superti-Furga G., Bergers, G., Picard, D. & Busslinger, M. (1991) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 88, 5114-5118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Israel D. I. & Kaufman, R. J. (1993) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90, 4290-4294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoffman J. M. (2000) Neoplasia 2, 5-8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Evelhoch J. L., Gillies, R. J., Karczmar, G. S., Koutcher, J. A., Maxwell, R. J., Nalcioglu, O., Raghunand, N., Ronen, S. M., Ross, B. D. & Swartz, H. M. (2000) Neoplasia 2, 152-165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kurhanewicz J., Vigneron, D. B. & Nelson, S. J. (2000) Neoplasia 2, 166-189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaplan O., Firon, M., Vivi, A., Navon, G. & Tsarfaty, I. (2000) Neoplasia 2, 365-377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fleige G., Nolte, C., Synowitz, M., Seeberger, F., Kettenmann, H. & Zimmer, C. (2001) Neoplasia 3, 489-499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bogdanov A., Matuszewski, L., Bremer, C., Petrovsky, A. & Weissleder, R. (2002) Mol. Imaging 1, 16-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hogemann D., Josephson, L., Weissleder, R. & Basilion, J. P. (2000) Bioconjugate Chem. 11, 941-946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gillies R. J., Bhujwalla, Z. M., Evelhoch, J., Garwood, M., Neeman, M., Robinson, S. P., Sotak, C. H. & Van Der Sanden, B. (2000) Neoplasia 2, 139-151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bhujwalla Z. M., Artemov, D., Natarajan, K., Ackerstaff, E. & Solaiyappan, M. (2001) Neoplasia 3, 143-153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pilatus U., Ackerstaff, E., Artemov, D., Mori, N., Gillies, R. J. & Bhujwalla, Z. M. (2000) Neoplasia 2, 273-279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chenevert T. L., Stegman, L. D., Taylor, J. M., Robertson, P. L., Greenberg, H. S., Rehemtulla, A. & Ross, B. D. (2000) J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 92, 2029-2036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stegman L. D., Rehemtulla, A., Beattie, B., Kievit, E., Lawrence, T. S., Blasberg, R. G., Tjuvajev, J. G. & Ross, B. D. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 96, 9821-9826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Walter G., Barton, E. R. & Sweeney, H. L. (2000) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97, 5151-5155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Auricchio A., Zhou, R., Wilson, J. M. & Glickson, J. D. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97, 5205-5210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tjuvajev J. G., Joshi, A., Callegari, J., Lindsley, L., Joshi, R., Balatoni, J., Finn, R., Larson, S. M., Sadelain, M. & Blasberg, R. G. (1999) Neoplasia 1, 315-320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gambhir S. S., Barrio, J. R., Phelps, M. E., Iyer, M., Namavari, M., Satyamurthy, N., Wu, L., Green, L. A., Bauer, E., MacLaren, D. C., et al. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 96, 2333-2338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mankoff D. A., Dehdashti, F. & Shields, A. F. (2000) Neoplasia 2, 71-88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dyszlewski M., Blake, H. M., Dahlheimer, J. L., Pica, C. M. & Piwnica-Worms, D. (2002) Mol. Imaging 1, 24-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hackman T., Doubrovin, M., Balatoni, J., Beresten, T., Ponomarev, V., Beattie, B., Finn, R., Bornmann, W., Blasberg, R. & Tjuvajev, J. G. G. (2002) Mol. Imaging 1, 36-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hay R. V., Cao, B., Skinner, R. S., Wang, L.-M., Su, Y., Resau, J. H., Woude, G. F. V. & Gross, M. D. (2002) Mol. Imaging 1, 56-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Burt B. M., Humm, J. L., Kooby, D. A., Squire, O. D., Mastorides, S., Larson, S. M. & Fong, Y. (2001) Neoplasia 3, 189-195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kristensen C. A., Hamberg, L. M., Hunter, G. J., Roberge, S., Kierstead, D., Wolf, G. L. & Jain, R. K. (1999) Neoplasia 1, 518-525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Paulus M. J., Gleason, S. S., Kennel, S. J., Hunsicker, P. R. & Johnson, D. K. (2000) Neoplasia 2, 62-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sokol D. L., Zhang, X., Lu, P. & Gewirtz, A. M. (1998) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95, 11538-11543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jacobs A., Dubrovin, M., Hewett, J., Sena-Esteves, M., Tan, C. W., Slack, M., Sadelain, M., Breakefield, X. O. & Tjuvajev, J. G. (1999) Neoplasia 1, 154-161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fujimoto J. G., Pitris, C., Boppart, S. A. & Brezinski, M. E. (2000) Neoplasia 2, 9-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tromberg B. J., Shah, N., Lanning, R., Cerussi, A., Espinoza, J., Pham, T., Svaasand, L. & Butler, J. (2000) Neoplasia 2, 26-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vajkoczy P., Ullrich, A. & Menger, M. D. (2000) Neoplasia 2, 53-61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ramanujam N. (2000) Neoplasia 2, 89-117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pedersen M. W., Holm, S., Lund, E. L., Hojgaard, L. & Kristjansen, P. E. (2001) Neoplasia 3, 80-87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kragh M., Quistorff, B., Lund, E. L. & Kristjansen, P. E. (2001) Neoplasia 3, 324-330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vordermark D., Shibata, T. & Martin Brown, J. (2001) Neoplasia 3, 527-534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Edinger M., Sweeney, T. J., Tucker, A. A., Olomu, A. B., Negrin, R. S. & Contag, C. H. (1999) Neoplasia 1, 303-310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Contag C. H., Jenkins, D., Contag, P. R. & Negrin, R. S. (2000) Neoplasia 2, 41-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Padera T. P., Stoll, B. R., So, P. T. C. & Jain, R. K. (2002) Mol. Imaging 1, 9-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hawrysz D. J. & Sevick-Muraca, E. M. (2000) Neoplasia 2, 388-417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]