Abstract

The complement system is an important component of the innate immune response to bacterial pathogens, including Streptococcus pneumoniae. The classical complement pathway is activated by antibody–antigen complexes on the bacterial surface and has been considered predominately to be an effector of the adaptive immune response, whereas the alternative and mannose-binding lectin pathways are activated directly by bacterial cell surface components and are considered effectors of the innate immune response. Recently, a role has been suggested for the classical pathway during innate immunity that is activated by natural IgM or components of the acute-phase response bound to bacterial pathogens. However, the functional importance of the classical pathway for innate immunity to S. pneumoniae and other bacterial pathogens, and its relative contribution compared with the alternative and mannose-binding lectin pathways has not been defined. By using strains of mice with genetic deficiencies of complement components and secretory IgM we have investigated the role of each complement pathway and natural IgM for innate immunity to S. pneumoniae. Our results show that the proportion of a population of S. pneumoniae bound by C3 depends mainly on the classical pathway, whereas the intensity of C3 binding depends on the alternative pathway. Furthermore, the classical pathway, partially targeted by the binding of natural IgM to bacteria, is the dominant pathway for activation of the complement system during innate immunity to S. pneumoniae, loss of which results in rapidly progressing septicemia and impaired macrophage activation. These data demonstrate the vital role of the classical pathway for innate immunity to a bacterial pathogen.

The Gram-positive pathogen Streptococcus pneumoniae is a serious bacterial pathogen of humans, causing the majority of cases of pneumonia and many cases of meningitis and septicemia (1). Nasopharyngeal colonization with S. pneumoniae is present in 25% of the population, yet only a small proportion of these develop pneumonia, of which a minority develop septicemia. The explanation for the relative rarity of pneumonia and septicemia is poorly understood but is likely to be influenced by the host's innate immune response to S. pneumoniae. An important component of innate immunity to bacterial pathogens is the complement system, which is activated by three enzyme cascades: the classical, the alternative, and the mannose-binding lectin (MBL) pathways (2). There is strong evidence that the complement system is important for innate immunity to S. pneumoniae (3–7), but which of the three complement pathway(s) has the major role in host defense has not been defined. The classical complement pathway is activated by the protein C1q binding to the Fc portion of antibody–antigen complexes on the bacterial surface and has been considered predominately to be an effector of the adaptive immune response, whereas the alternative and MBL pathways are activated directly by bacterial cell surface components and are considered effectors of the innate immune response (2). In keeping with this paradigm, the alternative pathway in a guinea pig model of S. pneumoniae infection is the dominant complement pathway required for innate immunity (8). However, C1q can bind either directly to bacteria (9–13) or indirectly to bacterial immune complexes in which the antibody is (so-called) natural IgM, which is the product of the inherited IgM repertoire (14), or to the acute-phase reactant C reactive protein (CRP) bound to phosphorylcholine on the bacterial surface (7, 15). These routes to activate the classical pathway may be considered to be part of the innate immune system. Mice deficient in C4, a component of the classical and MBL pathways, were more susceptible to infection by group B Streptococcus and S. pneumoniae, even when the mouse immune system was naïve to these organisms (7, 16). This evidence suggests that the classical pathway may be important for innate as well as adaptive immunity, but is not conclusive as studies using C4-deficient mice cannot distinguish between the effects of complement activation by the classical and MBL pathway.

We investigated the role of each complement pathway in innate immunity to S. pneumoniae by using strains of mice with genetic deficiencies of the following complement components: C1q (C1qa−/−), affecting the classical pathway; factor B (Bf−/−), affecting the alternative pathway; C3 (C3−/−), affecting all three complement pathways; C4 (C4−/−), affecting both the classical and MBL pathways; secretory IgM (μs−/−), affecting natural IgM; and both C1q and factor B (C1qa−/−.Bf−/−), affecting the classical and alternative pathways but not the MBL pathway. Our results demonstrate that the classical pathway, partially mediated by binding of natural IgM to bacteria, is the most important portion of the complement system for innate immunity to S. pneumoniae.

Materials and Methods

Bacteria.

The S. pneumoniae capsular serotype 2 strain (D39) was used for the majority of the experiments in this study. Additional strains used were the isogenic unencapsulated D39 strain (ΔD−; ref. 17), the capsular serotype 3 strain (0100993, obtained from GlaxoSmithKline plc), and the capsular serotypes type 6B and 4 strains (M158 and M313, gifts from Brian Spratt, Imperial College London, London). S. pneumoniae strains were cultured at 37°C and 5% CO2 on Columbia agar supplemented with 5% horse blood or in Todd-Hewitt broth supplemented with 0.5% yeast extract (THY). Strains were stored at −70°C as aliquots of THY broth culture (OD580 = 0.3–0.4) in 10% glycerol.

Animals and Sera.

The following immune-deficient mice backcrossed to the C57BL/6 background for 10 generations were used for this study: C1qa−/− (18); Bf−/− (19); C4−/− (20); C3−/− (16); and μs−/− (21). Mice with combined deficiencies of C1q and factor B (C1qa−/−.Bf−/−) were obtained by crossbreeding C1qa−/− and Bf−/− mice. Studies were performed according to the institutional guidelines for animal use and care. Blood samples were obtained by terminal exsanguination, and serum was stored at −70°C as single-use aliquots of 40–100 μl from individual mice. Mice were kept in filter cages or with individual air supplies and had received no known exposure to S. pneumoniae. To confirm this, 1 in 50 dilutions of sera from 23 mice (12 wild-type, 3 C1qa−/−, 3 μs−/−, 2 Bf−/−, and 3 C1qa−/−.Bf−/− mice) were tested for the presence of anti-S. pneumoniae IgG by using an IgG-binding assay described below. In sera obtained from mice that survived challenge with strain D39, 31.4% (SD = 18%) of S. pneumoniae were positive for IgG, whereas the figure for bacteria incubated in test sera was 0.94% (SD = 0.70%), and for physiologically buffered saline (PBS), it was 0.59% (SD = 0.24%), confirming that mice used for these experiments had no prior infection with S. pneumoniae.

C3 and Antibody-Binding Assays.

For assays of C3 deposition on the surface of S. pneumoniae, bacteria stocks were thawed and washed by centrifugation at 20,000 × g for 6 min, followed by resuspension in PBS. Bacterial aliquots were pelleted and resuspended in 10 μl of mouse serum, incubated for 1–30 min at 37°C, washed twice with 500 μl of PBS/0.1% Tween 20, and resuspended in 50 μl of PBS/0.1% Tween 20 containing a 1:300 dilution of fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated polyclonal goat anti-mouse C3 antibody (ICN Cappel). After incubation on ice for 30 min, the bacteria were washed with 500 μl of PBS/0.1% Tween 20 and resuspended in 500 μl of PBS for flow cytometry analysis. Assays for deposition of IgG or IgM on the surface of S. pneumoniae were performed by using a similar method except that the bacteria were resuspended in PBS/0.1% Tween 20 containing a 1:100 dilution of phycoerythrin-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG or anti-mouse IgM (both from Jackson ImmunoResearch) instead of anti-mouse C3 antibody.

Infection Model Experiments.

Mice aged from 8 to 12 weeks were used for experimental infections, and within each experiment, groups of mice were matched for age and sex. Mice were inoculated with defrosted and appropriately diluted (in PBS) stocks of S. pneumoniae strains by the intranasal (i.n., under halothane anesthesia, pneumonia model, 40-μl inoculum), i.p. (systemic model, 100-μl inoculum), or i.v. (via the tail vein, 100-μl inoculum) routes. For survival curves, mice were killed when they exhibited signs of severe disease from which recovery was unlikely (22). For experiments in which bacterial cfu in target organs were calculated and/or cells were recovered for immunological analysis, target organs (lungs, spleen, mesenteric lymph nodes) were homogenized in 3.0 ml of RPMI medium 1640, and heparinized blood and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid were obtained as described (23). Bacterial cfu were calculated by serial dilution and plating of aliquots of the homogenized organ suspensions, blood, and BAL fluid. The remaining cells in the organ suspension and BAL fluid were prepared for analysis of cell surface and intracellular markers as described (23).

Analysis of Cell Surface and Intracellular Antigens.

Cells recovered from target organs were stained with rat anti-mouse Abs to CD4, CD8, and CD45RB (PharMingen) for lymphocyte staining, or CD80 and I-A/I-E MHC class II (PharMingen) for macrophage staining, according to described protocols (24). Intracellular cytokine levels were calculated by staining recovered cells for CD4, CD8, γ-IFN, and IL-4 levels by using described methods (24).

Flow Cytometry.

Samples for C3, IgM, IgG, cell surface and intracellular antigens were analyzed on a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson), collecting data from at least 20,000 bacteria or 5,000 cells. Bacteria that were positive or negative for C3 binding were sorted by using a FACSVantage SE (Becton Dickinson) and plated onto Columbia blood agar plates for overnight culture, followed by culture in THY broth from which bacterial stocks were made and stored at −70°C.

Statistical Analysis.

The results of C3 deposition experiments were analyzed with two-tailed t tests. Differences between mouse strains were compared with the log rank method for the survival curves, the Mann–Whitney U test for cfu recovery at different time points after i.v. or i.p. challenge, and the Kruskal–Wallis tests for cfu recovery at different time points after i.n. inoculation. Differences in macrophage and lymphocyte cell surface markers were analyzed with Mann–Whitney U tests.

Results

C3 Binding to S. pneumoniae in the Absence of Specific IgG Depended on Both the Classical and Alternative Complement Pathways.

The rate and intensity of C3 deposition on S. pneumoniae in mouse serum containing no specific anti-S. pneumoniae IgG was measured by using an FITC-labeled anti-mouse C3 antibody and flow cytometry. Complement C3 was deposited on a high proportion of bacteria for the four S. pneumoniae capsular serotypes (2, 3, 4, and 6B) investigated, with the highest levels on the capsular serotype 2 strain D39. This strain was chosen for more detailed investigation. There was a striking bimodal distribution of C3 binding to S. pneumoniae, with approximately half the bacteria with intense deposition of C3 on their surface and half with low or negligible C3 deposition (Fig. 1A). To investigate whether this bimodal pattern was caused by the kinetics of C3 deposition or by a specific subset of S. pneumoniae that binds C3 avidly, the two populations of S. pneumoniae that were positive or negative for C3 binding were separated by sorting with a flow cytometer and used in further C3-binding experiments. If C3 was deposited only on a subset of S. pneumoniae cells, then bacteria which were previously C3-positive would be expected to have a higher proportion of C3 binding than those that were previously C3-negative. However, the proportions of bacteria binding C3 were similar in both populations [53 ± 5.9% (± SD) vs. 63 ± 7.6%, respectively]. Furthermore, C3 deposition depended on the quantity of bacteria incubated in a fixed volume of serum (89% for 105 bacteria, 43% for 3 × 106 bacteria, and 2% for 1.5 × 107 bacteria per μl of serum). Hence, C3 binding to bacteria of a given S. pneumoniae serotype was affected mainly by the availability of complement rather than by differences in bacterial phenotype.

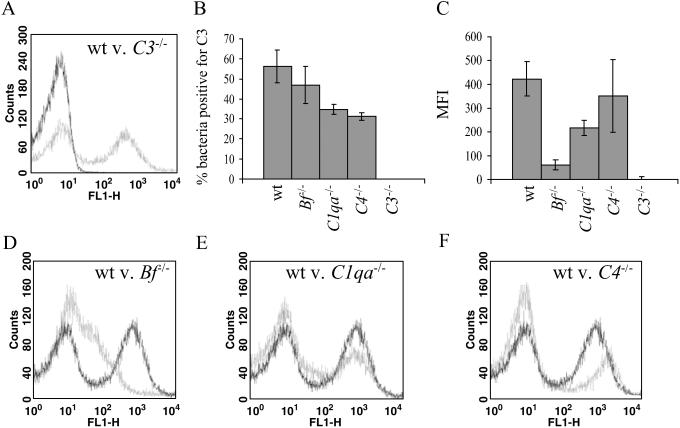

Fig 1.

C3 deposition on the surface of S. pneumoniae strain D39. (A) Flow cytometry histogram for bacteria incubated with sera from wild-type (wt, gray line) or C3−/− mice (black line). (B) The proportion of bacteria positive for C3 after incubation for 20 min in sera from wild-type and complement-deficient mice. P values compared with wild-type sera are: for Bf−/−, P = 0.08; and for C1qa−/− or C4−/−, P < 0.002. (C) Intensity of C3 deposition on bacteria after incubation in sera from wild-type and complement-deficient mice for 20 min. P values compared with wild-type sera are: for Bf−/−, P = 0.009; for C1qa−/−, P = 0.0004; and for C4−/−, P = 0.96. For B and C, the data for each strain represent the mean of results obtained from four to five mice from a single experiment and are representative of results obtained from at least two separate experiments using sera from different mice. (Bars = SD.) (D–F) Examples of histograms of flow cytometry data for bacteria incubated with sera from complement-deficient mice (gray line) compared with bacteria incubated in sera from wild-type mice (black line).

The relative importance of each complement pathway for complement activation by S. pneumoniae was investigated by comparing C3 deposition on S. pneumoniae incubated in sera from mice with engineered genetic complement deficiencies. The proportion of bacteria positive for C3 was significantly decreased when incubated in sera from immune naïve C1qa−/− and C4−/− mice, but not Bf−/− mice, compared with sera from wild-type mice (Fig. 1B), indicating that, in the absence of specific IgG, S. pneumoniae can activate the classical pathway. Comparison of C3 deposition on S. pneumoniae in sera from C1qa−/−.Bf−/− (in which only MBL pathway activation is possible) and wild-type mice demonstrated that only a very small proportion of C3 binding was MBL-dependent (wild-type 80 ± 8.2%, C1qa−/−.Bf−/− 3.0 ± 2.7%, P < 0.0001). The pattern of C3 deposition on bacteria in sera from C1qa−/− and C4−/− mice gave a similar bimodal pattern to that found on bacteria incubated with wild-type serum (Fig. 1 E and F). In contrast, there was a striking decrease in the intensity of C3 deposition on bacteria incubated in sera from Bf−/− mice [wild-type: 422 mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) per bacterium; Bf−/−: 61 MFI per bacterium, P < 0.01] (Fig. 1C), resulting in a left shift of the C3-positive population on the flow cytometry histogram (Fig. 1D). As the MBL pathway contributed little toward C3 deposition, the low-intensity C3 deposition on bacteria incubated in Bf−/− serum represents the pure effects of classical pathway-dependent C3 activation. These results confirmed that a major role for the alternative pathway is amplification of C3 deposition (25), whereas the proportion of bacteria bound with C3 is influenced mainly by the classical pathway.

C3 Binding to S. pneumoniae Was Partially Mediated by Natural IgM.

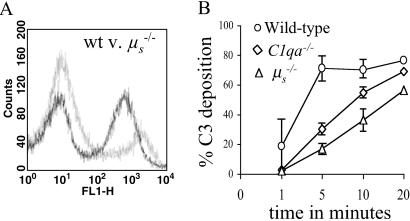

A possible mediator of classical pathway complement activation in the absence of specific IgG could be natural IgM (26). To investigate this possibility, we assessed C3 deposition on S. pneumoniae by using sera from μs−/− mice (21). After incubation in μs−/− sera, the proportion of S. pneumoniae bound by C3 was reduced compared with incubation in sera from immune naive wild-type mice (wild-type = 56 ± 8.2%; μs−/− = 23 ± 5.1%; P < 0.001). The intensity of C3 deposition on S. pneumoniae in μs−/− serum was unaffected and had a similar pattern to that seen with C1qa−/− and C4−/− serum (wild-type = 422 ± 72 MFI per bacterium; μs−/− = 385 ± 85 MFI per bacterium; P = 0.96; Fig. 2A). The time course of C3 deposition on S. pneumoniae in μs−/− sera mirrored that of C1qa−/− sera, with the proportion of bacteria bound by C3 only approaching the levels found with wild-type sera after 20 min (Fig. 2B). Direct evidence of IgM binding to S. pneumoniae in sera from immune naïve mice was obtained by using a phycoerythrin-labeled anti-mouse IgM antibody. Incubation in wild-type sera consistently resulted in a low level of IgM binding to S. pneumoniae compared with incubation in μs−/− sera (wild-type = 3.4 ± 1.2%; μs−/− = 0.66 ± 0.18%; P = 0.003). The proportion of bacteria bound by IgM was substantially increased in an isogenic unencapsulated strain of D39 (41 ± 11%). These results indicate that natural IgM binds directly to S. pneumoniae and mediates classical pathway complement activation in the absence of specific IgG. In addition, prevention of natural IgM binding to S. pneumoniae surface antigens could be one mechanism by which the S. pneumoniae capsule contributes to virulence.

Fig 2.

Role of IgM in C3 deposition on S. pneumoniae. (A) An example of a flow cytometry histogram of C3 deposition on bacteria incubated with sera from wild-type (black line) and μs−/− (gray line) mice. (B) Time course of C3 deposition on D39 in sera from wild-type, C1qa−/−, and μs−/− mice. (Bars = SD.) Data are from a single experiment using pooled sera from three mice and are representative of two separate experiments using sera from different mice.

Survival of Mice with Different Complement Deficiencies After Infection with S. pneumoniae.

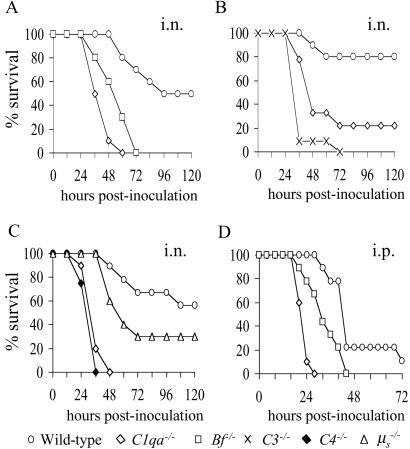

The biological role of the three complement pathways and natural IgM during innate immunity was investigated in mouse models of S. pneumoniae pneumonia (i.n. inoculation) and septicemia (i.p. inoculation). As C57BL/6 mice are only partially susceptible to S. pneumoniae i.n., they provide a sensitive model for identifying mouse strains with increased susceptibility (27). Groups of 8–10 immune naïve wild-type and complement-deficient mice were monitored after i.n. or i.p. inoculation with S. pneumoniae. After i.n. inoculation, C1qa−/− and Bf−/− mice developed a more severe and rapidly progressing disease than wild-type mice (Fig. 3A), demonstrating that both the classical and alternative pathways contribute to innate immunity to S. pneumoniae. When given a lower dose inoculum i.n., C1qa−/− mice were less susceptible than C3−/− mice (median survival = 48 and 36 h, respectively; P = 0.05), thus providing additional evidence that both the classical and alternative pathways contribute to innate immunity to S. pneumoniae (Fig. 3B). C4−/− mice, which have lost both the classical and MBL pathways, had the same degree of susceptibility as C1qa−/− mice after i.n. inoculation (median survival = 36 h for both strains), indicating the minimal contribution of the MBL pathway in this model (Fig. 3C). After i.n. inoculation, μs−/− mice had an increased rate of disease progression and mortality compared with wild-type mice, but were less susceptible than C1qa−/− or C4−/− mice (median survival = 60 h vs. 36 h, respectively; P = 0.001; Fig. 3C), showing that, although natural IgM assists innate immunity to S. pneumoniae in mice, it is not as important as the presence of an intact classical pathway. C1qa−/− mice were also more susceptible than wild-type mice after i.p. inoculation (Fig. 3D), and had more rapidly progressing disease than Bf−/− mice after both i.n. (median survival = 24 and 36 h, respectively; P = 0.05) and i.p. (median survival = 24 and 36 h, respectively; P = 0.03) inoculation (Fig. 3 A and D). These results show that the classical pathway is the dominant complement pathway for innate immunity to both systemic and mucosal S. pneumoniae infections, and that the alternative pathway plays a contributory role.

Fig 3.

Survival curves for complement-deficient mice inoculated with S. pneumoniae. (A) i.n. inoculation with 1 × 106 cfu. For the differences between wild-type and C1qa−/− mice, P = 0.001; between wild-type and Bf−/− mice, P = 0.001; and between C1qa−/− and Bf−/− mice, P = 0.05. (B) i.n. inoculation with 4 × 105 cfu. For the differences between wild-type and C1qa−/− mice, P = 0.003; between wild-type and C3−/− mice, P = 0.001; and between C1qa−/− and C3−/− deficient mice, P = 0.05. (C) i.n. inoculation with 2 × 106 cfu. For the differences between wild-type or μs−/− and C1qa−/− or C4−/− mice, P = 0.001; between C1qa−/− and C4−/− mice, P = 0.96; and between μs−/− and wild-type mice, P = 0.01 (data pooled from two experiments). (D) i.p. inoculation with 2 × 103 cfu. For the differences between wild-type and C1qa−/−mice, P = 0.001; between wild-type and Bf−/− mice, P = 0.09; and between C1qa−/− and Bf−/− mice, P = 0.03. Duplicate experiments were performed for all i.n. comparisons and produced similar results.

Increased Systemic Replication of S. pneumoniae in C1qa−/− and μs−/− Mice.

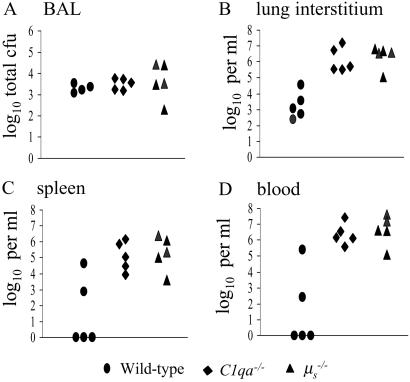

To characterize the role of C1q and natural IgM during innate immunity in more detail, groups of wild-type, C1qa−/−, and μs−/− mice were killed 6 and 24 h after i.n. inoculation with 2 × 106 cfu S. pneumoniae, and the number of bacteria present in infected organs (blood, spleen, BAL, and lung) was assessed. There were no significant differences in S. pneumoniae cfu recovered from the BAL and lungs of wild-type, C1qa−/−, and μs−/− mice 6 h after inoculation (data not shown). Bacteria were only recovered from the blood or spleen in a small number of mice at this time point. In contrast, at 24 h, although the S. pneumoniae cfu recovered from BAL were similar for all three groups (Fig. 4A), there were 2–3 logs fewer cfu in the lungs of wild-type mice compared with C1qa−/− and μs−/− mice (Fig. 4B). In addition, all C1qa−/− and μs−/− mice had large numbers of bacteria present in the spleen and blood (up to 106 and 107 cfu/ml, respectively), whereas bacteria were recovered from these sites in only a minority of wild-type mice and in smaller numbers (105 per ml maximum; Fig. 4 C and D). Similar results were obtained 16 h after i.p. inoculation with 1.5 × 103 cfu of S. pneumoniae. Both C1qa−/−- and μs−/−-deficient mice had greater bacterial cfu in the blood than wild-type mice [median log10 cfu per ml: wild-type = 5.8 (5.4–6.6, interquartile range); C1qa−/− mice = 8.7 (8.6–9.0); μs−/− mice = 8.2 (7.6–8.2; P = 0.01)] and spleen [median log10 cfu per ml spleen homogenate: wild-type = 6.3 (5.9–6.4); C1qa−/− mice = 8.0 (7.6–8.1); μs−/− mice = 7.4 (7.3–7.5; P = 0.01)]. The decreased cfu recovered from the spleen and blood of μs−/− mice compared with C1qa−/− mice were statistically significant (P = 0.02 for both spleen and blood). These data suggest that C1qa−/− and μs−/− mice were unable to control replication of bacteria within the lung interstitium and systemic circulation, possibly because of a reduced ability to remove bacteria from the blood. To test this possibility, the clearance of bacteria by wild-type and C1qa−/− mice given a bolus i.v. inoculation of 1.5 × 106 cfu of S. pneumoniae was investigated. After 2 h and 4 h, C1qa−/− mice had approximately one log greater cfu in the blood compared with wild-type mice (P = 0.02; Fig. 5). Hence C1qa−/− mice were unable to remove S. pneumoniae from the systemic circulation, allowing septicemia to progress rapidly.

Fig 4.

Comparison of the recovery of S. pneumoniae cfu (expressed as log10) from the target organs of wild-type, C1qa−/−, and μs−/− mice 24 h after inoculation i.n. with 1 × 106 cfu. Each data point represents results from a separate mouse. (A) Total cfu in BAL fluid. (B) Bacterial cfu per ml of lung homogenate. (C) Bacterial cfu per ml of spleen homogenate. (D) Bacterial cfu per ml of blood. For the differences in cfu recovered from lungs, spleen, and blood at 24 h among wild-type, C1qa−/−, and μs−/− mice, P < 0.02. Similar results were obtained in duplicate experiments.

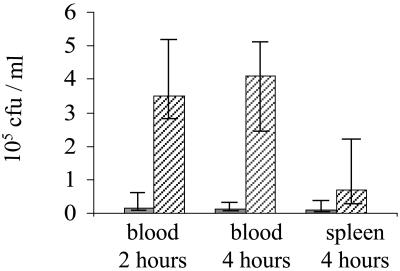

Fig 5.

Clearance of S. pneumoniae from the blood and spleens of wild-type (gray bars) and C1qa−/− (hatched bars) mice inoculated i.v. with 1.5 × 106 cfu. Data are presented as median cfu per ml, with error bars representing the interquartile range. For the differences between wild-type and C1qa−/− mice for blood at 2 and 4 h, P = 0.02, and for the spleen at 4 h, P = 0.15. Similar results were obtained in duplicate experiments.

Reduced Innate and Primary Adaptive Immune Responses to S. pneumoniae Infection in C1qa−/− Mice.

The above results demonstrated that C1q is required for complement activation by S. pneumoniae and clearance of this organism from the systemic circulation even in the absence of specific anti-S. pneumoniae IgG. To evaluate whether C1q deficiency had more widespread effects on the host immune response, host cells were isolated from BAL, lungs, and mesenteric lymph nodes of groups of four or five wild-type and C1qa−/− mice infected with S. pneumoniae and analyzed by using labeled macrophage and lymphocyte antibody markers and flow cytometry.

For both 6 h and 24 h after i.n. inoculation of S. pneumoniae, the percentages of activated macrophages (defined as macrophages positive for MHC class II alloantigens) in BAL were significantly reduced in C1qa−/− mice compared with wild-type mice (Table 1). Similar results were obtained by using CD80 as a marker of macrophage activation (data not shown) and in duplicate experiments. In addition, activated macrophages in the lungs of C1qa−/− mice at 24 h were reduced compared with wild-type mice (Table 1). No significant differences were identified between wild-type and C1qa−/− mice in the proportions of CD4 and CD8 lymphocytes and lymphocyte intracellular IL-4 and IFN-γ levels in the lungs of mice inoculated i.n. or in the mesenteric lymph nodes of mice inoculated i.p. (data not shown). However, the proportions of activated CD4 lymphocytes (negative for CD45RB) were reduced in C1qa−/− mice compared with wild-type mice in the lungs 24 h after i.n. inoculation with S. pneumoniae and in the mesenteric lymph nodes 24 h after i.p. inoculation (Table 1). The proportions of activated CD8 cells in lungs and mesenteric lymph nodes 24 h after i.n. and i.p. inoculation with S. pneumoniae were similar between the two mouse strains (data not shown). These results demonstrate that, by decreasing C3 activation via the classical pathway even in the absence of specific IgG, C1q deficiency affects components of both the innate and primary adaptive immune response and causes widespread defects in the immune response to S. pneumoniae.

Table 1.

Proportion of activated macrophages (positive for MHC type II alloantigens) and activated CD4 lymphocytes (CD45Rb-negative) after infection with S. pneumoniae in wild-type and C1qa−/− mice

| Source of cells

|

Time point, h

|

Median % activated macrophages (interquartile range) | Median % activated CD4 (interquartile range) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type | C1qa−/− | P value | Wild type | C1qa−/− | P value | ||

| BAL | 6 | 49 (38–64) | 31 (27–35) | 0.02 | nd | nd | – |

| BAL | 24 | 87 (78–93) | 65 (62–69) | 0.04 | 90 (89–90) | 87 (86–88) | 0.11 |

| Lung | 24 | 96 (95–97) | 90 (88–92) | 0.05 | 98 (98–98) | 94 (93–96) | 0.04 |

| Mesenteric lymph nodes | 24 | nd | nd | – | 88 (86–91) | 78 (77–80) | 0.02 |

nd, not done.

After i.n. inoculation with 1 × 106 cfu.

After i.p. inoculation with 3 × 106 cfu.

Discussion

Although there is increasing evidence that the classical pathway has a role in innate immunity to bacterial pathogens (7, 16, 28, 29), previous studies have not been able to establish unequivocally the importance of the classical pathway and compare its role to the other complement pathways. By using mice with specific genetic defects, we have characterized the roles of the classical, alternative, and MBL complement pathways for innate immunity to S. pneumoniae. The results of the C3-binding assays demonstrate that in the absence of specific anti-S. pneumoniae IgG, the proportion of bacteria opsonized by complement depends mainly on the classical pathway, and that the major role of the alternative pathway, as shown by Xu et al. (25), is amplification of complement activation leading to denser C3 deposition on the bacteria. The low level of C3 binding to S. pneumoniae in C1qa−/−.Bf−/− serum suggests that the MBL pathway has only a minor role in complement activation by S. pneumoniae.

The existing data on the importance of the classical and alternative pathways for immunity to S. pneumoniae are conflicting, with some results suggesting an important role for the alternative pathway (8, 30), and other data emphasizing C4-dependent mechanisms (7). Here, we have shown that both C1qa−/− and Bf−/− mice had an increased susceptibility to S. pneumoniae after i.n. inoculation, the natural route of infection, thus demonstrating that both the classical and alternative complement pathways are required for innate immunity. Interestingly, C1qa−/−-deficient mice were more susceptible than Bf−/− mice after both i.n. and i.p. inoculation. This surprising result shows that not only is the classical pathway important for the innate immune response, but that it is the dominant complement pathway for innate immunity to S. pneumoniae, at least in mice. The similar susceptibility of C4−/− and C1qa−/− mice to infection with S. pneumoniae indicates that loss of the MBL pathway does not significantly affect innate immunity to S. pneumoniae, a result which is compatible with the absence of C3 binding in C1qa−/−.Bf−/− sera, reports that MBL binds poorly to S. pneumoniae, and that genetic polymorphisms affecting MBL levels are only weakly associated with S. pneumoniae infections (31–33).

We have characterized the nature of C1q-dependent innate immunity in more detail. The clearance of S. pneumoniae from the systemic circulation, which is known to depend on opsonization by complement components and phagocytosis of bacteria by the reticuloendothelial system (5, 34), was reduced in C1qa−/− mice. In addition, when C1qa−/− mice were challenged by S. pneumoniae, the proportions of activated macrophages and lymphocytes at the site of infection were reduced compared with wild-type mice, probably as a consequence of reduced complement activation decreasing effective phagocytosis of bacteria by macrophages with secondary effects on CD4 lymphocytes. Hence, loss of C1q affects not only the innate immune response but also the primary adaptive immune response, leading to an inability to control S. pneumoniae replication in the systemic circulation, severe septicemia, and a striking increase in the rate of disease development and (after i.n. inoculation) mortality.

One mechanism by which bacteria could activate the classical pathway during innate immunity is through natural IgM. Natural IgM antibodies to the C polysaccharide (teichoic acid) of the S. pneumoniae cell wall have been well described; they are required for immunity to S. pneumoniae (7, 26). By using μs−/− mice, we have shown that complement activation in the absence of adaptive immunity requires natural IgM. The pattern of complement activation by S. pneumoniae in μs−/− mice was similar to that seen with deficiencies of the classical complement pathway, and both μs−/−- and C1qa−/−-deficient mice challenged with S. pneumoniae developed severe septicemia, strongly suggesting that natural IgM acts through the classical complement pathway. However, in μs−/− mice, there was only a moderate increase in mortality after i.n. inoculation with S. pneumoniae, which contrasts with the rapidly fatal disease that developed in C1qa−/− mice. In addition, there were lower levels of cfu in the blood and spleen after i.p. inoculation in μs−/− mice compared with C1qa−/− mice. Hence, the in vivo role of the classical pathway during innate immunity only partially depends on natural IgM. This finding may reflect additional classical pathway activation either by direct binding of C1q to bacteria (10) or by the interaction of components of the acute-phase response with S. pneumoniae, which could assist the innate immune response of μs−/− but not C1qa−/− or C4−/− mice. Because the sera used for the C3-binding assays were obtained from healthy uninfected mice, classical pathway complement activation caused by an acute-phase response component would not be detected. Which of the acute-phase response component(s) might be involved in vivo is unclear, as serum amyloid P, the major acute-phase protein in mice, decreases resistance to infection when bound to bacterial pathogens (35). Human CRP is known to bind to S. pneumoniae and activate the classical pathway, and augmentation of mice with human CRP, either by expression from a transgene or by injection, protects against S. pneumoniae infection, acting through complement (7, 36, 37). Therefore, CRP is a second mechanism by which the classical pathway could provide innate immunity to S. pneumoniae in humans, but is unlikely to be important in our infection model, as CRP is only expressed at low levels in mice.

In summary, we have demonstrated that the classical pathway of complement is the critical complement pathway required for innate immunity to S. pneumoniae infection in mice, the loss of which results in widespread defects in the immune response to this pathogen, severe septicemia, and the rapid development of fatal disease.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Wellcome Trust Advanced Fellowship for Medical and Dental Graduates 056586 (to J.S.B.) and Wellcome Trust Project Grant 066335.

Abbreviations

MBL, mannose-binding lectin

PBS, physiologically buffered saline

i.n., intranasal

BAL, bronchoalveolar lavage

References

- 1.Lim W. S., Macfarlane, J. T., Boswell, T. C., Harrison, T. G., Rose, D., Leinonen, M. & Saikku, P. (2001) Thorax 56, 296-301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Walport M. J. (2001) N. Engl. J. Med. 344, 1058-1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alper C. A., Abramson, N., Johnston, R. B., Jr., Jandl, J. H. & Rosen, F. S. (1970) N. Engl. J. Med. 282, 350-354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gross G. N., Rehm, S. R. & Pierce, A. K. (1978) J. Clin. Invest. 62, 373-378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Winkelstein J. A. (1981) Rev. Infect. Dis. 3, 289-298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sampson H. A., Walchner, A. M. & Baker, P. J. (1982) J. Clin. Immunol. 2, 39-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mold C., Rodic-Polic, B. & Du Clos, T. W. (2002) J. Immunol. 168, 6375-6381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hosea S. W., Brown, E. J. & Frank, M. M. (1980) J. Infect. Dis. 142, 903-909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clas F. & Loos, M. (1981) Infect. Immun. 31, 1138-1144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Prellner K. (1981) Acta Pathol. Microbiol. Scand. 89, 359-364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alberti S., Marques, G., Camprubi, S., Merino, S., Tomas, J. M., Vivanco, F. & Benedi, V. J. (1993) Infect. Immun. 61, 852-860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mintz C. S., Arnold, P. I., Johnson, W. & Schultz, D. R. (1995) Infect. Immun. 63, 4939-4943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Butko P., Nicholson-Weller, A. & Wessels, M. R. (1999) J. Immunol. 163, 2761-2768. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boes M., Prodeus, A. P., Schmidt, T., Carroll, M. C. & Chen, J. (1998) J. Exp. Med. 188, 2381-2386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yother J., Volanakis, J. E. & Briles, D. E. (1982) J. Immunol. 128, 2374-2376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wessels M. R., Butko, P., Ma, M., Warren, H. B., Lage, A. L. & Carroll, M. C. (1995) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92, 11490-11494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morona J. K., Paton, J. C., Miller, D. C. & Morona, R. (2000) Mol. Microbiol. 35, 1431-1442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Botto M., Dell'Agnola, C., Bygrave, A. E., Thompson, E. M., Cook, H. T., Petry, F., Loos, M., Pandolfi, P. P. & Walport, M. J. (1998) Nat. Genet. 19, 56-59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matsumoto M., Fukuda, W., Circolo, A., Goellner, J., Strauss-Schoenberger, J., Wang, X., Fujita, S., Hidvegi, T., Chaplin, D. D. & Colten, H. R. (1997) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94, 8720-8725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fischer M. B., Ma, M., Goerg, S., Zhou, X., Xia, J., Finco, O., Han, S., Kelsoe, G., Howard, R. G., Rothstein, T. L., et al. (1996) J. Immunol. 157, 549-556. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ehrenstein M. R., O'Keefe, T. L., Davies, S. L. & Neuberger, M. S. (1998) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95, 10089-10093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brown J. S., Gilliland, S. M. & Holden, D. W. (2001) Mol. Microbiol. 40, 572-585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hussell T., Spender, L. C., Georgiou, A., O'Garra, A. & Openshaw, P. J. (1996) J. Gen. Virol. 77, 2447-2455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hussell T., Khan, U. & Openshaw, P. (1997) J. Immunol. 159, 328-334. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xu Y., Ma, M., Ippolito, G. C., Schroeder, H. W., Jr., Carroll, M. C. & Volanakis, J. E. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 14577-14582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Briles D. E., Nahm, M., Schroer, K., Davie, J., Baker, P., Kearney, J. & Barletta, R. (1981) J. Exp. Med. 153, 694-705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gingles N. A., Alexander, J. E., Kadioglu, A., Andrew, P. W., Kerr, A., Mitchell, T. J., Hopes, E., Denny, P., Brown, S., Jones, H. B., et al. (2001) Infect. Immun. 69, 426-434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Celik I., Stover, C., Botto, M., Thiel, S., Tzima, S., Kunkel, D., Walport, M., Lorenz, W. & Schwaeble, W. (2001) Infect. Immun. 69, 7304-7309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Warren J., Mastroeni, P., Dougan, G., Noursadeghi, M., Cohen, J., Walport, M. J. & Botto, M. (2002) Infect. Immun. 70, 551-557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tu A. H., Fulgham, R. L., McCrory, M. A., Briles, D. E. & Szalai, A. J. (1999) Infect. Immun. 67, 4720-4724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Neth O., Jack, D. L., Dodds, A. W., Holzel, H., Klein, N. J. & Turner, M. W. (2000) Infect. Immun. 68, 688-693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kronborg G., Weis, N., Madsen, H. O., Pedersen, S. S., Wejse, C., Nielsen, H., Skinhoj, P. & Garred, P. (2002) J. Infect. Dis. 185, 1517-1520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Roy S., Knox, K., Segal, S., Griffiths, D., Moore, C. E., Welsh, K. I., Smarason, A., Day, N. P., McPheat, W. L., Crook, D. W. & Hill, A. V. (2002) Lancet 359, 1569-1573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brown E. J., Hosea, S. W. & Frank, M. M. (1981) J. Immunol. 126, 2230-2235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Noursadeghi M., Bickerstaff, M. C., Gallimore, J. R., Herbert, J., Cohen, J. & Pepys, M. B. (2000) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97, 14584-14589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Horowitz J., Volanakis, J. E. & Briles, D. E. (1987) J. Immunol. 138, 2598-2603. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Szalai A. J., Briles, D. E. & Volanakis, J. E. (1996) Infect. Immun. 64, 4850-4853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]