Abstract

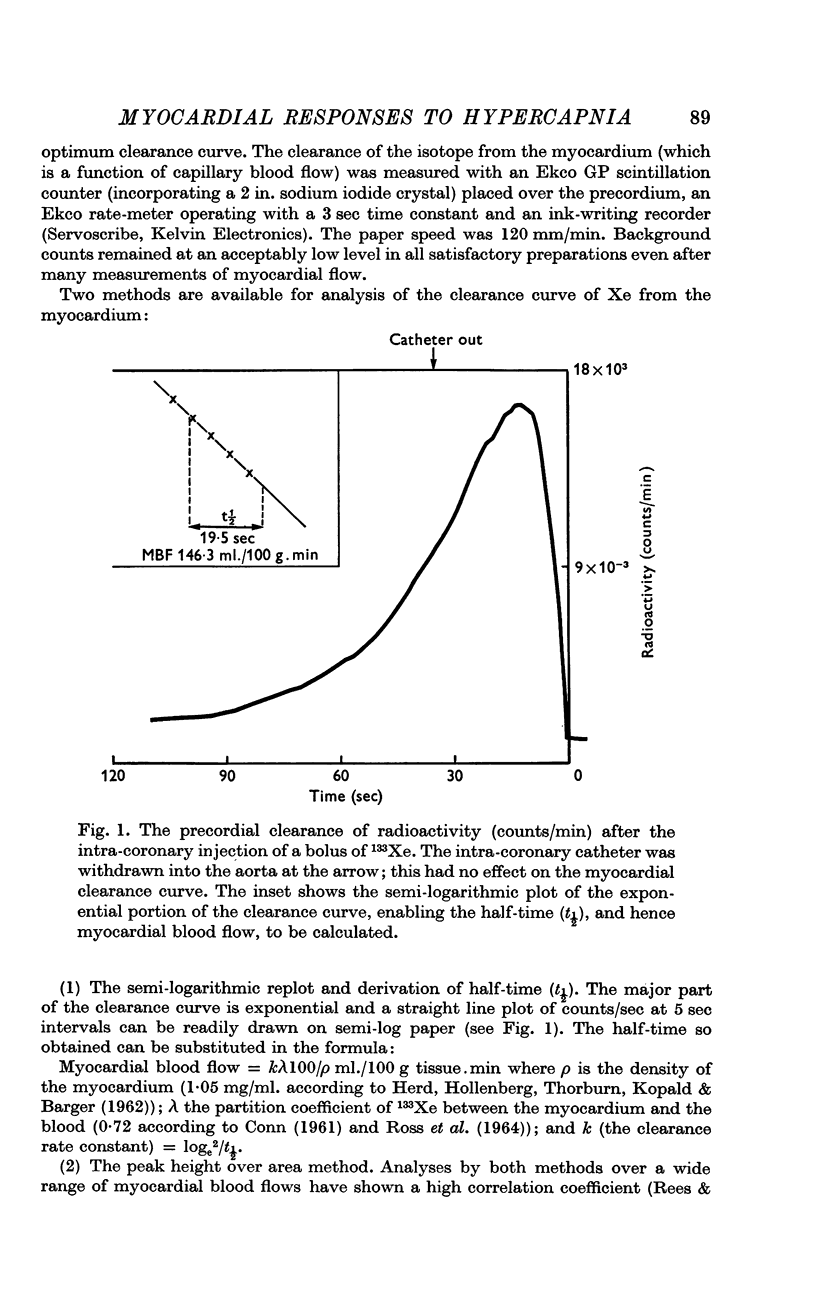

1. In closed-chest dogs anaesthetized with trichlorethylene, the inhalation of carbon dioxide sufficient to increase the arterial PCO2 from 40 to about 100 mm Hg, increased myocardial blood flow (measured using a 133Xe clearance technique) and right atrial pressure. There were no consistent changes in mean arterial blood pressure, heart rate or cardiac output.

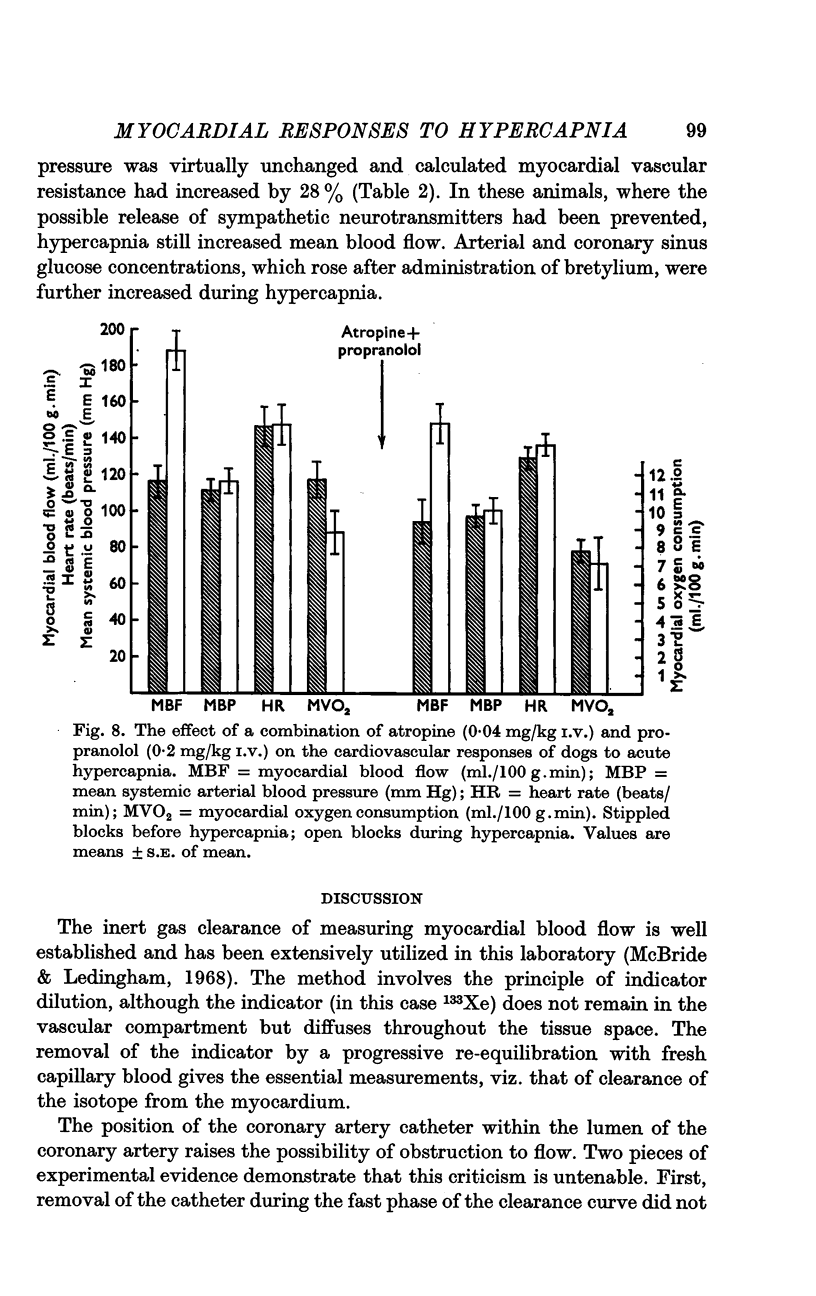

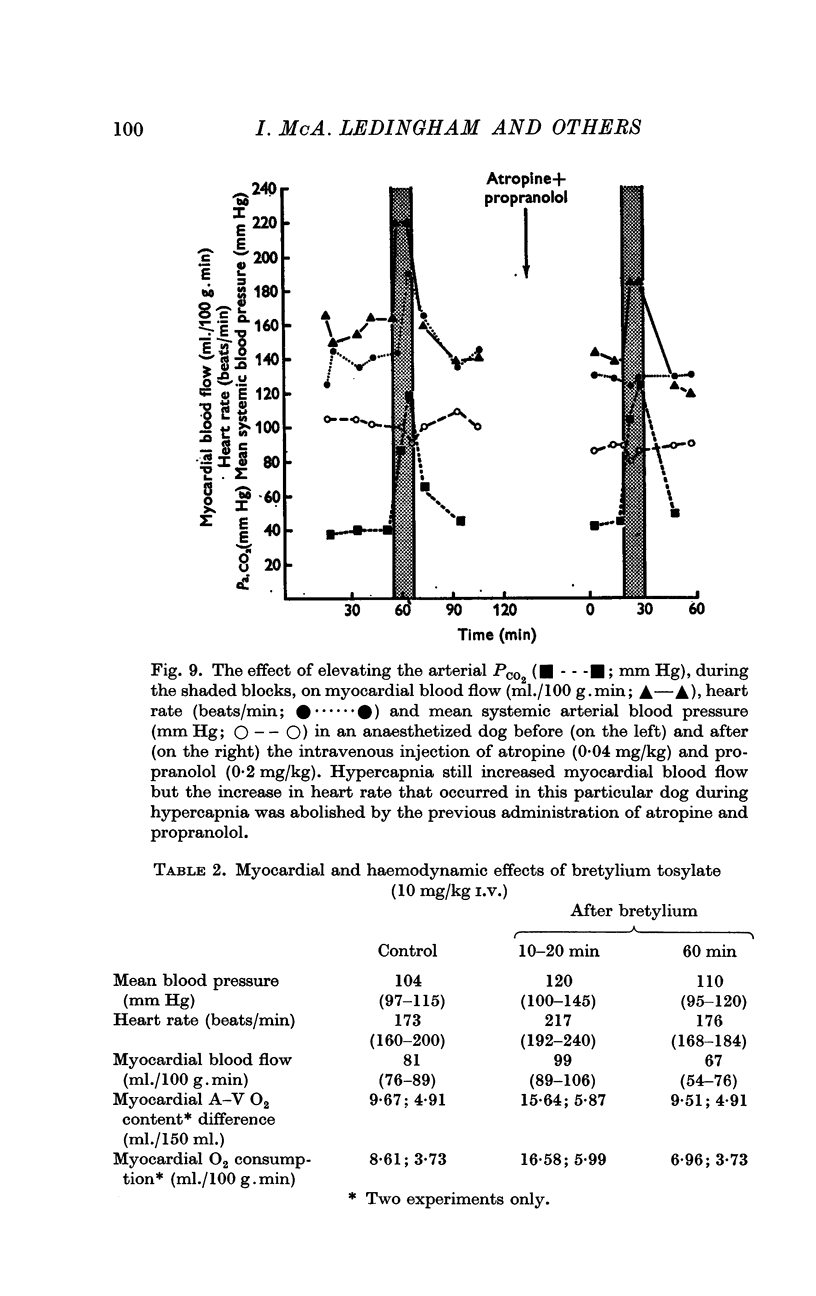

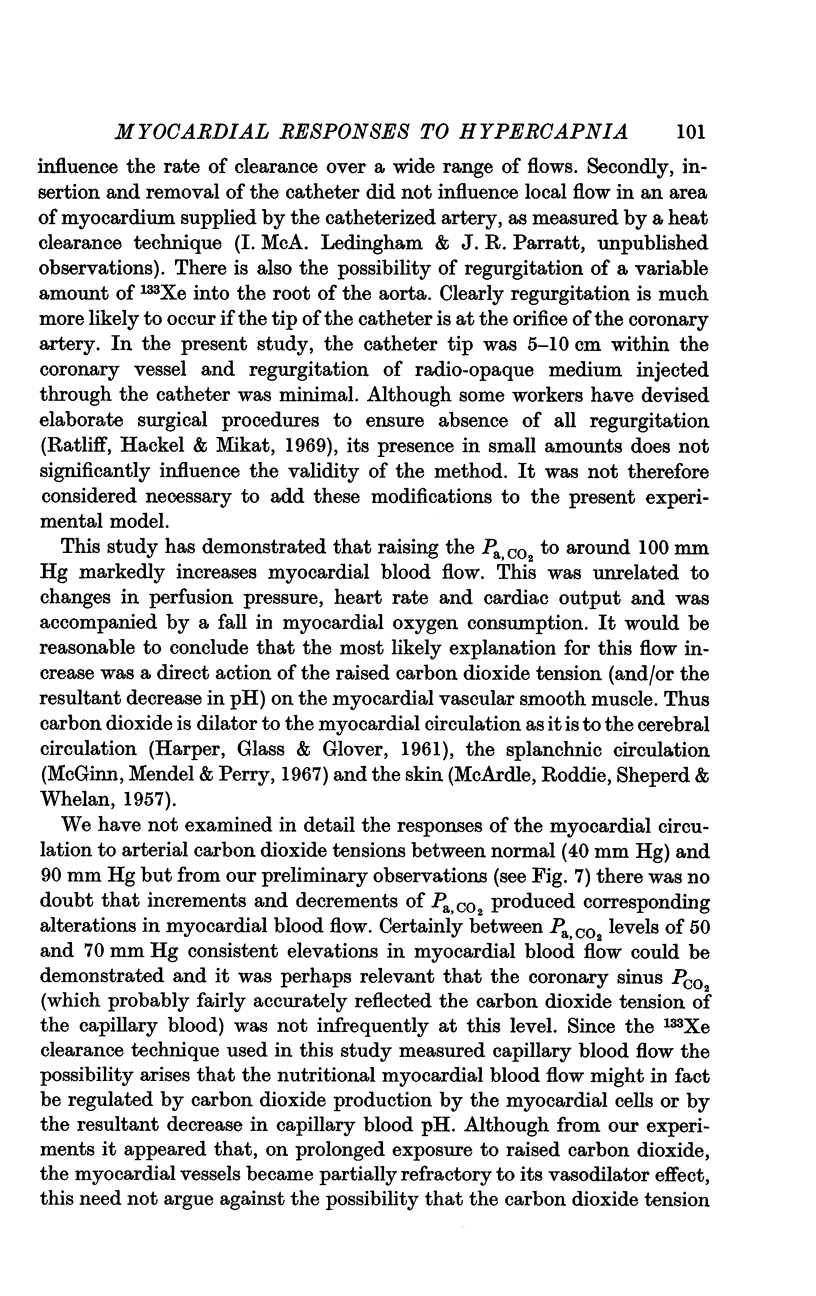

2. The effect of hypercapnia on myocardial blood flow was not influenced by the previous administration of atropine and propranolol or of bretylium. It can be concluded, therefore, that the elevated arterial PCO2 has a direct vasodilator effect on the myocardial microcirculation.

3. During hypercapnia the coronary sinus PO2 was increased and the coronary arteriovenous oxygen content difference, and calculated myocardial oxygen consumption, reduced. It is suggested that this latter effect may be the result of myocardial depression produced by the decrease in arterial blood pH.

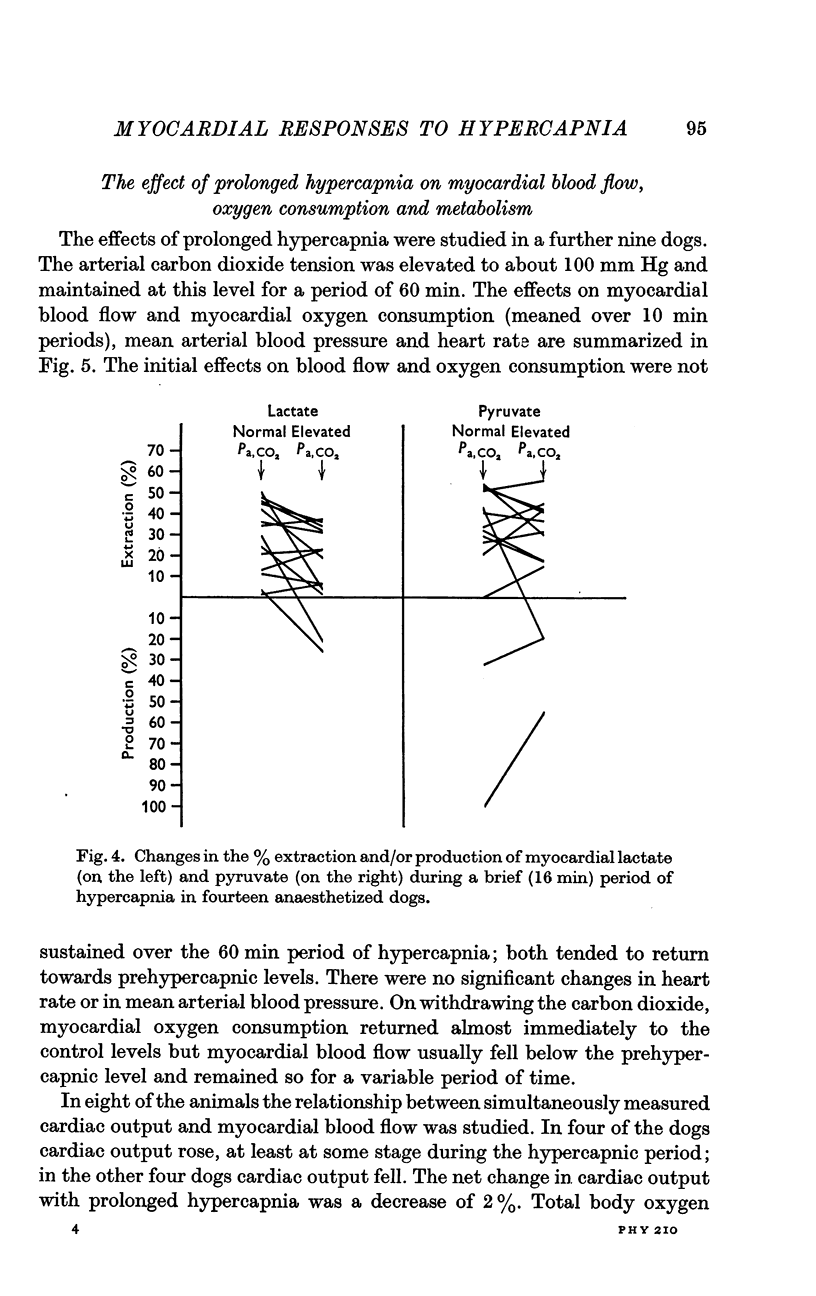

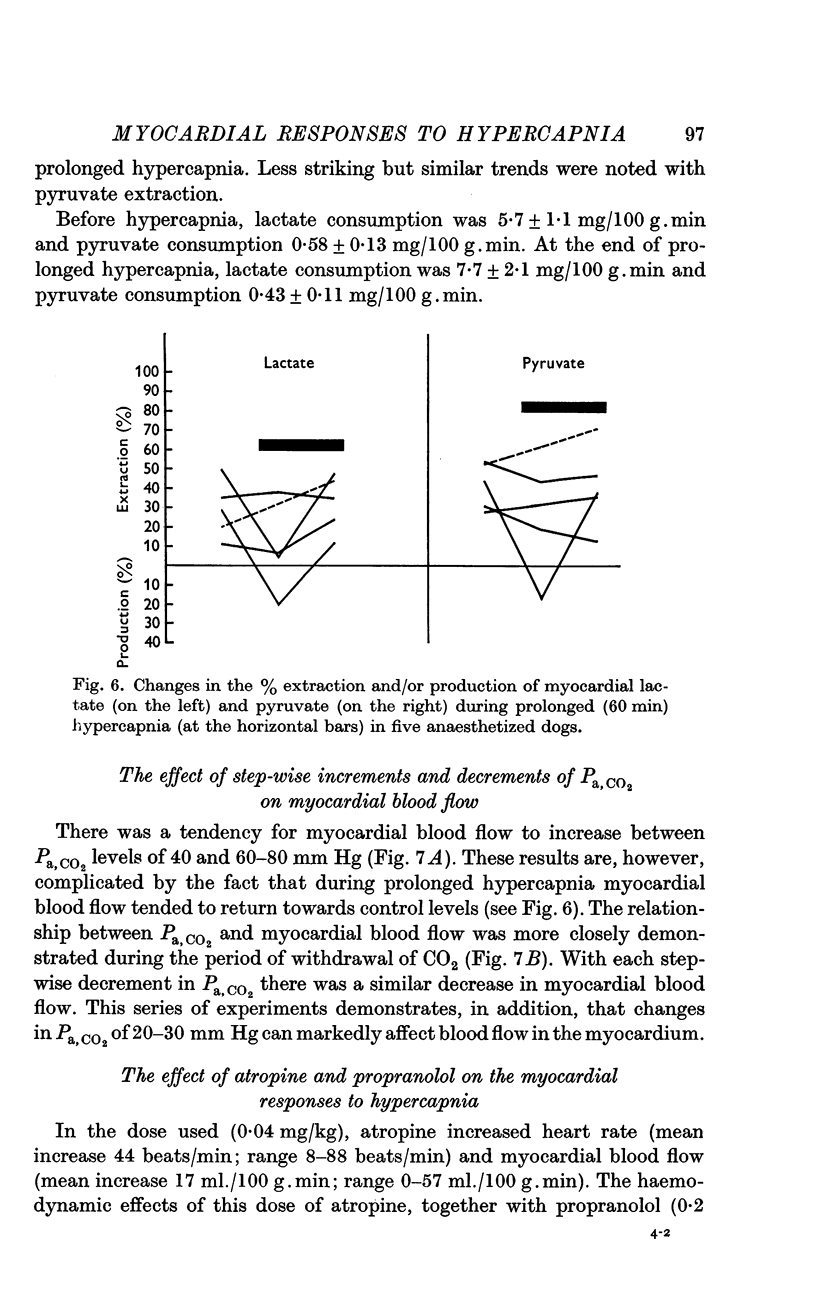

4. There was no evidence of myocardial glucose uptake either before or during hypercapnia. The myocardial extraction of lactate and pyruvate at rest varied between 0 and 55%. During acute hypercapnia the extraction of lactate usually fell.

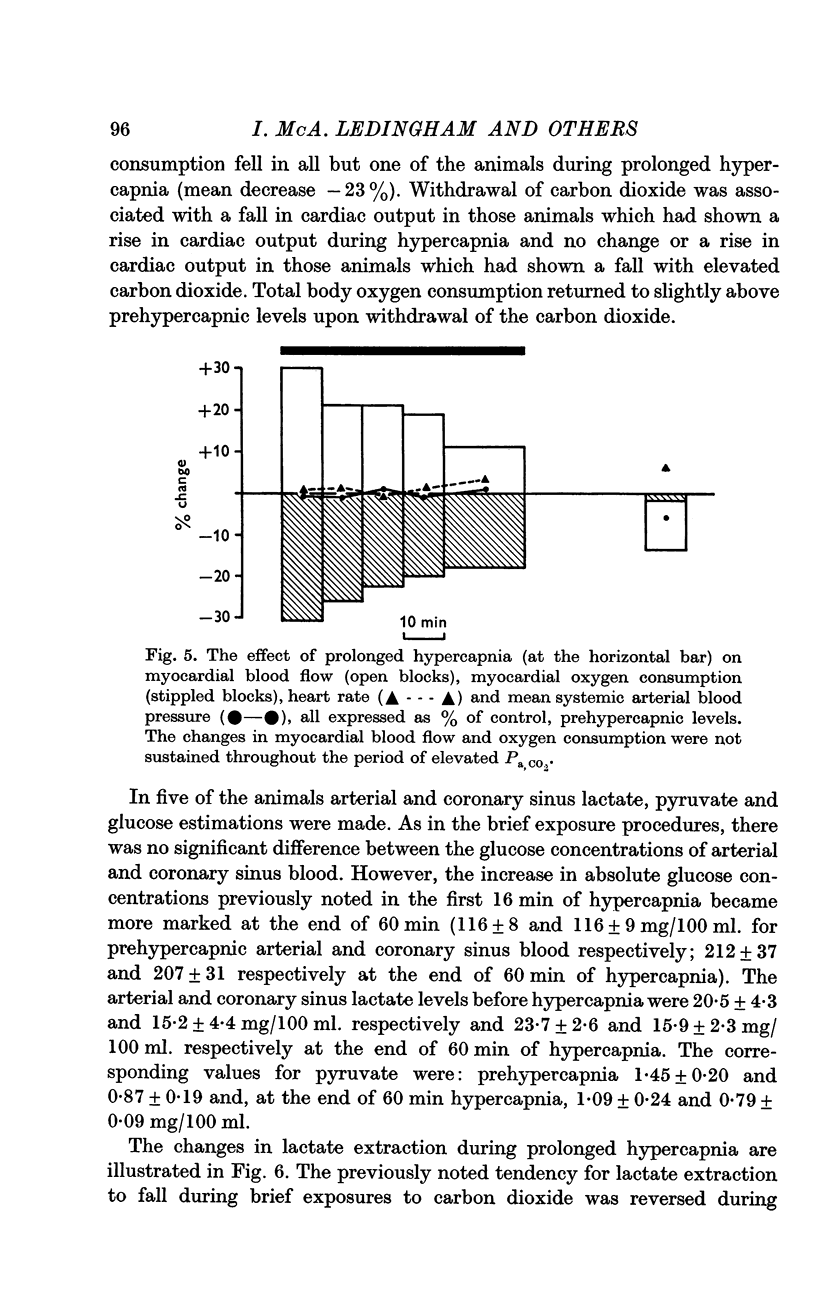

5. When the arterial PCO2 was maintained at 100 mm Hg for a period of 1 hr the effects on myocardial blood flow and on oxygen consumption were not sustained.

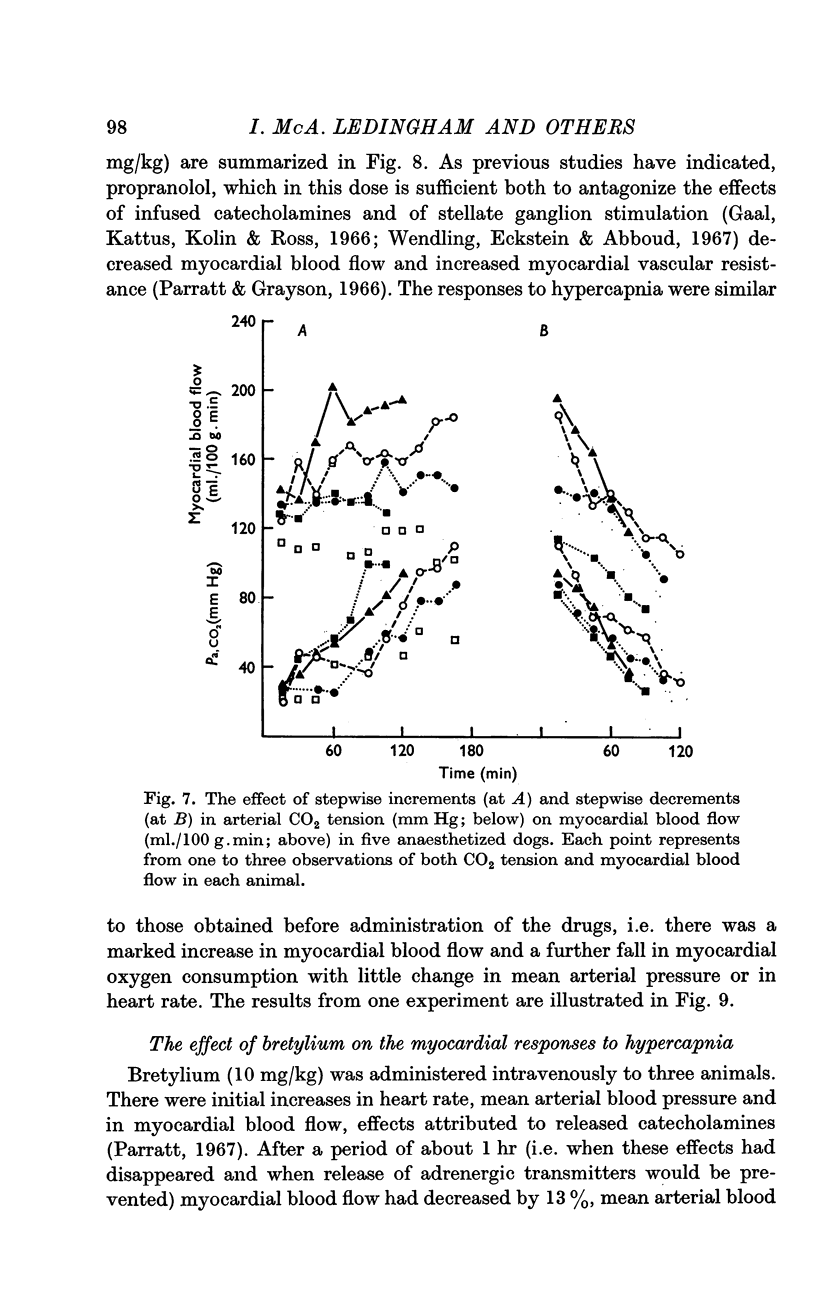

6. Stepwise increments and decrements in arterial PCO2 of 10-20 mm Hg produced corresponding increases and decreases in myocardial blood flow and demonstrated that changes in arterial PCO2 of 20-30 mm Hg can markedly affect blood flow in the myocardium.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- BING R. J. CARDIAC METABOLISM. Physiol Rev. 1965 Apr;45:171–213. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1965.45.2.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BONIFACE K. J., BROWN J. M. Effect of carbon dioxide excess on contractile force of heart, in situ. Am J Physiol. 1953 Mar;172(3):752–756. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1953.172.3.752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CONN H. L., Jr Equilibrium distribution of radioxenon in tissue: xenon-hemoglobin association curve. J Appl Physiol. 1961 Nov;16:1065–1070. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1961.16.6.1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CONN H. L., Jr Use of external counting technics in studies of the circulation. Circ Res. 1962 Mar;10:505–517. doi: 10.1161/01.res.10.3.505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eberlein H. J. Koronardurchblutung und Sauerstoffversorgung des Herzens unter verschiedenen CO2-Spannungen und Anästhetika. Arch Kreislaufforsch. 1966 Jun;50(1):18–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FEINBERG H., GEROLA A., KATZ L. N. Effect of changes in blood CO2 level on coronary flow and myocardial O2 consumption. Am J Physiol. 1960 Aug;199:349–354. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1960.199.2.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GOODYER A. V., ECKHARDT W. F., OSTBERG R. H., GOODKIND M. J. Effects of metabolic acidosis and alkalosis on coronary blood flow and myocardial metabolism in the intact dog. Am J Physiol. 1961 Mar;200:628–632. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1961.200.3.628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaal P. G., Kattus A. A., Kolin A., Ross G. Effects of adrenaline and noradrenaline on coronary blood flow before and after beta-adrenergic blockade. Br J Pharmacol Chemother. 1966 Mar;26(3):713–722. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1966.tb01851.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HACKEL D. B. Effect of insulin on cardiac metabolism of intact normal dogs. Am J Physiol. 1960 Dec;199:1135–1138. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1960.199.6.1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HARPER A. M., GLASS H. I., GLOVER M. M. Measurement of blood flow in the cerebral cortex of dogs, by the clearance of krypton-85. Scott Med J. 1961 Jan;6:12–17. doi: 10.1177/003693306100600103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HERD J. A., HOLLENBERG M., THORBURN G. D., KOPALD H. H., BARGER A. C. Myocardial blood flow determined with krypton 85 in unanesthetized dogs. Am J Physiol. 1962 Jul;203:122–124. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1962.203.1.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KITTLE C. F., AOKI H., BROWN E. B., Jr THE ROLE OF PH AND CO2 IN THE DISTRIBUTION OF BLOOD FLOW. Surgery. 1965 Jan;57:139–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraupp O., Grossmann W., Stühlinger W., Raberger G. Die Wirkung von Hexobendin auf die arterielle und coronarvenöse CO2-Spannung und Wasserstoffionenkonzentration am Hund. Beitrag zur Theorie des Wirkungsmechanismus von Coronardilatatoren. Arzneimittelforschung. 1968 Aug;18(8):1067–1073. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LAURENT D., BOLENE-WILLIAMS C., WILLIAMS F. L., KATZ L. N. Effects of heart rate on coronary flow and cardiac oxygen consumption. Am J Physiol. 1956 May;185(2):355–364. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1956.185.2.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledingham I. M., McBride T. I., Parratt J. R., Vance J. P. The effect of hypercapnia on myocardial blood flow and oxygen consumption. J Physiol. 1969 Jan;200(1):47P–48P. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lochner W., Hirche H., Koike S. Die Wirkung erhöhter Kohlensäuredrucke auf die Koronardurchblutung. Arztl Forsch. 1967 Nov 10;21(11):408–413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MANLEY E. S., Jr, NASH C. B., WOODBURG R. A. CARDIOVASCULAR RESPONSES TO SEVERE HYPERCAPNIA OF SHORT DURATION. Am J Physiol. 1964 Sep;207:634–640. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1964.207.3.634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MONROE R. G., FRENCH G., WHITTENBERGER J. L. Effects of hypocapnia and hypercapnia on myocardial contractility. Am J Physiol. 1960 Dec;199:1121–1124. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1960.199.6.1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McARDLE L., RODDIE I. C., SHEPHERD J. T., WHELAN R. F. The effect of inhalation of 30% carbon dioxide on the peripheral circulation of the human subject. Br J Pharmacol Chemother. 1957 Sep;12(3):293–296. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1957.tb00137.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDowall D. G., Ledingham I. M., Tindal S. Alveolar-arterial gradients for oxygen at 1, 2, and 3 atmospheres absolute. J Appl Physiol. 1968 Mar;24(3):324–329. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1968.24.3.324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGinn F. P., Mendel D., Perry P. M. The effects of alteration of CO2 and pH on intestinal blood flow in the cat. J Physiol. 1967 Oct;192(3):669–680. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1967.sp008324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng M. L., Levy M. N., Zieske H. A. Effects of changes of pH and of carbon dioxide tension on left ventricular performance. Am J Physiol. 1967 Jul;213(1):115–120. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1967.213.1.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Opie L. Effect of extracellular pH on function and metabolism of isolated perfused rat heart. Am J Physiol. 1965 Dec;209(6):1075–1080. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1965.209.6.1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parratt J. R., Grayson J. Myocardial vascular reactivity after beta-adrenergic blockade. Lancet. 1966 Feb 12;1(7433):338–340. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(66)91321-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parratt J. R. The effect of adrenergic neurone blockade on the myocardial circulation. Br J Pharmacol Chemother. 1967 Nov;31(3):513–522. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1967.tb00416.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROSS R. S., UEDA K., LICHTLEN P. R., REES J. R. MEASUREMENT OF MYOCARDIAL BLOOD FLOW IN ANIMALS AND MAN BY SELECTIVE INJECTION OF RADIOACTIVE INERT GAS INTO THE CORONARY ARTERIES. Circ Res. 1964 Jul;15:28–41. doi: 10.1161/01.res.15.1.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratliff N. B., Hackel D. B., Mikat E. Myocardial oxygen metabolism and myocardial blood flow in dogs in hemorrhagic shock. Circ Res. 1969 Jun;24(6):901–909. doi: 10.1161/01.res.24.6.901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rees J. R., Redding V. J. Anastomotic blood flow in experimental myocardial infarction. A new method, using 133-Xenon clearance, for repeated measurements during recovery. Cardiovasc Res. 1967 Apr;1(2):169–178. doi: 10.1093/cvr/1.2.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheuer J. The effects of respiratory and metabolic alkalosis on coronary flow, hemodynamics and myocardial carbohydrate metabolism. Cardiologia. 1968;52(5):275–286. doi: 10.1159/000166128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TORRES G. E. VALIDATION OF OXYGEN ELECTRODE FOR BLOOD. J Appl Physiol. 1963 Sep;18:1008–1011. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1963.18.5.1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wendling M. G., Eckstein J. W., Abboud F. M. Cardiovascular responses to carbon dioxide before and after beta-adrenergic blockade. J Appl Physiol. 1967 Feb;22(2):223–226. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1967.22.2.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZIERLER K. L. EQUATIONS FOR MEASURING BLOOD FLOW BY EXTERNAL MONITORING OF RADIOISOTOPES. Circ Res. 1965 Apr;16:309–321. doi: 10.1161/01.res.16.4.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]