Abstract

Class II histone deacetylases (HDACs) 4, 5, 7, and 9 repress muscle differentiation through associations with the myocyte enhancer factor 2 (MEF2) transcription factor. MEF2-interacting transcription repressor (MITR) is an amino-terminal splice variant of HDAC9 that also potently inhibits MEF2 transcriptional activity despite lacking a catalytic domain. Here we report that MITR, HDAC4, and HDAC5 associate with heterochromatin protein 1 (HP1), an adaptor protein that recognizes methylated lysines within histone tails and mediates transcriptional repression by recruiting histone methyltransferase. Promyogenic signals provided by calcium/calmodulin-dependent kinase (CaMK) disrupt the interaction of MITR and HDACs with HP1. Since the histone methyl-lysine residues recognized by HP1 also serve as substrates for deacetylation by HDACs, the interaction of MITR and HDACs with HP1 provides an efficient mechanism for silencing MEF2 target genes by coupling histone deacetylation and methylation. Indeed, nucleosomal histones surrounding a MEF2-binding site in the myogenin gene promoter are highly methylated in undifferentiated myoblasts, when the gene is silent, and become acetylated during muscle differentiation, when the myogenin gene is expressed at high levels. The ability of MEF2 to recruit a histone methyltransferase to target gene promoters via HP1-MITR and HP1-HDAC interactions and of CaMK signaling to disrupt these interactions provides an efficient mechanism for signal-dependent regulation of the epigenetic events controlling muscle differentiation.

The assembly of chromatin into higher-order structures plays a critical role in the control of gene transcription. The structure of chromatin is profoundly influenced by posttranslational modifications of the conserved amino-terminal tails of histones. Acetylation, methylation, and phosphorylation of histones have been shown to control the on-off states of genes by creating a code that is interpreted by transcriptional activators and repressors that recognize these specific histone modifications (reviewed in reference 14). Emerging data suggest that extracellular cues alter signal-responsive genes in part by changing the activities, subcellular localization, and protein-protein interactions of histone-modifying enzymes.

Acetylation of histone tails by histone acetyltransferases (HATs) results in chromatin relaxation due to disruption of histone-DNA and histone-histone interactions. Acetylated histones also serve as binding sites for bromo-domain proteins, which possess HAT activity and act as transcriptional activators (6, 13, 34, 45). Conversely, histone deacetylation by histone deacetylases (HDACs) results in chromatin condensation and transcriptional repression (reviewed in references 15 and 31). Recent studies have also revealed an important role for histone methylation as an epigenetic mechanism for the regulation of heterochromatin assembly and gene silencing (27, 30, 35, 36, 39). Methylation of lysine 9 in the tail of histone H3 by the SUV39H1 histone methyltransferases (HMTases) results in repression of transcription by creating binding sites for chromodomain (CD) proteins such as heterochromatin protein 1 (HP1), which represents a family of adaptor proteins involved in transcriptional silencing (4, 17, 37). HP1 associates with a variety of transcriptional repressors and thereby provides a mechanism for widespread silencing of gene expression in response to histone methylation (18, 32, 38).

Since the lysines in histone tails that are methylated by HMTases are also the substrates for HATs (reviewed in reference 14), HDACs play an intermediary role in these modifications by removing the acetate group and thereby creating a substrate site for either HATs or HMTases. Vertebrate HDACs are categorized into three classes based on homology with three distinct yeast HDACs (reviewed in reference 10). The class I HDACs HDAC1, -2, -3, and -8 are expressed ubiquitously, while the class II HDACs HDAC4, -5, -7, and -9 are expressed in a tissue-restricted manner, with highest expression in heart, brain, and skeletal muscle. These class II HDACs are also distinguished by an amino-terminal extension that mediates association with myocyte enhancer factor 2 (MEF2), which regulates muscle differentiation (7, 19-22, 28, 42, 48; reviewed in reference 24), and C-terminal binding protein (CtBP), a widely expressed transcriptional corepressor (47). Class I and II HDACs are also capable of homo- and heterodimerization, which allow for the formation of multicomponent HDAC complexes (11, 41, 44), and recent evidence suggests that repression by class II HDACs requires the recruitment of class I HDACs (8, 9).

Another unique characteristic of class II HDACs is their signal responsiveness. The amino-terminal extensions of HDAC4, -5, -7, and -9 contain two conserved serine residues that are targets for phosphorylation by calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase (CaMK) (22). When phosphorylated by CaMK, these phosphoserines in class II HDACs are bound by 14-3-3 chaperone proteins, resulting in the dissociation of MEF2-HDAC complexes. HDAC4, -5, -7, and -9 are also exported from the nucleus to the cytoplasm as a result of their association with 14-3-3 proteins, which mask the HDAC nuclear localization sequence while exposing the HDAC nuclear export sequence (12, 16, 23, 25, 43). MEF2-interacting transcriptional repressor (MITR) is a naturally occurring splice variant of HDAC9 that shares high homology with the amino-terminal extensions of class II HDACs but lacks a catalytic domain (41, 48, 49). Like class II HDACs, MITR acts as a transcriptional repressor and is subject to CaMK-mediated release from MEF2. However, MITR cannot be exported from the nucleus due to the absence of a nuclear export sequence (25, 48). Since MITR lacks intrinsic HDAC catalytic activity, it is thought to repress transcription by recruiting other corepressors, such as CtBP and HDACs (41, 47, 50).

To further understand the mechanisms that regulate the activities of MITR and class II HDACs, we screened for MITR-interacting proteins by using the yeast two-hybrid system. Here we show that MITR, as well as HDAC4 and -5, associate with HP1 and that CaMK signaling disrupts these interactions through a mechanism independent of the phosphoacceptors in MITR and HDACs that mediate binding to 14-3-3 proteins. Furthermore, the acetylation and methylation states of histone H3 lysine 9 at a MEF2 element in the myogenin gene promoter, which becomes activated during muscle differentiation, showed reciprocal changes during skeletal myogenesis, with the histone H3 lysine 9 being methylated in undifferentiated myoblasts and acetylated in differentiated myotubes. The association of MITR and HDACs with HP1 provides a mechanism for efficiently coupling histone deacetylation and methylation and for regulating these modifications in response to signaling events that promote cellular differentiation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Yeast two-hybrid screen.

A cDNA encoding a mutant of MITR containing alanines in place of serines 218 and 448 was fused in frame to the yeast GAL4 DNA-binding domain (GAL4-MITR S218/448A) and used as bait to screen a mouse embryonic day 17 cDNA library (Clontech), as described previously (47). Positive clones were isolated via growth on selection medium and on the basis of β-galactosidase expression. Putative positive clones were further tested for specificity using the GAL4 DNA binding domain alone as the bait. Those clones specific for interaction with GAL4-MITR S218/448A were subjected to sequencing. Filter lift and liquid β-galactosidase assays were performed according to the recommendations of the manufacturer (Clontech).

Plasmid construction.

All yeast two-hybrid baits were constructed in the pGBKT7 vector (Clontech). Mammalian expression vectors for epitope-tagged derivatives of human HDAC4, HDAC5, HDAC1, and HDAC3 and mouse CtBP1 and MITR have been described previously (47). Complementary DNAs encoding amino-terminally Myc- or FLAG-tagged MITR mutants and mouse HP1α, -β, and -γ were cloned into the pcDNA3.1 mammalian expression vector (Invitrogen). T. Kouzarides kindly provided the mammalian expression plasmid for hemagglutinin (HA)-SUV39H1. Expression of glutathione S-transferase (GST)-HP1 derivatives or GST-MITR (389 to 506) was achieved by using the pGEX-KG bacterial expression vector (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). The cDNA for constitutively activated CaMKI, which contains a stop codon in place of isoleucine 294, was provided by A. Means. A derivative of this cDNA encoding an HA-tagged version of activated CaMKI was constructed in pcDNA3.1. The integrity of all plasmids was confirmed by sequencing.

Cell culture and transfection.

COS, 293T, and C2 cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) containing 10% fetal bovine serum, 2 mM l-glutamine, and penicillin-streptomycin. For differentiation of C2 cells, confluent myoblasts in growth medium (DMEM containing 10% fetal bovine serum) were shifted to differentiation medium (DMEM containing 2% horse serum) for 2 days.

Transfections were performed with the lipid-based reagent Fugene 6 (Roche Molecular Biochemicals) and cells growing at a density of 5 × 105 to 10 × 105 cells/35-mm-diameter dish. For MEF2-dependent transcription assays, COS cells in 35-mm-diameter dishes were transfected with a luciferase reporter plasmid under control of three copies of consensus MEF2-binding site and the E1b minimal promoter, 3XMEF2-luciferase, and pcDNA3.1-based expression plasmids for MEF2C, MITR, and HP1α. A plasmid encoding β-galactosidase under the control of the cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter, CMV-lacZ, was included for transfection normalization. Cells were harvested 36 h after transfection, and luciferase and β-galactosidase values were measured under conditions of linearity with respect to time and cell extract concentration.

GST interaction assays.

GST fusions of wild-type HP1α, -β, and -γ, HP1α deletion mutants, and residues 389 to 506 of mouse MITR were expressed in the BL21(DE3) strain of Escherichia coli and purified by using glutathione-conjugated agarose beads (Sigma). 35S-labeled HDACs, HP1α, SUV39H1, or CtBP1 was generated by using the TNT kit (Promega). Ten microliters (∼10,000 cpm) of labeled protein was mixed with 0.5 to 1 μg of GST fusion protein-bound agarose beads in GST binding buffer composed of phosphate-buffered saline containing 0.5% Triton X-100, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and protease inhibitors (Complete; Roche Molecular Biochemicals) for 1 h at 4°C. Beads were collected by brief centrifugation and washed five times in GST binding buffer. Bound proteins were resolved by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and analyzed by autoradiography.

Coimmunoprecipitation assays.

COS or 293T cells were transiently transfected with plasmids encoding the indicated proteins and were harvested at 48 h posttransfection in lysis buffer composed of PBS containing 0.5% Triton X-100, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM PMSF and protease inhibitors (Complete; Roche Molecular Biochemicals). Following brief sonication and removal of cellular debris by centrifugation, FLAG-tagged proteins were immunoprecipitated from cell lysates by using anti-FLAG resin (M2; Sigma). Alternatively, Myc-tagged proteins were precipitated with rabbit polyclonal anti-Myc antibody (A-14; Santa Cruz) and protein A/G Plus beads (Santa Cruz). The bound proteins were washed five times with lysis buffer, resolved by SDS-PAGE, and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. Membranes were immunoblotted with either anti-Myc antibody (9E10; Santa Cruz), anti-HA antibody (Y-11; Santa Cruz), or anti-FLAG antibody (M2; Sigma), and proteins were visualized with a chemiluminescence detection system (Santa Cruz).

HDAC assays.

HDAC activity was assayed as described previously (20). Briefly, immunoprecipitates were washed twice in HD buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 150 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol) and incubated with ∼20,000 cpm of 3H-acetylated histones derived from MEL-TK cells in HD buffer at 37°C for 1.5 h. Reactions were terminated by addition of acetic acid and HCl to final concentrations of 0.12 and 0.72 M, respectively, and extracted with 600 μl of ethyl acetate. The released [3H]acetate was measured by scintillation counting of the organic phase.

ChIP assays.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays with C2C12 myoblasts or multinucleated myotubes were performed as described previously (21). Briefly, equal amounts of soluble chromatin were immunoprecipitated from each sample with either an anti-acetyl histone H3 lysine 9-lysine 14 or an anti-dimethyl histone H3 lysine 9 antibody (Upstate Biotechnology). Ten percent of the immunoprecipitated DNA was subjected to PCR for 28 cycles with primers specific for either the myogenin gene promoter or the glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) gene promoter. Primer sequences that flank the MEF2 site in the myogenin gene promoter have been described previously (21). Primers were also designed to flank the transcription start site in the GAPDH gene: plus, 5′-GCTCTCTGCTCCTCCCTGTT-3′; minus, 5′-CAATCTCCACTTTGCCACTGC-3′. As a control for DNA input, PCR was also performed with chromatin prior to immunoprecipitation. [α-32P]dCTP was included in the PCRs to facilitate visualization and quantitation of DNA. Twenty percent of each PCR mixture was resolved through a 5% native acrylamide gel, visualized, and quantified using a phosphorimager (Molecular Dynamics).

RESULTS

Association of HP1α with MITR and class II HDACs.

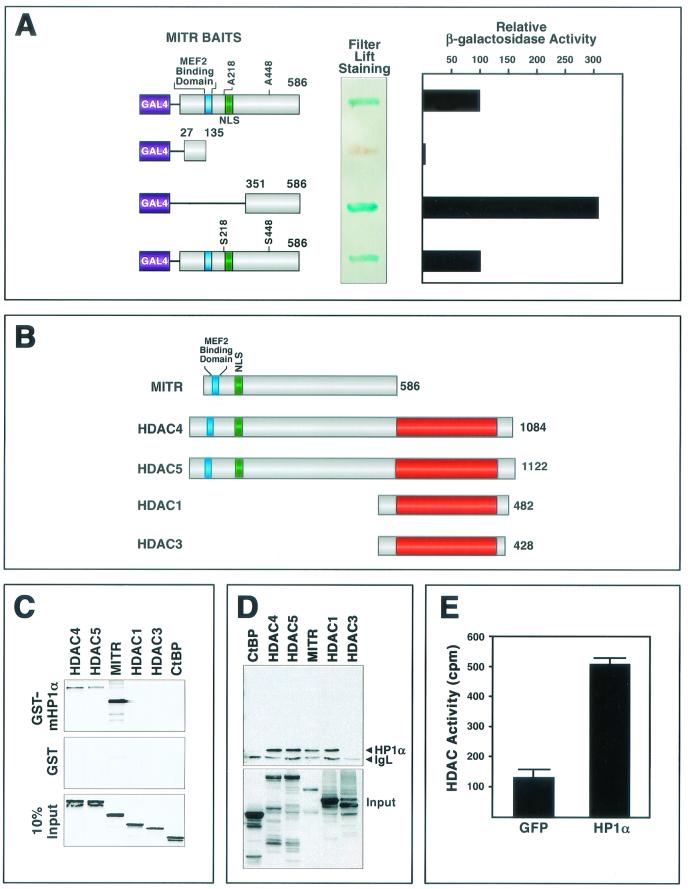

To investigate the mechanisms involved in transcriptional repression by MITR, we performed yeast two-hybrid screens with a cDNA encoding MITR fused in frame to the GAL4 DNA-binding domain as bait (Fig. 1A). We initially used a mutant of MITR containing alanines in place of serines 218 and 448 (MITR S218/448A) to abolish the binding of MITR to 14-3-3 proteins, a family of ubiquitously expressed proteins that associate with MITR when these serines are phosphorylated (48). One of the most strongly interacting clones in this screen encoded full-length HP1α. The HP1α-GAL4 activation domain prey identified in the screen did not interact with a variety of nonspecific GAL4 baits (data not shown), indicating that its association with the GAL4-MITR S218/448A bait was specific. The association of HP1α with wild-type MITR in yeast two-hybrid assays was as efficient as that with the MITR S218/448A mutant, suggesting that the alanine substitutions did not affect the binding (Fig. 1A). By using two MITR deletions fused to the GAL4 DNA-binding domain as baits, the HP1α-interacting region of MITR was localized to residues 351 to 586 (Fig. 1A).

FIG.1.

Association of HP1α with MITR and class II HDACs. (A) Interaction of HP1α and MITR in yeast. A mutant of MITR containing alanines in place of serines 218 and 448 (MITR S218/448A) was fused to the GAL4 DNA-binding domain and used as bait in a yeast two-hybrid screen (see Materials and Methods). A positive clone encoding full-length HP1α was rescued as a prey. The relative association of HP1α with the indicated MITR baits was determined by measuring the activity of a β-galactosidase reporter in yeast filter lift or liquid culture assays. Values from the liquid culture assay are expressed as activity relative to that seen with MITR S218/448A and HP1α. (B) Schematic diagrams of MITR and HDACs. The MEF2-binding region and nuclear localization signals (NLS) of MITR, HDAC4, and HDAC5 are indicated by the blue and green boxes, respectively. The red boxes indicate the HDAC catalytic domain. The number of amino acids in each protein is shown at the right. (C) GST pull-down assays. GST-HP1α (top panel) or GST alone (middle panel) was expressed in E. coli, conjugated to glutathione-agarose beads, and incubated with [35S]methionine-labeled MITR and HDACs, as described in Materials and Methods. Associated proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by autoradiography (top and middle panels). In the bottom panel, 10% of the [35S]methionine-labeled protein was applied directly to the gel to control for input. (D) COS cells were cotransfected with expression vectors encoding Myc-tagged HP1α and the indicated FLAG-tagged proteins (1 μg each). FLAG-tagged proteins were immunoprecipitated from cell lysates with a monoclonal anti-FLAG antibody, and coimmunoprecipitating Myc-tagged proteins were detected by immunoblotting with a polyclonal anti-Myc antibody (upper panel). The positions of Myc-HP1α and the light chain of immunoglobulin (IgL) are indicated. The membrane was reprobed with anti-FLAG antibody to reveal total immunoprecipitated FLAG-tagged protein (bottom panel). (E) 293T cells were transiently transfected with expression vectors encoding Myc-tagged HP1α or GFP. At 48 h posttransfection, cell extracts were immunoprecipitated with anti-Myc antibody and immune complexes were assayed for HDAC activity as described in Materials and Methods. Values represent means ± standard deviations.

To further test the specificity of the interaction between MITR and HP1α, we performed binding assays with a bacterially expressed GST-HP1α fusion protein and in vitro-translated MITR and HDAC proteins (Fig. 1B). GST-HP1α interacted efficiently with 35S-methionine-labeled MITR, as well as with HDAC4 and HDAC5 (Fig. 1C). No interaction was detected between GST-HP1α and HDAC1, HDAC3, or the CtBP corepressor, which also associates with class II HDACs and MITR (47).

The association of HP1α with MITR and class II HDACs was further tested by coimmunoprecipitation assays using protein lysates from transfected cells. Consistent with the GST binding experiments, Myc-tagged HP1α associated with FLAG-tagged MITR, HDAC4, and HDAC5, and in this assay, these three proteins bound HP1α with comparable efficiencies (Fig. 1D). HP1α did not interact with HDAC3 in the coimmunoprecipitation assay, but in contrast to the GST binding experiments, HDAC1 could be coimmunoprecipitated with HP1α (Fig. 1D). Although the basis for this difference between the two assays remains unknown, it could reflect a role for additional cellular proteins that are present in the cell extracts but absent from GST pull-down assays. For example, class II HDACs can interact with HDAC1 (11, 41). Thus, endogenous class II HDACs in COS cells could potentially interact with Myc-tagged HP1α and recruit FLAG-tagged HDAC1 to the complex. Notwithstanding this uncertainty, our results reveal that HP1α is capable of associating with MITR and class II HDACs in three independent assays: yeast two-hybrid interaction, GST pull-down, and coimmunoprecipitation.

As a final test for the interaction between HP1α and HDACs, we expressed Myc-tagged HP1α in 293T cells, which express both class I and class II HDACs, and performed HDAC assays on anti-Myc epitope immunoprecipitates (Fig. 1E). Deacetylase activity was readily detectable in the immune complex, indicating that HP1α associated with endogenous HDACs.

Mapping the region of MITR that interacts with HP1α.

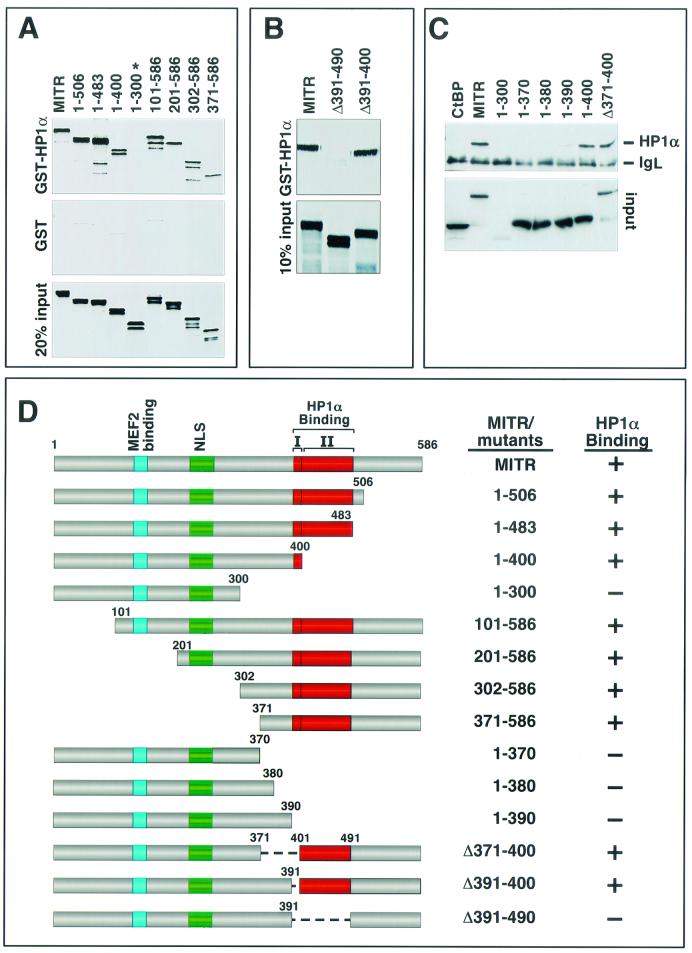

In order to map the region of MITR that mediates the association with HP1α, we initially generated a series of MITR deletion mutants and assessed their capacities to associate with GST-HP1α (Fig. 2A, B, and C). Deletion of residues from amino acid 400 to the carboxyl terminus of MITR had no effect on HP1α binding, whereas a deletion mutant containing amino acids 1 to 300 (mutant 1-300) failed to bind HP1α. Deletions from the amino terminus showed that mutants lacking up to the first 370 amino acids had no effect on MITR-HP1α interaction (see mutant 371-586). Based on these assays, the HP1α-interacting region was localized to residues 371 to 400 of MITR. Surprisingly, however, an internal deletion mutant of MITR lacking residues 371 to 400 (mutant Δ371-400) also bound HP1α (Fig. 2C), indicating that more than one domain in MITR can mediate HP1α binding.

FIG.2.

Mapping of the HP1α-binding region of MITR. (A) Association of GST-HP1α with amino- and carboxy-terminal MITR deletions. GST-HP1α (top panel) or GST alone (middle panel) was expressed in E. coli, conjugated to glutathione-agarose beads, and incubated with the indicated [35S]methionine-labeled MITR deletion mutants. Associated proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by autoradiography (top and middle panels). The only MITR mutant that failed to interact with HP1α in this assay (mutant 1-300) is indicated with an asterisk. In the bottom panel, 20% of the [35S]methionine-labeled protein was applied directly to the gel to control for input. (B) Association of GST-HP1α with internal deletion mutants of MITR. The ability of GST-HP1α (top panel) to associate with the indicated MITR proteins was determined as described for panel A. In the bottom panel, 10% of the 35S-labeled MITR was applied directly to the gel to control for input. None of the MITR proteins exhibited significant binding to GST alone (data not shown). (C) COS cells were cotransfected with expression vectors encoding FLAG-tagged HP1α and the indicated Myc-tagged MITR proteins or CtBP (1 μg each). Myc-tagged proteins were immunoprecipitated from cell lysates with a polyclonal anti-Myc antibody, and coimmunoprecipitating FLAG-tagged proteins were detected by immunoblotting with a monoclonal anti-FLAG antibody (top panel). The positions of FLAG-HP1α and the light chain of immunoglobulin (IgL) are indicated. The membrane was reprobed with anti-Myc antibody to reveal the total amount of immunoprecipitated Myc-tagged protein (bottom panel). (D) Schematic representations of MITR proteins and their interactions with HP1α. There are two adjacent domains that are predicted to form α-helices (I and II); each is sufficient to mediate HP1α-binding. NLS, nuclear localization signal.

The HP1α-interacting region of MITR was further delineated by coimmunoprecipitation assays using Myc-tagged MITR mutants and FLAG-tagged HP1α expressed in transfected cells (Fig. 2C). Progressive extension of mutant 1-300 toward the carboxyl terminus showed that residues through amino acid 390 were insufficient to mediate HP1α binding, whereas mutant 1-400 bound HP1α as efficiently as wild-type MITR. These results are consistent with the GST pull-down results (Fig. 2A) and further suggest that amino acids 391 to 400 of MITR are important for association with HP1α.

Sequence analysis of MITR failed to reveal amino acids that were conserved between residues 391 to 400 and elsewhere in the protein that could account for the association of the Δ391-400 mutant of MITR with HP1α; however, through sequence analysis by the program NPS@ (http://pbil.ibcp.fr/cgi-bin/secpred_consensus.pl), the predicted secondary structure of MITR suggests that amino acids 391 to 400 form an α-helix and that another α-helical stretch is formed by the amino acids immediately carboxy terminal to this region (Fig. 2D). Consistent with a role for both putative α-helices in governing the interaction between MITR and HP1α, the Δ391-490 mutant of MITR, lacking these two helices in the context of the full-length protein, completely failed to bind HP1α in the GST pull-down assay (Fig. 2B).

Together, these results indicate that there are at least two independent HP1α-binding domains in MITR (Fig. 2D), each of which is sufficient to mediate the HP1α interaction. One HP1-interacting domain is located between amino acids 390 and 400, and the other is located between amino acids 400 and 490.

Mapping the region of HP1α that interacts with MITR.

HP1 proteins contain three distinct domains. The amino-terminal CD, which binds methyl-lysine 9 of histone H3, is separated from the carboxy-terminal chromoshadow domain (CSD), which mediates a variety of protein-protein interactions, by a central variable hinge region (Fig. 3B). Specific functions have not been ascribed to the hinge region, although it has been shown to interact with histone H1 and INCENP (2, 33). There are three mammalian HP1 proteins, HP1α, -β, and -γ, which are highly homologous in the CSD and CD domains but are divergent in the hinge regions.

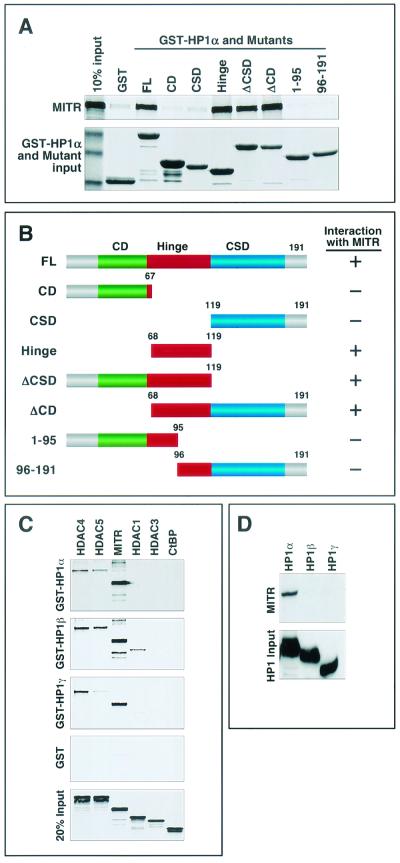

FIG. 3.

Mapping of the MITR-binding region of HP1α. (A) Binding of [35S]methionine-labeled MITR to GST-HP1α deletion mutants. HP1α and a series of HP1α deletion mutants, as shown in panel B, were fused to GST, expressed in E. coli, and conjugated to glutathione-agarose beads. [35S]methionine-labeled MITR was mixed with GST-HP1α-bound beads, and associated MITR was resolved by SDS-PAGE. Following electrophoresis, the GST-HP1 fusion proteins were stained with Coomassie blue dye (bottom panel), and then the amount of HP1-associated MITR was assessed by autoradiography (top panel). In lane 1 (top panel), 10% of the input [35S]methionine-labeled MITR was applied directly to the gel. Lane 2 shows only a low level of MITR associated with GST alone. (B) Schematic representations of full-length HP1α (FL) and mutants containing or lacking (Δ) the CD (green box), the CSD (blue box), or the hinge region (red box) of the protein. A summary of the GST pull-down data is shown to the right (+, association with MITR; −, no significant association with MITR). (C) Bacterially expressed GST-HP1β and GST-HP1γ were used in GST pull-down assays with 35S-labeled HDAC4, HDAC5, MITR, HDAC1, HDAC3, or CtBP as described for Fig. 1C. (D) COS cells were cotransfected with expression vectors encoding Myc-tagged MITR and FLAG-tagged HP1α, -β, or -γ. Ectopic HP1 proteins were immunoprecipitated from cell lysates with anti-FLAG antibodies, and associated MITR was detected with a polyclonal anti-Myc antibody (top panel). The membrane was reprobed with anti-FLAG antibody to reveal immunoprecipitated HP1 (bottom panel).

The region of HP1α that bound MITR was mapped by in vitro binding assays using 35S-labeled MITR and a series of GST-HP1α deletion mutants. As shown in Fig. 3A, neither the CD nor the CSD was able to interact with MITR, whereas the hinge region alone and deletion mutants lacking the CSD or the CD but containing the hinge region (ΔCSD and ΔCD) bound to MITR. Mutations that bisected the hinge region abolished interaction with MITR, suggesting that the interaction motif extends across this region. These results indicate that the hinge region of HP1α is necessary and sufficient for association with MITR.

We also examined whether HP1β and HP1γ interacted with MITR. For this purpose, the β and γ isoforms of HP1 were fused to GST, expressed in E. coli, and tested for the ability to associate with in vitro-translated MITR, HDACs or the CtBP corepressor. As shown in Fig. 3C, the interactions of HP1β and HP1γ with MITR and class II HDAC4 and HDAC5 were comparable to those of HP1α, although GST-HP1β and -HP1γ also modestly associated with HDAC1. In contrast, in coimmunoprecipitation assays using lysates from transfected cells, neither HP1β nor HP1γ interacted with MITR (Fig. 3D). We have not further investigated the divergent results between these assays, although we hypothesize that they reflect roles for cellular proteins in modulating the interactions.

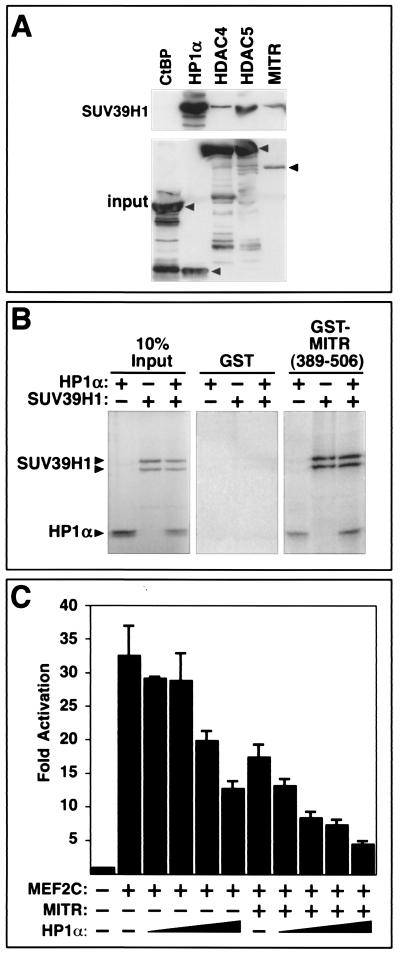

Complex formation between HP1α, HDACs, and SUV39H1.

HP1 associates with the HMTase SUV39H1 (1), which provides a potential mechanism for coupling methylation of lysine 9 on histone H3 with the protection of this methyl group by the binding of HP1. To determine whether HP1 could associate simultaneously with SUV39H1 and class II HDACs to form a multiprotein histone modification and protection complex, we performed coimmunoprecipitation assays with HA-tagged SUV39H1 and FLAG-tagged versions of HP1α, HDACs, and MITR (Fig. 4A). HP1α was readily immunoprecipitated with SUV39H1, consistent with previous studies (1). In addition, HDAC4, HDAC5, and MITR were detected in SUV39H1 immune complexes, although the efficiency of their association with SUV39H1 was substantially lower than that of HP1α. The CtBP corepressor did not associate with SUV39H1, demonstrating the specificity of the assay. These results were consistent with those from GST pull-down assays (Fig. 4B), where a GST fusion protein containing amino acids 389 to 506 of MITR efficiently associated with 35S-labeled HP1α or SUV39H1 individually or in combination. These results suggest that HP1α and SUV39H1 can form a complex with MITR. However, since the experiments were performed with rabbit reticulocyte lysates, whether or not MITR associates directly with SUV39H1 or through an intermediary such as HP1 remains unclear.

FIG. 4.

Association of MITR and class II HDACs with SUV39H1 and HP1α-mediated repression of MEF2C. (A) Coimmunoprecipitation of MITR and HDAC4 and -5 with SUV39H1. COS cells were cotransfected with expression vectors encoding HA-tagged SUV39H1 and the indicated FLAG-tagged proteins. FLAG-tagged proteins were immunoprecipitated from cell lysates with a monoclonal anti-FLAG antibody, and coimmunoprecipitating SUV39H1 was detected by immunoblotting with an anti-HA antibody (top panel). The membrane was reprobed with anti-FLAG antibody to reveal immunoprecipitated FLAG-tagged proteins (bottom panel). Arrows indicate the positions of full-length CtBP, HP1α, HDAC4, HDAC5, and MITR. (B) Association of HP1α and SUV39H1 with MITR by GST pull-down assays. Residues 389 to 506 of MITR were fused to GST and expressed in bacteria. The GST-MITR fusion protein was then conjugated to glutathione agarose beads and used in pull-down assays with 35S-labeled HP1α and SUV39H1. The associated proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE and visualized using a phosphorimager. GST alone was used as negative control. Ten percent of the 35S-labeled protein was also directly applied to the gel to control for protein input. The positions of labeled HP1α and SUV39H1, which appears as a doublet, are indicated with arrows. (C) Inhibition of MEF2 transcriptional activity by HP1α. COS cells were transiently transfected with expression vectors for HP1α (0.1 to 0.8 μg), MEF2C (0.2 μg), MITR (5 ng), a MEF2-dependent reporter plasmid (3XMEF2-luciferase; 0.1 μg), and a CMV-lacZ reporter (0.1 μg) to control for differences in transfection efficiency. Luciferase activity was determined as described in Materials and Methods. Values represent means ± standard deviations.

Repression of MEF2-dependent transcription by HP1α.

Given the ability of HP1 to associate with MITR and class II HDACs, we performed experiments to determine whether or not HP1 contributes to the mechanism by which these factors repress MEF2-dependent transcription. As shown in Fig. 4C, HP1α was capable of repressing a MEF2-dependent reporter gene in a dose-dependent manner, and the inhibitory action of HP1 was enhanced by a small amount of exogenous MITR. These results suggest that HP1 is recruited to MEF2 via MITR and class II HDACs to form a more potent transcriptional repression complex.

Reduced histone methylation during skeletal muscle differentiation.

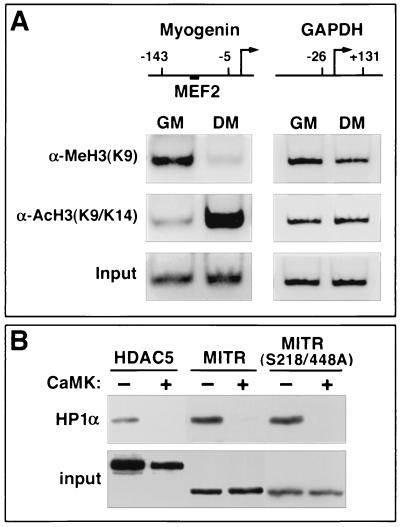

Since MITR, HDAC4, and HDAC5 are capable of associating with HP1α and SUV39H1, and since MITR and HDACs are released from MEF2 during muscle differentiation, we hypothesized that the relative states of histone methylation and acetylation at a MEF2-binding site in muscle-specific genes would be altered during myogenesis. To test this hypothesis, we performed ChIP assays. Soluble chromatin was prepared from proliferating myoblasts or differentiated myotubes and was subjected to immunoprecipitation with antibodies specific for methylated lysine 9 of histone H3 or acetylated K9 and K14 of histone H3. The amount of precipitated DNA was determined by PCR using primers that flank a functional MEF2 site in the myogenin gene promoter, which is dramatically upregulated during muscle differentiation. As shown in Fig. 5A, histone H3 acetylation on the myogenin promoter was significantly increased in differentiated myotubes relative to undifferentiated myoblasts. In contrast, the degree of histone H3 lysine 9 methylation was significantly higher in proliferating myoblasts than in myotubes. These dynamic changes in the modification state of nucleosomal histones correlated precisely with the expression level of the myogenin gene (data not shown) and were not due to nonspecific consequences of differentiation, since there was no change in the state of histone acetylation or methylation in the GAPDH promoter, which is expressed at comparable levels in myoblasts and myotubes. These data support a model in which MEF2 recruits an HMTase to target genes via HP1 and HDAC or MITR, resulting in transcriptional repression. In response to myogenic cues, HDACs and MITR are released from MEF2, allowing the transcription factor to associate with HATs, which acetylate nucleosomal histones and promote gene expression (see Fig. 6C).

FIG. 5.

Effects of promyogenic signals on histone H3 methylation and MITR or HDAC-HP1 complexes. (A) Methylation and acetylation states of histone H3 lysine 9 on a MEF2-binding element during myogenesis. Soluble chromatin from C2 myoblasts in growth medium (GM) or from confluent myotubes in differentiation medium (DM) was subjected to immunoprecipitation with antibodies specific for dimethylated lysine 9 of histone H3 [α-MeH3(K9)] or acetylated lysine 9 and 14 of histone H3 [α-AcH3(K9/K14)]. Precipitated DNA was used as a template for PCR with primers spanning either the MEF2-binding site on the myogenin gene promoter or the transcription start site of the GAPDH gene promoter. The positions of the primer-binding sites (numbers) relative to the transcription start sites (arrows) are indicated. The position of the MEF2-binding element within the myogenin promoter is shown. PCR was also performed using genomic DNA prior to immunoprecipitation to control for equal input of chromatin (bottom panel). (B) CaMK-mediated dissociation of HP1α from MITR and HDAC5. COS cells were cotransfected with expression vectors encoding FLAG-tagged HP1α and Myc-tagged HDAC5 or Myc-tagged versions of wild-type MITR (MITR) or a mutant of MITR containing alanines in place of serines 218 and 448 (MITR S218/448A) in the absence or presence of an expression vector encoding activated CaMKI. Myc-tagged proteins were immunoprecipitated from cell lysates with a polyclonal anti-Myc antibody, and coimmunoprecipitating FLAG-tagged HP1α was detected by immunoblotting with a monoclonal anti-FLAG antibody (top panel). The membrane was reprobed with anti-Myc antibody to reveal immunoprecipitated HDAC5 and MITR (bottom panel).

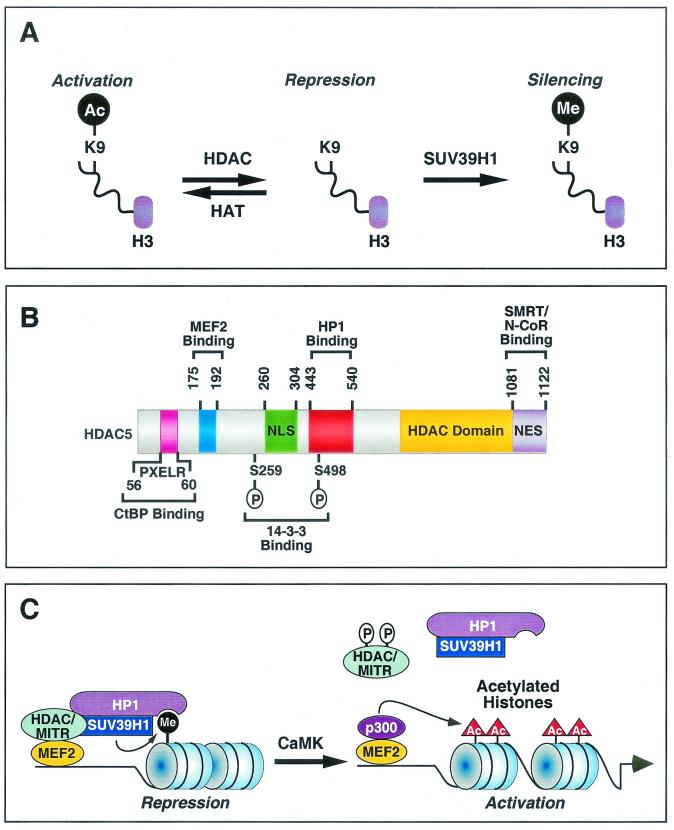

FIG. 6.

Regulation of gene expression by HDAC and MITR-HP1 interactions. (A) Acetylation (Ac) of lysine 9 (K9) on nucleosomal histone H3 by HATs relaxes chromatin structure, resulting in gene activation. In contrast, removal of the acetyl group from K9 by HDACs results in chromatin condensation and gene repression. Deacetylated K9 is a substrate for the HMTase SUV39H1. Methylation of K9 by SUV39H1 further enhances the repressive state of chromatin. (B) Schematic diagram of human HDAC5 showing functional domains and binding regions for cofactors. These functional domains and binding sites are conserved in HDAC4, HDAC7, HDAC9, and MITR, although MITR lacks an HDAC catalytic domain and a nuclear export sequence (NES). NLS, nuclear localization signal.(C) Model for the assembly of a corepressor complex by a class II HDAC or MITR and its disassembly by CaMK signaling. HDAC or MITR, HP1 and the HMTase SUV39H1 form an efficient corepressor complex. Deacetylation of histone tails by HDAC creates substrates for SUV39H1, which is recruited to the target site by the HDAC- or MITR-HP1 complex. Methylation of histone tails by SUV39H1 generates a binding signature for HP1, which further recruits HDACs and SUV39H1 to propagate the repressive effect on the target gene. CaMK phosphorylates class II HDACs and MITR, which results in disruption of MEF2-HDAC or MEF2-MITR interactions and allows p300, which possesses HAT activity, to associate with MEF2 and acetylate regional histones. These events lead to the activation of MEF2 target gene expression. CaMK also dissociates HP1-HDAC and HP1-MITR complexes through an unknown mechanism, providing an efficient means to control histone methylation in response to extracellular cues.

Dissociation of HDACs and HP1α by CaMK signaling.

We have shown previously that CaMK mimics myogenic signals that release MEF2 from the repressive effects of class II HDACs and MITR. CaMK phosphorylates HDAC4, HDAC5, and MITR at two conserved serine residues, creating docking sites for the intracellular chaperone protein 14-3-3. When bound to 14-3-3, HDACs and MITR are released from MEF2. The association of 14-3-3 with HDAC4 and -5 also exposes a carboxy-terminal nuclear export sequence in the repressors, which results in their relocalization to the cytoplasm, thereby allowing MEF2 to stimulate muscle-specific gene expression. However, since MITR lacks the carboxy-terminal nuclear export sequence, it is not exported to the cytoplasm in response to CaMK but is relocalized within the nucleus.

Given the ability of CaMK to promote myogenesis by impinging on MEF2-HDAC or MEFZ-MITR complexes and the observed decrease in histone methylation at a MEF2 site in the myogenin gene promoter during muscle differentiation, we hypothesized that CaMK may influence the interaction of HDAC5 and MITR with HP1α. To test this hypothesis, cells were transfected with expression vectors encoding HDAC5 or MITR in the absence or presence of a construct for constitutively active CaMKI, and the integrity of HP1-HDAC or HPI-MITR complexes was assessed by coimmunoprecipitation analysis. As described above, the association of HDAC5 and MITR with HP1α was readily detectable in the absence of activated CaMK (Fig. 5B). In contrast, in the presence of activated CaMKI, there was no detectable interaction between HP1α and HDAC5 or MITR (Fig. 5B).

The CaMK phosphorylation sites in HDAC5 and MITR that are bound by 14-3-3 proteins and mediate MEF2 association and subcellular redistribution are serines 259 and 498 in HDAC5 and −218 and −448 in MITR (22, 48). To determine whether dissociation of HP1α from HDAC5 and MITR in response to CaMK signaling was mediated by phosphorylation of these sites or by a different mechanism, we examined the association of HP1α with a mutant of MITR in which these CaMK phosphorylation sites were replaced with alanine residues. As shown in Fig. 5B, the serine-to-alanine mutant of MITR (MITR S218/448A) associated with HP1α in the absence of CaMK signaling and, like wild-type MITR, dissociated from HP1α in response to CaMK. These findings demonstrate that dissociation of HP1α from HDAC5 and MITR in response to CaMK signaling is mediated by a mechanism independent of the CaMK phosphorylation sites that are bound by 14-3-3, which controls the subcellular localization of MITR as well as its association with the MEF2 transcription factor (48).

DISCUSSION

The results of this study reveal previously unrecognized interactions of HP1 with the MITR corepressor and class II HDACs. The HMTase SUV39H1 is also contained in these complexes. The association of HDACs, HMTases, and HP1 provides an efficient mechanism for modifying nucleosomal histone tails and stabilizing the methylated state of histone H3 lysine 9 via the docking of HP1. The integrity of these chromatin-remodeling complexes is subject to CaMK-dependent control, providing a means to regulate histone methylation in response to extracellular cues that alter intracellular calcium concentration and promote muscle differentiation.

Heterochromatin assembly and transcriptional silencing by HP1.

Lysine 9 of histone H3 is targeted by both acetylation and methylation. Thus, HDAC activity serves as an intermediary between the actions of HATs and HMTases by creating the substrate site for methylation upon removal of the acetate group from lysine 9 of histone H3 (Fig. 6A). The competition between acetylation and methylation of lysine 9, or other lysines in histone tails, has the potential to create a switch to determine the on-off states of genes to which the histones are associated.

The association of HDACs with HP1 may result in the propagation of the repressive state of chromatin through two distinct but related mechanisms. (i) HP1 binding to methylated histone tails may recruit class II HDACs, which could deacetylate adjacent nucleosomal histone tails, thus creating substrates for HMTase activity of SUV39H1. Methylation of these deacetylated histone tails by SUV39H1 would then create new HP1-binding sites, allowing for the subsequent recruitment of HDACs, with resulting propagation of the repressive state of chromatin. (ii) HP1 could be initially recruited to specific genes via its association with class II HDACs that are bound to these genes through interactions with sequence-specific DNA-binding proteins such as MEF2. Once localized to a specific genomic region through interaction with HDACs, the HP1-HDAC complex could also recruit the HMTase, which could methylate deacetylated histone tails that have been created by HDACs. In either case, the interactions among class II HDACs, HP1, and SUV39H1 provide a means of stabilizing the repressive state of chromatin.

In addition to interacting with SUV39H1 and HDACs, HP1 has been shown to associate with the transcriptional repressor TIF1b (32), the nuclear body component SP100 (40), the lamin B receptor (46), and the chromatin assembly factor 1 subunit p150 (29) through the CSD domain. HP1 also binds histone H3 through its CD region and histone H1 and INCENP through its hinge region (2, 33).

Assembly of repressive complexes by class II HDACs.

Class II HDACs are being found to associate with a growing number of proteins involved in transcriptional repression (Fig. 6B). Class I HDACs interact with an as-yet poorly defined region within the amino-terminal extensions of class II HDACs, as well as with the catalytic region of class II HDACs (9, 11, 41, 47). The interactions between class I and II HDACs allow for the formation of multiprotein HDAC complexes and allow for cross talk between class II HDACs, which are signal responsive and cell type restricted, and class I HDACs, which are ubiquitous. The class I HDAC HDAC1 has also been shown to interact with SU(VAR)3-9 in Drosophila, which leads to permanent transcriptional silencing of specific genomic regions (5).

The CtBP corepressor interacts with a motif near the extreme amino terminus of MITR and class II HDACs (Fig. 6B). CtBP also associates with class I HDACs and with other corepressors, such as N-CoR and SMRT, which have previously been shown to interact with class I and II HDACs. Thus, the bridging between multiple types of repressor proteins and HDACs allows for the formation of large multiprotein repressor complexes. The region of MITR and class II HDACs that recruits HP1 is distinct from the binding sites for other proteins identified thus far, which further suggests that these repressors can serve as a bridge between multiple transcriptional regulators.

Regulation of HDAC interactions by CaMK signaling.

Previous studies demonstrated that CaMK signaling leads to the phosphorylation of two conserved serine residues in the amino-terminal extensions of class II HDACs (22, 48). Phosphorylation of these sites creates docking sites for 14-3-3 chaperone proteins, which mask the nuclear localization signal and result in the unmasking of a nuclear export sequence at the carboxy termini, with resulting export of HDAC-14-3-3 complexes to the cytoplasm. CaMK-mediated phosphorylation of class II HDACs and MITR also results in dissociation from MEF2. Serine-to-alanine substitutions of these sites prevent CaMK-dependent association with 14-3-3 proteins, disruption of MEF2-HDAC complexes, and HDAC nuclear export. MITR also dissociates from MEF2 in response to CaMK signaling. However, since MITR lacks a nuclear export sequence, it is redistributed within the nucleus but is not exported to the cytoplasm in response to CaMK (48).

Like MEF2, HP1 dissociated from HDAC5 and MITR in response to CaMK signaling. However, a mutant of MITR lacking the CaMK phosphorylation sites also dissociated from HP1. These findings indicate the existence of another mechanism that confers CaMK sensitivity to the HDAC-HP1 complex. At present, we do not know the target for CaMK that mediates this response. We have identified a single CaMK phosphorylation site in HP1α. However, mutation of this site to alanine does not prevent dissociation from MITR in response to CaMK signaling (data not shown). There are numerous CaMK phosphorylation sites in HDAC5 and MITR, only two of which are required for binding of 14-3-3 proteins and dissociation from MEF2 (22, 48). Whether one or more of the other sites are responsible for signal-dependent dissociation from HP1 remains to be determined. It is also possible that other proteins mediate the effects of CaMK on the complex.

Potential role for HP1-HMTase in HDAC-dependent repression of skeletal myogenesis.

Previous studies have shown that class II HDACs play important roles in muscle cell differentiation and myocyte hypertrophy as a consequence of their association with MEF2 (20, 21). The region of class II HDACs that mediates interaction with HP1 is distinct from the MEF2-binding region. Thus, HDACs have the potential to serve as a bridge between MEF2 and HP1-HMTase (Fig. 6C). In this way, MEF2 could target the repressive complex to specific genes that are critical for muscle differentiation. Consistent with this notion, nucleosomal histones surrounding a MEF2 target site in the myogenin gene promoter, which is transcriptionally active only in differentiating muscle, are differentially modified by methylation and acetylation during myogenesis. Specifically, high levels of histone methylation are observed at this site in undifferentiated myoblasts. Upon differentiation, the level of histone methylation is decreased at this MEF2 element, with a concomitant increase in histone acetylation. Since histone methylation is thought to be irreversible, the reduction in histone methylation observed during myogenesis may be due to exchange of methylated histones with unmodified or acetylated histones through DNA synthesis. In this regard, myoblasts are still capable of synthesizing DNA immediately following serum withdrawal and prior to differentiation (3). It also remains possible that an as-yet-unidentified histone demethylase catalyzes the demethylation reaction, thus providing the substrates for subsequent acetylation by a HAT.

It is also interesting that MEF2 regulates genes involved in proliferation and differentiation, which are expressed in opposing manners (26). Whether the targeting of repressive complexes to some genes and activating complexes to others accounts for the opposing expression patterns of these MEF2 target genes is an intriguing issue to consider.

Acknowledgments

We thank T. Kouzarides, S. L. Schreiber, A. Means, and C. D. Allis for reagents and S. Huang and S. Brandt (Vanderbilt University) for advice regarding HDAC activity assays. We are grateful to A. Tizenor for graphics and to J. Page for editorial assistance.

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health, the D. W. Reynolds Clinical Cardiovascular Research Center, the Texas Advanced Technology Program, and the Robert A. Welch Foundation to E.N.O. T.A.M. is a Pfizer Fellow of the Life Sciences Research Foundation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aagaard, L., G. Laible, P. Selenko, M. Schmid, R. Dorn, G. Schotta, S. Kuhfittig, A. Wolf, A. Lebersorger, P. B. Singh, G. Reuter, and T. Jenuwein. 1999. Functional mammalian homologues of the Drosophila PEV-modifier Su(var)3-9 encode centromere-associated proteins which complex with the heterochromatin component M31. EMBO J. 18:1923-1938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ainsztein, A. M., S. E. Kandels-Lewis, A. M. Mackay, and W. C. Earnshaw. 1998. INCENP centromere and spindle targeting: identification of essential conserved motifs and involvement of heterochromatin protein HP1. J. Cell Biol. 143:1763-1774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andres, V., and K. Walsh. 1996. Myogenin expression, cell cycle withdrawal, and phenotypic differentiation are temporally separable events that precede cell fusion upon myogenesis. J. Cell Biol. 132:657-666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bannister, A. J., P. Zegerman, J. F. Partridge, E. A. Miska, J. O. Thomas, R. C. Allshire, and T. Kouzarides. 2001. Selective recognition of methylated lysine 9 on histone H3 by the HP1 chromo domain. Nature 410:120-124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Czermin, B., G. Schotta, B. B. Hulsmann, A. Brehm, P. B. Becker, G. Reuter, and A. Imhof. 2001. Physical and functional association of SU(VAR)3-9 and HDAC1 in Drosophila. EMBO Rep. 2:915-919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dhalluin, C., J. E. Carlson, L. Zeng, C. He, A. K. Aggarwal, and M. M. Zhou. 1999. Structure and ligand of a histone acetyltransferase bromodomain. Nature 399:491-496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dressel, U., P. J. Bailey, S. C. Wang, M. Downes, R. M. Evans, and G. E. Muscat. 2001. A dynamic role for HDAC7 in MEF2-mediated muscle differentiation. J. Biol. Chem. 276:17007-17013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fischle, W., F. Dequiedt, M. Fillion, M. J. Hendzel, W. Voelter, and E. Verdin. 2001. Human HDAC7 histone deacetylase activity is associated with HDAC3 in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 276:35826-35835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fischle, W., F. Dequiedt, M. J. Hendzel, M. G. Guenther, M. A. Lazar, W. Voelter, and E. Verdin. 2002. Enzymatic activity associated with class II HDACs is dependent on a multiprotein complex containing HDAC3 and SMRT/N-CoR. Mol. Cell 9:45-57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gray, S. G., and T. J. Ekstrom. 2001. The human histone deacetylase family. Exp. Cell Res. 262:75-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grozinger, C. M., C. A. Hassig, and S. L. Schreiber. 1999. Three proteins define a class of human histone deacetylases related to yeast Hda1p. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:4868-4873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grozinger, C. M., and S. L. Schreiber. 2000. Regulation of histone deacetylase 4 and 5 and transcriptional activity by 14-3-3-dependent cellular localization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:7835-7840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jacobson, R. H., A. G. Ladurner, D. S. King, and R. Tjian. 2000. Structure and function of a human TAFII250 double bromodomain module. Science 288:1422-1425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jenuwein, T., and C. D. Allis. 2001. Translating the histone code. Science 293:1074-1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnson, C. A., and B. M. Turner. 1999. Histone deacetylases: complex transducers of nuclear signals. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 10:179-188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kao, H. Y., A. Verdel, C. C. Tsai, C. Simon, H. Juguilon, and S. Khochbin. 2001. Mechanism for nucleocytoplasmic shuttling of histone deacetylase 7. J. Biol. Chem. 276:47496-47507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lachner, M., D. O'Carroll, S. Rea, K. Mechtler, and T. Jenuwein. 2001. Methylation of histone H3 lysine 9 creates a binding site for HP1 proteins. Nature 410:116-120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lechner, M. S., G. E. Begg, D. W. Speicher, and F. J. Rauscher III. 2000. Molecular determinants for targeting heterochromatin protein 1-mediated gene silencing: direct chromoshadow domain-KAP-1 corepressor interaction is essential. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:6449-6465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lemercier, C., A. Verdel, B. Galloo, S. Curtet, M. P. Brocard, and S. Khochbin. 2000. mHDA1/HDAC5 histone deacetylase interacts with and represses MEF2A transcriptional activity. J. Biol. Chem. 275:15594-15599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lu, J., T. A. McKinsey, R. L. Nicol, and E. N. Olson. 2000. Signal-dependent activation of the MEF2 transcription factor by dissociation from histone deacetylases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:4070-4075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lu, J., T. A. McKinsey, C. L. Zhang, and E. N. Olson. 2000. Regulation of skeletal myogenesis by association of the MEF2 transcription factor with class II histone deacetylases. Mol. Cell 6:233-244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McKinsey, T. A., C. L. Zhang, J. Lu, and E. N. Olson. 2000. Signal-dependent nuclear export of a histone deacetylase regulates muscle differentiation. Nature 408:106-111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McKinsey, T. A., C. L. Zhang, and E. N. Olson. 2000. Activation of the myocyte enhancer factor-2 transcription factor by calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase-stimulated binding of 14-3-3 to histone deacetylase 5. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:14400-14405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McKinsey, T. A., C. L. Zhang, and E. N. Olson. 2001. Control of muscle development by dueling HATs and HDACs. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 11:497-504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McKinsey, T. A., C. L. Zhang, and E. N. Olson. 2001. Identification of a signal-responsive nuclear export sequence in class II histone deacetylases. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21:6312-6321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McKinsey, T. A., C. L. Zhang, and E. N. Olson. 2002. MEF2: a calcium-dependent regulator of cell division, differentiation and death. Trends Biochem. Sci. 27:40-47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mermoud, J. E., B. Popova, A. H. Peters, T. Jenuwein, and N. Brockdorff. 2002. Histone H3 lysine 9 methylation occurs rapidly at the onset of random X chromosome inactivation. Curr. Biol. 12:247-251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miska, E. A., C. Karlsson, E. Langley, S. J. Nielsen, J. Pines, and T. Kouzarides. 1999. HDAC4 deacetylase associates with and represses the MEF2 transcription factor. EMBO J. 18:5099-5107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Murzina, N., A. Verreault, E. Laue, and B. Stillman. 1999. Heterochromatin dynamics in mouse cells: interaction between chromatin assembly factor 1 and HP1 proteins. Mol. Cell 4:529-540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nakayama, J., J. C. Rice, B. D. Strahl, C. D. Allis, and S. I. Grewal. 2001. Role of histone H3 lysine 9 methylation in epigenetic control of heterochromatin assembly. Science 292:110-113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ng, H. H., and A. Bird. 2000. Histone deacetylases: silencers for hire. Trends Biochem. Sci. 25:121-126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nielsen, A. L., J. A. Ortiz, J. You, M. Oulad-Abdelghani, R. Khechumian, A. Gansmuller, P. Chambon, and R. Losson. 1999. Interaction with members of the heterochromatin protein 1 (HP1) family and histone deacetylation are differentially involved in transcriptional silencing by members of the TIF1 family. EMBO J. 18:6385-6395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nielsen, A. L., M. Oulad-Abdelghani, J. A. Ortiz, E. Remboutsika, P. Chambon, and R. Losson. 2001. Heterochromatin formation in mammalian cells: interaction between histones and HP1 proteins. Mol. Cell 7:729-739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Owen, D. J., P. Ornaghi, J. C. Yang, N. Lowe, P. R. Evans, P. Ballario, D. Neuhaus, P. Filetici, and A. A. Travers. 2000. The structural basis for the recognition of acetylated histone H4 by the bromodomain of histone acetyltransferase gcn5p. EMBO J. 19:6141-6149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Peters, A. H., J. E. Mermoud, D. O'Carroll, M. Pagani, D. Schweizer, N. Brockdorff, and T. Jenuwein. 2002. Histone H3 lysine 9 methylation is an epigenetic imprint of facultative heterochromatin. Nat. Genet. 30:77-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Peters, A. H., D. O'Carroll, H. Scherthan, K. Mechtler, S. Sauer, C. Schofer, K. Weipoltshammer, M. Pagani, M. Lachner, A. Kohlmaier, S. Opravil, M. Doyle, M. Sibilia, and T. Jenuwein. 2001. Loss of the Suv39h histone methyltransferases impairs mammalian heterochromatin and genome stability. Cell 107:323-337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rea, S., F. Eisenhaber, D. O'Carroll, B. D. Strahl, Z. W. Sun, M. Schmid, S. Opravil, K. Mechtler, C. P. Ponting, C. D. Allis, and T. Jenuwein. 2000. Regulation of chromatin structure by site-specific histone H3 methyltransferases. Nature 406:593-599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ryan, R. F., D. C. Schultz, K. Ayyanathan, P. B. Singh, J. R. Friedman, W. J. Fredericks, and F. J. Rauscher III. 1999. KAP-1 corepressor protein interacts and colocalizes with heterochromatic and euchromatic HP1 proteins: a potential role for Kruppel-associated box-zinc finger proteins in heterochromatin-mediated gene silencing. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19:4366-4378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schotta, G., A. Ebert, V. Krauss, A. Fischer, J. Hoffmann, S. Rea, T. Jenuwein, R. Dorn, and G. Reuter. 2002. Central role of Drosophila SU(VAR)3-9 in histone H3-K9 methylation and heterochromatic gene silencing. EMBO J. 21:1121-1131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Seeler, J. S., A. Marchio, D. Sitterlin, C. Transy, and A. Dejean. 1998. Interaction of SP100 with HP1 proteins: a link between the promyelocytic leukemia-associated nuclear bodies and the chromatin compartment. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:7316-7321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sparrow, D. B., E. A. Miska, E. Langley, S. Reynaud-Deonauth, S. Kotecha, N. Towers, G. Spohr, T. Kouzarides, and T. J. Mohun. 1999. MEF-2 function is modified by a novel co-repressor, MITR. EMBO J. 18:5085-5098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang, A. H., N. R. Bertos, M. Vezmar, N. Pelletier, M. Crosato, H. H. Heng, J. Th'ng, J. Han, and X. J. Yang. 1999. HDAC4, a human histone deacetylase related to yeast HDA1, is a transcriptional corepressor. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19:7816-7827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang, A. H., M. J. Kruhlak, J. Wu, N. R. Bertos, M. Vezmar, B. I. Posner, D. P. Bazett-Jones, and X. J. Yang. 2000. Regulation of histone deacetylase 4 by binding of 14-3-3 proteins. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:6904-6912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang, A. H., and X. J. Yang. 2001. Histone deacetylase 4 possesses intrinsic nuclear import and export signals. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21:5992-6005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Winston, F., and C. D. Allis. 1999. The bromodomain: a chromatin-targeting module? Nat. Struct. Biol. 6:601-604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ye, Q., I. Callebaut, A. Pezhman, J. C. Courvalin, and H. J. Worman. 1997. Domain-specific interactions of human HP1-type chromodomain proteins and inner nuclear membrane protein LBR. J. Biol. Chem. 272:14983-14989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang, C. L., T. A. McKinsey, J. R. Lu, and E. N. Olson. 2001. Association of COOH-terminal-binding protein (CtBP) and MEF2-interacting transcription repressor (MITR) contributes to transcriptional repression of the MEF2 transcription factor. J. Biol. Chem. 276:35-39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang, C. L., T. A. McKinsey, and E. N. Olson. 2001. The transcriptional corepressor MITR is a signal-responsive inhibitor of myogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:7354-7359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhou, X., P. A. Marks, R. A. Rifkind, and V. M. Richon. 2001. Cloning and characterization of a histone deacetylase, HDAC9. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:10572-10577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhou, X., V. M. Richon, R. A. Rifkind, and P. A. Marks. 2000. Identification of a transcriptional repressor related to the noncatalytic domain of histone deacetylases 4 and 5. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:1056-1061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]