Wait lists have gained sharp prominence within the landscape of health care issues. Stories and statistics of how the common citizen has suffered and sometimes died while waiting for surgical and other medical procedures are legion, and they describe a failure of the health care system in a way that is easy to understand and that demands prompt and definitive attention.

However, there are also wait lists for public health services, and they rarely receive attention. These wait lists involve populations of citizens who have to wait (and sometimes die waiting) for clean water, adequate housing, safe transportation, and preventive and primary health care. For example, the wait times for sewage treatment facilities and potable water in some Northern Aboriginal communities run to 10 or more years, and there is no doubt that many people have suffered during that period.

Public health wait lists are real but hidden or ignored. Increasing their visibility is essential for making priorities for public health services more compelling for politicians and the public. In turn, wait lists in public health would allow us to assess and address the longstanding imbalance in resources for acute care and public health services.1

Wait lists for medical procedures have become the measure of choice to assess how the Canadian health care system is doing, whether health services are operating effectively and efficiently, and whether taxpayers are getting value for money. Yet, in a pivotal report, wait lists in Canada were described as “non-standardized, capriciously organized, and poorly monitored.”2 There were calls for major investments to improve management systems so that accurate and useful information can be delivered in a timely manner. Efforts to systematically document wait times across the acute care sector have grown.1,3–5 Wait lists for public health services ought to be included in these measurement systems and in public reports.

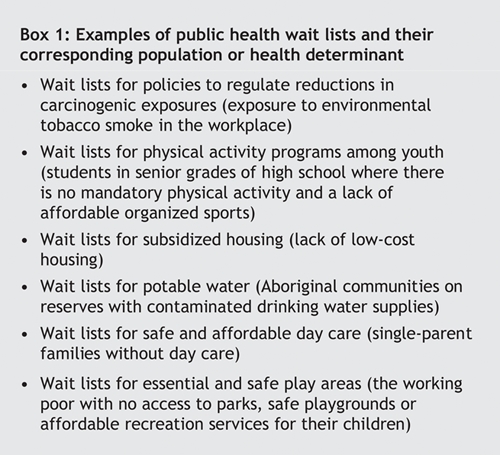

There are 2 fundamental questions regarding wait lists for public health services: What are they? And, if we do not make public health wait lists visible, what are the risks? Unlike wait lists in acute care, which predominantly describe the patient numerators (patients who are seeking care but are unable to obtain timely services), public health wait lists are about the denominators (populations that need services, whether or not individuals within the population are seeking those services). Public health wait lists also reflect the wide range of health determinants targeted and services delivered by the health protection and preventive health sector. Thus, many public health wait lists reflect the complex determinants of health experienced most forcefully by vulnerable populations. A noninclusive set of wait lists is shown in Box 1. We invite readers to add their own examples to this list.

Box 1.

In the absence of discussion of public health wait lists and the presence of much discussion of acute care wait lists, governments put available resources into acute care rather than investing in public health services. The risk, and we would argue it is considerable, of not having public health wait lists to bring to the resource allocation table is that public health will not be at the table.

Can wait lists for public health care services be measured?

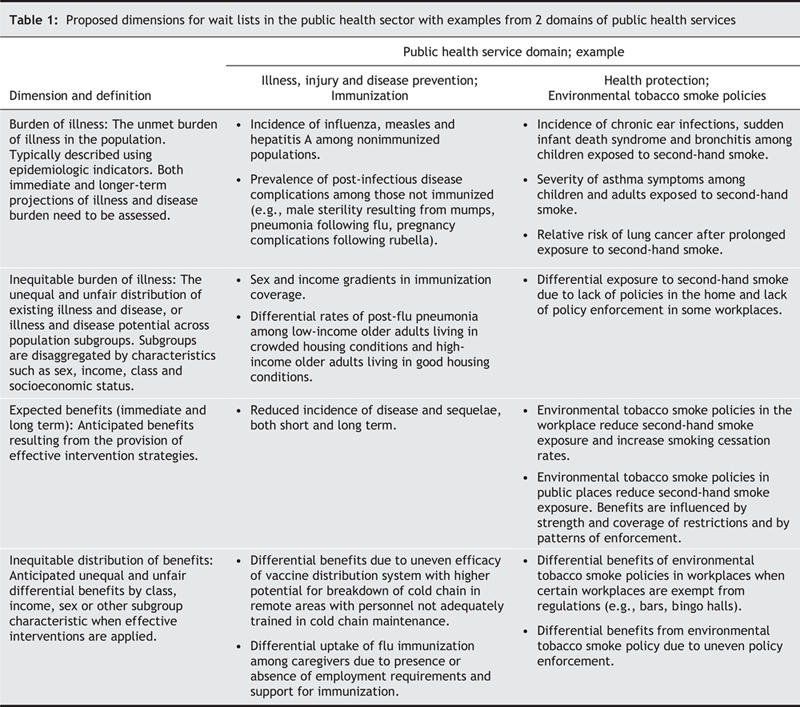

Hadorn and colleagues define wait lists as “a queue of patients who are deemed to need a health service that is in short supply relative to demand.”6 We can readily apply elements of this definition to public health. Public health is a health service; public health professionals work with communities and patients whom they refer to as clients; and the supply of public health services is often woefully insufficient to yield substantial population health gains.1 Thus, a definition of public health wait lists would be “individuals and groups in the community who are in need of illness, injury and disease prevention or health protection services that are in short supply relative to need.” In Table 1 we suggest 4 dimensions for public health wait lists, using prevention and protection as 2 domains of public health services. Again, we invite readers to provide their input on these ideas.

Table 1

Although wait lists may not be the most accurate platform for presenting the problems pervasive among the populations that require public health services, they are a means to make unmet and inequitable population health needs visible and prominent. The public health wait lists of today are the acute care wait lists of tomorrow. Ignoring wait lists for public health services fails the vulnerable population in the short term and the whole population in the long term. It would be naive to believe that public health wait lists alone will create the conditions sufficient for a more balanced approach to health care resource allocation. Nevertheless, developing a wait-list metric for use across both acute care and public health sectors would allow for better-informed decisions about that allocation. Perhaps most importantly, wait lists in public health would remind all of us that a primary goal of our health care system is to prevent illness and injury, and not just to treat the queue of patients requiring medical care.

Acknowledgments

Manuscript preparation was supported by a personnel award to Barbara Riley from the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada and the Institute of Circulatory and Respiratory Health, Canadian Institutes of Health Research, and by a Nursing Chair to Nancy Edwards funded by the Canadian Health Services Research Foundation, Canadian Institutes of Health Research, and the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-term Care.

Footnotes

Contributors: Both authors contributed substantially to the conceptualization of the ideas in this article, wrote and revised the article critically for important intellectual content and approved the final version.

Competing interests: None declared.

Correspondence to: Dr. Nancy C. Edwards, University of Ottawa, School of Nursing, 451 — 1118 Smyth Rd., Ottawa ON K1H 8M5; fax 613 562-5658; nancy.edwards@uottawa.ca

REFERENCES

- 1.Bennett J. Investment in population health in five OECD countries. OECD Health Working Paper #2. Paris: Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development; 2003.

- 2.McDonald P, Shortt S, Sanmartin C, et al. Waiting lists and waiting times for health care in Canada: more management!! More Money?? Ottawa: Health Canada; 1998.

- 3.Tu JV, Shortt S, McColgan P, et al. Reflections and recommendations. In: Tu JV, Pinfold SP, McColgan P, Laupacis A, editors. Access to health services in Ontario. ICES Atlas. Toronto: Institute for Clinical Evaluation Sciences; 2005.

- 4.Western Canada Waiting List Project. Moving forward (Final report). Calgary: The Project; 2004. p. 1-47.

- 5.Van Doorslaer E, Masseria C. Income-related inequality in the use of medical care in 21 OECD countries. OECD Health Working Paper #14. Paris: Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development; 2004.

- 6.Hadorn DC and the Steering Committee of the Western Canada Waiting List Project. Setting priorities for waiting lists: defining our terms. CMAJ 2000;163(7):857-60. [PMC free article] [PubMed]