Abstract

Malassezia species are considered to be one of the exacerbating factors in atopic dermatitis (AD). During examination of the cutaneous colonization of Malassezia species in AD patients, we found a new species on the surface of the patients' skin. Analysis of ribosomal DNA sequences suggested that the isolates belonged to the genus Malassezia. They did not grow in Sabouraud dextrose agar but utilized specific concentrations of Tween 20, 40, 60, and 80 as a lipid source. Thus, we concluded that our isolates were new members of the genus Malassezia and propose the name Malassezia dermatis sp. nov. for these isolates.

Malassezia species are known causative factors in pityriasis versicolor, seborrheic dermatitis (SD), and atopic dermatitis (AD) (3). In the last decade, research has focused primarily on isolating Malassezia strains and detecting specific immunoglobulin E (IgE) antibodies from patients (9, 13, 14, 26). A comparison of the isolation rates of Malassezia species from the skin of AD patients and healthy control subjects detected a significantly higher rate for patients than for healthy subjects (8). AD patients had specific IgE antibodies against Malassezia, while healthy subjects did not. In recent years, studies have increasingly been directed towards analyzing how the cutaneous microflora at the species level are related to each disease type (pityriasis versicolor, SD, and AD) (1, 6, 7, 12, 16). We previously compared the distribution of Malassezia species in skin lesions of AD patients and in healthy subjects using a nonculture method (nested PCR) that is not affected by the isolating medium (21). Of the seven members of the genus Malassezia, Malassezia globosa and M. restricta were the species most commonly associated with AD, while M. obtusa and M. pachydermatis were not detected in AD. In our survey of cutaneous Malassezia microflora, we isolated new Malassezia species from several patients with AD. In this paper, we propose a new species, M. dermatis, for these isolates.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Malassezia isolates.

Nineteen AD outpatients at Juntendo University Hospital were included in the study. To obtain samples, OpSite transparent dressings (3 by 7 cm; Smith and Nephew Medical Ltd., Hull, United Kingdom) were applied to skin lesions (erosive, erythematous, and lichenoid) on the scalp, back, and nape of the neck of AD patients. Samples were then transferred onto Leeming and Notman agar (LNA) (10.0 g of polypeptone, 5.0 g of glucose, 0.1 g of yeast extract, 8.0 g of ox gall, 1.0 mg of glycerol, 0.5 g of glycerol stearate, 0.5 mg of Tween 60, 10 ml of cow's milk [whole fat], and 12.0 g of agar per liter) plates containing 50 μl of chloramphenicol (Sankyo, Tokyo, Japan) and incubated at 32°C for 2 weeks.

Direct DNA sequencing of rRNA genes of the isolates.

Yeast isolates recovered from LNA medium were identified by analysis of rRNA gene sequences. Nuclear DNA of the isolates was extracted by the method of Makimura et al. (15). The D1 and D2 regions of 26S ribosomal DNA (rDNA) and internal transcribed spacer (ITS) regions in the rRNA gene were sequenced directly from PCR products using the primer pairs NL-1 (forward; GCATATCAATAAGCGGAGGAAAAG) and NL-4 (reverse; GGTCCGTGTTTCAAGACGG) (11) and pITS-F (forward; GTCGTAACAAGGTTAACCTGCGG) and pITS-R (reverse; TCCTCCGCTTATTGATATGC) (22), respectively. The PCR products were sequenced using an ABI 310 DNA sequencer and an ABI PRISM BigDye Terminator Cycle Sequencing kit (Perkin-Elmer Applied Biosystems, Foster, Calif.) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Strains with 99% or more similarity of the D1 and D2 regions of 26S rDNA and the overall ITS sequences were defined as conspecific (18, 22). The sequence data were searched using the BLAST system (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST/) at the National Center for Biotechnology Information, Bethesda, Md.

Molecular phylogenetic analysis.

The sequences were aligned using ClustalW software (25). For neighbor-joining analysis (20), the distances between sequences were calculated using Kimura's two-parameter model (10). A bootstrap analysis was conducted with 100 replications (2).

Morphological, physiological, and chemotaxonomic characteristics.

Morphology was examined on LNA after incubation at 32°C for 7 days. Tween 20, 40, 60, and 80 utilization, catalase reactions, and diazonium blue B reactions were performed as described by Guého et al. (4). Identification of ubiquinone was carried out using methods described by Nakase and Suzuki (17). The nuclear DNA base composition (moles percent G+C) was determined by high-pressure liquid chromatography after enzymatic digestion of DNA into deoxyribonucleosides (23, 24). The DNA-GC kit (Yamasa Shouyu, Chiba, Japan) was used according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The nucleotide sequences determined in this study have been deposited with DDBJ (DNA Data Bank of Japan) under the accession numbers shown in Fig. 1.

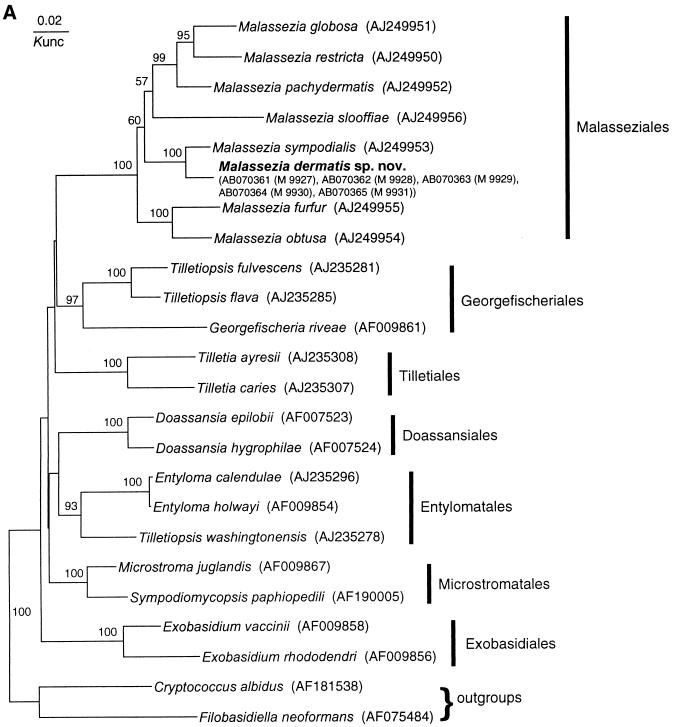

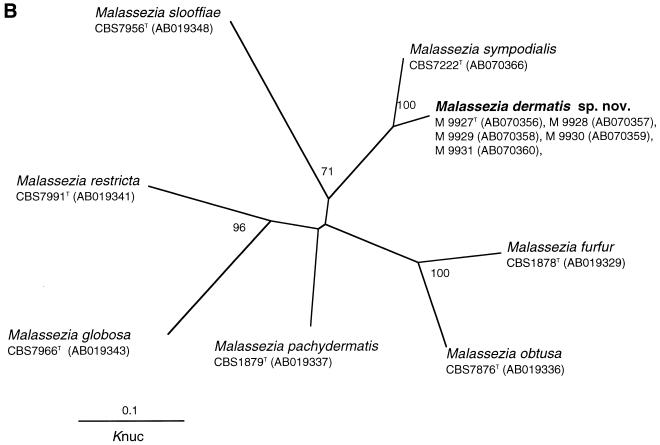

FIG. 1.

Molecular phylogenetic trees constructed using the sequences of D1 and D2 26S rDNA of M. dermatis sp. nov. and related Ustilaginomycetes species (A) and the ITS1 region of M. dermatis sp. nov. and other member of the genus Malassezia (B). DDBJ/GenBank accession numbers are indicated in parentheses. The numerals represent the confidence levels from 100 replicate bootstrap samplings (frequencies of less than 50% are not indicated). T, type strain. Knuc, Kimura's parameter (10).

RESULTS

Molecular phylogenetic analysis.

All of the yeast isolates obtained from the 19 AD patients were identified by analysis of rRNA gene sequences (D1 and D2 regions of 26S rDNA and ITS). Of these, the DNA sequences of five isolates did not match sequences in the DNA sequence database. These isolates were designated M 9927, M 9928, M 9929, M 9930, and M 9931. The first three strains were isolated from a single patient, while the last two strains were isolated from one patient each. Sequence analysis of their 26S rDNA indicated that these isolates belonged to the genus Malassezia (Fig. 1A). The sequences of five isolates were completely identical in both the 26S rDNA and ITS regions and clustered with M. sympodialis with high bootstrap values (100%) (Fig. 1). Dissimilarities between these isolates and the M. sympodialis strain in their D1 and D2 regions of 26S, ITS1, and ITS2 were 1.2% (7 of 578), 10.5% (17 of 162), and 10.3% (24 of 233), respectively. The overall dissimilarity of ITS regions was 10.4% (41 of 395).

Taxonomic characteristics.

The characteristics that differentiate the new species, M. dermatis, from the other seven known Malassezia species are summarized in Table 1. The physiological characteristics of M. dermatis are identical to those of M. furfur. However, the moles percent G+C of M. dermatis nuclear DNA is 60.4% while that of M. furfur is 66.0 to 66.7%. A difference of more than 1 mol% G+C between two strains is considered taxonomically significant (19, 24).

TABLE 1.

Taxonomic characteristics of M. dermatis and other Malassezia species

| Characteristic | M. dermatis sp. nov. | M. furfura | M. pachydermatisa | M. sympodialisa | M. globosaa | M. obtusaa | M. restrictaa | M. slooffiaea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Morphological characteristics | ||||||||

| Colony morphology | Convex, butyrous, entire or lobed magin | Mat, dull, smooth, umbonate or slightly folded with convex elevation | Mat, convex, umbonate (sometimes) | Glistening, smooth, flat or with a slight central elevation | Raised, folded, rough | Smooth, flat | Dull, smooth to rough at the edges | Rough but usually with fine grooves |

| Cell shape (size [μm]) | Spherical, oval, ellipsoidal (2.0-8.0 by 2.0-10.0) | Oval, cylindrical (1.5-3.0 by 2.5-8.0), spherical (2.5-5.0) | Oval (2.0-2.5 by 4.0-5.0) | Oval, globosal (1.5-2.5 by 2.5-6.0) | Spherical (2.5-8.0) | Cylindrical (1.5-2.0 by 4.0-6.0) | Spherical, oval (1.5-2.0 by 2.5-4.0) | Short cylindrical (1.0-2.0 by 1.5-4.0) |

| Physiological characteristicsb | ||||||||

| Growth on Sa at 32°C | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − |

| Growth on mDixon | ||||||||

| 32°C | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| 37°C | + | + | + | + | ± or − | ± or + | + | + |

| 40°C | + | + | + | + | − | − | − | + |

| Catalase reaction | + | + | ± or + | + | + | + | − | + |

| Utilization of: | ||||||||

| Tween 20 | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | ± or + |

| Tween 40 | + | + | + | + | − | − | − | + |

| Tween 60 | + | + | + | + | − | − | − | + |

| Tween 80 | + | + | + | + | − | − | − | − |

| Mol% G+C | 60.4 | 66.0-66.7 | 55.5-56.0 | 61.9-62.5 | 53.5-53.7 | 60.5-60.7 | 59.8-60.0 | 68.5-69.0 |

Data are from the work of Gúeho et al. (4).

Sa, Sabouraud dextrose agar; mDixon, modified Dixon agar; +, positive; −, negative; ±, weakly positive.

Latin description of Malassezia dermatis Sugita, Takashima, Nishikawa et Shinoda sp. nov.

In LNA, post dies 7 ad 32°C, cellulae vegetativae sphaericae, ovoideae vel ellipsoideae (2-8) × (2-10) μm. Cultura xanthoalba, semi-nitida aut hebetata, butyracea et margo glabra aut lobulata. In agaro glucoso-peptonico Tween 20, 40, 60, 80 (0.1-1%) addito crecit. H2O2 hydrolysatur. Commutatio colori per diazonium caeruleum B positiva. Proportio molaris guanini+cytosini in acido deoxyribonucleico: 60.4 mol%. Ubiquinonum majus: Q-9. Telemorphis ignota. Typus: JCM 11348T, ex cute morbosa, Tokyo, Japonia, 30.9.1999, T. Sugita (originaliter ut M 9927), conservatur in collectionibus culturarum quas ‘Japan Collection of Microorganisms,’ Saitama, Japan sustentat.

Description of M. dermatis Sugita, Takashima, Nishikawa et Shinoda sp. nov.

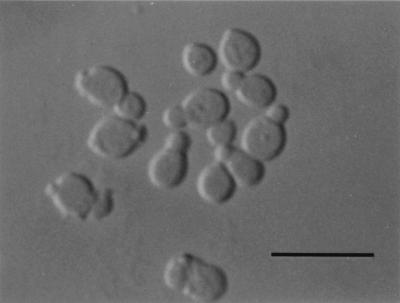

After 7 days on LNA at 32°C, the vegetative cells were spherical, oval, or ellipsoidal (2 to 8 by 2 to 10 μm), and they reproduced by budding (Fig. 2). The colony was yellowish white, semishiny to dull, convex, and butyrous and had an entire or lobed margin. Filaments sometimes formed at the area of the origin of the bud. Growth was seen on glucose-peptone agar with either 0.1, 0.5, 1.0, 5.0, or 10% Tween 20, 40, 60, or 80 as sole source of lipid. Catalase reaction was positive. The diazonium blue B reaction was positive. The G+C content of nuclear DNA was 60.4 mol%, and the major ubiquinone was Q-9. Teleomorph is unknown. JCM 11348T (originally M 9927) isolated from skin lesions of an AD patient in Tokyo, Japan, by T. Sugita on 30 September 1999 is maintained in the Japan Collection of Microorganisms (JCM), Saitama, Japan. The other strains, M 9929 and M 9931 have also been deposited in the JCM, as JCM 11469 and JCM 11470, respectively. Etymology is from the Latin name for skin, from which this strain of the species was obtained.

FIG. 2.

Vegetative cells of M. dermatis M 9927 (JCM 11348) grown in LNA for 7 days at 32°C. Bar, 10 μm.

DISCUSSION

The genus Malassezia is phylogenetically monophyletic with a high bootstrap value (100%) and is positioned in the class Ustilaginomycetes (Fig. 1A). Our isolates clustered with M. sympodialis on the tree. We did not perform a nuclear DNA-DNA hybridization study between M. sympodialis and our isolates, but sequence analysis of rDNA (26S and ITS) strongly suggests that our five isolates represent a new species in the genus Malassezia. At present, D1 and D2 26S rDNA sequences are used from almost all yeasts for species identification or phylogenetic analysis. Peterson and Kurtzman (18) correlated the biological species concept with the phylogenetic species concept by the extent of nucleotide substitutions in 26S rDNA sequences. Their study demonstrated that strains of a single biological species show less than 1% substitution in this region. Subsequently, Sugita et al. (22) also found that conspecific strains have less than 1% dissimilarity in the ITS1 and -2 regions after comparing the nuclear DNA-DNA hybridization values and similarity in the sequences of the entire ITS1 and -2 regions. According to the species concept used in the two reports cited above, the divergence between M. sympodialis and our isolates is sufficient to resolve them as individual species. In addition, the approximately 1 mol% difference in the G+C content of nuclear DNA that was found between these two species also has taxonomic significance (19, 24). Guillot et al. (5) described a practical approach (combination of Tween utilization and catalase tests) for easy and simple identification of Malassezia species. Unfortunately, M. dermatis cannot be identified by this system, despite having similar characteristics to M. furfur. At present, sequence analysis of the D1 and D2 regions of the 26S rDNA or the ITS regions is the most reliable and simplest method for M. dermatis identification.

We previously demonstrated cutaneous Malassezia colonization in 32 AD patients by a nonculture method (nested PCR) and compared anti-Malassezia antibody levels with those in healthy subjects. The detection of M. globosa and M. restricta in more than 90% of AD patients suggested that these two species play an important role in AD. Since we were not aware of the existence of M. dermatis at that time, we did not detect the DNA of this species in our previous study. Although the present study examined a limited number of patients, M. dermatis was found in 3 of 19 patients. However, the degree of M. dermatis colonization of the skin surface in the AD patients was not as great as that of M. globosa and M. restricta.

In conclusion, we described a novel species, M. dermatis, isolated from skin lesions of AD patients. Further studies should examine whether this microorganism is responsible for AD or other skin diseases and whether it is specific to Japan.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by a Grant for the Promotion of the Advancement of Education and Research in Graduate Schools from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aspiroz, C., L. A. Moreno, A. Rezusta, and C. Rubio. 1999. Differentiation of three biotypes of Malassezia species on human normal skin. Correspondence with M. globosa, M. sympodialis and M. restricta. Mycopathologia 145:69-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Felsenstein, J. 1985. Confidence limits on phylogenies: an approach using the bootstrap. Evolution 39:783-791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guého, E., T. Boekhout, H. R. Ashbee, J. Guillot, A. van Belkum, and J. Faergemann. 1998. The role of Malassezia species in the ecology of human skin and as pathogens. Med. Mycol. 36(Suppl. 1):220-229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guého, E., G. Midgley, and J. Guillot. 1996. The genus Malassezia with description of four new species. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek 69:337-355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guillot, J., E. Guého, M. Lesourd, G. Midgley, G. Chevrier, and B. Dupont. 1996. Identification of Malassezia species. J. Mycol. Med. 6:103-110. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gupta, A. K., Y. Kohli, J. Faergemann, and R. C. Summerbell. 2001. Epidemiology of Malassezia yeasts associated with pityriasis versicolor in Ontario, Canada. Med. Mycol. 39:199-206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gupta, A. K., Y. Kohli, R. C. Summerbell, and J. Faergemann. 2001. Quantitative culture of Malassezia species from different body sites of individuals with or without dermatoses. Med. Mycol. 39:243-251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hiruma, M., D. J. Maeng, M. Kobayashi, H. Suto, and H. Ogawa. 1999. Fungi and atopic dermatitis. Jpn. J. Med. Mycol. 40:79-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim, T. Y., I. G. Jang, Y. M. Park, H. O. Kim, and C. W. Kim. 1999. Head and neck dermatitis: the role of Malassezia furfur, topical steroid use and environmental factors in its causation. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 24:226-231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kimura, M. 1980. A simple method for estimation evolutionary rate of base substitutions through comparative studies of nucleotide sequences. J. Mol. E 16:111-120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kurtzman, C. P., and C. J. Robnett. 1997. Identification of clinically important ascomycetous yeasts based on nucleotide divergence in the 5′ end of the large-subunit (26S) ribosomal DNA gene. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35:1216-1223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leeming, J. P., J. E. Sansom, and J. L. Burton. 1997. Susceptibility of Malassezia furfur subgroups to terbinafine. Br. J. Dermatol. 137:764-767. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leung, D. Y. 1995. Atopic dermatitis: the skin as a window into the pathogenesis of chronic allergic diseases. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 96:302-318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lintu, P., J. Savolainen, and K. Kalimo. 1997. IgE antibodies to protein and mannan antigens of Pityrosporum ovale in atopic dermatitis patients. Clin. Exp. Allergy 27:87-95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Makimura, K., Y. S. Murayama, and H. Yamaguchi. 1994. Detection of a wide range of medically important fungal species by polymerase chain reaction (PCR). J. Med. Microbiol. 40:358-364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nakabayashi, A., Y. Sei, and J. Guillot. 2000. Identification of Malassezia species isolated from patients with seborrhoeic dermatitis, atopic dermatitis, pityriasis versicolor and normal subjects. Med. Mycol. 38:337-341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nakase, T., and M. Suzuki. 1986. Bullera megalospora, a new species of yeast forming large ballistospores isolated from dead leaves of Oryza sativa, Miscanthus sinensis, and Sasa sp. in Japan. J. Gen. Appl. Microbiol. 32:225-240. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peterson, S. W., and C. P. Kurtzman. 1991. Ribosomal RNA sequence divergence among sibling species of yeasts. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 14:124-129. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Price, C. W., G. B. Fuson, and H. J. Phaff. 1978. Genome comparison in yeast systematics: delimitation of species within the genera Schwanniomyces, Saccharomyces, Debaryomyces, and Pichia. Microbiol. Rev. 42:161-193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saitou, N., and M. Nei. 1987. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol. Biol. E 4:406-425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sugita, T., H. Suto, T. Unno, R. Tsuboi, H. Ogawa, T. Shinoda, and A. Nishikawa. 2001. Molecular analysis of Malassezia microflora on the skin of atopic dermatitis patients and healthy subjects. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:3486-3490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sugita, T., A. Nishikawa, R. Ikeda, and T. Shinoda. 1999. Identification of medically relevant Trichosporon species based on sequences of internal transcribed spacer regions and construction of a database for Trichosporon identification. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:1985-1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Takashima, M., and T. Nakase. 2000. Four new species of the genus Sporobolomyces isolated from leaves in Thailand. Mycoscience 41:65-77. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tamaoka, J., and K. Komagata. 1984. Determination of DNA base composition by reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 25:125-128. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thompson, J. D., D. G. Higgins, and T. J. Gibson. 1994. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 22:4673-4680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wessels, M. W., G. Doekes, A. G. Van Ieperen-Van Kijk, W. J. Koers, and E. Young. 1991. IgE antibodies to Pityrosporum ovale in atopic dermatitis. Br. J. Dermatol. 125:227-232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]