Abstract

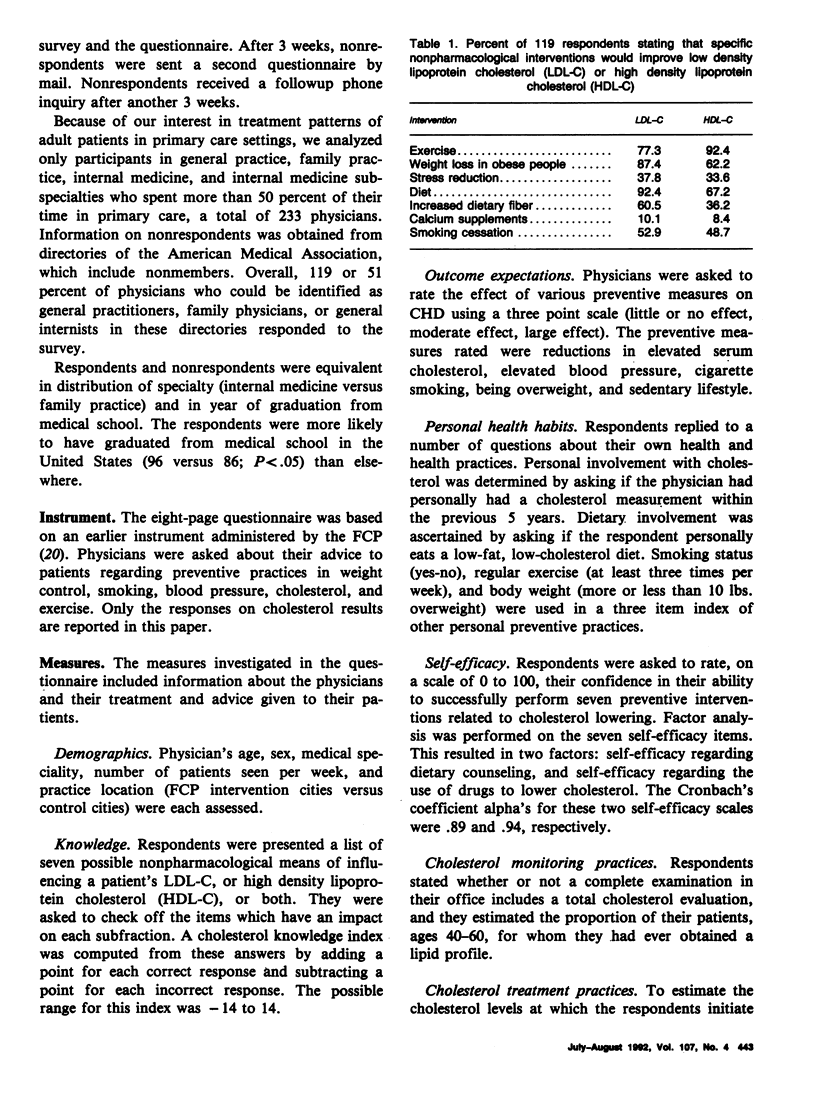

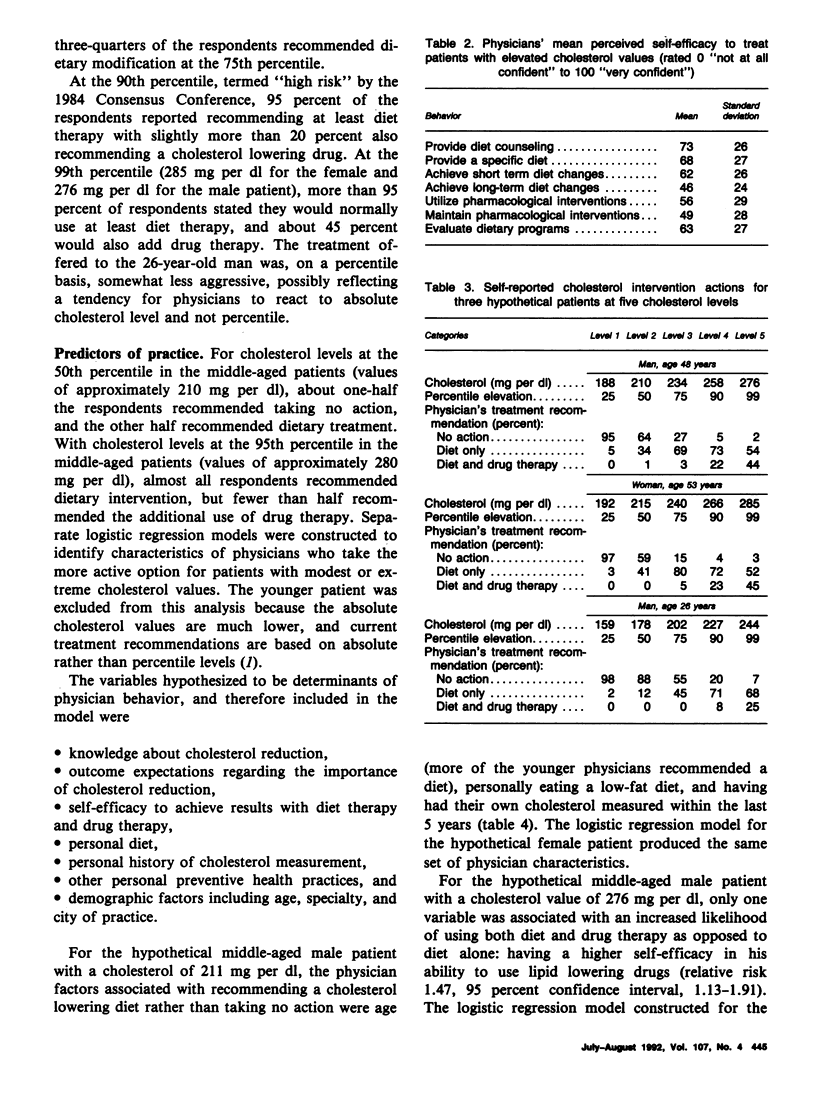

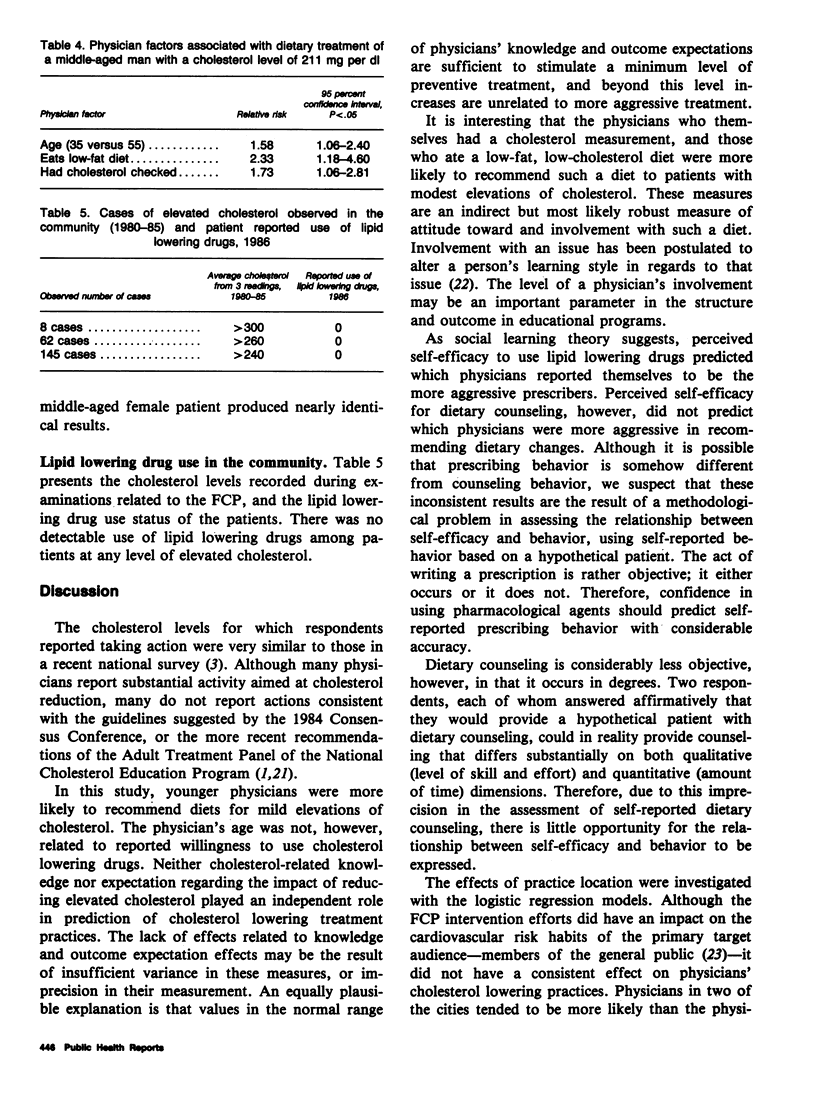

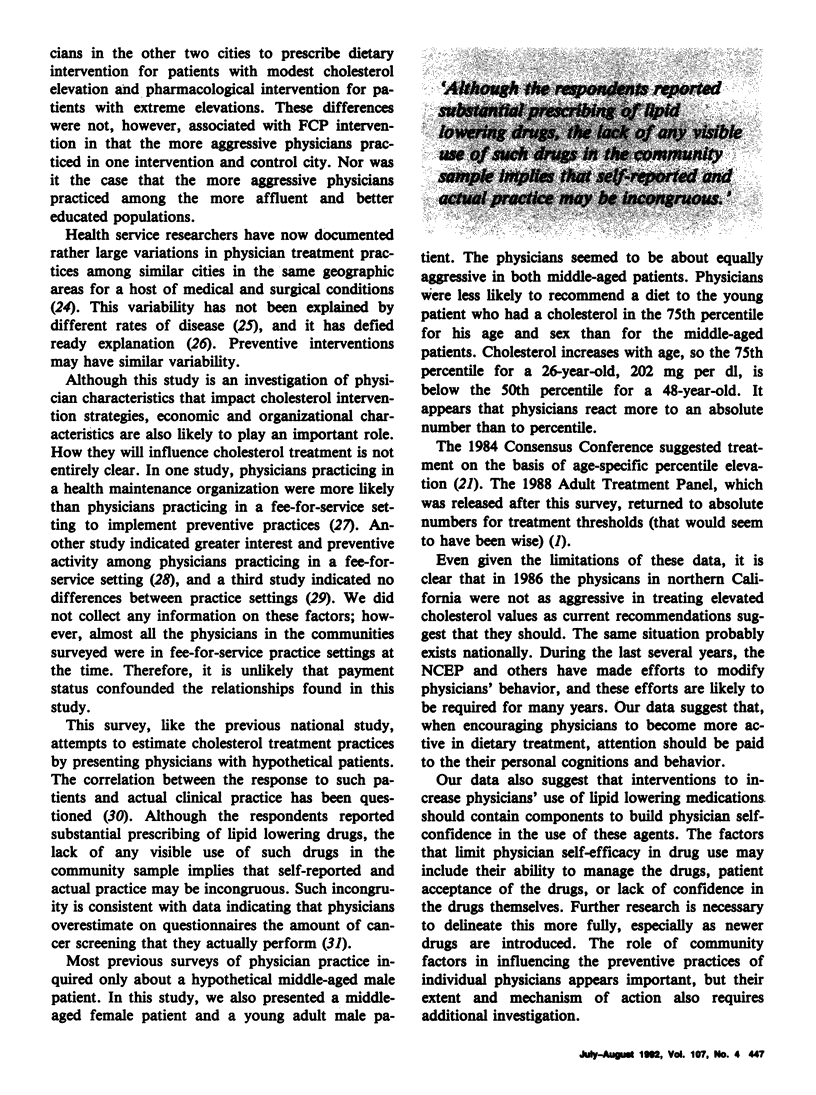

The active involvement of primary care physicians is necessary in the diagnosis and treatment of elevated blood cholesterol. Empirical evidence suggests that primary care physicians generally initiate dietary and pharmacological treatment at threshold values higher than is currently recommended. To determine current treatment thresholds and establish factors that distinguish physicians who are more likely to initiate therapy at lower cholesterol values, 119 primary care physicians in four northern California communities were surveyed. Data collection included their demographic factors, treatment of hypothetical patients, self-efficacy regarding counseling patients about cholesterol reduction and personal health behaviors, outcome expectations, and cholesterol knowledge and attitudes. Results indicated that 59 percent of respondents would not start dietary treatment on a middle-aged female patient with a cholesterol of 215 milligrams per deciliter (mg per dl). Only 44 percent of respondents indicated that they would initiate pharmacological therapy for a middle-aged man with a cholesterol of 276 mg per dl. Logistic regression models were used to determine characteristics that influenced dietary and pharmacological treatment practices. Younger physicians, those who had had their own cholesterol checked, and those who personally ate a low-fat diet, were more likely to recommend diet therapy to patients with modest elevations of cholesterol. Willingness to use lipid lowering medications at more marked elevations was associated only with increased self-efficacy regarding use of drugs to lower cholesterol. These results indicate that physicians' personal health behaviors and self-efficacy should be addressed in interventions to modify cholesterol-related practice behavior.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Bernstein A. B., Thompson G. B., Harlan L. C. Differences in rates of cancer screening by usual source of medical care. Data from the 1987 National Health Interview Survey. Med Care. 1991 Mar;29(3):196–209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boekeloo B. O., Becker D. M., LeBailly A., Pearson T. A. Cholesterol management in patients hospitalized for coronary heart disease. Am J Prev Med. 1988 May-Jun;4(3):128–132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey T., Weis K., Homer C. Prepaid versus traditional Medicaid plans: effects on preventive health care. J Clin Epidemiol. 1990;43(11):1213–1220. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(90)90022-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson J. H. Practice variations: a challenge for physicians. JAMA. 1987 Nov 13;258(18):2570–2570. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farquhar J. W., Fortmann S. P., Flora J. A., Taylor C. B., Haskell W. L., Williams P. T., Maccoby N., Wood P. D. Effects of communitywide education on cardiovascular disease risk factors. The Stanford Five-City Project. JAMA. 1990 Jul 18;264(3):359–365. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farquhar J. W., Fortmann S. P., Maccoby N., Haskell W. L., Williams P. T., Flora J. A., Taylor C. B., Brown B. W., Jr, Solomon D. S., Hulley S. B. The Stanford Five-City Project: design and methods. Am J Epidemiol. 1985 Aug;122(2):323–334. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortmann S. P., Sallis J. F., Magnus P. M., Farquhar J. W. Attitudes and practices of physicians regarding hypertension and smoking: The Stanford Five City Project. Prev Med. 1985 Jan;14(1):70–80. doi: 10.1016/0091-7435(85)90022-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gemson D. H., Colombotos J., Elinson J., Fordyce E. J., Hynes M., Stoneburner R. Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome prevention. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices of primary care physicians. Arch Intern Med. 1991 Jun;151(6):1102–1108. doi: 10.1001/archinte.151.6.1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haynes R. B., Davis D. A., McKibbon A., Tugwell P. A critical appraisal of the efficacy of continuing medical education. JAMA. 1984 Jan 6;251(1):61–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes M. M., Rovner D. R., Rothert M. L., Schmitt N., Given C. W., Ialongo N. S. Methods of analyzing physician practice patterns in hypertension. Med Care. 1989 Jan;27(1):59–68. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198901000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosecoff J., Kanouse D. E., Rogers W. H., McCloskey L., Winslow C. M., Brook R. H. Effects of the National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Program on physician practice. JAMA. 1987 Nov 20;258(19):2708–2713. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenfant C. A new challenge for America: the National Cholesterol Education Program. Circulation. 1986 May;73(5):855–856. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.73.5.855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis C. E., Clancy C., Leake B., Schwartz J. S. The counseling practices of internists. Ann Intern Med. 1991 Jan 1;114(1):54–58. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-114-1-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis C. E., Wells K. B., Ware J. A model for predicting the counseling practices of physicians. J Gen Intern Med. 1986 Jan-Feb;1(1):14–19. doi: 10.1007/BF02596319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McPhee S. J., Richard R. J., Solkowitz S. N. Performance of cancer screening in a university general internal medicine practice: comparison with the 1980 American Cancer Society Guidelines. J Gen Intern Med. 1986 Sep-Oct;1(5):275–281. doi: 10.1007/BF02596202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McPhee S. J., Schroeder S. A. Promoting preventive care: changing reimbursement is not enough. Am J Public Health. 1987 Jul;77(7):780–781. doi: 10.2105/ajph.77.7.780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otradovec K., Blake R. L., Jr, Parker B. M. An assessment of the practice of preventive cardiology in an academic health center. J Fam Pract. 1985 Aug;21(2):125–129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rimer B. K., Trock B., Balshem A., Engstrom P. F., Rosan J., Lerman C. Breast screening practices among primary physicians: reality and potential. J Am Board Fam Pract. 1990 Jan-Mar;3(1):26–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schucker B., Wittes J. T., Cutler J. A., Bailey K., Mackintosh D. R., Gordon D. J., Haines C. M., Mattson M. E., Goor R. S., Rifkind B. M. Change in physician perspective on cholesterol and heart disease. Results from two national surveys. JAMA. 1987 Dec 25;258(24):3521–3526. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scutchfield F. D., de Moor C. Preventive attitudes, beliefs, and practices of physicians in fee-for-service and health maintenance organization settings. West J Med. 1989 Feb;150(2):221–225. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valente C. M., Sobal J., Muncie H. L., Jr, Levine D. M., Antlitz A. M. Health promotion: physicians' beliefs, attitudes, and practices. Am J Prev Med. 1986 Mar-Apr;2(2):82–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler H., Levine S., Idelson R. K., Rohman M., Taylor J. O. The physician's role in health promotion--a survey of primary-care practitioners. N Engl J Med. 1983 Jan 13;308(2):97–100. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198301133080211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells K. B., Lewis C. E., Leake B., Ware J. E., Jr Do physicians preach what they practice? A study of physicians' health habits and counseling practices. JAMA. 1984 Nov 23;252(20):2846–2848. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wennberg J. E. Population illness rates do not explain population hospitalization rates. A comment on Mark Blumberg's thesis that morbidity adjusters are needed to interpret small area variations. Med Care. 1987 Apr;25(4):354–359. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]