Abstract

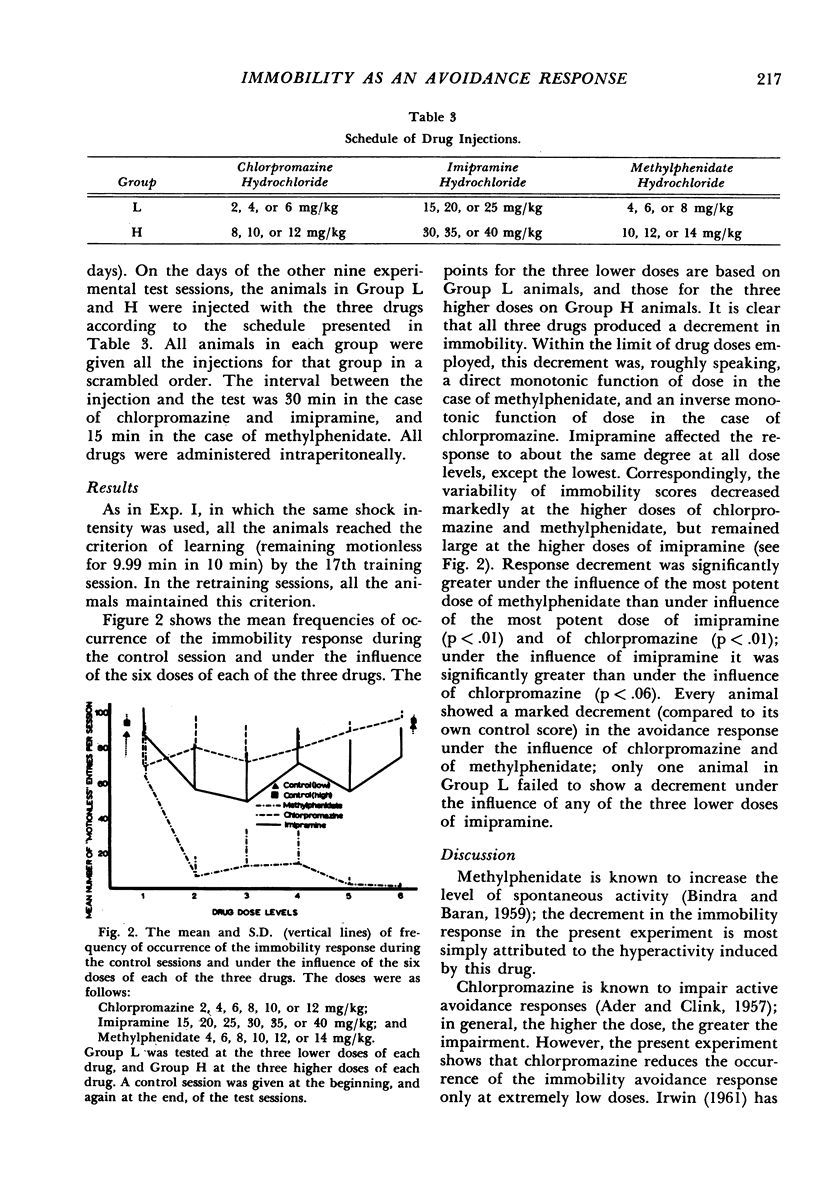

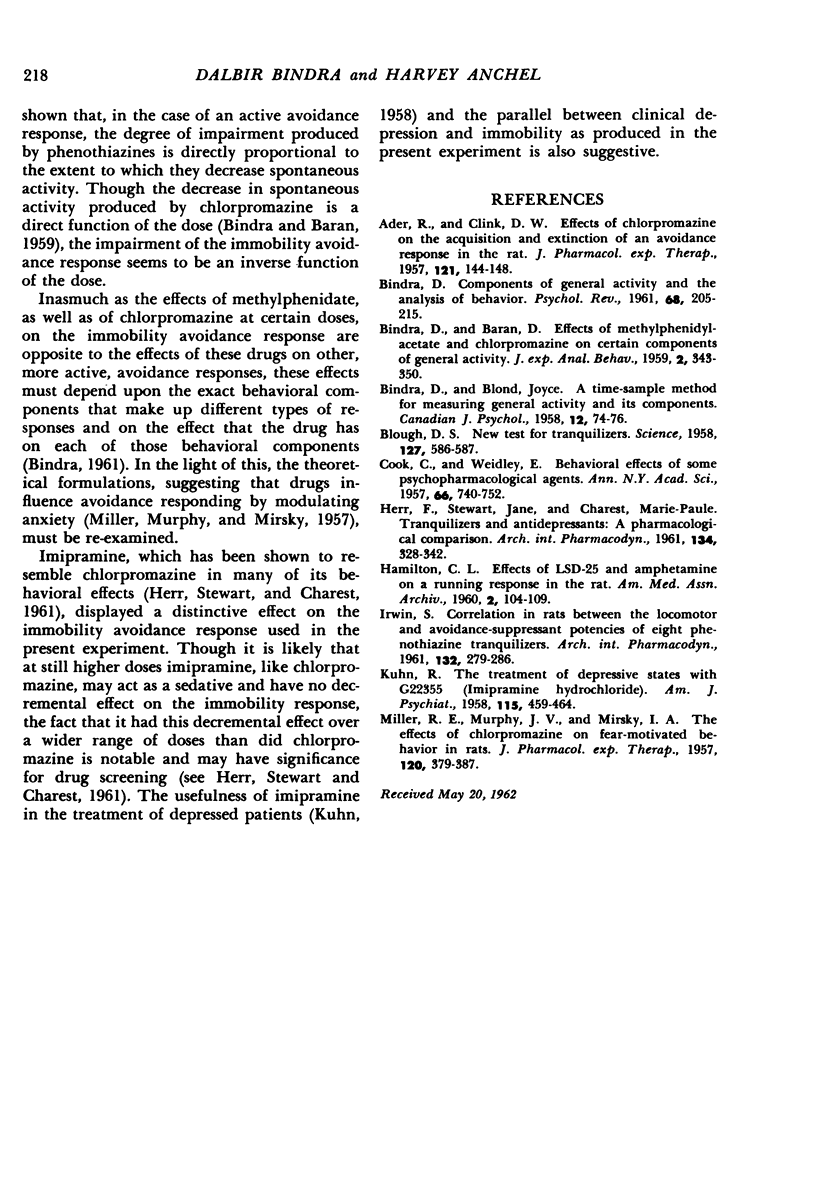

Much of the available literature on avoidance behavior is based on responses which require the animal to run, lever-press, or to make some active response to avoid noxious stimulation. The purpose of Experiment I reported in this paper was to determine whether animals can learn to sit or stand motionless in order to escape or avoid electric shock. Five experimental rats were given escape-avoidance training, while five yoked control animals received electric shocks without any response-related contingency. It was shown that an immobility avoidance response, as distinct from the unconditioned “freezing” response to shock, can be trained. The results of Experiment II (30 rats) revealed that this response is more readily acquired at higher shock intensities than at lower ones, provided escape by jumping is prevented at the high shock intensities. The effects of six doses of each of three drugs on the immobility avoidance response were studied in Experiment III (13 rats). Methylphenidate, chlorpromazine, and imipramine all produced a decrement in the immobility response, but the pattern and amount of the effects of the three drugs were quite different, one from the other. The implications of these findings for a general theory of avoidance behavior and for drug screening are discussed.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- ADER R., CLINK D. W. Effects of chlorpromazine on the acquisition and extinction of an avoidance response in the rat. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1957 Sep;121(1):144–148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BINDRA D., BARAN D. Effects of methylphenidylacetate and chlorpromazine on certain components of general activity. J Exp Anal Behav. 1959 Oct;2:343–350. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1959.2-343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BINDRA D., BLOND J. A time-sample method for measuring general activity and its components. Can J Psychol. 1958 Jun;12(2):74–76. doi: 10.1037/h0083729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BLOUGH D. S. New test for tranquilizers. Science. 1958 Mar 14;127(3298):586–587. doi: 10.1126/science.127.3298.586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COOK L., WEIDLEY E. Behavioral effects of some psychopharmacological agents. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1957 Mar 14;66(3):740–752. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1957.tb40763.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HAMILTON C. L. Effects of LSD-25 and amphetamine on a running response in the rat. AMA Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1960 Jan;2:104–109. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1960.03590070106013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HERR F., STEWART J., CHAREST M. P. Tranquilizers and antidepressants: a pharmacological comparison. Arch Int Pharmacodyn Ther. 1961 Dec 1;134:328–342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IRWIN S. Correlation in rats between the locomotor and avoidance suppressant potencies of eight phenothiazine tranquilizers. Arch Int Pharmacodyn Ther. 1961 Jul 1;132:279–286. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KUHN R. The treatment of depressive states with G 22355 (imipramine hydrochloride). Am J Psychiatry. 1958 Nov;115(5):459–464. doi: 10.1176/ajp.115.5.459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MILLER R. E., MURPHY J. V., MIRSKY I. A. The effect of chlorpromazine on fear-motivated behavior in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1957 Jul;120(3):379–387. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]