Abstract

Marker rescue, the restoration of gene function by replacement of a defective gene with a normal one by recombination, has been utilized to produce novel adeno-associated virus (AAV) vectors. AAV serotype 2 (AAV2) clones containing wild-type terminal repeats, an intact rep gene, and a mutated cap gene, served as the template for marker rescue. When transfected alone in 293 cells, these AAV2 mutant plasmids produced noninfectious AAV virions that could not bind heparin sulfate after infection with adenovirus dl309 helper virus. However, the mutation in the cap gene was corrected after cotransfection with AAV serotype 3 (AAV3) capsid DNA fragments, resulting in the production of AAV2/AAV3 chimeric viruses. The cap genes from several independent marker rescue experiments were PCR amplified, cloned, and then sequenced. Sequencing results confirmed not only that homologous recombination occurred but, more importantly, that a mixed population of AAV chimeras carrying 16 to 2,200 bp throughout different regions of the type 3 cap gene were generated in a single marker rescue experiment. A 100% correlation was observed between infectivity and the ability of the chimeric virus to bind heparin sulfate. In addition, many of the AAV2/AAV3 chimeras examined exhibited differences at both the nucleotide and amino acid levels, suggesting that these chimeras may also exhibit unique infectious properties. Furthermore, AAV helper plasmids containing these chimeric cap genes were able to function in the triple transfection method to generate recombinant AAV. Together, the results suggest that DNA from other AAV serotypes can rescue AAV capsid mutants and that marker rescue may be a powerful, yet simple, technique to map, as well as develop, chimeric AAV capsids that display different serotype-specific properties.

Adeno-associated viruses (AAVs), members of the family Parvoviridae and the genus Dependovirus, are small, nonenveloped, single-stranded DNA viruses (reviewed in references 7 and 25). Distinct serotypes of AAV have been identified from human and nonhuman primates, but only AAV serotype 2 (AAV2) has been extensively characterized and utilized in gene therapy applications (5, 10-12, 14, 19, 24, 26, 29, 32, 33, 38, 47). Several properties of AAV2 make it a desirable gene delivery system. Importantly, AAV2 has never been associated with human disease, is considered nonpathogenic, and transgenes expressed from AAV2 vectors do not elicit a cell-mediated immune response (7, 14, 18, 48). Recombinant AAV2-based vectors produce long-term expression in the brains, livers, muscles, and retinas of experimental animals (14, 21, 26, 48).

The AAV capsid is composed of three structural proteins (VP1, VP2, and VP3), which are related to each other in that they are generated from a single open reading frame (cap) utilizing different start codons to express VP2 and 3 and an alternative splice for VP1. VP3 is the smallest and the most abundant capsid protein (80%), whereas the remaining proteins, VP1 and VP2, are present in minor amounts (10% each) (25). The structure of the capsids of several parvoviruses, including human parvovirus B19, canine parvovirus, feline panleukemia virus, Galleria mellonella densovirus (an insect parvovirus), Aleutian mink disease parvovirus, and minute virus of mice, as well as the newly published structure for AAV2 is now solved (1-3, 22, 37, 41, 50). The capsids of these parvoviruses consist of 60 subunits; the smallest capsid protein makes up the majority of the virion. These proteins have the β-barrel motif formed by eight β strands and have four prominent looped-out regions. These looped-out regions constitute the majority of the differences between the viruses, are exposed regions on the capsid surface, and determine the biological properties of the virus such as tissue tropism, antigenicity, host range, and binding to cellular receptors (8, 23).

A major limitation on the use of AAV2 is that it can infect cells from a variety of tissues and organs (7, 25). The generation of AAV2 vectors that can selectively infect particular cells would be advantageous to gene therapy protocols. Understanding of viral entry and binding to the cell is only known for a few of the serotypes. The primary cellular receptor for AAV2 is heparan sulfate proteoglycan (HSP), a molecule found on many cell types, which explains the broad tropism of AAV2 (40). Subsequent analyses have determined that the coreceptors for this virus are αVβ5 integrin or human fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 (27, 39). Recently, it has been established that some AAV serotypes utilize receptors different from AAV2. Serotypes 4 and 5 utilize sialic acid for efficient transduction but differ in sialic acid linkage specificity, which probably reflects that their tissue tropism is distinct from AAV2 and each other (12, 13, 19, 43, 52). AAV1's primary cellular receptor is unknown but AAV1 transduces muscle cells more efficiently than AAV2 (9, 47). Furthermore, AAV1 does not appear to bind to heparin columns (28), further supporting the notion that HSP is not a receptor for AAV1. AAV3 does bind heparin columns. Its DNA and amino acid sequence is the most identical to that of AAV2 (33), exhibiting 82% identity at the DNA level over the entire genome and, at the amino acid level, the degree of homology between the capsid regions of AAV2 and AAV3 is 87% (24).

Two approaches, chemically cross-linking bifunctional antibodies (6) and genetic manipulation of the capsid gene, particularly in the looped-out regions of the capsid proteins (15, 31, 36, 46), have been utilized to retarget the AAV2 virus and each method has its limitations (recently reviewed in reference 30). Recently, it has been proposed that the serotypes of AAV represent a rare resource for the gene therapy community due to their unique tropism and in vivo profile (30). Rabinowitz et al. suggested a way to exploit the natural tropism of the serotypes by domain swapping of proposed exposed surfaces of the capsid regions of the serotypes. In the present study we describe a method complementary to domain swapping that takes advantage of the degree of homology between the serotypes to generate AAV2/AAV3 chimeras. In this system, defective AAV2 mutants are rescued by wild-type AAV3 sequences through homologous recombination. A collection of recombinants carrying from 16 nucleotides (nt) to 2.2 kb were isolated by this approach. All viable viruses regained the ability to bind HSP, and this correlated 100% with infectivity in human cells. This marker rescue approach can be extended to generate chimeric viruses from all serotypes and should provide a quick and simple method for mapping functional domains, as well as generating novel AAV vectors with improved phenotypes for efficient gene delivery.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and virus.

HeLa and 293 cells were maintained at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) supplemented with 10% heat inactivated fetal bovine serum and penicillin-streptomycin. Adenovirus dl309 virus has been described previously (17).

Plasmids.

The AAV3B plasmid was used in these studies (33). The plasmids H/N3761 and H3766 (31) served as starting reagents for the construction of the 1n532 and 1n562 mutants. The H/N3761 and H3766 plasmids are versions of psub201(+) (34) and pACG2 (20), respectively, which have an EcoRV in-frame linker inserted at AAV2 nt 3761 and 3766, respectively. To construct the 1n562 mutant, the 3.7-kb fragment from the HindIII-EcoRV double digestion of H3766 was ligated to the 1.8-kb fragment from the HindIII-EcoRV digestion of H/N3761. This created a unique amino acid at position 522 of VP1, which continued to be out of frame until termination at amino acid 562. For the 1n532 mutant, the 1.8-kb fragment of the HindIII-EcoRV digestion of H3766 was ligated to the 3.7-kb fragment from the HindIII-EcoRV double digestion of H/N3761. This created a unique amino acid at position 522 of VP1, which continued to be out of frame until termination at amino acid 532. The 1n562 and 1n532 clones did not contain the AAV2 terminal repeats, and each was cloned into the psub201(+) background (34) by ligation of the 2.1-kb HindIII, XcmI fragment from either the 1n562 or the 1n532 mutants to the 6.1-kb HindIII-XcmI fragment of psub201(+). Each clone was sequenced near the mutation site to ensure that the clones were correct.

The pxr2AN shuttle vector was constructed in the following manner. The pAAV2Cap plasmid (31) was modified via QuikChange mutagenesis to contain unique AflII and NotI sites in the AAV2 genome at nt 2277 and 4657, respectively, to generate the AAV2CapAN plasmid. The AAV2CapAN clone was digested with SwaI and NotI to generate a 2,262-bp fragment, which was cloned into the 5,189-bp fragment of pXR2 (28), which had been digested with NotI and SwaI. The pxr2AN shuttle vector now contains unique AflII and NotI sites flanking the capsid region.

PCR and sequencing methods.

PCR fragments from the AAV3 capsid regions were used for transfections and were amplified by the AAV3 primers AAV3Afl (5′-GGT GGG CTC TTA AGC CTG GAG TCC CTC AA-3′) and AAV3Not (5′-AGT GCA CAG CGG CCG CAG TTC AAC TGA AAC G-3′), which amplify at AAV3 nt 2273 and 4471, respectively, to generate a 2.2-kb PCR fragment. The amplification reactions consisted of an initial denaturation of 95°C for 10 min, followed by 35 cycles of denaturation for 1 min at 95°C, annealing for 1 min at 59°C, and an extension for 2 min 30 s at 72°C. These PCRs were performed with PfxTurbo polymerase (Life Technologies, Rockville, Md.). AAV3 PCR products were sequenced to ensure correctness. The AAV3 PCR capsid fragments were digested with DpnI to eliminate parental plasmid template and were purified with Wizard PCR Preps (Promega, Madison, Wis.) prior to transfection.

PCR of viral lysate was performed with either the AAV3Not and AAV3Afl primer pair, described above or the AAV2Afl (5′-GGT GGA AGC TTA AGC CTG GCC CAC CAC CAC CA-3′) and AAV2Not (5′-AAT ACG CAG CGG CCG CAG TTC AAC TGA AAC G-3′) primer pair, which amplify at AAV2 nt 2266 and 4462. Both sets of PCR primers (AAV2 and AAV3) were engineered to contain unique AflII and NotI fragments (the positions of the AflII and NotI sites in the primers are underlined) that amplify a 2.2-kb fragment that can be digested with AflII and NotI and cloned into the pxr2AN shuttle vector. The PCR conditions for the AAV2 primer pair were identical to the conditions used for the AAV3 primer pair that are described above. PCR of a viral lysate was performed with Taq polymerase (Life Technologies). DNA from PCRs was cloned into the pxr2AN shuttle vector prior to DNA sequence analyses.

Plasmid DNA was sequenced at the UNC-CH automated DNA sequencing facility on a model 377XL-96 DNA sequencer or a 3100 genetic analyzer (both from Applied Biosystems). The sequencing reactions were done by using the ABI Prism BigDye terminator cycle sequencing ready reaction kit with AmpliTaq DNA polymerase FS (Applied Biosystems).

The plasmids were sequenced with the 3′ 595 Bot primer (5′-TTG TGT GTT AAC ATC TGC GGT AGC TGC TTG-3′), which anneals at nt 1790 of the AAV2 capsid, or the AAV3Not, AAV3Afl, AAV2Afl, or AAV2Not primers described above.

Transfection and cycling.

A total of 1.8 × 106 293 cells were plated 18 h prior to transfection in a 6-cm dish. 293 cells were transfected by using Superfect reagent (Qiagen, Valencia, Calif.) according to the manufacturer's instructions with 1 μg of the AAV3 PCR fragment and 1 μg of the respective mutant plasmid. The mutant plasmids were digested with PvuII since viral DNA is replicated more efficiently within adenovirus-infected 293 cells if it is excised from the vector with PvuII before transfection (34). Immediately after transfection, the 293 cells were coinfected with adenovirus dl309 at a multiplicity of infection of 4, and virus was allowed to attach for 1 h. After attachment, virus was removed and 5 ml of Dulbecco modified Eagle medium supplemented with 2% fetal bovine serum and penicillin-streptomycin was added. At 48 to 62 h postinfection, cells were harvested by scraping and low-speed centrifugation. The cell pellet was resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline and subjected to three cycles of freeze-thawing to release the virus. The lysate was treated by incubation at 56°C for 30 min to inactivate the adenovirus. Then, 100 μl of lysate was applied to the HeLa cells with adenovirus dl309 at a multiplicity of infection of 4. At 48 to 62 h postinfection, cells were harvested as described above, and virus was subjected to a second passage on HeLa cells.

To test for production of recombinant AAV by using the three-plasmid transfection technique (49), 293 cells were transfected by Superfect reagent (Qiagen) with equimolar amounts of each plasmid pTR1/CMV/GFP, XX6-80 (adenovirus helper), and each individual chimeric AAV helper plasmid.

DNA dot blot assay.

The presence of DNA containing viral particles was determined by DNA dot blot hybridization. Briefly, 10 μl of each viral lysate sample was treated with 2.5 U of Benzonase (Sigma) in 50 mM Tris (pH 8.0)-1 mM MgCl2 for 30 min at 37°C and then placed in 0.8 N NaOH-10 mM EDTA (pH 8.0) for 30 min at 65°C to denature the samples. The samples were applied to GeneScreen Plus (NEN, Boston, Mass.) by using a dot blot manifold. The membrane was probed with psub201(+) plasmid, which had been labeled by a random primer labeling kit (Amersham-Pharmacia, Piscataway, N.J.).

Gel electrophoresis and immunoblotting.

Total protein from transfected (T) or cycle 2 (C2) infected cells were analyzed by gel electrophoresis and immunoblotting. The protein concentration was determined by the BCA method (Pierce, Rockford, Ill.). Then, 5 μg of protein lysate was loaded into each lane. Proteins were fractionated on a sodium dodecyl sulfate-10% polyacrylamide gel and transferred to Hybond ECL (Amersham Pharmacia) by using a semidry transfer apparatus (Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.). The membrane was probed with monoclonal antibody B1 directed against the carboxyl termini of the AAV2 VP3 capsid protein (45). The capsid proteins were visualized by HRP anti-mouse immunoglobulin G antibody (Sigma) by using the SuperSignal WestPico kit (Pierce) as suggested by the supplier.

RESULTS

Rationale of marker rescue.

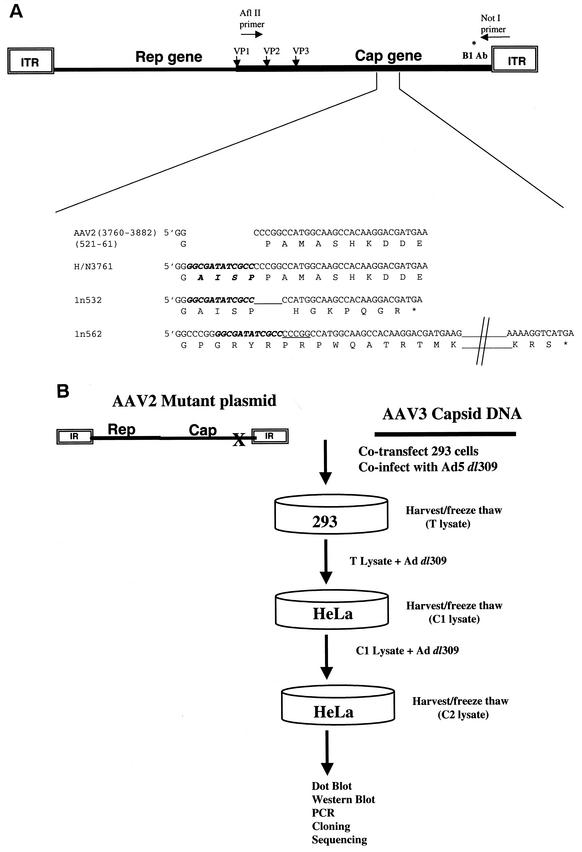

The three AAV2 capsid mutants used in these studies are depicted in Fig. 1A, and the details of the construction of two of them (1n532 and 1n562) are described in Materials and Methods. One of the capsid mutants, H/N3761, an insertion mutant described previously (31), assembles particles that protect viral DNA but are noninfectious due to a lack of heparin binding. The other mutants (1n532 and 1n562) do not assemble particles but instead express truncated capsid proteins of different lengths due to deletion and out-of-frame insertion (ln 532 and ln 562, respectively) (Fig. 1A).

FIG. 1.

Overview of the experimental system. (A) Capsid mutants used in the present study. An expanded region of the AAV2 capsid DNA sequence (nt 3760 to 3882) and VP1 protein sequence (amino acids 521 to 561) is shown. The details of the construction of the 1n532 and 1n562 capsid mutants were described in Materials and Methods. The location of the 12-bp linker insertion found in each of the mutants is in italicized. In addition to containing the 12-bp linker, the 1n532 mutant lacks 5 nt (underlined), whereas the 1n562 mutant contains an additional 5 nt (underlined). As a result, the 1n532 and 1n562 capsid mutants truncate at VP1 amino acid positions 532 and 562, respectively, and do not assemble viral particles. The H/N3761 mutant has been previously described (31) and contains a 12-bp in-frame linker (encoding the amino acids AISP) inserted at AAV2 nt 3761. The H/N3761 mutant assembles particles but is noninfectious due to a lack of heparin binding. (B) Marker rescue strategy to generate chimeric AAV. DNA from the three mutants (H/N3761, 1n532, and 1n562) was digested with PvuII and cotransfected with the AAV3 PCR product. After the transfection, the 293 cells were coinfected with adenovirus dl309. The lysates from the transfections (T) were applied in two successive cycles (C1 and C2) to HeLa cells and then infected with adenovirus dl309. The resulting viruses were analyzed by dot blot, Western blot, PCR, and DNA sequencing analyses.

The marker rescue strategy is shown schematically in Fig. 1B. In this system, the above three linearized AAV2 mutant plasmids were transfected individually into 293 cells, together with AAV3 capsid DNA, and subsequently infected with the adenovirus type 5 (Ad5) dl309 helper virus. If marker rescue occurred, then AAV3 sequences recombined into mutant AAV2 DNA, and infectious virus will be generated. The virus lysates from these transfections (T), which contain rescued chimeric virus, were then passaged onto HeLa cells in the presence of helper virus. The lysates from each cycle (C1-Cx) were analyzed for viable recombinant virus by using a number of techniques (DNA dot blot, Western analysis, PCR, cloning, and sequencing).

Cycling of the H/N3761, 1n532, or 1n562 mutants.

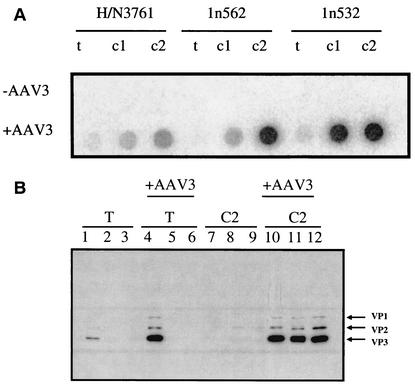

We first carried out control experiments to determine at what frequency would these mutants revert back to wild type independent of marker rescue. To determine whether H/N3761, 1n532, or 1n562 could revert to wild-type AAV2 after successive cycles of infection in the absence of wild-type AAV3 DNA fragments, each of the mutant plasmids were transfected individually into human 293 cells and then infected with Ad5 dl309. The lysates from these transfections were harvested and were cycled two consecutive times onto HeLa cells, which express high levels of HSP. If the H/N3761 or the 1n562 linker insertion was lost or if a second site mutation developed that allowed for attachment to HSP, then virus should be detected via DNA dot blot analyses. No H/N3761 or 1n562 revertant was ever identified after two consecutive cycles on HeLa cells (Fig. 2A, H/N3761 lanes and 1n562 lanes) as determined by DNA dot blot analyses. The 1n532 mutant is more deleterious than the other two mutations, since in addition to inserting a linker at position 522, this mutant also carries a 5-bp deletion. The only way for a viable revertant to arise from this plasmid substrate is for the virus to gain foreign sequences from plasmid, cellular, or from adenovirus DNA. No revertant was detected in this instance, also as judged by dot blot analyses (Fig. 2A, 1n532 lanes).

FIG. 2.

(A) Dot blot hybridization of the H/N3671, 1n532, and 1n562 mutants. 293 cells were transfected (T) with each of the mutant plasmids (H/N3761, 1n562, or 1n532) and with (+AAV3) or without (−AAV3) AAV3 capsid DNA fragments and then infected with dl309. The lysate from each was subjected to two rounds of cycling onto HeLa cells (C1 and C2). Then, 10 μl of freeze-thaw lysates from the transfection (T), cycle 1 (C1), or cycle 2 (C2) of H/N3761, 1n532, or 1n562 were applied to GeneScreen Plus membrane and probed with the psub201(+) plasmid, which had been random prime labeled. (B) Analyses of the capsid protein composition from cellular lysates. Protein lysates from the transfection of H/N3761 (lane 1), 1n532 (lane 2), and 1n562 (lane 3); the cotransfection of AAV3 capsid DNA fragments with H/N3761 (lane 4), 1n532 (lane 5), and 1n562 (lane 6); or lysates from each of the above transfections which had been cycled twice (C2) onto HeLa cells (lanes 7 to 12) were resolved on a 10% polyacrylamide electrophoresis gel and transblotted to a Hybond ECL membrane. The amount of total protein was determined by BCA assay, and 5 μg of total protein was loaded per lane. The membrane was probed with monoclonal antibody B1 directed against the carboxyl termini of the AAV2 VP3 capsid protein (45). The locations of VP1, VP2, and VP3 capsid proteins are indicated.

H/N3761 has previously been shown to produce capsid protein, form capsids, but not bind HSP or infect cells (31). Therefore, it was expected that the VP1, VP2, and VP3 proteins might be detected after transfections into 293 cells. VP3 protein was detected by Western blot analysis, as predicted (Fig. 2B, lane 1). VP1 and VP2 were detected with a longer exposure of the same gel (data not shown). Importantly, capsid proteins were not detected after two consecutive cycles on HeLa cells (Fig. 2B, lane 7) supporting the DNA dot blot data. With respect to 1n532 and 1n562 mutants, capsid components were not detected after transfection (Fig. 2B, lanes 2 and 3) or after two consecutive cycles on HeLa cells (Fig. 2B, lanes 8 and 9). As predicted, capsid proteins were not produced from these mutants in Western blot analyses since the truncations are at positions 532 and 564, respectively, and the antibody used, B1 (45), maps to a region downstream of the truncation.

Marker rescue of H/N3761, 1n532, and 1n562 with AAV3 PCR fragments.

Marker rescue experiments were performed to determine whether AAV3 capsid DNA fragments could rescue the H/N3761, 1n532, or 1n562 mutants. In these experiments, 293 cells were cotransfected with each of the mutant plasmids and AAV3 PCR fragments and then infected with Ad5 dl309. In each instance, protected viral DNA was detected from transfection and cycling lysate for each mutant (Fig. 2A, +AAV3 row), indicating rescue of viable virions.

Capsid proteins were detected from H/N3761 transfection lysates but not from the 1n532 or the 1n562 transfection lysate (Fig. 2B, lanes 4 to 6), at least to the level of detection by our Western blot analysis. Although full-length capsid proteins from recombinants were not detected in the Western blot analyses of the transfection lysates, obvious DNA rescue took place at this step since viral capsid proteins were detected from each mutant after cycling on HeLa cells (Fig. 2B, lanes 10 to 12).

Together, these results indicated that AAV3 DNA sequences were able to rescue the defect of these three different AAV2 capsid mutants to produce viable AAV2/AAV3 chimeric viruses able to infect HeLa cells.

DNA sequence analyses of the AAV2/AAV3 chimeric virus.

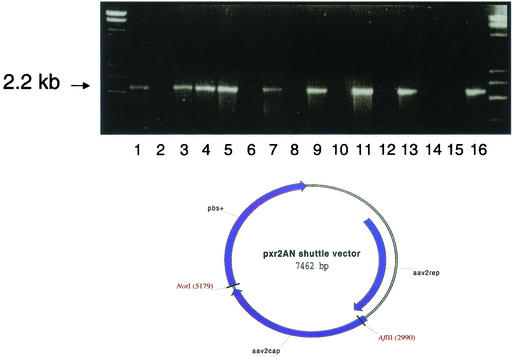

In order to determine the DNA sequence of the AAV2/AAV3 chimeric virus, PCR analyses was performed on viral lysates from several independent marker rescue experiments. PCR was performed on two samples from H/N3761 (Fig. 3, lanes 1, 2, 7, and 8), three samples from 1n562 (Fig. 3, lanes 3 to 6, 9, and 10), and one sample from the 1n532 marker rescue experiments (Fig. 3, lanes 11 and 12). Lysates from the second cycle (C2) on HeLa cells from each of these experiments were amplified with either the AAV2-specific primers (Fig. 3, odd-numbered lanes) or the AAV3-specific primers (Fig. 3, even-numbered lanes); see Fig. 1A for approximate location of the primers. The specificity of the primers was verified by amplification of AAV2 or AAV3 plasmids (Fig. 3, lanes 13 to 16).

FIG. 3.

PCR analyses of rescued virus from independent marker rescue experiments. (Top) PCR analyses were performed on two independent samples from H/N3761 (lanes 1, 2, 7, and 8), three independent samples from 1n562 (lanes 3 to 6, 9, and 10), one sample from the 1n532 marker rescue experiments (lanes 11 and 12), AAV2 plasmid (lanes 13 and 14), and AAV3 plasmid (lanes 15 and 16). Lysates from the second cycle (C2) on HeLa cells from each of these experiments were amplified with either AAV2-specific primers (lanes 1, 3, 5, 7, 9, 11, 13, and 15) or AAV3-specific primers (lanes 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 14, and 16). The location of the 2.2-kb PCR product is indicated by an arrow. (Bottom) Diagram of the pxr2AN shuttle vector. This shuttle vector is a modification of the pxr2 vector generated by Rabinowitz and Samulski (30), except that AflII and NotI sites flanking the capsid regions were engineered to facilitate cloning of PCR products.

As can be seen in Fig. 3, a 2.2-kb fragment from the lysates of all marker rescue experiments was amplified by the AAV2 primer pair, indicating that a region of AAV3 recombined into the AAV2 mutants. In one experiment the AAV3 primer pair was able to amplify a 2.2-kb fragment from the lysate. This indicated that at least for one example a mixed virus population was present (Fig. 3, lanes 3 and 4). Direct sequencing of the PCR products suggested that a diverse mixture of chimeric viral DNA had been produced (data not shown).

To confirm that a diverse mixture of AAV2/AAV3 chimeras was present, an AAV helper shuttle vector was designed so that all PCR products could be readily cloned (Fig. 3). This shuttle vector was engineered to contain a unique AflII site near the beginning of the capsid gene and a unique NotI site after the end of the capsid gene facilitating cloning of all PCR products directly into an AAV helper plasmid for sequencing and vector production.

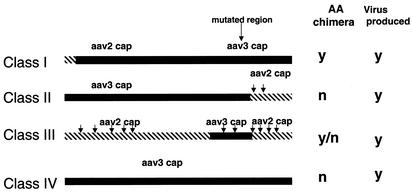

Both restriction enzyme and DNA sequencing analyses identified four classes of AAV2/AAV3 chimeras (Fig. 4). Class I chimeras contained the 5′ region of the AAV2 capsid gene up to nt 180, with the remainder of the capsid gene entirely made up of AAV3 sequences. Class II mutants contain 5′ AAV3 sequences, encompassing the mutation site, and then a preferred crossover to AAV2 sequences, 3′ of the mutation site, at one of two locations (nt 2065 and 2160). Class III mutants were the most heterogeneous and these types of AAV2/AAV3 recombinants resulted from crossover at different 5′ and 3′ locations along the capsid coding region (see Table 1 and Fig. 5). All class III mutants covered the area of mutation. In 89 sequenced clones, we were unable to identify second any site revertants involving AAV 3 capsid DNA. Finally, class IV chimeras contained almost the entire AAV3 capsid sequences (Fig. 5).

FIG. 4.

Four classes of AAV2/AAV3 chimeras are produced from marker rescue experiments. The four classes of AAV2/AAV3 capsid chimeras identified are depicted, and arrows indicate the approximate sites where homologous recombination occurred between the capsid DNA of serotypes 2 and 3. Whether these classes were chimeras at the amino acid level is indicated next to each class. Representative AAV helper clones from each class were all able to generate rAAV in a standard triple-transfection assay.

TABLE 1.

Classes of AAV2/AAV3 chimeras characterized in this studya

| Class | No. of clones | Subclass | No. of clones | Representative clone | Crossover nt

|

Amino acid differences | Virus production | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5′ | 3′ | |||||||

| I | 1 | I | 1 | 18-0 | 180 | NA | Yes (N) | Yes |

| II | 38 | IIa | 3 | 1F | NA | 2065 | No | Yes |

| IIb | 2 | NA | 2160 | No | No | |||

| III | 46 | IIIa | 2 | 5A | 1541 | 1600 (M) | No | Yes |

| IIIb | 2 | 1549 | 1600 | No | ND | |||

| IIIc | 3 | 1541 | 1600 (M) | No | ND | |||

| IIId | 2 | 17-5 | 208 | 2153 | Yes (N) | Yes | ||

| IIIe | 1 | 18-C | 345 | 2065 | Yes (N) | Yes | ||

| IIIf | 1 | 18-19 | 530 | 2053 | Yes (N) | Yes | ||

| IIIg | 1 | 18-42 | 530 | 2095 | Yes (N) | Yes | ||

| IIIh | 1 | 18-25 | 530 | 2153 | Yes (N) | Yes | ||

| IIIi | 1 | 18NN | 676 | 1846-1921 | Yes (N and C) | Yes | ||

| IIIj | 1 | 18-Z | 530 | 2065 | Yes (N and C) | Yes | ||

| IIIk | 2 | 18-43 | 650 | 2165 | Yes (N) | Yes | ||

| IV | 4 | IV | 4 | 3-41 | NA | NA | No | Yes |

The four classes of chimeric clones depicted in Fig. 4 were placed into subclasses based on 5′ and 3′ crossover points. Nucleotide positions of crossover are based on numbering beginning from VP1 and indicate the first nucleotide position of the VP1 capsid DNA that can be identified as distinctly AAV2 or AAV3. For example, clone 17-5 is a class III chimera that contains AAV2 DNA sequences at the 5′ regions, changes to AAV3 at position nt 208, and then changes back to AAV2 at nt 2153. Whether the nucleotide differences correlated with change is indicated, and whether the amino acid differences were at the amino terminus (N) or the carboxy terminus (C) is indicated parenthetically. Whether virus was produced from the respective vector is also indicated. NA, not applicable; ND, not determined; M, microrecombination.

FIG. 5.

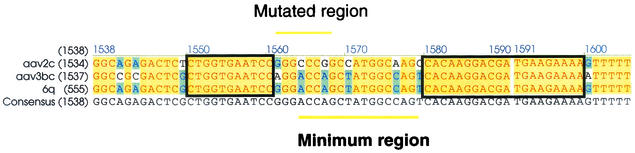

Sequence alignment of class III chimera clone 6q. Sequence of a portion of the AAV2, AAV3, and AAV2/3 chimeric clone 6q (corresponding to AAV3 capsid open reading frame nt 1538 to 1605) is shown. A 16-bp region of AAV3 (underlined; nt 1564 to 1579, based on the AAV3 VP1) was identified as the minimal AAV3 region necessary to rescue the defects of the AAV2 virus (the line above indicates the location of the mutated region). For the generation of the chimeric clone 6q, an 11-bp region on the 5′ end (bp 1550 to 1560) and a 20-bp region on the 3′ end of the AAV3 (bp 1580 to 1599) were identified as crossover sites. The sites where homologous recombination is presumed to occur are shown in boxes.

One type of class III mutants resulted from homologous recombination of small AAV3 DNA sequences near the mutation sites, flanked on either side by AAV2 capsid sequences (Fig. 5). A 16-bp region of AAV3 (nt 1564 to 1579, based on the AAV3 VP1) was identified as the minimal AAV3 region necessary to rescue the defects of the AAV2 virus. For the generation of this 16-bp AAV2/AAV3 recombinant, an 11-bp region on the 5′ end (bp 1550 to 1560) and a 20-bp region on the 3′ end of the AAV3 (bp 1580 to 1599) was identified as crossover sites (Fig. 5). In this viable recombinant, although the DNA sequences were different, the amino acid sequences were identical. Importantly, some class III chimeras exhibited amino acid differences outside of the original mutated region (Fig. 4 and Table 1). We could not discern an overt phenotype related to these amino acid changes on chimeric viral infectivity based on the assays described above. However, common to all viable recombinants was the ability to regain binding activity to HSP. We observed 100% correlation between chimeric virus ability to bind HSP and viability, thus supporting the importance of HSP in AAV infection (40). Since previous studies have shown that AAV DNA can efficiently cross-package into virion shells of different serotypes (31), we assayed a number of the sequenced recombinants for their ability to generate viable chimeric AAV vector. Triple transfection was performed by using 12 different chimeras as an AAV helper. In all 12 instances recombinant virus was produced (Table 1). This result suggests that the viral DNA templates packaged into the virions isolated after cycling were also capable of expressing chimeric capsid proteins capable of generating infectious virus.

Together, these studies indicate that marker rescue is a valid mechanism for rescuing mutations in the viral capsid of one AAV serotype by using fragments from another serotype. Furthermore, this is an approach that may be useful in mapping functional domains between the existing AAV serotypes, as well in generating unique AAV vectors with serotype-specific properties.

DISCUSSION

Due to the diversity of their biological properties, the serotypes of AAV are important resources for the gene therapy community. In order to develop the full potential of AAV vectors for gene therapy applications, it is of interest to define the capsid domains of the individual serotypes responsible for these properties. The ability to interchange these regions should facilitate designing AAV vectors with novel tropisms and transduction properties.

Domain swapping via various cloning methods as a means to exchange serotype specific properties such as receptor binding, tissue tropism, and purification schemes has been proposed (30). Xiao et al. identified regions of the AAV1 capsid responsible for its ability to transduce skeletal muscle by systematically exchanging domains between AAV1 and AAV2. This approach, which relied on cloning and assessing each individual construct, was successful and demonstrates the importance of such a strategy (W. Xiao et al., submitted for publication).

We used a marker rescue system based on homologous recombination as an alternate method to generate chimeric AAV vectors. One advantage to this approach is that domains are swapped based on selection and function and not by physical maps. Three published observations indicated that this approach was feasible. First, recombination between the serotypes has been shown to occur in nature. A laboratory variant of AAV, referred to as AAV6, appears to be the result of recombination between AAV1 and AAV2, which exchange only 71 bp (47). Furthermore, work by Senepathy and Carter in the early 1980s established that as few as 6 nt of homology could result in recombination between two AAV2 mutant genomes (35). Third, the known serotypes display very high degree of homology when subjected to a pairwise comparison. Serotypes 1, 2, and 3 exhibited homology in the 80% range, whereas serotypes 4 and 5, the most divergent, exhibited homology to the other serotypes in the 60% range overall. This homology is dispersed throughout the entire capsid genome and thus there are numerous regions where homologous recombination can occur between individual serotypes.

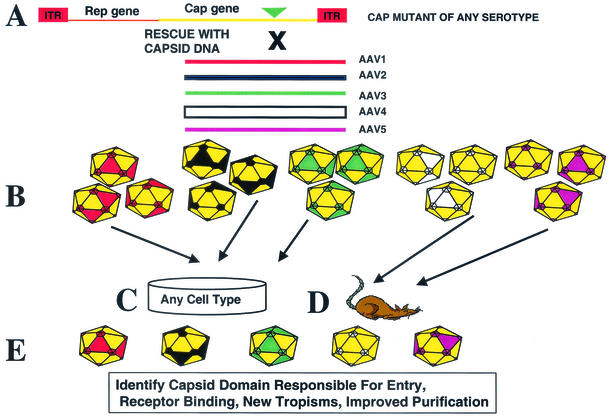

Our marker rescue system relies on the cotransfection of an AAV infectious clone carrying a mutation in the capsid coding region with wild-type capsid sequences from a different serotype (Fig. 6A), followed by coinfection with adenovirus. The homology that exists between the AAV DNA of the different serotypes allows for homologous recombination to occur resulting in, at the transfection stage, a mixed population of chimeric viral genomes. The chimeric capsid DNA can be PCR amplified at this step was cloned into the shuttle vector (pxr2AN), and then this library of recombinants (Fig. 6B) can be examined for biological properties similar to the approach described by Xiao et al. (submitted). Alternatively, the transfection lysate can be cycled onto any cell type of interest as a selection step (Fig. 6C). The cell type utilized has an important bearing on the types of chimeras observed (e.g., AAV2 chimera that is not dependent on heparin sulfate receptor). In addition to selection on specific cell types for novel capsid with new tropism, direct infection of animals (Fig. 6D) with this library and screening of individual tissues for dominant chimeric virus can be carried out. Whether the library is cycled onto tissue culture cells or animals, it serves the same purpose of enriching for the predominant viral recombinant (Fig. 6E). A similar approach was successfully used for phage display libraries in order to help identify tissue-specific targeting ligands (4).

FIG. 6.

Predicted utility of the marker rescue approach to generate chimeric AAV vectors. The marker rescue approach can be utilized to generate chimeric virus from any combination of AAV serotypes. A capsid mutant of any serotype serves as the marker rescue plasmid template. (A) The mutation can be rescued via cotransfection capsid DNA from any other template. (B) After transfection of the cells with the mutant plasmid and capsid DNA, a mixed population of viral genomes is produced that can be PCR amplified and cloned into the shuttle vector, and individual clones can then be assessed for biological properties. (C and D) Alternatively, as a selection step the transfection lysate can be cycled onto any cell type of interest (C) or can be used to directly infect animals (D). (E) Ultimately, the cycling onto cells or in animals serves to enrich for a predominant viral recombinant.

In the present study we describe the use of serotype 3 DNA to rescue defects in an AAV2 capsid. To carry out this study, we used three different mutants of the AAV2 capsid. One mutant (previously described) was capable of producing intact viral particles but was unable to infect cells due to a lack of heparin binding (31). The other two mutants produce truncated capsid proteins and were unable to produce AAV virions. The mutated templates were composed of a 4-amino-acid insertion (H/N3761), out-of-frame deletion (1n532), and out-of-frame duplication mutations (1n562). Our approach allowed for the selection of virus that would be viable and produce moderate to high yields. Specifically, the selection relied on recombinants that were viable after a cycling step on human cells expressing heparin sulfate. Because AAV2 and AAV3 appear to utilize the same receptor, we readily isolated viable recombinants that regain heparin sulfate binding. The feasibility of this approach was demonstrated via dot blot, Western blot, cloning, and sequencing.

We predicted and obtained four classes of chimeras based on the regions of crossover. The smallest viable recombinant contained only 16 nt, whereas the largest span the entire 2.2-kb fragment of type 3 capsid sequences. These examples show the diversity that can be generated by using this approach. Although it was difficult to assess the exact crossover point in the chimeras due to stretches of homologous sequences, some of these recombinants exhibited differences only at the DNA level (based on redundancy of the genetic code), whereas others had changes at the nucleic acid level that resulted in chimeric protein. Of the 89 clones isolated and sequenced, only 1 recombinant (class I) was composed of a 5′ type 2 sequence (60 amino acids), followed by the remainder of type 3 coding sequences. A significant number of recombinants (38 of 89, class II) carried the 5′ portion of type 3 spanning the AAV 2 capsid mutated sites, followed by a 3′ portion that was type 2 DNA. In a number of these isolates, we observed break points that clustering around nt 2060 and 2160. These preferred crossover points were also observed with class III recombinants, which were distinguished by 5′ and 3′ ends uniquely type 2 DNA with various portions of type 3 DNA recombined between these sequences. After thorough analysis, the preference for the 3′ crossover point was most likely due to the fact that this region contained the largest stretch of homology between the two serotypes (50 nt), since all of the carboxy amino acids past this breakpoint are conserved. We also observed two additional common crossover regions. One was located in the 5′ portion of the type 2 capsid gene (nt 530), and the second region was located immediately downstream of the mutated region in the marker rescue template (nt 1600). Both of these areas contained stretches of pyrimidine residues. Additionally, the 5′ crossover region was preceded by a putative small stem-loop structure that may have influenced recombination. Overall, it appeared that the common break points that we observed were consistent with homologous recombination pathways (large blocks of homologous sequences and duplex regions subject to melting apart). Finally, we isolated recombinants that contained the entire 2.2-kb fragment of type 3 sequences. These were not common isolates, although one could imagine the advantage of replacing the entire capsid-coding region rather than replacing mutated segments.

From the number of classes that were identified, this marker rescue technique may be a valuable method to map or define the domains equivalent between the different AAV serotypes. This becomes important since only the three-dimensional structure of AAV2 has been determined (50), and investigators must rely on this information to predict regions of the capsid of the other serotypes that are involved in receptor binding. The marker rescue approach should more precisely identify amino acid domains within the crystal framework. For example, by using the marker rescue approach, the region or regions of AAV4 or AAV5 responsible for sialic acid binding may be placed in the context of AAV2 (Fig. 6) (19) In addition, as more functional domains are identified (nuclear localization domains, endosome escape motifs, packaging mutants, regions with lipase activity, etc.) for type 2 or the other serotypes, marker rescue should allow one to quickly map equivalent domains in the other serotypes.

Since the method of marker rescue was first described by Hutchison and Edgell to map DNA fragments from bacteriophage φX (16), this technique has been used to map the functions of genes from a diverse array of organisms, including viruses, bacteria, and plants (42, 44, 51). Here the use of marker rescue is described as a means for generating AAV chimeras. We demonstrated the use of three AAV2 mutants as a platform for marker rescue; however, it should be possible to rescue a mutant of any serotype with DNA from another serotype. Ultimately, a collection of chimeric viruses will be generated that should possess new phenotypes and tropism that will significantly impact vector targeting, as well as optimal vector transduction for human gene therapy.

While this study was in review, the crystal structure of AAV2 was published (50). Marker rescue should complement, as well as expand, the information now being gleaned from the crystal structure. With the crystal structure in hand and the ability to produce viable chimeras from marker rescue-like approaches, we should see in the near future significant contributions to both AAV biology and vector development.

FIG. 1

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Public Health Service fellowship 1 F32 GM63446-01, NIH research grants 5-31111, 5-51686, and 5-33215, as well as by NIH vector core support grants 5-51690 and 5-33220.

We thank Prina Patel for excellent technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Agbandje, M., S. Kajigaya, R. McKenna, N. S. Young, and M. G. Rossmann. 1994. The structure of human parvovirus B19 at 8 Å resolution. Virology 203:106-115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Agbandje, M., R. McKenna, M. G. Rossmann, M. L. Strassheim, and C. R. Parrish. 1993. Structure determination of feline panleukopenia virus empty particles. Proteins Struct. Funct. Genet. 16:155-171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Agbandje-McKenna, M., A. L. Llamas-Saiz, F. Wang, P. Tattersall, and M. G. Rossmann. 1998. Functional implications of the structure of the murine parvovirus, minute virus of mice. Structure 6:1369-1381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arap, W., M. G. Kolonin, M. Trepel, J. Lahdenranta, M. Cardo-Vila, R. J. Giordano, P. J. Mintz, P. U. Ardelt, V. J. Yao, C. I. Vidal, L. Chen, A. Flamm, H. Valtanen, L. M. Weavind, M. E. Hicks, R. E. Pollock, G. H. Botz, C. D. Bucana, E. Koivunen, D. Cahill, P. Troncoso, K. A. Baggerly, R. D. Pentz, K. A. Do, C. J. Logothetis, and R. Pasqualini. 2002. Steps toward mapping the human vasculature by phage display. Nat. Med. 8:121-127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bantel-Schaal, U., H. Delius, R. Schmidt, and H. Z. Hausen. 1999. Human adeno-associated virus type 5 is only distantly related to other known primate helper-dependent parvoviruses. J. Virol. 73:939-947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bartlett, J. S., J. Kleinschmidt, R. C. Boucher, and R. J. Samulski. 1999. Targeted adeno-associated virus vector transduction of nonpermissive cells mediated by a bispecific F(ab′γ)2 antibody. Nat. Biotechnol. 17:181-186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berns, K. I. 1996. Parvoviridae: the viruses and their replication, p. 2173-2197. In B. N. Fields, D. M. Knipe, and P. M. Howley (ed.), Fields virology, 3rd ed. Lippincott-Raven Publishers, Philadelphia, Pa.

- 8.Bloom, M. E., D. A. Martin, K. L. Oie, M. E. Huhtanen, F. Costello, J. B. Wolfinbarger, S. F. Hayes, and M. Agbandje-McKenna. 1997. Expression of Aleutian mink disease parvovirus capsid proteins in defined segments: localization of immunoreactive sites and neutralizing epitopes to specific regions. J. Virol. 71:705-714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chao, H., Y. Liu, J. Rabinowitz, C. Li, R. J. Samulski, and C. E. Walsh. 2000. Several log increase in therapeutic transgene delivery by distinct adeno-associated viral serotype vectors. Mol. Ther. 2:619-623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chiorini, J. A., F. Kim, L. Yang, and R. M. Kotin. 1999. Cloning and characterization of adeno-associated virus type 5. J. Virol. 73:1309-1319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chiorini, J. A., L. Yang, Y. Liu, B. Safer, and R. M. Kotin. 1997. Cloning of adeno-associated virus type 4 (AAV4) and generation of recombinant AAV4 particles. J. Virol. 71:6823-6833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davidson, B. L., C. S. Stein, J. A. Heth, I. Martins, R. M. Kotin, T. A. Derksen, J. Zabner, A. Ghodsi, and J. A. Chiorini. 2000. Recombinant adeno-associated virus type 2, 4, and 5 vectors: transduction of variant cell types and regions in the mammalian central nervous system. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:3428-3432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Duan, D., Z. Yan, Y. Yue, W. Ding, and J. F. Engelhardt. 2001. Enhancement of muscle gene delivery with pseudotyped adeno-associated virus type 5 correlates with myoblast differentiation. J. Virol. 75:7662-7671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fisher, K. J., K. Jooss, J. Alston, Y. Yang, S. E. Haecker, K. High, R. Pathak, S. E. Raper, and J. M. Wilson. 1997. Recombinant adeno-associated virus for muscle directed gene therapy. Nat. Med. 3:306-312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Girod, A., M. Ried, C. Wobus, H. Lahm, K. Leike, J. Kleinschmidt, G. Deleage, and M. Hallek. 1999. Genetic capsid modifications allow efficient re-targeting of adeno-associated virus type 2. Nat. Med. 5:1052-1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hutchinson, C. A., III, and M. H. Edgell. 1971. Genetic assay for small fragments of bacteriophage φX174 deoxyribonucleic acids. J. Virol. 8:181-189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jones, N., and T. Shenk. 1979. Isolation of adenovirus type 5 host range deletion mutants defective for transformation of rat embryo cells. Cell 17:683-689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jooss, K., Y. Yang, K. J. Fisher, and J. M. Wilson. 1998. Transduction of dendritic cells by DNA viral vectors directs the immune response to transgene products in muscle fibers. J. Virol. 72:4212-4223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaludov, N., K. E. Brown, R. W. Walters, J. Zabner, and J. A. Chiorini. 2001. Adeno-associated virus serotype 4 (AAV4) and AAV5 both require sialic acid binding for hemagglutination and efficient transduction but differ in sialic acid linkage specificity. J. Virol. 75:6884-6893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li, J., R. J. Samulski, and X. Xiao. 1997. Role for highly regulated rep gene expression in adeno-associated virus vector production. J. Virol. 71:5236-5243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McCown, T. J., X. Xiao, J. Li, G. R. Breese, and R. J. Samulski. 1996. Differential and persistent expression patterns of CNS gene transfer by an adeno-associated virus (AAV) vector. Brain Res. 713:99-107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McKenna, R., N. H. Olson, P. R. Chipman, T. S. Baker, T. F. Booth, J. Christensen, B. Aasted, J. M. Fox, M. E. Bloom, J. B. Wolfinbarger, and M. Agbandje-McKenna. 1999. Three-dimensional structure of Aleutian mink disease parvovirus: implication for disease pathogenicity. J. Virol. 73:6882-6891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moskalenko, M., L. Chen, M. V. Roey, B. A. Donahue, R. O. Snyder, J. B. Mcarthur, and S. D. Patel. 2000. Epitope mapping of human anti-adeno-associated virus type 2 neutralizing antibodies: implications for gene therapy and virus structure. J. Virol. 74:1761-1766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Muramatsu, S.-I., H. Mizakami, N. S. Young, and K. E. Brown. 1996. Nucleotide sequencing and generation of an infectious clone of adeno-associated virus 3. Virology 221:208-217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Muzyczka, N. 1992. Use of adeno-associated virus as a general transduction vector for mammalian cells. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 158:97-129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Patijn, G. A., and M. A. Kay. 1999. Hepatic gene therapy using adeno-associated virus vectors. Semin. Liver Dis. 19:61-69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Qing, K., C. Mah, J. Hansen, S. Zhou, V. Dwarki, and A. Srivastava. 1999. Human fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 is a co-receptor for infection by adeno-associated virus 2. Nat. Med. 5:71-77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rabinowitz, J. E., F. Rolling, C. Li, H. Conrath, W. Xiao, X. Xiao, and R. J. Samulski. 2002. Cross packaging of a single AAV type 2 vector genome into multiple AAV serotypes enables transduction with broad specificity. J. Virol. 76:791-801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rabinowitz, J. E., and J. Samulski. 1998. Adeno-associated virus expression systems for gene transfer. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 9:470-475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rabinowitz, J. E., and R. J. Samulski. 2000. Building a better vector: the manipulation of AAV virions. Virology 278:301-308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rabinowitz, J. E., W. Xiao, and R. J. Samulski. 1999. Insertional mutagenesis of AAV2 capsid and the production of recombinant virus. Virology 265:274-285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Robbins, P. D., H. Tahara, and S. C. Ghivizzani. 1998. Viral vectors for gene therapy. Trends Biotechnol. 16:35-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rutledge, E. A., C. L. Halbert, and D. W. Russell. 1998. Infectious clones and vectors derived from adeno-associated virus (AAV) serotypes other than AAV type 2. J. Virol. 72:309-319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Samulski, R. J., L.-S. Chang, and T. Shenk. 1987. A recombinant plasmid from which an infectious adeno-associated virus genome can be excised in vitro and its use to study viral replication. J. Virol. 61:3096-3101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Senapathy, P., and B. J. Carter. 1984. Molecular cloning of adeno-associated virus variant genomes and generation of infectious virus by recombination in mammalian cells. J. Biol. Chem. 259:4661-4666. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shi, W., G. S. Arnold, and J. S. Bartlett. 2001. Insertional mutagenesis of the adeno-associated virus type 2 (AAV2) capsid gene and generation of AAV2 vectors targeted to alternative cell-surface receptors. Hum. Gene Ther. 12:1697-1711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Simpson, A. A., P. R. Chipman, T. S. Baker, P. Tijssen, and M. G. Rossmann. 1998. The structure of an insect parvovirus (Galleria mellonella densovirus) at a 3.7 Å resolution. Structure 6:1355-1367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Srivastava, A., E. W. Lusby, and K. I. Berns. 1983. Nucleotide sequence and organization of the adeno-associated virus 2 genome. J. Virol. 45:555-564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Summerford, C., J. S. Bartlett, and R. J. Samulski. 1999. αVβ5 integrin: a co-receptor for adeno-associated virus type 2 infection. Nat. Med. 5:78-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Summerford, C., and R. J. Samulski. 1998. Membrane-associated heparan sulfate proteoglycan is a receptor for adeno-associated virus type 2 virions. J. Virol. 72:1438-1445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tsao, J., M. S. Chapman, M. Agbandje, W. Keller, K. Smith, H. Wu, M. Luo, T. J. Smith, M. G. Rossmann, R. W. Compans, and C. R. Parrish. 1991. The three-dimensional structure of canine parvovirus and its functional implication. Science 251:1456-1464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vries, J. D., and W. Wackernagel. 1998. Detection of nptII (kanamycin resistance) genes in genomes of transgenic plants by marker-rescue transformation. Mol. Gen. Genet. 257:606-613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Walters, R. W., S. M. Yi, S. Keshavjee, K. E. Brown, M. J. Welsh, J. A. Chiorini, and J. Zabner. 2001. Binding of adeno-associated virus type 5 to 2,3-linked sialic acid is required for gene transfer. J. Biol. Chem. 276:20610-20616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang, S. P., and S. Shuman. 1996. A temperature-sensitive mutation of the vaccinia virus E11 gene encoding a 15-kDa virion component. Virology 216:252-257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wobus, C. E., B. Hugle-Dorr, A. Girod, G. Petersen, M. Hallek, and J. A. Kleinschmidt. 2000. Monoclonal antibodies against the adeno-associated virus type 2 (AAV-2) capsid: epitope mapping and identification of capsid domains involved in AAV-2-cell interaction and neutralization of AAV-2 infections. J. Virol. 74:9281-9293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wu, P., W. Xiao, T. Conlon, J. Hughes, M. Agbandje-McKenna, T. Ferkol, T. Flotte, and N. Muzyczka. 2000. Mutational analysis of the adeno-associated virus type 2 (AAV2) capsid gene and construction of AAV2 vectors with altered tropism. J. Virol. 74:8635-8647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Xiao, W., N. Chirmule, S. C. Berta, B. McCullough, G. Gao, and J. M. Wilson. 1999. Gene therapy vectors based on adeno-associated virus type 1. J. Virol. 73:3994-4003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Xiao, X., J. Li, and R. J. Samulski. 1996. Efficient long-term gene transfer into muscle tissue of immunocompetent mice by adeno-associated virus vector. J. Virol. 70:8098-8108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Xiao, X., J. Li, and R. J. Samulski. 1998. Production of high-titer recombinant adeno-associated virus vectors in the absence of helper adenovirus. J. Virol. 72:2224-2232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Xie, Q., W. Bu, S. Bhatia, J. Hare, T. Somasundaram, A. Azzi, and M. S. Chapman. 2002. The atomic structure of adeno-associated virus (AAV-2), a vector for human gene therapy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:10405-10410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yamamoto, Y., Y. Sato, S. Takahaski-Abbe, K. Abbe, T. Yamada, and H. Kizaki. 1996. Cloning and sequence analysis of the pfl gene encoding pyruvate formate-lyase from Streptococcus mutans. Infect. Immun. 64:385-391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zabner, J., M. Seiler, R. Walters, R. M. Kotin, W. Fulgeras, B. L. Davidson, and J. A. Chiorini. 2000. Adeno-associated virus type 5 (AAV5) but not AAV2 binds to the apical surfaces of airway epithelia and facilitates gene transfer. J. Virol. 74:3852-3858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]