Abstract

Herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2 (HSV-1 and HSV-2) can trigger or block apoptosis in a cell type-dependent manner. We have recently shown that the protein kinase activity of the large subunit of the HSV-2 ribonucleotide reductase (R1) protein (ICP10 PK) blocks apoptosis in cultured hippocampal neurons by activating the extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) survival pathway (Perkins et al., J. Virol. 76:1435-1449, 2002). The present studies were designed to better elucidate the mechanism of ICP10 PK-induced neuroprotection and determine whether HSV-1 has similar activity. The data indicate that apoptosis inhibition by ICP10 PK involves a c-Raf-1-dependent mechanism and induction of the antiapoptotic protein Bag-1 by the activated ERK survival pathway. Also associated with neuroprotection by ICP10 PK are increased activation/stability of the transcription factor CREB and stabilization of the antiapoptotic protein Bcl-2. HSV-1 and the ICP10 PK-deleted HSV-2 mutant ICP10ΔPK activate JNK, c-Jun, and ATF-2, induce the proapoptotic protein BAD, and trigger apoptosis in hippocampal neurons. c-Jun activation and apoptosis are inhibited in hippocampal cultures infected with HSV-1 in the presence of the JNK inhibitor SP600125, suggesting that JNK/c-Jun activation is required for HSV-1-induced apoptosis. Ectopically delivered ICP10 PK (but not its PK-negative mutant p139) inhibits apoptosis triggered by HSV-1 or ICP10ΔPK. Collectively, the data indicate that ICP10 PK-induced activation of the ERK survival pathway results in Bag-1 upregulation and overrides the proapoptotic JNK/c-Jun signal induced by other viral proteins.

Apoptosis is a tightly regulated, irreversible process that results in cell death in the absence of inflammation. It is necessary for the proper development of the nervous system, but when it is inappropriate in timing or extent, apoptosis in the central nervous system can trigger or account for progression of neurodegeneration in various diseases, including stroke, trauma, and virus infection (37, 89). Morphological changes associated with apoptosis include nuclear and cytoplasmic condensation, intranucleosomal DNA cleavage, and blebbing of the cell into membrane-bound apoptotic bodies. Apoptosis is primarily mediated by caspases, which are cysteine proteases with aspartate specificity that are activated by the cleavage of inactive zymogens (procaspases).

Caspase 3 is one of the key executioners of apoptosis. Its activation requires proteolytic cleavage of the inactive procaspase 3 into 17- to 20-kDa and 12-kDa fragments. Activated caspase-3 is, in turn, responsible for the proteolytic cleavage of many key proteins, such as the nuclear poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase, which is involved in DNA repair. Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase cleavage to an 85-kDa fragment is a critical event in the commitment to undergo apoptosis (48).

Signal transduction pathways are linked to the apoptotic machinery (9, 49). Activation of the c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) (also known as stress-activated protein kinase) and the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase protein cascades is associated with increased expression of proapoptotic proteins (49, 51). JNK and its target c-Jun play an important role in triggering neuronal apoptosis (35, 60). Survival stimuli cause the membrane-bound G protein Ras to adopt an active, GTP-bound state, and it, in turn, coordinates the activation of a multitude of downstream effectors. The ERK survival pathway involves c-Raf-1 kinase and activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase (MEK) and mitogen-activated protein kinase (ERK). A variety of genes are ERK targets, including those required for cell cycle progression (54). The ERK survival pathway overrides the effects of apoptotic signals, apparently by upregulating antiapoptotic Bcl-2 proteins through a transcription dependent mechanism which involves activation of the calcium/cyclic AMP response element binding (CREB) protein (49, 80, 86, 87).

Bcl-2 proteins are a family of apoptosis regulators that includes members with antiapoptotic (Bcl-2) or proapoptotic (BAD) activity. Antiapoptotic Bcl-2 proteins prevent caspase activation by sequestering their proforms, inhibiting the release of cytochrome c, or preventing mitochondrial dysfunction. Susceptibility to a given apoptotic stimulus is determined by the interaction between pro- and antiapoptotic family members (70). The Bcl-2-associated athanogene (Bag-1) interacts with Bcl-2 to cooperatively interfere with the apoptotic cascade at the level of caspase activation (79). Bag-1 also has Bcl-2-independent antiapoptotic activity (79), and it enhances c-Raf-1 kinase activity through a Ras-independent mechanism (82).

Viruses depend on cells for their replication and can differentially affect various signaling pathways. Herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) and HSV-2 can trigger or counteract apoptosis in a cell-specific manner (2, 15, 38, 47, 61, 69). The mechanism by which they trigger apoptosis and the identity of the proapoptotic genes are still poorly understood. Antiapoptotic activity, on the other hand, has been ascribed to the HSV-1 and HSV-2 gene US3 (38, 47, 61), the HSV-1 genes γ134.5, US5, ICP27, and LAT (2, 15, 47, 69), and the HSV-2 gene ICP10 PK (66, 67). In nonneuronal cells, the HSV-1 US3 protein kinase (PK) phosphorylates, and thereby inactivates, the proapoptotic Bcl-2 family member BAD (61). However, the activity of the antiapoptotic HSV-1 genes in hippocampal neurons, if any, is still unclear.

The large subunit of HSV-2 ribonucleotide reductase (R1, also known as ICP10) has an intrinsic PK activity that is required for immediate-early (also known as α) gene expression and HSV-2 growth in nonneuronal cells, involving activation of the ERK survival pathway (73, 75, 76). Our laboratory first demonstrated that ICP10 PK blocks apoptosis of hippocampal neurons caused by loss of trophic support, genetic defects, or virus infection by activating MEK/ERK (66, 67). Antiapoptotic activity does not require de novo viral protein synthesis and appears to be mediated by the ICP10 PK protein in the virion tegument (66, 74).

Here we report that ERK activation by ICP10 PK in hippocampal neurons upregulates the antiapoptotic protein Bag-1 and consequently overrides a JNK/c-Jun signal(s) responsible for virus-induced apoptosis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Viruses and plasmids.

HSV-2 (G), HSV-1 (F), HSV-2 mutants ICP10ΔPK and ICP10ΔRR, which have deletions in the PK and RR domains of ICP10, respectively, and the revertant virus HSV-2(R) have been described previously (75). HSV-1 mutants ICP6Δ, which is deleted in the R1 (also known as the ICP6) coding sequence, and hrR3, which retains only 38% of the N-terminal domain, were obtained from Sandra K. Weller (University of Connecticut Health Center, Farmington). Their generation and properties have been described (31, 32). The expression vectors for ICP10 and its PK-negative mutant p139 (pJW17 and pJHL15, respectively) have been described (16, 55, 66, 73, 76). The Flag-Raf1 expression vector for the c-Raf-1 dominant negative mutant protein K375M (18, 78) was obtained from Bernard Weinstein (Columbia University, New York). Expression vector pJG4-5 mBag-1, for the murine Bag-1 protein (79), was purchased from Science Reagents Inc (Atlanta, Ga.).

Cells, virus infection, and plasmid transfection.

Vero (African green monkey kidney) cells were grown in minimal essential medium with 10% fetal bovine serum and 100 U of penicillin-streptomycin (Gibco-BRL, Gaithersburg, Md.) per ml and used for virus growth (73-76). Primary cultures of central nervous system neurons were established as previously described (1, 66). Cells dissociated from the hippocampi or cerebral cortex of 16- to 19-day-old rat fetuses (Sprague-Dawley) were plated at a density of approximately 750,000/2 ml on collagen-coated 35-mm dishes (Nunc, Rochester, N.Y.) or glass coverslips coated with poly-l-lysine (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.). The studies described in this report were done with 6-day-old cultures in which >88% of the cells were postmitotic neurons, as determined with the 5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine labeling and detection kit (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Indianapolis, Ind.) and staining with class III β-tubulin (TUJ1) antibody (23).

Virus infection was done with 10 PFU/cell in medium containing 10% horse serum, a condition that allows growth of the mutants in nonneuronal cells (31, 32, 75, 76). After adsorption for 1 h at 36.5°C, the virus inoculum was removed, and the cultures were overlaid with growth medium (66). Transient transfection was performed as previously described (66, 67) with the FuGene 6 transfection reagent (Roche Molecular Biochemicals) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Antibodies.

TUJ1 antibody was the gift of Paul Yarowsky (University of Maryland, Baltimore). The Flag monoclonal antibody M2 was purchased from Cayman Chemicals, Ann Arbor, Mich. The polyclonal antibody to ICP10 was described previously. It recognizes amino acids 13 to 26 on ICP10 and p139 but does not recognize HSV-1 proteins (3, 16, 55, 66, 73-76). The following polyclonal antibodies were purchased and used according to the manufacturer's instructions: antibodies to cleaved caspase-3 (D175; recognizes the 17- to 20-kDa fragment of the active caspase (63, 66, 67) (caspase3p20) (Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, Mass.); cleaved poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase [recognizes the 85-kDa fragment of caspase-cleaved poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (p85PARP) (17, 66, 69) as confirmed in our laboratory (data not shown) (Promega, Madison, Wis.)]; phosphorylated JNK [recognizes the dually phosphorylated form of JNK1/2/3 (Promega), actin, Bcl-2 (ΔC21), and Bag-1 (FL-274) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, Calif.)]; antibodies to c-Jun phosphorylated on Ser63 [P-Jun(Ser63)] or Ser73 [P-Jun(Ser73)] and nonphosphorylated c-Jun [part of the PhosphoPlus c-Jun(Ser63) II c-Jun(Ser73) antibody kit]; antibodies to CREB phosphorylated on Ser133 and nonphosphorylated CREB [part of the PhosphoPlus CREB(Ser133) antibody kit]; and antibody to ATF-2 phosphorylated on Thr69/71 (phosphorylated ATF-2) were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology.

Chemicals.

The c-Raf-1 kinase inhibitor I (52) and the JNK inhibitor SP600125 (7, 36) were purchased from Calbiochem (La Jolla, Calif.). The MEK-specific inhibitor U0126 (22) was purchased from Promega.

Hoechst staining.

Cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (pH 7.4), permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100, and stained with the fluorescent DNA-binding dye Hoechst 32258 (66).

In situ cell death detection.

The in situ cell death detection kit (Roche Molecular Biochemicals) was used according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.4) for 1 h at room temperature, followed by permeabilization in 0.1% Triton X-100 (in 0.1% sodium citrate) for 2 min on ice. DNA breaks were labeled by addition of terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase and nucleotide mixture containing fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated dUTP, and incubation was continued for 60 min at 37°C. Coverslips were mounted in phosphate-buffered saline-glycerol, and cells were analyzed by fluorescence microscopy. After extensive washes in phosphate-buffered saline, cells were incubated for 30 min at 37°C with an anti-fluorescein isothiocyanate antibody conjugated with alkaline phosphatase.

Chromogenic reaction was carried out by adding alkaline phosphatase substrate solution containing 0.4 mg of nitroblue tetrazolium chloride per ml and 0.2 mg of 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolylphosphate toluidine salt (Roche Molecular Biochemicals) per ml in 0.1 M Tris-HCl (pH 9.5)-0.05 M MgCl2-0.1 M NaCl-1 mM levamisole for 10 min at room temperature. Coverslips were mounted in phosphate-buffered saline-glycerol and analyzed by light microscopy. Apoptotic cells (characterized by a dark nuclear precipitate) and nonapoptotic cells (unstained or displaying a diffuse, light, and uneven cytoplasmic staining) were counted in five randomly chosen microscopic fields (containing at least 250 cells). Results are expressed as percent apoptotic cells ± standard error of the mean.

Caspase activation.

The CaspACE fluorescein isothiocyanate Val-Ala-Asp-fluoromethylketone (VAD-FMK) in situ marker (Promega) was used according to the manufacturer's instructions. Cells were treated with the fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated permeable irreversible caspase inhibitor VAD-FMK for 20 min to allow binding to activated caspases. Cells were subsequently fixed with 10% buffered formaldehyde (1 h, room temperature) and visualized by fluorescence microscopy.

Immunofluorescence and immunohistochemistry.

The identity of the terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase-mediated dUTP-biotin nick-end labeling (TUNEL)-positive cells in primary hippocampal cultures was determined by double immunofluorescence, as previously described (66). Briefly, the cultures were incubated with terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase and the nucleotide mixture (containing fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated dUTP) for 1 h at 37°C and stained (1 h, room temperature) with TUJ1 antibody followed by phycoerythrin-conjugated anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (30 min, room temperature). Stained cells were visualized with an epifluorescent confocal microscope fitted with an argon ion laser (Zeiss LSM 410).

The Dako LSAB 2 kit horseradish peroxidase (Dako Corporation, Carpinteria, Calif.) was used for immunoperoxidase staining. Cultures were exposed overnight (4°C) to primary antibodies (caspase 3 p20, phosphorylated JNK, Flag, or p85PARP), and immunolabeled cells were subsequently detected with the streptavidin-biotin method according to the manufacturer's instructions. Counterstaining was done with Mayer's hematoxylin (Sigma) (66, 67). Five randomly chosen microscopic fields (containing at least 250 cells) were counted, and the percentage of mock-infected positive cells was subtracted from each average. Results are expressed as percent positive cells ± standard error of the mean.

Immunoblotting.

Immunoblotting was done as previously described (55, 66, 73-76). Briefly, cells were lysed with radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4], 0.15 mM NaCl, 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate) supplemented with phosphatase and protease inhibitor cocktails (Sigma) and sonicated for 30 s at 25% output power with the Sonicator ultrasonic processor (Misonix, Inc., Farmingdale, N.Y.). Total protein was determined by the bicinchoninic assay (Pierce, Rockford, Ill.), and proteins were resolved by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. The blots were incubated (1 h, 37°C) in TN-T buffer (0.01 M Tris-HCl [pH 7.4], 0.15 M NaCl, 0.05% Tween 20) containing 1% bovine serum albumin to block nonspecific binding and exposed overnight at 4°C to the appropriate antibodies diluted in TN-T buffer with 0.1% bovine serum albumin. After three washes with TN-T buffer, the blots were incubated with protein A-peroxidase for 1 h at room temperature. Detection was done with the ECL kit reagents (Amersham Life Science, Arlington Heights, Ill.) and exposure to high-performance chemiluminescence film (Hyperfilm ECL; Amersham). Quantitation was done by densitometric scanning with the Bio-Rad GS-700 imaging densitometer.

Statistical analyses.

Student's t test and analysis of variance with the Tukey-Kramer posttest were performed with GraphPad InStat version 3.01 for Windows 95/NT (GraphPad Software, San Diego, Calif.).

RESULTS

HSV-2 but not HSV-1 blocks apoptosis in primary cultures of central nervous system neurons.

We have previously shown that the HSV-2 ICP10 PK blocks apoptosis in hippocampal neurons (66, 67). To determine whether this activity is shared by HSV-1 and extends to other types of neurons, primary hippocampal and cerebral cortical cultures were mock-infected or infected with 10 PFU of HSV-1, HSV-2, ICP10ΔPK, or ICP10ΔRR per cell and assayed by TUNEL [widely accepted to be specific for apoptosis (28, 30)] at 24 h postinfection.

In both hippocampal (Fig. 1A) and cerebral cortex (Fig. 1B) cultures, the percentage of TUNEL-positive (apoptotic) cells was significantly higher for HSV-1 (49.4 ± 4.5 and 44.8 ± 3.6%, respectively) and ICP10ΔPK (61.6 ± 6.1 and 47.5 ± 2.5%, respectively) than HSV-2 (5.7 ± 3.2% and 17.9 ± 2%, respectively) or ICP10ΔRR (19.7 ± 2 and 23.5 ± 1.2%, respectively). Hoechst staining of HSV-1-infected cells evidenced nuclear fragmentation characteristic of apoptosis (Fig. 1C) that was similar to that described previously for ICP10ΔPK (66) and was not seen in HSV-2-infected cells (Fig. 1D).

FIG. 1.

ICP10 PK blocks and HSV-1 triggers apoptosis in central nervous system neurons. (A) Hippocampal cultures were mock infected or infected with HSV-1, HSV-2, ICP10ΔPK, or ICP10ΔRR (multiplicity of infection, 10) and analyzed by TUNEL at 24 h postinfection, as described in Materials and Methods. Results represent the average of three independent experiments and are expressed as mean percent apoptotic cells ± standard error of the mean. The number of apoptotic cells in mock-infected cultures (>10%) was subtracted from each average. *, P < 0.01 versus HSV-2 or ICP10ΔRR; +, P < 0.05 versus HSV-2 by analysis of variance. (B) Cortical cultures were mock infected or infected with HSV-1, HSV-2, ICP10ΔPK, or ICP10ΔRR and analyzed by TUNEL as in A. **, P < 0.05 versus HSV-2 or ICP10ΔRR by analysis of variance). (C and D) Hoechst staining of representative nuclei from HSV-1-infected (C) and HSV-2-infected (D) cultures. (E and F) Hippocampal cultures infected with HSV-1 (E) or HSV-2 (F) were assayed by TUNEL and stained with TUJ1 antibody. Colocalization was seen only for HSV-1.

TUNEL-positive cells were neurons, because they stained with the neuron-selective TUJ1 antibody. The TUJ1 signal (phycoerythrin) was found in the cell bodies and projections, while the fluorescein isothiocyanate signal (TUNEL) was primarily nuclear (Fig. 1E). Mock- and HSV-2-infected neurons (TUJ1 positive) were mostly TUNEL negative (Fig. 1F). The data indicate that HSV-1 triggers and ICP10 PK blocks apoptosis in both hippocampal and cerebral cortex neurons that differ in their response to other apoptotic (85) and survival (43) stimuli. By contrast, the percentage of TUNEL-positive cells was higher for ICP10ΔRR than HSV-2 only in hippocampal cultures, suggesting that the contribution of ICP10 RR to HSV-2 antiapoptotic activity (66) is neuron-type specific.

HSV-1 and ICP10ΔPK activate caspase-3 and induce poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase cleavage.

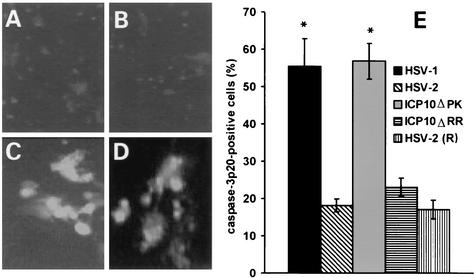

Primary hippocampal cultures mock-infected or infected with HSV-1, HSV-2, ICP10ΔPK, or ICP10ΔRR (multiplicity of infection, 10) were reacted with fluorescein isothiocyanate-VAD-FMK, which binds to the active sites of caspases 3, 6, and 7 (12), and examined by fluorescence microscopy. The fluorescein isothiocyanate signal was seen in 40 to 60% of the cells in cultures infected with HSV-1 (Fig. 2C) or ICP10ΔPK (Fig. 2D), compared to 10 to 20% of the cells in mock-infected cultures (data not shown) or cultures infected with HSV-2 (Fig. 2A) or ICP10ΔRR (Fig. 2B). We conclude that the higher percentage of signal-positive cells in HSV-1- and ICP10ΔPK-infected cultures is due to caspase 3 activation, because similar results were obtained by staining with caspase 3 p20 antibody, which is specific for activated caspase 3, and with p85PARP antibody, which is specific for cleaved poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase.

FIG. 2.

ICP10 PK blocks and HSV-1 triggers caspase 3 activation. Primary hippocampal cultures infected with 10 PFU of HSV-2 (A), ICP10ΔRR (B), HSV-1 (C), or ICP10ΔPK (D) per cell were treated with fluorescein isothiocyanate-VAD-FMK at 24 h postinfection and examined by fluorescence microscopy. (E) Hippocampal cultures infected as above or with HSV-2(R) were stained with caspase 3 p20 antibody by immunohistochemistry, and cells in five randomly chosen microscopic fields were counted. The number of positive cells in mock-infected cultures (>10%) was subtracted from each average, and the results (average of three independent experiments) are expressed as mean percent caspase 3 p20-positive cells ± standard error of the mean. *, P < 0.05 by analysis of variance. Normal rabbit serum was negative.

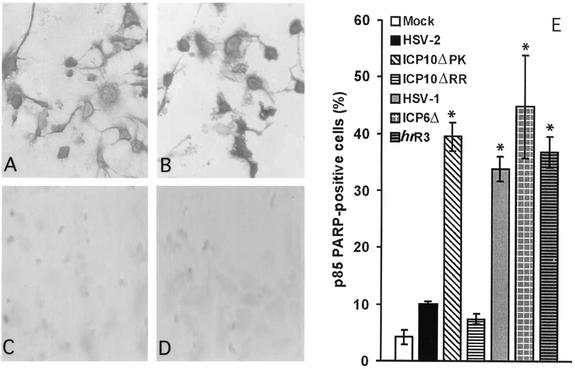

Indeed, the percentage of caspase 3 p20-positive cells was significantly higher for HSV-1 (55.4 ± 7.4%) and ICP10ΔPK (56.8 ± 4.8%) than HSV-2 (18.1 ± 1.7%), ICP10ΔRR (23 ± 2.4%), or the revertant virus HSV-2(R) (17 ± 2.5%) (Fig. 2E). The percentage of p85PARP-positive cells was also significantly higher for HSV-1 (33.8 ± 2.2%) and ICP10ΔPK (39.5 ± 2.5%) than HSV-2- (9.9 ± 0.2%), ICP10ΔRR- (7.4 ± 0.9%), or mock-infected cells (4.2 ± 1.3%) (P < 0.001 by analysis of variance) (Fig. 3E). As reported previously (17), p85PARP staining was primarily but not exclusively intranuclear for both HSV-1 (Fig. 3A) and ICP10ΔPK (Fig. 3B). HSV-2- (Fig. 3C), ICP10ΔRR- (Fig. 3D), and HSV-2(R)- (data not shown) infected cultures were essentially negative. The percentage of p85PARP-positive cells was similar for HSV-1 (33.8 ± 2.2%), ICP6Δ (44.8 ± 9.1%), and hrR3 (36.8 ± 2.7%) (Fig. 3E), indicating that ICP6, the HSV-1 homologue of ICP10, is not involved in apoptosis modulation.

FIG. 3.

Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase cleavage is induced by HSV-1 and blocked by ICP10 PK. (A to D). Hippocampal cultures were infected with 10 PFU of HSV-1 (A), ICP10ΔPK (B), HSV-2 (C), or ICP10ΔRR (D) per cell and stained with p85PARP antibody by immunohistochemistry. (E) Cells infected as above or with ICP6Δ or hrR3 and mock-infected cells were stained with p85PARP antibody, and the results (average of three independent experiments) are expressed as percent p85PARP-positive cells ± standard error of the mean. *, P < 0.001 versus mock-, HSV-2-, and ICP10ΔRR-infected cells by analysis of variance. Normal rabbit serum was negative.

Ectopically delivered ICP10 PK protects from HSV-1- or ICP10ΔPK-induced apoptosis.

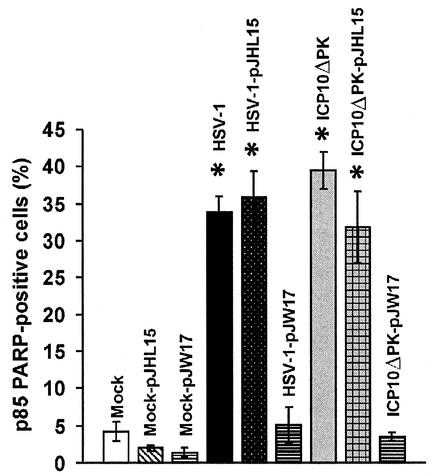

To examine whether ICP10 PK overrides the apoptotic signal induced by HSV-1 or ICP10ΔPK in the absence of any other HSV-2 proteins, hippocampal cultures were transfected with the expression vectors for ICP10 (pJW17) or its PK-negative mutant p139 (pJHL15) and infected with HSV-1 or ICP10ΔPK (multiplicity of infection, 10) at 48 h after transfection to allow transgene expression. They were stained with p85PARP antibody 24 h later (72 h after transfection), and the percentage of staining cells was calculated as described in Materials and Methods. Cultures similarly transfected with pJW17 or pJHL15 were mock-infected with growth medium and studied in parallel.

Uninfected cultures were essentially negative, whether untransfected (4.2 ± 1.3%) or transfected with pJW17 (1.4 ± 0.4%) or pJHL15 (2 ± 0.4%) (P > 0.05 by analysis of variance). HSV-1 infection increased the percentage of p85PARP-positive cells in untransfected cultures (33.8 ± 2.2%) and in cultures transfected with pJHL15 (35.9 ± 3.5%) but not with pJW17 (5.1 ± 2.4%) (P < 0.001 by analysis of variance). Similar results were obtained for ICP10ΔPK (Fig. 4) and by TUNEL (data not shown). The data indicate that ICP10 PK protects from apoptosis induced by HSV-1 or ICP10ΔPK by a kinase-dependent mechanism which does not require other HSV-2 proteins. Significantly, however, the percentage of cells staining with ICP10 antibody (28 to 35% for both pJW17 and pJHL15) was approximately threefold lower than the reduction (approximately 85%) in apoptotic cells seen in pJW17-transfected cultures. Because postmitotic neurons in primary culture extend processes, form synapses with one another, are electrically active, and secrete and respond to neurotransmitters (5, 13, 44, 62, 65), the data suggest that ICP10 PK-transfected neurons synthesize and secrete neurotrophins and/or form synapses that promote the survival of surrounding neurons.

FIG. 4.

Ectopically delivered ICP10 PK protects from ICP10ΔPK- or HSV-1-triggered apoptosis. Primary hippocampal cultures were transfected with pJW17 or pJHL15, expressing ICP10 and its PK-negative mutant p139, respectively, and mock infected or infected with HSV-1 or ICP10ΔPK (multiplicity of infection, 10) at 48 h after transfection. Twenty four hours later, cultures were stained with p85PARP antibody. Results (average of three independent experiments) are percent p85PARP-positive cells ± standard error of the mean. *, P < 0.001 versus mock- infected untransfected, mock-infected pJW17-transfected, ICP10ΔPK-infected pJW17-transfected, and HSV-1-infected pJW17-transfected cultures by analysis of variance.

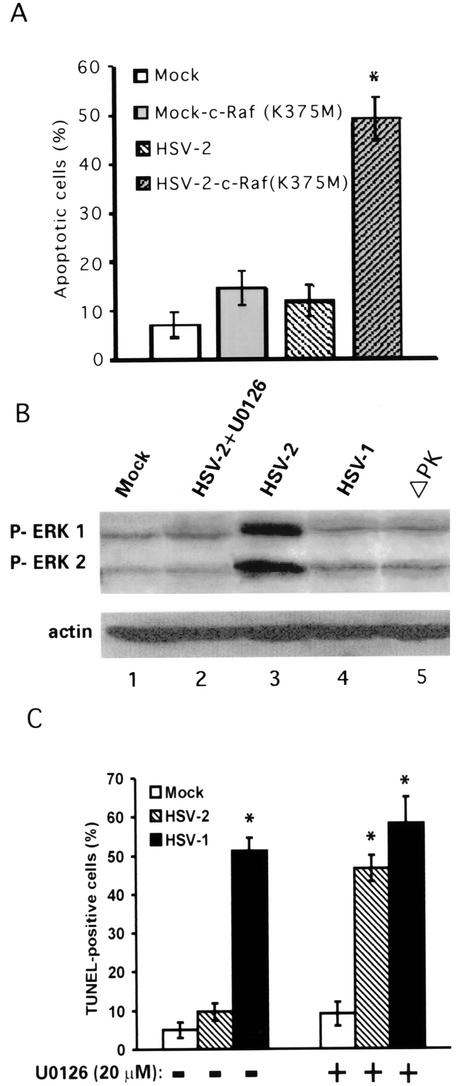

HSV-2 antiapoptotic activity is Raf dependent and involves activation of MEK/ERK.

Two series of experiments were done to further investigate factors involved in the ability of ICP10 PK to block apoptosis. First, we took advantage of previous findings that the Flag-Raf1 K375M protein is a dominant negative mutant that inhibits the kinase activity of its endogenous c-Raf-1 counterpart (18, 78) in order to examine whether antiapoptotic activity is Raf dependent. Primary hippocampal cultures were transfected or not with the Flag-Raf1 K375M expression vector. Twenty-four hours later, duplicate cultures were examined for transgene expression by staining with Flag antibody or infected with HSV-2 (multiplicity of infection, 10) and examined by TUNEL at 24 h after virus infection (48 h posttransfection). Cultures transfected or not with Flag-Raf1 K375M and mock-infected with growth medium served as the control.

The percentage of TUNEL-positive (apoptotic) cells in untransfected cultures infected with HSV-2 (11.8 ± 3.2%) was similar to that seen in untreated cultures (7.1 ± 2.6%). It was significantly (P < 0.01 by analysis of variance) increased in HSV-2-infected cells that had been transfected with Flag-Raf1 K375M (49.0 ± 4.3), but not in similarly transfected mock-infected cells (14.5 ± 3.5%), although the same proportion of cells stained with Flag antibody (36 ± 2.2% and 33.7 ± 3.6%, respectively) (Fig. 5A). Ongoing studies indicate that c-Raf-1 kinase activity is inhibited by Flag-Raf1 K375M transfection and by treatment with the pharmacologic inhibitor of c-Raf-1 kinase (c-Raf-1 kinase inhibitor I), which also causes a significant increase in the percentage of TUNEL-positive cells in HSV-2- but not ICP10ΔPK-infected cultures (unpublished data).

FIG. 5.

HSV-2 antiapoptotic activity is Raf/MEK/ERK dependent. (A) Hippocampal cultures were transfected with Flag-Raf1-K375M (expresses a c-Raf-1 dominant negative mutant). Twenty four hours later, they were mock infected or infected with HSV-2 and assayed by TUNEL at 24 h after virus infection. Results represent the average of three independent experiments and are expressed as percent TUNEL-positive cells ± standard error of the mean. *, P < 0.001 versus mock-infected untransfected, mock-infected K375M-transfected, and HSV-2-infected cultures by analysis of variance. (B) Hippocampal cultures were mock infected (lane 1) or infected with HSV-2 in the presence (lane 2) or absence (lane 3) of 20 μM U0126 or with HSV-1 (lane 4) or ICP10ΔPK (lane 5) and immunoblotted with antibody to phosphorylated-ERK1/2. They were striped and reprobed with actin antibody. (C) Hippocampal cultures were mock infected or infectedwith HSV-2 or HSV-1 in the absence (−) or presence (+) of 20 μM U0126 and assayed by TUNEL at 24 h postinfection The results of three independent experiments are expressed as mean percent TUNEL-positive cells ± standard error of the mean. *, P < 0.001 by analysis of variance.

The data suggest that Raf kinase is involved in HSV-2 (ICP10 PK) antiapoptotic activity, but it is still unclear whether kinase activity is increased by HSV-2 infection. The higher percentage of neurons undergoing apoptosis than that staining with Flag antibody presumably reflects the release of glutamate by the transfected (apoptotic) neurons and its ability to trigger apoptosis in surrounding neurons (44, 62, 65).

In a second series of experiments, we asked whether the antiapoptotic activity of ICP10 PK is MEK/ERK dependent. Hippocampal cultures were mock-infected with growth medium or infected with 10 PFU of HSV-2 per cell in the absence or presence of 20 μM U0126, a MEK-specific inhibitor (22), and examined for ERK activation (phosphorylation) at 0.5 h postinfection and by TUNEL at 24 h postinfection, as previously described (66). Cultures infected with ICP10ΔPK or HSV-1 (10 PFU/cell) were studied in parallel. Relative to mock-infected cultures (Fig. 5B, lane 1), the levels of phosphorylated (activated) ERK (P-ERK1/2) were significantly increased in cultures infected with HSV-2 (Fig. 5B, lane 2) but not HSV-2 with U0126 (Fig. 5B, lane 3), HSV-1 (Fig. 5B, lane 4), or ICP10ΔPK (Fig. 5B, lane 5). U0126 treatment caused a significant increase in the percentage of TUNEL-positive cells in HSV-2- but not mock-infected cultures (9 ± 1% and 49 ± 3.8%, respectively) (Fig. 5C). Collectively, the data confirm and extend previous findings (66) that activation of the ERK survival pathway is required for HSV-2 (ICP10 PK) antiapoptotic activity but not for the survival of uninfected hippocampal neurons.

ERK survival pathway activated by ICP10 PK induces Bag-1 expression.

The exact relationship between activated survival pathways and antiapoptotic Bcl-2 family proteins is still poorly understood. To determine whether activation of the ERK pathway results in increased expression of antiapoptotic proteins, we focused on Bag-1, which has neuroprotective activity (39) and inhibits apoptosis by itself or by cooperating with the antiapoptotic protein Bcl-2 (9, 72, 79). Bag-1 also binds c-Raf-1 and activates its kinase activity (82), thereby providing a potential positive feedback loop for the ERK survival pathway.

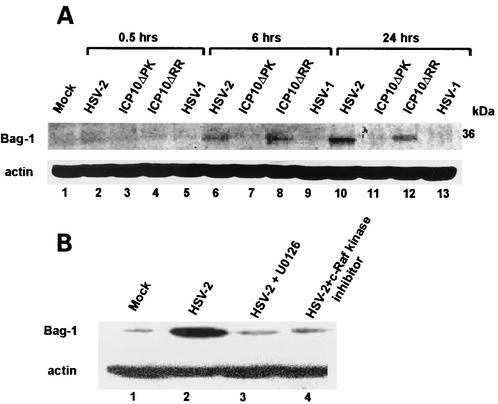

Hippocampal cultures were mock-infected or infected with 10 PFU of HSV-1, HSV-2, ICP10ΔPK, or ICP10ΔRR per cell and examined for Bag-1 expression by immunoblotting with specific antibody at 0.5, 6, and 24 h postinfection. These time points were selected because ERK is activated within 30 min postinfection with HSV-2, but TUNEL-positive cells are seen at 12 to 24 h postinfection. Bag-1 was not seen in mock-infected cultures (Fig. 6A, lane 1) or at 0.5 h postinfection (Fig. 6A, lanes 2 to 5). At 6 and 24 h postinfection, Bag-1 was seen in cultures infected with HSV-2 (Fig. 6A, lanes 6 and 10) or ICP10ΔRR (Fig. 6A, lanes 8 and 12) but not ICP10ΔPK (Fig. 6A, lanes 7 and 11) or HSV-1 (Fig. 6A, lanes 9 and 13), indicating that it is induced by ICP10 PK. We conclude that Bag-1 is upregulated by the activated ERK pathway, because its levels were not increased in cultures infected with HSV-2 in the presence of the MEK-specific inhibitor U0126 (20 μM) (Fig. 6B, lane 3) or the c-Raf-1 kinase-specific inhibitor c-Raf kinase inhibitor I (50 μM) (Fig. 6B, lane 4). Actin levels were identical in all cultures (Fig. 6).

FIG. 6.

ICP10 PK induces Bag-1 expression by activating the ERK survival pathway. (A) Primary hippocampal cultures were mock infected or infected with 10 PFU of HSV-1, HSV-2, ICP10ΔPK or ICP10ΔRR per cell for the indicated times. Proteins were resolved by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and immunoblotted with Bag-1 antibody. Blots were stripped and reprobed with actin antibody. (B) Cultures were mock infected or infected with HSV-2 in the absence or presence of U0126 (20 μM) or Raf-1 kinase inhibitor I (50 μM) and immunoblotted with Bag-1 or actin antibodies as in A.

Ectopically expressed Bag-1 inhibits HSV-1- and ICP10ΔPK-induced apoptosis.

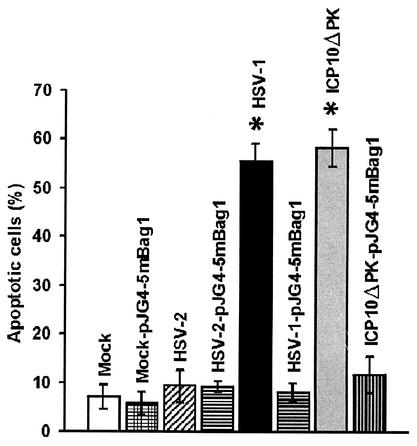

To test the hypothesis that Bag-1 is involved in the ability of ICP10 PK to inhibit apoptosis caused by HSV-1 or ICP10ΔPK, hippocampal cultures were transfected or not with an expression vector for Bag-1 (pJG4-5m Bag-1) and mock-infected or infected with 10 PFU of HSV-2, HSV-1, or ICP10ΔPK per cell 24 h later. Cultures were examined by TUNEL at 24 h after virus infection (48 h posttransfection), and the percentage of positive cells was determined as described in Materials and Methods.

Transfection did not modify the percentage of TUNEL-positive cells in uninfected cultures (5.8 ± 2.4% and 7.1 ± 2.5% for transfected and untransfected cells, respectively) or HSV-2-infected cultures (9.2 ± 1.0% and 9.3 ± 3.3% for transfected and untransfected cells, respectively). However, the percentage of TUNEL-positive cells in cultures infected with ICP10ΔPK (58.2 ± 3.8%) or HSV-1 (55.5 ± 3.6%) was significantly reduced by Bag-1 transfection (11.8 ± 2.5% and 8.1 ± 1.8% for ICP10ΔPK and HSV-1, respectively) (P < 0.001 by analysis of variance) (Fig. 7), and similar results were obtained by staining with p85PARP antibody (data not shown). The data indicate that Bag-1 is involved in the antiapoptotic activity of ICP10 PK. Furthermore, as with ICP10 PK, Bag-1 transfection had a bystander trophic effect exemplified by the higher reduction in TUNEL-positive cells (approximately 80%) than Bag-1 staining cells (38 to 45%).

FIG. 7.

Ectopically delivered Bag-1 inhibits virus-induced apoptosis. Hippocampal cultures were transfected with pJG4-5mBag-1 and mock infected or infected with 10 PFU of HSV-2, ICP10ΔPK, or HSV-1 per cell 24 h later. They were assayed by TUNEL at 24 h after infection. Nontransfected but similarly infected cultures were studied in parallel. Results (average of three independent experiments) are expressed as percent apoptotic cells ± standard error of the mean. *, P < 0.001 versus transfected and infected (mock, HSV-1, HSV-2, and ICP10ΔPK) and versus nontransfected and infected (mock and HSV-2) by analysis of variance.

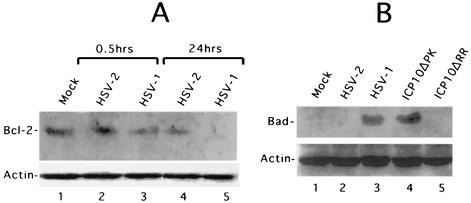

ICP10 PK increases Bcl-2 stability and inhibits BAD expression.

Having seen that ICP10 PK induces Bag-1 expression, we wanted to know whether it also modulates Bcl-2, which interacts with Bag-1 (79), is associated with neuroprotection (39), and is proteolytically inactivated by other apoptosis-inducing viruses (33). Hippocampal cultures were mock-infected or infected with 10 PFU of HSV-2, or HSV-1 per cell and immunoblotted with Bcl-2 antibody at 0.5 and 24 h postinfection. Bcl-2 levels were essentially similar in mock- (Fig. 8A, lane 1) and HSV-2-infected cultures at 0.5 h postinfection (Fig. 8A, lane 2) and 24 h postinfection (Fig. 8A, lane 4). They were slightly lower in HSV-1-infected cultures at 0.5 h postinfection (Fig. 8A, lane 3) and no longer visible at 24 h postinfection (Fig. 8A, lane 5). Similar results were obtained for ICP10ΔPK (data not shown), but actin levels were identical in all samples.

FIG. 8.

ICP10 PK stabilizes Bcl-2 and inhibits BAD expression. (A) Extracts of hippocampal cultures mock infected or infected with HSV-1 or HSV-2 for the indicated times were immunoblotted with antibodies to Bcl-2 followed by actin. The apparent flaw in lane 5 is an artifact not seen in the other blots. (B) Extracts of hippocampal cultures mock infected or infected with HSV-2, ICP10ΔPK, ICP10ΔRR, or HSV-1 (multiplicity of infection, 10) for 0.5 h were immunoblotted with BAD and actin antibodies.

By contrast to Bcl-2, the proapoptotic protein BAD, which is associated with glutamate-induced neuronal apoptosis and neurodegenerative disorders (50, 84, 88), was not expressed in mock-infected cells (Fig. 8B, lane 1). Its expression was rapidly induced (within 30 min) by infection with HSV-1 (Fig. 8B, lane 3) or ICP10ΔPK (Fig. 8B, lane 4) and was no longer detected at 24 h postinfection (data not shown). BAD expression was not induced by HSV-2 (Fig. 8B, lane 2) or ICP10ΔRR (Fig. 8B, lane 5) at any time postinfection (0.5 to 24 h). We interpret the data to indicate that Bcl-2 is stabilized in HSV-2- but not HSV-1- (or ICP10ΔPK)-infected cells and that ICP10 PK blocks BAD upregulation.

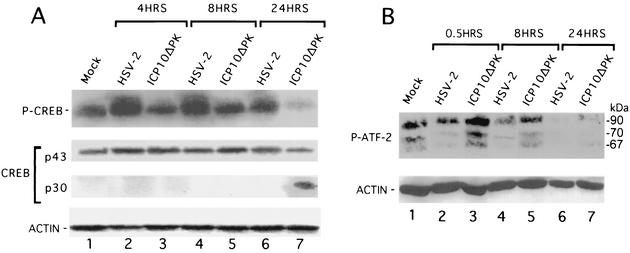

ICP10 PK activates or stabilizes CREB and blocks ATF-2 activation.

Activated ERK promotes cell survival by transcription-dependent (induction of survival genes) or -independent (Bcl-2 phosphorylation [10]) mechanisms. Because ICP10 PK induces Bag-1 expression by an ERK-dependent mechanism, we reasoned that its ability to block apoptosis is primarily transcription dependent. Two series of experiments were done to begin testing this interpretation. In the first series, we focused on CREB, which is the primary Bcl-2 transcriptional activator (70) and is involved in neurotrophin-mediated gene transcription associated with neuronal survival (24). Hippocampal cultures were mock-infected or infected with 10 PFU of HSV-2 or ICP10ΔPK per cell and immunoblotted with antibodies specific for phosphorylated CREB or nonphosphorylated CREB at 4, 8, and 24 h postinfection.

Phosphorylated CREB was seen in mock-infected cultures (Fig. 9A, lane 1), but its levels were significantly increased in HSV-2-infected cultures at 4 h (Fig. 9A, lane 2) and 8 h (Fig. 9A, lane 4) postinfection, and they were still somewhat increased at 24 h postinfection (Fig. 9A, lane 6). Phosphorylated CREB levels were not increased in ICP10ΔPK-infected cultures at 4 and 8 h postinfection (Fig. 9A, lanes 3 and 5), and they were significantly decreased at 24 h postinfection (Fig. 9A, lane 7). This decrease was accompanied by the appearance of a 30-kDa nonphosphorylated species (p30) (Fig. 9A, lane 7), which is consistent with a previously reported fragment generated by caspase 3-mediated cleavage (25).

FIG. 9.

ICP10 PK activates and stabilizes CREB and inhibits ATF-2 activation. (A) Hippocampal cultures were mock infected or infected with 10 PFU of HSV-2 or ICP10ΔPK per cell for the indicated times, and cell extracts were immunoblotted with phosphorylated CREB antibody followed by antibodies for total CREB and actin. (B) Hippocampal cultures mock infected or infected with 10 PFU of HSV-2 or ICP10ΔPK per cell for the indicated times were immunoblotted with phosphorylated ATF-2, followed by actin antibodies.

In a second series of experiments to examine the effect of infection on transcription factors, we asked whether ATF-2 (also known as CRE-BP) is activated (phosphorylated on Thr69/71) in virus-infected hippocampal cultures. We focused on ATF-2 because it is activated by the JNK apoptotic pathway in response to stress stimuli (34). Extracts of hippocampal cultures, mock-infected or infected with HSV-2 or ICP10ΔPK (multiplicity of infection, 10) for 0.5, 8, or 24 h, were immunoblotted with antibody to phosphorylated ATF-2. Consistent with previous reports (40), a major 72- to 74-kDa band and a smaller 67- to 68-kDa band were seen in mock-infected cultures (Fig. 9B, lane 1). Their levels decreased in cultures infected with HSV-2 (Fig. 9B, lanes 2, 4, and 6) and increased in those infected with ICP10ΔPK (Fig. 9B, lanes 3 and 5), in which a 60-kDa band was also evident. Phosphorylated ATF-2 was no longer detected at 24 h postinfection with either virus (Fig. 9B, lanes 6 and 7), and actin levels were similar in all samples (Fig. 9B). Collectively, the data indicate that ICP10 PK activates and stabilizes CREB while it inhibits ATF-2 activation. The role of signaling pathways in these alterations remains to be documented.

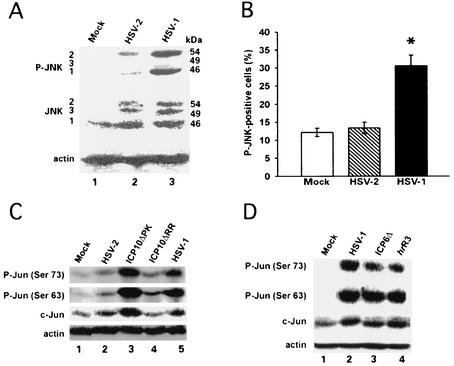

ICP10ΔPK and HSV-1 activate the JNK/c-Jun pathway in hippocampal cultures.

HSV-1 was previously shown to activate JNK/c-Jun in nonneuronal cells (57, 90, 91). Having seen that HSV-1 and ICP10ΔPK upregulate BAD and activate ATF-2, both of which are targets of the apoptotic JNK/c-Jun pathway (11, 12, 34, 81), we wanted to know whether JNK/c-Jun activation is associated with apoptosis triggered by these viruses (i.e., in the absence of ICP10 PK). Two series of experiments were done. First, hippocampal cultures were mock infected or infected with 10 PFU of HSV-1 or HSV-2 per cell and examined for JNK activation at 24 h postinfection by immunoblotting with phosphorylated JNK antibody (recognizes phosphorylated JNK1/2/3). Antibody to nonphosphorylated JNK1/2/3 was used as a control.

JNK1 was the only isotype expressed in mock-infected cultures (Fig. 10A, lane 1). In most experiments, it was not phosphorylated (Fig. 10A, lane 1), but minimal (barely detectable) levels of phosphorylated JNK1 were observed in rare experiments (data not shown). Both HSV-2 (Fig. 10A, lane 2) and HSV-1 (Fig. 10A, lane 3) induced expression of JNK2/3. However, while the levels of phosphorylated JNK1/2 in HSV-2-infected cultures were low (Fig. 10A, lane 2), JNK1 and -2 were intensely phosphorylated (activated) in HSV-1-infected cultures (Fig. 10A, lane 3). Actin levels were virtually identical in all extracts (Fig. 10A), indicating that these results are not an artifact due to improper gel loading or other technical problems. The percentage of cells staining with phosphorylated JNK antibody was also significantly (P < 0.05 by analysis of variance) higher for HSV-1- than mock- or HSV-2-infected cultures as early as 0.5 h postinfection (Fig. 10B).

FIG. 10.

JNK and c-Jun are activated by HSV-1 and ICP10ΔPK. (A) Extracts of hippocampal cultures mock infected or infected with 10 PFU of HSV-2 or HSV-1 per cell for 24 h were immunoblotted with phosphorylated JNK antibody, followed by antibodies to JNK and actin. Barely visible levels of phosphorylated JNK1/2 were rarely seen in the mock-infected cultures. (B) Cultures were mock infected or infected with HSV-2 or HSV-1 (multiplicity of infection, 10) and stained with phosphorylated JNK antibody at 0.5 h postinfection Results (average of three independent experiments) are mean percent phosphorylated JNK-positive cells ± standard error of the mean. *, P < 0.05 versus mock-infected or HSV-2-infected cultures by analysis of variance. Normal rabbit serum was negative. (C) Extracts of cells infected with HSV-1, HSV-2, ICP10ΔPK, or ICP10ΔRR (multiplicity of infection, 10) or mock infected for 24 h were immunoblotted with antibodies specific for P-Jun(Ser73), followed by P-Jun(Ser63), c-Jun, and actin. (D) Extracts of cells infected with HSV-1, ICP6Δ, or hrR3 or mock infected for 24 h were immunoblotted as in C.

In a second series of experiments, hippocampal cultures were mock infected or infected (24 h, 10 PFU/cell) with HSV-1, HSV-2, ICP10ΔPK, or ICP10ΔRR and assayed for c-Jun activation by immunoblotting with antibody to c-Jun phosphorylated on Ser63 [P-Jun(Ser63)] or Ser73 [P-Jun(Ser73)], both of which are phosphorylated by phosphorylated JNK (59). Antibody to nonphosphorylated c-Jun was studied in parallel and served as a control. The levels of P-Jun(Ser63) and P-Jun(Ser73) were significantly increased in HSV-1-infected (Fig. 10C, lane 5) and ICP10ΔPK-infected (Fig. 10C, lane 3) relative to mock-infected (Fig. 10C, lane 1) cultures. They were minimally increased in HSV-2-infected (Fig. 10C, lane 2) or ICP10ΔRR-infected (Fig. 10C, lane 4) cultures. Actin levels were virtually identical in all cultures.

The levels of nonphosphorylated c-Jun were also increased in HSV-1- and ICP10ΔPK- but not HSV-2- or ICP10ΔRR-infected cultures (Fig. 10C), consistent with previous findings that c-Jun is subject to positive autoregulation (19, 59). P-Jun(Ser63) and P-Jun(Ser73) levels were similar for HSV-1, ICP6Δ, and hrR3 (Fig. 10D), suggesting that ICP6 is not involved in c-Jun activation.

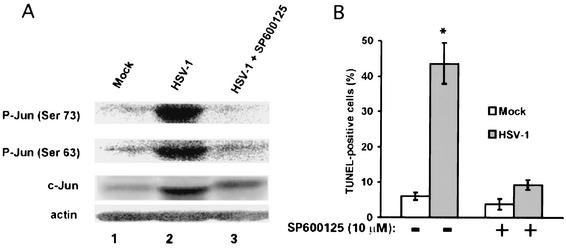

Activation of JNK/c-Jun pathway is required for HSV-1-induced apoptosis.

To determine the relationship between HSV-1-induced JNK activation and apoptosis, duplicates of hippocampal cultures were mock infected or infected with 10 PFU of HSV-1 per cell in the absence or presence of 10 μM SP600125, the JNK inhibitor (7, 36). They were examined for (i) c-Jun activation by immunoblotting with P-Jun(Ser63) and P-Jun(Ser73) antibodies and (ii) TUNEL reaction at 24 h postinfection The levels of P-Jun(Ser63) and P-Jun(Ser73) were significantly higher in HSV-1-infected (Fig. 11A, lane 2) than mock-infected (Fig. 11A, lane 1) cells. The levels of P-Jun in cells infected with HSV-1 in the presence of SP600125 (Fig. 11A, lane 3) were similar to those in mock-infected cells, supporting the conclusion that SP600125 is a JNK inhibitor.

FIG. 11.

HSV-1-mediated apoptosis depends on JNK/c-Jun activation. (A) Hippocampal cultures were mock infected (lane 1) or infected with 10 PFU of HSV-1 per cell in the absence (lane 2) or presence (lane 3) of 10 μM SP600125, the JNK inhibitor. Cell extracts obtained at 24 h postinfection were immunoblotted with antibodies specific for P-Jun(Ser73), followed by P-Jun(Ser63), c-Jun, and actin. (B) Duplicates of the cultures in A were assayed by TUNEL. The results of three independent experiments are expressed as mean TUNEL-positive cells ± standard error of the mean.

We conclude that JNK activation is required for HSV-1-induced apoptosis because the percentage of TUNEL-positive cells was significantly (P < 0.001 by analysis of variance) decreased in cultures infected with HSV-1 in the presence of SP600125 (7.3 ± 1.4% and 43.6 ± 5.8% for SP600125-treated and untreated cultures, respectively), while it was not altered in mock-infected cultures (3.8 ± 1.5% and 6 ± 1% for SP600125-treated and untreated cultures, respectively) (Fig. 11B).

DISCUSSION

Cell type-specific antiapoptotic activity has been attributed to various HSV-1 genes, most of which function by a still poorly understood mechanism (2, 15, 38, 47). However, to the extent of our knowledge, ICP10 PK is the first viral gene shown to inhibit apoptosis by activating the ERK survival pathway. The following comments seem pertinent with respect to these findings.

We used previously established conditions to examine the mechanism responsible for the ability of ICP10 PK to block apoptosis in central nervous system neurons and compare the results to those obtained for HSV-1. These included HSV-2 mutants deleted in the PK (ICP10ΔPK) or RR (ICP10ΔRR) domains of ICP10, transfection with expression vectors for ICP10 (pJW17) or its PK-negative mutant p139 (pJHL15) (3, 55, 66-68, 73-76), and primary hippocampal cultures that contained >88% postmitotic neurons, which have definite exons and dendrites, form synapses, are electrically active, and closely resemble neurons in vivo (5). Apoptosis was determined by TUNEL, morphological alterations, caspase activation, and poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase cleavage, a crucial factor in the cell's commitment to undergo apoptosis (48), with a good degree of correlation between the various assays. The specificity of the antibodies used in these studies was previously confirmed in our and other laboratories (3, 16, 55, 63, 66-68, 73-76). Normal rabbit serum was negative in all assays.

Apoptosis was seen in hippocampal and cortical neurons infected with HSV-1 or ICP10ΔPK but not with HSV-2, ICP10ΔRR, or HSV-2(R), supporting previous conclusions that ICP10 PK blocks apoptosis in hippocampal neurons (66, 67) and extending them to indicate that HSV-1 triggers apoptosis in these cells. Studies of ectopically delivered ICP10 PK indicated that its ability to block apoptosis is independent of other HSV-2 proteins, is kinase dependent, and overrides apoptosis triggered by HSV-1 or ICP10ΔPK. The percentage of apoptotic cells in HSV-2-infected cultures was significantly increased by transfection with the dominant negative Flag-c-Raf-1 mutant K375M, which inhibits c-Raf-1 kinase activity (18, 78), or by treatment with a pharmacologic inhibitor of c-Raf kinase, suggesting that Raf kinase is involved in antiapoptotic activity.

We conclude that ERK activation is causally related to Bag-1 induction and apoptosis inhibition because (i) ERK was activated and Bag-1 was induced by the antiapoptotic viruses HSV-2 and ICP10ΔRR but not the proapoptotic viruses ICP10ΔPK and HSV-1, (ii) ERK activation, Bag-1 induction, and ICP10 PK antiapoptotic activity were abrogated by the MEK-specific pharmacologic inhibitor U0126, and (iii) apoptosis induced by ICP10ΔPK or HSV-1 was blocked by ectopic delivery of ICP10 PK or Bag-1. Bcl-2, which cooperates with Bag-1 to interfere with the apoptotic cascade (39, 72, 79, 82), is also likely to contribute to the antiapoptotic activity of ICP10 PK. Indeed, Bcl-2 was stabilized in HSV-2- and ICP10ΔRR-infected cells, while its expression was decreased in cultures infected with HSV-1 or ICP10ΔPK as early as 0.5 h postinfection, and it was no longer detected at 24 h postinfection. This may reflect protein cleavage by caspases or other proteases (21, 33) or proteosome-dependent degradation and may be due to activation of the proapoptotic JNK/c-Jun pathway (91). We favor the interpretation that in HSV-2- and ICP10ΔRR-infected cells, Bcl-2 is stabilized by interacting with Bag-1 (79). However, the contribution of other factors, such as c-Raf-1-mediated phosphorylation (9, 21, 83), cannot be excluded.

Significantly, protection by transfection with pJW17 (ICP10) or pJG4-5m (Bag-1) was approximately two- to threefold higher than the percentage of transfected cells, suggesting that neurons rescued from apoptosis by ICP10 PK or Bag-1 produce trophic factors and/or form synapses that stimulate the survival and adaptive responses of surrounding neurons. Such a bystander effect is consistent with previous reports that (i) hippocampal neurons secrete and respond to nerve growth factor (5, 13), (ii) ICP10 PK protects hippocampal neurons from apoptosis caused by nerve growth factor withdrawal (67), and (iii) the levels of apoptosis induced by the dominant negative c-Raf-1 mutant K375M were higher than predicted by the transfection efficiency, presumably reflecting previously documented findings that apoptotic neurons release glutamate, which in turn triggers apoptosis in surrounding neurons (44, 62, 65). Ongoing studies are designed to test the validity of these interpretations and further define the role of Raf kinase in apoptosis inhibition, with emphasis on the contribution of neuronal cell receptors and survival pathways in uninfected neurons.

Also under investigation is the antiapoptotic activity of ICP10 PK in stably transfected neural cell lines similar to our previously established nonneuronal lines (73, 76). However, neural cell lines do not reflect the properties of neurons in vivo (5) and provide potentially misleading information, as suggested by recent findings that Bcl-2 overexpression is neuroprotective in such lines but not in primary cultures of postmitotic neurons (14, 46). This underscores the significance of the finding that ICP10 PK blocks apoptosis in postmitotic neurons and its promise as a therapeutic agent for neurological disorders with an apoptotic component (42).

The ERK pathway imparts survival by transcription-dependent and/or -independent mechanisms (11, 87, 92). We reason that ICP10 PK functions primarily by a transcription-dependent mechanism, because it activates MEK/ERK, which are required for Bag-1 induction and are probably also responsible for increased CREB activation in HSV-2-infected cultures. Presumably, the low levels of phosphorylated CREB in mock-infected cultures reflect CREB activation by the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt pathway, which is required for basal maintenance of hippocampal neurons (49, 66) and is associated with neuronal cell survival (24). Indeed, CREB plays a key role in neurotrophin-dependent survival, including Bcl-2 transcriptional activation (10, 49, 71), and it is activated by both the ERK and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt pathways (89). Because CREB has antiapoptotic activity even when it is not phosphorylated, presumably by competing with c-Jun for alkaline phosphatase-1 binding sites on target genes (25, 56), its apparent cleavage in ICP10ΔPK-infected cultures is likely to contribute to apoptosis induction. However, the exact role played by CREB in apoptosis inhibition and its relationship to Bag-1, if any, are still unclear.

Previous studies of nonneuronal cells showed that HSV-1 activates JNK/c-Jun and that this is required for virus replication (57, 90, 91). We found that HSV-1 also activates JNK in hippocampal neurons, beginning at 0.5 h postinfection. However, this is unrelated to virus replication, since JNK was activated equally well by ICP10ΔPK, which does not replicate in these cells (66). JNK activation by HSV-1 and ICP10ΔPK (but not HSV-2 or ICP10ΔRR) was accompanied by c-Jun phosphorylation at Ser63 and Ser73, conditions that increase its ability to activate the transcription of target genes, including c-Jun itself (6, 59). We conclude that activation of the JNK/c-Jun pathway is involved in HSV-1 (and ICP10ΔPK)-induced apoptosis, because both Jun phosphorylation and TUNEL were inhibited with the JNK-specific inhibitor SP600125.

The transcription factor ATF-2, which dimerizes and cooperates with c-Jun to induce neuronal cell apoptosis (19, 34, 35, 56, 60, 81), and the antiapoptotic protein BAD also seem to be targets of the JNK/c-Jun pathway activated by HSV-1 and ICP10ΔPK. The role of ATF-2 in HSV-1 (and ICP10ΔPK)-induced apoptosis is still unclear, but our findings for BAD are consistent with a previous report that it is phosphorylated by the HSV-1 US3 protein kinase and is involved in HSV-1-induced apoptosis of nonneuronal cells (61). In hippocampal neurons, BAD expression was induced by HSV-1 or ICP10ΔPK (but not HSV-2 or ICP10ΔRR), suggesting that US3 does not have antiapoptotic activity in these cells. It remains to be shown that BAD expression is also induced by a JNK/c-Jun-dependent mechanism (11, 12, 49) in our system. Notwithstanding, the absence of Bag-1 and the inhibition/degradation of Bcl-2 in HSV-1- and ICP10ΔPK-infected cultures shifts the balance between the anti- and proapoptotic functions in favor of apoptosis.

The finding that only 40 to 60% of the cells in the HSV-1- or ICP10ΔPK-infected cultures undergo apoptosis is difficult to reconcile with the high multiplicity of infection used in these experiments, which ensures that all cells are infected. It may reflect the contribution of cellular proteins that differ in their function as JNK/c-Jun targets, such as the Fas ligand (60), death cytokine tumor necrosis factor alpha (41, 45), and transcription factors p53 and c-Myc, the phosphorylation of which (by JNK) induces their proapoptotic function (26, 58, 64). Notwithstanding, the data indicate that ICP10 PK activates the ERK survival pathway, which overrides the apoptotic JNK/c-Jun signal (53, 80), apparently triggered by proteins shared by the two HSV serotypes.

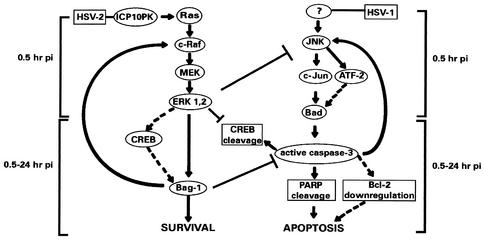

Collectively, the data are consistent with the model schematically represented in Fig. 12. It posits rapid activation of the apoptotic JNK/c-Jun pathway in central nervous system neurons infected in the absence of ICP10 PK (e.g., by HSV-1). Activation is likely mediated by a virion protein(s) (is independent of virus replication), and it sets in motion an apoptotic cascade that includes induction of the proapoptotic protein BAD, activation of caspase 3, cleavage of its substrate poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase, and destabilization of the antiapoptotic protein Bcl-2, culminating in apoptosis at 24 h postinfection. Activated caspase 3 increases JNK activation in a positive feedback loop, thereby enhancing apoptosis. Rapid activation of the ERK pathway by ICP10 PK within HSV-2 virions (74) overrides these effects. Upregulation of the antiapoptotic protein Bag-1 by the activated ERK survival pathway is a crucial element in apoptosis inhibition. Antiapoptotic activity is also likely to include a positive feedback loop that involves c-Raf-1 activation. However, our studies do not establish the role of HSV-2 (ICP10 PK) in Raf kinase activation or exclude the contribution of other, transcription-independent neuroprotective activities.

FIG. 12.

Schematic representation of apoptosis modulation in central nervous system neurons infected with HSV-2 or HSV-1. Dotted lines represent potentially involved factors. pi, postinfection.

What is the biological and clinical relevance of these findings? Previous studies have shown that (i) expression of ICP10 PK is required for stress-induced HSV-2 reactivation from ganglionic latency (3) and (ii) ICP10 PK is homologous to a newly identified heat shock protein (4, 77). Together with these findings and recent conclusions that the heat shock protein gene family is a distinct class of apoptosis regulatory proteins (28), our data indicate that expression of heat shock protein homologues is a novel mechanism for virus-induced antiapoptotic activity. The N-terminal domain of ICP6, the HSV-1 homologue of ICP10 PK, did not affect HSV-1-induced apoptosis, consistent with its lack of PK activity (16). While the evolutionary processes responsible for this functional divergence remain speculative, we have recently shown that HSV-1-induced encephalitis in humans has an apoptotic component that involves hippocampal neurons (68), suggesting that the antiapoptotic activity of ICP10 PK contributes to the relative paucity of adult HSV-2 encephalitis (8).

ICP10 PK is a particularly promising gene therapy candidate for neurodegenerative diseases, because activation of the ERK pathway was implicated in long-term potentiation (the cellular substrate of memory), which determines cognitive functions (20). Furthermore, our findings have significant implications for the use of HSV-1 as a vector for gene delivery to the brain (28), since the apoptotic JNK/c-Jun pathway (35, 60) and its target BAD (11, 12) are upregulated in HSV-1-infected central nervous system neurons. However, caution should be taken when extrapolating our findings to apoptotic cell death in HSV-1- or HSV-2-infected neurons of the peripheral nervous system.

Acknowledgments

We thank Cynthia Smith for helpful discussions and critical review of the manuscript and Paul H. Lackey for graphics assistance.

These studies were supported by Public Health Service grants AR42647 to L. Aurelian and NS25296 to E. F. R. Pereira.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alkondon, M., and E. X. Albuquerque. 1993. Diversity of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in rat hippocampal neurons. I. Pharmacological and functional evidence for distinct structural subtypes. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 265:1455-1473. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aubert, M., and J. A. Blaho. 1999. The herpes simplex virus type 1 regulatory protein IC27 is required for the prevention of apoptosis in infected human cells. J. Virol. 73:2803-2813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aurelian, L., and C. C. Smith. 2000. Herpes simplex type 2 growth and latency reactivation by cocultivation are inhibited with antisense oligonucleotides complementary to the translation initiation site of the large subunit of ribonucleotide reductase (RR1). Antisense Nucleic Acid Drug Dev. 10:77-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aurelian, L., C. C. Smith, R. Winchurch, M. Kulka, L. Zaccaro, T. Gyotoku, F. J. Chrest, and J. W. Burnett. 2001. A novel gene expressed in human keratinocytes with long term growth potential is required for cell growth. J. Investig. Dermatol. 116:286-295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Banker, G., and K. Goslin. 1998. Types of nerve cell cultures, their advantages and limitations, p. 11-39. In G. Banker and K. Goslin (ed.), Culturing nerve cells, 2nd ed. MIT Press, Cambridge, Mass.

- 6.Behrens, A., M. Sibilis, and E. F. Wagner. 1999. Amino-terminal phosphorylation of c-Jun regulates stress-induced apoptosis and cellular proliferation. Nat. Genet. 21:326-329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bennett, B. L., D. T. Sasaki, B. W. Murray, E. C. O'Leary, S. T. Sakata, W. Xu, J. C. Leistein, A. Motiwala, S. Pierce, Y. Satoh, S. S. Bhagwat, A. M. Manning, and D. W. Anderson. 2001. SP600125, an anthrapyrazolone inhibitor of Jun N-terminal kinase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:13681-13686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bergstrom, T., B. Svennerholm, N. Conradi, P. Horal, and A. Vahlne. 1991. Discrimination of herpes simplex types 1 and 2 cerebral infections in a rat model. Acta Neuropathol. 82:395-401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Birge, R. B., E. Fajardo, and Hempstead, B. L. 1998. Signal transduction and neuronal cell death during development and disease, p. 347-383. In R. A. Lockshin, Z. Zakeri, and J. L. Tilly (ed.), When cells die. Wiley Liss, New York, N.Y.

- 10.Bonni, A., A. Brunet, A. E. West, S. R. Datta, M. A. Takasu, and M. E. Greenberg. 1999. Cell survival promoted by the Ras-mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathway by transcription-dependent and independent mechanisms. Science 286:1358-1362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bossy-Wetzel, E., L. Bakiri, and M. Yaniv. 1997. Induction of apoptosis by the transcription factor c-Jun. EMBO J. 16:1695-1709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bossy-Wetzel, E., D. D. Newmeyer, and D. R. Green. 1998. Mitochondrial cytochrome c release in apoptosis occurs upstream of DEVD-specific caspase activation and independent of mitochondrial transmembrane depolarization. EMBO J. 17:37-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bothwell, M. 1991. Keeping track of neurotrophin receptors. Cell 65:915-918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cheung, N. S., P. M. Beart, C. J. Pascoe, C. A. John, and O. Bernard. 2000. Human Bcl-2 protects against AMPA receptor-mediated apoptosis. J. Neurochem. 74:1613-1620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chou, J., and B. Roizman. 1992. The γ134.5 gene of herpes simplex virus type 1 precludes neuroblastoma cells from triggering total shut off of protein synthesis characteristic of programmed cell death in neuronal cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89:3266-3270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chung, T. D., J. P. Wymer, C. C. Smith, M. Kulka, and L. Aurelian. 1989. Protein kinase activity associated with the large subunit of herpes simplex virus type 2 ribonucleotide reductase (ICP10). J. Virol. 63:3389-3398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cookson, M. R., P. G. Ince, P. A. Usher, and P. J. Shaw. 1999. Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase is found in both the nucleus and cytoplasm of human central nervous system neurons. Brain Res. 834:182-185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dent, P., D. B. Reardon, D. K. Morrison, and T. W. Sturgill. 1995. Regulation of Raf-1 and Raf-1 mutants by Ras-dependent and Ras-independent mechanisms in vitro. Mol. Cell. Biol. 15:4125-4135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eilers, A., J. Whitfield, B. Shah, C. Spadoni, H. Desmond, and J. Ham. 2001. Direct inhibition of c-Jun N-terminal kinase in sympathetic neurons prevents c-jun promoter activation and nerve growth factor withdrawal-induced death. J. Neurochem. 76:1439-1454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.English. J. D., and J. D. Sweatt. 1996. Activation of p42 mitogen-activated protein kinase in hippocampal long-term potentiation. J. Biol. Chem. 271:24329-24332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fadeel, B., B. Zhivotovsky, and S. Orrenius. 1999. All along the watchtower: on the regulation of apoptosis regulators. FASEB J. 13:1647-1657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Favata, M. F., K. Y. Horiuchi, E. J. Manos, A. J. Dauleri, D. A. Stradley, W. S. Feeser, D. E. Van Dyk, W. J. Pitts, R. A. Earl, F. Hobbs, R. A. Copeland, R. L. Magolda, P. A. Scherle, and J. M. Trzaskos. 1998. Identification of a novel inhibitor of mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 273:18623-18632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ferreira, A., and A. Caceres. 1992. Expression of the class III beta-tubulin isotype in developing neurons in culture. J. Neurosci. Res. 32:516-529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Finkbeiner, S., S. F. Tavazoie, A. Maloratsky, K. M. Jacobs, K. M. Harris, and M. E. Greenberg. 1997. CREB: a major mediator of neuronal neurotrophin responses. Neuron 19:1031-1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Francois, F., M. J. Godinho, and M. L. Grimes. 2000. CREB is cleaved by caspases during neural cell apoptosis. FEBS Lett. 486:281-284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fuchs, S. Y., V. Adler, M. R. Pincus, and Z. Ronai. 1998. MEKK1/JNK signaling stabilizes and activates p53. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:10541-10546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Garrido, C., S. Gurbuxani, L. Ravagnan, and G. Kroemer. 2001. Heat shock proteins: endogenous modulators of apoptotic cell death. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 286:433-442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gavrieli, Y., Y. Sherman, and S. A. Ben-Sasson. 1992. Identification of programmed cell death via specific labeling of nuclear DNA fragmentation. J. Cell Biol. 119:493-501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Glorioso, J. C., and D. J. Fink. 2002. Use of HSV vectors to modify the nervous system. Curr. Opin. Drug Discov. Dev. 5:289-295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gold, R., M. Schmied, G. Giegerich, H. Beitschopf, H. P. Hartung, K. V. Toyka, and H. Lassman. 1994. Differentiation between cellular apoptosis and necrosis by the combined use of in situ tailing and nick translation techniques. Lab. Investig. 71:219-225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Goldstein, D. J., and S. K. Weller. 1987. Herpes simplex virus type 1-induced ribonucleotide reductase activity is dispensable for virus growth and DNA synthesis: isolation and characterization of an ICP6 lacZ insertion mutant. J. Virol. 62:196-205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Goldstein, D. J., and S. K. Weller. 1988. Factor(s) present in herpes simplex virus type 1-infected cells can compensate for the loss of the large subunit of the viral ribonucleotide reductase: characterization of an ICP6 deletion mutant. Virology 166:41-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Grandgirard, D., E. Studer, L. Monney, T. Belser, I. Fellay, C. Borner, and M. R. Michel. 1998. Alphaviruses induce apoptosis in Bcl-2-overexpressing cells: evidence for a caspase-mediated, proteolytic inactivation of Bcl-2. EMBO J. 17:1268-1278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gupta, S., T. Barrett, A. J. Whitmarsh, J. Cavanagh, H. K. Sluss, B. Derijard, and R. Davis. 1996. Selective interaction of JNK protein kinase isoforms with transcription factors. EMBO J. 15:2760-2770. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ham, J., C. Babij, J. Whitfield, C. M. Pfarr, D. Lallemand, M. Yaniv, and L. L. Rubin. 1995. A c-Jun dominant negative mutant protects sympathetic neurons against programmed cell death. Neuron 14:927-939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Han, Z., D. L. Boyle, L. Chang, B. Bennett, M. Karin, L. Yang, A. M. Manning, and G. S. Firestein. 2001. c-Jun N-terminal kinase is required for metalloproteinase expression and joint destruction in inflammatory arthritis. J. Clin. Investig. 108:73-81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hardwick, J. M., G. Ketner, and R. J. Clem. 1998. Viral genes that modulate apoptosis, p. 243-279. In J. W. Wilson, C. Booth, and C. S. Potten (ed.), Apoptosis genes. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, The Netherlands.

- 38.Hata, S., A. H. Koyama, H. Shiota, A. Adachi, F. Goshima, and Y. Nishiyama. 1999. Anti-apoptotic activity of herpes simplex virus type 2: the role of US3 protein kinase gene. Microbes Infect. 1:601-607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hayashi, T., K. Sakai, C. Sasaki, Y. Itoyama, and K. Abe. 2000. Loss of bag-1 immunoreactivity in rat brain after transient middle cerebral artery occlusion. Brain Res. 852:496-500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Herdegen, T., A. Blume, T. Buschmann, E. Georgakopoulos, C. Winter, W. Schmid, T. F. Hsieh, M. Zimmermann, and P. Gass. 1997. Expression of activating transcription factor-2, serum response factor and cAMP/Ca response element binding protein in the adult rat brain following generalized seizures, nerve fibre lesion and ultraviolet irradiation. Neuroscience 81:199-212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hoffmeyer, A., A. Grosse-Wilde, E. Flory, B. Neufeld, M. Kunz, U. R. Rapp, and S. Ludwig. 1999. Different mitogen-activating protein kinase signaling pathways cooperate to regulate tumor necrosis factor gene expression in T lymphocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 274:4319-4327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Honig, L. S., and R. N. Rosenberg. 2000. Apoptosis and neurologic disease. Am. J. Med. 108:317-330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Horie, M., Y. Mitsumoto, H. Kyushiki, N. Kanemoto, A. Watanabe, Y. Taniguchi, N. Nishino, T. Okamoto, M. Kondo, T. Mori, K. Noguchi, Y. Nakamura, E. Takahashi, and A. Tanigami. 2000. Identification and characterization of TMEFF2, a novel survival factor for hippocampal and mesencephalic neurons. Genomics 67:146-152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hyman, B. T., G. W. Van Hoesen, and A. R. Damasio. 1990. Memory-related neural systems in Alzheimer's disease: an anatomic study. Neurology 40:1721-1730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ishizuka, T., N. Terada, P. Gerwins, E. Hamelmann, A. Oshiba, G. R. Fanger, G. L. Johnson, and E. W. Gelfand. 1997. Mast cell tumor necrosis factor is regulated by MEK kinases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:6358-6363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ivins, K. J., J. K. Ivins, J. P. Sharp, and C. W. Cotman. 1999. Multiple pathways of apoptosis in PC12 cells. CrmA inhibits apoptosis induced by β-amyloid. J. Biol. Chem. 274:2107-2112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jerome, K. R., R. Fox, Z. Chen, A. E. Sears, H.-Y. Lee, and L. Corey. 1999. Herpes simplex virus inhibits apoptosis through the action of two genes, US5 and US3. J. Virol. 73:8950-8957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Johnson Webb, S., D. J. Harrison, and A. H. Wyllie. 1997. Apoptosis: an overview of the process and its relevance in disease. Adv. Pharmacol. 41:1-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kaplan, D. R., and F. D. Miller. 2000. Neurotrophin signal transduction in the nervous system. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 10:381-391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kitamura, Y., S. Shimohama, W. Kamoshima, T. Ota, Y. Matsuoka, Y. Nomura, M. A. Smith, G. Perry, P. J. Whitehouse, and T. Taniguchi. 1998. Alteration of proteins regulating apoptosis, Bcl-2, Bcl-x, Bax, Bak, Bad, ICH-1 and CPP32, in Alzheimer's disease. Brain Res. 780:260-269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kyriakis, J. M., and J. Avruch. 1996. Sounding the alarm: protein kinase cascades activated by stress and inflammation. J. Biol. Chem. 271:24313-24316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lackey, K., M. Cory, R. Davis, S. V. Frye, P. A. Harris, R. N. Hunter, D. K. Jung, O. B. McDonald, R. W. McNutt, M. R. Peel, R. D. Rutkowske, J. M. Veal, and E. R. Wood. 2000. The discovery of potent cRaf1 kinase inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 10:223-226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Levresse, V., L. Butterfield, E. Zentrich, and L. E. Heasley. 2000. Akt negatively regulates c-Jun N-terminal kinase pathway in PC12 cells. J. Neurosci. Res. 62:799-808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lewis, T. S., P. S. Shapiro, and N. G. Ahn. 1998. Signal transduction through mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade. Adv. Cancer. Res. 74:49-139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Luo, J., and L. Aurelian. 1992. The transmembrane helical segment but not the invariant lysine is required for the kinase activity of the large subunit of herpes simplex virus type 2 ribonucleotide reductase (ICP10). J. Biol. Chem. 267:9645-9653. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Masquilier, D., and P. Sassone-Corsi. 1992. Transcriptional cross-talk: nuclear factors CREM and CREB bind to alkaline phosphatase-1 sites and inhibit activation by Jun. J. Biol. Chem. 267:22460-22466. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.McLean, T. I., and S. L. Bachenheimer. 1999. Activation of c-Jun terminal kinase by herpes simplex virus type 1 enhances viral replication. J. Virol. 73:8415-8426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Milne, D. M., L. E. Campbell, D. G. Campbell, and D. W. Meek. 1995. p53 is phosphorylated in vitro and in vivo by an ultraviolet radiation-induced protein kinase characteristic of the c-Jun kinase JNK1. J. Biol. Chem. 270:5511-5518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Minden, A., and M. Karin. 1997. Regulation and function of the JNK subgroup of mitogen-activated protein kinases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1333:F85-F104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Morishima, Y., Y. Gotoh, J. Zieg, T. Barrett, H. Takano, R. Flavell, R. J. Davis, Y. Shirasaki, and M. E. Greenberg. 2001. Beta-amyloid induces neuronal apoptosis via a mechanism that involves the c-jun N-terminal kinase pathway and the induction of Fas ligand. J. Neurosci. 21:7551-7560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Munger, J., and B. Roizman. 2001. The US3 protein kinase of herpes simplex virus 1 mediates the posttranslational modification of BAD and prevents BAD-induced programmed cell death in the absence of other viral proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci USA 98:10410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Newcomb, R., X. Sun, I. Taylor, N. Curthoys, and R. G. Fiffard. 1997. Increased production of extracellular glutamate by the mitochondrial glutaminase following neuronal death. J. Biol. Chem. 272:11276-11282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nicholson, D. W., A. Ali, N. A. Thornberry, J. P. Vaillancourt, C. K. Ding, M. Gallant, Y. Gareau, P. R. Griffin, M. Labelle, Y. A. Lazebnik, N. A. Munday, S. M. Raju, M. E. Smulson, T.-T. Yamin, V. L. Yu, and D. K. Miller. 1995. Identification and inhibition of the ICE/CED-3 protease necessary for mammalian apoptosis. Nature 376:37-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Noguchi, K., C. Kitanaka, H. Yamana, A. Kokubu, T. Mochizuki, and Y. Kuchino. 1999. Regulation of c-Myc trough phosphorylation at Ser-62 and Ser-71 by c-Jun N-terminal kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 274:32580-32587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Otterson, O. P. 1991. Excitatory amino acid neurotransmitters: anatomical systems, p. 14-38. In B. S. Meldrum (ed.), Excitatory amino acid antagonists. Blackwell Scientific, Oxford, UK.

- 66.Perkins, D., E. F. R. Pereira, M. Gober, P. J. Yarowsky, and L. Aurelian. 2002. The herpes simplex virus type 2 R1 protein kinase (ICP10 PK) blocks apoptosis in hippocampal neurons involving activation of the MEK/mitogen-activated protein kinase survival pathway. J. Virol. 76:1435-1449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 67.Perkins, D., Y. X. Yu, L. L. Bambrick, P. J. Yarwosky, and L. Aurelian. 2002. Expression of herpes simplex virus type 2 protein ICP10 PK rescues neurons from apoptosis due to serum deprivation or genetic defects. Exp. Neurol. 174:118-122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Perkins, D., K. A. Gyure, E. F. R. Pereira, and L. Aurelian. Herpes simplex virus type 1 induced encephalitis has an apoptotic component associated with activation of c-Jun N-terminal kinase. J. Neurovirol., in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 69.Perng, G.-C., C. Jones, J. Ciacci-Zanella, M. Stone, G. Henderson, A. Yukht, S. M. Slanina, F. M. Hofman, H. Ghiasi, A. B. Nesburn, and S. L. Wechsler. 2000. Virus-induced neuronal apoptosis blocked by the herpes simplex virus latency-associated transcript. Science 287:1500-1503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Reed, J. C. 1994. Bcl-2 and the regulation of programmed cell death. J. Cell Biol. 124:1-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Riccio, A., S. Ahn, C. M. Davenport, J. A. Blendy, and D. D. Ginty. 1999. Mediation by a CREB family transcription factor of nerve growth factor-dependent survival of sympathetic neurons. Science 286:2358-2361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Schulz, J. B., D. Bremen, J. C. Reed, J. Lommatzsch, S. Takayama, U. Wullner, P.-A. Loschmann, T. Klockgether, and M. Weller. 1997. Cooperative interception of neuronal apoptosis by Bcl-2 and Bag-1 expression: prevention of caspase activation and reuced production of reactive oxygen species. J. Neurochem. 69:2075-2086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Smith, C. C., J. H. Luo, J. C. R. Hunter, J. V. Ordonez, and L. Aurelian. 1994. The transmembrane domain of the large subunit of HSV-2 ribonucleotide reductase (ICP10) is required for protein kinase activity and transformation-related signaling pathways that result in ras activation. Virology 200:598-612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Smith, C. C., and L. Aurelian. 1997. The large subunit of herpes simplex virus type 2 ribonucleotide reductase (ICP10) is associated with the virion tegument and has PK activity. Virology 234:235-242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Smith, C. C., T. Peng, M. Kulka, and L. Aurelian. 1998. The protein kinase domain of the large subunit of herpes simplex virus type 2 ribonucleotide reductase (ICP10) is required for immediate-early gene expression and virus growth. J. Virol. 72:9131-9141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Smith, C. C., J. Nelson, L. Aurelian, M. Gober, and B. B. Goswami. 2000. Ras-GAP binding/phosphorylation by herpes simplex virus type 2 RR1 protein kinase (ICP10) and activation of the Ras/MEK/mitogen-activated protein kinase mitogenic pathway are required for timely onset of virus growth. J. Virol. 74:10417-10429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Smith, C. C., Y. X. Yu, M. Kulka, and L. Aurelian. 2000. A novel human gene similar to the PK coding domain of the large subunit of herpes simplex virus type 2 ribonucleotide reductase (ICP10) codes for a serine-threonine PK and is expressed in melanoma cells. J. Biol. Chem. 275:25690-25699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Soh, J.-W., E. H. Lee, R. Prywes, and B. Weinstein. 1999. Novel roles of specific isoforms of protein kinase C in activation of the c-fos serum response element. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19:1313-1324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Takayama, S., T. Sato, S. Krajewski, K. Kochel, S. Irie, J. A. Millan, and J. C. Reed. 1995. Cloning and functional analysis of BAG-1: a novel Bcl-2 binding protein with anti-cell death activity. Cell 80:279-284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Tran, S. E. F., T. H. Holmstrom, M. Ahonen, V-M, Kahari, and J. E. Eriksson. 2001. mitogen-activated protein kinase/ERK overrides the apoptotic signaling from Fas, tumor necrosis factor alpha, and TRAIL receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 276:16484-16490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Van Dam, H., D. Wilhelm, I. Herr, A. Steffen, P. Herlich, and P. Angel. 1995. ATF-2 is preferentially activated by stress-activated protein kinases to mediate c-jun induction in response to genotoxic stress. EMBO J. 14:1798-1811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]