Abstract

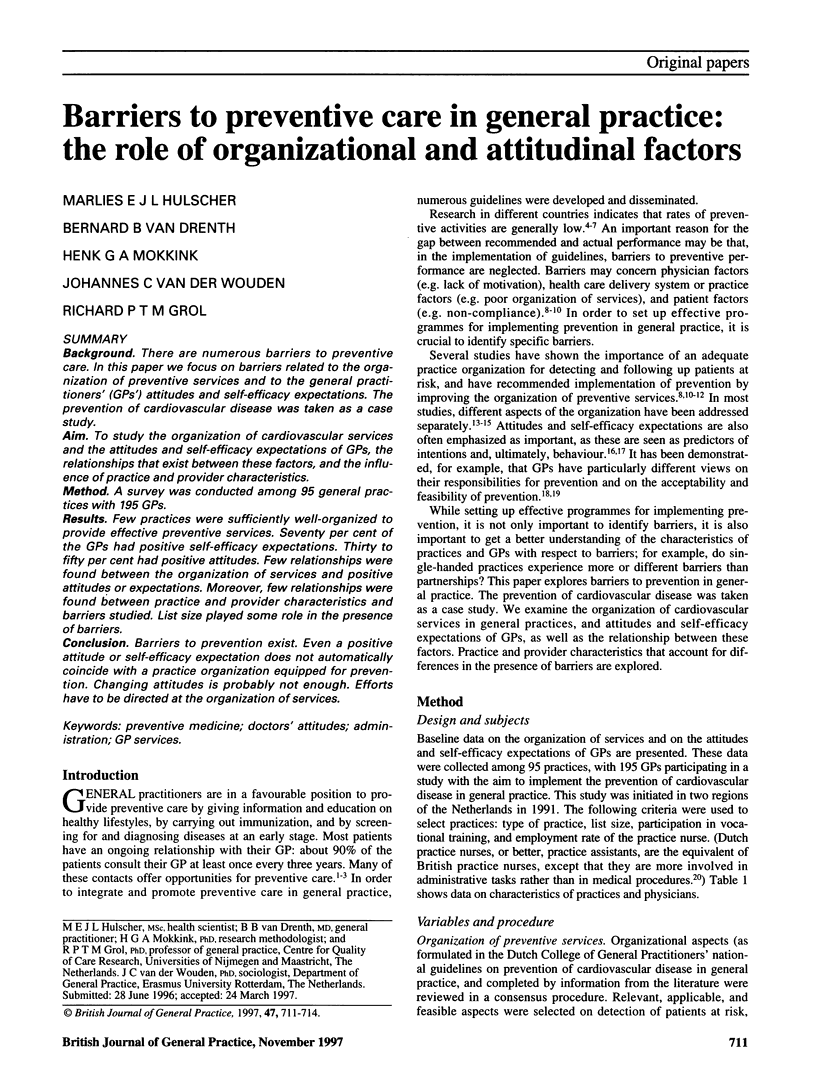

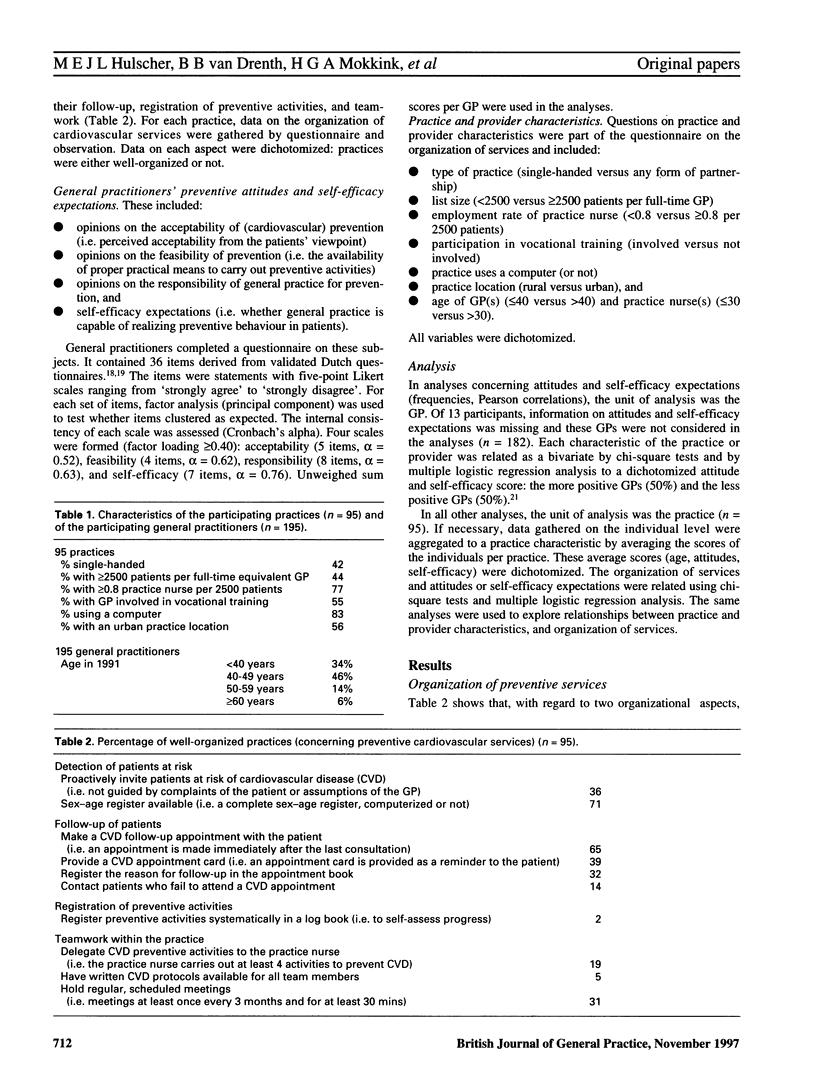

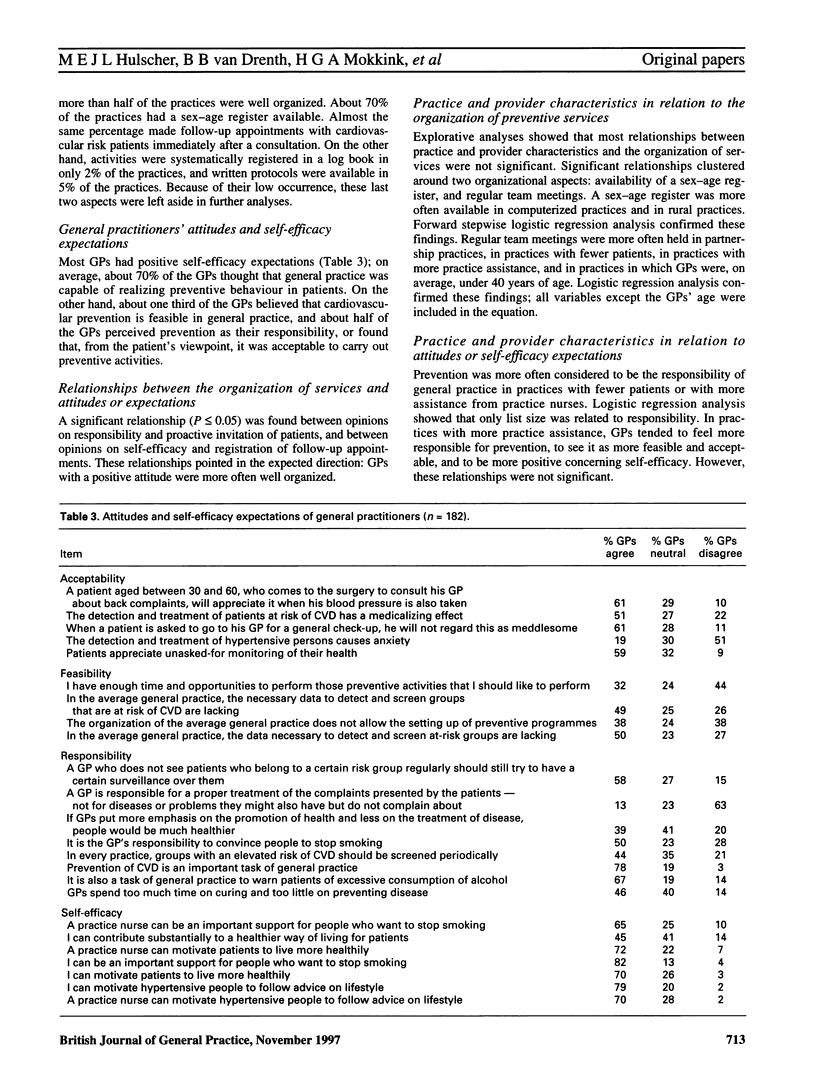

BACKGROUND: There are numerous barriers to preventive care. In this paper we focus on barriers related to the organization of preventive services and to the general practitioners' (GPs') attitudes and self-efficacy expectations. The prevention of cardiovascular disease was taken as a case study. AIM: To study the organization of cardiovascular services and the attitudes and self-efficacy expectations of GPs, the relationships that exist between these factors, and the influence of practice and provider characteristics. METHOD: A survey was conducted among 95 general practices with 195 GPs. RESULTS: Few practices were sufficiently well-organized to provide effective preventive services. Seventy per cent of the GPs had positive self-efficacy expectations. Thirty to fifty per cent had positive attitudes. Few relationships were found between the organization of services and positive attitudes or expectations. Moreover, few relationships were found between practice and provider characteristics and barriers studied. List size played some role in the presence of barriers. CONCLUSION: Barriers to prevention exist. Even a positive attitude or self-efficacy expectation does not automatically coincide with a practice organization equipped for prevention. Changing attitudes is probably not enough. Efforts have to be directed at the organization of services.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Battista R. N., Williams J. I., Boucher J., Rosenberg E., Stachenko S. J., Adam J., Levinton C., Suissa S. Testing various methods of introducing health charts into medical records in family medicine units. CMAJ. 1991 Jun 1;144(11):1469–1474. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carney P. A., Dietrich A. J., Keller A., Landgraf J., O'Connor G. T. Tools, teamwork, and tenacity: an office system for cancer prevention. J Fam Pract. 1992 Oct;35(4):388–394. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cecchini S., Grazzini G., Bartoli D., Falvo I., Ciatto S. An attempt to increase compliance to cervical cancer screening through general practitioners. Tumori. 1989 Dec 31;75(6):615–618. doi: 10.1177/030089168907500621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elford R. W., Jennett P., Bell N., Szafran O., Meadows L. Putting prevention into practice. Health Rep. 1994;6(1):142–153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler G. The challenge of prevention. Practitioner. 1984 Dec;228(1398):1143–1147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frame P. S. Health maintenance in clinical practice: strategies and barriers. Am Fam Physician. 1992 Mar;45(3):1192–1200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frame P. S., Kowulich B. A., Llewellyn A. M. Improving physician compliance with a health maintenance protocol. J Fam Pract. 1984 Sep;19(3):341–344. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gann P., Melville S. K., Luckmann R. Characteristics of primary care office systems as predictors of mammography utilization. Ann Intern Med. 1993 Jun 1;118(11):893–898. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-118-11-199306010-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart J. T. James Mackenzie lecture 1989. Reactive and proactive care: a crisis. Br J Gen Pract. 1990 Jan;40(330):4–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heywood A., Sanson-Fisher R., Ring I., Mudge P. Risk prevalence and screening for cancer by general practitioners. Prev Med. 1994 Mar;23(2):152–159. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1994.1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis C. E. Disease prevention and health promotion practices of primary care physicians in the United States. Am J Prev Med. 1988;4(4 Suppl):9–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Love R. R. Changing the health promotion behaviors of primary care physicians: lessons from two projects. Jt Comm J Qual Improv. 1995 Jul;21(7):339–343. doi: 10.1016/s1070-3241(16)30159-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pommerenke F. A., Dietrich A. Improving and maintaining preventive services. Part 1: Applying the patient path model. J Fam Pract. 1992 Jan;34(1):86–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stott N. C., Davis R. H. The exceptional potential in each primary care consultation. J R Coll Gen Pract. 1979 Apr;29(201):201–205. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weingarten M. A., Bazel D., Shannon H. S. Computerized protocol for preventive medicine: a controlled self-audit in family practice. Fam Pract. 1989 Jun;6(2):120–124. doi: 10.1093/fampra/6.2.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wender R. C. Cancer screening and prevention in primary care. Obstacles for physicians. Cancer. 1993 Aug 1;72(3 Suppl):1093–1099. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19930801)72:3+<1093::aid-cncr2820721326>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Weel C. Teamwork. Lancet. 1994 Nov 5;344(8932):1276–1279. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)90756-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]