Abstract

We analyzed the breadth of the unfolded protein response (UPR) in Arabidopsis using gene expression analysis with Affymetrix GeneChips. With tunicamycin and DTT as endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress–inducing agents, we identified sets of UPR genes that were induced or repressed by both stresses. The proteins encoded by most of the upregulated genes function as part of the secretory system and comprise chaperones, vesicle transport proteins, and ER-associated degradation proteins. Most of the downregulated genes encode extracellular proteins. Therefore, the UPR may constitute a triple effort by the cell: to improve protein folding and transport, to degrade unwanted proteins, and to allow fewer secretory proteins to enter the ER. No single consensus response element was found in the promoters of the 53 UPR upregulated genes, but half of the genes contained response elements also found in mammalian UPR regulated genes. These elements are enriched from 4.5- to 15-fold in this upregulated gene set.

INTRODUCTION

When stress causes protein folding in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) to be slowed, the temporary presence of an abundance of unfolded proteins in the ER triggers the unfolded protein response (UPR). The UPR results in the first instance in the enhanced expression of those genes known to encode proteins that create the optimal polypeptide-folding environment, such as protein disulfide isomerase (PDI), calreticulin, calnexin, and binding protein (BiP). Early studies showed that some of these genes are induced by tunicamycin, an inhibitor of Asn-linked glycosylation, or by DTT, which prevents disulfide bond formation (Denecke et al., 1991; Fontes et al., 1991; D'Amico et al., 1992; Shorrosh and Dixon, 1992; Oliver et al., 1995; Koizumi et al., 2001). In the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, the UPR affects not only ER chaperone genes but also numerous genes of the secretory pathway and of the ER-associated protein degradation (ERAD) system. The UPR upregulated gene set accounts for 6% of the yeast genome (Travers et al., 2000).

The unfolded protein signal is transmitted from the ER to the nucleus by a transmembrane protein kinase (Ire1) that has a unique kinase/ribonuclease domain in the nucleoplasm. Arabidopsis has two genes that are homologs of Ire1 (AtIre1-1 and AtIre1-2), and rice has one (OsIre1). These Ire1 homolog proteins have the four characteristic domains found in yeast and mammalian Ire proteins: a lumenal sensing domain, a transmembrane domain, a protein kinase domain, and a ribonuclease domain (Koizumi et al., 2001; Okushima et al., 2002). A third AtIre1-like gene has been found in the Arabidopsis database (At3g11870, F26K24.16), but the derived amino acid sequence contains only the kinase and ribonuclease domains.

Analysis of the promoter regions of UPR target genes has revealed three different ER stress–response elements: a UPR element (UPRE), ER stress–response element I (ERSE-I), and ERSE-II. The UPREs correspond to TGACGTGG/A in mammals (Okada et al., 2002) and to CAGCGTG in yeast (Mori et al., 1996); ERSE-I corresponds to CCAAT-N9-CCA-CG (Roy and Lee, 1999), and ERSE-II corresponds to ATT-GG-N-CCACG (Kokame et al., 2001), both of them in mammals. In yeast, the basic domain/Leu zipper (bZIP) trans-acting factor Hac1p binds to UPRE after unfolded proteins accumulate in the ER. However, in mammals, there are several ER-to-nucleus signaling pathways related to the UPR, and different bZIP transcription factors are required (XBP-1, ATF6, and ATF4).

In mammalian cells, 1% of the genome is induced as part of the UPR, and the genes can be grouped into four signal transduction pathways. (1) Induction of genes that encode chaperones and other proteins that aid protein folding is mediated through the membrane-associated transcription factor ATF6. ATF6 mainly recognizes and binds to the cis-acting elements ERSE-I and ERSE-II of chaperones and other target genes. (2) Attenuation of protein translation through the ER membrane-bound protein PERK, which phosphorylates the eukaryotic translation initiation factor eIF2α. This signaling has two secondary effects: first, the transcription factor ATF4 is upregulated, so the expression of amino acid biosynthesis enzymes is induced indirectly when ATF4 binds to amino acid response element (AARE) motifs in the promoters of genes that encode such enzymes (Harding et al., 2000); second, selective stimulation of a m(7)G-cap–independent translation mechanism of mRNAs that contain internal ribosome entry sites within their 5′ untranslated regions, such as the cationic amino acid transporter cat-1 (Fernandez et al., 2002). (3) Upregulation of some other UPR-specific targets by the transcription factor XBP-1, which becomes active by a rare splicing event performed by Ire1 (Yoshida et al., 2001). XBP-1 is able to recognize both ERSE and UPRE regulatory sequences. Therefore, under conditions of ER stress, the active form of the transcription factor XBP-1 binds to UPRE, ATF6 binds to CCACG of ERSE-II and to ERSE-I, and ATF4 binds to AARE (Okada et al., 2002). ATF6 needs the interaction of some other partners, such as the general transcription factors NF-Y/CBF (Yoshida et al., 1998) or TFII-I (Parker et al., 2001), for a complete functional UPR. (4) Induction of apoptosis through two independent pathways: activation of the caspase pathway (Rao et al., 2001) and of another bZIP transcriptional factor, CHOP (Zinszner et al., 1998). Furthermore, in mammals, there is cross-talk between different UPR-related signaling paths. Thus, the expression of CHOP and of the protein OS-9 can be induced by either the ATF6 or the PERK pathway (Okada et al., 2002), whereas XBP-1 expression is induced by either ATF6 or Ire1–XBP-1 sig-naling (Yoshida et al., 2001). Homologs of ATF6, PERK, or hac1/XBP-1 have not been found to date in Arabidopsis.

Here, we report gene expression analysis studies showing the breadth of the UPR in Arabidopsis. On the basis of our results, we suggest that ER stress caused by unfolded proteins may evoke a triple response from the cell: (1) upregulation of chaperones and vesicle trafficking; (2) upregulation of the degradation of unwanted unfolded proteins (ERAD); and (3) attenuation of genes that encode secretory (mostly cell wall) proteins. We also identify potential DNA cis elements that may be responsible for the gene upregulation caused by ER stress. Unlike the situation in yeast, no single response element is associated with the UPR in Arabidopsis, and the response elements in the BiP promoter are not representative of those found in other UPR regulated genes.

RESULTS

Setting Up the Gene Expression Analysis

To gain further insight into the UPR of plant cells, we monitored the transcriptional targets of this signaling pathway using nucleotide arrays on Affymetrix GeneChips. The UPR was induced by treating young Arabidopsis plants with two chemicals, tunicamycin and DTT, that cause protein misfolding in the ER by different mechanisms. Using two different chemicals, we expected to eliminate nonspecific effects that are caused by one chemical and to identify those genes whose regulation is part of the UPR (Travers et al., 2000).

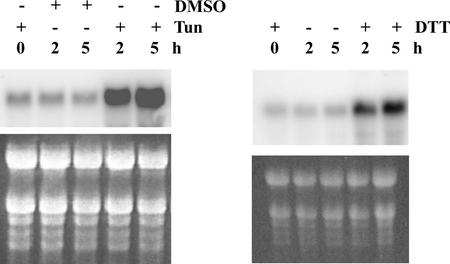

Initially, 10 RNA samples were prepared from control plants and from plants treated for 2 and 5 h with 5 μg/mL tunicamycin or 10 mM DTT. To determine if these RNA samples reflect a normal UPR of the plants, we took advantage of the previously described upregulation of BiP as a part of the UPR (Denecke et al., 1991; Fontes et al., 1991). RNAs were examined by RNA gel blot analysis using BiP2 cDNA as a probe (Figure 1). Although we used BiP2 cDNA as a template to label the probe, both BiP1 and BiP2 mRNA are detected by this analysis, because the coding sequences of the two genes are 97% identical. Both treatments, tunicamycin and DTT, increased BiP expression markedly, whereas there was no increase in the control plants. BiP induction appeared lower with DTT treatment than with the tunicamycin treatment. All treatments were performed in liquid-grown plants because we determined previously that other treatment methods (i.e., transfer of plants grown on filters) invariably resulted in an increase of BiP expression in the control plants.

Figure 1.

Expression of Arabidopsis BiP Genes after Treatment with Tunicamycin and DTT.

Six-day-old Arabidopsis seedlings growing in liquid were treated with 5 μg/mL tunicamycin (Tun) or 10 mM DTT for 2 or 5 h. Control assays were performed at 0, 2, and 5 h. Tunicamycin was added to the 0-h control, and DMSO was added to the 2- and 5-h controls. Total RNA was fractionated on a formaldehyde-agarose gel, transferred onto a nylon membrane, and then hybridized with 32P-labeled AtBiP2 probe. Ethidium bromide staining under UV light was used to evaluate equal loading (bottom gels).

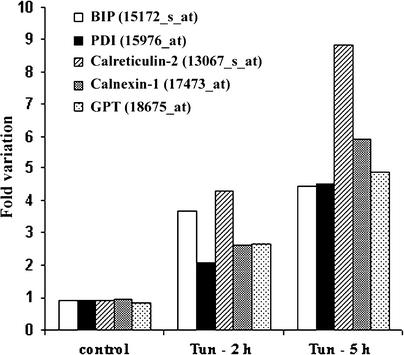

For each of the 8297 probe sets on the Affymetrix GeneChip, 10 measurements were obtained: two for the initial condition (0 h), four for the control condition (2 and 5 h), two for the tunicamycin treatment (2 and 5 h), and two for the DTT treatment (2 and 5 h). In total, six control and four treated samples were used for hybridization with the Affymetrix GeneChips. To ensure the reliability and determine the reproducibility of the microarray analysis, we first calculated Pearson correlation factors using the average dif-ference (expression intensities) from all of the control con-ditions (Table 1). All six control arrays have Pearson correlation coefficients of >0.95, which suggests an excellent reproducibility among individual arrays in the same experiment and between experiments. Second, expression profiles of well-known ER-resident UPR upregulated genes present on the Affymetrix GeneChips were analyzed. Because there is only one probe set for BiP and a high sequence identity between the two Arabidopsis BiP gene sequences, we did not distinguish between AtBiP1 and AtBiP2 in the microarray analysis, and we refer to them as BiP. The increases of RNA levels for BiP, PDI (At1g21750), calreticulin2 (At1g09210), calnexin1 (At5g61790), and UDP-N-acetylglucosamine-dolichol phosphate-N-acetylglucosamine-phosphotransferase (GPT; At2g41490) in the tunicamycin experiment are represented in Figure 2. Increasing mRNA levels for all five genes were detected at 2 and 5 h, with some differences in the kinetics of induction. Similar results were obtained in the DTT experiment (data not shown). We refer to the set of four genes—BiP, At1g21750, At1g09210, and At5g61790—as the UPR control genes.

Table 1.

Pearson Correlation Coefficients of the Average Difference for All of the Controls

| T0 | T2 | T5 | D0 | D2 | D5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T0 | – | 0.987 | 0.979 | 0.963 | 0.964 | 0.966 |

| T2 | 0.987 | – | 0.979 | 0.957 | 0.057 | 0.960 |

| T5 | 0.979 | 0.979 | – | 0.954 | 0.954 | 0.951 |

| D0 | 0.963 | 0.957 | 0.954 | – | 0.994 | 0.994 |

| D2 | 0.964 | 0.957 | 0.954 | 0.994 | – | 0.995 |

| D5 | 0.966 | 0.960 | 0.951 | 0.994 | 0.995 | – |

T, control tunicamycin; D, control DTT; numbers represent time in hours.

Figure 2.

Effect of Tunicamycin on the Expression of Known Arabidopsis UPR Genes as Shown by Affymetrix GeneChip Data.

Fold variation in controls for each gene was calculated as the average of three conditions: 0 h treated with tunicamycin (Tun) and 2 and 5 h treated with DMSO. Affymetrix codes are shown in parentheses.

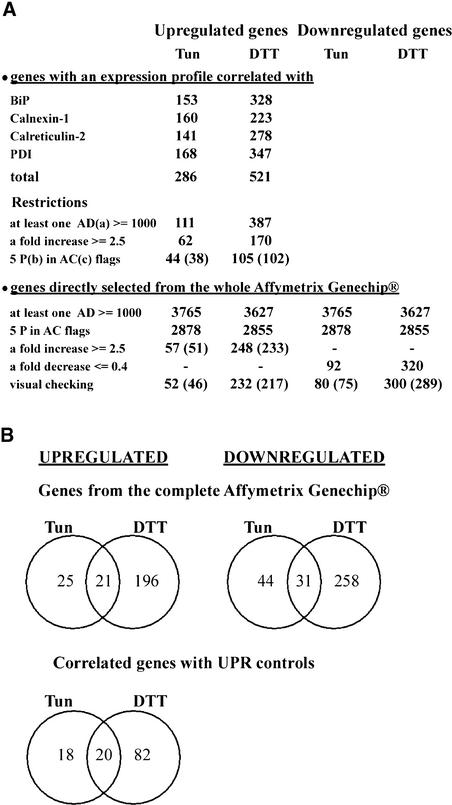

We then proceeded with the global analysis of the 8341 probe sets on the Affymetrix GeneChip. Expression profiles of the four upregulated UPR control genes mentioned above were used to identify those genes present on the Affymetrix GeneChip that have a similar expression pattern with a Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.95 or greater (Figure 3A). The lists were combined, and the total upregulated gene set was 286 for tunicamycin and 521 for DTT. Genes that have a very low expression level may easily show a large increase because of errors in measuring the baseline expression. Therefore, we increased the stringency criteria by first eliminating all probe sets for which the average difference values were <1000 for the five conditions (treated zero time, two treatments, and two control values) for each of the tunicamycin and DTT experiments. This left 111 genes for the tunicamycin treatment and 387 genes for the DTT treatment. We then applied two other restrictive criteria. We selected only those genes that had five P (present) in the absolute call flag (see Methods) of all five conditions and that had an induction of at least 2.5-fold in one of the five conditions (1000-5P-2.5) of each treatment. Finally, on the Affymetrix GeneChip, some probe sets are represented more than once, so duplicated probe sets were eliminated by visual inspection of the list of genes. This resulted in a list of induced genes with 38 independent entries for the tunicamycin treatment and 102 entries for the DTT treatment.

Figure 3.

Overview of the DNA Array Profiles of Upregulated and Downregulated Genes for the Tunicamycin and DTT Experiments.

(A) Abundance of probe sets and independent genes (in parentheses) with different selection criteria. Pearson correlation (P = 0.95) was used to search genes with expression patterns similar to those of the four UPR control genes in Figure 2. AC, absolute call; AD, average difference; P, present; Tun, tunicamycin.

(B) Venn diagrams of the numbers of overlapping and nonoverlapping induced or repressed genes on the array after treatment with tunicamycin (Tun) or DTT meeting the 1000-5P-2.5 or 1000-5P-0.4 restriction criteria.

To identify possible novel targets of the tunicamycin-dependent UPR with expression profiles that are different from that shown by the four upregulated UPR control genes (i.e., genes upregulated only at 2 or 5 h), we analyzed the whole Affymetrix GeneChip by applying the 1000-5P-2.5 criteria (Figure 3A). The gene sets identified with these restrictions constituted 46 and 217 independent entries for the tunicamycin and DTT treatments, respectively.

We searched the Affymetrix GeneChip expression data for downregulated genes, changing one of the three restriction criteria from 2.5-fold induction to 2.5-fold inhibition (expression level of 0.4 compared with the control) in at least one of the five conditions (1000-5P-0.4). Seventy-five independent genes were downregulated by tunicamycin and 289 genes were downregulated by DTT (Figure 3A). Lists of the upregulated and downregulated genes can be found at http://www.biology.ucsd.edu/others/chrispeels/LabHomePage.html.

The Affymetrix GeneChip has 8297 probe sets; subtracting the 41 non-Arabidopsis probe set controls, Arabidopsis probe sets not associated with a locus in the genome (336), and repeated Arabidopsis probe sets (548) decreases the total to 7372 independent Arabidopsis genes. This means that tunicamycin globally regulates ∼1.6% of the Arabidopsis genes, whereas DTT regulates 6.9% of the genes when 1000- 5P-2.5 and 1000-5P-0.4 restriction criteria are considered.

Expression Profile Analysis of UPR Induced and Repressed Genes

To avoid including genes that may be induced by these two chemical stress reagents (tunicamycin and DTT) but that are not related to the UPR, we determined the overlap of the gene sets identified with the two treatments. The Venn diagrams shown in Figure 3B show the overlap between the independent probe sets induced or repressed by the two treatments. From the analysis of the whole Affymetrix GeneChip, we found an overlap between the two treatments of 21 upregulated genes and 31 downregulated genes. Thus, a substantial number of the genes upregulated and downregulated by one of the two stress-inducing chemicals may not be related to the UPR. Using the gene set with expression patterns correlated with any of the four control gene expression profiles, we found an overlap of 20 upregulated genes. This set of 20 genes is contained entirely within the set of 21 overlap genes identified above, showing the redundancy of the two approaches to finding the correct genes.

Table 2 shows the list of 46 1000-5P-2.5 tunicamycin-upregulated genes, the corresponding fold variation after 2 and 5 h of tunicamycin or control treatment, and the results obtained in the DTT experiment for the same genes. Thus, this table shows the overlap genes and the genes that were upregulated by tunicamycin but not by DTT. Not all of the genes that were upregulated by DTT are shown (a complete list is available in the supplemental data online). It is readily apparent that many aspects of secretory pathway function are induced by tunicamycin. We observed genes for protein folding (10 genes), for glycosylation and the synthesis and modification of glycans (5 genes), for the translocation of polypeptides into or out of the lumen of the ER (3 genes), for protein degradation (2 genes), for vacuolar residents (2 genes), and for vesicle trafficking (4 genes). In addition, we found two protein kinases, two proteins related to jasmonate signaling, five stress-related proteins, two transcription factors, three chloroplast residents, and six other proteins.

Table 2.

Expression Profiles of Tunicamycin-Upregulated Genes and the Corresponding Results in the DTT Experiment

| Tunicamycin FVb

|

DTT

|

|||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 2+ | 2 | 5+ | 5 | 0

|

2+

|

2

|

5+

|

5

|

|||||||||

| BAC | Affymetrix Code | Description | Taga | FV | Fc | FV | F | FV | F | FV | F | FV | F | |||||

| Protein folding | ||||||||||||||||||

| chaperones | ||||||||||||||||||

| T12M4.8 | 13067_s_at | Calreticulin2 | OL-LS | 1.0 | 4.3 | 0.9 | 8.8 | 1.0 | 1.0 | P | 2.1 | P | 1.0 | P | 2.3 | P | 0.7 | P |

| F7J7.120 | 15026_at | Similar to heat shock dnaJ homolog | OL-HS | 0.9 | 1.8 | 0.8 | 3.7 | 1.0 | 1.0 | P | 2.2 | P | 0.8 | P | 2.8 | P | 0.8 | P |

| D89341/2 | 15172_s_at | Luminal binding protein, BiP | OL-HS | 0.9 | 3.7 | 0.8 | 4.5 | 1.0 | 1.0 | P | 4.3 | P | 1.0 | P | 4.6 | P | 0.8 | P |

| T19F6.1 | 16448_g_at (D2T2)d | HSP90 isolog | OL-HS | 0.8 | 3.6 | 0.7 | 7.6 | 1.0 | 1.0 | P | 2.3 | P | 0.9 | P | 2.9 | P | 0.9 | P |

| MAC9.11 | 17473_at | Calnexin, CNX1 | OL-HS | 1.0 | 2.6 | 1.0 | 5.9 | 0.9 | 1.0 | P | 5.2 | P | 0.9 | P | 4.3 | P | 1.0 | P |

| T2I1.50 | 17924_at | Calnexin homolog | OL-HS | 1.0 | 3.7 | 0.9 | 6.7 | 1.0 | 1.0 | P | 4.0 | P | 0.9 | P | 3.1 | P | 1.0 | P |

| Disulfide bond formation | ||||||||||||||||||

| F28P10.60 | 14036_at | PDI-like protein | NOL | 1.0 | 1.1 | 0.9 | 3.1 | 0.8 | 1.1 | P | 1.0 | P | 1.0 | P | 1.6 | P | 0.8 | P |

| F8K7.19 | 15976_at | Similar to PDI | NOL | 0.8 | 2.1 | 0.9 | 4.5 | 1.0 | 1.0 | P | 1.4 | P | 0.9 | P | 1.6 | P | 0.8 | P |

| T30B22.23 | 17398_at | Putative PDI | OL-HS | 1.0 | 1.7 | 0.6 | 5.0 | 0.8 | 1.0 | P | 1.8 | P | 0.9 | P | 3.3 | P | 1.0 | P |

| T21L14.14 | 19457_at | Putative PDI | OL-HS | 0.9 | 3.2 | 1.0 | 6.8 | 0.6 | 1.0 | P | 3.9 | P | 0.8 | P | 5.6 | P | 1.0 | P |

| Translocon/protein degradation | ||||||||||||||||||

| T18E12.21 | 12042_at | Signal peptide peptidase-like | OL-LS | 1.0 | 1.9 | 0.9 | 5.4 | 0.9 | 1.0 | P | 1.6 | P | 1.0 | P | 2.2 | P | 0.9 | P |

| F13P17.9 | 13102_at | Putative protein transport protein SEC61 α-subunit | NOL | 0.9 | 2.6 | 0.8 | 3.3 | 1.0 | 0.9 | P | 1.3 | P | 1.0 | P | 1.7 | P | 0.9 | P |

| T14P1.12 | 16950_s_at (D2T2)d | sec61 β-subunit homolog | OL-HS | 1.0 | 4.3 | 0.9 | 2.7 | 0.7 | 1.0 | P | 2.4 | P | 0.8 | P | 2.6 | P | 1.0 | P |

| F13M23.60 | 17882_at | Protein transport protein sec61 γ-subunit-like | OL-HS | 1.0 | 3.5 | 0.9 | 3.6 | 0.9 | 1.0 | P | 3.6 | P | 1.0 | P | 4.2 | P | 1.0 | P |

| F8D23.3 | 20475_at | Putative AAA-type ATPase | OL-LS | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.9 | 3.3 | 1.2 | 0.6 | A | 1.8 | P | 0.6 | P | 4.3 | P | 1.0 | P |

| Glycosylation/modification | ||||||||||||||||||

| T3D7.1 | 13134_s_at | Putative galactinol synthase | OL-LS | 1.0 | 0.7 | 0.9 | 2.5 | 1.0 | 1.0 | P | 1.6 | P | 1.0 | P | 4.4 | P | 0.8 | A |

| F4I18.23 | 14061_at | Putative phosphomannomutase | NOL | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 2.8 | 0.6 | 0.9 | P | 1.6 | P | 1.0 | P | 1.7 | P | 1.0 | P |

| T20F6.5 | 14381_at | UDP-galactose transporter, AtUtr1 | OL-HS | 1.0 | 5.0 | 0.6 | 8.7 | 0.7 | 0.9 | P | 6.6 | P | 1.0 | P | 6.8 | P | 1.0 | P |

| T12J13.8 | 17109_s_at | β-Glucosidase | NOL | 1.0 | 0.9 | 1.1 | 11.9 | 0.9 | 1.2 | P | 0.9 | P | 1.0 | P | 1.0 | P | 1.0 | P |

| T32G6.1 | 18675_at (D1T2)d | GPT | OL-HS | 1.0 | 3.2 | 0.4 | 6.1 | 0.9 | 0.8 | P | 1.5 | P | 1.0 | P | 3.1 | P | 0.9 | P |

| Vacuolar | ||||||||||||||||||

| F4F15.300 | 13123_at | Simxilar to St12p protein | OL-HS | 0.8 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 2.6 | 0.6 | 1.0 | P | 2.0 | P | 1.0 | P | 2.6 | P | 0.9 | P |

| F9K20.2 | 20229_at | Similar to vacuolar H+-pyrophosphatase | OL-LS | 1.0 | 1.5 | 0.9 | 2.7 | 0.9 | 0.8 | P | 1.1 | P | 1.0 | P | 2.1 | P | 0.8 | P |

| Vesicle/trafficking | ||||||||||||||||||

| F12F1.27 | 19212_at | Similar to vesicle trafficking protein | OL-HS | 0.9 | 1.9 | 1.0 | 3.7 | 0.7 | 1.0 | P | 1.8 | P | 0.8 | P | 3.2 | P | 0.8 | P |

| F8K4.21 | 19648_at | Similar to coatomer α-subunit (HEPCOP) homolog | OL-HS | 1.0 | 1.9 | 1.0 | 2.8 | 0.9 | 1.0 | P | 2.9 | P | 1.0 | P | 3.5 | P | 1.0 | P |

| F7A19.10 | 20069_at | Putative Golgi-associated membrane trafficking protein | NOL | 0.9 | 0.8 | 1.0 | 3.3 | 1.0 | 0.9 | P | 0.9 | P | 1.0 | P | 1.4 | P | 1.0 | P |

| F13D4.70 | 14078_at | Similar to mouse stromal cell-derived factor 2 | OL-HS | 1.0 | 2.6 | 1.0 | 3.9 | 1.0 | 0.9 | P | 2.6 | P | 0.8 | P | 3.3 | P | 1.0 | P |

| Kinases | ||||||||||||||||||

| F9L1.42 | 15438_at | Ser/Thr kinase receptor-associated protein | NOL | 1.0 | 2.6 | 0.8 | 1.4 | 1.0 | 2.1 | P | 0.9 | P | 1.4 | P | 0.4 | P | 1.0 | P |

| F22O13.13 | 19692_at | Putative calcium-dependent protein kinase | OL-HS | 1.0 | 0.6 | 2.0 | 3.3 | 0.9 | 0.4 | P | 1.0 | P | 0.6 | P | 2.5 | P | 1.4 | P |

| Jasmonate related | ||||||||||||||||||

| F9D16.70 | 14832_at | Tyrosine transaminase-like protein | NOL | 1.0 | 2.8 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 1.3 | 0.5 | P | 1.2 | P | 1.0 | P | 0.7 | P | 1.0 | P |

| T02O04.7 | 15996_at | Jasmonate-inducible protein isolog | NOL | 1.0 | 3.7 | 1.3 | 1.0 | 0.6 | 2.5 | P | 0.2 | A | 1.4 | P | 0.0 | A | 1.0 | P |

| Stress related | ||||||||||||||||||

| T17M13.16 | 17014_s_at | Secreted ribonuclease 1, RNS1 | NOL | 0.8 | 2.5 | 1.0 | 1.8 | 1.0 | 1.2 | P | 0.6 | P | 1.0 | P | 0.5 | P | 1.0 | P |

| F22H5.18 | 17865_at | Isoflavonoid reductase homolog | NOL | 1.0 | 0.9 | 1.1 | 2.5 | 0.9 | 0.8 | P | 1.6 | P | 1.3 | P | 1.0 | P | 0.9 | P |

| F1N13.110 | 18699_i_at (T3)d | Cold-regulated, cor6.6 | NOL | 1.0 | 1.8 | 0.3 | 3.1 | 1.0 | 0.8 | P | 1.7 | P | 1.0 | P | 1.6 | P | 1.0 | P |

| T20B5.8 | 18954_at | Putative cysteine proteinase inhibitor B | NOL | 1.0 | 1.4 | 1.0 | 6.2 | 0.7 | 1.0 | P | 1.0 | P | 0.9 | P | 1.4 | P | 1.1 | P |

| F14N23.25 | 20060_at | Similar to glutathione S-transferase TSI-1 | OL-LS | 1.0 | 2.5 | 1.0 | 1.8 | 0.7 | 1.0 | P | 1.8 | P | 0.8 | P | 2.3 | P | 1.0 | P |

| Transcription factors | ||||||||||||||||||

| MXC7.6 | 13297_at | Auxin-responsive protein IAA2 | NOL | 1.2 | 0.8 | 1.0 | 3.0 | 0.7 | 1.5 | P | 1.5 | P | 0.7 | A | 1.0 | P | 0.5 | P |

| F17L21.14 | 20032_at | Protein with squamosa promoter binding domain | OL-HS | 1.0 | 3.0 | 1.0 | 5.5 | 0.7 | 1.0 | P | 3.8 | P | 1.0 | P | 4.0 | P | 1.0 | P |

| Chloroplast residents | ||||||||||||||||||

| F27I1.2 | 17054_s_at | Lhcb4:3 protein | NOL | 0.8 | 2.0 | 1.0 | 2.7 | 0.7 | 0.6 | P | 1.3 | P | 1.0 | P | 1.2 | P | 0.8 | P |

| F11A3.19 | 18665_r_at | Photosystem I subunit IV precursor | NOL | 1.5 | 1.0 | 0.9 | 2.9 | 0.8 | 1.7 | P | 1.0 | A | 0.9 | A | 1.0 | A | 1.4 | P |

| FCAALL.5 | 18670_g_at | Chloroplast-targeted β-amylase enzyme | NOL | 1.1 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 2.5 | 0.8 | 1.0 | P | 1.0 | P | 0.9 | P | 0.2 | P | 1.2 | P |

| Unclassified | ||||||||||||||||||

| T20K18.70 | 13177_at | Growth factor-like protein with mutT domain | OL-HS | 0.8 | 1.4 | 1.0 | 3.0 | 0.9 | 1.0 | P | 8.1 | P | 0.7 | P | 14.4 | P | 0.7 | P |

| T8O5.20 | 13591_at (D2T2)d | Similar to NADH dehydrogenase chain 4 | OL-HS | 1.0 | 3.6 | 0.7 | 6.2 | 0.6 | 1.0 | P | 4.1 | P | 0.7 | P | 5.8 | P | 0.9 | P |

| T20G20.2 | 15004_at | Putative microtubule-associated protein | NOL | 1.0 | 1.2 | 0.8 | 2.9 | 0.9 | 0.7 | P | 1.2 | P | 1.0 | P | 1.8 | P | 0.8 | P |

| F13H10.22 | 15839_at | Unknown protein | OL-HS | 0.7 | 1.4 | 0.9 | 4.3 | 1.0 | 1.0 | P | 3.4 | P | 0.5 | P | 10.4 | P | 0.5 | P |

| T16L4.30 | 16311_at | Unknown protein | OL-LS | 0.8 | 5.9 | 1.0 | 16.1 | 0.9 | 0.8 | A | 6.5 | P | 1.0 | P | 6.1 | P | 0.9 | P |

| T4L20.210 | 20178_at | Unknown protein | OL-HS | 1.0 | 4.6 | 1.0 | 5.4 | 0.9 | 0.8 | P | 8.8 | P | 0.9 | P | 4.4 | P | 1.0 | P |

OL-HS, overlapping genes at high-stringency criteria; OL-LS, overlapping genes at low-stringency criteria; NOL, no overlapping genes.

FV, fold variation. Boldface numbers indicate genes meeting the 1000-5P-2.5 criteria. Italicized boldface numbers indicate genes that were identified when lower stringency criteria were used (1000-3P-2).

F, absolute call flags: P, present; M, marginal; A, absent.

Numbers of replicas on the Affymetrix GeneChip for this gene meeting the restrictions in tunicamycin (T) and DTT (D) are shown in parentheses.

Among the 46 1000-5P-2.5 tunicamycin-upregulated genes, only 21 also were induced by DTT at 2 or 5 h using the same stringency criteria. The 21 genes meeting the 1000-5P-2.5 criteria in both treatments (overlap genes) are marked as overlap/high stringency (OL-HS) in Table 2. Most of the same categories mentioned above still are represented in the overlap list of 21 genes. However, the jasmonate-related genes, the stress-related genes, and the chloroplast residents do not appear on the overlap list. These genes may be induced as a result of tunicamycin treatment but may not be involved in the protein-folding response. Thus, the genes that remain on the list encode mostly chaperones, glycosylation enzymes, vesicle traffic proteins, and proteins that are part of the ERAD system, as well as six genes in the other categories.

Given the low number of UPR-regulated genes detected using these high-stringency criteria, it is possible that some differentially expressed genes may have been eliminated. For this reason, we decreased the stringency for the second and third restriction criteria as follows: (1) 2 P in absolute call flags instead of 5 P; and (2) a minimum of twofold increased variation for at least one condition in the upregulated genes (1000-2P-2). The overlap list increased from 21 to 53 genes; 7 of the additional 32 genes are marked as overlap/low stringency (OL-LS) in Table 2, and the rest (25) are shown in Table 3. The same functional categories are found among the new genes, with the addition of six new transcription factors (Zat12, WRKY-like, AtGATA-1, hap5b, ATAF2, and a putative ring zinc finger protein) and seven new ER-related proteins (a protein transport factor, a glucosyltransferase, non-KDEL BiP-like, OS-9–like, peroxidase ATP24, SAR1B, and ER-Ca2+-ATPase4).

Table 3.

Added UPR Upregulated Genes Meeting the 1000-3P-2 Restriction Criteria

| Tunicamycin

|

DTT

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0

|

2+

|

2

|

5+

|

5

|

0

|

2+

|

2

|

5+

|

5

|

||||||||||||||

| AGI Gene | BAC | Affymetrix Code |

Description | FV | F | FV | F | FV | F | FV | F | FV | F | FV | F | FV | F | FV | F | FV | F | FV | F |

| At1g09080 | F7G19.5 | 16364_at | BiP-like | 1.0 | A | 83.7 | P | 0.3 | A | 339.5 | P | 0.0 | A | 0.0 | A | 8.3 × 105 | P | 0.0 | A | 1.8 × 106 | P | 0.0 | A |

| At1g09180 | T12M4.12 | 17417_at | Putative GTP-binding protein SAR1B |

0.8 | A | 13.9 | P | 1.0 | A | 29.2 | P | 0.5 | A | 1.0 | A | 32.6 | P | 0.4 | A | 48.9 | P | 0.4 | A |

| At4g16660 | FCAALL.64 | 18140_at | HSP-like (D2T2)a | 1.0 | P | 3.8 | P | 0.8 | A | 10.9 | P | 0.5 | A | 1.0 | P | 3.5 | P | 0.7 | P | 5.1 | P | 0.4 | A |

| At2g46500 | F13A10.3 | 18268_s_at | Putative ubiquitin | 1.0 | A | 3.6 | P | 0.9 | A | 5.4 | P | 0.7 | A | 1.0 | P | 5.8 | P | 0.7 | P | 11.5 | P | 0.7 | M |

| At5g35080 | F7N22.4 | 14471_at | Contains similarity to human OS-9 |

0.9 | A | 3.6 | P | 1.0 | A | 7.0 | P | 0.7 | A | 1.0 | P | 4.9 | P | 0.9 | A | 6.0 | P | 0.8 | A |

| At4g19880 | T16H5.240 | 16299_at | Putative GST | 0.9 | M | 3.2 | P | 1.0 | P | 1.9 | P | 0.6 | P | 0.0 | P | 2.9 × 105 | P | 0.0 | P | 1.6 × 106 | P | 0.0 | A |

| At4g01810 | T7B11.7 | 13600_at | Putative protein transport factor |

1.0 | A | 2.3 | P | 0.8 | A | 3.7 | P | 0.0 | A | 0.7 | P | 2.1 | P | 0.8 | P | 2.5 | P | 1.0 | P |

| At4g11800 | T26M18.10 | 15774_at | Unknown protein | 0.9 | P | 2.2 | P | 0.8 | M | 2.1 | P | 1.0 | M | 0.8 | P | 1.3 | P | 0.6 | P | 3.0 | P | 1.0 | P |

| At2g16060 | F7H1.8 | 17832_at | Class 1 nonsymbiotic hemoglobin AHB1 |

0.5 | M | 2.2 | P | 1.0 | P | 1.2 | P | 1.0 | A | 1.0 | P | 2.0 | P | 0.6 | P | 6.1 | P | 0.7 | P |

| At3g24050 | F14O13.7 | 18246_at | GATA transcription factor AtGATA-1 |

1.0 | P | 2.2 | P | 1.0 | P | 1.6 | P | 0.8 | P | 0.9 | P | 1.8 | P | 1.0 | P | 2.3 | P | 0.9 | P |

| At1g56170 | F14G9.21 | 19860_at | Transcription factor hap5b |

0.9 | P | 2.1 | P | 0.8 | P | 3.1 | P | 1.0 | A | 0.3 | A | 1.7 | P | 0.6 | P | 2.8 | P | 1.0 | P |

| At4g15550 | FCAALL.103 | 16603_s_at | UDP-Glucose:indole-3- acetate β-d-gluco- syltransferase |

1.0 | P | 1.6 | P | 0.9 | P | 2.3 | P | 0.9 | P | 1.0 | P | 4.8 | P | 0.9 | P | 4.3 | P | 0.9 | P |

| At1g67360 | F1N21.36 | 19944_at | Stress-related protein, putative |

1.0 | P | 1.4 | P | 0.7 | P | 2.0 | P | 0.6 | M | 1.0 | A | 1.6 | P | 0.8 | P | 2.4 | P | 0.7 | P |

| At4g26400 | M3E9.170 | 19176_at | Putative ring zinc finger protein |

1.0 | P | 1.4 | P | 0.8 | P | 2.2 | P | 1.0 | P | 1.0 | P | 3.1 | P | 0.9 | P | 3.3 | P | 0.9 | P |

| At4g14430 | FCAALL.43 | 19366_at | Carnitine racemase-like protein |

1.0 | P | 1.4 | P | 1.0 | P | 2.2 | P | 1.0 | P | 0.9 | P | 1.8 | P | 1.0 | P | 2.6 | P | 1.0 | P |

| At2g38470 | T19C21.4 | 17303_s_at | AtWRKY-33 | 0.5 | P | 1.4 | P | 0.5 | P | 2.1 | P | 1.0 | P | 1.0 | P | 21.2 | P | 0.1 | A | 31.8 | P | 0.2 | P |

| At1g07670 | F24B9.24 | 20215_s_at | ER-type calcium- transp. ATPase4 |

1.0 | P | 1.2 | P | 1.0 | P | 2.3 | P | 1.0 | P | 1.0 | P | 1.8 | P | 1.0 | P | 2.1 | P | 1.0 | P |

| At5g59820 | MMN10.11 | 13015_s_at | Zinc finger protein Zat12 |

0.8 | P | 1.0 | P | 1.2 | P | 4.7 | P | 0.1 | A | 1.0 | P | 24.1 | P | 0.3 | A | 45.7 | P | 0.5 | P |

| At2g18690 | MSF3.7 | 17894_at | Unknown protein | 0.7 | P | 1.0 | P | 0.8 | P | 2.2 | P | 1.1 | P | 1.0 | P | 4.0 | P | 0.3 | P | 16.6 | P | 0.4 | A |

| At4g02880 | T5J8.20 | 18623_at | Unknown protein | 0.7 | M | 1.0 | A | 1.0 | M | 3.0 | P | 1.6 | P | 0.8 | P | 1.8 | P | 0.7 | P | 5.5 | P | 1.0 | P |

| At2g44080 | F6E13.24 | 12150_at | Unknown protein | 1.0 | P | 1.0 | P | 1.3 | P | 2.4 | P | 1.0 | P | 1.0 | P | 2.2 | P | 0.5 | P | 2.3 | P | 0.5 | P |

| At1g31130 | F28K20.6 | 12092_at | Unknown protein | 1.0 | P | 0.9 | P | 1.2 | P | 2.4 | P | 0.5 | A | 0.9 | P | 1.6 | P | 0.9 | P | 3.0 | P | 1.0 | P |

| At5g39580 | MIJ24.50 | 18946_at | Peroxidase ATP24a | 1.0 | P | 0.7 | A | 1.0 | P | 2.3 | P | 0.9 | P | 1.0 | P | 4.5 | P | 0.2 | M | 3.3 | P | 0.3 | P |

| At5g08790 | T2K12.21 | 18591_at | ATAF2 | 0.7 | P | 0.6 | P | 1.5 | P | 2.3 | P | 1.0 | P | 1.0 | P | 12.9 | P | 0.4 | P | 19.4 | P | 0.4 | A |

| At4g10040 | T5L19.170 | 19624_at | Cytochrome c | 1.0 | P | 0.6 | P | 1.0 | P | 2.0 | P | 0.5 | M | 0.5 | P | 1.6 | P | 0.6 | P | 3.6 | P | 1.0 | P |

Genes meeting the fold variation criterion of >2.5 are boldface and those between 2.5 and 2 are italicized boldface. FV, fold variation; F, absolute call flag; P, present; M, marginal; and A, absent.

Numbers of replicas on the Affymetrix GeneChip for this gene meeting the restrictions in tunicamycin (T) and DTT (D) are shown in parentheses.

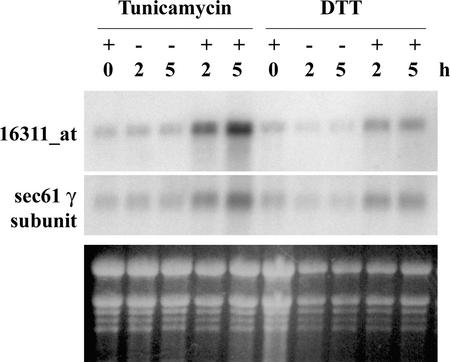

We confirmed the expression profile results of two additional Arabidopsis UPR upregulated genes (γ-subunit of sec61 and an unknown protein with the Affymetrix code 16311_at) by RNA gel blot analysis and found that the results agree with those of the expression analysis (Figure 4). Both labeled probes were used simultaneously to hybridize the same nylon membrane because the sizes of the predicted mRNAs were quite different.

Figure 4.

RNA Gel Blot Analysis Confirms Two UPR Genes Identified by Expression Analysis.

RNA gel blots were made with the same RNA samples that were used to collect the microarray data. Total RNA was fractionated on a formaldehyde-agarose gel, transferred onto a nylon membrane, and then hybridized with each 32P-labeled specific probe: the coding sequence of the γ-subunit of sec61 or the putative gene with Affymetrix code 16311_at. Ethidium bromide staining under UV light was used to evaluate loading (bottom gel).

The 31 genes repressed by both tunicamycin and DTT and meeting the 1000-5P-0.4 criteria are listed in Table 4 and grouped according to function. Only 2 of the 31 genes are predicted not to have signal peptides (At4g37470 and At4g00400). The other 29 genes are predicted to have cleaved or uncleaved signal peptides and many are secretory pathway related, suggesting that downregulation of secreted proteins may be an important component of the UPR. Lowering the criteria (1000-3P-0.5) increases the list to 129 independent genes (this list is available at http://www-biology.ucsd.edu/others/chrispeels/LabHomePage.html). Among these 129 genes, 82% of the encoded proteins have signal peptides. There are 9 peroxidases, 3 peptide transporters, 8 sugar-related genes, 33 cell wall–related genes, 8 proteases (5 carboxypeptidases), 3 transcription factors, 5 channel proteins (4 aquaporins), 6 lipid-related proteins, 2 gibberellic acid–stimulated transcripts, and 6 cytochrome P450s.

Table 4.

Fold Variations of UPR-Downregulated Genes

| Tunicamycin

|

DTT

|

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AGI Gene | BAC | Affymetrix Code | Description | 0 | 2+ | 2 | 5+ | 5 | 0 | 2+ | 2 | 5+ | 5 |

| Secretory pathway | |||||||||||||

| Extracellular or cell wall related | |||||||||||||

| At3g14310 | MLN21.10 | 12338_at | Pectin methylesterase, PM3 | 1.1 | 0.4 | 1.0 | 0.3 | 1.1 | 1.0 | 0.1 | 1.2 | 0.1 | 1.0 |

| At2g38540 | T6A23.26 | 12754_g_at | Nonspecific lipid transfer protein | 1.0 | 0.8 | 1.0 | 0.3 | 1.3 | 1.1 | 0.3 | 1.2 | 0.2 | 1.0 |

| At2g45470 | F4L23.2 | 12787_at | Endosperm-specific/arabinogalactan-like | 1.1 | 0.6 | 1.0 | 0.3 | 1.2 | 1.1 | 0.1 | 1.1 | 0.1 | 1.0 |

| At1g78820 | F9K20.13 | 13085_i_at (D2T2)a | Similar to glycoprotein EP1 | 1.0 | 0.4 | 1.1 | 0.3 | 1.0 | 1.3 | 0.2 | 1.0 | 0.2 | 1.2 |

| At4g38770 | T9A14.50 | 13120_at | Proline-rich protein | 1.0 | 0.5 | 1.2 | 0.2 | 1.0 | 1.2 | 0.2 | 1.0 | 0.1 | 1.0 |

| At2g04160 | F3L12.2 | 14025_s_at | Subtilisin-like protease, AIR3 | 1.3 | 0.4 | 1.0 | 0.8 | 1.4 | 1.3 | 0.3 | 1.0 | 0.7 | 1.3 |

| At1g72610 | F28P22.20 | 14726_s_at | Germin-like protein | 1.0 | 0.3 | 1.1 | 0.4 | 1.1 | 1.0 | 0.1 | 1.1 | 0.1 | 1.0 |

| At2g05540 | T20G20.11 | 15910_at | Putative glycine-rich protein | 0.8 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 0.4 | 1.3 | 1.1 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.4 | 2.3 |

| At2g38530 | T6A23.27 | 16432_g_at (D2T2)a | Putative nonspecific lipid-transfer protein | 1.0 | 0.6 | 1.0 | 0.2 | 1.3 | 1.0 | 0.1 | 1.2 | 0.1 | 1.0 |

| At1g70370 | F17O7.9 | 16598_s_at | Polygalacturonase isoenzyme1 β-subunit homolog |

1.0 | 0.6 | 1.3 | 0.4 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.4 | 1.2 | 0.3 | 1.4 |

| At2g21140 | F26H11.10 | 17386_at | Putative proline-rich protein | 1.0 | 0.7 | 1.1 | 0.4 | 1.2 | 1.0 | 0.2 | 1.0 | 0.1 | 1.2 |

| At5g18280 | MRG7.24 | 17589_at | Apyrase, membrane-associated protein | 0.9 | 0.2 | 1.8 | 1.0 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 0.2 | 1.0 | 0.6 | 1.2 |

| At1g62510 | T3P18.7 | 18560_at | Similar to 14K-D proline-rich protein | 1.3 | 0.7 | 1.0 | 0.2 | 1.2 | 1.4 | 0.3 | 1.0 | 0.1 | 1.3 |

| At4g12550 | T1P17.140 | 19118_s_at (D2T2)a | Cell wall membrane disconnected CLCT, AIR1A |

1.0 | 0.5 | 1.6 | 0.4 | 2.1 | 1.6 | 0.2 | 1.3 | 0.1 | 1.0 |

| At2g15050 | T15J14.9 | 19548_at | Putative lipid transfer protein | 1.2 | 0.5 | 1.4 | 0.4 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.1 | 1.2 | 0.2 | 1.4 |

| At3g13790 | MMM17.26 | 20239_g_at | β-Fructofuranosidase1 | 1.7 | 0.3 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.3 | 2.4 | 0.3 | 1.2 | 0.9 | 1.0 |

| Membrane related | |||||||||||||

| At2g28630 | T8O18.8 | 12577_at | Putative fatty acid elongase | 1.0 | 0.5 | 1.6 | 0.3 | 1.5 | 1.8 | 0.6 | 1.0 | 0.2 | 2.8 |

| At1g68530 | T26J14.10 | 15642_at | Very-long-chain fatty acid condensing enzyme CUT1 |

1.1 | 0.5 | 1.1 | 0.3 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.3 | 1.0 | 0.2 | 1.1 |

| At4g23400 | F16G20.100 | 17931_at | PiP1-5 | 1.0 | 0.3 | 1.1 | 0.6 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 0.4 | 1.0 | 0.1 | 1.4 |

| Unclassified | |||||||||||||

| At4g21960 | T8O5.170 | 12752_s_at | Peroxidase prxr1 or p42 | 1.1 | 0.5 | 1.0 | 0.2 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 0.1 | 1.2 | 0.0 | 1.0 |

| At1g04030 | F21M11.3 | 13587_at | Similar to acid phosphatase | 1.2 | 0.6 | 1.1 | 0.2 | 1.0 | 1.2 | 0.2 | 1.2 | 0.0 | 1.0 |

| At3g32980 | T15D2.9 | 15969_s_at | Peroxidase prxr3 or p32 | 1.0 | 0.3 | 1.1 | 0.3 | 1.3 | 1.5 | 0.1 | 1.3 | 0.0 | 1.0 |

| At4g26690 | T15N24.4 | 17897_at | Putative kinase | 1.0 | 0.3 | 1.2 | 0.9 | 1.1 | 1.0 | 0.3 | 1.1 | 0.5 | 1.0 |

| Unknown | |||||||||||||

| At2g25510 | F13B15.17 | 16047_at | Unknown protein | 1.3 | 0.4 | 1.0 | 0.3 | 1.4 | 1.6 | 0.7 | 1.1 | 0.2 | 1.0 |

| At1g70160 | F20P5.12 | 18652_at | Unknown protein | 1.0 | 0.3 | 1.1 | 0.4 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 0.2 | 1.0 | 0.4 | 1.2 |

| Stress related | |||||||||||||

| At1g54000 | F15I1.8 | 12777_i_at | Myrosinase-associated protein | 1.2 | 0.3 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 1.4 | 1.8 | 0.1 | 1.2 | 0.1 | 1.0 |

| At5g25610 | T14C9.150 | 15776_at | Dehydration-induced protein RD22 | 1.3 | 0.7 | 1.4 | 0.2 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 0.2 | 1.0 | 0.1 | 1.3 |

| At1g54010 | F15I1.9 | 16493_at | Myrosinase-associated protein | 1.0 | 0.7 | 1.2 | 0.4 | 1.4 | 1.2 | 0.1 | 1.0 | 0.2 | 1.0 |

| Secretory nonrelated | |||||||||||||

| At1g09750 | F21M12.13 | 14018_at | DNA binding protein | 1.0 | 0.5 | 1.0 | 0.3 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.1 | 1.6 | 0.1 | 1.3 |

| At4g37470 | F6G17.120 | 14080_at | Putative β-ketoadipate enol-lactone hydrolase |

1.0 | 1.0 | 1.2 | 0.3 | 0.8 | 1.7 | 0.8 | 1.2 | 0.1 | 1.0 |

| At4g00400 | F5I10.4 | 14469_at | Acyltransferase domain | 1.0 | 0.7 | 2.1 | 0.2 | 1.6 | 1.1 | 0.0 | 1.1 | 0.1 | 1.0 |

Repressed genes meeting the 1000-5P-0.4 criteria are boldface and those meeting the 1000-3P-0.5 criteria are italicized boldface.

Numbers of replicas on the Affymetrix GeneChip for this gene meeting the restrictions in tunicamycin (T) and DTT (D) are shown in parentheses.

The overall results suggest that in Arabidopsis, the UPR upregulates and downregulates at least 0.7 and 1.8% of the genome, respectively.

Sequence Analysis of the Promoters of UPR Target Genes

Detailed sequence analyses were performed to identify common cis-acting regulatory elements in the UPR target genes. The promoters of the target genes of the UPR in yeast and mammalian cells are characterized by specific response elements: yeast UPRE, CAGCGTG; mammalian UPRE, TGACGTGG/A; mammalian ERSE-I, CCAAT-N9-CCACG; and mammalian ERSE-II, ATTGG-N-CCACG. We used two approaches to find response elements in the promoter of the Arabidopsis regulated genes. (1) We searched 1-kb upstream sequences from the known or predicted translation start codons for all of the genes identified in this study as being upregulated (53 genes) or downregulated (129 genes) during the UPR, using either the MEME or the Motif Sampler program. (2) Using the UPR motifs identified in other eukaryotes (see above), we searched for these motifs in the same promoter sets of the Arabidopsis UPR regulated genes. The results of these searches are presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Consensus Putative UPR cis-Acting Elements for Upregulated Genes

| CC-N12-CCACG Element

|

CCACGTCA Element

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AGI Gene | Description | Stranda | Positionb | Motif | Strand | Position | Motif |

| At1g09180 | Putative SAR1B | + | 877 | CCAgTccccattacCCACG | |||

| At5g08970 | ATAF2 | + | 685 | CCAATaatattacgCCACG | |||

| At2g02810 | UDP-galactose transporter, AtUtr1 | + | 920 | CCAgTgattagcttCCACG | |||

| At4g34630 | Unknown protein | − | 880 | CCAgTtatatgttgCCACG | |||

| At4g16660 | HSP-like protein | − | 891 | CCAATgaaaatattCCACG | + | 929 | tttattCCACGTCAgtgt |

| At4g24190 | HSP90 isolog | + | 820 | CCAATacaaaactaCCACG | + | 795 | gtcgctCCACGTCAagaa |

| At2g41490 | GPT | − | 928 | CCAATaaggatttgCCACG | − | 914 | gatttgCCACGTCgcttc |

| At4g19880 | Putative GST | − | 350 | CCtgaagacgagatCCACG | |||

| At1g27350 | Protein with SBP domain | + | 854 | CCAATtatagacggCCACG | |||

| At5g61790 | Calnexin, CNX1 | − | 887 | CCAATcataacaggCCACG | − | 873 | aacaggCCACGTCAttca |

| At4g11800 | Unknown protein | − | 549 | CCAcTgtacaacacCCACG | |||

| At2g47470 | Putative PDI | + | 884 | CgAtTgatatcacgCCACG | + | 898 | atcacgCCACGTCAttgt |

| At4g14430 | Carnitine racemase-like protein | + | 127 | CCgAattagacaacCCACG | |||

| At1g07670 | ER-type Ca2+-transporting ATPase4 | + | 218 | CCAATgatgtgtcaCCACG | + | 271 | catgtgCCACGTCAcgtg |

| At1g08650 | Putative Ca2+-dependent protein kinase | − | 154 | CCttatccattgggCCACG | |||

| At4g10040 | Cytochrome c | + | 892 | CCAcTatttagacgCCACG | |||

| At1g09080 | BiP-like protein | − | 784 | aagcagaCACGTgAcatt | |||

| At4g34630 | Unknown protein | − | 878 | atgttgCCACGTaAggat | |||

| At1g09210 | Calreticulin-2 | − | 918 | ctgcagCCACGTaAtcca | |||

| At2g45070 | sec61 β-subunit homolog | − | 913 | aaaatgCCACcTCAgcgt | |||

| At5g42020 | BiP | + | 813 | attggtCCACGTCAtctc | |||

| At4g24920 | Protein sec61 γ-subunit-like | − | 820 | gttgtgCCAtGTCAgcaa | |||

| At4g01810 | Putative protein transport factor | + | 829 | ttaataCCACGTCAtgca | |||

| At1g11890 | Similar to vesicle trafficking | + | 841 | aacgagCCACGTCAtcaa | |||

| At1g67360 | Stress-related protein, putative | − | 885 | acttgtCCACGTaAtcca | |||

| At4g02880 | Unknown protein | + | 241 | aattatCCACGTCggtct | |||

| At2g44080 | Unknown protein | + | 639 | tccatcCCACGTCAtcat | |||

| At2g47180 | Galactinol synthase | − | 279 | aattaaCCACGTgAaaaa | |||

Conserved nucleotides from each motif are shown in boldface, the two ERSE-II motifs in UPR upregulated genes are underlined, and conserved nucleotides with ERSE-I and mammalian UPRE motifs are shown in uppercase.

+, forward; −, reverse.

Position from the 5′ terminus of the ATG initiation codon.

Using the MEME or the Motif Sampler program, we found no statistically significant motif in the promoters of the downregulated UPR genes. For the 53 upregulated genes, we identified the motif CCACGTCA. The CCACGTCA motif corresponds to the complementary sequence of one of two possible sequences contained in the mammalian UPRE (TGACGTGG/A). The CCACGTCA consensus motif was found at least one time in the promoters of 18 of the 53 upregulated UPR genes. Nine of these 18 genes contain the exact CCACGTCA motif or mammalian UPRE. In the other nine genes, there are slight variations, usually one base. There is no upregulated UPR gene with the alternative mammalian UPRE, TGACGTGA.

Searching for the ERSE-I motif, we identified seven genes (CNX1, HSP-90, HSP-like, SBP-like, GPT, ATAF2, and ER-Ca2+-ATPase4). However, the slightly less conserved CC-N12-CCACG motif was found in 9 of the 53 genes. One-third of all of the genes with the motif CCACGTCA have the CC-N12-CCACG motif. Using the ERSE-II motif, we found only two genes that have this response element: BiP and the calcium-dependent kinase. The yeast UPRE, CAGCGTG, was found only in the promoter of the BiP-like protein and the putative protein At4g02880.

We compared the abundance of these various motifs in the promoters of the UPR upregulated genes with the abundance in the promoters of all of the Arabidopsis predicted genes (25,498) and with all of the genes on the Affymetrix GeneChip (7372). The results are shown in Table 6. This table should be read as follows, using mammalian ERSE-I as an example. There are 202 genes in the Arabidopsis genome with the ERSE-I motif. We expected that 58 would be on the Affymetrix GeneChip based on the total number of unique genes on this chip. However, we found 64 genes, a slight overrepresentation. Of the 64 genes, 2 were downregulated and 7 were upregulated. The expected values are 1.13 and 0.46, respectively. The ratios of the observed to the expected values for upregulation and downregulation are a measure of the enrichment of the ERSE-I motif in the UPR regulated gene sets. We found substantial enrichment of the identified motifs in the UPR upregulated gene pool: ∼4.5-fold for CCACGTCA (mammalian UPRE), 8-fold for CC-N12-CCACG, 15-fold for the ERSE-I, and 13-fold for ERSE-II. The yeast UPRE was enriched only twofold in the UPR upregulated gene set. The most statistically significant putative regulatory motifs are ERSE-I and ERSE-II. However, they are present in the promoters of quite a few genes (64 for ERSE-I and 21 for ERSE-II) on the Affymetrix GeneChip, but only ∼10% of these genes are UPR upregulated.

Table 6.

Conserved UPR cis-Acting Elements in Arabidopsisd

| Abundancea

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name of cis Element |

Sequence of cis Element |

Arabidopsis Genome (24,598) |

8K GeneChip (7,372) |

UPR Downregulated Genes (129) |

UPR Upregulated Genes (53) |

Genes |

| Motif I | CCACGTCA | 862 | 282 (249)b | 5 (4.93)c | 9 (2.03)c | BiP, CNX1, PDI (At2g47470), HSP-90,HSP-like, Ca-ATPase4, At2g44080, similar to vesicle trafficking, At4g01810 |

| Motif II | CC-N12-CCACG | 1010 | 265 (292) | 7 (4.64) | 15 (1.91) | SAR1B, HSP-90, SBP-like, At4g10040, GPT, Ca-ATPase4, CNX1, AtUtr1, PDI (At2g47470), At4g11800, At4g14430, Ca-kinase, HSP-like, At4g34630, GST, ATAF2 |

| Mammalian UPRE | TGACGTGAc (tcacgtca) | 488 | 126 (141) | 0 (2.2) | 0 (0.91) | |

| Yeast UPRE | CAGCGTG | 453 | 118 (131) | 0 (2.07) | 2 (0.85) | BIP-like, At4g02880 |

| Mammalian ERSE-I | CCAAT-N9-CCACG | 202 | 64 (58) | 2 (1.12) | 7 (0.46) | CNX1, HSP-90, HSP-like, SBP-like, Ca-ATPase4, GPT, ATAF2 |

| Mammalian ERSE-II | ATTGG-N-CCACG | 41 | 21 (11.93) | 0 (0.37) | 2 (0.15) | BiP, Ca-kinase |

Occurrence based on the number of predicted sequences in the Arabidopsis genome at the time of this analysis and on independent genes in the 8K Affymetrix GeneChip. Total number of genes is shown in parentheses.

Numbers in parentheses in this column are expected numbers based on total detected in the Arabidopsis genome.

Numbers in this column are corrected based on occurrence in the Affymetrix GeneChip.

Alternative mammalian UPRE. The reverse sequence is shown in parentheses.

DISCUSSION

We analyzed mRNA abundance changes resulting from the UPR in Arabidopsis with Affymetrix GeneChips and then searched the promoters of the regulated genes for the presence of cis-acting elements relevant to the UPR. To ensure the reliability of our expression analysis, we included the following important features. (1) Independent treatments with two different well-known ER stress inducers, tunicamycin and DTT, and at two different incubation times were performed to avoid the inclusion of genes regulated by the chemical agent and not related to the UPR. Only genes that were upregulated or downregulated in both treatments were considered to be involved in the UPR. (2) Controls for each time point were included in the microarray analysis, which is equivalent to having additional replicas for each control treatment, because the pair-wise Pearson correlations of the expression intensities of the six control points were high (Table 1). (3) Confirmation of the upregulation of gene expression found in the microarray analysis of four previously described upregulated genes in the Arabidopsis UPR (Figure 2) (Koizumi et al., 2001) allowed us to search for genes with similar gene expression patterns. (4) High-stringency criteria were used to select the differentially expressed genes. Upregulated genes found by searching for genes with expression patterns that correlated with those of known UPR target genes were essentially the same when high-stringency criteria were applied to the whole microarray, showing that both strategies were equivalent and redundant (Figure 3). (5) RNA gel blot analysis for two of the new Arabidopsis upregulated UPR genes identified in this study verified our microarray data (Figure 4).

GeneChip data generally referred to as “expression analysis” data concern levels of mRNA and are not necessarily a measure of gene transcription activity. Changes in mRNA levels can be attributable to changes in the rate of transcription and/or other post-transcriptional processes, especially mRNA stability. Changes in mRNA abundance were determined from the GeneChip data and by quantifying the RNA gel blots. We analyzed the data for three different genes (BiP, sec61 γ-subunit, and a gene with Affymetrix code 16311_at) using two treatments (tunicamycin and DTT) and found that the two methods were in good agreement in five of six cases. The exception was tunicamycin induction for the 16311_at gene, for which the fold increase was four times greater on the GeneChip than on the RNA gel blot. The reason for this discrepancy is not known.

From the 8256 Arabidopsis probe sets present on the 8K Affymetrix GeneChip, approximately one-third of the genes were expressed in young plants (an average difference of >1000 and 5 P in absolute call flags) in either the tunicamycin or the DTT treatment experiments (Figure 3A). Of the 7372 independent Arabidopsis genes in the microarray, 0.7% are UPR upregulated. Because one-third of the Arabidopsis genome is represented on the Affymetrix GeneChip, we extrapolated a figure of at least 172 genes that may be regulated by the UPR in Arabidopsis. In mammalian cells, 1% of the genes are thought to be induced as UPR targets (Okada et al., 2002), whereas in yeast, ∼6% are upregulated in the UPR (Travers et al., 2000). Okada et al. (2002) have suggested that because yeast lacks the PERK pathway, which attenuates protein synthesis, yeast needs a higher percentage of genes that are induced by the UPR. A PERK homolog has not been found in Arabidopsis; therefore, the percentage of UPR genes upregulated may be lower than that in mammals.

DTT Regulates More Genes Than Tunicamycin

DTT apparently regulates three or four times more genes than does tunicamycin (Figure 3A). This result may be explained by the respective action mechanisms of these chemicals. Tunicamycin prevents glycosylation of newly synthesized proteins in the ER, but DTT is a potent antioxidant that affects new as well as completed and functional proteins by disrupting disulfide bonds that function as structural elements in the tertiary and quaternary structures of proteins. DTT also causes oxidative stress and the expression of defense genes (Herouart et al., 1993). Among the DTT upregulated genes found in this study, there are kinases, transcription factors, ring finger proteins, stress proteins, glutathione S-transferases, glucanases, heat shock proteins, cytochrome P450s, phosphatases, GTP binding proteins, vesicle trafficking, and stress proteins as well as proteins involved in sugar and amino acid metabolism, in degradation, and in the ethylene pathway. Some of these genes also were found to be upregulated by tunicamycin treatment, but induction by tunicamycin did not reach the twofold change threshold. The presumed functions of the proteins encoded by DTT upregulated genes are in agreement with the known effects of DTT on living cells (see above). Furthermore, our results indicate that DTT upregulates a larger number of genes related to ERAD and to amino acid biosynthesis than does tunicamycin. The ERAD pathway and oxidative stress have been related to UPR in yeast (Travers et al., 2000; Sagt et al., 2002), whereas amino acid synthesis signaling appears to be related to the UPR in mammals (Harding et al., 2000).

UPR Encompasses Chaperones, PDI, Glycan Synthesis Enzymes, and ERAD Proteins

Using the 1000-2P-2 stringency criteria, the UPR of Arabidopsis was found to comprise 53 upregulated genes. As expected, BiP is among the upregulated genes (Denecke et al., 1991; Fontes et al., 1991; Koizumi et al., 2001). The high sequence identity of the two BiP genes (Koizumi, 1996) does not permit them to be differentiated. The use of BiP promoter–GUS fusions shows that both genes are induced by tunicamycin (data not shown). An additional BiP-like gene with 75% amino acid identity also is induced as part of the UPR. The derived amino acid sequence of this gene has no H/KDEL tail, but there is a HDEL sequence in another open reading frame of this gene, indicating a possible sequencing mistake. This finding raises the possibility that Arabidopsis has three BiP genes.

As expected from previous results, many chaperone genes, including PDI, calreticulin, and calnexin, are upregulated (Koizumi et al., 2001). Of the 17 Arabidopsis genes in the group, 8 are on the Affymetrix GeneChip, and 5 of these 8 are identified here as part of the UPR (calreticulin2, CNX1, a calnexin homolog, and the two PDIs At2g47470 and At2g39920). The UPR also regulates genes that encode proteins involved in polypeptide translocation through the proteinaceous pore (sec61 family, protein transport factor, and signal peptidase) and genes that encode enzymes needed for the synthesis of Asn-linked glycans or their modification in the ER or the Golgi (one of the two Arabidopsis GPT genes, a glucosyltransferase, and the Gal transporter AtUtr1).

Unfolded proteins present in the ER are disposed of after retrotranslocation from the lumen of the ER to the cytosol, where they are broken down by proteasomes (Ward et al., 1995; DiCola et al., 2001), a process known as ERAD. In yeast, the UPR comprises chaperone genes and ERAD genes (Travers et al., 2000). In mammalian cells, the situation is more complex. ERAD genes appear not to be regulated by the UPR (Okada et al., 2002), although a connection between ERAD and UPR has been described (de Virgilio et al., 1999). In Arabidopsis, the UPR includes two ERAD genes (a putative ubiquitin and an AAA-type ATPase).

UPR of Arabidopsis Includes Many Vesicle Trafficking Proteins

Our analysis identified a number of proteins that are part of the vesicle trafficking machinery. For example, OS-9 is a cytosolic ER membrane–associated protein involved in ER-to-Golgi transport (Litovchick et al., 2002); it also is upregulated in tunicamycin-treated mammalian cells (Okada et al., 2002). In the 1000-2P-2 UPR upregulated gene set, we identified a UPR upregulated gene (At5g35080) that shares similarities with mammalian OS-9. Other genes related to vesicle trafficking identified as being upregulated include a Golgi-associated membrane protein, a coatomer α-subunit, a vesicle-trafficking protein, a homolog of the mouse stromal cell–derived factor 2, and SAR1B. The SAR1B gene encodes a protein belonging to a family of five GTP binding proteins, the Sar1 family. The Sar1 GTPase is an essential component of COPII vesicle coats involved in the export of cargo from the ER (Takeuchi et al., 2000; Phillipson et al., 2001). The ER-Ca2+-ATPase4 also was found to be induced. It may be the functional homolog of the mammalian SERCA2, which is part of the mammalian UPR.

Interesting Genes That Do Not Meet the Selection Criteria

For the analysis described in this study, we used different restrictive criteria to identify upregulated and downregulated genes. A priori, there is no good reason to choose one set of criteria over another. In setting these criteria, we may have eliminated some genes that are part of the UPR. Therefore, we examined the expression patterns of some genes that are known to be upregulated during the UPR in other systems (yeast and mammals) and that are present on the Affymetrix GeneChip but that did not meet the 1000-2P-2 induction criteria for both tunicamycin and DTT treatments (data not shown). The following genes known from other systems had a fold induction of >1.4 (but <2.0) in both tunicamycin and DTT treatments and could be part of the Arabidopsis UPR: the β-subunit of the 20S proteasome PBB2, the ATPase subunit of the 26S proteasome RPT2a, the COP9/signalosome subunit FUS4, three E2-ubiquitin–conjugating enzymes (UBC11, UBC14, and a putative E2), two F-box proteins (AtFBL5 and a putative one), the α-subunit of sec61, a ubiquitin-dependent proteolytic protein, a ubiquitin-like protein, a putative synaptobrevin, two clathrin-related proteins, three coatomer proteins, and a sec1 family protein. These genes all fall into the same functional categories as the genes that do meet the criteria (secretory system, ERAD, and vesicle transport), indicating the difficulty in choosing these criteria. It is likely that multiple reiterations of this experiment would establish whether these genes are part of the UPR. We were not able to identify any upregulated putative transcription factors that may be responsible for triggering the UPR. This is consistent with the situation in mammals (Okada et al., 2002).

What about Lipid Biosynthesis?

The yeast UPR includes many lipid biosynthesis genes. In plants, the floury2 (fl2) mutant of maize resembles a UPR situation because the presence of a zein polypeptide with an uncleaved signal peptide causes the upregulation of chaperone genes and the formation of aberrant protein bodies. A number of lipid biosynthetic activities are increased in the endosperm of fl2 (Shank et al., 2001). No lipid biosynthetic genes were identified in the high-stringency UPR set (Tables 2 and 3), but the gene for diacylglycerol kinase was induced 1.7-fold. In fl2 maize endosperm, the activity of this enzyme is increased twofold. We did not identify any genes that encode other lipid biosynthetic enzymes, such as choline-phosphate cytidylyltransferase, phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase, and phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate 5-kinase, that have been shown to have higher activities in the fl2 mutant.

UPR Downregulates mRNA Levels of Many Genes

We also identified a set of UPR genes with lower mRNA levels: 31 genes using the more stringent 1000-5P-0.4 criteria and 129 genes using the 1000-3P-0.5 criteria. A priori, we do not know whether these lower levels indicate less transcriptional activity or a decrease in mRNA stability. Downregulation of genes as part of the UPR has not been studied in yeast. In mammalian cells, there is some information based on expression analysis of large numbers of genes. In one study (Okada et al., 2002), cytoplasmic chaperones were found to be downregulated as part of the UPR. If the UPR in Arabidopsis attenuates the translation of specific mRNAs and if such attenuation decreases mRNA stability, then the lower levels of mRNA observed here could be the result of such processes rather than the result of a decrease in transcriptional activity. Inhibition of translation elongation generally promotes mRNA stability (Wilusz et al., 2001), whereas inhibition of translation initiation could downregulate mRNA abundance (Kawaguchi and Bailey-Serres, 2002).

The most striking common feature of these proteins with lower mRNA levels is that all but a few have signal peptides or are membrane proteins (29 of 31 and 107 of 129 for criteria 1000-5P-0.4 and 1000-3P-0.5, respectively). Assuming that there are 2600 active unique genes on the 8K GeneChip and that 17% of them encode proteins with signal peptides (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/TargetP/predictions/pred.html), the 129 mRNAs represent ∼29% of the active genes with signal peptides.

In these experiments, the UPR was imposed on young, actively growing plants, and this fact is reflected in the identities of the downregulated genes. Many are related to cell elongation and division: cell wall proteins, proteins involved in cell wall loosening, aquaporins necessary for water influx, and enzymes for the synthesis of membrane components. The largest single group of UPR downregulated genes encodes proteins related to the cell wall (25%). The rest of the 129 genes are mainly peroxidases, four aquaporins, and other sugar-, stress-, and lipid-related proteins. One of the lipid-related genes downregulated during the UPR encodes hydroxy-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase. This gene encodes an ER-located enzyme involved in sterol biosynthesis. The gene dwarf1, another sterol biosynthetic enzyme, is downregulated in the Arabidopsis UPR. Hydroxy-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase and dwarf1 participate in the synthesis of brassinosteroid, a hormone involved in growth and development (Mussig et al., 2002).

Does the Downregulation of Genes That Encode Secretory Proteins Result in Significantly Lower Protein Input in the ER?

Research in the 1980s showed that when eukaryotic cells are incubated with radioactive amino acids in the presence of tunicamycin, the drug inhibits the accumulation of radioactive extracellular proteins without inhibiting protein synthesis per se (Hori and Elbein, 1981). This finding was interpreted as an inhibition by tunicamycin of glycoprotein biosynthesis and/or secretion. We can now reinterpret those data as showing that the nonglycosylated and malfolded polypeptides most likely were retrotransported out of the ER and degraded by proteasomes, although there may have been an inhibition of synthesis as well. Our work on the effect of tunicamycin on the synthesis of secreted invertase by suspension-cultured carrot cells showed that invertase was synthesized in the presence of the drug, because unglycosylated protein was present in ER-derived vesicles. Little radioactive invertase accumulated in the cell wall, indicating that invertase was broken down either just before or just after secretion (Faye and Chrispeels, 1989).

Labeling of the microsomal fraction was addressed by Driouich et al. (1989), who used a brief (1-h) tunicamycin treatment of cultured sycamore cells followed by Met incorporation. They found no inhibition of Met incorporation into the microsomes. However, the calculation presented above suggests that we should not expect an inhibition of >15 to 20% of incorporation into the microsomes caused by the decrease of mRNA abundance of downregulated genes. Furthermore, this decrease maybe be offset by an increased synthesis of chaperones and other ER residents.

To what extent would an inhibition of the accumulation of a radioactively labeled protein in the ER be caused by the degradation of malfolded polypeptides or by a decreased input into the ER because the mRNA population has declined? Answering this difficult question would require the availability of antibodies for specific reasonably abundant secretory proteins whose mRNAs are downregulated as part of the UPR. One would have to examine the relative abundance and the translation of mRNAs for these proteins in the population of membrane-bound polysomes. Immunoselection of radioactive polypeptides combined with polysome runoff experiments might be able to distinguish the two aspects of the UPR: downregulation of protein synthesis and degradation of malfolded proteins.

UPR cis-Acting Elements in UPR-Inducible Genes

A number of cis-acting elements have been identified as being important in the regulation of the UPR in yeast and mammals (yeast and mammalian UPRE and mammalian ERSE-I and ERSE-II) (Mori et al., 1996; Roy and Lee, 1999; Kokame et al., 2001; Okada et al., 2002). All of them were described initially in the promoters of genes that encode chaperone proteins and were found later in other UPR target genes. We found that the four UPR cis elements mentioned above are present in the promoters of some of the upregulated Arabidopsis UPR genes, but only the mammalian ERSE-I and ERSE-II are highly enriched (∼15- and 13-fold) in this gene set. The fact that we have not found a unique cis-acting element suggests that in Arabidopsis the UPR has evolved into a more complex phenomenon compared with the yeast UPR, in which a single response element suffices. It is likely that different subsets of induced Arabidopsis UPR genes are regulated by different transcription factors, as is the case in mammals. Because plants and mammals are cellularized organisms, they may need to fine-tune their genetic controls. The results also show conservation of response elements for the regulation of the UPR between plants and mammals. A similar conclusion has been drawn by Oh et al. (2003) in their functional analysis of the UPR response elements of Arabidopsis BiP.

A second type of cis element related to the UPR (AARE) has been proposed as being responsible in mammals for the induction of the expression of genes that encode proteins related to amino acid synthesis during the UPR through the PERK-ATF4 pathway (Okada et al., 2002). We did not find this cis element in the Arabidopsis UPR gene sets described here. However, we also did not identify any genes that encode enzymes of amino acid metabolism in which the AARE has been found.

On the basis of this analysis, we suggest that the mammalian UPRE, ERSE-I, and ERSE-II motifs are good candidates to be involved in the regulation of some of the Arabidopsis genes upregulated during the UPR. All three mammalian UPR cis-acting elements share a CCACG core, which means that a given promoter element may be designated in different ways, depending on the bases flanking this core. If all of the cis-acting elements turn out to be important for the Arabidopsis UPR, then overlapped elements could be used to ensure a stronger response. Indeed, of all of the genes on the Affymetrix GeneChip with ERSE-I and ERSE-II motifs in their promoters (∼85 genes), 90% are not induced during the UPR. Therefore, it is likely that such motifs are necessary but not sufficient or may be repressed by other factors. This conclusion, tentative as it is, validates the genomic approach. We performed some preliminary work on the BiP promoters with BiP promoter–GUS fusions, assuming that BiP would be representative of the UPR (Koizumi et al., 1999). The analysis presented here shows that the BiP promoter is almost unique rather than representative of other genes.

In summary, the use of microarrays has revealed gene sets that are regulated during the Arabidopsis UPR. The nature of the genes in the set of 53 upregulated genes is consistent with that revealed in studies of the UPR in yeast and mammals. Furthermore, we have identified a set of 129 downregulated UPR genes, most of which have signal peptides. The Arabidopsis upregulated gene set is more similar to that identified as upregulated in yeast UPR, but the putative cis-acting elements found in the promoters of these Arabidopsis UPR upregulated genes are enriched in mammalian UPR motifs rather than in yeast UPR motifs. Additional work should help to reveal how this intracellular stress signal is transduced in Arabidopsis.

METHODS

Plant Material and Treatments

Lots of 60 sterile seeds of Arabidopsis thaliana (ecotype Columbia) were germinated in 13 mL of liquid Murashige and Skoog (1962) medium containing 1% Suc (w/v) and cultured further in a 16-h-light/ 8-h-dark cycle with gentle shaking for 6 days.

RNA Preparation and RNA Gel Blot Analysis

Six-day-old plantlets were treated with endoplasmic reticulum stress reagent (tunicamycin or DTT) or solvent (DMSO) for 0, 2, or 5 h. Each experiment included five conditions: 0 h plus stress reagent (0), 2 and 5 h without stress reagent (2 and 5), and 2 and 5 h with stress reagent (2+ and 5+). Control conditions for each experiment were the initial condition at 0 h and controls at 2 and 5 h. In the case of the tunicamycin experiment, plantlets from control conditions 2 and 5 were treated with the same volume of DMSO used for treated conditions 2+ and 5+. Tunicamycin or DTT was added to the liquid medium at a final concentration of 5 μg/mL or 10 mM, respectively. Tunicamycin stock was prepared in DMSO. Total RNA was prepared from each condition according to the RNeasy Plant Kit protocol (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Ten micrograms of total RNA was fractionated on agarose-formaldehyde gels and transferred by capillary action overnight to Hybond-N membranes (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ) using 20 × SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl and 0.015 M sodium citrate). The RNA was fixed by baking at 80°C for 30 min. Prehybridization was performed at 42°C for 2 h in a solution containing 5 × SSC, 5 × Denhardt's solution (1× Denhardt's solution is 0.02% Ficoll, 0.02% polyvinylpyrrolidone, and 0.02% BSA), 50% formamide (v/v), 1% SDS (w/v), and 100 μg/mL denatured salmon sperm DNA with rotation. 32P-labeled cDNAs of Binding Protein2 (Koizumi, 1996) and of the genes that encode sec61 γ-subunit–like and secretory pathway–related proteins (identified as T26D3.10, F13M23.60, and T16L4.30, respectively) were added to the solution, and hybridization was performed overnight, followed by one washing with 2 × SSC and 0.1% SDS (w/v) at room temperature and three washings with 0.2 × SSC and 0.1% SDS (w/v) at 68°C for 10 min. Detection of labeled probe was performed by phosphorimaging.

Microarray Analysis

RNA samples were processed to cDNA, labeled, and hybridized to Affymetrix GeneChips (Affymetrix, Inc., Santa Clara, CA), and the fluorescence was scanned at the GeneChip Core facility (University of California San Diego). The Affymetrix Microarray Suite program was used to normalize microarray data to negative controls and also to arbitrarily set the algorithm absolute call flag, which indicates the reliability of the data points according to P (present), M (marginal), and A (absent). The data were analyzed further using the GeneSpring version 4.1 program (Silicon Genetics, San Carlos, CA) to normalize each gene to itself by taking the median of all five conditions for each of the tunicamycin and DTT treatments. The fold change in mRNA abundance was based on the average difference (expression intensities) of all of the probe sets for each condition in the two treatments (tunicamycin and DTT). The GeneSpring program filter gene tool was used to determine the list of genes that met the restriction criteria. The Venn diagram tool was used to determine the overlap in the gene sets. To determine the reproducibility of the microarray analysis, we calculated the Pearson correlation factors using pair-wise comparisons of the average differences in mRNA abundance in the six control conditions.

The expression profiles of the Arabidopsis protein disulfide isomerase (At1g21750), calreticulin2 (At1g09210), calnexin1 (At5g61790), and binding protein (At5g42020 and At5g28540) genes were chosen as positive controls for tunicamycin and DTT experiments, because these four genes are present on the Affymetrix GeneChip and are well-known UPR targets. Entries with expression patterns similar to those of any of these four positive control genes and showing a Pearson correlation coefficient of at least P = 0.95 were selected. To these entries, we applied further restrictive criteria: (1) average expression level of ≥1000 in at least one of the five conditions for each treatment; (2) five of five absolute call flags should be P; and (3) a fold variation of ≥2.5 in at least one of the five conditions for each experiment in the case of upregulated genes (1000-5P-2.5). The same restrictions also were applied directly to all 8297 probe sets from the Affymetrix GeneChip to search for upregulated genes with different expression patterns than the positive controls. Manual inspection was necessary to remove anomalous data such as repeated loci or probe sets that met the restriction conditions but that were not upregulated. A fold variation of ≤0.4 in at least one of the five conditions for each experiment was the third restrictive criterion for the downregulated genes (1000-5P-0.4). Less restrictive criteria were applied as follows: for the upregulated genes, two of five absolute call flags of P and a fold increase of ≥2 in at least one of the five conditions for each experiment (1000-2P-2); for the downregulated genes, three of five absolute call flags of P and a fold decrease of ≤0.5 in at least one of the five conditions for each experiment (1000-3P-0.5). Manual inspection was performed for each selected entry group to remove repeated entries and entries that met the criteria but that were not upregulated or downregulated. Supplemental data can be found at http://www-biology.ucsd.edu/others/chrispeels/LabHomePage.html.

Analysis of the Frequency of UPR Elements That Occur within Promoter Regions

The AGI code name for each upregulated or downregulated gene that met the higher restriction criteria was used to retrieve the first 1000 pb of sequence upstream of the ATG codon using the bulk downloading tool available at http://www.arabidopsis.org. Upregulated and downregulated genes in FASTA format were analyzed further using either the MEME (Bailey and Elkan, 1994) or the Motif Sampler (Thijs et al., 2002) program to search for cis-acting elements. MEME and Motif Sampler are available at http://meme.sdsc.edu and http://www.esat.kuleuven.ac.be/~dna/bioI/Software.html, respectively. The Pattern Matching program available at http://www.arabidopsis.org was used to screen the first 1000 pb upstream for each of the 27,458 coding sequences present in the Arabidopsis genome database for the presence of mammalian and yeast UPREs (TGACGTGG/A and CAGCGTG, respectively), ERSE-I (CCAAT-N9-CCACG), ERSE-II (ATTGG-N-CCACG), and the two Arabidopsis motifs found in the study.

Upon request, all novel materials described in this article will be made available in a timely manner for noncommercial research purposes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Nozomu Koizumi for interesting discussion about the UPR and Julian Schroeder for allowing the use of expression analysis software. This work was supported by Grant DE-FG03-86ER13497 from the Department of Energy Office of Energy Biosciences to M.J.C. and by a fellowship from the Ministry of Science and Technology of Spain to I.M.M.

Article, publication date, and citation information can be found at www.plantcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1105/tpc.007609.

Footnotes

Online version contains Web-only data.

References

- Bailey, T.L., and Elkan, C. (1994). Fitting a mixture model by expectation maximization to discover motifs in biopolymers. In Proceedings of the Second International Conference on Intelligent Systems for Molecular Biology. (Menlo Park, CA: AAAI Press), pp. 28–36. [PubMed]

- D'Amico, L., Valsasina, B., Daminati, M.G., Fabbrini, M.S., Nitti, G., Bollini, R., Ceriotti, A., and Vitale, A. (1992). Bean homologs of the mammalian glucose-regulated proteins: Induction by tunicamycin and interaction with newly synthesized seed storage proteins in the endoplasmic reticulum. Plant J. 2, 443–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denecke, J., Goldman, M.H., Demolder, J., Seurinck, J., and Botterman, J. (1991). The tobacco luminal binding protein is encoded by a multigene family. Plant Cell 3, 1025–1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Virgilio, M., Kitzmuller, C., Schwaiger, E., Klein, M., Kreibich, G., and Ivessa, N.E. (1999). Degradation of a short-lived glycoprotein from the lumen of the endoplasmic reticulum: The role of N-linked glycans and the unfolded protein response. Mol. Biol. Cell 10, 4059–4073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Cola, A., Frigerio, L., Lord, J.M., Ceriotti, A., and Roberts, L.M. (2001). Ricin A chain without its partner B chain is degraded after retrotranslocation from the endoplasmic reticulum to the cytosol in plant cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 14726–14731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driouich, A., Gonnet, P., Makkie, M., Laine, A.-C., and Faye, L. (1989). The role of high-mannose and complex asparagine-linked glycans in the secretion and stability of glycoproteins. Planta 180, 96–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faye, L., and Chrispeels, M. (1989). Apparent inhibition of β-fructosidase secretion by tunicamycin may be explained by breakdown of the unglycosylated protein during secretion. Plant Physiol. 89, 845–851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez, J., Yaman, I., Merrick, W.C., Koromilas, A., Wek, R.C., Sood, R., Hensold, J., and Hatzoglou, M. (2002). Regulation of internal ribosome entry site-mediated translation by eukaryotic initiation factor-2α phosphorylation and translation of a small upstream open reading frame. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 2050–2058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontes, E.B.P., Shank, B.B., Wrobel, R.L., Moose, S.P., O'Brian, G.R., Wurtzel, E.T., and Boston, R.S. (1991). Characterization of an immunoglobulin binding protein homolog in the maize floury-2 endosperm mutant. Plant Cell 3, 483–496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding, H.P., Novoa, I., Zhang, Y., Zeng, H., Wek, R., Schapira, M., and Ron, D. (2000). Regulated translation initiation controls stress-induced gene expression in mammalian cells. Mol. Cell 6, 1099–1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herouart, D., Van Montagu, M., and Inzé, D. (1993). Redox-activated expression of the cytosolic copper/zinc superoxide dismutase gene in Nicotiana. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90, 3108–3112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hori, H., and Elbein, A. (1981). Tunicamycin inhibits protein glycosylation in suspension cultured soybean cells. Plant Physiol. 67, 882–886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawaguchi, R., and Bailey-Serres, J. (2002). Regulation of translation initiation in plants. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 5, 460–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]