Abstract

Proteins in the cytoplasmic dynein pathway accumulate at the microtubule plus end, giving the appearance of comets when observed in live cells. The targeting mechanism for NUDF (LIS1/Pac1) of Aspergillus nidulans, a key component of the dynein pathway, has not been clear. Previous studies have demonstrated physical interactions of NUDF/LIS1/Pac1 with both NUDE/NUDEL/Ndl1 and CLIP-170/Bik1. Here, we have identified the A. nidulans CLIP-170 homologue, CLIPA. The clipA deletion did not cause an obvious nuclear distribution phenotype but affected cytoplasmic microtubules in an unexpected manner. Although more microtubules failed to undergo long-range growth toward the hyphal tip at 32°C, those that reached the hyphal tip were less likely to undergo catastrophe. Thus, in addition to acting as a growth-promoting factor, CLIPA also promotes microtubule dynamics. In the absence of CLIPA, green fluorescent protein-labeled cytoplasmic dynein heavy chain, p150Glued dynactin, and NUDF were all seen as plus-end comets at 32°C. However, under the same conditions, deletion of both clipA and nudE almost completely abolished NUDF comets, although nudE deletion itself did not cause a dramatic change in NUDF localization. Based on these results, we suggest that CLIPA and NUDE both recruit NUDF to the microtubule plus end. The plus-end localization of CLIPA itself seems to be regulated by different mechanisms under different physiological conditions. Although the KipA kinesin (Kip2/Tea2 homologue) did not affect plus-end localization of CLIPA at 32°C, it was required for enhancing plus-end accumulation of CLIPA at an elevated temperature (42°C).

INTRODUCTION

The plus ends of microtubules are highly dynamic in vivo with alternate periods of growth and shrinkage due to polymerization and depolymerization of the tubulin subunits (Desai and Mitchison, 1997). Fascinatingly, an expanding class of proteins termed “plus-end-tracking proteins” or “+TIPs,” which includes the cytoplasmic linker protein (CLIP)-170 protein, EB1, dynactin, and cytoplasmic dynein, all show accumulation at the growing plus end (reviewed by Carvalho et al., 2003; Akhmanova and Hoogenraad, 2005; Galjart, 2005). The targeting mechanisms and cellular functions of these +TIPs are of general interest to the cell biology field.

In the filamentous fungus Aspergillus nidulans, green fluorescent protein (GFP)-labeled cytoplasmic dynein and its regulators, including dynactin (reviewed by Schroer, 2004); NUDF, a homologue of LIS1 (reviewed by Morris et al., 1998; Gupta et al., 2002); and NUDE (Efimov and Morris, 2000), all accumulate at the microtubule plus end in live cells (Xiang et al., 2000; Han et al., 2001; Zhang et al., 2002, 2003; Efimov, 2003). We have previously shown that the plus-end accumulation of cytoplasmic dynein and dynactin is significantly decreased in the deletion/disruption mutant of KINA, the conventional kinesin (Kinesin-1) in A. nidulans (Requena et al., 2001; Zhang et al., 2003). However, the plus-end accumulation of NUDF (LIS1 homologue) is still obvious in the kinA mutant. These results suggest that although KINA is largely responsible for enhancing the plus-end accumulation of dynein and dynactin, other mechanisms are involved in plus-end accumulation of NUDF. Previous results in A. nidulans have shown that NUDF physically interacts with NUDE (Efimov and Morris, 2000). In addition, studies in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and mammalian cells have indicated physical interactions between LIS1/Pac1 (NUDF homologues) and CLIP-170/Bik1 (Coquelle et al., 2002; Sheeman et al., 2003; Lansbergen et al., 2004). Therefore, we sought to identify the A. nidulans CLIP-170 homologue and to determine its role and the role of NUDE in localization of NUDF to the microtubule plus end.

The mammalian CLIP-170 protein is the first discovered +TIP (Perez et al., 1999). The N terminus of CLIP-170 contains two CAP-Gly motifs that are implicated in binding microtubules. It is likely that the plus-end-specific localization in vivo is achieved by copolymerization with tubulins followed by release of the proteins from the older segments due to the lower affinity of CLIP-170 to the microtubule wall (Diamantopoulos et al., 1999; Folker et al., 2005). Homologues of CLIP-170 in both the budding and fission yeasts-(Bik1 in S. cerevisiae and Tip1 in Schizosaccharomyces pombe) are also +TIPs. In both yeast species, the Kip2/Tea2 kinesins (Kinesin-7 family members) physically associate and comigrate with Bik1/Tip1 along the microtubule toward the plus end to enhance their plus-end accumulation (Busch et al., 2004; Carvalho et al., 2004).

CLIP-170 may have several functions at the microtubule plus end, including regulating microtubule dynamics, facilitating microtubule capture at special cortical sites, and localized actin assembly, which are important for cell polarization (Berlin et al., 1990; Brunner and Nurse, 2000; Fukata et al., 2002; Komarova et al., 2002; Arnal et al., 2004; Martin et al., 2005). CLIP-170 has also been implicated in the function of cytoplasmic dynein, a minus-end-directed microtubule motor protein involved in many cellular activities, including transport of organelles/vesicles and proteins, spindle assembly, spindle orientation/nuclear migration, and microtubule-organizing center (MTOC)-reorientation during cell migration or polarization (reviewed by Karki and Holzbaur, 1999; Vallee et al., 2004). The C terminus of CLIP-170 interacts with the N-terminal domains of both CLIP-170 and dynactin that contain the CAP-Gly motifs (Lansbergen et al., 2004), and with LIS1 (Coquelle et al., 2002; Lansbergen et al., 2004). In S. cerevisiae, the CLIP-170 homologue Bik1 functions in the dynein genetic pathway and physically interacts with the LIS1 homologue Pac1, and a C-terminal deletion of Bik1 that has little or no effect on microtubule length significantly decreases the plus-end accumulation of dynein (Sheeman et al., 2003). In mammalian cells, CLIP-170 knock-down by RNA interference (RNAi) decreases plus-end accumulation of dynactin (Lansbergen et al., 2004). Thus, CLIP-170 and its homologues are implicated in targeting dynactin or dynein to the plus ends, where they are required for cargo loading/transport and for microtubule-cortical interactions (Vaughan et al., 2002; Lee et al., 2003; Sheeman et al., 2003; reviewed by Dujardin and Vallee, 2002; Pearson and Bloom, 2004; Vaughan, 2005).

In this study, we have identified the A. nidulans CLIP-170 homologue, CLIPA, and investigated its function and localization. Deletion of CLIPA affected microtubule dynamics in an unexpected manner. Although a higher percentage of microtubules failed to grow all the way to the hyphal tip, those that reached the hyphal tip were less likely to undergo catastrophe. At 32°C, GFP-labeled dynein, dynactin, and NUDF were all seen as comets in the clipA deletion mutant as in wild-type cells. However, in the ΔclipA/ΔnudE double deletion mutant, plus-end comets of GFP-NUDF almost completely disappeared. We suggest that both CLIPA and NUDE target NUDF/LIS1 to the microtubule plus end, thereby facilitating function of NUDF/LIS1 in the dynein pathway. The plus-end localization of CLIPA itself seems to be regulated by different mechanisms under different physiological conditions. Although the KipA kinesin (Kip2/Tea2 homologue) (Konzack et al., 2005) did not apparently affect plus-end localization of CLIPA at 32°C, it was obviously required for enhancing plus-end accumulation of CLIPA at an elevated temperature (42°C). Together, our results have revealed new details of a CLIP-170 family member in a filamentous fungus, further intensifying the biological diversity of this family of proteins regarding their functions and targeting mechanisms.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A. nidulans strains are listed in Table 1. Media, growth conditions, transformations, DNA isolation, Southern blotting, and Western blotting were as described previously (Xiang et al., 1995a,b; Zhang et al., 2002; Efimov, 2003). Multicopy plasmids, including pAid::nudF, pAid::nudF6, pAid::nudC, pAid::apsA, pAid::nudE, pAid::nudE-N, pAid::nudE-C, pAid::GFP::nudE, pAid::GFP::nudE-N, and pAid::GFP::nudE-C have been described previously (Efimov, 2003). The Web site http://www.broad.mit.edu/annotation/fungi/aspergillus/ can be used for identifying hypothetical A. nidulans proteins that share significant homology with a known protein or a domain such as the CAP-Gly microtubule-binding domain. The sequence of each hypothetical protein can be found using the gene search tool (under “Find genes by a variety of method”) by typing in its name, for example, AN1475.2. The Coils server (http://www.ch.embnet.org/software/COILS_form.html) can be used to predict coiled-coil segments using a 28-residue window.

Table 1.

A. nidulans strains

| Strain | Genotype | Source |

|---|---|---|

| R153 | pyroA4; wA3 | C. F. Roberts |

| GR5 | pyrG89; pyroA4; wA3 | G. S. May |

| XX60 | ΔnudA::pyrG; pyrG89 | Xiang et al. (1995a) |

| ΔF54 | ΔnudF::pyr4; pyrG89; pyroA4; wA3 | Willins et al. (1995) |

| SF2-9 | ΔnudE::argB; pyrG89; argB2; pabaA1; fwA1 | Efimov and Morris (2000) |

| SF2-9-9 | ΔnudE::argB; pyrG89 | Efimov (2003) |

| GFP-nudA | alcA(p)::GFP::nudA::pyr4; pyrG89; pyroA4; wA3 | Xiang et al. (2000) |

| GFP-nudF | alcA(p)::GFP::nudF::pyr4; pyrG89; pyroA4; wA3 | Han et al. (2001) |

| GFP-tubA | alcA(p)::GFP::tubA::pyr4; pyrG89; pyroA4; wA3 | Han et al. (2001) |

| GFP-nudF/ΔnudE (XX87RE) | alcA(p)::GFP::nudF::pyr4; ΔnudE::argB; pyrG89; argB2 | Efimov (2003) |

| GFP-nudA/ΔnudE (XX80RE) | alcA(p)::GFP::nudA::pyr4; ΔnudE::argB; pyrG89; argB2; (fwA1) | Efimov (2003) |

| SSK44 | ΔkipA::pyr4, pabaA1, wA3, ΔargB::trpCΔB | Konzack et al. (2005) |

| ΔclipA | ΔclipA::pyroA; pyrG89; wA3 | This work |

| GFP-clipA | alcA(p)::GFP::clipA::pyr4; pyroA4; pyrG89; wA3 | This work |

| GFP-clipA-ectopic | Ectopic integration of pMCB17apx-bikA in GR5 background | This work |

| ΔclipA/ΔnudE | ΔclipA::pyroA; ΔnudE::argB; pyrG89; (argB2) | This work |

| GFP-nudF/ΔclipA | ΔclipA::pyroA; alcA(p)::GFP::nudF::pyr4; pyrG89; wA3; (pyroA4) | This work |

| GFP-nudA/ΔclipA | ΔclipA::pyroA; alcA(p)::GFP::nudA::pyr4; pyrG89; wA3; (pyroA4) | This work |

| GFP-tubA/ΔclipA | ΔclipA::pyroA; alcA(p)::GFP::tubA::pyr4; pyrG89; wA3; (pyroA4) | This work |

| GFP-nudF/ΔclipA/ΔnudE | ΔclipA::pyroA; ΔnudE::argB; alcA(p)::GFP::nudF::pyr4; pyrG89; (pyroA4); (argB2) | This work |

| GFP-nudA/ΔclipA/ΔnudE | ΔclipA::pyroA; ΔnudE::argB; alcA(p)::GFP::nudA::pyr4; pyrG89; (pyroA4); (argB2) | This work |

| GFP-clipA/ΔnudA | alcA(p)::GFP::clipA::pyr4; ΔnudA::pyrG; pyrG89; (wA3) | This work |

| GFP-clipA/ΔnudF | alcA(p)::GFP::clipA::pyr4; ΔnudF::pyr4; pyrG89; (wA3) | This work |

| GFP-clipA/ΔkipA | alcA(p)::GFP::clipA::pyr4; ΔkipA::pyr4; (pyroA4); (pyrG89); wA3 | This work |

| GFP-clipA/ΔkinA | alcA(p)::GFP::clipA::pyr4; ΔkinA::pyr4; (pyroA4); (pyrG89); wA3 | This work |

| GFP-nudE | alcA(p)::GFP::nudE::pyroA; pyrG89; pyroA4; wA3 [pyroA gene is from A. fumigatus] | This work |

| GFP-nudE/ΔnudA | alcA(p)::GFP::nudE::pyroA; ΔnudA::pyrG; pyrG89; (pyroA4); (wA3) | This work |

| GFP-nudE/ΔnudF | alcA(p)::GFP::nudE::pyroA; ΔnudF::pyr4; pyrG89; pyroA4; wA3 | This work |

| GFP-clipA/R21 diploid | alcA(p)::GFP::clipA::pyr4/+; pyroA4/+; pyrG89/+; wA3/+; pabaA1/+; yA1/+ | This work |

All strains carry the veA1 marker. Unconfirmed nutritional and/or color markers are indicated in parentheses.

Fluorescence microscopy of live A. nidulans hyphae was as described (Efimov, 2003; Zhang et al., 2003; Li et al., 2005b). Images were captured using an Olympus IX70 inverted fluorescence microscope (with a 100× objective) linked to a cooled charge-coupled device camera. IPLab software (BioVision, Mountain View, CA) was used for image acquisition and analysis. Two conditions were used in our experiments. Under the first condition, hyphae for microscopy were grown and observed on pads of minimal medium with 100 mM threonine, 4 mM glucose, and 1% agarose at 32°C after 1 d of incubation. Time-lapse series were obtained by taking a 0.6-s exposure every 2 s. Videos were produced with the help of ImageJ (Rasband, ImageJ, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD; http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/, 1997-2005). The second condition was as described in Zhang et al. (2003) and Li et al. (2005b). Cells were incubated at 32 or 42°C in ΔTC3 culture dishes (Bioptechs, Butler, PA) overnight before observation at 32 or 42°C or at room temperature. A Biotechs heating stage and heating objective system were used. Time-lapse series were obtained by taking a 0.1-s exposure every 1 s. Videos were produced using IPLab software. Liquid minimal medium containing glycerol and supplements was used. Under these conditions, the alcA promoter that controls the expression of the GFP-fusions is derepressed but not overexpressed. Microtubule growing and shrinking rates, and the speed of comet movement, were measured using the kymograph generating and measurement function of IPLab (version 3.7). Fluorescence intensity of comets was measured using the Min/Max custom software written by BioVision. Means and standard deviations were calculated using the statistics function under KaleidaGraph version 3.0, and t tests were performed using Sigma Plot version 4.16 (SPSS, Chicago, IL).

ΔclipA Strain

The entire clipA coding sequence of A. nidulans (2007 bp; GenBank XM_405612, hypothetical protein AN1475.2), from the start codon to the stop codon, was replaced with the pyroA gene of A. nidulans as follows. The 1539-base pair sequence upstream of the clipA start codon was amplified by PCR using A. nidulans genomic DNA and primers bikA-8F (TGGACTTGTCTTGGACGAGGTACACG) and bikA-8R (CTCTGTAGAGATCGTTAAAAATCGG). The 1537-base pair sequence downstream of the clipA stop codon was amplified by PCR with primers bikA-9F (GAACAATAGCCTATGATGGCCCCG) and bikA-9R (CACGAGGCGATAGACAAAGTTCTTG). The 2683-base pair fragment with the pyroA gene was produced by PCR with primers pyroA-1F (GATTTTTAACGATCTCTACAGAG CTGCAGAAGTGCGCGAAAGCG) and pyroA-1R (GGGGCCATCATAGGCTATTGTTC AAGCTT GATCCAGGAGTATACGGGTTTTTGGC), which have tags (underlined) matching sequences upstream of the clipA start and stop codons. The three fragments were combined and amplified by PCR with outside primers bikA-8F and bikA-9R. The resulting 5759-base pair fusion fragment was used to transform the GR5 strain to pyroA prototrophy. The double homologous recombination event that replaces the clipA gene with the pyroA fragment was confirmed by PCRs and Southern blotting for six transformants. For PCR verification of the ΔclipA locus, the following two sets of primers were used: bikA-10F (GATCTTCTTGAGTGCGAATAACTCGG)/pyroA-3R (TCCGGTCTCCTTACGCTTTCGCGCAC) and pyroA-3F (AATGCCAAAAACCCGTATACTCCTGGATC)/bikA-10R (AATCTGCGAGATGTGGATTGTGCGGC). Both pairs amplified only the clipA deletion locus but not the wild-type locus or the deletion construct. All six deletion strains had identical colony morphologies.

GFP-clipA Strain (GFP-tagged clipA under Control of the alcA Promoter)

To facilitate making N-terminal GFP fusions, the terminating codon of the GFP2-5 gene in plasmid pMCB17 (Fernandez-Abalos et al., 1998) and the subsequent sequence up to the BamHI site were replaced with the sequence GGCGCGCCGGCTTAATTAA containing AscI and PacI recognition sites. The XbaI insert in the resulting plasmid (pMCB17ap) was removed to produce plasmid pMCB17apx. The first 1507 bp of the clipA gene were amplified from the genome by PCR using primers TTTGGCGCGCCCGGGATGGCGCCTCTGGACGAAATAC and GGGTTAATTAAGTCTCCTGGGACCACCGTGCGG (A. nidulans sequence is underlined). The PCR product was cut with AscI and PacI and cloned at the AscI/PacI sites of pMCB17apx to give p17apx-clipA. The GR5 strain was transformed with supercoiled p17apx-clipA. A single homologous integration of p17apx-clipA at the clipA locus was confirmed by PCRs and Southern blotting for six independent pyr4+ transformants. All six strains had identical growth phenotypes and GFP signal distribution. These strains express the GFP2-5 protein sequence followed by a Gly-Ala-Pro-Gly sequence and a complete CLIPA protein sequence. Several wild-type-like transformants with an ectopic integration of a single copy of p17apx-clipA were obtained and GFP signals in these transformants were identified as well. Western blotting with anti-GFP antibodies confirmed expression of GFP fusions of the correct size.

In the GFP-clipA strain we used in this study, the GFP-CLIPA fusion was made at the N terminus of CLIPA just like the mammalian GFP-CLIP-170 fusion (Perez et al., 1999). The full-length fusion gene was under the control of the regulatable promoter alcA, which can be shut off by glucose but can be induced to express a downstream gene at a moderate level using glycerol as a carbon source. Although the full-length GFP-CLIPA is under the control of the alcA promoter, a C-terminal-truncated clipA gene (truncated before the sequence encoding the first zinc finger motif) under its endogenous promoter is still present. When point inoculated on a glycerol plate, the GFP-clipA strain has colony diameter similar to that of a wild-type strain. In addition, the average speed of GFP-CLIPA comet movement was similar to the speed of microtubule growth in a wild-type background (at 32 or 42°C), suggesting that the GFP fusion was functional during hyphal growth and did not interfere with gross microtubule behavior in living cells.

GFP-nudE Strain (GFP-tagged nudE under the Control of the alcA Promoter)

The nudE gene was tagged with GFP using plasmid pPyroAfg, which is similar to pMCB17apx (see above) except that it carries the Aspergillus fumigatus pyroA gene instead of the Neurospora crassa pyr4 selective maker. The 2369-base pair sequence of the A. fumigatus genome homologous to the A. nidulans pyroA locus was amplified with primers GGTTGGTACATATGATCCTTGTTGAATAAAATGAGTGTTCG and TGTTAGTACATATGGTGATACTACTCGCCGCGTCTTCAAG (A. fumigatus sequence is underlined). The PCR product was cut with NdeI and cloned at the NdeI site of pNEB193 (New England Biolabs, Beverly, MA). In the resulting plasmid, pPyroAf1, the pyroA gene is oriented away from the multiple cloning site. To make pPyroAfg, the SmaI/XbaI vector portion of pPyroAf1 was ligated to the EcoRI(filled)/XbaI fragment from pMCB17apx that contains the alcA promoter and GFP2-5. The first 1509-bp of the nudE gene were amplified by PCR from genomic DNA using primers TTTGGCGCGCCCGGCATGCCTTCCGCCGATGAGCCTTCTTC and GGGTTAATTAATCAGTGGTAGGATTGGTGGAATAATGG (A. nidulans sequence is underlined). The PCR product was cut with AscI and PacI and cloned into the AscI/PacI sites of pPyroAfg to give pGFP-nudE. The GR5 strain was transformed with supercoiled pGFP-nudE. A single homologous integration of pGFP-nudE at the nudE locus was confirmed by PCRs and Southern blotting for five independent pyroA+ transformants. All five strains had identical growth phenotypes and GFP signal distribution. These strains express the GFP2-5 protein sequence followed by a Gly-Ala-Pro-Gly sequence and a complete NUDE protein sequence.

Introducing GFP-Fusions into Different Mutant Backgrounds

To examine NUDE localization in the absence of clipA, the ΔclipA/ΔnudE strain was transformed with autonomously replicating plasmids carrying GFP-nudE or its deletion versions (plasmids pAid::GFP::nudE, pAid::GFP::nudE-N, and pAid::GFP::nudE-C). In all other cases, genetic crosses with an appropriate GFP strain were used to introduce the GFP-fusion into various mutants. Specific progeny were selected as follows. To obtain GFP-clipA in the ΔnudA or ΔnudF mutant background, progeny that exhibited a typical nuclear distribution (nud)-mutant colony phenotype and GFP-CLIPA comets under a microscope were isolated. For introducing GFP-clipA into the kipA deletion/disruption back-ground, progeny were selected by observing the GFP-CLIPA comets under a microscope and PCR analyses of the kipA locus. Two primers, kipAN: AACGCTCGAGTCTACGACTC and kipAC:GTTCCGGTCATACCATAAGC, were used to amplify genomic DNA. Using the genomic DNA with the kipA deletion/disruption, a 1.9-kb fragment was amplified, whereas a much smaller fragment of ∼100 base pairs was amplified from a wild-type kipA locus. To introduce GFP-clipA into the ΔkinA background, progeny were selected by observing the GFP-CLIPA comets under a microscope and the growth phenotype of the ΔkinA mutant, which was then confirmed by Southern analysis of the ΔkinA locus as described in Requena et al. (2001). To introduce the GFP-nudA, GFP-nudF, GFP-nudM, and GFP-tubA fusions into the ΔclipA background, progeny were verified by microscopic observation of the GFP fusions and by PCR analysis of the clipA deletion locus (see above).

RESULTS

Identification of the A. nidulans Homologue of CLIP-170

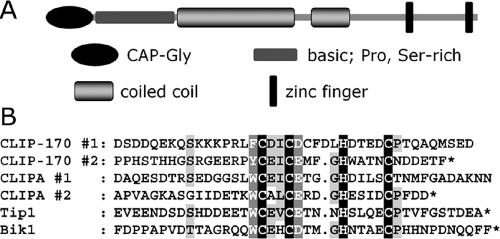

We identified the CLIP-170 homologue of A. nidulans by searching its genome for open reading frames with a CAP-Gly domain, which is sufficiently long and conserved from yeast to human to permit identification by a Blast search. The annotated A. nidulans genome (Galagan et al., 2005) can be searched at http://www.broad.mit.edu/annotation/fungi/aspergillus/. A query sequence containing amino acids 60-125 (corresponding to the first of the two CAP-Gly domains) of the human CLIP-170 protein (accession no. A43336) produces four significant alignments (scored better than 1.0e-03): AN6323.2, AN5116.2, AN5531.2 and AN1475.2. Each of these four proteins contains a single CAP-Gly domain. AN6323.2 is NUDM (p150Glued dynactin) characterized by us previously (Zhang et al., 2003). AN5116.2 only has 272 amino acids with an Alp11_N domain (found in tubulin folding cofactor B) at its N terminus and a CAP-Gly domain at its C terminus. AN5531.2 contains a CAP-Gly domain at its N terminus followed by leucine-rich repeats (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST). Only AN1475.2 has a modular organization typical of CLIP-170 homologues in other organisms, which all contain one or two N-terminal CAP-Gly domains followed by long coiled-coil segments and one or two Zn-finger motifs at the C termini (Figure 1A). We refer to the corresponding gene (GenBank XM_405612) as clipA and its product as CLIPA (hypothetical protein AN1475.2). Similar to Bik1 and Tip1 in yeasts, CLIPA has one CAP-Gly domain at the N terminus, whereas human CLIP-170 has two. The human CLIP-170 is significantly longer (1392 aa) than fungal proteins (CLIPA is 668 aa, Bik1 is 440 aa, and Tip1 is 461 aa) mainly due to a longer linker coiled-coil domain. CLIPA is slightly bigger than the yeast proteins because of a longer C-terminal region. As in CLIP-170, there are two zinc finger motifs at the end of CLIPA, whereas yeast proteins have one. Judging by the spacing of Cys and His residues, both zinc finger motifs are homologous to each other, to yeast zinc finger motifs, and to the second zinc finger of CLIP-170 (Figure 1B). Notably, the second zinc finger of CLIP-170 was found to be essential for interaction with LIS1 (Coquelle et al., 2002).

Figure 1.

(A) Modular organization of the A. nidulans homologue of CLIP-170, CLIPA. Domains are drawn approximately to scale. (B) Alignment of zinc finger motifs from several CLIP-170 homologues. The regions shown are (top to bottom) human CLIP-170 (accession no. A43336) residues 1317-1356 (first zinc finger) and 1357-1392 (second zinc finger), A. nidulans CLIPA (AN1475.2) residues 537-578 (first zinc finger) and 635-668 (second zinc finger), S. pombe Tip1 (CAB16742) residues 422-461, and S. cerevisiae Bik1 (NP_009901) residues 400-440.

CLIPA Promotes Microtubule Growth and Also Regulates Microtubule Dynamics

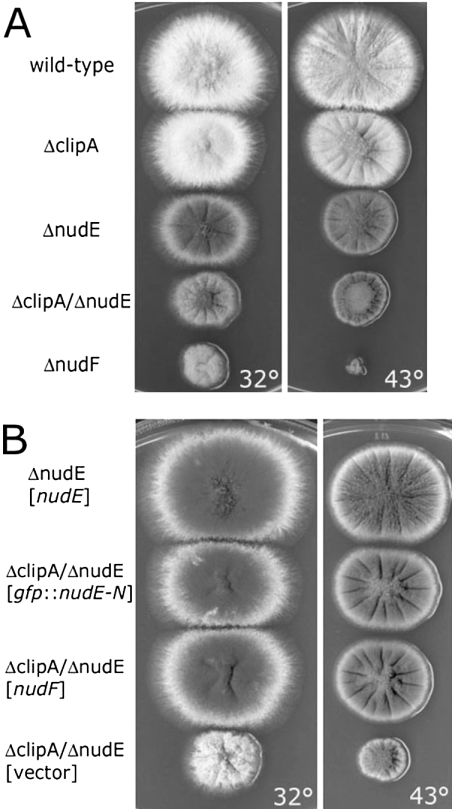

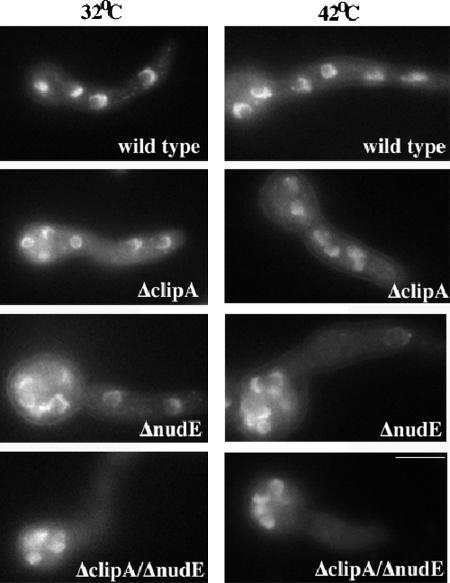

The ΔclipA strain, which lacks the entire clipA open reading frame, displayed wild-type colony morphology with only a small reduction of growth rate, and such reduction was a little more obvious when cells were grown at an elevated temperature of 43°C (Figure 2). Nuclear distribution was not severely defective (Figure 3). This is in contrast to the nudA (cytoplasmic dynein heavy chain) or nudF (the LIS1/Pac1 homologue) deletion mutants, which, when grown under these conditions, exhibited a severe nuclear distribution defect and a small-colony phenotype typical of nuclear distribution mutants (Xiang et al., 1995b; Willins et al., 1995).

Figure 2.

(A) Colonies of the ΔclipA deletion mutant, wild type, ΔnudE, ΔnudF, and ΔclipA/ΔnudE double deletion mutant. (B) The ΔclipA/ΔnudE double deletion is suppressed by multiple copies of nudF and the N-terminal domain of nudE. The strains were transformed with the multicopy plasmid pAid carrying a gene indicated in square brackets. ΔnudE strain transformed with pAid::nudE (top) serves as a wild-type control. Strains were grown at indicated temperature on YAG + UU plates for 3 d.

Figure 3.

4,6-Diamidino-2-phenylindole staining of wild-type and mutant cells. The cells were grown on YG + UU medium at indicated temperature for 8 h. Bar, 5 μm.

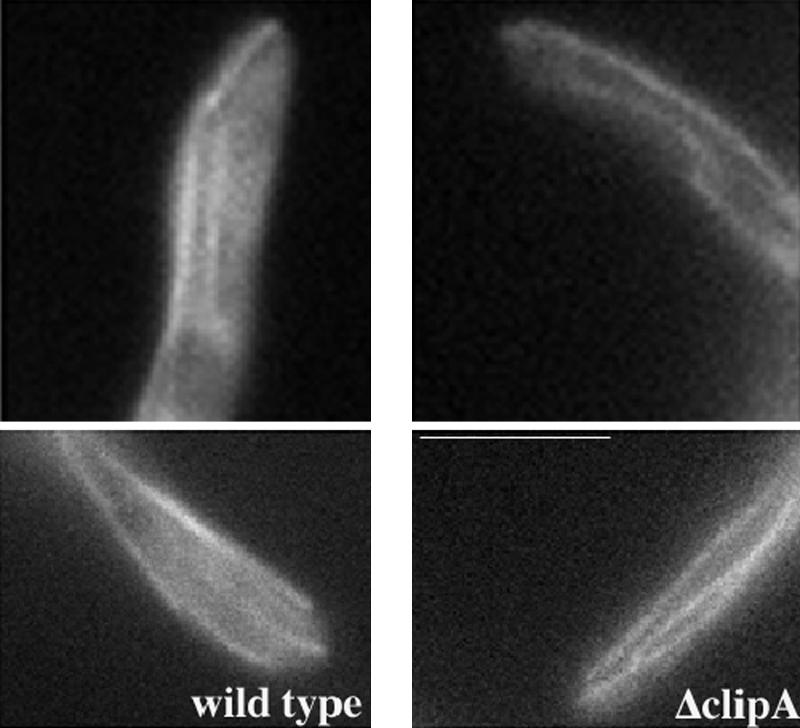

To determine whether microtubule behaviors are affected by deletion of CLIPA, we introduced the GFP-tubA fusion into the ΔclipA background. Microtubules were clearly seen to extend to the hyphal tip in the ΔclipA strain (Figure 4 and Supplemental Movies 1 and 2), which was somewhat unexpected because in both yeasts, deletions of CLIP-170 homologues result in notably shorter cytoplasmic microtubules (Berlin et al., 1990; Brunner and Nurse, 2000). To reveal more subtle alterations in the microtubule network, we compared cytoplasmic microtubule dynamics in wild-type cells with that in ΔclipA cells at 32°C. In wild-type cells, the majority of cytoplasmic microtubules grew to the hyphal tip and paused shortly before undergoing catastrophe (Table 2; Han et al., 2001). Long-range shrinkage was often observed, and rescue frequency was lower than catastrophe frequency (Table 2). In time-lapse series we took in this study, we did not find any microtubule that paused at the hyphal tip for longer than 33 s (the total time period of one time-lapse sequence) before undergoing catastrophe (n = 57). However, in the ΔclipA strain, ∼16% of microtubule ends that reached the hyphal tip region remained at about the same position for longer than 33 s without undergoing long-range shrinkage (n = 70). Within this group, some ends might undergo short-range shrinkage and growth, which was hard to distinguish from pausing ends that might move around slightly. In addition to this phenotype, more microtubules in the mutant were observed to shrink before reaching the hyphal tip (Table 2), which is consistent with the role of CLIP-170/Bik1/Tip1 in promoting microtubule growth (Berlin et al., 1990; Brunner and Nurse, 2000; Carvalho et al., 2004). Some of the short microtubules in the mutant switched frequently between short-range growth and shrinkage; thus, the total rescue frequency in the mutant as measured was even higher than that of wild-type cells. Because of the opposite effects on microtubules that failed to reach the hyphal tip and those that had reached the hyphal tip, on average there was no dramatic change in the total frequency of catastrophe. Growth rate and shrinkage rate also were not significantly altered (Table 2). Together, our results suggested that CLIPA may promote long-range microtubule growth and shrinkage, and it may also promote dynamicity near the hyphal tip. In the course of this study, we also noticed that although the wild-type GFP-tubA hyphae were relatively long and straight, the GFP-tubA/ΔclipA hyphae were shorter and more curled, suggesting that CLIPA plays a subtle role in directional growth of the hyphae.

Figure 4.

Cytoplasmic microtubules are able to extend to the hyphal tip in the ΔclipA mutant. Cells were grown in minimal glycerol medium for overnight at 32°C. Bar, 5 μm.

Table 2.

Microtubule dynamics in wild type and in ΔclipA mutant at 32°C

| Wild type | ΔclipA | |

|---|---|---|

| Growth rate (μm / min) | 9.10 ± 2.13 (n = 29) | 8.67 ± 2.52 (n = 28) |

| Shrinkage rate (μm / min) | 40.10 ± 18.74 (n = 21) | 41.85 ± 23.54 (n = 23) |

| Frequency of catastrophe (s–1) | 0.028 (n = 40; 1320 s) | 0.024 (n = 45; 1485 s) |

| Frequency of rescue (s–1) | 0.0045 (n = 40; 1320 s) | 0.0094 (n = 45; 1485 s) |

| Microtubules that shrink before reaching the hyphal tip | 10% (n = 40) | 40% (n = 45) |

| Microtubules that pause more than 33 s at the hyphal tip before shrinking | 0% (n = 57) | 16% (n = 70) |

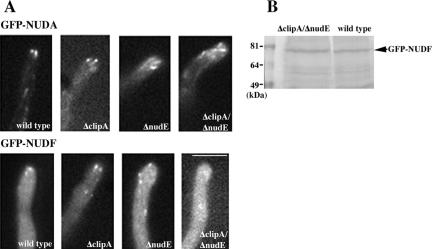

The Microtubule Plus-End Accumulation of NUDF Almost Completely Disappeared in the ΔclipA/ΔnudE Double Deletion Mutant

Consistent with a very mild phenotype of the clipA deletion mutant, despite the alteration in microtubule dynamics, we did not detect any dramatic changes in the localization of GFP-tagged NUDF (LIS1/Pac1), NUDA (dynein heavy chain), NUDM (p150Glued dynactin), NUDE, and NUDE C-terminal domains in the ΔclipA deletion strain at 32°C (Supplemental Movies 3, 4, 5, and 6 and Figure 5; our unpublished data). However, a reduction of GFP-NUDF comet intensity was noted when the cells were grown at an elevated temperature of 42°C (our unpublished data), suggesting that CLIPA plays a role in NUDF localization. We hypothesized that NUDF could be targeted by both CLIPA and NUDE because they both have a NUDF binding domain on one end and a microtubule (MT)-targeting domain on another. To test this idea, we constructed a ΔclipA/ΔnudE double deletion mutant and introduced GFP-tagged nudF and nudA genes into it. The ΔclipA/ΔnudE double mutant was viable, but more inhibited than either of the single mutants (Figure 2). Although neither single deletion mutation had an obvious effect on plus-end targeting of NUDF at 32°C, there was almost a complete disappearance of NUDF comets in the ΔclipA/ΔnudE double mutant (Figure 5A). This was not due to a dramatic change of microtubule structures in the double mutant, because GFP-NUDA comets were obvious in the double mutant grown under the same condition (Figure 5A). To rule out the possibility that the GFP-NUDF protein was degraded in the double mutant, we performed a Western analysis with total protein extracts, and there was no significant reduction in the level of GFP-NUDF in this double mutant (Figure 5B). Together, these results suggest that CLIP170 and NUDE play overlapping roles in plus-end localization of NUDF. Consistent with this notion, the double mutant exhibited a more dramatic nuclear distribution defect than the single mutants (Figure 3).

Figure 5.

(A) GFP-NUDF comets are present in the ΔclipA and ΔnudE single deletion mutants but not in the ΔclipA/ΔnudE double deletion mutant. GFP-NUDA comets are present in the double mutant grown under the same condition. Strains were grown in liquid minimal glycerol medium at 32°C for overnight before observation. Bar, 5 μm. (B) A Western blot showing that the protein level of GFP-NUDF did not change significantly in the double deletion mutant.

Microtubule Plus-End Accumulation of CLIPA Is Independent of the KipA Kinesin at 32°C but Is Significantly Enhanced by It at 42°C

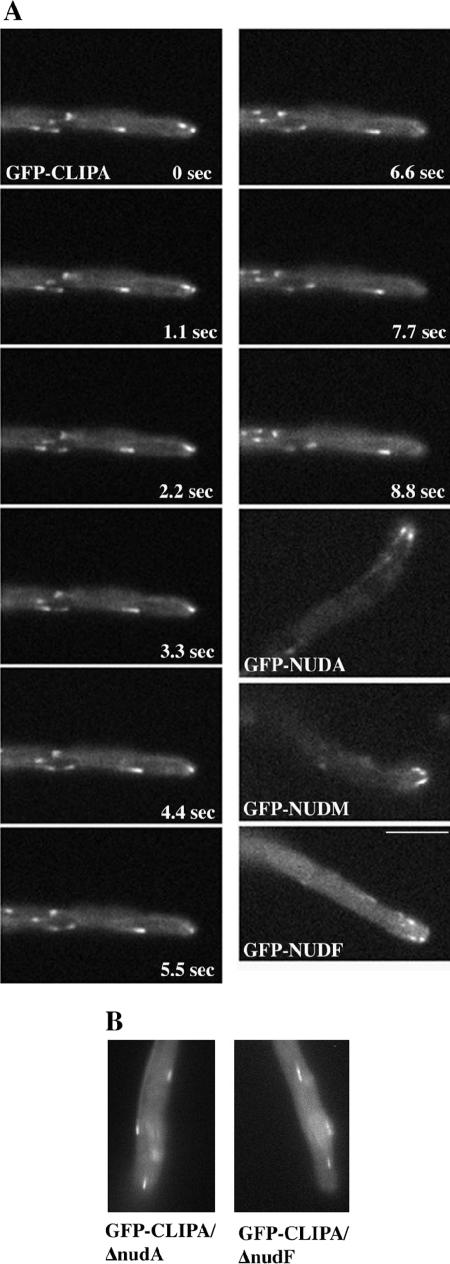

As expected, GFP-tagged full-length CLIPA was observed in linearly moving, cometlike structures corresponding to dynamic MT ends (Figure 6 and Supplemental Movie 7). The same localization was observed in strains expressing GFP-CLIPA fusion truncated just before the first zinc finger motif (strain GFP-clipA-ectopic) (our unpublished data). At 32°C, the intensity of CLIPA comets seemed unchanged throughout the hyphae, including internal hyphal segments. This is different from dynein, dynactin, and NUDF comets that increase in intensity as they approach the hyphal tip (Figure 6). Supplemental Movie 8, prepared identically to Movie 7, shows GFP-NUDF comets for comparison.

Figure 6.

(A) Localization of GFP-CLIPA. GFP-NUDA, GFP-NUDM, and GFP-NUDF localization are shown for comparison. Cells were grown in minimal glycerol medium overnight at 32°C, and images were taken at 32°C. Images were taken every 1 s with 0.1-s exposure. (B) GFP-CLIPA comets in ΔnudA and ΔnudF strains. Bar, 5 μm.

Nuclei often could be identified as dark objects in the GFP-clipA strain due to the exclusion of the cytoplasmic GFP-CLIPA pool from membranous organelles (Supplemental Movie 9, four evenly spaced dark objects). CLIPA comets were frequently observed originating from a spot on such an object, reflecting MT nucleation by the nucleus-associated spindle pole body (Supplemental Movie 9, leftmost nucleus, comets occur from the low point of the nucleus in frames 11 and 25 and move rightward). There was typically an accumulation of CLIPA at septa resulting from CLIPA comets crashing into them from both sides (Supplemental Movie 9). The majority of comets moved toward septa, and movements away from septa were rare. Only two comets moving away from the septum were seen in Movie 9 (between the septum and nucleus to the left).

To determine whether the plus-end localization of CLIPA requires it to associate with NUDF or dynein, we examined GFP-CLIPA localization in the absence of NUDF or dynein. We found that GFP-CLIPA comets were clearly present in the ΔnudA and ΔnudF deletion mutants, and there was no apparent change in the intensity of the comets (Figure 6B), but the behavior of the comets was changed, consistent with a reduced catastrophe frequency of microtubules in dynein mutants (Han et al., 2001). Comets frequently paused before either disappearing or resuming movement. Supplemental Movie 10 contains several such comets in the middle of the hypha.

Previously, observation of nonfluorescent speckles in GFP-CLIP-170 comets in mammalian cells has indicated that CLIP-170 proteins treadmill at the plus end, meaning that they associate with the growing end while dissociating from the microtubule wall (Perez et al., 1999; Folker et al., 2005). To determine whether CLIPA proteins undergo treadmilling at the plus end, we generated a diploid A. nidulans strain that contained both the endogenous CLIPA and the GFP-labeled CLIPA to observe nonfluorescent speckles. When cells were grown and observed at 32 or 42°C, comets were too short for any speckles in the comets to be seen. When the cells were grown at 32°C and observed at room temperature, microtubule growth rate was lower than at higher temperatures, and thus comet movement rate was also lower (our unpublished data). Under this set of conditions, comets seemed longer and nonfluorescent speckles could occasionally be seen near the trailing end of a comet. Figure 7 shows one of the few time-lapse series that we could use for this type of analysis. At the trailing end of the comet, a nonfluorescent speckle was followed by a fluorescent dot. Although the leading end of the comet moved forward, the fluorescent intensity of the trailing dot decreased (Figure 7, arrows), but its position remained unchanged. The nonfluorescent speckle in front of the trailing dot remained at about the same position, which is consistent with a treadmilling mechanism. However, due to the low fluorescence intensity of the trailing dot, we could not exclude the possibility that molecules transported into the nonfluorescent space might not be detected.

Figure 7.

Observation of a nonfluorescent speckle followed by a trailing fluorescent dot (indicated by arrows) at the trailing end of a comet. The same images are shown in the bottom panel with two lines. The top line indicates that the leading end of the comet apparently moved forward. The bottom line shows that the position of the nonfluorescent spot did not change significantly. Images were taken at room temperature (at ∼25°C). Bar, 4 μm.

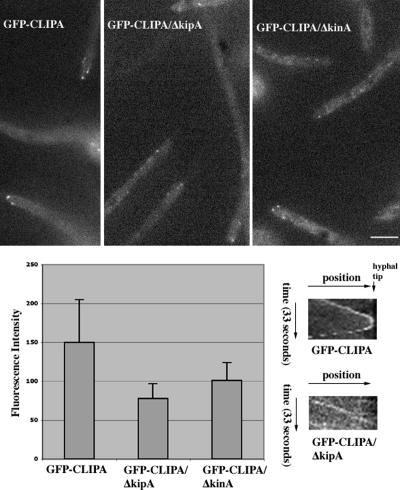

In S. cerevisiae and S. pombe, kinesins Kip2 and Tea2 (Kinesin-7 members), respectively, transport CLIP-170 homologues (Bik1 and Tip1) toward microtubule plus ends to enhance the plus-end localization of Bik1 and Tip1 (Busch et al., 2004; Carvalho et al., 2004). In A. nidulans, the homologue of Kip2/Tea2, KipA, has been characterized (Konzack et al., 2005). Similar to its yeast homologues, it tracks the plus ends of microtubules, and its plus-end localization depends on its own motor activity (Konzack et al., 2005). However, at 32°C, we did not detect any obvious decrease in the fluorescence intensity of the GFP-CLIPA comet in the kipA deletion/disruption mutant (wild type: 267 ± 87 arbitrary units for image intensity, n = 20; ΔkipA: 270 ± 86, n = 20; a t test showed that the means of the samples were not different at the 0.05 level).

In S. cerevisiae, the Bik1 (CLIP-170 homologue) comets exhibit a clear “backtracking” behavior (Carvalho et al., 2004), indicating that Bik1 proteins, as a dynamic population, remain accumulated even at the shrinking ends of microtubules. We have previously observed similar back-tracking behavior of GFP-dynein and NUDF comets in A. nidulans (Xiang et al., 2000; Han et al., 2001), which was more obvious at 42°C but could also be observed at 32°C. In GFP-CLIPA, backtracking was only rarely observed at 32°C. Comets that arrived at the hyphal tip disappeared after a few seconds (Figure 6). Because cytoplasmic microtubules normally undergo catastrophe just a few seconds after they hit the hyphal tip, this result indicates little or no CLIPA accumulation at the plus end after the end started to shrink. However, after we grew the cells at 42°C overnight and observed them at 42°C, we noticed clear backtracking of ∼49% of GFP-CLIPA comets after they arrived at the hyphal tip (n = 47) (see a kymograph in Figure 8 and Supplemental Movie 11).

Figure 8.

GFP-CLIPA localization in wild-type, ΔkipA, and ΔkinA cells at 42°C. Cells were grown in minimal glycerol medium overnight at 42°C, and images were taken at 42°C. Bar, 5 μm. Bottom left, means and standard deviations of fluorescence intensity (arbitrary units) of comets are shown (wild type: n = 18; ΔkipA: n = 31; and ΔkinA: n = 21). Bottom right, kymographs showing the path of a comet in a wild-type cell (note that backtracking is obvious in the bottom half of the kymograph), and that of a comet in the ΔkipA mutant moving toward the hyphal tip. The slopes in the two kymographs are similar, indicating that these two comets moved at about the same rates toward the hyphal tip. The kymograph showing the comet in ΔkipA is less clear due to the lower fluorescence intensity of the comet.

Because backtracking cannot be explained by the mechanism involving copolymerization with tubulins, but it can be better explained by other mechanisms, including a kinesin-mediated transport mechanism (Galjart and Perez, 2003; Wu et al., 2006), we determined CLIPA localization in deletion/disruption mutants of two plus-end-directed kinesins, KipA and KINA, at 42°C. In contrast to the result obtained at 32°C, we found that at 42°C, the fluorescence intensity of GFP-CLIPA comets was obviously lower in the ΔkipA mutant (Supplemental Movie 12 and Figure 8). Because in wild-type background many GFP-CLIPA comets at 42°C seemed brightest when they arrived at the hyphal tip, we only measured fluorescence intensity of the comets that were at the hyphal tip. Our measurements showed on average almost a 50% reduction in CLIPA comet intensity in the ΔkipA mutant, indicating that this kinesin plays an important role in enhancing plus-end accumulation of CLIPA (Figure 8). In the ΔkinA mutant background, there was also a significant reduction of comet intensity (p < 0.05; Figure 8 and Supplemental Movie 13), although this reduction was less striking compared with that in the ΔkipA mutant.

NUDE Targeting Does Not Require NUDF or NUDA

We have previously characterized NUDE localization using GFP-NUDE fusions expressed from extrachromosomally replicating plasmids and under control of the native promoter of nudE (Efimov, 2003). To facilitate genetic crosses, we constructed a strain with the GFP-nudE fusion integrated at the nudE locus under the control of the alcA promoter (GFP-nudE strain). As with the plasmid-expressed GFP-NUDE, there was considerable variability in the GFP signal among different hyphae. Many hyphal tips did not have any detectable GFP signal. Overexpression of the GFP fusion resulted in protein aggregates, particularly in internal hyphal segments (described as “specks” in Efimov, 2003). In actively growing tips that did have the GFP signal, comet structures were observed (Supplemental Movie 14). To determine whether dynein or NUDF affects NUDE localization, we introduced the GFP-NUDE fusion into the ΔnudF and ΔnudA deletion mutants by genetic crosses. Neither of the deletions abolished GFP-NUDE comets or aggregates. Supplemental Movie 15 shows the ΔnudA/GFP-nudE strain. The comets were present in one hypha, whereas another hypha had aggregates, which still displayed fast movements. These results suggest that, most likely, targeting of NUDE to microtubule plus ends requires neither dynein nor NUDF.

The Phenotype of ΔclipA/ΔnudE Double Deletion Mutant Is Suppressed by NUDF Overexpression

Our current study suggests that CLIPA and NUDE play overlapping roles in recruiting NUDF to the microtubule plus end. However, the exact roles of these two proteins in NUDF function may not be identical. Protein overexpression can often reveal complex interactions between genes. Expression of the nudF (Xiang et al., 1995a); nudC (Osmani et al., 1990); apsA, a Num1 homologue in A. nidulans (Fischer and Timberlake, 1995; Veith et al., 2005); and nudE (Efimov and Morris, 2000) genes from multicopy plasmids (Efimov, 2003) had no effect on the growth of the ΔclipA strain. Most notably, its small growth defect at 43°C was not suppressed by overexpression of nudF or nudE. In contrast, the ΔnudE mutant phenotype was completely suppressed by NUDF overexpression (Efimov, 2003). Because CLIPA and NUDE are both involved in NUDF targeting, such suppression could in theory be due to a more efficient NUDF-CLIPA interaction in the ΔnudE background. However, we found that the ΔclipA/ΔnudE double deletion mutant was still suppressed by NUDF overexpression (Figure 2B), suggesting that even in the absence of CLIPA, NUDF overexpression still bypassed the requirement for NUDE. The phenotype of ΔclipA/ΔnudE double deletion mutant was also suppressed by overexpression of the N-terminal, NUDF-binding domain of NUDE, which was not observed in comets (Figure 2B).

Overexpression of NUDF could enhance its targeting and thus bypass the requirement for CLIPA and NUDE. To examine the localization of NUDF when it is produced in excess, we grew the GFP-nudF/ΔclipA/ΔnudE and control strains on medium with threonine as a carbon source, which is a strong inducer of the alcA promoter (the GFP::nudF fusion gene is under the control of the alcA promoter). Under these conditions, the GFP-nudF/ΔnudE and GFP-nudF/ΔclipA/ΔnudE strains had a nearly wild-type morphology and growth rate (as does GFP-nudF/ΔclipA strain), consistent with the suppression of ΔnudE and ΔnudE/ΔclipA mutations by nudF overexpression. NUDF comets were not detected in the ΔclipA/ΔnudE mutant but were present in control strains (Supplemental Movie 16). Although the intense background fluorescence in the cytoplasm would mask any little increase of GFP-NUDF at the microtubule plus end, this result suggests that the large excess amount of NUDF in the cell may bypass the requirement of having NUDF highly concentrated at the plus end for function.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we have identified CLIPA, the CLIP-170 homologue in the filamentous fungus A. nidulans. We found that CLIPA not only promotes microtubule growth as shown with its homologues in other systems but also promotes catastrophe after the microtubules reach the hyphal tip. Despite the alteration in microtubule dynamics, the clipA deletion mutant does not show an obvious nud phenotype as exhibited by mutants of cytoplasmic dynein or its regulators such as dynactin or NUDF (LIS1/Pac1). Our genetic analyses have revealed that CLIPA and NUDE, another dynein regulator, play overlapping roles in recruiting NUDF to the microtubule plus end. Double deletion of NUDE and CLIPA almost abolishes plus-end localization of NUDF and produces an obvious nud phenotype, which can be suppressed by NUDF overexpression. In addition, the plus-end targeting of CLIPA itself is also regulated, interestingly, by different targeting mechanisms under different physiological conditions. These results and their implications are discussed in more detail below.

Function of CLIPA in Microtubule Growth and Shrinkage

The microtubule plus-end localization of +TIPs seems to be evolutionarily conserved. However, the targeting mechanisms and cellular functions of the +TIPs seem to differ to certain degrees among different species (reviewed by Carvalho et al., 2003; Akhmanova and Hoogenraad, 2005). CLIP-170 and its homologues have been implicated in promoting microtubule growth in different experimental systems. Its function in regulating microtubule dynamics has been first suggested by studies of fungal homologues of CLIP-170. Null mutants of S. cerevisiae Bik1 and S. pombe Tip1 exhibit very short cytoplasmic microtubules, which is caused by an increase of catastrophe frequency in the case of S. pombe (Berlin et al., 1990; Brunner and Nurse, 2000). In S. cerevisiae, overexpression of Kip2, which should increase the plus-end accumulation of Bik1, stabilizes microtubule ends at the cortex, presumably due to the growth-promoting effect of excess Bik1 (Carvalho et al., 2004). In mammalian Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells, expression of a dominant negative Δhead CLIP-170 that displaces the endogenous protein from the plus end lowers the rescue frequency so that a shrinking microtubule is more likely to shrink all the way back to the centrosome (Komarova et al., 2002a). Thus, CLIP-170 is considered as a rescue factor in mammalian cells. In the ΔclipA mutant in A. nidulans, more microtubules fail to grow all the way to the hyphal tip, which is consistent with CLIPA being a growth-promoting factor. However, when microtubule ends reach the hyphal tip, they tend to remain there much longer without undergoing long-range shrinkage compared with those in wild-type cells. This result is unexpected because it has never been found in any other experimental systems where CLIP-170 and its homologues have been studied. The observed stabilization may be due to the inability of microtubules to switch from growth to shrinkage when they hit the hyphal tip in the absence of CLIPA.

It should be noted that the normal microtubule behaviors in A. nidulans and cultured CHO cells are not identical. Most microtubules in A. nidulans, after hitting the hyphal tip, tend to undergo long-distance shrinkage (most likely to the MTOC), whereas in CHO cells, most microtubules, after hitting the cortex, tend to undergo short-distance shrinkage followed by rescue (Komarova et al., 2002b). Although the reason behind this difference is unclear, it seems that CLIP-170 and its homologues are all used to maintain the normal behavior of microtubules in a given cell type, but they may use different modes of regulation to achieve this goal.

The CLIP-170 family members are not the only +TIPs that regulate microtubule dynamics in different ways. Functional analyses of EB1 and its Drosophila or yeast homologues indicate that these proteins promote microtubule growth and dynamicity (Tirnauer et al., 1999; Rogers et al., 2002; Tirnauer et al., 2002; Ligon et al., 2003). The XMAP/TOG/Dis1/DdCP224/Stu2 family of +TIPs also seems to regulate microtubule dynamics in various ways, including promoting microtubule growth and dynamics in vivo, and promoting microtubule depolymerization and dynamics in vitro (Gard and Kirschner, 1987; Vasquez et al., 1994; Wilde and Zheng, 1999; Tournebize et al., 2000; Kosco et al., 2001; Severin et al., 2001; Pearson et al., 2003; Shirasu-Hiza et al., 2003; van Breugel et al., 2003; Holmfeldt et al., 2004; Tanaka et al., 2005; Chen et al., 2006; reviewed by Ohkura et al., 2001; McNally, 2003; Popov and Karsenti, 2003; Akhmanova and Hoogenraad, 2005; Bloom, 2005). Due to the complexity of interactions among different +TIPs in vivo, it is hard to judge whether a +TIP affects microtubule dynamics directly or indirectly through other +TIPs. In this context, the differences in targeting mechanisms of +TIPs in various systems may also contribute to the observed functional differences of homologous proteins in influencing microtubule dynamics. Previously, we have observed that cytoplasmic microtubules in dynein and nudF mutants are less dynamic (Han et al., 2001), which is similar to what has been observed in yeast dynein mutants (Carminati and Stearns, 1997). Although the clipA mutant does not produce an obvious nud phenotype, it cannot be completely ruled out that this observed effect of clipA deletion in microtubule dynamicity could be attributed to a less functional dynein at the microtubule plus end. It should also be noted that CLIP-170 and its homologues may allow the microtubules to interact with the cell cortex in different systems to achieve a variety of functions, including localized microtubule capture by the cortex and localized actin assembly (reviewed by Galjart, 2005; Martin et al., 2005; reviewed by Martin and Chang, 2005). Thus, it is possible that interaction of CLIPA with a cortical protein localized at the hyphal tip may be required for modulating microtubule dynamicity locally.

Despite the effect on microtubule dynamics, CLIP-170 and its homologues are not essential for growth. In S. cerevisiae, Bik1 is only critical for the reproduction of polyploid cells (Lin et al., 2001; reviewed by Storchova and Pellman, 2004) and for mating (Berlin et al., 1990; Molk et al., 2006). Recent work on a CLIP-170 knockout mouse has detected a critical function of CLIP-170 only during spermatogenesis when CLIP-170 functions as a structural protein rather than a +TIP (Akhmanova et al., 2005). In A. nidulans, although initial growth of hyphae seemed slower in the ΔclipA mutant based on microscopic observations, colony growth was not severely inhibited, suggesting that A. nidulans may adapt to the change of microtubules to expand the colony. It is also possible that microtubule dynamics may be regulated by different mechanisms at different stages of A. nidulans colony growth (Horio and Oakley, 2005).

CLIPA and NUDE Are Important for the Plus-End Localization of NUDF

In this current study, we have found that the CLIP-170 homologue, CLIPA, and NUDE are important for targeting NUDF to the plus ends. In the ΔnudE/ΔclipA double mutant, GFP-NUDF comets are no longer observed. This is not due to a gross change in the cytoplasmic microtubule network or degradation of GFP-NUDF in the double mutant. CLIPA and NUDE are both +TIPs themselves. Physical interactions have been detected between CLIP-170/Bik1 and LIS1/Pac1 and between NUDE/Nudel/Ndl1 and NUDF/LIS1/Pac1 in mammalian cells, S. cerevisiae, and A. nidulans (Efimov and Morris, 2000; Niethammer et al., 2000; Sasaki et al., 2000; Coquelle et al., 2002; Sheeman et al., 2003; Lansbergen et al., 2004; Li et al., 2005a). Based on these results, we suggest that NUDF/LIS1 hitchhikes on CLIPA and NUDE to locate to the plus end.

LIS1 is a causal gene for human lissencephaly (reviewed by Reiner, 2000), a disease that may be caused by defective cell migration and cell division during brain development (reviewed by Morris, 2000; Gupta et al., 2002; Tsai and Gleeson, 2005; Tsai et al., 2005). It is a regulator of dynein function in many different cell types and has been shown to interact with the IC and the heavy chain of dynein and the dynamitin subunit of dynactin (reviewed by Morris et al., 1998; Sasaki et al., 2000; Tai et al., 2002). Previously, we have found that in A. nidulans, plus-end-localized dynein comets are more prominent in the absence of NUDF/LIS1 or its binding protein NUDE (Efimov, 2003; Zhang et al., 2003). In this study, we have found that CLIPA and NUDE are not important for plus-end localization of dynein but are important for plus-end localization of NUDF. This result further supports the notion that in A. nidulans, plus-end targeting mechanism of dynein differs from that of NUDF. It should be noted, however, that dynein/dynactin may stabilize plus-end localization of NUDF because plus-end accumulation of NUDF was decreased in mutants that are defective in plus-end localization of dynein/dynactin (Zhang et al., 2003).

Our results have revealed interesting differences and similarities compared with results obtained from yeasts or mammalian cells. In S. cerevisiae, although the effect of Bik1/CLIP-170 on function and localization of Pac1 is similar to our current result (Sheeman et al., 2003; Li et al., 2005a), Bik1/CLIP-170, Pac1/LIS1, and Ndl1/Nudel are all important for plus-end localization of dynein (Lee et al., 2003; Sheeman et al., 2003; Li et al., 2005). In mammalian cells, knocking down of CLIP-170 with RNAi reduces the plus-end accumulation of the p150 dynactin, suggesting that a portion of p150 may hitchhike on CLIP-170 (Lansbergen et al., 2004; Akhmanova et al., 2005). Such an effect was not obvious in A. nidulans (Supplemental Movies 5 and 6). The role of dynactin in plus-end localization of dynein may also differ in different systems. In A. nidulans, several loss-of-function mutations in the dynactin complex negatively affect plus-end localization of dynein (Xiang et al., 2000; Zhang et al., 2003), whereas in S. cerevisiae, loss of dynactin enhances plus-end localization of dynein (Lee et al., 2003; Sheeman et al., 2003). Interestingly, in S. pombe, dynactin and Tip1 (CLIP-170 homologue) may cooperate in regulating dynein localization (Niccoli et al., 2004). It is not clear why these cross-species differences exist. Further studies will be needed to address whether these dynein regulators have any overlapping functions in different systems, and how and why the mechanisms of regulation diverged during evolution.

Evidence from the filamentous fungus N. crassa and the dimorphic fungus Ustilago maydis suggests that in contrast to the budding yeast, these fungi use dynein not only for spindle orientation/nuclear migration but also for moving vesicular cargoes (Seiler et al., 1999; Lee et al., 2001; Riquelme et al., 2002; Wedlich-Soldner et al., 2002a,b; reviewed by Vale, 2003; Xiang and Plamann, 2003; Xiang and Fischer, 2004). Because the regulation of plus-end targeting of dynein seems to be similar among A. nidulans and these two fungi (Minke et al., 1999; Efimov, 2003; Zhang et al., 2003; Straube et al., 2005; Steinberg, personal communication), it is most likely that A. nidulans dynein is also a motor for vesicular cargoes and microtubule-plus-end localization of dynein is regulated accordingly for moving vesicles and organelles in vivo. However, plus-end localization of dynein/dynactin in A. nidulans also shows interesting differences compared with that in mammalian cells where plus-end-localized dynein/dynactin is implicated in vesicular transport (Vaughan et al., 2002; reviewed by Vaughan, 2005). In mammalian cells, dynactin can only be observed at growing microtubule ends (Vaughan et al., 2002). In addition, plus-end accumulation of dynein is quite weak but can be enhanced after cells are treated with cold temperature, presumably due to slowing down of the minus-end-directed transport (Vaughan et al., 1999). In A. nidulans, backtracking of dynein and dynactin comets suggests that they are most likely accumulated not only to the growing but also to the shrinking end, similar to yeast dynein at the plus end (Lee et al., 2003; Sheeman et al., 2003). Although accumulation to the shrinking end most likely reflects the bulk behavior of a dynamic population of molecules rather than that of a population of stably associated molecules, a possibility that dynein at the shrinking end may be used for coupling vesicles for minus-end-directed transport cannot be ruled out at present. In this context, it should be noted that in a previous study in higher eukaryotic cells, ER membranes were shown to move in the cell by riding on the dynamic plus ends of microtubules (Waterman-Storer and Salmon, 1998).

Roles of Kinesin in Plus-End Localization of CLIPA

Although the plus-end-tracking behavior of mammalian CLIP-170 is most likely achieved by a copolymerization/release mechanism (Diamantopoulos et al., 1999; Perez et al., 1999; Folker et al., 2005), in both budding and fission yeast a transport mechanism involving Kip2/Tea2 has been demonstrated (Busch et al., 2004; Carvalho et al., 2004). One possibility was that the difference in microtubule dynamics in these species causes the mechanisms of plus-end targeting to have evolved in different directions. The growth rate of yeast microtubules may be lower compared with that of mammalian cells according to measurements in these cells although the measurements were done at different temperatures (Shelden and Wadsworth, 1993; Tirnauer et al., 1999; Drummond and Cross, 2000). If CLIP-170 and its homologues had the same releasing rates, then other mechanisms would be needed to produce a steady-state accumulation of the yeast proteins at the plus end for function. However, our current result seems to argue against this possibility. In A. nidulans, the rate of microtubule growth is similar to that of mammalian cells (Shelden and Wadsworth, 1993; Han et al., 2001). Nevertheless, we have observed a clear enhancement function of both the KipA kinesin (Kip2/Tea2 homologue) and the KINA conventional kinesin for plus-end accumulation of CLIPA. More interestingly, such a function of the kinesins was observed at 42°C, a temperature at which microtubule growth rate is much higher (18.50 ± 4.80 μm/min; n = 26) compared with that at 32°C (9.10 ± 2.13 μm/min; n = 29) as measured under otherwise the same conditions in this study.

Because we are not able to see clear speckles along the microtubule that can be used for a more detailed analysis on the mechanism of CLIPA localization, one possibility is that these kinesins impact localization of CLIPA indirectly. For example, loss of kinesins may affect the microtubule growth rate, thereby affecting the rate of incorporation or release of CLIPA. However, we found that although the average intensity of comets in the kinesin mutants was significantly lower, these comets did move at a similar speed toward the hyphal tip compared with the speed of comets in wild-type cells (Figure 8, see slopes of the kymographs; our unpublished data). Thus, the lower accumulation cannot be explained by an altered microtubule growth rate in the kinesin mutants. Given the previous results in yeasts, and the fact that the effect of the KipA kinesin is more significant than that of KINA, it is most likely that the KipA kinesin may transport CLIPA toward the plus end to enhance its plus-end accumulation. Similar to the situation in yeast, KipA itself is also a +TIP, and its plus-end localization depends on its intrinsic motor activity (Konzack et al., 2005). Accumulation of kinesins at the plus end suggests that the rate of their movements at the plus end is lower compared with that along the microtubule. This may be due to a specific plus-end structure and/or interactions with other +TIPs (Desai and Mitchison, 1997; Carvalho et al., 2003; Akhmanova and Hoogenraad, 2005; Galjart, 2005). It is also possible that during a two-headed walking cycle of kinesin, detachment of one head is accelerated by the other head (Hancock and Howard, 1999). Thus, after the leading head moves off a microtubule, the trailing head may take much longer to detach from the microtubule, thereby preventing it from quickly falling off the track.

Backtracking of CLIP-170 homologues has so far only been observed in S. cerevisiae and A. nidulans (Figure 8 and Supplemental Movie 11; Carvalho et al., 2004). Although a transport mechanism may in theory explain such a phenomenon if a sufficient amount of motors is available (Galjart and Perez, 2003; Wu et al., 2006), other mechanisms cannot be excluded. For example, these proteins may bind through other proteins or directly to the shrinking end of a cytoplasmic microtubule like a member of the Kinesin-13 family or the Kinesin-14 family (Mennella et al., 2005; Sproul et al., 2005; Molk et al., 2006). Our initial analysis of CLIPA localization in this study further demonstrates the complexity associated with the targeting mechanisms of the CLIP-170 family of +TIPs. It should be noted that the transport mechanism is not the only targeting mechanism in fungi because in the kinesin mutants the CLIP-170 homologues did not completely disappear from the plus end (Figure 8; Busch et al., 2004; Carvalho et al., 2004). Kinesin-dependent transport may be particularly useful to enhance the plus-end localization of CLIP-170 homologues on longer microtubules, because in the kip2Δ mutant the reduction of plus-end accumulation of Bik1 is less striking on shorter microtubules emanated from the MTOC (Carvalho et al., 2004). It is most likely that CLIP-170 and its homologues all have intrinsic affinity for growing microtubule ends, but its microtubule plus-end accumulation may be enhanced by different proteins. Besides the Kip2/Tea2/KipA kinesins in fungi, other proteins such as EB1 and its S. pombe homologue Mal3 may be used for a transient stabilization of these proteins at the plus ends (Busch et al., 2004; Komarova et al., 2005). Interestingly, the EB1 homologue Bim1 is not required for the plus-end accumulation of Bik1 in S. cerevisiae (Carvalho et al., 2004). These results may explain why backtracking of CLIP-170 homologue is observed in the budding yeast but not in the fission yeast where a transport mechanism is also important for the plus-end accumulation of the CLIP-170 homologue Tip1 (Busch et al., 2004; Akhmanova and Hoogenraad, 2005). The EB1 homologue in A. nidulans is also a +TIP (Liu, personal communication), and its role in plus-end accumulation of CLIPA needs to be studied in the future.

It is unclear why in A. nidulans the kinesins are required only at a higher temperature. At a lower temperature (32°C), plus-end accumulation of CLIPA is independent of KipA, and it seems that a steady-state accumulation of CLIPA is established immediately after the plus end is emanated from the MTOC. Therefore, it seems unlikely that the transport mechanism is important at 32°C. That different mechanisms are used for supporting plus-end accumulation of +TIPs under different physiological conditions is a novel phenomenon that deserves to be further explored. Previous studies in A. nidulans have indicated that different proteins may be used at different temperatures for various functions. For example, the 8-kDa dynein light chain (NUDG) is essential for dynein function only at an elevated temperature of 42°C (Liu et al., 2003). It is possible that temperature may influence protein folding and/or protein complex formation, thereby affecting the specific requirement for different proteins.

Role of NUDE in NUDF Function

Physical interaction of NUDE with NUDF has been established in A. nidulans (Efimov and Morris, 2000). In mammalian cells, two NUDE homologues have been found, one is mNUDE (recently called “Nde1”) (Feng et al., 2000; Feng and Walsh, 2004), and the other is Nudel (recently called “Ndel1”) (Niethammer et al., 2000; Sasaki et al., 2000; Toyo-oka et al., 2003; Yan et al., 2003; Liang et al., 2004; Shu et al., 2004). Physical interactions between the NUDE homologues and LIS1 and/or dynein have been demonstrated previously (Feng et al., 2000; Niethammer et al., 2000; Sasaki et al., 2000; Liang et al., 2004; Li et al., 2005a). In this study, we have found that plus-end comets of GFP-NUDE are present in deletion mutants of dynein heavy chain and NUDF; thus, NUDE is targeted to the plus end independently of dynein and NUDF. Moreover, NUDE does not depend on CLIPA for its plus-end localization. Whether NUDE targets to microtubule plus end by itself or depends on any other +TIPs for its localization is not clear. It is also not clear why GFP-NUDE comets are not present in every cell. A recent study in S. cerevisiae shows that a GFP-labeled NUDE homologue, Ndl1, is only present at the plus ends transiently and thus it is only observed on a low percentage of microtubules (Li et al., 2005a). It seems that NUDE/Ndl1 is not essential as long as NUDF/Pac1 begins to function properly, because the ΔnudE/Δndl1 mutant phenotype is suppressed by nudF/Pac1 overexpression (Efimov, 2003; Li et al., 2005a). A similar conclusion has also been reached in mammalian cells concerning the relationship between Nudel and LIS1 (Shu et al., 2004).

In this study, we have shown that NUDE plays an overlapping role with CLIPA in targeting of NUDF to the plus end at 32°C. In the absence of CLIPA, overexpression of NUDF is still able to suppress the nudE deletion phenotype, suggesting that the originally observed suppression of the nudE phenotype does not rely on an enhanced plus-end targeting of NUDF by CLIPA. In the double deletion mutant, even when GFP-NUDF is overexpressed, we did not detect any obvious comets. Although the high fluorescence background may mask the faint comets, these data suggest to us that if NUDF at the plus end is required for dynein function, there are probably more NUDF molecules present at the plus end than needed. Alternatively, a proper interaction between dynein and NUDF (directly or indirectly), rather than plus-end localization of NUDF per se, is more critical for dynein function. Overexpression of NUDF may facilitate dynein-NUDF interactions, which, under normal conditions, may be facilitated by localization of NUDF to the microtubule plus end where dynein and dynactin are both concentrated.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Reinhard Fischer for A. nidulans kipA and kinA deletion/disruption strains, and Gero Steinberg and Bo Liu for communicating unpublished results on plus-end-tracking proteins in U. maydis and in A. nidulans. We are indebted to Liz Oakley for a careful and helpful reading of the manuscript. We initially identified the clipA gene using A. nidulans sequence data in the Cereon Microbial Sequence Database. We thank the Monsanto Company for providing access to their A. nidulans sequence before it was made public. This work was supported by a Scientist Development grant from the American Heart Association (to V.P.E.), National Institutes of Health Grant GM-069527-01 (to X. X.), and Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences intramural Grant R071GO (to X. X.).

This article was published online ahead of print in MBC in Press (http://www.molbiolcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1091/mbc.E05-11-1084) on February 8, 2006.

Abbreviations used: aa, amino acids; bp(s), base pair(s); GFP, green fluorescent protein; MT, microtubule; MTOC, microtubule-organizing center; NUDE-C, COOH-terminal domain of the NUDE protein; NUDE-N, NH2-terminal coiled coil domain of the NUDE protein; ts, temperature-sensitive.

The online version of this article contains supplemental material at MBC Online (http://www.molbiolcell.org).

References

- Arnal, I., Heichette, C., Diamantopoulos, G. S., and Chretien, D. (2004). CLIP-170/tubulin-curved oligomers coassemble at microtubule ends and promote rescues. Curr. Biol. 14, 2086-2095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akhmanova, A., and Hoogenraad, C. C. (2005). Microtubule plus-end-tracking proteins: mechanisms and functions. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 17, 47-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akhmanova, A., et al. (2005). The microtubule plus-end-tracking protein CLIP-170 associates with the spermatid manchette and is essential for spermatogenesis. Genes Dev. 19, 2501-2515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berlin, V., Styles, C. A., and Fink, G. R. (1990). BIK1, a protein required for microtubule function during mating and mitosis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, colocalizes with tubulin. J. Cell Biol. 111, 2573-2586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloom, K. (2005). Chromosome segregation: seeing is believing. Curr. Biol. 15, R500-R503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunner, D., and Nurse, P. (2000). CLIP170-like tip1p spatially organizes microtubular dynamics in fission yeast. Cell 102, 695-704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busch, K. E., Hayles, J., Nurse, P., and Brunner, D. (2004). Tea2p kinesin is involved in spatial microtubule organization by transporting tip1p on microtubules. Dev. Cell 6, 831-843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carminati, J. L., and Stearns, T. (1997). Microtubules orient the mitotic spindle in yeast through dynein-dependent interactions with the cell cortex. J. Cell Biol. 138, 629-641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho, P., Gupta, M. L., Jr., Hoyt, M. A., and Pellman, D. (2004). Cell cycle control of kinesin-mediated transport of Bik1 (CLIP-170) regulates microtubule stability and dynein activation. Dev. Cell 6, 815-829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho, P., Tirnauer, J. S., and Pellman, D. (2003). Surfing on microtubule ends. Trends Cell Biol. 13, 229-237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Q., Li, H., and De Lozanne, A. (2006). Contractile ring-independent localization of DdINCENP, a protein important for spindle stability and cytokinesis. Mol. Biol. Cell 17, 779-788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coquelle, F. M., et al. (2002). LIS1, CLIP-170's key to the dynein/dynactin pathway. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22, 3089-3102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai, A., and Mitchison, T. J. (1997). Microtubule polymerization dynamics. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 13, 83-117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamantopoulos, G. S., Perez, F., Goodson, H. V., Batelier, G., Melki, R., Kreis, T. E., and Rickard, J. E. (1999). Dynamic localization of CLIP-170 to microtubule plus ends is coupled to microtubule assembly. J. Cell Biol. 144, 99-112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drummond, D. R., and Cross, R. A. (2000). Dynamics of interphase microtubules in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Curr. Biol. 10, 766-775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dujardin, D. L., and Vallee, R. B. (2002). Dynein at the cortex. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 14, 44-49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efimov, V. P. (2003). Roles of NUDE and NUDF proteins of Aspergillus nidulans: insights from intracellular localization and overexpression effects. Mol. Biol. Cell 14, 871-888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efimov, V. P., and Morris, N. R. (2000). The LIS1-related NUDF protein of Aspergillus nidulans interacts with the coiled-coil domain of the NUDE/RO11 protein. J. Cell Biol. 150, 681-688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng, Y., Olson, E. C., Stukenberg, P. T., Flanagan, L. A., Kirschner, M. W., and Walsh, C. A. (2000). LIS1 regulates CNS lamination by interacting with mNudE, a central component of the centrosome. Neuron 28, 665-679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng, Y., and Walsh, C. A. (2004). Mitotic spindle regulation by Nde1 controls cerebral cortical size. Neuron 44, 279-293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Abalos, J. M., Fox, H., Pitt, C., Wells, B., and Doonan, J. H. (1998). Plant-adapted green fluorescent protein is a versatile vital reporter for gene expression, protein localization and mitosis in the filamentous fungus, Aspergillus nidulans. Mol. Microbiol. 27, 121-130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, R., and Timberlake, W. E. (1995). Aspergillus nidulans apsA (anucleate primary sterigmata) encodes a coiled-coil protein required for nuclear positioning and completion of asexual development. J. Cell Biol. 128, 485-498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folker, E. S., Baker, B. M., and Goodson, H. V. (2005). Interactions between CLIP-170, tubulin, and microtubules: implications for the mechanism of CLIP-170 plus-end tracking behavior. Mol. Biol. Cell 16, 5373-5384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukata, M., Watanabe, T., Noritake, J., Nakagawa, M., Yamaga, M., Kuroda, S., Matsuura, Y., Iwamatsu, A., Perez, F., and Kaibuchi, K. (2002). Rac1 and Cdc42 capture microtubules through IQGAP1 and CLIP-170. Cell 109, 873-885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galagan, J. E., et al. (2005). Sequencing of Aspergillus nidulans and comparative analysis with A. fumigatus and A. oryzae. Nature 438, 1105-1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galjart, N. (2005). CLIPs and CLASPs and cellular dynamics. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 6, 487-498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galjart, N., and Perez, F. (2003). A plus-end raft to control microtubule dynamics and function. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 15, 48-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gard, D. L., and Kirschner, M. W. (1987). A microtubule-associated protein from Xenopus eggs that specifically promotes assembly at the plus-end. J. Cell Biol. 105, 2203-2215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, A., Tsai, L .H., and Wynshaw-Boris, A. (2002). Life is a journey: a genetic look at neocortical development. Nat. Rev. Genet. 3, 342-355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han, G., Liu, B., Zhang, J., Zuo, W., Morris, N. R., and Xiang, X. (2001). The Aspergillus cytoplasmic dynein heavy chain and NUDF localize to microtubule ends and affect microtubule dynamics. Curr. Biol. 11, 719-724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hancock, W. O., and Howard, J. (1999). Kinesin's processivity results from mechanical and chemical coordination between the ATP hydrolysis cycles of the two motor domains. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96, 13147-13152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmfeldt, P., Stenmark, S., and Gullberg, M. (2004). Differential functional interplay of TOGp/XMAP215 and the KinI kinesin MCAK during interphase and mitosis. EMBO J. 23, 627-637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horio, T., and Oakley, B. R. (2005). The role of microtubules in rapid hyphal tip growth of Aspergillus nidulans. Mol. Biol. Cell 16, 918-926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karki, S., and Holzbaur, E. L. (1999). Cytoplasmic dynein and dynactin in cell division and intracellular transport. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 11, 45-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komarova, Y. A., Akhmanova, A. S., Kojima, S., Galjart, N., and Borisy, G. G. (2002a). Cytoplasmic linker proteins promote microtubule rescue in vivo. J. Cell Biol. 159, 589-599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komarova, Y. A., Vorobjev, I. A., and Borisy, G. G. (2002b). Life cycle of MTs: persistent growth in the cell interior, asymmetric transition frequencies and effects of the cell boundary. J. Cell Sci. 115, 3527-3539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komarova, Y., Lansbergen, G., Galjart, N., Grosveld, F., Borisy, G. G., and Akhmanova, A. (2005). EB1 and EB3 control CLIP dissociation from the ends of growing microtubules. Mol. Biol. Cell 16, 5334-5345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konzack, S., Rischitor, P. E., Enke, C., and Fischer, R. (2005). The role of the kinesin motor KipA in microtubule organization and polarized growth of Aspergillus nidulans. Mol. Biol. Cell 16, 497-506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosco, K. A., Pearson, C. G., Maddox, P. S., Wang, P. J., Adams, I. R., Salmon, E. D., Bloom, K., and Huffaker, T. C. (2001). Control of microtubule dynamics by Stu2p is essential for spindle orientation and metaphase chromosome alignment in yeast. Mol. Biol. Cell 12, 2870-2880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lansbergen, G., et al. (2004). Conformational changes in CLIP-170 regulate its binding to microtubules and dynactin localization. J. Cell Biol. 166, 1003-1014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, I. H., Kumar, S., and Plamann, M. (2001). Null mutants of the Neurospora actin-related protein 1 pointed-end complex show distinct phenotypes. Mol. Biol. Cell 12, 2195-2206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, W. L., Oberle, J. R., and Cooper, J. A. (2003). The role of the lissencephaly protein Pac1 during nuclear migration in budding yeast. J. Cell Biol. 160, 355-364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, J., Lee, W. L., and Cooper, J. A. (2005a). NudEL targets dynein to microtubule ends through LIS1. Nat. Cell Biol. 7, 686-690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, S., Oakley, C. E., Chen, G., Han, X., Oakley, B. R., and Xiang, X. (2005b). Cytoplasmic dynein's mitotic spindle pole localization requires a functional anaphase-promoting complex, gamma-tubulin, and NUDF/LIS1 in Aspergillus nidulans. Mol. Biol. Cell 16, 3591-3605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang, Y., Yu, W., Li, Y., Yang, Z., Yan, X., Huang, Q., and Zhu, X. (2004). Nudel functions in membrane traffic mainly through association with Lis1 and cytoplasmic dynein. J. Cell Biol. 164, 557-566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ligon, L. A., Shelly, S. S., Tokito, M., and Holzbaur, E. L. (2003). The microtubule plus-end proteins EB1 and dynactin have differential effects on microtubule polymerization. Mol. Biol. Cell 14, 1405-1417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin, H., de Carvalho, P., Kho, D., Tai, C. Y., Pierre, P., Fink, G. R., and Pellman, D. (2001). Polyploids require Bik1 for kinetochore-microtubule attachment. J. Cell Biol. 155, 1173-1184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, B., Xiang, X., and Lee, Y. R. (2003). The requirement of the LC8 dynein light chain for nuclear migration and septum positioning is temperature dependent in Aspergillus nidulans. Mol. Microbiol. 47, 291-301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin, S. G., and Chang, F. (2005). New end take off: regulating cell polarity during the fission yeast cell cycle. Cell Cycle 4, 1046-1049. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin, S. G., McDonald, W. H., Yates, J. R., 3rd, and Chang, F. (2005). Tea4p links microtubule plus ends with the formin for3p in the establishment of cell polarity. Dev. Cell 8, 479-491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNally, F. (2003). Microtubule dynamics: new surprises from an old MAP. Curr. Biol. 13, R597-R599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mennella, V., Rogers, G. C., Rogers, S. L., Buster, D. W., Vale, R. D., and Sharp, D. J. (2005). Functionally distinct kinesin-13 family members cooperate to regulate microtubule dynamics during interphase. Nat. Cell Biol. 7, 235-245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minke, P. F., Lee, I. H., Tinsley, J. H., Bruno, K. S., and Plamann, M. (1999). Neurospora crassa ro-10 and ro-11 genes encode novel proteins required for nuclear distribution. Mol. Microbiol. 32, 1065-1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]