Abstract

Objective

To determine the role of surgery in patients with Zollinger-Ellison syndrome (ZES) and multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN1) with either limited or advanced pancreatic endocrine tumors (PETs).

Summary Background Data

The role of surgery in patients with MEN1 and ZES is controversial. There have been numerous previous studies of surgery in patients with PETs; however, there are no prospective studies on the results of surgery in patients with advanced disease.

Methods

Eighty-one consecutive patients with MEN1 and ZES were assigned to one of four groups depending on the results of imaging studies. Group 1 (n = 17) (all PETs smaller than 2.5 cm) and group 3 (n = 8) (diffuse liver metastases) did not undergo surgery. All patients in group 2A (n = 17; single PET 2.5–6 cm [limited disease]) and group 2B (n = 31; two or more lesions, 2.5 cm in diameter or larger, or one lesion larger than 6 cm) underwent laparotomy. Tumors were preferably removed by simple enucleation, or if not feasible resection. Patients were reevaluated yearly.

Results

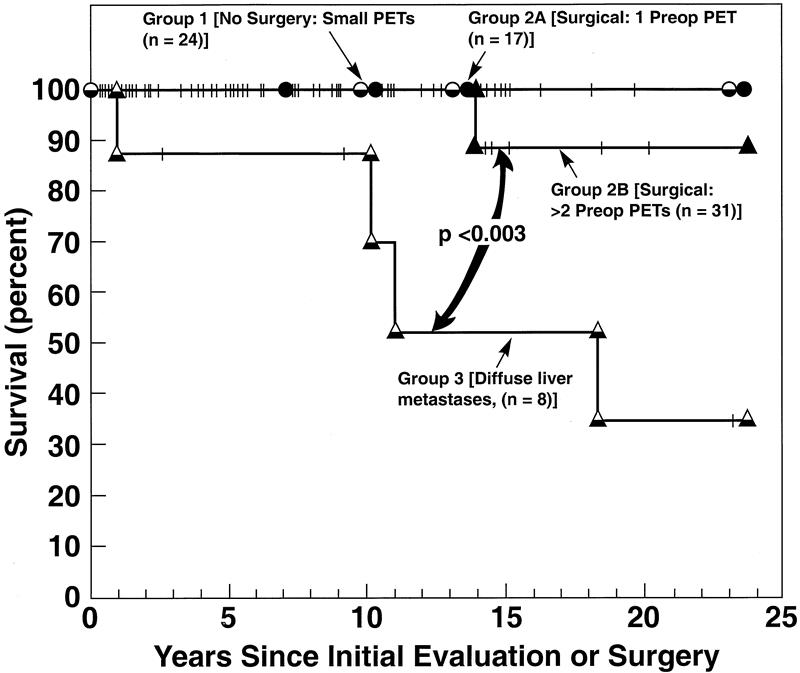

Pancreatic endocrine tumors were found in all patients at surgery, with groups 2A and 2B having 1.7 ± 0.4 and 4.8 ± 1 PETs, respectively. Further, 35% of the patients in group 2A and 88% of the patients in group 2B had multiple PETs, 53% and 84% had a pancreatic PET, 53% and 68% had a duodenal gastrinoma, 65% and 71% had lymph node metastases, and 0% and 12% had liver metastases. Of the patients in groups 2A and 2B, 24% and 58% had a distal pancreatectomy, 0% and 13% had a hepatic resection, 0% and 6% had a Whipple operation, and 53% and 68% had a duodenal resection. No patient was cured at 5 years. There were no deaths. The early complication rate, 29%, was similar for groups 2A and 2B. Mean follow-up from surgery was 6.9 ± 0.8 years, and during follow-up liver metastases developed in 6% of the patients in groups 2A and 2B. Groups 1, 2A, and 2B had similar 15-year survival rates (89–100%); they were significantly better than the survival rate for group 3 (52%).

Conclusions

Almost 40% of patients with MEN1 and ZES have advanced disease without diffuse distant metastases. Despite multiple primaries and a 70% incidence of lymph node metastases, tumor can be removed with no deaths and complication rates similar to those in patients with limited disease. Further, despite previous studies showing that patients with advanced disease have decreased survival rates, in this study the patients with advanced tumor who underwent surgical resection had the same survival as patients with limited disease and patients without identifiable tumor. This suggests that surgical resection should be performed in patients with MEN1 who have ZES and advanced localized PET.

Patients with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN1) have parathyroid hyperplasia, pancreatic endocrine tumors (PETs), pituitary adenomas, adrenal adenomas, and carcinoids. 1,2 Although PETs develop in 40% to 90% of patients with MEN1, 1,3,4 5% to 30% of patients die of malignant PETs, 5–8 and PETs are the leading cause of disease death, 5,8 the role of surgery in the treatment of PETs is controversial. 6,9–12 The controversy is whether surgery should be routinely performed and if so, when and what type of surgery. This has occurred because of a lack of understanding of the natural history of PETs and of the molecular basis of tumors, lack of prognostic factors to predict outcome, and lack of prospective studies on the results of surgery. Most surgical studies have been retrospective and have involved small numbers of patients, and surgical treatment of functional and nonfunctional tumors is usually included together. The later point is particularly important because almost all authorities agree that patients with MEN1 with a non-ZES functional tumor (insulinoma, glucagonoma, GRFoma, VIPoma) should routinely undergo surgical exploration because the medical treatment is less effective and they can be frequently cured. 1 Unfortunately, gastrinomas are the most common functional PET in patients with MEN1 and nonfunctional PETs are the most common PET, occurring in 80% to 100% of patients. 1,9,13 Because gastric acid hypersecretion can be controlled in almost every patient by proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), 9,14,15 similar to nonfunctional PETs, surgery is not required for treatment of the hormone-excess state. Therefore, each of the above controversies particularly involves the management of patients with MEN1 with gastrinomas and/or nonfunctional PETs.

Microscopic PETs are almost invariably found in patients with MEN1, and also larger PETs as well as duodenal gastrinomas are frequently multiple in patients with MEN1 and ZES. 16–18 Therefore, some have recommended that surgery not be performed on patients with ZES and MEN1 unless a single lesion is seen on preoperative imaging studies. 19 Numerous recent studies, primarily in patients with limited disease on imaging studies, provide compelling evidence that surgical resections or PET enucleations without a pancreaticoduodenectomy rarely result in cure in patients with ZES with MEN1. 19–24

In contrast to studies on patients with ZES and MEN1 with more limited disease, reviewed above, almost no surgical studies have examined the role of surgery in patients with MEN1 who have more advanced PETs. This study examines this question by analyzing the results of surgical exploration in 48 patients with MEN1 and ZES with both limited disease (i.e., a single lesion on preoperative imaging) or patients with more advanced disease (two or more lesions or one lesion larger than 6 cm). Follow-up after resection of both groups was compared with a cohort of similar, unoperated patients (n = 25) with either small PETs (<2.5 cm; n = 17) or diffuse metastatic disease (n = 8).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Since June 1972 at the National Institutes of Health, and since 1997 at the University of California at San Francisco, all patients with ZES and MEN1 admitted to our services have been included in this protocol. Eighty-one consecutive patients were eligible for the protocol, and all were entered into this protocol.

The diagnosis of ZES was based on acid secretory studies, measurement of fasting gastrin, as well as the results of secretin and calcium provocative tests. 25 Criteria for MEN1 in a patient with ZES have been described elsewhere. 26 Basal acid output was determined for each patient using methods described previously. 27 Doses of oral gastric antisecretory drug were determined as described previously. 27

Time from onset of the disease to exploration was determined for all patients as described previously. 25,28 Time of diagnosis of MEN1 or ZES was the time these diagnoses were first established by appropriate laboratory studies or when a physician established the diagnosis based on clinical presentation.

Specific Protocol

To be eligible for this protocol, all patients underwent an initial evaluation to establish the diagnoses of ZES and MEN1, 26 tumor localization studies, and acid secretory studies. 27,29 These patients also underwent yearly evaluations to assess acid secretory control, associated endocrinopathies, PET extent, and surgical results. Yearly evaluations included conventional imaging studies; somatostatin receptor scintigraphy (SRS) since 1994; assessment of parathyroid, pituitary, and adrenal function; assessment for gastric and thymic carcinoids; plasma hormone levels associated with functional PETs (gastrin, insulin, PP, 5-HIAA, chromogranin A, glucagons, calcitonin); and assessment of acid secretion as described previously. 12,26

The localization and the extent of PETs were evaluated in all patients as described elsewhere 30–33 by using upper gastrointestinal endoscopy and conventional imaging studies (computed tomography [CT scan], magnetic resonance imaging [MRI], transabdominal ultrasound, selective abdominal angiography and bone scanning). Somatostatin receptor scintigraphy was performed since 1994 as described previously. 34,35 At exploration, an extensive search for PETs was performed. 12,31,36,37 Briefly, palpation was performed after an extended Kocher maneuver and ultrasound with a 10-MHz real-time transducer was performed. 12 Since 1987, endoscopic transillumination of the duodenum was performed, 38 and a 3-cm longitudinal duodenotomy was centered in the anterolateral surface of the descending (second) duodenum to search for duodenal tumors. 12 After surgery, all patients had fasting serum gastrin levels and an secretin provocative test performed before discharge. 12,25,36

Tumors in the pancreatic head were enucleated. Tumors in the pancreatic body and tail were enucleated if possible; otherwise they were resected. Distal pancreatectomy was not routinely performed and was done only if multiple pancreatic body and/or tail tumors were present that could not be enucleated. 12,39 If multiple pancreatic head tumors were present that could not be enucleated, a pancreaticoduodenectomy was performed if the patient had given prior consent. A detailed inspection for peripancreatic, periduodenal, and portohepatic lymph nodes was carried out, and these were routinely removed. If liver metastases were present and not diffuse, they were wedge-resected with a 1-cm margin if possible; if this was not possible and they were localized, a segmented resection or lobectomy was performed.

Patients were reevaluated 3 to 6 months after the resection with conventional imaging studies, including angiography, SRS, and functional studies to assess disease activity (fasting gastrin levels, secretin test, acid secretory tests) 12,25,36,40 and at yearly intervals thereafter. Patients were defined as being disease-free of ZES if fasting serum gastrin levels were normal, the secretin test was negative (increase of <200 pg/mL after secretin), 40 and imaging studies, including SRS, were normal. 25 During yearly follow-up based on serial imaging studies, including SRS, it was determined whether liver metastases had developed. In all patients, this conclusion was histologically confirmed by biopsy, except for two patients in whom multiple small lesions had developed on conventional imaging and SRS from which biopsy samples could not be obtained percutaneously.

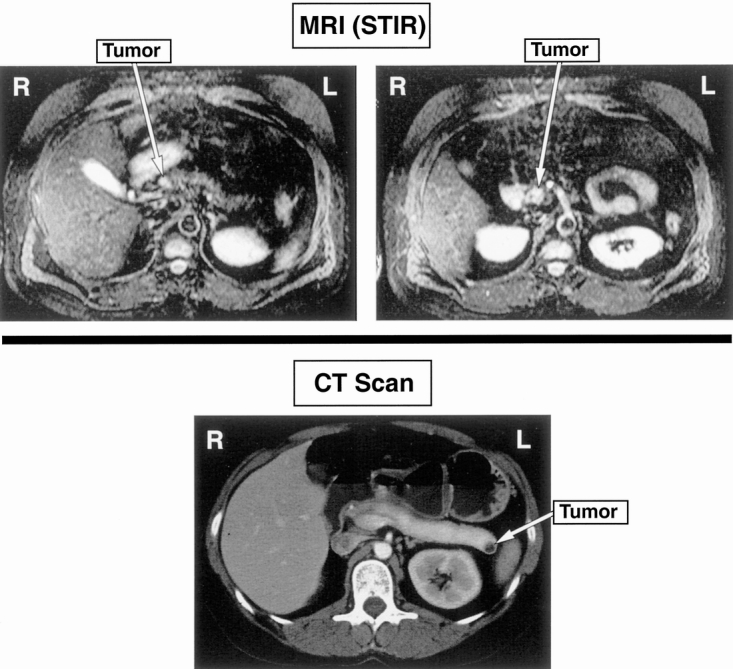

In this protocol, based on preoperative conventional imaging study results of the size and number of PETs and their extent, patients were stratified into one of four groups. Group 1 (patients with abdominal tumors <2.5 cm) did not undergo routine exploratory laparotomy unless another functional PET syndrome was present besides ZES (i.e., insulinoma, carcinoid syndrome, glucagonoma). Group 2 (patients with abdominal tumors 2.5 cm or larger) underwent exploratory laparotomy. Group 2 was subdivided in group 2A (a single tumor <6 cm in diameter) and group 2B (two or more tumors or a single tumor 6 cm or larger in diameter) (Fig. 1). Group 3 had diffuse metastatic disease in the liver and did not undergo routine exploratory laparotomy unless another non-ZES functional PET developed. 12,23,39 The presence of liver metastases was proven by liver biopsy.

Figure 1. MR of a patient with multiple tumors. 2B disease above and another patient with a solitary tumor, 2A disease (CT below).

Statistics

The Fisher exact test, the Student t test, the Mann-Whitney test, and analysis of variance were used. For a post hoc test, the Bonferroni/Dunn test was used. Values differing by P < .05 were considered significant. All continuous variables were reported as mean ± standard error of the mean. The probabilities of survival were calculated and plotted according to the Kaplan-Meier methods. 41

RESULTS

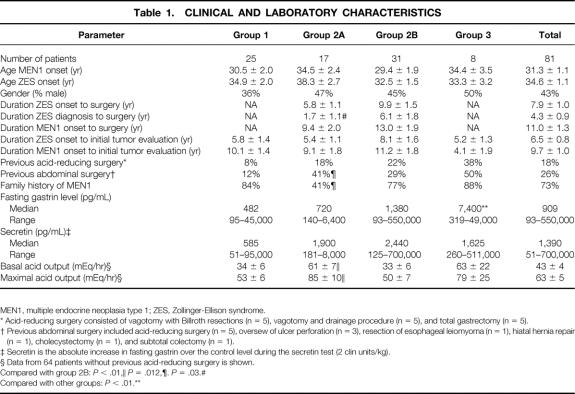

Eighty-one patients with MEN1 and ZES were included in the study (Table 1). These patients resemble other reports of patients with ZES and MEN1 in that not all of them had a positive family history for MEN1 (73% in our study). 6,42 Our patients were younger at onset of ZES (mean age 35) and were more frequently female (57%) than previous series of patients with ZES and MEN1. 6,19 The acid secretion rate, fasting gastrin level, and increase in gastrin after secretin were generally markedly increased, similar to patients with sporadic ZES. 9,12,27 One fourth of the patients had undergone abdominal surgery, and one fifth had had previous acid-reducing surgery.

Table 1. CLINICAL AND LABORATORY CHARACTERISTICS

MEN1, multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1; ZES, Zollinger-Ellison syndrome.

* Acid-reducing surgery consisted of vagotomy with Billroth resections (n = 5), vagotomy and drainage procedure (n = 5), and total gastrectomy (n = 5).

† Previous abdominal surgery included acid-reducing surgery (n = 5), oversew of ulcer perforation (n = 3), resection of esophageal leiomyoma (n = 1), hiatal hernia repair (n = 1), cholecystectomy (n = 1), and subtotal colectomy (n = 1).

‡ Secretin is the absolute increase in fasting gastrin over the control level during the secretin test (2 clin units/kg).

§ Data from 64 patients without previous acid-reducing surgery is shown.

Compared with group 2B:P < .01,

∥P = .012,

¶. P = .03.#

Compared with other groups:P < .01.**

The four patient groups generally had similar clinical and laboratory characteristics, except for a few differences. Group 3 (metastatic disease) patients had a higher fasting gastrin level. Group 2A (limited disease, surgery) differed from the surgical group with advanced disease (group 2B) in having a shorter ZES disease duration to surgery, a lower percentage with a positive family history of MEN1, and a higher acid secretion rate.

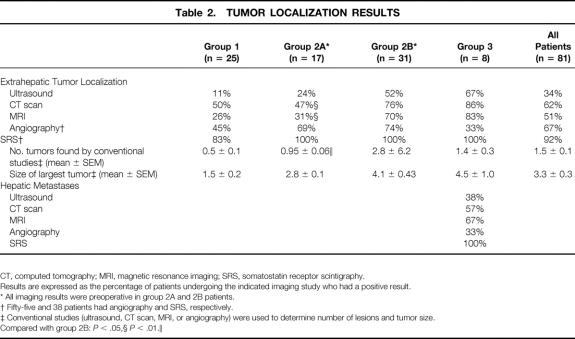

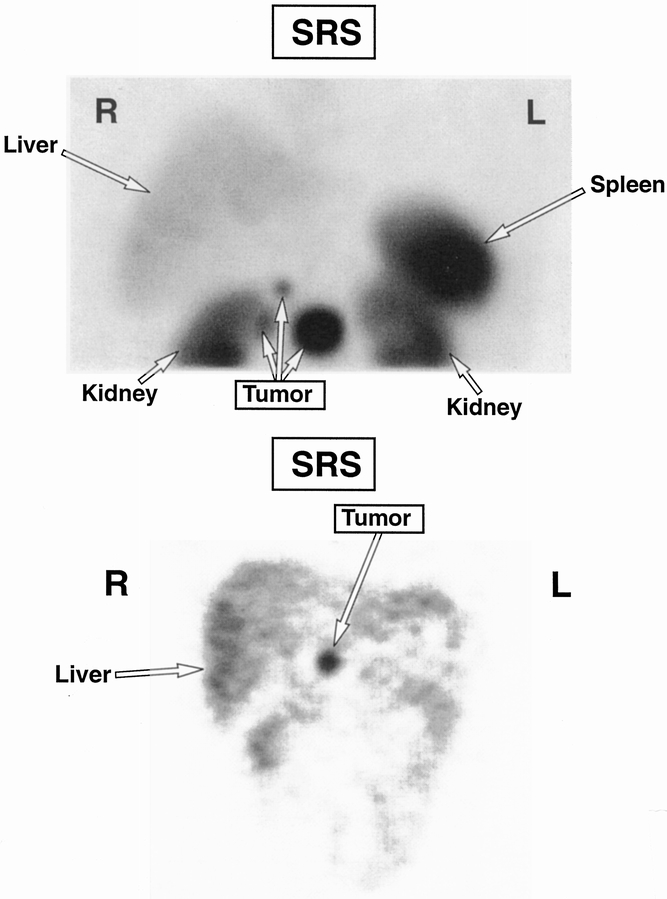

On the initial evaluation before surgery, 68% of patients in group 1 and 98% of patients in groups 2A, 2B, and 3 had a positive conventional imaging study localizing an extrahepatic PET (Table 2). In terms of sensitivity, the relative order was angiography most sensitive (67% of all patients) > CT > MRI > ultrasound. Somatostatin receptor scintigraphy was performed in 38 patients and localized an extrahepatic PET in 92% (Fig. 2). Surgical patients with advanced disease (group 2B) were more likely to have a positive conventional imaging study (CT, MRI), a larger number of extrahepatic lesions imaged (2.8 vs. 1), and larger extrahepatic tumors (4.1 vs. 2.8 cm in diameter) than surgical patients with more limited disease (group 2A). In patients with diffuse metastatic liver disease (group 3), MRI and CT were more sensitive than ultrasound; however, SRS was more sensitive than any conventional imaging study, being positive in 100% for a liver lesion.

Table 2. TUMOR LOCALIZATION RESULTS

CT, computed tomography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; SRS, somatostatin receptor scintigraphy.

Results are expressed as the percentage of patients undergoing the indicated imaging study who had a positive result.

* All imaging results were preoperative in group 2A and 2B patients.

† Fifty-five and 38 patients had angiography and SRS, respectively.

‡ Conventional studies (ultrasound, CT scan, MRI, or angiography) were used to determine number of lesions and tumor size.

Compared with group 2B:P < .05,

§P < .01.∥

Figure 2. Somatostatin receptor scintigraphy of a tumor in head of pancreas with adjacent nodal metastases.

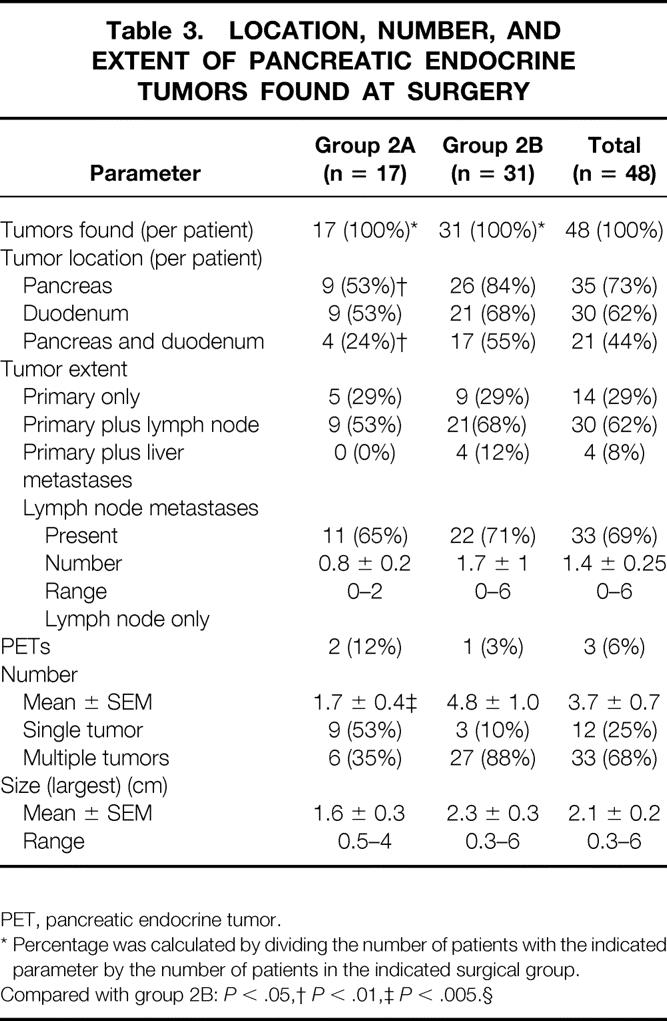

Pancreatic endocrine tumors were found in all patients at exploration (Table 3). Pancreatic tumors were found in 73% and were more frequent in patients with advanced disease (P = .026). Duodenal gastrinomas were found in 62% of patients and were equally frequent (53–68%) in both groups. Both a duodenal gastrinoma and a pancreatic PET were found in 44% of patients and were more frequent in patients with advanced disease in group 2B (55% vs. 24%, P = .036).

Table 3. LOCATION, NUMBER, AND EXTENT OF PANCREATIC ENDOCRINE TUMORS FOUND AT SURGERY

PET, pancreatic endocrine tumor.

* Percentage was calculated by dividing the number of patients with the indicated parameter by the number of patients in the indicated surgical group.

Compared with group 2B:P < .05,

†P < .01,

‡P < .005.§

Approximately one third of patients in both surgical groups had a primary PET only, with the majority of the remaining patients having a primary with lymph node metastases (53–68%) or lymph node metastases only (3–12%). Liver metastases were found at surgery in four patients with advanced disease (group 2B), all of whom had positive conventional imaging studies for liver metastases before exploration. Lymph node metastases were present with equal frequency in both surgical groups (65–71%), with group 2B showing a trend to a larger number of lymph node metastases (1.7 vs. 0.8, P = .084). The total number of PETs was almost three times greater in patients with advanced disease (group 2B) (4.8 vs. 1.7, P < .001): one patient in group 2B had 30 PETs. However, the mean size of the largest PET resected did not differ between the two groups (1.6 vs. 2.3, P = .18).

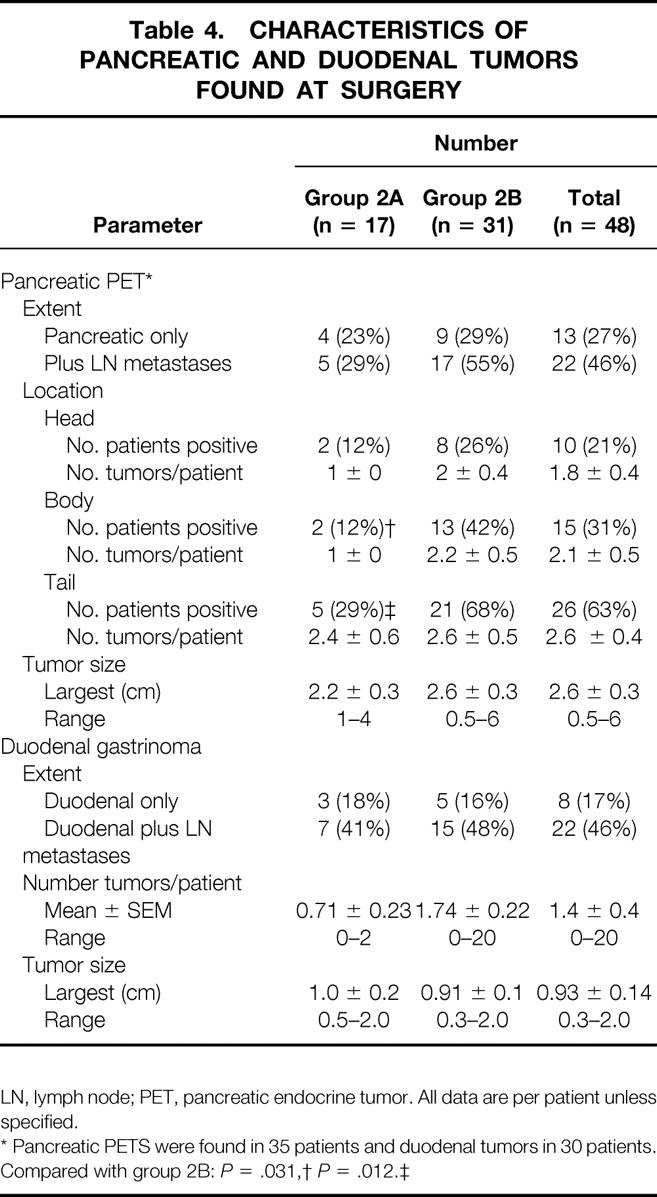

In the 73% of patients with a pancreatic PET, two thirds of these patients also had lymph node metastases (Table 4), with no significant difference in frequency in the two surgical groups (2A vs. 2B: 29% vs. 55%, P = .081). In both surgical groups, the pancreatic PETs were more frequently found in the pancreatic tail. However, the PET’s size was not significantly different in different pancreatic locations or in the different surgical groups. In the 82% of patients with duodenal gastrinomas, in two thirds of patients in both surgical groups, lymph node metastases were also present. The number of duodenal gastrinomas varied from 0 to more than 20 per patient; however, neither the number per patient nor the largest size differed between the two surgical groups.

Table 4. CHARACTERISTICS OF PANCREATIC AND DUODENAL TUMORS FOUND AT SURGERY

LN, lymph node; PET, pancreatic endocrine tumor. All data are per patient unless specified.

* Pancreatic PETS were found in 35 patients and duodenal tumors in 30 patients.

Compared with group 2B:P = .031,

†P = .012.‡

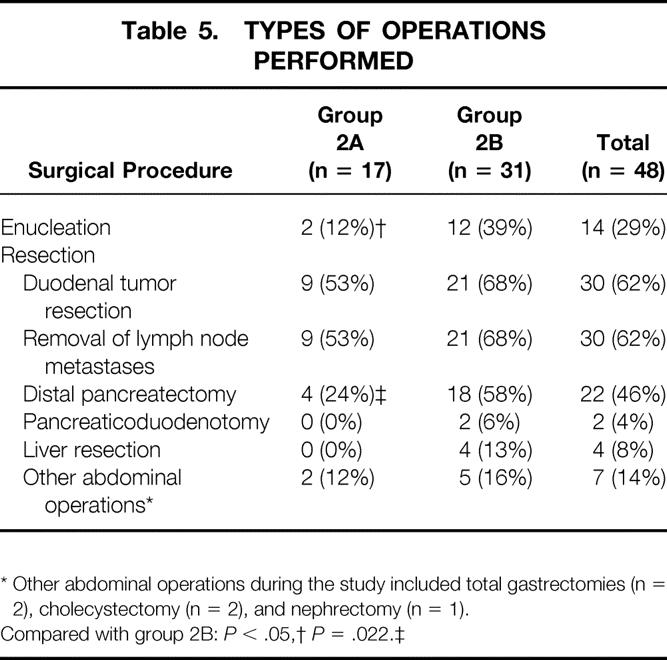

At exploration, enucleation of primarily pancreatic head tumors was performed in approximately one third of all surgical patients and was more frequently done in patients with advanced disease (2B vs. 2A: 37% vs. 12%, P = .0476, Table 5). The most common resections were for duodenal gastrinomas (62%) and lymph nodes (62%), followed by distal pancreatectomy (46%), liver resection (8%), and pancreaticoduodenectomy (4%). These operations were performed with equal frequency in both surgical groups, except for distal pancreatectomy, which was 2.5 times more frequent in patients with aggressive disease (2B vs. 2A: 58% vs. 24%, P = .022). Hepatic resections (n = 4) and pancreaticoduodenectomies (n = 2) were performed only in patients with aggressive disease (group 2B).

Table 5. TYPES OF OPERATIONS PERFORMED

* Other abdominal operations during the study included total gastrectomies (n = 2), cholecystectomy (n = 2), and nephrectomy (n = 1).

Compared with group 2B:P < .05,

†P = .022.‡

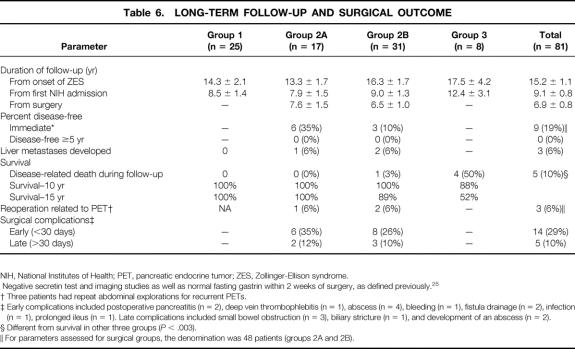

Approximately one third of all patients had an immediate surgical complication that delayed discharge (occurring within 30 days of the surgical resection), and this rate did not differ between the two surgical groups (Table 6). These early complications included primarily abscess and fistula drainage. Overall, 10% of patients had some late complication (>30 days after surgery) that was likely related to the surgery, and the rate was not different for the two groups. The most common late complications were small obstructions (2–10 years after resection) and abscess formation requiring drainage.

Table 6. LONG-TERM FOLLOW-UP AND SURGICAL OUTCOME

NIH, National Institutes of Health; PET, pancreatic endocrine tumor; ZES, Zollinger-Ellison syndrome.

<*> Negative secretin test and imaging studies as well as normal fasting gastrin within 2 weeks of surgery, as defined previously. 25

† Three patients had repeat abdominal explorations for recurrent PETs.

‡ Early complications included postoperative pancreatitis (n = 2), deep vein thrombophlebitis (n = 1), abscess (n = 4), bleeding (n = 1), fistula drainage (n = 2), infection (n = 1), prolonged ileus (n = 1). Late complications included small bowel obstruction (n = 3), biliary stricture (n = 1), and development of an abscess (n = 2).

§ Different from survival in other three groups (P < .003).

∥ For parameters assessed for surgical groups, the denomination was 48 patients (groups 2A and 2B).

In the immediate postoperative period (within 1 week of surgery), almost one fifth of patients showed no evidence of ZES, with normal fasting gastrin results and negative secretin tests. This result was significantly more frequent in patients with limited disease (2A vs. 2B: 35% vs. 10%, P = .039). During a mean follow-up of 6.9 ± 0.8 years since surgery, no patient in either surgical group was free of ZES at 5 years, with 70% of all patients having a follow-up of more than 5 years.

Liver metastases developed since exploratory surgery in 6% of the patients who did not have liver metastases at the time of surgery; there was no difference in the rate of development in the two surgical groups. The long-term survival rate in all four groups of patients since surgery or the initial tumor evaluation was excellent (88–100% at 10 years;Fig. 3). However, the 15-year disease-related survival rates were significantly better in group 1 and the two surgical groups (100%, 100%, 89%) compared with patients with diffuse metastatic disease (group 3: 52%;P < .003). During follow-up, only 6% of patients in the two surgical groups required reoperation related to growth of an additional PET.

Figure 3. Survival among the different groups of patients with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 and Zollinger-Ellison syndrome. Survival is plotted in the form of Kaplan and Meier. Pancreatic endocrine tumor (PET)-related survival is from the time of surgery (groups 2A and 2B) or from the initial evaluation for disease extent (groups 1 and 3). During follow-up 0 of 25 patients in group 1 (no surgery, PETs <2.5 cm), 0 of 17 patients in group 2A (surgery, limited disease), 1 of 31 patients in group 2B (surgery, advanced disease), and 4 of 8 patients with diffuse hepatic metastases (group 3) died of a PET-related cause.

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this study was to explore the role of abdominal exploratory laparotomy in patients with MEN1 and ZES whose hypersecretion was controlled medically, concentrating on patients with advanced, potentially resectable disease (group 2B). To accomplish this, the surgical results in consecutive patients with MEN1 and ZES with advanced disease were compared with those of a surgically treated group with limited disease (group 2A). Further, the long-term course after resection of both surgical groups was compared prospectively with that of patients with small PETs (<2.5 cm on imaging) who did not undergo surgical resection (group 1) and patients with diffuse hepatic metastases (group 3) who also did not undergo surgical resection.

In this study, patients were stratified into various clinical groups based on the results of preoperative imaging studies. The four groups differed in the role of surgery as well as other treatment modalities. This approach was taken because it was believed that this most closely mirrors the diagnostic and clinical approaches to a typical patient with MEN1 seen in clinical practice. The results of conventional preoperative imaging studies have been widely used to determine whether a given patient with MEN1 should be considered for surgical exploration. The parameters used by others previously included the presence or absence of a PET, 21 the size of the largest PET, 6,9,12,23 the number of PETs, 19,21 and the presence or absence of hepatic metastases. 11,16,43

Recently, SRS has been shown to be more sensitive than any conventional imaging study for localizing neuroendocrine tumors. 32,34,44,45 However, SRS was not used to stratify patients in the present study because its sensitivity and specificity for PETs in patients with MEN1 has not been well studied; it gives information only on lesion number, not size. This first point is especially important because patients with MEN1, especially with ZES, frequently have gastric carcinoid tumors, which can be mistaken for PETs on SRS. 46 Further, bronchial or thymic carcinoids can be visualized on SRS 44,45 and mistaken for distant metastases from a PET.

The findings at surgery in the 48 patients in the two surgical groups provide several important comparisons with previous studies. First, almost two thirds of the surgical patients, with no significant difference in the percentage in the two surgical groups, had a duodenal PET that was a gastrinoma. This result is consistent with previous studies that reported that 21% to 100% of patients with ZES and MEN1 have duodenal gastrinomas. 6,9,11,21,47 Our percentage of duodenal tumors may be an underestimation because 20% of patients underwent surgery before duodenotomy became routine. Duodenotomy is essential to detect duodenal gastrinomas. 31,36,48 Our results support this conclusion because a significantly lower percentage (40%) of duodenal gastrinomas were found without than with duodenotomy (77%). Our results suggest that 80% of patients with ZES and MEN1 have a duodenal gastrinoma. This result also suggests that 20% of patients with MEN1 and ZES have a pancreatic gastrinoma, a duodenal gastrinoma that was missed, or a gastrinoma in another location. Any of these possibilities may have occurred because recent studies provide evidence for all three possibilities in patients with ZES with and without MEN1. 9,21,39,47,49–53

Two thirds of patients with either duodenal gastrinomas or pancreatic PETs in both surgical groups had lymph node metastases. Lymph node metastases have been reported to occur in 18% to 98% of patients with MEN1 and ZES, 0% to 66% of patients with a duodenal gastrinoma and MEN1, 6,11,21,51,54 and 10% to 20% of patients with MEN1 and a pancreatic PET. 6,11,21,53 Our results show that the percentage of patients with duodenal or pancreatic tumor and lymph node metastases is similar in patients with ZES with MEN1 or without MEN1. 28,55,56 These results suggest that duodenal gastrinomas and pancreatic PETs in patients with MEN1 and ZES are malignant in the majority of cases. Studies in patients with sporadic ZES show a similar result; however, pancreatic tumors were much more likely to be associated with liver metastases. 28,55

We did not have sufficient patients with hepatic metastases, nor did we routinely explore all patients with diffuse liver metastases to clearly establish the primary tumor location, to be able to provide evidence as to the relative abilities of the PETs in the duodenum and pancreas to metastasize to liver.

Most of our patients (68%) had multiple primary tumors (mean, 4 PETs). However, as might be expected because of the selection criterion on the basis of positive results on preoperative imaging, multiple primaries were present in a higher percentage of patients with advanced disease (90% vs. 40%). These results show that even with detailed preoperative imaging using four different modalities (CT, MRI, ultrasound, angiography), the number of primary tumors that will be found at exploration is underestimated by preoperative localization studies. Previous studies in patients with sporadic ZES show that the ability of CT or MRI to detect a PET is size-dependent. 16,30 Our result suggests that even a combination of all conventional modalities does not overcome this limitation. These findings support the proposal that all of these patients, regardless of imaging studies, should undergo a thorough examination of both the pancreas and duodenum, with lymph nodes routinely removed.

Our surgical results show that even in patients with advanced disease (i.e., multiple primaries or tumors 6 cm or larger) with MEN1 and ZES, the tumors can be surgically removed with an acceptable complication rate and no deaths. However, long-term cure of ZES (5 years or more) is rarely seen with the typical operation now widely used (enucleation of proximal pancreatic PETs, resection of distal pancreatic PETs, duodenotomy) in patients with advanced or limited disease. These conclusions are supported by several findings in our study. First, our early (26%) and late (10%) complication rates were not significantly different between patients with limited disease or more advanced disease. Further, the complication rates for our patients with advanced disease (group 2B) were well within the range of 18% to 48% reported in other surgical studies of patients with MEN1 with PETs. 10,11,21,57,58 Second, none of the 48 patients in either surgical group had long-term cure of ZES (5 years or more). This result is consistent with almost all studies in the literature, with 0% to 5% of patients with MEN1 and ZES rendered disease-free. 11,19,21–24,59 The results in this study suggest that this low disease-free rate is likely due in most patients to the multiplicity of the duodenal gastrinomas as well as their high rate of metastases to lymph nodes. 11,21,52 The proposed paramount importance of multiple duodenal gastrinomas and their lymph node metastases to the low disease-free rate is supported by series that report patients with MEN1 and ZES can be cured by pancreaticoduodenotomy. 11,60,61

The best operation for patients with MEN1 with ZES or asymptomatic PETs is controversial and is not resolved by the present study. As noted above, the standard operation generally recommended and used in the present study (proximal pancreatic PET enucleation, distal resection, duodenotomy) will not cure ZES. However, as shown by our results, despite lack of a cure of ZES, the long-term survival rate with this approach was excellent. Our results indicate 100% survival 10 years after surgery for both surgical groups and 15-year survival rates of 100% for group 2A and 89% for group 2B, which were not significantly different. These survival rates compare favorably with the results from other studies in patients with MEN1 with PETs with or without ZES. In one study, 19 the 10-year survival rate after surgery in patients with ZES with lymph node metastases without liver metastases was 67%; in two other studies in patients without liver metastases with ZES, the 10-year survival rates after resection were 80%21 and 90%. 6 Previous studies in patients with MEN1 or without MEN1 with PETs show that the size 6,28,55,62 and extent 19,55,62 of the tumors were important predictors of the development of liver metastases, the primary determinant of long-term survival or of survival itself. 16,19,28,55,62 However, with the surgical approach used here, we obtained the same survival rate in patients with advanced disease as in patients with less extensive disease who underwent surgery, or as patients with small PETs who did not undergo surgery. These results, coupled with no increase in the surgical complication rate and no deaths, suggest that this standard operation is likely to be of benefit in patients with advanced disease as defined in this study (two ore more extrahepatic lesions or PETs 6 cm or larger). In regard to the question of pancreaticoduodenectomy, the overall 15-year survival rate of all surgical patients after resection was 92%; the rate for patients with small lesions (<2.5 cm on imaging) who did not undergo surgery was 100%. There are, however, occasional patients in whom the PET pursues a relatively aggressive course. Unfortunately, at present the tumor course in a given patient is unpredictable. Until prognostic factors in the natural history are better defined, it would seem reasonable to reserve pancreaticoduodenotomy for young patients with MEN1 who have extensive disease in the pancreatic head, or the occasional patient who has rapid tumor growth or progression as assessed by SRS, conventional imaging studies, and endoscopic ultrasound. Lastly, some 10,11,54 have proposed that a routine distal pancreatectomy be performed in all patients with MEN1 with PETs undergoing surgical exploration. This procedure increases the possibility of glucose intolerance developing, increases the complication rate, and greatly reduces the possibility of subsequently performing a pancreaticoduodenectomy. In our study we obtained excellent results, with a 92% 15-year survival rate, and only 6% of all patients required repeat PET surgery during a 7-year follow-up, performing a distal pancreatectomy only when large or multiple PETs were present in the pancreatic body/tail (50% of patients). Therefore, we recommend that distal pancreatectomy not be routinely performed.

Discussion

Dr. Samuel A. Wells (Durham, North Carolina): Dr. Norton and his colleagues have the most carefully studied and largest group of these patients currently available today.

The group of patients presented today represent the patient who presents clinically, and once identified will fall into one of the four categories mentioned by Dr. Norton.

Of greater interest, I think, are a progressively increasing group of patients who have genetically evident disease which might not be manifested clinically. I would like to know how you plan to follow these patients. Theoretically one could identify these patients before they move into the group 1 category.

What type of interventional therapy do you recommend? Few would argue for total pancreatic resection in these patients because the cure would be worse than the disease. At what stage do you advocate intervention in this group? How often should they be tested? Do you depend on a certain tumor size before recommending surgery? I know that your group has previously focused on 3 centimeters or the size at which surgical intervention is advised. But it is going to be a very important clinical question posed by patients with these and other heredity solid tumors.

Presenter Dr. Jeffrey A. Norton (San Francisco, California): Thank you, Dr. Wells. I think that based on our data demonstrated here, that the prognosis of these patients is outstanding. And I do not believe that even though they might have genetically evident disease that this would warrant aggressive surgery, for example, like we do in the patients with MEN-2-A and medullary thyroid carcinoma. So I would favor following them closely for imageable disease.

I think alternatively, some may recommend trying to do surgery to cure these patients based on duodenal exploration, as Dr. Thompson has mentioned previously. But I think our results also demonstrate that that is not necessarily the case in these patients, because our disease-free survival is essentially zero with long-term follow-up. I am not sure that we can cure these patients, but I think they can live for long periods of time with their disease. So I am not sure that aggressive surgical intervention is indicated unless they have imageable tumor. The goal is to try to prevent the development of liver metastases, which has always been the rate limiting step on survival for these patients.

DR. NORMAN W. THOMPSON (Ann Arbor, Michigan): I would like to congratulate you and your former colleagues at the NIH for your continuing contributions with this large series of MEN-1-ZES patients. These are really quite rare and there are very few series of any size. As you mentioned, their treatment is controversial. You brought up a number of controversial points in your presentation.

We might start with preoperative tumor localization. With the information you have now obtained and your corresponding findings at operation, what localization studies in these patients do you recommend? Obviously you are not identifying the small duodenal tumors preoperatively. Do you think it is necessary to rule out liver metastases before deciding for or against exploration?

Second, what are your current indications for operation? In your series, you arbitrarily eliminated what I think is the best group to potentially cure, those who have small tumors or tumors not imaged but known to be present because of biochemical evidence of the disease. I thought I heard you say you didn’t think that those patients should be operated on. We consider the chances of curing that group is the highest.

Finally, I would like to emphasize that overall this is a ‘good news-bad news‘ paper. You have shown that five-year survival is 100%, even though the biochemical cure is zero in five years. Our approach has been different in that we have operated on that first group, group 1, in addition to those with more advanced disease. We have just reviewed our five-year so-called cure rate for patients explored since 1990 and the gastrins are normal in 32% of those patients.

I would point out that you had a high incidence of pancreatic tumors in contrast to those in the duodenum. Maybe you can explain that by many of your patients being explored before 1987 when duodenal gastrinomas were not as well appreciated. In some series, 100% of MEN-1-ZES patients have had duodenal tumors. I think your percentage in the duodenum has probably been much higher in recent years.

Finally, you found lymph node metastases in 60 to 70% of your patients. Were those from the pancreatic tumors or from the duodenal tumors? Nodal metastases are very common with even microduodenal gastrinomas but distinctly uncommon from pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors smaller than 5 cm in diameter. Obviously this requires immunohistochemical staining of all tumors and metastases to make this determination.

Dr. Jeffrey A. Norton: I think those are all excellent questions and points, and they are controversial and difficult to answer.

I think clearly the best localization study now is the octreoscan or somatostatin receptor scintigraphy. And that is probably the study of choice that we would recommend. We would also recommend a conventional imaging study like CT, which would actually help us delineate the size of the physical tumors.

The indication for surgery in this group of patients was to prolong survival. And I think that we have accomplished that based on our results. We did not do surgery for cure, as you have done. The group that has reported the greatest cures in the MEN-1 patients have been from The Netherlands and Europe, in whom they have done Whipple pancreaticoduodenectomy. So I think if you really wanted to cure these patients that a Whipple procedure would be the procedure of choice, in my opinion. However, because the survival is so excellent, I am not convinced the Whipple is indicated in this group of patients.

We did find duodenal tumors. And I should point out that duodenal tumors were the most common site for gastrinomas. When we did SRS scanning, it was most commonly in the duodenum. The lymph node metastases were difficult to sort out. I think the duodenal tumors have a high incidence of lymph node metastases, as you have pointed out, the pancreatic tumors more commonly metastasize to the liver. It is important to not miss pancreatic tumors, because they may be associated with a decreased survival.

Dr. James C. Thompson: Thank you, Dr. Norton. I believe that everyone here should realize that when you deal with rare diseases, you are apt to make mistaken conclusions from feeling only one of the many appendages of an elephant. What you and Bob Jensen and the people at the NIH have done is to accumulate and systemize our knowledge of patients with this rare disease and have made available information, such as in this paper, that can’t be found anywhere else.

I think you have shown once again that death is due to hepatic metastases. I wonder, what was the death rate in a given patient or in a series of patients with liver metastases? What was the mean survival of patients with liver metastases? Since no patients were cured, is there ever any indication for performing a Whipple resection? Were there ulcer symptoms in patients in group 1? What is the life history of group 1 patients? Did none of their tumors advance? And how were they managed before Omeprazole? And just for the information of those who keep track of these patients, did all of them have hyperparathyroidism?

Bert Dunphy once made the dark observation that there were more people living off of cancer than dying from it. That is not true, of course, but it may be true in a disease such as ZES associated with the MEN-1 syndrome.

Dr. Jeffrey A. Norton: Thank you very much, Dr. Thompson. I think you are right that the liver metastases are the right limiting step on survival. The survival of these patients with MEN-1 and liver metastases was 40% at 20 years.

I agree a Whipple resection is not indicated unless they clearly have locally very advanced disease. We used H-2 receptor antagonists, as you know, prior to proton pump inhibitors, and have had no difficulty managing acid secretion.

The hyperparathyroidism is an interesting point. That usually occurs first. We have had patients who presented with ZES and then approximately ten years later have developed hyperparathyroidism. But the typical presentation is for the hyperparathyroidism prior to ZES.

Dr. Stanley R. Friesen (Prairie Village, Kansas): Thank you for the opportunity to comment on this important report of a long-term study of this genetic abnormality.

I have just a brief comment and a question. My question is, would you enlarge on the matter of reoperation for the subsequent development of resectable tumors in your patients?

Of historical interest, before there were pharmacologic inhibitors of gastric acid secretion, total gastrectomy seemed the only choice for the elimination of the strong ulcer disease in these patients with gastrinomas. Some of our patients, early on, also exhibited normal serum gastrin values postoperatively with negative secretin stimulation tests. I want to put on record that we have since discovered that those good results were due to the serendipitous removal of occult primary duodenal gastrinomas which were found microscopically in the surgical specimens.

Dr. Jeffrey A. Norton: Thank you, Dr. Friesen. Yes, the disease-free survival was primarily based on gastrin levels and stimulation tests. So it was biochemical and not imaging evidence of disease. But when patients did develop imageable evidence of recurrent disease, we did reoperate. And the reoperation rate is approximately 20%.

Footnotes

Presented at the 121st Annual Meeting of the American Surgical Association, April 26–28, 2001, the Broadmoor Hotel, Colorado Springs, Colorado

Correspondence: Jeffrey A. Norton, MD, Department of Veterans Affairs, Surgical Service (112) Bldg. 200, 3d Fl., Rm. 3B-135, 4150 Clement St., San Francisco, CA 94121-1598.

Accepted for publication April 26, 2001.

References

- 1.Norton JA, Jensen RT. Multiple endocrine neoplasia. In: DeVita VT, Hellman S, Rosenberg SA, eds. Cancer: principles and practice of oncology. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 1997: 1723–1729.

- 2.Marx SJ, Agarwal SK, Kester MB, et al. Multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1: clinical and genetic features of the hereditary endocrine neoplasias. Recent Prog Horm Res 1999; 54: 397–439. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Trump D, Farren B, Wooding C, et al. Clinical studies of multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN1). Q J Med 1996; 89: 653–669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Majewski JT, Wilson SD. The MEN-I syndrome: an all or none phenomenon? Surgery 1979; 86: 475–484. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Doherty GM, Olson JA, Frisella MM, et al. Lethality of multiple endocrine neoplasia type I. World J Surg 1998; 22: 581–587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cadiot G, Vuagnat A, Doukhan I, et al. Prognostic factors in patients with Zollinger-Ellison syndrome and multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1. Gastroenterology 1999; 116: 286–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wilkinson S, Teh BT, Davey KR, et al. Cause of death in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1. Arch Surg 1993; 128: 683–690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dean PG, vanHeerden JA, Farley DR, et al. Are patients with multiple endocrine neoplasia type I prone to premature death? World J Surg 2000; 24: 1437–1441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jensen RT. Management of the Zollinger-Ellison syndrome in patients with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1. J Intern Med 1998; 243: 477–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Skogseid B, Oberg K, Eriksson B, et al. Surgery for asymptomatic pancreatic lesion in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1. World J Surg 1996; 20: 872–877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bartsch DK, Langer P, Wild A, et al. Pancreaticoduodenal endocrine tumors in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1: surgery or surveillance? Surgery 2000; 128: 958–966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Norton JA, Fraker DL, Alexander HR, et al. Surgery to cure the Zollinger-Ellison syndrome. N Engl J Med 1999; 341: 635–644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Metz DC, Jensen RT, Bale AE, et al. Multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1: clinical features and management. In: Bilezekian JP, Levine MA, Marcus R, eds. The parathyroids. New York: Raven; 1994: 591–646.

- 14.Jensen RT. Use of omeprazole and other proton pump inhibitors in the Zollinger-Ellison syndrome. In: Olbe L, ed. Milestones in drug therapy. Basel, Switzerland: Birkhauser Verlag AG; 1999: 205–221.

- 15.Jensen RT. Zollinger-Ellison syndrome. In: Doherty GM, Skogseid B, eds. Surgical endocrinology: clinical syndromes. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2001: 291–344.

- 16.Jensen RT, Gardner JD. Gastrinoma. In: Go VLW, DiMagno EP, Gardner JD, et al, eds. The pancreas: biology, pathobiology and disease. New York: Raven; 1993: 931–978.

- 17.Thompson NW, Lloyd RV, Nishiyama RH, et al. MEN I pancreas: a histological and immunohistochemical study. World J Surg 1984; 8: 561–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thompson NW. Current concepts in the surgical management of multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 pancreatic-duodenal disease. Results in the treatment of 40 patients with Zollinger-Ellison syndrome, hypoglycaemia or both. J Intern Med 1998; 243: 495–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Melvin WS, Johnson JA, Sparks J, et al. Long-term prognosis of Zollinger-Ellison syndrome in multiple endocrine neoplasia. Surgery 1993; 114: 1183–1188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mignon M, Cadiot G. Diagnostic and therapeutic criteria in patients with Zollinger-Ellison syndrome and multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1. J Intern Med 1998; 243: 489–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grama D, Skogseid B, Wilander E, et al. Pancreatic tumors in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1: clinical presentation and surgical treatment. World J Surg 1992; 16: 611–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Farley DR, Van Heerden JA, Grant CS, et al. The Zollinger-Ellison syndrome. A collective surgical experience. Ann Surg 1992; 215: 561–569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sheppard BC, Norton JA, Doppman JL, et al. Management of islet cell tumors in patients with multiple endocrine neoplasia: a prospective study. Surgery 1989; 106: 1108–1117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thompson JC, Lewis BG, Wiener I, Townsend CM Jr. The role of surgery in the Zollinger-Ellison syndrome. Ann Surg 1983; 197: 594–607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fishbeyn VA, Norton JA, Benya RV, et al. Assessment and prediction of long-term cure in patients with Zollinger-Ellison syndrome: the best approach. Ann Intern Med 1993; 119: 199–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Benya RV, Metz DC, Venzon DJ, et al. Zollinger-Ellison syndrome can be the initial endocrine manifestation in patients with multiple endocrine neoplasia-type 1. Am J Med 1994; 97: 436–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roy P, Venzon DJ, Shojamanesh H, et al. Zollinger-Ellison syndrome: clinical presentation in 261 patients. Medicine 2000; 79: 379–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weber HC, Venzon DJ, Lin JT, et al. Determinants of metastatic rate and survival in patients with Zollinger-Ellison syndrome: a prospective long-term study. Gastroenterology 1995; 108: 1637–1649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Metz DC, Pisegna JR, Fishbeyn VA, et al. Control of gastric acid hypersecretion in the management of patients with Zollinger-Ellison syndrome. World J Surg 1993; 17: 468–480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Orbuch M, Doppman JL, Strader DB, et al. Imaging for pancreatic endocrine tumor localization: recent advances. In: Mignon M, Jensen RT, eds. Endocrine tumors of the pancreas: recent advances in research and management. Series: Frontiers of Gastrointestinal Research. Basel, Switzerland: S. Karger; 1995:268–281.

- 31.Sugg SL, Norton JA, Fraker DL, et al. A prospective study of intraoperative methods to diagnose and resect duodenal gastrinomas. Ann Surg 1993; 218: 138–144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alexander HR, Fraker DL, Norton JA, et al. Prospective study of somatostatin receptor scintigraphy and its effect on operative outcome in patients with Zollinger-Ellison syndrome. Ann Surg 1998; 228: 228–238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Termanini B, Gibril F, Doppman JL, et al. Distinguishing small hepatic hemangiomas from vascular liver metastases in patients with gastrinoma: use of a somatostatin-receptor scintigraphic agent. Radiology 1997; 202: 151–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gibril F, Reynolds JC, Doppman JL, et al. Somatostatin receptor scintigraphy: its sensitivity compared with that of other imaging methods in detecting primary and metastatic gastrinomas: a prospective study. Ann Intern Med 1996; 125: 26–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Termanini B, Gibril F, Reynolds JC, et al. Value of somatostatin receptor scintigraphy: a prospective study in gastrinoma of its effect on clinical management. Gastroenterology 1997; 112: 335–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Norton JA, Doppman JL, Jensen RT. Curative resection in Zollinger-Ellison syndrome: Results of a 10-year prospective study. Ann Surg 1992; 215: 8–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fraker DL, Norton JA, Alexander HR, et al. Surgery in Zollinger-Ellison syndrome alters the natural history of gastrinoma. Ann Surg 1994; 220: 320–330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Frucht H, Norton JA, London JF, et al. Detection of duodenal gastrinomas by operative endoscopic transillumination: a prospective study. Gastroenterology 1990; 99: 1622–1627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.MacFarlane MP, Fraker DL, Alexander HR, et al. A prospective study of surgical resection of duodenal and pancreatic gastrinomas in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1. Surgery 1995; 118: 973–980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Frucht H, Howard JM, Slaff JI, et al. Secretin and calcium provocative tests in the Zollinger-Ellison syndrome: a prospective study. Ann Intern Med 1989; 111: 713–722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kaplan EL, Meier P. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. J Am Stat Assoc 1958; 53: 457–481. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dotzenrath C, Goretzki PE, Cupisti K, et al. Malignant endocrine tumors in patients with MEN1 disease. Surgery 2001; 129: 91–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Norton JA, Doherty GD, Fraker DL, et al. Surgical treatment of localized gastrinoma within the liver: a prospective study. Surgery 1998; 124: 1145–1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Krenning EP, Kwekkeboom DJ, Bakker WH, et al. Somatostatin receptor scintigraphy with [111In-DTPA-D-Phe1]- and [123I-Tyr3]-octreotide: the Rotterdam experience with more than 1000 patients. Eur J Nucl Med 1993; 20: 716–731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jensen RT. Peptide therapy. Recent advances in the use of somatostatin and other peptide receptor agonists and antagonists. In: Lewis JH, Dubois A, eds. Current clinical topics in gastrointestinal pharmacology. Malden, MA: Blackwell Science; 1997: 144–223.

- 46.Gibril F, Reynolds JC, Chen CC, et al. Specificity of somatostatin receptor scintigraphy: a prospective study and the effects of false-positive localizations on management in patients with gastrinomas. J Nucl Med 1999; 40: 539–553. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ruszniewski P, Podevin P, Cadiot G, et al. Clinical, anatomical, and evolutive features of patients with the Zollinger-Ellison syndrome combined with type I multiple endocrine neoplasia. Pancreas 1993; 8: 295–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thompson NW, Vinik AI, Eckhauser FE. Microgastrinomas of the duodenum. A cause of failed operations for the Zollinger-Ellison syndrome. Ann Surg 1989; 209: 396–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wu PC, Alexander HR, Bartlett DL, et al. A prospective analysis of the frequency, location, and curability of ectopic (non-pancreaticoduodenal, non-nodal) gastrinoma. Surgery 1997; 122: 1176–1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Arnold WS, Fraker DL, Alexander HR, et al. Apparent lymph node primary gastrinoma. Surgery 1994; 116: 1123–1130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Donow C, Pipeleers-Marichal M, Schroder S, et al. Surgical pathology of gastrinoma: site, size, multicentricity, association with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1, and malignancy. Cancer 1991; 68: 1329–1334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jordan PH Jr. A personal experience with pancreatic and duodenal neuroendocrine tumors. J Am Coll Surg 1999; 189: 470–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lowney JK, Frisella MM, Lairmore TC, Doherty GM. Pancreatic islet cell tumor metastasis in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1: correlation with primary tumor size. Surgery 1999; 125: 1043–1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Thompson NW. Multiple endocrine neoplasia type I. Surgical therapy. Cancer Treat Res 1997; 89: 407–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yu F, Venzon DJ, Serrano J, et al. Prospective study of the clinical course, prognostic factors and survival in patients with longstanding Zollinger-Ellison syndrome. J Clin Oncol 1999; 17: 615–630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Thom AK, Norton JA, Axiotis CA, Jensen RT. Location, incidence and malignant potential of duodenal gastrinomas. Surgery 1991; 110: 1086–1093. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hellman P, Andersson M, Rastad J, et al. Surgical strategy for large or malignant endocrine pancreatic tumors. World J Surg 2000; 24: 1353–1360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lairmore TC, Chen VY, DeBenedetti MK, et al. Duodenopancreatic resections in patients with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1. Ann Surg 2000; 231: 909–918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bonfils S, Landor JH, Mignon M, Hervoir P. Results of surgical management in 92 consecutive patients with Zollinger-Ellison syndrome. Ann Surg 1981; 194: 692–697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Stadil F. Treatment of gastrinomas with pancreaticoduodenectomy. In: Mignon M, Jensen RT, eds. Endocrine tumors of the pancreas: recent advances in research and management. Series: Frontiers in Gastrointestinal Research. Basel, Switzerland: S. Karger; 1995:333–341.

- 61.Delcore R, Friesen SR. Role of pancreatoduodenectomy in the management of primary duodenal wall gastrinomas in patients with Zollinger-Ellison syndrome. Surgery 1992; 112: 1016–1022. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Madeira I, Terris B, Voss M, et al. Prognostic factors in patients with endocrine tumours of the duodenopancreatic area. Gut 1998; 43: 422–427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]