Abstract

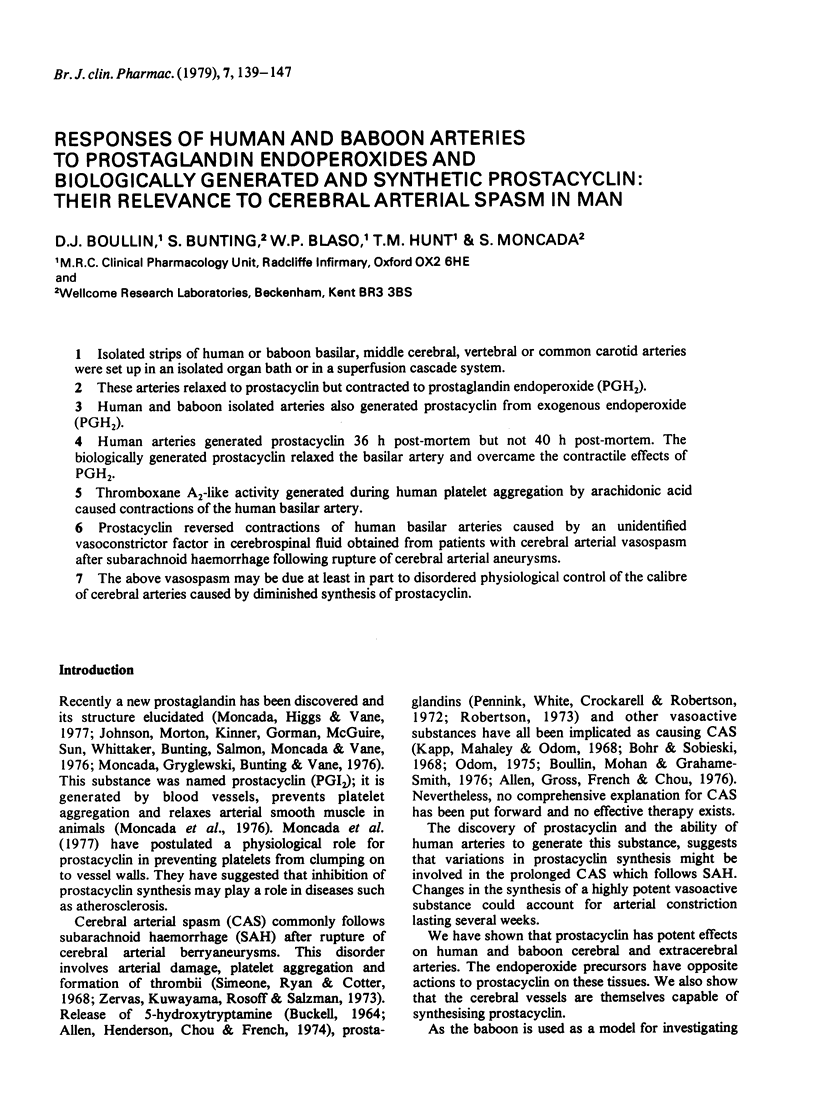

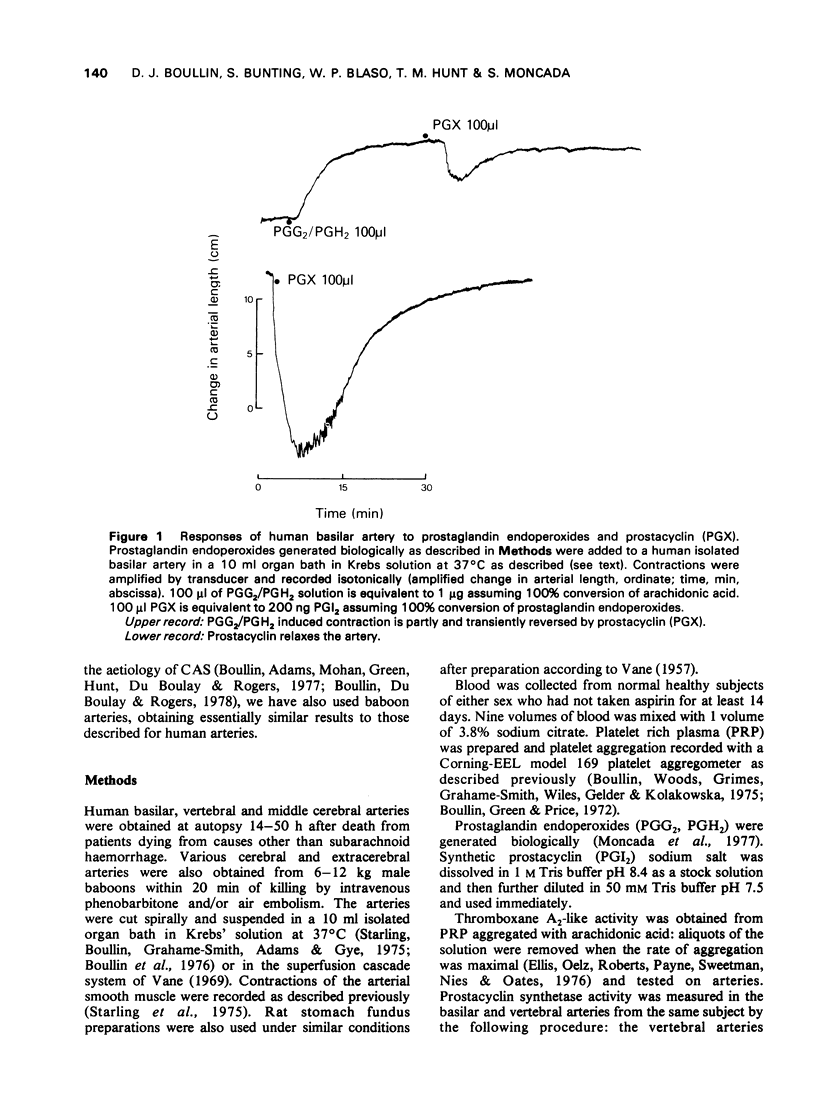

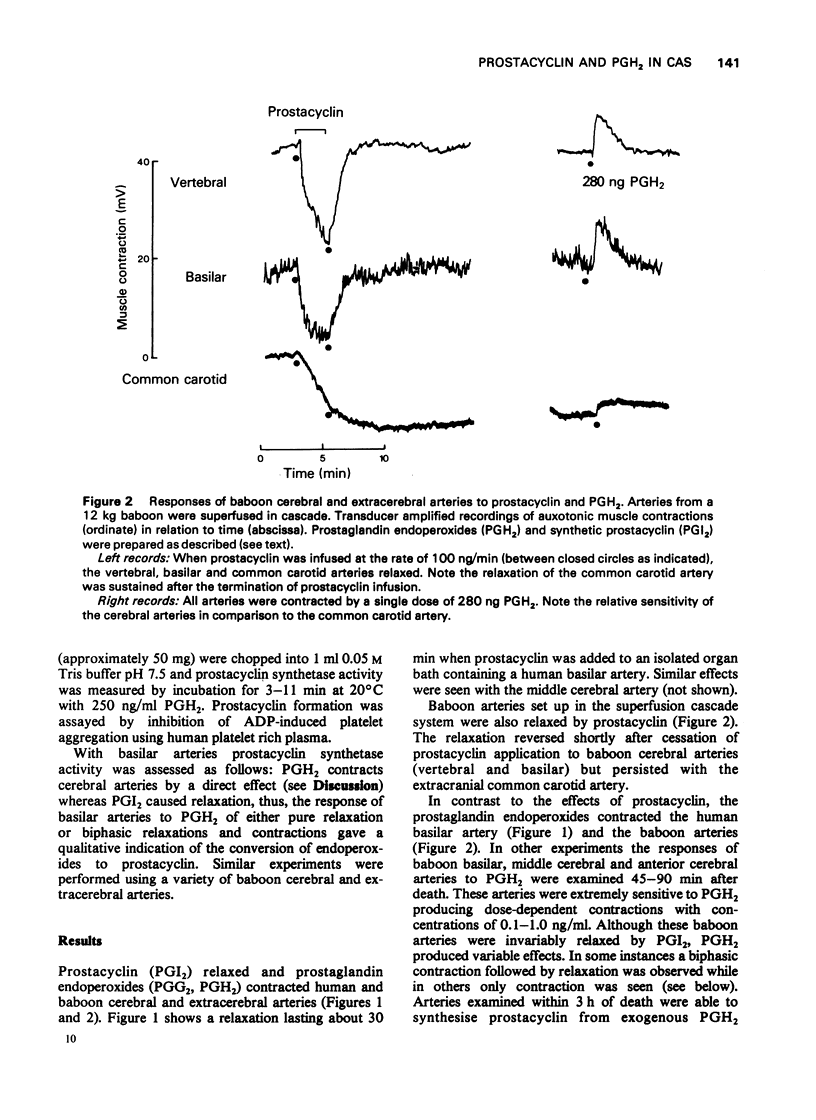

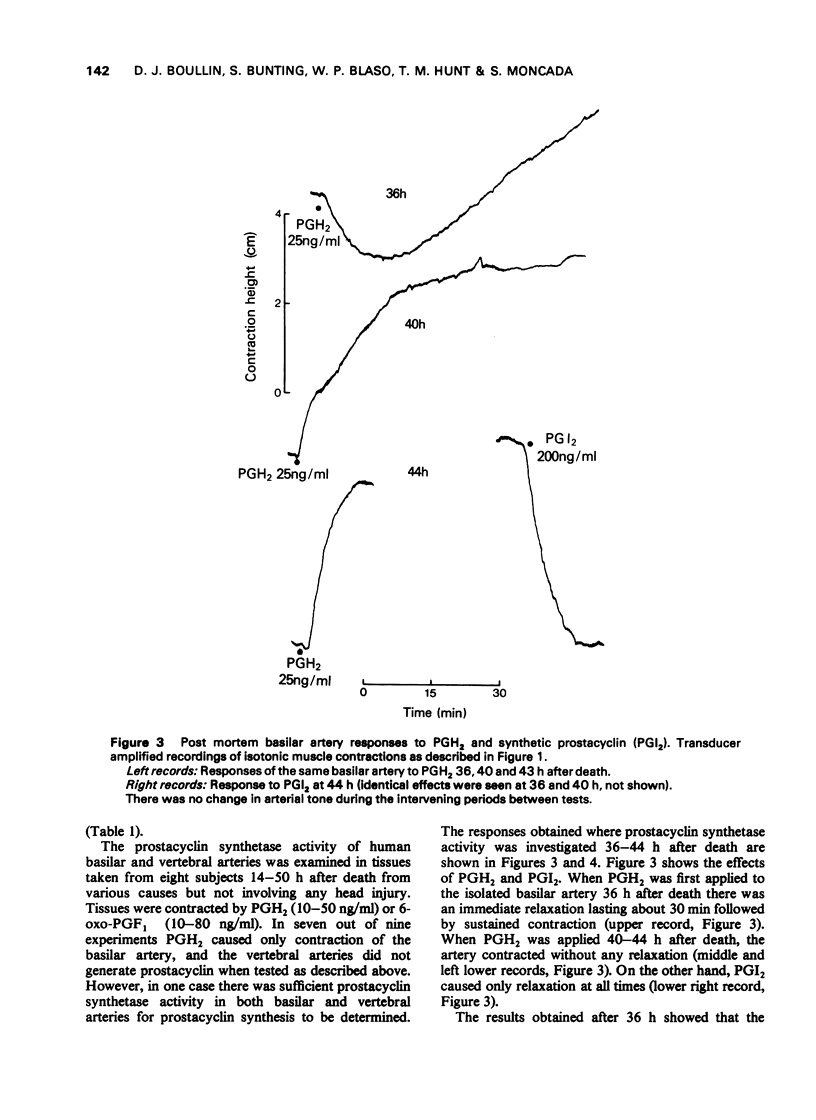

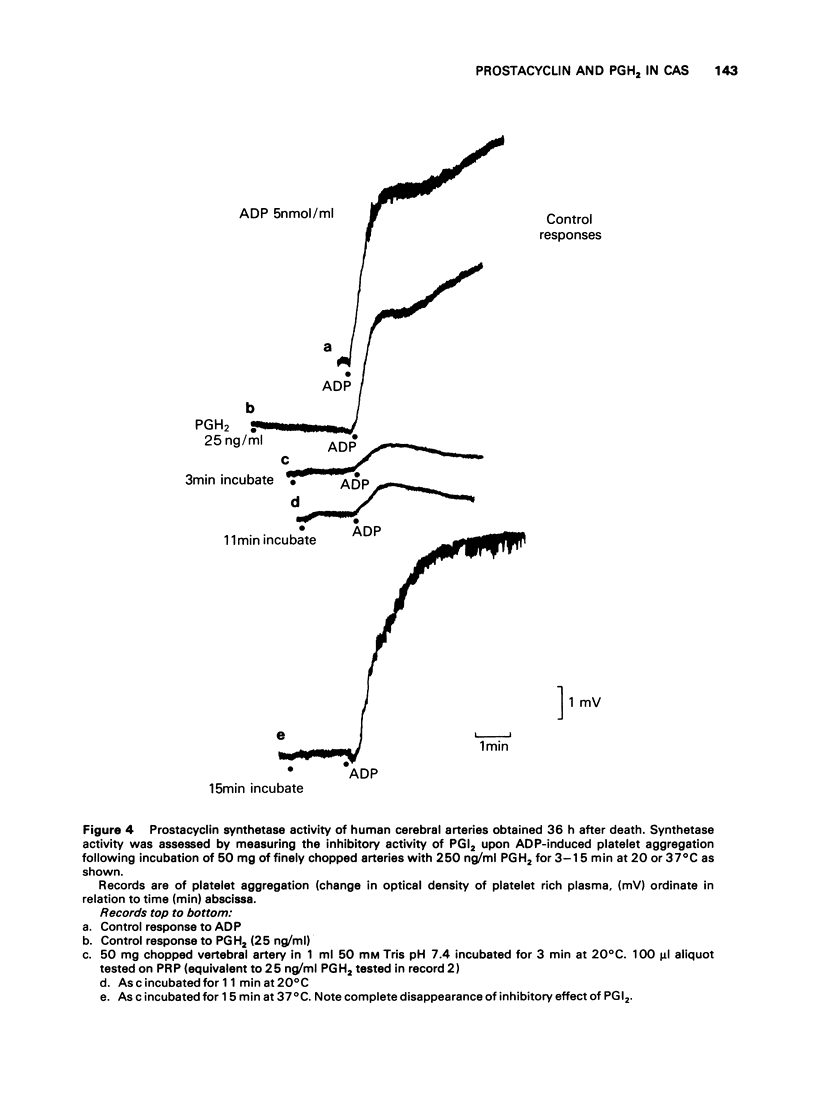

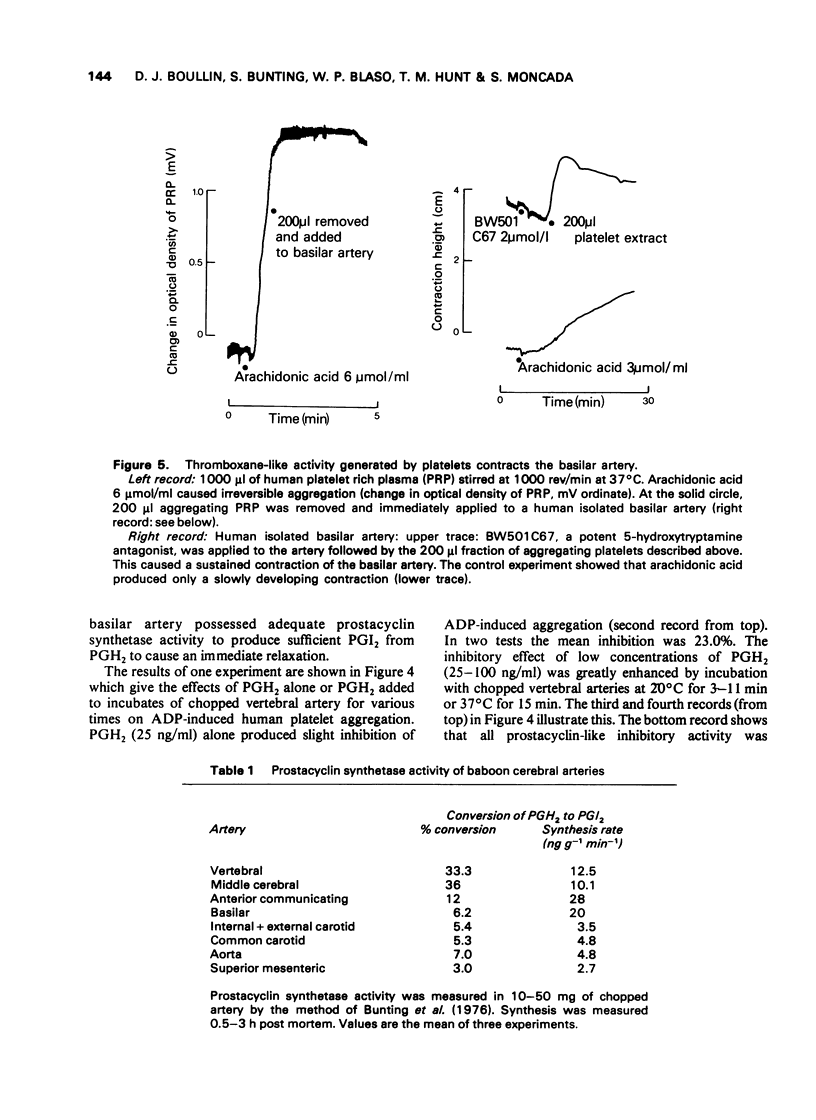

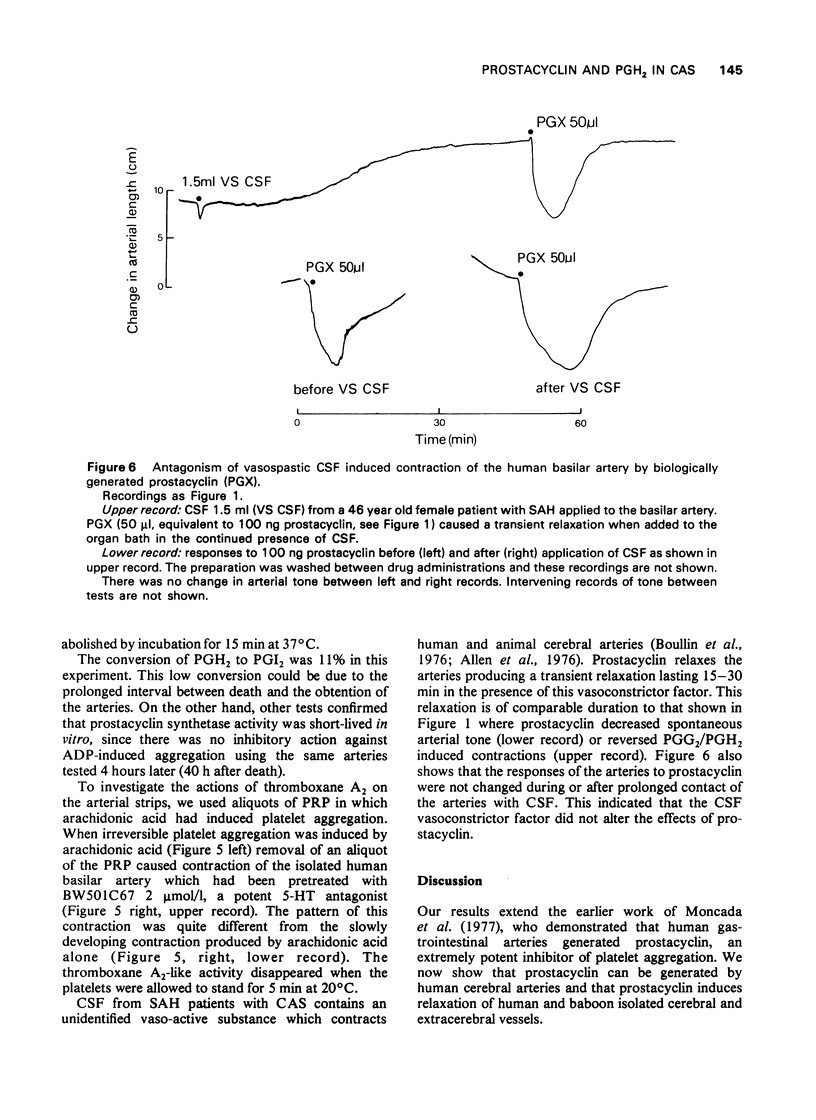

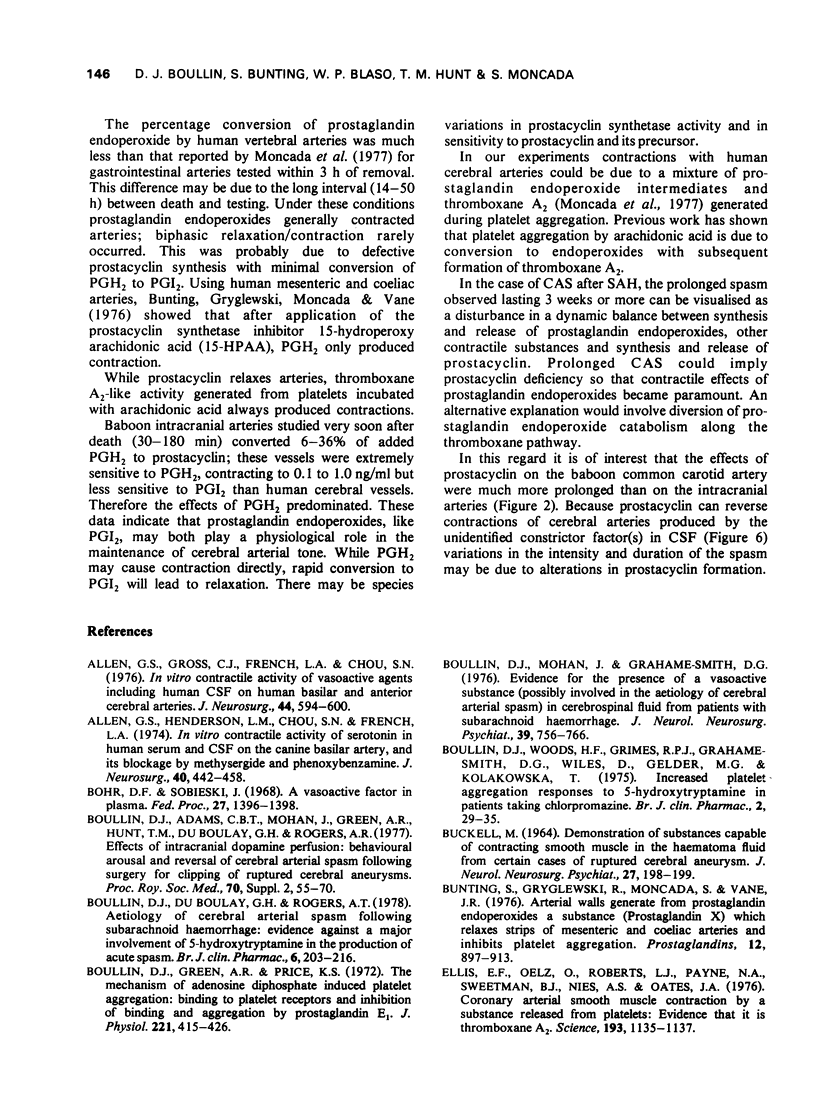

1 Isolated strips of human or baboon basilar, middle cerebral, vertebral or common carotid arteries were set up in an isolated organ bath or in a superfusion cascade system. 2 These arteries relaxed to prostacyclin but contracted to prostaglandin endoperoxide (PGH2). 3 Human and baboon isolated arteries also generated prostacyclin from exogenous endoperoxide (PGH2). 4 Human arteries generated prostacyclin 36 h post-mortem but not 40 h post-mortem. The biologically generated prostacyclin relaxed the basilar artery and overcame the contractile effects of PGH2. 5 Thromboxane A2-like activity generated during human platelet aggregation by arachidonic acid caused contractions of the human basilar artery. 6 Prostacyclin reversed contractions of human basilar arteries caused by an unidentified vasoconstrictor factor in cerebrospinal fluid obtained from patients with cerebral arterial vasospasm after subarachnoid haemorrhage following rupture of cerebral arterial aneurysms. 7. The above vasospasm may be due at least in part to disordered physiological control of the calibre of cerebral arteries caused by diminished synthesis of prostacyclin.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Allen G. S., Gross C. J., French L. A., Chou S. N. Cerebral arterial spasm. Part 5: in vitro contractile activity of vasoactive agents including human CSF on human basilar and anterior cerebral arteries. J Neurosurg. 1976 May;44(5):594–600. doi: 10.3171/jns.1976.44.5.0594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen G. S., Henderson L. M., Chou S. N., French L. A. Cerebral arterial spasm. 2. In vitro contractile activity of serotonin in human serum and CSF on the canine basilar artery, and its blockage by methylsergide and phenoxybenzamine. J Neurosurg. 1974 Apr;40(4):442–450. doi: 10.3171/jns.1974.40.4.0442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BUCKELL M. DEMONSTRATION OF SUBSTANCES CAPABLE OF CONTRACTING SMOOTH MUSCLE IN THE HAEMATOMA FLUID FROM CERTAIN CASES OF RUPTURED CEREBRAL ANEURYSM. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1964 Jun;27:198–199. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.27.3.198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohr D. F., Sobieski J. A vasoactive factor in plasma. Fed Proc. 1968 Nov-Dec;27(6):1396–1398. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boullin D. J., Adams C. B., Mohan J., Green A. R., Hunt T. M., du Boulay G. H., Rogers A. T. Effects of intracranial dopamine perfusion: behavioural arousal and reversal of cerebral arterial spasm following surgery for clipping of ruptured cerebral aneurysms. Proc R Soc Med. 1977;70 (Suppl 2):55–70. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boullin D. J., Du Boulay G. H., Rogers A. T. Aetiology of cerebral arterial spasm following subarachnoid haemorrhage: evidence against a major involvement of 5-hydroxy-tryptamine in the production of acute spasm. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1978 Sep;6(3):203–215. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1978.tb04586.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boullin D. J., Green A. R., Price K. S. The mechanism of adenosine diphosphate induced platelet aggregation: binding to platelet receptors and inhibition of binding and aggregation by prostaglandin E 1 . J Physiol. 1972 Mar;221(2):415–426. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1972.sp009758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boullin D. J., Mohan J., Grahame-Smith D. G. Evidence for the presence of a vasoactive substance (possibly involved in the aetiology of cerebral arterial spasm) in cerebrospinal fluid from patients with subarachnoid haemorrhage. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1976 Aug;39(8):756–766. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.39.8.756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunting S., Gryglewski R., Moncada S., Vane J. R. Arterial walls generate from prostaglandin endoperoxides a substance (prostaglandin X) which relaxes strips of mesenteric and coeliac ateries and inhibits platelet aggregation. Prostaglandins. 1976 Dec;12(6):897–913. doi: 10.1016/0090-6980(76)90125-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis E. F., Oelz O., Roberts L. J., 2nd, Payne N. A., Sweetman B. J., Nies A. S., Oates J. A. Coronary arterial smooth muscle contraction by a substance released from platelets: evidence that it is thromboxane A2. Science. 1976 Sep 17;193(4258):1135–1137. doi: 10.1126/science.959827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapp J., Mahaley M. S., Jr, Odom G. L. Cerebral arterial spasm. 3. Partial purification and characterization of a spasmogenic substance in feline platelets. J Neurosurg. 1968 Oct;29(4):350–356. doi: 10.3171/jns.1968.29.4.0350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moncada S., Gryglewski R., Bunting S., Vane J. R. An enzyme isolated from arteries transforms prostaglandin endoperoxides to an unstable substance that inhibits platelet aggregation. Nature. 1976 Oct 21;263(5579):663–665. doi: 10.1038/263663a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moncada S., Higgs E. A., Vane J. R. Human arterial and venous tissues generate prostacyclin (prostaglandin x), a potent inhibitor of platelet aggregation. Lancet. 1977 Jan 1;1(8001):18–20. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(77)91655-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odom G. L. Cerebral vasospasm. Clin Neurosurg. 1975;22:29–58. doi: 10.1093/neurosurgery/22.cn_suppl_1.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennink M., White R. P., Crockarell J. R., Robertson J. T. Role of prostaglandin F 2 in the genesis of experimental cerebral vasospasm. Angiographic study in dogs. J Neurosurg. 1972 Oct;37(4):398–406. doi: 10.3171/jns.1972.37.4.0398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson J. T. Cerebral arterial spasm: current concepts. Clin Neurosurg. 1974;21:100–106. doi: 10.1093/neurosurgery/21.cn_suppl_1.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simeone F. A., Ryan K. G., Cotter J. R. Prolonged experimental cerebral vasospasm. J Neurosurg. 1968 Oct;29(4):357–366. doi: 10.3171/jns.1968.29.4.0357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starling L. M., Boullin D. J., Grahame-Smith D. G., Adams C. B., Gye R. S. Responses of isolated human basilar arteries to 5-hydroxytryptamine, noradrenaline, serum, platelets, and erythrocytes. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1975 Jul;38(7):650–656. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.38.7.650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VANE J. R. A sensitive method for the assay of 5-hydroxytryptamine. Br J Pharmacol Chemother. 1957 Sep;12(3):344–349. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1957.tb00146.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vane J. R. The release and fate of vaso-active hormones in the circulation. Br J Pharmacol. 1969 Feb;35(2):209–242. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1969.tb07982.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whittaker N., Bunting S., Salmon J., Moncada S., Vane J. R., Johnson R. A., Morton D. R., Kinner J. H., Gorman R. R., McGuire J. C. The chemical structure of prostaglandin X (prostacyclin). Prostaglandins. 1976 Dec;12(6):915–928. doi: 10.1016/0090-6980(76)90126-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zervas N. T., Kuwayama A., Rosoff C. B., Salzman E. W. Cerebral arterial spasm. Modification by inhibition of platelet function. Arch Neurol. 1973 Jun;28(6):400–404. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1973.00490240060010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]