Abstract

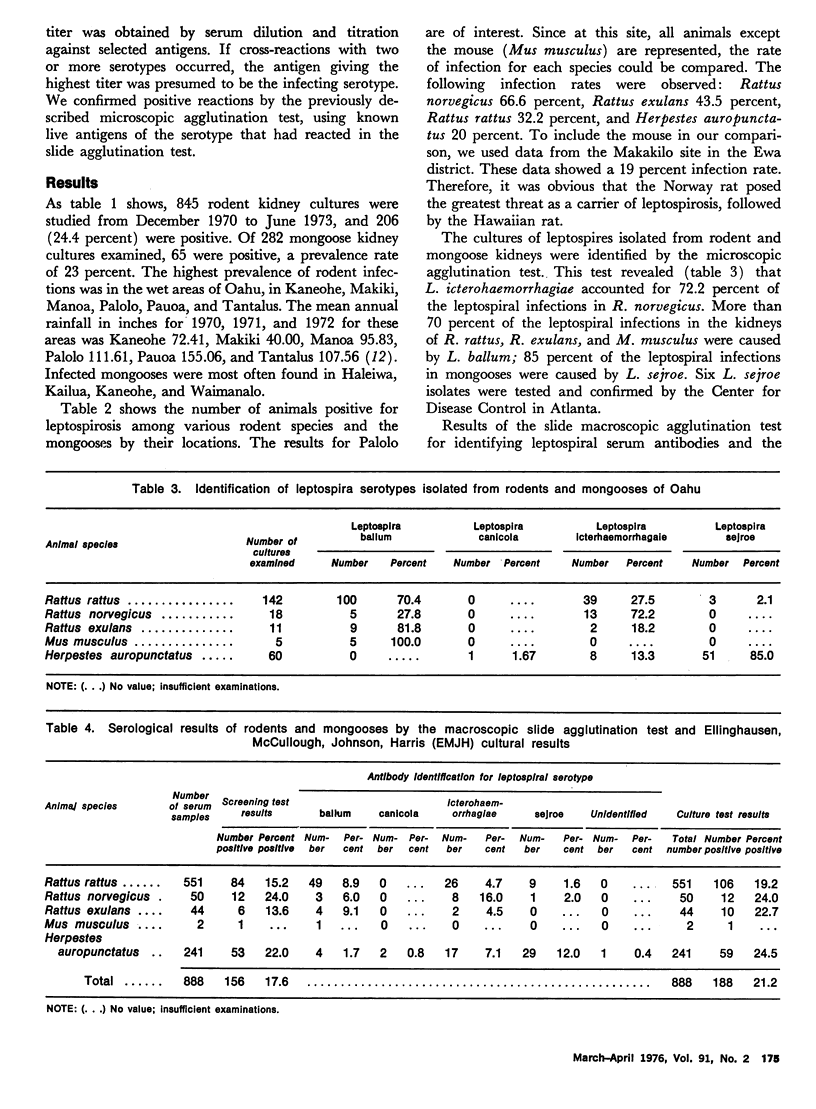

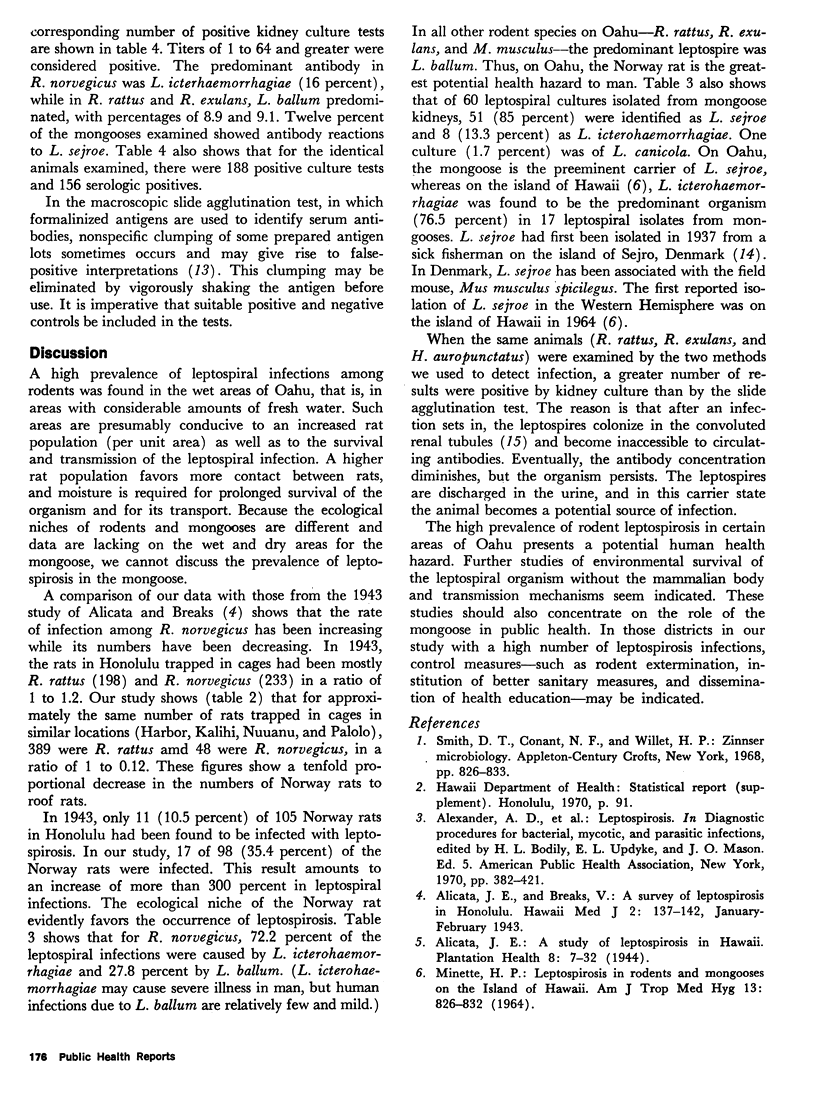

Sporadic occurrences of human leptospirosis in recent years throughout the State of Hawaii have resulted in at least one death. Because of the apparent association of rodents and possibly mongooses with human leptospiral infections, a survey for leptospirosis was conducted among rodents as well as mongooses on Oahu. No such work had been recorded since a survey of rodents and mongooses for leptospirosis 31 years ago. In the current work, the prevalence of rodent and mongoose leptospirosis in the districts of Oahu was determined by the kidney-culture method. A serologic study of the rodents and mongooses subjected to kidney culturing was also conducted by use of the microscopic slide agglutination test. There were 1.2 times as many kidney culture results that were positive as serologic results. High prevalence of rodent leptospirosis were found where there was considerable rainfall or fresh surface water such as from streams. The overall leptospirosis prevalence for rodents was 23.4 percent, and for mongooses it was 23.0 percent. The Norway rat (Rattus norvegicus) had the highest infection rate, 33.3 percent, and the predominant (72.2 percent) organism in these infections was Leptospira icterohaemorrhagiae, which causes Weil's disease in man. Observations of rodent leptospirosis recorded 31 years ago were compared with results of the current study. The mongoose (Herpestes auropunctatus) is the preeminent carrier of Leptospira sejroe, a serotype that generally causes a mild form of leptospirosis in man.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Abdussalam M., Alexander A. D., Babudieri B., Bögel K., Borg-Petersen C., Faine S., Kmety E., Lataste-Dorolle C., Turner L. H. Research needs in leptospirosis. Bull World Health Organ. 1972;47(1):113–122. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BABUDIERI B. Animal reservoirs of leptospires. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1958 Jun 3;70(3):393–413. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1958.tb35398.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ELLINGHAUSEN H. C., Jr, MCCULLOUGH W. G. NUTRITION OF LEPTOSPIRA POMONA AND GROWTH OF 13 OTHER SEROTYPES: A SERUM-FREE MEDIUM EMPLOYING OLEIC ALBUMIN COMPLEX. Am J Vet Res. 1965 Jan;26:39–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JOHNSON R. C., ROGERS P. 5-FLUOROURACIL AS A SELECTIVE AGENT FOR GROWTH OF LEPTOSPIRAE. J Bacteriol. 1964 Feb;87:422–426. doi: 10.1128/jb.87.2.422-426.1964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson R. C., Harris V. G. Differentiation of pathogenic and saprophytic letospires. I. Growth at low temperatures. J Bacteriol. 1967 Jul;94(1):27–31. doi: 10.1128/jb.94.1.27-31.1967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MINETTE H. P. LEPTOSPIROSIS IN RODENTS AND MONGOOSES ON THE ISLAND OF HAWAII. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1964 Nov;13:826–832. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1964.13.826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]