Abstract

Background

Socio-economic variations in health, including variations in health according to wealth and income, have been widely reported. A potential method of improving the health of the most deprived groups is to increase their income. State funded welfare programmes of financial benefits and benefits in kind are common in developed countries. However, there is evidence of widespread under claiming of welfare benefits by those eligible for them. One method of exploring the health effects of income supplementation is, therefore, to measure the health effects of welfare benefit maximisation programmes. We conducted a systematic review of the health, social and financial impacts of welfare rights advice delivered in healthcare settings.

Methods

Published and unpublished literature was accessed through searches of electronic databases, websites and an internet search engine; hand searches of journals; suggestions from experts; and reference lists of relevant publications. Data on the intervention delivered, evaluation performed, and outcome data on health, social and economic measures were abstracted and assessed by pairs of independent reviewers. Results are reported in narrative form.

Results

55 studies were included in the review. Only seven studies included a comparison or control group. There was evidence that welfare rights advice delivered in healthcare settings results in financial benefits. There was little evidence that the advice resulted in measurable health or social benefits. This is primarily due to lack of good quality evidence, rather than evidence of an absence of effect.

Conclusion

There are good theoretical reasons why income supplementation should improve health, but currently little evidence of adequate robustness and quality to indicate that the impact goes beyond increasing income.

Background

Socio-economic variations in health, including variations in health according to wealth and income, have been widely reported [1-4]. However, interventions to overcome socio-economic variations in health have achieved little success[5,6]. One potential method of improving the health of the most deprived groups is to increase their income. Despite a number of income supplementation experiments – particularly in the USA in the 1960s and 1970s – little investigation of the impact of these experiments on health has been performed[7].

State funded welfare programmes of financial benefits and benefits in kind for, amongst others, the unemployed, the elderly and the sick are common in developed countries. However, there is evidence of widespread under claiming of welfare benefits by those eligible for them, with take up of income related benefits in the UK around 80% in 2002[8]. Take up rates in the rest of Europe are around 40–80% with generally lower rates in the USA[9]. One method of exploring the health effects of income supplementation is, therefore, to measure the health effects of welfare benefit maximisation programmes[7].

Efforts to provide advice on claiming welfare benefits are increasingly being made in the UK[10]. In general, 'welfare rights advice' involves review of eligibility for welfare benefits and active assistance with claims for any benefits to which the client is found to be entitled. Active assistance includes help with completing forms, telephone calls, obtaining letters of support and references, and attendance in person at benefit tribunals. Welfare rights advisors are also often able to offer debt counselling and legal advice, or refer to other appropriate agencies. In the UK, where the majority of welfare rights advice programmes are based, advice is primarily offered through local government, Citizens Advice Bureaux (CAB – a voluntary organisation that "helps people resolve their legal, money and other problems by providing free information and advice"[11] from community locations) or primary care, with clients accessing the services either through self referral, referral from another agency, or a combination of both.

Welfare rights advice services delivered at, or through, primary care premises work within a holistic model of primary health care that "involves continuity of care, health promotion and education, integration of prevention with sick care, a concern for population as well as individual health, community involvement and the use of appropriate technology"[12]. In the UK, all individuals who have been legally resident for at least six months are entitled to be registered with a local primary care practice and receive free treatment there. As over 98% of the population is registered with a primary care practice[13], primary care provides a setting in which the great majority of the population can be accessed.

Given the increasing interest in this area, particularly in the UK, the funding that is now being committed to it by primary care organisations and local authorities, and the opportunity it offers to assess the impact of income supplementation on health, it is timely to bring together the available evidence on the impacts of welfare rights advice delivered in healthcare settings. Two previous reviews have focused on welfare rights advice in healthcare settings[14,15]. However, neither of these took a systematic approach to literature searching and were primarily descriptions of the different programmes on offer, rather than an assessment of the impacts of these.

We performed a systematic review in order to answer the question: what are the health, social and financial impacts of welfare rights advice delivered in healthcare settings?

Methods

Search strategy

The following strategies were used (by JA) to find and access potentially relevant studies for consideration for inclusion in the review:

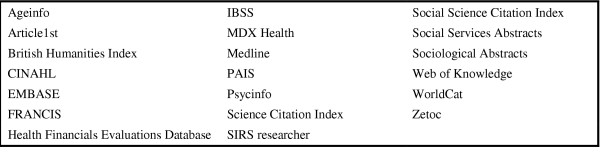

1. Searches of electronic databases: the keyword search "(welfare OR benefit OR social welfare OR citizen OR money OR assistance) AND (advice OR right OR prescrip$ OR counsel$)" was used to search the electronic databases listed in Box 1 (see Figure 1) (where $ = wildcard symbol). All available years of all databases were searched up to and including October 2004.

Figure 1.

Box 1. Electronic databases searched.

2. Hand searches of specific journals: the electronic contents pages of Health and Social Care in the Community (volumes 6–12, 1998–2004), and the Journal of Social Policy (volumes 26–33, 1997–2004) were scanned to identify relevant publications[16]. These journals were chosen because of their relevance to the subject area and the perception that substantial relevant work had been published in them.

3. Searches of internet search engine: searches were made of the internet search engine Google http://www.google.com using the same strategies as above. The first 100 results returned by each search strategy were scanned for relevance and those judged to be potentially relevant followed up.

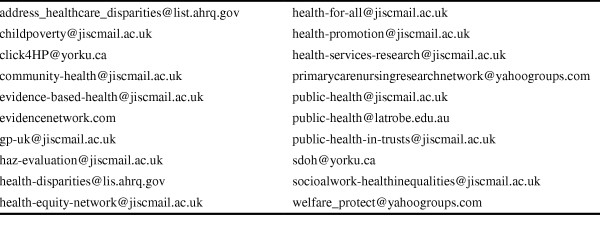

4. Suggestions from experts and those working in the field: requests for help with accessing relevant literature were sent to relevant e-mail distribution lists (listed in Box 2 – see Figure 2), posted on the rightsnet.org.uk discussion forum and published in the 'trade magazines' Poverty and Welfare Rights Bulletin. 'Experts' – identified as such either by frequent publication in the area, or through personal contacts of the research team – were also contacted directly and asked for help with identifying relevant literature or providing further contacts[17].

Figure 2.

Box 2. Email distribution lists sent requests for information.

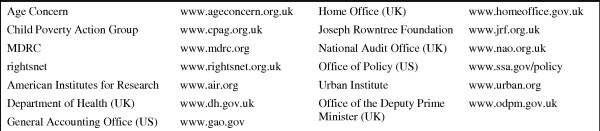

5. Searches of specific websites: the websites of a number of specific organisations that sponsor and conduct social policy research (listed in Box 3 – see Figure 3) were searched to identify publications of interest.

Figure 3.

Box 3. Websites hand searched for relevant publications.

6. Reference lists from relevant studies: the reference lists of all studies assessed to be relevant were scanned to identify other relevant work, as were the reference lists of previous reviews in this area[14,15].

7. Science Citation Index and Social Science Citation Index: citation searches of the Science Citation Index and Social Science Citation Index were performed to identify all citations of studies identified as relevant.

8. Author searches: searches for other articles by all authors of articles included in the review were performed in Medline and Health Management Information Consortium (the two databases that provided the greatest number of relevant hits) for all available years up to and including October 2004.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria for studies included in the review

Studies were considered relevant and included in the review if they reported an evaluation of welfare rights advice in a healthcare setting in terms of health, social or financial outcomes. We defined 'welfare rights advice' as expert advice concerning entitlement to and claims for welfare benefits. 'Healthcare settings' were defined as health related buildings – including primary, secondary or tertiary care centres – or where clients were identified through primary, secondary or tertiary care patient lists.

A preliminary scoping review revealed that: there is substantial 'grey literature' in this area; the main study design used is uncontrolled before and after studies; and outcome variables studied vary widely. In order to provide an overview of the wide variety of impacts of welfare rights advice delivered in healthcare settings, we did not restrict our review to any particular outcomes, study design, methods, study population or place of publication (i.e. studies not published in peer reviewed journals were not necessarily excluded). Although searches were conducted in English, no a priori exclusions were made based on the language of publication. However, we did not identify any potentially relevant studies that were not written in English.

The process of determining whether studies should be included in the review was made by one reviewer (JA) in the majority of cases. The review team discussed any cases where doubt concerning inclusion remained after retrieval of reports.

Data abstraction

Data were abstracted from reports and papers ("studies") in the review using a structured proforma. Data collected included: descriptive details of interventions delivered and evaluations performed, and outcome data on all financial, social and health outcomes measured. Data abstraction from each report was performed independently by pairs of reviewers with information entered onto a Microsoft Access database for recording and analysis. In cases where reviewers were found to disagree about the data abstracted, reviewers met to discuss disagreements. If agreement could not be reached, the whole review team was asked to consider the issue and reach a consensus.

Where investigators reported data on the same outcome at a number of different follow up times, information from all follow ups was abstracted and reported. Where information on a number of different outcomes was reported from the same project, information on all outcomes reported was abstracted and the results presented to highlight that these are not independent findings. When we retrieved both an internal report and peer reviewed paper on the same project, both documents were scrutinised and if discrepancies were found, results reported in peer-reviewed journals were used in our assessment.

Assessment of study quality

As the majority of quantitative evaluations of welfare rights advice delivered in healthcare settings use a simple before and after design (6 of 8 studies that reported data on health and social outcomes employed a before and after design, all 29 studies that reported data on financial outcomes employed a before and after design), we felt it inappropriate to assess the quality of studies reported in terms of a formal scoring framework. Instead, we collected information on various aspects of methodology and report this in a descriptive analysis.

As with the quantitative evaluative work in this area, few qualitative studies, or components of studies, identified in the scoping review appeared to meet many of the quality standards for qualitative research that have been proposed[18,19]. As before, we did not apply any formal framework for determining quality in qualitative work. Instead, information on various aspects of methodology were recorded and are reported descriptively

Analyses and reporting

Given the wide variety of studies that we anticipated including in the review, a formal meta-analysis was not planned and results are reported primarily in a narrative form according, as far as possible, to the schema proposed by Stroup et al (2000) – a checklist of topics that should be covered in meta-analyses of observational studies under the general headings of background, search strategy, methods, results, discussion and conclusions devised by an expert working group (The Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) Group)[20].

Ethics and research governance

This review of published and publicly available literature did not require ethical approval.

Results

Search results

Results of electronic database searches for articles, citation searches and author searches are reported in Table 1, Table 2 and Table 3 respectively. Numerous reports were identified by responders to the requests for information. Overall, 55 different studies, considered to meet the inclusion criteria, were included in the review and are summarised in Table 4. Where single reports contained data on two or more projects that differed substantially in design[21,22], these different projects are reported as separate studies in the results. Table 5 lists those papers and reports retrieved but not included in the review with reasons for exclusion. Only one study included in the review was not UK based[23].

Table 1.

results of electronic database searches

| Database | Hits | Of some relevance | Included in review |

| Ageinfo | 5 | 1[34] | 1[34] |

| British Humanities Index | 67 | 0 | 0 |

| CINAHL | 99 | 6[35–40] | 1[40] |

| Embase | 141 | 7[25, 37, 41–45] | 4[25, 42–44] |

| Health Management Information Consortium | 38 | 14[14, 36–38, 40, 42, 43, 45–47] | 4[14, 40, 42, 43] |

| Health Financials Evaluations Database | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| International Bibliography of the Social Sciences | 113 | 0 | 0 |

| MDX health | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Medline | 286 | 15[25, 34, 36, 38, 41–45, 48–53] | 5[25, 34, 42–44] |

| PAISArchive | 82 | 0 | 0 |

| PAISInternational | 83 | 2[54, 55] | 0 |

| PsycINFO | 686 | 3[41, 53, 56] | 0 |

| Science citation index | 150 | 8[25, 37, 41–45, 57] | 5[25, 42–44, 57] |

| SIRS researcher | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| Social science citation index | 237 | 7[36–38, 41–43, 45] | 2[42, 43] |

| Social Services Abstracts | 147 | 3[36, 38, 58] | 0 |

| Sociological Abstracts | 293 | 2[59, 60] | 0 |

| Zetoc | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Table 2.

results of citation searches

| Article | Hits | Of some relevance | Included in review |

| Abbott and Hobby (2000)[42] | 3 | 3[36, 37, 61] | 1[61] |

| Coppel et al (1999)[43] | 7 | 7[36, 37, 42, 61–64] | 3[42, 61, 63] |

| Cornwallis and O'Neil (1998)[65] | Journal (Hoolet) not listed | ||

| Dow and Boaz (1994)[23] | 4 | 1[66] | 1[66] |

| Frost-Gaskin et al (2003)[66] | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Galvin et al (2000)[67] | 4 | 4[25, 36, 37, 61] | 2[25, 61] |

| Greasley and Small (2005) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Hoskins and Smith (2002)[63] | 2 | 1[68] | 1[68] |

| Langley et al (2004)[25] | 1 | 1[68] | 1[68] |

| Memel and Gubbay (1999)[57] | 2 | 2[24, 61] | 2[24, 61] |

| Memel et al (2002)[24] | 3 | 2[25, 68] | 2[25, 68] |

| Middleton et al (1993)[69] | 4 | 4[36, 37, 63, 64] | 1[63] |

| Moffatt et al (2004)[70] | Journal (Critical Public Health) not listed | ||

| Paris and Player (1993)[71] | 21 | 14[36, 37, 43, 44, 61, 63, 64, 67, 68, 72–76] | 7[43, 44, 61, 63, 67, 68, 72] |

| Powell et al (2004)[68] | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Reading et al (2002)[72] | 1 | 1[61] | 1[61] |

| Sherratt et al (2000)[77] | Journal (Primary Healthcare Research and Development) not listed | ||

| Toeg et al (2003)[61] | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Veitch and Terry (1993)[44] | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Table 3.

results of author searches

| Medline | Health Management Information Consortium | |||||

| Author | Hits | Of some relevance | Included in review | Hits | Of some relevance | Included in review |

| Abbott, S | 38 | 4[36, 37, 42, 78] | 1[42] | 3 | 1[42] | 1[42] |

| Boaz, TL | 9 | 1[23] | 1[23] | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Coppel, DH | 1 | 1[43] | 1[43] | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Cornwallis, E | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Dow, MG | 17 | 1[23] | 1[23] | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Downey, D | 45 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Frost-Gaskin, M | 1 | 1[66] | 1[66] | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Galvin, K | 35 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 1[67] | 1[67] |

| Greasley, P | 8 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 0 |

| Gubbay, D | 3 | 2[25, 68] | 2[25, 68] | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Hehir, M | 34 | 1[24] | 1[24] | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Henderson, C | 147 | 1[66] | 1[66] | 17 | 0 | 0 |

| Hewlett, S | 21 | 3[24, 25, 68] | 3[24, 25, 68] | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Hobby, L | 5 | 3 | 10 | 6[34, 36, 40, 42, 78, 79] | 4[34, 40, 42, 79] | |

| Hoskins, RA | 12 | 1[63] | 1[63] | 5 | 2[63, 64] | 1[63] |

| Hudson, E | 42 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Illife, S | 85 | 1[61] | 1[61] | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Jackson, D | 501 | 0 | 0 | 19 | 1[67] | 1[67] |

| Jones, K | 581 | 0 | 0 | 90 | 1[77] | 1[77] |

| Kirwan, J | 47 | 1[68] | 1[68] | 6 | 0 | 0 |

| Langley, C | 25 | 3[24, 25, 68] | 3[24, 25, 68] | 6 | 0 | 0 |

| Lenihan, P | 13 | 1[61] | 1[61] | 10 | 1[61] | 1[61] |

| Means, R | 13 | 1[68] | 1[68] | 63 | 0 | 0 |

| Memel, D | 6 | 1[68] | 1[68] | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| Mercer, L | 16 | 1[61] | 1[61] | 1 | 1[61] | 1[61] |

| Middleton, P | 51 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 1[77] | 1[77] |

| Moffatt, S | 29 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| O'Kelly, R | 6 | 1[66] | 1[66] | 8 | 0 | 0 |

| O'Neil, J | 101 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 0 |

| Packham, CK | 11 | 1[43] | 1[43] | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Paris, JA | 14 | 1[71] | 1[71] | 2 | 1[71] | 1[71] |

| Player, D | 11 | 1[71] | 1[71] | 13 | 1[71] | 1[71] |

| Pollock, J | 86 | 2[25, 68] | 2[25, 68] | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Powell, JE | 57 | 1[68] | 1[68] | 22 | 0 | 0 |

| Reading, R | 28 | 1[80] | 1[80] | 14 | 0 | 0 |

| Reynolds, S | 106 | 1[72] | 1[72] | 13 | 0 | 0 |

| Sharples, A | 25 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1[67] | 1[67] |

| Sherratt, M | 4 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1[77] | 1[77] |

| Small, P | 15 | 0 | 0 | 25 | 0 | 0 |

| Smith, LN | 40 | 1[63] | 1[63] | 26 | 0 | 0 |

| Stacy, R | 21 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| Steel, S | 18 | 1[72] | 1[72] | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| Toeg, D | 6 | 1[61] | 1[61] | 1 | 1[61] | 1[61] |

| Varnam, MA | 13 | 1[43] | 1[43] | 7 | 1[43] | 1[43] |

| White, M | 579 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Table 4.

summary of interventions delivered and evaluations performed (studies included in the review)

| Authors (date) | Intervention delivered | Evaluation performed | ||||||

| Who gave advice? | Where was advice given? | Referral system | Eligibility criteria (size of eligible population) | Financial | Non-financial, before-and-after design | Non-financial comp./control group | Qualitative | |

| Abbott & Hobby (1999)[79] | CAB worker | primary care or client's home | PHCT, self | all registered at 7 practices | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Abbott & Hobby (2002)[34] | CAB worker and city council welfare rights officer | primary care | variable | (94+ practices) | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Actions (2004)[81] | welfare rights advisers | primary care, clients' homes, telephone | self, medical staff, friends and family, voluntary and community _rganizations, social services, various other services | not reported | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| Bennett (1997)[82] | CAB worker | CAB office | PHCT | all registered at 3 practices | Yes | No | No | No |

| Borland (2004)[83, 84] | CAB worker | primary care, community hospitals, CAB offices, client's home | PHCT, self, any other agency | (Wales wide) | No | No | No | Yes |

| Bowran (1997)[85] | CAB worker | primary care | not reported | (n = 12500) | No | No | No | Yes |

| Broseley Health and Advice Partnership (2004)[86] | CAB worker | Primar care | self and all those registered at practice aged over 75 invited to take part | those registered at health centre | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| Bundy (2002)[87, 88] | city council welfare rights officer and CAB worker | primary care | PHCT, self | (9 practices) | Yes | No | No | No |

| Bundy (2003)[88] | city council welfare rights officer and CAB worker | primary care | PHCT, self, any other agency | all registered at practices covering 1/3 of those registered in Salford | Yes | No | No | No |

| Coppell et al (1999)[43] | welfare rights officer | primary care | PHCT, self | anyone (n = 4057) | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| Cornwallis & O'Neil (1998)[65] | Money advice worker | primary care | PHCT, self | all registered at practice(s) (n = 7600) | No | No | No | Yes |

| Derbyshire CC WRS (1997)[89] | welfare rights officer | primary care | PHCT, self | all registered at practice(s) (n = 23 039) | Yes | No | No | No |

| Derbyshire CC WRS (1998a)[22] | welfare rights officer | primary care | not reported | all registered at 2 practices | Yes | No | No | No |

| Derbyshire CC WRS (1998b)[22] | Welfare rights service worker | primary care | PHCT and targeted mailshots | (4 practices) | Yes | No | No | No |

| Dow & Boaz (1994)[23] | Linkage worker trained to assist in application for benefit | Clients' home or treatment facility | All individuals registered at 2 community mental health centres over 18 not currently claiming benefits, random sample of those meeting criteria at third centre, possibly eligible for benefits at screening | Screening form used – US citizen or resident alien, income <$600/month ($900 if married), one of: HIV+, 65+, blind, deaf, disabled | No | No | Yes | No |

| Emanuel & Begum (2000)[90] | CAB worker | primary care | PHCT, self | anyone (n = 12 601) | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Farmer & Kennedy (2001)[91] | CAB worker | primary care, hospital | at hospitals – from ward staff to social work staff to CAB worker | not reported | No | No | No | Yes |

| Fleming & Golding (1997)[92] | CAB worker | primary care | not reported | all registered at 21 practices | No | No | No | Yes |

| Frost-Gaskin et al (2003)[66] | Mind benefit advisor | Mental health resource and day centres (primary care) | None – advisors approached as many regular attendees as possible | all regular attendees (population of those eleigible to attend = 313 510) | Yes | No | No | No |

| Ferguson & Simmons[93] | Community Links workers (local advice provider) | primary care | Mailshot to registered patients, GP referral | (50% of surgeries in London Borough of Newham) | No | No | Mp | Yes |

| Galvin et al (2000)[67, 94] | CAB worker | primary care | PHCT | (7 practices) | No | No | No | Yes |

| Greasley (2003)[95] and Greasley & Small (2005)[96] | 12 advisors from 6 agencies | primary care | PHCT, self, any other agency | (n = 106 707) | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| Griffiths (1992)[97] | city council welfare rights officer | primary care | PHCT, self, any other agency | (2 health centres) | Yes | No | No | No |

| Hastie (2003)[98] | CAB worker | primary care, 2 other local locations | GP, self | not reported | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| High Peak CAB (1995)[99] | CAB worker | primary care | not reported | all those in town (n = 2500) | No | No | No | No |

| High Peak CAB (2001)[100] | CAB workers | not reported | not reported | not reported | Yes | No | No | No |

| High Peak CAB (2003)[101] | CAB workers | primary care | PHCT, self, other agencies | all registered at practices involved | Yes | No | No | No |

| Hoskins & Smith (2002)[63] | welfare rights officer | client's home | community nurses screened for attendance allowance eligibility opportunistically from their client list and referred screen positive | those >64 who in community nurses opinion were physically/mentally frail (population>64 = 1690) | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| Hoskins et al (in press)[102] | money advice workers | clients' homes | community nurses screened for attendance allowance eligibility from their client list and referred screen positive | those over 64 who appeared to have unmet clinical needs | Yes | No | No | No |

| Knight (2002)[103] | welfare benefits advisor | primary care and client's home | all aged 75+ identified through GP and sent invitation to take part | all aged 75+ in central Liverpool PCT area (n = 31 000) | No | No | No | Yes |

| Lancashire CC WRS (2001)[104] | welfare rights officer | client's home | all patients aged 80+ invited to take part | all registered at 3 practices 80+ | No | No | No | No |

| Langley et al (2004)[25] | Welfare benefits advice worker | primary care, hospital, client's home, local CAB | after consent obtained, sent health assessment questionnaire. Those with score >1/5 contacted by advisor and offered advice session | over 16 with rheumatoid arthritis or osteoarthritis of knee or hip for >1 yr plus NSAID recruited from 20 practices. If >100 eligible from any practice, random sample of 100 | No | No | No | No |

| Lishman-Peat & Brown (2002)[105] | not reported | primary care and client's home | PHCT, self | (5 practices) | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| MacMillan & CAB Partnership (2004)[106] | CAB workers | clients' homes, "acute and primary care locations" and cancer information centres | from nursing staff at 3 hospitals and community MacMillan nurses | cancer patients and their families | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| Memel & Gubbay (1999)[57] | welfare rights advisor | primary care | not reported | not reported | No | No | No | No |

| Memel et al (2002)[24] | CAB worker | primary care or hospital | those with RA or OA from follow up patients at rheumatology outpatients at a teaching hospital and those from two GP surgeries who had take part in other research project | diagnosis of OA or RA, being seen at outpatients or registered at participating GP, health assessment questionnaire score of 2 or more, not currently claiming attendant's allowance or disability living allowance | No | No | No | No |

| Middlesbrough WRU (1999)[107] | city council welfare rights officer | primary care and client's home where necessary | PHCT | all registered at practice(s) (n = 90 500) | No | No | No | No |

| Middlesbrough WRU (2004)[108] | welfare rights officers | primary care and clients' homes | GPs, practice receptionists, district nurses, health visitors, health and social care assessors, Macmillan nurses, social workers, age concern | those registered at practice aged over 50 | Yes | No | No | No |

| Middleton et al (1993a)[69] | housing department welfare rights advisor | primary care | not reported | (n = 15 000) | Yes | No | No | No |

| Middleton et al (1993b)[69] | CAB worker | primary care | not reported | (4 practices) | Yes | No | No | No |

| Moffatt (2004)[109] | Welfare rights worker | client's home | invitation to take part sent to random sample of those aged 65+ | random sample (n = 400+) of those aged 65+ registered at 4 practices | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| Moffatt et al (2004)[110, 111] | CAB worker | primary care | PHCT, self | all registered at practice | No | No | No | Yes |

| Paris & Player (1993)[71] | CAB worker | primary care | PHCT | (n = 64 779) | Yes | No | No | No |

| Reading et al (2002)[72, 80] | CAB worker | primary care | letter to all eligible families | all families registered at 3 health centres with child under 1 year | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| Roberts (1999)[112] | CAB worker | primary care, client's home, letter, telephone | PHCT, self | (5 practices) | No | No | No | Yes |

| Sedgefield and district AIS (2004)[113] | CAB worker | primary care | PHCT | all registered at practice(s) | No | No | No | Yes |

| Sherratt et al (2000)[77] | CAB worker | 3 models – primary care, telephone, client's home | PHCT (GP surgery, telephone) or targeted at housebound (home visits only) | all registered at 7 or 4 practices (in-surgery and telephone advice), all housebound patients registered with GP in Gateshead (home visits) | No | No | No | Yes |

| Southwark CC MAS (1998)[114] | welfare rights officer | primary care | not reported | (n = 76 417) | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| Toeg et al (2003)[61] | CAB worker | primary care, client's home or telephone | all those eligible invited by letter from GP | registered at practice, 80 years +, living in own home (n = 12 000) | Yes | No | No | No |

| Vaccarello (2004)[115] | HABIT officer | client's home | invitation letters from GPs to those aged 75+ | all aged 75 in Liverpool (n = 31 000) | No | No | No | Yes |

| Veitch (1995) GP[21] | CAB worker | primary care | not reported | (21 practices) | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Veitch (1995) mental health[21] | CAB worker | health and social services sites (mental health centres) | not reported | not reported | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Veitch & Terry (1993)[44] | CAB worker | primary care | PHCT | (n = 64 779) | No | No | No | No |

| Widdowfield & Rickard (1996)[116] | CAB worker | primary care | PHCT, self | all registered at practice(s) | No | No | No | Yes |

| Woodcock (2004)[117] | city council welfare rights officer | primary care | PHCT | not reported | No | No | No | Yes |

CAB = Citizen's Advice Bureau; PHCT = any member of primary healthcare team; GP = general practitioner; OA = osteoarthritis; RA = rheumatoid arthritis

Table 5.

Papers, reports and book chapters retrieved but not included in the review with reasons for exclusion

| Author (date) | Description of content and reason for exclusion |

| Abbot & Hobby (2003)[36] | Description of service users rather than evaluation of impacts of service. |

| Abbott (2000)[118] | Multi-disciplinary support service for patients with mixed social and health needs with small welfare rights component but no evaluation of welfare rights component in isolation. |

| Abbott (2002)[37] | Discussion of where welfare rights advice fits in terms of health interventions. No evaluation of any specific intervention programme. |

| Alcock (1994)[119] | Discussion of potential benefits of welfare advice in primary healthcare settings and recommendations for development of such services, not evaluation of single/multiple project(s) |

| Barnes (2000)[120] | Citizens advice service for patients at a long stay psychiatric hospital – including a limited amount of welfare rights advice. No specific evaluation of welfare rights advice component. |

| Barnsley Community Legal Service Partnership (2003)[121] | Very brief mention of a welfare rights advice project in primary care within a larger report – no evaluation of service. |

| Bebbington & Unell (2003)[122] | Description of a multidisciplinary telephone advice line for older people with some evaluation of use. No evaluation of welfare rights advice component. |

| Bebbington et al (?year)[123] | Description of a multidisciplinary telephone advice line for older people with some evaluation of use. No evaluation of welfare rights advice component. |

| Bird (1998)[124] | Audit of CAB services for those with mental illness – not evaluation of any specific intervention programme delivered in a healthcare setting. |

| Buckle (1986)[125] | Discussion of eligibility for various benefits. No evaluation of specific intervention. |

| Bundy (2001)[39] | Brief description of 'The Health and Advice Project' – full evaluation report included in review |

| Burton & Diaz de Leon (2002)[126] | Review of a number of welfare advice services but only service for which any outcomes are report does not appear to have been delivered in a healthcare setting. |

| Clarke et al (2001)[127] | Multidisciplinary service to provide advice and support to individuals and families with complex social and health problems – including welfare rights advice. No specific evaluation of welfare rights advice component. |

| Craig et al (2003)[128] | Review and primary research on the impact of addition welfare benefit income in older people – not specifically of welfare rights advice delivered in a healthcare setting. |

| Dowling et al (2003)[129] | Systematic review of effectiveness of financial benefits in reducing inequalities in child health with limitation to randomised controlled trials. Not evaluation of welfare rights advice. |

| Emanuel (2002)[130] | Description of service rather than evaluation of impacts of service. |

| Ennals (1990)[131] | Discussion of importance of welfare benefits in relation to health and eligibility for benefits. |

| Ennals (1993)[74] | Editorial relating to article (Paris and Player, 1993) included in review |

| Evans (1998)[132] | Report of client profile, sources of referrals and problems raised at a welfare rights advice service in primary care. No evaluation of effect on clients. |

| Forrest (2003)[133] | Very brief mention of a welfare rights advice project in primary care within a larger report – no evaluation of service. |

| Gask et al (2000)[134] | Very brief mention of a welfare rights advice project in primary care within a larger report – no evaluation of service. |

| Greasley & Small (2002)[135] | A review of previously published work on welfare rights advice delivered in primary care. Not an evaluation of a specific intervention. |

| Greasley (2005)[136] | Discussion of the process of videoing interviews that happened to be with users of a welfare rights advice service in primary healthcare. No evaluation of the impact of the intervention service itself. |

| Green (1998)[137] | Description of eligibility for benefits whilst an in-patient. |

| Green et al (2004)[138] | Review of health impact assessments in a variety of areas with very limited mention of Longworth et al (2003) |

| Harding et al (2002)[38] | Audit of provision of welfare rights advisors in general practices and perceived impact of these facilities on the primary healthcare team. No evaluation of any specific programme on clients. |

| Hobby & Abbott (1999)[78] | Brief description of 'The Health and Advice Project' – full evaluation report included in review |

| Hobby et al (1998)[15] | A survey of CAB offering outreach in primary care settings with collation of some information. Limited data on impacts of advice not included in other, primary, reports. |

| Hoskins et al (2000)[64] | Discussion of potential importance of welfare benefits advice for health with proposal that nurses could become involved in giving advice. No actual intervention described or evaluated. |

| Jarman (1985)[45] | Description of computer programme to help determine eligibility for various welfare benefits. No evaluation of impact of programme. |

| Kalra et al (2003)[48] | Methods of family planning _ounseling, not welfare rights advice related. |

| Longworth et al (2003)[139] | Discussion of potential, rather than actual, impact of service |

| NACAB (1999)[10] | Magazine type articles on various different studies with case studies, not evaluation of single/multiple project(s) |

| Norowska (2004)[62] | Description of delayed application for and provision of attendance allowance. No intervention to improve take-up discussed. |

| Okpaku (1985)[140] | Audit of mentally ill people applying for benefit and problems they encounter. No intervention programme to provide advice with claiming. |

| Pacitti & Dimmick (1996)[56] | Descriptive study of extend and correlates of underclaiming of welfare benefits amongst individuals with mental illness. |

| Powell et al (2004)[68] | Financial evaluation of welfare rights advice programme with repetition of financial impacts for clients of data in Langley et al (2004) and Memel et al (2004) |

| Reid et al (1998)[141] | Assessment of staff awareness and involvement in an ongoing welfare rights advice project in primary care. No evaluation of impact of service on users. |

| Riverside Advice Ltd (2004)[142] | Report of welfare rights project for those with mental illnesses. No evaluation of impact of service on users. |

| Scully (1999)[143] | Report of training programme for welfare rights advisors working within primary care settings, not evaluation of a specific service. |

| Searle (2001)[144] | Description of a multidisciplinary telephone advice line for older people. No evaluation of welfare rights advice component. |

| Sherr et al (2002)[145] | Audit of current practice in three London boroughs with exploration of attitudes to potential services, not evaluation of service in place. |

| Stenger (2003)[35] | Discussion of moving from welfare to work, not of advice to help claim welfare benefits. |

| Strachan (1995)[146] | Proceedings of a conference with descriptions but no evaluations of welfare rights advice services in healthcare settings. |

| Tameside MBC [33, 147] | Description of rationale for service and recommendations for the future, not evaluation of service |

| Thomson et al (2004)[95] | Discussion of problems involved in rigorous scientific evaluation of social interventions – including welfare rights advice – but no evaluation of specific intervention. |

| Venables (2004)[148] | Annual report of welfare rights service not based in a healthcare setting. |

| Watson (2000)[149] | Multidisciplinary intervention project with small welfare rights component but no evaluation of welfare rights component in isolation. |

| Waterhouse (1996)[150] | Profile of users of a welfare rights advice service in primary care, along with advice sought, service provided and discussion of logistic issues. No evaluation of effect on clients. |

| Waterhouse (2003)[151] | Report on logistical problems and solutions to setting up welfare advice service in primary care. No evaluation of effect on clients. |

| Waterhouse and Benson (2002)[152] | Background paper proposing establishment of a welfare rights service within a PCT. No evaluation of new project. |

| West Berkshire CAB (2004)[153] | Report of service activity and financial statement – no evaluation of service. |

| Williams (1982)[154] | Description of a hospital based services. Evaluation limited to type of contacts and activity engaged in by welfare advisor. |

Interventions delivered

Interventions delivered took a number of different forms. Some identification of who delivered the intervention was reported in 54 (98%) cases. In 30 (55%) instances all or some of the advice was delivered by employees of, or volunteers for, the CAB. In a further 22 (40%) studies all or some of the advice was delivered by welfare rights workers, officers and advisers – sometimes, but not always, explicitly identified as employees of local government.

The location where advice was delivered was reported in 54 (98%) cases. In 31 (57%) instances advice was delivered only in primary care premises such as general practice surgeries or health centres. In a further 16 (29%) cases advice was delivered in primary care premises along with one or more other locations, including clients' homes, hospitals and local CAB. Overall, 18 (33%) studies offered advice within clients' own homes – either exclusively or as an available option.

The referral system by which individuals gained access to the welfare rights advice was reported in 44 (80%) studies. In 32 (73%) studies referral could be from any member of the primary care team, a member of another relevant agency, via self referral from clients or via a combination of these modes. In 11 (25%) studies there were more formal eligibility criteria and invitational processes.

Criteria for who was eligible to receive the welfare rights advice given were reported in 31 (56%) studies. In 14 (45%) studies all patients registered at the general practice or practices participating in the project were eligible to receive advice. In a further 15 (48%) studies some sort of screening or sampling procedure was used to restrict eligibility to certain subgroups of the population – often those suffering from particular conditions or over a certain age. In two cases it was explicitly stated that welfare rights advice was only offered for a limited number of specified benefits (Attendance Allowance and Disability Living Allowance in both cases)[24,25].

The size of the population eligible to receive the advice given was reported in 17 (31%) studies. Eligible populations ranged in size from 1690 to 313 510 with a median of 23 039.

Health and social outcomes – studies with a comparison or control group

Results from studies that reported the use of a comparison or control group are summarised in Table 6. Of the seven studies with a control or comparison group that reported non-financial outcomes, only one[23] randomly assigned individuals to the intervention or control group.

Table 6.

health and social outcomes (validated measurement instruments), studies with a control or comparison group (studies included in the review)

| Authors (date) | Outcome measure | Nature of control/comparison group | Random allocation? | Control group N at baseline | Intervention group N at baseline | Control group mean score at baseline | Intervention group mean score at baseline | Follow up period | Control N at follow up | Intervention N at follow up | Control group mean score at follow up | Intervention group man score at follow up | p-value* |

| Abbott & Hobby (1999)[79] | SF36 physical functioning (change in score) | Those whose income didn't increase following advice allocated to comparison group | No | 20 | 48 | NR | NR | 6 months | 20 | 48 | 0 | 2.4 | p > 0.05 |

| SF36 role functioning physical (change in score) | No | 20 | 48 | NR | NR | 6 months | 20 | 48 | -2.5 | 2.1 | p > 0.05 | ||

| SF36 bodily pain (change in score) | No | 20 | 48 | NR | NR | 6 months | 20 | 48 | 1 | -0.5 | p > 0.05 | ||

| SF36 general health (change in score) | No | 20 | 48 | NR | NR | 6 months | 20 | 48 | 2.5 | 3.3 | p > 0.05 | ||

| SF36 vitality (change in score) | No | 20 | 48 | NR | NR | 6 months | 20 | 48 | -7 | 7.7 | p = 0.001 | ||

| SF36 social functioning (change in score) | No | 20 | 48 | NR | NR | 6 months | 20 | 48 | -1.3 | 2.9 | p > 0.05 | ||

| SF36 role functioning emotional (change in score) | No | 20 | 48 | NR | NR | 6 months | 20 | 48 | 8.3 | 14.6 | p > 0.05 | ||

| SF36 mental health (change in score) | No | 20 | 48 | NR | NR | 6 months | 20 | 48 | -4.8 | 7.2 | p = 0.019 | ||

| Abbott & Hobby (2002)[34] | SF36 physical functioning | Those whose income didn't increase following advice allocated to comparison group | No | 50 | 150 | 34 | 29.5 | 6 months | 50 | 150 | 34.2 | 30.6 | p = 0.65 |

| SF36 physical functioning | No | 50 | 150 | 34 | 29.5 | 12 months | 50 | 150 | 37.7 | 28.9 | p = 0.17 | ||

| SF36 role functioning physical | No | 50 | 150 | 15.5 | 18.9 | 6 months | 50 | 150 | 24.5 | 28.1 | p = 0.5 | ||

| SF36 role functioning physical | No | 50 | 150 | 15.5 | 18.9 | 12 months | 50 | 150 | 27 | 26 | p = 0.74 | ||

| SF36 bodily pain | No | 50 | 150 | 29.2 | 34.8 | 6 months | 50 | 150 | 30 | 43.1 | p = 0.013 | ||

| SF36 bodily pain | No | 50 | 150 | 29.2 | 34.8 | 12 months | 50 | 150 | 36.4 | 39.4 | p = 0.71 | ||

| SF36 general health | No | 50 | 150 | 35.6 | 31.7 | 6 months | 50 | 150 | 34 | 32.3 | p = 0.59 | ||

| SF36 general health | No | 50 | 150 | 35.6 | 31.7 | 12 months | 50 | 150 | 32.3 | 32.1 | p = 0.35 | ||

| SF36 vitality | No | 50 | 150 | 33.2 | 28.7 | 6 months | 50 | 150 | 28.4 | 32.3 | p = 0.13 | ||

| SF36 vitality | No | 50 | 150 | 33.2 | 28.7 | 12 months | 50 | 150 | 29.2 | 28.4 | p = 0.26 | ||

| SF36 social functioning | No | 50 | 150 | 45.8 | 42.3 | 6 months | 50 | 150 | 52.5 | 50.2 | p = 0.58 | ||

| SF36 social functioning | No | 50 | 150 | 45.8 | 42.3 | 12 months | 50 | 150 | 54.6 | 49.2 | p = 0.58 | ||

| SF36 role functioning emotional | No | 50 | 150 | 48.7 | 40.8 | 6 months | 50 | 150 | 36.7 | 51.7 | p = 0.17 | ||

| SF36 role functioning emotional | No | 50 | 150 | 48.7 | 40.8 | 12 months | 50 | 150 | 42.7 | 52.2 | p = 0.02 | ||

| SF36 mental health | No | 50 | 150 | 57.1 | 53 | 6 months | 50 | 150 | 56 | 55.9 | p = 0.84 | ||

| SF36 mental health | No | 50 | 150 | 57.1 | 53 | 12 months | 50 | 150 | 56 | 58.3 | p = 0.03 | ||

| Emanuel & Begum (2000)[90] | HADS anxiety | Those whose income didn't increase following advice allocated to comparison group | No | 28 | 12 | 12.03 | 12 | 9 months | 28 | 13 | 11.14 | 12.58 | p > 0.05 |

| HADS depression | No | 28 | 12 | 8.21 | 9.75 | 9 months | 28 | 13 | 7.86 | 9.33 | p > 0.05 | ||

| MYMOP symptom 1 | No | 28 | 12 | 4.48 | 4.64 | 9 months | 28 | 13 | 3.86 | 4.36 | p > 0.05 | ||

| MYMOP symptom 2 | No | 28 | 12 | 3.59 | 4.67 | 9 months | 28 | 13 | 2.41 | 5.33 | p > 0.05 | ||

| MYMOP activity | No | 28 | 12 | 4.17 | 5.7 | 9 months | 28 | 13 | 3.83 | 5 | p > 0.05 | ||

| MYMOP wellbeing | No | 28 | 12 | 3.86 | 4.55 | 9 months | 28 | 13 | 3.14 | 4.65 | p > 0.05 | ||

| MYMOP profile | No | 28 | 12 | 4.53 | 4.28 | 9 months | 28 | 13 | 3.44 | 4.79 | p > 0.05 | ||

| GP consultations in last 9 months | Control identified as next in individual on practice register matched for age and sex. | No | 39 | 39 | 70 | 187 | 9 months | 39 | 39 | 111 | 165 | p > 0.05 | |

| prescriptions in last 9 months | No | 39 | 39 | 122 | 239 | 9 months | 39 | 39 | 146 | 278 | p > 0.05 | ||

| referrals to secondary care in last 9 months | No | 39 | 39 | 3 | 21 | 9 months | 39 | 39 | 5 | 18 | p > 0.05 | ||

| Visits to A&E in last 9 months | No | 39 | 39 | 0 | 1 | 9 months | 39 | 39 | 2 | 0 | p > 0.05 | ||

| practice nurse contacts in last 9 months | No | 39 | 39 | 13 | 12 | 9 months | 39 | 39 | 6 | 11 | p > 0.05 | ||

| home visits in last 9 months | No | 39 | 39 | 5 | 3 | 9 months | 39 | 39 | 1 | 3 | p > 0.05 | ||

| out of hours calls in last 9 months | No | 39 | 39 | 2 | 3 | 9 months | 39 | 39 | 3 | 5 | p > 0.05 | ||

| social service referrals in last 9 months | No | 39 | 39 | 0 | 0 | 9 months | 39 | 39 | 0 | 0 | p > 0.05 | ||

| cervical cancer screening in last 9 months | No | 39 | 39 | 1 | 1 | 9 months | 39 | 39 | 5 | 7 | p > 0.05 | ||

| Reading et al (2002)[72] | Edinburgh postnatal depression scale | Six practices recruited – three allocated to intervention group, three to control group. | Yes | 173 | 88 | 7.7 | 9.7 | NR | 153 | 66 | 7.1 | 8.1 | p > 0.05 |

| Prevalence of maternal smoking | Yes | 173 | 88 | 25 | 34 | NR | 153 | 66 | 20 | 36 | p > 0.05 | ||

| Maternal non-routine GP visits per year | Yes | 173 | 88 | NR | NR | NR | 153 | 66 | 3.1 | 3.5 | p > 0.05 | ||

| Maternal prescriptions | Yes | 173 | 88 | NR | NR | NR | 153 | 66 | 2.4 | 2.1 | p > 0.05 | ||

| Child general health "very good" | Yes | 173 | 88 | NR | NR | NR | 153 | 66 | 51 | 44 | p > 0.05 | ||

| Child more than 2 minor illnesses in last 3 months | Yes | 173 | 88 | NR | NR | NR | 153 | 66 | 18 | 22 | p > 0.05 | ||

| Child accident requiring attention in last year | Yes | 173 | 88 | NR | NR | NR | 153 | 66 | 10 | 6 | p > 0.05 | ||

| Child behaviour problems | Yes | 173 | 88 | NR | NR | NR | 153 | 66 | 5 | 10 | p > 0.05 | ||

| Child sleeping problems | Yes | 173 | 88 | 12 | 13 | NR | 153 | 66 | 12 | 14 | p > 0.05 | ||

| Child currently breast fed or stopped aged >4 months | Yes | 173 | 88 | 31 | 31 | NR | 153 | 66 | 23 | 17 | p > 0.05 | ||

| Child non-routine GP visits per year | Yes | 173 | 88 | NR | NR | NR | 153 | 66 | 4.2 | 4.2 | p > 0.05 | ||

| Child prescriptions | Yes | 173 | 88 | NR | NR | NR | 153 | 66 | 2.4 | 2 | p > 0.05 | ||

| Veitch (1995) GP[21] | NHP total score | Those identified by control practices who would have been referred had service been available. | No | 5 | 5 | NR | NR | NR | 5 | 5 | NR | NR | p > 0.05 |

| NHP energy | No | 5 | 5 | NR | NR | NR | 5 | 5 | NR | NR | p > 0.05 | ||

| NHP pain | No | 5 | 5 | NR | NR | NR | 5 | 5 | NR | NR | p > 0.05 | ||

| NHP emotional reaction | No | 5 | 5 | NR | NR | NR | 5 | 5 | NR | NR | p > 0.05 | ||

| NHP sleep | No | 5 | 5 | NR | NR | NR | 5 | 5 | NR | NR | p > 0.05 | ||

| NHP social isolation | No | 5 | 5 | NR | NR | NR | 5 | 5 | NR | NR | p > 0.05 | ||

| NHP physical mobility | No | 5 | 5 | NR | NR | NR | 5 | 5 | NR | NR | p = 0.09 | ||

| Veitch (1995) mental health[21] | NHP total score | Those identified by control mental health centres who would have been referred had service been available. | No | 12 | 36 | NR | NR | NR | 12 | 18 | NR | NR | p = 0.4588 |

| NHP energy | No | 12 | 36 | NR | NR | NR | 12 | 18 | NR | NR | p = 0.2312 | ||

| NHP pain | No | 12 | 36 | NR | NR | NR | 12 | 18 | NR | NR | p = 0.0700 | ||

| NHP emotional reaction | No | 12 | 36 | NR | NR | NR | 12 | 18 | NR | NR | p = 0.0466 | ||

| NHP sleep | No | 12 | 36 | NR | NR | NR | 12 | 18 | NR | NR | p = 0.3095 | ||

| NHP social isolation | No | 12 | 36 | NR | NR | NR | 12 | 18 | NR | NR | p = 0.4872 | ||

| NHP physical mobility | No | 12 | 36 | NR | NR | NR | 12 | 18 | NR | NR | p = 0.1312 | ||

| Dow & Boaz (1994)[23] | applied for award | Random allocation to intervention/control group | Yes | 389 | 387 | 0 | 0 | 6 months | 311 | 303 | 20 | 63 | p < 0.001 |

| applied for award | Yes | 389 | 387 | 0 | 0 | 8 months | 311 | 303 | 26 | 67 | p < 0.05 | ||

| applied for award | Yes | 389 | 387 | 0 | 0 | 11 months | 311 | 303 | 26 | 67 | p < 0.05 | ||

| received award | Yes | 389 | 387 | 0 | 0 | 6 months | 311 | 303 | 8 | 17 | p < 0.05 | ||

| received award | Yes | 389 | 387 | 0 | 0 | 8 months | 311 | 303 | 12 | 22 | p < 0.05 | ||

| received award | Yes | 389 | 387 | 0 | 0 | 11 months | 311 | 303 | 13 | 23 | p < 0.051 | ||

*comparison of change in score in intervention group with change in score in control or comparison group; SF36 = short form 36; MYMOP = Measure Yourself Medical Outcome Profile scale; GP = general practitioner; A&E = accident and emergency; NHP = Nottingham Health Profile; NR = not reported

Outcome measures used included the Short Form 36 (SF-36 – a general health scale)[26,27], the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS – a questionnaire commonly used to screen for anxiety or depression)[28], the Measure Yourself Medical Outcome Profile scale (MYMOP – a patient generated wellbeing scale)[29], the Nottingham Health Profile (NHP – a quality of life scale)[30], and the Edinburgh Post-natal Depression Scale[31], as well as whether or not benefits had been applied for or received, and a variety of measures of use of health services. The size of intervention groups at follow up ranged from 13 to 303 with five studies reporting intervention group sizes at follow up of less than 70. Control or comparison group sizes at follow up ranged from 12 to 311 with five studies having control or comparison group sizes at follow up of less than 51. Follow up periods ranged from six to 12 months.

The majority of studies assessed the effect of the advice by comparing change in scores between baseline and follow up in the control or comparison group with the intervention group. Out of 72 separate comparisons reported, 11 (15%) were statistically significant at the 5% level including comparisons relating to SF36 vitality, SF36 mental health, SF36 bodily pain, SF36 role functioning emotional, SF36 mental health, NHP emotional reactions and the proportion of participants who had both applied for and received an award.

Health and social outcomes – before-and-after study design

The six studies that reported non-financial results using recognised measurement scales and a before-and-after study design are summarised in Table 7. These studies used four different outcome measures – the SF36, HADS, MYMOP and NHP. Sample sizes included in follow up ranged from 22 to 244 with five out of six studies completing follow up on less than 55 individuals. Reported follow up periods ranged from six to 12 months. Out of 59 separate statistical comparisons reported, 6 (10%) were found to be significant – SF36 vitality, SF36 role functioning emotional, SF36 mental health, SF36 general health, NHP pain and NHP emotional reactions. Three studies, including one with a follow up sample size of 244 at six months and 200 at 12 months, reported no statistically significant comparisons at all.

Table 7.

Quantitative scalar health outcomes, before and after studies (studies included in the review)

| Authors (date) | Outcome measure | Baseline N | Baseline mean score | Follow up period | Follow up N | Follow up mean score | p-value* |

| Abbott & Hobby (1999)[79] | SF36 physical functioning | 48 | 20.8 | before vs after income increase | 48 | 23.1 | p > 0.05 |

| SF36 role functioning physical | 48 | 12.5 | before vs after income increase | 48 | 14.6 | p > 0.05 | |

| SF36 bodily pain | 48 | 25.5 | before vs after income increase | 48 | 24.9 | p > 0.05 | |

| SF36 general health | 48 | 26.7 | before vs after income increase | 48 | 30 | p > 0.05 | |

| SF36 vitality | 48 | 20.8 | before vs after income increase | 48 | 28.5 | p = 0.002 | |

| SF36 social functioning | 48 | 29.4 | before vs after income increase | 48 | 32 | p > 0.05 | |

| SF 36 role functioning emotional | 48 | 36.8 | before vs after income increase | 48 | 51.4 | p = 0.037 | |

| SF36 mental health | 48 | 45.9 | before vs after income increase | 48 | 53.1 | p = 0.005 | |

| Abbott & Hobby (2002)[34] | SF36 physical functioning | 345 | 35.8 | 6 months | 244 | 31.5 | p > 0.05 |

| SF36 physical functioning | 345 | 35.8 | 12 months | 200 | 30.6 | p > 0.05 | |

| SF36 role functioning physical | 345 | 22.8 | 6 months | 244 | 18.9 | p > 0.05 | |

| SF36 role functioning physical | 345 | 22.8 | 12 months | 200 | 18 | p > 0.05 | |

| SF36 bodily pain | 345 | 35.7 | 6 months | 244 | 33.2 | p > 0.05 | |

| SF36 bodily pain | 345 | 35.7 | 12 months | 200 | 33.4 | p > 0.05 | |

| SF36 general health | 345 | 34.8 | 6 months | 244 | 32.9 | p > 0.05 | |

| SF36 general health | 345 | 34.8 | 12 months | 200 | 32.6 | p > 0.05 | |

| SF36 vitality | 345 | 31.3 | 6 months | 244 | 29.9 | p > 0.05 | |

| SF36 vitality | 345 | 31.3 | 12 months | 200 | 29.8 | p > 0.05 | |

| SF36 social functioning | 345 | 40.9 | 6 months | 244 | 42.5 | p > 0.05 | |

| SF36 social functioning | 345 | 40.9 | 12 months | 200 | 43.2 | p > 0.05 | |

| SF36 role functioning emotional | 345 | 40.9 | 6 months | 244 | 40.4 | p > 0.05 | |

| SF36 role functioning emotional | 345 | 40.9 | 12 months | 200 | 42.8 | p > 0.05 | |

| SF36 mental health | 345 | 51.7 | 6 months | 244 | 53.1 | p > 0.05 | |

| SF36 mental health | 345 | 51.7 | 12 months | 200 | 54 | p > 0.05 | |

| Emanuel & Begum (2000)[90] | HADS anxiety | 40 | 12.03 | 9 months | 40 | 11.58 | p > 0.05 |

| HADS depression | 40 | 8.68 | 9 months | 40 | 8.3 | p > 0.05 | |

| MYMOP symptom 1 | 31 | 4.58 | 9 months | 31 | 4.1 | p > 0.05 | |

| MYMOP symptom 2 | 25 | 3.92 | 9 months | 25 | 3.48 | p > 0.05 | |

| MYMOP activity 1 | 27 | 4.67 | 9 months | 27 | 4.26 | p > 0.05 | |

| MYMOP wellbeing | 31 | 4.13 | 9 months | 31 | 3.71 | p > 0.05 | |

| MYMOP profile | 31 | 4.45 | 9 months | 31 | 3.94 | p > 0.05 | |

| Greasley (2003)[95] | SF36 physical functioning | 22 | 39.09 | 6 months | 22 | 48.64 | p > 0.05 |

| SF36 physical functioning | 22 | 39.09 | 12 months | 22 | 57.50 | p > 0.05 | |

| SF36 role functioning physical | 22 | 30.11 | 6 months | 22 | 36.36 | p > 0.05 | |

| SF36 role functioning physical | 22 | 30.11 | 12 months | 22 | 40.34 | p > 0.05 | |

| SF36 bodily pain | 22 | 30.45 | 6 months | 22 | 25.91 | p > 0.05 | |

| SF36 bodily pain | 22 | 30.45 | 12 months | 22 | 29.18 | p > 0.05 | |

| SF36 general health | 22 | 22.90 | 6 months | 22 | 31.09 | p < 0.002 | |

| SF36 general health | 22 | 22.90 | 12 months | 22 | 33.59 | p < 0.076 | |

| SF36 vitality | 22 | 25.28 | 6 months | 22 | 26.98 | ANOVA across 3 time points, p < 0.079 | |

| SF36 vitality | 22 | 25.28 | 12 months | 22 | 33.52 | ||

| SF36 social functioning | 22 | 34.09 | 6 months | 22 | 43.75 | ANOVA across 3 time points, p < 0.077 | |

| SF36 social functioning | 22 | 34.09 | 12 months | 22 | 43.75 | ||

| SF36 role functioning emotional | 22 | 34.85 | 6 months | 22 | 47.72 | p > 0.05 | |

| SF36 role functioning emotional | 22 | 34.85 | 12 months | 22 | 39.77 | p > 0.05 | |

| SF36 mental health | 22 | 37.14 | 6 months | 22 | 42.85 | p > 0.05 | |

| SF36 mental health | 22 | 37.14 | 12 months | 22 | 47.86 | p < 0.076 | |

| Greasley (2003)[95] cont. | HADS anxiety | 22 | 13.31 | 6 months | 22 | 11.73 | ANOVA across 3 time points, p < 0.051 |

| HADS anxiety | 22 | 13.31 | 12 months | 22 | 11.36 | ||

| HADS depression | 22 | 10.59 | 6 months | 22 | 10.41 | p > 0.05 | |

| HADS depression | 22 | 10.59 | 12 months | 22 | 9.59 | p > 0.05 | |

| Veitch (1995) – GP[21] | NHP total score | 52 | Not reported | 6 months | 52 | Not reported | p-0.6344 |

| NHP energy | 52 | Not reported | 6 months | 52 | Not reported | p = 0.3970 | |

| NHP pain | 52 | Not reported | 6 months | 52 | Not reported | p = 0.8368 | |

| NHP emotional reactions | 52 | Not reported | 6 months | 52 | Not reported | p = 0.4249 | |

| NHP sleep | 52 | Not reported | 6 months | 52 | Not reported | p = 0.3138 | |

| NHP social isolation | 52 | Not reported | 6 months | 52 | Not reported | p = 0.9011 | |

| NHP physical mobility | 52 | Not reported | 6 months | 52 | Not reported | p = 0.8489 | |

| Veitch (1995) – mental health[21] | NHP total score | 52 | Not reported | 6 months | 52 | Not reported | p = 0.1084 |

| NHP energy | 52 | Not reported | 6 months | 52 | Not reported | p = 0.3359 | |

| NHP pain | 52 | Not reported | 6 months | 52 | Not reported | p = 0.0127 | |

| NHP emotional reactions | 52 | Not reported | 6 months | 52 | Not reported | p = 0.0333 | |

| NHP sleep | 52 | Not reported | 6 months | 52 | Not reported | p = 0.1309 | |

| NHP social isolation | 52 | Not reported | 6 months | 52 | Not reported | p = 0.8928 | |

| NHP physical mobility | 52 | Not reported | 6 months | 52 | Not reported | p = 0.2061 | |

*comparison of follow up versus baseline score; SF36 = short form 36; MYMOP = Measure Yourself Medical Outcome Profile scale; HADS = Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; NHP = Nottingham Health Profile

Seven studies reported health and social results using in-house questionnaires with little evidence of validation. These are summarised in Table 8. These studies found consistently high levels of clients agreeing with statements concerning the positive impact of the advice on their health, quality of life and living situations.

Table 8.

Quantitative non-scalar health and social outcomes, studies without a control or comparison group (studies included in the review)

| Authors (date) | Sample size and composition | Sample selection strategy | Data collection method | Summary of results |

| Abbott & Hobby (1999)[79] | 48 clients | all clients whose income increased as a result of the advice | structured interview | 69% felt increase in income "affected how they felt about life and/or that their health had improved" |

| Borland (2004)[83, 84] | 1088 clients | all clients asked to complete questionnaire | postal questionnaire | 88% felt better after seeing the advice worker |

| Broseley Health and Advice Partnership (2004)[86] | unspecified number of clients | not reported | postal questionnaire | 100% "felt less worried or stressed" following the advice 75% "had more money to buy food or provide heating" following the advice 75% "felt better in themselves" following the advice |

| Hastie (2003)[98] | 86 clients | not reported | postal questionnaire | 87% thought the service "made a positive difference to them" 83% "felt less worried, calmer and supported" following the advice 60% "felt their health had improved" following the advice 53% "felt that their housing situation had improved" following the advice |

| Lishman-Peat & Brown (2002)[105] | 34 clients | not reported | structured interview | 73% "felt happier having been helped by ad advisor, even if that help did not result in extra income" |

| Sedgefield and district AIS (2004)[113] | 33 clients | not reported | postal questionnaire | 73% felt advice had "improved quality of life" |

| Vaccarello (2004)[115] | unspecified number of clients | 10% random sample of clients invited to take part | postal questionnaire | 98% felt service "had improved their quality of life" 91% said the service "had helped them to keep independent and remain in their own home" 83% "felt they were able to manage more safely in their homes" following the advice 77% felt they "cope better with their day-to-day living" following the advice |

| Ferguson & Simmons[93] | unspecified number of clients | not reported | not reported | 46% felt "less anxious or worried" after seeing the advisor 11% "reported an improvement in their health" 13% "reported that they could now afford a better diet" 13% "stated that they could afford increased heating" as a result of the advice |

Health and social outcomes – qualitative studies

Aspects of the qualitative investigations within studies included in the review are summarised in Table 9. The 14 studies that reported qualitative data collected information from a variety of individuals including those who received advice, advice givers and primary care staff. Sample sizes ranged from six to 41. In 12 of the 14 (86%) studies, data were collected via interviews with participants whilst questionnaires were relied on in two (14%) cases. Six of 12 (50%) studies that reported a rationale for participant selection, gave a theoretical reason for participant selection, rather than reporting that selection was random, opportunistic or just those who responded to a postal questionnaire. The analytical approach used for drawing results from the data was reported in 10 (71%) cases.

Table 9.

Quality of qualitative studies (studies included in the review)

| Authors (date) | Sample Size | Sample composition | Sample selection strategy | Data collection method | Analytical method |

| Abbott & Hobby (2002)[34] | 6 | clients | illustrative of "complex interactions between social situation, income and health" | interviews | development of case studies |

| Actions (2004)[81] | Not stated | clients | Not stated | questionnaire with free text | non stated – verbatim reporting of free text comments |

| Bowran (1997)[85] | 25 | 17 successful claimants, 7 unsuccessful claimants | all those seen in 1996 invited to take part, 43 consented, purposefully sampled | unstructured interviews | grounded theory |

| Emanuel & Begum (2000)[90] | 10 | 10 clients | 5 users whose HADS/MYMOP improved, 5 users whose HADS/MYMOP didn't improve/worsened | semi-structured interviews | thematic analysis |

| Farmer & Kennedy (2001)[91] | 8 | 4 clients after advice given, 4 clients before and after advice given | clients seen after chosen by random selection, clients seen before and after approached in waiting room and asked to take part | semi-structured interviews | development of case studies and inductive thematic analysis |

| Fleming & Golding (1997)[92] | 27 | clients | all clients who gave consent | semi-structured interviews | not stated – description of apparently important areas reported |

| Galvin et al (2000)[67, 94] | 10 | clients | service users those with multiple and complex needs | "focused interviews" | illuminative evaluation, thematic content analysis |

| Knight (2002)[103] | 28 | service users | not stated | focus groups and telephone unstructured interviews | thematic analysis |

| MacMillan & CAB Partnership (2004)[106] | 38 | clients | Those clients who gave permission to be contacted for research | telephone interview | not stated – verbatim reporting of comments given |

| Moffatt et al (2004)[70] | 11 | all white, 7 women, age range 46–76 years, all unemployed/retired/unable to work, all chronic health problems, 8 never used welfare advice before | purposeful of those who benefited financially | semi-structured interviews | establish analytical categories, grouping into overarching key themes |

| Moffatt (2004)[109] | 25 | 14 in intervention arm, 14 female, mean age 75 | purposeful to get those who did and didn't receive intervention and those who did and didn't benefit financially | semi-structured interviews | development of conceptual framework and thematic charting |

| Reading et al (2002)[72] | 10 | 5 service users and 5 non-service users who were eligible and expressed debt concerns at start of project | random selection of two groups represented | semi-structure interviews | modified grounded theory with more descriptive approach |

| Sherratt et al (2000)[77] | 41 | 13 patients | 4 patients randomly chosen per month and invited to take part | semi-structured interviews with clients, focus groups with staff | thematic analysis |

| Woodcock (2004)[117] | Not stated | clients | all clients seen sent satisfaction questionnaire | postal questionnaire with free text | not stated – verbatim reporting of few text comments |

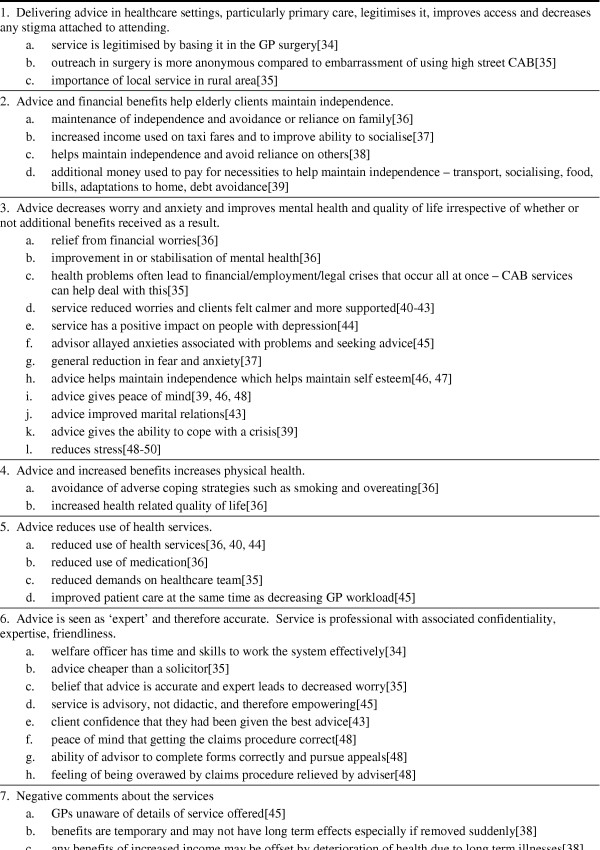

Some of the common themes identified in the qualitative results are listed in Box 4 (see Figure 4). Money gained as a result of the advice was commonly reported as being spent on healthier food, avoidance of debt, household bills, transport and socialising. A number of negative issues concerning the advice were raised, primarily by general practitioners. These included the suggestion that the health benefits of increased welfare benefits may be temporary or offset by ongoing, irreversible, health deterioration.

Figure 4.

Box 4. Common areas identified in qualitative work.

Financial outcomes

Data on either lump sums (generally back dated payments and arrears for the period between claim submission and claim approval) or recurring benefits or both gained as a result of the advice were reported in 28 cases (51%). Financial data from these studies are summarised in Table 10. Although a number of other studies reported some information on financial outcomes, this was often given as a combined figure of both lump sum payments and recurring benefits – making comparisons difficult. Furthermore, the specific benefits gained for clients was inconsistently reported and are not, therefore, reported here. The studies reporting analysable financial data gained a mean of £194 (US$353, €283) lump sum plus £832 (US$1514, €1215) per year in recurring benefits per client seen – a total of £1026 (US$1867, €1498) in the first year following the advice per client seen. As, the number of successful claimants was only reported in 17 (59%) cases where all other financial data were reported, we have not reported gains per successful claimant. As the number of successful claimants is likely to be less than the total number of clients seen, the actual financial benefit to those who successfully claimed is likely to be greater than the figures summarised here. Furthermore, a number of authors stated that their data did not include the outcomes of claims or appeals still pending at the time of reporting, making the definitive amount gained as a result of advice likely to be greater still.

Table 10.

Quantitative financial outcomes (studies included in review where data provided)

| Authors (date) | Number of clients seen | Total lump sum/one off payments gained | Mean lump sum/one off payments per client seen | Recurring benefits gained (per year) | Mean recurring benefits (per year) per client seen |

| Bennett (1997)[82] | 49 | £28 121.00 | £573.898 | £41 860.00 | £854.29 |

| Bundy (2002)[87] | 561 | £183 147.00 | £326.47 | £762 042.00 | £1358.36 |

| Bundy (2003)[88] | 818 | £261 231.00 | £319.35 | £474 587.00 | £580.18 |

| Coppell et al (1999)[43] | 270 | £15 863.00 | £58.75 | £28 028.00 | £103.81 |

| Cornwallis & O;Neill (1997)[65] | 102 | £66 785.00 | £654.75 | not reported | not reported |

| Derbyshire CC WRS (1997)[89] | 428 | £73 643.07 | £172.06 | £527 352.90 | £1232.13 |

| Derbyshire CC WRS (1998a)[22] | 480 | £117 405.20 | £244.59 | £573 995.20 | £1195.82 |

| Derbyshire CC WRS (1998b)[22] | 290 | £56 967.87 | £196.44 | £374 630.40 | £1291.83 |

| Frost-Gaskin et al (2003)[66] | 153 | £60 323.34 | £394.27 | £281 805.80 | £1841.87 |

| Greasley (2003)[95] & Greasley and Small (2005)[96] | 2484 | £431 198.00 | £173.59 | £1 940 543.00 | £781.22 |

| Griffiths (1992)[97] | 157 | £32 708.00 | £208.33 | £87 131.20 | £554.98 |

| Hastie (2003)[98] | 492 | £39 688.00 | £80.67 | £173 108.00 | £351.85 |

| High Peak CAB (1995)[99] | 39 | not reported | not reported | £38 646.40 | £990.93 |

| High Peak CAB (2001)[100] | 236 | £9 069.74 | £38.43 | £24 934.52 | £105.65 |

| High Peak CAB (2003)[101] | 156 | £4765.63 | £30.55 | £60 201.96 | £385.91 |

| Hoskins et al (in press)[102] | 630 | £119 515.44 | £189.71 | £1 016 908.70 | £1 614.14 |

| Memel & Gubbay (1999)[57] | 46 | not reported | not reported | £73 872.00 | £1605.91 |

| Memel et al (2002)[24] | 19 | not reported | not reported | £38 725.00 | £2038.16 |

| Middlesbrough WR (1999)[107] | 272 | not reported | not reported | £473 053.00 | £1739.17 |

| Middleton et al (1993a)[69] | 52 | £10 393.00 | £199.87 | £14 359.00 | £276.13 |

| Middleton et al (1993b)[69] | 583 | £12 559.80 | £21.54 | £8 373.20 | £14.36 |

| Moffatt (2004)[109] | 25 | £5 766.00 | £230.64 | £37 442.08 | £1497.68 |

| Paris & Player (1993)[71] | 150 | £3 371.00 | £22.47 | £54 929.58 | £366.20 |

| Reading et al (2002)[72] | 23 | £4 389.00 | £190.83 | £6 480.00 | £281.74 |

| Southwark CC MAC (1998)[114] | 621 | £160 593.00 | £258.60 | £390 500.00 | £628.82 |

| Vaccarello (2004)[115] | 206 | £11 433.00 | £55.50 | £137 819.00 | £669.02 |

| Veitch (1995)[21] – mental health | 35 | £16 122.90 | £460.65 | £25 581.40 | £730.90 |

| Veitch (1995)[21] – GP | 37 | £28 783.69 | £777.94 | £74 025.64 | £2000.69 |

| Widdowfield & Rickard (1996)[116] | 106 | not reported | not reported | £183 790.20 | £1733.87 |

| Totals | £1 753 843 and 9038 clients, mean = £194 per client | £7 864 910 and 9418 clients, mean = £832 per year per client | |||

CAB = Citizen's Advice Bureau

Discussion

Summary of results

We found 55 studies reporting on the health, social and economic impact of welfare advice delivered in healthcare settings. The majority of these studies were grey literature, not published in peer reviewed journals, and were of limited scientific quality: full financial data were only reported in 50% of cases, less than 10% of studies used a control or comparison group to assess the impact of the advice, and qualitative approaches did not always reflect best practice. Only one study – based in the USA – included in the review was not UK based.

Amongst those studies included in the review, most welfare rights advice was delivered by CAB workers or local government welfare rights officers, most advice was delivered in primary care with around a third of studies offering advice in clients' homes. Few studies had restrictive eligibility criteria or referral procedures.

There was evidence that welfare rights advice delivered in healthcare settings leads to worthwhile financial benefits with a mean financial gain of £1026 per client seen in the year following advice amongst those studies reporting full financial data. This equates to around 9% of average individual gross income in the UK in 1999–2001[32]. However, this is by no means a precise estimate of typical gains: there was considerable variation in the gains reported and many studies identified that their data were incomplete with a number of claims still 'pending'.

Studies that included control or comparison groups tended to use non-specific measures of general health (e.g. SF36, NHP and HADS) and found few statistically significant differences between intervention and control or comparison groups. However, sample sizes were often small and follow up limited to a maximum of 12 months – likely to be too short a period to detect changes in health following changes in financial circumstances. Where statistically significant results were found, these tended to be in relation to measures of psychological or social, rather than physical, health. Qualitative methods were commonly used to assess both clients' and staff's perceptions of the impact of the advice. The advice was generally welcomed with extra money gained as a result of the advice commonly reported as being spent on household necessities and social activities.

Limitations of review methods

The majority of the studies included in this review were grey literature not published in peer reviewed journals and were accessed via requests for information sent to email distribution lists. Although often of limited scientific quality, we included these studies in our review as they often included legitimate data on financial benefits of the intervention and let us describe the current scope of welfare rights advice as far as possible. Because grey literature is not comprehensively indexed, it is hard to be sure that we accessed all that is available, despite our use of a systematic approach to both literature searching and data abstraction[17]. In particular, we collected very little information from non-UK settings, despite sending requests for information to a number of international distribution lists. Whilst welfare rights advice may be rare outside the UK, it is also possible that it is described differently in different contexts and that the vocabulary used in our requests for information had little meaning for those outside the UK. We did not conduct searches of non-English language electronic databases or place posts in other languages to international email distribution lists. These additional techniques may have revealed additional relevant work from outside the UK.

The variations and limitations of methods used by the studies included in this review meant that it was inappropriate to perform formal meta-analysis. Similarly, limitations in data availability prevented us from performing potentially interesting comparisons of the cost of providing welfare rights advice versus the financial benefits gained for clients. The interpretation of our findings and conclusions that can be drawn are, therefore, more subjective than might be the case in other systematic reviews. In order to confirm that we were using the best possible methods, we considered performing our review under the umbrella of one of the evidence and review collaborations. However, there was no obvious appropriate review group within the Cochrane Collaboration for this sort of work. The Campbell Collaboration supports systematic reviews of behavioural, social and educational interventions but were unwilling to consider inclusion of any uncontrolled studies in our review. Although this would undoubtedly have increased the overall quality of studies included, we felt it would have led to a review that was not representative of the evidence base – which is largely of poor scientific quality, as described here. This problem has been previously described[12].

Interpretation of results

Our review supports previous findings that the provision of welfare rights advice in healthcare settings is increasingly common in the UK[14,15] – although as these are non-statutory services, coverage is inevitable patchy. However, there was also some evidence that similar programmes can be provided in other settings with one study from the USA included in the review[23]. Whilst we have found substantial evidence that welfare rights advice in healthcare settings leads to financial benefits, there is little evidence that the advice leads to measurable health and social benefits. This is primarily due to absence of good quality evidence, rather than evidence of absence of an effect.

Whilst some sort of evaluation of welfare rights advice programmes is commonplace, the scientific rigour of these evaluations appears to be limited. Many of these advice services appear to operate in conditions of limited resources. Although performing some sort of evaluation of their service is frequently a requirement of funding, additional resources to support such evaluation and the skills to conduct it rigorously are scarce.

Implications for policy, practice and research

There is now substantial evidence that welfare rights advice delivered in healthcare settings leads to financial benefits for clients – although typical levels cannot be precisely estimated. There is little need to conduct additional work to determine whether such advice has a financial effect, although further work is required to explore the characteristics of those most likely to benefit financially in order that such advice can be effectively targeted.