Abstract

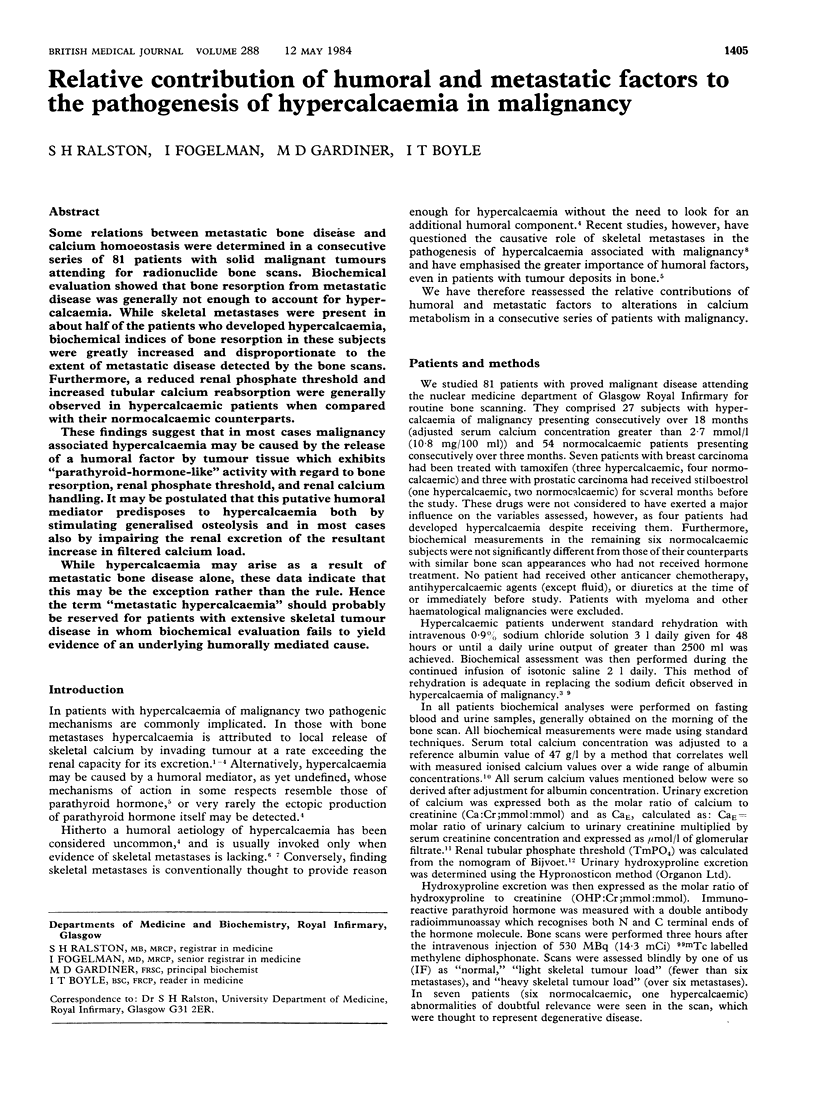

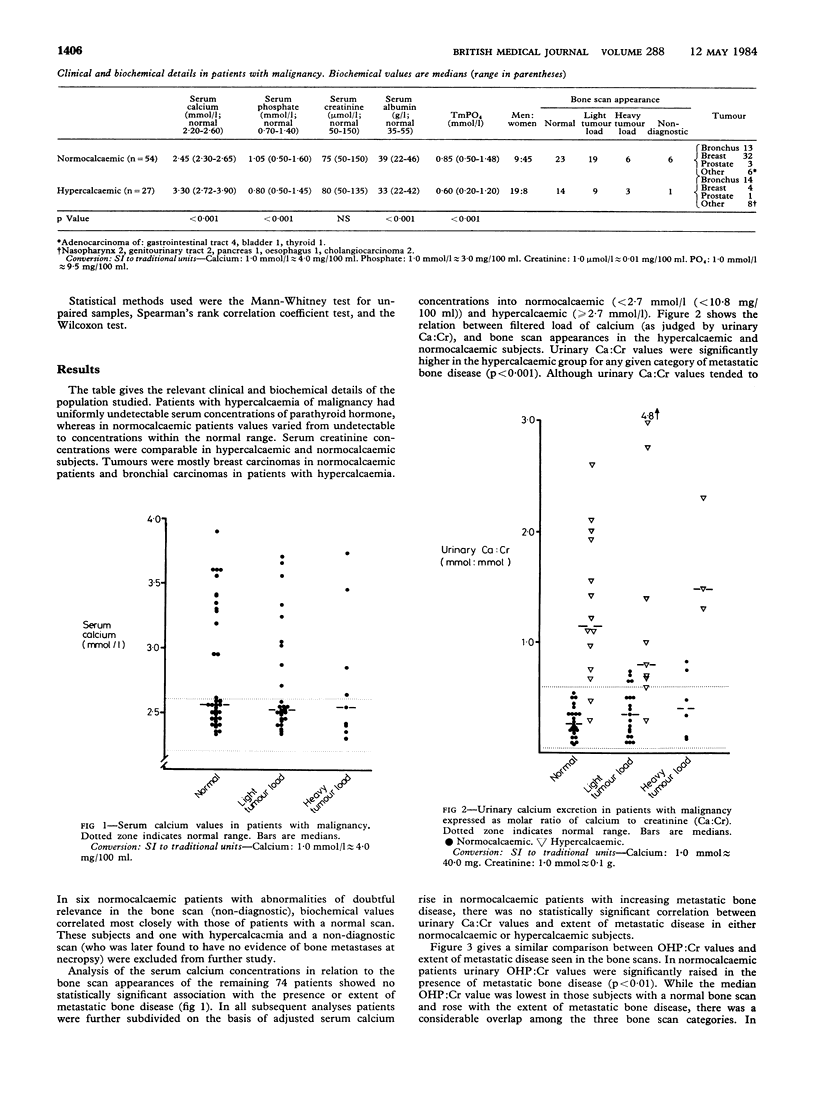

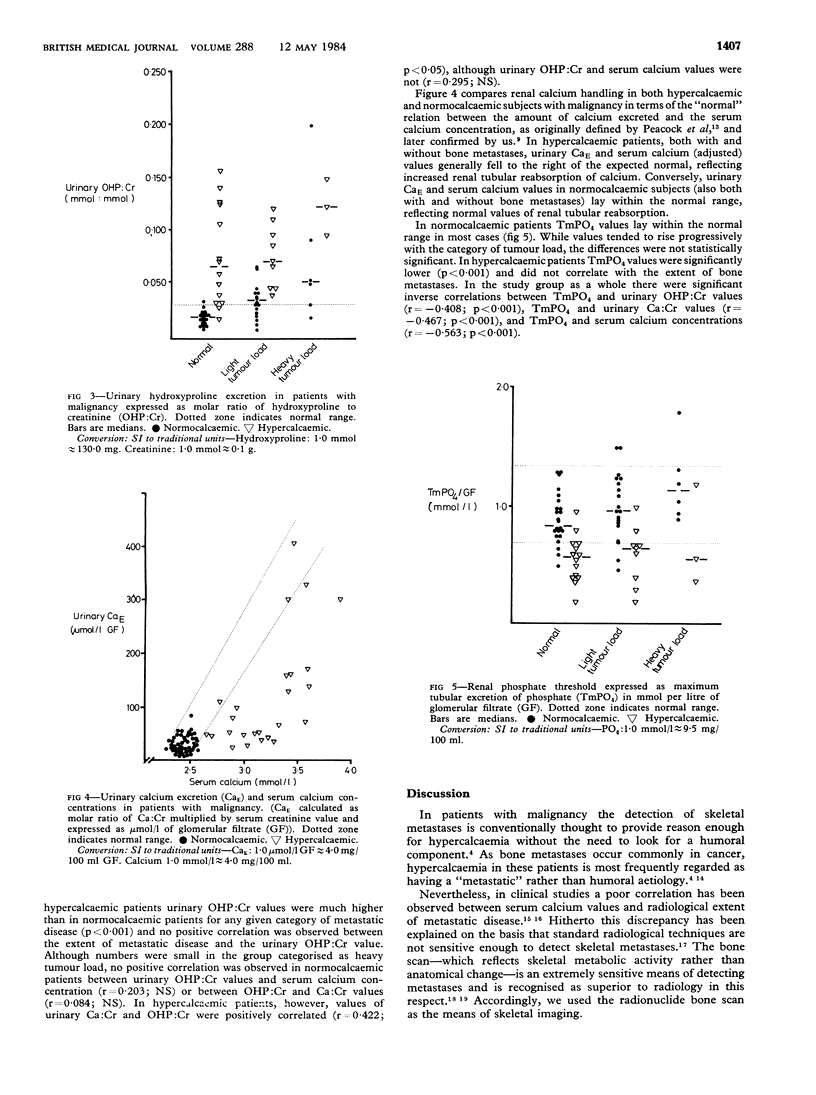

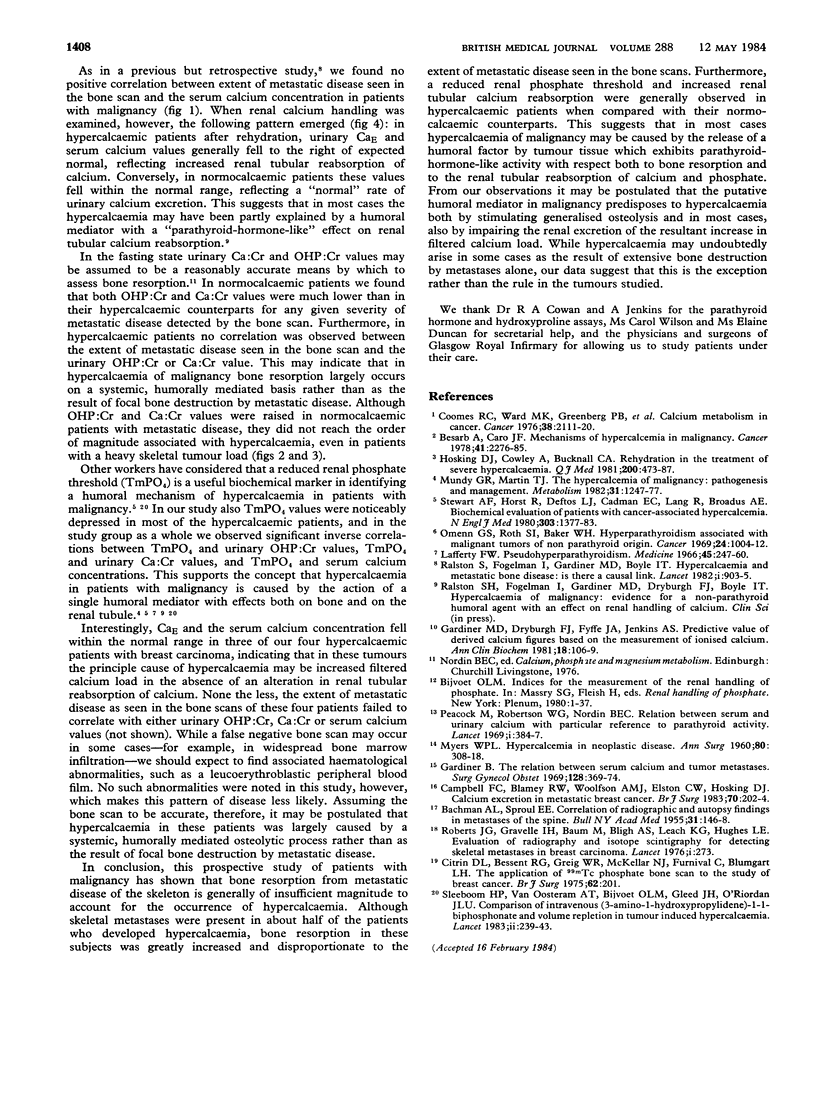

Some relations between metastatic bone disease and calcium homoeostasis were determined in a consecutive series of 81 patients with solid malignant tumours attending for radionuclide bone scans. Biochemical evaluation showed that bone resorption from metastatic disease was generally not enough to account for hypercalcaemia. While skeletal metastases were present in about half of the patients who developed hypercalcaemia, biochemical indices of bone resorption in these subjects were greatly increased and disproportionate to the extent of metastatic disease detected by the bone scans. Furthermore, a reduced renal phosphate threshold and increased tubular calcium reabsorption were generally observed in hypercalcaemic patients when compared with their normocalcaemic counterparts. These findings suggest that in most cases malignancy associated hypercalcaemia may be caused by the release of a humoral factor by tumour tissue which exhibits "parathyroid-hormone-like" activity with regard to bone resorption, renal phosphate threshold, and renal calcium handling. It may be postulated that this putative humoral mediator predisposes to hypercalcaemia both by stimulating generalised osteolysis and in most cases also by impairing the renal excretion of the resultant increase in filtered calcium load. While hypercalcaemia may arise as a result of metastatic bone disease alone, these data indicate that this may be the exception rather than the rule. Hence the term "metastatic hypercalcaemia" should probably be reserved for patients with extensive skeletal tumour disease in whom biochemical evaluation fails to yield evidence of an underlying humorally mediated cause.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Besarab A., Caro J. F. Mechanisms of hypercalcemia in malignancy. Cancer. 1978 Jun;41(6):2276–2285. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197806)41:6<2276::aid-cncr2820410628>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell F. C., Blamey R. W., Woolfson A. M., Elston C. W., Hosking D. J. Calcium excretion (CaE) in metastatic breast cancer. Br J Surg. 1983 Apr;70(4):202–204. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800700405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Citrin D. L., Bessent R. G., Greig W. R., McKellar N. J., Furnival C., Blumgart L. H. The application of the 99Tcm phosphate bone scan to the study of breast cancer. Br J Surg. 1975 Mar;62(3):201–204. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800620307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coombes R. S., Ward M. K., Greenberg P. B., Hillyard C. J., Tulloch B. R., Morrison R., Joplin G. F. Calcium metabolism in cancer. Studies using calcium isotopes and immunoassays for parathyroid hormone and calcitonin. Cancer. 1976 Nov;38(5):2111–2120. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197611)38:5<2111::aid-cncr2820380539>3.0.co;2-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner B. The relation between serum calcium and tumor metastases. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1969 Feb;128(2):369–374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner M. D., Dryburgh F. J., Fyffe J. A., Jenkins A. S. Predictive value of derived calcium figures based on the measurement of ionised calcium. Ann Clin Biochem. 1981 Mar;18(Pt 2):106–109. doi: 10.1177/000456328101800210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosking D. J., Cowley A., Bucknall C. A. Rehydration in the treatment of severe hypercalcaemia. Q J Med. 1981 Autumn;50(200):473–481. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lafferty F. W. Pseudohyperparathyroidism. Medicine (Baltimore) 1966 May;45(3):247–260. doi: 10.1097/00005792-196605000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MYERS W. P. Hypercalcemia in neoplastic disease. Arch Surg. 1960 Feb;80:308–318. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1960.01290190128024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mundy G. R., Martin T. J. The hypercalcemia of malignancy: pathogenesis and management. Metabolism. 1982 Dec;31(12):1247–1277. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(82)90012-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omenn G. S., Roth S. I., Baker W. H. Hyperparathyroidism associated with malignant tumors of nonparathyroid origin. Cancer. 1969 Nov;24(5):1004–1011. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(196911)24:5<1004::aid-cncr2820240520>3.0.co;2-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peacock M., Robertson W. G., Nordin B. E. Relation between serum and urinary calcium with particular reference to parathyroid activity. Lancet. 1969 Feb 22;1(7591):384–386. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(69)91353-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ralston S., Fogelman I., Gardner M. D., Boyle I. T. Hypercalcaemia and metastatic bone disease: is there a causal link? Lancet. 1982 Oct 23;2(8304):903–905. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(82)90868-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sleeboom H. P., Bijvoet O. L., van Oosterom A. T., Gleed J. H., O'Riordan J. L. Comparison of intravenous (3-amino-1-hydroxypropylidene)-1, 1-bisphosphonate and volume repletion in tumour-induced hypercalcaemia. Lancet. 1983 Jul 30;2(8344):239–243. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(83)90231-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart A. F., Horst R., Deftos L. J., Cadman E. C., Lang R., Broadus A. E. Biochemical evaluation of patients with cancer-associated hypercalcemia: evidence for humoral and nonhumoral groups. N Engl J Med. 1980 Dec 11;303(24):1377–1383. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198012113032401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]