Abstract

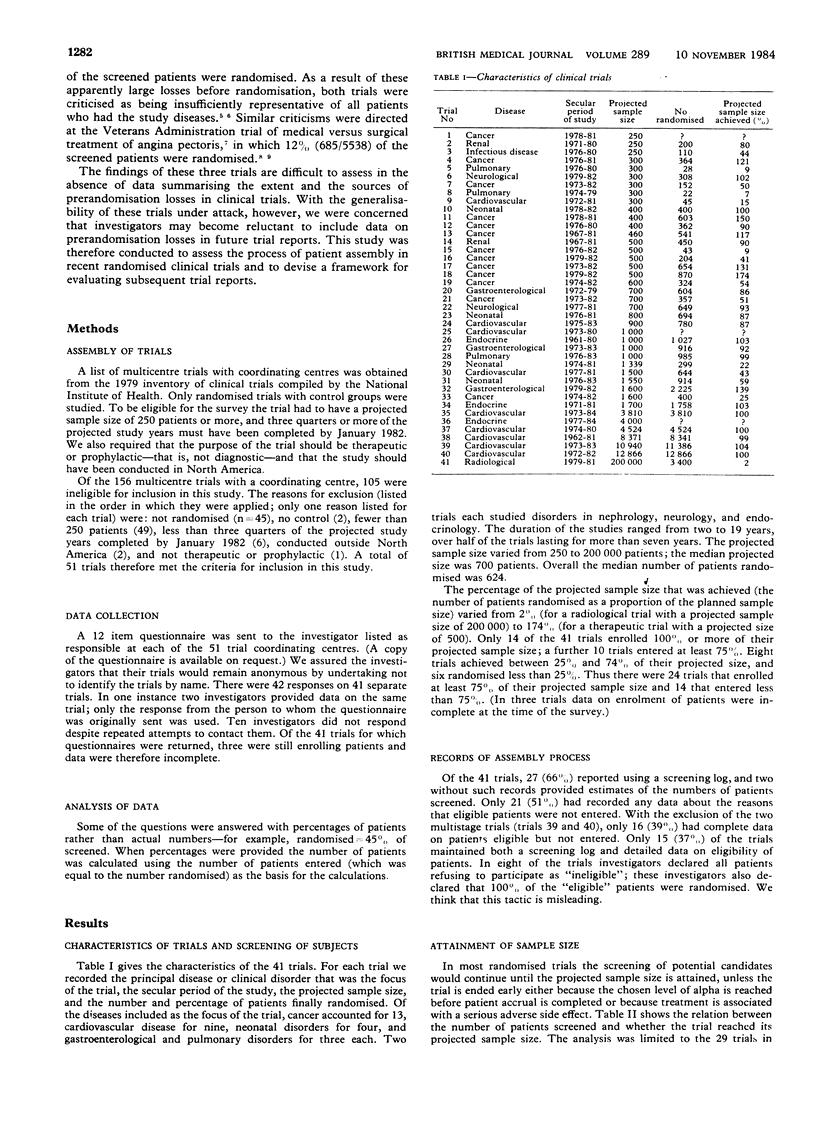

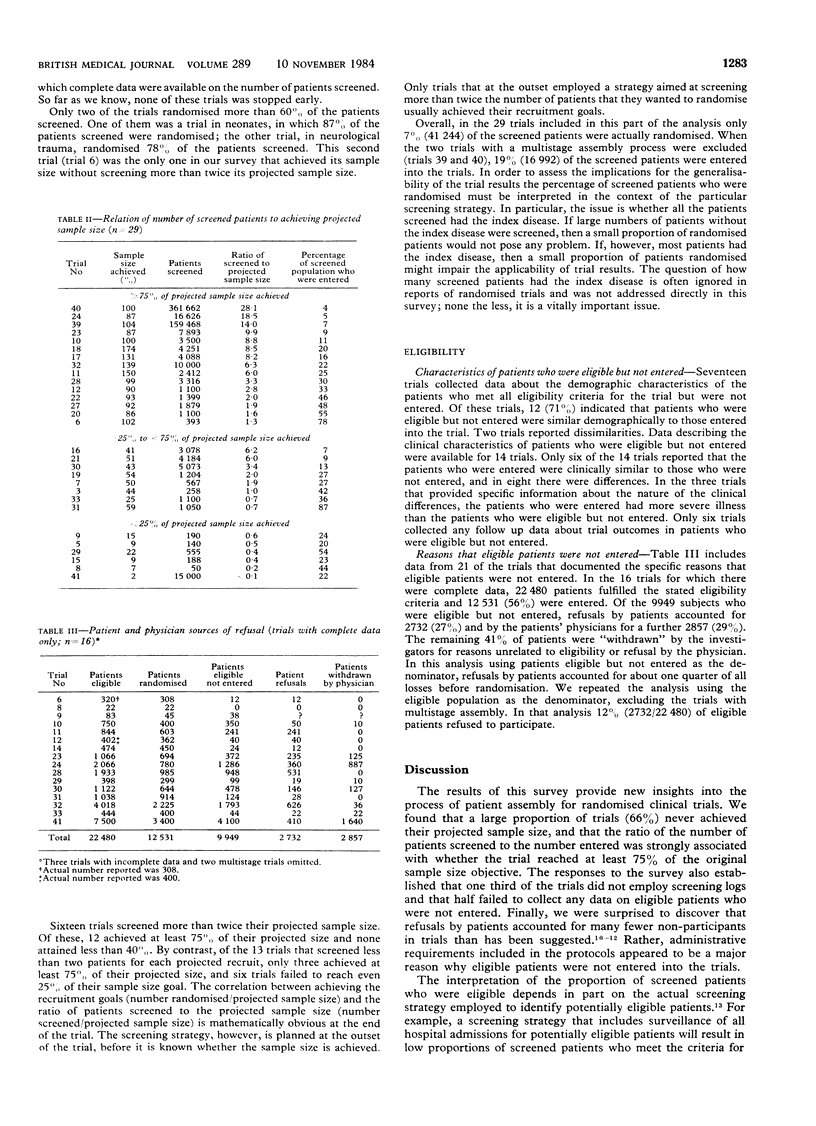

The problem of generalisability in randomised clinical trials was highlighted by studies that entered only 10-14% of screened patients. To determine the magnitude and source of prerandomisation losses in clinical trials a survey was conducted of 41 trials listed in the 1979 inventory of the National Institute of Health. Two thirds of the trials maintained screening logs, but only half maintained any records of the number of patients who met the eligibility criteria but were not entered into the trial. Among 21 trials (51%) that kept data on the number of patients who were eligible but not entered, losses of eligible subjects were attributable to refusals by patients in 25% and refusals by physicians in 29%. Other protocol requirements accounted for the remaining losses of eligible patients. Only a few trials documented the characteristics of patients who were eligible but not entered; in those trials the patients who were not entered were similar demographically but differed clinically from those enrolled. Thus minimising prerandomisation losses of eligible patients requires the use of less restrictive criteria for entering patients. Twenty four of the trials achieved 75% or more of their recruitment goals, eight between 25% and 74%, and six less than 25%. Among trials that screened less than twice their projected sample size, only three out of 13 (23%) achieved 75% or more of their recruitment goal. By contrast, 12 out of 16 trials (75%) that screened more than twice their projected sample size achieved 75% or more of their recruitment goal. Screening large numbers of patients appears to be a pragmatic requirement for success in achieving recruitment goals; therefore, trials should not be criticised as lacking generalisability on that basis alone. The number and characteristics of eligible patients who were not entered, however, were documented by only a few trials; these data are critical in the assessment of generalisability. Additionally, the number of patients with the index disease who did not meet the eligibility criteria should also be documented. Together, these two types of data characterise the population to whom the trial results may be applied.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Bergstrand R., Vedin A., Wilhelmsson C., Wilhelmsen L. Bias due to non-participation and heterogenous sub-groups in population surveys. J Chronic Dis. 1983;36(10):725–728. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(83)90166-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conn H. O., Lindenmuth W. W., May C. J., Ramsby G. R. Prophylactic portacaval anastomosis. Medicine (Baltimore) 1972 Jan;51(1):27–40. doi: 10.1097/00005792-197201000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Criqui M. H., Barrett-Connor E., Austin M. Differences between respondents and non-respondents in a population-based cardiovascular disease study. Am J Epidemiol. 1978 Nov;108(5):367–372. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fost N. Sounding Board. Consent as a barrier to research. N Engl J Med. 1979 May 31;300(22):1272–1273. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197905313002212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gore S. M. Assessing, clinical trials-- protocol and monitoring. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1981 Aug 1;283(6287):369–371. doi: 10.1136/bmj.283.6287.369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenland S. Response and follow-up bias in cohort studies. Am J Epidemiol. 1977 Sep;106(3):184–187. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenlick M. R., Bailey J. W., Wild J., Grover J. Characteristics of men most likely to respond to an invitation to be screened. Am J Public Health. 1979 Oct;69(10):1011–1015. doi: 10.2105/ajph.69.10.1011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hampton J. R. Presentation and analysis of the results of clinical trials in cardiovascular disease. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1981 Apr 25;282(6273):1371–1373. doi: 10.1136/bmj.282.6273.1371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson F. C., Perrin E. B., Smith A. G., Dagradi A. E., Nadal H. M. A clinical investigation of the portacaval shunt. II. Survival analysis of the prophylactic operation. Am J Surg. 1968 Jan;115(1):22–42. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(68)90127-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loop F. D., Proudfit W. L., Sheldon W. C. Coronary bypass surgery weighed in the balance. Am J Cardiol. 1978 Jul;42(1):154–156. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(78)91001-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell J. R. Timolol after myocardial infarction: an answer or a new set of questions? Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1981 May 16;282(6276):1565–1570. doi: 10.1136/bmj.282.6276.1565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sackett D. L., Gent M. Controversy in counting and attributing events in clinical trials. N Engl J Med. 1979 Dec 27;301(26):1410–1412. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197912273012602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whisnant J. P. The Canadian trial of aspirin and sulfinpyrazone in threatened stroke. Am Heart J. 1980 Jan;99(1):129–130. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(80)90323-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zelen M. A new design for randomized clinical trials. N Engl J Med. 1979 May 31;300(22):1242–1245. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197905313002203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]