Abstract

THO/TREX is a conserved, eukaryotic protein complex operating at the interface between transcription and messenger ribonucleoprotein (mRNP) metabolism. THO mutations impair transcription and lead to increased transcription-associated recombination (TAR). These phenotypes are dependent on the nascent mRNA; however, the molecular mechanism by which impaired mRNP biogenesis triggers recombination in THO/TREX mutants is unknown. In this study, we provide evidence that deficient mRNP biogenesis causes slowdown or pausing of the replication fork in hpr1Δ mutants. Impaired replication appears to depend on sequence-specific features since it was observed upon activation of lacZ but not leu2 transcription. Replication fork progression could be partially restored by hammerhead ribozyme-guided self-cleavage of the nascent mRNA. Additionally, hpr1Δ increased the number of S-phase but not G2-dependent TAR events as well as the number of budded cells containing Rad52 repair foci. Our results link transcription-dependent genomic instability in THO mutants with impaired replication fork progression, suggesting a molecular basis for a connection between inefficient mRNP biogenesis and genetic instability.

Genetic instability of a DNA fragment can be induced by transcription, a phenomenon referred to as transcription-associated recombination (TAR). Recombination has been shown to increase in actively transcribed genes in bacteria, yeasts, and humans (1). This is the case for RNA polymerase II (RNAPII)-dependent transcription, as first shown for yeast (43). Despite the ubiquity and relevance of TAR, its mechanism(s) remains unknown. Transcription-dependent hyperrecombination is a hallmark phenotype of mutants of the THO complex in the yeast S. cerevisiae (4, 36). THO is a conserved, eukaryotic multiprotein complex, containing Hpr1, Mft1, Tho2, and Thp2 in yeast (5). Moreover, THO acts at the interface between transcription and mRNP export via its interaction with Sub2 and Yra1 in a high-molecular-weight complex termed TREX (19, 40). THO/TREX components are recruited to an active gene during transcription elongation. Hpr1 directly interacts with Sub2 and facilitates the binding of Sub2 and Yra1 to nascent transcripts (46). Mutations in most factors involved in messenger RNP (mRNP) biogenesis and export, including Sub2, Yra1, Thp1-Sac3, Nab2, Mex67, and Mtr2, confer a gene expression defect and a transcription-dependent hyperrecombination phenotype comparable to that described for THO mutant strains (10, 19). The similarity of these phenotypes suggests that correct processing of a number of nuclear steps, leading to export-competent mRNP particles, is important in preventing transcription-dependent genomic instability (29). It remains to be seen whether TAR events stimulated in THO mutants result from the same mechanism(s) as spontaneous TAR events occurring in wild-type cells.

DNA replication occurs during S phase of the cell cycle and is initiated at multiple origins of replication (20). Once established, a single replication fork will replicate several tens of kilobases before meeting a converging fork. Replication forks are vulnerable structures that often encounter obstacles that may cause them to pause or stall. Fork progression can be compromised by exogenous stress, such as DNA damage or inhibitors of DNA replication (16, 37). Blocking (3, 21) and transient pausing (11, 17, 18, 44) of replication fork progression during the normal process of chromosome replication at sites where nonnucleosomal proteins are tightly bound to DNA are well documented. Interestingly, in Schizosaccharomyces pombe, recombination has been shown to be a requirement in promoting cell viability when fork progression is blocked (23).

Transcription might exhibit replication fork-pausing activities due to an interference with RNA polymerase processivity. RNA polymerase I (41) and III (9) transcription machineries exhibit replication fork-pausing (RFP) activities. In S. cerevisiae, Fob1 fork-blocking (RFB) activities present in front of the ribosomal DNA (rDNA) transcription unit prevent the collision of replication and transcription (3) and thereby suppress increased recombination between rDNA copies (41). Although the genome is largely transcribed by RNAPII, RFPs have not been defined in front of mRNA genes. Consequently, either the RNAPII transcription machinery does not form an obstacle for replication, or a mechanism exists to circumvent the encounter of both machineries. With the exception of the recent observation of a defined replication pause in leu2 sequences that correlates with transcription-dependent recombination (35), little is known about replication fork progression through RNAPII-transcribed genes.

Depending on the blocking activity, a temporarily stalled fork might resume DNA synthesis. However, collapsed replication forks have been shown to be rescued by homologous recombination in prokaryotic (7, 34) and eukaryotic (32) cells. Several features suggest mechanistic differences between transcription-dependent hyperrecombination in THO mutants, affected in mRNP biogenesis, and TAR in wild-type cells. Thus, gene conversion and deletion patterns between direct repeats are different in hpr1 and wild-type cells (2); hyperrecombination in hpr1 cells is mediated by the nascent mRNA molecule, whereas there is no evidence for this in wild-type TAR; and hpr1 hyperrecombination is associated with transcription elongation impairment and low mRNA accumulation, whereas there is no evidence for this in wild-type TAR. Despite these differences, we reasoned that recombination in THO mutants could be linked to replication failures occurring at DNA regions that are being actively transcribed. To test this hypothesis, we analyzed the fate of replication forks in hpr1Δ cells. Interestingly, we observed a slowdown of replication fork progression along the transcribed lacZ gene at regions previously shown to be impaired in transcription. Replication fork progression was partially restored by self-cleavage of the mRNA, establishing a link between the aberrant biogenesis of the nascent mRNP and impaired replication progression. We observed an increased number of budded cells containing Rad52-yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) foci. Importantly, hyperrecombination in hpr1Δ requires S-phase transcription but not G2-phase transcription. These results indicate that transcription-dependent genetic instability, associated with impaired mRNP biogenesis, is linked to transcription-dependent replication failures.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and plasmids.

Studies were performed with isogenic wild-type (W303-1A), hpr1::HIS3 (U678-1A), and hpr1::KAN (SCHY58) (U678-1A) yeast strains. The pRWY005 plasmid is an ARS1-based circular yeast plasmid derived from TRURAP (42), in which a 3,759-bp HindIII-KpnI fragment, containing the CYC1-GAL1 chimeric promoter fused to the lacZ gene (derived from pSEZT; J. Svejstrup, South Mimms, United Kingdom), was inserted into a unique EcoRI site. To construct pRW012+, a 346-bp, U3-ribozyme-containing sequence (15) was cloned into the EcoRI site present at the 3′ end of the lacZ open reading frame (ORF) of pRWY005. A single-base mutation (G to C) that avoids self-cleavage at the hammerhead sequence is present in the control construct pRW012−. Plasmid pRWY043 was obtained by replacing a ClaI-SpeI fragment containing the 3′ lacZ sequences of pRW012 with a 938-bp, 3′ leu2 fragment. Note that this fragment was devoid of the leu2 promoter and the 5′ sequences. All other plasmids were centromeric. pWJ1344 contains the Rad52-YFP construct (R. Rothstein, Columbia University). pARSGLB-IN, pARSHLB-IN (35), and pARSBLB-IN are centromeric plasmids containing a 0.6-kb leu2 direct-repeat construct transcribed from the GAL1, HHF2, and CLB2 promoters, respectively. Plasmid pARSBLB-IN was constructed by replacing the SphI-NarI HHF2 promoter from pARSHLB-IN by a PCR-amplified fragment containing the CLB2 promoter. PCR amplification was made with oligonucleotides 5′-CATTAGACGTCGCATGCTATGCTATGATCATTAGTGTTGATG-3′ and 5′-GCGTAGGCGCCGACGTCCTATAAGATCAATGAAGAGAGAGAG-3′. pARSGLlacZ-IN, pARSHLlacZ-IN, and pARSBLlacZ-IN were constructed by inserting a 3-kb BamHI lacZ fragment from pPZ (4) at the BglII site located in between the leu2 repeats of pARSGLB-IN, pARSHLB-IN, and pARSBLB-IN, respectively.

Recombination analysis.

Recombination frequencies were determined as the average value of the median frequencies obtained from four fluctuation tests made with two independent transformants according to standard procedures (2, 24). Six independent colonies were analyzed for each fluctuation test.

Detection of Rad52-YFP.

Rad52-YFP foci from mid-log-phase cells transformed with plasmid pWJ1344 were visualized with a Leica DC 350F microscope as previously described (27). A total of 775 wild-type cells and 653 hpr1Δ cells derived from three independent transformation experiments were analyzed.

DNA isolation, 2D agarose gel, and Southern blot analyses.

Cells (100 ml) were grown overnight to an optical density at 600 nm of 0.2 to 0.3 in synthetic complete medium containing 1% glycerol-lactate and 1% raffinose as a carbon source. After the culture was brought to 1% glucose or 1% galactose, cells were grown for another 3.5 to 4 h prior to DNA isolation. DNA isolation, restriction enzyme digestion, and two-dimensional (2D) gel analysis were performed as described previously (45). Prior to 2D gel analysis, the amount of plasmid DNA was determined to adjust for equal loadings. DNA was transferred onto a Hybond-N+ membrane and subsequently hybridized with a specific probe. Membranes were exposed on a Fuji 3600 phosphorimage system and analyzed using the imaging software supplied. Exposures of 2D gels were normalized with respect to the signal intensity of the descending Y arc corresponding to SacI-SmaI-cleaved replication intermediates. Specific 32P-labeled probes include a 1.2-kb fragment covering ARS1 and part of the 3′ lacZ gene and a 1.5-kb leu2 fragment. To determine the plasmid copy number, total DNA was digested with NsiI, electrophoresed, and hybridized against a 0.6-kb, 32P-labeled probe containing URA3 sequences. This plasmid copy number was calculated as the ratio between the density values of the 5-kb plasmid sequence and the 1.6-kb genomic fragment.

RNA isolation and Northern blot analysis.

RNA was prepared and analyzed by standard procedures (4). As a probe, we used a 32P-labeled, 1.15-kb PCR fragment covering the 3′ end of lacZ.

RESULTS

Replication fork progression along transcribed lacZ sequences is retarded in hpr1Δ mutants.

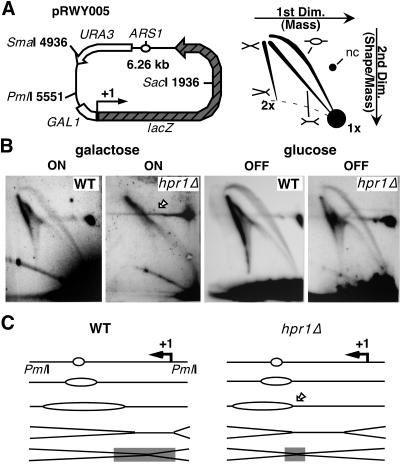

Replication was studied in the yeast multicopy plasmid pRWY005 containing lacZ under the control of the inducible GAL1 promoter (Fig. 1A, left). Bidirectional replication is initiated from a single ARS1 origin of replication, encountering the transcription machineries along lacZ. To analyze the fate of replication forks (Fig. 1A, right), DNA was isolated from wild-type and hpr1Δ cells grown in glucose- or galactose-containing medium, linearized with PmlI, and subjected to 2D gel electrophoresis. As can be seen in Fig. 1B, replication fork progression was significantly affected in hpr1Δ cells upon activation of lacZ transcription. Comparing replication intermediate from these cells to replication intermediates from wild-type cells grown in galactose or from either wild-type or hpr1Δ cells grown in glucose, we observed a strong decline of the bubble arc signal towards a double-Y arc (Fig. 1B). In addition, the signals along the spike with double DNA content (2x) were shifted to the top. As depicted in Fig. 1C, uniform fork progressions in wild-type cells is consistent with the formation of large, bubble-shaped molecules as well as asymmetric X- and double-Y-shaped molecules. However, transcription in hpr1Δ cells appears to constrain either initiation of the rightward-moving replication fork or its progression along the 3′ end of lacZ. This would explain the presence of short, bubble-shaped molecules and an increased signal at the top of the 2x spike, reflecting an accumulation of symmetric, X-shaped termination intermediates, as shown in Fig. 1B.

FIG. 1.

Impaired replication fork progression in hpr1Δ mutants. (A) Scheme of the 6.26-kb pRWY005 yeast plasmid constructed for this study (left) and a 2D gel pattern of predictable replication intermediates upon plasmid linearization (right). Depicted are restriction sites, functional elements, and a 2D migration pattern of different forms of replication intermediates or uncut plasmid. nc, nicked circular; Dim., dimension. (B) 2D gel analysis of PmlI-digested plasmid DNA from wild-type (WT) and hpr1::KAN cells. Note that the gel slice used after the first dimension was mainly devoid of the 3-kb nonreplicating SmaI-SacI fragment. The transcriptional status of lacZ from cells grown either in galactose (ON) or in glucose (OFF) is indicated. The arrow points to a very faint signal corresponding to bubble-shaped molecules derived from hpr1Δ cells grown in galactose. Note that a weak signal intensity for the bubble arc was repeatedly obtained with PmlI-digested DNA. (C) Scheme of fork progression in galactose based on the replication intermediates shown in panel B. The switch from bubble- to double-Y-shaped molecules (arrow) and the region of replication termination (gray bar) are indicated. Representative gels of two independent experiments are shown.

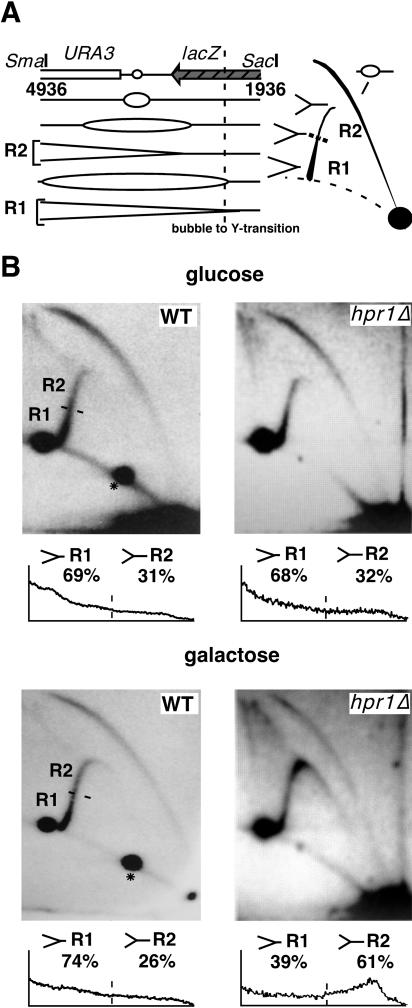

To establish that transcription affects replication fork progression at lacZ rather than initiation at ARS1, we analyzed replication intermediates in the 3-kb SacI/SmaI fragment harboring ARS1 and part of the lacZ gene (Fig. 2A). Provided that in pRWY005, bidirectional fork progression occurs at similar rates, transitions from bubble to simple-Y arcs should take place when about 90% of the fragment is replicated (Fig. 2A). Therefore, we expected to observe the majority of Y-shaped intermediates appearing along the descending simple-Y arc, in which the length of the newly replicated fragment exceeded the length of the nonreplicated one. As can be seen in Fig. 2B, replication intermediates isolated from wild-type and hpr1Δ cells grown in glucose were present mostly as bubble- and Y-shaped molecules. The accumulation of Y-shaped molecules toward the end of the descending simple-Y arc indicates similar rates of progression of replication forks in most cells. To estimate the distribution of molecules along the descending simple-Y arc, we quantified the signal intensity along the descending simple-Y arc. The profile and values of the descending simple-Y arc show that in the wild type, ∼69% (glucose) and ∼74% (galactose) of the replication intermediates were made up of nearly fully replicated simple-Y-shaped molecules, which were termed R1. Thus, transcription activation had no effect on the relative amounts of R1-type molecules in wild-type cells. A similar value, namely, ∼68%, of R1 molecules, was found in hpr1Δ cells grown in glucose. In contrast, upon transcription activation, Y-shaped replication intermediates obtained from hpr1Δ cells accumulated around the inflection point. These molecules, in which the newly replicated fragment equals the nonreplicated one in size, were named R2. An increase in R2-type molecules is consistent with a slowdown or pausing of the rightward-traveling replication fork along the 3′ end of lacZ. In addition, as expected for replication slowdown, in hpr1Δ cells the intensity and extent of the bubble arc decreased and a cone-shaped signal left of the simple-Y arc appeared. The cone-shaped signal extending from the inflection point to the 2x molecules most likely contains double-Y-shaped intermediates which represent leftward-moving forks approaching the rightward-moving forks paused at the 3′-end region of lacZ.

FIG. 2.

Slowdown of replication fork progression at the 3′ end of the transcribed lacZ gene. (A) 2D gel migration pattern of replication intermediates of the 3-kb SmaI-SacI fragment. Schemes of the expected replication intermediates (left) in which the predicted transition from bubble to simple-Y arc (dashed line) and the migration pattern after 2D gel electrophoresis (right) are indicated. Depicted are the locations of simple-Y-shaped replication intermediates corresponding to normally progressing (R1) or impaired (R2) replication forks. (B) 2D gel analysis of replication intermediates isolated from wild-type (WT) or hpr1::KAN cells grown in glucose (top) and galactose (bottom). The profile of replication intermediate distribution within the descending simple-Y arc is represented, and the quantification data of the regions corresponding to R1- or R2-type molecules are presented underneath the gels. Similar numbers were obtained from analysis of replication intermediates derived from two independent experiments. Note that the intense spot signal along the arc of linear molecules at the left end of the Y arc may represent unspecific hybridization or single-cut, linearized plasmid, while the spot signal to the right of the left end of the Y arc results from unspecific hybridization (asterisk).

Although it is conceivable that replication fork pausing occurs at URA3 sequences, we exclude this possibility for several reasons: expression levels of the URA3 gene are similar in glucose- and galactose-containing medium, and the effect that we observed is unique to galactose. In addition, transcription of the URA3 gene is codirectional with replication, and we were not able to detect pausing or slowdown of replication in a plasmid construct containing lacZ placed codirectionally with replication (data not shown).

Aberrant processing of the nascent mRNA contributes to constrained replication.

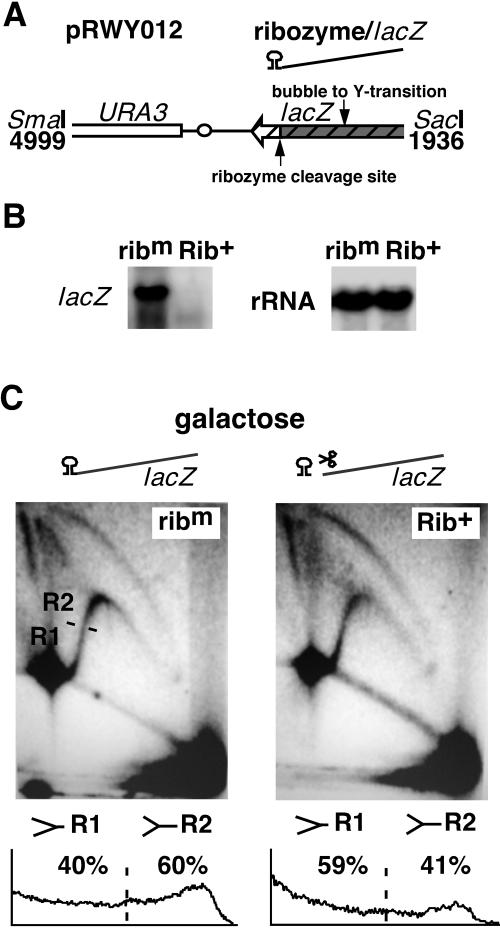

Our results suggest that replication impairment occurs along the actively transcribed lacZ gene in hpr1Δ cells (Fig. 2B). This finding is in accordance with previous studies showing that transcription impairment was predominantly detected towards the 3′ end of the transcription unit (15) and that the relative levels of Hpr1 with respect to RNAPII increase towards the 3′ end of a transcribed gene (31). To assay whether replication slowdown was mediated by nascent mRNA, we took advantage of a self-cleaving hammerhead ribozyme sequence (38). A 346-bp sequence coding for the ribozyme and U3 snRNA was inserted between the 3′ end of the lacZ ORF and the CYC1 transcriptional-termination sequence (Fig. 3A). For a negative control, we made a second construct (ribm), in which ribozyme self-cleavage is inactive, by mutating a single base pair (G to C) in the hammerhead sequence. Efficient RNA self-cleavage was determined by Northern blot analysis (Fig. 3B). Transcription of lacZ from the ribm construct produced a full-length, 3.35-kb mRNA. When the active hammerhead ribozyme (Rib+) is transcribed, the nascent transcript is self-cleaved, leading to two different mRNAs from the same transcriptional unit, a downstream mRNA containing the ribozyme and U3 snRNA sequence (0.35 kb, comigrating with the endogenous U3 snRNA) and an upstream mRNA containing the lacZ ORF (3 kb). Neither the full-length nor a 3-kb mRNA cleavage product was detected upon transcription of the Rib+ construct, consistent with a rapid degradation of the lacZ transcript upon ribozyme cleavage (15).

FIG. 3.

Ribozyme-mediated self-cleavage of nascent mRNA results in a partial suppression of replication slowdown. (A) Scheme of the region containing the ribozyme sequence. The 346-bp ribozyme is depicted in the form of a secondary-structure RNA sequence placed at the 3′ end of the lacZ transcript. (B) Northern blot analysis of full-length lacZ mRNA transcripts. (C) 2D gel analysis of replication intermediates of pRWY012 constructs isolated from hpr1Δ cells. Hybridization against a 3.2-kb SmaI-SacI fragment is shown. Schemes of the construct containing the inactive (ribm) or active (Rib+) ribozyme sequence are indicated on the top. Distribution and quantification of replication intermediates within the descending simple-Y arc are presented at the bottom. For other details, see the legend to Fig. 2.

2D gel analysis revealed that transcription impeded replication fork progression through lacZ in the ribm construct (representative experiments are shown in Fig. 3C), in which R2 intermediates accumulated in ∼62.3% (±2.1%) of simple-Y-shaped molecules. This observation complements the result obtained with pRWY005. Interestingly, ribozyme self-cleavage of the Rib+ mRNA reduced the amount of R2 molecules to ∼45% (±3.6%). This result indicates that the nascent mRNA plays a role in the pausing or slowdown of replication fork progressions in hpr1Δ cells and that this effect is evident towards the 3′ end of lacZ.

lacZ sequence-specific features are required to perturb replication.

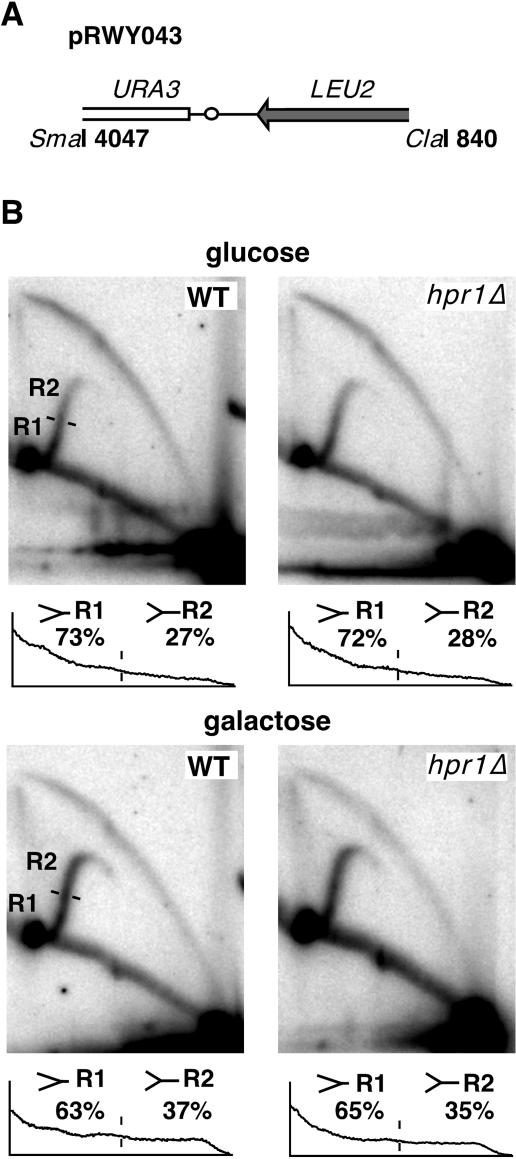

Since Hpr1 is preferentially required for transcription of long and GC-rich DNA sequences, like lacZ (6), replication processivity might be adversely affected in response to mRNA sequences, which are difficult to transcribe. To test this possibility, we replaced lacZ sequences by leu2 sequences (Fig. 4A; Materials and Methods) and analyzed replication by 2D gel electrophoresis (Fig. 4B). In wild-type cells, transcription barely affected fork progression since we obtained similar numbers of R1-type, simple-Y-shaped intermediates in glucose (∼73%) and galactose (∼63%). This finding is in accordance with data obtained with the lacZ-containing plasmid. Interestingly, in hpr1Δ cells, the numbers for R1-type intermediates in glucose (∼72%) and galactose (∼65%) resembled those found in wild-type cells. In hpr1Δ cells, transcription of leu2 therefore appears to barely exhibit an effect on replication fork progression. Taken together, these results suggest that specific features of the lacZ sequence consolidate replication impairment in hpr1Δ cells.

FIG. 4.

leu2 sequences are not sufficient to induce hpr1Δ-dependent replication constraints. (A) Scheme of a 3-kb fragment containing the leu2 sequence. (B) 2D gel analysis of replication intermediates. Distribution and quantification of replication intermediates within the descending simple-Y arc are presented at the bottom. For other details, see the legend to Fig. 2.

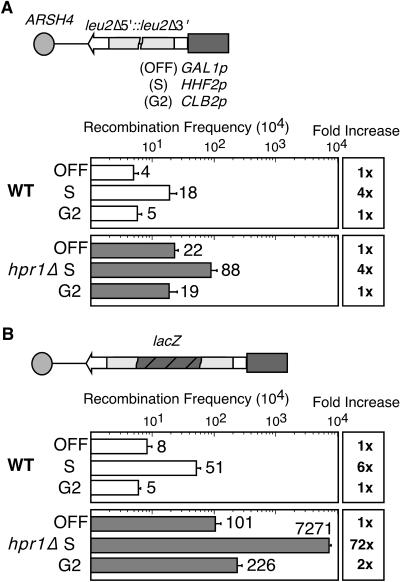

Transcription-dependent hyperrecombination in hpr1Δ cells occurs in DNA sequences transcribed in S phase but not in G2.

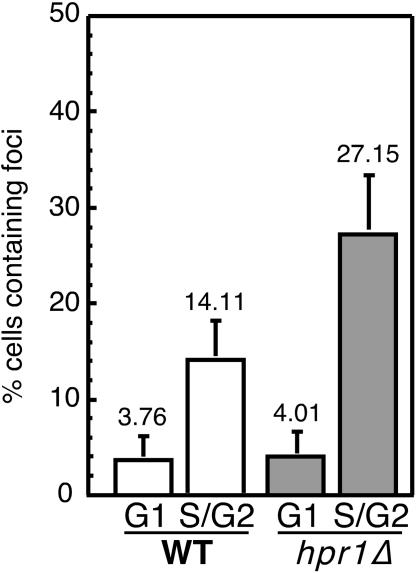

We noted that hpr1Δ cells grown in galactose contained less plasmid DNA than cells grown in glucose (data not shown). This result is consistent with previous observations (4, 33) linking aberrant transcription to reduced plasmid stability. Since tho-mediated defects in mRNP biogenesis have been related to genetic instability, we were interested to see whether recombinational repair has been activated in hpr1Δ cells. Rad52 is a key protein in the repair of pathogenic DNA structures via homologous recombination. Rad52-YFP foci appear both spontaneously and in response to double-strand breaks during S and G2 phases, indicating the importance of recombinational repair during DNA replication (27). We also wondered whether hpr1Δ increased the number of cells containing Rad52 repair centers. As can be seen in Fig. 5, in the unbudded G1 phase, approximately 4% of wild-type and hpr1Δ cells contained Rad52-YFP foci. However, the number of budded S/G2 cells containing Rad52-YFP foci increased from 14% in the wild type to 27% in hpr1Δ cells.

FIG. 5.

hpr1::KAN leads to an accumulation of Rad52 foci during replication. Percentages of cells containing Rad52-YFP foci are shown. The average number of foci, as determined in exponentially growing cell cultures obtained from three independent transformants, is shown. Unbudded (G1) and budded (S/G2) cells were counted separately. WT, wild type.

One possible explanation for this observation is that replication-dependent pathogenic structures are formed at high levels in hpr1Δ cells. If this was the case, we reasoned that TAR should be linked to transcription during S phase. To test this hypothesis, we used DNA repeat recombination constructs (35) (Fig. 6) in which transcription along the two leu2 repeats was under the control of the glucose-repressible GAL1 promoter (low or no transcription in glucose) and the cell cycle-specific HHF2 or CLB2 promoter, which activates transcription at either the S (14) or the G2 (30) phase, respectively. Based on the observation that replication was specifically affected by lacZ transcription, we designed two sets of constructs, one without intervening sequences and one containing lacZ between the leu2 repeats. In wild-type cells, HHF2-promoted, S-phase transcription caused an approximately fourfold increase in recombination between the leu2 repeats versus the levels under low transcription, whereas CLB2-promoted, G2-phase transcription led to the same recombination levels as with low transcription (Fig. 6A). In hpr1Δ cells, the basal level of recombination between the leu2 repeats was elevated approximately four- to fivefold. However, as in wild-type cells, a further approximately fourfold stimulation of recombination was obtained upon S-phase transcription and there was no effect upon G2 transcription, in which recombination was the same as under low transcription (Fig. 6A). This finding indicates that transcription along the leu2 repeats does not stimulate recombination in hpr1Δ cells, consistent with the lack of effect of hpr1Δ on LEU2 transcription (36).

FIG. 6.

hpr1Δ-dependent hyperrecombination requires transcription during S phase. Recombination frequencies of leu2 repeat constructs in which transcription of the GAL1 promoter is repressed in 2% glucose (OFF), driven by the S-phase-specific HHF2 (S) or G2-phase-specific CLB2 (G2) promoters in wild-type (WT) and hpr1::KAN cells. (A) Recombination in the leu2Δ5′::leu2Δ5′ repeat construct without an intervening DNA sequence. (B) Recombination in the leu2Δ5′::lacZ::leu2Δ5′ repeat construct containing lacZ between the leu2 repeats. A scheme of each construct is shown on top of each panel. The average and standard deviation of four median frequencies, each obtained from six independent cultures, are indicated for each genotype.

In the recombination constructs containing lacZ between the leu2 repeats, transcription during S phase increased recombination approximately sixfold above the levels under low transcription in wild-type cells, whereas no effect was observed for transcription during G2 (Fig. 6B). Introduction of the lacZ sequence between the leu2 repeats caused a weak increase (∼12-fold) of recombination in hpr1Δ cells under low transcription, consistent with previous results (4, 5). Importantly, the lacZ sequence boosted S-phase-transcription-dependent recombination levels from ∼6-fold in wild-type cells to ∼72-fold in hpr1Δ cells compared with their respective basal levels (Fig. 6B). Transcription during G2 increased recombination only twofold, indicating that transcription along the lacZ sequence by itself is not sufficient to induce recombination in hpr1Δ mutants. Rather, recombination requires transcription during S phase, suggesting that increased TAR in hpr1Δ cells is the consequence of pathogenic structures formed during replication fork progression.

DISCUSSION

A hallmark phenotype of THO/TREX mutants affected in mRNP biogenesis is their strong transcription-dependent hyperrecombination, suggesting a relevant role for the complex in the maintenance of the genetic stability of transcribed DNA sequences (1). Here, we show that the genetic instability of hpr1Δ mutants may be linked to a slowdown or pausing of replication under conditions of active transcription. Replication impairment was dependent on long, nascent mRNA molecules, as deduced from the fact that ribozyme-mediated cleavage of the nascent mRNA partially suppressed the replication defect. Besides, recombination in hpr1Δ cells is induced by transcription during S phase but not during G2. Consistently, hpr1Δ increased the number of budded cells containing Rad52 foci.

RNAPII- and RNAPIII-driven transcription have been shown to affect replication fork progression, leading to distinct RFPs (9, 35). In the rDNA locus, collision between replication and RNAPI transcription is avoided by a specific replication-termination site at the 3′ end of the rDNA transcription unit (3). However, removal of the RFB and consequent collision between RNAPI and replication has been reported to result in a replication slowdown region along the transcribed 35S rDNA gene (41). Importantly, we observe a similar replication slowdown along the RNAPII-transcribed lacZ gene that is not caused by transcription alone but in combination with deficient mRNP biogenesis (Fig. 2). In the case of tRNA and rRNA gene transcription, a high transcription rate and a high density of RNA polymerases might be sufficient to halt replication. In contrast, the mRNA transcription levels and RNAPII density might not be enough to affect fork progression. An increased density of RNAPIIs in an hpr1Δ mutant background can be excluded from consideration as being responsible for a slowdown or pausing of replication because it has been shown that the RNAPII density is lowered towards the 3′ end of a transcribed gene (31). This result is consistent with the observation that disruption of the THO complex results in decreased abundance of RNA corresponding to the 3′ ends of long genes, with little or no effect on 5′ RNA levels (4, 15). Under natural, wild-type conditions, the mRNP particle itself appears to be incapable of acting as a hindrance to fork progression. In hpr1Δ cells, the mRNP particle might be altered at the levels of RNAPII complex composition, modifications of single RNAPII components, and/or undesirable DNA-RNA-protein interactions.

In metazoan cells, transcription-associated genomic instability is prevented by ASF/SF2, a pre-mRNA-processing factor coupled to mRNA transcription by the C-terminal domain of the largest subunit of RNAPII (25). ASF/SF2 is cotranscriptionally loaded onto the nascent pre-RNA, not only to promote splicing, but also to prevent R-loop formation. In ASF/SF2-depleted cells as well as in hpr1Δ mutants, such transcription-associated R loops appear to mediate TAR (15, 25). Interestingly, effective replication fork progression in hpr1Δ cells can be partially restored by ribozyme-mediated mRNA cleavage. This result implies that mRNA self-cleavage diminished the tendency of aberrant mRNP particles to interfere with replication.

Impaired replication might trigger mitotic recombination and explain the correlation between a distinct, naturally occurring fork-pausing site in leu2 sequences and TAR in wild-type cells (35). Despite the known differences between transcription-dependent hyperrecombination in hpr1 cells and TAR in wild-type cells, in this study we consider the possibility that mitotic recombination can be stimulated by transcription because impaired mRNP biogenesis compromises replication. Thus, we show that transcription by itself is not sufficient to induce recombination in hpr1Δ cells. It is necessary that transcription occurs specifically during the S phase. When transcription is specifically promoted at G2, hyperrecombination is not evident, in agreement with previous observations indicating that TAR in wild-type cells was S phase dependent (35). This, together with the observation that both replication fork impairment and hyperrecombination are particularly associated with transcription along specific DNA sequences, such as lacZ, suggests that replication impairment and hyperrecombination in hpr1Δ cells are linked. Therefore, these results offer a first clue to understand transcription-dependent hyperrecombination in mRNP assembly-defective mutants. Consistent with the idea that mitotic recombination is a major DNA repair pathway aimed at correcting replication failures (8, 37), chromosome and plasmid loss in hpr1Δ mutants (4, 32, 39) may partially result from miscarried replication. In THO complex mutants, actively transcribed long DNA sequences of high GC content, like lacZ, might form structures of an unknown nature, whether or not they involve the nascent mRNA or the RNAPII, capable of impairing fork processivity. Whether this model can be extended to TAR in wild-type cells needs further investigation.

The increase in Rad52-YFP foci in budded hpr1Δ cells suggests that high levels of recombination induced by THO mutants occur in S/G2. This is consistent with the observation that hpr1Δ hyperrecombination is primarily coupled to S-phase-specific transcription. Further analysis would be required to know whether replication fork progression could be sensitive to the presence of export-incompetent mRNPs at the transcription site, to formation of obstructive mRNA-RNAPII-DNA ternary complexes, or to aberrant DNA/RNA structures produced as a consequence of defective mRNP biogenesis.

In response to DNA damage and replication pausing, eukaryotes activate checkpoint pathways that prevent genetic instability by coordinating cell cycle progression with DNA repair (22). In checkpoint-deficient mutants, dissociation of replication proteins might be associated with the formation of long stretches of single-stranded DNA (ssDNA), as has been shown in response to hydroxyurea treatment where ∼300 bp of ssDNA accumulates at the replication fork (28). The formation of ssDNA-replication protein A complexes has been proposed to be a trigger for checkpoint activation (47). Fob1-dependent replication stalling at the budding yeast RFB results in only a few bp of ssDNA (12), suggesting that the lack of ssDNA would preclude checkpoint activation. So far, we have not been able to address whether ssDNA accumulates at the replication fork in hpr1Δ cells. It would be interesting to address to what extent S-phase-specific checkpoints are activated in hpr1Δ cells.

It is conceivable that replication failures are also responsible for other types of TAR, whether occurring accidentally or as developmentally regulated processes, such as class switching of the immunoglobulin genes. Proper mRNP biogenesis mediated by the THO/TREX complex also appears to be important for cell proliferation. It is worth mentioning that, in a recent study, high expression of the human homologue of Hpr1 (human TREX84) has been linked to metastatic breast cancer (13). In higher eukaryotes, impaired function of proteins homologous to the yeast THO complex (26) might lead to severe defects in mitotic cells during all stages of development. Thus, our work establishes a novel connection between mRNP biogenesis and replication fork progression and may open new perspectives for understanding the connections between genomic instability and cancer.

Acknowledgments

We thank H. Gaillard and D. Fitzgerald for critical reading of the manuscript and D. Haun for style supervision.

Research was funded by grants from the Spanish Ministry of Science and Education (SAF2003-00204) and the M. Curie Host Development Program (HPMD-CT 2000-0003).

REFERENCES

- 1.Aguilera, A. 2002. The connection between transcription and genomic instability. EMBO J. 21:195-201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aguilera, A., and H. L. Klein. 1988. Genetic control of intrachromosomal recombination in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. I. Isolation and genetic characterization of hyper-recombination mutations. Genetics 119:779-790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brewer, B. J., and W. L. Fangman. 1988. A replication fork barrier at the 3′ end of yeast ribosomal RNA genes. Cell 55:637-643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chavez, S., and A. Aguilera. 1997. The yeast HPR1 gene has a functional role in transcriptional elongation that uncovers a novel source of genome instability. Genes Dev. 11:3459-3470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chavez, S., T. Beilharz, A. G. Rondon, H. Erdjument-Bromage, P. Tempst, J. Q. Svejstrup, T. Lithgow, and A. Aguilera. 2000. A protein complex containing Tho2, Hpr1, Mft1 and a novel protein, Thp2, connects transcription elongation with mitotic recombination in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. EMBO J. 19:5824-5834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chávez, S., M. García-Rubio, F. Prado, and A. Aguilera. 2001. Hpr1 is preferentially required for transcription of either long or G+C-rich DNA sequences in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21:7054-7064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Courcelle, J., and P. C. Hanawalt. 2003. RecA-dependent recovery of arrested DNA replication forks. Annu. Rev. Genet. 37:611-646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cox, M. M. 2001. Recombinational DNA repair of damaged replication forks in Escherichia coli: questions. Annu. Rev. Genet. 35:53-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deshpande, A. M., and C. S. Newlon. 1996. DNA replication fork pause sites dependent on transcription. Science 272:1030-1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gallardo, M., and A. Aguilera. 2001. A new hyperrecombination mutation identifies a novel yeast gene, THP1, connecting transcription elongation with mitotic recombination. Genetics 157:79-89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Greenfeder, S. A., and C. S. Newlon. 1992. Replication forks pause at yeast centromeres. Mol. Cell. Biol. 12:4056-4066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gruber, M., R. E. Wellinger, and J. M. Sogo. 2000. Architecture of the replication fork stalled at the 3′ end of yeast ribosomal genes. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:5777-5787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guo, S., M. A. Hakimi, D. Baillat, X. Chen, M. J. Farber, A. J. Klein-Szanto, N. S. Cooch, A. K. Godwin, and R. Shiekhattar. 2005. Linking transcriptional elongation and messenger RNA export to metastatic breast cancers. Cancer Res. 65:3011-3016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hereford, L. M., M. A. Osley, T. R. Ludwig II, and C. S. McLaughlin. 1981. Cell-cycle regulation of yeast histone mRNA. Cell 24:367-375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huertas, P., and A. Aguilera. 2003. Cotranscriptionally formed DNA:RNA hybrids mediate transcription elongation impairment and transcription-associated recombination. Mol. Cell 12:711-721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hyrien, O. 2000. Mechanisms and consequences of replication fork arrest. Biochimie 82:5-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ivessa, A. S., B. A. Lenzmeier, J. B. Bessler, L. K. Goudsouzian, S. L. Schnakenberg, and V. A. Zakian. 2003. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae helicase Rrm3p facilitates replication past nonhistone protein-DNA complexes. Mol. Cell 12:1525-1536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ivessa, A. S., J. Q. Zhou, V. P. Schulz, E. K. Monson, and V. A. Zakian. 2002. Saccharomyces Rrm3p, a 5′ to 3′ DNA helicase that promotes replication fork progression through telomeric and subtelomeric DNA. Genes Dev. 16:1383-1396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jimeno, S., A. G. Rondon, R. Luna, and A. Aguilera. 2002. The yeast THO complex and mRNA export factors link RNA metabolism with transcription and genome instability. EMBO J. 21:3526-3535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kelly, T. J., and G. W. Brown. 2000. Regulation of chromosome replication. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 69:829-880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kobayashi, T., and T. Horiuchi. 1996. A yeast gene product, Fob1 protein, required for both replication fork blocking and recombinational hotspot activities. Genes Cells 1:465-474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lambert, S., and A. M. Carr. 2005. Checkpoint responses to replication fork barriers. Biochimie 87:591-602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lambert, S., A. Watson, D. M. Sheedy, B. Martin, and A. M. Carr. 2005. Gross chromosomal rearrangements and elevated recombination at an inducible site-specific replication fork barrier. Cell 121:689-702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lea, D. E., and C. A. Coulson. 1949. The distribution of the numbers of mutants in bacterial populations. J. Genet. 49:264-285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li, X., and J. L. Manley. 2005. Inactivation of the SR protein splicing factor ASF/SF2 results in genomic instability. Cell 122:365-378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li, Y., X. Wang, X. Zhang, and D. W. Goodrich. 2005. Human hHpr1/p84/Thoc1 regulates transcriptional elongation and physically links RNA polymerase II and RNA processing factors. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25:4023-4033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lisby, M., R. Rothstein, and U. H. Mortensen. 2001. Rad52 forms DNA repair and recombination centers during S phase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:8276-8282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lopes, M., C. Cotta-Ramusino, A. Pellicioli, G. Liberi, P. Plevani, M. Muzi-Falconi, C. S. Newlon, and M. Foiani. 2001. The DNA replication checkpoint response stabilizes stalled replication forks. Nature 412:557-561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Luna, R., S. Jimeno, M. Marin, P. Huertas, M. Garcia-Rubio, and A. Aguilera. 2005. Interdependence between transcription and mRNP processing and export, and its impact on genetic stability. Mol. Cell 18:711-722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maher, M., F. Cong, D. Kindelberger, K. Nasmyth, and S. Dalton. 1995. Cell cycle-regulated transcription of the CLB2 gene is dependent on Mcm1 and a ternary complex factor. Mol. Cell. Biol. 15:3129-3137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mason, P. B., and K. Struhl. 2003. The FACT complex travels with elongating RNA polymerase II and is important for the fidelity of transcriptional initiation in vivo. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23:8323-8333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McGlynn, P., and R. G. Lloyd. 2002. Recombinational repair and restart of damaged replication forks. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 3:859-870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Merker, R. J., and H. L. Klein. 2002. Role of transcription in plasmid maintenance in the hpr1Δ mutant of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22:8763-8773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Michel, B., G. Grompone, M. J. Flores, and V. Bidnenko. 2004. Multiple pathways process stalled replication forks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101:12783-12788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Prado, F., and A. Aguilera. 2005. Impairment of replication fork progression mediates RNA polII transcription-associated recombination. EMBO J. 24:1267-1276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Prado, F., J. I. Piruat, and A. Aguilera. 1997. Recombination between DNA repeats in yeast hpr1delta cells is linked to transcription elongation. EMBO J. 16:2826-2835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rothstein, R., B. Michel, and S. Gangloff. 2000. Replication fork pausing and recombination or “gimme a break.” Genes Dev. 14:1-10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Samarsky, D. A., G. Ferbeyre, E. Bertrand, R. H. Singer, R. Cedergren, and M. J. Fournier. 1999. A small nucleolar RNA:ribozyme hybrid cleaves a nucleolar RNA target in vivo with near-perfect efficiency. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:6609-6614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Santos-Rosa, H., and A. Aguilera. 1994. Increase in incidence of chromosome instability and non-conservative recombination between repeats in Saccharomyces cerevisiae hpr1 delta strains. Mol. Gen. Genet. 245:224-236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Strasser, K., S. Masuda, P. Mason, J. Pfannstiel, M. Oppizzi, S. Rodriguez-Navarro, A. G. Rondon, A. Aguilera, K. Struhl, R. Reed, and E. Hurt. 2002. TREX is a conserved complex coupling transcription with messenger RNA export. Nature 417:304-308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Takeuchi, Y., T. Horiuchi, and T. Kobayashi. 2003. Transcription-dependent recombination and the role of fork collision in yeast rDNA. Genes Dev. 17:1497-1506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Thoma, F., L. W. Bergman, and R. T. Simpson. 1984. Nuclease digestion of circular TRP1ARS1 chromatin reveals positioned nucleosomes separated by nuclease-sensitive regions. J. Mol. Biol. 177:715-733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thomas, B. J., and R. Rothstein. 1989. Elevated recombination rates in transcriptionally active DNA. Cell 56:619-630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang, Y., M. Vujcic, and D. Kowalski. 2001. DNA replication forks pause at silent origins near the HML locus in budding yeast. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21:4938-4948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wellinger, R. E., P. Schär, and J. M. Sogo. 2003. Rad52-independent accumulation of joint circular minichromosomes during S phase in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23:6363-6372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zenklusen, D., P. Vinciguerra, J.-C. Wyss, and F. Stutz. 2002. Stable mRNP formation and export require cotranscriptional recruitment of the mRNA export factors Yra1p and Sub2p by Hpr1p. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22:8241-8253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zou, L., and S. J. Elledge. 2003. Sensing DNA damage through ATRIP recognition of RPA-ssDNA complexes. Science 300:1542-1548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]