Abstract

Objectives. This study examined whether marital status is associated with suicide rates among various age, sex, and racial groups, in particular with widowhood among young adults of both sexes.

Methods. US national suicide mortality data were compiled for the years 1991–1996, and suicide rates were broken down by race, 5-year age groups, sex, and marital status.

Results. Data on suicide rates indicated an approximately 17-fold increase among young widowed White men (aged 20–34 years), a 9-fold increase among young widowed African American men, and lesser increases among young widowed White women compared with their married counterparts.

Conclusions. National data suggest that as many as 1 in 400 White and African American widowed men aged 20–35 years will die by suicide in any given year (compared with 1 in 9000 married men in the general population).

Suicide is a serious public health problem and was among the top 10 causes of death in industrialized countries in 1990.1 In 2000, approximately 28 000 people died by suicide in the United States, making it the eleventh leading cause of death nationwide.2 Recently, the surgeon general released the National Strategy for Suicide Prevention: Goals and Objectives for Action, which calls for both general and targeted efforts to prevent suicide in the United States.3 Broad-based studies of suicide risk factors have had difficulty determining what risk factors could easily identify people at risk with enough specificity and sensitivity to make prevention programs more focused and effective.4 In this study we examined suicide rates in various groups by marital status, age, sex, and race to see if any of those groups have a base rate of suicide that would allow targeted interventions to be used. We focused largely on those recently widowed.

Since the time of Emile Durkheim (1858–1917),5 researchers have attempted to examine the association between marital status and suicide. In the ensuing one hundred years, research findings have supported the hypothesis that marriage is protective against suicide.6–9 These findings have been especially consistent for men, although this may largely be a result of the smaller number of suicides in women and resultant lack of statistical power to detect effects of marital status among women. Whereas divorce has been consistently associated with a higher risk of suicide,10 single or widowed status has been less consistently associated with an increased risk of suicide.7,8,11,12

Kreitman6 noted that widows and widowers in the first half of life appear to be at high risk for suicide. He called for “continuing attention [to the importance of widowhood] in suicide research, especially in the first half of life.”6 Other researchers have also identified an elevated rate of suicide in widows and widowers in the first half of life,13 as well as overall increased mortality among young widows and widowers compared with the general population.14 Even though rates of suicide as high as 113 per 100 000,6 185 per 100 000,9 and 660 per 100 00013 have been reported among young widows and widowers—from 8 to 50 times higher than the suicide rate for the general population—little attention has been paid to this high-risk group.

One reason for the lack of consistent findings of an increased risk for suicide among the widowed may be that researchers have generally assumed that increased risk of suicide in such individuals is consistent across the age span. Although this assumption may be necessary for many studies to have sufficient statistical power to detect a lowbase-rate event such as suicide, it may obscure important differences in risk across the life span that could have important prevention implications. For example, if being a young widow or widower is indeed associated with a particularly high risk of suicide, this group might be a good target for intervention. In addition to being at a high risk for suicide, the young widowed would be an easily identified group that present themselves in contexts (e.g., funeral homes, coroners’ offices) in which interventions could be developed and applied.

Although several studies have shown that people who are widowed in the first half of life appear to have a greatly increased risk of death by suicide,6,9,13 no studies have examined whether this finding holds across subpopulations such as different races or sexes. For example, widowhood may have a very different association with the suicide rates of African American men than with the rates of their White counterparts. We therefore examined suicide rates for various marital status categories among age, sex, and racial groups using US National Mortality data for the years 1991–1996 and calculated rates separately for men and women, African Americans and Whites, and 5-year age groups for persons aged 20 years and older.

METHODS

Data Sources

Suicide mortality data by marital status were compiled from the National Center for Health Statistics Multiple-Cause-of-Death Files for the years 1991–1996.15–20 Mortality data from death certificates is generally of high quality.21 Population estimates for each year were obtained from the US Census Bureau.

Calculation of Rates

Suicide rates in each group were calculated using a 6-year “running” average. Rates were calculated for groups broken down by race (African American vs White), 5-year age groups, sex, and marital status and for each group by dividing the total number of suicides occurring across the 6 years in our study by the total population summed across those years. For a few groups, census population estimates were not available for every year. In cases of missing census estimates, missing-year population data were estimated by averaging across the remaining years’ data. To control for inaccurate rate estimates due to chance variation, rates were calculated only for those groups in which at least 20 suicides occurred during the 6 years of the study.

Due to generally low numbers of suicides among African American women and the consequent unreliability of rate estimates, this group was excluded from this study. For example, among widowed decedents aged 20–24 years across the 6 years, there were 51 White men, 22 African American men, 10 White women, and 1 African American woman.

RESULTS

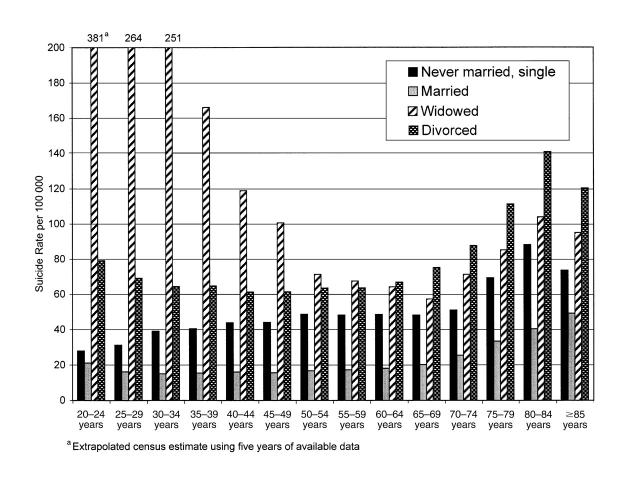

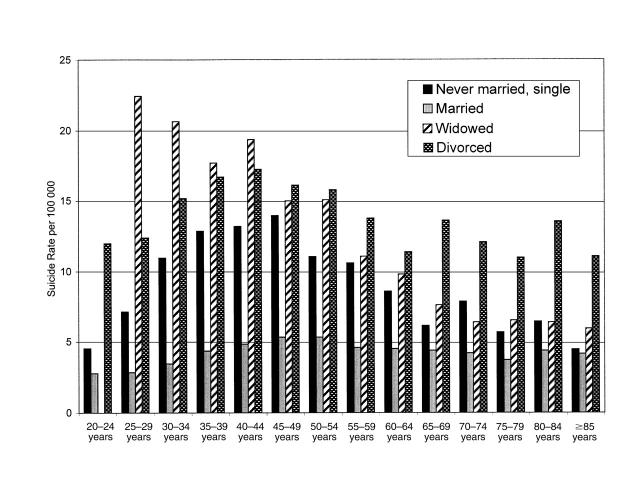

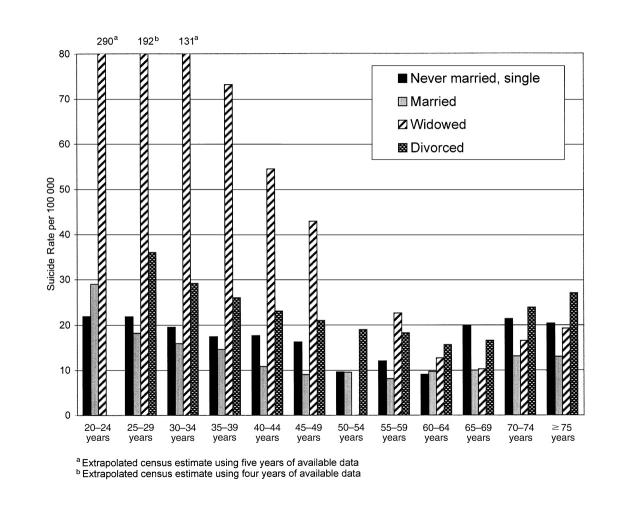

Results for White men, White women, and African American men are summarized in Figures 1–3 ▶ ▶ ▶, respectively. The pattern of risk varied with age. Our findings (based on a more recent cohort) replicate the results of Smith et al.,9 Kreitman,6 and Buda and Tsuang,13 which showed that the suicide rate is greatly elevated in young widows and widowers, specifically, in both White and African American young widowed men as compared with young White widowed women. The suicide rate is elevated for widowed men compared with men in other marital status groups for all ages under 50, but especially in the youngest age groups. It is important to note this pattern among young African American men, in that young widowers appear to be the only marital status group to have a substantial association with suicide rates.

FIGURE 1.

—Suicide rates for adult White males, by marital staus and age: United States, 1991–1996.

FIGURE 2.

—Suicide rates for adult White females, by marital staus and age: United States, 1991–1996.

FIGURE 3.

—Suicide rates for adult African American males, by marital staus and 5-year age: United States, 1991–1996.

At younger ages, being widowed, as compared with being divorced, appears to be associated with a higher risk of suicide. At older ages, however, this pattern reverses itself and divorce is associated with higher rates of suicide than is widowhood. The point at which the pattern reverses itself occurs much earlier among White women than it does among either African American or White men (i.e., between age 40 and 49 years for White women vs between age 55 and 65 years for African American and White men). Examination of Figures 1–3 ▶ ▶ ▶ also reveals that, across the life span, married people tend to have the lowest rates of suicide, with the possible exception of the youngest age groups.

DISCUSSION

Widowhood Across the Life Span

To our knowledge, this study included the largest sample to date in which suicide rates could be examined across different marital status groups. This large sample size also allowed us to be the first to report reliable rates of suicide among different marital status groups for African American vs White populations, and for both sexes. The most striking finding was the approximately 17-fold increase in the rate of suicide for the youngest widowed White men (aged 20–34 years) in comparison with their married counterparts. Young African American men showed similar patterns of risk (i.e., a 9-fold increase). These data demonstrate that the striking increase in suicide rates in young widowers is not just a White male phenomenon but also occurs among young African American men.

We propose one explanation why there is such a robust effect in this sample when past studies’ findings have been inconsistent in regard to the association between widowhood and suicide. A common limitation of past studies was the fact that they examined the relationship between widowhood and suicide, combining age groups across the life span and may have had low statistical power to detect this effect in younger age groups. Collapsing data across the life span might tend to obscure differences in suicide rates for widows and widowers vs other marital status groups because the largest number of suicides by the widowed are from the oldest age group, where widowhood is frequent. Since this is also the group in which widowhood appears to have the smallest association with suicide rates, combining large numbers of suicides by the older widowed with smaller numbers of suicides by the younger widowed (although with a very high rate of suicide) would tend to obscure the dramatic elevation in risk among younger widows and widowers.

The low rates of suicide among widowed women raises the question of why women, particularly African American women, appear to be “protected” from suicide in the context of widowhood. This issue has received some theoretical interest,22 but few empirical tests of this association exist. Beyond noting that women tend to use less lethal suicide methods,22 a fact that results in a greater attempt-to-completion ratio compared with men, a tremendous gap in our understanding of sex and racial differences remains. Learning more about possible sex and racial differences in bereavement processes may be one approach to closing this gap.23

There are several possible explanations for the dramatic changes in suicide risk in widowhood across the life span for men and to a lesser extent for women. A life course perspective posits that being widowed has very different meanings and effects at different points in the life course.24 When a younger person loses a spouse, it is considered an “off-time” event, and the personal adjustment following the loss is more difficult than for older age groups. Because the death of a spouse is less common during young adulthood, there may be little expectation of its occurrence, fewer models and preestablished patterns for grieving, and greater difficulty in accepting the death.25 In contrast, loss of a spouse may, for an older person, be expected and considered “on time,” resulting in a relatively easier adjustment.24

Research suggests that younger widows and widowers have higher levels of grief immediately following the loss than do older widows and widowers.26 This higher level of initial grief symptoms could help explain the higher rate of suicide in this group. Future research might also examine how the presence of children might affect the risk of suicide in young widows and widowers.

Unfortunately, surveillance data are not available with which to examine whether people suffering losses other than spousal bereavement might also be at increased risk of suicide. For example, many young people have partners who are not spouses. Loss of these partners may lead to similar patterns of risk. However, data are not available on this type of loss because surveillance only tracks marital status. In addition, our data do not address other sorts of risk factors that might contribute to the high suicide rate among young men. For example, substance abuse is second only to depression as a correlate of suicide in this age group, at least among White men.27 Further research would be useful to examine what other factors might play a role in the suicides of young, widowed men of various racial/ethnic groups.

Two other explanations for the observed effect are related to the possibility that high suicide rates in young widowers might be at least partially due to misclassification. One explanation is that young widowers may tend to be misclassified in the census data as single or married, thus resulting in excessively high rates of suicides in these ages (20–34).9 This explanation is not likely a full one, in that even if half of men were misclassified, a very improbable scenario, suicide rates would still be highly elevated in this group. Another, more likely explanation is that some suicides in the youngest age groups (20–34) might represent homicide–suicides, given that young married men commit a large proportion of homicide-suicides.28 Experts in the classification of death as suicide suggest that there is a lack of consensus as to how medical examiners or coroners tend to classify, on death certificates, the marital status of married male perpetrators of homicide–suicides. If the married perpetrators of homicide–suicides are often classified as “widowed,” this fact could account for some of the increased risk in the younger age groups.

Consultation with experts in this area (Eric Caine, MD, Julie Malphurs, PhD, oral communications, September 2000) suggested that married perpetrators of homicide–suicides are probably most often classified as married rather than widowed. Thus, it is not clear what proportion of suicides by the young widowed were part of homicide–suicides.

Limitations of Dataset

Several other points should be considered when interpreting the data presented in this study. First, data were not available concerning the length of time individuals had a particular marital status before death by suicide. However, several factors suggest that suicide may often occur shortly after the death of a spouse. For the young widowed, we can infer that they were mostly likely widowed within a few years of the suicide. In addition, some research has suggested that suicide is more likely to occur within the first 2 years following a loss than later,29 including suicides in later life.11 Mortality, in general, has also been shown to be higher in the months following bereavement.14,30

A second point to consider is that although very high rates of suicide occur among young widowed men, the absolute number of suicides in young widowed men is relatively small. There were about 90 suicides per year for White widowed men under the age of 40, and about 23 suicides per year for African American widowed men. This consideration is important to the allocation of limited prevention resources. While there may be extremely high rates of suicide in this younger age group (20–34 years), the absolute number of suicides in this age group is much smaller than in older widowers (e.g., about 1350 suicides per year among White men aged 65 and older).

Implications for Prevention

The extremely high risk of suicide in young widows and widowers has several implications for prevention. First, our data suggest that interventions aimed at decreasing extremely intense or prolonged forms of grief, particularly among young people, could be lifesaving. In addition, spousal bereavement in young men could be used as a marker to identify those at high risk for suicide. As proposed in Objective 7.5 of the National Strategy for Suicide Prevention,3 funeral directors, coroners, family, friends, and primary care physicians could be alerted to the risk of suicide in this population and intervene or refer to professionals to help prevent suicide.3 Our data suggest that as many as 1 in 400 White and African American widowers between the ages of 20 and 35 will complete a suicide in any given year (compared with 1 in 9000 married men in the general population).

We have no way to estimate how many young widowers attempt suicide, but the number is likely to be considerable. Conservatively estimating 3 attempts for every completion, at least 1 in 100 young widowers would be expected to attempt suicide in the years following spousal loss. The high risk for suicidal behavior in this easily identified group represents a unique opportunity for prevention. At the very least, further research should examine risk and protective factors pertaining to suicidal behavior among the recently widowed.

Peer Reviewed

Note. The views presented here are those of the authors, and do not necessarily represent those of the National Institute of Mental Health or the US Department of Health and Human Services.

Each author contributed to the planning, data analyses, and writing and editing of the article.

Footnotes

Human Participant Protection No protocol approval was needed for this study.

References

- 1.Murray CL, Lopez AD, eds. The global burden of disease. A comprehensive assessment of mortality and disability from diseases, injuries, and risk factors in 1990 and projected to 2020. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press; 1996.

- 2.Minino AM, Smith BL. Deaths: preliminary data for 2000. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2001;49(12):1–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Strategy for Suicide Prevention: Goals and Objectives for Action. Rockville, Md: US Dept of Health and Human Services; 2001.

- 4.Gunnell D, Frankel S: Prevention of suicide: aspirations and evidence. BMJ. 1994;308:1227–1233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Durkheim E. Suicide. New York, NY: Free Press; 1966.

- 6.Kreitman N. Suicide, age, and marital status. Psychol Med. 1988;18:121–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kposowa AJ. Marital status and suicide in the National Longitudinal Mortality Study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2000;54:254–261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Popoli G, Sobelman S, Kanarek: Suicide in the state of Maryland. Public Health Rep. 1989;104:298–301. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith JC, Mercy JA, Conn JM. Marital status and the risk of suicide. Am J Public Health. 1988;78:78–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stack S. Suicide: a 15-year review of the sociological literature. Part II: modernization and social integration perspectives. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2000:30:163–176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li G. The interaction effect of bereavement and sex on the risk of suicide in the elderly: an historical cohort study. Soc Sci Med. 1995;40:825–828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rico-Velaso J, Mynko L. Suicide and marital status: a changing relationship? Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1973;35:239–244. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Buda M, Tsuang MT. The epidemiology of suicide: implications for clinical practice. In: Blumenthal SI, Kupfer DJ, eds. Suicide Over the Life Cycle: Risk Factors, Assessments, and Treatments of Suicide Patients. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1990:17–38.

- 14.Stroebe MS, Stroebe W. The mortality of bereavement: a review. In: Stroebe MS, Stroebe W, Hansson RO, eds. Handbook of Bereavement: Theory, Research, and Intervention. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 1993:175–195.

- 15.National Center for Health Statistics. Multiple-Cause-of-Death File, 1991 [public use data on CD-ROM]. NCHS series 20, no. 9; 1997.

- 16.National Center for Health Statistics. Multiple Cause-of-Death File, 1992 [public use data on CD-ROM]. NCHS series 20, no. 10; 1997.

- 17.National Center for Health Statistics. Multiple Cause-of-Death File, 1993 [public use data on CD-ROM]. NCHS series 20, no. 11; 1997.

- 18.National Center for Health Statistics. Multiple Cause-of-Death File, 1994 [public use data on CD-ROM]. NCHS series 20, no. 13; 1999.

- 19.National Center for Health Statistics. Multiple Cause-of-Death File, 1995 [public use data on CD-ROM]. NCHS series 20, no. 16; 1999.

- 20.National Center for Health Statistics. Multiple Cause-of-Death File, 1996 [public use data on CD-ROM]. NCHS series 20, no. 17, 1999.

- 21.Poe GS, Powell-Griner E, McLaughlin JK, et al. Comparability of the death certificate and the 1986 National Mortality Followback Survey. Vital Health Stat 2. 1993; No. 118:1–53. [PubMed]

- 22.Canetto SS, Sakinofsky I. The gender paradox in suicide. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 1998;28:1–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bonanno A, Kaltman S: Toward an integrative perspective on bereavement. Psychol Bull. 1999;125:760–776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cohler BJ, Jenuwine MJ. Suicide, life course, and life story. Int Psychogeriatr. 1995;7:199–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Perkins HW. Familial bereavement and health in adult life course perspective. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1990;52:233–241. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sanders CM. Comparison of younger and older spouses in bereavement outcome. Omega. 1981;11:217–232. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Conwell Y, Brent D. Suicide and aging, I: patterns of psychiatric diagnosis. Int Psychogeriatr. 1995;7:149–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marzuk PM, Tardiff K, Hirsch CS. The epidemiology of murder-suicide. JAMA. 1992;23:3179–3183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bunch J. Recent bereavement in relation to suicide. J Psychosom Res. 1972;16:361–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kaprio J, Koskenvuo M, Rita H. Mortality after bereavement: a prospective study of 95,647 widowed persons. Am J Public Health. 1987;77:283–287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]