Abstract

As yeast cells enter meiosis, chromosomes move from a centromere-clustered (Rabl) to a telomere-clustered (bouquet) configuration and then to states of progressive homolog pairing where telomeres are more dispersed. It is uncertain at which stage of this process sequences commit to recombine with each other. Previous analyses using recombination between dispersed homologous sequences (ectopic recombination) support the view that, on average, homologs are aligned end to end by the time of commitment to recombination. We have undertaken further analyses incorporating new inserts, chromosome rearrangements, an alternate mode of recombination initiation, and mutants that disrupt nuclear structure or telomere metabolism. Our findings support previous conclusions and reveal that distance from the nearest telomere is an important parameter influencing recombination between dispersed sequences. In general, the farther dispersed sequences are from their nearest telomere, the less likely they are to engage in ectopic recombination. Neither the mode of initiating recombination nor the formation of the bouquet appears to affect this relationship. We suggest that aspects of telomere localization and behavior influence the organization and mobility of chromosomes along their entire length, during a critical period of meiosis I prophase that encompasses the homology search.

ALTHOUGH meiotic recombination is generally thought of as occurring between sequences at allelic positions on homologs, it can also occur between homologous sequences dispersed around the genome (Lichten et al. 1987; Kupiec and Petes 1988; Lichten and Haber 1989; Montgomery et al. 1991; Lim and Simmons 1994; Parket et al. 1995; Goldman and Lichten 1996; Robertson et al. 1997; Jinks-Virgin and Bailey 1998; Fischer et al. 2000). Such events, termed ectopic recombination, can result in chromosome nondisjunction at meiotic divisions and the formation of chromosome rearrangements that may lead to genetically unbalanced spores/gametes or contribute to speciation (Montgomery et al. 1991; Goldman and Lichten 1996; Jinks-Robertson et al. 1997; Virgin and Bailey 1998; Fischer et al. 2000). Eukaryotic organisms have evolved multiple strategies that prevent recombination between dispersed repeats. In a variety of organisms, repeated sequences are targets for silencing by chromatin and DNA modification. These and other mechanisms can have the effect of making such sequences unavailable for recombination (Kupiec and Petes 1988; Grewal and Klar 1997; Selker 1999; Ben-Aroya et al. 2004). The Spo11-catalyzed double-strand breaks (DSBs) that initiate meiotic recombination form primarily in open chromatin (Wu and Lichten 1994; Fan and Petes 1996). This tends to focus meiotic recombination into regions containing single-copy genes and away from repeated sequences (Civardi et al. 1994; Baudat and Nicolas 1997). Other work on the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae suggests that the process of progressive homolog colocalization and coalignment (hereafter referred to as homolog pairing) has the net effect of restricting ectopic recombination and favoring allelic recombination. Circumstances that either disrupt or delay normal homolog pairing relieve this restriction and increase the ability of dispersed homologous sequences to recombine (Goldman and Lichten 2000). Similar conclusions have been drawn in studies of Schizosaccharomyces pombe meiosis (Niwa et al. 2000).

An additional level of control over the ability of dispersed homologous sequences to recombine might be provided by the three-dimensional organization of chromosomes in the nucleus. It is becoming increasingly apparent that the spatial organization of chromosomes in the nucleus is often nonrandom. For some organisms there appears to be tight restriction of different chromosomes to different spatial domains, as well as tissue-specific or cell-cycle differences in the spatial relationship of different chromosomes (reviewed in Cremer and Cremer 2001; Parada and Misteli 2002). Localization of chromosome domains with respect to the nuclear periphery influences diverse functions such as transcription status and replication timing. For example, telomere localization at the nuclear envelope facilitates heterochromatin formation and transcriptional silencing in S. cerevisiae (Andrulis et al. 1998; Feuerbach et al. 2002). Attachment of telomeres to the nuclear envelope also plays important roles in the reorganization of chromosomes that occurs as cells prepare to enter meiosis. Cytological studies of many organisms, including budding yeast, have shown that chromosomes move from the classic Rabl orientation (with centromeres clustered and telomeres dispersed) in mitotic growth to a configuration termed the “bouquet” early in meiotic prophase I (reviewed in Scherthan 2001). During this reorganization, centromere clustering is lost, and all telomeres are located to a relatively small area of the nuclear periphery. In the bouquet, the main body of the chromosomes loops out into the inner space of the nucleus. Formation of the bouquet structure is dependent on the Ndj1 protein (also know as Tam1) in budding yeast, which localizes mainly to the telomeres (Chua and Roeder 1997; Conrad et al. 1997; Trelles-Sticken et al. 2000).

While cytogenetic studies have yielded most information on the layout of chromosomes in the nucleus, molecular and genetic analyses have also been informative. Dekker et al. (2002) used crosslinking and PCR analysis to determine the frequency at which different regions of budding yeast chromosome domains encounter each other in mitotic cells. Close proximity has also been assayed in recombination studies. These studies rely on the model that the likelihood of two sequences recombining with each other depends on the average amount of space separating them. For example, a Cre/lox recombination reporter system has been used to assay chromosome layout in mitotic yeast by measuring the likelihood of ectopic site-specific recombination events between dispersed lox sites (Burgess et al. 1999). High levels of interaction were found between sequences close to centromeres, consistent with cytological findings that yeast centromeres are clustered in a Rabl orientation (Jin et al. 1998). The same site-specific recombination assay has been used to examine meiotic chromosome pairing in wild-type and mutant strains of yeast (Peoples et al. 2002). Conclusions drawn from the Cre/lox assay fit well with cytological data, but also indicate that there is a level of cytologically detected chromosome juxtaposition that is not close enough for DNA interactions.

We previously examined the spatial relationship between meiotic chromosomes by measuring naturally occurring recombination between insert sequences dispersed around the genome. These studies used as a metric the efficiency of ectopic recombination, which relates the frequency of ectopic recombination between two loci to the frequency of allelic recombination at the same loci (Goldman and Lichten 1996, 2000). By comparing the efficiencies of ectopic recombination for different combinations of loci, we concluded that, on average, homologous chromosomes are in an end-to-end alignment when two sequences commit to recombine (Goldman and Lichten 1996). This was based largely on two observations. First, the efficiency of ectopic recombination between inserts on homologs is significantly greater than that between inserts on heterologous chromosomes. Second, for ectopic recombination between homologs, there is a negative correlation between efficiency and physical distance between insert loci. In addition, we found that the efficiency of ectopic recombination between inserts dispersed on heterologs is highest when both inserts are close to a telomere. We hypothesized that a separate compartment is created by the attachment of the telomeres to the nuclear periphery, restricting their movement and increasing the local concentration of subtelomere regions in the outer shell of the nucleus.

We have now tested this suggestion using additional insert loci, as well as reciprocal translocations that bring normally interstitial loci closer to a telomere. Consistent with previous observations, these new subtelomeric inserts recombine more efficiently with other inserts at naturally subtelomeric loci. Further experiments have been undertaken to better define the nature of the proposed compartmentalization of subtelomeric regions. Compartmentalization influences meiotic recombination along the entire length of chromosomes, whether initiated as normal by Spo11 or by an intein-encoded endonuclease, VMA1-derived endonuclease (VDE; Gimble and Thorner 1992). Our findings indicate that neither the timing of DSB formation nor the bouquet structure is likely to be responsible for creating the influence that chromosome ends have on the ectopic recombination. Alternative explanations are discussed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Wild-type strains containing arg4-nsp and arg4-bgl alleles located at all loci, apart from AAD3, PPX1, and YHL044W, are described in Wu and Lichten (1995) and Goldman and Lichten (1996). The arg4 alleles were inserted into AAD3, PPX1, and YHL044W, using modified versions of plasmids pMJ113 and pMJ115 (Wu and Lichten 1995), which contain inserts at the EcoRI site to target the insertion of arg4 alleles. Primers used to create the inserts following genomic PCR were GCCAACTACTGTGGTAATCACAAGCG and GGCGTTAGATCGATACTGAGAGC for AAD3; CCAGAAGCTTTGATAGAAAGCGCCGAGG and ATAGCTGCAGTGAACAACC for PPX1; and TGCGAAGGTGAGACAGTGATCC and CATCTCTGGATACTTATCCTCCC for YHL044W. In all new inserts the direction of transcription is toward the centromere.

A reciprocal translocation between HIS4 on chromosome III and PHO11 on chromosome I was created as described in Borde et al. (2000). Translocations were also created with breakpoints in HIS4 and PHO12 on chromosome VIII, GEA2 on chromosome V, and CHA1 on chromosome III. Insertion of the translocation-inducing cassettes (described in Borde et al. 2000) into new loci was achieved using genomic DNA sequence amplified by PCR using primers AAACGAGGGGCTTTACT and GTGTTCCGTAATAATCTTCCCAGCTGG for CHA1; CGGTTTGCTACTTTGCCATCCGG and CCGGGATCTCAGTGTTAGTGTCTTCG for GEA2; and CTTGGCGCAATATGGC and CAGCATCGTTGATGACG for PHO12. The arg4 heteroalleles were inserted into the translocation strains as described for wild-type strains (Wu and Lichten 1995; Goldman and Lichten 1996; and above).

The translocation construction technique results in strains being ade2. Due to concerns about the effects of varying the nutritional state of strains on meiotic recombination (Abdullah and Borts 2001), ADE2 was mated into the haploid translocation strains from otherwise isogenic SK1 strains to ensure that every diploid was homozygous for ADE2. The presence of the reciprocal translocation was confirmed by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis, using an initial switch time of 40 sec and a final switch time of 45 sec, an included angle of 120°, and a voltage gradient of 6 V/cm for 30 hr at 11°.

Haploids containing a ura3::arg4-VDE allele and expressing VDE are described in Neale et al. (2002). VDE-expressing strains with arg4-bgl inserts were created by standard genetic crosses. ndj1Δ strains were created by standard genetic crosses, mating haploids containing arg4 heteroalleles with previously created Δndj1 strains (Goldman and Lichten 2000).

The HDF1 ORF was deleted by integrating a PCR-generated KanMX cassette (Wach et al. 1994) flanked by 45 bases of 5′ and 3′ sequences flanking the HDF1 ORF. Primers used in amplification of the KanMX HDF1 deletion cassette (ATGATTTGTTAAGTGACTCTAAGCCTGATTTTAAAACGGGAATATTCGTACGCTGCAGGTCGA and AAATATTGTATGTAACGTTATAGATATGAAGGATTTCAATCGTCTATCGATGAATTGAGCTC) were kindly provided by E. J. Louis (University of Leicester). ndj1Δ hdf1Δ haploids containing arg4 inserts were constructed using standard genetic crosses.

Full details of all strain constructions are available on request. Diploids used to measure previously unpublished frequencies of Arg+ spores [f(Arg+)] are listed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Strains used in this study and not published elsewhere

| Locus with:

|

||

|---|---|---|

| Strain name | arg4-nsp | arg-bgl |

| Normala | ||

| MJL1905 | PPX1 | PHO12 |

| MJL1909 | PHO12 | PPX1 |

| MJL2107 | PPX1 | CHA1 |

| MJL2118 | CHA1 | PPX1 |

| MJL2120 | PPX1 | PHO11 |

| MJL2122 | PHO11 | PPX1 |

| MJL2126 | HIS4 | PPX1 |

| MJL2128 | PPX1 | HIS4 |

| MJL2130 | MAT | PPX1 |

| MJL2132 | PPX1 | MAT |

| MJL2134 | URA3 | PPX1 |

| MJL2136 | PPX1 | URA3 |

| MJL2156 | YHL044W | MAT |

| MJL2158 | MAT | YHL044W |

| MJL2160 | YHL044W | HIS4 |

| MJL2162 | HIS4 | YHL044W |

| MJL2164 | YHL044W | URA3 |

| MJL2166 | URA3 | YHL044W |

| MJL2168 | PPX1 | THR1 |

| MJL2170 | THR1 | PPX1 |

| MJL1937 | PPX1 | LEU2 |

| MJL1939 | LEU2 | PPX1 |

| MJL1903 | PPX1 | PUT2 |

| MJL1907 | PUT2 | PPX1 |

| MJL1901 | PPX1 | PPX1 |

| MJL1942 | YHL044W | PPX1 |

| MJL1945 | PPX1 | YHL044W |

| MJL1925 | YHL044W | PHO11 |

| MJL1927 | PHO11 | YHL044W |

| MJL1933 | YHL044W | CHA1 |

| MJL1936 | CHA1 | YHL044W |

| MJL1929 | YHL044W | PHO12 |

| MJL1931 | PHO12 | YHL044W |

| MJL1924 | YHL044W | YHL044W |

| MJL1947 | THR1 | YHL044W |

| MJL1949 | YHL044W | THR1 |

| dAG807 | AAD3 | LEU2 |

| dAG833 | LEU2 | AAD3 |

| dAG808 | AAD3 | PHO11 |

| dAG821 | PHO11 | AAD3 |

| dAG809 | AAD3 | PHO12 |

| dAG826 | PHO12 | AAD3 |

| dAG810 | AAD3 | URA3 |

| dAG815 | URA3 | AAD3 |

| dAG811 | AAD3 | THR1 |

| dAG817 | THR1 | AAD3 |

| dAG812 | AAD3 | PUT2 |

| dAG819 | PUT2 | AAD3 |

| dAG813 | AAD3 | HIS4 |

| dAG816 | HIS4 | AAD3 |

| dAG814 | MAT | AAD3 |

| dAG846 | AAD3 | MAT |

| dAG820 | AAD3 | AAD3 |

| dAG832 | YHL044W | AAD3 |

| dAG834 | AAD3 | YHL044W |

| dAG818 | PPX1 | AAD3 |

| dAG843 | AAD3 | PPX1 |

| dAG836 | AAD3 | CHA1 |

| dAG837 | CHA1 | AAD3 |

| Translocationsb | ||

| IIII and IIII | ||

| dAG238 | LEU2 | LEU2 |

| dAG241 | PHO12 | PHO12 |

| dAG244 | LEU2 | PHO12 |

| dAG247 | PHO12 | LEU2 |

| dAG1002 | PHO12 | URA3 |

| dAG1060 | URA3 | PHO12 |

| VIII and IIIV | ||

| dAG847 | PHO12 | PHO12 |

| dAG856 | URA3 | URA3 |

| dAG1132 | YHL044W | YHL044W |

| dAG853 | PHO12 | URA3 |

| dAG860 | URA3 | PHO12 |

| dAG1047 | PHO11 | PHO12 |

| dAG1058 | PHO12 | PHO11 |

| dAG1133 | YHL044W | URA3 |

| dAG1164 | URA3 | YHL044W |

| VIIIIII and IIIVIII | ||

| dAG748 | PHO11 | PHO11 |

| dAG785 | LEU2 | LEU2 |

| dAG749 | PHO11 | LEU2 |

| dAG786 | LEU2 | PHO11 |

| dAG1051 | PHO11 | URA3 |

| dAG1052 | URA3 | PHO11 |

| ndj1Δ HDF1c | ||

| dAG546 | PHO11 | PHO11 |

| dAG547 | PHO12 | PHO12 |

| dAG548 | PHO11 | PHO12 |

| dAG581 | PHO12 | PHO11 |

| dAG585 | URA3 | URA3 |

| dAG586 | PHO12 | URA3 |

| dAG591 | URA3 | PHO12 |

| dAG587 | URA3 | PHO11 |

| dAG588 | PHO11 | URA3 |

| dAG612 | PHO11 | YHL044W |

| dAG622 | YHL044W | PHO11 |

| dAG618 | URA3 | PPX1 |

| dAG741 | PPX1 | URA3 |

| dAG651 | YHL044W | YHL044W |

| dAG663 | URA3 | HIS4 |

| dAG674 | HIS4 | URA3 |

| dAG683 | HIS4 | HIS4 |

| dAG737 | PPX1 | PPX1 |

| ndj1Δ hdf1Δd | ||

| dAG338 | URA3 | URA3 |

| dAG339 | URA3 | PHO11 |

| dAG340 | PHO11 | URA3 |

| dAG341 | PHO11 | PHO11 |

| dAG504 | PHO11 | PHO12 |

| dAG505 | PHO12 | PHO11 |

| dAG506 | PHO12 | PHO12 |

| dAG596 | URA3 | PHO12 |

| dAG597 | PHO12 | URA3 |

| dAG629 | URA3 | HIS4 |

| dAG690 | HIS4 | URA3 |

| dAG657 | PHO11 | YHL044W |

| dAG665 | YHL044W | PHO11 |

| dAG675 | YHL044W | YHL044W |

| dAG692 | HIS4 | HIS4 |

| dAG731 | PPX1 | URA3 |

| dAG830 | URA3 | PPX1 |

| dAG829 | PPX1 | PPX1 |

| dAG1080 | URA3 | MAT |

| dAG1085 | MAT | URA3 |

| dAG1084 | MAT | MAT |

| dAG1086 | URA3 | LEU2 |

| dAG1089 | LEU2 | URA3 |

| dAG1090 | CHA1 | PHO11 |

| dAG1098 | PHO11 | CHA1 |

| dAG1092 | LEU2 | LEU2 |

| dAG1099 | PHO12 | CHA1 |

| dAG1105 | CHA1 | PHO12 |

| dAG1100 | CHA1 | CHA1 |

| Locus with:

| ||

| VDE-induced DSBe | arg4-vde | arg4-bgl |

| dAG388 | URA3 | LEU2 |

| dAG389 | URA3 | PUT2 |

| dAG482 | URA3 | PHO12 |

| dAG512 | URA3 | PHO11 |

| dAG513 | URA3 | PPX1 |

| dAG527 | URA3 | HIS4 |

| dAG535 | URA3 | URA3 |

| dAG787 | URA3 | MAT |

| dAG789 | URA3 | THR1 |

| dAG792 | URA3 | YHL044W |

All strains are MATa/α diploids and homozygous for HO:: LYS2 lys2 leu2 ura3 arg4-nsp,bgl, unless otherwise stated.

Translocation chromosome breakpoints are as follows (Tel, telomere; L and R, left and right arm, respectively): IIII, CEN1-pho11::hisG-his4-TelIIIL; IIII, CEN3-his4::ade2-pho11-TelIR; IIIV, CEN3-cha1::ade2-gea2-TelVR; VIII, CEN5-gea2::hisG-cha1-TelIIILIIIVIII, CEN3-his4::ade2-pho12-TelVIIIR; VIIIIII, CEN8pho12::hisG-his4-TelIIIL. Translocations are illustrated in Figure 2.

All ndj1Δ HDF1 strains are ndj1Δ::KanMX/ndj1Δ::KanMX.

All ndj1Δ Δhdf1 strains are ndj1Δ::KanMX6/ndj1Δ::KanMX6 hdf1Δ::KanMX6/hdf1Δ::KanMX6.

All strains with the ura3::arg4-vde allele are TFP1::VDE1/TFP1 ade2/ADE2 trp1::hisG nuc1Δ::LEU2/nuc1Δ::LEU2.

Random spore analysis of diploid strains was performed as described Lichten et al. (1987). The f(Arg+) were determined and converted into efficiencies of ectopic recombination as described in detail in Goldman and Lichten (1996). Briefly, the formula for efficiency of ectopic recombination takes into account the allelic f(Arg+) at both insert loci used and the ectopic f(Arg+) in both marker configurations for the two loci used (i.e., with arg-nsp at locus 1 and arg4-bgl at locus 2 and with arg-bgl at locus 1 and arg4-bgl at locus 2). For each pairwise combination the efficiency of ectopic recombination contains data from four separate crosses and is the ratio between the sum of the two ectopic f(Arg+) divided by the sum of the two allelic f(Arg+), multiplied by a correction factor that takes into account the fraction of Arg+ recombinants expected to reside in inviable translocation segregations (details in Goldman and Lichten 1996). There are no essential genes distal to the arg4 alleles located at AAD3 and YHL044W, so deletion of regions distal to these loci due to unbalanced segregation of translocations has no affect on viability. There are essential genes distal to PPX1 and therefore f(Arg+) for crosses with this locus were adjusted as described for other interstitial loci (Goldman and Lichten 1996). The f(Arg+) used in calculating the efficiencies of ectopic recombination was the mean of at least two repeat trials with standard deviation of no more than 10% of the mean.

The efficiency of ectopic recombination, induced by a VDE-DSB, was calculated differently as practically all recombination was initiated from the arg4-vde allele. The ectopic f(Arg+) for ura3::arg4-vde recombining with a dispersed arg4-bgl allele was divided by the allelic recombination frequency for arg4-vde and ura3::arg4-bgl alleles. The ectopic recombination frequencies were corrected for loss of Arg+ colonies due to unbalanced segregation of crossovers according to Goldman and Lichten (1996). For VDE-initiated recombination, the proportion of gene conversion events associated with a crossover is 50%, as for Spo11-induced recombination (M. J. Neale, M. Ramachandran and A. S. H. Goldman, unpublished observations).

RESULTS

The experiments reported here examine ectopic recombination between arg4 mutant alleles (arg4-nsp and arg4-bgl) present on an 8.5-kb URA3-arg4 insert (Figure 1A). We determined the frequency of Arg+ meiotic recombinants from diploids with an arg4-nsp-containing insert at one locus and an arg4-bgl-containing insert at another. Twelve different insert loci were used (Figure 2A). Including previously published data (Wu and Lichten 1995; Goldman and Lichten 1996), a total of 80 and 48 pairwise combinations have been examined in wild-type and modified cells, respectively. Insert loci that are 60 kb, or more, from their nearest telomere were classified as interstitial; all other loci are referred to as subtelomeric. For each pairwise combination, we calculated the efficiency of ectopic recombination (Goldman and Lichten 1996; see also materials and methods). The efficiency of ectopic recombination provides a measure of the likelihood that two dispersed inserts will encounter each other and recombine. An ectopic recombination efficiency of 1.0 indicates that two dispersed inserts are as likely to recombine with each other as they would with an allelic insert. Efficiencies of ectopic recombination <1.0 indicate that inserts are less likely to recombine when dispersed than when in allelic configurations.

Figure 1.—

Structure of arg4-containing plasmid inserts and explanation of SIDT. (A) Plasmids contained pBR322 sequences (thick line), a 3.3-kb arg4 fragment (shaded box) marked with either arg4-nsp or arg4-bgl mutant alleles, a 1.2-kb URA3 fragment (open box), and locus-specific sequences to direct integration (abc′ and ′abc; xyz′ and ′xyz). In diploids used to examine ectopic recombination, these constructs introduced 8.5 kb of homology between otherwise unrelated loci (Wu and Lichten 1995; Goldman and Lichten 1996). (B) In experiments using a VDE-induced DSB to stimulate ectopic recombination, the same basic construct was used except that one arg4 allele (arg4-vde) has a VDE cut site inserted at the EcoRV site of ARG4 (see Neale et al. 2002). In all such experiments, the arg4-vde-containing cassette was inserted at the ura3 locus. (C) SIDT is calculated by summing the distances of each insert from the nearest telomere; in this example, SIDT = d1 + d2.

Figure 2.—

Insert loci and reciprocal translocations. (A) All loci used in these experiments, with distances from the nearest telomere (in kilobases). The GEA2 locus was used only in creating the IIIV/VIII reciprocal translocation (RT). (B–D) Three different RTs were constructed; the shaded lines indicate translocated segments. RTs between chromosomes VIII and III (B) and between chromosomes I and III (C) move the LEU2 locus 64 and 57 kb closer, respectively, to the nearest telomere. (D) The RT between chromosomes III and V brings the URA3 locus 98 kb closer to the nearest telomere.

Interstitial inserts brought close to a telomere by reciprocal translocation behave like subtelomeric inserts:

Our previous observation of increased ectopic recombination between sequences near telomeres was based on studies using only three subtelomeric inserts. To confirm that this effect was not a fortuitous property of the three loci used, we examined two additional insert loci in subtelomeric regions (AAD3, right end of chromosome III, and YHL044W, left end of chromosome VIII; Figure 2A). We also converted three interstitial loci into subtelomere proximal loci, using reciprocal translocations (RTs; described in materials and methods) in which arg4 inserts normally located in interstitial sequences were brought closer to a telomere (Figure 2, B–D). To avoid complexities caused by unbalanced segregation of heterozygous RTs, ectopic recombination involving these novel subtelomeric arg4 inserts was monitored in strains homozygous for the RT. Two RTs, between chromosome III and chromosomes I or VIII, were used to bring inserts at LEU2 closer to a telomere. LEU2, which is normally 86 kb from the left telomere of chromosome III, became either 29 kb from the right telomere of chromosome VIII (chromosome IIIVIII; Figure 2B), or 22 kb from the right telomere chromosome I (chromosome IIII; Figure 2C). A third RT, between chromosomes V and III, was used to bring ura3::arg4, normally 117 kb from the right telomere of chromosome V, to 19 kb from the chromosome III right telomere (chromosome VIII; Figure 2D).

Frequencies of ectopic recombination were measured in crosses involving new inserts in native subtelomeric regions (aad3::arg4 and yhl044w::arg4) and in crosses involving the newly subtelomeric loci. The data, once converted to efficiencies of ectopic recombination (Tables 2 and 3), support the previous suggestion that homologous sequences near the ends of heterologs are more likely than interstitial loci to recombine ectopically (Goldman and Lichten 1996). Previous data involving three pairwise ectopic combinations of three subtelomeric loci (PHO11, PHO12, and CHA1) yielded a mean efficiency of ectopic recombination of 0.25 ± 0.03, as compared to a mean efficiency of ectopic recombination between interstitial loci of 0.15 ± 0.06 (Goldman and Lichten 1996). With the addition of the two new subtelomeric insert loci, the average efficiency of ectopic recombination between subtelomeric loci remained high (0.30 ± 0.09, 10 pairwise combinations).

TABLE 2.

Efficiencies of ectopic recombination and allelic recombination frequencies induced by Spo11 in wild-type strains

| Insert loci | >AAD3 | >PHO11 | >PHO12 | >YHL044W | >CHA1 | >PPX1 | >HIS4 | >LEU2 | <MAT | >URA3 | >THR1 | >PUT2 | <PUT2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| >AAD3 | 0.85 | 0.27 | 0.38 | 0.45 | 0.38 | 0.35 | 0.20 | 0.12 | 0.16 | 0.13 | 0.08 | 0.09 | ND |

| >PHO11 | 4.2 | 0.24 | 0.17 | 0.27 | 0.27 | 0.21 | 0.13 | 0.12 | 0.079 | 0.06 | 0.09 | ND | |

| >PHO12 | 1.6 | 0.29 | 0.28 | 1.0 | 0.21 | 0.13 | 0.15 | 0.064 | 0.17 | 0.16 | ND | ||

| >YHL044W | 4.1 | 0.22 | 0.47 | 0.34 | ND | 0.12 | 0.05 | 0.24 | ND | ND | |||

| >CHA1 | 4.7 | 0.32 | 0.84 | 0.56 | 0.4 | 0.21 | 0.068 | ND | 0.14 | ||||

| >PPX1 | 3.5 | 0.30 | 0.19 | 0.2 | 0.12 | 0.21 | 0.29 | ND | |||||

| >HIS4 | 16.0 | 0.95 | 0.55 | 0.18 | 0.12 | 0.18 | 0.17 | ||||||

| >LEU2 | 19.0 | 0.48 | 0.13 | 0.067 | 0.11 | 0.1 | |||||||

| <MAT | 9.4 | 0.12 | 0.15 | ND | 0.087 | ||||||||

| >URA3 | 5.7 | 0.085 | ND | 0.058 | |||||||||

| >THR1 | 6.6 | 0.47 | 0.99 | ||||||||||

| >PUT2 | 5.7 | ND | |||||||||||

| <PUT2 | 5.6 |

Row and column headers indicate loci containing the URA3-arg4 insert, in order of increasing distance from the nearest telomere; “>” and “<” indicate insert orientation relative to the centromere, with “>” indicating transcription toward the centromere for both genes. Efficiencies of ectopic recombination for insert locus pairs are above the diagonal. Allelic recombination frequencies (×103) are underlined. The values in italics are previously unpublished data; all other values are from Goldman and Lichten (1996).

TABLE 3.

Allelic recombination frequencies and efficiencies of ectopic recombination in strains homozygous for different reciprocal translocations, compared to SIDT

| Location of arg4 heteroalleles

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Translocation background | Chromosomes | Loci | Allelic recombination frequencya × 103 |

Efficiency of ectopic recombination |

SIDT (kb) |

| IIIVIII and VIIIIII | I | PHO11 | 2.8 (0.6) | ||

| (Figure 2B) | IIIVIII | LEU2 | 19 (1.0) | ||

| V | URA3 | 5.4 (1.0) | |||

| I × IIIVIII | PHO11 × LEU2 | 0.16 (1.2) | 33 | ||

| I × V | PHO11 × URA3 | 0.11 (1.0) | 121 | ||

| IIII and IIII | IIII | LEU2 | 14 (0.7) | ||

| (Figure 2C) | V | URA3 | 5.9 (1.0) | ||

| VIII | PHO12 | 1.9 (1.2) | |||

| IIII × VIII | LEU2 × PHO12 | 0.21 (1.7) | 32 | ||

| V × VIII | URA3 × PHO12 | 0.066 (1.0) | 127 | ||

| IIIV and VIII | I | PHO11 | 4.1 (0.9) | ||

| (Figure 2D) | VIII | URA3 | 1.2 (0.2) | ||

| VIII | PHO12 | 1.6 (1.0) | |||

| VIII | YHL044W | 3.4 (0.8) | |||

| VIII × VIII | URA3 × PHO12 | 0.21 (3.3) | 29 | ||

| VIII × VIII | URA3 × YHL044W | 0.12 (2.3) | 33 | ||

| I × VIII | PHO11 × PHO12 | 0.24 (1.0) | 14 | ||

The numbers in parentheses are fold-change compared to wild type. Note that changes in allelic recombination on normal chromosomes in the translocation background indicate interchromosomal effects. Allelic recombination frequencies in the context of translocations were used to calculate accurate efficiencies of ectopic recombination in the translocation containing strains. Translocations are illustrated in Figure 2.

ARG4 spores/total spores.

Experiments involving newly subtelomeric loci further support the view that proximity to a telomere influences the efficiency of ectopic meiotic recombination. In three of the four experiments involving a RT, there was an increase in the efficiency of ectopic recombination between the loci close to a translocated telomere and other naturally subtelomeric inserts (Table 3). The greatest increases (2.3- and 3.3-fold) were seen with the locus brought closest to a telomere (ura3::arg4, 19 kb from a telomere on chromosome VIII); the leu2::arg4 locus brought 22 kb from a telomere on chromosome IIII showed an intermediate effect (1.7-fold increase), while the leu2::arg4 locus brought 29 kb from a telomere did not display a significant increase. In control experiments using the same RTs, the efficiency of ectopic recombination involving loci on nontranslocated chromosomes was not affected (Table 3). In other words, the influence of RTs on the efficiency of ectopic recombination was specific to loci that moved closer to a chromosome end and correlated with the distance to the nearest telomere.

Inserts near opposite telomeres on homologs also show an increased likelihood to recombine:

Earlier studies of ectopic recombination found that the efficiency of ectopic recombination between homologs decreases as a function of distance between insert loci (Goldman and Lichten 1996). This finding, in particular, led to the suggestion that homologous chromosomes are, on average, in some form of end-to-end alignment at the time that sequences commit to recombine with each other. If, however, insert proximity to a telomere is critical in regulating the efficiency of ectopic recombination, then the relationship of distance between insert loci on homologs and efficiency of ectopic recombination should break down when both inserts are closer to opposite telomeres than to each other. This suggestion was tested using new insert loci at opposite ends of chromosomes III (AAD3) and VIII (YHL044W) from subtelomeric insert sites previously used on these two chromosomes.

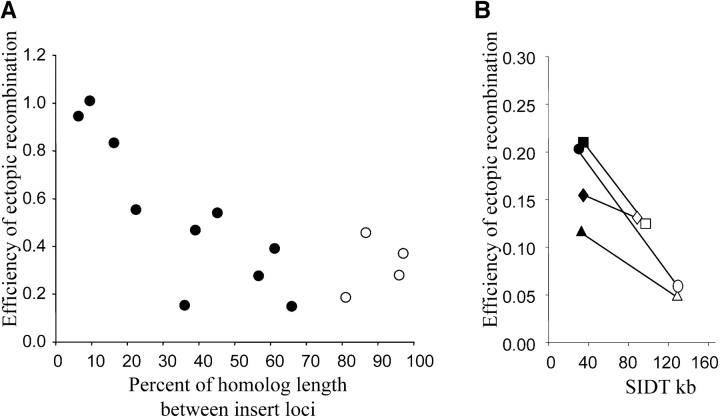

We compared the efficiencies of ectopic recombination between insert pairs separated by various proportions of chromosome length on homologous chromosomes (Figure 3A). When the distance between inserts increased from 6 to 65% of chromosome length, the efficiency of ectopic recombination decreased sixfold in an almost linear fashion. At this point, the efficiency of ectopic recombination between inserts on homologs approaches the lowest efficiency of ectopic recombination obtained between heterologs. At greater separations, the efficiency of ectopic recombination did not decrease further, but increased again to levels typical for efficiencies of ectopic recombination between subtelomeric inserts on heterologs. In other words, inserts close to opposite telomeres on homologs are more likely to recombine with each other than are other interstitial inserts that are separated by a smaller proportion of the chromosome length. This supports the view that opposite ends of a homologous pair are in the same nuclear compartment as other heterologous telomeres when sequences commit to recombine with each other.

Figure 3.—

The efficiency of ectopic recombination depends on insert distance from telomeres. (A) Efficiencies of ectopic recombination between homologous chromosomes plotted against linear distance between insert loci, expressed as the percentage of total chromosome length. There is a negative correlation between the efficiency of ectopic recombination and the distance between inserts separated by up to 65% of the chromosome (solid circles). When both inserts are close to opposite telomeres (open circles), i.e., separated by at least 80% of the chromosome length, the negative correlation breaks down and the efficiency of ectopic recombination is greater than expected. (B) In reciprocal translocation (RT) strains, the efficiency of ectopic recombination is greater than that in normal strains with the same inserts, in accordance with the decrease in SIDT. Open symbols are data points from wild-type strains for insert locus pairs that were subsequently used in RT experiments. The corresponding solid symbols are efficiencies of ectopic recombination after SIDT has been reduced by RT. Diamonds, inserts at PHO11 and LEU2, RT IIIVIII and VIIIIII; squares, inserts at LEU2 and PHO12, RT IIII and IIII; triangles, inserts at URA3 and YHL044W, RT IIIV and VIII; circles, inserts at URA3 and PHO12, RT IIIV and VIII.

The efficiency of ectopic recombination between inserts on heterologous chromosomes decreases with distance from the nearest telomere:

In addition to the elevated efficiency of ectopic recombination seen between inserts located close to telomeres, later analyses indicated a relationship between ectopic recombination efficiencies and insert distance from the nearest telomere. To examine this relationship further, we compared efficiencies of ectopic recombination between inserts on heterologous chromosomes to the sum of insert distances from their nearest telomere (SIDT; Figure 4). This relationship is most obvious when sets of insert combinations are examined with recombination between a single insert near a telomere and a number of interstitial inserts. In each of five cases (AAD3, Figure 4A; PHO12, Figure 4B; YHL044W, Figure 4C; PHO11, Figure 4D; CHA1, Figure 4E), the efficiency of ectopic recombination decreases with increasing SIDT, implying that accessibility of an insert to the proposed subtelomeric nuclear compartment is significantly reduced as the insert is located farther away.

Figure 4.—

Efficiencies of ectopic recombination between inserts on heterologous chromosomes plotted against SIDT: The data plotted are from this report and previously published results (Table 2). (A–E) When one insert is located close to a telomere (i.e., at PHO11, 4 kb; PHO12, 10 kb; YHL044W, 14 kb; AAD3, 2 kb; and CHA1, 17 kb) and the other insert is from 2 to 183 kb from the nearest telomere, there is a negative correlation between the efficiency of ectopic recombination and SIDT. (F) When both inserts are far (62–183 kb) from the nearest telomere (solid circles), there is also a negative correlation between efficiency of ectopic recombination and SIDT. The data from A–E are compiled in F for comparison (shaded circles). When the SIDT values for the two categories coincide, i.e., are between 120 and 180 kb, the efficiency of ectopic recombination is higher when both inserts are relatively far from the nearest telomere.

The same relationship is also apparent when ectopic recombination between two interstitial inserts is examined (Figure 4F; solid circles). Again, there is a negative correlation between the efficiency of ectopic recombination and SIDT (P < 0.001, linear regression). In other words, distance from telomeres exerts influence on ectopic recombination over hundreds of kilobases, a much longer range than previously demonstrated.

Comparison of ectopic recombination efficiencies when both inserts are interstitial with those where at least one insert is subtelomeric (compare solid vs. open circles in Figure 4F) provides further important, and unexpected, information. The two data sets do not overlap, and where SIDT values are in common (120–200 kb) the efficiency of ectopic recombination is greater when both inserts are interstitial compared to when one insert is subtelomeric. In other words, when two inserts are far from the nearest telomere, they are more likely to encounter each other than when one insert is very close to and the other insert is very far from the nearest telomere. Thus, ectopic recombination between interstitial inserts can be highly efficient, and over the range studied it varies with distance from the nearest telomere.

The robust nature of the relationship between SIDT and efficiency of ectopic recombination is further illustrated by the RT strains described earlier. The RTs cause inserts at LEU2 and URA3, which were classified as interstitial, to become subtelomeric (Figure 2, B–D). The decrease in SIDT in the RT strains is associated with an increase in efficiency of ectopic recombination as predicted from the trend observed for naturally subtelomeric loci (Figure 3B).

Position effects in ectopic meiotic recombination are independent of the mode of initiation:

We interpret the correlates described above as being due to spatial compartmentalization on the basis of insert distances to the nearest telomere. It is possible, however, that some other property of meiotic chromosomes relating to telomeres was responsible for the observed effects. For example, the propensity for DSBs to repair by ectopic recombination might have been influenced by locus-dependent DSB frequencies or by the time at which the DSBs form, which in turn is related to replication timing (Borde et al. 2000). Since interstitial sequences tend to be relatively early replicating and to display greater DSB frequencies compared to sequences near telomeres (McCarroll and Fangman 1988; Ferguson and Fangman 1992), it is possible that these factors contribute to the observed SIDT effect. To remove these potential sources of variation, we made use of an arg4-vde allele. Recombination at arg4-vde is induced by a site-specific DSB created by the VDE, whose recognition sequence is inserted within ARG4 coding sequences (Neale et al. 2002). The arg4-vde allele was inserted at the ura3 locus and ectopic recombination was measured using nine different loci containing the arg4-bgl allele as donor (Table 4; Figure 5A). Because the VDE-DSB arises in close to 100% of cells, recombination initiated by the VDE-DSB outweighs that initiated by Spo11-DSBs by up to two orders of magnitude (Table 4; Neale et al. 2002). Thus, initiation events at arg4-bgl insert loci are not expected to contribute significantly to recombinants. The ura3::arg4-vde locus creates a constant recipient locus, so its ability to encounter the various arg4-bgl insert loci directly determines the efficiency of ectopic recombination. In general, there is a significant increase in efficiency of ectopic recombination when recombination is induced by VDE, demonstrating for the first time that DSB frequency influences the efficiency of ectopic recombination.

TABLE 4.

Recombination frequencies and efficiencies of ectopic recombination induced by VDE-DSBs compared to SIDT

| Location of arg4 heteroalleles

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chromosomes | Insert locia | Recombination frequencyb × 102 | Efficiency of VDE- induced ectopic recombinationc |

SIDT (kb) |

| V | URA3 × URA3 | 6.7 | ||

| V × I | URA3 × PHO11 | 1.0 | 0.30 (3.9) | 121 |

| V × VIII | URA3 × PHO12 | 1.1 | 0.19 (3.0) | 127 |

| V × VIII | URA3 × YHL044W | 2.0 | 0.36 (7.2) | 131 |

| V × VIII | URA3 × PPX1 | 2.2 | 0.53 (4.6) | 179 |

| V × III | URA3 × HIS4 | 4.6 | 1.10 (6.1) | 184 |

| V × III | URA3 × LEU2 | 1.9 | 0.46 (3.4) | 203 |

| V × III | URA3 × MAT | 3.0 | 0.72 (5.9) | 230 |

| V × VIII | URA3 × THR1 | 2.4 | 0.58 (6.8) | 277 |

| V × VIII | URA3 × PUT2 | 1.6 | 0.48 (8.2) | 300 |

In all cases the VDE-DSB was formed in a ura3::arg4-vde allele.

Inserts at URA3 contained arg4-vde and inserts at the second locus contained arg4-bgl.

ARG4 spores/total spores.

Efficiencies of ectopic recombination were calculated by dividing the ectopic recombinant frequency by the allelic recombinant frequency after adjusting for loss of recombinants due to crossing over, which occurs at similar rates as for Spo11-DSBs (M. J. Neale, M. Ramachandran and A. S. H. Goldman, unpublished observations). Numbers in parentheses are ratios of efficiencies of VDE-induced ectopic recombination relative to efficiencies of Spo11-induced ectopic recombination between arg4-nsp and arg4-bgl (Table 2).

Figure 5.—

The correlation between efficiency of ectopic recombination and SIDT is independent of timing and frequency of DSB formation and of both NDJ1 and HDF1 (yKu70) function. (A and B) Spo11-induced recombination in wild-type cells, extracted from Figure 3F, is shown in light shading for reference (all open symbols indicate at least one subtelomeric insert; all closed symbols indicate interstitial inserts only). (A) The efficiency of ectopic recombination stimulated by a VDE-DSB plotted against SIDT and compared to Spo11-induced efficiencies of ectopic recombination for the same loci. The similarity in shape between the two graphs indicates that SIDT influences the efficiency of ectopic recombination even when the DSB frequency is close to 100%. (B) The efficiency of ectopic recombination in homozygous Δndj1 HDF1 and homozygous Δndj1 Δhdf1 strains plotted against SIDT and compared to wild-type cells. Deleting NDJ1 increases the efficiency of ectopic recombination similarly across the range of experiments; thus the influence of SIDT remains. The influence of SIDT also remains when both NDJ1 and HDF1 are deleted.

To determine whether or not the relationship between efficiency of ectopic recombination and SIDT remains for VDE-induced recombination, we compared VDE-induced and Spo11-induced ectopic recombination efficiencies as a function of SIDT (Figure 5A). The VDE-induced and Spo11-induced data sets are highly correlated (Pearson correlation coefficient r = 0.83, P < 0.005), with the lowest ectopic recombination efficiencies being seen for crosses involving inserts at ura3 and inserts at subtelomeric loci. This similarity indicates that the general relationship between efficiency of ectopic recombination and SIDT is maintained, even when there is no locus-dependent variation in the timing or frequency of DSB formation (because there is a single recipient locus) and the DSBs in the population are highly abundant. Thus, while DSB frequency can influence the efficiency of ectopic recombination, there are still overriding limiting factors related to telomere proximity that affect the accessibility of dispersed sequences to each other.

The effect of telomere proximity on ectopic recombination is not eliminated by reducing bouquet formation:

Two known levels of telomere organization could create a spatial compartmentalization responsible for the negative correlation between efficiency of ectopic recombination and SIDT. The first is the localization and grouping of telomeres in a limited number of clusters around the nuclear periphery, which is seen both during vegetative growth and in early meiosis I prophase (Klein et al. 1992; Laroche et al. 1998; Trelles-Sticken et al. 2000). The second is the bouquet stage of meiosis I prophase, in which all chromosome ends are more tightly restricted to a small portion of the nuclear periphery. The enrichment of local telomere concentration in the bouquet could effectively cause them to be in a discrete nuclear compartment, separated from most interstitial regions. This, in turn, could create a barrier to ectopic interaction between loci close to and far from telomeres. To test this idea, we deleted the NDJ1 gene, which is required in S. cerevisiae for both bouquet formation and the normal timing of chromosome pairing and synapsis (Chua and Roeder 1997; Conrad et al. 1997; Trelles-Sticken et al. 2000).

As previously demonstrated, ndj1Δ mutants show a general increase in the efficiency of ectopic recombination between arg4 inserts dispersed on heterologs (Table 5; Goldman and Lichten 2000). The increased data set makes possible a comparison of efficiencies of ectopic recombination in relation to SIDT. The relationship is maintained in ndj1Δ cells, which exhibit an almost identical pattern of behavior compared to wild-type cells (Figure 5B, Pearson correlation coefficient r = 0.7, P < 0.002). Thus, the transient telomere-rich area, created by the bouquet structure, appears to have no influence on the negative correlation between the efficiency of ectopic recombination and SIDT.

TABLE 5.

Recombination frequencies and efficiencies of ectopic recombination inndj1Δ mutant strains compared to SIDT

| Location of arg4 heteroalleles

|

Allelic recombination frequencya × 103

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chromosomes | Loci | NDJ1 | ndj1Δ | ndj1Δ hdf1Δ | |

| I | PHO11 | 4.2b | 3.9 (0.93) | 4.4 (1.0) | |

| III | HIS4 | 17b | 20 (1.2) | 18 (1.1) | |

| LEU2 | 19b | 19b (1.0) | 40 (2.1) | ||

| MAT | 7.4b | 7.4b (1.0) | 6.8 (0.92) | ||

| CHA1 | 5.0b | 5.0b (1.0) | 11 (2.2) | ||

| V | URA3 | 5.7b | 9.3 (1.6) | 7.9 (1.4) | |

| VIII | PHO12 | 1.6b | 1.0 (0.63) | 1.6 (1.0) | |

| PPX1 | 3.5 | 6.8 (1.9) | 4.4 (1.3) | ||

| YHL044W | 4.1 | 3.9 (0.95) | 4.5 (1.1) | ||

| Location of arg4 heteroalleles

|

Ectopic recombination efficiency

|

||||

| Chromosomes | Loci | NDJ1 | ndj1Δ | ndj1Δ hdf1Δ | SIDT (kb) |

| I × VIII | PHO11 × PHO12 | 0.24b | 0.51b (2.1) | 0.36b (1.5) | 14 |

| I × VIII | PHO11 × YHL044W | 0.17 | 0.58 (3.4) | 0.36 (2.1) | 18 |

| I × III | PHO11 × CHA1 | 0.27b | 0.59b (2.2) | 0.51 (1.9) | 21 |

| III × VIII | CHA1 × PHO12 | 0.28b | 0.57b (2.0) | 0.52 (1.9) | 27 |

| I × V | PHO11 × URA3 | 0.079b | 0.31 (3.9) | 0.18 (2.3) | 121 |

| V × VIII | URA3 × PHO12 | 0.064b | 0.29 (4.5) | 0.18 (2.8) | 127 |

| V × VIII | URA3 × PPX1 | 0.12 | 0.22 (1.8) | 0.20 (1.7) | 179 |

| III × V | HIS4 × URA3 | 0.18b | 0.41 (2.3) | 0.32 (1.8) | 184 |

| III × V | LEU2 × URA3 | 0.13b | 0.29b (2.2) | 0.15 (1.2) | 203 |

| III × V | MAT × URA3 | 0.12b | 0.29b (2.4) | 0.23 (1.9) | 230 |

ARG4 spore/total spores.

Previously published values (Goldman and Lichten 1996, 2000). Numbers in parentheses are relative to wild type.

Perturbation of telomere metabolism by deletion of yKu70 does not influence the SIDT effect:

Following the finding that the negative correlation between SIDT and the efficiency of ectopic recombination is independent of Ndj1 activity, we considered other ways to perturb telomere metabolism. We deleted the yKu70 homolog, HDF1, which is required for maintenance of normal telomere length and had previously been reported to influence localization of telomeres to the nuclear envelope (Laroche et al. 1998). In fact, it has become clear that yKu homologs mainly influence telomere localization during G1-phase and less so during S-phase and G2-phase (Hediger et al. 2002; Taddei and Gasser 2004; Taddei et al. 2004). In addition to this, the affect of yKu knockouts on telomere localization varies by chromosome (Hediger et al. 2002). Consequently, the deletion of HDF1 is expected to affect telomere length, but may not have a major influence on telomere localization during recombination, which initiates after DNA replication (Borde et al. 2000). Disrupting Hdf1 function alone has little effect on either allelic or ectopic meiotic recombination (data not shown); cells lacking both Hdf1 and Ndj1 (hdf1Δ ndj1Δ in Figure 5B) display the same general correlation between SIDT and the efficiency of ectopic recombination as wild-type or ndj1Δ single mutants (Pearson correlation coefficient r = 0.9, P < 0.001).

DISCUSSION

The efficiency of ectopic recombination is limited by insert distance from the nearest telomere:

Previous studies of meiotic recombination in S. cerevisiae have shown that the position of interacting sequences can modulate ectopic recombination frequencies (Jinks-Robertson and Petes 1986; Lichten et al. 1987; Kupiec and Petes 1988; Lichten and Haber 1989; Louis et al. 1994; Goldman and Lichten 1996; Fischer et al. 2000). The most striking position effect is conferred by the distinction between homologous and heterologous chromosomes and probably reflects the restriction imposed on ectopic recombination by progressive homolog pairing and synapsis (Goldman and Lichten 2000; Niwa et al. 2000). More subtle position effects are illustrated by evidence that the efficiencies of ectopic recombination between inserts dispersed on heterologous chromosomes are nonuniform (Goldman and Lichten 1996). It is likely that such position effects reflect underlying disparity in both the average position and the mobility of different chromosomal regions within the nucleus. The ectopic recombination experiments presented here provide further information for assessing the spatial relationship between chromosomes at the time that sequences commit to recombine with each other. Our current analysis identifies a single property of a region—distance from the nearest telomere—as playing a limiting role in determining the ability of dispersed sequences to recombine with each other during meiosis. Our findings are summarized below.

First, dispersed sequences near the ends of heterologous chromosomes are more likely to recombine than dispersed sequences far from chromosome ends. This conclusion, obtained in an earlier study on the basis of three pairwise combinations of subtelomeric arg4 inserts (Goldman and Lichten 1996), has now been reinforced by the inclusion of two additional subtelomeric arg4 inserts (and thus seven additional pairwise combinations). The conclusion is further reinforced by the finding that arg4 inserts located in interstitial regions assume the properties of subtelomeric inserts when they are brought close to a chromosome end by reciprocal translocation. The latter experiments exclude locus-specific effects as the cause of higher efficiencies of ectopic recombination close to telomeres. The higher average efficiency of interheterolog ectopic recombination near telomeres brings it to within a factor of three of allelic recombination. This increased propensity for related sequences near heterologous chromosome ends to recombine could account for the relative lack of divergence between subtelomeric repeated sequence elements and the presence of subtelomeric multigene families (Louis et al. 1994; Pryde et al. 1997; Pryde and Louis 1997).

A new and unexpected finding is that the influence of telomere proximity extends to ectopic recombination between homologous sequences located interstitially. When efficiencies of ectopic recombination between inserts on heterologs are compared with the SIDT, the data fall into two categories, each of which produces a distinct trend of decreasing efficiencies of ectopic recombination with increasing SIDT (Figure 4F). In one category both inserts are interstitial (each is between 62 and 183 kb from the nearest telomere), and yet their distance from the nearest telomere still influences their ability to interact with each other. The observation that distance from chromosome ends limits the efficiency of ectopic meiotic recombination contrasts with results from experiments with Cre-mediated mitotic recombination between lox sites. In vegetative cells, it was found that the frequency of recombination for inserts on heterologous chromosomes is correlated with distance from respective centromeres (Burgess and Kleckner 1999). We looked for a correlation between the efficiency of meiotic ectopic recombination and distance to centromere, but found none (data not shown).

Several properties of meiotic chromosomes, all roughly correlated with physical distance from the telomere, could have been responsible for the SIDT effect. Chromosome ends tend to be late replicating (McCarroll and Fangman 1988; Ferguson and Fangman 1992; Friedman et al. 1995), and thus meiotic DSBs are expected to form later near telomeres than in interstitial regions (Borde et al. 2000); in addition, DSBs generally form more frequently in interstitial regions than near chromosome ends. Although both of these properties may make contributions, we believe it unlikely that they are the primary factors determining the negative correlation between efficiency of ectopic recombination and SIDT. The SIDT effect remains when the frequencies and efficiencies of ectopic recombination are maximized, using strains in which virtually all recombinants are initiated by a VDE-catalyzed DSB at a single locus (Figure 1B). For these strains, the time and level of initiating break formation are held constant. We also found that the efficiency of ectopic recombination between homologous chromosomes is similarly affected by insert distance from the chromosome ends. Taken together, these observations indicate that the SIDT effect reflects a direct influence of physical distance from the nearest telomere on the ability of different chromosome regions to interact with each other during meiosis.

Could localization of telomeres to the nuclear periphery explain the negative correlation between efficiency of ectopic recombination and SIDT?

The transient localization of telomeres during meiosis I prophase into a small region of the nuclear periphery, termed bouquet formation, has been observed in all organisms studied to date (Scherthan 2001). It has long been thought that the grouping of telomeres is important for chromosome pairing and subsequent synapsis (Loidl 1990). Recent studies in budding yeast and fission yeast lend support to this suggestion (Chua and Roeder 1997; Conrad et al. 1997; Rockmill and Roeder 1998; Niwa et al. 2000; Trelles-Sticken et al. 2000). It is also evident that DSB and bouquet formation occur at or around the same time (Trelles-Sticken et al. 1999; Storlazzi et al. 2003). The bouquet structure creates a telomere-rich area that could increase the likelihood of recombination subtelomeric sequences. But influence from this can be ruled out, since preventing formation of the bouquet (by deletion of the NDJ1 gene) fails to abolish the SIDT effect. We can also rule out the need for normal control of telomere length for creating the SIDT effect, since deleting HDF1 does not eliminate the trend.

Another important property of telomeres is that they are associated with the nuclear envelope throughout S-phase and G2-phase of the cell cycle (see Taddei et al. 2004). Much of our data could be explained if attachment of telomeres to the nuclear periphery restricts their mobility to move in two dimensions, consequentially limiting the fraction of nuclear volume that they can search (modeled in Figure 6). Two-dimensional movement around the nuclear envelope could be sufficient to allow for a high frequency of interaction between subtelomeric inserts (Loidl 1990). Interstitial inserts are expected to have more freedom to move (i.e., in three dimensions), but have the potential to occupy a larger proportion of the total available volume. We suggest that the balance of these two variables—freedom to move and volume occupied—defines the ability of dispersed sequences to locate each other.

Figure 6.—

Localization of telomeres to the nuclear periphery could explain the SIDT effect. (A–E) The nuclear membrane in represented by the outer solid circle. The effective nuclear radius of 165 kb is based on the experimental finding that, when one insert is close to a telomere, minimum efficiencies of ectopic recombination are seen when the second insert is ∼165 kb from its closest telomere. The solid squares represent insert loci on heterologous chromosomes, and the concentric dashed-and-dotted circles represent shells within the nuclear space that are effectively limits to movement toward the center for the loci diagrammed next to them. The limit to movement toward the periphery, for any locus, is the nuclear envelope. A locus can occupy the space between these two limits. (F) The letters A–E correspond to the approximate levels of efficiency of ectopic recombination expected from the preceding scenarios and are overlaid on the data set from Figure 4F. Various situations that lead to changes in SIDT are modeled: the relative mobility of different loci and the proportion of total nuclear volume that loci might occupy. (A) When two inserts are close to a telomere, they have little ability to move in three dimensions, but are in a relatively small volume and therefore recombine efficiently. (B and C) When one insert is close to a telomere and the other is interstitial, ectopic recombination would depend on the more telomere-distal insert being able to move to the region near the nuclear periphery where telomeric inserts are confined. As the distance between the telomere and the interstitial insert increases, the volume that could be occupied by the interstitial insert also increases, reducing the chance of interaction between the two sequences. (D and F) Similarly when both inserts are interstitial, moving them progressively further from a telomere increases the three-dimensional space in which they might reside. As a consequence the likelihood of ectopic contacts decreases.

An important feature of the current data set is that ectopic recombination between inserts distant from a telomere can be relatively efficient. In fact, for a given SIDT, ectopic recombination is more efficient when both inserts are distant from the nearest telomere than when one insert is very close and the second is very far from the nearest telomere (compare letters C and D in Figure 6F). The model presented in Figure 6 can account for this feature. When one insert is close to a telomere and the other is interstitial, ectopic recombination requires the interstitial insert to search a large volume to locate the subtelomeric insert. For the same SIDT, when both inserts are moderately interstitial, they both have three-dimensional mobility and reside in a smaller volume than the single interstitial locus in the previous example. A relative increase in combined mobility of inserts, along with a reduction of the volume to be searched, would significantly increase the chance of ectopic recombination for two interstitial inserts, compared to when one is subtelomeric.

The model in Figure 6 is challenged by evidence that more telomeres are internalized during meiosis in ndj1Δ mutants (Trelles-Sticken et al. 2000), which we find maintain the SIDT effect. However, Trelles-Sticken et al. (2000) report that the number of telomeres in the nuclear periphery of ndj1Δ cells is ∼75% of the wild-type number. Thus, in ndj1Δ mutants there may be sufficient telomere-nuclear envelope association to cause the SIDT effect as modeled in Figure 6. Another possibility is that premeiotic and early meiotic telomere association with the nuclear envelope impose restrictions on the homology search before the time of Ndj1 activity. This seems feasible, bearing in mind the recent finding that a homology search leading to loose coalignment of Sordaria chromosomes precedes tight bouquet formation (Storlazzi et al. 2003; Tesse et al. 2003). It remains possible that either somatic/premeiotic pairing (Weiner and Kleckner 1994; Burgess et al. 1999) or as-yet-uncharacterized prebouquet meiotic homolog alignment contribute to the SIDT effect.

To test these suggestions, it is necessary to disrupt vegetative and very early meiotic telomere organization to determine whether or not this influences the ability of dispersed sequences to locate each other. We attempted this by deleting the yeast Ku70 homolog, HDF1, but found this had no influence on the SIDT effect. However, recent reports suggest that deletion of HDF1 may not be sufficient to disrupt all telomere anchoring during S-phase or later in the cell cycle (Hediger et al. 2002; Taddei and Gasser 2004; Taddei et al. 2004). A definitive test of the model presented in Figure 6 awaits further characterization of telomere association with the nuclear envelope during early meiosis and the ability to alter both telomere location and movement during this period.

It is highly likely that there are a number of contributing factors, some as yet unknown, that lead to the negative correlation between efficiency of ectopic recombination and SIDT. It is worth noting, however, that the net effect of a negative influence on the ability of sequences in different chromosome domains to interact could provide significant advantages to the cell. Recombination between repeated sequences in nonhomologous chromosome domains would create deleterious structural rearrangements. We suggest that the SIDT effect reflects the presence of a low-resolution mechanism that provides an initial partitioning of the genome early in meiosis. In yeast, this could serve to segregate chromosome domains during the dangerous period between DSB formation and substantive meiotic chromosome pairing.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Rhona Borts for providing plasmid coding for VDE, Katharine Coon for guidance on statistics, Gareth Jones and Sue Armstrong for insightful discussions, and Mathew North and Ayesha Johnson for technical assistance. Thanks also go to anonymous referees and Anne Villeneuve for comments that improved the manuscript. This work was supported by a Wellcome Trust grant to A.S.H.G.

References

- Abdullah, M. F., and R. H. Borts, 2001. Meiotic recombination frequencies are affected by nutritional states in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98: 14524–14529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrulis, E. D., A. M. Neiman, D. C. Zappulla and R. Sternglanz, 1998. Perinuclear localization of chromatin facilitates transcriptional silencing. Nature 394: 592–595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baudat, F., and A. Nicolas, 1997. Clustering of meiotic double-strand breaks on yeast chromosome III. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94: 5213–5218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Aroya, S., P. A. Mieczkowski, T. D. Petes and M. Kupiec, 2004. The compact chromatin structure of a Ty repeated sequence suppresses recombination hotspot activity in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. 15: 221–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borde, V., A. S. Goldman and M. Lichten, 2000. Direct coupling between meiotic DNA replication and recombination initiation. Science 290: 806–809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess, S. M., and N. Kleckner, 1999. Collisions between yeast chromosomal loci in vivo are governed by three layers of organization. Genes Dev. 13: 1871–1883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess, S. M., N. Kleckner and B. M. Weiner, 1999. Somatic pairing of homologs in budding yeast: existence and modulation. Genes Dev. 13: 1627–1641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chua, P. R., and G. S. Roeder, 1997. Tam1, a telomere-associated meiotic protein, functions in chromosome synapsis and crossover interference. Genes Dev. 11: 1786–1800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Civardi, L., Y. Xia, K. J. Edwards, P. S. Schnable and B. J. Nikolau, 1994. The relationship between genetic and physical distances in the cloned a1-sh2 interval of the Zea mays L. genome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91: 8268–8272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrad, M. N., A. M. Dominguez and M. E. Dresser, 1997. Ndj1p, a meiotic telomere protein required for normal chromosome synapsis and segregation in yeast. Science 276: 1252–1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cremer, T., and C. Cremer, 2001. Chromosome territories, nuclear architecture and gene regulation in mammalian cells. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2: 292–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dekker, J., K. Rippe, M. Dekker and N. Kleckner, 2002. Capturing chromosome conformation. Science 295: 1306–1311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan, Q. Q., and T. D. Petes, 1996. Relationship between nuclease-hypersensitive sites and meiotic recombination hot spot activity at the HIS4 locus of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16: 2037–2043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson, B. M., and W. L. Fangman, 1992. A position effect on the time of replication origin activation in yeast. Cell 68: 333–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feuerbach, F., V. Galy, E. Trelles-Sticken, M. Fromont-Racine, A. Jacquier et al., 2002. Nuclear architecture and spatial positioning help establish transcriptional states of telomeres in yeast. Nat. Cell Biol. 4: 214–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, G., S. A. James, I. N. Roberts, S. G. Oliver and E. J. Louis, 2000. Chromosomal evolution in Saccharomyces. Nature 405: 451–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, K. L., M. K. Raghuraman, W. L. Fangman and B. J. Brewer, 1995. Analysis of the temporal program of replication initiation in yeast chromosomes. J. Cell Sci. 19(Suppl.): 51–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gimble, F. S., and J. Thorner, 1992. Homing of a DNA endonuclease gene by meiotic gene conversion in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nature 357: 301–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman, A. S., and M. Lichten, 1996. The efficiency of meiotic recombination between dispersed sequences in Saccharomyces cerevisiae depends upon their chromosomal location. Genetics 144: 43–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman, A. S., and M. Lichten, 2000. Restriction of ectopic recombination by interhomolog interactions during Saccharomyces cerevisiae meiosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97: 9537–9542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grewal, S. I., and A. J. Klar, 1997. A recombinationally repressed region between mat2 and mat3 loci shares homology to centromeric repeats and regulates directionality of mating-type switching in fission yeast. Genetics 146: 1221–1238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hediger, F., F. R. Neumann, G. Van Houwe, K. Dubrana and S. M. Gasser, 2002. Live imaging of telomeres: yKu and Sir proteins define redundant telomere-anchoring pathways in yeast. Curr. Biol. 12: 2076–2089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin, Q., E. Trelles-Sticken, H. Scherthan and J. Loidl, 1998. Yeast nuclei display prominent centromere clustering that is reduced in nondividing cells and in meiotic prophase. J. Cell Biol. 141: 21–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jinks-Robertson, S., and T. D. Petes, 1986. Chromosomal translocations generated by high-frequency meiotic recombination between repeated yeast genes. Genetics 114: 731–752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jinks-Robertson, S., S. Sayeed and T. Murphy, 1997. Meiotic crossing over between nonhomologous chromosomes affects chromosome segregation in yeast. Genetics 146: 69–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein, F., T. Laroche, M. E. Cardenas, J. F. Hofmann, D. Schweizer et al., 1992. Localization of RAP1 and topoisomerase II in nuclei and meiotic chromosomes of yeast. J. Cell Biol. 117: 935–948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kupiec, M., and T. D. Petes, 1988. Allelic and ectopic recombination between Ty elements in yeast. Genetics 119: 549–559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laroche, T., S. G. Martin, M. Gotta, H. C. Gorham, F. E. Pryde et al., 1998. Mutation of yeast Ku genes disrupts the subnuclear organization of telomeres. Curr. Biol. 8: 653–656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichten, M., and J. E. Haber, 1989. Position effects in ectopic and allelic mitotic recombination in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 123: 261–268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichten, M., R. H. Borts and J. E. Haber, 1987. Meiotic gene conversion and crossing over between dispersed homologous sequences occurs frequently in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 115: 233–246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim, J. K., and M. J. Simmons, 1994. Gross chromosome rearrangements mediated by transposable elements in Drosophila melanogaster. BioEssays 16: 269–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loidl, J., 1990. The initiation of meiotic chromosome pairing: the cytological view. Genome 33: 759–778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louis, E. J., E. S. Naumova, A. Lee, G. Naumov and J. E. Haber, 1994. The chromosome end in yeast: its mosaic nature and influence on recombinational dynamics. Genetics 136: 789–802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarroll, R. M., and W. L. Fangman, 1988. Time of replication of yeast centromeres and telomeres. Cell 54: 505–513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery, E. A., S. M. Huang, C. H. Langley and B. H. Judd, 1991. Chromosome rearrangement by ectopic recombination in Drosophila melanogaster: genome structure and evolution. Genetics 129: 1085–1098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neale, M. J., M. Ramachandran, E. Trelles-Sticken, H. Scherthan and A. S. H. Goldman, 2002. Wild-type levels of Spo11-induced DSBs are required for normal single-strand resection during meiosis. Mol. Cell 9: 835–846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niwa, O., M. Shimanuki and F. Miki, 2000. Telomere-led bouquet formation facilitates homologous chromosome pairing and restricts ectopic interaction in fission yeast meiosis. EMBO J. 19: 3831–3840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parada, L., and T. Misteli, 2002. Chromosome positioning in the interphase nucleus. Trends Cell Biol. 12: 425–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parket, A., O. Inbar and M. Kupiec, 1995. Recombination of Ty elements in yeast can be induced by a double-strand break. Genetics 140: 67–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peoples, T. L., E. Dean, O. Gonzalez, L. Lambourne and S. M. Burgess, 2002. Close, stable homolog juxtaposition during meiosis in budding yeast is dependent on meiotic recombination, occurs independently of synapsis, and is distinct from DSB-independent pairing contacts. Genes Dev. 16: 1682–1695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pryde, F. E., and E. J. Louis, 1997. Saccharomyces cerevisiae telomeres: a review. Biochemistry 62: 1232–1241. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pryde, F. E., H. C. Gorham and E. J. Louis, 1997. Chromosome ends: all the same under their caps. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 7: 822–828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rockmill, B., and G. S. Roeder, 1998. Telomere-mediated chromosome pairing during meiosis in budding yeast. Genes Dev. 12: 2574–2586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherthan, H., 2001. A bouquet makes ends meet. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2: 621–627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selker, E. U., 1999. Gene silencing: repeats that count. Cell 97: 157–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storlazzi, A., S. Tesse, S. Gargano, F. James, N. Kleckner et al., 2003. Meiotic double-strand breaks at the interface of chromosome movement, chromosome remodeling, and reductional division. Genes Dev. 17: 2675–2687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taddei, A., and S. M. Gasser, 2004. Multiple pathways for telomere tethering: functional implications of subnuclear position for heterochromatin formation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1677: 120–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taddei, A., F. Hediger, F. R. Neumann, C. Bauer and S. M. Gasser, 2004. Separation of silencing from perinuclear anchoring functions in yeast Ku80, Sir4 and Esc1 proteins. EMBO J. 23: 1301–1312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tesse, S., A. Storlazzi, N. Kleckner, S. Gargano and D. Zickler, 2003. Localization and roles of Ski8p protein in Sordaria meiosis and delineation of three mechanistically distinct steps of meiotic homolog juxtaposition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100: 12865–12870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trelles-Sticken, E., J. Loidl and H. Scherthan, 1999. Bouquet formation in budding yeast: initiation of recombination is not required for meiotic telomere clustering. J. Cell Sci. 112: 651–658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trelles-Sticken, E., M. E. Dresser and H. Scherthan, 2000. Meiotic telomere protein Ndj1p is required for meiosis-specific telomere distribution, bouquet formation and efficient homologue pairing. J. Cell Biol. 151: 95–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Virgin, J. B., and J. P. Bailey, 1998. The M26 hotspot of Schizosaccharomyces pombe stimulates meiotic ectopic recombination and chromosomal rearrangements. Genetics 149: 1191–1204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wach, A., A. Brachat, R. Pohlmann and P. Philippsen, 1994. New heterologous modules for classical or PCR-based gene disruptions in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 10: 1793–1808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiner, B. M., and N. Kleckner, 1994. Chromosome pairing via multiple interstitial interactions before and during meiosis in yeast. Cell 77: 977–991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, T. C., and M. Lichten, 1994. Meiosis-induced double-strand break sites determined by yeast chromatin structure. Science 263: 515–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, T. C., and M. Lichten, 1995. Factors that affect the location and frequency of meiosis-induced double-strand breaks in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 140: 55–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]