Abstract

This article reports the cloning and characterization of the gene homologous to Sex-lethal (Sxl) of Drosophila melanogaster from Sciara coprophila, Rhynchosciara americana, and Trichosia pubescens. This gene plays the key role in controlling sex determination and dosage compensation in D. melanogaster. The Sxl gene of the three species studied produces a single transcript encoding a single protein in both males and females. Comparison of the Sxl proteins of these Nematocera insects with those of the Brachycera showed their two RNA-binding domains (RBD) to be highly conserved, whereas significant variation was observed in both the N- and C-terminal domains. The great majority of nucleotide changes in the RBDs were synonymous, indicating that purifying selection is acting on them. In both sexes of the three Nematocera insects, the Sxl protein colocalized with transcription-active regions dependent on RNA polymerase II but not on RNA polymerase I. Together, these results indicate that Sxl does not appear to play a discriminatory role in the control of sex determination and dosage compensation in nematocerans. Thus, in the phylogenetic lineage that gave rise to the drosophilids, evolution coopted for the Sxl gene, modified it, and converted it into the key gene controlling sex determination and dosage compensation. At the same time, however, certain properties of the recruited ancestral Sxl gene were beneficial, and these are maintained in the evolved Sxl gene, allowing it to exert its sex-determining and dose compensation functions in Drosophila.

IN Drosophila melanogaster, the gene Sex-lethal (Sxl) controls the processes of sex determination, sexual behavior, and dosage compensation (the products of the X-linked genes are present in equal amounts in males and females; reviewed in Penalva and Sánchez 2003). Sxl regulates the expression of two independent sets of genes (Lucchesi and Skripsky 1981): the sex determination genes (mutations in which affect sex determination but have no effect on dosage compensation) and the male-specific lethal genes (msls; mutations in which affect dosage compensation but have no effect on sex determination).

Sxl produces two temporally distinct sets of transcripts corresponding to the function of the female-specific early and non-sex-specific late promoters, respectively (Salz et al. 1989). The early set is produced as a response to the X/A signal, which controls Sxl expression at the transcriptional level (Torres and Sánchez 1991; Keyes et al. 1992). Once the state of activity of Sxl is determined—an event that occurs at the blastoderm stage—the X/A signal is no longer needed and the gene's activity is fixed (Sánchez and Nöthiger 1983; Bachiller and Sánchez 1991).

Three male-specific and three-female specific transcripts form the late set of Sxl transcripts, which appear slightly after the blastoderm stage and persist throughout development. The male transcripts are similar to their female counterparts, except for the presence of an additional exon (exon 3), which contains a translation stop codon. Consequently, male late transcripts give rise to presumably inactive truncated proteins. In females, this exon is spliced out and functional Sxl protein is produced (Bell et al. 1988; Bopp et al. 1991). Therefore, the control of Sxl expression throughout development occurs by sex-specific splicing of its primary transcript. The ability of Sxl to function as a stable switch is due to the positive autoregulatory function of its own product (Cline 1984), which is required for the female-specific splicing of Sxl pre-mRNA (Bell et al. 1991).

The gene Sxl encodes an RNA-binding protein that regulates its own RNA splicing (Sakamoto et al. 1992; Horabin and Schedl 1993). The Sxl protein controls sex determination and sexual behavior by inducing the use of a female-specific 3′ splice site in the first intron of the transformer (tra) pre-mRNA. Use of the alternative, non-sex-specific 3′ splice site results in a transcript that encodes a nonfunctional truncated protein, while use of the female-specific site allows the synthesis of full-length functional Tra polypeptide (Boggs et al. 1987; Sosnowski et al. 1989; Hoshijima et al. 1991; Valcárcel et al. 1993).

Sxl is also required for oogenesis (reviewed in Oliver 2002). 2X; 2A germ cells lacking Sxl protein do not enter oogenesis but follow an abortive spermatogenesis pathway characterized by the formation of multicellular cysts (Schüpbach 1985; Nöthiger et al. 1989; Steinmann-Zwicky et al. 1989). The onset of Sxl expression occurs later in germ cells than in somatic cells. By the time this gene is activated in the somatic cells (around the blastoderm stage), the pole cells (the precursors of the germ cells) still do not express Sxl (Bopp et al. 1991). Expression of this gene in germ cells is first detected in 16- to 20-hr-old embryos (Horabin et al. 1995). A female germ-line-specific Sxl transcript has been identified (Salz et al. 1989).

In Drosophila, dosage compensation takes place in males by hypertranscription of the single X chromosome and is mediated essentially by a group of genes known as male-specific lethals [msl 1, 2, 3, and maleless (mle)]. Three additional genes are involved in dosage compensation: mof, roX1, and roX2. The products of all these genes form a heteromultimeric complex, known as Msl, which associates preferentially with many sites on the male X chromosome. This chromosome acquires a chromatin structure, reflected by its pale bloated appearance, that allows hypertranscription of the genes located on it (reviewed in Akhtar 2003; Andersen and Panning 2003). The msl, mof, and roX genes are transcribed in both males and females. However, a stable Msl complex is formed only if the products of all these genes are present. This occurs exclusively in males, since only males express Msl-2 protein. In females, the production of this protein is prevented by the Sxl protein, which is exclusively expressed in this sex. In fact, ectopic expression of msl-2 in females is sufficient to assemble the Msl complex (Bashaw and Baker 1997; Kelley et al. 1995, 1997).

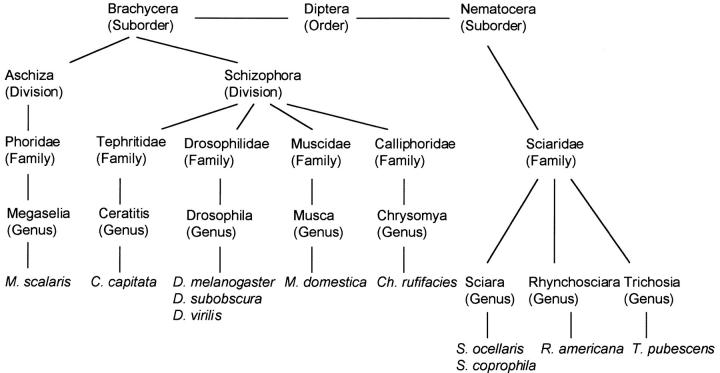

The order Diptera is composed of two suborders: Brachycera and Nematocera. Outside the genus Drosophila (suborder Brachycera), Sxl has also been characterized in insects of the suborder Brachycera: Chrysomya rufifacies (Müller-Holtkamp 1995), Megaselia scalaris (Sievert et al. 1997, 2000), Musca domestica (Meise et al. 1998), and Ceratitis capitata (Saccone et al. 1998) (see Figure 1). In none of these species does Sxl show sex-specific regulation, and the same Sxl protein is found in males and females. It is worth mentioning that sex determination in these species is regulated differently than that in Drosophila. In Megaselia, Musca, and Ceratitis, gender does not depend on chromosome constitution (i.e., the number of X chromosomes and autosomes) but on the presence of a male-determining factor in the Y chromosome (although in Musca it may be located on a single autosome). In Chrysomya, the sexual development of the zygote depends on the genotype of the mother, owing to a maternal factor deposited in the oocyte. Dosage compensation has not been reported in these species.

Figure 1.—

Phylogenetic relationships of the dipterans whose Sxl genes have already been characterized.

The gene Sxl has been also isolated and characterized in the sciarid Sciara ocellaris, which belongs to the Nematocera suborder. As in D. melanogaster, S. ocellaris (order Diptera, suborder Nematocera) gender depends on chromosome constitution: females are XX and males are XO (reviewed in Gerbi 1986). Dosage compensation in S. ocellaris also appears to be achieved by hypertranscription of the single male X chromosome (da Cunha et al. 1994). The cloning and characterization of the Sxl gene of S. ocellaris indicated that this gene appears not to play the key discriminative role in controlling sex determination and dosage compensation that it plays in Drosophila (Ruiz et al. 2003).

Thus, the gene Sxl has been cloned and characterized in dipteran insects belonging to different families of the suborder Brachycera and in the dipteran S. ocellaris, a member of the suborder Nematocera. To better understand the evolution of gene Sxl we undertook its cloning and characterization in other insects of the suborder Nematocera—S. coprophila, Rhynchosciara americana, and Trichosia pubescens—which represent three different genera of the Sciaridae (see Figure 1). In these species, gender also depends on chromosome constitution, as in D. melanogaster: females are XX and males are XO. Dosage compensation in Rhynchosciara also appears to be achieved by hypertranscription of the single male X chromosome (Casartelli and Santos 1969). Although dosage compensation has not been directly demonstrated in Trichosia, its sex determination mechanism (based on chromosome differences as in Sciara and Rhynchosciara) argues in favor of the existence of dosage compensation by hypertranscription of the sex chromosome in males.

The comparative analysis of Sxl from insects that belong to the suborders Brachycera and Nematocera indicates that Sxl was coopted and modified in the phylogenetic lineage that gave rise to the drosophilids to become the key element in controlling sex determination and dosage compensation in these insects.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Fly culture:

S. coprophila was raised in the laboratory at 18° following the procedure of Perondini and Dessen (1985). Since no established laboratory cultures of R. americana and T. pubescens were available, larvae, pupae, and adults were collected in the banana plantations of Mongaguá, Sao Paulo, Brazil.

Construction of a genomic library from S. coprophila:

This was performed using the λ DASH II/EcoRI vector kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA), following the manufacturer's instructions. The R. americana and T. pubescens genomic libraries used were synthesized by da Silveira (2000) and Penalva et al. (1997).

Cloning of the gene Sxl of S. coprophila, R. americana, and T. pubescens:

The S. coprophila, R. americana, and T. pubescens genomic libraries were screened with full-length S. ocellaris Sxl cDNA (Ruiz et al. 2003). The hybridization conditions were 42° for 18–20 hr in 5× SSC, 0.1% SDS, 25% formamide, 1× Denhardt, and 0.1 mg/ml of denatured salmon sperm DNA. Washes were repeated three times (20 min each) at 50° in 0.5× SSC and 0.1% SDS. The identification of positive clones, plaque purification, the preparation of phage DNA, Southern blot analysis, the identification of cross-hybridization fragments, the subcloning of the restriction fragments into plasmid pBluescript KS−, and the isolation of plasmid DNA were performed using the protocols described by Maniatis et al. (1982).

Transcript analyses:

Total RNA extracts from frozen adult males and females were prepared using the Ultraspec-II RNA isolation kit (Biotecx, Houston, TX), following the manufacturer's instructions. Poly(A)+ RNA was prepared using the mRNA purification kit (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech), also following the accompanying instructions for use. Electrophoretic fractionation of total RNA and blotting on nylon membranes were performed as described by Maniatis et al. (1982) and Campuzano et al. (1986). S. coprophila blots were hybridized with a probe containing the RBD domains of the S. ocellaris Sxl gene. R. americana and T. pubescens blots were hybridized with a PCR fragment spanning exons 3–7 of Sxl cDNA from R. americana. The hybridization conditions were those described by Ruiz et al. (2000), except that 19% formamide was used.

RT-PCR analyses:

Ten micrograms of total RNA from S. coprophila, R. americana, and T. pubescens larvae and adults (males and females separately), previously digested with RQ1 RNase-free DNase (Promega, Madison, WI), were reverse transcribed with AMV reverse transcriptase (Promega). Twenty percent of the synthesized cDNA was amplified by PCR. RT-PCR products were analyzed by electrophoresis in agarose gels, and the amplified fragments were subcloned using the TOPO TA-cloning kit (Invitrogen, San Diego) following the manufacturer's instructions. These were then sequenced using the universal forward and reverse primers.

DNA sequencing:

DNA genomic fragments and amplified cDNA fragments from RT-PCR analyses were sequenced using an automatic 377 DNA sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The accession numbers for the ORFs and protein sequences are: AY538250 for S. coprophila, AY538251 for R. americana, and AY538252 for T. pubescens. For S. coprophila the primers used to sequence the genomic region containing the whole ORF were: S1, 5′-ATAATCTATCCAGTATATGC-3′; S2, 5′-TAATTGTTAACTATTTACCG-3′; S3, 5′-TAATAACTATTGTATACCGC-3′; S4, 5′-GCCCTAATGACCGAATGTAC-3′; S5, 5′-CTTTAATGTTGACTTAGCGC-3′; S6, 5′-AGAGTTGTCACACATACCGC-3′; S7, 5′-GGCCCACAGATCTGCATAGG-3′; S9, 5′-ATCCTTCGTGATAATTGTGC-3′; S10, 5′-GACTTGAATTTTACATAAGC-3′; S11, 5′-GTAATGGCATAAACCTTTCG-3′; S12, 5′-AATGTTTGATGTTGCGTGCG-3′; S13, 5′-TGTTGTCACTAGTCACTAGC-3′; S14, 5′-AACGTGTTACACACGGCAGG-3′; S15, 5′-GGCCGAAGAGCATGGCAAGC-3′; and S16, 5′-CAAGTTTCACCTGACGCAGC-3′. For R. americana, the primers used to sequence the genomic region containing the whole ORF were: R1, 5′-ACGCAGGTGAGAAAATAGTC-3′; R2, 5′-CTTACTGTGTAACAAATGGC-3′; R3, 5′-TGTTGGGAGACACTTCGCAC-3′; R4, 5′-TTCGATGCACTATCCACCGC-3′; R5, 5′-AATCGGAATCTTGCTCTACC-3′; R6, 5′-TTGTGATTACTCTACGCGCG-3′; R7, 5′-ACGTCTAACACGATATCAGG-3′; R8, 5′-ACAACGCATTGTCTCAAGGC-3′; R9, 5′-CTCTAAGCTCAACTAGTTGG-3′; R10, 5′-CTCTGTTGTTTAAGATGGATC-3′; R11, 5′-GTAACATTAATATCGGCAGC-3′; R12, 5′-GGTGAGACCTGCACATAATG-3′; R13, 5′-GCCAGTTAGTGAACTAGTGC-3′; R14, 5′-TACCAGGACACAGATTTCTC-3′; R15, 5′-TTACTTTAATCCGTTTATTGCG-3′; R16, 5′-CTCGAGTTTCATTTGCTCGG-3′; R17, 5′-TCGTCTCAATATGGACTTATG-3′; R18, 5′-GGATCCGATAATTTGAAGTG-3′; R19, 5′-GCGAGTATGCTCCACACGC-3′; R20, 5′-CGTACAGTGCATGCAGGAAC-3′; R21, 5′-CCTGATATGGCTCCGTGCG-3′; and R22, 5′-ATGTACAACAAGAATGGCTATCC-3′. For T. pubescens, the primers used to sequence the genomic region containing the whole ORF were: T1, 5′-TCCTGAGTCAAATTTCTCCC-3′; T1.5, 5′-TATTAAGACGCTTCATGGCG-3′; T2, 5′-AAGTAGGTCTCCATAGTAG-3′; T3, 5′-CGACCGTTGAAAGTCTTTCG-3′; T4, 5′-CTTTCCGCATTATTTGCGTA-3′; T5, 5′-ATACAACAAGCGAGAGGAAG-3′; T6, 5′-TACGCAAATAATGCGGAAAG-3′; T7, 5′-CTGATTAGGTTTACAGCTTC-3′; T8, 5′-AATCCAGCCGAATCATGAGG-3′; T9, 5′-CGATTGCCAACTCCGGGACG-3′; T10, 5′-GCACATTGGCCATTGATCAAAG-3′; T11, 5′-CTTTGATCAATGGCCAATGTGC-3′; T12, 5′-CATAAGTCCATATTGAGACG-3′; and CORHY, 5′-ATGTACAATAAGAATGGGTATCC-3′.

Western blots:

Samples of total proteins from adult S. coprophila, R. americana, and T. pubescens males were prepared by homogenization in RIPA lysis buffer (150 mm NaCl, 1% NP-40, 0.5% DOC, 0.1% SDS, 50 mm Tris, pH 7.5) or NP-40 lysis buffer (150 mm NaCl, 1% NP-40, 50 mm Tris, pH 8.0) with 2 mm PMSF, 1 μm IAA, and 100 μg/ml of leupeptin, pepstatin, aprotinin and benzamidine. SDS-polyacrylamide gels (12%; Laemmli 1970) were blotted onto nitrocellulose (Towbin et al. 1979); blocked with 5% BSA, 10% nonfat dried milk, and 0.05% Tween-20 in PBS; and hybridized with anti-Sxl [1:5000; a polyclonal antibody against the S. ocellaris Sxl protein (Ruiz et al. 2003)] for 3 hr at room temperature. After washing in 0.05% Tween-20 in PBS (TPBS), filters were incubated with the secondary antibody [anti-rabbit IgG conjugated to alkaline phosphatase (1:3000) from Bio-Rad (Richmond, CA)] for 2 hr at room temperature. Filters were washed in TPBS and developed with the ECL Western blotting analysis kit (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech).

Immunostaining analysis of polytene chromosomes:

Salivary glands were dissected in Ringer's solution and transferred to a drop of fixative containing 5 μl acetic acid, 4 μl H2O, 1 μl 37% formaldehyde solution, and 1 μl 10% Triton X-100 in PBS. After squashing in the same fixative and freezing in liquid N2 to remove the coverslips, the slides were postfixed in 3.7% formaldehyde in PBS for 10 min at room temperature. After fixation, they were washed in PBS (3 times for 5 min) and then in PBS containing 1% Triton-X and 0.5% acetic acid for 10 min. They were then incubated with 2% BSA for 1 hr at room temperature. Primary anti-Sxl antibody (1:10) was incubated at 4° overnight. After washing in PBS (3 times for 5 min) they were incubated with a secondary Cy3-conjugated anti-rabbit antibody (1:500) at 4° for at least 4 hr. DNA was visualized with DAPI staining (0.1 μg/ml) and preparations were mounted in anti-fading solution. Observations were made under epifluorescence conditions using a Zeiss axiophot microscope equipped with a Photometrics CCD camera.

Immunostaining analysis of embryos:

Embryos at different developmental stages were collected, processed, and immunostained with anti-Sxl serum against the S. ocellaris Sxl protein as described by Ruiz et al. (2003).

Nucleotide substitution numbers and phylogenetic analyses:

Multiple alignments of nucleotide and amino acid sequences were conducted using Clustal X software (Thompson et al. 1997), employing the default parameters of the program. The alignment of the nucleotide sequences was constructed on the basis of the amino acid sequence. Further alignments with different gap penalizations were performed to estimate the stability and validity of the final alignments.

The proportions of synonymous (pS) and nonsynonymous (pN) differences per site were calculated by the modified Nei-Gojobori method (Zhang et al. 1998). In addition, the extent of overall nucleotide sequence divergence was estimated by means of the Kimura two-parameter model (Kimura 1980). Phylogenetic trees were reconstructed from these distances using the minimum evolution (ME) method (Rzhetsky and Nei 1992). The reliability of the inferred topologies was examined by the bootstrap method (Felsenstein 1985) and by the interior branch test (Rzhetsky and Nei 1992) to provide the bootstrap probability (BP) and confidence probability (CP), respectively. Values of BP = 95% and CP = 95% were assumed to be significant, but since bootstrap is known to be conservative, a BP > 80% was interpreted as significant support for the interior branches. Phylogenetic and molecular evolutionary analyses were conducted using the MEGA program (version 2.1; Kumar et al. 2001). The Sxl gene from the phorid M. scalaris was used to root the trees.

The amount of codon bias shown by the Sxl genes in the analyzed species was estimated using the DnaSP 4 program (Rozas et al. 2003). Codon bias is referred to as the “effective number of codons” (ENC; Wright 1990): the highest value (61) indicates that all synonymous codons are equally used (no bias), while the lowest (20) shows that only one codon is used.

Comparison of DNA and protein sequences:

This was performed using the Fasta program (version 3.0t82; Pearson and Lipman 1988).

RESULTS

The gene Sxl of S. ocellaris, R. americana, and T. pubescens:

The S. coprophila, R. americana, and T. pubescens genomic libraries were screened with full-length S. ocellaris Sxl cDNA (Ruiz et al. 2003). A positive phage was isolated for each library, and a PCR fragment was obtained from each using degenerated primers corresponding to one of the well-conserved RNA-binding domains (RBD) that characterize the Sxl proteins. The PCR fragments were subcloned and subsequently sequenced and corresponded to the predicted protein fragment of one of the Sxl protein RBDs. From these we proceeded to sequence in the 5′ and 3′ directions through overlapping sequencing to determine the sequence containing the entire ORF of the Sxl gene for each species (the primers used are specified in materials and methods, under DNA sequencing). A total of 9631 bp were sequenced for S. coprophila, 9550 bp for R. americana, and 5684 bp for T. pubescens. Comparison of these genomic sequences with that of the S. ocellaris Sxl gene suggested that, for S. coprophila and R. americana, the phage appeared to contain the whole ORF of the Sxl gene. For T. pubescens, however, the region corresponding to the 5′ end was missing (see below). No genomic phages of T. pubescens containing the 5′ end of the Sxl gene could be obtained, probably because that part of the genome was not represented in the library. A PCR strategy was therefore adopted, which consisted of amplifying a fragment from the genomic DNA of T. pubescens. One primer corresponded to the beginning of the Sxl-ORF of S. ocellaris, S. coprophila, and R. americana and the other to the beginning of the Sxl sequence of T. pubescens in the isolated genomic phage. This PCR fragment of ∼1 kb was subcloned and sequenced. Therefore, we were in possession of the entire genomic sequence of the ORF of gene Sxl belonging to T. pubescens.

A cDNA library of R. americana was screened using a PCR fragment containing the Sxl-RBDs of this species as a probe. Four phages were isolated that corresponded to the same partial cDNA. Repeated screenings of the cDNA library failed to provide a full Sxl-cDNA. Owing to this failure, and because of the lack of cDNA libraries of S. coprophila and T. pubescens, the following procedure was undertaken to characterize the ORF of Sxl in each species. First, to determine the putative ORF encoded by the genomic sequence of each species, a theoretical analysis of the more frequent splicing sites of these sequences was performed. Each sequence was then subjected to different putative splicing site pathways. Each spliced product was translated and compared to the Sxl protein of S. ocellaris to find the largest ORF for each species homologous to the Sxl protein of S. ocellaris. Second, to ascertain the molecular organization of Sxl in each species, overlapping RT-PCR fragments spanning the largest ORF were synthesized from male and female adult total RNA. These were subsequently cloned and sequenced.

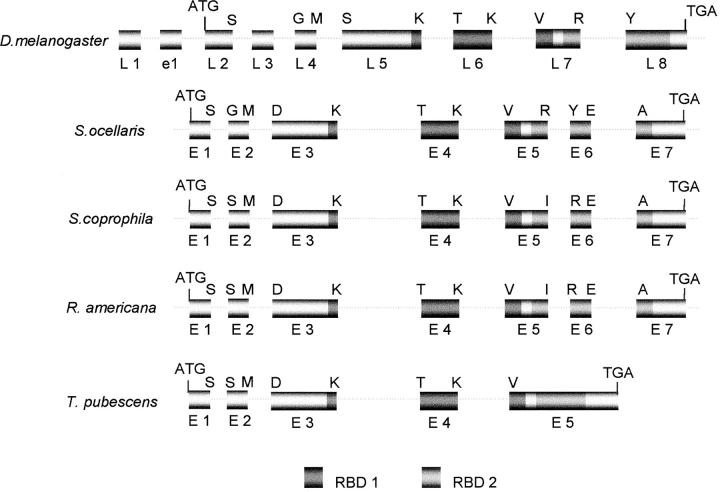

The molecular organization of the D. melanogaster Sxl gene is characterized because it has two promoters, the so-called early and late promoters, which produce two separate sets of early and late transcripts. In females, the early promoter is activated around blastoderm stage by the X/A signal, which controls Sxl at the transcriptional level. The late Sxl promoter is activated in both sexes after the blastoderm stage, and the production of the late transcripts persists throughout the remainder of development and adult life. Nothing is known about the regulation of the late Sxl promoter (reviewed in Penalva and Sánchez 2003, and references therein). The first exons of the early and late Sxl transcripts are exons e1 and L1, respectively, shown in the D. melanogaster Sxl scheme in Figure 2. This figure shows also the molecular organization of Sxl in S. coprophila, R. americana, and T. pubescens, and compares it with that of S. ocellaris and D. melanogaster. There is an extraordinary degree of conservation in the molecular organization of gene Sxl in the species studied. All three are composed of seven exons and their splicing sites match exactly at the amino acid level. Gene Sxl of T. pubescens contains five exons; the first four are homologous to those of S. ocellaris, S. coprophila, and R. americana, but exon 5 corresponds to the fusion of exons E5, E6, and E7 of these species. Exons E1, E2, E3, and E4 of S. coprophila, R. americana, and T. pubescens are homologous to D. melanogaster exons L2, L4, L5, and L6, respectively. Exon 5 of S. coprophila and R. americana is homologous to exon L7 of D. melanogaster, which is also homologous to exon 5 of T. pubescens. Exon L8 of Drosophila corresponds to the fusion of exons E6 and E7 of S. coprophila and R. americana; its homolog in T. pubescens lies within exon E5. No sequences in the gene Sxl of S. coprophila, R. americana, and T. pubescens were homologous to the male-specific L3 exon of the D. melanogaster Sxl gene. Neither were any sequences homologous to the first exon e1 of the early D. melanogaster Sxl transcripts or to the first exon L1 of the late Sxl transcripts, found in the gene Sxl of S. coprophila or R. americana (the point up to which sequences upstream of the 5′ end of the ORF were available; data not shown).

Figure 2.—

The molecular organization of the S. coprophila, R. americana, and T. pubescens Sxl genes and comparison with Sxl of D. melanogaster and S. ocellaris. L and E stand for D. melanogaster and the sciarid Sxl exons (boxes), respectively, and e1 stands for the first exon found only in the early D. melanogaster Sxl transcripts. The dotted lines represent introns. They are not drawn to scale. The uppercase letters on the top of each gene represent the amino acids corresponding to the exon/intron junctions. The beginning and the end of the ORF are indicated by ATG and TGA respectively. RBD1 and RBD2 symbolize the RNA-binding domains.

Transcript analysis of the S. coprophila, R. americana, and T. pubescens Sxl gene and its expression pattern:

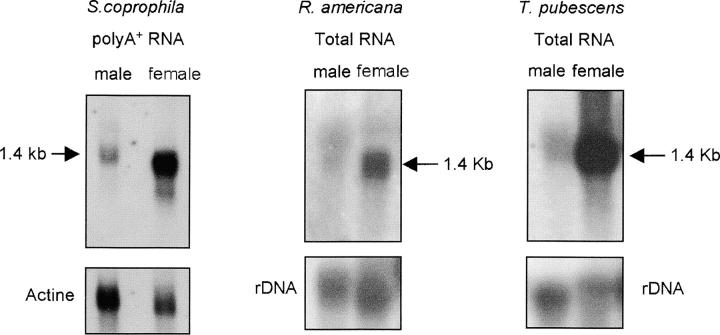

The Sxl gene of D. melanogaster basically produces three transcripts in adult females (4.2, 3.3, and 1.9 kb) and three transcripts in adult males (4.4, 3.6, and 2.0 kb). Another transcript of 3.3 kb is expressed in the female germ line (Bell et al. 1988; Salz et al. 1989). Different Sxl-spliced variants have been also reported in D. subobscura (Penalva et al. 1996), D. virilis (Bopp et al. 1996), Ch. rufifacies (Müller-Holtkamp 1995), M. domestica (Meise et al. 1998), C. capitata (Saccone et al. 1998), and M. scalaris (Sievert et al. 2000). To characterize the transcripts from the Sxl gene of the sciarids, Northern blots of either poly(A)+ RNA (S. coprophila) or total RNA (R. americana and T. pubescens) from both male and female adults were performed and subsequently hybridized with a cDNA fragment encompassing the two RBDs (see Figure 3 legend). A single Sxl transcript of ∼1.4 kb is present in both male and female adults (Figure 3). In male and female larvae the same transcript was also present in similar amounts to those found in adult males (data not shown). The quantity of Sxl RNA was higher in female adults than in male adults. This cannot be attributed to a higher content of poly(A)+ or total RNA loaded in the female lanes; this is indicated by the hybridization signal of the actin (S. coprophila) or the rDNA (R. americana and T. pubescens) used as a loading control. Thus, it appears that gene Sxl in S. coprophila, R. americana, and T. pubescens has a high maternal expression. These results suggest that it produces a single transcript in both sexes, as in S. ocellaris (Ruiz et al. 2003). This is different, however, from the Sxl spliced variants found in the other species in which Sxl has been characterized. To detect minor differences in the size of putatively different Sxl transcripts in males and females, overlapping RT-PCRs were performed in the three species (Figure 4). For details, see the Figure 4 legend.

Figure 3.—

Northern blots of poly(A)+ RNA from males and females of S. coprophila probed with the cDNA fragment encompassing the two RBDs of S. ocellaris Sxl cDNA, and Northern blots of total RNA from males and females of R. americana and T. pubescens probed with the cDNA fragment encompassing the two RBD domains of R. americna Sxl cDNA. Hybridization with the actin RNA probe (Fyrberg et al. 1981) for S. coprophila, or the D. melanogaster rDNA probe (pDm238; Roiha et al. 1981) for R. americana and T. pubescens, was used as a loading control for poly(A)+ or total RNA, respectively.

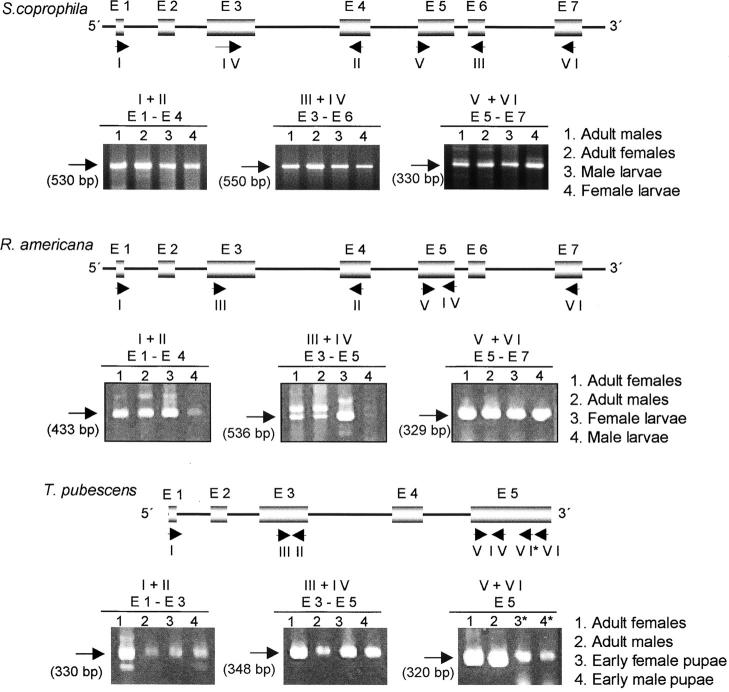

Figure 4.—

Sxl transcription at different developmental stages. The molecular organization of each Sxl gene is provided at the top, showing the products of the RT-PCR reactions. Boxes represent exons (indicated by E), thin lines represent introns, and the locations of the primers are shown by short arrows and identified by Roman numerals. The predicted size of the amplified Sxl fragments is indicated in parentheses under the long arrows. The RT-PCR products were subcloned and sequenced (four subclones for each RT-PCR product were analyzed). The sequence revealed that in those cases where two RT-PCR fragments were produced, only one corresponded to gene Sxl (indicated by the long arrow); the second was nonspecific.

With respect to S. coprophila, the existence of a single transcript corresponding to the largest ORF found in the theoretical analysis was confirmed.

With respect to R. americana, the transcript corresponding to the largest ORF in the theoretical analysis of the more frequent splicing sites was found, as well as another transcript that also carried the sequence encoding the stretch of amino acids SQYAYQ, corresponding to the sequence at the splice junction of exons L4/L5 in Drosophila, Ceratitis, Musca, Megaselia, and Chrysomya Sxl transcripts. Of the 48 RT-PCR subclones analyzed, only one was found to lack the sequence corresponding to exon 2 and the first 63 bp of exon 3. The conceptual translation of this transcript would yield a protein lacking 42 amino acids at the N-terminal domain of the full-length Sxl protein, which corresponds to the 1.4-kb transcript. If such a small transcript is not the product of an abnormal RT-PCR reaction, it must correspond to a transcript that is not very abundant.

With respect to T. pubescens, the existence of a single transcript was confirmed, corresponding to the largest ORF found in the theoretical analysis of the more common splicing sites. This transcript also contained the sequence encoding the stretch of amino acids SQYAYQ found in R. americana. The overlapping RT-PCR analyses showed that Sxl is expressed during development in S. coprophila, R. americana, and T. pubescens.

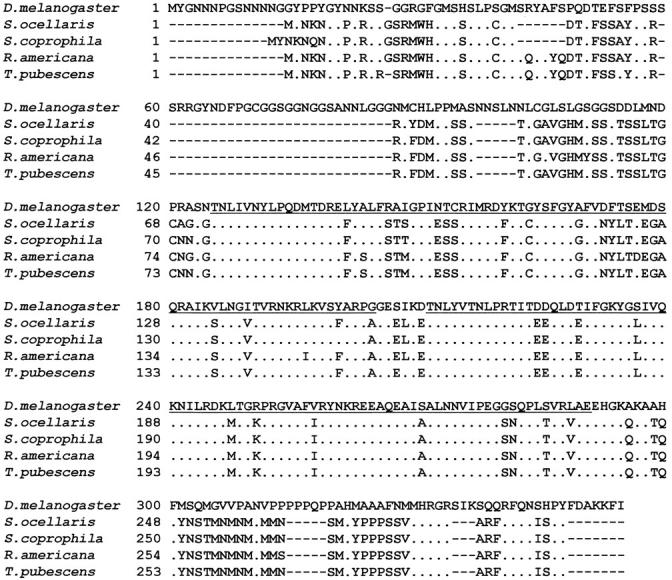

The Sxl proteins of S. coprophila, R. americana, and T. pubescens and their comparison with other Sxl proteins:

The biggest Sxl-ORF found in S. coprophila, R. americana, and T. pubescens encoded Sxl proteins of 289, 293, and 293 amino acids, respectively, all of which showed a high degree of homology to other characterized Sxl proteins. The number of amino acids varies among the Sxl proteins of the Brachycera species—to which D. melanogaster belongs—whereas in the Nematocera species the number was very conserved. To better compare the degree of conservation between these Sxl proteins and to analyze the distribution of the conservative changes, the proteins were divided into three regions: the N-terminal region, the RBDs, and the C-terminal region (Figure 5). The Sxl protein of D. melanogaster was used as reference. The Sxl proteins of the species belonging to the suborder Nematocera were very conserved at the N- and C-terminal domains and in their RBDs. The Sxl proteins of the species that belong to the suborder Brachycera were very conserved in the RBDs, but variations were seen in their N- and C-terminal domains. The highest degree of conservation among all the Sxl proteins was seen for the RBDs, not only with respect to the number of amino acids but also in terms of the types of amino acids making up these domains. Neither insertion nor deletion of residues was detected in comparisons among different species. By classifying the amino acid residues in regard to their lateral (R) chains as polar, nonpolar, acid, and basic, it was found that polar and nonpolar residues represent almost 75% of the whole RBDs (38.77 and 35.7%, respectively), where the great majority of the amino acid replacements involved residues belonging to the same functional group, maintaining the chemical properties of these protein segments.

Figure 5.—

Alignment of S. coprophila, R. americana, and T. pubescens Sxl proteins with the Sxl protein of S. ocellaris and of D. melanogaster, used here for reference. The RNA-binding domains RBD1 and RBD2 are underlined. Dots indicate the matching of amino acids. Gaps were introduced in the alignments to maximize similarity.

Association of the Sxl protein with polytene chromosomes in S. coprophila, R. americana, and T. pubescens:

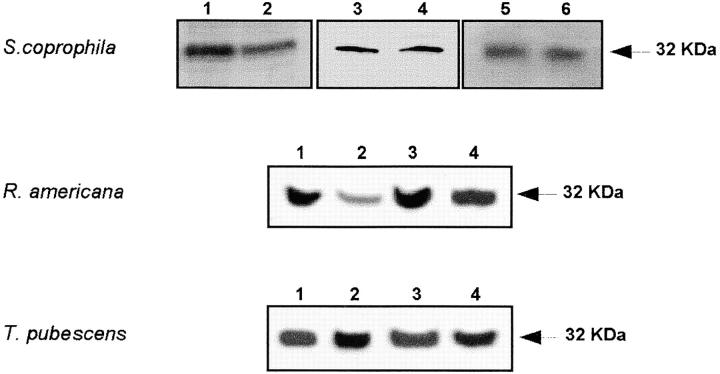

Due to the strong conservation of the Sxl proteins in the species of the suborder Nematocera, it was expected that the antibody to the Sxl protein of S. ocellaris might recognize those of the other three species. This was tested by performing Western blots of total protein extracts from S. coprophila, R. americana, and T. pubescens probed with the anti-Sxl antibody. The antibody indeed detected a protein of ∼32 kD in the males and females of the three species (Figure 6), which corresponds to the size of the Sxl protein predicted from transcript analysis (see above).

Figure 6.—

Western blots of total protein extracts from S. coprophila, R. Americana, and T. pubescens. The anti-Sxl against the S. ocellaris Sxl protein was used (Ruiz et al. 2003). The preimmune serum does not give any signal in Western blots (data not shown). For S. coprophila: lane 1, female post-blastoderm embryos; lane 2, male post-blastoderm embryos; lane 3, salivary glands of female larvae, lane 4, salivary glands of male larvae; lane 5, head an thorax of adult females; and lane 6, head and thorax of adult males. The identification of sexual phenotype of embryos and larvae of S. coprophila is straightforward because this species is composed of female-producer (gynogenic) and male-producer (androgenic) females. In addition, the different size of the male and female gonads can be also used for sexing the larvae. For R. americana: lane 1, abdomen of adult females; lane 2, abdomen of adult males; lane 3, head and thorax of adult females; and lane 4, head and thorax of adult males. For T. pubescens: lane 1, abdomen of adult females; lane 2, abdomen of adult males; lane 3, head an thorax of adult females; and lane 4, head and thorax of adult males.

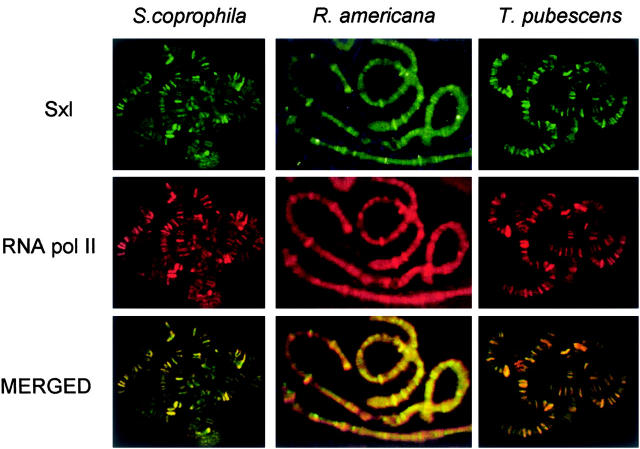

Immunofluorescence analysis of S. coprophila, R. americana, and T. pubescens polytene chromosomes showed the anti-Sxl antibody to associate with numerous regions of all the chromosomes (Figure 7). To investigate whether the chromosomal Sxl location was related to transcription-active regions, double immunofluorescence with anti-Sxl and anti-RNA polymerase II antibody was performed. The Sxl protein always colocalized with RNA polymerase II in all the chromosomes, except for a few regions that showed only the presence of RNA polymerase II. Sxl protein was not detected at chromosome regions bearing rDNA genes where RNA polymerase II is known to be absent. The same pattern was found in both sexes.

Figure 7.—

Distribution of Sxl protein and its colocalization with RNA polymerase II in S. coprophila, R. americana, and T. pubescens polytene chromosomes.

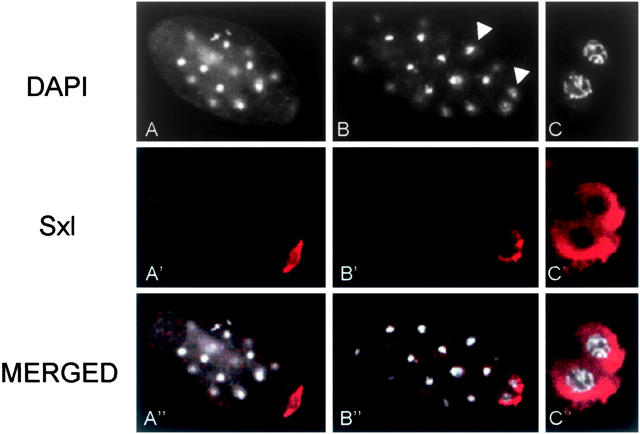

Distribution of the Sxl protein in S. coprophila embryos:

The male and female embryos of S. ocellaris showed maternal Sxl protein restricted to the polar region surrounding the germ-line nuclei (Ruiz et al. 2003). The distribution of the Sxl protein in S. coprophila embryos, whether male or female, was the same as for S. ocellaris (Figure 8). The same pattern was observed in nonfertilized eggs, indicating that the Sxl protein detected in the polar region of the embryo is of maternal origin and that no maternal Sxl protein associates with the somatic cells. Thus, the Sxl protein observed in postblastoderm embryos of both sexes was of zygotic origin (Figure 6, S. coprophila). Unfortunately, it was not easy to obtain Rhynchosciara and Trichosia embryos from their natural environments, so this analysis could be performed only on S. coprophila embryos.

Figure 8.—

Distribution of Sxl protein in preblastoderm stage embryos of S. coprophila. (A and B) DAPI staining and indirect immunolabeling with anti-Sxl antibody (in red) of a whole embryo showing the germ nuclei (arrow) and the somatic nuclei (arrowhead). (C) Partial view of germ nuclei surrounded by Sxl protein.

The phylogeny of gene Sxl in dipteran species:

The extent of the overall nucleotide sequence divergence in the gene Sxl among dipteran species was substantially higher than that of protein sequence divergence, where most of the nucleotide variation is synonymous. Consequently, most of the nucleotide variation is in the form of synonymous substitutions. On average, the synonymous divergence (0.562 ± 0.012 substitutions/site) was significantly greater than the magnitude of nonsynonymous variation (0.199 ± 0.013 substitutions/site; P < 0.001, Z-test). With respect to the different dipteran families, the nucleotide variation shown by the members of the Drosophilidae (pS = 0.338 ± 0.021; pN = 0.040 ± 0.007) was greater than that of the Sciaridae members (pS = 0.252 ± 0.019; pN = 0.015 ± 0.004). Although nucleotide substitution numbers reach high magnitudes in some cases, the effect of multiple substitutions has been minimized by correcting distances and by comparing total nucleotide substitution numbers with those obtained by estimating synonymous and nonsynonymous divergence.

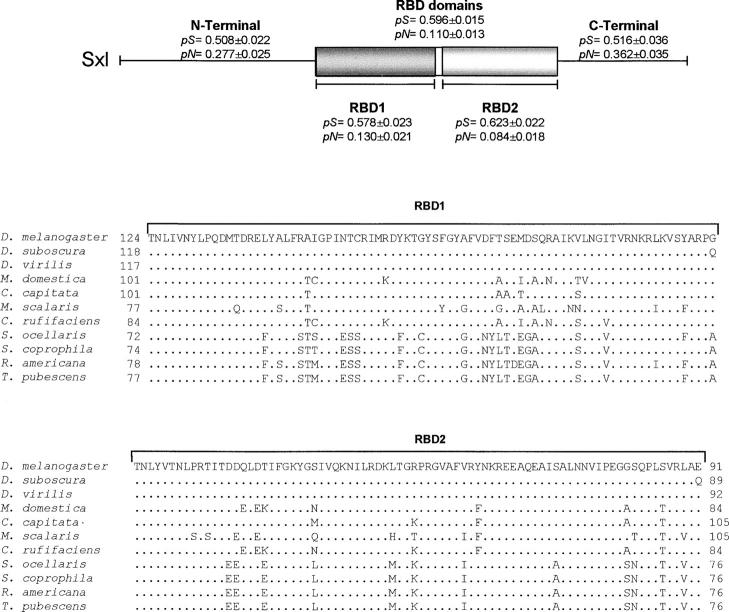

The Sxl protein shows a tripartite structure with a central conserved RBD composed by two segments (RBD1 and RBD2), flanked by two terminal arms (N- and C-terminal segments). The RBDs endow the Sxl protein with the capacity to bind to RNA, whereas the N-terminal domain is implicated in protein-protein interaction (Sxl multimerization; reviewed in Penalva and Sánchez 2003, and references therein). The analysis of the individual domains revealed a total absence of insertions and deletions (indel events) of nucleotides in the RBDs, supporting the conserved status of this RNA-binding region among species. In contrast, both the N- and C-terminal regions showed many indel events, generating gaps in the sequence alignments. By estimating the average proportions of nucleotide differences per site for each domain in all the species analyzed, it was found that, although highly conserved at the amino acid level, the RBDs showed a synonymous divergence (pS = 0.596 ± 0.015), which was significantly greater than the nonsynonymous divergence (pN = 0.110 ± 0.013; P < 0.001, Z-test; Figure 9). The same was observed when discriminating between RBD1 (pS = 0.578 ± 0.023, pN = 0.130 ± 0.021) and RBD2 (pS = 0.623 ± 0.022, pN = 0.084 ± 0.018). In both cases, pS was significantly greater than pN (P < 0.001, Z-test). The N- and C-terminal domains also showed pS values (0.508 ± 0.022 and 0.516 ± 0.036, respectively), which were again significantly greater when compared with the estimated pN values (0.277 ± 0.025 and 0.362 ± 0.035, respectively; P < 0.001, Z-test).

Figure 9.—

Comparison of all dipteran Sxl proteins characterized so far and nucleotide substitution numbers in the three domains in which the proteins were subdivided: N-terminal, RNA-binding domains (RBD1 and RBD2) and C-terminal domains. Amino acid alignments for the RBDs were performed using D. melanogaster Sxl protein as a reference. The dots indicate the matching of amino acids. The numbers on the left and right of the RBDs indicate the number of amino acids composing the N- and C-terminal domains, respectively. Synonymous (pS) and nonsynonymous (pN) substitution numbers are placed above the corresponding protein domains. The accession numbers for the Sxl ORFs are: AY178581 for S. ocellaris, M59448 for D. melanogaster, X98370 for D. subobscura, communicated by Paul Scheld's group for D. virilis, AF026145 for C. capitata, AF025690 for M. domestica, S79722 for Ch. rufifacies, and AJ245662 for M. scalaris.

Codon bias values were estimated for each species using the ENC index (Wright 1990) and showing Sxl to be a medium-low-biased gene (50.039 ± 4.242 as average). The tephritid C. capitata showed the lowest codon bias of the 11 species analyzed (56.756); in contrast, the four sciarid species showed the highest ENC values (from 42.322 for R. americana to 49.026 in T. pubecens). Discriminating among the three protein domains, the lowest ENC values were found in the RBDs (50.119 ± 5.549 as average). These results show an absence of strong selective constraints acting at the nucleotide level in this gene, which is otherwise mainly under a strong purifying selection at the amino acid level.

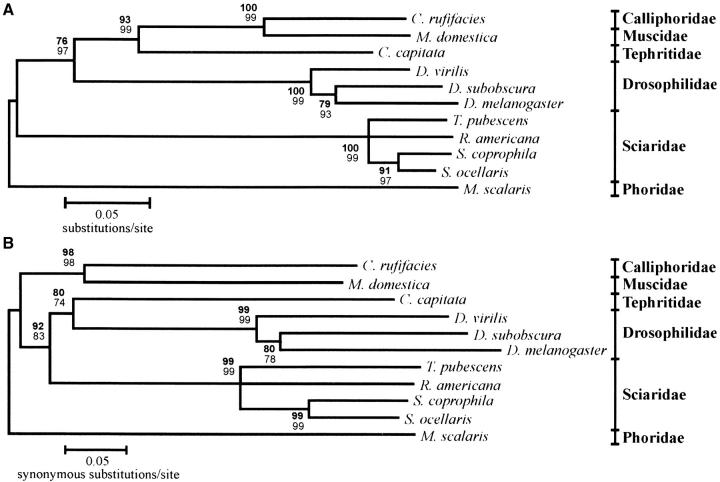

A phylogeny for the Sxl gene in dipteran species was reconstructed from complete nucleotide-coding regions belonging to all the species analyzed. A first phylogenetic tree was reconstructed from Kimura's two-parameter evolutionary distances (Figure 10A). Taking into account the high contribution of synonymous substitutions to the overall variation, an additional phylogeny was reconstructed from modified Nei-Gojobori pS evolutionary distances (Figure 10B). Both topologies showed the presence of high proportions of total and synonymous nucleotide substitutions, as revealed by the long branch lengths in the trees. Also in both cases, Sxl genes from species belonging to the families Calliphoridae and Muscidae share the more recent common ancestor, as in the case of species belonging to the genus Sciara and in the case of D. melanogaster and D. subobscura. Additionally, both topologies set ancestral points of divergence that differentiate the gene lineage that gives rise to the Sxl genes from sciarids. An important difference observed between the two topologies refers to the branching pattern involving Sxl genes from species belonging to the families Drosophilidae and Tephritidae. In the tree shown in Figure 10A, Sxl genes from both families are more closely related to Sxl genes belonging to the families Calliphoridae and Muscidae, sharing a common ancestor that is different from the more recent common ancestor shared by members of the family Sciaridae. This pattern matches perfectly the taxonomic relationships among the dipteran species analyzed, as shown in Figure 1. All the groups defined by the topology are strongly supported by significant bootstrap and interior branch-test values. The topology reconstructed from synonymous substitutions (Figure 10B) also showed significant values for both tests, but in this case Sxl genes from the families Drosophilidae and Tephritidae are more closely related to Sxl genes from sciarid species.

Figure 10.—

Phylogenetic relationships among Sxl genes from dipteran species. Bootstrap values (BP, boldface type) and interior branch test values (CP, regular type) are provided at the corresponding nodes. (A) Minimum-evolution tree reconstructed from complete nucleotide-coding sequences using Kimura's two-parameter distances; (B) the minimum-evolution tree reconstructed using modified Nei-Gojobori distances (pS). All nodes are significantly supported by BS and CP values in both phylogenies, except in the Sciaridae where the node was collapsed. Tree topologies gather together members of the same families and fit the taxonomic classification of these dipteran species.

DISCUSSION

This article reports the isolation and characterization of the gene Sxl of other Nematocera insects belonging to the genera Sciara, Rhychosciara, and Trichosia of the family Sciaridae. The results indicate that this gene produces a single protein in S. coprophila, R. americana, and T. pubescens, and that this is the same in males and females. Hence, Sxl does not appear to play the key discriminating role in controlling sex determination and dosage compensation in sciarids that it plays in Drosophila. This is so despite the fact that in the present sciarids—as in Drosophila—gender depends on chromosome constitution. Dosage compensation in Sciara (da Cunha et al. 1994) and Rynchosciara (Casartelli and Santos 1969) also appears to be achieved by hypertranscription of the single male X chromosome. Differences between D. melanogaster and the sciarids also exist with respect to the genes controlling dosage compensation: in S. ocellaris, analysis of the genes homologous to the dosage compensation genes mle, msl-1, msl-2, msl-3, and mof of Drosophila has shown that different proteins control dosage compensation in Drosophila and Sciara (Ruiz et al. 2000). Together, these results on the nature of Sxl in the Brachycera and Nematocera dipterans indicate that it was coopted during the evolution of the drosophilid lineage and modified to become the key regulatory gene controlling sex determination and dosage compensation.

For the Drosophila Sxl gene to exercise its function, it had to acquire sex-specific regulation so that only females could produce functional Sxl protein. Thus, the ancestral Sxl gene was modified in the Drosophila lineage to acquire a promoter that specifically responds to the X/A signal formed in females, a male-specific exon with translation stop codons that prevents formation of functional Sxl protein in males and a positive autoregulatory function that endows on Sxl the capacity to function as a stable switch (on the basis of the requirement of Sxl protein for female-specific splicing of its own primary transcript). In this respect, no sequences homologous to the male-specific exon of the Drosophila Sxl gene have been found in the Sxl of the other Brachycera and Nematocera species in which this gene has been characterized. In addition, the same Sxl protein is found during development and in adult life in males and females, indicating the absence of an early promoter of Sxl in non-drosophilid insects. It has been proposed that the X/A signal in Drosophila coevolved with its target, the early Sxl promoter (Saccone et al. 1998).

As mentioned above, sex determination in the sciarids depends on chromosome constitution: XXAA insects develop as females and XOAA insects as males. This is supported by the existence of gynandromorphs in Sciara (Mori and Perondini 1980). Thus, it may well be possible that an X/A signal exists in the sciarids, and that it is the primary genetic signal determining gender. The target gene of this signal is not Sxl but another gene that in the sciarids has the same function as Sxl in the drosophilids—the control of sex determination and dosage compensation. Nevertheless, it cannot yet be ruled out that these two processes do not share a common genetic control through an Sxl-like gene as in Drosophila. It is possible that sex determination depends on the absolute number of X chromosomes, where an X-linked gene(s) present in two doses causes female development and a single dose determines male development. In this scenario, a gene(s) other than that controlling sex determination would control dosage compensation.

The positive autoregulatory function of Drosophila Sxl is based on the capacity of Sxl protein to bind RNA: the Sxl protein requires its two domains for site-specific RNA binding (Wang and Bell 1994; Kanaar et al. 1995; Sakashita and Sakamoto 1996; Samuels et al. 1998). The characterization of Sxl protein in sciarids and its comparison with the Sxl proteins of the other dipteran species showed the RBDs to be highly conserved. This conservation is reflected in the exact number and the class of amino acids that compose these domains, which contrasts with the variable number and different amino acids of both the N- and C-terminal domains (Figure 9). This high degree of conservation at the amino acid level is not reflected at the nucleotide level, indicating that the great majority of nucleotide changes are synonymous (Figure 9), and that purifying selection is acting on the RBDs. These results support the contention that the RNA-binding capacity of the Drosophila Sxl protein was a property already present in the ancestral Sxl protein of the insects from which the dipterans evolved.

The Drosophila Sxl protein is abundant in the ovaries but is not detectable in unfertilized eggs (Bopp et al. 1993) even though these contain large amounts of Sxl mRNA (Salz et al. 1989). The blockage of the translation of these mRNAs is necessary. After the blastoderm stage, the late Sxl promoter starts functioning in both sexes and produces the late Sxl transcripts. The presence of maternal Sxl protein in male embryos demands that late Sxl RNA be processed by the female-specific splicing pathway, leading to the production of late Sxl proteins. The feedback loop is thus established. This causes male-specific lethality since the presence of Sxl protein prevents hypertranscription of the single X chromosome in males. In other words, dosage compensation does not occur.

In the Brachycera species Musca (Meise et al. 1998) and Ceratitis (Saccone et al. 1998), and in the sciarids S. ocellaris (Ruiz et al. 2003) and S. coprophila (data not shown), Sxl is also abundantly expressed in the ovaries. Its expression has also been reported in male and female embryos of these species. In Musca, Sxl protein first appears in blastoderm embryos in the somatic cells—but never in the pole cells, the precursors of the germ line (Meise et al. 1998). The same is seen in Drosophila (Bopp et al. 1991; Penalva et al. 1996). Hence, it appears that in Musca there is no Sxl protein of maternal origin. In Ceratitis, Sxl protein is already observed in syncytial blastoderm embryos and in the pole cells (Saccone et al. 1998). Whether this protein is of maternal origin or corresponds to the first transcription of the zygotic Sxl gene remains unknown. In S. ocellaris (Ruiz et al. 2003) and in S. coprophila (this article), maternal Sxl protein is seen in the embryo, but it is restricted to the cytoplasmic regions surrounding the germ-line nuclei; it is not seen in the somatic nuclei. Thus, in Brachycera and Nematocera species there is no maternal Sxl protein in the somatic cells of the early embryo. This suggests that the absence of maternal Sxl protein in Drosophila embryos, despite it being abundant in the oocytes, is a property inherited from the ancestral Sxl gene.

It has been proposed that outside the drosophilids, the primary or even exclusive function of Sxl is to modulate gene activity through inhibition of mRNA translation in both sexes (Saccone et al. 1998). This suggestion is based on the following observations. First, Sxl controls dosage compensation in Drosophila through the regulation of translation of the mRNA of gene msl-2 (Kelley et al. 1997). Second, Sxl protein accumulates at many transcriptionally active sites in the polytene chromosomes of females (Samuels et al. 1994). And third, ectopic expression of Ceratitis (Saccone et al. 1998) and Musca (Meise et al. 1998) Sxl protein in Drosophila is lethal in both sexes, presumably by interfering with certain cellular functions since Drosophila, Ceratitis, and Musca Sxl proteins have conserved RNA-binding domains.

In this work, the distribution of the Sxl protein in the sciarids S. ocellaris (Ruiz et al. 2003) and in S. coprophila, R. americana, and T. pubescens revealed Sxl is found in polytene chromosome regions of all actively transcribing chromosomes, and that it colocalizes with RNA polymerase II but not with RNA polymerase I. This was observed in both sexes. Further, comparison of the different Sxl proteins showed their two RNA-binding domains to be highly conserved. These results agree with the proposition that, in the non-drosophilids, Sxl works as an inhibitor of translation of mRNAs. However, the alternative, nonmutually exclusive possibility that Sxl is a general splicing factor cannot be ruled out since both functions are exerted through its two RNA-binding domains. Nevertheless, all the results point to the idea that the ancestral Sxl gene was involved in general non-sex-specific gene regulation at the splicing and/or translational levels. Therefore, during the phylogenetic lineage that gave rise to the drosophilids, evolution modified the coopted Sxl gene to convert it into a specific splicing factor and/or translation inhibitor for controlling sex determination and dosage compensation, profiting from certain properties of the recruited gene that are maintained in the evolved Drosophila Sxl gene.

With regard to the modifications that endow the Drosophila Sxl protein with its functional specificity, it has been shown that Sxl multimerization is essential for proper control of Sxl RNA alternative splicing (Wang and Bell 1994; Wang et al. 1997; Lallena et al. 2002). There is, however, some conflict concerning the elements required for protein-protein interaction and, consequently, the cooperative binding of Sxl. It has been claimed that the amino terminus of the Sxl protein is involved in protein-protein interactions (Wang and Bell 1994; Wang et al. 1997; Lallena et al. 2002). This domain, which is very rich in glycine, also mediates interactions with other RNA-binding proteins that contain glycine-rich regions (Wang et al. 1997). According to Samuels et al. (1994), protein-protein interaction is mediated by the RNA-binding domains and not by the amino-terminal region and can occur in the absence of additional, exogenous RNA. Sakashita and Sakamoto (1996) also reached the same conclusion on the importance of RNA-binding domains for Sxl-Sxl interaction, but unlike Samuels et al., and in agreement with Wang and Bell (1994), they indicate that homodimerization of Sxl is RNA dependent. There is also some controversy concerning the function of the N-terminal region of the Sxl protein in transformer RNA sex-specific splicing regulation. It has been proposed that this region is not necessary for tra pre-mRNA splicing regulation (Granadino et al. 1997)—but just the opposite has been proposed, too (Yanowitz et al. 1999). With respect to the control of dosage compensation by Sxl protein, the N-terminal domain is not required for preventing msl-2 expression (Gebauer et al. 1999; Yanowitz et al. 1999). The two Sxl RBDs by themselves are able to control in vitro msl-2 mRNA translation (Gebauer et al. 1999).

Neither Musca (Meise et al. 1998) nor Ceratitis (Saccone et al. 1998) Sxl proteins were capable of supplying the somatic Sxl function when expressed in Drosophila Sxl mutants, despite the very high degree of conservation of the two RNA-binding domains. Presumably this incapacity is due to changes in other regions of the Sxl proteins.

The same very high degree of conservation in the RBDs of the sciarid Sxl proteins was observed, whereas the N- and C-terminal domains showed significant variation (Figure 9). These results support the contention that the main modifications that render Drosophila Sxl protein its functional specificity are located in its terminal domains outside the well-conserved RNA-binding domains (Meise et al. 1998; Saccone et al. 1998).

The phylogenetic relationships among Sxl genes were reconstructed from the complete nucleotide-coding regions. They parallel the scheme shown in Figure 1 regarding the ancestral status of Sciaridae Sxl genes in comparison with those of the remaining dipteran species, while both Drosophila and Musca Sxl genes have more common ancestors than in the case of sciarid species. Differences in the branching pattern involving Sxl genes from species belonging to the families Drosophilidae and Tephritidae were observed between both trees. A possible explanation for this observation could involve: (a) the high proportions of synonymous differences per site observed in Sxl genes (although corrections for multiple hits have been used, some distances could be close to the saturation level, modifying the tree topology) and (b) high levels of pN between drosophilids/tephritids and sciarids (which are not considered in the topology shown in Figure 10B so that synonymous divergence could be lower in this case). Although the effect of multiple hits could not be completely ruled out, these would not modify the major conclusions of this work.

The great majority of the nucleotide changes detected in the RBDs among all the analyzed species are synonymous and significantly greater than the numbers of nonsynonymous substitutions (P < 0.001, Z-test). Additionally, low codon bias values were observed in these domains, suggesting a relaxation in the selective constraints acting at the nucleotide level. At the protein level, we found otherwise a total absence of indel events, and the great majority of the amino acid replacements involved residues belonging to the same functional group. These results evidence the presence of strong purifying selection acting at the protein level on RBDs, preserving the mechanism of action of all these Sxl proteins, further suggesting that the Sxl protein has a very important general function in these insects.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to D. Mateos for her technical assistance. This work was financed by grant PB98-0466 y BMC2002-02858 awarded to L.S. by Dirección General de Investigación Científica y Técnica.

References

- Akhtar, A., 2003. Dosage compensation: an interwined world of RNA and chromatin remodelling. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 13: 161–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen, A. A., and B. Panning, 2003. Epigenetic gene regulation by noncoding RNAs. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 15: 281–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachiller, D., and L. Sánchez, 1991. Production of XO clones in XX females of Drosophila. Genet. Res. 57: 23–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bashaw, G. J., and B. S. Baker, 1997. The regulation of the Drosophila msl-2 gene reveals a function for Sex-lethal in translational control. Cell 89: 789–798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell, L. R., E. M. Maine, P. Schedl and T. W. Cline, 1988. Sex-lethal, a Drosophila sex determination switch gene, exhibits sex-specific RNA splicing and sequence similar to RNA binding proteins. Cell 55: 1037–1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell, L. R., J. I. Horabin, P. Schedl and T. W. Cline, 1991. Positive autoregulation of Sex-lethal, by alternative splicing maintains the female determined state in Drosophila. Cell 65: 229–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boggs, R. T., P. Gregor, S. Idriss, J. M Belote and M. McKeown, 1987. Regulation of sexual differentiation in D. melanogaster via alternative splicing of RNA from the transformer gene. Cell 50: 739–747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bopp, D., L. R. Bell, T. W. Cline and P. Schedl, 1991. Developmental distribution of female-specific Sex-lethal proteins in Drosophila melanogaster. Genes Dev. 5: 403–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bopp, D., J. I. Horabin, R. A. Lersh, T. W. Cline and P. Schedl, 1993. Expression of Sex-lethal gene is controlled at multiple levels during the Drosophila oogenesis. Development 118: 797–812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bopp, D., G. Calhoun, J. I. Horabin, M. Samuels and P. Schedl, 1996. Sex-specific control of Sex-lethal is a conserved mechanism for sex determination in the genus Drosophila. Development 122: 971–982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campuzano, S., L. L. Balcells, R. Villares, L. Carramolino, L. García-Alonso et al., 1986. Excess function Hairy-wing mutations caused by gypsy and copia insertions within structural genes of the achaete-scute locus of Drosophila. Cell 44: 303–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casartelli, C. B. R., and E. P. Santos, 1969. DNA and RNA synthesis in Rhynchosiara angelae and the problem of dosage compensation. Caryologia 22: 203–211. [Google Scholar]

- Cline, T. W., 1984. Autoregulatory functioning of a Drosophila gene product that establishes and maintains the sexually determined state. Genetics 107: 231–277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da Cunha, P. R., B. Granadino, A. L. P. Perondini and L. Sánchez, 1994. Dosage compensation in sciarids is achieved by hypertranscription of the single X chromosome. Genetics 138: 787–790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da Silveira, E., 2000 Pufe de DNA C4B de Trichosia pubescens: caracterizacao molecular de um segmento do amplicon e seqüenciamento do gene C4B–2. Tesis Doctoral, Instituto de Biociencias, Universidad de Saso Paulo, Sao Paulo, Brazil.

- Felsenstein, J., 1985. Confidence limits on phylogenies: an approach using the bootstrap. Evolution 39: 783–791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fyrberg, E., J. Beverly, N. Hershey, K. Mixter and N. Davidson, 1981. The actin genes of Drosophila: protein coding regions are highly conserved but intron positions are not. Cell 24: 107–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gebauer, F., D. F. Corona, T. Preiss, P. B. Becker and M. W. Hentze, 1999. Translational control of dosage compensation in Drosophila by Sex-lethal: cooperative silencing via the 5′ and 3′ UTRs of msl-2 mRNA is independent of the poly(A) tail. EMBO J. 18: 6146–6154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerbi, S. A., 1986 Unusual chromosome movements in sciarid flies, pp. 71–104 in Germ Line-Soma Differentiation, edited by W. Hennig. Springer-Verlag, Berlin. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Granadino, B., L. O. F. Penalva, M. R. Green, J. Valcárcel and L. Sánchez, 1997. Distinct mechanisms of splicing regulation in vivo by the Drosophila protein Sex-lethal. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94: 7343–7348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horabin, J. I., and P. Schedl, 1993. Sex-lethal autoregulation requires multiple cis-acting elements upstream and downstream of the male exon and appears to depend largely on controlling the use of the male exon 5′ splice site. Mol. Cell. Biol. 13: 7734–7746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horabin, J., D. Bopp, J. Waterbury and P. Schedl, 1995. Selection and maintenance of sexual identity in the Drosophila germline. Genetics 142: 1521–1535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoshijima, K., K. Inoue, I. Higuchi, H. Sakamoto and Y. Shimura, 1991. Control of doublesex alternative splicing by transformer and transformer-2 in Drosophila. Science 252: 833–836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanaar, R., A. L. Lee, D. Z. Rudner, D. E. Wemmer and D. C. Rio, 1995. Interaction of the Sex-lethal RNA binding domains with RNA. EMBO J. 14: 4530–4539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley, R. L., I. Solovyeva, L. M. Lyman, R. Richman, V. Solovyev et al., 1995. Expression of msl-2 causes assembly of dosage compensation regulators on the X chromosomes and female lethality in Drosophila. Cell 81: 867–877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley, R. L., J. Wang, L. Bell and M. I. Kuroda, 1997. Sex lethal controls dosage compensation in Drosophila by a non-splicing mechanism. Nature 387: 195–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyes, L. N., T. W. Cline and P. Schedl, 1992. The primary sex determination signal of Drosophila acts at the level of transcription. Cell 68: 933–943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura, M., 1980. A simple method for estimating evolutionary rates of base substitutions through comparative studies of nucleotide sequences. J. Mol. Evol. 16: 111–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, S., K. Tamura, I. B. Jakobsen and M. Nei, 2001. MEGA2: molecular evolutionary genetic analysis software. Bioinformatics 17: 1244–1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli, U. K., 1970. Cleavage of structural proteins during assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 277: 680–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lallena, M. J., K. J. Chalmers, S. Llamazares, A. I. Lamond and J. Valcárcel, 2002. Splicing regulation at the second catalytic step by Sex-lethal involves 3′ splice site recognition by SPF45. Cell 3: 285–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucchesi, J. C., and T. Skripsky, 1981. The link between dosage compensation and sex differentiation in Drosophila melanogaster. Chromosoma 82: 217–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maniatis, T., F. Fritsch and J. Sambrook, 1982 Molecular Cloning. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- Meise, M., D. HilfikerKleiner, A. Dübendorfer, C. Brunner, R. Nöthiger et al., 1998. Sex-lethal, the master sex-determining gene in Drosophila, is not sex-specifically regulated in Musca domestica. Development 125: 1487–1494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori, L., and A. L. P. Perondini, 1980. Errors in the elimination of X chromosomes in Sciara ocellaris. Genetics 94: 663–673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller-Holtkamp, F., 1995. The Sex-lethal gene in Chrysomya rufifacies is highly conserved in sequence and exon-intron organization. J. Mol. Evol. 42: 467–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nöthiger, R., M. Jonglez, M. Leuthold, P. Meier-Gersch-Willer and T. Weber, 1989. Sex determination in the germ line of Drosophila depends on genetic signals and inductive somatic factors. Development 107: 505–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver, B., 2002. Genetic control of germline sexual dimorphism in Drosophila. Int. Rev. Cytol. 219: 1–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson, W. R., and D. J. Lipman, 1988. Improved tools for biological sequence comparison. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 85: 2444–2448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penalva, L. O. F., H. Sakamoto, A. Navarro-Sabaté, E. Sakashita, B. Granadino et al., 1996. Regulation of the gene Sex-lethal: a comparative analysis of Drosophila melanogaster and Drosophila subobscura. Genetics 144: 1653–1664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penalva, L. O. F., J. Yokosawa, A. J. Stocker, M. A. M. Soares, M. Graessmann et al., 1997. Molecular characterization of the C-3 DNA puff gene of Rhynchosciara americana. Gene 193: 163–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penalva, L. O. F., and L. Sánchez, 2003. The RNA binding protein Sex-lethal (Sxl) and the control of Drosophila sex determination and dosage compensation. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 67: 343–359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perondini, A. L. P., and E. M. B. Dessen, 1985. Polytene chromosomes and the puffing patterns in the salivary glands of Sciara ocellaris. Rev. Brasil Genet. 8: 465–478. [Google Scholar]

- Roiha, H., J. R. Miller, L. C. Woods and D. M. Glover, 1981. Arrangements and rearrangements of sequences flanking the two types of rDNA insertion in D. melanogaster. Nature 290: 49–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozas, J., J. C. Sánchez-DelBarrio, X. Messeguer and R. Rozas, 2003. DnaSP, DNA polymorphism analyses by the coalescent and other methods. Bioinformatics 19: 2496–2497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz, M. F., M. R. Esteban, C. Doñoro, C. Goday and L. Sánchez, 2000. Evolution of dosage compensation in Diptera: the gene maleless implements dosage compensation in Drosophila (Brachycera suborder) but its homolog in Sciara (Nematocera suborder) appears to play no role in dosage compensation. Genetics 156: 1853–1865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz, M. F., C. Goday, P. González and L. Sánchez, 2003. Molecular analysis and developmental expression of the Sex-lethal gene of Sciara ocellaris (Diptera order, Nematocera suborder). Gene Expr. Patterns 3: 341–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rzhetsky, A., and M. Nei, 1992. A simple method for estimating and testing minimum-evolution trees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 9: 945–967. [Google Scholar]

- Saccone, G., I. Peluso, D. Artiaco, E. Giordano, D. Bopp et al., 1998. The Ceratitis capitata homologue of the Drosophila sex-determining gene Sex lethal is structurally conserved, but not sex-specifically regulated. Development 125: 1495–1500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakamoto, H., K. Inoue, I. Higuchi, Y. Ono and Y. Shimura, 1992. Control of Drosophila Sex-lethal pre-mRNA splicing by its own female-specific product. Nucleic Acids Res. 20: 5533–5540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakashita, E., and H. Sakamoto, 1996. Protein-RNA and protein-protein interactions of the Drosophila Sex-lethal mediated by its RNA-binding domains. J. Biochem. 120: 1028–1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salz, H. K., E. M. Maine, L. N. Keyes, M. E. Samuels, T. W. Cline et al., 1989. The Drosophila female-specific sex-determination gene, Sex-lethal, has stage-, tissue-, and sex-specific RNAs suggesting multiple modes of regulation. Genes Dev. 3: 708–719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuels, M. E., D. Bopp, R. A. Colvin, R. F. Roscigno, M. A. Garcia-Blanco et al., 1994. RNA binding by Sxl proteins in vitro and in vivo. Mol. Cell. Biol. 14: 4975–4990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuels, M., G. Deshpande and P. Schedl, 1998. Activities of the Sex-lethal protein in RNA binding and protein:protein interactions. Nucleic Acids Res. 26: 2625–2637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez, L., and R. Nöthiger, 1983. Sex determination and dosage compensation in Drosophila melanogaster: production of male clones in XX females. EMBO J. 2: 485–491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schüpbach, T., 1985. Normal female germ cell differentiation requires the female X chromosome to autosome ratio and expression of Sex-lethal in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 109: 529–548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sievert, V., S. Kuhn and W. Traut, 1997. Expression of the sex determination cascade genes Sex-lethal and doublesex in the phorid fly Megaselia scalaris. Genome 40: 211–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sievert, V., S. Kuhn, A. Paululat and W. Traut, 2000. Sequence conservation and expression of the Sex-lethal homologue in the fly Megaselia scalaris. Genome 43: 382–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sosnowski, B. A., J. M. Belote and M. McKeown, 1989. Sex-specific alternative splicing of RNA from the transformer gene results from sequence-dependent splice site blockage. Cell 58: 449–459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinmann-Zwicky, M., H. Schmid and R. Nöthiger, 1989. Cell-autonomous and inductive signals can determine the sex of the germ line of Drosophila by regulating the gene Sxl. Cell 57: 157–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, J. D., T. J. Gibson, F. Plewniak, F. Jeanmougin and D. G. Higgins, 1997. The CLUSTAL_X windows interface: flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 25: 4876–4882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres, M., and L. Sánchez, 1991. The sisterless-b function of the Drosophila gene scute is restricted to the state when the X:A ratio signal determines the activity of Sex-lethal. Development 113: 715–722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Towbin, H., T. Staehelin and J. Gordon, 1979. Electrophoretic transfer of proteins from polyacrylamide gels to nitrocellulose sheets, procedure and some applications. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 76: 4350–4354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valcárcel, J., R. Singh, P. D. Zamore and M. R. Green, 1993. The protein Sex-lethal antagonizes the splicing factor U2AF to regulate alternative splicing of transformer pre-mRNA. Nature 362: 171–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J., and L. R. Bell, 1994. The Sex-lethal amino terminus mediates cooperative interactions in RNA binding and is essential for splicing regulation. Genes Dev. 8: 2072–2085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J., Z. Dong and L. R. Bell, 1997. Sex-lethal interactions with protein and RNA. Roles of glycine-rich and RNA binding domains. J. Biol. Chem. 272: 22227–22235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright, F., 1990. The “effective number of codons” used in a gene. Gene 87: 23–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanowitz, J. L., G. Deshpande, G. Calhoun and P. Schedl, 1999. An N-terminal truncation uncouples the sex-transforming and dosage compensation functions of Sex-lethal. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19: 3018–3028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J., H. F. Rosenberg and M. Nei, 1998. Positive Darwinian selection after gene duplication in primate ribonuclease genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95: 3708–3713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]