Abstract

How hypermethylation and hypomethylation of different parts of the genome in cancer are related to each other and to DNA methyltransferase (DNMT) gene expression is ill defined. We used ovarian epithelial tumors of different malignant potential to look for associations between 5’ gene region or promoter hypermethylation, satellite or global DNA hypomethylation, and RNA levels for ten DNMT isoforms. In the quantitative MethyLight assay, 6 of the 55 examined gene loci (LTB4R, MTHFR, CDH13, PGR, CDH1, and IGSF4) were significantly hypermethylated relative to the degree of malignancy (after adjustment for multiple comparisons; P<0.001). Importantly, hypermethylation of these genes was associated with degree of malignancy independently of the association of satellite or global DNA hypomethylation with degree of malignancy. Cancer-related increases in methylation of only two studied genes, LTB4R and MTHFR, which were appreciably methylated even in control tissues, were associated with DNMT1 RNA levels. Cancer-linked satellite DNA hypomethylation was independent of RNA levels for all DNMT3B isoforms, despite the ICF syndrome-linked DNMT3B deficiency causing juxtacentromeric satellite DNA hypomethylation. Our results suggest that there is not a simple association of gene hypermethylation in cancer with altered DNMT RNA levels, and that this hypermethylation is neither the result nor cause of satellite and global DNA hypomethylation.

Keywords: DNA hypomethylation, DNA hypermethylation, DNA methyltransferases, ovarian tumors

Introduction

Increases in methylation of certain DNA sequences and decreases in others are very frequent in human cancers. However, the relationship between cancer-associated hypermethylation of some parts of the genome and hypomethylation of others is still unresolved. In human cancers, hypermethylation is often observed at some 5’ gene or promoter regions that are largely unmethylated in normal somatic tissues (reviewed in Jones & Baylin, 2002). For many of these genes, this hypermethylation has been linked to transcriptional silencing. In addition to these increases in DNA methylation, an overall decrease in the 5-methylcytosine content of the genome relative to various normal postnatal somatic tissues (global DNA hypomethylation) has been described in disparate types of cancers, indicating cancer-specific, and not tissue-specific differences (Gama-Sosa et al., 1983; Ehrlich, 2002). Some cancer-linked global DNA hypomethylation can be attributed to a decrease in satellite DNA methylation, as we have demonstrated for breast cancers, Wilms tumors, and ovarian epithelial carcinomas (Narayan et al., 1998; Jackson et al., 2004; Qu et al., 1999a). Single-copy sequence hypomethylation in tumors is also observed (Feinberg & Vogelstein, 1983; Feinberg et al., 2002; Grunau et al., 2005; Okada et al., 2005). In numerous studies in which both DNA hypomethylation and local DNA hypermethylation (usually CpG islands in 5’ gene or promoter regions) were investigated, these opposite epigenetic changes have been observed in the same tumors (Ehrlich et al., 2002; Narayan et al., 1998; Santourlidis et al., 1999). However, it is not clear whether these two sorts of cancer-associated epigenetic events share a mechanistic basis or etiology.

There might be cross-talk between demethylation and de novo methylation pathways during tumorigenesis, which could make one dependent on the other. For example, CpG island demethylation, which can occur in non-embryonal human cells (Qu & Ehrlich, 1999), might be used as a type of epigenetic repair in normal postnatal cells to attempt to compensate for physiologically inappropriate methylation of CpG islands overlapping promoters of tumor suppressor genes. As is true for conventional DNA repair pathways, this epigenetic repair pathway might be only partially effective and might demethylate many more sequences than just the incorrectly methylated CpG islands. Also, there is evidence that DNA hypermethylation might sometimes be a consequence of hypomethylation, as observed in the hypermethylation that followed hypomethylation of the p53 gene in rats fed a folate/methyl-deficient diet (Pogribny et al., 1997). Studies of azaCR-treated cultured mammalian cells and DNMT antisense-expressing Arabidopsis transgenic lines in which gene hypermethylation was observed against a background of global DNA hypomethylation are also consistent with this hypothesis (Broday et al., 1999; Jacobsen & Meyerowitz, 1997). Lastly, we have recently shown that a DNA repeat can be subject to cancer-associated demethylation and de novo methylation even within the same region on the same DNA molecules (Nishiyama et al., 2005 and unpub. data). In this study, we investigated whether 5’ gene/promoter hypermethylation and global or satellite DNA hypomethylation are linked in ovarian epithelial tumors. For this analysis, we compared ovarian epithelial tumors of varying degrees of malignancy, namely, carcinomas, low malignant potential (LMP, borderline malignant) tumors, and cystadenomas (benign tumors) as well as various control tissues.

We analyzed the relationships of cancer-linked DNA hypermethylation and hypomethylation using 55 different gene loci, three classes of repetitive elements, and global DNA hypomethylation measurements. With all these variables we could potentially investigate hundreds of separate associations. Large numbers of statistical tests increase the likelihood of obtaining P values below 0.05 merely by chance. To correct for this problem of multiple comparisons, we set the false discovery rate for each statistical test at 5% (Benjamini et al., 2001).

We also tested whether there is an association of hypermethylation or hypomethylation of the above-mentioned DNA sequences with RNA levels for ten different DNMT isoforms because cancer-linked hypomethylation or hypermethylation might be explained by differences in expression of different types of DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs). Several studies have reported an increase in the mRNA levels for DNMTs in cancer cells (el-Deiry et al., 1991; Robertson et al., 1999; Robertson, 2001), although this is controversial (Kimura et al., 2003; Lee et al., 1996; Eads et al., 1999). Our study included DNMT3B4 RNA, which encodes a presumably non-catalytic protein and was reported to be significantly overexpressed in hepatocellular carcinomas exhibiting satellite 2 (Sat2) DNA hypomethylation (Saito et al., 2002).

Results

Gene hypermethylation in ovarian tumors

Hypermethylation of 5’gene and promoter regions have been previously described in ovarian cancers (Ahluwalia et al., 2001; Rathi et al., 2002; Wei et al., 2002). In order to look for associations between cancer-linked DNA hypermethylation and hypomethylation, we first searched for gene loci that showed a significant trend of hypermethylation or hypomethylation with malignant potential in ovarian tumors. This was done by MethyLight, a bisulfite modification-dependent, fluorescence-based real-time PCR assay (Eads et al., 2000). We used 60 different MethyLight reactions (Supplementary Table A), encompassing one repetitive element (Alu repeat) and 59 single-copy sequences at 55 different gene loci, mostly CpG islands overlapping the 5’ or promoter regions of these genes. The Alu element targeted by our MethyLight reaction closely resembles Alu repeats belonging to the AluSx or AluSq subfamilies. The reactions were selected partly from a pre-screen of ovarian tumors (Widschwendter et al., 2004). MethyLight data are expressed as percent methylation relative to a reference (PMR), in vitro-methylated DNA that is included in each analysis.

Supplementary Table A.

MethyLight Reaction Details

| HUGO gene symbol | Reaction ID | Gene name | GenBank accession number | Chromosom al location | Amplicon location (GenBank numbering, bp) | Location of amplicon in gene (e.g., promoter, exon) | Forward primer sequence | Reverse primer sequence | Probe sequence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABCB1 | ABCB1-M1B | ATP-binding cassette, sub-family B (MDR/TAP), member | AC002457 | 7q21.1 | 36663-36585 | Promoter | TCGGGTCGGGAGTAGTTATTTG | CGACTATACTCAACCCACGCC | 6FAM-ACGCTATTCCTACCCAACCAATCAACCTCA |

| ALU a | ALU-M4B | AL441992 | 9q34.1 | 118955 - 119057 | Upstream a | AGGTCGAGGTCGGCGG | CCACGCCCGACTAATTTTATATCTT | 6FAM-CAAACTAATCTCAAACTCCCGACCTCAAACGA | |

| APC | APC-M1B | Adenomatous polyposis coli | AC109473 | 5q21-q22 | 60979-61052 | Promoter | GAACCAAAACGCTCCCCAT | TTATATGTCGGTTACGTGCGTTTATAT | 6FAM-CCCGTCGAAAACCCGCCGATTA-BHQ-1 |

| ARHI | ARHI-M1B | Ras homolog gene family, member I;NOEY2 | AF202543 | 1p31 | 1953 - 2038 | Promoter | GCGTAAGCGGAATTTATGTTTGT | CCGCGATTTTATATTCCGACTT | 6FAM-CGCACAAAAACGAAATACGAAAACGCAAA- |

| BCL2 | BCL2-M1B | B-cell CLL/lymphoma 2 | AY220759 | 18q21.3 | 1221-1304 | Exon1 | TCGTATTTCGGGATTCGGTC | AACTAAACGCAAACCCCGC | 6FAM-ACGACGCCGAAAACAACCGAAATCTACA-B |

| CACNA1G | CACNA1G-M1B | Calcium channel, voltage-dependent, alpha 1G subunit | AC021491 | 17q22 | 48345 - 48411 | Exon1 | TTTTTTCGTTTCGCGTTTAGGT | CTCGAAACGACTTCGCCG | 6FAM-AAATAACGCCGAATCCGACAACCGA-BHQ |

| CALCA | CALCA-M1B | Calcitonin | X15943 | 11p15.2-p15.1 | 1706 - 1807 | Promoter | GTTTTGGAAGTATGAGGGTGACG | TTCCCGCCGCTATAAATCG | 6FAM-ATTCCGCCAATACACAACAACCAATAAACG |

| CCND2 | CCND2-M1B | Cyclin D2 | AC006122 | 12p13 | 63476-63540 | Promoter | GGAGGGTCGGCGAGGAT | TCCTTTCCCCGAAAACATAAAA | 6FAM-CACGCTCGATCCTTCGCCCG-BHQ-1 |

| CDH1 | CDH1-M1B | E-Cadherin | AC099314 | 16q.22.1 | 80635-80704 | Promoter | AATTTTAGGTTAGAGGGTTATCGCGT- | TCCCCAAAACGAAACTAACGAC | 6FAM-CGCCCACCCGACCTCGCAT-BHQ-1 |

| CDH1 | CDH1-M2B | E-Cadherin | AC099314 | 16q.22.1 | 80648-80743 | Promoter | AGGGTTATCGCGTTTATGCG | TTCACCTACCGACCACAACCA | 6FAM-ACTAACGACCCGCCCACCCGA-BHQ-1 |

| CDH13 | CDH13-M1B | H-Cadherin | AC092351 | 16q24.2-q24.3 | 61395-61293 | Exon1/Intron1 | AATTTCGTTCGTTTTGTGCGT | CTACCCGTACCGAACGATCC | 6FAM-AACGCAAAACGCGCCCGACA-BHQ-1 |

| CTSD | CTSD-M1B | Cathepsin D | AC068580 | 11p15.5 | 43076-43166 | Promoter | TACGTTTCGCGTAGGTTTGGA | TCGTAAAACGACCCACCCTAA | 6FAM-CCTATCCCGACCGCCGCGA-BHQ-1 |

| CTSD | CTSD-M2B | Cathepsin D | AC068580 | 11p15.5 | 43206-43270 | Promoter | AAGTTGGGTCGGGTTGATTTC | ATAATACGCCTACCGCGCC | 6FAM-ACAATTCCCGCCGCTCGCG-BHQ-1 |

| CYP1B1 | CYP1B1-M1B | Cytochrome P450, family 1, subfamily B, polypeptide 1 | U56438 | 2p21 | 2905 - 2990 | Promoter | GTGCGTTTGGACGGGAGTT | AACGCGACCTAACAAAACGAA | 6FAM-CGCCGCACACCAAACCGCTT-BHQ-1 |

| DAPK1 | DAPK1-M1B | Death-associated protein kinase 1 | X76104 | 9q34.1 | 137 - 204 | Exon1 | TCGTCGTCGTTTCGGTTAGTT | TCCCTCCGAAACGCTATCG | 6FAM-CGACCATAAACGCCAACGCCG-BHQ-1 |

| DNAJD1 | DNAJD1-M1B | DNAJ domain-containing; MCJ | AF126743 | 13q13 | 407 - 487 | Exon1 | TTTCGGGTCGTTTTGTTATGG | ACTACAAATACTCAACGTAACGCAAACT | 6FAM-TCGCCAACTAAAACGATAACACCACGAACA |

| DPH2L1 | DPH2L1-M1B | OVCA1; DPH2L | AC090617 | 17p13.3 | 108552 - 108621 | Exon1 | ACGCGGAGAGCGTAGATATTG | CCGCCCAACGAATATCCC | 6FAM-CCCGCTAACCGATCGACGATCGA-BHQ-1 |

| EPM2AIP1 | EPM2BAIP1-M1B | EPM2A (laforin) interacting protein 1; KIAA0766 | U26559 | 3p21.3 | 254 - 341 | Exon1 | CGTTATATATCGTTCGTAGTATTCGTGTTT | CTATCGCCGCCTCATCGT | 6FAM-CGCGACGTCAAACGCCACTACG-BHQ-1 |

| ESR1 | ESR1-M1B | Estrogen receptor alpha | X62462 | 6q25.1 | 2784 - 2884 | Exon1 | GGCGTTCGTTTTGGGATTG | GCCGACACGCGAACTCTAA | 6FAM-CGATAAAACCGAACGACCCGACGA-BHQ-1 |

| ESR2 | ESR2-M1B | Estrogen receptor beta | AL161756 | 14q | 82093-82164 | Exon1 | TTTGAAATTTGTAGGGCGAAGAGTAG | ACCCGTCGCAACTCGAATAA | 6FAM-CCGACCCAACGCTCGCCG-BHQ-1 |

| FBXW7 | FBXW7-M1B | F-box protein hCdc4 | AC023424 | 4q31.23 | 113422 - 113545 | Exon1 | TGTCGTTGCGGTTGGGAT | CGAAAATAAATAACTACTCCGCGATAA | 6FAM-ACGCCAAAACTTCTACCTCGTCCCGTAA-BHQ |

| FHIT | FHIT-M1B | Fragile Histidine Triad | U76263 | 3p14.2 | 193 - 267 | Intron1 | GGCGCGGGTTTGGG | CGCCCCGTAAACGACG | 6FAM-CACTAAACTCCGAAATAATAACCTAACGCGCG |

| GSTP1 | GSTP1-M1B | Glutathione-S transferase pi1 | M24485 | 11q13 | 1146 - 1245 | Promoter/Exon1 | GTCGGCGTCGTGATTTAGTATTG | AAACTACGACGACGAAACTCCAA | 6FAM-AAACCTCGCGACCTCCGAACCTTATAAAA-E |

| HIC1 | HIC1-M1B | Hypermethylated in cancer 1 | L41919 | 17p13.3 | 562 - 662 | Promoter/Exon1 | GTTAGGCGGTTAGGGCGTC | CCGAACGCCTCCATCGTAT | 6FAM-CAACATCGTCTACCCAACACACTCTCCTACG |

| HSD17B4 | HSD17B4-M1B | 17beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase | AF057720 | 5q21 | 1581 - 1651 | Exon1 | TATCGTTGAGGTTCGACGGG | TCCAACCTTCGCATACTCACC | 6FAM-CCCGCGCCGATAACCAATACCA-BHQ-1 |

| ICAM1 | ICAM1B-M1B | Intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (CD54) | M65001 | 19p13.3-p13.21 | 187 - 1266 | Promoter | GGTTAGCGAGGGAGGATGATT | TCCCCTCCGAAACAAATACTACAA | 6FAM-TTCCGAACTAACAAAATACCCGAACCGAAA |

| IGSF4 | IGSF4-M1B | Immunoglobulin superfamily, member 4 | AB017554 | 11q23.2 | 448 - 529 | Promoter/Exon1 | GGGTTTCGGAGGTAGTTAACGTC | CACTAAAATCCGCTCGACAACAC | 6FAM-ACACTCGCCATATCGAACACCTACCTCAAA |

| LTB4R | LTB4R-M1B | Leukotriene B4 receptor; BLT1 | AB008193 | 14q11.2-q12 | 2257 - 2332 | Promoter | GCGTTGGTTTTATCGGAAGG | AAACCGTAATTCCCGCTCG | 6FAM-GACTCCGCCCAACTTCGCCAAAA-BHQ-1 |

| MBD2 | MBD2-M1B | Methyl-CpG binding domain protein 2 | AC093462 | 18q21 | 143589-143667 | Exon1 | AGGCGGAGATAAGATGGTCGT | CCCTCCTACCCGAAACGTAAC | 6FAM-CGACCACCGCCTCTTAAATCCTCCAAA-BHQ |

| MGMT | MGMT-M1B | O6-methylguanine methyltransferase | U95038 | 10q26 | 206 - 297 | Intron1 | CTAACGTATAACGAAAATCGTAACAACCA | AGTATGAAGGGTAGGAAGAATTCGG | 6FAM-CCTTACCTCTAAATACCAACCCCAAACCCG |

| MGMT | MGMT-M2B | O6-methylguanine methyltransferase | X61657 | 10q26 | 1067 - 1149 | Exon1/Intron1 | GCGTTTCGACGTTCGTAGGT | CACTCTTCCGAAAACGAAACG | 6FAM-CGCAAACGATACGCACCGCGA-BHQ-1 |

| MINT1 b | MINT1-M1B | Methylated in tumor fragment 1 | AF135501 | 5q13-14 | 232 - 360 | Intron1 | GGGTTGAGGTTTTTTGTTAGCG | CCCCTCTAAACTTCACAACCTCG | 6FAM-CTACTTCGCCTAACCTAACGCACAACAAACG |

| MINT2 b | MINT2-M1B | Methylated in tumor fragment 2 | AC007238 | 2p22-21 | 74436 - 74524 | Unknownb | TTGAGTGGCG CGTTTCGT | TCCCCGCCTAAACCAACC | 6FAM-CTTACGCCACCGCCTCCGA-BHQ-1 |

| MINT31 b | MINT31-M1B | Methylated in tumor fragment 31 | AC021491 | 17q22 | 50060 - 50130 | Intron1 | GTCGTCGGCGTTATTTTAGAAAGTT | CACCGACGCCCAACACA | 6FAM-ACGCTCCGCTCCCGAATACCCA-BHQ-1 |

| MLH1 | MLH1-M2B | Mut L homolog 1 | U26559 | 3p21.3 | 657-740 | Promoter | AGGAAGAGCGGATAGCGATTT | TCTTCGTCCCTCCCTAAAACG | 6FAM-CCCGCTACCTAAAAAAATATACGCTTACGCG |

| MTHFR | MTHFR-M1B | 5,10-methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (NADPH) | BC053509 | 1p36.3 | 10625-10715 | Exon2 | TGGTAGTGAGAGTTTTAAAGATAGTTCGA | CGCCTCATCTTCTCCCGA | 6FAM-TCTCATACCGCTCAAAATCCAAACCCG-BHQ |

| MYOD1 | MYOD1-M1B | Myogenic determining factor 3/MYF3/PUM | AF027148 | 11p15.4 | 9889 - 9962 | Promoter | GAGCGCGCGTAGTTAGCG | TCCGACACGCCCTTTCC | 6FAM-CTCCAACACCCGACTACTATATCCGCGAAA |

| NR3C1 | NR3C1-M1B | Nuclear receptor subfamily 3, group C, member 1 | S68374 | 5q31 | 842 - 916 | Promoter | GGGTGGAAGGAGACGTCGTAGT | AAACTTCCGAACGCGCG | 6FAM-GTCCCGATCCCAACTACTTCGACCG-BHQ-1 |

| PGR | PGR-M2B | Progesterone receptor B | X51730 | 11q22-q23 | 811 - 904 | Exon1 (Isoform B) | TTATAATTCGAGGCGGTTAGTGTTT | TCGAACTTCTACTAACTCCGTACTACGA | 6FAM-ATCATCTCCGAAAATCTCAAATCCCAATAATACG |

| PTEN | PTEN-M1B | Phosphatase and tensin homolog | AF143312 | 10q23.3 | 1060 - 1147 | Promoter | GTTTCGCGTTGTTGTAAAAGTCG | CAATATAACTACCTAAAACTTACTCGAACCG | 6FAM-TTCCCAACCGCCAACCTACAACTACACTTA |

| PTGS2 | PTGS2-M1B | Prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 2; Cox2 | AF044206 | 1q25.2-q25.3 | 6779 - 6924 | Promoter | CGGAAGCGTTCGGGTAAAG | AATTCCACCGCCCCAAAC | 6FAM-TTTCCGCCAAATATCTTTTCTTCTTCGCA-BHQ |

| RARB | RARB-M1B | Retinoic acid receptor, beta; HAP; RRB2; NR1B2 | X56849 | 3p24 | 921 - 1006 | Exon1 | TTTATGCGAGTTGTTTGAGGATTG | CGAATCCTACCCCGACGATAC | 6FAM-CTCGAATCGCTCGCGTTCTCGACAT-BHQ-1 |

| RASSF1 | RASSF1-M1B | Ras association (RalGDS/AF-6) domain family 1 | AC002481 | 3p21.3 | 18107 - 18171 | Exon1 | ATTGAGTTGCGGGAGTTGGT | ACACGCTCCAACCGAATACG | 6FAM-CCCTTCCCAACGCGCCCA-BHQ-1 |

| RBP1 | RBP1-M1B | Retinol binding protein 1 | X07437 | 3q23 | 509 - 598 | Promoter/Exon1 | CGCGTTGGGAATTTAGTTGTC | GATACTACGCGAATAATAAACGACCC | 6FAM-ACGCCCTCCGAAAACAAAAAACTCTACG |

| RNR1 | RNR1-M1B | Ribosomal RNA | X01547 | 13p12 | 219 - 293 | Promoter | CGTTTTGGAGATACGGGTCG | AAACAACGCCGAACCGAA | 6FAM-ACCGCCCGTACCACACGCAAA-BHQ-1 |

| S100A2 c | S100A2-M1B | S100 calcium binding protein A2 | Y07755 | 1q21 | 1388 - 1469 | Upstreamc | TGTTTGAGTCGTAAGTAGGGCGT | CGTATCATTACAATACCGACCTCCT | 6FAM-ATCCTCCCTTTCTTATCCGCCAAACCCT-BHQ |

| SASH1 | SASH1-M2B | KIAA0790 | AL513164 | 6q24-25 | 97703 - 97786 | Exon1 | TAGTTCGTGGTTATTTAGATTCGAGGG | GCGCTACATACCCCGACG | 6FAM-CCGCGAAAACCCTTCGCAAACG-BHQ-1 |

| SCAM-1 | SCAM-1-M1B | Vinexin beta (SH3-containing adaptor molecule-1 | AC037459 | 8p21 | 86569-86641 | Exon1 | GTTTCGGTTGTCGTTGGGTT | ACGCCGACGAACTCTACGC | 6FAM-ACGACGCAATCAAAACCCGCGA-BHQ-1 |

| SCGB3A1 | SCGB3A1-M1B | Secretoglobin, family 3A, member1; HIN1 | AC122714 | 5q35-qter | 80825 - 80912 | Exon1/Intron1 | GGCGTAGCGGGCGTC | CTACGTAACCCTATCCTACAACTCCG | 6FAM-CGAACTCCTAACGCGCACGATAAAACCTAA |

| SEZ6L | SEZ6L-M1B | Seizure related 6 homolog (mouse)-like; KIAA0927 | AL022337 | 22q12.1 | 87324 - 87426 | Promoter | GCGTTAGTAGGGAGAGAAAACGTTC | ATACCAACCGCCTCCTCTAACC | 6FAM-CCGTCGACCCTACAAAATTTAACGCCA-BHQ |

| SOCS1 | SOCS1-M1B | Suppressor of cytokine signaling 1 | AC009121 | 16p13.13 | 108805 - 108888 | Exon1 | GCGTCGAGTTCGTGGGTATTT | CCGAAACCATCTTCACGCTAA | 6FAM-ACAATTCCGCTAACGACTATCGCGCA-BHQ-1 |

| STK11 | STK11-M1B | Serine/threonine kinase 11 (Peutz-Jeghers syndrome); | AC011544 | 19p13.3 | 27020 - 27112 | Exon2 | TGAGGTTCGGGTTTTATTGGAA | GAATCCAAACCCGATACAAAATCT | 6FAM-CGAAAATCCGAAACGACGACTCAAACG-BHQ |

| STK11 | STK11-M2B | Serine/threonine kinase 11 (Peutz-Jeghers syndrome); | AC011544 | 19p13.3 | 26084 - 26187 | Promoter | AATTAACGGGTGGGTACGTCG | GCCATCTTATTTACCTCCCTCCC | 6FAM-CGCACGCCCGACCGCAA-BHQ-1 |

| SYK | SYK-M1B | Spleen tyrosine kinase | AL354862 | 9q22 | 50803-50879 | Promoter/Exon1 | GGGCGCGATATTGGGAG | GCGACTCTTCCTCATTTTAAACAAC | 6FAM-CCTTAACGCGCCCGAACAAACG-BHQ-1 |

| TERT | TERT-M1B | Telomerase reverse transcriptase | AC114291 | 5p15.33 | 179159-179275 | Promoter | GGATTCGCGGGTATAGACGTT | CGAAATCCGCGCGAAA | 6FAM-CCCAATCCCTCCGCCACGTAAAA-BHQ-1 |

| TFF1 | TFF1-M1B | Trefoil factor 1; pS2 | AB038162 | 21q22.3 | 499-646 | Promoter | TAAGGTTACGGTGGTTATTTCGTGA | ACCTTAATCCAAATCCTACTCATATCTAAAA | 6FAM-CCCTCCCGCCAAAATAAATACTATACTCACTACAAAA |

| TIMP3 | TIMP3-M1B | Tissue Inhibitor of metallinoproteinase 3 | AL023282 | 22q12.3 | 5424-5518 | Exon1 | GCGTCGGAGGTTAAGGTTGTT | CTCTCCAAAATTACCGTACGCG | 6FAM-AACTCGCTCGCCCGCCGAA-BHQ-1 |

| TNFRSF25 | TNFRSF25-M1B | TNF receptor superfamily, member 25 | AY254324 | 1p36.2 | 1930-1998 | Exon1 | GCGGAATTACGACGGGTAGA | ACTCCATAACCCTCCGACGA | 6FAM-CGCCCAAAAACTTCCCGACTCCGTA-BHQ-1 |

| TWIST1 | TWIST1-M1B | Twist homolog | AC003986 | 7p21.2 | 136772-136845 | Intron1 | GTAGCGCGGCGAACGT | AAACGCAACGAATCATAACCAAC | 6FAM-CCAACGCACCCAATCGCTAAACGA-BHQ-1 |

| VDR | VDR-M1B | Vitamin D receptor | AY342401 | 12q12-q14 | 1542-1632 | Promoter | ACGTATTTGGTTTAGGCGTTCGTA | CGCTTCAACCTATATTAATCGAAAATACA | 6FAM-CCCACCCTTCCTACCGTAATTCTACCCAA-E |

This reaction is designed against an Alu repetitive element located 550 bp upstream of the ENDOG transcription start site. However, the signal strength indicates that a large number of Alu repetitive elements

MINT1 , MINT2 and MINT31 are anonymous genomic fragments for which no clear relationship with any known gene has been established.

The MINT1 clone is located 500 bp downstream from the transcription start site of a putative gene, SV2CT , for which only an mRNA has been described (GenBank Accession Number AK094917).

The MINT31 clone overlaps intron1 of a putative gene for which only an mRNA has been described (GenBank Accession Number BC041476).

This reaction is located 3.2 kb upsream of the transcription start site of S100A2 .

We examined DNA from 19 ovarian carcinomas, 20 LMP tumors, and 21 cystadenomas, all of epithelial origin. In most studies of epigenetic changes in malignancy, cancers and normal tissues are compared. For ovarian epithelial tumors, we did not have access to normal cells representative of the very minor fraction of ovarian epithelial cells that appear to be the cells of origin of this type of cancer (Dubeau, 1999). While the three types of ovarian tumors probably do not represent a disease continuum (McCluskey & Dubeau, 1997) with one developing from another, they seem to share a common cell of origin (Zheng et al., 1995), with the cystadenoma cells most resembling the normal cells. In addition, both ovarian carcinomas and LMP tumors are technically classified as malignant tumors, while they differ in their invasive potential. Therefore, these three related tumor types make an attractive model for analysis of epigenetic changes in DNA in neoplasms of different degrees of malignancy, but of similar cell type of origin.

We also included normal adult cerebellum, heart, kidney, and spleen in the analysis in order to have a diverse collection of normal postnatal somatic tissues to identify DNA sequences with nearly invariant methylation over a wide range of controls. However, our focus on identifying a trend of DNA methylation by degree of malignancy eliminated genes like DNAJD1 (MCJ), which displayed much more methylation in carcinomas than in the control tissues but no hypermethylation in carcinomas compared with LMP tumors or cystadenomas (data not shown). That finding probably reflects highly selective tissue-specific differences in DNAJD1 methylation (Strathdee et al., 2004).

Twenty of the 55 examined loci displayed an association of mean PMR values with the degree of malignancy at P≤0.05, but without adjustment for multiple comparisons (Table 1). Six of these showed a significant trend of hypermethylation with degree of malignancy after adjustment for multiple comparisons. These genes, LTB4R (leukotriene B4 receptor 1; BLT1), MTHFR (5,10-methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase, PGR (progesterone receptor B), CDH13 (H-cadherin), IGSF4 (immunoglobulin superfamily, member 4), and CDH1 (CDH1 M2 primer/probe set; Table 1), had PMR values higher than the median for cystadenomas in 95, 100, 100, 79, 90, and 94% of the carcinomas, respectively. Also, in the majority of carcinomas, all but one of these genes (IGSF4) had higher PMR values than the mean of the various control tissues. With the exception of MTHFR, genes were analyzed in promoter or 5’ transcribed regions overlapping a CpG island. We examined CDH1 in two overlapping amplicons (M1 and M2, Supplementary Table A) within the CpG-island promoter. Although only one of these primer-probe sets (M2) displayed a significant trend of hypermethylation with malignancy, both sets showed more methylation in carcinomas than in LMP tumors and cystadenomas (data not shown).

Table 1.

Association of methylation of various DNA sequences in ovarian tumors with the degree of malignancy and with DNMT1 RNA levels

| Mean PMR for tumorsb |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MethyLight Reactiona (Gene-Primer Set) | Mean PMR for controlsc | Carcinoma | LMP | Cystadenoma | P-value for assoc. with degree of malignancyd | P-value for assoc. of carcinoma PMR with DNMT1 RNA levelse |

| LTB4R-M1B | 24 | 67 | 40 | 10 | 0.3 x 10−8 | 0.0005 |

| MTHFR-M1B | 26 | 51 | 20 | 16 | 0.5 x 10−8 | 0.002 |

| CDH1- M2B d | 0.38 | 0.60 | 0.08 | 0.03 | 0.7 x 10−4 | 0.12 |

| PGR-M2B | 1.3 | 2.3 | 2.8 | 0.13 | 0.9 x 10−4 | 0.47 |

| CDH13-M1B | 0.05 | 7.7 | 1.1 | 0.26 | 0.2 x 10−3 | 0.23 |

| IGSF4-M1B | 0.27 | 0.25 | 0.14 | 0.03 | 0.3 x 10−3 | 0.93 |

| MINT31-M1B | 0.48 | 6.30 | 0.32 | 0.30 | 0.001 | |

| MYOD1-M1B | 0.88 | 0.78 | 0.33 | 0.13 | 0.001 | |

| RARB-M1B | 0.52 | 0.38 | 0.21 | 0.19 | 0.003 | |

| SEZ6L-M1B | 0.44 | 3.22 | 0.62 | 0.25 | 0.004 | |

| TIMP3-M1B | 0.82 | 0.42 | 0.48 | 0.15 | 0.005 | |

| ALU-M4B | 114 | 79 | 100 | 106 | 0.01 | |

| MLH1-M2B | 0 | 4.62 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.01 | |

| ESR1-M1B | 0.38 | 0.73 | 0.71 | 2.7 | 0.02 | |

| TERT-M1B | 0 | 0.22 | 0 | 0 | 0.02 | |

| MGMT-M1B | 23 | 7.8 | 14 | 14 | 0.02 | |

| CALCA-M1B | 1.1 | 2.3 | 0.22 | 0.44 | 0.02 | |

| PTGS2-M1B | 1.0 | 0.24 | 0.18 | 0.11 | 0.03 | |

| RASSF1-M1B | 13 | 43 | 9.2 | 1.7 | 0.03 | |

| EPM2A1P1-M1B | 0 | 4.52 | 0.00 | 0.0 | 0.04 | |

MethyLight reaction nomenclature consists of the gene symbol, followed by a suffix indicating the particular reaction design for that locus. The letter “M” denotes a methylation-specific reaction, followed by a serial number specifying the methylation-specific reaction design (see Supplementary Table A). The letter “B” in the suffix indicates that a black-hole-quencher version of the reaction was used. Most of these reactions are located in the promoter or 5’ regions of the indicated genes (Supplementary Table A).

Mean PMR values for DNA methylation are shown for genes with malignancy-related hypermethylation or hypomethylation in a comparison of the three following groups of ovarian epithelial tumors: 19 carcinomas, 20 LMP tumors (borderline cancers), and 21 cystadenomas.

Mean PMR values from 9 somatic tissues (brain, kidney, lung, heart, and spleen) from controls .

For testing the association of methylation with the degree of malignancy, the mean PMR values of 60 MethyLight reactions, which recognize 55 different gene loci, and one Alu element, were compared in the three tumor groups. The reactions in this table exhibited a significant association of mean PMR values with the degree of malignancy (P≤ 0.05, without adjustment for multiple comparisons). A few reactions with mean PMR values of ≤0.1 for all three types of tumors were excluded from this table. The DNA sequences that displayed significant associations of PMR with the degree of malignancy after adjustment for multiple comparisons (false discovery rate set at 5%) are shown in boldface.

The P-values for the association of DNMT1 RNA levels with PMR values in the carcinomas are shown for the 6 boldfaced genes. In carcinomas, these genes displayed P-values of >0.05 for the association of their PMR values with RNA levels for DNMT2, DNMTA1, DNMT3A2, DNMT3A (all isoforms), DNMT3B1, DNMT3B1/3B2, DNMT3B3, DNMT3B4, DNMT3B5, DNMT3B (all isoforms), and DNMT3L. For the association of PMR for LTB4R and MTHFR with DNMT1 RNA levels, R values were 0.75 and 0.69, respectively. Of these two associations, only that of LTBR PMR values with DNMT1 achieved statistical significance after adjustment for multiple comparisons (false discovery rate of 5%).

While MethyLight could detect either hyper- or hypomethylation, hypermethylation in the examined gene regions predominated (Table 1). Interestingly, one of hypomethylated sequences was an Alu repeat and, therefore, monitored cancer-linked Alu repeat hypomethylation. In another study (unpub. data), we recently documented Alu repeat hypomethylation in cancer with different primers in MethyLight assays.

Hypomethylation of satellite DNA and global DNA hypomethylation in ovarian tumors

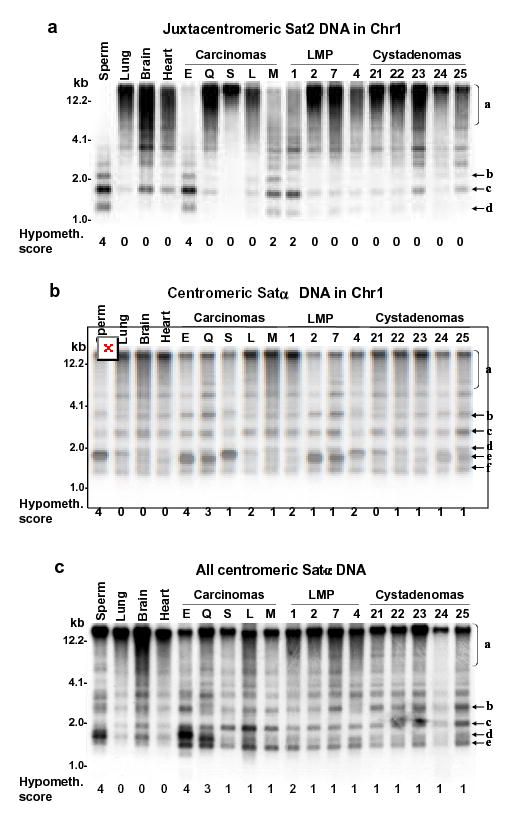

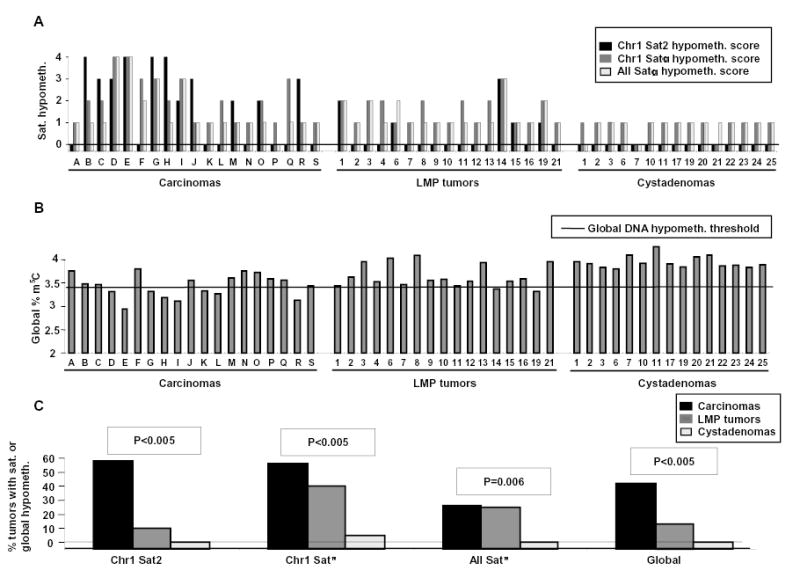

We previously showed extensive satellite DNA hypomethylation in several types of human cancers (Narayan et al., 1998; Qu et al., 1999a; Qu et al., 1999b). In order to compare gene-region hypermethylation with satellite DNA hypomethylation in the ovarian tumors, we next analyzed methylation at satellite α throughout the centromeres (all Satα), Satα in chromosome 1 (Chr1 Satα), and satellite 2 in the largest juxtacentromeric heterochromatin region (Chr1 Sat2 at 1qh) using digests made with the CpG methylation-sensitive BstBI. Southern blotting revealed that carcinomas and LMP tumors were frequently hypomethylated in these satellite DNAs relative to all tested normal postnatal somatic tissues (Figs. 1 and 2). The percentages of tumors displaying strong hypomethylation (score 3 or 4 on a scale of 0 – 4) in carcinomas, LMP tumors, and cystadenomas were 42, 5, and 0, for Chr1 Sat2; 32, 5, and 0, for Chr1 Satα; and 21, 5, and 0, for all Satα, respectively. Differences in the extent of satellite DNA hypomethylation or global DNA hypomethylation vs. the malignant potential were highly significant after adjustment for multiple comparisons (Fig. 2). These results were similar to those seen for Chr1 Sat2 in a much smaller study of ovarian epithelial tumors (Qu & Ehrlich, 1999). Some carcinomas had hypomethylation levels as extreme as in sperm (hypomethylation score, 4). Among all the ovarian tumors, Chr1 Sat2, Chr1 Satα, all Satα hypomethylation, and global DNA hypomethylation were significantly associated with one another in each pair-wise combination (P<0.005 except P=0.009 for global DNA hypomethylation vs. all Satα hypomethylation). In a comparison of cystadenomas vs. control somatic tissues, Chr1 Satα and all Satα, but not Chr1 Sat2, displayed significant, but mostly weak (Fig. 1), hypomethylation (P<0.001). This may reflect atypical tissue-specific differences or very early epigenetic changes during tumorigenesis. Therefore, Sat2 hypomethylation appears to be a more specific cancer marker than Satα hypomethylation, as in our recent study of breast cancers (Jackson et al., 2004).

Fig. 1. Southern blot analysis of satellite DNA hypomethylation in ovarian epithelial tumors.

Examples of satellite DNA hypomethylation in BstBI digests of ovarian carcinomas in a single blot hybridized three times. Normal postnatal somatic DNAs and sperm DNA are the hypermethylated and hypomethylated standards, respectively. (A) juxtacentromeric Chr1 Sat2 probe and (B) centromeric Chr1 Satα probe under high-stringency hybridization conditions; (C), centromeric Chr1 Satα probe under low-stringency conditions that allow hybridization to DNA from most of the centromeres. Scoring of hypomethylation was by phosphorimager quantitation of <4-kb vs. >4-kb signal and visual comparison of bands b, c, d, e, and f to region a.

Fig. 2. Comparison of satellite DNA hypomethylation and global DNA hypomethylation in ovarian epithelial tumors of different malignant potential (A).

The levels of satellite DNA hypomethylation (score 0–4) and (B) the percent of total DNA cytosine residues that were methylated are plotted for individual tumors. Not shown are three LMP tumors and six cystadenomas analyzed only for satellite DNA methylation. The horizontal line is the global DNA hypomethylation threshold, i.e., the minimum percentage of methylated cytosine residues found in diverse normal postnatal somatic tissues (3.43; range for normal tissue types, 3.43–4.1). As a conservative estimate of an overall deficiency of m5C in tumor DNAs, global methylation levels of <3.43 were considered hypomethylated. (C) The percentage of tumors displaying global DNA hypomethylation or strong-to-moderate satellite DNA hypomethylation (score 2, 3, or 4) relative to all the somatic controls is shown. P-values for hypomethylation scores vs. degree of malignancy are given. For all of these DNA hypomethylation parameters, except the all-Satα hypomethylation, there was a significant association with the degree of malignancy after adjustment for multiple comparisons.

Independent associations of DNA hypomethylation and hypermethylation with malignant potential

To examine possible interrelationships of the DNA hypermethylation and hypomethylation variables that showed a significant association with the degree of malignancy, we used stepwise regression analysis to eliminate redundancy and select those variables that independently capture the association of each type of methylation change with the degree of malignancy. The minimal subset of methylation variables that independently predicted the degree of malignancy in ovarian tumors comprised LTB4R, MTHFR, and CDH1 hypermethylation plus Chr1 Sat2 and Chr1 Satα hypomethylation. A multivariate regression analysis showed that hypermethylation variables and hypomethylation variables independently predict the degree of malignancy in ovarian tumors in a final model that included LTB4R (P<0.005), MTHFR (P=0.006), CDH1 (P=0.02), and Satα (P=0.005). Likewise, when we examined global hypomethylation in combination with gene hypermethylation variables, both sets independently predicted degree of malignancy in ovarian tumors in a final model that included MTHFR (P<0.005), BLT1 (P=0.02), and global hypomethylation (P<0.005). Therefore, promoter or 5’ gene hypermethylation and satellite or global DNA hypomethylation apparently occur independently in ovarian cancer.

Although the above analysis showed that there was no general association between hypermethylation and hypomethylation variables across all types of ovarian epithelial tumors, there may be links between hypermethylation of a subclass of affected gene regions and hypomethylation of satellite DNA restricted to the frankly malignant ovarian carcinomas. Interestingly, using just the set of carcinomas, we found that CDH13 showed a negative association between hypermethylation of its CpG-rich 5’ gene region and hypomethylation of Chr1 Sat2 (P=0.01), suggesting that some gene loci may be subject to the same forces that drive hypomethylation at repetitive sequences.

Lack of correlations of these epigenetic changes with age

Despite the fact that the tumor tissues, were obtained from a wide age-range of ovarian cancer patients, we did not find a significant association between gene hypermethylation and patient age, as has been found for certain genes in specific tissues. (Issa, 2000). We could do this analysis for the LMP and cystadenoma patients because their ages at the time of surgery were available and encompassed a large range, 17 to 67 and 16 to 75 years, respectively. Among the hypomethylation parameters, only all-Satα DNA hypomethylation was significantly associated with age, and only for LMP tumor-containing patients (P=0.03). Similarly, none of the genes in Table 1 showed significant age-related differences in PMR values. These data suggest that age-related methylation changes did not significantly impact the results of this study.

RNA levels for DNA methyltransferases vs. methylation changes

The role of altered expression of DNMTs in DNA hypomethylation and hypermethylation in cancer is uncertain and may involve changes in mRNA or protein expression. Alterations in the expression of specific DNMT splice variants have been described in various human cancers (Robertson et al., 1999; Saito et al., 2002; Weisenberger et al., 2004; Chen et al., 2002). However, identifying and distinguishing individual DNMT protein splice variants using commercially available antibodies is often difficult. Using real-time RT-PCR, we are able to quantitatively identify each DNMT mRNA isoform with a higher sensitivity and specificity than with western blot-based methods for protein detection. Therefore, we looked for possible relationships between levels of DNA methyltransferase mRNA isoforms and methylation changes in the ovarian carcinomas and LMP tumors. We examined human DNMT isoforms, namely, DNMT1, the major DNMT for maintenance methylation; DNMT3A (two isoforms) and DNMT3B (five isoforms), which are the main DNMTs for de novo methylation; DNMT2 (Tang et al., 2003), which has only a very weak catalytic activity (Hermann et al., 2003); and DNMT3L, a DNMT-like protein missing parts of the catalytic domain but capable of modulating the activity of DNMT3A (Chedin et al., 2002). First, we found that levels of DNMT3A1 and DNMT2 RNAs were significantly lower in carcinomas than in LMP tumors, but that DNMT3B1/B2 RNA had significantly higher levels in carcinomas than in the LMP tumors (Table 2).

Table 2.

Relative DNMT mRNA levels in ovarian epithelial borderline cancers vs. carcinomasa

| LMP tumors | Carcinomas | P-valueb | |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNMT1 | 1.2 | 0.8 | 0.25 |

| DNMT2 | 1.4 | 0.6 | <0.005c |

| DNMT3A1c | 1.3 | 0.7 | <0.005c |

| DNMT3A2c | 1.1 | 0.9 | 0.64 |

| DNMT3A (all isoforms)c | 1.2 | 0.8 | 0.07 |

| DNMT3B1 | 1.1 | 1.0 | 0.34 |

| DNMT3B1/3B2 | 0.3 | 1.7 | 0.005c |

| DNMT3B3 | 0.9 | 1.1 | 0.35 |

| DNMT3B4 | 0.9 | 1.2 | 0.27 |

| DNMT3B5 | 0.6 | 1.5 | 0.29 |

| DNMT3B (all isoforms) | 0.9 | 1.1 | 0.42 |

| DNMT3L | 1.8e | 0.2e | 0.97e |

The mean reference gene-normalized DNMT RNA levels for 17 ovarian epithelial LMP tumors (borderline cancers) or 17 carcinomas are shown relative to the average expression level of all of these tumors.

The P-value for a significant difference between carcinomas and LMP tumors is given (Wilcoxon rank-sum test).

These RNAs showed statistically significant differences with the cut-point for significance set such that the overall rate of false discovery was 5%.

For clarity, we have used the term DNMT3A1 to denote the isoform initially referred to as DNMT3A (Chen et al., 2002). DNMT3A1 and DNMT3A2 isoforms have the same catalytic domains but differ in their N terminal domains. DNMT3A1 mRNA, the longer transcript, contains exons 1 through 6 and 8 through 24, whereas DNMT3A2 mRNA, the shorter transcript, contains two unique exons, 7α and 7ß, and exons 8 through 24. The reaction indicated by “all isoforms” covers exons 19 and 20, which are present in both DNMT3A isoforms.

Only two of the tumors showed appreciable RT-PCR product for DNMT3L.

Next, we looked for relationships between satellite or global DNA hypomethylation and DNMT RNA levels among the carcinomas and LMP tumors. Contrary to a previous report on hepatocellular carcinomas (Saito et al., 2002), we found no significant association between overexpression of the DNMT3B4 isoform RNA and Sat2 hypomethylation in ovarian carcinomas (P=0.77) or in the combined group of carcinomas and LMP tumors (P=0.55). None of the DNMT isoform mRNA levels were significantly associated with any of the hypomethylation variables (global or satellite hypomethylation) after adjustment for multiple comparisons in the carcinomas alone or in the combined group of carcinomas and LMP tumors. Contrary to a previous report on hepatocellular carcinomas (Saito et al., 2002), we found no significant association between overexpression of the DNMT3B4 isoform RNA and Sat2 hypomethylation in ovarian carcinomas (P=0.77) or in the combined group of carcinomas and LMP tumors (P=0.55). However, in the group of carcinomas plus LMP tumors, there were inverse associations that did not reach the level of significance when adjusted for multiple comparisons. These included DNMT1 RNA levels with Chr1 Sat2, Chr1 Satα, and global DNA hypomethylation (P=0.07, 0.007, and 0.06, respectively); DNMT2 RNA levels with Chr1 Sat2 hypomethylation (P=0.02); and DNMT3A2 RNA levels with Chr1 Satα hypomethylation (P=0.02). These associations may merit investigation in a larger study.

In the combined group of LMP tumors and ovarian carcinomas, we looked for associations between DNMT isoform mRNA levels and the 19 genes in Table 1 that exhibited malignancy-related hypermethylation. DNMT3B1/3B2 mRNA levels were directly associated only with methylation of CDH13 (P=0.01), MLH-M2B (P=0.002), SEZ6L (P=0.009) or MINT31-M1B (P=0.02). The only observed correlations of DNMT3A1 mRNA levels with gene hypermethylation were inverse associations with CDH13 (P=0.005) or PGR methylation (P=0.01). However, none of these associations was significant after adjusting for multiple comparisons. Significance after adjustment for multiple comparisons was observed for the direct association between MTHFR methylation and DNMT3B1/3B2 mRNA levels (P<0.0001) as well as the inverse association between MTHFR methylation and DNMT3A1 mRNA levels (P=0.0001). It is unclear how a decrease in RNA levels for DNMT3A1 might favor hypermethylation of certain genes. However, DNMT3A1 and DNMT3A2 differ in their non-catalytic N-terminal domains, and we noted above that there was significantly less DNMT3A1 RNA in carcinomas than in LMP tumors.

Finally, in the carcinoma group, we looked for associations between DNMT RNA isoforms levels and gene hypermethylation. We found a significant association between DNMT1 mRNA levels and LTB4R methylation after adjustment for multiple comparisons (Table 1). One other examined gene, MTHFR, displayed an association of DNA methylation with DNMT1 mRNA levels (P<0.01). Interestingly, LTB4R and MTHFR are the only loci that showed significant hypermethylation with the degree of malignancy in ovarian tumors after adjustment for multiple comparisons and also displayed considerable methylation in the normal tissue controls (Table 1). Although the associations of DNMT1 RNA levels and LTB4R and MTHFR methylation were not seen in the combined group of carcinomas and LMP tumors, a given DNMT enzyme isoform might be more involved in gene hypermethylation for one type of malignant transformation than for another. We also found an association of Alu repeat hypomethylation with low levels of DNMT1 RNA (P=0.03) just in the carcinoma group (Table 1).

Discussion

We rigorously analyzed the association of malignancy-linked DNA hypermethylation and hypomethylation using quantitative measures of hypermethylation at gene loci (MethyLight assay), global DNA hypomethylation (HPLC) and semi-quantitative data on satellite DNA hypomethylation (Southern blot/phosphoimager analysis) on a collection of ovarian epithelial tumor samples enriched for neoplastic cells. On the 60 studied tumors, 60 MethyLight reactions covering 55 gene loci were performed which resulted in approximately 3600 total methylation data points With adjustment for multiple comparisons, we first identified six gene regions (LTB4R, MTHFR, PGR, CDH13, CDH1, and IGSF4) whose hypermethylation was significantly associated with the degree of malignancy. Only CDH1 and CDH13 were previously shown to be abnormally methylated in ovarian cancers (Kawakami et al., 1999; Rathi et al., 2002; Widschwendter et al., 2004). In addition, both genes are hypermethylated in many other types of human cancers including lung and breast (Zochbauer-Muller et al., 2001), prostate (Isaacs et al., 1995), colon (Hibi et al., 2004) and thyroid (Graff et al., 1998). PGR is hypermethylated in breast (Lapidus et al., 1996) and endometrial cancers (Sasaki et al., 2003). Hypermethylation of IGSF4 was described in cervical (Li et al., 2005) and pancreatic (Jansen et al., 2002) cancers. MTHFR had not been previously shown to be hypermethylated in ovarian cancers, but it had been linked to ovarian carcinogenesis by loss of heterozygosity (Viel et al., 1997).

After demonstrating that satellite DNA hypomethylation and global DNA hypomethylation were also significantly related to the degree of malignancy in these tumors, we looked at interrelationships between hypermethylation and hypomethylation. A multiple regression analysis indicated that these types of hypomethylation and hypermethylation are not interdependent so that neither is likely to be the result or cause of the other. Instead, they share an occasional inverse correlation, as described below. Nonetheless, both hypermethylation and hypomethylation of DNA are linked to carcinogenesis and so may have some step(s) in common in the poorly understood pathways that lead to these divergent epigenetic changes (Nishiyama et al., 2005).

Our findings on the general independence of DNA hypomethylation and hypermethylation in different parts of the genome in ovarian cancer are consistent with the following less extensive analyses: LINE1 hypomethylation vs. GST1 hypermethylation in prostate carcinomas (Santourlidis et al., 1999); satellite and global DNA hypomethylation vs. gene hypermethylation in Wilms tumors (Ehrlich et al., 2002); cancer/testes antigen gene hypomethylation vs. gene hypermethylation in gastric cancers (Kaneda et al., 2004); and in vitro DNMT acceptor activity vs. gene hypermethylation in colon neoplasms (Bariol et al., 2003). In contrast to the separate relationship of the studied DNA hypermethylation and DNA hypomethylation to malignant potential in ovarian tumors, we found that all analyzed categories of satellite DNA hypomethylation were significantly related to each other and to global DNA hypomethylation. Therefore, global hypomethylation, which is frequent in diverse types of cancer (Ehrlich, 2002), might promote tumor formation or progression by encompassing satellite DNA or DNA repeats in general.

We observed one association of satellite DNA hypomethylation with gene hypermethylation in the carcinoma-only group but it was an inverse one. CDH13 was less likely to be hypermethylated (P=0.01) when there was extensive loss of Sat2 methylation. Similarly, we previously found a significant inverse association between CDH13 hypomethylation and Sat2 hypomethylation in a different, larger group of ovarian cancers (96 tumors) and in breast cancers (43 tumors; Widschwendter et al., 2004). These findings might reflect waves of DNA demethylation during carcinogenesis that could affect some CpG-rich regions and reverse their de novo methylation (Cheng et al., 2001; Taniguchi et al., 2003).

Despite many investigations, it is still unclear to what extent altered DNMT levels are involved in cancer-linked hypermethylation or hypomethylation. Although no single change in DNMT levels could explain both cancer-linked increases of DNA methylation in some portions of the genome and decreases in others, differential changes in specific DNMT isoforms might be involved if they have sufficient regional specificity. At least some compartmentalization of human DNMT specificities can be inferred from the ICF syndrome in which a major deficiency in DNMT3B activity (Gowher & Jeltsch, 2002; Hansen et al., 1999; Okano et al., 1999) cannot be compensated by the other DNMTs and results in selective hypomethylation of certain portions of the genome, notably long regions with tandem repeats, including Sat2 (Ehrlich, 2003; Jeanpierre et al., 1993; Kondo et al., 2000). By comparing DNMT RNA levels and differential DNA methylation in cancers of the same type, we avoided the problems implicit in normal tissue-to-cancer comparisons for such cell cycle-dependent RNAs. The most notable associations between RNA levels for ten DNMT isoforms with gene hypermethylation in cancer were those between DNMT1 RNA levels and LTB4R hypermethylation (P=0.0005) or MTHFR hypermethylation (P=0.002). LTB4R and MTHFR are the only two loci with appreciable DNA methylation even in the normal tissue controls as well as significant hypermethylation related to the degree of malignancy. Therefore, increased DNMT1 activity might be involved in malignancy-related increases in methylation of genes that have appreciable methylation in normal tissues. Caveats in this analysis are that the transient changes in DNMT RNA levels would be missed and that the analysis was only at the level of RNA.

A recent study showed that DNMT1 protein levels were elevated in human breast cancer cells due to increased stability, while the DNMT1 mRNA levels were unchanged (Agoston et al., 2005). However, quantitative analysis of individual protein splice variants, such as those of DNMT3B, is difficult due to poor specificity and sensitivities in recognizing these isoforms, which are expressed at very low levels. Moreover, the detection of DNMT proteins in human cancers is insufficient to provide information regarding the catalytic activity of each isoform. We utilized highly sensitive, quantitative, real-time RT-PCR assays which are specific for each DNMT mRNA isoform.

No DNA hypomethylation variables were significantly associated with DNMT RNA levels after adjustment for multiple comparisons. From a study of hepatocellular carcinomas, it was proposed that Sat2 hypomethylation in cancer is due to a reported overproduction of an alternatively spliced form of DNMT3B RNA (DNMT3B4) that is missing part of the sequence encoding the catalytic domain (Saito et al., 2002). Because of the above-mentioned Sat2 hypomethylation when DNMT3B is mutationally inactivated in the ICF syndrome, it was hypothesized that there is an excess of DNMT3B4 protein in cancers that inhibits catalytically active variants of DNMT3B. However, in the ovarian carcinomas and LMP tumors, we saw no correlation between cancer-associated Sat2 hypomethylation and increased levels of DNMT3B4 RNA.

Our data are consistent with the hypothesis that the very frequent satellite DNA hypomethylation and global DNA hypomethylation in cancer favor carcinogenesis and are not just an epiphenomenon linked to gene hypermethylation and silencing. Cancer-linked DNA hypomethylation may have an important role in increasing cancer-predisposing chromosome rearrangements (Kokalj-Vokac et al., 1993; Hernandez et al., 1997; Eden et al., 2003), although the frequency of this hypomethylation in satellite DNA is much greater than that of satellite DNA rearrangements and is not related to aneuploidy (Ehrlich et al., 2003). Satellite DNA hypomethylation might have an indirect effect on gene expression that favors tumorigenesis, e.g., by influencing the sequestration of DNA-binding proteins in highly repeated DNA regions. Alternatively, cancer-associated DNA hypomethylation might greatly overshoot critical promoter targets but often include transcription regulatory regions, despite the finding that promoter hypomethylation in cancer appears to be much less frequent than promoter hypermethylation (Ehrlich, 2002). Our recent demonstration that satellite DNA hypomethylation is a superior and independent marker of poor prognosis in ovarian cancer patients undergoing optimal cytoreductive surgery (Widschwendter et al., 2004) highlights the importance of more studies on cancer-linked DNA hypomethylation to elucidate why hypomethylation, as well as hypermethylation, is so frequent in cancer and to carefully consider diagnostic, prognostic, and therapeutic applications of cancer epigenetics.

Materials and methods

Tissue samples and DNA isolation

With IRB approval, tumor samples were obtained from patients who had not been treated with chemotherapy prior to surgery. For the cystadenomas, a frozen section was used to determine from which side of the cyst to scrape off the neoplastic cells to give a population of cells with close to 100% tumor cells. For the LMP tumors and carcinomas, frozen sections were used to identify areas where tumor cells were concentrated and dissect those areas for nucleic acid isolation. All of the carcinomas and most of the cystadenomas and LMP tumors were different from those described in our previous study (Qu et al., 1999a) but overlapped those in a study of methylation changes in another DNA repeat (Nishiyama et al., 2005). The cystadenomas and LMP tumors were about 50% serous and 50% mucinous. The carcinomas were about 60% serous, 30% endometroid, and 10% mucinous. The control tissues were autopsy samples from two trauma victims. DNA was purified from quick-frozen samples by standard methods (Ehrlich et al., 1982).

Quantitative analysis of methylation levels in CpG-rich regions of the genome

The bisulfite modification-based MethyLight assay was used to quantitate methylation at CpG-rich regions as previously described (Eads et al., 2001; Ehrlich et al., 2002) with the primers and probes indicated in Supplementary Table A. Generally, amplification with these probes depends upon full methylation at the probe and primer positions in the genomic DNA. The percentage of fully methylated molecules at a specific CpG-rich gene region was calculated by dividing the MethyLight signal for the given gene by that for ACTB (amplified with primers from non-CpG-containing sequences) in each sample DNA and then dividing that ratio by the analogous GENE:ACTB ratio for in vitro-methylated sperm DNA and multiplying by 100. The value obtained is designated as the percent of methylated reference (PMR; Eads et al., 2001). PMR values higher than 100 may be obtained for technical reasons, such as, incomplete in vitro methylation of the sperm sample or aberrant gene dosage in some cancers.

Satellite DNA methylation analysis

Southern blot analysis with a CpG methylation-sensitive restriction endonuclease, BstBI, was done to assess the extent of hypomethylation in satellite DNA under high-stringency (Chr1 Sat2 and Chr1 Satα) or low-stringency (Satα in the centromeres throughout the genome) conditions with quantitation by phosphorimager analysis and band patterns as described previously (Widschwendter et al., 2004). Hypomethylation scores were 0, 1, 2, 3, or 4; 0 indicates similar methylation as for the 3–5 diverse somatic postnatal control tissue DNAs included in each blot; 4 represents the most extreme hypomethylation, like that of sperm DNA, also included in each blot.

Quantitation of global m5C levels in the genome and DNMT RNA analysis

The overall DNA m5C content was determined by high performance liquid chromatography on heat-denatured DNA digested to nucleosides with an average of 2% relative standard deviation between triplicates or duplicates (Ehrlich et al., 2002). To quantitate DNMT RNA isoforms, real-time RT-PCR on total RNA (Eads et al., 1999) was done with the primers and probe oligonucleotides listed in Supplementary Table B. The expression values for each DNMT transcript were obtained by first separately normalizing their raw expression values to those of PCNA and HIS2H4. These PCNA-normalized expression values were then divided by the average PCNA-normalized expression of each DNMT for all of the samples. The analogous procedure was done for the HIS2H4-normalized expression values. These two normalized ratios for each sample were then averaged to generate the final expression values for each transcript in each of the sample, thereby normalizing the level of cell cycle-dependent expression of DNMT genes to that of cell cycle-dependent reference standards.

Supplementary Table B.

Real-Time RT-PCR Reaction Details

| Gene name and mRNA isoforms recognized | Reaction ID | mRNA accession number | Amplicon location | Forward primer sequence | Reverse primer sequence | Probe sequence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DNMT1 | DNMT1-R1 | NM_001379 | Catalytic domain of DNMT1 (exons 33/34) | GGTTCTTCCTCCTGGAGAATGTC | GGGCCACGCCGTACTG | 6FAM-CCTTCAAGCGCTCCATGGTCCTGAA-TAMRA |

| DNMT2 | DNMT2-R1 | NM_004412 | Exons 7/8 | AAGGCTACGATATTTTCTTATTGCAAA | GGAACTCCATCAGTACCTGACCA | 6FAM-CTTCAGTCAGAGCCATTACCCTTTCAAGCC-TAMRA |

| DNMT3A1a | DNMT3A-R3 | AF331856b | Exon 6/8 | GGGACCCCTACTACATCAGCAA | TTCTCAGCCTCCCTTTTCCAG | 6FAM-TGCCAGCCACTCGTCCCGCTT-TAMRA |

| DNMT3A2a | DNMT3A-R2 | AF480163b | Exons 7alpha to 7 beta | GGGCTGCACCTGGCC | GTCTTTCAGGCTACGATCCACG | 6FAM-ATTCCTTCTCACAACCCGCTCCAGG-TAMRA |

| DNMT3A (all isoforms)a | DNMT3A-R1 | AF331856b | Catalytic domain of all DNMT3A isoforms (exons 19/20) | CAATGACCTCTCCATCGTCAAC | CATGCAGGAGGCGGTAGAA | 6FAM-AGCCGGCCAGTGCCCTCGTAG-TAMRA |

| DNMT3B1 | DNMT3B-R6 | NM_006892 | Exon 11 | CTCGAAGACGCACAGCTGAC | TTTGTCTTGAGGCGCTTGG | 6FAM-CCACCTCTGACTACTGCCCCGCA-TAMRA |

| DNMT3B1 and 3B2 | DNMT3B-R2 | NM_006892 | Exons 21/22 | CTTGGAATACAATAGGATAGCCAAGTTA | AAGTTGGTTTTT CCCCTGTTTG | 6FAM-AGAAAGTACAGACAATAACCACCAAGTCGAACTCG-T |

| DNMT3B3 | DNMT3B-R3 | AF156487 | Exons 20/23 | CAGGGCCCGATACTTCTGG | CGTCTGTGTAGTGCACAGGAAAG | 6FAM-CAACCTACCCGGGATGAACAGGATCTTT-TAMRA |

| DNMT3B4 | DNMT3B-R4 | AF129268 | Exons 20/22 | AGGGCCCGATACTTCTGGG | CCCCTGTTTGATCGAGTTCG | 6FAM-TGTCTGTACTTTCTTTAACTGTTCATCCCGGGT-TAMRA |

| DNMT3B5 | DNMT3B-R5 | AF129269 | Exons 21/23 | GGATGAACAGGCCCGTGA | GGCTATCCTATTGTATTCCAAGCAG | 6FAM-CCTGCAGCTCGAGTTTATCATTCTTTGATGCT-TAMRA |

| DNMT3B (all isoforms)c | DNMT3B-R1 | NM_006892 | Catalytic domain of all DNMT3B isoforms (exons 19/20) | CCATGAAGGTTGGCGACAA | TGGCATCAATCATCACTGGATT | 6FAM-CACTCCAGGAACCGTGAGATGTCCCT-TAMRA |

| DNMT3L | DNMT3L-R1 | NM_013369 | Exons 2/3 | GGGACAACTGAAGCATGTGGT | AAGATCGAAGGGTCCCCACT | 6FAM-CCACATCCTTCCTCACTGTGTCTGTGACAT-TAMRA |

| PCNA (Control) | PCNA-R1 | NM_002592 | Exon 5 | GTGCAAAAGACGGAGTGAAATTT | ATCGACATTACTTGTCTGTGACAATTTA | 6FAM-TGTTTCCATTTCCAAGTTCTCCACTTGCAG-TAMRA |

| HIST2H4 (Control) | HIST2H4-R1 | CR542172 | Exon 1 | TTCGGGACGCAGTCACCTA | AGCGCGTACACCACATCCAT | 6FAM-CACGCCAAGCGCAAGACCGTC-TAMRA |

There are two DNMT3A isoforms: DNMT3A and DNMT3A2 (Chen 2002 JBC 277,38746). For clarity, we have used the term DNMT3A1 to denote the isoform initially referred to as DNMT3A.

Both DNMT3A1 and DNMT3A2 have the same catalytic domains but differ in their N terminal domains.

DNMT3A1 mRNA, the longer transcript, contains exons 1 through 6 and 8 through 24.

DNMT3A2 mRNA, the shorter transcript contains two unique exons, 7α and 7ß, as well as exons 8 through 24.

The reaction indicated by “all isoforms” covers exons 19 and 20, which are present in both DNMT3A isoforms.

The exon numbering for the DNMT3A mRNA transcripts is from 1 to 24. In the DNMT3A mRNA clone with GenBank accession number AF331856, exons 7α and 7ß are absent, so exon 6 is followed by exon 8.

In the DNMT3A2 mRNA clone GenBank accession number AF480163, the exon numbering starts with the two exons 7 (α and ß) followed by exons 8 through 24.

This PCR amplicon covers exons 19 and 20 which are present in all DNMT3B isoforms, and thus will represent a measure of total DNMT3B expression.

Statistical analysis.

We used the non-parametric Wilcoxon rank-sum test (Hollander & Wolfe, 1999) to determine if increasing degree of malignancy (from cystadenoma to LMP to carcinoma, one degree of freedom) is associated with extents of gene methylation (PMR values). It was used to examine the relationships in carcinomas only and in carcinomas plus LMP tumors between two levels (scores of 0–1 vs. 2–4) of satellite DNA hypomethylation and DNMT RNA levels or PMR values for loci in Table 1. We used the Mantel-Haenszel chi-square test with one degree of freedom (Hollander & Wolfe, 1999) to determine if increasing degree of malignancy is associated with satellite or global DNA hypomethylation. The stepwise linear regression method (Draper & Smith, 1981) was used to determine the minimal sets of independent predictors of degree of malignancy within and between studied subsets of methylation variables, with the P-values associated with F to enter and F to remove both set at 5%. The Spearman rank correlation coefficient (Hollander & Wolfe, 1999) was used to examine associations between PMR values and global DNA hypomethylation or DNMT RNA levels. To correct for the problem of multiple comparisons, we used the method of Benjamini and Liu (Benjamini et al., 2001) with the rate of false discovery set at 5%. SAS version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and STATA version 8.0 (STATA Company, College Stations, TX) were used to perform the calculations.

Acknowledgments

We thank Kazuko Arakawa for her excellent assistance in statistical computing. This work was supported in part by NIH grants CA81506 (to ME), CA96958 (to PWL), and PO1CA46589 and PO1 CA70972 (to EF).

References

- Agoston AT, Argani P, Yegnasubramanian S, De Marzo AM, Ansari-Lari MA, Hicks JL, Davidson NE, Nelson WG. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:18302–18310. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501675200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahluwalia A, Yan P, Hurteau JA, Bigsby RM, Jung SH, Huang TH, Nephew KP. Gynecol Oncol. 2001;82:261–268. doi: 10.1006/gyno.2001.6291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bariol C, Suter C, Cheong K, Ku SL, Meagher A, Hawkins N, Ward R. Am J Pathol. 2003;162:1361–1371. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63932-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y, Drai D, Elmer G, Kafkafi N, Golani I. Behav Brain Res. 2001;125:279–284. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(01)00297-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broday L, Lee YW, Costa M. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:3198–3204. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.4.3198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chedin F, Lieber MR, Hsieh CL. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:16916–16921. doi: 10.1073/pnas.262443999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen B, Ueda Y, Xie S, Li E. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:38746–38754. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205312200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng CW, Wu PE, Yu JC, Huang CS, Yue CT, Wu CW, Shen CY. Oncogene. 2001;20:3814–3823. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Draper, N.R. & Smith, H. Applied Regression Analysis John Wiley and Sons: New York, N.Y.

- Dubeau L. Gynecol Oncol. 1999;72:437–442. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1998.5275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eads CA, Danenberg KD, Kawakami K, Saltz LB, Blake C, Shibata D, Danenberg PV, Laird PW. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:E32. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.8.e32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eads CA, Danenberg KD, Kawakami K, Saltz LB, Danenberg PV, Laird PW. Cancer Res. 1999;59:2302–2306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eads CA, Lord RV, Wickramasinghe K, Long TI, Kurumboor SK, Bernstein L, Peters JH, DeMeester SR, DeMeester TR, Skinner KA, Laird PW. Cancer Res. 2001;61:3410–3418. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eden A, Gaudet F, Waghmare A, Jaenisch R. Science. 2003;300:455. doi: 10.1126/science.1083557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrlich M. Oncogene. 2002;21:5400–5413. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrlich M, Gama-Sosa M, Huang LH, Midgett RM, Kuo KC, McCune RA, Gehrke C. Nucleic Acids Res. 1982;10:2709–2721. doi: 10.1093/nar/10.8.2709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrlich M, Hopkins N, Jiang G, Dome JS, Yu MS, Woods CB, Tomlinson GE, Chintagumpala M, Champagne M, Diller L, Parham DM, Sawyer J. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2003;141:97–105. doi: 10.1016/s0165-4608(02)00668-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrlich M, Jiang G, Fiala ES, Dome JS, Yu MS, Long TI, Youn B, Sohn OS, Widschwendter M, Tomlinson GE, Chintagumpala M, Champagne M, Parham DM, Liang G, Malik K, Laird PW. Oncogene. 2002;21:6694–6702. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- el-Deiry WS, Nelkin BD, Celano P, Yen RW, Falco JP, Hamilton SR, Baylin SB. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:3470–3474. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.8.3470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg AP, Cui H, Ohlsson R. Semin Cancer Biol. 2002;12:389–398. doi: 10.1016/s1044-579x(02)00059-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg AP, Vogelstein B. Nature. 1983;301:89–92. doi: 10.1038/301089a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gama-Sosa MA, Slagel VA, Trewyn RW, Oxenhandler R, Kuo KC, Gehrke CW, Ehrlich M. Nucleic Acids Res. 1983;11:6883–6894. doi: 10.1093/nar/11.19.6883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gowher H, Jeltsch A. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:20409–20414. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202148200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graff JR, Greenberg VE, Herman JG, Westra WH, Boghaert ER, Ain KB, Saji M, Zeiger MA, Zimmer SG, Baylin SB. Cancer Res. 1998;58:2063–2066. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grunau C, Sanchez C, Ehrlich M, van der Bruggen P, Hindermann W, Rodriguez C, Krieger S, De Sario A. Genes Chrom Cancer. 2005;43:11–24. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen RS, Wijmenga C, Luo P, Stanek AM, Canfield TK, Weemaes CM, Gartler SM. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:14412–14417. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.25.14412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermann A, Schmitt S, Jeltsch A. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:31717–31721. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305448200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez R, Frady A, Zhang XY, Varela M, Ehrlich M. Cytogenet Cell Genet. 1997;76:196–201. doi: 10.1159/000134548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibi K, Nakayama H, Kodera Y, Ito K, Akiyama S, Nakao A. Br J Cancer. 2004;90:1030–1033. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollander, M. & Wolfe, D.A. Nonparametric Statistical Methods, Second Edition edn. John Wiley and Sons: New York.

- Isaacs WB, Bova GS, Morton RA, Bussemakers MJ, Brooks JD, Ewing CM. Cancer Surv. 1995;23:19–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Issa, J.P. (2000). DNA alterations in cancer: genetic and epigenetic alterations Ehrlich, M. (ed.). Eaton Publishing: Natick, pp 311–322.

- Jackson K, Yu M, Arakawa K, Fiala E, Youn B, Fiegl H, Muller-Holzner E, Widschwendter M, Ehrlich M. Cancer Biol Ther. 2004;3:1225–1231. doi: 10.4161/cbt.3.12.1222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsen SE, Meyerowitz EM. Science. 1997;277:1100–1103. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5329.1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansen M, Fukushima N, Rosty C, Walter K, Altink R, Heek TV, Hruban R, Offerhaus JG, Goggins M. Cancer Biol Ther. 2002;1:293–6. doi: 10.4161/cbt.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeanpierre M, Turleau C, Aurias A, Prieur M, Ledeist F, Fischer A, Viegas-Pequignot E. Hum Mol Genet. 1993;2:731–735. doi: 10.1093/hmg/2.6.731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones PA, Baylin SB. Nat Rev Genet. 2002;3:415–428. doi: 10.1038/nrg816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaneda A, Tsukamoto T, Takamura-Enya T, Watanabe N, Kaminishi M, Sugimura T, Tatematsu M, Ushijima T. Cancer Sci. 2004;95:58–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2004.tb03171.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawakami M, Staub J, Cliby W, Hartmann L, Smith DI, Shridhar V. Int J Oncol. 1999;15:715–720. doi: 10.3892/ijo.15.4.715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura F, Seifert HH, Florl AR, Santourlidis S, Steinhoff C, Swiatkowski S, Mahotka C, Gerharz CD, Schulz WA. Int J Cancer. 2003;104:568–578. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kokalj-Vokac N, Almeida A, Viegas-Pequignot E, Jeanpierre M, Malfoy B, Dutrillaux B. Cytogenet Cell Genet. 1993;63:11–15. doi: 10.1159/000133492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondo T, Comenge Y, Bobek MP, Kuick R, Lamb B, Zhu X, Narayan A, Bourc’his D, Viegas-Pequinot E, Ehrlich M, Hanash S. Hum Mol Gen. 2000;9:597–604. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.4.597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapidus RG, Ferguson AT, Ottaviano YL, Parl FF, Smith HS, Weitzman SA, Baylin SB, Issa JP, Davidson NE. Clin Cancer Res. 1996;2:805–810. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee PJ, Washer LL, Law DJ, Boland CR, Horon IL, Feinberg AP. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:10366–10370. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.19.10366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Zhang Z, Bidder M, Funk MC, Nguyen L, Goodfellow PJ, Rader JS. Gynecol Oncol. 2005;96:150–158. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2004.08.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCluskey LL, Dubeau L. Curr Opin Oncol. 1997;9:465–470. doi: 10.1097/00001622-199709050-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narayan A, Ji W, Zhang XY, Marrogi A, Graff JR, Baylin SB, Ehrlich M. Int J Cancer. 1998;77:833–838. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19980911)77:6<833::aid-ijc6>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishiyama R, Qi L, Tsumagari K, Dubeau L, Weissbecker K, Champagne M, Sikka S, Nagai H, Ehrlich M. Cancer Biol Ther. 2005;4:440–448. doi: 10.4161/cbt.4.4.1622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okada H, Kimura MT, Tan D, Fujiwara K, Igarashi J, Makuuchi M, Hui AM, Tsurumaru M, Nagase H. Int J Oncol. 2005;26:369–377. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okano M, Bell DW, Haber DA, Li E. Cell. 1999;98:247–257. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81656-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pogribny IP, Miller BJ, James SJ. Cancer Lett. 1997;115:31–38. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(97)04708-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu G, Dubeau L, Narayan A, Yu M, Ehrlich M. Mut Res. 1999a;423:91–101. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(98)00229-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu G, Ehrlich M. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:2332–2338. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.11.2332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu G, Grundy PE, Narayan A, Ehrlich M. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 1999b;109:34–39. doi: 10.1016/s0165-4608(98)00143-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rathi A, Virmani AK, Schorge JO, Elias KJ, Maruyama R, Minna JD, Mok SC, Girard L, Fishman DA, Gazdar AF. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8:3324–3331. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson KD. Oncogene. 2001;20:3139–55. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson KD, Uzvolgyi E, Liang G, Talmadge C, Sumegi J, Gonzales FA, Jones PA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:2291–2298. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.11.2291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito Y, Kanai Y, Sakamoto M, Saito H, Ishii H, Hirohashi S. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:10060–10065. doi: 10.1073/pnas.152121799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santourlidis S, Florl A, Ackermann R, Wirtz HC, Schulz WA. Prostate. 1999;39:166–174. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0045(19990515)39:3<166::aid-pros4>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki M, Kaneuchi M, Fujimoto S, Tanaka Y, Dahiya R. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2003;202:201–207. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(03)00084-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strathdee G, Davies BR, Vass JK, Siddiqui N, Brown R. Carcinogenesis. 2004;25:693–701. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgh066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang LY, Reddy MN, Rasheva V, Lee TL, Lin MJ, Hung MS, Shen CK. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:33613–33616. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C300255200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taniguchi T, Tischkowitz M, Ameziane N, Hodgson SV, Mathew CG, Joenje H, Mok SC, D’Andrea AD. Nat Med. 2003;9:568–574. doi: 10.1038/nm852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toyooka KO, Toyooka S, Virmani AK, Sathyanarayana UG, Euhus DM, Gilcrease M, Minna JD, Gazdar AF. Cancer Res. 2001;61:4556–4560. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei SH, Chen CM, Strathdee G, Harnsomburana J, Shyu CR, Rahmatpanah F, Shi H, Ng SW, Yan PS, Nephew KP, Brown R, Huang TH. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8:2246–2252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisenberger DJ, Velicescu M, Cheng JC, Gonzales FA, Liang G, Jones PA. Mol Cancer Res. 2004;2:62–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widschwendter M, Jiang G, Woods C, Muller HM, Fiegl H, Goebel G, Marth C, Holzner EM, Zeimet AG, Laird PW, Ehrlich M. Cancer Res. 2004;64:4472–4480. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng J, Benedict WF, Xu HJ, Hu SX, Kim TM, Velicescu M, Wan M, Cofer KF, Dubeau L. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1995;87:1146–1153. doi: 10.1093/jnci/87.15.1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zochbauer-Muller S, Fong KM, Virmani AK, Geradts J, Gazdar AF, Minna JD. Cancer Res. 2001;61:249–255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]