Abstract

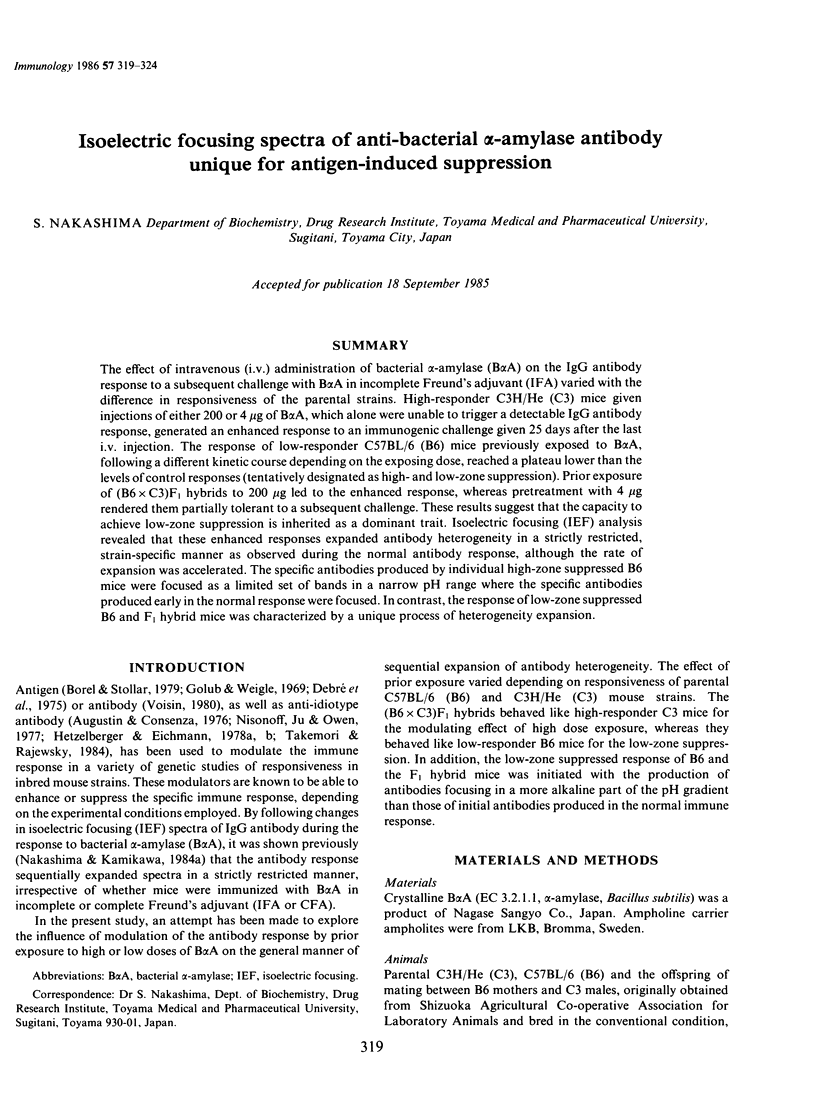

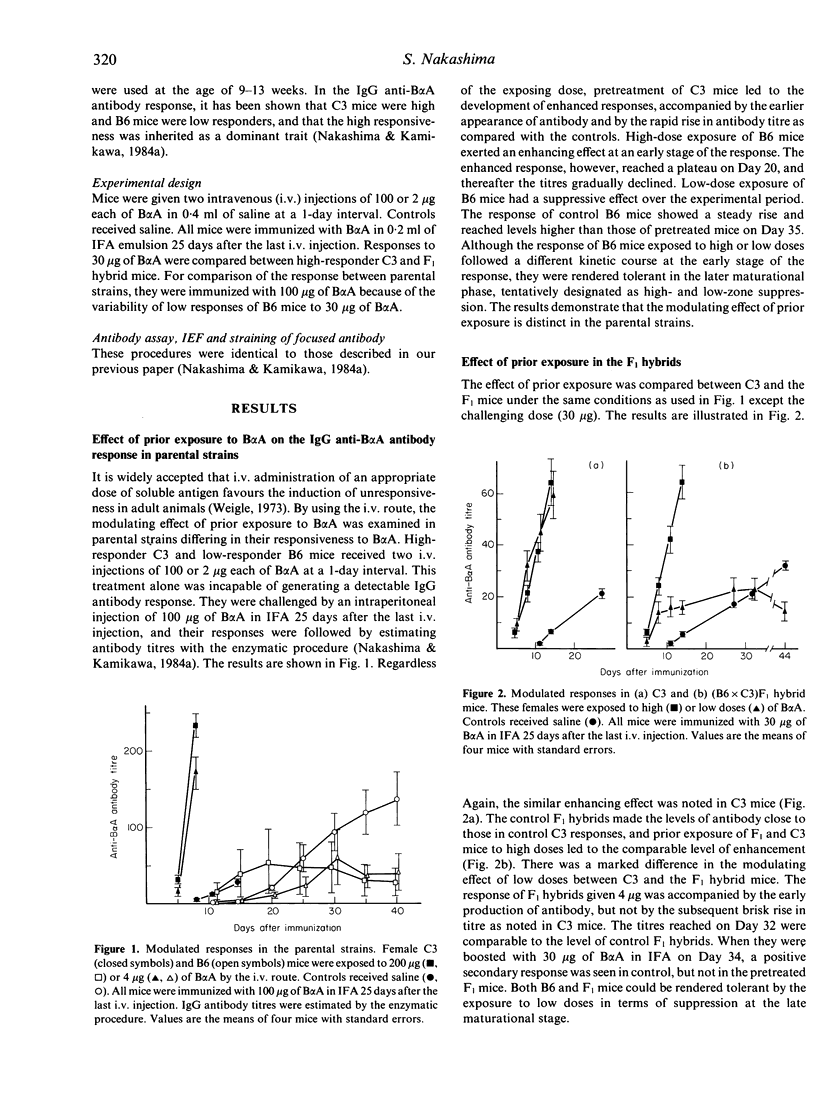

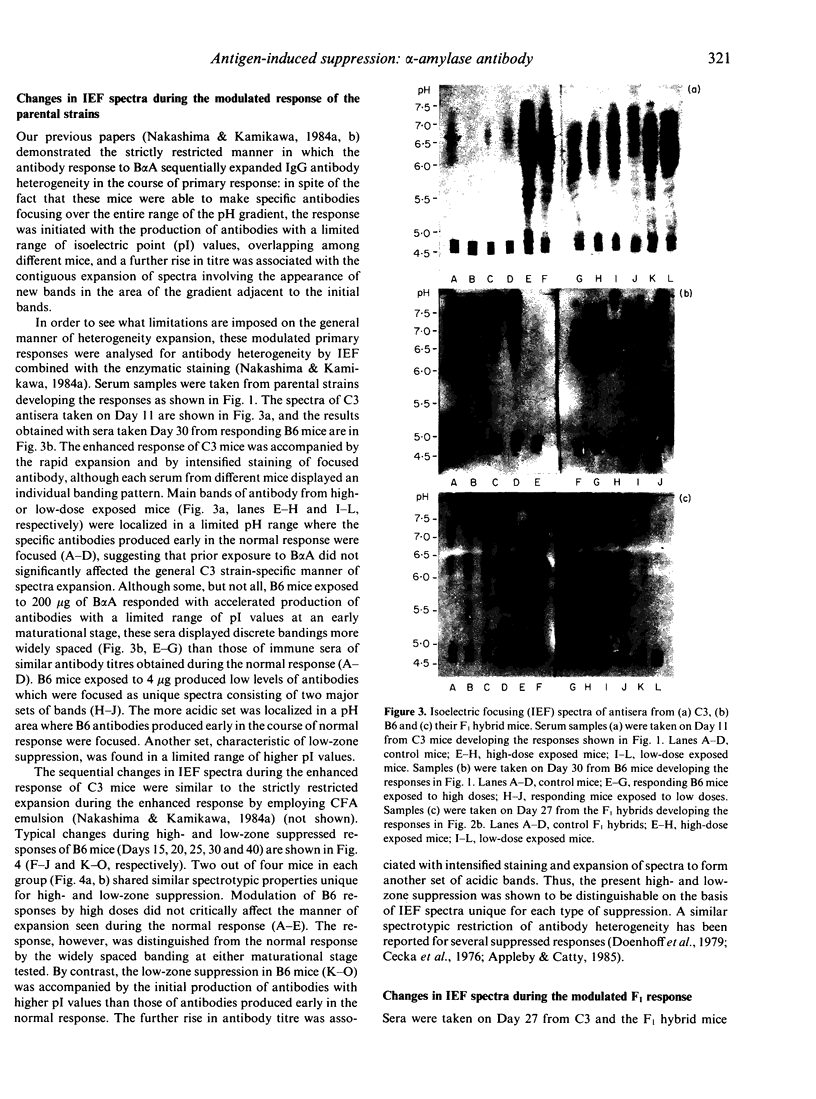

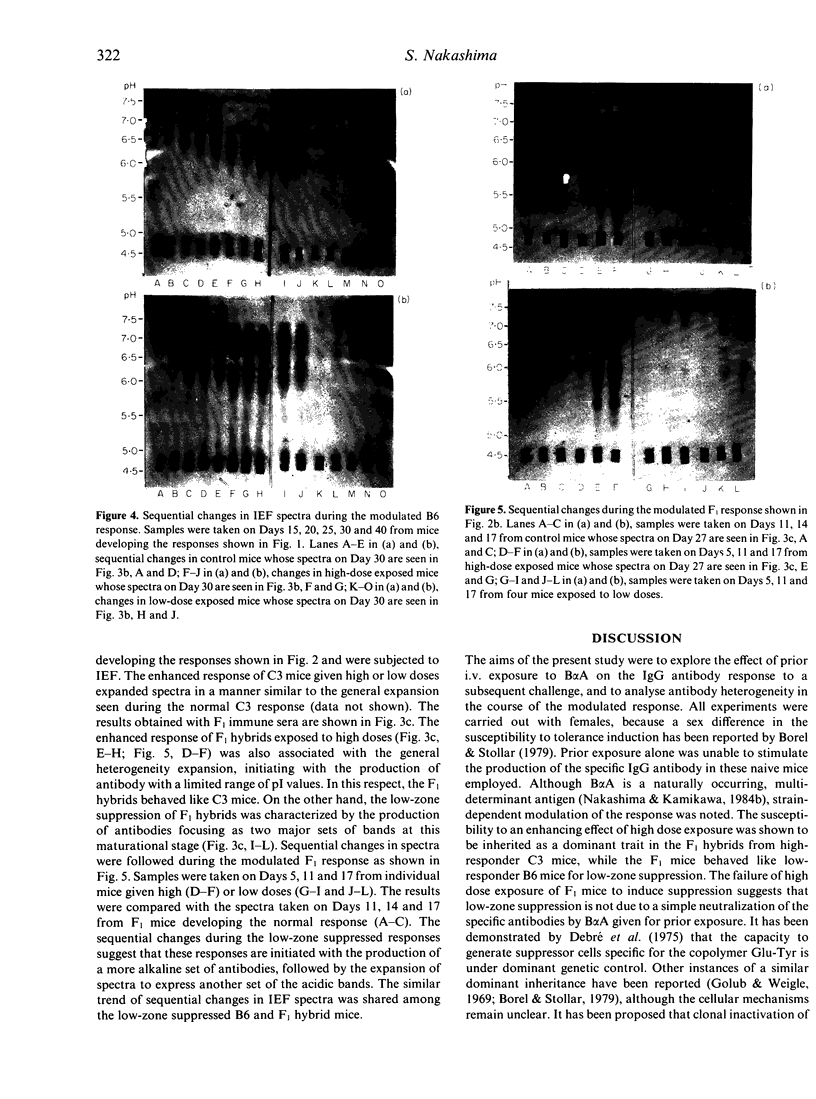

The effect of intravenous (i.v.) administration of bacterial alpha-amylase (B alpha A) on the IgG antibody response to a subsequent challenge with B alpha A in incomplete Freund's adjuvant (IFA) varied with the difference in responsiveness of the parental strains. High-responder C3H/He (C3) mice given injections of either 200 or 4 micrograms of B alpha A, which alone were unable to trigger a detectable IgG antibody response, generated an enhanced response to an immunogenic challenge given 25 days after the last i.v. injection. The response of low-responder C57BL/6 (B6) mice previously exposed to B alpha A, following a different kinetic course depending on the exposing dose, reached a plateau lower than the levels of control responses (tentatively designated as high- and low-zone suppression). Prior exposure of (B6 X C3)F1 hybrids to 200 micrograms led to the enhanced response, whereas pretreatment with 4 micrograms rendered them partially tolerant to a subsequent challenge. These results suggest that the capacity to achieve low-zone suppression is inherited as a dominant trait. Isoelectric focusing (IEF) analysis revealed that these enhanced responses expanded antibody heterogeneity in a strictly restricted, strain-specific manner as observed during the normal antibody response, although the rate of expansion was accelerated. The specific antibodies produced by individual high-zone suppressed B6 mice were focused as a limited set of bands in a narrow pH range where the specific antibodies produced early in the normal response were focused. In contrast, the response of low-zone suppressed B6 and F1 hybrid mice was characterized by a unique process of heterogeneity expansion.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Appleby P., Catty D. Quantitative and spectrotypic analysis of paternal IgG2a expression in normal and allotype-suppressed mice. Immunology. 1985 Mar;54(3):429–437. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Augustin A., Cosenza H. Expression of new idiotypes following neonatal idiotypic suppression of a dominant clone. Eur J Immunol. 1976 Jul;6(7):497–501. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830060710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Awdeh Z. L., Williamson A. R., Askonas B. A. One cell-one immunoglobulin. Origin of limited heterogeneity of myeloma proteins. Biochem J. 1970 Jan;116(2):241–248. doi: 10.1042/bj1160241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borel Y., Stollar B. D. Strain and sex dependence of carrier-determined immunologic tolerance to guanosine. Eur J Immunol. 1979 Feb;9(2):166–171. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830090214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cambier J. C., Kettman J. R., Vitetta E. S., Uhr J. W. Differential susceptibility of neonatal and adult murine spleen cells to in vitro induction of B-cell tolerance. J Exp Med. 1976 Jul 1;144(1):293–297. doi: 10.1084/jem.144.1.293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cecka J. M., Stratton J. A., Miller A., Sercarz E. Structural aspects of immune recognition of lysozymes. III. T cell specificity restriction and its consequences for antibody specificity. Eur J Immunol. 1976 Sep;6(9):639–646. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830060909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debré P., Kapp J. A., Dorf M. E., Benacerraf B. Genetic control of specific immune suppression. II. H-2-linked dominant genetic control of immune suppression by the random copolymer L-glutamic acid50-L-tyrosine50 (GT). J Exp Med. 1975 Dec 1;142(6):1447–1454. doi: 10.1084/jem.142.6.1447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falkoff R., Kettman J. Differential stimulation of precursor cells and carrier-specific thymus-derived cell activity in the in vivo reponse to heterologous erythrocytes in mice. J Immunol. 1972 Jan;108(1):54–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Germain R. N., Ju S. T., Kipps T. J., Benacerraf B., Dorf M. E. Shared idiotypic determinants on antibodies and T-cell-derived suppressor factor specific for the random terpolymer L-glutamic acid60-L-alanine30-L-tyrosine10. J Exp Med. 1979 Mar 1;149(3):613–622. doi: 10.1084/jem.149.3.613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gershon R. K., Eardley D. D., Durum S., Green D. R., Shen F. W., Yamauchi K., Cantor H., Murphy D. B. Contrasuppression. A novel immunoregulatory activity. J Exp Med. 1981 Jun 1;153(6):1533–1546. doi: 10.1084/jem.153.6.1533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golub E. S., Weigle W. O. Studies on the induction of immunologic unresponsiveness. 3. Antigen form and mouse strain variation. J Immunol. 1969 Feb;102(2):389–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene M. I., Nelles M. J., Sy M. S., Nisonoff A. Regulation of immunity to the azobenzenearsonate hapten. Adv Immunol. 1982;32:253–300. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60723-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hetzelberger D., Eichmann K. Idiotype suppression. III. Induction of unresponsiveness to sensitization with anti-idiotypic antibody: identification of the cell types tolerized in high zone and in low zone, suppressor cell-mediated, idiotype suppression. Eur J Immunol. 1978 Dec;8(12):839–846. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830081204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hetzelberger D., Eichmann K. Recognition of idiotypes in lymphocyte interactions. I. Idiotypic selectivity in the cooperation between T and B lymphocytes. Eur J Immunol. 1978 Dec;8(12):846–852. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830081205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loblay R. H., Fazekas de St Groth B., Pritchard-Briscoe H., Basten A. Suppressor T cell memory. II. The role of memory suppressor T cells in tolerance to human gamma globulin. J Exp Med. 1983 Mar 1;157(3):957–973. doi: 10.1084/jem.157.3.957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukić M. L., Cowing C., Leskowitz S. Strain differences in ease of tolerance induction to bovine gamma-globulin: dependence on macrophage function. J Immunol. 1975 Jan;114(1 Pt 2):503–506. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakashima S., Kamikawa H. Accelerated expansion of antibody heterogeneity by complete Freund's adjuvant during the response to bacterial alpha-amylase. Immunology. 1984 Dec;53(4):837–845. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakashima S., Kamikawa H. Sequential expansion of antibody heterogeneity during the response to bacterial alpha-amylase. J Biochem. 1984 Jul;96(1):223–228. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a134816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nisonoff A., Ju S. T., Owen F. L. Studies of structure and immunosuppression of cross-reactive idiotype in strain A mice. Immunol Rev. 1977;34:89–118. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1977.tb00369.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nossal G. J., Pike B. L. Evidence for the clonal abortion theory of B-lymphocyte tolerance. J Exp Med. 1975 Apr 1;141(4):904–917. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slack J., Der-Balian G. P., Nahm M., Davie J. M. Subclass restriction of murine antibodies. II. The IgG plaque-forming cell response to thymus-independent type 1 and type 2 antigens in normal mice and mice expressing an X-linked immunodeficiency. J Exp Med. 1980 Apr 1;151(4):853–862. doi: 10.1084/jem.151.4.853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tada T., Okumura K. The role of antigen-specific T cell factors in the immune response. Adv Immunol. 1979;28:1–87. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60799-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takemori T., Rajewsky K. Specificity, duration and mechanism of idiotype suppression induced by neonatal injection of monoclonal anti-idiotope antibodies into mice. Eur J Immunol. 1984 Jul;14(7):656–667. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830140714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takemori T., Tada T. Selective roles of thymus-derived lymphocytes in the antibody response. II. Preferential suppression of high-affinity antibody-forming cells by carrier-primed suppressor T cells. J Exp Med. 1974 Jul 1;140(1):253–266. doi: 10.1084/jem.140.1.253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas D. B., Kennedy M. W. Feedback control of the secondary antibody response. I. A suppressor, suppressor-inducer mechanism from the interaction of B-memory cells with Lyt 2- T cells. Immunology. 1983 Oct;50(2):289–295. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voisin G. A. Role of antibody classes in the regulatory facilitation reaction. Immunol Rev. 1980;49:3–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1980.tb00425.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren R. W., Murphy S., Davie J. M. Role of t lymphocytes in the humoral immune response. II. T cell-mediated regulation of antibody avidity. J Immunol. 1976 May;116(5):1385–1390. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weigle W. O. Immunological unresponsiveness. Adv Immunol. 1973;16:61–122. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60296-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberger J. Z., Germain R. N., Ju S. T., Greene M. I., Benacerraf B., Dorf M. E. Hapten-specific T-cell responses to 4-hydroxy-3-nitrophenyl acetyl. II. Demonstration of idiotypic determinants on suppressor T cells. J Exp Med. 1979 Oct 1;150(4):761–776. doi: 10.1084/jem.150.4.761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]