Abstract

The regeneration of pancreatic islet β cells is important for the prevention and cure of diabetes mellitus. We have demonstrated that the administration of poly(ADP-ribose) synthetase/polymerase (PARP) inhibitors such as nicotinamide to 90% depancreatized rats induces islet regeneration. From the regenerating islet-derived cDNA library, we have isolated Reg (regenerating gene) and demonstrated that Reg protein induces β-cell replication via the Reg receptor and ameliorates experimental diabetes. However, the mechanism by which Reg gene is activated in β cells has been elusive. In this study, we found that the combined addition of IL-6 and dexamethasone induced the expression of Reg gene in β cells and that PARP inhibitors enhanced the expression. Reporter gene assays revealed that the −81 ≈ −70 region (TGCCCCTCCCAT) of the Reg gene promoter is a cis-element for the expression of Reg gene. Gel mobility shift assays showed that the active transcriptional DNA/protein complex was formed by the stimulation with IL-6 and dexamethasone. Surprisingly, PARP bound to the cis-element and was involved in the active transcriptional DNA/protein complex. The DNA/protein complex formation was inhibited depending on the autopoly(ADP-ribosyl)ation of PARP in the complex. Thus, PARP inhibitors enhance the DNA/protein complex formation for Reg gene transcription and stabilize the complex by inhibiting the autopoly(ADP-ribosyl)ation of PARP.

Pancreatic β cells of the islets of Langerhans are the only cells that produce insulin in humans as well as in almost all animals, but they have a limited capacity for regeneration, which is a predisposing factor for the development of diabetes mellitus. Strategies for influencing the replication and growth of the β-cell mass are therefore important for the prevention and/or treatment of diabetes (1). We have established a model for islet regeneration in 90% depancreatized rats treated with poly(ADP-ribose) synthetase/polymerase (PARP) inhibitors such as nicotinamide and 3-aminobenzamide: Regenerating islets in the pancreatic remnants of PARP inhibitor-treated rats were markedly enlarged and consisted largely of insulin-producing β cells, preventing the development of diabetes that would otherwise have been caused by the 90% pancreatectomy (2). In screening the regenerating islet-derived cDNA library, we found a novel gene and named it Reg (regenerating gene) (3–5). The rat Reg cDNA encoded a 165-amino acid protein with a 21-amino acid signal peptide. We also isolated the human REG cDNA, which encoded a 166-amino acid protein with a 68% amino acid sequence identity to the rat Reg protein (3). Rat and human Reg proteins stimulated the replication of pancreatic β cells and increased the β-cell mass in 90% depancreatized rats and in nonobese diabetic mice, resulting in the amelioration of diabetes (6, 7). We have recently identified a Reg protein receptor that mediates a growth signal of Reg protein for β-cell regeneration (8). The expression of the Reg receptor, however, was not increased in regenerating islets as compared with that in normal islets (8), suggesting that the regeneration and proliferation of pancreatic β cells for the increase of the β-cell mass are primarily regulated by the expression of Reg gene.

In the present study, we found that Reg gene is activated by IL-6 and dexamethasone and that the transcriptional activation of Reg gene was mediated by the −81 ≈ −70 region of the rat Reg gene promoter. Southwestern and immunoblot analyses showed that PARP bound to the 12-bp cis-regulatory element. Gel-mobility shift assays (GMSA) showed that PARP was involved in the active transcriptional DNA/protein complex and that the complex formation was regulated by the autopoly(ADP-ribosyl)ation of PARP. A possible regulatory role of PARP in Reg gene transcription and DNA repair in β cells is also discussed, especially in connection with our previous findings on DNA repair (1, 9–13).

Materials and Methods

Induction of Reg Gene Expression.

RINm5F cells, a rat insulinoma-derived β-cell line, were maintained as described (8). The cells showed increases in BrdUrd incorporation and in cell numbers in response to Reg protein as did primary cultured rat islets (6, 8). For the stimulation experiments, RINm5F cells were seeded at 1.5 × 106 cells per 25 cm2 flask and incubated for 24 h, and then the medium was replaced with fresh medium containing the indicated amount of stimulants, 10 mM nicotinamide, 2 mM 3-aminobenzamide, 500 units/ml IL-1β (Sigma), 20 ng/ml IL-6 (Genzyme), 500 units/ml interferon (IFN)γ (Roche Molecular Biochemicals), 1,000 units/ml tumor necrosis factor (TNF)α (Roche), 100 nM dexamethasone (Sigma), or combinations thereof. Twenty-four hours later, the cells were harvested, and total RNA was prepared using cesium trifluoroacetate as described (14, 15). RT-PCR was performed using primers corresponding to nucleotides 23–43 and 572–593 of rat Reg mRNA (3). The medium was collected and subjected to immunoblot analysis as described (16). WST-1 cleavage by mitochondrial dehydrogenases in viable cells and BrdUrd incorporation were measured as described (8) using a cell proliferation reagent WST-1 (Roche) and a colorimetric cell proliferation ELISA kit (Roche), respectively.

Immunoblot Analyses.

The medium or nuclear extract of RINm5F cells was subjected to SDS/PAGE and electrotransferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane as described (14, 15). Western blotting was carried out using an anti-rat Reg monoclonal antibody (17) or anti-PARP antibodies (C-2-10, CLONTECH; 06-557, Upstate Biotechnology, Lake Placid, NY).

Promoter Assay.

Luciferase reporter gene constructs were generated as described (18). RINm5F cells were seeded at 1 × 105 cells per well in a 24-well dish. After 48 h, 3.0 μg of test plasmid and 0.2 μg of pCMV-SPORT β-galactosidase (Life Technologies, Inc.) were transfected by lipofection (19) using DMRIE-C (Life Technologies, Inc.). After 24 h, the medium of each dish was replaced with fresh medium containing stimulants and incubated further for 24 h. Cells were harvested in 1 ml of ice-cold PBS, washed twice with PBS, and extracts were prepared in extraction buffer (0.1 M potassium phosphate, pH 6.8/1 mM DTT). The protein concentration was determined using a Coomassie reagent kit (Pierce) and BSA as a standard. Luciferase activity was determined by chemiluminescence substrate using a Pica Gene luminescence kit (Toyo, Tokyo). β-galactosidase activity was determined using Aurora GAL-XE (ICN).

Gel-Mobility Shift Assays.

DNA probes for GMSA were synthesized as oligonucleotides. The sequences of the individual oligonucleotides in the sense orientation were as follows: probe 1, 5′-TTCCTTGCCCCTCCCATTTTTC-3′ corresponding to nucleotides −86 ≈ −65 of rat Reg gene (18); probe M1, 5′-TTCCTTGCCCCTAACATTTTTC-3′; probe M2, 5′-TTCCTTGCCCCGCCCATTTTTC-3′; probe M3, 5′-TTCCTTGCCCCACCCATTTTTC-3′; Sp1 (20), 5′-ATTCGATCGGGGCGGGGCGAGC-3′; GKLF (21), 5′-AGGAGAAAGAAGGGCGTAGTATCTA-3′; IK-BS4 (22), 5′-TCAGCTTTTGGGAATGTATTCCCTGTCA-3′. Nuclear extracts from RINm5F cells were prepared as described (18) and stored at −80°C until use. GMSA was performed as described (23). Briefly, the nuclear extract (10 μg) or purified human PARP (10 ng; Trevigen, Gaithersburg, MD) was incubated in a final volume of 20 μl of buffer containing 20 mM Tris⋅HCl (pH 7.9)/2 mM MgCl2/50 mM NaCl/2 mM EDTA/10% glycerol/0.1% Nonidet P-40/1 mM DTT/50 μg/ml BSA/1 μg of poly(dI-dC). After incubation for 10 min at room temperature, 2.5 pmol of double-stranded DNA, previously labeled by an exchange reaction using MEGALABEL (Takara Shuzo, Kyoto) and [γ-32P]ATP (Amersham Pharmacia), were added and incubated for 30 min at room temperature; then the binding reactions were resolved on prerun 6% acrylamide gel. When competition experiments were conducted in the presence of a 100-fold molar excess of cold probe, an unlabeled competitor was added with the labeled probe. In the supershift assay, 2 μg of antibody for supershift grade (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) were added before the addition of the 32P-labeled probe. For immunodepletion, nuclear extracts were treated with 2 μg of an antibody against PARP (Upstate Biotechnology) or CD38 (24), or of preimmune serum for 10 min at 0°C before the addition of the probe as described (25).

Southwestern Blot Analysis.

Southwestern blot analysis was carried out as described (26). In brief, nuclear extracts (25 μg) or purified human PARP (40 ng) were subjected to SDS/PAGE (7%). The resolved proteins were transferred electrophoretically to Immobilon (Millipore). The blot was first washed twice (10 min each, room temperature) in 20 mM Hepes (pH 7.9)/3 mM MgCl2/40 mM KCl/10 mM β-mercaptoethanol, blocked for 60 min in 20 mM Hepes (pH 7.9) containing 4% nonfat milk, and then washed once in binding buffer consisting of 10 mM Hepes (pH 7.9)/70 mM NaCl/1 mM DTT/0.3 mM MgCl2/0.1% Triton X-100. Hybridization of the blot with radiolabeled probe (2 × 105 cpm/ml) was performed for 3 h at room temperature in 40 μl/cm2 binding buffer containing BSA (60 μg/ml) and poly(dI-dC) (37.5 μg/ml). Before exposure of the blot to x-ray film, it was washed twice (5 min at room temperature) in the binding buffer containing 0.01% Triton X-100. To evaluate the effect of poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation on DNA binding, the PARP activity was reconstituted on the transferred membrane, and the membrane was incubated with 1 mM β-NAD+ in the presence or absence of PARP inhibitors (1 mM nicotinamide or 0.1 mM 3-aminobenzamide) as described (27) and then subjected to Southwestern analysis.

Results

Induction of Reg Gene.

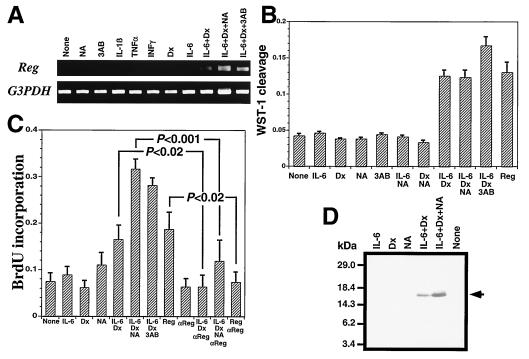

We analyzed the Reg gene expression by RT-PCR. The combined addition of IL-6/dexamethasone induced Reg mRNA accumulation in RINm5F β cells (Fig. 1A). Moreover, in the presence of PARP inhibitors such as nicotinamide and 3-aminobenzamide, the combined addition of IL-6/dexamethasone resulted in a further enhancement of the Reg mRNA level. Treatment with nicotinamide, 3-aminobenzamide, IL-1β, TNFα, IFNγ, dexamethasone, or IL-6 alone had no effect on Reg expression. The combination of dexamethasone with IL-1β, TNFα, or IFNγ did not induce the Reg gene expression, and the combination of PARP inhibitors with either IL-6 or dexamethasone alone was also ineffective (data not shown). As shown in Fig. 1B, the combined addition of IL-6/dexamethasone/PARP inhibitors increased the number of RINm5F cells by WST-1 assay. As shown in Fig. 1C, the treatment with IL-6/dexamethasone/PARP inhibitors increased BrdUrd incorporation, and the increase was attenuated by the addition of anti-Reg monoclonal antibody, suggesting that the growth stimulation by the addition of IL-6, dexamethasone, and PARP inhibitors is achieved by the increase of Reg protein in the medium, which acts as an autocrine/paracrine growth factor on β cells via Reg receptor. In fact, the combined addition of IL-6/dexamethasone and/or nicotinamide induced marked Reg protein secretion (Fig. 1D). These observations concerning the effects of PARP inhibitors on Reg gene expression may explain our previous finding that islet regeneration was observed in 90% depancreatized rats receiving PARP inhibitors such as nicotinamide and 3-aminobenzamide (1–4, 12, 13, 17, 28).

Figure 1.

Induction of Reg gene by IL-6/dexamethasone/PARP inhibitors. RINm5F β cells were treated with IL-1β, TNFα, IFNγ, IL-6, dexamethasone (Dx), nicotinamide (NA), 3-aminobenzamide (3AB), Reg protein, and anti-rat Reg monoclonal antibody (17) (αReg). Values represent mean ± SEM of at least seven experiments. Statistical analyses were performed using Student's t test. (A) RT-PCR analysis. Expression of Reg and of the control glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (G3PDH) gene were analyzed by RT-PCR. (B) WST-1 assay. Reg (1.5 μg/ml) was added to the medium. WST-1 cleavages were significantly increased by the incubation with IL-6/Dx, IL-6/Dx/NA, IL-6/Dx/3AB, and Reg (P < 0.001). (C) BrdUrd incorporation. Reg (1.5 μg/ml) and αReg (15 μg/ml) were added to the medium. (D) Immunoblot analysis. Secreted Reg protein was analyzed by immunoblot of the culture medium of the RINm5F cells.

Identification of Regulatory Element.

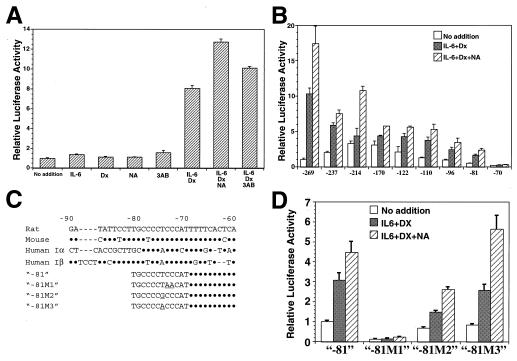

The presence of a functional promoter element responsive to stimulation by IL-6/dexamethasone/PARP inhibitor in the 5′-flanking region of the rat Reg gene (18) was tested by transient expression assays. A 2,303-bp fragment containing the 5′-flanking region of Reg gene was fused to the luciferase gene and transfected into RINm5F β cells. Fig. 2A shows a comparison of luciferase activities in extracts from RINm5F cells transfected with the above constructs. Treatments with IL-6/dexamethasone, IL-6/dexamethasone/nicotinamide, and IL-6/dexamethasone/3-aminobenzamide significantly increased the luciferase activity, whereas IL-6, dexamethasone, nicotinamide, 3-aminobenzamide alone, nicotinamide/IL-6 (data not shown), or nicotinamide/dexamethasone (data not shown) was ineffective.

Figure 2.

IL-6/dexamethasone/PARP inhibitor-sensitive cis-element of Reg promoter. Luciferase activities were expressed relative to the level of luciferase activity in untreated control cells (no addition), which was assigned a value of 1.0. Values represent mean ± SEM of three to eight independent transfection experiments. Statistical analyses were performed using Student's t test. (A) Induction of Reg/luciferase hybrid gene expression by IL-6, dexamethasone (Dx), and PARP inhibitors. Luciferase activities were significantly increased by the addition of IL-6/Dx, IL-6/Dx/NA, and IL-6/Dx/3AB (P < 0.001). (B) Localization of IL-6/Dx/nicotinamide (NA)-responsive region in the Reg promoter. In all of the constructs except for −70, luciferase activities were significantly increased by the addition of IL-6/Dx and IL-6/Dx/NA (P < 0.05). (C) Alignment of Reg gene promoter regions. Rat (18), mouse (52), and human (16, 31) Reg I gene promoter regions were aligned. Nucleotide substitutions in the cis-element are indicated by underlines. Dots indicate residues that are identical to the rat promoter, and sequence gaps resulting from optimization of alignment are indicated by dashes. (D) Site-directed mutagenesis of the cis-element within the Reg promoter. In all of the mutants except for −81 M1, significant increases in luciferase activities by the stimulation of IL-6/Dx and IL-6/Dx/NA were retained (P < 0.01).

To identify the region necessary for the induction of Reg gene by IL-6/dexamethasone/nicotinamide, progressive deletions of the Reg promoter were performed. The deletion down to position −269 did not alter significantly the expression of the reporter gene induced by the combined addition of IL-6/dexamethasone/PARP inhibitors. As shown in Fig. 2B, progressive deletion to position −81 resulted in a gradual decrease of luciferase activity without altering the potent inducibility by IL-6/dexamethasone and the enhancement by nicotinamide, but an additional deletion to nucleotide −70 caused a loss of the inducibility. These results suggest that the region between nucleotides −81 and −70 (TGCCCCTCCCAT) is essential for both the IL-6/dexamethasone- and the IL-6/dexamethasone/nicotinamide-sensitive Reg promoter activities. The −81 ≈ −70 region is highly conserved in human and mouse Reg genes (Fig. 2C). A computer-assisted search for sequences similar to known cis-acting elements (29, 30) revealed that sequences similar to the GC box (Sp1 binding site) and the Ikaros binding element are present in the 12-bp region. As shown in Fig. 2 C and D, site-directed mutagenesis of the region from −81 to −70 was conducted within the luciferase construct of “−81,” and the influence of the mutations (“−81 M1,” “−81 M2,” and “−81 M3” in Fig. 2D) on the amplitude of luciferase induction by IL-6/dexamethasone/nicotinamide was monitored. The site-directed mutation M1 (TGCCCCTCCCAT→TGCCCCTAACAT), which altered the GC box-like sequence, abolished the induction. The mutant M2 (TGCCCCTCCCAT→TGCCCCGCCCAT), which changed the Ikaros binding site to a classical GC box sequence, and the mutant M3 (TGCCCCTCCCAT→TGCCCCACCCAT), which changed the sequence of the rat Reg [now termed Reg I (5, 18)] promoter to those of human REG (16) [now termed REG Iα (31)] and REG Iβ (31), showed the induction by IL-6/dexamethasone/nicotinamide, indicating that the GC box-like sequence (CCCC T/A CCC) is essential for conferring the IL-6/dexamethasone sensitivity and the enhancement by nicotinamide in Reg genes.

PARP Involvement in Reg Transcription.

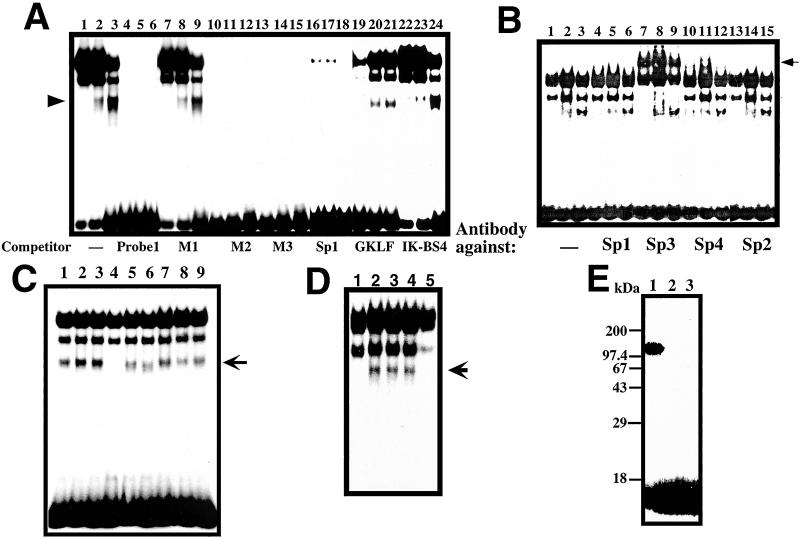

As shown in Fig. 3A, although several bands were detected in GMSA with nuclear extracts from RINm5F β cells, the lowest band (see arrowhead) was only detected in the nuclear extracts of RINm5F cells treated with IL-6/dexamethasone and with IL-6/dexamethasone/nicotinamide, and the intensity seemed to be correlated to the luciferase activity exhibited in the cells (Fig. 2). The band disappeared by the addition of excess amounts of unlabeled probe 1 as well as competitors containing the M2 mutation (probe M2), the M3 mutation (probe M3), and the GC box consensus sequence (probe Sp1) (20). However, the competitor containing the M1 mutation (probe M1) could not competitively block the binding to the 32P-labeled probe. These results suggest that the lowest band showed the possible active transcriptional complex in the nuclear extracts of RINm5F cells stimulated with IL-6/dexamethasone and IL-6/dexamethasone/nicotinamide. The GKLF binding sequence (21) and Ikaros binding sequence (22) were also ineffective as competitors (Fig. 3A). To investigate which Sp/XKLF transcription factor (32) binds to the sequence, a polyclonal antibody against Sp1, Sp2, Sp3, or Sp4 was used in a supershift assay in which RINm5F cell nuclear extracts were exposed to the antibody before incubation with the probe. As shown in Fig. 3B, only the addition of Sp3 antibody led to the appearance of a supershift band (a filled arrow from an open arrow), but the band corresponding to the possible active transcriptional complex was not supershifted, suggesting that a GC box/GC box-like sequence binding protein(s) other than Sp1, Sp2, Sp3, or Sp4 binds to the sequence to activate the Reg gene transcription. Additions of antibodies against Stat3 and glucocorticoid receptor failed to show any “supershift” (data not shown).

Figure 3.

GMSA analysis of Reg gene promoter. (A) Binding of RINm5F cell nuclear extracts to the cis-element by GMSA. Nuclear extracts from untreated cells were applied onto lanes 1, 4, 7, 10, 13, 16, 19, and 22; those from IL-6/dexamethasone (Dx)-treated cells were applied onto lanes 2, 5, 8, 11, 14, 17, 20, and 23; and those from IL-6/Dx/nicotinamide (NA)-treated cells were applied onto lanes 3, 6, 9, 12, 15, 18, 21, and 24. (B) Supershift assay of the cis-element binding factors by antibodies against Sp1 (lanes 4–6), Sp2 (lanes 13–15), Sp3 (lanes 7–9), and Sp4 (lanes 10–12). Nuclear extracts from untreated cells were applied onto lanes 1, 4, 7, 10, and 13; those from IL-6/Dx-treated cells were applied onto lanes 2, 5, 8, 11, and 14; and those from IL-6/Dx/NA-treated cells were applied onto lanes 3, 6, 9, 12, and 15. (C) Effects of poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation of nuclear proteins on the binding ability to the cis-element by GMSA. 0.2 μl of 100 mM β-NAD+, 100 mM α-NAD+, 100 mM ADP-ribose, 1 mM cyclic ADP-ribose, 100 mM NA, and/or 10 mM 3-aminobenzamide (3AB) were added in a 20-μl reaction before the addition of the 32P-labeled probe 1. Lane 1, none; lane 2, NA; lane 3, 3AB; lane 4, β-NAD+; lane 5, β-NAD++NA; lane 6, β-NAD++3AB; lane 7, α-NAD+; lane 8, ADP-ribose; and lane 9, cyclic ADP-ribose. (D) The involvement of PARP in the active transcriptional complex was evidenced by the immunodepletion of PARP. An active transcriptional complex of the nuclear extract from RINm5F cells stimulated by IL-6/Dx (lane 2) was blocked by the addition of 1 mM β-NAD+ as described above (lane 1).The complex formation was inhibited by the treatment of nuclear extract with an anti-PARP antibody (lane 5) but not with an anti-CD38 antibody (lane 4) nor with preimmune serum (lane 3). An arrow indicates the position of the active transcriptional complex. (E) Evidence of autopoly(ADP-ribosyl)ation of PARP in the GMSA reaction. Poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation was performed in the same condition as GMSA in the presence of 62 nM [adenylate-32P]NAD+ (2 × 106 cpm, NEN). After the incubation, proteins were precipitated by the addition of 9-volume acetone, separated by SDS/PAGE (12.5%), and autoradiographed. NA (1 mM, lane 2) or 3AB (0.1 mM, lane 3) was added in the GMSA incubation.

To investigate how PARP inhibitors enhance the formation of the active DNA/protein complex, we added NAD+, NAD+ metabolites, and PARP inhibitors into the GMSA reaction. As shown in Fig. 3C, the addition of β-NAD+, but not that of α-NAD+ (33), inhibited the active DNA/protein complex formation. Metabolites of β-NAD+ such as ADP-ribose and cyclic ADP-ribose (14, 34, 35) did not attenuate the formation of the complex. Nicotinamide and 3-aminobenzamide quenched the inhibitory effect of β-NAD+ on the complex formation, and the concentrations of the half-maximal inhibition by nicotinamide and 3-aminobenzamide were estimated to be 250 μM and 30 μM, respectively. Since these concentrations of nicotinamide and 3-aminobenzamide inhibited poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation but not mono(ADP-ribosyl)ation (36), the inhibitory effect of β-NAD+ on the active DNA/protein complex formation through the poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation was indicated. After the GMSA electrophoresis, the DNA/proteins were transferred to a PVDF membrane and subjected to Western blot analysis using PARP antibodies. PARP was detected in the active DNA/protein complex (data not shown). The involvement of PARP in the active complex was further evidenced by the immunodepletion of PARP (Fig. 3D). Furthermore, when the GMSA reaction was incubated in the presence of [32P]NAD+ and the reaction products were separated by SDS/PAGE and autoradiographed, autopoly(ADP-ribosyl)ated PARP as a 113-kDa band was detected, and the autopoly(ADP-ribosyl)ation was attenuated in the presence of PARP inhibitors (Fig. 3E). These results indicate that PARP is involved in the active DNA/protein complex for Reg gene transcription and that the complex formation is inhibited depending on the autopoly(ADP-ribosyl)ation of PARP in the complex.

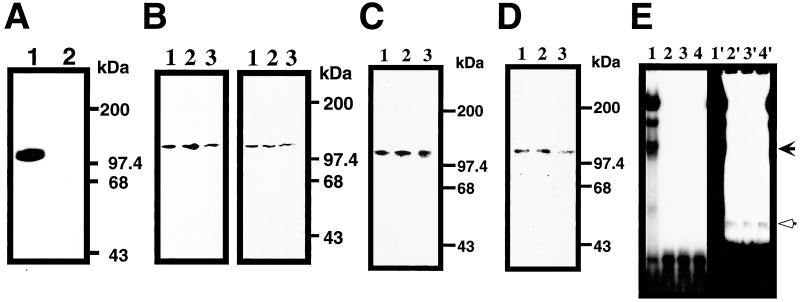

To determine the number and size of the proteins that directly interact with the cis-element of Reg gene promoter, Southwestern experiments were carried out. As shown in Fig. 4A, a 113-kDa nuclear protein was found to bind to the sequence (Probe 1) but not to the mutated probe (M1), suggesting that PARP is the binding protein to the cis-regulatory element of Reg gene, although the involvement of other proteins that require a multiprotein complex formation to bind the cis-element cannot be totally excluded. The membrane used for the Southwestern blot analysis was incubated with two different antibodies against PARP. The 113-kDa band recognized by the antibodies was matched to the band identified by the Southwestern blot (Fig. 4B Right), indicating the binding of PARP to the sequence in the Reg promoter. Since no other poly(ADP-ribosyl)ated proteins than PARP itself were detected in the GMSA reaction (Fig. 3E), the effects of autopoly(ADP-ribosyl)ation of PARP on the ability of the cis-element binding were tested. The cis-element binding ability of PARP appeared to be independent of the poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation (Fig. 4C). Moreover, the purified PARP also showed the binding to the cis-element, which was also independent of the poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation of PARP (Fig. 4D). The purified PARP formed a retarded band in GMSA (see Fig. 4E, open arrow), and the position of the band was different from that of the active transcriptional DNA/protein complex in RINm5F cell nuclear extracts (Fig. 4E, filled arrow), suggesting that the DNA/protein complex contains some nuclear proteins in addition to PARP.

Figure 4.

PARP as the cis-element binding protein for Reg gene. (A) Southwesten analysis of RINm5F cell nuclear extract. Nuclear extract from IL-6/dexamethasone (Dx)-treated cells was probed by probe 1 (lane 1) or probe M1 (lane 2). (B) Southwestern and immunoblot analyses of RINm5F cell nuclear extracts. In the left panel, Southwestern blot analysis was performed using probe 1. In the right panel, the blot was then probed by an anti-PARP antibody. Nuclear extracts from untreated, IL-6/dexamethasone (Dx)-, and IL-6/Dx/nicotinamide (NA)-treated cells were applied to lanes 1, 2, and 3, respectively. (C) Effects of poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation on the binding ability to the cis-element. Nuclear extracts were separated by SDS/PAGE and transferred to a PVDF membrane. The membrane was incubated with 1 mM β-NAD+ (lane 1), β-NAD+/1 mM NA (lane 2), and β-NAD+/0.1 mM 3-aminobenzamide (3AB) (lane 3) and probed by 32P-labeled probe 1. (D) Binding of PARP to the cis-element in Southwestern analysis. Purified PARP was subjected to SDS/PAGE and transferred to a PVDF membrane. The membrane was incubated with 1 mM β-NAD+ (lane 1), β-NAD+/1 mM NA (lane 2), and β-NAD+/0.1 mM 3AB (lane 3) and probed by 32P-labeled probe 1. No binding to PARP was detected using probe M1 (data not shown). (E) Binding of PARP to the cis-element in GMSA. Purified PARP was incubated in the presence of 1 mM β-NAD+ (lane 2), β-NAD+/1 mM NA (lane 3), and β-NAD+/0.1 mM 3AB (lane 4) with 32P-labeled probe 1. Nuclear extract from IL-6/Dx/NA-treated cells was also analyzed as a control (lane 1). Right panel (lanes 1′–4′) represents the long exposure of the left panel (lanes 1–4).

Discussion

Under physiological conditions, Reg protein is not expressed in pancreatic β cells (3, 4, 17), although the Reg protein receptor is expressed (8). In the regenerative process of pancreatic islets, Reg gene expression is induced (3, 4, 12, 17). Therefore, the induction of Reg gene is thought to be one of the crucial events in β-cell regeneration. In addition to regenerating islets in 90% depancreatized rats receiving PARP inhibitors (1–5, 12, 13, 17, 28), Reg gene expression was also observed in the phase of transient β-cell proliferation such as in pancreatic islets of BB rats during the remission phase of diabetes (37), in islets of nonobese diabetic mice during active diabetogenesis (38) and pancreatic ductal cells, which are thought to be progenitor cells of β cells, during differentiation and proliferation in a mouse model of autoimmune diabetes (39), and inflammation in and/or around islets was involved in these cases. The findings in this paper showed that the combined addition of typical inflammatory mediators (IL-6 and the glucocorticoid analogue dexamethasone) induced Reg gene expression and that PARP inhibitors such as nicotinamide and 3-aminobenzamide enhanced the induction. As shown in Figs. 2–4, a novel cis-element responsible for the induction of Reg gene by IL-6/glucocorticoid was identified, and PARP was shown to bind the IL-6/glucocorticoid-responsive element of Reg gene, forming the active transcriptional DNA/protein complex for Reg gene expression. The formation of the active transcriptional complex was further enhanced by the inhibition of the autopoly(ADP-ribosyl)ation of PARP. Since the binding capacity of PARP to the cis-element was unchanged by the poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation of PARP itself, and since the mobility of the PARP/DNA complex in GMSA was different from that of the active DNA/protein complex in RINm5F cell nuclear extracts (Fig. 4), the poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation of PARP itself in the active complex appears to attenuate the transcriptional activity of Reg gene via the inhibition of the interaction of PARP with other nuclear proteins necessary for the formation of the active complex in Reg gene transcription. Thus, PARP inhibitors enhance the Reg gene transcription and the β-cell replication. This can account for the previous observation of islet regeneration in 90% depancreatized rats treated with PARP inhibitors (2–4, 12, 13, 17, 28) and also supports our previous proposition that the restriction of β-cell replication is relieved by PARP inhibitors (1).

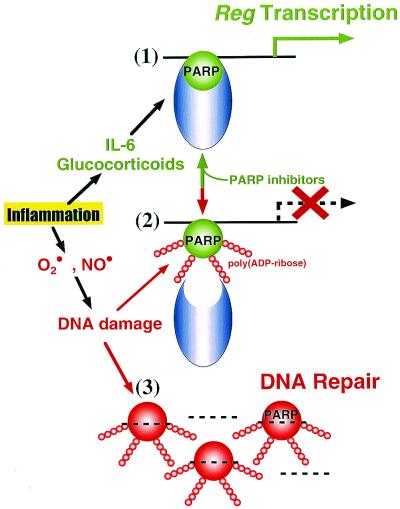

The existence of PARP was first reported nearly 35 years ago (40–42). Since then, the biological significance of PARP has been reported in many cellular processes (43, 44). A major cellular function of PARP has been considered to be its participation in the DNA repair pathway. In pancreatic islets, genotoxic treatments such as with streptozotocin greatly enhanced the nuclear PARP activity for DNA repair and resulted in depletion of the intracellular NAD+ pool (1, 9–13). Pancreatic β-cell destruction via this mechanism, which we proposed in 1981 (9, 10), has recently been evidenced by PARP knockout mice (45–48). In the present study, we demonstrated that PARP formed the active complex for Reg transcription with some nuclear proteins and that the complex formation was stabilized when the PARP was not autopoly(ADP-ribosyl)ated in the presence of PARP inhibitors. Thus, at least in pancreatic β cells, a unified picture of PARP roles in the Reg transcription, replication, and DNA repair may be as depicted in Fig. 5.

Figure 5.

Representation of the unified role of PARP in the Reg gene transcription and DNA repair. β cells are affected by many agents such as immunological abnormalities, virus infections, irradiation, and chemical substances (1, 14–18), leading to local inflammation in and/or around pancreatic islets. (1) Inflammatory mediators such as IL-6 and glucocorticoids are produced in the inflammation process. IL-6/glucocorticoid stimulation induces the formation of an active transcriptional complex for Reg, a β-cell regenerating factor gene, in which PARP is involved, and when the PARP is not poly(ADP-ribosyl)ated in the presence of PARP inhibitors, the transcriptional complex is stabilized and the Reg gene transcription is maintained. Reg protein then produced in β cells acts as an autocrine/paracrine growth factor on β cells via the Reg receptor. DNA replication in β cells thus occurs, and the β-cell regeneration is achieved. (2) DNA-damaging substances such as superoxide (O⋅2) and nitric oxide (NO⋅) are frequently produced in inflammatory processes. When the DNA is damaged, PARP senses DNA nicks and autopoly(ADP-ribosyl)ates itself for the DNA repair. Once PARP is autopoly(ADP-ribosyl)ated, the formation of the Reg gene transcriptional complex is inhibited, interfering with the interaction between PARP and other nuclear proteins necessary for the active complex; therefore, the transcription of Reg gene stops. (3) When DNA is massively damaged, PARP is rapidly activated to repair the DNA (1, 9–13), and the complex for Reg gene transcription is not formed at all.

Furthermore, since the GC box-like cis-element identified in this study exists in many other genes such as mouse Reg IIIβ gene (49), whose product is a Schwann cell mitogen (50), and human hepatocyte growth factor gene (51), PARP may be involved in gene transcription in a variety of cells.

Acknowledgments

We thank Brent Bell for valuable assistance in preparing the manuscript for publication and Yuya Shichinohe for technical assistance. This work was supported in part by grants-in-aid from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture, Japan and the Research Fund for Digestive Molecular Biology and is in partial fulfillment of the degree of Doctor of Medical Science at Tohoku University (T.A.). T.A. is a recipient of a fellowship from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science.

Abbreviations

- PARP

poly(ADP-ribose) synthetase/polymerase

- GMSA

gel-mobility shift assay

- TNF

tumor necrosis factor

- PVDF

polyvinylidene difluoride

Footnotes

Article published online before print: Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 10.1073/pnas.240458597.

Article and publication date are at www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.240458597

References

- 1.Okamoto H. BioEssays. 1985;2:15–21. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yonemura Y, Takashima T, Miwa K, Miyazaki I, Yamamoto H, Okamoto H. Diabetes. 1984;33:401–404. doi: 10.2337/diab.33.4.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Terazono K, Yamamoto H, Takasawa S, Shiga K, Yonemura Y, Tochino Y, Okamoto H. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:2111–2114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Terazono K, Watanabe T, Yonemura Y. In: Molecular Biology of the Islets of Langerhans. Okamoto H, editor. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press; 1990. pp. 301–313. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yonekura H, Unno M, Watanabe T, Moriizumi S, Suzuki Y, Miyashita H, Yonemura Y, Sugiyama K, Okamoto H. In: Frontiers of Insulin Secretion and Pancreatic B-Cell Research. Flatt R, Lenzen S, editors. London: Smith-Gordon; 1994. pp. 581–588. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Watanabe T, Yonemura Y, Yonekura H, Suzuki Y, Miyashita H, Sugiyama K, Moriizumi S, Unno M, Tanaka O, Kondo H, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:3589–3592. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.9.3589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gross D J, Weiss L, Reibstein I, van den Brand J, Okamoto H, Clark A, Slavin S. Endocrinology. 1998;139:2369–2374. doi: 10.1210/endo.139.5.5997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kobayashi S, Akiyama T, Nata K, Abe M, Tajima M, Shervani N J, Unno M, Matsuno S, Sasaki H, Takasawa S, et al. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:10723–10726. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.15.10723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yamamoto H, Uchigata Y, Okamoto H. Nature (London) 1981;294:284–286. doi: 10.1038/294284a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Okamoto H. Mol Cell Biochem. 1981;37:43–61. doi: 10.1007/BF02355886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Uchigata Y, Yamamoto H, Kawamura A, Okamoto H. J Biol Chem. 1982;257:6084–6088. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Okamoto H. In: Molecular Biology of the Islets of Langerhans. Okamoto H, editor. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press; 1990. pp. 209–231. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Okamoto H. In: Lessons from Animal Diabetes VI. Shafrir E, editor. Boston: Birkhäuser; 1996. pp. 97–111. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Okamoto H, Takasawa S, Tohgo A, Nata K, Kato I, Noguchi N. Methods Enzymol. 1997;280:306–318. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(97)80122-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Takasawa S, Tohgo A, Noguchi N, Koguma T, Nata K, Sugimoto T, Yonekura H, Okamoto H. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:26052–26054. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Watanabe T, Yonekura H, Terazono K, Yamamoto H, Okamoto H. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:7432–7439. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Terazono K, Uchiyama Y, Ide M, Watanabe T, Yonekura H, Yamamoto H, Okamoto H. Diabetologia. 1990;33:250–252. doi: 10.1007/BF00404804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miyashita H, Yonekura H, Unno M, Suzuki Y, Watanabe T, Moriizumi S, Takasawa S, Okamoto H. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1994;1219:241–243. doi: 10.1016/0167-4781(94)90281-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Felgner J H, Kumar R, Sridhar C N, Wheeler C J, Tsai Y J, Border R, Ramsey P, Martin M, Felgner P L. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:2550–2561. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Berg J M. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:11109–11110. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.23.11109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang W, Shields J M, Sogawa K, Fujii-Kuriyama Y, Yang V W. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:17917–17925. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.28.17917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Molnar A, Georgopoulos K. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:8292–8303. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.12.8292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garabedian M J, LaBaer J, Liu W-H, Thomas J R. In: Gene Transcription: A Practical Approach. Hamesm B D, Higgins S J, editors. Oxford: IRL Press; 1993. pp. 243–293. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kato I, Yamamoto Y, Fujimura M, Noguchi N, Takasawa S, Okamoto H. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:1869–1872. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.4.1869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Manzano-Winkler B, Novina C D, Roy A L. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:12076–12081. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.20.12076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jensen D E, Rich C B, Terpstra A J, Farmer S R, Foster J A. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:6555–6563. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.12.6555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Simonin F, Briand J-P, Muller S, de Murcia G. Anal Biochem. 1991;195:226–231. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(91)90321-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Okamoto H, Yamamoto H, Yonemura Y. In: ADP-Ribosylaltion of Proteins. Althaus F R, Hilz H, Shall S, editors. Heidelberg: Springer; 1985. pp. 410–416. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Quandt K, Frech K, Karas H, Wingender E, Werner T. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:2878–2884. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.23.4878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Heinemeyer T, Wingender E, Reuter I, Hermjakob H, Kel A E, Kel O V, Ignatieva E V, Ananko E A, Podkolodnaya O A, Kolpakov F A, et al. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:362–367. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.1.362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moriizumi S, Watanabe T, Unno M, Nakagawara K, Suzuki Y, Miyashita H, Yonekura H, Okamoto H. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1994;1217:199–202. doi: 10.1016/0167-4781(94)90035-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Philipsen S, Suske G. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:2991–3000. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.15.2991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Okamoto H. Methods Enzymol. 1970;18:67–71. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Takasawa S, Nata K, Yonekura H, Okamoto H. Science. 1993;259:370–373. doi: 10.1126/science.8420005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Okamoto H, Takasawa S, Nata K, Kato I, Tohgo A, Noguchi N. In: Human CD38 and Related Molecules. Mehta K, Malavasi F, editors. Basel: Karger; 2000. pp. 121–145. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rankin P W, Jacobson E L, Benjamin R C, Moss J, Jacobson M K. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:4312–4317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ishii C, Kawazu S, Tomono S, Ohno T, Shimizu M, Kato N, Fukuda M, Ito Y, Kurihara S, Murata K, et al. Endocr J. 1993;40:269–273. doi: 10.1507/endocrj.40.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Baeza N J, Moriscot C J, Renaud W P, Okamoto H, Figarella C G, Vialettes B H. Diabetes. 1996;45:67–70. doi: 10.2337/diab.45.1.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Anastasi E, Ponte E, Gradini R, Bulotta A, Sale P, Tiberti C, Okamoto H, Dotta F, DiMario U. Eur J Endocrinol. 1999;141:644–652. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.1410644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chambon P, Weill J D, Doly J, Strosser M T, Mandel P. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1966;25:638–643. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nishizuka Y, Ueda K, Nakazawa K, Hayaishi O. J Biol Chem. 1967;242:3164–3171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sugimura T, Fujimura S, Hasegawa S, Kawamura Y. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1967;138:438–441. doi: 10.1016/0005-2787(67)90507-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ueda K, Hayaishi O. Annu Rev Biochem. 1985;54:73–100. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.54.070185.000445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.D'Amours D, Desnoyers S, D'Silva I, Poirier G G. Biochem J. 1999;342:249–268. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Charron M J, Bonner-Weir S. Nat Med. 1999;5:269–270. doi: 10.1038/6479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Burkart V, Wang Z Q, Radons J, Heller B, Herceg Z, Stingl L, Wagner E F, Kolb H. Nat Med. 1999;5:314–319. doi: 10.1038/6535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Masutani M, Suzuki H, Kamada N, Watanabe M, Ueda O, Nozaki T, Jishage K, Watanabe T, Sugimoto T, Nakagama H, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:2301–2304. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.5.2301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pieper A A, Brat D J, Krug D K, Watkins C C, Gupta A, Blackshaw S, Verma A, Wang Z Q, Snyder S H. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:3059–3064. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.6.3059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Narushima Y, Unno M, Nakagawara K, Mori M, Miyashita H, Suzuki Y, Noguchi N, Takasawa S, Kumagai T, Yonekura H, et al. Gene. 1997;185:159–168. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(96)00589-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Livesey F J, O'Brien J A, Li M, Smith A G, Murphy L J, Hunt S P. Nature (London) 1997;390:614–618. doi: 10.1038/37615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Miyazawa K, Kitamura A, Kitamura N. Biochemistry. 1991;30:9170–9176. doi: 10.1021/bi00102a007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Unno M, Yonekura H, Nakagawara K, Watanabe T, Miyashita H, Moriizumi S, Okamoto H, Itoh T, Teraoka H. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:15974–15982. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]