Abstract

RNA editing within the mitochondria of African trypanosomes is characterized by the insertion and deletion of uridylate residues into otherwise incomplete primary transcripts. The reaction takes place in a high molecular mass ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex of uncertain composition. Furthermore, factors that interact with the RNP complex during the reaction are by and large unknown. Here we present evidence for an editing-related biochemical activity of the gRNA-binding protein gBP21. Using recombinant gBP21 preparations, we show that the protein stimulates the annealing of gRNAs to cognate pre-mRNAs in vitro. This represents the presumed first step of the editing reaction. Kinetic data establish an enhancement of the second order rate constant for the gRNA– pre-mRNA interaction. gBP21-mediated annealing is not exclusive for RNA editing substrates since complementary RNAs, unrelated to the editing process, can also be hybridized. The gBP21-dependent RNA annealing activity was identified in mitochondrial extracts of trypanosomes and can be inhibited by immunoprecipitation of the polypeptide. The data suggest a factor-like contribution of gBP21 to the RNA editing process by accelerating the rate of gRNA–pre-mRNA anchor formation.

Keywords: gRNA-binding protein/RNA annealing/RNA editing

Introduction

Mitochondrial primary transcripts in kinetoplastid organisms such as African trypanosomes undergo a unique, post-transcriptional RNA processing reaction known as kinetoplastid (k)RNA editing (reviewed in Estévez and Simpson, 1999). The process is an essential pathway for the expression of mitochondrial genes and is characterized by the insertion and deletion of uridylate residues into defined processing sites of the mitochondrial pre-mRNAs. In contrast to the base modification-type RNA editing reactions in other organisms (Benne and Speijer, 1998), kRNA editing involves hydrolysis and re-ligation of the phosphate backbone of the pre-mRNAs. Editing sites are specified in trans by guide (g)RNA molecules. They provide the information for the processing reaction via base pairing to the pre-edited mRNAs and thus have a template-like function. Stereochemical data (Frech and Simpson, 1996) and results from RNA editing in vitro systems (Byrne et al., 1996; Cruz-Reyes and Sollner-Webb, 1996; Frech and Simpson, 1996; Kable et al., 1996) provide evidence that a minimal RNA editing reaction cycle relies on the action of three enzyme-driven processes: (i) the hydrolysis of the pre-mRNA molecule at an editing site by a gRNA-dependent endonuclease; (ii) the addition or removal of uridylate residues by a terminal uridylyltransferase/nuclease activity; and (iii) the re-ligation of the two pre-mRNA fragments by an RNA ligase. All three activities have been identified in mitochondrial extracts from Trypanosoma brucei and were shown to co-migrate with an in vitro RNA editing activity in density gradient centrifugations (Pollard et al., 1992; Corell et al., 1996; Cruz-Reyes and Sollner-Webb, 1996). Thus, the three ‘core’ activities presumably act within a high molecular mass ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex (Rusché et al., 1997). Although a considerable amount of data concerning the biochemical characteristics of the three activities exists, none of the polypeptides has been identified or its corresponding gene cloned. This, in part, also holds true for accessory factors that might contribute during the initiation, the elongation or the termination phase of the reaction cycle. One example of an accessory activity is mHel61p, a putative DEAD-box-type RNA helicase (Missel et al., 1997). Data suggest that the protein acts at a late stage of the editing reaction, where it potentially facilitates the unwinding of fully base paired gRNA–mRNA helices. A gene knockout analysis verified the involvement of mHel61p since exclusively edited mRNAs were affected by the absence of the protein (Missel et al., 1997). Other potential candidates are TBRGG1, an oligo(U)-binding polypeptide (Vanhamme et al., 1998), REAP-1, an RNA editing complex-associated protein (Madison-Antenucci et al., 1998), and several polypeptides that specifically bind to gRNAs (Köller et al., 1994; Bringaud et al., 1995; Leegwater et al., 1995; Hayman and Read, 1999).

Here we focus on gBP21, an arginine-rich mitochondrial protein from T.brucei (Köller et al., 1997). gBP21 was characterized as a high affinity gRNA-binding polypeptide. A gene knockout analysis established that gBP21 is not essential for RNA editing (Lambert et al., 1999); however, under steady state conditions, the protein was found in association with active RNA editing complexes (Allen et al., 1998). Our data identify a biochemical activity for gBP21, which may contribute to the RNA editing reaction cycle. gBP21 is capable of stimulating base pairing between gRNAs and cognate pre-mRNAs in vitro. The annealing reaction does not require Mg2+ cations or ATP hydrolysis. gBP21 accepts other complementary RNAs as annealing substrates and stimulates the formation of RNA–DNA hybrids but not DNA–DNA hybrids. The annealing activity is detectable within T.brucei mitochondrial extracts and can be depleted by anti-gBP21 antibodies. Recombinant gBP21 restores the activity within depleted extracts. Cumulatively, these data suggest a factor-like involvement of gBP21 in the editing reaction cycle. The polypeptide probably assists during the anchor formation between gRNAs and cognate pre-mRNAs, the first step of the processing reaction.

Results

gBP21 stimulates the annealing of gRNAs to cognate pre-mRNAs

The finding that gBP21 is associated with active RNA editing complexes (Allen et al., 1998) tempted us to test whether the protein might show enzymatic activities that contribute to the editing of pre-mRNAs. The first step of an RNA editing reaction cycle is thought to involve an RNA–RNA interaction between a 5′ sequence of a gRNA and a complementary region on the pre-edited mRNA, 3′ of an editing domain. The double-stranded (ds) structure has been termed ‘anchor hybrid’ (Blum and Simpson, 1990), and early on it was suggested that protein factors might assist the formation and stabilization of the binary complex (Blum et al., 1990). Thus, we analyzed whether recombinant (r)-gBP21 would facilitate a gRNA–pre-edited mRNA interaction using an RNA annealing assay (Portman and Dreyfuss, 1994).

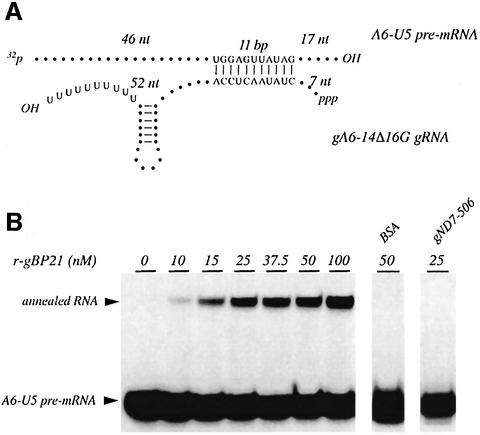

Two RNA molecules known to be active in an RNA editing in vitro system (Seiwert et al., 1996) were chosen as reactants: A6-U5, a pre-edited mRNA (74 nt) derived from the first editing site of the T.brucei ATPase 6 (A6) mRNA; and gA6-14Δ16G [70 nucleotides (nt)], the corresponding gRNA to edit A6-U5. Both molecules were synthesized by in vitro transcription and the pre-mRNA was further 5′-32P-labeled using T4 polynucleotide kinase and [γ-32P]ATP. Annealing of the two RNAs should create an 11 bp hybrid stem structure (Figure 1A) that causes a slower electrophoretic mobility of the annealed RNAs in semi-denaturing (1 M urea) polyacrylamide gels. Figure 1B shows a representative experiment. In the absence of gBP21, only a small amount of gRNA–mRNA annealing is detected. The addition of r-gBP21 stimulates the formation of dsRNA in a concentration-dependent fashion and reaches, at higher gBP21 concentrations, a saturation value. At the specific reaction conditions, ∼10–15% of the input pre-mRNA is converted into the annealed product, which corresponds to a protein:nucleotide ratio of 1:5.5 and a protein:RNA duplex ratio of 20:1. Similar values have been described for the annealing activities of several hnRNP proteins (A1, C1, U) (Portman and Dreyfuss, 1994) and for the translation initiation factors Tif3p (yeast) and eIF-4B (human) (Altmann et al., 1995). No annealing was detected by the addition of bovine serum albumin (BSA), or in the presence of a non-cognate gRNA (gND7-506) (Figure 1B). Lastly, ATP and Mg2+ cations were not required for the formation of the double strand (data not shown).

Fig. 1. Recombinant gBP21 stimulates the annealing of gRNAs to cognate pre-edited mRNAs. (A) Schematic representation of gRNA gA6-14Δ16G forming an 11 bp anchor duplex with pre-edited mRNA A6-U5. The gRNA molecule is depicted including a 3′ hairpin loop and a 3′ oligo(U) extension. The length of the RNA strands left and right of the anchor duplex is given in nucleotides. (B) Autoradiogram of a representative annealing experiment with gA6-14Δ16G and radiolabeled A6-U5 pre-mRNA at the r-gBP21 concentrations indicated. Electrophoresis was performed in 8% (w/v) polyacrylamide gels at semi-denaturing conditions (1 M urea). Arrowheads indicate the electrophoretic mobility of the A6-U5 pre-mRNA and the annealed gRNA–pre-mRNA product. Control reactions were set up with 50 nM BSA (instead of r-gBP21) and gND7-506, a non-cognate gRNA (instead of gA6-14Δ16G).

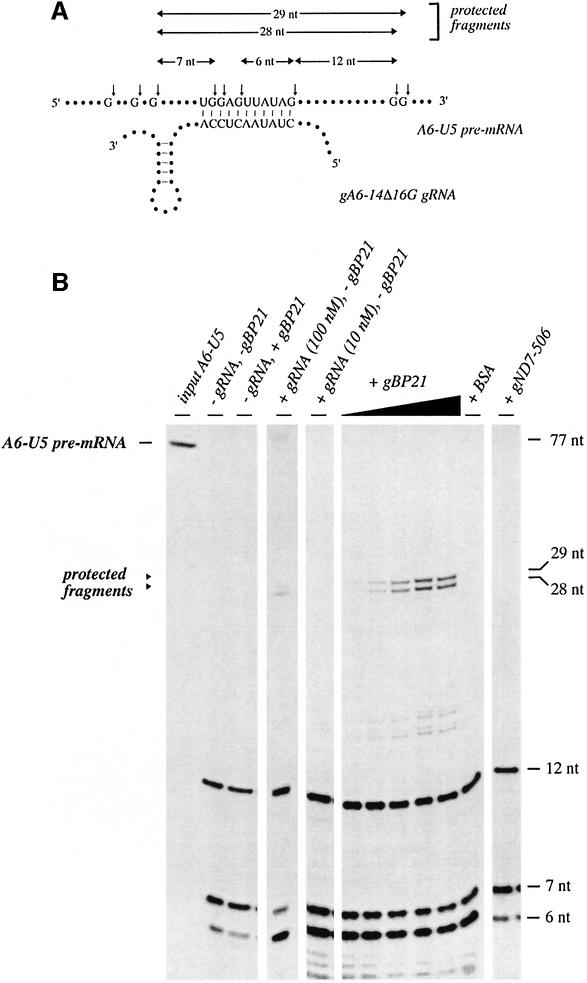

To verify the annealing of the predicted 11 bp duplex RNA (Figure 1A), we performed RNase T1 protection experiments (Portman and Dreyfuss, 1994). As outlined in Figure 2A, the formation of the pre-mRNA–gRNA hybrid structure should protect four G-nucleotides within the pre-mRNA from RNase T1 digestion and thus should result in the generation of a radioactive oligoribonucleotide 28 nt in length. Any non-annealed RNA should be hydrolyzed to fragments ≤12 nt. A typical result is shown in Figure 2B. In the absence of both gBP21 and gRNA, the pre-mRNA is digested to the predicted set of small oligoribonucleotides. The addition of gBP21 in the absence of gRNA did not result in the protection of a pre-mRNA fragment, which indicates no stable binding of gBP21 to the pre-mRNA alone. This was tested for [α-32P]UTP- as well as [α-32P]GTP-labeled A6-U5 pre-mRNAs to ensure that all parts of the pre-mRNA were scrutinized. Similarly, under the specific reaction conditions, only a small amount of self-annealing of the two RNAs was found in the absence of gBP21. However, the addition of both cognate gRNA and r-gBP21 causes the formation of the expected 28 nt RNase T1 digestion product in addition to a 29 nt oligoribonucleotide that is derived from an incomplete T1 digest of the G-doublet 3′ of the anchor helix (see Figure 2A). Thus, both oligoribonucleotides provide a direct measurement of the extent of RNA duplex formation. A quantitative analysis of the experiment resulted in the following values: a protein:nucleotide ratio of 1:4 and a protein:RNA duplex ratio of 40:1. This is in agreement with the data from the semi-denaturing gel analysis described above.

Fig. 2. Verification of the formation of the anchor duplex. (A) Schematic representation of the anchor interaction between gRNA gA6-14Δ16G and pre-mRNA A6-U5. The exact base pairing scheme of the 11 bp anchor is emphasized in addition to the relevant RNase T1 hydrolysis sites on the pre-mRNA (small arrows). The nucleotide length of the expected RNase digestion fragments is given above the gRNA–pre-mRNA hybrid structure. The two 28 and 29 nt long fragments can only form as a result of the annealing reaction. (B) Autoradiogram of a representative experiment. The electrophoretic mobilities of the various RNase T1 fragments shown in (A) are given in the margin on the right. Annotations are as follows: input A6-U5, starting A6-U5 pre-mRNA; –gRNA, –gBP21, control RNase T1 digest minus gRNA and minus gBP21; –gRNA, + gBP21, control digest in the presence of 500 nM gBP21 but without gRNA; +gRNA (100 nM), –gBP21, control digest in the presence of 100 nM gRNA but without gBP21; +gRNA (10 nM), –gBP21, control digest in the presence of 10 nM gRNA and no gBP21; +gBP21, RNase T1 digest in the presence of 10 nM gRNA at varying r-gBP21 concentrations (31, 63, 125, 250 and 500 nM); +BSA, control reaction with 3.8 µM BSA instead of gBP21; +gND7-506, control sample containing gND7-506, a non-cognate gRNA, instead of gA6-14Δ16G.

Kinetics of the RNA annealing reaction

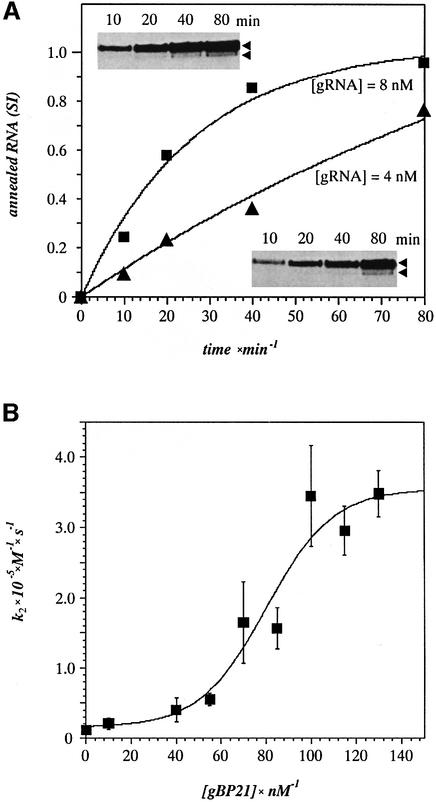

The kinetics of the RNA annealing reaction was measured using the same gRNA–pre-mRNA pair as described above and the RNase T1 protection assay. First order rate constants (k1) were derived from the time-dependent (0–80 min) accumulation of annealed RNA product measured at varying gRNA concentrations (2–128 nM) (Figure 3A). Second order rate constants were calculated based on the equation k2 = k1/[gRNA] and plotted as a function of the gBP21 concentration (Figure 3B). The analysis showed an ∼30-fold stimulation of k2 by gBP21 (350 000 M–1 s–1) when compared with the annealing reaction in the absence of the protein (12 000 M–1 s–1).

Fig. 3. Recombinant gBP21 increases the second order annealing rate constant between gRNA and cognate pre-edited mRNA. (A) Determin ation of first order rate constants k1. Relative signal intensities (SI) of the RNase T1 protected fragments (inserts) were analyzed by densitometry and plotted as a function of the annealing reaction time (t). The data were fitted to the equation SI = 1 – exp(–k1t). Two representative data sets are shown for gRNA concentrations of 4 and 8 nM. (B) Second order annealing rate constants (k2) plotted as a function of the gBP21 concentration. k2 was obtained from k1 by the equation k2 = k1/[gRNA].

Annealing of non-natural RNA substrates

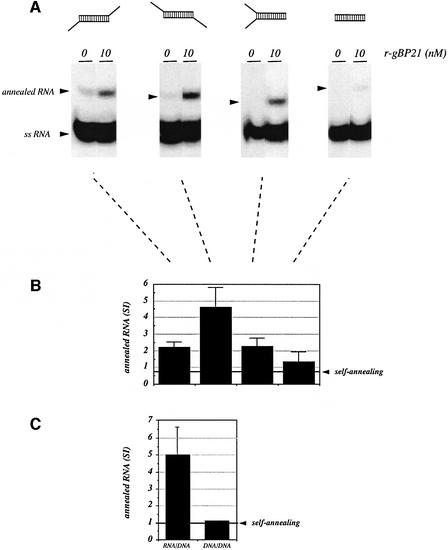

Next we addressed whether the gBP21-mediated RNA annealing reaction is specific for only cognate gRNA–pre-mRNA pairs or whether the protein is capable of annealing other complementary RNAs. We synthesized chemically a collection of short oligoribonucleotides capable of forming an identical 15 bp stem element but displaying different overhang topologies (Figure 4A, top row). Annealing was measured using the gel mobility assay in semi-denaturing polyacrylamide gels. The results are summarized in Figure 4A and B. gBP21 is capable of annealing all of the oligoribonucleotides, although not all to the same degree. The blunt end dsRNA product was formed only marginally above the value for self-annealing of the two oligoribonucleotides in the absence of protein. The dsRNA containing 3′ overhangs and the ‘y-shaped’ annealing product with both a 5′ and a 3′ overhang were formed with an intermediate activity, whereas the dsRNA with two 5′ overhangs annealed the best. This indicates that gBP21 has a general RNA annealing activity to form RNA double strands and not an RNA editing-specific activity. Lastly, we tested whether two complementary RNA and DNA oligonucleotides 18 nt in length in comparison with the identical complementary DNA strands can be annealed by gBP21. Although the protein was able to stimulate the formation of the RNA–DNA hybrid, no annealing of the DNA–DNA double strand was detected (Figure 4C).

Fig. 4. Substrate specificity of the annealing reaction. (A) Annealing reactions were performed with a panel of synthetic complementary RNA reactants (each at 10 nM) capable of forming an identical 15 bp RNA duplex but displaying different overhang topologies. The length of the single-stranded regions is 10 nt in every case and the various annealed structures are depicted above the corresponding autoradiographs. Annealing was performed in the absence and presence of 10 nM r-gBP21. RNA products were separated in 10% (w/v) polyacrylamide gels containing 1 M urea. The electrophoretic mobilities of the annealed RNA products and the input single-stranded reactants (ssRNA) are indicated by arrowheads. (B) Bar graph derived from the densitometric analysis of several experiments as described in (A). The signal intensities of the annealed RNA products were averaged from two to three independent experiments. Error bars represent standard deviations. The level of RNA–RNA ‘self-annealing’ in the absence of r-gBP21 is shown on the right. (C) gBP21-mediated annealing of RNA–DNA and DNA–DNA duplex structures. Results of annealing experiments between identical, base complementary RNA and DNA oligonucleotides of 18 nt length. The reaction was performed at 10 nM r-gBP21 with equimolar concentrations of the RNA and DNA reactants (each at 5 nM). The level of ‘self-annealing’ in the absence of r-gBP21 is given on the right. Error bars represent standard deviations.

Structural requirements for the gRNA–pre-mRNA annealing reaction

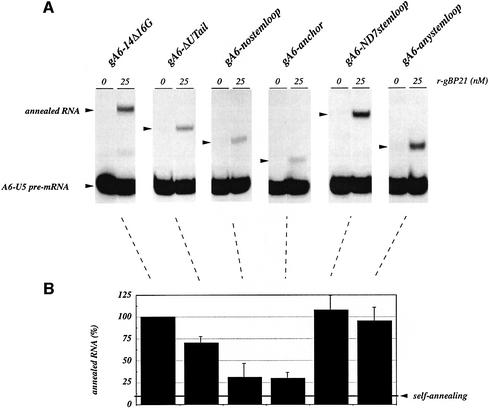

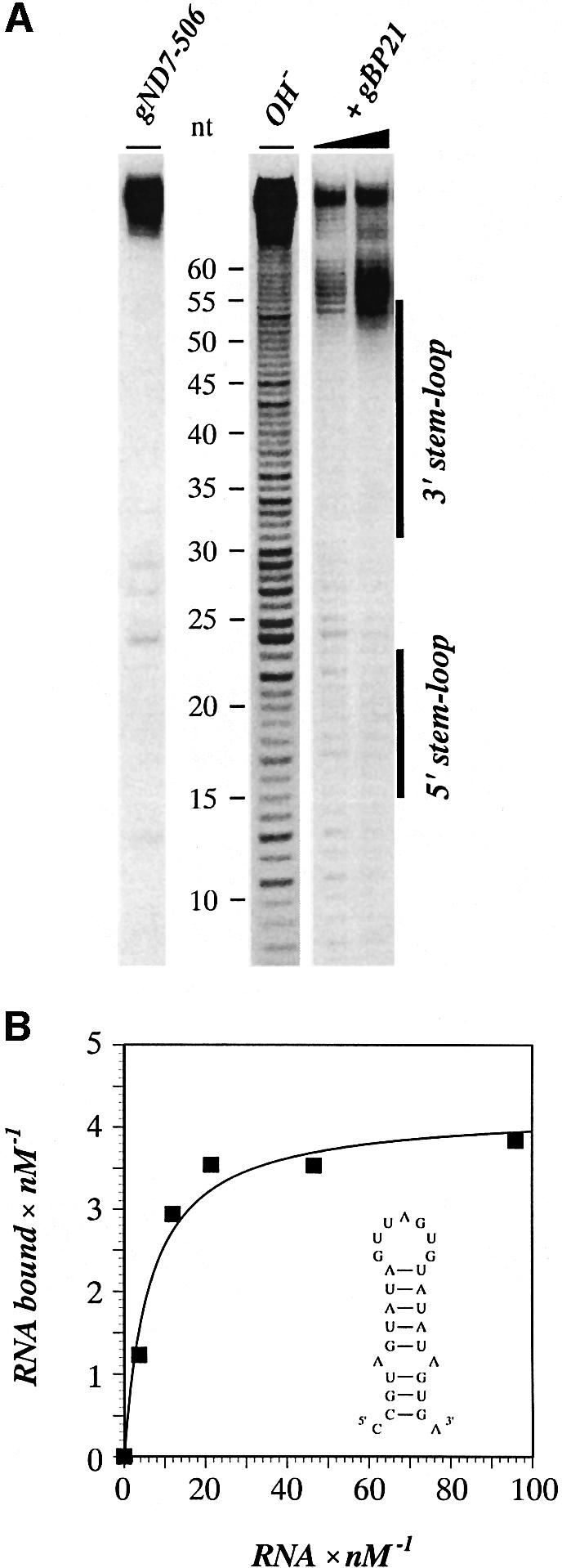

The experiment described above suggested that in addition to the complementary anchor sequences, other RNA elements might be required for the gBP21-mediated annealing reaction. In the case of the gRNA–pre-mRNA interaction, these sequence elements must be part of the gRNA molecule, since under the specific reaction conditions there is no stable interaction of gBP21 with the A6-U5 pre-mRNA in the absence of cognate gRNA (see above). Furthermore, gBP21 has been shown to bind to gRNAs with high affinity (Köller et al., 1997), suggesting that the protein probably enters the annealing reaction as a gRNA–gBP21 complex. This raises the question: which structural domain of the gRNA is required for the annealing reaction? Given the limited structural knowledge of gRNAs (Schmid et al., 1995; Hermann et al., 1997), only a few gRNA subdomains can be assayed: the 3′-terminal oligo(U)-tail, the 3′ hairpin or the anchor region itself. To test the contribution of the various domains, we created a set of truncated gRNAs that differ in one or other of these domains (Figure 5). Annealing was measured as described above using radioactively end-labeled A6-U5 pre-mRNA preparations and r-gBP21. As shown in Figure 6, all structural changes within the gRNA resulted in a reduction in the annealing activity. Deletion of the 3′ oligo(U)-tail resulted in a decrease in the activity to 70%. The further deletion of the 3′ stem–loop reduced this value to 30%, the approximate value of the anchor sequence alone. However, the annealing activity could be rescued by creating a chimeric gRNA that contained the A6-U5 anchor sequence covalently connected to the 3′ stem–loop of a non-cognate gRNA (gND7-506; Koslowsky et al., 1992). Similarly, the addition of a synthetic stem–loop element to the gA6-14Δ16G-specific anchor sequence resulted in an annealing activity comparable to the control reaction (A6-U5/gA6-14Δ16G). Thus, in the case of gRNA–pre-edited mRNA annealing, a bipartite structure is required for an efficient gBP21-mediated annealing reaction: the anchor sequence and the 3′ stem–loop element. The binding of gBP21 to the 3′ stem–loop of gRNAs is in line with previously published data (Hermann et al., 1997). This was further confirmed in a boundary experiment (Keene, 1996) (Figure 7A). From a population of gRNA-derived oligoribonucleotides of different lengths, only those RNAs containing the entire 3′ stem–loop element are capable of binding to r-gBP21. The dissociation constant (Kd) for the r-gBP21–3′ stem–loop interaction was determined using a chemically synthesized 3′ hairpin derived from the sequence of gND7-506 (Figure 7B). The derived Kd of 17 ± 2 nM further demonstrates the high affinity interaction.

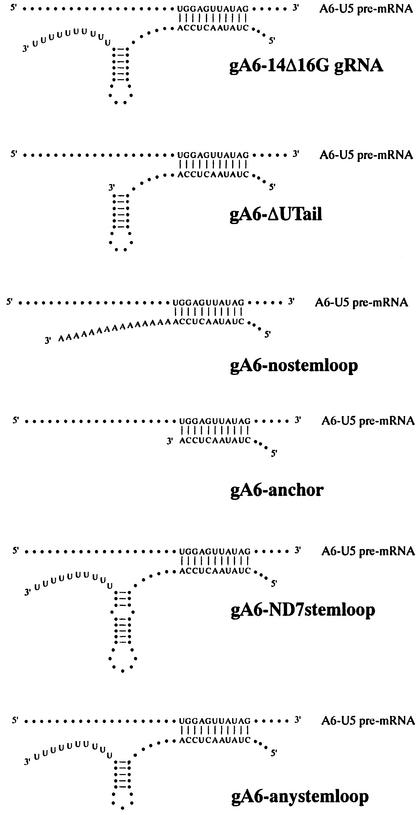

Fig. 5. Schematic representation of a panel of gRNA variants to identify the structural requirements of gRNAs required for faithful annealing. All gRNAs are derived from gA6-14Δ16G and are depicted hybridized to A6-U5, the corresponding pre-mRNA. The gRNA variants display the following features: gA6-ΔUTail, the RNA lacks the 3′ oligo(U)-tail; gA6-nostemloop, a 15-nt-long poly(A) sequence replaces the 3′ stem–loop and the oligo(U)-tail; gA6-anchor, just the anchor sequence of gA6-14Δ16G; gA6-ND7stemloop, the original 3′ stem–loop of gA6-14Δ16G is replaced by the stem–loop of gND7-506, a non-cognate gRNA; gA6-anystemloop, the original 3′ stem–loop of gA6-14Δ16G is replaced by an artificial hairpin of five consecutive G–C base pairs.

Fig. 6. Identification of required gRNA substructures for the gBP21-mediated annealing reaction. (A) Annealing reactions were performed without (0) and with r-gBP21 at a concentration of 25 nM. The various samples contain the same radiolabeled A6-U5 pre-edited mRNA (10 nM) in addition to an equimolar concentration of different gRNA variants (see annotation above the different lanes and Figure 5 for structural details). Annealed RNA products (arrowheads) were separated in semi-denaturing (1 M urea), 8% (w/v) polyacrylamide gels. (B) Bar graph derived from the densitometric analysis of two to four independent annealing experiments as shown in (A). The percentage of annealing in the different samples is given relative to the amount of annealed RNA formed between the ‘cognate’ substrates, gA6-14Δ16G gRNA and A6-U5 pre-mRNA, which was set to 100%. Error bars represent standard deviations.

Fig. 7. The 3′ stem–loop element of gND7-506 is necessary and sufficient for the high affinity interaction with recombinant gBP21. (A) Autoradiogram of a representative 3′ boundary experiment with an alkaline hydrolysis ladder of 5′-32P-labeled gND7-506 RNA (OH–). Electrophoresis was performed in a denaturing 10% (w/v) polyacryl amide gel. RNA fragments capable of binding to r-gBP21 (+gBP21) contain the entire 3′ stem–loop sequence (annotated as a black bar to the right of the autoradiogram). (B) Representative binding curve between r-gBP21 and the isolated 3′ stem–loop of gND7-506 RNA (see insert). The stability of the stem was enhanced by changing the first base pair of the stem from U/G to C/G. The amounts of bound RNA were determined in a filter binding assay and fitted to the equation [RNAbound] = n[RNAfree]/(Kd + [RNAfree]). The data represent a Kd of 17 ± 2 nM. Full-length gND7-506 binds to gBP21 with a Kd of 8 ± 2 nM.

RNA annealing activities in T.brucei mitochondrial extracts

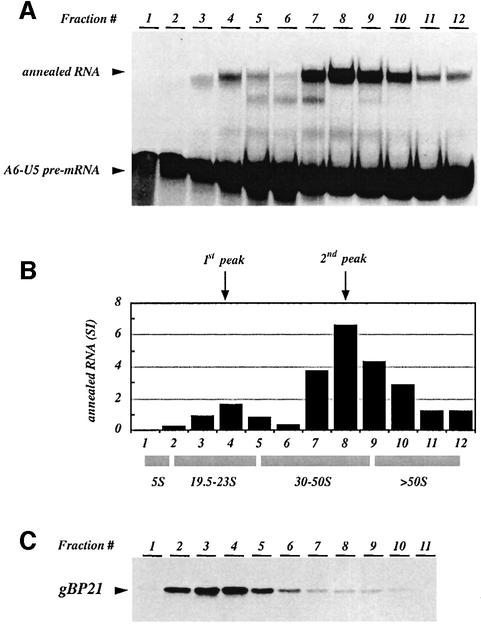

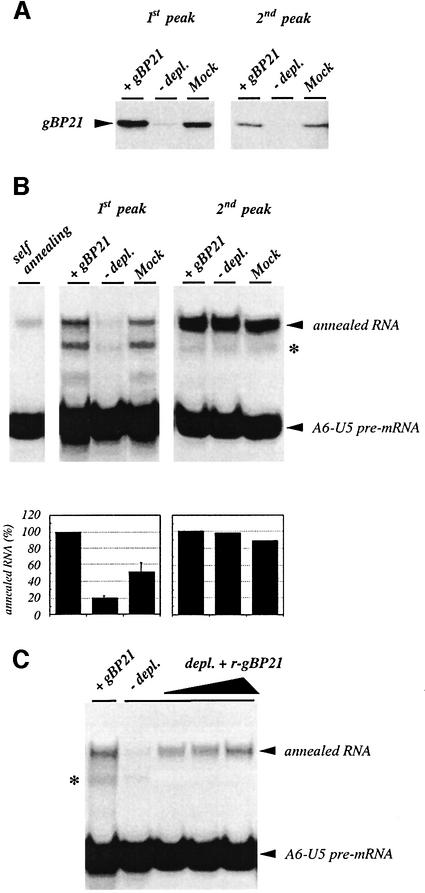

Finally, we tested whether we can detect a gBP21-mediated annealing activity within mitochondrial extracts of trypanosomes. We assayed for RNA annealing in glycerol density gradient fractions of a T.brucei mitochondrial extract (Figure 8A and B). Two activity peaks were resolved: a small peak in fractions 3–5 (∼20S) and a major peak in fractions 7–10 (∼35–50S) fading into fractions 11 and 12. The first activity peak overlaps with the presence of gBP21, which separates as a broad peak from fraction 2 to 5/6 when analyzed by western blotting (Figure 8C). Since small amounts of gBP21 could also be detected in fraction 8, we decided to deplete both peak fractions 1 and 2 of gBP21 using affinity-purified anti-gBP21 antibody preparations (Lambert et al., 1999). As shown in Figure 9A, both gradient fractions could be depleted of gBP21 below or near the level of detection. Assaying for RNA annealing in the depleted peak fractions verified a complete loss of the activity in the first peak but not in the second peak (Figure 9B). Thus, the activity in the first peak is due to a gBP21-mediated annealing reaction, whereas the activity in the second peak must be due to a different annealing activity. Final support for this scenario was gained from an ‘add-back’ experiment. The addition of r-gBP21 to a gBP21-depleted first peak fraction fully restored its RNA annealing activity (Figure 9C).

Fig. 8. Identification of RNA annealing activities in mitochondrial detergent extracts. Cleared mitochondrial lysates were separated in linear 10–35% (v/v) glycerol gradients and fractionated into 12 fractions of 1 ml. (A) Aliquots from fraction 1 (top of the gradient) to fraction 12 were tested for their annealing activity using gRNA gA6-14Δ16G and radiolabeled A6-U5 pre-mRNA (each at 10 nM) as reactants. Annealing products were separated in semi-denaturing (1 M urea), 8% (w/v) polyacrylamide gels. Arrowheads indicate the electro phoretic mobility of the A6-U5 pre-mRNA and the annealed RNA products. (B) Bar graph derived from the densitometric analysis of the experiment shown in (A). The two annealing activities were named 1st peak and 2nd peak (arrows). Apparent sedimentation coefficients were derived from marker molecules as outlined in Materials and methods. (C) Aliquots from fractions 1–11 were separated in a 12% (w/v) SDS-containing polyacrylamide gel, transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes, and probed for the presence of gBP21 using affinity-purified anti-gBP21 antibodies.

Fig. 9. Immunodepletion and r-gBP21 add-back experiments. The peak fractions of the annealing activities in the 1st peak (fraction 4) and the 2nd peak (fraction 8) were depleted of gBP21 by immunoprecipitation. (A) Western blot analysis to verify the efficiency of the gBP21-depletion reaction. +gBP21, the peak fraction before the immuno depletion; –depl., the gBP21-immunodepleted fraction; Mock, mock-depleted peak fractions. (B) Upper panel: the RNA annealing activity of the gBP21-immunodepleted peak fractions was assayed using the standard annealing assay with gRNA gA6-14Δ16G, radiolabeled A6-U5 pre-mRNA (each at 10 nM) and aliquots (5 µl) of the immunodepleted fractions (1st peak, left panel; 2nd peak, right panel). Annealed RNA products are indicated by arrowheads. Annotations are as in (A). Self-annealing, the level of RNA annealing achieved in the absence of mitochondrial extract. An asterisk represents the annealing product of A6-U5 pre-mRNA with gRNA molecules that have lost their 3′ (U)-tail due to an exonuclease activity within the extract. Lower panel: bar graph derived from the densitometric analysis of the experiment shown in the upper panel. (C) r-gBP21 add-back experiment. A gBP21-depleted fraction of peak 1 was supplemented with r-gBP21 (from left to right: 29, 57 and 143 nM) and tested for its RNA annealing activity as in (B). +gBP21 and –depl. are control samples measuring the RNA annealing activity before and after the immunodepletion, respectively.

Discussion

The mitochondrial protein gBP21 from the parasitic organism T.brucei has been characterized as a high affinity gRNA-binding protein (Köller et al., 1997). gRNAs provide a template-like function during the RNA editing process, which suggested an involvement of gBP21 during the editing reaction cycle. In support of this hypothesis, Allen et al. (1998) reported the association of gBP21 with active RNA editing complexes. Here, we demonstrate a biochemical activity for the protein. gBP21 has an RNA annealing activity, which facilitates the hybridization of gRNAs to cognate pre-mRNAs in vitro. This is indicative of an involvement during the first step of the RNA editing reaction cycle: the base pairing of nucleotides at the 5′ end of a gRNA proximal to an RNA editing site on the pre-mRNA. The resulting gRNA–pre-mRNA ‘anchor hybrid’ can be of variable length for different gRNA–pre-mRNA pairs and has been shown to be essential for the editing reaction in vitro (Blum and Simpson, 1992; Seiwert et al., 1996). Our data establish that gBP21 is capable of promoting the formation of anchor hybrids 11 and 15 bp in length. Whether shorter anchor duplexes are formed with equal characteristics remains to be tested. One of the functions of the duplex structure is to provide a recognition signal for the gRNA-dependent endonuclease to cleave the pre-mRNA at the editing site next to the hybrid helix (Adler and Hajduk, 1997).

RNA annealing activities have been identified in a variety of biochemical pathways such as transcription, translation and splicing. They can be grouped into different classes, described as ‘matchmaker’, ‘chaperone’ or ‘annealing product stabilization’ proteins (Eguchi and Tomizawa, 1990; Racker, 1991; Portman and Dreyfuss, 1994). A matchmaker polypeptide binds to the RNA reactants and brings them into close contact to facilitate the base pairing interaction. Chaperone proteins induce a conformational change in one or both RNAs that, as a consequence, mediates base pairing. Finally, annealing factors can work by stabilizing the hybridized RNA–RNA product without binding to the annealing substrates. A detailed analysis to distinguish between the three modes of action for gBP21 will be presented elsewhere.

Based on the published analysis of a gBP21 knockout trypanosome strain (Lambert et al., 1999), it seems that the annealing activity of gBP21 is not essential for the editing reaction to proceed. gBP21-minus trypanosomes are able to synthesize edited mRNAs, which might reflect the possibility that the gRNA–pre-mRNA anchor interaction can take place without a facilitating factor. Alternatively, additional annealing factors might exist and result in a molecular redundancy, as observed in other biochemical pathways (Thomas, 1993). Support for such a scenario comes from our gradient analysis, which identified a second, very prominent annealing activity within T.brucei mitochondrial extracts. Under the special conditions of the gBP21-minus background, this activity might substitute for the lack of gBP21. However, since the activity migrates at an apparent S value well above the 20S for the editing RNP (Pollard et al., 1992; Corell et al., 1996; Seiwert et al., 1996), it is unlikely that it is an integral component of the RNA editing complex itself.

Lastly, we attribute the phenotypic characteristics of the gBP21 knockout strain entirely to the RNA binding and RNA annealing activity of gBP21. In the absence of gBP21, the parasites contain reduced steady-state concentrations of mitochondrial transcripts, and furthermore are not able to differentiate from the bloodstream to the insect life cycle stage in vitro. As reviewed by Herschlag (1995), proteins that are involved in RNA folding processes often show, in addition to their specific RNA binding and folding activities, a significant level of non-specific activity. Examples are the hnRNP A1 protein, which has RNA chaperone activity and also appears to be involved in splice site selection (Bertrand and Rossi, 1994; Cáceres et al., 1994). The NC protein from HIV-1 acts as a chaperone and binds viral RNA during packaging (Tsuchihashi et al., 1993; Herschlag et al., 1994), and ribosomal protein S12, which, in addition to its function in translation, acts as an RNA chaperone in the folding of group I introns (Coetzee et al., 1994). Thus, in addition to their specific cellular functions, they also have the potential to act on non-cognate RNAs. If we assume that gBP21, next to its gRNA–pre-mRNA annealing activity, provides a similar chaperone-type function to other mitochondrial transcripts, we would expect a phenotype even if the protein is not essential for the RNA editing process. For instance, an involvement in non-specifically binding RNAs or in preventing and resolving RNA misfolding within the trypanosome mitochondrion should, in the absence of gBP21, result in high concentrations of unprotected or misfolded mitochondrial transcripts. These RNAs are likely to become rapidly degraded, which is one of the phenotypes of the gBP21-minus cells: edited, unedited and never edited mRNAs are significantly reduced (Lambert et al., 1999). However, since only mitochondrial transcripts are involved, bloodstream-stage trypanosomes should only be marginally affected. During this life cycle stage, not all mitochondrial mRNAs are processed, and the cells do not require an active mitochondrion (Priest and Hajduk, 1994). By contrast, insect-stage cells are absolutely reliant on mitochondrial function and require the expression of many mitochondrial genes. Therefore, the absence of gBP21 should cause a more severe effect in the insect life cycle stage, which is the other phenotype observed with gBP21-minus trypanosomes (Lambert et al., 1999).

In summary, we propose that gBP21 contributes to the annealing reaction of gRNAs with their cognate pre-mRNAs. The protein is, at least temporarily, associated with the editing machinery, but is not essential for the processing reaction. Aside from this specific involvement, the protein probably provides an additional, more general RNA binding and/or RNA folding function that affects a larger RNA pool within the trypanosome mitochondria.

Materials and methods

Trypanosome cell growth, preparation and fractionation of mitochondrial extracts

The insect (procyclic) life cycle stage of T.brucei strain 427 (Cross, 1975) was grown at 27°C in SDM-79 medium supplemented with 10% (v/v) heat-inactivated bovine fetal calf serum (Brun and Schönenberger, 1979). Mitochondrial vesicles were isolated by nitrogen cavitation (Hauser et al., 1996). Detergent lysates of the vesicle preparations were prepared as described by Göringer et al. (1994) using 1% (v/v) Triton X-100. Cleared mitochondrial lysates (∼10 mg) were fractionated by density centrifugation in linear 10–35% (v/v) glycerol gradients (Pollard et al., 1992). Centrifugation was performed in a Beckman SW 41 rotor at 38 000 r.p.m. for 5 h at 4°C. Twelve 1 ml fractions were collected from the top of the gradient. All fractions were tested for their in vitro uridylate deletion RNA editing activity as described by Seiwert et al. (1996). Apparent sedimentation coefficients were determined using the following markers: 5S rRNA from Escherichia coli, thyroglobulin (19.5S), E.coli 23S rRNA, E.coli 30S ribosomal subunits and E.coli 50S ribosomal subunits.

Preparation of r-gBP21

r-gBP21 was expressed in E.coli and purified by ion exchange chromatography (Köller et al., 1997). Protein preparations were routinely tested for their ability to interact with radioactive gRNAs using a nitrocellulose filter binding assay (Witherell and Uhlenbeck, 1989).

DNA and RNA synthesis and radioactive labeling

DNA oligonucleotides were synthesized by automated solid-support chemistry using O-cyanoethyl-N,N-diisopropyl-phosphoramidites. RNA molecules A6-U5, gA6-14Δ16G, gA6-ΔUTail, gA6-nostemloop, gA6-ND7stemloop, gA6-anystemloop and gND7-506 were synthesized by run-off transcription from linear DNA templates using T7 RNA polymerase following standard procedures. The RNAs were radioactively labeled using [α-32P]UTP or [α-32P]GTP in the transcription reaction. Alternatively, 32PCp and T4 RNA ligase were used to label the 3′ ends of the RNAs, or [γ-32P]ATP and T4 polynucleotide kinase for labeling the 5′ ends. The following RNAs were synthesized by solid-phase RNA synthesis using 2′-t-butyl-dimethylsilyl-protected phosphoramidites: gND7-506, 3′ hairpin, CCGUAGUAUAGUUAGUGUAUAUAGUGA; gA6-anchor, GGAUAUACUAUAACUCCA; RNAII-3′ #1, GACGGUAUGAUAUCGUUAAGGACGU; RNAII-3′ #2, CGAUAUCAUACCGUCCUGGAGUCUU; RNAII-5′ #1, UUCUGAGGUCGACGGUAU GAUAUCG; RNAII-5′ #2, UGCAGGAAUUCGAUAUCAUACCGUC; RNAII blunt 1, GACGGUAUGAUAUCG; RNAII blunt 2, CGAUAUCAUACCGUC.

The RNAs were 5′-phosphorylated using T4 polynucleotide kinase and [γ-32P]ATP. All radioactive RNA preparations were purified on urea-containing (8 M) polyacrylamide gels and renatured in 6 mM HEPES–KOH pH 7.5, 50 mM KCl, 2.1 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM Na2EDTA, 0.5 mM dithiothreitol (DTT) by heating to 70°C (2 min) followed by a slow cooling interval down to 30°C before chilling on ice.

RNA annealing assays

A standard RNA annealing reaction contained equimolar concentrations of the two RNA reactants (each at 10 nM) and varying amounts of r-gBP21 (0–250 nM). The reaction was performed in 20 µl of 6 mM HEPES–KOH pH 7.5, 50 mM KCl, 2.1 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM Na2EDTA, 0.5 mM DTT, 750 nM BSA, and only one of the RNA substrates was radioactively labeled with 32P (see above). Incubation was for 22 min at 27°C, which is the optimal growth temperature for procyclic trypanosomes. The reaction was stopped by the addition of 20 µg of proteinase K, 0.5% (w/v) SDS, 2.5 mM Na2EDTA, and further incubated for 10 min at 27°C. Annealing products were analyzed in urea-containing (1 M) 8–10% (w/v) polyacrylamide gels. Gels were fixed in 20% (v/v) methanol and 10% (v/v) acetic acid, dried and exposed to X-ray films. Band intensities were quantitated from non-saturated autoradiographs by densitometry.

In the case of the RNase T1 protection assay, 0.5 fmol of internally 32P-labeled A6-U5 pre-mRNA were mixed with r-gBP21 (0–500 nM) in 0.1 ml of annealing buffer as above. Reactions were started by the addition of 1 pmol of gRNA gA6-14Δ16G, followed by a 15 min incubation at 27°C. Annealing was terminated by adding 50 µl of RNase T1 (100 U/µl) and further incubating for 15 min at 27°C. RNA hydrolysis was stopped by the addition of 50 µl of 100 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0, 8 M urea, 1% (w/v) SDS and 40 mM Na2EDTA, followed by extraction with phenol/chloroform and precipitation with ethanol. RNA pellets were dissolved in gel loading buffer, heat denatured and separated in denaturing 20% (w/v) polyacrylamide gels. Band intensities were quantitated as described above.

Annealing kinetic

Measurements were performed in a final volume of 100 µl in 6 mM HEPES–KOH pH 7.5, 50 mM KCl, 2.1 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM Na2EDTA, 0.5 mM DTT and 0.75 µM BSA. Recombinant gBP21 (0–130 nM) was added to 0.3 nM (∼50 000 c.p.m.) internally 32P-labeled A6-U5 pre-mRNA and varying amounts of gA6-14Δ16G gRNA (0.5–128 nM). Reaction mixtures were incubated at 27°C for 10, 20, 40 and 80 min. Annealing was stopped by the addition of 50 µl of pre-warmed RNase T1 solution (1 U/µl) and incubated for 5 min. The RNase digest was terminated by the addition of 50 µl of 100 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0, 8 M urea, 1% (w/v) SDS, 40 mM Na2EDTA, followed by phenol/chloroform extraction and EtOH precipitation of the RNAs. RNA pellets were redissolved and separated by electrophoresis in urea-containing (8 M) 20% (w/v) polyacrylamide gels. Dried gels were analyzed by autoradiography and signal intensities were determined by densitometry. The time dependence of the signal intensities (SI) of the protected oligoribonucleotides at a given gRNA concentration was fitted to the equation SI = max × [1 – exp(–k1 × time)]. The derived first order rate constants (k1) were plotted against the gRNA concentrations, from which the slope of the plot equals the second order rate constant (k2). Typically, four k2 determinations for each gBP21 concentration were performed, which allowed the calculation of mean k2 values. These values were plotted against the gBP21 concentration and fitted to the equation k2 = k2(0) + a/[1 + b exp(c – [gBP21])], where k2(0) is k2 in the absence of gBP21, a is the maximal value for k2, b is the slope of the steepest part of the curve and c is the gBP21 concentration at which half-maximal k2 is reached.

Kd determination

The affinity of the interaction between gBP21 and the 3′ stem–loop of gRNA gND7-506 was measured by filter binding on nitrocellulose/cellulose acetate mixed filters as described by Witherell and Uhlenbeck (1989) and Köller et al. (1997). Dissociation constants were derived by fitting the binding data to an A1B1 complex: [RNAbound] = n[RNAfree]/(Kd + [RNAfree]), where n is the concentration of RNA binding sites and Kd is the dissociation constant of the interaction.

Boundary experiment

Hydrolysis ladders of 5′-32P-radiolabeled gRNA gND7-506 (∼106 c.p.m./pmol) were prepared by incubation in 250 mM NaHCO3 for 12 min at 96°C. Approximately 50 000 c.p.m. of the hydrolysis ladder were incubated with 1–2 nM r-gBP21. The incubation and separation conditions of bound RNA were as described for the determination of dissociation constants. Bound RNA was isolated from the nitrocellulose filter by phenol/chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation. Products were separated on denaturing (8 M urea), 10% (w/v) polyacrylamide gels and exposed to X-ray films.

Immunodepletion of mitochondrial fractions and gBP21 add-back experiments

The coupling of affinity-purified anti-gBP21 antibodies to protein A– Sepharose and the immunodepletion of annealing-active mitochondrial fractions were performed as previously described (Lambert et al., 1999). For immunoblotting, protein extracts were separated in SDS-containing polyacrylamide gels and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Membranes were blocked with 5% (w/v) BSA in PBS and probed with the antibodies. Detection was performed by enhanced chemiluminescence. gBP21-depleted mitochondrial fractions were supplemented with increasing amounts of r-gBP21 (29, 57 and 143 nM) and assayed for their annealing activity as described above.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to A.Schneider for providing the nitrogen cavitation protocol for the isolation of mitochondrial vesicles. We thank B.Schmid for the chemical synthesis of some of the oligoribonucleotides. A.S.Paul is thanked for valuable comments on the manuscript and F.Opperdoes for discussion. This work was supported in part by the Deutsche Forschungsgesellschaft (DFG) and the Human Frontier Science Program (HFSP) to H.U.G.

References

- Adler B.K. and Hajduk,S.L. (1997) Guide RNA requirement for editing-site-specific endonucleolytic cleavage of preedited mRNA by mitochondrial ribonucleoprotein particles in Trypanosoma brucei. Mol. Cell. Biol., 17, 5377–5385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen T.E., Heidmann,S., Read,R., Myler,P.J., Göringer,H.U. and Stuart,K.D. (1998) The association of gRNA-binding protein gBP21 with active editing complexes in Trypanosoma brucei. Mol. Cell. Biol., 18, 6014–6022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altmann M., Wittmer,B., Méthot,N., Sonenberg,N. and Trachsel,H. (1995) The Saccharomyces cerevisiae translation initiation factor Tif3 and its mammalian homologue, eIF-4B, have RNA annealing activity. EMBO J., 14, 3820–3827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benne R. and Speijer,D. (1998) RNA editing types and characteristics. In Grosjean,H. and Benne,R. (eds), Modification and Editing of RNA. ASM Press, Washington, DC, pp. 551–554.

- Bertrand E.L. and Rossi,J.J. (1994) Facilitation of hammerhead ribozyme catalysis by the nucleocapsid protein of HIV-1 and the heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A1. EMBO J., 13, 2904–2912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blum B. and Simpson,L. (1990) Guide RNAs in kinetoplastid mitochondria have a nonencoded 3′ oligo(U) tail involved in recognition of the preedited region. Cell, 62, 391–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blum B. and Simpson,L. (1992) Formation of guide RNA/messenger RNA chimeric molecules in vitro, the initial step of RNA editing, is dependent on an anchor sequence. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 89, 11944–11948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blum B., Bakalara,N. and Simpson,L. (1990) A model for RNA editing in kinetoplastid mitochondria: ‘Guide’ RNA molecules transcribed from maxicircle DNA provide the edited information. Cell, 60, 189–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bringaud F., Peris,M., Zen,K.H. and Simpson,L. (1995) Characterization of two nuclear-encoded protein components of mitochondrial ribonucleoprotein complexes from Leishmania tarentolae. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol., 71, 65–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brun R. and Schönenberger,M. (1979) Cultivation and in vitro cloning of procyclic culture forms of Trypanosoma brucei in a semi-defined medium. Acta Trop., 36, 289–292. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne E.M., Connell,G.J. and Simpson,L. (1996) Guide RNA-directed uridine insertion RNA editing in vitro. EMBO J., 15, 6758–6765. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cáceres J.F., Stamm,S., Helfman,D.M. and Krainer,A.R. (1994) Regulation of alternative splicing in vivo by overexpression of antagonistic splicing factors. Science, 265, 1706–1709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coetzee T., Herschlag,D. and Belfort,M. (1994) Escherichia coli proteins, including ribosomal protein S12, facilitate in vitro splicing of phage T4 introns by acting as RNA chaperones. Genes Dev., 8, 1575–1588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corell R.A. et al. (1996) Complexes from Trypanosoma brucei that exhibit deletion editing and other editing-associated properties. Mol. Cell. Biol., 16, 1410–1418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross G.A. (1975) Identification, purification and properties of clone-specific glycoprotein antigens constituting the surface coat of Trypanosoma brucei. Parasitology, 71, 393–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruz-Reyes J. and Sollner-Webb,B. (1996) Trypanosome U-deletion RNA editing involves guide RNA-directed endonuclease cleavage, terminal U exonuclease, and RNA ligase activities. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 93, 8901–8906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eguchi Y. and Tomizawa,J.-I. (1990) Complex formed by complementary RNA stem–loops and its stabilisation by a protein: function of colE1 rom protein. Cell, 60, 199–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estévez A.M. and Simpson,L. (1999) Uridine insertion/deletion RNA editing in trypanosome mitochondria—a review. Gene, 240, 247–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frech G.C. and Simpson,L. (1996) Uridine insertion into pre-edited mRNA by a mitochondrial extract from Leishmania tarentolae: stereochemical evidence for the enzyme cascade model. Mol. Cell. Biol., 16, 4584–4589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Göringer H.U., Koslowsky,D.J., Morales,T.H. and Stuart,K. (1994) The formation of mitochondrial ribonucleoprotein complexes involving guide RNA molecules in Trypanosoma brucei. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 91, 1776–1780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauser R., Pypaert,M., Hausler,T., Horn,E.K. and Schneider,A. (1996) In vitro import of proteins into mitochondria of Trypanosoma brucei and Leishmania tarentolae. J. Cell Sci., 109, 517–523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayman M.L. and Read,L.K. (1999) Trypanosoma brucei RBP16 is a mitochondrial Y-box family protein with guide RNA binding activity. J. Biol. Chem., 274, 12067–12074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermann T., Schmid,B., Heumann,H. and Göringer,H.U. (1997) A three-dimensional working model for a guide RNA from Trypanosoma brucei. Nucleic Acids Res., 25, 2311–2318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herschlag D. (1995) RNA chaperones and the RNA folding problem. J. Biol. Chem., 270, 20871–20874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herschlag D., Khosla,M., Tsuchihashi,Z. and Karpel,R.L. (1994) An RNA chaperone activity of non-specific RNA binding proteins in hammerhead ribozyme catalysis. EMBO J., 13, 2913–2924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kable M.L., Seiwert,S.D., Heidmann,S. and Stuart,K. (1996) RNA editing: a mechanism for gRNA-specified uridylate insertion into precursor mRNA. Science, 273, 1189–1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keene J.D. (1996) Randomization and selection of RNA to identify targets for RRM RNA-binding proteins and antibodies. Methods Enzymol., 267, 367–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Köller J., Nörskau,G., Paul,A.S., Stuart,K. and Göringer,H.U. (1994) Different Trypanosoma brucei guide RNA molecules associate with an identical complement of mitochondrial proteins in vitro. Nucleic Acids Res., 22, 1988–1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Köller J., Müller,U.F., Schmid,B., Missel,A., Kruft,V., Stuart,K. and Göringer,H.U. (1997) Trypanosoma brucei gBP21. An arginine-rich mitochondrial protein that binds to guide RNA with high affinity. J. Biol. Chem., 272, 3749–3757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koslowsky D.J., Riley,G.R., Feagin,J.E. and Stuart,K. (1992) Guide RNAs for transcripts with developmentally regulated RNA editing are present in both life cycle stages of Trypanosoma brucei. Mol. Cell. Biol., 12, 2043–2049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert L., Müller,U.F., Souza,A.E. and Göringer,H.U. (1999) The involvement of gRNA-binding protein gBP21 in RNA editing—an in vitro and in vivo analysis. Nucleic Acids Res., 27, 1429–1436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leegwater P., Speijer,D. and Benne,R. (1995) Identification by UV cross-linking of oligo(U)-binding proteins in mitochondria of the insect trypanosomatid Crithidia fasciculata. Eur. J. Biochem., 227, 780–786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madison-Antenucci S., Sabatini,R.S., Pollard,V.W. and Hajduk,S.L. (1998) Kinetoplastid RNA-editing-associated protein 1 (REAP-1): a novel editing complex protein with repetitive domains. EMBO J., 17, 6368–6376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Missel A., Souza,A.E., Nörskau,G. and Göringer,H.U. (1997) Disruption of a gene encoding a novel mitochondrial DEAD-box protein in Trypanosoma brucei affects edited mRNAs. Mol. Cell. Biol., 17, 4895–4903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollard V.W., Harris,M.E. and Hajduk,S. (1992) Native mRNA editing complexes from Trypanosoma brucei mitochondria. EMBO J., 11, 4429–4438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portman D.S. and Dreyfuss,G. (1994) RNA annealing activities in HeLa nuclei. EMBO J., 13, 213–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Priest J.W. and Hajduk,S.L. (1994) Developmental regulation of mitochondrial biogenesis in Trypanosoma brucei. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr., 26, 179–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Racker E. (1991) Chaperones and matchmakers: inhibitors and stimulators of protein phosphorylation. Curr. Top. Cell. Regul., 33, 127–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusché L.N., Cruz-Reyes,J., Piller,K.J. and Sollner-Webb,B. (1997) Purification of a functional enzymatic editing complex from Trypanosoma brucei mitochondria. EMBO J., 16, 4069–4081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid B., Riley,G., Stuart,K. and Göringer,H.U. (1995) The secondary structure of guide RNA molecules from Trypanosoma brucei. Nucleic Acids Res., 23, 3093–3102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seiwert S.D., Heidmann,S. and Stuart,K. (1996) Direct visualization of uridylate deletion in vitro suggests a mechanism for kinetoplastid RNA editing. Cell, 84, 831–841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas J.H. (1993) Thinking about genetic redundancy. Trends Genet., 9, 395–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuchihashi Z., Khosla,M. and Herschlag,D. (1993) Protein enhancement of hammerhead ribozyme catalysis. Science, 262, 99–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanhamme L. et al. (1998) Trypanosoma brucei TBRGG1, a mitochondrial oligo(U)-binding protein that co-localizes with an in vitro RNA editing activity. J. Biol. Chem., 273, 21825–21833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witherell G.W. and Uhlenbeck,O.C. (1989) Specific RNA binding by Qβ coat protein. Biochemistry, 28, 71–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]