Abstract

Expression of the breast and ovarian cancer susceptibility gene BRCA1 is down-regulated in sporadic breast and ovarian cancer cases. Therefore, the identification of genes involved in the regulation of BRCA1 expression might lead to new insights into the pathogenesis and treatment of these tumors. In the present study, an “inverse genomics” approach based on a randomized ribozyme gene library was applied to identify cellular genes regulating BRCA1 expression. A ribozyme gene library with randomized target recognition sequences was introduced into human ovarian cancer-derived cells stably expressing a selectable marker [enhanced green fluorescence protein (EGFP)] under the control of the BRCA1 promoter. Cells in which BRCA1 expression was upregulated by particular ribozymes were selected through their concomitant increase in EGFP expression. The cellular target gene of one ribozyme was identified to be the dominant negative transcriptional regulator Id4. Modulation of Id4 expression resulted in inversely regulated expression of BRCA1. In addition, increase in Id4 expression was associated with the ability of cells to exhibit anchorage-independent growth, demonstrating the biological relevance of this gene. Our data suggest that Id4 is a crucial gene regulating BRCA1 expression and might therefore be important for the BRCA1 regulatory pathway involved in the pathogenesis of sporadic breast and ovarian cancer.

BRCA1 has been linked to the genetic susceptibility of a majority of familial breast and ovarian cancers (1, 2). Its dominant nature as a tumor suppressor gene has been supported by the finding of frequent loss of heterozygosity (LOH) of the wild-type allele in breast tumors from mutation carriers (1, 3, 4). Although mutational loss of function of BRCA1 does not seem to contribute to sporadic cancers (5–7), BRCA1 mRNA levels are reduced or undetectable in sporadic breast and ovarian carcinomas and breast cancer cell lines (8–11). CpG methylation of the promoter may contribute to this decreased expression (12, 13), but is unlikely to be the sole mechanism (14). Thus, the regulatory pathway leading to the reduction of BRCA1 expression in sporadic breast cancer remains unclear. The identification of candidate genes in this pathway can potentially lead to the development of new therapeutic options.

Here, we report a ribozyme-library-based “inverse genomics” approach to identify cellular regulators of BRCA1 expression. Ribozymes are catalytic RNA molecules that bind to defined RNA targets based on sequence complementarity, and enzymatically cleave these RNA targets. Typically, hairpin ribozymes cleave upstream of a GUC triplet in the target sequence, thereby inhibiting the expression of the corresponding gene (15–17). A library of hairpin ribozymes with randomized substrate binding sequences could potentially cleave any RNA substrate containing a GUC. Expression of the ribozyme library in cells and subsequent selection for a given phenotype enables the identification of single ribozymes responsible for this particular phenotype. The target recognition sequence of ribozymes that reproducibly confer phenotypic changes is used to identify the corresponding target gene(s). We have recently used this approach to identify cellular genes involved in Hepatitis C virus translation mediated by its internal ribosome entry site (18). In the present application, ribozyme-library-transduced cells were selected for altered BRCA1 promoter-driven reporter gene expression. By using this approach, we identified the dominant negative transcriptional regulator Id4 as a crucial gene involved in BRCA1 regulation, and provide further insights into the biological properties of Id4 protein in the context of BRCA1 expression.

Materials and Methods

Construction of the Ribozyme Library Vector.

The Moloney retroviral genome based vector pLHPM-RzLib was constructed to contain a ribozyme (Rz) expression cassette with eight random nucleotides in helix 1 and four random nucleotides in helix 2 driven by the tRNAval promoter as described (18). To demonstrate the randomness of the Rz library insert, 50 individual bacterial colonies were analyzed by standard sequencing techniques using primer NL6H6 (5′-CTGACTCCATCGAGCCAGTGTAGAG-3′). Additionally, in vitro cleavages of several short RNA transcripts by a comparable ribozyme library confirmed the randomness (data not shown). An unrelated control ribozyme, directed against the negative strand of the 5′UTR of the Hepatitis C Virus (“CNR3”) was cloned into pLHPM and used as a control ribozyme.

Reporter Vector Construction.

To construct a BRCA1 promoter-driven enhanced green fluorescence protein (EGFP) reporter vector, a 2.9-kb fragment was amplified from a pGL2 vector containing a 3.8-kb genomic BRCA1 PstI-fragment (19) using primers BA-5Pst (5′-ATCTTTCTGCAGCTGCTGGCCCGG-3′) and BA-3Age (5′-GTGTAAACCGGTAACGCGAAGAGCAGATA-3′) and cloned into pEGFP-1 (CLONTECH). Vector pCMV-EGFP, with a CMV promoter driving EGFP gene expression, was used as a control vector. The hygromycin reporter vector was constructed by inserting the hygro/HSV-Tk fusion gene from pCMV-HyTk into pcDNA3.1(−) (Invitrogen), generating the control vector pc-HyTk (18). The BRCA1-driven HyTk plasmid pBR-HyTK was obtained by replacing the CMV promoter with a 2.9-kb genomic BRCA1 fragment (BglII–Sap I) containing the promoter region.

Construction and Characterization of Reporter Cell Clones.

PA-1 cells were transfected with pBR-EGFP or pCMV-EGFP by using a standard calcium phosphate transfection method. SK-BR-3 cells were transfected with pBR-EGFP, pCMV-EGFP, pc-HyTk, and pBR-HyTk; T47-D cells were transfected with pBR-EGFP and pCMV-EGFP by using Lipofectamine Plus (GIBCO/BRL) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Following selection with G418 (GIBCO/BRL), single colonies were functionally analyzed by flow cytometry analyzing EGFP expression (EGFP reporter cells), or characterization for their resistance against hygromycin B (hygromycin reporter cells). The integrity of the BRCA1 promoter/EGFP cassette in SK-BR-3 cells transfected with pBR-EGFP was confirmed by PCR amplification. Clones from SK-BR-3 cells transfected with pBR-HyTk were tested for the integrity of the BRCA1 promoter/HyTk cassette by genomic southern blot.

Viral Vector Production.

Retroviral particles were produced by triple transfection of the following plasmids: (i) pLHPM-Rz (containing control Rz or individual Rzs) or pLHPM-RzLib (containing the Rz library), (ii) gag-pol, and (iii) VSV-G (vesicular stomatitis virus G-protein) into CF2 cells. Plasmids gag-pol and VSV-G for retroviral production were a kind gift of Ted Friedman (University of California San Diego). Cells were transfected with TransIT-LT1 (Panvera, Madison, WI). Retroviral particles were collected every 24 h beginning on day two after addition of fresh media continuing until day five. Viral titers of G418-resistant polyclonal cell populations were estimated by using a standard titration assay performed on HT1080 cells.

Retroviral Ribozyme Library Vector or Control Vector Transduction and Fluorescence Activated Cell Sorting (FACS).

An individual clone of PA-1-based BRCA1 promoter driven EGFP reporter cells (P8EGBR3) was used for transduction with the retroviral ribozyme library or control vector. A total of 1.9 × 107 cells were transduced with retroviral ribozyme library vector and 7.4 × 106 cells with control vector at an multiplicity of infection of 1 and subsequently selected for stably transduced cells in 0.3 μg/ml Puromycin (Sigma). Following selection, cells were analyzed for their EGFP expression by flow cytometry and subsequently sorted for the highest 10% (sort 1) or the highest 3% (subsequent sorts) of the population.

Ribozyme Rescue by PCR and Ribozyme Sequence Analysis.

Genomic DNA was isolated from enriched (sorted) cells and the ribozyme genes were amplified by PCR and recloned into pLHPM to generate new retroviral particles. Individual colonies were analyzed for their ribozyme sequences.

Soft-Agar Growth.

Dishes were prepared with an underlayer of 0.6% Agar (Difco) in Iscove media (GIBCO/BRL) containing 10% FCS (HyClone). Cells were plated at 6 × 104 or 9 × 104 cells per well (9.4 cm2) in Iscove media containing 0.4% Agar and 7.8% FCS and overlaid with an upper layer of 0.6% Agar in Iscove media containing 10% FCS. Cells were refed twice per week with regular growth media containing 10% FCS, which was added onto the upper layer.

Construction of Id4 Expression Vectors.

The Id4 cDNA sequence was amplified by using primers ID4-3 (5′-TCCGAAGGGAGTGACTAGGACACCC-3′) and ID4-7 (5′-TTCTGCTCTTCCCCCTCCCTCTCTA-3′). The amplified product was cloned with the retroviral expression vector pLPCX (CLONTECH) in sense- or antisense-orientation.

Construction of Target Validation Ribozymes.

Hairpin ribozyme cleavage sites were identified within the sequence of the candidate target gene according to target recognition sequence requirements (xxxxNGTCxxxxxxxx; x representing bases complementary to helices 1 & 2): GCGCNGTCCAGGTGTG [“validation” ribozyme (VRz)1], GACCNGTCCAGCCGCG (VRz2). Ribozymes were constructed by annealing of overlapping ribozyme specific oligonucleotides (20). Double-stranded DNA was cloned into pLHPM and retroviral particles were produced.

RNA Analysis.

Total RNA was extracted from cultures grown to 80% confluency and Northern blot analysis was performed as described elsewhere (18). For quantitative real-time reverse transcription–PCR (RT-PCR) analysis, the TaqMan technology (7700 Sequence Detector, Perkin–Elmer) was applied according to the manufacturer's instructions for one-tube RT-PCR by using the standard curve method. Primers and probes (IDT) were chosen with the help of primer express Software (Perkin–Elmer)—sequences are available on request. Probes were labeled with 5′-FAM (reporter) and 3′-TAMRA (quencher). RNAs were quantified photometrically and input amounts were optimized for each amplicon, resulting in threshold values between 20 and 30 cycles. Each sample was analyzed in at least three independent assays with duplicate samples. Means of the gene of interest were normalized to GAPDH levels. Numbers are given as mean ± SEM relative to a control sample.

Hormone Treatments.

For hormone treatments, MCF-7 cells were cultured in phenol red-free MEM (GIBCO/BRL) depleted of serum for 36 h before treatment. For hormone stimulation, cells were treated with 10 nM 17-β estradiol or 10 nM progesterone (ICN Biomedicals) for 24 h and subjected to RNA analysis. Cells grown in complete media containing 10% FCS were used as controls.

Results

Generation of a Ribozyme-Library-Based Functional Selection System.

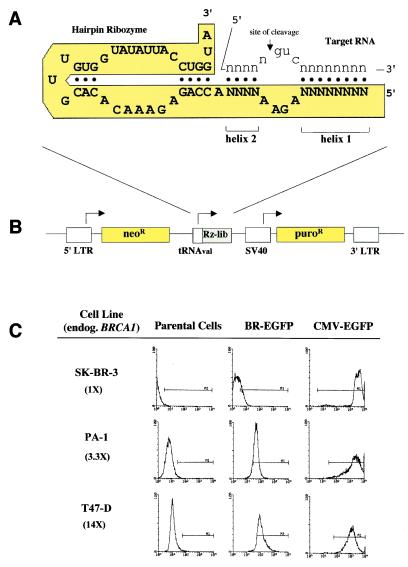

The hairpin ribozyme requires a GUC triplet within the substrate RNA and cleaves 5′ of the G residue as indicated (Fig. 1A). By randomizing target binding domains that flank the GUC triplet (Fig. 1B, eight nucleotides in helix 1, four nucleotides in helix 2 of the hairpin ribozyme), we generated a library of 1.7 × 107 (= 412) different hairpin ribozyme molecules. The library is expressed from a retroviral vector, allowing for stable introduction into reporter cells via transduction. A reporter plasmid with the BRCA1 promoter driving the expression of enhanced green fluorescence protein (EGFP) was constructed (see Figs. 6–8, which are published as supplemental data on the PNAS web site, www.pnas.org). Various reporter cell lines were generated by transfection of breast (SK-BR-3, T47-D) and ovarian (PA-1) cancer cell lines. Clonal cell populations derived from the transfected cells were analyzed for EGFP expression. The levels of EGFP expression correlated with the levels of endogenous BRCA1 RNA (Fig. 1C), supporting the hypothesis that BRCA1 expression is controlled by its transcriptional promoter. To functionally select for cells with altered BRCA1 expression, an individual reporter clone based on PA-1 cells (P8EGBR3) with an intermediate expression level of EGFP and endogenous BRCA1 was selected. P8EGBR3 reporter cells were stably transduced with retroviral vectors expressing a puromycin-resistance marker and a random ribozyme library and used for selection.

Figure 1.

The hairpin ribozyme library and gene vector. (A) Sequence and secondary structure of the hairpin ribozyme (capital letters), bound to its target RNA (lowercase letters). Both target-binding arms (helices 1 & 2) are randomized, generating a library with as many as 412 different catalytic molecules (ribozymes). (B) Schematic representation of the retroviral vector following insertion of the ribozyme library DNA template. Ribozyme expression is driven by the tRNAval promoter. (C) Flow cytometry for EGFP of SK-BR-3, PA-1, and T47-D cells. Numbers in parentheses indicate the relative expression levels of endogenous BRCA1. Analysis of untransfected control cells (parental cells) and dilution clones from cells, transfected with pBR-EGFP (BR-EGFP) or with pCMV-EGFP (CMV-EGFP).

Selection of Ribozyme-Expressing Cells with Increased BRCA1 Expression.

Following puromycin selection, cells transduced with the ribozyme vector library or a control vector (as well as untransduced cells) were subjected to several rounds of FACS. Generally, to enrich for populations with increased EGFP expression, the highest three to ten percent of cells were sorted. Starting with the third sort, increasing numbers of cells with higher EGFP expression were detected in ribozyme library-transduced cells (Fig. 2A), but not in sorted populations of untransduced or control vector transduced cells. After five sorts, the majority of the sorted populations derived from library-transduced cells shifted toward a higher EGFP expression level compared with the controls and a greater than nine-fold increase in mean fluorescence intensity was observed (Fig. 2A). RNA analysis of the ribozyme-library-transduced cells confirmed the increase of EGFP RNA as well as endogenous BRCA1 mRNA compared with the controls (Fig. 2B). These results demonstrate that the selected ribozymes conferred an increase of BRCA1 promoter-mediated gene expression, resulting in elevated levels of both EGFP and endogenous BRCA1. PCR amplification and sequence analysis of the ribozyme genes from the shifted populations revealed the predominance of several candidate ribozymes (data not shown). The pool of enriched candidate ribozyme vectors was reintroduced into new P8EGBR3 reporter cells for further rounds of FACS-based selection and ribozyme rescue.

Figure 2.

Selection of ribozymes that up-regulate the BRCA1 promoter. (A) FACS-selection of P8EGBR3 cells (untransduced, control vector, or ribozyme-library-transduced) for cells with an increase in EGFP expression. Rz library-transduced cells show a peak on sort #4 (*) and a shift of the majority of the population on sort #5 (+), whereas control vector or untransduced cells remain unchanged throughout the experiment. MFI, mean fluorescence intensity of cell population, given in percent of control vector transduced cells. (B) Quantitative real-time RT-PCR analysis of EGFP and endogenous BRCA1 RNA normalized to GAPDH RNA after sort #5 in cells transduced with control vector or ribozyme library. Numbers are given as relative RNA levels in percent compared with control vector transduced cells (mean ± SEM).

Identification of a Single Ribozyme to Increase BRCA1 Expression.

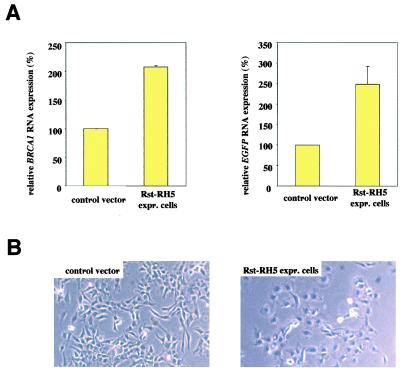

After several rounds of selection, a single predominant ribozyme (named Rst-RH5) was found in the population of shifted cells. Again, RNA analysis demonstrated an increase in EGFP and BRCA1 RNA, confirming the involvement of this particular ribozyme in the regulation of the BRCA1 promoter (Fig. 3A). Interestingly, the sorted cells also exhibited morphological changes toward a flatter, larger phenotype with a larger cytoplasm resembling normal epithelium. This was not observed with sorted cells derived from control vector transduction (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3.

BRCA1 expression and morphology of selected cells expressing Rst-RH5. Cells transduced with an enriched ribozyme library were subjected to several rounds of selection for high EGFP expression and ribozyme rescue resulting in a population expressing Rst-RH5 as the sole predominant ribozyme. These cells were examined for BRCA1 expression and cell morphology. (A) Quantitative real-time RT-PCR analysis of EGFP and endogenous BRCA1 RNA normalized to GAPDH in control vector-transduced or Rst-RH5 expressing cells. Numbers are given as relative RNA levels in percent compared with control vector transduced cells (mean ± SEM). (B) Morphology in monolayer culture of Rst-RH5 expressing cells compared with control vector transduced cells.

Additionally, anchorage-independent growth was markedly reduced in cells expressing Rst-RH5 in comparison with control vector transduced cells (Table 1), demonstrating suppression of an in vitro indicator of tumorigenicity.

Table 1.

Anchorage-independent growth of Rst-RH5-expressing cells

| Population | Number of

colonies* at plating density

|

|

|---|---|---|

| 6 × 104 cells per well | 9 × 104 cells per well | |

| Control Rz | 23.2, 18.7 | 28, 28.7 |

| Rst-RH5 | 0, 0 | 0, 3.7 |

Numbers are means of independent assays (performed in triplicate). Values are given for two experiments.

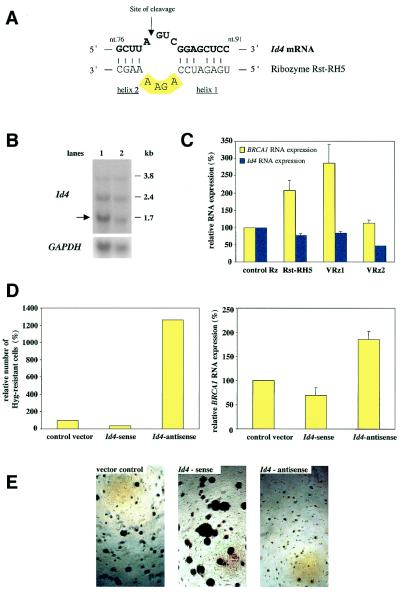

Identification and Confirmation of Id4 as a BRCA1-Regulating Gene.

By using the 16 nucleotides of sequence information derived from the Rst-RH5 binding sequences and the cleavage site (8 nt in helix 1, 4 nt in helix 2 and NGUC) to search various databases (e.g., National Center for Biotechnology Information non-redundant and EST databases), we failed to identify perfectly matching candidate genes. However, under less stringent search conditions, we identified Id4 as a potential target. The two mismatches in helix 1 between Rst-RH5 and Id4 mRNA (Fig. 4A) are expected to have a minimal effect on ribozyme binding or cleavage activity (21). In fact, in vitro assays confirmed cleavage activity of Rst-RH5 on synthetic Id4 substrate RNA (data not shown). Id4 belongs to a group of four related helix–loop–helix (HLH) proteins, which are dominant negative regulators of transcription (22, 23). The mRNA sequences to Id1, -2, or -3 have no similarities with Rst-RH5. Northern blotting analysis of parental P8EGBR3 and ribozyme-library- or control vector transduced cells after five rounds of FACS-sorting showed three Id4 RNA transcripts (Fig. 4B) apparently generated by alternative usage of polyadenylation sites (24, 25). Quantification by phosphoimager revealed a 40% reduction in the major Id4 transcript (1.7 kb, indicated by an arrow in Fig. 4B) normalized to GAPDH RNA in library-transduced cells compared with the controls. Comparable reduction in endogenous Id4 mRNA was also found in single cell clones of library-transduced cells expressing Rz Rst-RH5 (data not shown).

Figure 4.

Identification and validation of Id4 as a negative regulator of the BRCA1 promoter. (A) Schematic illustration of the predicted binding of Rst-RH5 to Id4 mRNA (numbering of Id4 nucleotides according to GenBank accession no. NM 001546). (B) Northern analysis for Id4 RNA in ribozyme-library- (lane 2) or control vector (lane 1)-transduced P8EGBR3 cells after sort #5 (compare with Fig. 2). Different messages result from alternative polyadenylation. The major message is indicated (arrow). (C) Effects of Rst-RH5 and two validation ribozymes (VRz1 or VRz2) on endogenous BRCA1 and Id4 expression measured by quantitative real-time RT-PCR. Expression of BRCA1 or Id4 mRNA was normalized to GAPDH mRNA. Numbers are given as relative RNA levels in percent compared with the control ribozyme (mean ± SEM). (D) The Hygromycin B resistance assay. Quantitative analysis of cell survival and of endogenous BRCA1 expression (measured by quantitative real-time RT-PCR and normalized to GAPDH message) in control vector-, Id4-sense-, or Id4-antisense-transduced cells after phenotypic selection of Hygromycin B reporter cells with Hygromycin B. Numbers are given in percent compared with control vector (mean ± SEM). (E) Anchorage-independent growth of P8EGBR3 cells transduced with control vector, Id4-sense, or Id4-antisense expression vectors.

To confirm Id4 as a target gene of Rst-RH5, we further examined the effects of VRz directed against additional sites within the Id4 mRNA, located either within the coding region (VRz2) or the 3′UTR (VRz1) of Id4. Again, these potential ribozyme cleavage sites are not conserved within the RNA transcripts of the other Id genes. P8EGBR3 reporter cells were stably transduced with viral vectors containing VRz1, VRz2, Rst-RH5 or a control ribozyme and cellular RNAs were analyzed for endogenous BRCA1 expression. A significant increase in BRCA1 expression relative to control ribozyme-transduced cells was observed in cells expressing either Rst-RH5 or Id4-specific ribozymes (Fig. 4C). Furthermore, expression of Id4 RNA in cells transduced with these ribozyme vectors was inversely correlated to levels of BRCA1 expression (Fig. 4C).

BRCA1 regulation by Id4 was also confirmed in a second independent reporter system, with SK-BR-3 based reporter cells expressing the hygromycin B phosphotransferase gene under control of the BRCA1 promoter. Following stable transduction with Id4-sense and -antisense expression vectors or a control vector, cells were subjected to hygromycin B selection. SK-BR-3 cells constitutively express very low levels of BRCA1, suggesting poor activity of the BRCA1 promoter in these cells. Consistent with this, these reporter cells are sensitive to increasing dosages of hygromycin B. Cells transfected with an Id4-antisense vector preferentially survived under hygromycin B selection, compared with Id4-sense vector or control vector transduced cells (Fig. 4D), suggesting that in this reporter system, suppression of Id4 significantly increased BRCA1-driven hygromycin B phosphotransferase gene expression. Additionally, hygromycin B-selected Id4-antisense reporter cells showed a more than two-fold increase in endogenous BRCA1 expression compared with Id4-sense expressing cells (Fig. 4D).

To further investigate the biological relevance of this regulation, we examined the effects of Id4-sense and -antisense overexpression on anchorage-independent growth in P8EGBR3 cells. Previous findings suggested that decreased BRCA1 expression is associated with increased ability of cells to grow in soft agar and vice versa (9, 26–28). Therefore, Id4-mediated modulation of BRCA1 expression should result in a corresponding phenotypic change. As expected, cells expressing sense-Id4 demonstrated a significant increase in anchorage-independent growth in comparison with antisense-Id4 expressing cells (Fig. 4E). Transduction with viral vectors expressing anti-Id4 ribozymes also significantly decreased colony formation in soft agar (data not shown).

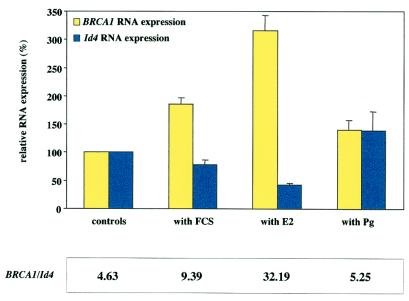

Estrogen-Dependent Regulation of BRCA1 and Id4 Expression.

Sex hormones are known to stimulate cells through specific receptors. Furthermore, they have been shown to regulate BRCA1 expression in cell culture (29). MCF-7 breast cancer cells contain detectable levels of the estrogen receptor, but not the progesterone receptor. Consequently, expression of BRCA1 in these cells is responsive to estrogen, but not to progesterone. As expected, we observed an increase in BRCA1 expression in cells treated with 17-β estradiol, but not in cells treated with progesterone (Fig. 5). In contrast, Id4 RNA expression was reduced more than two-fold following estrogen stimulation, but did not change in progesterone-stimulated cells. The ratio of BRCA1 RNA to Id4 RNA increased seven-fold by stimulation with estrogen. Treatment of cells with FCS had an intermediate effect.

Figure 5.

Hormone stimulation of MCF-7 cells. Cells were grown in phenol-red free media without serum for 36 h before selective stimulation with 10 nM β-estradiol (E2) or 10 nM progesterone (Pg), or no stimulation (controls). Cells grown in media containing 10% FCS were used as controls (with FCS). Following stimulation, cellular RNAs were harvested and analyzed for endogenous BRCA1 and Id4 expression levels by using quantitative real-time RT-PCR. Numbers are given as percent (mean ± SEM) in comparison to cells grown without serum.

Discussion

BRCA1 expression has been shown to be regulated by several regions within the putative BRCA1 promoter (30–32), and by different cellular factors, including the Rb-E2F pathway (33), the Brn-3b POU family transcription factor (34), and the GA-binding protein α/β (35). In this study, we have used a ribozyme-based selection system to target and identify a BRCA1-regulating gene via a BRCA1 promoter-driven reporter system. This approach allows us to functionally select ribozymes that target key cellular factors involved in a pathway that affects a particular phenotype. Therefore, in this system, we expect to identify not only genes directly regulating the BRCA1 promoter, but also any biologically relevant upstream regulators.

By using this approach, we were able to identify and analyze individual candidate ribozymes with the help of a FACS-based reporter system. We were particularly interested in a ribozyme, Rst-RH5, which not only conferred an increase in expression of both BRCA1 promoter driven reporter gene and endogenous BRCA1, but also substantially changed the biological properties of the transduced cells. By using sequence information from the target-binding arms of Rst-RH5, we identified the corresponding target gene to be the HLH transcriptional regulator Id4.

Id proteins are dominant negative inhibitors of DNA binding. They contain functional HLH dimerization motifs, but lack the DNA-binding basic region found in the basic HLH (bHLH) proteins, thereby inhibiting DNA binding of bHLH transcription factors (22, 23, 36). Furthermore, for some Id proteins, interactions with non-HLH proteins have been described, such as retinoblastoma protein (37), MIDA1 (38), and Ets-domain transcription factors (39). Interestingly, the BRCA1 promoter region contains several E-box elements, which are DNA recognition sequences of bHLH proteins (40, 41). In addition, the minimal BRCA1 promoter region contains a potential binding site for ETS protein transcription factors (30) and recent data suggest that the ETS protein GABPα/β contributes to transcriptional activation of BRCA1 (35). We have identified Id4 as a gene functionally important for BRCA1 regulation. However, Id4 might be involved at any point along the upstream regulatory pathway of BRCA1 regulation. Although bHLH proteins binding to the E-box elements of the BRCA1 promoter or GABPα/β proteins could resemble potential dimerization partners of Id4, the precise function of Id4 within the BRCA1 regulatory pathway remains to be defined.

Our experiments with Id4-sense and -antisense expression vectors as well as ribozymes directed against additional cleavage sites within the Id4 mRNA confirmed the significance of Id4-mediated regulation of BRCA1 expression via its promoter: Id4 modulated BRCA1 promoter-driven reporter gene expression as well as endogenous BRCA1 expression. In addition, our findings demonstrate that overexpression of Id4 in target cells causes an increase in their in vitro tumorigenic potential as shown by anchorage-independent growth, whereas a “knock-down” of the gene by full-length antisense expression or by Id4-specific ribozymes results in the reverse phenotype. Although the reduction of Id4 mRNA by Id4-targeting ribozymes was modest (20–40%), it is possible that cells expressing drastically reduced Id4 mRNA (and greatly increased levels of BRCA1) may be selected against, because BRCA1 is known to be associated with decreased cell proliferation and apoptosis (26, 42). Because the ribozyme library approach is based on selection of cells with a particular altered phenotype rather than the degree of target gene knock-down, it allows us to identify cellular factors that exhibit critical thresholds for different biological functions. Previous studies using this approach showed that similar levels of target gene knock-down led to significant biological effects, namely, inhibition of HCV protein translation and increased anchorage independent cell growth respectively (18, 43).

Our data support previous observations that Id proteins function as positive regulators of cell growth and negative regulators of cell differentiation in various tissues (44–48), including mammary epithelial cells (49–51). In the latter studies, Id1 protein suppressed mammary epithelial cell differentiation and its expression correlated with an aggressive phenotype (51). Moreover, Id expression can be modulated by hormones (51) and Id proteins themselves can influence hormone-induced promoter activity (52). Interestingly, previous studies have also demonstrated BRCA1 expression to be responsive to hormone stimulation (29, 53). Our observation that Id4 and BRCA1 mRNA levels were inversely correlated in hormone treated MCF-7 cells suggests that Id4 may be involved in hormone-dependent regulation of BRCA1 expression.

In summary, we have developed a ribozyme-mediated functional approach to identify genes regulating BRCA1 expression. By using this approach we were able to identify ribozymes that conferred a phenotype characterized by an increase in BRCA1 expression. The corresponding target gene of one particular ribozyme was identified to be the dominant negative transcriptional regulator Id4. Further characterization of Id4 function demonstrated its role in regulating BRCA1 expression in the context of breast and ovarian cancer. Work is in progress to identify the gene targets of other selected ribozymes, which may reveal additional genes in the BRCA1 regulatory pathway. The identification of cellular genes involved in BRCA1 regulation might facilitate the development of new therapeutic options for sporadic breast and ovarian cancer.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Richard Tritz for performing in vitro cleavage assays and Tania Wilkinson, Armando Ayala, Eric Alspaugh, and Ivonne Strenger for excellent technical assistance. C.B. was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (Be 1980/1-1).

Abbreviations

- EGFP

enhanced green fluorescence protein

- FACS

fluorescence activated cell sorting

- RT-PCR

reverse transcription–PCR

- HLH

helix–loop–helix

- Rz

ribozyme

- VRz

“validation” ribozyme

Footnotes

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

References

- 1.Miki Y, Swensen J, Shattuck-Eidens D, Futreal P A, Harshman K, Tavtigian S, Liu Q, Cochran C, Bennett L M, Ding W, et al. Science. 1994;266:66–71. doi: 10.1126/science.7545954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Szabo C I, King M C. Hum Mol Genet. 1995;4:1811–1817. doi: 10.1093/hmg/4.suppl_1.1811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Friedman L S, Ostermeyer E A, Szabo C I, Dowd P, Lynch E D, Rowell S E, King M C. Nat Genet. 1994;8:399–404. doi: 10.1038/ng1294-399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith S A, Easton D F, Evans D G, Ponder B A. Nat Genet. 1992;2:128–131. doi: 10.1038/ng1092-128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Futreal P A, Liu Q, Shattuck-Eidens D, Cochran C, Harshman K, Tavtigian S, Bennett L M, Haugen-Strano A, Swensen J, Miki Y, et al. Science. 1994;266:120–122. doi: 10.1126/science.7939630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hosking L, Trowsdale J, Nicolai H, Solomon E, Foulkes W, Stamp G, Signer E, Jeffreys A. Nat Genet. 1995;9:343–344. doi: 10.1038/ng0495-343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Merajver S D, Pham T M, Caduff R F, Chen M, Poy E L, Cooney K A, Weber B L, Collins F S, Johnston C, Frank T S. Nat Genet. 1995;9:439–443. doi: 10.1038/ng0495-439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sourvinos G, Spandidos D A. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;245:75–80. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.8379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thompson M E, Jensen R A, Obermiller P S, Page D L, Holt J T. Nat Genet. 1995;9:444–450. doi: 10.1038/ng0495-444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wilson C A, Ramos L, Villasenor M R, Anders K H, Press M F, Clarke K, Karlan B, Chen J J, Scully R, Livingston D, et al. Nat Genet. 1999;21:236–240. doi: 10.1038/6029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yoshikawa K, Honda K, Inamoto T, Shinohara H, Yamauchi A, Suga K, Okuyama T, Shimada T, Kodama H, Noguchi S, et al. Clin Cancer Res. 1999;5:1249–1261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dobrovic A, Simpfendorfer D. Cancer Res. 1997;57:3347–3350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mancini D N, Rodenhiser D I, Ainsworth P J, O'Malley F P, Singh S M, Xing W, Archer T K. Oncogene. 1998;16:1161–1169. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Catteau A, Harris W H, Xu C F, Solomon E. Oncogene. 1999;18:1957–1965. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beger C, Krüger M, Wong-Staal F. In: Gene Therapy of Cancer. Lattine E, Gerson S L, editors. San Diego: Academic; 1998. pp. 139–152. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haseloff J, Gerlach W L. Nature (London) 1988;334:585–591. doi: 10.1038/334585a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marschall P, Thomson J B, Eckstein F. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 1994;14:523–538. doi: 10.1007/BF02088835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krüger M, Beger C, Li Q-X, Welch P J, Tritz R, Leavitt M, Barber J R, Wong-Staal F. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:8566–8571. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.15.8566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smith T M, Lee M K, Szabo C I, Jerome N, McEuen M, Taylor M, Hood L, King M C. Genome Res. 1996;6:1029–1049. doi: 10.1101/gr.6.11.1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Welch P J, Tritz R, Yei S, Barber J, Yu M. Gene Ther. 1997;4:736–743. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3300441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yu Q, Pecchia D B, Kingsley S L, Heckman J E, Burke J M. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:23524–23533. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.36.23524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Benezra R, Davis R L, Lockshon D, Turner D L, Weintraub H. Cell. 1990;61:49–59. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90214-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Norton J D, Deed R W, Craggs G, Sablitzky F. Trends Cell Biol. 1998;8:58–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pagliuca A, Bartoli P C, Saccone S, Della Valle G, Lania L. Genomics. 1995;27:200–203. doi: 10.1006/geno.1995.1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van Cruchten I, Cinato E, Fox M, King E R, Newton J S, Riechmann V, Sablitzky F. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1443:55–64. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4781(98)00196-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aprelikova O N, Fang B S, Meissner E G, Cotter S, Campbell M, Kuthiala A, Bessho M, Jensen R A, Liu E T. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:11866–11871. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.21.11866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Holt J T, Thompson M E, Szabo C, Robinson-Benion C, Arteaga C L, King M C, Jensen R A. Nat Genet. 1996;12:298–302. doi: 10.1038/ng0396-298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rao V N, Shao N, Ahmad M, Reddy E S. Oncogene. 1996;12:523–528. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marks J R, Huper G, Vaughn J P, Davis P L, Norris J, McDonnell D P, Wiseman R W, Futreal P A, Iglehart J D. Oncogene. 1997;14:115–121. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1200808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Suen T C, Goss P E. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:31297–31304. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.44.31297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thakur S, Croce C M. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:8837–8843. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.13.8837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xu C F, Chambers J A, Solomon E. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:20994–20997. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.34.20994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang A, Schneider-Broussard R, Kumar A P, MacLeod M C, Johnson D G. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:4532–4536. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.6.4532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Budhram-Mahadeo V, Ndisang D, Ward T, Weber B L, Latchman D S. Oncogene. 1999;18:6684–6691. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Atlas E, Stramwasser M, Whiskin K, Mueller C R. Oncogene. 2000;19:1933–1940. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Christy B A, Sanders L K, Lau L F, Copeland N G, Jenkins N A, Nathans D. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:1815–1819. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.5.1815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Iavarone A, Garg P, Lasorella A, Hsu J, Israel M A. Genes Dev. 1994;8:1270–1284. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.11.1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shoji W, Inoue T, Yamamoto T, Obinata M. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:24818–24825. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.42.24818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yates P R, Atherton G T, Deed R W, Norton J D, Sharrocks A D. EMBO J. 1999;18:968–976. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.4.968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lassar A B, Buskin J N, Lockshon D, Davis R L, Apone S, Hauschka S D, Weintraub H. Cell. 1989;58:823–831. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90935-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tietze K, Oellers N, Knust E. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:6152–6156. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.13.6152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Harkin D P, Bean J M, Miklos D, Song Y H, Truong V B, Englert C, Christians F C, Ellisen L W, Maheswaran S, Oliner J D, et al. Cell. 1999;97:575–586. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80769-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Welch P J, Marcusson E G, Li Q X, Beger C, Kruger M, Zhou C, Leavitt M, Wong-Staal F, Barber J R. Genomics. 2000;66:274–283. doi: 10.1006/geno.2000.6230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Alani R M, Hasskarl J, Grace M, Hernandez M C, Israel M A, Munger K. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:9637–9641. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.17.9637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jaleco A C, Stegmann A P, Heemskerk M H, Couwenberg F, Bakker A Q, Weijer K, Spits H. Blood. 1999;94:2637–2646. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jen Y, Weintraub H, Benezra R. Genes Dev. 1992;6:1466–1479. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.8.1466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Morrow M A, Mayer E W, Perez C A, Adlam M, Siu G. Mol Immunol. 1999;36:491–503. doi: 10.1016/s0161-5890(99)00071-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shoji W, Yamamoto T, Obinata M. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:5078–5084. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Desprez P Y, Hara E, Bissell M J, Campisi J. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:3398–3404. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.6.3398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Desprez P Y, Lin C Q, Thomasset N, Sympson C J, Bissell M J, Campisi J. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:4577–4588. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.8.4577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lin C Q, Singh J, Murata K, Itahana Y, Parrinello S, Liang S H, Gillett C E, Campisi J, Desprez P Y. Cancer Res. 2000;60:1332–1340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chaudhary J, Skinner M K. Mol Endocrinol. 1999;13:774–786. doi: 10.1210/mend.13.5.0271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gudas J M, Nguyen H, Li T, Cowan K H. Cancer Res. 1995;55:4561–4565. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.