Abstract

CAF-1, Hir proteins, and Asf1 are histone H3/H4 binding proteins important for chromatin-mediated transcriptional silencing. We explored genetic and physical interactions between these proteins and S-phase/DNA damage checkpoint kinases in the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Although cells lacking checkpoint kinase Mec1 do not display defects in telomeric gene silencing, silencing was dramatically reduced in cells lacking both Mec1 and the Cac1 subunit of CAF-1. Silencing was restored in cac1Δ and cac1Δ mec1Δ cells upon deletion of Rad53, the kinase downstream of Mec1. Restoration of silencing to cac1Δ cells required both Hir1 and Asf1, suggesting that Mec1 counteracts functional sequestration of the Asf1/Hir1 complex by Rad53. Consistent with this idea, the degree of suppression of silencing defects by rad53 alleles correlated with effects on Asf1 binding. Furthermore, deletion of the Dun1 kinase, a downstream target of Rad53, also suppressed the silencing defects of cac1Δ cells and reduced the levels of Asf1 associated with Rad53 in vivo. Loss of Mec1 and Rad53 did not alter telomere lengths or Asf1 protein levels, nuclear localization, or chromosome association. We conclude that the Mec1 and Dun1 checkpoint kinases regulate the Asf1-Rad53 interaction and therefore affect the activity of the Asf1/Hir complex in vivo.

THE DNA of all eukaryotic genomes is packaged into a nucleoprotein complex called chromatin. Chromatin is essential for compacting genomic DNA and plays a primary role in governing accessibility for transcription, replication, and recombination. The fundamental repeating unit of chromatin is the nucleosome, containing an octamer of histone proteins, two each of H2A, H2B, H3, and H4, around which 146 bp of DNA wraps 1.7 times (Luger et al. 1997). Nucleosome assembly during S phase occurs in a manner that is tightly linked to DNA replication (Lucchini and Sogo 1995). However, replication-independent nucleosome assembly mechanisms also exist to ensure replacement of histones outside of S phase during gene transcription and DNA repair (Ahmad and Henikoff 2002; McKittrick et al. 2004). These processes are mediated by multiple specialized histone chaperones (reviewed in Franco and Kaufman 2004).

The best-characterized DNA replication-linked histone deposition complex is chromatin assembly factor-1 (CAF-1). CAF-1 is a heterotrimeric protein complex that is both structurally and functionally conserved among all eukaryotes (Kaufman et al. 1995, 1997; Tyler et al. 1996, 2001; Kaya et al. 2001; Quivy et al. 2001). In human cells, CAF-1 localizes to sites of DNA synthesis during S phase and also at sites of DNA repair outside of S phase (Krude 1995; Martini et al. 1998; Green and Almouzni 2003). Inhibition or degradation of human CAF-1 results in impaired S-phase progression, suggesting that CAF-1 helps to coordinate DNA synthesis and chromatin formation (Hoek and Stillman 2003; Ye et al. 2003). Consistent with this idea, the large subunit of CAF-1 from all organisms binds to PCNA, the processivity factor for DNA polymerases that is required for both DNA replication and repair (Shibahara and Stillman 1999; Moggs et al. 2000; Zhang et al. 2000; Krawitz et al. 2002).

In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, the CAC1-3 genes encode the subunits of CAF-1. Budding yeast cells lacking either one or all of CAC genes display normal kinetics of cell cycle progression (Sharp et al. 2002), yet have reduced chromatin-mediated gene silencing at the telomeres, at the silent mating loci, and at ribosomal DNA (Enomoto et al. 1997; Kaufman et al. 1997; Monson et al. 1997; Enomoto and Berman 1998; Smith et al. 1999). CAF-1 also contributes to the proper structure and function of centromeric chromatin in budding yeast (Sharp et al. 2002, 2003). Together, these data indicate a conserved role for CAF-1 in chromatin formation.

In yeast, the histone regulatory (HIR) genes, HIR1, HIR2, HIR3, and HPC2 (Osley and Lycan 1987; Xu et al. 1992), encode proteins that compose a histone deposition pathway that functionally overlaps CAF-1 (Kaufman et al. 1998). Although mutations in yeast HIR genes alone do not alter silencing at telomeres and the silent mating loci, cacΔ hirΔ double-mutant cells display a synergistic reduction of position-dependent gene silencing at both these loci (Kaufman et al. 1998; Qian et al. 1998). Consistent with these genetic data, biochemical analyses of vertebrate Hir protein homologs also indicate a role in histone deposition. HIRA, the Xenopus homolog of the HIR1/HIR2 genes, exhibits replication-independent histone deposition activity (Ray-Gallet et al. 2002), and the human HIRA protein is associated with the constitutively expressed histone H3.3 isoform, which is deposited into chromatin in times outside of S phase (Ahmad and Henikoff 2002; Tagami et al. 2004). Thus, all eukaryotes have multiple histone deposition proteins, some linked to DNA synthesis (CAF-1) and others that operate in a non-replication-linked manner (Hir proteins).

Genetic and biochemical data from multiple organisms indicate that the contribution of Hir proteins to chromatin assembly requires the highly conserved histone H3/H4-binding protein Asf1 (Sharp et al. 2001; Sutton et al. 2001; Daganzo et al. 2003). Asf1 binds to the Hir1 and Hir2 proteins in yeast and to the HIRA protein in vertebrates (Sharp et al. 2001; Sutton et al. 2001; Daganzo et al. 2003; Tagami et al. 2004; Zhang et al. 2005). The interaction site between Asf1 and Hir proteins is required for formation of silent chromatin in yeast (Daganzo et al. 2003) and for formation of heterochromatin during cellular senescence in human cells (Zhang et al. 2005). Therefore, the Asf1/Hir protein complex is an evolutionarily conserved histone deposition factor.

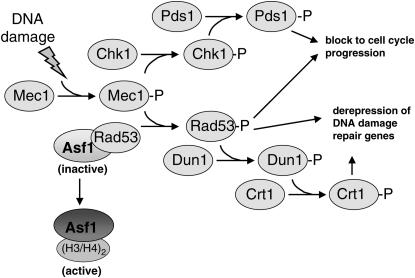

Both yeast and metazoan organisms have signal transduction mechanisms that modulate Asf1 in response to DNA damage checkpoint activation (Emili et al. 2001; Hu et al. 2001; Sillje and Nigg 2001; Groth et al. 2003). The DNA damage checkpoint is a surveillance mechanism responsible for sensing DNA damage, pausing the cell cycle to allow time for repair of the damaged DNA and activating damage response/repair pathways (reviewed in Melo and Toczyski 2002) (see Figure 1). In yeast, DNA damage triggers a protein phosphorylation cascade through Mec1, a protein kinase related to phosphoinositide kinases (Abraham 2001). Downstream of Mec1 is the protein kinase Rad53, which is activated via Mec1-dependent phosphorylation in response to DNA damage and replication blocks (Sanchez et al. 1996; Sun et al. 1996). Crosstalk between the DNA damage checkpoint and chromatin assembly in yeast was suggested when Asf1 was shown to physically interact with Rad53 (Emili et al. 2001; Hu et al. 2001). This interaction was shown to inhibit histone deposition by Asf1 in vitro, but the biological consequences were undetermined.

Figure 1.

- Cells must halt cell cycle progression until DNA damage can be repaired. Activation of the Chk2 kinase by Mec1 promotes the phosphorylation of Pds1. The phosphorylated form of Pds1 is refractory to destruction by the anaphase-promoting complex, thus causing accumulation of cells at the G2/M phase of the cell cycle in the presence of DNA damage.

- Increased transcription of genes required for DNA damage repair depends on Mec1. Mec1 activation causes Rad53 phosphorylation and the dissociation of the Asf1/Rad53 complex. Rad53-dependent phosphorylation of Dun1 leads to the phosphorylation of Crt1, a cofactor required for Tup1/Ssn6-mediated transcriptional repression of DNA damage repair genes. The Rad53 branch of the checkpoint also acts to block cell cycle progression in the presence of DNA damage in a manner that is independent of Pds1 phosphorylation. Further, because some genes induced by DNA damage do not depend on Dun1 function, alternative targets of Rad53-mediated transcriptional activation are likely to exist.

We present data here demonstrating that the Rad53-Asf1 interaction is an important regulator of heterochromatin assembly in yeast. Although previous work demonstrated that the Rad53 and Mec1 kinases regulate chromatin-mediated silencing of yeast telomere-proximal genes (Craven and Petes 2000; Longhese et al. 2000), the downstream effectors remained unknown. Here, we demonstrate that Mec1 affects telomeric silencing via Rad53-mediated regulation of Asf1/Hir protein activity. Furthermore, we show that the Dun1 kinase, a downstream target of Rad53 phosphorylation, positively regulates the Rad53-Asf1 interaction in vivo. Therefore, the Rad53-Asf1 interaction is critical for heterochromatin formation and is regulated by multiple DNA damage checkpoint kinases.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Yeast strains:

Strain genotypes are listed in Table 1. The cac1Δ∷hisG, cac1Δ∷LEU2, hir1Δ∷HIS3, asf1Δ∷TRP1, and URA3-VIIL alleles have been previously described (Gottschling et al. 1990; Sherwood et al. 1993; Kaufman et al. 1997; Sharp et al. 2001). Strains containing the dun1Δ∷HIS3 and pds1Δ∷LEU2 deletions were provided by T. Weinert (Gardner et al. 1999). The mec1Δ∷TRP1, rad53Δ∷HIS3, and sml1Δ∷HIS3 deletions were provided by R. Rothstein (Zhao et al. 1998). The sml1Δ∷kanMX6 deletion and ASF1-HA∷his5+ cassette were introduced into the W303 genetic background by single-step gene replacement and checked by PCR for correct insertion into the genome (Longtine et al. 1998). In contrast to asf1Δ cells, which are sensitive to hydroxyurea (HU) (Tyler et al. 1999), ASF1-HA∷his5+ cells displayed wild-type levels of growth on HU-containing media, thus demonstrating functionality of the tagged allele. Genetic crosses and tetrad analysis were performed following standard procedures (Kaiser et al. 1994).

TABLE 1.

Yeast strains used in this study

| Strain | Genotype | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| PKY090 | MATa; URA3-VIIL | Kaufman et al. (1997) |

| PKY638 | MATa; cac1Δ∷hisG; URA3-VIIL | Sharp et al. (2001) |

| PKY1766 | MATa; sml1Δ∷HIS3; URA3-VIIL | This study |

| PKY1769 | MATa; cac1Δ∷hisG; sml1Δ∷HIS3; URA3-VIIL | This study |

| PKY1768 | MATa; mec1Δ∷TRP1; sml1Δ_:HIS3; URA3-VIIL | This study |

| PKY1771 | MATa; cac1Δ∷hisG; mec1Δ∷TRP1; sml1Δ∷HIS3; URA3-VIIL | This study |

| PKY2704 | MATa; sml1Δ∷kanMX6; URA3-VIIL; HMRwt∷ADE2 | This study |

| PKY2706 | MATa; cac1Δ∷LEU2; sml1Δ∷kanMX6; URA3-VIIL; HMRwt∷ADE2 | This study |

| PKY2702 | MATa; rad53Δ∷HIS3; sml1Δ∷kanMX6; URA3-VIIL; HMRwt∷ADE2 | This study |

| PKY2710 | MATa; cac1Δ∷LEU2; rad53Δ∷HIS3; sml1Δ∷kanMX6; URA3-VIIL; HMRwt∷ADE2 | This study |

| PKY3611 | MATa; pds1Δ∷LEU2; URA3-VIIL | This study |

| PKY3616 | MATa; cac1Δ∷hisG; pds1Δ∷LEU2; URA3-VIIL | This study |

| PKY2758 | MATa; asf1Δ∷TRP1; rad53Δ∷HIS3; sml1Δ∷kanMX6; HMRwt∷ADE2; URA3-VIIL | This study |

| PKY3564 | MATα; hir1Δ∷HIS3; rad53Δ∷HIS3; sml1Δ∷kanMX6; URA3-VIIL | This study |

| PKY2763 | MATα; cac1Δ∷LEU2; rad53Δ∷HIS3; asf1Δ∷TRP1; sml1Δ∷kanMX6; URA3-VIIL; HMRwt∷ADE2 | This study |

| PKY3566 | MATα; cac1Δ∷hisG; rad53Δ∷HIS3; hir1Δ∷HIS3;sml1Δ∷kanMX6; URA3-VIIL | This study |

| PKY3045 | MATα; asf1Δ∷TRP1; sml1Δ∷kanMX6; URA3-VIIL; HMRwt∷ADE2 | This study |

| PKY3676 | MATa; hir1Δ∷HIS3; sml1Δ∷kanMX6; URA3-VIIL | This study |

| PKY2755 | MATα; cac1Δ∷LEU2; asf1Δ∷TRP1; sml1Δ∷kanMX6; HMRwt∷ADE2; URA3-VIIL | This study |

| PKY3680 | MATα; cac1Δ∷LEU2; hir1Δ∷HIS3; sml1Δ∷kanMX6; URA3-VIIL; HMRwt∷ADE2 | This study |

| PKY2776 | MATa; mec1Δ∷TRP1; rad53Δ∷HIS3; sml1Δ∷kanMX6; URA3-VIIL | This study |

| PKY2779 | MATa; cac1Δ∷LEU2; mec1Δ∷TRP1; rad53Δ∷HIS3; sml1Δ∷kanMX6; URA3-VIIL; HMRwt∷ADE2 | This study |

| PKY2503 | MATa; sml1Δ∷kanMX6; URA3-VIIL; HMRwt∷ADE2 | This study |

| PKY2719 | MATa; mec1Δ∷TRP1; sml1Δ∷kanMX6; URA3-VIIL; HMRwt∷ADE2 | This study |

| PKY2711 | MATa; cac1Δ∷LEU2; rad53Δ∷HIS3; sml1Δ∷kanMX6; URA3-VIIL; HMRwt∷ADE2 | This study |

| PKY2723 | MATa; cac1Δ∷LEU2; mec1Δ∷TRP1; sml1Δ∷kanMX6; URA3-VIIL | This study |

| PKY408 | MATa; (hht1-hhf1Δ)∷LEU2; URA3-VIIL | Kaufman et al. (1998) |

| PKY993 | MATaasf1Δ∷TRP1; URA3-VIIL | Sharp et al. (2001) |

| PKY1027 | MATaasf1Δ∷HIS3; (hht1-hhf1)Δ∷LEU2; URA3-VIIL | This study |

| PKY3583 | MATα; dun1Δ∷HIS3; URA3-VIIL | This study |

| PKY3584 | MATa; dun1Δ∷HIS3; cac1Δ∷LEU2; URA3-VIIL | This study |

| PKY3586 | MATα; dun1Δ∷HIS3; asf1Δ∷TRP1; URA3-VIIL | This study |

| PKY3591 | MATα; dun1Δ∷HIS3; hir1Δ∷HIS3; URA3-VIIL | This study |

| PKY3588 | MATa; dun1Δ∷HIS3; asf1Δ∷TRP1; cac1Δ∷LEU2; URA3-VIIL | This study |

| PKY3592 | MATa; dun1Δ∷HIS3; hir1Δ∷HIS3; cac1Δ∷LEU2; URA3-VIIL | This study |

| PKY2256 | MATα; ADE2-VR; URA3-VIIL + pBAD54 | This study |

| PKY2259 | MATα; ADE2-VR; URA3-VIIL + pBAD70 | This study |

| PKY2262 | MATα; ADE2-VR; URA3-VIIL + pBAD79 | This study |

| PKY2258 | MATα; cac1Δ∷hisG; ADE2-VR; URA3-VIIL + pBAD54 | This study |

| PKY2261 | MATα; cac1Δ∷hisG; ADE2-VR; URA3-VIIL + pBAD70 | This study |

| PKY2264 | MATα; cac1Δ∷hisG; ADE2-VR; URA3-VIIL + pBAD79 | This study |

| PKY2735 | MATa; ASF1-HA∷his5+; URA3-VIIL | This study |

| PKY3607 | MATa; dun1Δ∷HIS3; ASF1-HA∷his5+; URA3-VIIL | This study |

| PKY2747 | MATα; ASF1-HA∷his5+; rad53Δ∷HIS3; sml1Δ∷kanMX6; URA3-VIIL | This study |

| PKY2703 | MATα; rad53Δ∷HIS3; sml1Δ∷kanMX6; URA3-VIIL; HMRwt∷ADE2 | This study |

| PKY3748 | MATa; cac1Δ∷hisG; rad53Δ∷HIS3; sml1Δ∷kanMX6; URA3-VIIL | This study |

All strains were in the W303 background and contained the leu2-3, 112; his3-11, 15; trp1-1; ade2-1 and can1-100 mutations. Strains are listed in the order in which they are listed in the figure legends.

Plasmids:

Plasmids are listed in Table 2. To construct plasmids pPK196 and pPK197, a 4-kb PstI-NheI genomic fragment containing the ASF1 locus was first introduced into PstI-XbaI-digested pBluescript. A 2.67-kb BamHI-SacI fragment containing only the ASF1 ORF was cloned into similarly digested pRS415 and pRS425 to yield plasmids pPK196 and pPK197, respectively.

TABLE 2.

Plasmids used in this study

| Plasmid | Description | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| pRS414 | ARS-CEN-TRP1 | Sikorski and Hieter (1989) |

| pRS415 | ARS-CEN-LEU2 | Sikorski and Hieter (1989) |

| pPK196 | ARS-CEN-LEU2-ASF1 | This study |

| YEP35l | 2μ-LEU2 | Lee et al. (2003) |

| pPK197 | 2μ-LEU2-ASF1 | This study |

| pMS383 | ARS-CEN-TRP1-GAL-HHT1 | Mitch Smith (University of Virginia) |

| pPK128 | 2μ-LEU2-HHT1-HHF1 HTA1-HTB1 | Kaufman et al. (1998) |

| pRS423 | 2μ-HIS3 | Sikorski and Hieter (1989) |

| pMH151-7 | 2μ-HIS3-CRT1 | Huang et al. (1998) |

| pBAD54 | 2μ-TRP1 + GAP promoter | Desany et al. (1998) |

| pBAD70 | 2μ-TRP1 + GAP-RNR1 | Desany et al. (1998) |

| pBAD79 | 2μ-TRP1 + GAP-RNR3 | Desany et al. (1998) |

| pRAD53 | ARS-CEN-LEU2-RAD53 | Lee et al. (2003); Schwartz et al. (2003) |

| prad53fha1 | ARS-CEN-LEU2-rad53 R70A N107A | Lee et al. (2003); Schwartz et al. (2003) |

| prad53fha2 | ARS-CEN-LEU2-rad53 N655A V666A S657A | Lee et al. (2003); Schwartz et al. (2003) |

| prad53kd | ARS-CEN-LEU2-rad53 K227A D339A | Lee et al. (2003); Schwartz et al. (2003) |

Telomeric silencing assays:

Strains containing the telomere-proximal URA3-VIIL reporter gene were grown to log phase. Cell density was adjusted to OD 1.0. A 10-fold dilution series was performed for each culture, and 5 μl of each dilution was spotted onto media containing 5′-fluoroorotic acid (5′-FOA). As a control for growth, 5 μl of the same dilution series was also spotted onto rich media (YPD) or synthetic media when plasmid selection was required. Plates with the temperature-sensitive pds1Δ∷LEU2-containing strains were incubated at 25°. All other plates were incubated at 30° and photographed after 3 days (growth-control media) or 7 days (5′-FOA media). Strains containing the combinations of gene deletions described in Table 1, but without the URA3-VIIL cassette, grew similarly on 5′-FOA media, indicating that these mutations caused no intrinsic 5′-FOA sensitivity or resistance (data not shown).

Antibodies:

A rabbit polyclonal antibody raised against the conserved core of Asf1 (Daganzo et al. 2003) was used for immunoblot analysis (1:20,000 dilution), immunofluorescence (1:5000 dilution), and chromatin immunoprecipitation (1:1000 dilution). A rat anti-tubulin antibody (Accurate Scientific, Westbury, NY) was used for immunoblot analysis (1:1000 dilution). The 12CA5 anti-HA monoclonal antibody (gift from D. Rio) was partially purified by ammonium sulfate precipitation and used for immunoprecipitation (10 μg/ml) and immunoblot analysis (1 μg/ml). Goat polyclonal anti-Rad53 sera (Santa Cruz Biotechnologies) was used for immunoprecipitation (1:500 dilution) and immunoblot analysis (1:1000 dilution). Secondary antibodies were: Cy3-conjugated anti-rabbit (2 μg/ml; Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA), HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit and anti-mouse (1:10,000; Amersham, Arlington Heights, IL), HRP-conjugated anti-rat (1:1000; Jackson ImmunoResearch), and HRP-conjugated anti-goat (1:2000; Santa Cruz Biotechnologies).

Immunofluorescence:

Log-phase yeast cultures were fixed with 5% formaldehyde for 1 hr and then sonicated briefly. Cells were washed twice with 0.1 m KPO4 pH 7.5 and spheroplasted with zymolyase for 30 min at 37°. Spheroplasts were pelleted, resuspended in 0.1 m KPO4 pH 7.5, and then adhered to slides coated with poly-l-lysine (Sigma, St. Louis). Spheroplasts were blocked with PBS containing 0.1% BSA for 45 min. Antibody incubations and DAPI staining were performed as described (Pringle et al. 1991).

Immunoprecipitation:

Cell extracts from log-phase yeast cultures (OD600 0.6–0.8) were prepared as described previously (Sharp et al. 2001), except that phosphatase inhibitors (Sigma phosphatase inhibitor cocktails I and II) were also included in the lysis buffer. Extracts were normalized for protein concentration and incubated with the appropriate antibody and Protein G sepharose beads (Amersham) at 4°. Beads were washed three times in the lysis buffer prior to elution in SDS-PAGE loading buffer containing 5% β-mercaptoethanol. Trichloroacetic acid (TCA)-precipitated extracts were prepared for immunoblot analysis as described (Marsolier et al. 2000).

Telomere length analysis:

Ten micrograms of genomic DNA was digested with XhoI, separated on a 0.8% agarose gel, and hybridized overnight with a radioactive synthetic poly-d(GT) probe (Sigma). Standard hybridization conditions were used (Longhese et al. 2000). Blots were washed three times at 65° for 15 min in 1× SSC, 0.5% SDS prior to exposure to film.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation:

Chromatin crosslinking and immunoprecipitation protocols were used as described (Meluh and Broach 1999; Sharp et al. 2002). The protein concentration of crosslinked chromatin lysates was measured using a detergent-compatible Bradford assay (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). All samples were then normalized for a protein concentration of 0.5 mg/ml in a 7.5-ml volume for each immunoprecipitation. PCR analysis was performed, using primers to amplify the regions: ACT1, 0.5 kb from telomere VI-R, 7.5 kb from telomere VI-R as described (Sharp et al. 2003).

RESULTS

Mec1 and Rad53 have opposite effects on silencing in cac1Δ cells:

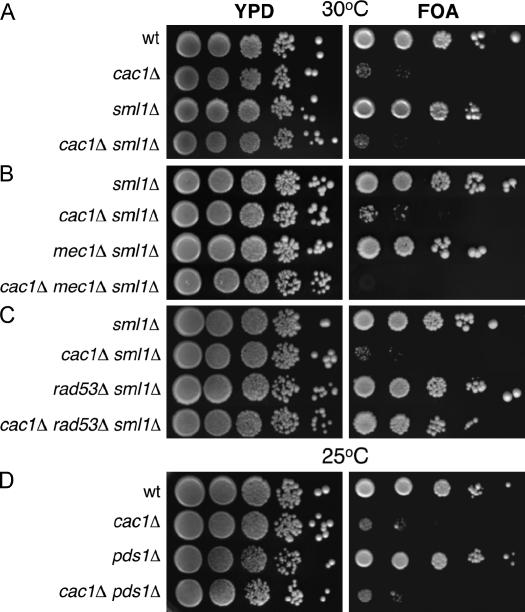

Both MEC1 and RAD53 have been implicated in the regulation of telomeric silencing (Craven and Petes 2000; Longhese et al. 2000). Because histone deposition proteins also contribute to silencing, we determined whether there is an epistatic relationship between these genes and CAF-1. We constructed yeast strains containing combinations of CAC1, MEC1, and RAD53 gene deletions and a telomere-proximal URA3 reporter gene on the left arm of chromosome VII to assay chromatin-mediated telomeric transcriptional silencing (Figure 2A) (Gottschling et al. 1990). Serial dilutions of strains were plated on rich YPD media as an internal control for cell number and on media containing the uracil analog 5′-FOA, which is toxic to cells expressing URA3 (Boeke et al. 1987), to measure URA3-VIIL silencing. None of the genetic combinations tested proved to be sensitive to FOA in the absence of the URA3-VIIL reporter gene, ruling out the possibility that the strains were intrinsically sensitive to this compound (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Mec1 and Rad53 have opposing roles in regulating the strength of telomeric silencing. Log-phase cultures of the indicated genotypes were plated onto rich media (YPD) or synthetic media containing 5′-FOA. All strains contained URA3-VIIL (Gottschling et al. 1990). (A) Deletion of SML1 has no effect on telomeric silencing. Strains were PKY090 (wild type), PKY638 (cac1Δ), PKY1766 (sml1Δ), and PKY1769 (cac1Δ sml1Δ). (B) Synergistic loss of telomeric silencing in cac1Δ mec1Δ double-mutant cells. Strains were PKY1766 (sml1Δ), PKY1769 (cac1Δ sml1Δ), PKY1768 (mec1Δ sml1Δ), and PKY1771 (cac1Δ mec1Δ sml1Δ). (C) Deletion of RAD53 suppresses the telomeric silencing defect in cac1Δ cells. Strains were PKY2704 (sml1Δ), PKY2706 (cac1Δ sml1Δ), PKY2702 (rad53Δ sml1Δ), and PKY2710 (cac1Δ rad53Δ sml1Δ). (D) Deletion of PDS1 has no effect on telomeric silencing. Strains were PKY090 (wild type), PKY638 (cac1Δ), PKY3611 (pds1Δ), and PKY3616 (cac1Δ pds1Δ).

Consistent with previous findings, both wild-type and cac1Δ cells grew equivalently on rich YPD media, confirming that CAF-1 is not required for viability under normal growth conditions and that equivalent numbers of cells were present in the different strains analyzed (Figure 2A) (Enomoto et al. 1997; Kaufman et al. 1997). As expected, the growth of cac1Δ mutant cells on 5′-FOA media was markedly less efficient than that of wild-type cells, reflecting defective silencing of the URA3 reporter gene in the absence of CAF-1 activity (Enomoto et al. 1997; Kaufman et al. 1997; Monson et al. 1997). We also analyzed effects of deleting the SML1 gene, which encodes a ribonucleotide reductase inhibitor, because this gene must be deleted to maintain viability of cells lacking the MEC1 or RAD53 genes (Zhao et al. 1998). Deletion of SML1 had no significant effects on growth or telomeric silencing in cac1Δ cells (Figure 2A).

Although semidominant alleles of MEC1 can cause telomeric silencing defects, deletion of MEC1 resulted in levels of silencing comparable to that of wild-type cells (Figure 2B), as has been previously reported (Craven and Petes 2000; Longhese et al. 2000). In contrast, cac1Δ mec1Δ double-mutant cells failed to grow on 5′-FOA media, indicating that cac1Δ mec1Δ cells are extremely defective for telomeric silencing (Figure 2B). These data suggest that the DNA damage checkpoint machinery is essential for residual telomeric silencing when CAF-1 is absent. To test this idea, we determined whether a rad53Δ gene deletion also caused a synergistic loss of silencing when combined with cac1Δ. However, in contrast to cac1Δ mec1Δ cells, cac1Δ rad53Δ cells displayed levels of telomeric silencing nearly as robust as that observed for wild-type cells (Figure 2C). Therefore, although the Mec1 and Rad53 kinases cooperate in the same signaling pathway in response to DNA damage, these proteins have opposing effects on the strength of telomeric silencing in cells lacking CAF-1.

We sought to determine whether any perturbation of the DNA damage checkpoint pathway would affect silencing in cac1Δ cells. To test this, we examined an important downstream effector of the DNA damage checkpoint pathway, the securin protein Pds1 that holds sister chromatids together and that therefore must be proteolyzed prior to chromosome segregation during mitosis (Figure 1) (Cohen-Fix et al. 1996). Pds1 is phosphorylated and protected from proteolysis upon activation of the checkpoint, serving to prevent mitosis in the presence of DNA damage (Cohen-Fix and Koshland 1997; Gardner et al. 1999; Sanchez et al. 1999; Tinker-Kulberg and Morgan 1999; Clarke et al. 2001; Wang et al. 2001). We found that deletion of the PDS1 gene had no effect on telomeric silencing and did not significantly alter silencing in cac1Δ cells (Figure 2D). These results implicate the Mec1 and Rad53 checkpoint kinases, but not all checkpoint pathway components, in chromatin-mediated gene silencing.

Because Mec1 and Rad53 had opposing effects on silencing, we tested their epistatic relationship regarding this phenotype by examining all possible combinations of deletions of the CAC1, RAD53, and MEC1 genes (Figure 3A). As expected, deletion of both RAD53 and MEC1 had no effect on silencing when the CAC1 gene was intact. We also observed that cac1Δ mec1Δ rad53Δ triple-mutant cells displayed nearly wild-type levels of telomeric silencing, as had been observed in cac1Δ rad53Δ cells. Therefore, deletion of RAD53 suppresses the severe silencing defect observed in cac1Δ mec1Δ cells. Together, these data suggest that Mec1 and Rad53 have opposite roles in regulating a factor that contributes to residual telomeric silencing when CAF-1 function is absent.

Figure 3.

Rad53 modulates telomeric silencing strength in an Asf1- and Hir1-dependent manner. Log-phase cultures of the indicated genotypes were plated onto rich media (YPD) or synthetic media containing 5′-FOA. (A) Deletion of RAD53 reverses the synergistic telomeric silencing defect of cac1Δ mec1Δ cells. Strains were PKY1766 (sml1Δ), PKY1769 (cac1Δ sml1Δ), PKY1768 (mec1Δ sml1Δ), PKY1771 (cac1Δ mec1Δ sml1Δ), PKY2702 (rad53Δ sml1Δ), PKY2710 (cac1Δ rad53Δ sml1Δ), PKY2776 (mec1Δ rad53Δ sml1Δ), and PKY2779 (cac1Δ mec1Δ rad53Δ sml1Δ). (B) Deletion of RAD53 failed to suppress the cac1Δ telomeric silencing defect in strains that lacked either ASF1 or HIR1 genes. Strains were PKY2704 (sml1Δ), PKY2706 (cac1Δ sml1Δ), PKY2702 (rad53Δ sml1Δ), PKY2710 (cac1Δ rad53Δ sml1Δ), PKY2758 (asf1Δ rad53Δ sml1Δ), PKY3564 (rad53Δ hir1Δ sml1Δ), PKY2763 (cac1Δ rad53Δ asf1Δ sml1Δ), and PKY3566 (cac1Δ rad53Δ hir1Δ sml1Δ). Consistent with previously published data, strains PKY3045 (asf1Δ sml1Δ) and PKY3676 (hir1Δ sml1Δ) exhibited wild-type levels of telomeric silencing, whereas strains PKY2755 (cac1Δ asf1Δ sml1Δ) and PKY3680 (cac1Δ hir1Δ sml1Δ) showed no growth on 5′-FOA media (data not shown) (Kaufman et al. 1998; Tyler et al. 1999).

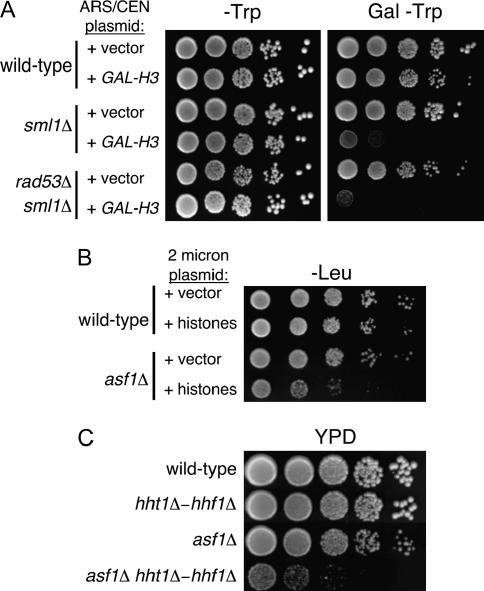

Restoration of silencing in cac1Δ rad53Δ cells requires Asf1 and Hir1:

Rad53 binds Asf1 in a manner regulated by the DNA damage checkpoint (Emili et al. 2001; Hu et al. 2001; Schwartz et al. 2003). Our silencing data supported the idea that Asf1 is sequestered by Rad53, but can be released by active Mec1 during a normal cell cycle (Figure 10). In this case, the suppression of silencing defects by deletion of RAD53 would depend on Asf1. We therefore tested the effects of an asf1Δ deletion on silencing phenotypes. Previous data showed that deletion of ASF1 alone has little effect on telomeric silencing, but exacerbates silencing defects in cac1Δ cells (Tyler et al. 1999; Sharp et al. 2001). We observed no silencing defects in rad53Δ asf1Δ double-mutant cells (Figure 3B), but cac1Δ rad53Δ asf1Δ cells displayed a strong loss of telomeric silencing. We conclude that Asf1 is required for the suppression of silencing defects by a rad53Δ deletion.

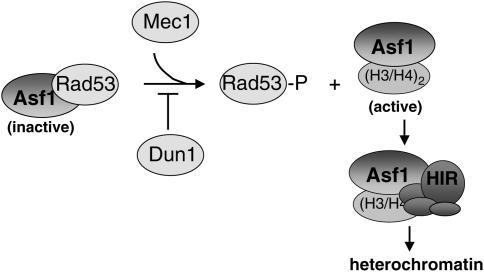

Figure 10.

Model for the regulation of Asf1/HIR complex heterochromatin function. In the absence of DNA damage, Mec1 and Dun1 have opposing roles in balancing the cellular concentration of active Asf1. Mec1 promotes the dissociation of the Rad53-Asf1 complex, whereas Dun1 blocks ectopic activation of Rad53. In the proposed model, Hir protein association with Asf1 requires dissociation of the Rad53-Asf1 complex. As a result, Mec1 and Dun1 would influence the levels of Asf1-Hir complex formation that is critical for heterochromatin-mediated gene silencing.

The contribution of Asf1 to chromatin-mediated gene silencing requires the Hir proteins, in a manner dependent on the Asf1-Hir protein interaction (Sharp et al. 2001; Sutton et al. 2001; Daganzo et al. 2003). We therefore predicted that the restoration of silencing to cac1Δ cells caused by deletion of RAD53 would also require Hir proteins. We observed that cac1Δ rad53Δ hir1Δ cells displayed a strong loss of telomeric silencing, similar to the defect in cac1Δ rad53Δ asf1Δ cells (Figure 3B). These data demonstrate that both the Asf1 and Hir1 histone deposition proteins are required for the suppression of silencing defects by rad53Δ.

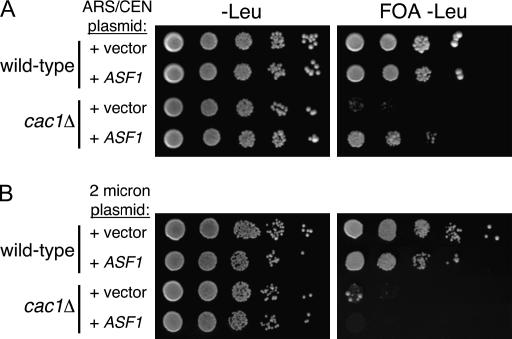

To test the prediction that the concentration of active Asf1 protein affects the efficiency of telomeric silencing in cac1Δ cells, we deliberately increased the dosage of the ASF1 gene using a low-copy centromeric plasmid and determined the effect on silencing. We observed that this modest increase in ASF1 gene dosage partially suppressed the silencing defect of cac1Δ cells (Figure 4A). However, we also observed that a much larger increase in gene dosage provided by a high-copy 2-μm vector impaired silencing in both wild-type and cac1Δ cells (Figure 4B). These latter observations are consistent with the isolation of the ASF1 gene as a dominant disruptor of silencing upon high levels of overexpression (Le et al. 1997; Singer et al. 1998) and are thought to result from extensive sequestration of histones by Asf1. We conclude that the levels of active Asf1 are critical for silencing.

Figure 4.

Gene dosage-dependent effects of ASF1 on telomeric silencing. TPE assays: (A) Suppression of the telomeric silencing defect in cac1Δ cells by low-level overexpression of ASF1. Wild-type (PKY090) and cac1Δ (PKY638) strains isogenic for URA3-VIIL were transformed with empty vector (pRS415; ARS-CEN-LEU2 plasmid) or a plasmid containing the ASF1 gene (pPK196; ARS-CEN-LEU2-ASF1). Transformants were plated onto synthetic media lacking leucine (−Leu) with and without 5′-FOA. (B) 2μ-level ASF1 overexpression disrupts silencing in cac1Δ cells. Wild-type and cac1Δ strains were transformed with empty vector (YEP35l; 2μ-LEU2 plasmid) or a 2μ-plasmid containing the ASF1 gene. (pPK197; 2μ-LEU2-ASF1). Transformants were plated onto synthetic media lacking leucine (−Leu) with and without 5′-FOA.

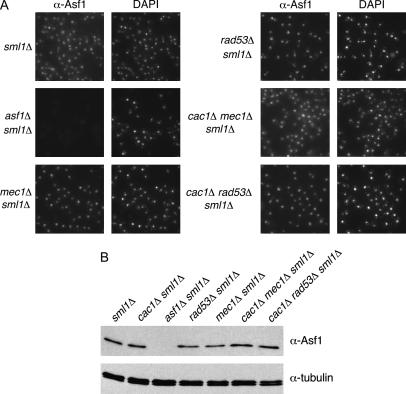

Mec1 and Rad53 do not affect telomere length, localization, expression levels, or chromatin association of Asf1:

To understand how Mec1 and Rad53 might affect Asf1 function, we tested whether the cellular localization of Asf1 protein was altered in mec1Δ and rad53Δ mutant cells. We also examined cac1Δ mec1Δ and cac1Δ rad53Δ strains that display opposite silencing efficiencies. All genotypes analyzed displayed proper nuclear localization of Asf1 as judged by overlap with DAPI staining (Figure 5A), except in the asf1Δ negative control cells that demonstrate the specificity of the antisera.

Figure 5.

Ablation of MEC1 or RAD53 gene function does not interfere with Asf1 nuclear localization, expression, or chromatin association and does not cause gross changes in average telomere length. (A) Asf1 immunofluorescence. Strains of the indicated genotypes were spheroplasted briefly and incubated with a rabbit polyclonal antibody raised against the conserved core of Asf1 (Daganzo et al. 2003). A Cy3-conjugated anti-rabbit antibody was used for secondary detection. Cells were incubated with DAPI to detect nuclear staining. (B) Immunoblot analysis of Asf1 protein levels. Crude cell extracts prepared from strains of the indicated genotypes were normalized for total protein and resolved on a 10% SDS-PAGE gel. After transfer of proteins to nitrocellulose membrane, the blot was probed with rabbit anti-Asf1 and rat anti-tubulin. (C) Chromatin immunoprecipitation of Asf1. Crosslinked chromatin was immunoprecipitated with rabbit anti-Asf1 sera. PCR analysis of ChIP eluates was performed with oligonucleotides specific for ACT1, 0.5 kb from telomere VI-R and 7.5 kb from telomere VI-R. Total chromatin was titrated to determine the linear range of the PCR; the 1:64, 1:128, and 1:256 dilutions that fall within this range are shown. For immunoprecipitations, one-fiftieth of the eluates were used for PCR analysis. (D) DNA blot analysis of telomere length. Average telomere length is indicated by the bracket. Strains in A–D were: wild type (PKY090), sml1Δ (PKY2503), cac1Δ sml1Δ (PKY1769), asf1Δ sml1Δ (PKY3045), mec1Δ sml1Δ (PKY2719), rad53Δ sml1Δ (PKY2702), cac1Δ mec1Δ sml1Δ (PKY2723), and cac1Δ rad53Δ (PKY2711).

We then considered the possibility that the cellular levels of Asf1 protein might be altered in mec1Δ and rad53Δ mutant cells. However, except in the asf1Δ negative control, immunoblot analysis of whole-cell extracts from all genotypes tested failed to detect different amounts of Asf1 relative to tubulin, which served as an internal loading control (Figure 5B). To test for changes in chromatin association of Asf1, we examined the relative abundance of the chromatin-associated pool of nuclear Asf1, using chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP; Figure 5C). In this assay, Asf1 associated with all loci with equal efficiency in all strains, regardless of the genotypic status of RAD53, MEC1, or CAC1 (Figure 5C). For example, the amount of Asf1 associated with the euchromatic locus ACT1 as well as with two sequences proximal to the telomere of chromosome VI was approximately equal among the different strains tested. Similar conclusions have been made using a different chromatin immunoprecipitation protocol (Franco et al. 2005). We also note that our attempts to study the chromatin association of Asf1 in noncrosslinked samples (Donovan et al. 1997; Liang and Stillman 1997) have been inconclusive because Asf1 is loosely associated with chromatin and can be released by washing without nuclease treatment (data not shown).

Previous experiments have shown that telomere shortening is associated with reduced telomeric silencing (Kyrion et al. 1992). Because some alleles of MEC1 and RAD53 have been implicated in telomere length maintenance (Longhese et al. 2000), we determined whether the observed telomeric silencing phenotypes in cac1Δ rad53Δ and cac1Δ mec1Δ cells correlated with alterations in telomere length. Telomeric DNA was analyzed by Southern blot hybridization with a synthetic poly(dGT) probe, which hybridizes to the yeast telomeric repeats (Figure 5D). The telomere lengths of all strains analyzed were comparable to that of the wild-type strain, demonstrating that altered telomeric silencing in cac1Δ rad53Δ and cac1Δ mec1Δ cells does not result from telomere length changes. Together, our data indicate that Mec1 and Rad53 regulate the silencing function of Asf1/Hir proteins, but not through modulation of Asf1 protein levels, nuclear localization, chromatin association, or changes in telomere length.

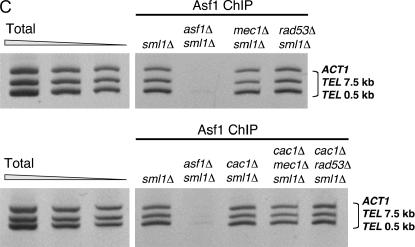

Effects of histone gene dosage and expression:

As highly basic proteins, histones pose a problem for cells when not in their nucleosomal form, because they can interact strongly with anionic molecules without biological specificity. To cope with this problem, chaperone proteins regulate the pool of nascent histones. In yeast, an Asf1-independent role for Rad53 in regulating histone levels in vivo has been described (Gunjan and Verreault 2003). Specifically, rad53Δ cells are sensitive to elevated histone gene dosage, and the growth defects and DNA damage sensitivity of rad53Δ cells are ameliorated by reduction of histone gene copy number. Because these phenotypes could contribute to the restoration of silencing that we had observed in cac1Δ rad53Δ cells, we tested the generality of the published findings. First, we tested whether the observed sensitivity of rad53Δ sml1Δ cells to elevated histone H3 gene expression was affected by the sml1Δ gene deletion required to maintain the viability of rad53Δ cells. We observed that sml1Δ and rad53Δ sml1Δ cells displayed similar sensitivity to overexpression of histone H3 (Figure 6A), indicating that the sensitivity of rad53Δ sml1Δ cells to histone H3 overexpression is at least partially due to the absence of Sml1. Because the sml1Δ deletion does not alter our silencing assay (Figure 2), and because the silencing phenotypes depended on the Asf1 and Hir1 proteins (Figures 3 and 8), our data suggest that Rad53's primary role in silencing is directly related to Asf1/Hir protein activity.

Figure 6.

Histone gene dosage phenotypes. (A) Sensitivity of sml1Δ cells to histone overexpression. pMS383 (ARS-CEN-TRP1-GAL-HHT1) and pRS414 (ARS-CEN-TRP1) were transformed into wild-type (PKY090), sml1Δ (PKY2503), and rad53Δ sml1Δ (PKY2703) strains. Cells were grown to log phase and plated onto synthetic glucose media lacking tryptophan (−Trp) or synthetic galactose media lacking tryptophan (Gal − Trp) to induce overexpression of histone H3. Plates were incubated at 30°. (B) asf1Δ cells are sensitive to increased histone gene dosage. Wild-type (PKY090) and asf1Δ (PKY993) cells were transformed with either a 2μ-plasmid containing all four histone genes (+histones, pPK128) or an empty 2μ-plasmid (+vector, yEP351). Transformants were then grown to log phase, and 10-fold serial dilutions were plated onto media lacking leucine (−Leu) and incubated at 30°. (C) asf1Δ cells are sensitive to reduced histone gene dosage. Cells lacking both Asf1 and one of the two gene pairs encoding histones H3 and H4 (HHT1-HHF1) grow slowly. Log-phase cultures of the indicated genotypes were plated onto rich media (YPD) and incubated at 30°. Strains were PKY090 (wild type), PKY408 (hht1-hhf1Δ), PKY993 (asf1Δ), and PKY1027 (asf1Δ hht1-hhf1Δ).

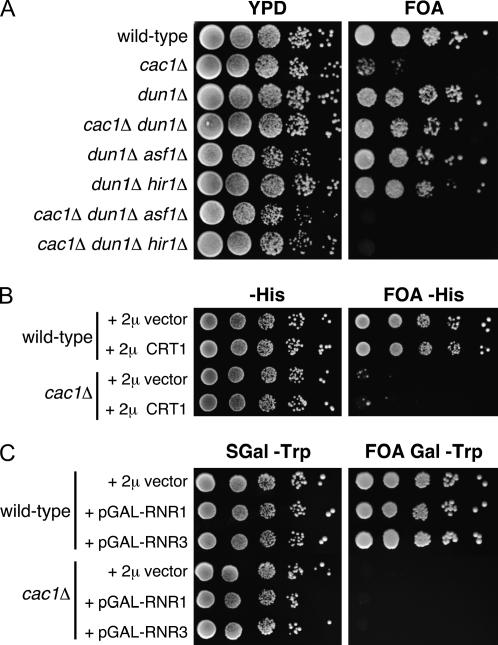

Figure 8.

Dun1 modulates telomeric silencing strength in an Asf1- and Hir1-dependent manner. (A) dun1Δ suppresses the cac1Δ telomeric silencing defect, but only when ASF1 and HIR1 genes are intact. Strains were (top to bottom): PKY090, PKY638, PKY3583, PKY3584, PKY3586, PKY3591, PKY3588, and PKY3592. (B) Overexpression of the CRT1 transcriptional repressor has no effect on telomeric silencing. Wild-type (PKY090) and cac1Δ strains (PKY638) were transformed with pRS423 (2μ-HIS3 vector) or pMH151-7 (2μ-HIS3-CRT1). Transformants were plated onto histidine-deficient synthetic media with and without 5′-FOA. (C) Overexpression of RNR genes has no effect on telomeric silencing. Wild-type and cac1Δ strains containing pBAD54 (2μ-TRP1 plasmid + galactose-inducible GAP promoter), pBAD70 (2μ-TRP1 + GAP-RNR1), or pBAD79 (2μ-TRP1 + GAP-RNR3) were plated on tryptophan-deficient synthetic media (with and without 5′-FOA) containing galactose to induce overexpression. Strains were PKY2256, PKY2259, PKY2262, PKY2258, PKY2261, and PKY2264.

Second, in human cells the Asf1-histone interaction itself appears to be a major target of regulation governing chromatin assembly activity (Groth et al. 2005). Although not detected previously (Gunjan and Verreault 2003), we observed that asf1Δ cells indeed were sensitive to overexpression of core histones (Figure 6B) or to reduction of histone gene dosage (Figure 6C). These data support the idea that Asf1 is a significant mediator of nascent histone interactions in yeast, consistent with its roles described in other eukaryotes. Furthermore, these data demonstrate that cellular resistance to histone overexpression involves multiple proteins in addition to Rad53.

The FHA domains of Rad53 affect Asf1 activity in vivo:

To test whether the Rad53-Asf1 interaction is critical for regulating the silencing activity of Asf1, we sought to specifically perturb this interaction and determine the effects on silencing. Prominent Asf1 binding sites on Rad53 have been mapped to the Rad53 FHA domains (Schwartz et al. 2003). FHA domains are phosphopeptide recognition motifs (Sun et al. 1998; Durocher et al. 1999; Schwartz et al. 2002), and Rad53 is unusual among Chk2 kinase family member in having two such motifs (Figure 7A). Coprecipitation experiments using anti-Rad53 sera or recombinant GST-Rad53 FHA domain fusion proteins have shown that a high-affinity Asf1 binding site resides in the FHA1 domain (Schwartz et al. 2003). Additionally, weak but detectable Asf1 binding was observed for the FHA2 domain. Furthermore, the kinase activity of Rad53 is important for formation of a stable Rad53-Asf1 interaction in vivo, because the catalytically inactive rad53-kd allele strongly reduces coprecipitation (Schwartz et al. 2003).

Figure 7.

Alleles of Rad53 defective for Asf1 binding cause elevated TPE in cac1Δ cells. (A) Schematic of protein domain structure of Rad53. Numbers indicate amino acid position in the Rad53 protein. Shown below the schematic are mutations resulting in impaired function of the FHA1, kinase, and FHA2 domains (after Schwartz et al. 2003). (B) Telomeric silencing assay of RAD53 alleles. ARS/CEN plasmids containing the indicated RAD53 alleles were transformed into PKY2703 (rad53Δ, sml1Δ, URA3-VIIL) and PKY3748 (cac1Δ, rad53Δ, sml1Δ, URA3-VIIL). Transformants were grown to log phase, serially diluted, and plated onto synthetic media lacking leucine (−Leu) as well as −Leu plates containing 5′-FOA.

We hypothesized that mutation of the FHA domains or active site residues would affect Rad53-mediated regulation of Asf1 in vivo. In the telomeric silencing assay, we tested low-copy plasmid-borne RAD53 alleles, including clustered point mutations in FHA1 (R70A N107A), FHA2 (N665A V666A S657A), and a catalytically inactive version (K227A D339A). All Rad53 proteins tested are expressed at levels comparable to that of the wild-type protein (Schwartz et al. 2003). We first demonstrated that none of these rad53 alleles had dominant effects on silencing in CAC1 cells (Figure 7B, top). In cac1Δ rad53Δ cells, we observed that the plasmid-borne wild-type RAD53 allele fully complemented the chromosomal rad53Δ deletion, generating cells with poor telomeric silencing because of the lack of CAF-1. As expected, an empty vector in the cac1Δ rad53Δ cells resulted in efficient silencing, indicating suppression of the cac1Δ silencing defect by the absence of Rad53. Notably, the silencing phenotypes of the mutant rad53 alleles correlated with their Asf1-binding properties (Figure 7B) (Schwartz et al. 2003). Both the rad53fha1 and the rad53kd alleles strongly restored silencing to the cac1Δ cells, consistent with poor binding of Asf1 by these Rad53 mutants. The rad53fha2 allele only modestly suppressed silencing, consistent with the weaker Asf1 binding by the FHA2 domain. We conclude that Rad53 affects silencing via the strength of its interaction with Asf1.

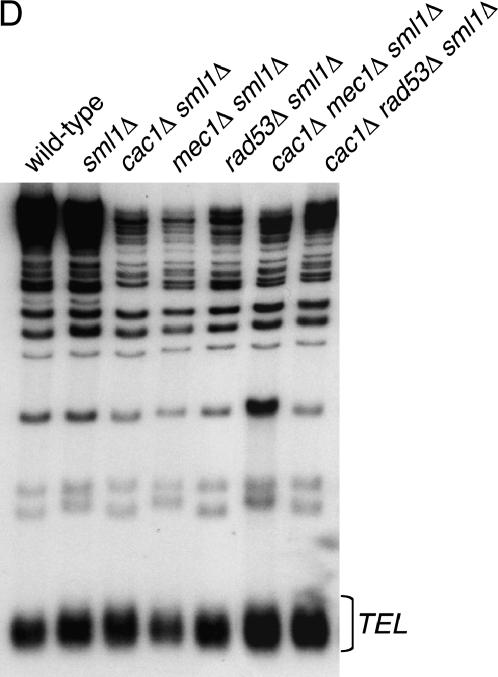

The Dun1 kinase also affects silencing in cac1Δ cells:

To further characterize how checkpoint proteins affect Asf1 function, we examined Dun1, a direct downstream substrate and effector of Rad53 kinase signaling. Dun1 is a serine/threonine kinase that coordinates the transcriptional response to DNA damage in part through phosphorylation-mediated inhibition of the Crt1 repressor (Zhou and Elledge 1993; Huang et al. 1998).

To test whether checkpoint genes downstream of Rad53 affect Asf1 function, we assayed the effect of a dun1Δ gene deletion on silencing (Figure 8A). As observed for rad53Δ, a dun1Δ deletion had little effect on silencing in wild-type cells or in cells lacking Asf1 or Hir1. In contrast, a dun1Δ deletion substantially suppressed the silencing defects in cac1Δ cells. Furthermore, the suppression of silencing defects by the dun1Δ deletion required the presence of Asf1 and Hir1. We conclude that both Rad53 and Dun1 affect the silencing activity of the Asf1/Hir protein complex.

To understand if the role of Dun1 in regulating transcription was involved in modulating silencing, we tested whether overexpression of the CRT1 repressor improved silencing in cac1Δ cells. Overexpression of CRT1 mimics a dun1Δ mutation, in that some RNR genes become uninducible in the presence of DNA damage (Huang et al. 1998). In contrast to the dun1Δ mutation, we observed that 2μ-based high-copy-number overexpression of CRT1 had no effect on silencing in wild-type or cac1Δ cells (Figure 8B). Conversely, we also examined whether deliberate overexpression of damage-inducible genes could affect silencing. However, galactose-mediated overexpression of the ribonucleotide reductase subunits Rnr1 or Rnr3 had no effect on silencing (Figure 8C), consistent with the fact that deletion of the Rnr inhibitor Sml1 also does not affect silencing (Figure 1) (Longhese et al. 2000). Therefore, we propose that Dun1 itself, but not damage-inducible transcription per se, affects Asf1 silencing activity.

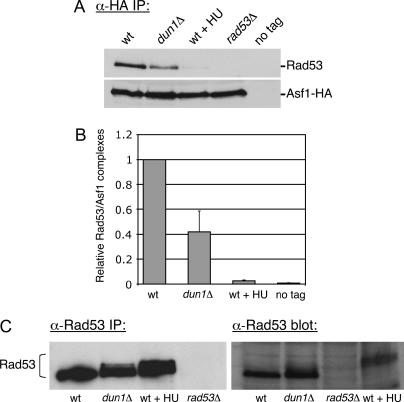

One possibility raised by these data was that Dun1 directly interacted with Asf1. However, co-immunoprecipitation experiments using cell extracts or a recombinant GST-Asf1 fusion protein and in vitro-translated Dun1 detected no direct interaction between these proteins (data not shown). We therefore tested the idea that Dun1 affected the Asf1-Rad53 interaction by examining the amount of Rad53 coprecipitated from cell extracts with an epitope-tagged Asf1-HA fusion protein. Consistent with previous results (Emili et al. 2001; Hu et al. 2001), we observed coprecipitation of Rad53 with Asf1-HA in an epitope-dependent manner in wild-type cells (Figure 9A). As expected, the Asf1-Rad53 interaction was abolished upon addition of HU, which activates the DNA replication checkpoint by depleting cellular dNTP pools. Notably, in dun1Δ cells, the amount of Rad53 stably associated with Asf1 was reduced ∼2.5-fold (Figure 9, A and B). These data suggested that a dun1Δ deletion suppresses silencing defects in cac1Δ cells by releasing a subset of Asf1 from Rad53.

Figure 9.

Asf1/Rad53 complexes are less abundant in dun1Δ mutant cells. (A) Immunoblot analysis of Asf1-HA immunoprecipitates. Cell extracts prepared from ASF1-HA (PKY2735), dun1Δ ASF1-HA (PKY3607), ASF1-HA + 0.2 m HU (PKY2735), rad53Δ sml1Δ ASF1-HA (PKY2747), and ASF1 (PKY090) strains were subjected to immunoprecipitation with an anti-HA antibody. Eluates were probed with Rad53 and HA antibodies to compare relative recovery of Asf1-HA/Rad53 complexes. (B) Quantitation of Rad53 coprecipitation with Asf1-HA from wild-type and dun1Δ cell extracts. The efficiency of Rad53 coprecipitation with Asf1-HA was measured from three independent experiments using Quantity One software (Bio-Rad). In each experiment, recovery of Rad53 from the wild-type extract was normalized to 1.0. Average recovery of Rad53 and the standard deviation for each genotype are plotted on the graph. (C) Immunoblot analysis of phosphorylated Rad53: (Left) Cell extracts from the same strains as in A were subjected to immunoprecipitation with an anti-Rad53 antibody. Eluates were analyzed on a 7.5% SDS-PAGE gel to detect slower-migrating forms of Rad53. (Right) TCA-precipitated cell extracts from the same strains were analyzed in parallel.

Because Asf1 release occurs concomitantly with Rad53 phosphorylation, we examined the phosphorylation status of Rad53 in dun1Δ cells. Rad53 becomes heavily phosphorylated after checkpoint activation (Sanchez et al. 1996; Sun et al. 1996), as can be detected by a mobility shift on protein gels. In wild-type cells, immunoprecipitated Rad53 was detected with a single mobility, whereas treatment with HU produced the expected widening and reduced mobility of the band, reflecting checkpoint-mediated phosphorylation (Figure 9C, left). In dun1Δ cells, a subset of Rad53 molecules became slower migrating, consistent with previous observations (Marsolier et al. 2000). Similar results were observed upon examination of Rad53 in TCA-precipitated cell extracts (Figure 9C, right). This latter analysis also demonstrated that the reduced levels of Rad53-Asf1 interaction in dun1Δ cells cannot be attributed to reduced Rad53 protein levels. Together, these data support the idea that deletion of DUN1 increases the concentration of active Asf1 by increasing the steady-state level of phosphorylated Rad53.

DISCUSSION

Mec1 and Dun1 regulate silencing via Asf1:

Multiple lines of evidence presented here indicate that DNA damage checkpoint kinases regulate the ability of Asf1 to contribute to chromatin-medicated telomeric gene silencing. A modest increase of ASF1 gene dosage causes more robust telomeric silencing in cac1Δ mutant cells, as does disruption of the Asf1 inhibitor Rad53. Further, both Mec1 and Asf1 are required for the residual levels of telomeric silencing in cac1Δ mutant cells, suggesting that Mec1 promotes silencing by Asf1. We propose that even in the absence of exogenous DNA damage, Mec1 facilitates the release of Asf1 from Rad53, thereby freeing Asf1 to participate in chromatin-mediated gene silencing (Figure 10). Mec1's activity in dissociating Asf1 from Rad53 could occur transiently during a normal S phase and could modulate the local concentration of Rad53/Asf1 complexes in a locus-specific manner.

Like Rad53, the absence of Dun1 restores silencing to cells lacking CAF-1 in a manner that requires the Asf1/Hir1 proteins (Figure 8). Furthermore, the absence of Dun1 results in constitutive phosphorylation of Rad53 (Marsolier et al. 2000) and a reduction in the steady-state level of association between Rad53 and Asf1 (Figure 8). Thus, the Dun1 kinase functions to restrict Rad53 phosphorylation and maintain its association with Asf1, thereby limiting the free pool of Asf1 (Figure 10).

To understand how Dun1 restricts Rad53 phosphorylation, we pursued several hypotheses. First, we detected no direct interaction between Dun1 and Asf1, thereby excluding the possibility that Dun1 participated in a ternary complex with Rad53-Asf1. Next, we attempted to distinguish whether the effect of Dun1 occurred via its role in transcriptional control or instead via feedback control on Rad53 activity. Overexpression of Crt1, which mimics loss of Dun1 signaling, had no effect on silencing. We also tested whether Dun1 was exerting feedback control onto Rad53 through the Ptc2/Ptc3 protein phosphatases that act to turn off phosphorylation-mediated checkpoint signaling (Leroy et al. 2003). However, deletion of either Ptc2 or Ptc3, or both together, had no effect on the silencing function of Asf1 (data not shown). Finally, another possibility is that dun1Δ cells experience constitutive DNA damage in a manner resulting in Rad53 phosphorylation. However, we do not favor this explanation for the restoration of silencing in dun1Δ cac1Δ cells, because deliberate treatment of cells with DNA damaging agents impairs, not strengthens, telomeric silencing due to loss of silencing proteins from telomeres under these conditions (Martin et al. 1999; Mills et al. 1999). Furthermore, our data suggest that any DNA damage induced by low dNTP levels is unable to significantly affect silencing, because Crt1 overexpression, which represses Rnr gene transcription, had no effect on silencing (Figure 8B). Future studies will be required to determine what proteins are required for the effects of Dun1 on the Rad53-Asf1 interaction.

The Asf1-Hir1 silencing complex:

The highly conserved histone-binding protein Asf1 has multiple protein partners in addition to the histones. Previous data demonstrated that Asf1 is sequestered from histones by Rad53 in a manner relieved by HU treatment (Emili et al. 2001; Hu et al. 2001). Here, we demonstrate for the first time that regulation of Asf1 and Hir1 by checkpoint kinases is critical for their silencing function in vivo, even in undamaged cells. Both Hir1 and Asf1 were required for Rad53- and Dun1-mediated effects on silencing, reinforcing the data that these histone deposition proteins act together to build heterochromatin (Figures 3 and 8) (Sharp et al. 2001; Daganzo et al. 2003; Zhang et al. 2005). We propose that Rad53 and the Hir proteins may be in separate complexes with Asf1 (Figure 10), with the former representing an inactive, sequestered form, and the latter representing an active species. Subtle fluctuations in the cellular concentration of Rad53-Asf1 complexes would thereby result in reciprocal changes in Asf1-Hir complexes, altering the histone deposition activity of Asf1. This hypothesis is consistent with the observed effects of rad53 alleles on silencing (Figure 7).

Our functional assay to detect genetic interactions between the DNA damage checkpoint and histone deposition pathways is based on position-dependent gene silencing at a yeast telomere. We note, however, that the partnership between Asf1 and Hir proteins is highly conserved in eukaryotic organisms (Daganzo et al. 2003; Zhang et al. 2005). In human cells, the interaction between the homologous Asf1a and HIRA proteins is required for senescence-associated heterochromatin formation (SAHF) (Zhang et al. 2005). SAHF is a phenomenon in which large regions of human chromosomes become visibly compacted and acquire histone modifications such as H3-K9 methylation associated with heterochromatic gene silencing (Narita et al. 2003). Therefore, despite the evolutionary distance between budding yeast and humans, the Asf1/Hir protein pathway for histone deposition is maintained as a regulatory target. Whether the mammalian DNA damage checkpoint regulates the contribution of Asf1a and HIRA to SAHF remains an outstanding question.

The Asf1-Rad53 interaction:

The highest-affinity Asf1-binding site on Rad53 resides within the FHA1 domain (Schwartz et al. 2003). FHA domains are often phosphopeptide-binding motifs (Sun et al. 1998; Durocher et al. 1999; Schwartz et al. 2002), and λ-phosphatase treatment reduces the affinity of Asf1 in cell extracts for a GST-Rad53-FHA1 fusion protein (Schwartz et al. 2003). These data suggested that phosphorylation of Asf1 or another protein stimulates the Asf1-Rad53 interaction. However, Asf1 from either wild-type or rad53Δ cell extracts interacts similarly with GST-FHA1, suggesting that Rad53 itself does not generate a phosphoepitope essential for the Asf1-Rad53 interaction. Nevertheless, Rad53 kinase activity is required for efficient Rad53-Asf1 interaction in vivo (Schwartz et al. 2003). Thus, either a Rad53 autophosphorylation event or transphosphorylation of another protein during checkpoint signaling is important for dynamic regulation of the Rad53-Asf1 interaction. We note that Rad53 autophosphorylates itself (Gilbert et al. 2001) and in doing so may alter the structure of the full-length Rad53 kinase to promote Asf1 binding. Such automodification may not be required for the isolated FHA1 domain.

We showed here that Dun1 kinase stimulates the Asf1-Rad53 interaction, raising the possibility that it modified Asf1. However, directed in vitro experiments revealed no phosphorylation or binding of Asf1 by Dun1 (data not shown). Future experiments will be required to determine whether modification of Asf1 is directly related to the Rad53 interaction.

Regulation of Asf1 in other organisms:

Rad53 is unusual among checkpoint kinases in that it has two FHA domains. Its mammalian orthologs, the Chk1 and Chk2 proteins that function immediately downstream of the PIKK-family ATM/ATR kinases, contain a single FHA domain. Notably, although in human cells the protein associations of Asf1 are regulated by HU-mediated checkpoint signaling, the Chk1 and Chk2 proteins appear not to be involved in sequestration of Asf1 (Groth et al. 2005). Therefore, Asf1 is a highly conserved central regulator of histone metabolism, but the partner proteins and mechanisms used to regulate Asf1 appear to be more diverged in distant eukaryotic species.

In metazoans, the two homologous protein kinases termed Tlk1 and Tlk2 phosphorylate Asf1 proteins (Sillje and Nigg 2001). These kinases are maximally active during S phase and are negatively regulated by DNA damage checkpoint signaling (Groth et al. 2003). It has therefore been proposed that Asf1 phosphorylation by Tlks modulates Asf1 activity in a manner regulated by the DNA damage checkpoint. However, phosphorylation of Asf1 by Tlks does not affect histone binding, and it remains to be determined what the functional consequences of these modifications are. Yeast do not have Tlk homologs. Therefore, although regulation of Asf1 by DNA damage checkpoints is an important, conserved aspect of coordinating DNA synthesis and chromatin assembly in all eukaryotes, this goal is achieved in different ways. In yeast, it involves direct sequestration of Asf1 by Rad53, and in metazoans it involves Tlk-mediated signaling. Future biochemical experiments will be required to determine how these different mechanisms of activation and repression are achieved.

Acknowledgments

We thank T. Weinert, R. Rothstein, S. Elledge, D. Stern, and M. Smith for strains and plasmids and D. Rio for a generous gift of 12CA5 antibody. We thank A. Franco, E. Green, and A. Antczak for comments and helpful discussions and D. Toczyski and T. Fazzio for critical reading of the manuscript. This work was funded by National Institutes of Health grant GM55712 and National Science Foundation grant MCB-0234014. This work was supported by the Director, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, of the U.S. Department of Energy under contract no. DE-AC03-76SF00098.

References

- Abraham, R. T., 2001. Cell cycle checkpoint signaling through the ATM and ATR kinases. Genes Dev. 15: 2177–2196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal, R., Z. Tang, H. Yu and O. Cohen-Fix, 2003. Two distinct pathways for inhibiting pds1 ubiquitination in response to DNA damage. J. Biol. Chem. 278: 45027–45033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, K., and S. Henikoff, 2002. The histone variant H3.3 marks active chromatin by replication-independent nucleosome assembly. Mol. Cell 9: 1191–1200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen, J. B., Z. Zhou, W. Siede, E. C. Friedberg and S. J. Elledge, 1994. The SAD1/RAD53 protein kinase controls multiple checkpoints and DNA damage-induced transcription in yeast. Genes Dev. 8: 2416–2428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boeke, J. D., J. Trueheart, G. Natsoulis and G. R. Fink, 1987. 5-Fluoroorotic acid as a selective agent in yeast molecular genetics. Methods Enzymol. 154: 164–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, D. J., M. Segal, S. Jensen and S. I. Reed, 2001. Mec1p regulates Pds1p levels in S phase: complex coordination of DNA replication and mitosis. Nat. Cell Biol. 3: 619–627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen-Fix, O., and D. Koshland, 1997. The anaphase inhibitor of Saccharomyces cerevisiae Pds1p is a target of the DNA damage checkpoint pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94: 14361–14366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen-Fix, O., J. M. Peters, M. W. Kirschner and D. Koshland, 1996. Anaphase initiation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae is controlled by the APC-dependent degradation of the anaphase inhibitor Pds1p. Genes Dev. 10: 3081–3093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craven, R. J., and T. D. Petes, 2000. Involvement of the checkpoint protein Mec1p in silencing of gene expression at telomeres in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20: 2378–2384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daganzo, S. M., J. P. Erzberger, W. M. Lam, E. Skordalakes, R. Zhang et al., 2003. Structure and function of the conserved core of histone deposition protein Asf1. Curr. Biol. 13: 2148–2158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desany, B. A., A. A. Alcasabas, J. B. Bachant and S. J. Elledge, 1998. Recovery from DNA replicational stress is the essential function of the S-phase checkpoint pathway. Genes Dev. 12: 2956–2970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donovan, S., J. Harwood, L. S. Drury and J. F. Diffley, 1997. Cdc6p-dependent loading of Mcm proteins onto pre-replicative chromatin in budding yeast. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94: 5611–5616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durocher, D., J. Henckel, A. R. Fersht and S. P. Jackson, 1999. The FHA domain is a modular phosphopeptide recognition motif. Mol. Cell 4: 387–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emili, A., D. M. Schieltz, J. R. Yates and L. Hartwell, 2001. Dynamic interaction of DNA damage checkpoint protein Rad53 with chromatin assembly factor Asf1. Mol. Cell 7: 13–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enomoto, S., and J. Berman, 1998. Chromatin assembly factor I contributes to the maintenance, but not the reestablishment, of silencing at the yeast silent mating loci. Genes Dev. 12: 219–232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enomoto, S., P. D. McCune-Zierath, M. Gerami-Nejad, M. Sanders and J. Berman, 1997. RLF2, a subunit of yeast chromatin assembly factor I, is required for telomeric chromatin function in vivo. Genes Dev. 11: 358–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franco, A. A., and P. D. Kaufman, 2004. Histone deposition proteins: links between the DNA replication machinery and epigenetic gene silencing. Cold Spring Harbor Symp. Quant. Biol. 69: 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franco, A. A., W. M. Lam, P. M. Burgers and P. D. Kaufman, 2005. Histone deposition protein Asf1 maintains DNA replisome integrity and interacts with replication factor C. Genes Dev. 19: 1365–1375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner, R., C. W. Putnam and T. Weinert, 1999. RAD53, DUN1 and PDS1 define two parallel G2/M checkpoint pathways in budding yeast. EMBO J. 18: 3173–3185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert, C. S., C. M. Green and N. F. Lowndes, 2001. Budding yeast Rad9 is an ATP-dependent Rad53 activating machine. Mol. Cell 8: 129–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottschling, D. E., O. M. Aparicio, B. L. Billington and V. A. Zakian, 1990. Position effect at S. cerevisiae telomeres: reversible repression of PolII transcription. Cell 63: 751–762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green, C. M., and G. Almouzni, 2003. Local action of the chromatin assembly factor CAF-1 at sites of nucleotide excision repair in vivo. EMBO J. 22: 5163–5174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groth, A., J. Lukas, E. A. Nigg, H. H. Sillje, C. Wernstedt et al., 2003. Human Tousled like kinases are targeted by an ATM- and Chk1-dependent DNA damage checkpoint. EMBO J. 22: 1676–1687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groth, A., D. Ray-Gallet, J. P. Quivy, J. Lukas, J. Bartek et al., 2005. Human Asf1 regulates the flow of S phase histones during replicational stress. Mol. Cell 17: 301–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunjan, A., and A. Verreault, 2003. A Rad53 kinase-dependent surveillance mechanism that regulates histone protein levels in S. cerevisiae. Cell 115: 537–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoek, M., and B. Stillman, 2003. Chromatin assembly factor 1 is essential and couples chromatin assembly to DNA replication in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100: 12183–12188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu, F., A. A. Alcasabas and S. J. Elledge, 2001. Asf1 links Rad53 to control of chromatin assembly. Genes Dev. 15: 1061–1066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang, M., Z. Zhou and S. J. Elledge, 1998. The DNA replication and damage checkpoint pathways induce transcription by inhibition of the Crt1 repressor. Cell 94: 595–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser, C., S. Michaelis and A. Mitchell, 1994. Methods in Yeast Genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- Kaufman, P. D., R. Kobayashi, N. Kessler and B. Stillman, 1995. The p150 and p60 subunits of chromatin assembly factor 1: a molecular link between newly synthesized histones and DNA replication. Cell 81: 1105–1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman, P. D., R. Kobayashi and B. Stillman, 1997. Ultraviolet radiation sensitivity and reduction of telomeric silencing in Saccharomyces cerevisiae cell lacking chromatin assembly factor-I. Genes Dev. 11: 345–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman, P. D., J. L. Cohen and M. A. Osley, 1998. Hir proteins are required for position-dependent gene silencing in Saccharomyces cerevisiae in the absence of chromatin assembly factor I. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18: 4793–4806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaya, H., K. I. Shibahara, K. I. Taoka, M. Iwabuchi, B. Stillman et al., 2001. FASCIATA genes for chromatin assembly factor-1 in arabidopsis maintain the cellular organization of apical meristems. Cell 104: 131–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krawitz, D. C., T. Kama and P. D. Kaufman, 2002. Chromatin assembly factor-I mutants defective for PCNA binding require Asf1/Hir proteins for silencing. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22: 614–625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krude, T., 1995. Chromatin assembly factor 1 (CAF-1) colocalizes with replication foci in HeLa cell nuclei. Exp. Cell Res. 220: 304–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyrion, G., K. A. Boakye and A. J. Lustig, 1992. C-terminal truncation of RAP1 results in the deregulation of telomere size, stability, and function in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 12: 5159–5173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le, S., C. Davis, J. B. Konopka and R. Sternglanz, 1997. Two new S-phase-specific genes from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 13: 1029–1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S. J., M. F. Schwartz, J. K. Duong and D. F. Stern, 2003. Rad53 phosphorylation site clusters are important for Rad53 regulation and signaling. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23: 6300–6314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leroy, C., S. E. Lee, M. B. Vaze, F. Ochsenbien, R. Guerois et al., 2003. PP2C phosphatases Ptc2 and Ptc3 are required for DNA checkpoint inactivation after a double-strand break. Mol. Cell 11: 827–835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang, C., and B. Stillman, 1997. Persistent initiation of DNA replication and chromatin-bound MCM proteins during the cell cycle in cdc6 mutants. Genes Dev. 11: 3375–3386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longhese, M. P., V. Paciotti, H. Neecke and G. Lucchini, 2000. Checkpoint proteins influence telomeric silencing and length maintenance in budding yeast. Genetics 155: 1577–1591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longtine, M. S., A. McKenzie, 3rd, D. J. Demarini, N. G. Shah, A. Wach et al., 1998. Additional modules for versatile and economical PCR-based gene deletion and modification in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 14: 953–961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucchini, R., and J. M. Sogo, 1995. Replication of transcriptionally active chromatin. Nature 274: 276–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luger, K., A. W. Mäder, R. K. Richmond, D. F. Sargent and T. J. Richmond, 1997. Crystal structure of the nucleosome core particle at 2.8Å resolution. Nature 389: 251–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsolier, M. C., P. Roussel, C. Leroy and C. Mann, 2000. Involvement of the PP2C-like phosphatase Ptc2p in the DNA checkpoint pathways of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 154: 1523–1532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin, S. G., T. Laroche, N. Suka, M. Grunstein and S. M. Gasser, 1999. Relocalization of telomeric Ku and SIR proteins in response to DNA strand breaks in yeast. Cell 97: 621–633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martini, E., D. M. Roche, K. Marheineke, A. Verreault and G. Almouzni, 1998. Recruitment of phosphorylated chromatin assembly factor 1 to chromatin after UV irradiation of human cells. J. Cell Biol. 143: 563–575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKittrick, E., P. R. Gafken, K. Ahmad and S. Henikoff, 2004. Histone H3.3 is enriched in covalent modifications associated with active chromatin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101: 1525–1530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melo, J., and D. Toczyski, 2002. A unified view of the DNA-damage checkpoint. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 14: 237–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meluh, P. B., and J. R. Broach, 1999. Immunological analysis of yeast chromatin. Methods Enzymol. 304: 414–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills, K. D., D. A. Sinclair and L. Guarente, 1999. MEC1-dependent redistribution of the Sir3 silencing protein from telomeres to DNA double-strand breaks. Cell 97: 609–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moggs, J. G., P. Grandi, J. P. Quivy, Z. O. Jonsson, U. Hubscher et al., 2000. A CAF-1-PCNA-mediated chromatin assembly pathway triggered by sensing DNA damage. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20: 1206–1218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monson, E. K., D. de Bruin and V. A. Zakian, 1997. The yeast Cac1 protein is required for the stable inheritance of transcriptionally repressed chromatin at telomeres. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94: 13081–13086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narita, M., S. Nunez, E. Heard, A. W. Lin, S. A. Hearn et al., 2003. Rb-mediated heterochromatin formation and silencing of E2F target genes during cellular senescence. Cell 113: 703–716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osley, M. A., and D. Lycan, 1987. Trans-acting regulatory mutations that alter transcription of Saccharomyces cerevisiae histone genes. Mol. Cell. Biol. 7: 4204–4210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pringle, J. R., A. E. M. Adams, D. G. Drubin and B. K. Haarer, 1991. Immunofluorescence methods for yeast. Methods Enzymol. 194: 565–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian, Z., H. Huang, J. Y. Hong, C. L. Burck, S. D. Johnston et al., 1998. Yeast Ty1 retrotransposition is stimulated by a synergistic interaction between mutations in chromatin assembly factor-I and histone regulatory (Hir) proteins. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18: 4783–4792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quivy, J. P., P. Grandi and G. Almouzni, 2001. Dimerization of the largest subunit of chromatin assembly factor 1: importance in vitro and during Xenopus early development. EMBO J. 20: 2015–2027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray-Gallet, D., J. P. Quivy, C. Scamps, E. M. Martini, M. Lipinski et al., 2002. HIRA is critical for a nucleosome assembly pathway independent of DNA synthesis. Mol. Cell 9: 1091–1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez, Y., B. A. Desany, W. J. Jones, Q. Liu, B. Wang et al., 1996. Regulation of RAD53 by the ATM-like kinases MEC1 and TEL1 in yeast cell cycle checkpoint pathways. Science 271: 357–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez, Y., J. Bachant, H. Wang, F. Hu, D. Liu et al., 1999. Control of the DNA damage checkpoint by chk1 and rad53 protein kinases through distinct mechanisms. Science 286: 1166–1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, M. F., J. K. Duong, Z. Sun, J. S. Morrow, D. Pradhan et al., 2002. Rad9 phosphorylation sites couple Rad53 to the Saccharomyces cerevisiae DNA damage checkpoint. Mol. Cell 9: 1055–1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, M. F., S. Lee, J. K. Duong, S. Eminaga and D. F. Stern, 2003. FHA domain-mediated DNA checkpoint regulation of Rad53. Cell Cycle 2: 384–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp, J. A., E. T. Fouts, D. C. Krawitz and P. D. Kaufman, 2001. Yeast histone deposition protein Asf1p requires Hir proteins and PCNA for heterochromatic silencing. Curr. Biol. 11: 463–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp, J. A., A. A. Franco, M. A. Osley and P. D. Kaufman, 2002. Chromatin assembly factor-I and Hir proteins contribute to building functional kinetochores in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genes Dev. 16: 85–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp, J. A., D. C. Krawitz, K. A. Gardner, C. A. Fox and P. D. Kaufman, 2003. The budding yeast silencing protein Sir1 is a functional component of centromeric chromatin. Genes Dev. 17: 2356–2361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherwood, P. W., S. V. Tsang and M. A. Osley, 1993. Characterization of HIR1 and HIR2, two genes required for regulation of histone gene transcription in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 13: 28–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibahara, K., and B. Stillman, 1999. Replication-dependent marking of DNA by PCNA facilitates CAF-1-coupled inheritance of chromatin. Cell 96: 575–585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sikorski, R. S., and P. Hieter, 1989. A system of shuttle vectors and yeast host strains designed for efficient manipulation of DNA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 122: 19–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sillje, H. H., and E. A. Nigg, 2001. Identification of human Asf1 chromatin assembly factors as substrates of Tousled-like kinases. Curr. Biol. 11: 1068–1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer, M. S., A. Kahana, A. J. Wolf, L. L. Meisinger, S. E. Peterson et al., 1998. Identification of high-copy disruptors of telomeric silencing in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 150: 613–632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith, J., E. Caputo and J. Boeke, 1999. A genetic screen for ribosomal DNA silencing defects identifies multiple DNA replication and chromatin-modulating factors. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19: 3184–3197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Z., D. S. Fay, F. Marini, M. Foiani and D. F. Stern, 1996. Spk1/Rad53 is regulated by Mec1-dependent protein phosphorylation in DNA replication and damage checkpoint pathways. Genes Dev. 10: 395–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Z., J. Hsiao, D. S. Fay and D. F. Stern, 1998. Rad53 FHA domain associated with phosphorylated Rad9 in the DNA damage checkpoint. Science 281: 272–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutton, A., J. Bucaria, M. A. Osley and R. Sternglanz, 2001. Yeast ASF1 protein is required for cell-cycle regulation of histone gene transcription. Genetics 158: 587–596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tagami, H., D. Ray-Gallet, G. Almouzni and Y. Nakatani, 2004. Histone H3.1 and H3.3 complexes mediate nucleosome assembly pathways dependent or independent of DNA synthesis. Cell 116: 51–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tinker-Kulberg, R. L., and D. O. Morgan, 1999. Pds1 and Esp1 control both anaphase and mitotic exit in normal cells and after DNA damage. Genes Dev. 13: 1936–1949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyler, J. K., M. Bulger, R. T. Kamakaka, R. Kobayashi and J. T. Kadonaga, 1996. The p55 subunit of Drosophila chromatin assembly factor-I is homologous to a histone deacetylase-associated protein. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16: 6149–6159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyler, J. K., C. R. Adams, S. R. Chen, R. Kobayashi, R. T. Kamakaka et al., 1999. The RCAF complex mediates chromatin assembly during DNA replication and repair. Nature 402: 555–560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyler, J. K., K. A. Collins, J. Prasad-Sinha, E. Amiott, M. Bulger et al., 2001. Interaction between the Drosophila CAF-1 and ASF1 chromatin assembly factors. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21: 6574–6584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H., D. Liu, Y. Wang, J. Qin and S. J. Elledge, 2001. Pds1 phosphorylation in response to DNA damage is essential for its DNA damage checkpoint function. Genes Dev. 15: 1361–1372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinert, T. A., G. L. Kiser and L. H. Hartwell, 1994. Mitotic checkpoint genes in budding yeast and the dependence of mitosis on DNA replication and repair. Genes Dev. 8: 652–665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu, H., U. J. Kim, T. Schuster and M. Grunstein, 1992. Identification of a new set of cell cycle-regulatory genes that regulate S-phase transcription of histone genes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 12: 5249–5259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye, X., A. A. Franco, H. Santos, P. D. Kaufman and P. D. Adams, 2003. Inhibition of S-phase chromatin assembly causes DNA damage, activation of the S-phase checkpoint and S-phase arrest. Mol. Cell 11: 341–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z., K. Shibahara and B. Stillman, 2000. PCNA connects DNA replication to epigenetic inheritance in yeast. Nature 408: 221–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, R., M. V. Poustovoitov, X. Ye, H. A. Santos, W. Chen et al., 2005. Formation of MacroH2A-containing senescence-associated heterochromatin foci and senescence driven by ASF1a and HIRA. Dev. Cell 8: 19–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, X., E. G. Muller and R. Rothstein, 1998. A suppressor of two essential checkpoint genes identifies a novel protein that negatively affects dNTP pools. Mol. Cell 2: 329–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Z., and S. J. Elledge, 1993. DUN1 encodes a protein kinase that controls the DNA damage response in yeast. Cell 75: 1119–1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]