Abstract

Cochlear amplification in mammalian hearing relies on an active mechanical feedback process generated by outer hair cells, driven by a protein, prestin (SLC26A5), in the lateral membrane. We have used kinetic models to understand the mechanism by which prestin might function. We show that the two previous hypotheses of prestin, which assume prestin cannot operate as a transporter, are insufficient to explain previously published data. We propose an alternative model of prestin as an electrogenic anion exchanger, exchanging one Cl− ion for one divalent or two monovalent anions. This model can reproduce the key aspects of previous experimental observations. The experimentally observed charge movements are produced by the translocation of one Cl− ion combined with intrinsic positively charged residues, while the transport of the counteranion is electroneutral. We tested the model with measurements of the Cl− dependence of charge movement, using  to replace Cl−. The data was compatible with the predictions of the model, suggesting that prestin does indeed function as a transporter.

to replace Cl−. The data was compatible with the predictions of the model, suggesting that prestin does indeed function as a transporter.

INTRODUCTION

Outer hair cells (OHCs) are one class of sensory cells of the inner ear and play an important role in enhancing the sensitivity and frequency selectivity of mammalian hearing (1). Prestin (SLC26A5) is specifically expressed in the basolateral membrane of OHCs (2) and is believed to underlie voltage-dependent OHC length changes, known as electromotility (3). This is the likely basis for cochlear amplification. The mechanical response is correlated with gating-charge movements, similar to those observed for ion channels, giving rise to a voltage-dependent nonlinear component of membrane capacitance (NLC) (4,5). The bell-shaped NLC can be described by the derivative of a two-state Boltzmann function, given by

|

(1) |

where  , Qmax is the maximum charge transferred across the membrane, Vo is the potential at half-maximal charge transfer; z is number of elementary charges, eo, displaced across a fraction, δ, of the membrane dielectric; kB is Boltzmann's constant and T is the absolute temperature. β depends on both the magnitude of the gating charge and the distance moved by it. Experimental data gives values for β of ∼0.03 mV−1 (5,6), which corresponds to one elementary charge crossing ∼80% of the membrane field. It has been proposed that this charge movement is coupled with a conformational change of prestin, producing a small change in protein area that is translated into a change in cell length due to the high density of proteins in the membrane (7,8).

, Qmax is the maximum charge transferred across the membrane, Vo is the potential at half-maximal charge transfer; z is number of elementary charges, eo, displaced across a fraction, δ, of the membrane dielectric; kB is Boltzmann's constant and T is the absolute temperature. β depends on both the magnitude of the gating charge and the distance moved by it. Experimental data gives values for β of ∼0.03 mV−1 (5,6), which corresponds to one elementary charge crossing ∼80% of the membrane field. It has been proposed that this charge movement is coupled with a conformational change of prestin, producing a small change in protein area that is translated into a change in cell length due to the high density of proteins in the membrane (7,8).

Prestin belongs to the recently identified SLC26 family of anion transporters. These transporters are structurally different from the classical SLC4 family of bicarbonate ( ) transporters (9). Currently 10 members of the SLC26 family have been identified, and all members other than prestin have been shown to function as anion exchangers, with varying substrate specificities for a wide range of both monovalent and divalent anions, including chloride (Cl−), bicarbonate (

) transporters (9). Currently 10 members of the SLC26 family have been identified, and all members other than prestin have been shown to function as anion exchangers, with varying substrate specificities for a wide range of both monovalent and divalent anions, including chloride (Cl−), bicarbonate ( ), sulfate (

), sulfate ( ), iodide (I−), hydroxyl ion (OH−), oxalate, and formate (reviewed in 10). For example, while SLC26A2 transports both

), iodide (I−), hydroxyl ion (OH−), oxalate, and formate (reviewed in 10). For example, while SLC26A2 transports both  and Cl− (11), SLC26A4 (pendrin) mediates both Cl−/I− and Cl−/formate exchange but is apparently not capable of transporting

and Cl− (11), SLC26A4 (pendrin) mediates both Cl−/I− and Cl−/formate exchange but is apparently not capable of transporting  (12,13). SLC26A6, which has ∼56% homology to prestin, is capable of transporting all the above anions (14,15,16) and has been shown to operate as an electrogenic exchanger, exchanging more than one

(12,13). SLC26A6, which has ∼56% homology to prestin, is capable of transporting all the above anions (14,15,16) and has been shown to operate as an electrogenic exchanger, exchanging more than one  ion for each Cl− ion (16,17). However, although prestin possesses all the sequence domains conserved throughout the family, including a sulfate-transport motif (18), it has not yet been shown to function as an anion transporter. Moreover, neither gating charge movements nor a NLC have been reported for any other member of the SLC26 family, suggesting prestin may have a unique function within the family.

ion for each Cl− ion (16,17). However, although prestin possesses all the sequence domains conserved throughout the family, including a sulfate-transport motif (18), it has not yet been shown to function as an anion transporter. Moreover, neither gating charge movements nor a NLC have been reported for any other member of the SLC26 family, suggesting prestin may have a unique function within the family.

Although prestin has not been shown to transport Cl−, the NLC associated with prestin was found to depend upon intracellular chloride, Cli (19,20). Thus, as for other members of the SLC26 family, prestin is likely to have at least one Cli binding site. Furthermore, the species of anion used to replace Cl− in experimental conditions affects the dependence of the NLC on Cli (21,22), suggesting that, like other members of the SLC26 family, prestin can bind a broad range of substrates. At present, there is no consensus about the origin of the NLC and the nature of its dependence on Cli. This is partly a consequence of the contradictory experimental observations—that the NLC is abolished (19) or is not abolished (21) by complete removal of Cli.. However, four key observations made in previous reports are clear:

β of the NLC is ∼0.03 mV−1.

The peak NLC (Cpk) decreases as [Cli] is reduced.

The voltage at Cpk (Vo) shifts to more positive membrane potentials as [Cli] is reduced.

The NLC is unaffected by removal of extracellular chloride (Cle) when [Cli] = 150 mM.

To achieve a better understanding of how prestin works, we have developed three kinetic types of model aiming to reproduce the key observations (I–IV). We find that a model of prestin as an anion exchanger provides a good description of the experimental observations.

Theory

All the models presented are described using simple kinetic diagrams, consisting of the intermediate states of the transporter protein (Ei) and transitions connecting these states. Each transition is described by a dielectric coefficient, which reflects the dielectric distance over which charge is translocated during the transition (23). Briefly, for a reaction step Ei→ Ei+1, in which an electric charge qi is translocated across a fraction of the membrane dielectric δi, the dielectric coefficient for the transition, αi is given as αi = qiδi/eo = γiδi, where γi is the magnitude of elementary charge translocated. All voltage-dependent reaction steps are treated as transitions over a symmetric energy barrier.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Simulating NLCs

After a voltage perturbation, transitions through voltage-dependent reaction steps result in a measurable transient current I(t), from which the measurable charge moved across the membrane, Q, and the NLC can be calculated. For a voltage-dependent reaction step, Ei↔Ei+1, Q is given by

|

(2) |

where N is the total number of transporters, eo is the elementary charge, αi is the dielectric coefficient for the reaction step, kf is the forward transition rate, kb is the backward transition rate, and Pi(t) and Pi+1(t) are occupancy probabilities of the states Ei, and Ei+1, respectively. If there is more than one voltage-dependent step then the total charge moved is the sum of that produced by each step.

The occupancy probabilities of the states from which voltage-dependent transitions occur were found using the spectral expansion of the Q-matrix, a method developed to describe transitions between ion channel states (24). Q was calculated for each step in a staircase voltage-ramp consisting of 1 mV steps between −200 mV and +200 mV. NLCs were calculated for a cell containing 107 copies of prestin. All simulations were performed in MatLab 6.5 (The MathWorks, Natick, MA).

For a given set of rate constants, NLCs were fitted to published data for [Cli] = 150 mM, 10 mM, 3 mM, and 1 mM and for [Cle] = 0 mM (19,20). Rate constants, comparable to those known for equivalent reaction steps in other transporters, were selected subject to two constraints:

In the dominant charge moving step, voltage-dependent rate constants were chosen to be at least 7 × 104 s−1, since OHC electromotility can occur up to 70 kHz (25).

Unbinding rates were assumed to be fast and chosen to be 105 s−1, similar to dissociation rates for fast binding and release from the aqueous phase.

Rate constants were varied to produce a NLC with Vo between –40 mV and –50 mV when [Cli] = 150 mM. Rate constants were optimized to minimize SSQ, the squared deviations between the data and the model, given by

|

(3) |

where RelCpkM and RelCpkD are relative Cpk for the model and data, respectively, and ΔVoM and ΔVoD are the shift in Vo for the model and data, respectively. The value κ is the maximum shift found for reduction of [Cli] to 1mM (20). Each rate constant was sequentially varied over the ranges described in Tables 1 and 2. Microscopic reversibility was maintained by simultaneously adjusting another otherwise unconstrained rate constant. It was found that the predictions for the shift in Vo depended critically on the binding rates of intracellular anions, while Vo for the NLC with [Cli] = 150 mM depended critically on the rate constants of the fast voltage-dependent step. Therefore, these rate constants were optimized first, and other rate constants were adjusted progressively to reduce SSQ.

TABLE 1.

Range of rate constants tested in simulations for the Cl−-transporter model

| Rate constant | Range of values tested | Optimized rate constants |

|---|---|---|

| k1 | 106–108 M−1 s−1 | 108 M−1 s−1 |

| k−1 | 105 s−1 | 105 s−1 |

| k2(0) | 7 × 104–42 × 104 s−1 | 7 × 104 s−1 |

| k−2(0) | 7 × 104–42 × 104 s−1 | 28 × 104 s−1 |

| k3(0) | 10–105 s−1 | 104 s−1 |

| k−3(0) | 10–105 s−1 | 105 s−1 |

| k4 | 105 s−1 | 105 s−1 |

| k−4 | 106–107 M−1 s−1 | 2.5 × 106 M−1 s−1 |

| k5 | 0–105 s−1 | 105 s−1 |

| k−5 | 0–105 s−1 | 105 s−1 |

Optimization is achieved when α1 = −0.8, α2 = −0.2, so net charge movement occurs in the two transitions E1.Cl↔E2.Cl, and E2.Cl↔E3.Cl, and k2, k−2, k3, and k−3 are voltage-dependent.

TABLE 2.

Range of rate constants tested in simulations for the  exchanger model

exchanger model

| Rate constant | Range of values tested | Optimized rate constants |

|---|---|---|

| k1 | 106–108 M−1 s−1 | 2.5 × 107 M−1 s−1 |

| k−1 | 105 s−1 | 105 s−1 |

| k2(0) | 7 × 104–35 × 104 s−1 | 28 × 104 s−1 |

| k−2(0) | 7 × 104–35 × 104 s−1 | 7 × 104 s−1 |

| k3(0) | 10–103 s−1 | 2 s−1 |

| k−3(0) | 10–103 s−1 | 100 s−1 |

| k4 | 105 s−1 | 105 s−1 |

| k−4 | 103–108 M−1 s−1 | 5 × 106 M−1 s−1 |

| k5 | 103–108 M−1 s−1 | 2.5 × 107 M−1 s−1 |

| k−5 | 105 s−1 | 105 s−1 |

| k6 | 10–103 s−1 | 200 s−1 |

| k−6 | 10–103 s−1 | 200 s−1 |

| k7 | 10–103 s−1 | 100 s−1 |

| k−7 | 10–103 s−1 | 103 s−1 |

| k8 | 105 s−1 | 105 s−1 |

| k−8 | 106–108 M−1 s−1 | 106 M−1 s−1 |

Optimization is achieved when α1 = 0.8, α2 = 0.2, so net charge movement occurs in the two transitions E1.Cl↔E2.Cl and E2.Cl↔E3.Cl and k2, k−2, k3, and k−3 are voltage-dependent.

Cell preparation and solutions

Young adult male albino guinea pigs (200–400 g) were killed by rapid cervical dislocation and both bullae were removed. Animal experiments were performed in accordance with local guidelines. The organ of Corti was dissected in HEPES-buffered solution containing (in mM): 145 NaCl, 5 KCl, 10 HEPES, 1 EGTA. Isolated OHCs were obtained by mechanical trituration after 15-min incubation in 0.25–0.5 mg/ml trypsin (T4665 from Bovine Pancreas, Sigma). The normal bath solution and the high Cl− internal solution were identical and contained (in mM): 145 NaCl, 5 KCl, 10 HEPES, 1 EGTA. Cl− concentrations were adjusted by replacing Cl− with the divalent  and sucrose to give the equivalent ionic strength and osmolarity. Accordingly, 70 mM, 74.5 mM, and 75 mM

and sucrose to give the equivalent ionic strength and osmolarity. Accordingly, 70 mM, 74.5 mM, and 75 mM  solutions were used for reduction of Cl− to 10 mM, 1 mM, and 0 mM, respectively. All solutions were adjusted to pH 7.2–7.25 with NaOH and final osmolarity was adjusted to 310–315 mOsm with D-glucose. When Cl−-free bath solution was used, a 5% agar salt bridge containing 150 mM NaCl was used. Data were corrected for liquid junction potentials, which were calculated offline using a windows version of JPCalc (26) in Clampex 7.0 (Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA).

solutions were used for reduction of Cl− to 10 mM, 1 mM, and 0 mM, respectively. All solutions were adjusted to pH 7.2–7.25 with NaOH and final osmolarity was adjusted to 310–315 mOsm with D-glucose. When Cl−-free bath solution was used, a 5% agar salt bridge containing 150 mM NaCl was used. Data were corrected for liquid junction potentials, which were calculated offline using a windows version of JPCalc (26) in Clampex 7.0 (Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA).

Membrane capacitance recordings

Whole-cell voltage clamp recordings were carried out with 3.5–4.5 MΩ resistance electrodes using an Axopatch 200 A patch amplifier (Axon Instruments). All experiments were performed at room temperature (21–23°C). Voltage-dependent capacitance measurements were made using a conventional two-phase lock-in amplifier (SR350, Stanford Research, Menlo Park, CA). Command voltage was ramped from −130 mV to 100 mV over 8 s (29 mV s−1) to ensure a close approximation to the steady state. The maximum error on NLCs measured with this protocol, which occurs in the type 3 model, was calculated and found to be <2%. Voltage ramps were summed with a 2 kHz, 10 mV sinusoid command. The first ramp was applied 10 s after break-in, to allow time to compensate the capacitive transients and were repeated every 18 s. The output of the lock-in amplifier was sampled at 256 Hz. Series resistance was not compensated, but the effect of series resistance on voltage was corrected offline.

Analysis of NLCs

Data was analyzed using MatLab 6.5. NLC traces were fitted with the derivative of a Boltzmann function, Eq. 1. Because dialysis of cells in whole-cell configuration proceeds exponentially (27), we fitted the time courses of Vo and Cpk with an exponentially decaying curve and obtained extrapolated values of Vo and Cpk at the instant of break-in (t = 0). The time courses of the shift in Vo from the instant of break-in (ΔVo = Vo–Vo(0)), and the relative decrease in Cpk from the instant of break-in (relCpk = Cpk/Cpk(0)) were determined. Paired t-tests were used to test for significant changes in any parameter over time, by comparing the first and last time-point for each cell. In all other cases, two-tailed unpaired student t-tests were used to test for significance. All data are presented as mean ± SD.

RESULTS

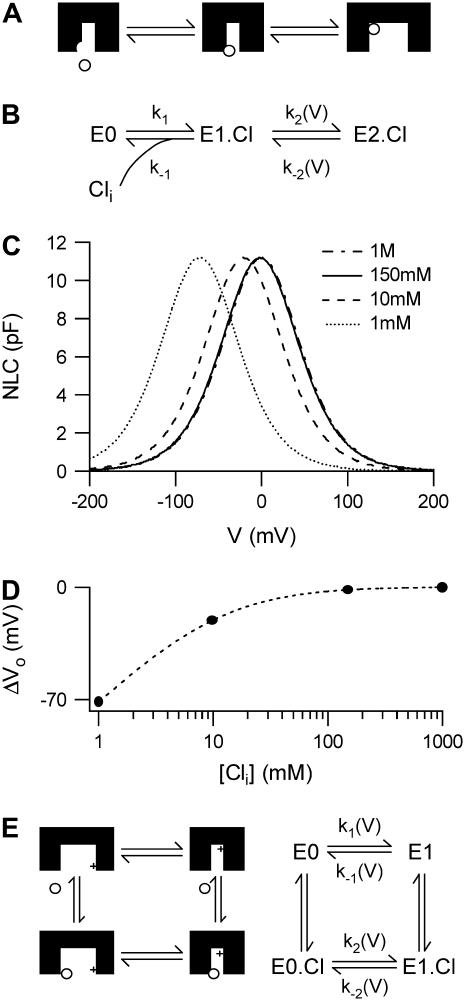

Type 1 models: nontransporting modes of prestin

It has previously been proposed that prestin works as an incomplete transporter using intracellular chloride (Cli) ions as a voltage sensor without releasing Cl− on the extracellular side (19). In this model, the Cl− ion binds first at the mouth of the pore and is then translocated across the membrane to a second site at the top of the pore (Fig. 1 A). This three-state model can be described with a reaction scheme (Fig. 1 B), where E0, E1.Cl, and E2.Cl are also assigned to represent the number of prestin molecules in that state, respectively. The total number of prestin molecules (Etot) is conserved, so

|

(4) |

The binding and unbinding of Cl− is assumed to be voltage-independent. The dissociation constant for the Cl−-binding step is given by

|

(5) |

The transition between the bound states of prestin (E1.Cl↔E2.Cl) is associated with charge translocation so the step depends on membrane potential (V). The forward and backward rate constants for the transition between the bound states are given by

|

(6) |

|

(7) |

where α is the dielectric coefficient. Since all charge movement is provided by the movement of the Cl− ion, α = zδ where z (= −1) is the valence of the Cl− ion, and δ is the fraction of the membrane dielectric crossed by the Cl− ion.

FIGURE 1.

Nontransporting models of prestin. (A) An incomplete transport model of prestin. Prestin changes from a contracted to an expanded state when a Cl− ion moves from the first binding site at the mouth of the pore to a second site at the top of the pore. All charge movement is provided by the translocation of the Cl− ion. (B) The reaction scheme used to describe this model. (C) The NLC produced by the model depends on [Cli]. In the example shown KD(Cli) = 10 mM, k2(0) = k−2(0) = 104 s−1. There is a negative shift in Vo but no change in Cpk as [Cli] is reduced. Note that the traces for 150 mM and 1 M are superimposed. (D) The shift in Vo (ΔVo) for the example shown in panel C. ΔVo is always negative when [Cli] is reduced and approaches zero as [Cli] increases. The dotted line represents Eq. 10 with ΔVo calculated relative to the Vo for 1 M [Cli]1. (E) An alternative model of prestin, where prestin changes from an expanded to a contracted state when an intrinsic positively charged sensor is moved across the membrane. All charge movement is provided by the translocation of the intrinsic charged sensor. Cli binds to a distinct site, altering the rate of charge movement (k−2(V)/k2(V) ≠ k−1(V)/k1(V)). In this and subsequent figures, inside facing surfaces of the schematic molecule is down.

In this model, hyperpolarization forces Cl− toward the extracellular surface since α is negative. As OHCs elongate upon hyperpolarization, we associate this transition with a conformational change of prestin into an expanded state (8). Since charge is transferred across the membrane every time a prestin molecule makes the transition from the state E1.Cl to the state E2.Cl, the total charge transferred, Q is proportional to the number of prestin molecules in the state E2.Cl. The number of prestin molecules in the state E2.Cl at equilibrium, is found using Eqs. 4–7:

|

(8) |

Q therefore depends on both V and [Cli]. When Cli is completely removed no charge transfer occurs, and consequently the associated NLC is abolished. As Q is proportional to E2.Cl, the maximum charge transferred, Qmax corresponds to the condition that all the prestin molecules are in the state E2.Cl. Assuming that more Cl− ions than prestin molecules are present, all the prestin molecules can be forced into the state E2.Cl, by increasing the hyperpolarizing driving force (k2(V)) sufficiently, regardless of [Cli]. Therefore contrary to experimental observations Qmax, which is proportional to Cpk (Cpk = βQmax/4, from Eq. 1) is constant for all [Cli] > 0 and only depends on the total number of prestin molecules present.

The Vo of the NLC occurs when half the maximal charge has been transferred. Using Eq. 8, Vo can be calculated as

|

(9) |

Clearly, Vo depends on [Cli] and becomes more negative as [Cli] is reduced (Fig. 1 C). The shift in Vo due to a change in [Cli] from a first concentration, [Cli]1 to a second concentration, [Cli]2 is found directly from Eq. 9 as

|

(10) |

Thus this model predicts a negative shift in Vo whenever [Cli]2 < [Cli]1. This is in the opposite direction to that observed experimentally when [Cli] is reduced (Fig. 1 D).

An alternative nontransporting model of prestin has also been proposed (21), in which it is suggested that the NLC is generated by an intrinsic voltage-sensor, and the dependence of the NLC on [Cli] is due to an allosteric action of Cl− binding to a site, distinct from the voltage-sensing residues. Such a model is illustrated in Fig. 1 E. In this model Qmax and consequently Cpk corresponds to the case that all the prestin molecules are in the state E1 or E1.Cl. As with the first model, this condition can be achieved by increasing the driving force (k1(V) and/or k2(V)) sufficiently, regardless of [Cli]. Therefore, although this model might account for the observed shifts in Vo, it likewise cannot account for the decrease in Cpk observed.

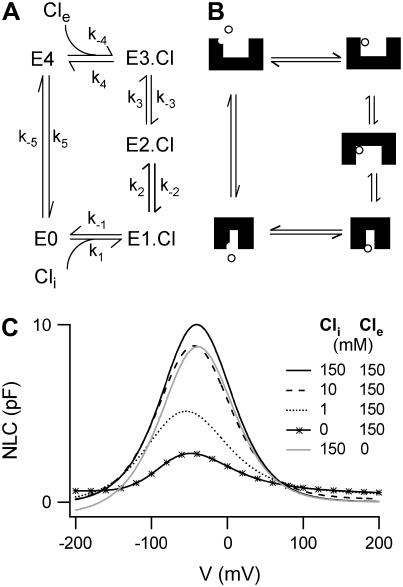

Type 2 models: chloride-transporting mode

It is clear that the previous class of nontransporting models cannot reproduce the key experimental observations (I–IV, above). Since prestin belongs to a family of anion exchangers, we have developed a model in which prestin completes a full transport cycle, transporting Cl− across the membrane (Fig. 2 A). In this model a Cl− ion binds to a binding site facing the intracellular medium, then moves through the membrane to a second site accompanied by a conformational change from where Cl− moves to a third site facing the extracellular medium and is released. Finally prestin returns to the inward facing state with no ion bound.

FIGURE 2.

A chloride transporting model. (A) The reaction scheme used to describe a chloride transporting model. Cl− binds to a binding site facing the intracellular medium. It is then transported across the membrane where it is released to the extracellular medium, before prestin returns to the unbound inward facing state. All charge movement is provided by the translocation of the Cl− ion. (B) Since hyperpolarization increases the forward rate of the transition E1.Cl↔E2.Cl, we associate this transition with a conformational change of prestin into an expanded state (8). Furthermore, since the occupancy of the outward facing state E4 is increased by removal of Cli, and OHCs elongate in low Cle (33), the state E4 is provisionally assigned an expanded conformation. All other states are assigned conformations to fit with these constraints. (C) This transporter model reproduces aspects of previous experimental observations. Cpk decreases as [Cli] is reduced and there is little effect of removing Cle in the presence of high [Cli]. However, unlike experimental observations, a negative shift in Vo is produced as [Cli] is reduced.

The reaction scheme for this model is shown in Fig. 2 B. We assume that the Cl− ion crosses the whole membrane dielectric within the two transitions, E1.Cl↔E2.Cl and E2.Cl↔E3.Cl. The binding and unbinding of both Cli and Cle are assumed to be voltage-independent. If the dielectric coefficients for the transitions E1.Cl↔E2.Cl and E2.Cl↔E3.Cl are α1 and α2, respectively, then the rate constants for the two transitions are

|

(11) |

|

(12) |

|

(13) |

|

(14) |

Since all charge movement is provided by the translocation of the Cl− ion, α1 = zδ1, α2 = zδ2 with δ1 + δ2 = 1, where (z = −1) is the valence of the Cl− ion and δ1 and δ2 are the fraction of the membrane dielectric crossed by the Cl− ion in the transitions.

In model simulations, two particular cases were considered. In the first case, the Cl− ion crosses 100% of the membrane dielectric in the first transition resulting in one voltage-dependent step (α1 = −1, α2 = 0) and NLCs with β ∼ 0.04 mV−1, in poor agreement with the data. In the second case, the Cl− ion crosses 80% of the membrane dielectric in the first transition and 20% of the membrane dielectric in the second transition, resulting in two voltage-dependent steps (α1 = −0.8, α2 = −0.2), and NLCs with β ∼ 0.03 mV−1 in agreement with the experimental observations. Since the mechanism obeys microscopic reversibility, there are nine independent rate constants for this model. Table 1 shows the range of rate constants tested. With rate constants optimized, the NLC for [Cli] = 150 mM gives Vo = −40 mV, and β = 0.032 mV−1. For all combinations tested, the model produces a decrease in Cpk when [Cli] is reduced if transitions between the inward and outward facing states can occur without Cl− bound. No combination of rate constants tested produces a positive shift in Vo.

The origin of the decrease in Cpk can be understood in the following way: when voltage is changed from very negative to very positive potentials, transitions are caused from the state E3.Cl toward the state E1.Cl. This produces the observed charge movement. The maximum possible charge movement occurs if all prestin molecules undergo transitions from the state E3.Cl to the state E1.Cl. When [Cli] is reduced, the equilibrium shifts toward E4 and E3.Cl so the population of E3.Cl is maintained even at very positive potentials. This permits fewer transitions associated with a charge movement. Hence, Cpk is reduced. Since in this model Cl− is moved across the membrane by hyperpolarization, a reduction in [Cli] shifts the equilibrium further away from the states E2.Cl and E3.Cl and toward the state E1.Cl. Thus a greater hyperpolarizing driving force is required to produce as much charge transfer, resulting in a negative shift in Vo as [Cli] is reduced. In principle, it is possible to produce a positive shift in Vo with this model, provided that transitions E0↔E4 and E2.Cl↔E3.Cl are considerably faster than the critical voltage-dependent step, E1.Cl↔E2.Cl. In such a case, the equilibrium shifts further toward the state E2.Cl as [Cli] is decreased. However, the required rate constants for the transitions E0↔E4 and E2.C↔E3.Cl would lie beyond the range we have considered reasonable for a transporter protein.

As expected for a cyclic model, the NLC curve does not asymptote to zero, when [Cli] is low or Cle is removed. This is because the transition E0↔E4 prevents the occupancy of any state from fully saturating and permits an incremental charge movement for any further membrane potential change. Furthermore, in zero Cle, the transition E0↔E4 causes the equilibrium to shift toward the state E2.Cl at very negative Vm, and leads to charge moving in the opposite direction. This produces a small negative NLC. The asymptotic dependence on [Cli] was not analyzed in further detail because these effects are only observable outside the range of potentials (−100 mV to 100 mV) usually measured.

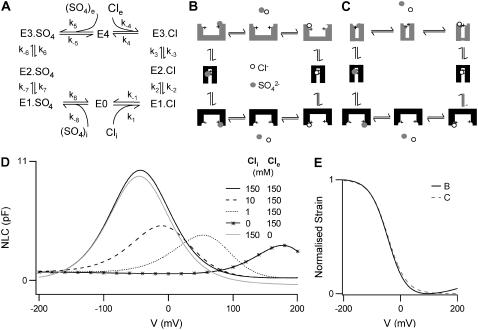

Type 3 models: anion antiporter mode, with intrinsic charge movement

The Cl− transporting model shows that in a cyclic model where Cl− is fully transported across the membrane, a decrease in Cpk is a consequence of reduced [Cli]. However, none of the previous models, in which the only charge movement is provided by the translocation of a Cl− ion, can produce a positive shift in Vo as [Cli] is reduced. Therefore, we adapted the transporter model to include the movement of intrinsic charged residues. Such movement might occur during a conformational change in the protein.

Consider a Cl− transporter model, with the same reaction scheme as that shown in Fig. 2 B, but with the movement of Cl− accompanied by the movement of intrinsic positively charged residues, so that there is a net movement of positive charge when Cl− is transported from the intracellular surface of the membrane toward the extracellular surface. During a complete cycle, the intrinsic charged residues must be returned to their original position, requiring an additional voltage-dependent step. When this is incorporated, the output of the model compares poorly with experimental observations (data not shown).

Since other members of the SLC26 family typically operate as antiporters, and since previous experimental observations have indicated that prestin interacts with a broad range of anions, we considered a model of prestin as an anion exchanger. The key property of this model is that prestin mediates electrogenic exchange, exchanging 1 Cl− ion for a divalent anion, X2−. In this model, the reorientation of the intrinsic positively charged residues only occurs with X2− bound. This effectively neutralizes the positive charge such that no net charge is moved when X2− is transported across the membrane. Thus, both the translocation of X2− and the reorientation of the intrinsic charged residues are electroneutral and there is no longer any requirement for additional voltage-dependent steps.

Since  has previously been used to substitute for Cl− in experiments, we implemented this model explicitly as a

has previously been used to substitute for Cl− in experiments, we implemented this model explicitly as a  exchanger, exchanging one Cl− ion for one

exchanger, exchanging one Cl− ion for one  ion (Fig. 3 A). Two possible conformational state assignments are shown in Fig. 3, B and C. Both assignments produce the correct electromotile length-voltage relationship (Fig. 3 E). As with the Cl− transporter model it is assumed that the Cl− ion crosses the whole membrane dielectric within the two steps E1.Cl↔E2.Cl and E2.Cl↔E3.Cl. All other transitions are assumed to be voltage-independent.

ion (Fig. 3 A). Two possible conformational state assignments are shown in Fig. 3, B and C. Both assignments produce the correct electromotile length-voltage relationship (Fig. 3 E). As with the Cl− transporter model it is assumed that the Cl− ion crosses the whole membrane dielectric within the two steps E1.Cl↔E2.Cl and E2.Cl↔E3.Cl. All other transitions are assumed to be voltage-independent.

FIGURE 3.

A chloride/sulfate antiporter model. (A) The reaction scheme for a  exchanger model. Prestin exchanges one Cl− ion for one

exchanger model. Prestin exchanges one Cl− ion for one  ion via an alternating-access mechanism, in which prestin can only change between inward and outward facing states with an anion bound. Charge movement is provided by the translocation of a Cl− ion and some intrinsic positively charged residues. Thus net positive charge is moved across the membrane as the Cl− ion is moved toward the extracellular surface. The reorientation of the intrinsic positively charged residues occurs with a

ion via an alternating-access mechanism, in which prestin can only change between inward and outward facing states with an anion bound. Charge movement is provided by the translocation of a Cl− ion and some intrinsic positively charged residues. Thus net positive charge is moved across the membrane as the Cl− ion is moved toward the extracellular surface. The reorientation of the intrinsic positively charged residues occurs with a  ion bound, which neutralizes the positive charge, so the translocation of

ion bound, which neutralizes the positive charge, so the translocation of  is voltage-independent. (B,C) Two alternative representations of the reaction scheme. Both assignments ensure that the critical voltage-dependent transition, E1.Cl↔E2.Cl, is associated with a conformational change of prestin into a compact state and symmetry is maintained (8). (D) The exchanger model reproduces most aspects of previous experimental observations. There are large positive shifts in the Vo of the NLC and Cpk decreases as [Cli] is reduced. There is little effect of removing Cle, in the presence of high [Cli]. For [Cl−] = 10, 1 or 0 mM, [

is voltage-independent. (B,C) Two alternative representations of the reaction scheme. Both assignments ensure that the critical voltage-dependent transition, E1.Cl↔E2.Cl, is associated with a conformational change of prestin into a compact state and symmetry is maintained (8). (D) The exchanger model reproduces most aspects of previous experimental observations. There are large positive shifts in the Vo of the NLC and Cpk decreases as [Cli] is reduced. There is little effect of removing Cle, in the presence of high [Cli]. For [Cl−] = 10, 1 or 0 mM, [ ] was 70, 74.5, or 75 mM, respectively. (E) Normalized strain versus membrane potential. Within the range of potentials usually measured (−100 mV to 100 mV), both representations B and C predict a sigmoidal dependence of length on potential. Depolarization causes shortening associated with an accumulation of compacted states, and hyperpolarization causes lengthening associated with an accumulation of expanded states.

] was 70, 74.5, or 75 mM, respectively. (E) Normalized strain versus membrane potential. Within the range of potentials usually measured (−100 mV to 100 mV), both representations B and C predict a sigmoidal dependence of length on potential. Depolarization causes shortening associated with an accumulation of compacted states, and hyperpolarization causes lengthening associated with an accumulation of expanded states.

Charge movement is provided by the translocation of the Cl− ion combined with the movement of intrinsic positively charged residues. If the dielectric coefficients for the transitions E1.Cl↔E2.Cl and E2.Cl↔E3.Cl are α1 and α2, respectively, then the rate constants for the two transitions are the same as those given in Eqs. 9–12. But since charge movement is provided by the translocation of the Cl− ion and intrinsic charged residues α1 = zδ1 + μ1 and α2 = zδ2 + μ2 with δ1 + δ1 = 1, where z (= −1) is the valence of the Cl− ion, δ1 and δ2 are the fraction of the dielectric crossed by the Cl− ion in the transitions, and μ1 and μ2 are the contributions due to the intrinsic charge movement.

In a single cycle the equivalent of a positively charged ion with a valence of +1 is transferred from inside to outside. Charge conservation requires that

|

(15) |

In simulations, two particular cases were considered. In the first case, the Cl− ion and the equivalent of two positively charged residues crosses 100% of the membrane dielectric in the first transition (α1 = 1, α2 = 0), resulting in NLCs with β ∼ 0.04 mV−1. In the second case, the Cl− ion and the equivalent of two positively charged residues crosses 80% of the membrane dielectric in the first transition and 20% of the membrane dielectric in the second transition (α1 = 0.8, α2 = 0.2), resulting in NLCs with β ∼ 0.03 mV−1. Because this mechanism obeys microscopic reversibility, there are 15 independent rate constants for this model. Table 2 shows the range of rate constants tested.

The  exchanger model produces a decrease in Cpk on reducing [Cli] for all combinations of rate constants. Furthermore, since in this model the Cl− is moved across the membrane by depolarization, a positive shift in Vo is also produced. With rate constants optimized, the KD for Cli is 4 mM and the KD for (SO4)i is 100 mM. The NLC produced for [Cli] = 150 mM gives Vo = –43 mV and β = 0.032 mV−1, in agreement with the experimental observations. When [Cli] is reduced to 10 mM or to 1 mM there is both a large positive shift in Vo (by 30.5 mV or 97.9 mV) and a decrease in Cpk (to 42% of max, or 34% of max, respectively) (Fig. 3 C). When Cli is completely removed a significant NLC remains (18% of max), but its Vo is shifted to very positive membrane potential (Vo = 175 mV). There is little effect on the NLC of removing Cle when [Cli] = 150 mM.

exchanger model produces a decrease in Cpk on reducing [Cli] for all combinations of rate constants. Furthermore, since in this model the Cl− is moved across the membrane by depolarization, a positive shift in Vo is also produced. With rate constants optimized, the KD for Cli is 4 mM and the KD for (SO4)i is 100 mM. The NLC produced for [Cli] = 150 mM gives Vo = –43 mV and β = 0.032 mV−1, in agreement with the experimental observations. When [Cli] is reduced to 10 mM or to 1 mM there is both a large positive shift in Vo (by 30.5 mV or 97.9 mV) and a decrease in Cpk (to 42% of max, or 34% of max, respectively) (Fig. 3 C). When Cli is completely removed a significant NLC remains (18% of max), but its Vo is shifted to very positive membrane potential (Vo = 175 mV). There is little effect on the NLC of removing Cle when [Cli] = 150 mM.

By its nature, this model has the latitude to account for the dependence of the NLC on the replacement anion where the replacement anion is divalent. However, the observations (I–IV) were also found in experiments where monovalent anions were used to replace Cl− (21,22). Therefore we tested the behavior of the model with two monovalent anions (A−) substituting for  . The two monovalent anions bind in two sequential steps, are transported across the membrane together, and then dissociate in two sequential steps. Since the two anions are transported across the membrane together, this is the charge equivalent of translocating one

. The two monovalent anions bind in two sequential steps, are transported across the membrane together, and then dissociate in two sequential steps. Since the two anions are transported across the membrane together, this is the charge equivalent of translocating one  anion across the membrane, so the translocation of 2A− is electroneutral and produces no charge movement. Like the

anion across the membrane, so the translocation of 2A− is electroneutral and produces no charge movement. Like the  exchanger, the Cl−/2A− exchanger model also produces a decrease in Cpk and positive shift in Vo as [Cli] is reduced.

exchanger, the Cl−/2A− exchanger model also produces a decrease in Cpk and positive shift in Vo as [Cli] is reduced.

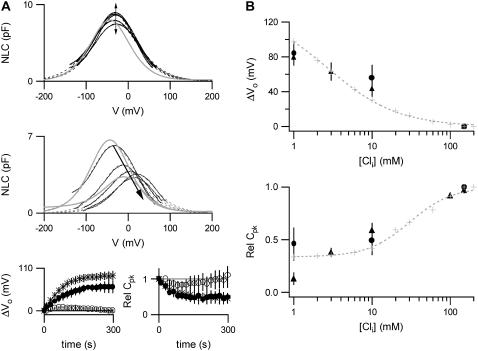

Replacing chloride with sulfate in whole-cell recordings

Although previous experimental reports have consistently shown that replacing Cli with  produces large positive shifts in Vo, there were discrepancies regarding the effects on Cpk (20,21). To compare the quantitative predictions of the

produces large positive shifts in Vo, there were discrepancies regarding the effects on Cpk (20,21). To compare the quantitative predictions of the  exchanger model with experimental data, additional experiments to test the effect on the NLC of replacing Cli with

exchanger model with experimental data, additional experiments to test the effect on the NLC of replacing Cli with  were performed.

were performed.

When cells were patched with 150 mM Cl− in the pipette solution, no shift in Vo or decrease in Cpk was observed (Fig. 4 A), suggesting that the [Cli] in the cell before break-in was sufficiently high that any further increase in [Cli] up to 150 mM does not alter the NLC. When cells were patched with a low Cl− concentration in the pipette solution there was a positive shift in Vo and a decrease in Cpk, as the ionic concentration in the cell reached the same concentration as in the pipette solution. Steady-state values were reached within 3–5 mins, consistent with previous reports (21,22). Since [Cli] in the cell before break-in produced the same NLC as 150 mM [Cli], these changes were assumed to be identical to those that would be observed for a reduction of [Cli] from 150 mM to the Cl− concentration in the pipette solution.

FIGURE 4.

The dependence of the NLC on [Cli] when Cli is replaced with  . (A) NLCs were recorded in the whole-cell configuration with a [Cli] of 150 mM (n = 7), 10 mM (n = 5), or 1 mM (n = 4). Traces are shown at 54-second intervals, from the first record. The dotted lines show the fits of the derivative of the Boltzmann function (Eq. 1) to the NLC traces. The model predictions are shown in gray. The top panel shows an example of a cell patched with 150 mM [Cli]. No change in NLC over time was observed. The prediction of the model is scaled to the Cpk measured at break-in (t = 10 s). The middle panel shows an example of a cell patched with 10 mM [Cli]. After break-in there was a positive shift in the Vo of the NLC and Cpk decreased. The model predictions were scaled to the maximum Cpk, which was estimated for the instant of break-in (t = 0). The bottom panel shows the mean time courses of the shift in Vo(ΔVo) and the relative change in Cpk (RelCpk) after break-in, for cells patched with 150 mM (○), 10 mM (•), and 1 mM (*) Cl−. There was no shift in Vo or any change in Cpk for cells patched with 150 mM [Cli]. There was a positive shift in Vo and a decrease in Cpk when cells were patched with 10 mM or 1 mM. Note RelCpk for 10 mM and 1 mM are superimposed. (B) A comparison of experimental measurements of the dependence of NLC on [Cli] with the predictions of the

. (A) NLCs were recorded in the whole-cell configuration with a [Cli] of 150 mM (n = 7), 10 mM (n = 5), or 1 mM (n = 4). Traces are shown at 54-second intervals, from the first record. The dotted lines show the fits of the derivative of the Boltzmann function (Eq. 1) to the NLC traces. The model predictions are shown in gray. The top panel shows an example of a cell patched with 150 mM [Cli]. No change in NLC over time was observed. The prediction of the model is scaled to the Cpk measured at break-in (t = 10 s). The middle panel shows an example of a cell patched with 10 mM [Cli]. After break-in there was a positive shift in the Vo of the NLC and Cpk decreased. The model predictions were scaled to the maximum Cpk, which was estimated for the instant of break-in (t = 0). The bottom panel shows the mean time courses of the shift in Vo(ΔVo) and the relative change in Cpk (RelCpk) after break-in, for cells patched with 150 mM (○), 10 mM (•), and 1 mM (*) Cl−. There was no shift in Vo or any change in Cpk for cells patched with 150 mM [Cli]. There was a positive shift in Vo and a decrease in Cpk when cells were patched with 10 mM or 1 mM. Note RelCpk for 10 mM and 1 mM are superimposed. (B) A comparison of experimental measurements of the dependence of NLC on [Cli] with the predictions of the  exchanger. The predictions of the model are shown in gray. Fitting a logistic Hill function to the shift in Vo gives a K1/2 and Hill coefficient for Cli of 2.7 ± 0.4 mM and 0.97, respectively. Fitting RelCpk gives a K1/2 and Hill coefficient for Cli of 30 ± 3 mM and 1.6, respectively. The values for ΔVo and RelCpk from those measurements in excised patches (▴) taken from (19,20) and those obtained here from whole-cell recordings (•) are shown for comparison with the predictions of the model. All data is shown as mean ± SD.

exchanger. The predictions of the model are shown in gray. Fitting a logistic Hill function to the shift in Vo gives a K1/2 and Hill coefficient for Cli of 2.7 ± 0.4 mM and 0.97, respectively. Fitting RelCpk gives a K1/2 and Hill coefficient for Cli of 30 ± 3 mM and 1.6, respectively. The values for ΔVo and RelCpk from those measurements in excised patches (▴) taken from (19,20) and those obtained here from whole-cell recordings (•) are shown for comparison with the predictions of the model. All data is shown as mean ± SD.

Accordingly when [Cli] was reduced to 10 mM or to 1 mM there was a positive shift in Vo (by 55.6 ± 15.2 mV or 84.6 ± 13.0 mV, respectively), a decrease in Cpk (to 49.0 ± 13.6% of max, or 45.8 ± 15.8% of max, respectively), and no change in β (p > 0.1). Although the shift in Vo was significantly greater when [Cli] was reduced to 1 mM (p < 0.05), Cpk did not differ significantly (p > 0.7). The experimental measurements made here and those from previously published data (19,20) are compared with the predictions of the model in Fig. 4 B.

The model predicts that a considerable NLC will remain if Cli is removed. When cells were patched with Cl−-free solution we found a residual NLC (Fig. 5 A). The Cpk of the residual NLC was within two SDs of that predicted by the model (32.4 ± 9.5% of max compared with 25% of max), whereas the shift in Vo was considerably smaller than predicted by the model (by 81.7 ± 9.8 mV compared with a predicted 218 mV). These measured values did not differ significantly from those when cells were patched with 1 mM Cl− in the pipette solution (p > 0.2).

FIGURE 5.

Residual NLCs remain in the absence of chloride. NLCs were recorded in the whole-cell configuration with either Cli completely replaced with  (n = 3), or with both Cli and Cle completely replaced with

(n = 3), or with both Cli and Cle completely replaced with  (n = 13). Where both Cli and Cle were replaced, cells were dissected and bathed in Cl−-free solution to ensure complete removal of Cl− from both internal and external solutions. Traces are shown at 54 s intervals, from the first record. The dotted lines show the fits of the derivative of the Boltzmann function (Eq. 1) to the NLC traces. Model predictions are shown in gray. (A) Example of a cell patched with Cl−-free solution, in a high-Cl− bath solution. The model predictions were scaled to the maximum Cpk, which was estimated for the instant of break-in (t = 0). A considerable NLC remained when Cli was completely removed. The Vo of the NLC shifted to a more positive potential and Cpk decreased. The shift in the NLC was much smaller than that predicted by the model. (B) Example of a cell patched in Cl−-free solution in a Cl−-free bath. An NLC was present in all cells bathed in Cl−-free solution at break-in. After break-in the Vo of the NLC shifted to a more positive potential, such that it was beyond the range of V measured. Attempts to fit the visible part of the trace were uncertain.

(n = 13). Where both Cli and Cle were replaced, cells were dissected and bathed in Cl−-free solution to ensure complete removal of Cl− from both internal and external solutions. Traces are shown at 54 s intervals, from the first record. The dotted lines show the fits of the derivative of the Boltzmann function (Eq. 1) to the NLC traces. Model predictions are shown in gray. (A) Example of a cell patched with Cl−-free solution, in a high-Cl− bath solution. The model predictions were scaled to the maximum Cpk, which was estimated for the instant of break-in (t = 0). A considerable NLC remained when Cli was completely removed. The Vo of the NLC shifted to a more positive potential and Cpk decreased. The shift in the NLC was much smaller than that predicted by the model. (B) Example of a cell patched in Cl−-free solution in a Cl−-free bath. An NLC was present in all cells bathed in Cl−-free solution at break-in. After break-in the Vo of the NLC shifted to a more positive potential, such that it was beyond the range of V measured. Attempts to fit the visible part of the trace were uncertain.

If Cl− is removed from both internal and external solutions, the model predicts that the NLC should be abolished, since transport of  is voltage-independent. To ensure all Cl− was completely washed out, cells were bathed and dissected in Cl−-free solution and patched with Cl−-free solution to ensure no exogenous source of Cl− was presented to the cells. Ten seconds after break-in a considerable NLC was detected in all cells (Fig. 5 B). However, the mean Cpk of the NLC (3.07 ± 1.31 pF, n = 13) was significantly smaller (p < 0.01) than that observed when cells were bathed in a high Cl− bath solution (7.2 ± 3.5 pF, n = 19). In addition, the mean Vo of the NLC (38.4 ± 16.8 mV, n = 13) was significantly more positive (p < 0.01) than that observed when cells were bathed in a high Cl− bath solution (−40.3 ± 10.9 mV, n = 19). This implies that the [Cli] in the cells before break-in was depleted by bathing in Cl−-free solution. After break-in, the Cpk of the NLC decreased and the Vo of the NLC appeared to shift to more positive potentials, such that in later recordings the peak of the NLC was not observable within the range of potentials recorded. Unfortunately it proved not possible to extend the range of potentials recorded without compromising the stability of the recording, and fitting of the derivative of the Boltzmann function (Eq. 1) to the visible parts of the traces was highly sensitive to the choice of initial parameters. Nevertheless, it appeared that a residual NLC remained, with its Vo shifted to potentials more positive than 100 mV. Thus, contrary to the predictions of the model, it appears that the NLC was not abolished by the removal of both Cli and Cle.

is voltage-independent. To ensure all Cl− was completely washed out, cells were bathed and dissected in Cl−-free solution and patched with Cl−-free solution to ensure no exogenous source of Cl− was presented to the cells. Ten seconds after break-in a considerable NLC was detected in all cells (Fig. 5 B). However, the mean Cpk of the NLC (3.07 ± 1.31 pF, n = 13) was significantly smaller (p < 0.01) than that observed when cells were bathed in a high Cl− bath solution (7.2 ± 3.5 pF, n = 19). In addition, the mean Vo of the NLC (38.4 ± 16.8 mV, n = 13) was significantly more positive (p < 0.01) than that observed when cells were bathed in a high Cl− bath solution (−40.3 ± 10.9 mV, n = 19). This implies that the [Cli] in the cells before break-in was depleted by bathing in Cl−-free solution. After break-in, the Cpk of the NLC decreased and the Vo of the NLC appeared to shift to more positive potentials, such that in later recordings the peak of the NLC was not observable within the range of potentials recorded. Unfortunately it proved not possible to extend the range of potentials recorded without compromising the stability of the recording, and fitting of the derivative of the Boltzmann function (Eq. 1) to the visible parts of the traces was highly sensitive to the choice of initial parameters. Nevertheless, it appeared that a residual NLC remained, with its Vo shifted to potentials more positive than 100 mV. Thus, contrary to the predictions of the model, it appears that the NLC was not abolished by the removal of both Cli and Cle.

DISCUSSION

To date, two alternative nontransporting models of prestin have been proposed. Experimental observations that the NLC was abolished by removal of Cli, but was unaffected by removal of Cle, led to the proposal that prestin uses extrinsic Cli ions as a voltage-sensor (19). Later contrasting experimental observations showed that a residual NLC remained in the absence of Cli, which led to the proposal that the NLC was generated by an intrinsic voltage-sensor, and the dependence of the NLC on [Cli] was due to an allosteric action of Cl− on prestin (21,22). In this article we have shown that both these nontransport models of prestin, whether using Cl− as a voltage-sensor or an intrinsic charged sensor, cannot account for the experimental observations, since no decrease in Cpk can be produced.

We suggest a third model in which prestin acts as an electrogenic anion exchanger, but one in which the charge movement arises as a result of both a Cl− ion and intrinsic charged residues moving across the membrane. This model is independent of the nature of the Cl− replacing anion, which could be mono- or divalent as long as it guarantees that the reorientation of the intrinsic charged residues is electroneutral. As an implementation of this concept we used previously published data, which described the Cl− dependence of the NLC when  was used to replace Cl− (19), to constrain our model and subsequently tested the predictions with additional measurements on dissociated OHCs. This

was used to replace Cl− (19), to constrain our model and subsequently tested the predictions with additional measurements on dissociated OHCs. This  exchanger model provides the first semiquantitative description of the experimental observations.

exchanger model provides the first semiquantitative description of the experimental observations.

Is chloride required to generate an NLC?

A major issue in all possible models of prestin is whether Cl− is required to generate the NLC. Although the  exchanger model presented here includes the movement of intrinsic charges, it also requires the presence of Cl− to generate a NLC. Thus, in the absence of either Cli or Cle no NLC would be produced. Instead, we found a residual NLC, shifted to very positive potentials (Vo > 100 mV) when experiments were performed under these conditions. There are at least two possible explanations for this: 1), an alternative anion such as

exchanger model presented here includes the movement of intrinsic charges, it also requires the presence of Cl− to generate a NLC. Thus, in the absence of either Cli or Cle no NLC would be produced. Instead, we found a residual NLC, shifted to very positive potentials (Vo > 100 mV) when experiments were performed under these conditions. There are at least two possible explanations for this: 1), an alternative anion such as  may substitute for Cl− to generate a NLC; or 2), Cl− cannot be completely removed, due to Cl− initially present in the OHC cytoplasm, or contamination of salts used to make up solutions. In fact, contrary to previous assumptions, the model predicts that even if [Cli] and [Cle] are only 10 μM, there is a considerable NLC, with a Cpk = 56% of max and Vo = 216 mV, which is compatible with experimental observations.

may substitute for Cl− to generate a NLC; or 2), Cl− cannot be completely removed, due to Cl− initially present in the OHC cytoplasm, or contamination of salts used to make up solutions. In fact, contrary to previous assumptions, the model predicts that even if [Cli] and [Cle] are only 10 μM, there is a considerable NLC, with a Cpk = 56% of max and Vo = 216 mV, which is compatible with experimental observations.

In contrast, removal of Cli only is not expected to abolish the NLC, since Cl− is still available from the extracellular medium. However, the NLC predicted by the model was not detected in either whole-cell experiments described here, nor in previous experiments on excised patches (19). In the whole-cell experiments, although residual NLC was detected, neither the decrease in Cpk nor the shift in Vo were as large as those predicted, while in excised patch experiments the NLC appeared to be abolished (19). One explanation for the discrepancy observed between the predicted NLC and the NLC observed in whole-cell recordings is that it is not possible to completely remove Cli in the whole-cell configuration. This is supported by a recent study, which showed that the presence of a Cl− conductance serves to counteract pipette washout when there is a large Cl− gradient (22). On the other hand, in excised patches, where Cli can be effectively removed, but the signal is smaller due to fewer prestin molecules, the predicted NLC may not be detected since its Vo lies far beyond the range of potentials measured.

A chloride conductance associated with the model

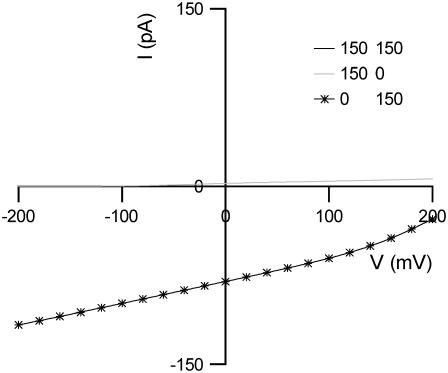

The anion exchanger model of prestin proposes that prestin mediates electrogenic exchange and therefore it should be possible to identify its transport properties using electrophysiological techniques. The effect of removing either Cli or Cle on the I(V) of an OHC can be predicted for a  exchanger. The consequences were calculated using the same optimized rate constants shown in Table 2. Complete removal of Cli shifts the reversal potential to an infinitely positive potential, and leads to an inward current of ∼80 pA at a holding potential of 0 mV (Fig. 6). Complete removal of Cle shifts the reversal potential to an infinitely negative potential, and leads to a very small outward current of ∼2.5 pA at a holding potential of 0 mV. The magnitudes of these currents are a consequence of the slow transitions E2.Cl↔E3.Cl, and E2.SO4↔E3.SO4. When 150 mM Cl− is present inside and outside the cell, no steady-state current will be observed at any potential since no full cycle can occur. However, if prestin were able to mediate Cl−/2Cl− exchange in this condition, prestin would behave as a Cl− uniporter, resulting in an I(V) that reverses at 0 mV (not shown).

exchanger. The consequences were calculated using the same optimized rate constants shown in Table 2. Complete removal of Cli shifts the reversal potential to an infinitely positive potential, and leads to an inward current of ∼80 pA at a holding potential of 0 mV (Fig. 6). Complete removal of Cle shifts the reversal potential to an infinitely negative potential, and leads to a very small outward current of ∼2.5 pA at a holding potential of 0 mV. The magnitudes of these currents are a consequence of the slow transitions E2.Cl↔E3.Cl, and E2.SO4↔E3.SO4. When 150 mM Cl− is present inside and outside the cell, no steady-state current will be observed at any potential since no full cycle can occur. However, if prestin were able to mediate Cl−/2Cl− exchange in this condition, prestin would behave as a Cl− uniporter, resulting in an I(V) that reverses at 0 mV (not shown).

FIGURE 6.

Predicted I(V)s for the chloride/sulfate exchanger model. No steady-state current is produced when [Cli] = [Cle] = 150 mM. Removal of Cli leads to a positive shift in the reversal potential and an increase in inward current at 0 mV. Removal of Cle leads to a negative shift in the reversal potential and an increase in outward current at 0 mV. 75 mM  was used to replace Cl− completely.

was used to replace Cl− completely.

Is prestin likely to function as an exchanger in vivo?

In vivo, receptor potentials in OHCs vary continuously and in response OHCs change their length, generating force that is fed back into the basilar membrane. We suggest that prestin is driving this process by means of an anion exchange cycle, in which one or more states are expanded, which can be driven by either transmembrane potential or anion gradients.

The results presented here indicate that prestin might be able to function as a  exchanger. Cl− is a likely substrate in vivo, since it is believed to be present in the cell at millimolar concentrations in vivo, with estimates for the resting [Cli] in isolated cells ranging from ∼8–20 mM (22,28). However, there is no evidence that

exchanger. Cl− is a likely substrate in vivo, since it is believed to be present in the cell at millimolar concentrations in vivo, with estimates for the resting [Cli] in isolated cells ranging from ∼8–20 mM (22,28). However, there is no evidence that  is present in OHCs or the fluids surrounding OHCs. Considering that at least two of the anion exchangers in the SLC26 family (SLC26A3 and SLC26A6) mediate both

is present in OHCs or the fluids surrounding OHCs. Considering that at least two of the anion exchangers in the SLC26 family (SLC26A3 and SLC26A6) mediate both  exchange and

exchange and  exchange, it is possible that rather than mediating

exchange, it is possible that rather than mediating  exchange in vivo, prestin mediates

exchange in vivo, prestin mediates  exchange. The presence of a

exchange. The presence of a  exchanger in OHCs has previously been suggested by evidence that in isolated OHCs, the intracellular pH depended on [Cle] (29).

exchanger in OHCs has previously been suggested by evidence that in isolated OHCs, the intracellular pH depended on [Cle] (29).

However, the unusually high density of prestin compared with other transporters suggests its primary function is to drive electromotility, and it is unlikely that it also plays the critical role in regulating Cli. In fact, several other Cl− transporters and channels have already been implicated to perform Cli regulation. ClC channels have been identified in OHCs by RT-PCR (30,31) and the  exchanger SLC4A2 (AE2) has been identified in OHCs via a combination of RT-PCR and immunohistochemistry (32), although so far there is no evidence to show that any of these proteins are localized at the cell membrane or are functional. Since at present it remains unclear which channels, and transporters are responsible for regulating [Cli] in OHCs, it is difficult to predict the extent to which prestin may contribute to the regulation of Cli and thereby help to set its own voltage-sensitivity. In practice, the turnover of prestin at physiological concentrations of substrates may be so low as to render its transport properties inconsequential. Instead, it may use its transport properties to create a motor that is sensitive to both voltage and anion gradients created by other channels.

exchanger SLC4A2 (AE2) has been identified in OHCs via a combination of RT-PCR and immunohistochemistry (32), although so far there is no evidence to show that any of these proteins are localized at the cell membrane or are functional. Since at present it remains unclear which channels, and transporters are responsible for regulating [Cli] in OHCs, it is difficult to predict the extent to which prestin may contribute to the regulation of Cli and thereby help to set its own voltage-sensitivity. In practice, the turnover of prestin at physiological concentrations of substrates may be so low as to render its transport properties inconsequential. Instead, it may use its transport properties to create a motor that is sensitive to both voltage and anion gradients created by other channels.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Alasdair Gibb for helpful discussion at early stages in this project. This work supported by the Wellcome Trust and the Medical Research Council (UK).

APPENDIX

Derivation of Eq. 9

The reaction scheme described in Fig. 1 B leads to the differential equations of

|

(16) |

|

(17) |

|

(18) |

where E0, E1.Cl, and E2.Cl are the proportion of prestin in those states, respectively. Since the total amount of prestin is conserved, Eq. 4 gives

|

In steady state,  , so combining Eqs. 16–18 and Eq. 4 gives Eq. 8

, so combining Eqs. 16–18 and Eq. 4 gives Eq. 8

|

Vo corresponds to the potential at which the state E2.Cl is half-populated, therefore when V = Vo,

|

(19) |

|

(20) |

giving Eq. 9,

|

References

- 1.Dallos, P., and D. Harris. 1978. Properties of auditory nerve responses in absence of outer hair cells. J. Neurophysiol. 41:365–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Belyantseva, I. A., H. J. Adler, R. Curi, G. I. Frolenkov, and B. Kachar. 2000. Expression and localization of prestin and the sugar transporter GLUT-5 during development of electromotility in cochlear outer hair cells. J. Neurosci. 20:RC116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liberman, M. C., J. Gao, D. Z. He, X. Wu, S. Jia, and J. Zuo. 2002. Prestin is required for electromotility of the outer hair cell and for the cochlear amplifier. Nature. 419:300–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ashmore, J. F. 1990. Forward and reverse transduction in the mammalian cochlea. Neurosci. Res. Suppl. 12:S39–S50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Santos-Sacchi, J. 1991. Reversible inhibition of voltage-dependent outer hair cell motility and capacitance. J. Neurosci. 11:3096–3110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gale, J. E., and J. F. Ashmore. 1997. The outer hair cell motor in membrane patches. Pflugers Arch. 434:267–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dallos, P., R. Hallworth, and B. N. Evans. 1993. Theory of electrically driven shape changes of cochlear outer hair cells. J. Neurophysiol. 70:299–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iwasa, K. H. 1994. A membrane motor model for the fast motility of the outer hair cell. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 96:2216–2224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Everett, L. A., and E. D. Green. 1999. A family of mammalian anion transporters and their involvement in human genetic diseases. Hum. Mol. Genet. 8:1883–1891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mount, D. B., and M. F. Romero. 2004. The SLC26 gene family of multifunctional anion exchangers. Pflugers Arch. 447:710–721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Satoh, H., M. Susaki, C. Shukunami, K. Iyama, T. Negoro, and Y. Hiraki. 1998. Functional analysis of diastrophic dysplasia sulfate transporter. Its involvement in growth regulation of chondrocytes mediated by sulfated proteoglycans. J. Biol. Chem. 273:12307–12315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scott, D. A., R. Wang, T. M. Kreman, V. C. Sheffield, and L. P. Karniski. 1999. The Pendred syndrome gene encodes a chloride-iodide transport protein. Nat. Genet. 21:440–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scott, D. A., and L. P. Karniski. 2000. Human pendrin expressed in Xenopus laevis oocytes mediates chloride/formate exchange. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 278:C207–C211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Knauf, F., C. L. Yang, R. B. Thomson, S. A. Mentone, G. Giebisch, and P. S. Aronson. 2001. Identification of a chloride-formate exchanger expressed on the brush border membrane of renal proximal tubule cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 98:9425–9430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jiang, Z., I. I. Grichtchenko, W. F. Boron, and P. S. Aronson. 2002. Specificity of anion exchange mediated by mouse Slc26a6. J. Biol. Chem. 277:33963–33967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xie, Q., R. Welch, A. Mercado, M. F. Romero, and D. B. Mount. 2002. Molecular characterization of the murine Slc26a6 anion exchanger: functional comparison with Slc26a1. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 283:F826–F838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

-

17.Ko, S. B., N. Shcheynikov, J. Y. Choi, X. Luo, K. Ishibashi, P. J. Thomas, J. Y. Kim, K. H. Kim, M. G. Lee, S. Naruse, and S. Muallem. 2002. A molecular mechanism for aberrant CFTR-dependent

transport in cystic fibrosis. EMBO J. 21:5662–5672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

transport in cystic fibrosis. EMBO J. 21:5662–5672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] - 18.Zheng, J., K. B. Long, W. Shen, L. D. Madison, and P. Dallos. 2001. Prestin topology: localization of protein epitopes in relation to the plasma membrane. Neuroreport. 12:1929–1935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oliver, D., D. Z. He, N. Klocker, J. Ludwig, U. Schulte, S. Waldegger, J. P. Ruppersberg, P. Dallos, and B. Fakler. 2001. Intracellular anions as the voltage sensor of prestin, the outer hair cell motor protein. Science. 292:2340–2343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fakler, B., and D. Oliver. 2002. Functional properties of prestin—how the motor molecule works. In Biophysics of the Cochlea from Molecules to Models. A.W. Gummer, editor. World Scientific, Singapore. 110–115.

- 21.Rybalchenko, V., and J. Santos-Sacchi. 2003. Cl- flux through a non-selective, stretch-sensitive conductance influences the outer hair cell motor of the guinea-pig. J. Physiol. 547:873–891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Song, L., A. Seeger, and J. Santos-Sacchi. 2005. On membrane motor activity and chloride flux in the outer hair cell: lessons learned from the environmental toxin tributyltin. Biophys. J. 88:2350–2362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lauger, P., and H. J. Apell. 1988. Transient behaviour of the Na+/K+-pump: microscopic analysis of nonstationary ion translocation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 944:451–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Colquhoun, D., and A. G. Hawkes. 1995. A Q-Matrix Cookbook: How to write only one program to calculate the single-channel and macroscopic predictions for any kinetic mechanism. In Single-Channel Recordings. B. Sakmann and E. Neher, editors. Plenum, New York. 589–636.

- 25.Barry, P. H. 1994. JPCALC, a software package for calculating liquid junction potential corrections in patch-clamp, intracellular, epithelial and bilayer measurements and for correction junction potential measurements. J. Neurosci. Methods. 51:107–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Frank, G., W. Hemmert, and A. W. Gummer. 1999. Limiting dynamics of high-frequency electromechanical transduction of outer hair cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 96:4420–4425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marty, A., and E. Neher. 1995. Tight seal whole-cell recordings. In Single Channel Recordings. B. Sakmann, and E. Neher, editors. Plenum, New York. 31–52.

- 28.Ohnishi, S., M. Hara, M. Inoue, T. Yamashita, T. Kumazawa, A. Minato, and C. Inagaki. 1992. Delayed shortening and shrinkage of cochlear outer hair cells. Am. J. Physiol. 263:C1088–C1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ikeda, K., Y. Saito, A. Nishiyama, and T. Takasaka. 1992. Intracellular pH regulation in isolated cochlear outer hair cells of the guinea-pig. J. Physiol. 447:627–648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kawasaki, E., N. Hattori, E. Miyamoto, T. Yamashita, and C. Inagaki. 1999. Single-cell RT-PCR demonstrates expression of voltage-dependent chloride channels (ClC-1, ClC-2 and ClC-3) in outer hair cells of rat cochlea. Brain Res. 838:166–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kawasaki, E., N. Hattori, E. Miyamoto, T. Yamashita, and C. Inagaki. 2000. mRNA expression of kidney-specific ClC-K1 chloride channel in single-cell reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction analysis of outer hair cells of rat cochlea. Neurosci. Lett. 290:76–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zimmermann, U., I. Kopschall, K. Rohbock, G. J. Bosman, H. P. Zenner, and M. Knipper. 2000. Molecular characterization of anion exchangers in the cochlea. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 205:25–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cecola, R. P., and R. P. Bobbin. 1992. Lowering extracellular chloride concentration alters outer hair cell shape. Hear. Res. 61:65–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]